Abstract

Purpose:

To quantify improvement in target conformity in brain and head and neck tumor treatments resulting from the use of a dynamic collimation system (DCS) with two spot scanning proton therapy delivery systems (universal nozzle, UN, and dedicated nozzle, DN) with median spot sizes of 5.2 and 3.2 mm over a range of energies from 100 to 230 MeV.

Methods:

Uncollimated and collimated plans were calculated with both UN and DN beam models implemented within our in-house treatment planning system for five brain and ten head and neck datasets in patients previously treated with spot scanning proton therapy. The prescription dose and beam angles from the clinical plans were used for both the UN and DN plans. The average reduction of the mean dose to the 10-mm ring surrounding the target between the uncollimated and collimated plans was calculated for the UN and the DN. Target conformity was analyzed using the mean dose to 1-mm thickness rings surrounding the target at increasing distances ranging from 1 to 10 mm.

Results:

The average reductions of the 10-mm ring mean dose for the UN and DN plans were 13.7% (95% CI: 11.6%–15.7%; p < 0.0001) and 11.5% (95% CI: 9.5%–13.5%; p < 0.0001) across all brain cases and 7.1% (95% CI: 4.4%–9.8%; p < 0.001) and 6.3% (95% CI: 3.7%–9.0%; p < 0.001), respectively, across all head and neck cases. The collimated UN plans were either more conformal (all brain cases and 60% of the head and neck cases) than or equivalent (40% of the head and neck cases) to the uncollimated DN plans. The collimated DN plans offered the highest conformity.

Conclusions:

The DCS added either to the UN or DN improved the target conformity. The DCS may be of particular interest for sites with UN systems looking for a more economical solution than upgrading the nozzle to improve the target conformity of their spot scanning proton therapy system.

Keywords: collimation, spot scanning proton therapy, target conformity, nozzle

1. INTRODUCTION

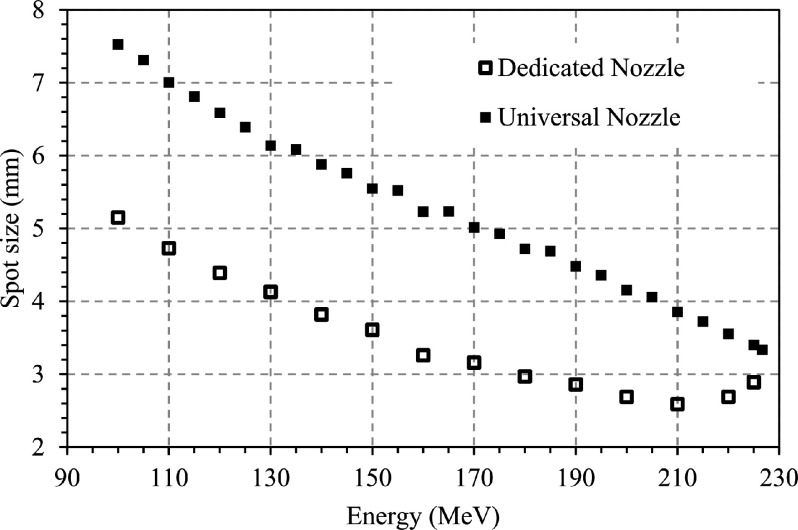

Collimation (COL) in spot scanning proton therapy is a rapidly developing field of interest as proton therapy is being used to treat an increasing number of sites, such as head and neck cancers, that are currently dominated by state of the art photon therapies. In particular, the brain and head and neck sites may exhibit the most benefit from collimation since “low” proton energies (typically, below 100 MeV) with large spot sizes are used to treat shallow targets. To effectively treat the brain and head and neck cancers with conformity equivalent to photon therapy, the spot size of the proton beamlet defined as one sigma of the lateral Gaussian intensity distribution must be reduced to approximately 4 mm.1–3 The spot size that can be expected from commercial proton therapy systems depends largely on the design of the nozzle and beamline. Figure 1 shows the spot sizes that can be achieved from the IBA (Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium) universal nozzle (UN) and dedicated nozzle (DN). As can be observed, the DN yields a spot size approximately 35% smaller than that of the UN over the range of energies below 200 MeV.4–6 Several investigators have evaluated the impact of spot size on plan quality,1–3,6 and the impact of adding collimation to proton therapy delivery systems7 has also been investigated. In the current work, the impact of the dynamic collimation system (DCS) on dose distributions delivered with two different commercially available pencil beam scanning nozzles, which have different spot sizes for the same beam energies, is assessed.

FIG. 1.

Spot size (one sigma) as a function of energy for both the UN and DN, measured in-air at the isocenter with the Lynx scintillator-based sensor (IBA, Belgium). Data from Kralik et al. (Ref. 6), reuse with the corresponding author courtesy.

A DCS based on two orthogonal pairs of mobile trimmer blades has been previously proposed to provide energy spot specific and layer specific collimation, thus reducing the lateral penumbra and yielding effectively smaller spots.8 The initial study investigating the DCS with the UN was based on 2D data.8,9 In order to extend the study to 3D clinical datasets, laterally asymmetric proton beamlets resulting from collimation have been modeled from mcnpx simulations10 and used to compute 3D dose in a patient geometry through a modification of Hong’s pencil beam algorithm11 as described by Gelover et al.10 This beam model was recently used to compare uncollimated (UNCOL) and collimated brain tumor plans for a UN and the results showed a clinically significant improvement of the organs-at-risk (OAR) sparing through the use of the DCS, with a small penalty in terms of increased treatment time.12

The dosimetric improvement obtained for the brain cases with the UN raised the question of the improvement that could be achieved for the DN, which utilizes a reduced spot size compared to the UN. Thus, this study aims to quantify the target conformity improvement afforded by the DCS for the UN and DN for both brain and head and neck tumor treatments. It is important to note that even though this comparison is specific to two commercially available nozzles, the results can be generalized to any system with similar spot sizes.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.A. Water phantom comparison

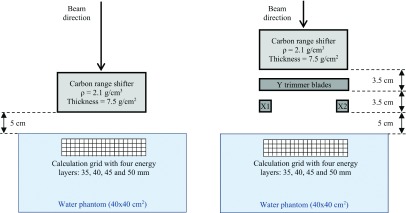

A simple configuration was designed to illustrate the lateral dose falloff for the UN and the DN in a homogenous water phantom. This configuration modeled a 5 × 5 cm2 field with a 5-mm spot spacing, four energy layers placed at 35, 40, 45, and 50 mm water depths, and a 5 cm air gap between the snout exit and the water surface9 (Fig. 2). For comparison, the same plan was also created with trimmer blades in position.

FIG. 2.

Diagram illustrating the simple configuration without (left) and with (right) the DCS.

The weights of the initial proton beam energies were optimized to create a spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP) and cover the 5 × 5 cm2 field while minimizing the dose outside.13

2.B. Clinical datasets

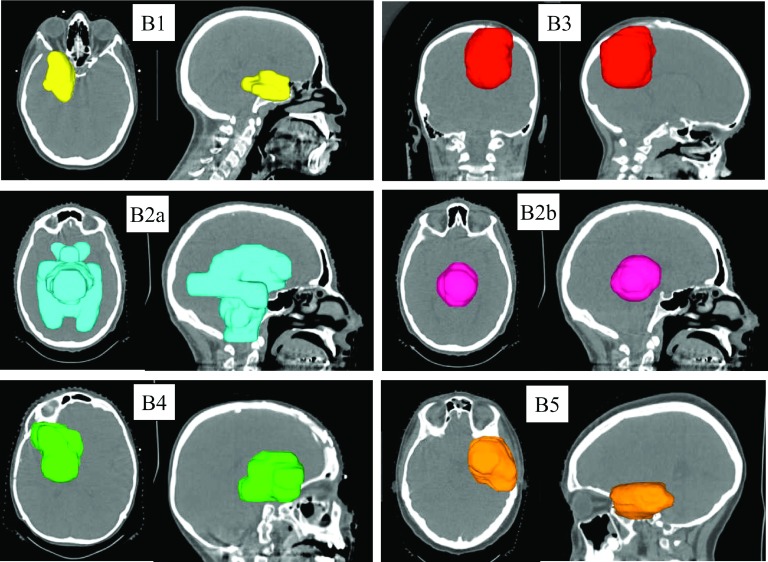

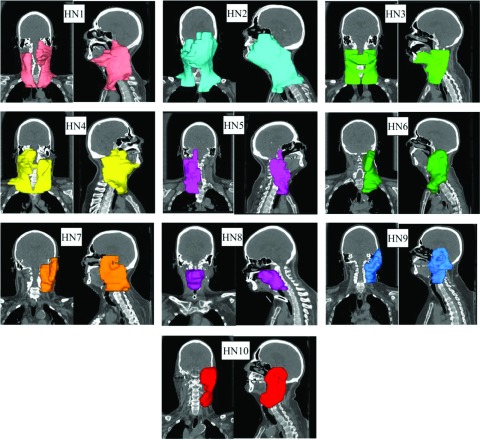

Five brain datasets (one having two targets treated independently: B2a and B2b plans, respectively) and ten head and neck datasets of patients treated by spot scanning proton therapy at the University of Pennsylvania Roberts Proton Therapy Center were selected under an Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved study. The CT images, target outlines, beam angles, and prescription dose were included in these datasets. The target volumes ranged from 42 to 423 cm3 for the brain cases and between 188 and 933 cm3 for the head and neck cases. Four head and neck plans (HN1–HN4) had bilateral targets, one (HN8) had a central target, and the others had unilateral targets. Figures 3 and 4 show the target location of the brain and head and neck tumors, respectively. All treatment plans were optimized as single field optimized (SFO) plans, with the exception of HN2 and HN3 which utilized intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT) to include a boost as clinically planned. The plan characteristics are summarized in Table I.

FIG. 3.

3D views of the target location, size, and shape for the brain cases B#.

FIG. 4.

3D views of the target location, size, and shape for the head and neck cases HN#.

TABLE I.

Plan characteristics.

| Plan | Diagnosis | Beam orientations | Prescribed dose (Gy) | OAR constraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | Chordoma | Apex | 50 | Cord: max 50 Gy Brain stem: max 60 Gy and <5% over 54 Gy Optic chiasm/nerves: max 54 Gy Eyes/cochlea: max 45 Gy, mean 30 Gy Temporal lobes: mean 25 Gy Pituitary gland: max 45 Gy Hippocampus: max 20 Gy Hypothalamus: max 10 Gy |

| Right lateral | ||||

| B2 | Germinoma | Right lateral | a—23.4 | |

| Left lateral | b—21.6 | |||

| B3 | Ependymoma | Apex | 54 | |

| Left superior oblique | ||||

| B4 | Craniopharyngioma | Right lateral | 54 | |

| Right superior oblique | ||||

| B5 | Low grade glioma | Left lateral | 54 | |

| Left superior oblique | ||||

| H1 | Bilateral | Left posterior | 54/60 | Brain stem, optic chiasm and nerves: max 54 Gy Cord and cord + 5 mm: max: 45 and 54 Gy, respectively Mandible-PTV: max 60 Gy Esophagus-PTV/larynx-PTV/oral cavity-PTV: mean 20 Gy Middle ears: mean 30 Gy Ipsilateral parotid gland: mean dose as low as reasonably achievable Contralateral parotid gland: mean 26 Gy Submandibular (uninvolved): mean 39 Gy Temporal lobes: mean 25 Gy Constrictors: mean 50 Gy Constrictors-PTV: mean 40 Gy |

| SCC of the tongue base | Right posterior | |||

| H2 | Bilateral | Left posterior | 59.5/63/70/72.1 | |

| SCC of the left oral tongue | Right posterior | |||

| Left posterior oblique | ||||

| H3 | Bilateral | Left posterior | 54/57/60/63/66 | |

| SCC of the left oral tongue recurred in bilateral neck | Right posterior | |||

| Right posterior oblique | ||||

| Anterior | ||||

| H4 | Bilateral | Left posterior | 54/60 | |

| SCC of the right tonsil | Right posterior | |||

| H5 | Unilateral | Right posterior | 54/60 | |

| SCC of the right pyriform sinus | Posterior | |||

| HN6 | Unilateral | Left anterior oblique | 50.4 | |

| SCC of the left supraglottic larynx | Left posterior oblique | |||

| HN7 | Unilateral | Left anterior oblique | 60/63 | |

| Carcinoma of the left parotid gland | Left posterior oblique | |||

| HN8 | Central | Left posterior oblique | 70 | |

| Recurrent head and neck cancer, involving the oropharynx | Right posterior oblique | |||

| HN9 | Unilateral | Left anterior oblique | 54/60/63 | |

| Recurrent basal cell cancer of the scalp | Left posterior oblique | |||

| Metastatic to the left neck lymph node | ||||

| HN10 | Unilateral | Left lateral | 70.4 | |

| Recurrent SCC of the skin, with spread to the left parotid | Left posterior oblique |

Note: SCC = squamous cell carcinoma; B = brain cases; HN = head and neck cases; and OAR = organs-at-risk.

2.C. Treatment planning system (TPS)

Collimated beamlets for both UN and DN were modeled using mcnpx to create a library in our in-house TPS, RDX. This modeling has been parametrized; the details of the UN model have been published by Gelover et al.10 and the DN model was modeled and validated using a similar approach to that for the UN model. RDX is thus able to calculate both uncollimated and collimated plans for both nozzles, avoiding the inter-TPS variance. Both the uncollimated and collimated models were created with a 5-cm air gap between the last element on the beamline and the patient surface. For the collimated plans, this means that the lower trimmer blades were simulated at 5 cm from the surface, while for the uncollimated plan the range shifter was simulated at 5 cm from the surface. This is the same as shown in Fig. 2 for the water phantom control case.

For both the UN and DN, the uncollimated plans mimicked the clinically delivered prescription dose and the beam angles. The collimated plans were created using the same parameters as the uncollimated plans, except that the collimated beamlets were used. The brain plans were calculated using a spot grid of 4 and 3 mm for the UN and the DN, respectively, while the head and neck plans were calculated using a spot grid of 3 mm for both the UN and DN. No improvement on plan quality was observed for the UN brain cases by reducing the spot grid from 4 to 3 mm. The difference in spot grid for the brain cases was justified by the reduced DN spot size compared to the UN, requiring an increase to the grid resolution. The smaller spot grid of 3 mm was used for all head and neck cases due to the increased complexity of the tumor shape.

2.D. Analyses

In the case of the water phantom, the penumbra width (20%–80%) reductions obtained through the use of the DCS were calculated for both the UN and DN. For the brain and head and neck cases, the comparison of the target conformity between uncollimated and collimated plans for both the UN and DN models was based on the mean dose to a 1-mm thickness ring of healthy tissue surrounding the target at increasing distances ranging from 1 to 10 mm. The reduction of the mean dose to the 10-mm ring surrounding the target between the uncollimated and collimated plans was also calculated for all cases. A student’s t-test was used to assess for significance.

3. RESULTS

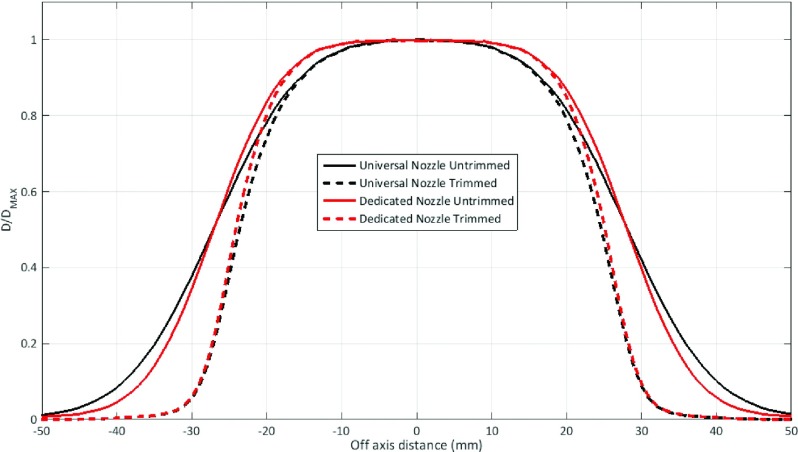

For the control case, the penumbra widths of the uncollimated and collimated plans were 15.4 and 8.2 mm, respectively, for the UN and 12.4 and 7.1 mm, respectively, for the DN (Fig. 5). The penumbra width reductions from the DCS were 46.8% and 42.7% for the UN and DN, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Off-axis dose profiles of uncollimated (untrimmed) and collimated (trimmed) plans with UN and DN of a 5 × 5 cm2 field and 5 cm air gap between the exit window and the water surface. The plans were generated with mcnpx; the profiles were taken at 42-mm depth.

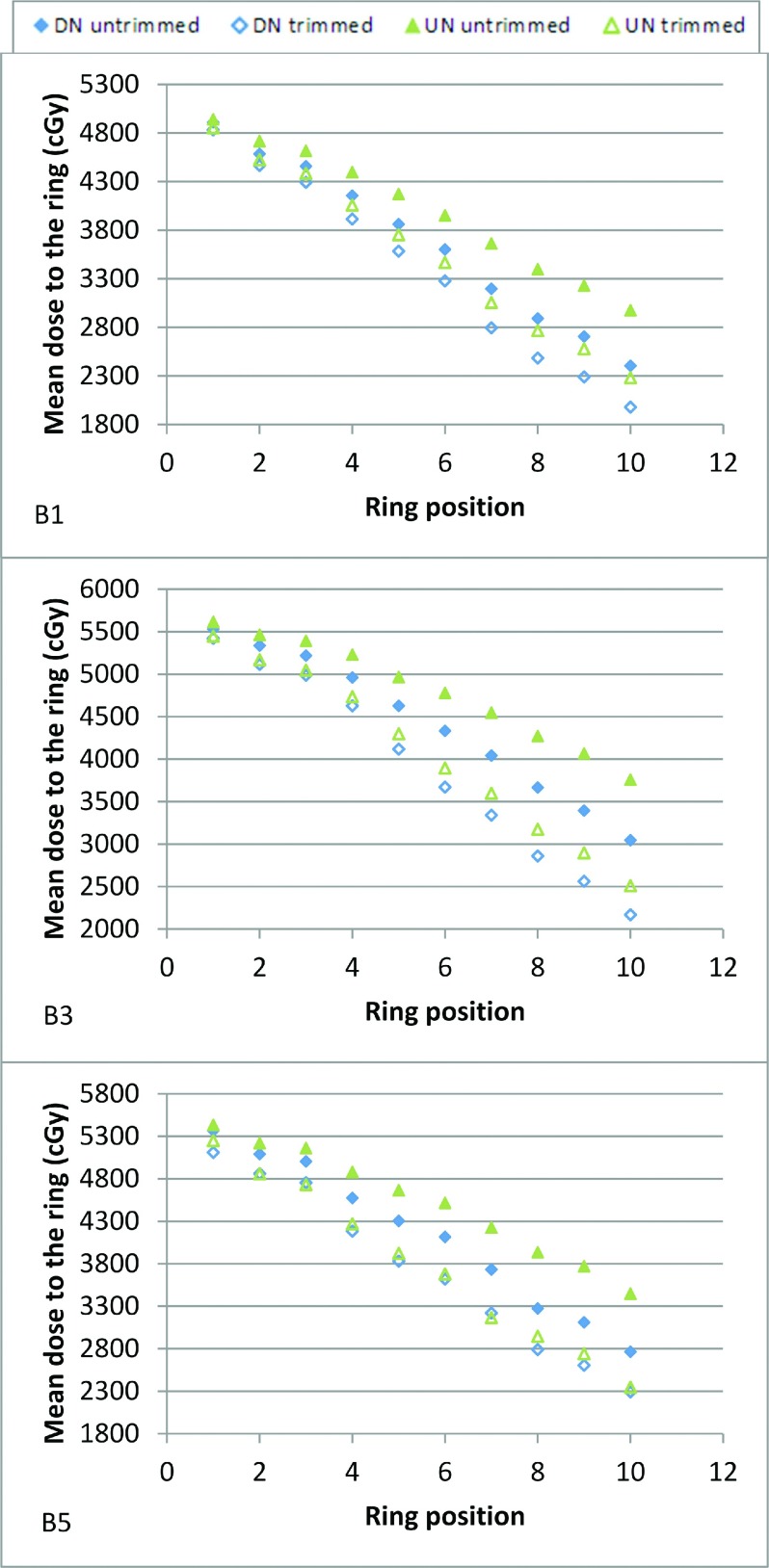

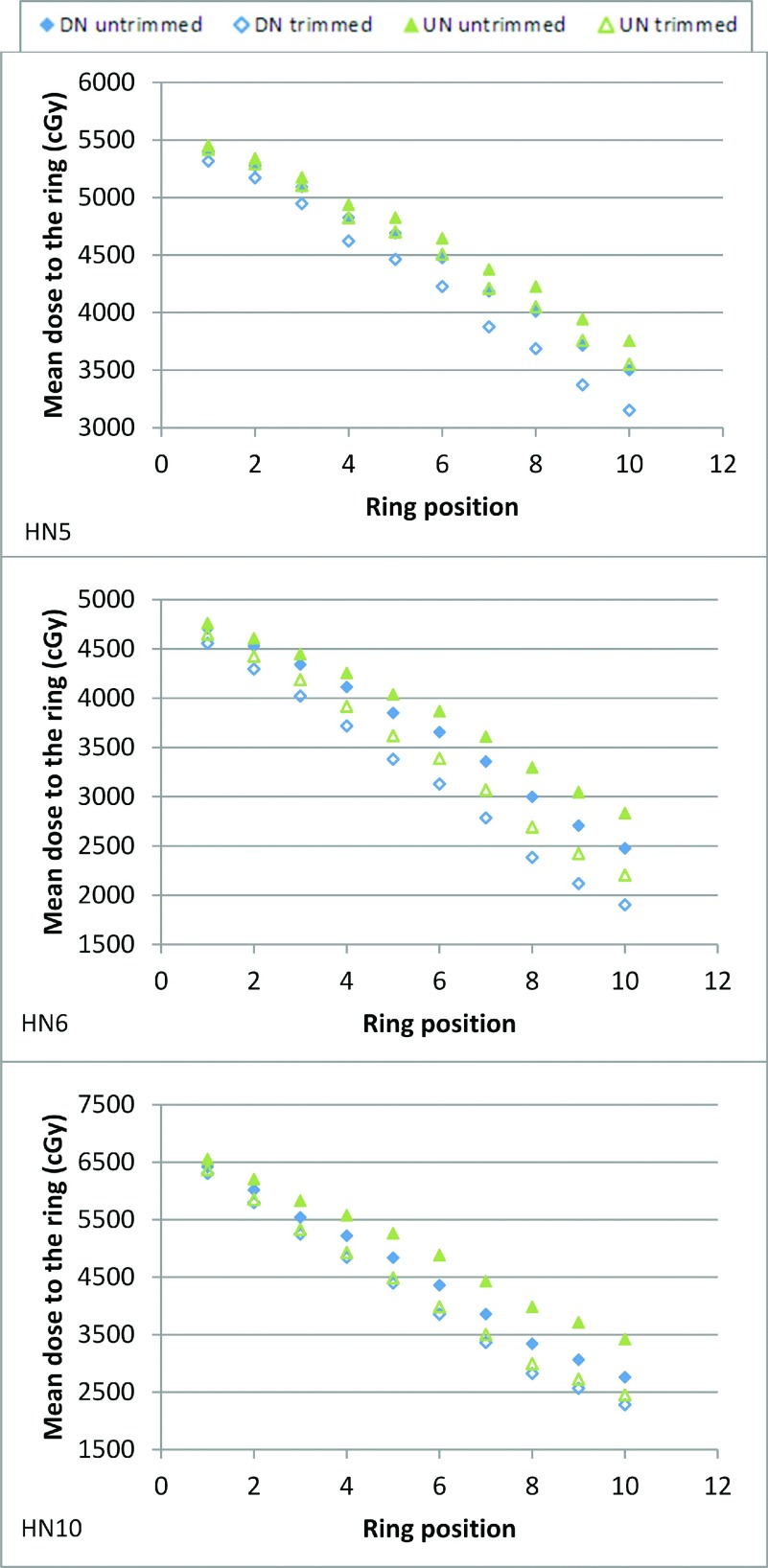

The average reductions of the 10-mm ring mean dose for the UN and DN plans were 13.7% (95% CI: 11.6%–15.7%; p < 0.0001) and 11.5% (95% CI: 9.5%–13.5%; p < 0.0001) across all brain cases and 7.1% (95% CI: 4.4%–9.8%; p < 0.001) and 6.3% (95% CI: 3.7%–9.0%; p < 0.001), respectively, across all head and neck cases.

Figures 6 and 7 show three kinds of results (collimated UN plan equivalent to uncollimated DN plan, collimated UN plan better than uncollimated DN plan, and collimated UN plan equivalent to collimated DN plan) for both brain and head and neck cases; the complete data are given as the supplementary material.14 All uncollimated DN plans demonstrated superior conformity to the uncollimated UN plans. The collimated UN plans were even more conformal than the uncollimated DN plans for all brain cases and 60% of the head and neck cases (HN1, HN4, HN6, HN7, HN9, and HN10); conformity for the other 40% of the head and neck cases (HN2, HN3, HN5, and HN8) was equivalent. The collimated DN plans were more conformal than the collimated UN plans for the majority of the cases; the few exceptions (B2a, B5, and HN10) having minor differences. Table II shows the benefit from collimation for a given OAR of each case for both the UN and DN.

FIG. 6.

Mean dose to 1-mm rings at increasing distances from the target boundary ranging from 1 to 10 mm, for the untrimmed and trimmed plans with both the UN and DN models in brain treatments. B# indicates the plan name.

FIG. 7.

Mean dose to 1-mm rings at increasing distances from the target boundary ranging from 1 to 10 mm, for the untrimmed and trimmed plans with both the UN and DN models in head and neck treatments. HN# indicates the plan name.

TABLE II.

Examples of OAR doses for both UNCOL and COL plans with both the UN and DN, along with the relative difference (REL DIFF).

| UN | DN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plan | OAR | UNCOL (Gy) | COL (Gy) | REL DIFF (%) | UNCOL (Gy) | COL (Gy) | REL DIFF (%) |

| B1 | Left optic nervea | 4.9 | 0.7 | −86 | 2.2 | 0.2 | −93 |

| B2a | Left optic nervea | 17.2 | 12.5 | −28 | 16.8 | 12.7 | −25 |

| B2b | Pituitary glanda | 10.9 | 5.7 | −48 | 2.3 | 0.2 | −11 |

| B3 | Brain stema | 8.7 | 1.6 | −82 | 4.6 | 0.9 | −80 |

| B4 | Right temporal lobeb | 32.6 | 29.9 | −8 | 30.6 | 28.4 | −7 |

| B5 | Pituitary glanda | 19.9 | 10.2 | −49 | 23.1 | 18.0 | −22 |

| HN1 | Left parotid-PTVb | 31.5 | 28.4 | −10 | 27.3 | 27.1 | −1 |

| HN2 | Left optic nervea | 15.0 | 9.9 | −34 | 3.4 | 2.3 | −32 |

| HN3 | Oral cavity-PTVb | 21.0 | 18.1 | −14 | 18.4 | 17.4 | −5 |

| HN4 | Right parotid-PTVb | 33.3 | 29.8 | −11 | 28.5 | 26.9 | −5 |

| HN5 | Right submandibular-PTVb | 40.9 | 35.1 | −14 | 38.4 | 29.6 | −23 |

| HN6 | Corda | 13.9 | 9.0 | −35 | 10.3 | 5.4 | −48 |

| HN7 | Left submandibular-PTVb | 36.5 | 32.9 | −10 | 31.4 | 22.6 | −28 |

| HN8 | Right parotid-PTVb | 35.1 | 32.6 | −7 | 32.3 | 32.0 | −1 |

| HN9 | Left submandibular-PTVb | 36.9 | 35.0 | −5 | 35.6 | 34.8 | −3 |

| HN10 | Left submandibular-PTVb | 38.5 | 31.7 | −18 | 36.7 | 31.6 | −13 |

Maximum physical dose.

Mean physical dose.

The time penalties associated with the use of the DCS with a continuous motion at the maximum velocity advised by the linear motor manufacturer (0.35 m/s) were less than 42 and 84 s for the brain and head and neck cases, respectively.

4. DISCUSSION

The uncollimated DN plans yielded better target conformity than the uncollimated UN plans, as expected given the spot size reported in Fig. 1 and the 2D spot profiles measured by Lin et al.4 for the two nozzles. The DCS systematically afforded an improvement in target conformity for both the UN and DN. Across all brain and head and neck plans, the UN plans had on average a slightly larger relative reduction in the dose surrounding the target than the DN plans. This was consistent with the results obtained in the water phantom. Lin et al.15,16 recently reported that the low dose envelope (halo) component of some off-axis spots might be cut off by upstream collimation components. Although the halo component of spot profiles was not accounted in RDX, the conclusion may remain the same given its magnitude.4,5

Moreover, it was observed that adding DCS to the UN achieved better target conformity than the uncollimated DN in all brain cases and better (60%) or equivalent (40%) target conformity in head and neck cases. Using the penumbra width as target conformity metrics in the control case, the same observation was made. Consequently, the likely low cost of the DCS compared to the nozzle upgrade makes it a powerful tool for improving spot scanning proton therapy dose conformity. In approximately 80% of the cases, the collimated DN yielded better target conformity than the collimated UN, the other cases being equivalent. Regardless of the financial cost, a facility with both a DN and a DCS is thus the optimal configuration in terms of target conformity.

In an earlier proof of concept study,8 it was demonstrated that the main advantages of the DCS as a collimator in spot scanning proton therapy were its ability to provide spot and energy layer specific collimation, a small footprint which would allow a positioning theoretically as close as 5 cm from the patient surface, and its low secondary neutron production through the use of nickel17 trimmer blades. The small air gap between the DCS exit window and the patient surface is essential to maintain the benefit from collimation because of the divergence introduced in the range shifter. This study further demonstrated the dosimetric advantage of the DCS as it provides significant target conformity improvement not only for the UN but also for the DN, at a minimal cost in terms of time penalty (no more than approximately 1.5 min for the largest target with a continuous motion of the trimmer blades at 0.35 m/s). A sensitivity analysis will have to be performed to evaluate the dosimetric impact of an inaccuracy of DCS positioning.

5. CONCLUSION

From this study, we can draw the conclusion that the DCS added to either the UN or DN will improve the target conformity. The DCS is especially of interest for sites with UN systems looking for a more economical solution than upgrading the nozzle since collimated UN plans will be either more conformal than or equivalent to uncollimated DN plans. However, the DCS added to the DN will be the optimal equipment regarding the target conformity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the IBA company (Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium).

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang D., Dirksen B., Hyer D. E., Buatti J. M., Sheybani A., Dinges E., Felderman N., TenNapel M., Bayouth J. E., and Flynn R. T., “Impact of spot size on plan quality of spot scanning proton radiosurgery for peripheral brain lesions,” Med. Phys. 41, 121705 (10pp.) (2014). 10.1118/1.4901260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van de Water T. A., Lomax A. J., Bijl H. P., Schilstra C., Hug E. B., and Langendijk J. A., “Using a reduced spot size for intensity-modulated proton therapy potentially improves salivary gland-sparing in oropharyngeal cancer,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. 82, e313–e319 (2012). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Widesott L., Lomax A. J., and Schwarz M., “Is there a single spot size and grid for intensity modulated proton therapy? Simulation of head and neck, prostate and mesothelioma cases,” Med. Phys. 39, 1298–1308 (2012). 10.1118/1.3683640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin L., Ainsley C. G., Solberg T. D., and McDonough J. E., “Experimental characterization of two-dimensional spot profiles for two proton pencil beam scanning nozzles,” Phys. Med. Biol. 59, 493–504 (2014). 10.1088/0031-9155/59/2/493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin L., Ainsley C. G., and McDonough J. E., “Experimental characterization of two-dimensional pencil beam scanning proton spot profiles,” Phys. Med. Biol. 58, 6193–6204 (2013). 10.1088/0031-9155/58/17/6193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kralik J., Xi L., Solberg T. D., Simone C. B., and Lin L., “Comparing proton treatment plans of pediatric brain tumors in two pencil beam scanning nozzles,” J. Appl. Clin. Med. Phys. 16, 41–50 (2015). 10.1120/jacmp.v16i6.5389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowdell S. J. et al. , “Monte Carlo study of the potential reduction in out-of-field dose using a patient-specific aperture in pencil beam scanning proton therapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 57, 2829–2842 (2012). 10.1088/0031-9155/57/10/2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyer D. E., Hill P. M., Wang D., Smith B. R., and Flynn R. T., “A dynamic collimation system for penumbra reduction in spot-scanning proton therapy: Proof of concept,” Med. Phys. 41, 091701 (9pp.) (2014). 10.1118/1.4837155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyer D. E., Hill P. M., Wang D., Smith B. R., and Flynn R. T., “Effects of spot size and spot spacing on lateral penumbra reduction when using a dynamic collimation system for spot scanning proton therapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 59, N187–N196 (2014). 10.1088/0031-9155/59/22/N187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelover E., Wang D., Hill P. M., Flynn R. T., Gao M., Laub S., Pankuch M., and Hyer D. E., “A method for modeling laterally asymmetric proton beamlets resulting from collimation,” Med. Phys. 42, 1321–1334 (2015). 10.1118/1.4907965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong L., Goitein M., Bucciolini M., Comiskey R., Gottschalk B., Rosenthal S., Serago C., and Urie M., “A pencil beam algorithm for proton dose calculations,” Phys. Med. Biol. 41, 1305–1330 (1996). 10.1088/0031-9155/41/8/005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moignier A., Gelover E., Wang D., Smith B., Flynn R., Kirk M., Lin L., Solberg T., Lin A., and Hyer D., “Theoretical benefits of dynamic collimation in pencil beam scanning proton therapy for brain tumor: Dosimetric and radiobiological metrics,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys. (in press). 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.David J. and Weimin C., “Creating a spread-out Bragg peak in proton beams,” Phys. Med. Biol. 56, N131–N138 (2011). 10.1088/0031-9155/56/11/n01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1118/1.4942375 E-MPHYA6-43-041603 for target conformity improvement obtained with the DCS for each plan with both the UN and DN.

- 15.Lin L., Ainsley C. G., Mertens T., De Wilde O., Talla P. T., and McDonough J. E., “A novel technique for measuring the low-dose envelope of pencil-beam scanning spot profiles,” Phys. Med. Biol. 58, N171–N180 (2013). 10.1088/0031-9155/58/12/N171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin L., Huang S., Kang M., Solberg T. D., McDonough J. E., and Ainsley C. G., “Technical note: Validation of halo modeling for proton pencil beam spot scanning using a quality assurance test pattern,” Med. Phys. 42, 5138–5143 (2015). 10.1118/1.4928157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brenner D. J., Elliston C. D., Hall E. J., and Paganetti H., “Reduction of the secondary neutron dose in passively scattered proton radiotherapy, using an optimized pre-collimator/collimator,” Phys. Med. Biol. 54, 6065–6078 (2009). 10.1088/0031-9155/54/20/003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1118/1.4942375 E-MPHYA6-43-041603 for target conformity improvement obtained with the DCS for each plan with both the UN and DN.