High enantioselectivities can be achieved using an appropriate chiral base/achiral ligand combination in Pd0-catalyzed C(sp3)–H activation.

High enantioselectivities can be achieved using an appropriate chiral base/achiral ligand combination in Pd0-catalyzed C(sp3)–H activation.

Abstract

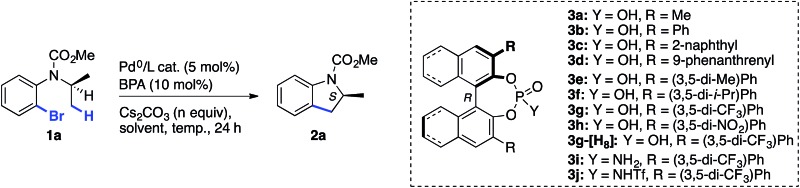

The first efficient palladium(0)-catalyzed enantioselective C(sp3)–H activation reaction using a catalytic chiral base and an achiral phosphine ligand is reported. Fine-tuning the binol-derived phosphoric acid pre-catalyst and the reaction conditions was found to be crucial to achieve high levels of enantioselectivity for a variety of indoline products containing both tri- and tetrasubstituted stereocenters.

Introduction

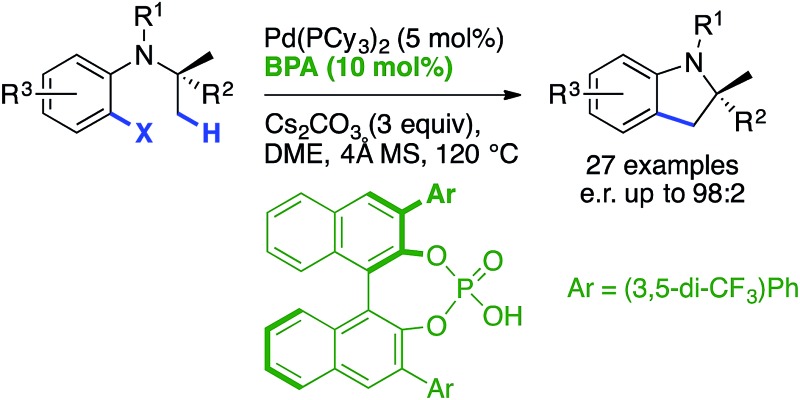

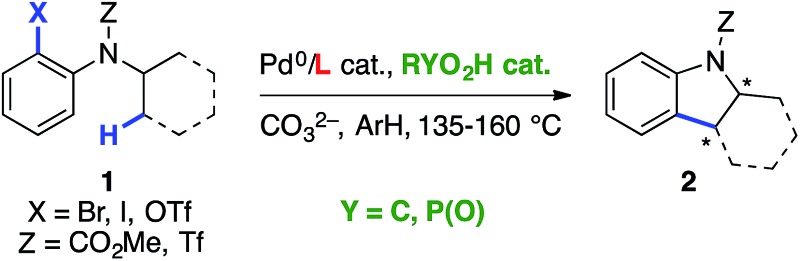

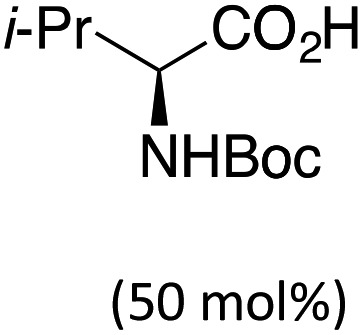

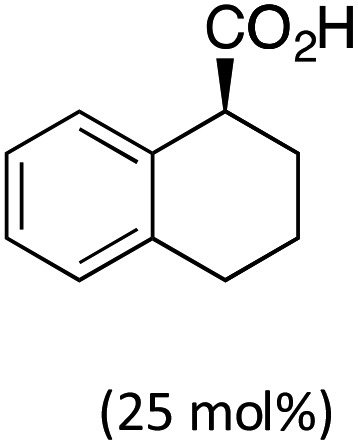

Transition-metal catalysis has developed as a powerful tool to activate otherwise unreactive C(sp3)–H bonds and create a variety of carbon–carbon and carbon–heteroatom bonds.1,2 In this context, our group3 as well as others4 have reported the construction of a diverse array of fused carbocycles and heterocycles via intramolecular palladium(0)-catalyzed arylation of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds from aryl halides. In the last five years, enantioselective versions of these reactions have been disclosed. In particular, the groups of Kündig,5 Kagan,6 and Cramer7a reported the highly enantioselective construction of (fused) indolines using chiral N-heterocyclic carbene or phosphine ligands (Table 1, entry 1). In parallel, we have reported the diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of (fused) indanes containing up to three adjacent stereocenters by using chiral Binepine ligands.8 Computational mechanistic studies indicated that the C–H bond cleavage occurs through proton abstraction by the coordinated base, usually either a carbonate or an in situ generated carboxylate (concerted metalation-deprotonation mechanism).3b,c,4f,h,5c,d,9,10 In this scenario, not only the ancillary ligand, but also the base should be able to interact with the substrate via non-covalent bonding, and hence induce stereoselective C–H bond cleavage. The possibility that enantioselectivity can be achieved solely using a chiral base was already explored in the above-mentioned work by Kagan6 and Cramer.7a Indeed, the former observed an e.r. of 65 : 35 in the presence of 50 mol% of Boc-valine in the absence of an ancillary ligand (entry 2), whereas the latter reported an e.r. of 71 : 29 using a chiral tetralinecarboxylic acid and an achiral NHC ligand (entry 3).11,12 In both cases the indoline product was, however, obtained in low yield.

Table 1. Chiral ligand- vs. chiral base-catalyzed asymmetric C(sp3)–H arylation a .

| ||||

| Entry | L | Brønsted acid RYO2H | e.r. (yield) | ref. |

| 1 | Chiral NHC or phosphine | Achiral RCO2H | Up to 99 : 1 | Kündig5 |

| Up to 97 : 3 | Kagan6 | |||

| Up to 98 : 2 | Cramer7a | |||

| 2 | None |

|

65 : 35 (Traces) | Kagan6 |

| 3 | IPr |

|

71 : 29 (20%) | Cramer7a |

| 4 | PCy3 | 3,3′-CF3Ph-BPA | Up to 98 : 2 | This work |

aIPr = 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)-1,3-dihydro-2H-imidazol-2-ylidene; BPA = binol-derived phosphoric acid.

Encouraged by these precedents, we looked for a suitable chiral Brønsted acid pre-catalyst, which upon in situ deprotonation with a stoichiometric inorganic base, would allow the achievement of both efficiency and high enantioselectivity. Our attention turned toward binol-derived phosphoric acids (BPAs), which are readily available, and have proven to be competent stereochemical inducers in other types of reactions involving cooperative catalysis with Pd complexes,13,14 and, as shown recently by Duan and co-workers, in PdII-catalyzed directed asymmetric C(sp3)–H arylation.15 When the current work was in progress, the same group reported two examples of Pd0-catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of indolines using the simplest BPA, devoid of substituents at the 3,3′-positions, with a moderate e.r. and yield.16

Herein, we show that high levels of enantioselectivity and efficiency can be obtained through the careful choice of BPA substituents and optimization of reaction conditions (entry 4).

Results and discussion

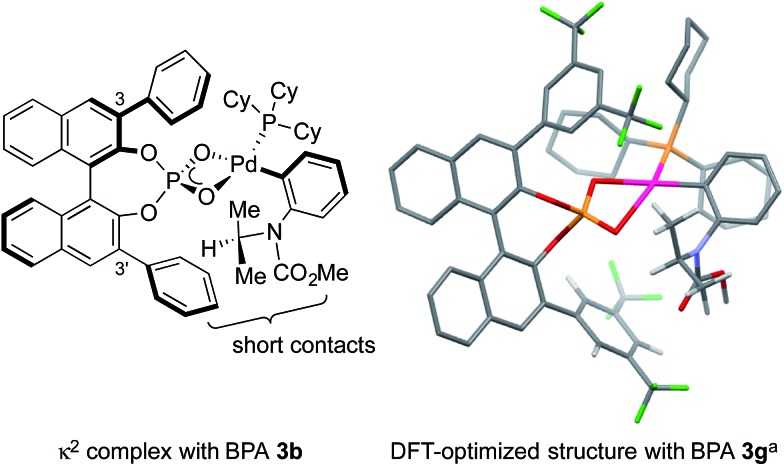

We set out to explore the asymmetric C–H arylation of prototypical substrate 1a bearing enantiotopic methyl groups (Table 2). The well-defined Pd(PCy3)2 complex (5 mol%) was initially chosen as catalyst to minimize the effect of additional ancillary ligands or anions. In order to have a blueprint for the design of an efficient BPA catalyst, we considered the putative κ2-coordinated intermediate13g derived from 3,3′-disubstituted BPAs, which would undergo C–H activation via a phosphate-induced CMD mechanism (Fig. 1, left). In this crude model, a 3′-aryl substituent would sit below the N-isopropyl and CO2Me groups of the substrate, thereby enabling non-covalent interactions. Fig. 1 (right) shows the DFT-optimized structure of the κ2 complex with the optimal (vide infra) BPA 3g, which provides a more accurate picture. According to this model, the modulation of the steric and/or electronic properties of the 3,3′-aryl substituents could allow the introduction of enantioselectivity by discriminating the two enantiotopic methyl groups of the N-isopropyl residue.

Table 2. Optimization of reaction conditions.

| |||||||

| Entry | BPA | Catalyst a | n | Solvent | Temp. (°C) | e.r. of 2a b | Yield of 2a c (%) |

| 1 | 3a | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 52 : 48 | 80 |

| 2 | 3b | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 50 : 50 | 65 |

| 3 | 3c | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 54 : 46 | 68 |

| 4 | 3d | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 52 : 48 | 71 |

| 5 | 3e | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 57 : 43 | 39 |

| 6 | 3f | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 56 : 44 | 45 |

| 7 | 3g | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 80 : 20 | 50 |

| 8 | 3h | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 57 : 43 | 50 |

| 9 | 3g-[H8] | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 140 | 50 : 50 | 63 |

| 10 d | 3g | Pd(PCy3)2 | 1.5 | Xylenes | 120 | 87 : 13 | 24 |

| 11 | 3g | Pd(PCy3)2 | 3 | Xylenes | 120 | 84 : 16 | 56 |

| 12 | 3i | Pd(PCy3)2 | 3 | Xylenes | 120 | 84 : 16 | 50 |

| 13 | 3j | Pd(PCy3)2 | 3 | Xylenes | 120 | 55 : 45 | 15 |

| 14 | 3g | Pd(PCy3)2 | 3 | DME e | 120 | 96 : 4 | 86 |

| 15 | — | Pd(PCy3)2 | 3 | DME e | 120 | — | 29 |

| 16 | 3g | Pd2(dba)3 | 3 | DME e | 120 | — | <2 f |

| 17 | 3g | Pd2(dba)3/PCy3 | 3 | DME e | 120 | 95 : 5 | 61 |

| 18 | 3g | Pd2(dba)3/PPh3 | 3 | DME e | 120 | 91 : 9 | <20 f |

| 19 | 3g | Pd2(dba)3/PCyp3 | 3 | DME e | 120 | 97 : 3 | 24 |

| 20 | 3g | Pd2(dba)3/P(t-Bu)2Me | 3 | DME e | 120 | 97 : 3 | <20 f |

a5 mol% Pd(PCy3)2 (entries 1–15) or 2.5 mol% Pd2dba3/10 mol% PR3 (entries 16–20).

bEnantiomeric ratio measured via HPLC using a chiral stationary phase.

cYield of isolated product.

dReaction time: 40 h.

eWith 4 Å powdered molecular sieves.

fEstimated based on GCMS ratio. DME = 1,2-dimethoxyethane.

Fig. 1. Structural basis for the design of BPA catalysts. aPBE0-D3/Def2SVP, SMD; most H atoms are omitted for clarity.

Following this hypothesis, an array of 3,3′-disubstituted BPAs were synthesized from (R)-binol according to literature procedures17 and were tested as catalysts (10 mol%) in combination with stoichiometric cesium carbonate in xylenes. The most representative results are shown in Table 2.18 The nature of the 3,3′-substituents was indeed found to be crucial, with methyl (entry 1), phenyl (entry 2) or extended aryl groups (entries 3–4) leading to very low levels of enantioselectivity.

meta-Substituents on the 3,3′-phenyl rings led to the first interesting results (entries 5–8). The highest e.r. (80 : 20) was obtained with commercially available BPA 3g bearing meta-CF3 substituents (entry 7),19 which performed much better than the sterically comparable isopropyl (entry 6) or likewise electron-withdrawing nitro (entry 8) groups. As shown with the partially hydrogenated analogue 3g-[H8] (entry 9), the dihedral angle of the binaphthyl system seems to be a critical factor as well. Decreasing the temperature to 120 °C enabled a significant increase in the e.r., albeit at the expense of the yield (entry 10, compared with entry 7). We hypothesized that the low solubility of cesium carbonate in xylenes and the resulting incomplete deprotonation of the BPA was responsible for the observed low reactivity at 120 °C. Gratifyingly, increasing the amount of Cs2CO3 to 3 equiv. allowed an increase in the yield to 56% (entry 11). Modulating the acidity of the BPA20 by synthesizing phosphoramides 3i–j was met with little success (entries 12–13). In contrast, a major improvement was found when using DME as the solvent. Moreover, the addition of 4 Å molecular sieves proved beneficial, leading to compound 2a in excellent yield and e.r. (entry 14). It is worth noting that a slow but significant background racemic reaction occurred with cesium carbonate alone, in the absence of BPA (entry 15). Among all of the stoichiometric bases tested in combination with catalytic acid 3g, cesium carbonate proved to be optimal. Finally, the effect of the ancillary ligand was investigated in combination with Pd2dba3 (entries 16–20). No reaction occurred without phosphine ligand (entry 16), and PCy3 furnished the highest reactivity (entry 17) among the tested monophosphines. It is noteworthy that the in situ combination of Pd2dba3 and PCy3 provided the same e.r. as the well-defined Pd(PCy3)2 complex, but the latter was found to be a more active catalyst (compare entries 14 and 17). Hence, under optimal conditions, indoline 2a was obtained in 86% yield and 96 : 4 e.r. (entry 14). The (S) absolute configuration of the major enantiomer was ascribed via X-ray diffraction analysis of a derivative (vide infra). These levels of reactivity and selectivity are comparable to those obtained on the same substrate with the chiral ancillary ligand approach.21

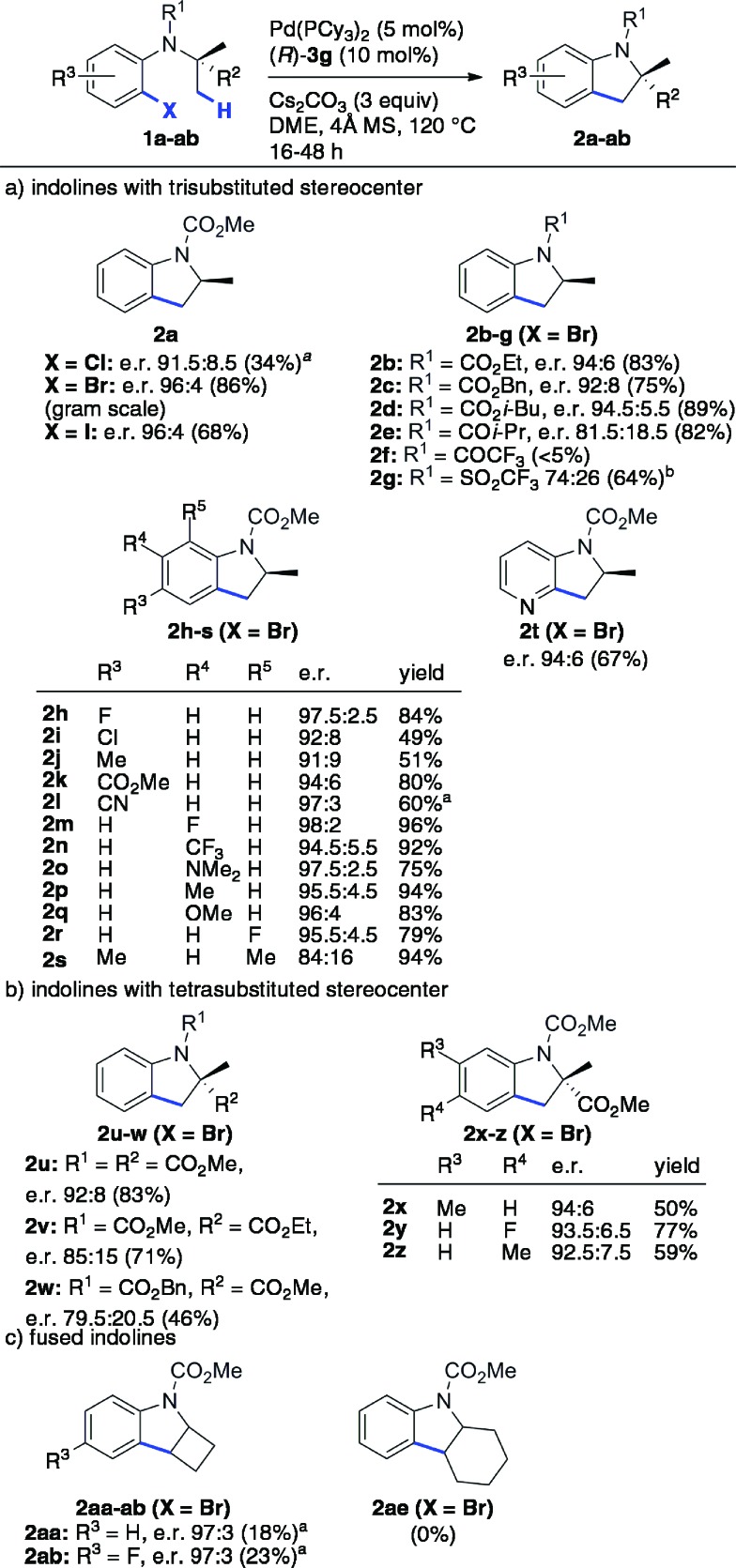

The scope and limitations were next studied under these optimized conditions (Scheme 1), starting with reactants bearing a trisubstituted carbon adjacent to the nitrogen atom (R2 = H, Scheme 1a). Among the different tested halides (X = Cl, Br, I), the bromide was found to be optimal. Importantly, the reaction could be performed from 1.36 g (5 mmol) of the latter with equal efficiency and stereoselectivity. From the corresponding iodide, the e.r. was similar (96 : 4) but the yield was significantly lower (68%). The chloride was less reactive under the same conditions, and lower yield and e.r were obtained even at 140 °C. The effect of the nitrogen substituent (R1) was next investigated (indolines 2b–g). Carbamates were found to be optimal (2a–d), whereas other groups gave rise to lower yields (2f–g) and enantioselectivities (2e, 2g). This important effect of the nitrogen substituent is consistent with the model described in Fig. 1, which shows the proximity of the CO2Me group with the 3′-aryl substituent of the BPA.

Scheme 1. Scope and limitations of the enantioselective C(sp3)–H arylation reaction. The shown absolute configurations of the major enantiomers were deduced from those of 2a and 2u (see Scheme 3). a Performed at 140 °C. b Performed at 100 °C.

In addition, the reaction was found to tolerate electronically diverse substituents at various positions (R3–R5) on the aromatic ring (2h–s), including ester (2k), cyano (2l) and amino (2o) groups. High yields and e. r. were obtained for all of the substrates except for those bearing Me or Cl substituents at the C-5 (R3) and C-7 (R5) positions of the indoline ring, which seem to be more sensitive. In addition to indolines, azaindoline 2t was obtained with satisfying yield and stereoselectivity.

So far, both the chiral ligand5–7 and the chiral base approaches allow access to scalemic indolines containing a trisubstituted stereocenter. In addition to these compounds, interesting new types of indolines were targeted (Scheme 1b and c). First, indoline 2u containing a tetrasubstituted stereocenter was obtained with good yield and e.r., despite the more crowded environment of the enantiotopic methyl groups. Interestingly, the carbonyl substituents on the adjacent carbon (2v) and nitrogen (2w) atoms were found to have a significant impact on both the yield and enantioselectivity, with smaller methoxycarbonyl groups being optimal (2u). Gratifyingly, substituted analogues of 2u (2x–z) were obtained with comparable enantioselectivity. The current method represents a simple enantioselective route to these valuable tetrasubstituted amino acid precursors, which does not involve chemical or enzymatic resolution.22

Various indolines fused to five-, six- and seven-membered rings have been synthesized via enantioselective C–H arylation in the presence of chiral ligands.5a,c,6,7a In contrast, a single example of fused indoline-cyclobutane has been reported in its racemic form by Fagnou and co-workers.23 Using our optimized conditions, compounds 2aa and 2ab were obtained with high enantioselectivity (e.r. 97 : 3), albeit in low isolated yield due to significant competing proto-dehalogenation (Scheme 1c). Under the same conditions, the formation of cyclohexane-fused indoline 2ae was not observed. In contrast, chiral NHC ligands allowed the production of the same product in high yield and enantioselectivity.5a Overall, as shown with compounds 2aa–ab and 2ae, the current Pd/PCy3/BPA catalytic system does not seem to be sufficiently reactive to efficiently activate secondary C–H bonds.

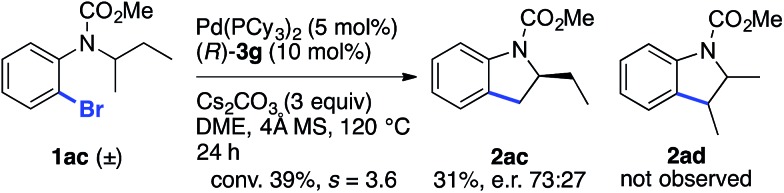

The reaction of racemic substrate 1ac was also examined, in order to look for a possible kinetic resolution phenomenon (Scheme 2). With the same substrate and using a chiral NHC ligand, Kündig and co-workers observed a regiodivergent behavior, with each enantiomer of 1ac being transformed into a different enantioenriched product, 2ac or 2ad, resulting from the activation of the Me and Et group, respectively.5b Under our standard conditions, we observed only the formation of compound 2ac arising from the activation of the Me group, and an e.r. of 73 : 27 was measured at 39% conversion (s = 3.6).24 Hence, these two different chiral systems show a different behavior, with the chiral BPA giving rise to modest kinetic resolution.

Scheme 2. Study of the kinetic resolution of a racemic substrate.

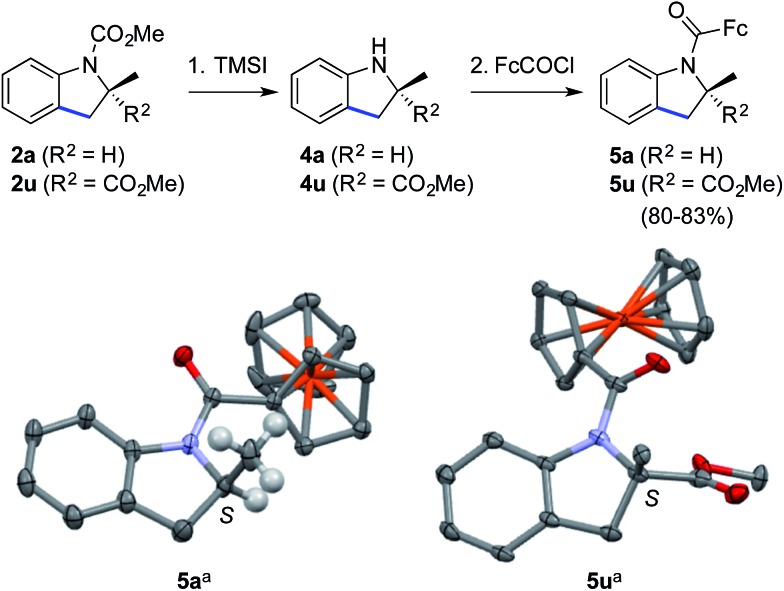

Finally, the methyl carbamate in indolines containing a tri- (2a) or tetrasubstituted (2u) stereocenter could be cleaved upon treatment with trimethylsilyl iodide,25 thus leading to valuable scalemic secondary amines 4a and 4u (Scheme 3). The latter were derivatized as ferrocenecarboxamides, according to our recently published method,8b to give amides 5a and 5u in excellent overall yield. The crystal structures of the corresponding major enantiomers were solved using X-ray diffraction analysis,26 thereby allowing us to independently confirm the S configuration of 2a 6,27 and to ascribe the S configuration for 2u.18

Scheme 3. Cleavage of the carbamate group and determination of absolute configurations. Reaction conditions: (1) (i) TMSI (10 equiv.), CHCl3, reflux; (ii) MeOH, reflux (only for 4u); and (2) for 5a: FcCOCl (1.1 equiv.), i-Pr2NEt (3 equiv.), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (0.1 equiv.), CH2Cl2, 0 → 20 °C, 83% for 2 steps; for 5u: LiN(SiMe3)2 (1.2 equiv.), FcCOCl (1.2 equiv.), THF, –78 → –10 °C, 80% for 2 steps. TMSI = trimethylsilyl iodide; Fc = ferrocene. a Thermal ellipsoids at the 30% probability level, most H atoms are omitted for clarity.26 .

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have reported the first highly enantioselective and efficient palladium(0)-catalyzed C(sp3)–H activation reaction using a chiral catalytic base instead of a chiral ancillary ligand. A fine tuning of both the BPA catalyst and the reaction solvent was key to achieve high levels of enantioselectivity for a variety of indoline products containing both tri- and tetrasubstituted stereocenters. Further applications of this concept will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007–2013/ under REA grant agreement no. 623605, and by the University of Basel. We thank Dr Eric Clot, Université Montpellier 2, for DFT calculations.

Footnotes

References

- Selected reviews: ; (a) Jazzar R., Hitce J., Renaudat A., Sofack-Kreutzer J., Baudoin O. Chem.–Eur. J. 2010;16:2654. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Baudoin O. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4902. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15058h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li H., Li B.-J., Shi Z.-J. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2011;1:191. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dastbaravardeh N., Christakakou M., Haider M., Schnürch M. Synthesis. 2014;46:1421. [Google Scholar]; (e) Hartwig J. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudoin O., in Catalytic Transformations via C–H Activation, ed. J.-Q. Yu, Science of Synthesis, Georg Thieme Verlag KG, Stuttgart-New York, 2015, vol. 2, pp. 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Selected examples: ; (a) Baudoin O., Herrbach A., Guéritte F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:5736. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chaumontet M., Piccardi R., Audic N., Hitce J., Peglion J.-L., Clot E., Baudoin O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15157. doi: 10.1021/ja805598s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rousseaux S., Davi M., Sofack-Kreutzer J., Pierre C., Kefalidis C. E., Clot E., Fagnou K., Baudoin O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10706. doi: 10.1021/ja1048847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sofack-Kreutzer J., Martin N., Renaudat A., Jazzar R., Baudoin O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:10399. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Janody S., Jazzar R., Comte A., Holstein P. M., Vors J.-P., Ford M. J., Baudoin O. Chem.–Eur. J. 2014;20:11084. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Dailler D., Danoun G., Baudoin O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:4919. doi: 10.1002/anie.201500066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Holstein P. M., Dailler D., Vantourout J., Shaya J., Baudoin O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:2805. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For pioneering work: ; (a) Dyker G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1992;31:1023. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dyker G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1994;33:103. [Google Scholar]; (c) Catellani M., Motti E., Ghelli S. Chem. Commun. 2000:2003. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dong C.-G., Hu Q.-S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:2289. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ren H., Knochel P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:3462. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lafrance M., Gorelsky S. I., Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14570. doi: 10.1021/ja076588s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Watanabe T., Oishi S., Fujii N., Ohno H. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1759. doi: 10.1021/ol800425z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Rousseaux S., Gorelsky S. I., Chung B. K. W., Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10692. doi: 10.1021/ja103081n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Tsukano C., Okuno M., Takemoto Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:2763. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Piou T., Neuville L., Zhu J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:11561. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Yan J.-X., Li H., Liu X.-W., Shi J.-L., Wang X., Shi Z.-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:4945. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Nakanishi M., Katayev D., Besnard C., Kündig E. P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:7438. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Katayev D., Nakanishi M., Bürgi T., Kündig E. P. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:1422. [Google Scholar]; (c) Larionov E., Nakanishi M., Katayev D., Besnard C., Kündig E. P. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:1995. [Google Scholar]; (d) Katayev D., Larionov E., Nakanishi M., Besnard C., Kündig E. P. Chem.–Eur. J. 2014;20:15021. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anas S., Cordi A., Kagan H. B. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:11483. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14292e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ; for the asymmetric synthesis of other fused ring systems, see: ; (a) Saget T., Lemouzy S. J., Cramer N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:2238. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Saget T., Cramer N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:12842. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pedroni J., Boghi M., Saget T., Cramer N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:9064. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Pedroni J., Saget T., Donets P. A., Cramer N. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:5164. doi: 10.1039/c5sc01909e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Pedroni J., Cramer N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:11826. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Martin N., Pierre C., Davi M., Jazzar R., Baudoin O. Chem.–Eur. J. 2012;18:4480. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Holstein P. M., Vogler M., Larini P., Pilet G., Clot E., Baudoin O. ACS Catal. 2015;5:4300. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann L. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1315. doi: 10.1021/cr100412j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kefalidis C. E., Baudoin O., Clot E. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:10528. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00578a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In addition, a cooperative effect was demonstrated using a monoprotected tert-leucine and a chiral phosphine.7a

- For pioneering work with chiral monoprotected aminoacids in asymmetric PdII-catalyzed C–H functionalization: ; (a) Shi B.-F., Maugel N., Zhang Y.-H., Yu J.-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:4882. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Engle K. M., Yu J.-Q. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:8927. doi: 10.1021/jo400159y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selected examples: ; (a) Alper H., Hamel N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2803. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mukherjee S., List B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11336. doi: 10.1021/ja074678r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jiang G., Halder R., Fang Y., List B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:9752. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chai Z., Rainey T. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:3615. doi: 10.1021/ja2102407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ohmatsu K., Ito M., Kunieda T., Ooi T. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:473. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Yu S.-Y., Zhang H., Gao Y., Mo L., Wang S., Yao Z.-J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:11402. doi: 10.1021/ja405764p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhang D., Qiu H., Jiang L., Lv F., Ma C., Hu W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:13356. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Wang P.-S., Lin H.-C., Zhai Y.-J., Han Z.-Y., Gong L.-Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:12218. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Banerjee D., Junge K., Beller M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:13049. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Jiang T., Bartholomeyzik T., Mazuela J., Willersinn J., Bäckvall J.-E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:6024. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Nelson H. M., Williams B. D., Miró J., Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:3213. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews: ; (a) Philipps R. J., Hamilton G. L., Toste F. D. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:603. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mahlau M., List B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:518. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Inamdar S. M., Shinde V. S., Patil N. T. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:8116. doi: 10.1039/c5ob00986c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.-B., Zhang S., Duan W.-L. Org. Lett. 2015;17:2458. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E.r. 75 : 25, 47% yield for indoline 2a, and e.r. 83.5 : 16.5, 39% yield for indoline 2ae: Zhang S., Lu J., Ye J., Duan W.-L., Chin. J. Org. Chem., 2016, 36 , 752 . [Google Scholar]

- ; review: ; (a) Akiyama T., Itoh J., Yokota K., Fuchibe K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:1566. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Uraguchi D., Terada M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5356. doi: 10.1021/ja0491533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kampen D., Reisinger C. M., List B. Top. Curr. Chem. 2009;291:395. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-02815-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See the ESI for details.

- (a) Akiyama T., Morita H., Itoh J., Fuchibe K. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2583. doi: 10.1021/ol050695e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rueping M., Sugiono E., Azap C., Theissmann T., Bolte M. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3781. doi: 10.1021/ol0515964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmees K., Tolstoluzhsky N., Raja S., Rueping M., Leito I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:11569. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- With Me-Duphos: 97% yield, e.r. 96.5 : 3.5;6 with a chiral NHC: 86% yield, e.r. 95 : 5.5b

- . For the enantioselective synthesis of tetrasubstituted indolines via other approaches: ; (a) Corey E. J., McCaully R. J., Sachdev H. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970;92:2476. doi: 10.1021/ja00711a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhou F., Guo J., Liu J., Ding K., Yu S., Cai Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14326. doi: 10.1021/ja306631z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cai Q., Zhou F. Synlett. 2013:408. [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu J., Yan J., Qin D., Cai Q. Synthesis. 2014:1917. [Google Scholar]; (e) Miyazaki Y., Ohta N., Semba K., Nakao Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:3732. doi: 10.1021/ja4122632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseaux S., Liégault B., Fagnou K. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:244. [Google Scholar]

- Selectivity factor calculated as s = log[1 – c(1 + ee2ac)]/log[1 – c(1 – ee2ac)], where c = conversion of 1ac

- Jung M. E., Lyster M. A. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1978:315. [Google Scholar]

- CCDC 1486752 (5a) and ; 1486753 (5u) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper.

- Bertini Gross K. M., Jun Y. M., Beak P. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7679. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.