Abstract

Rationale

Accurate assessment of medication adherence is critical for determination of medication efficacy in clinical trials, but most current methods have significant limitations. This study tests a sub-therapeutic (microdose) of acetazolamide as a medication ingestion marker, because acetazolamide is rapidly absorbed and excreted without metabolism in urine and can be non-invasively sampled.

Methods

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, residential study, ten volunteers received 15 mg oral acetazolamide for four consecutive days. Acetazolamide pharmacokinetics were assessed on Day 3, and its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions with a model medication (30 mg oxycodone) were examined on Day 4. The rate of acetazolamide elimination into urine was followed for several days after dosing cessation.

Results

Erythrocyte sequestration (half-life= 50.2±18.5h, mean±SD, n=6), resulted in the acetazolamide microdose exhibiting a substantially longer plasma half-life (24.5±5.6 h, n=10) than previously reported for therapeutic doses (3–6 h). Following cessation of dosing, the rate of urinary elimination decreased significantly (F(3,23)=247: p<0.05, n=6) in a predictable manner with low inter-subject variability and a half-life of 16.1±3.8h (n=10). For each of four consecutive mornings after dosing cessation, the rates of urinary acetazolamide elimination remained quantifiable.

There was no overall effect of acetazolamide on the pharmacodynamics, Cmax, Tmax or elimination half-life of the model medication tested. Acetazolamide may have modestly increased overall oxycodone exposure (20%, p<0.05) compared with one of the two days when oxycodone was given alone, but there were no observed effects of acetazolamide on oxycodone pharmacodynamic responses.

Conclusions

Co-formulation of a once-daily trial medication with an acetazolamide microdose may allow estimation of the last time of medication consumption for up to 96h post-dose. Inclusion of acetazolamide may, therefore, provide an inexpensive new method to improve estimates of medication adherence in clinical trials.

Keywords: Acetazolamide, adherence marker, ingestion marker, erythrocyte sequestration

INTRODUCTION

Clinical trials assessing the efficacy of pharmacotherapeutics generally assume (but frequently do not confirm) that participants take the test medication as instructed1, even though the accuracy of this supposition is critical for correct interpretation of a trial outcome. Detailed medication adherence data are essential to ensure that unanticipated low medication exposure is not mistaken for therapeutic inefficacy2, but adherence data can also provide other critical information. For example, some initial adverse effects dissipate with consistent dosing and so adherence data can reveal associations between adverse events and intermittent adherence3. In addition, the availability of adherence data for both active and placebo trial arms can reveal medication tolerability problems that might otherwise remain hidden1.

Adherence has often been examined using subject self-reports and/or pill counts, but these techniques have been shown to substantially overestimate actual adherence3–5 as they do not confirm medication consumption. Plasma and/or urine monitoring for active drug or metabolites can confirm ingestion in some trial arms, but provides no information on placebo adherence rates. This limitation restricts the ability to monitor for drug tolerability issues and to compare the “time to discontinuation” between trial arms. Furthermore, some studies have shown treatment effects related to adherence rather than pharmacology6, but such effects can only be detected when adherence data are available for all trial arms. Adherence to both active and placebo medications can be examined by compounding the test medication with an ingestion marker such as riboflavin, which can be detected in a subject’s urine. Riboflavin is safe and relatively inert, but its dietary presence limits its utility and riboflavin is rapidly eliminated, so that a single missed daily dose can be indistinguishable from persistent non-compliance7–9.

Because of the limitations in the existing methods of adherence assessment and the considerable significance of adherence monitoring to clinical trial data interpretation, we sought to develop a new ingestion marker. We identified candidate markers by first defining a set of key optimal characteristics. A candidate compound should be inexpensive, simple to analyze using standard techniques and extractable from a matrix that can be sampled in a minimally invasive manner and where its concentration parallels that of blood in real-time, e.g. urine or saliva. An optimal candidate should be approved for use in humans and should not be present physiologically or in dietary sources / common medications. Viable candidates should produce no pharmacological or toxicological effects when used for a prolonged period at a dose that can be tracked for several days after dosing cessation. Absorption and elimination of a marker should be predictable, dose-linear and not affected by the presence of food, dietary or genetic makeup, age or environmental influences such as smoking or alcohol consumption. The marker should not affect the pharmacokinetic (PK) or pharmacodynamic (PD) profile of the test medication and the rate of marker elimination should be consistent with a commonly used dosing interval (once or twice a day (QD, BID respectively). Finally a subject who has missed one dose of medication should be distinguishable from one who has skipped several doses. These latter criteria may be achieved by using a low-potency drug as a marker in order for a dose to be established that yields a sufficiently high concentration in plasma and urine to allow quantification for a prolonged period after dosing cessation, but exhibits no pharmacological effects or interactions with the test medication.

The pool of compounds initially considered as candidates mainly consisted of US Food and Drug Agency (FDA)-approved medications, as the information needed to evaluate their suitability is typically available in the FDA-approved drug label. Acetazolamide [ACZ] and quinine were identified as two candidate compounds, which largely fit the above criteria. This report describes the PK and urinary elimination characteristics for ACZ, Acetazolamide is a carbonic anhydrase (CA) inhibitor that has been used for >50 years to treat glaucoma, edema, epilepsy and altitude sickness at daily doses ranging from 250–750 mg 10,11. Most of the reported drug interactions with ACZ result from alteration of bicarbonate concentration (bicarbonaturia and hypokalemia) 10 and are “on-target” effects that would not be expected to occur at sub-therapeutic doses. Acetazolamide is a sulfonamide, but it is structurally distinct from allergenic sulfa-antimicrobials and adverse reactions are rare12,13. Acetazolamide is not metabolized and is directly eliminated into urine14, providing some degree of promise for low inter-subject variability rates of urinary excretion.

This report describes the PK and rate of urinary excretion of a 15 mg ACZ microdose (equivalent to 6% of the recommended starting therapeutic dose14). The data examining quinine using similar methods has been published elsewhere15. In addition, the interaction of ACZ on PK/PD outcomes was assessed with a model test medication. Here, oxycodone was used as the model medication because it produces clear subjective and observer-rated pharmacodynamic effects and is eliminated partially in urine16 so that renal interactions with ACZ might be identified.

METHODS

Study Design

Acetazolamide and quinine were evaluated as potential new adherence markers in the same 15-day project conducted at the UK Center for Clinical and Translational Science Inpatient Unit, using a within-subject, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design. The data reported here represent data taken during the phase in which ACZ was evaluated (the first 9 days). Between days 9–15 quinine was evaluated using the same subjects and essentially the same experimental design; the results of that study phase, along with details of the study design, the subjects, and sample analyses have been published15. What follows are protocol, analytical and methods details which are particular to the ACZ study, notably due to changes made as a result of an interim analysis of samples and data from Subjects 1–4. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kentucky.

Drug Formulation

The study was conducted under a US FDA Investigator-initiated IND (69,214) using drug doses formulated by the University of Kentucky Investigational Pharmacy. Tablets of ACZ (125 mg, Taro Pharmaceutical Industries, Hawthorne, NY) were crushed and an equivalent of 15 mg ACZ together with lactose monohydrate powder (Medisca Pharmaceuticals, Plattsburgh, NY) was used to loose-fill size 00 gelatin capsules (Health Care Logistics, Circleville, OH). In vitro dissolution studies (Murty Pharmaceuticals, Lexington, KY) were conducted to confirm that the lactose excipient did not affect the ACZ dissolution profile. The placebo capsules contained only lactose.

Dosing and Sampling Schedule

Oxycodone (30 mg, p.o.) was administered on Days 1, 5 and 8 (10 AM), while ACZ (15 mg, p.o.) was given on days 2–5 (9 AM). On Day 5 when interactions between the two drugs were examined, ACZ was administered 1 h prior to oxycodone (9 AM and 10 AM respectively) in order to align their expected peak effects14,16. On study days, collected urine was combined over the following collection periods 7:00 AM–12PM, 12–3PM, 3–6PM, 6–9PM, 9PM–6:30AM. On non-study days (Days 2, 3, 6, 7) the collection periods were 7:00 AM – 3PM, 3–9PM and 9PM–6:30AM. At the end of each time period, the volume was measured, samples were mixed, and a 10-mL aliquot was frozen at −80° C. Data are reported as ACZ excretion per hour (µg /h), averaged over each collection period. For the first four subjects, urine was collected and analyzed for 48h after the final dose, but with subjects 5–10 urine was collected and analyzed for 96h after the final ACZ dose.

Pharmacodynamic Outcomes: Participant- and Observer-Rated Measures

An array of physiological, subjective and observer-rated measures were collected throughout each test session as previously described15 to capture the pharmacodynamic effects of oxycodone, acetazolamide and their combination. Side effects were also queried daily using a checklist that contained acetazolamide specific side effects from the package label (ringing in the ears, blurry vision, numbness in hands or feet, tingling sensations in hands or feet, numb or tingling sensation in mouth and metallic taste in mouth) and oxycodone effects. Side effects were also queried in an open-ended manner daily.

Sample preparation and analytical methods

Sampling procedures and estimation of erythrocyte content

Plasma and urine samples were collected as previously described15. Whole blood samples (0.5mL) were pipetted from the collection vacutainer prior to centrifugation into a cryovial and frozen at −80° C.

Sample Preparation-ACZ in Plasma and Whole Blood

Plasma or whole blood (100µl) was mixed with 50 µL of 50% methanol containing 20 ng of ACZ internal standard (IS: 2H3 15N-ACZ), 20 µL of 10% formic acid in acetonitrile and 1 mL tertbutyl methyl ether. Samples were vortex-mixed, centrifuged, frozen and the organic layer was dried under a stream of nitrogen. Plasma extracts were then reconstituted in 0.2 mL of mobile phase (see below) and 5 −10 µL were injected onto the liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometer (LC-MS). Blood extracts were reconstituted in 30 µL methanol and 170 µL of 0.05% formic acid in water was added. Samples (20–40 µL) were injected onto the LC-MS column.

Sample Preparation-ACZ in Urine

Acetonitrile (250 µl) containing 100 ng of IS was added to 50 µL of urine, and samples were transferred to autosampler vials, and samples (15–30 µL) were injected onto the LC-MS column.

Sample Preparation- Oxycodone in Plasma

Samples were prepared as previously described15.

Chromatographic Methodologies

Acetazolamide in plasma, whole blood and urine samples were separated using an isocratic mobile phase over a BDS Hypersil C18 column (5 µm, 4.6 × 100 mm) at room temperature with a mobile phase consisting of methanol:water:formic acid (15:85:0.05, v:v:v) with 2.5 mM ammonium formate at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Quantification was conducted by selective-ion monitoring under positive ionization by atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) modes using a LC-MS/MS system. The monitored m/z ratios for ACZ and the IS were 223 – 181 and 227 – 183 respectively and the standard curve ranges for ACZ in blood and plasma were 10 to 4000 ng/mL, with a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 10 ng/mL and in urine the range was 50–20000 ng/mL with an LLOQ of 50 ng/mL. Oxycodone analysis was conducted as previously described15.

Pharmacodynamic Analyses

Pharmacodynamic data were analyzed as previously described15

Pharmacokinetic Analyses

One- and two-compartment pharmacokinetic models (WinNonlin® software, Pharsight®, Certara, L.P) were used to examine the absorption and elimination of ACZ and oxycodone rather than non-compartmental analyses. The optimal number of compartments to model elimination from each matrix (blood, plasma, urine) was chosen by comparing the mean Akaike Information Criteria arising out of each analysis. This method, known as Akaike weight (AW) analysis17, assesses which model was most likely to have generated the data set.

ACZ carryover subtraction

Microdoses of ACZ (unexpectedly) took longer than 24 h to clear from blood and plasma, confounding the comparative studies examining PK interactions between ACZ and oxycodone, which were conducted on consecutive Days 4 and 5. This issue was overcome by subtracting the residual from the previous day’s dose from each measured data point prior to analysis. These residuals (“C”) were calculated using a standard monoexponential decay formula (C = C0 e−kt), where “Co” is the ACZ concentration immediately before the daily dose (trough value), (“t”) is the time elapsed since dosing and “k” is the elimination constant calculated from an initial analysis of uncorrected data.

This method was also used to enable visualization of ACZ transfer from plasma to RBCs on Day 5 by precluding the residual ACZ in RBCs..

Statistical analyses

Statistical differences between ACZ PK parameters following dosing on Days 4 and 5 were examined using a two-tailed paired “t”-test, as they assessed the influence of oxycodone on ACZ PK on consecutive days in the same subjects. For similar reasons, a repeated measures 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to compare the PK parameters for oxycodone / noroxycodone pharmacokinetics assessed in the absence (Day 1,8) and presence (Day 5) of ACZ. Each of the three days were compared to each other to ensure that any differences were truly due to the treatment rather than due to a small sample size. Repeated measures 1-way ANOVAs with Tukey’s post-hoc test were also used to compare daily urinary “trough values” for ACZ following cessation of dosing. Comparisons of the PK parameters between RBCs and plasma PK parameters after dosing on Day 5 were examined using a two-tailed Student “t”-test as these represent distinct tissue types, not matched pair samples. In all cases significance was established by a “p” value of < 0.05.

Changes in sampling procedures after the interim analysis

The protocol for subjects 1–4 was designed based on previous studies14,18, that indicated most ACZ would be cleared within 24 h of dosing; the PK of ACZ alone was assessed on Day 4 and in combination with oxycodone on Day 5 with the final plasma sample drawn 24 h after dosing. An interim analysis of samples from these first four subjects revealed that the ACZ microdose was being eliminated more slowly than expected based on previously published studies14,18. Consequently the protocol was modified for remaining enrollees to include additional plasma sampling at 48, 72 and 96 h after the final ACZ dose on Day 5. Similarly urine collection was extended to 96 h after administration of the final ACZ dose (compared with 48 h for subjects 1–4).

The interim analysis also indicated an unexpected biphasic elimination of ACZ from plasma. Because ACZ is an inhibitor of CAs which are concentrated in red blood cells (RBCs)19,20, whole blood samples were collected in parallel with plasma sampling for Subjects 5–10. The ACZ content in red blood cells (RBCs ) contained within a milliliter of blood was calculated at each time point by formula: RBCs = Blood-[plasma*(1-hematocrit/100)]21.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

Twelve participants were enrolled, although data from 2 participants were not analyzed; one subject was omitted due to a pharmacy dose error and another was discharged early due to a need for daily allergy medications. The analyzed data represent samples taken from 2 Caucasian women, 1 African American/Caucasian male and 7 Caucasian males. Subjects were 31.1 (±4.7) years old and reported using opioids for 11.2 (±4.8) days of the 30 days prior to enrollment as well as alcohol (5.2 [±4.1] days; n=5); benzodiazepines (1.8 [±0.8] days; n=5), cocaine (1.5 [±1] days; n=4); amphetamines (6 days; n=1); and marijuana (18.3 [±10.5] days; n=7). Eight participants smoked cigarettes (average 16.1 cigarettes /day (±4.7).

Acetazolamide Pharmacokinetics in Plasma

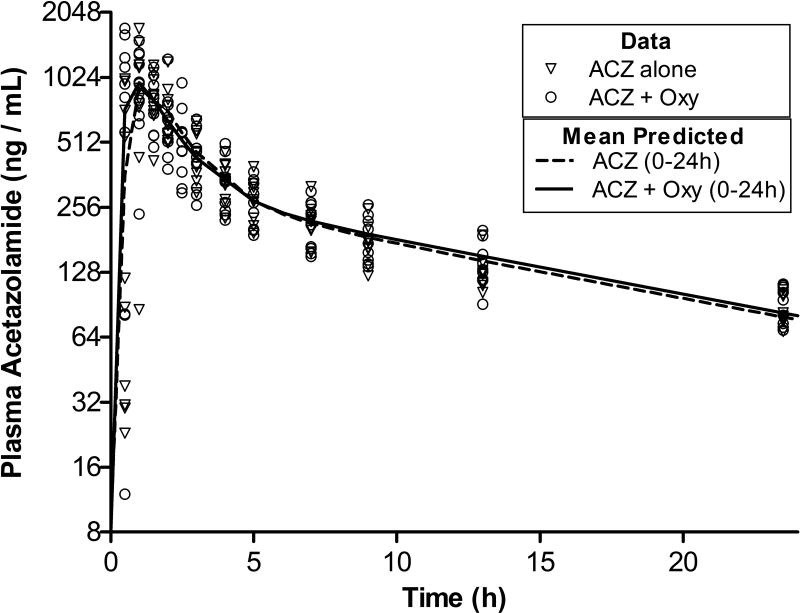

Absorption was rapid with plasma maximum concentrations (Cmax) occurring within 1 h of administration (Fig. 1). Data were analysed by both one- and two-compartment pharmacokinetic analyses and in each case AW analysis indicated a >1000-fold prediction that the plasma data were derived from a two-compartment system (data not shown). The mean analysis parameters describing the absorption and elimination profiles of ACZ and as well as exposure over time, as indicated by the mean Area Under the Curves (AUC) are presented in Table 1. The initial rate of ACZ elimination was rapid, (alpha t1/2< 1h), but after 4–6 h elimination slowed considerably with a beta t1/2 of 12–13 h (Fig 1). Co-administration of oxycodone did not affect the plasma PK parameters of ACZ p>0.05).

Figure 1. Pharmacokinetics of Acetazolamide in Plasma.

Concentration of acetazolamide (ACZ) in plasma following administration of 15 mg of ACZ alone (Day 4, triangles, n=10) and in ACZ in the presence of 30 mg of oxycodone (Day 5, circles, n=10). The residuum from the previous day’s dose was subtracted from each data point (see methods). The lines represents mean predicted data points generated by pharmacokinetic model fit of individual data sets. The dashed line represents ACZ when administered alone and samples taken between t=0–24 h are included. The solid line represents ACZ concentration data from when ACZ was administered together with oxycodone (Oxy).

Table 1.

Mean pharmacokinetic parameters from two-compartment analysis of acetazolamide (ACZ) in plasma when administered alone or in combination with oxycodone (Oxy). Data used in the assessment was collected over 24 h period after administration.

| ACZ alone (0–24h) | ACZ+Oxy (0–24h) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| α-Half-life | h | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.2 |

|

Area-under the-Curve |

h*ng/ml | 6735 | 910 | 6832 | 1331 |

| β-Half-life | h | 13.1 | 3.3 | 12.3 | 1.7 |

| Cmax | ng/ml | 1313 | 527 | 1285 | 381 |

| Tmax | h | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

Individual data points are shown on Fig. 1. Last sample drawn at t=24 h

Acetazolamide Pharmacokinetics in Blood and Erythrocytes

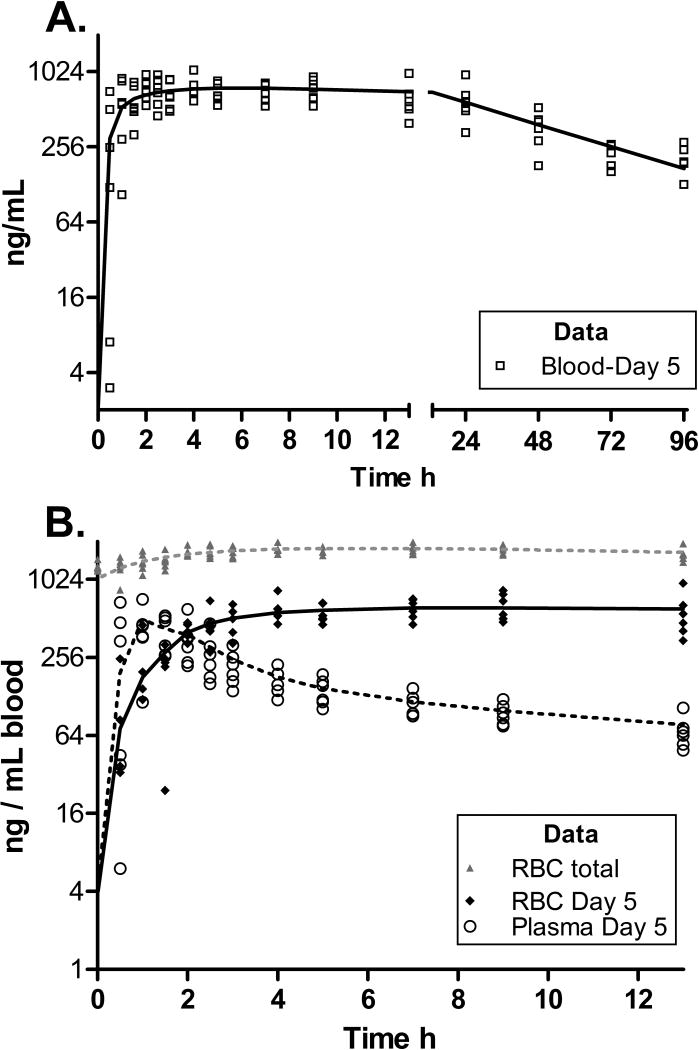

Pharmacokinetic analysis of ACZ in blood for 96 hours after the last dose allowed for full assessment of its PK in the central compartment and its rate of elimination into urine, the primary compartment of interest for ACZ as an adherence marker. The ACZ PK in blood components are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2 where values from whole blood (1 mL) are presented alongside that of the plasma and RBC fractions of that same blood volume. In order to clearly visualize the kinetic transfer of ACZ between plasma and RBCs, the residual ACZ accumulated over the three previous days of dosing was subtracted from each value. To ensure that the magnitude of RBC accumulation of ACZ is not obscured by this transformation, the total RBC concentration data is also included in both Fig. 2 and Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean pharmacokinetic parameters for acetazolamide in blood, plasma and Red Blood Cells (RBCs). Data were collected for 96 after administration. Plasma was analysed by two-compartment analysis, blood and RBCs were analysed by one-compartment analysis.

| Blood* | Mean | S.D. | RBCs (minus residuum)* | Mean | S.D. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Area under Curve |

ng/ml*h | 52130 | 7792 |

Area under Curve |

ng/mlblood*h | 49555 | 11068 |

| Half-life | h | 42.4 | 11.3 | Half-life | h | 50.2 | 18.5 |

| Cmax | ng/ml | 776 | 134 | Cmax | ng/ml | 636.1 | 133.1 |

| Tmax | h | 4.8 | 2.9 | Tmax | h | 7.5 | 3.2 |

| Plasma* | Mean | S.D. | |||||

|

Area under Curve |

ng/mlblood*h | 5568 | 2799 | RBCs (total)# | Mean | S.D. | |

| α-Half-life | h | 0.9 | 0.3 |

Area under Curve |

ng/mlblood*h | 133107 | 17980 |

| β-Half-life | h | 24.5 | 5.6 | Cmax | ng/ml | 1787.3 | 115.9 |

| Cmax | ng/ml | 660 | 387 | Hematocrit | % | 47 | 5.0 |

| Tmax | h | 1.0 | 0.4 | ||||

Mean PK parameters representing 1 ml blood samples drawn following the final dose of acetazolamide (in the presence of oxycodone; n=6). Plasma data are corrected to represent the content in 1 mL of blood according to individual hematocrits. RBC data are calculated as 1 mL blood minus plasma contribution. Individual data points are shown in Fig. 2.]

Parameters were generated from data after subtraction of previous day’s residual ACZ.

Parameters were generated from data without subtraction of previous day’s residual ACZ. Individual data points are shown in Fig. 2B.

Figure 2. The Pharmacokinetic Profiles (PK) of Acetazolamide in 1 mL of blood, and the plasma and Red Blood Cells (RBCs) components of 1 mL of blood (n=6).

The lines represents mean predicted data points generated by pharmacokinetic model fit of individual data sets. Residual ACZ from the previous day’s dose was subtracted from all data points, except the grey “RBC Total” data.

A) Changes in ACZ concentration in whole blood over a 96 h period following administration of the final ACZ (+ oxycodone) dose. The left X axis represents t=0–13 h (for comparison with 2B) while the right X axis, represents t=13–96 h. The line represents mean predicted data based on a fit of a one compartmental pharmacokinetic model optimized for each individual data set.

B) Changes in ACZ concentration in the plasma and red blood cells (RBCs) fractions of 1 mL of blood over a 13 h period following ACZ + oxycodone administration. The open markers represent individual plasma content in 1 mL of blood (corrected using subjects hematocrit values). The dotted line represents mean predicted data based on a two compartmental PK model fit of plasma data. The diamond markers represent individual RBC values (calculated as blood-plasma) and the solid line represents mean predicted data based on a one compartmental PK model fit of RBC data. The grey markers and line represent individual RBC values without the residual subtraction and are intended to demonstrate the degree of accumulation in RBCs after 4 daily doses and how residual subtraction facilitates visualization of the kinetics.

The AW analyses indicated the likelihood that RBCs and blood PK are adequately described by a single exponent. The concentration of ACZ in plasma peaked and fell rapidly (plasma Tmax = 1h, Fig 2b), while RBCs slowly but steadily accumulated ACZ throughout the plasma alpha elimination phase (Tmax= 7.5h). Overall, blood levels remained fairly constant for some time after plasma Cmax (Fig 2A).

The rate of ACZ elimination from RBCs (t1/2=50.2 ± 18.5h, Table 2) was considerably slower than from plasma (β t1/2 =24.5±5.6h, (t(df=10)=2.94, p<0.05, Table 2) resulting in a very high RBC exposure relative to plasma (49555 vs 5568 ng/ml*h, t(df=10) =9.4, p<0.05, Table 2). The degree of RBC sequestration is particularly evident when the cumulative RBC exposure on Day 5 is compared with that after residual subtraction (133107 vs 49555 h*ng/mlblood).

Acetazolamide Pharmacokinetics in Urine

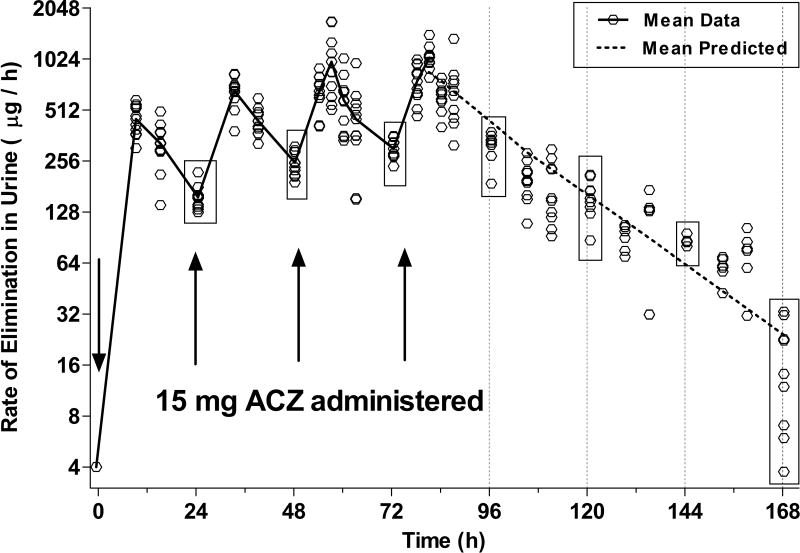

The urine samples collected between 9PM and morning awakening (6–8:30 AM, prior to daily ACZ dose administration) were pooled and were considered a “trough value” for the rate of ACZ output. These trough values increased with each of the first three days of dosing (Fig 3: 24h=157±27, 48h=251±43, 72h=302±39 µg/h ±SD, overall F(3,35)=31.5, p<0.05), demonstrating accumulation between doses; however, the rates prior to the final dose were not significantly different from those collected 24 h later (72h=302±39 96h= 321±58 µg/h ±SD, p>0.05, Fig 4), suggesting an approach to steady-state. The AW analysis of urinary PK data collected up to 96h after dosing cessation suggested a single-compartment model was sufficient to fit the data. PK parameters are presented in Table 3, and individual data are shown in Fig 3. The decline in rate of urinary ACZ excretion exhibited a t1/2 of 16 h and was steady with low inter-subject variability. The mean rates of elimination (±SD) at 24–96 h after the final dose (corresponding to 96, 120, 144 and 168 hrs in Fig 3) were 321±58, 156±40, 86±5 & 17±11 µg/h, respectively. After dosing cessation, each daily trough value was significantly different from its preceding and proceeding equivalent (F(3,23)=247p<0.05 and Tukey p<.05).

Figure 3. Urinary Excretion Rate of Acetazolamide.

Each marker indicates the excretion rate of a single individual, calculated from a sample pooled since the previous collection period (n=10, except for 120–159h when n=6). The solid line connects actual mean values at each time point during the period in which ACZ was administered. The dotted line represents mean predicted data based on a one compartmental pharmacokinetic model fit of each subject’s data from t= 72–168 h). The boxes enclose all of the observed “trough” values on each morning and are intended to highlight the variance range.

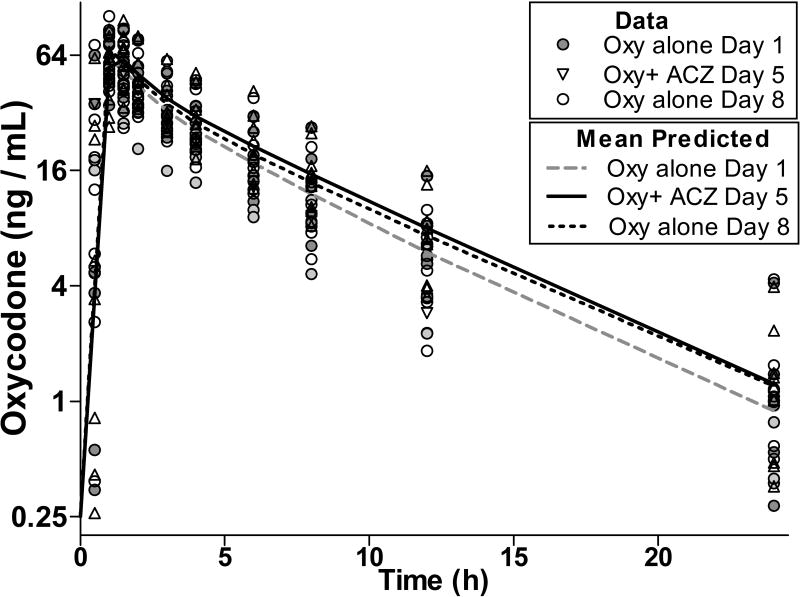

Figure 4. Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Oxycodone in Plasma.

Concentration of Oxycodone (Oxy) in plasma following administration of Oxy alone on Days 1 (grey circles, n=10) and Day 8 (open circles, n=10) and in combination with acetazolamide (Day 5, triangles, n=10). Lines represent mean predicted data based on a two compartmental pharmacokinetic model fit of individual plasma data with the fit optimized for each data set.

Table 3.

Mean pharmacokinetic parameters from one compartment analyses of the urinary excretion rate after administration of the final acetazolamide dose.

| Excretion Rate | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Half-life (h) | 16.1 | 3.8 |

| Cmax (ug/h) | 669 | 183 |

| Tmax (h) | 7.2 | 1.8 |

Mean parameters of 1 compartmental analyses of urinary data from samples produced during the 96 h period after administration of the final acetazolamide dose (in combination with oxycodone. n=9). Individual data points are shown on Fig 3 as the 72 −168 h time points.

Oxycodone Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

The PK of oxycodone was best described by a two-compartment model on each of the three test days (Fig 4, Table 4). When administered in the presence of ACZ (Day 5) Tmax, Cmax or beta t1/2 of oxycodone was not different (p>0.05) than when oxycodone was given alone on Days 1 and 8. While the alpha t1/2 for oxycodone on Day 5 was not different (P>0.05) to that observed on Day 1, it was modestly longer than on Day 8 (0.2±0.1 h compared with 0.14±0.06 h, overall F(2,29)=4.1, p<0.05). Similarly, the AUC of oxycodone given in combination with ACZ on Day 5 was not different to that observed on Day 8 (P>0.05), but the AUC on Day 5 was slightly larger (20 ± 11%, overall F(2,29)=18.2, p<0.05) than when oxycodone was given alone on Day 1. Noroxycodone, a primary metabolite of oxycodone was also examined and the mean PK parameters arising out of the data analyses are reported in Table 4. The PK of noroxycodone was best described by a single-compartment model, and there were no differences in any of the PK parameters in the presence or absence of ACZ.

Table 4.

Mean pharmacokinetic parameters from two-compartment analysis of oxycodone (Oxy) and one-compartment analysis of noroxycodone in plasma following administration of oxycodone alone (Days 1 and 8) or in combination with acetazolamide (ACZ, Day 5).

| Oxycodone | Oxy Alone-D1 | Oxy+ ACZ-D5 | Oxy Alone-D8 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| α-Half-life | h | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1♦ | 0.1 |

|

Area under Curve |

h*ng/ml | 281.1♦ | 124.4 | 341.3 | 120 | 318.6 | 128.2 |

| β-Half-life | h | 3.9 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 1.1 |

| Cmax | ng/ml | 61.6 | 17.1 | 71.4 | 17.6 | 68.5 | 16.8 |

| Tmax | h | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.3 |

| Noroxycodone | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

|

Area under Curve |

h*ng/ml | 224 | 83 | 218 | 84 | 213 | 76 |

| Half-life | h | 4.3 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 1.2 |

| Cmax | ng/ml | 34.9 | 9.3 | 30 | 1.7 | 30.2 | 9.8 |

| Tmax | h | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

The values marked with a diamond (♦) are significantly different (p<0.05) from their equivalent value on Day 5.

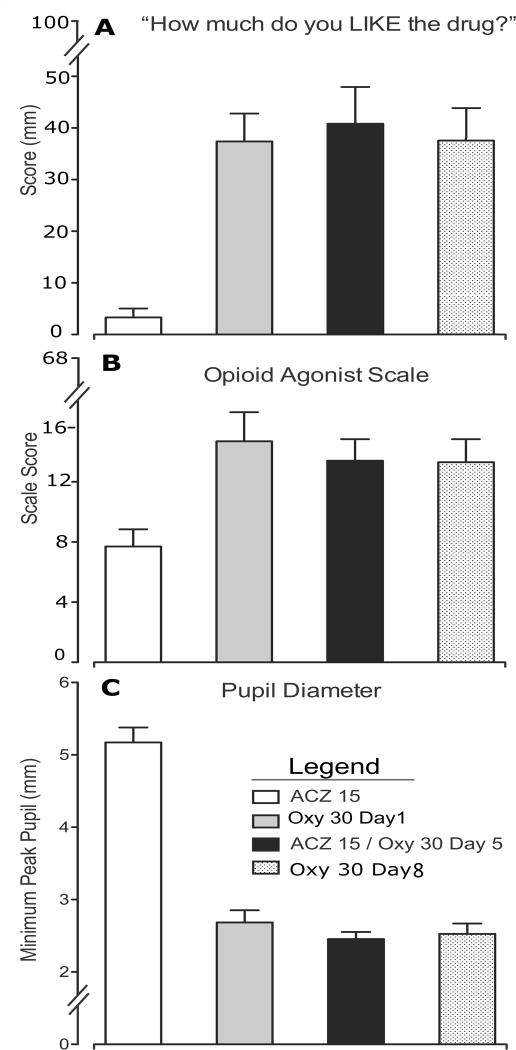

Oxycodone Pharmacodynamics and lack of Interaction with Acetazolamide

Oxycodone produced a range of physiological effects and changes in subject- and observer-rated measures consistent with its known mu opioid receptor agonist profile. For example oxycodone increased ratings on a visual analog scale of drug liking22, sustained pupil miosis and increased scores on an Opioid Agonist Checklist as rated by subjects and observers23 (Fig 5). The findings were time-dependent and consistent for the raw time course values, peak (Emax) values and AUC. No changes in oxycodone-induced drug liking, pupil miosis or ratings on the opioid-agonist scale were observed when oxycodone was administered in the presence or absence of ACZ (Day 5 compared with Days 1 and 8, Fig 5, p>0.05). Similarly, ACZ did not significantly (p>0.05) affect any of the broad array of pharmacodynamic measures examined following oxycodone administration (data not shown). No adverse effects or significant differences in respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation or blood pressure were observed. Very few side effects were reported over the course of the study (a total of 13 single daily symptom reports); of those specific to ACZ, one subject reported a metallic taste in the mouth on a single ACZ dosing day, and there were no reports of numbness or tingling sensations in hands, feet or mouth or ringing in the ears. All drug doses were generally well tolerated.

Figure 5. Pharmacodynamic responses to administration of Oxycodone (Oxy).

White column indicates acetazolamide (ACZ) alone, Black column indicates ACZ+Oxy, Grey Column indicates Oxy alone on Day 1 and hatched column indicates Oxy alone on Day 8

A) Subjective ratings of drug liking on 100mm visual analog scale

B) Mean scores of the Opioid Agonist Checklist as rated by both the subjects and observers

C) Pupil diameter in mm.

DISCUSSION

An adherence marker that can indicate the time of last consumption with a window of several days would be of significant value in clinical medication development trials, as daily sampling is often impractical. Most adherence measures do not confirm consumption, except for riboflavin, which provides a window of <24 h, is confounded by dietary sources and exhibits highly variable absorption and elimination7,9. Using existing data we identified two candidate compounds, quinine and ACZ, as potentially useful adherence markers to monitor QD and BID medication regimens (respectively). We therefore conducted clinical PK studies with a focus on the urinary elimination of sub-therapeutic doses of both compounds. However an interim analysis indicated that, unlike low-dose quinine15, the PK of micro-dose ACZ was different to that reported in previous therapeutic dose studies. The plasma t1/2 for microdose ACZ (Tables 1 & 2) was much longer than the 3–6 h reported for therapeutic doses14,18, and its elimination from plasma was unexpectedly biphasic. Previous PK studies have not reported the urinary elimination rate of ACZ, but because >90% of an ACZ dose is eliminated unchanged into urine14,18, the rate of appearance in urine was expected to be similar to the reported plasma elimination rate (3–6h). In fact, the observed urinary t1/2 of an ACZ microdose was 16 h (Fig 3, Table 3), suggesting that, while therapeutic doses are primarily contained within plasma, a large proportion of a microdose is stored outside the plasma and the urinary t1/2 is driven by slow release from this/these reservoir(s). Acetazolamide is a CA inhibitor and RBCs contain substantial quantities of CAs19,20, suggesting that RBCs may act as a long-lived ACZ depot. This hypothesis was examined in a subset of subjects by taking blood samples (in addition to plasma) and extending the sample collection period. Interpreting these results required detailed analysis and description of how RBCs can explain the differences between the PK of ACZ at therapeutic and micro doses. In order to present adequately focused papers, the quinine study was reported separately15.

Plasma / RBC pharmacokinetics

Table 1 and Fig. 1 examine whether oxycodone influences the plasma PK of ACZ. After controlling for residual ACZ from previous doses by subtraction prior to analysis, no influence of oxycodone was observed on the plasma PK of ACZ. A lack of such drug-drug interaction is a desirable feature for a medication marker.

Comparison of the relative PK of ACZ within plasma and RBC components of 1 mL of blood after dosing on Day 5 (Table 2 and Fig. 2) demonstrates that RBCs accumulate ACZ during the plasma alpha elimination phase, while the overall ACZ blood concentration remains relatively constant (compare Figs 2A (left x-axis) and 2B). This suggests the plasma αt1/2 is dominated by redistribution of ACZ from plasma to the RBC depot. In Fig 2 as with Fig 1, the residual ACZ was subtracted to better visualize the relative kinetics, although in both Fig 2 (and Table 2) the non-subtracted “RBC Total” data are included to illustrate the degree of RBC accumulation over four daily doses. The RBCtotal Cmax was 17±1.0 µM (Table 2 with hematocrit compensation), which means that for most of the exposure period, ACZ was likely sequestered by CAII, the high affinity RBC isoform that exhibits a maximum ACZ binding capacity at 17 µM19. In contrast, a study that administered a therapeutic dose of ~400 mg ACZ/day reported mean RBC and plasma concentrations of 121±46µM and 51±40µM21 (respectively), at which levels CAII would be saturated and the overall elimination rate would be dominated by glomerular filtration and the faster releasing-low affinity CAI RBC isoform (max binding capacity 155 µM19). It is these differences in binding capacity and affinities of the two RBC isoforms that explain why therapeutic ACZ doses produce reported t1/2’s of 3–6 h and yet the βt1/2 of a microdose is so much longer. The impact of RBC sequestration on overall plasma βt1/2 is also clearly visible in the current study by comparing the plasma βt1/2’s calculated from 24 h versus 96 h sampling periods (Table 1 vs Table 2). The βt1/2 calculated from the 96 h sampling period was longer than the 24-hour period (24.5 vs 13 h), because the relative contribution of slow release from RBCs is greater at lower plasma concentrations and more visible when viewed over an extended period.

Urinary excretion rate of Acetazolamide

The long plasma βt1/2 of ACZ results in a long urinary t1/2, which is an important feature of ACZ microdose PK that contributes to its value as an adherence marker. Microdose ACZ urinary elimination rates exhibited a t1/2 of 16 h and showed little intersubject/intersample variability (Fig. 3 and Table 3), presumably because ACZ is exclusively eliminated in urine as unchanged drug. After dosing cessation, the mean trough rates were significantly lower on each consecutive day (Fig 3, overall F(3,23)=247; p<0.05), and importantly, the subject with the slowest elimination rate at 48 h after dosing cessation, (i.e., the low outlier) was eliminating ACZ at a rate that was almost three times faster than the fastest rate (high outlier) 96 h after cessation (87 µg/h vs 33 µg/h). This suggests the ability to distinguish an individual who has skipped 1–2 doses from one who has skipped more than 3 doses. By comparison, when the current standard marker riboflavin is used, 25% of urine samples drop below detection cut-off limits within 12 h of missing a dose because of the physiological background level of riboflavin8.

If variability between urinary elimination rates is expressed as relative standard deviation around the mean (RSD), the RSD for ACZ at 24 h after dosing cessation was only 18%, while elimination rates in a similarly constructed study using riboflavin, exhibited an RSD of 77% at 24 h9. The remarkably low variability in the rate of ACZ elimination is further underscored by comparison of the ACZ RSD with the 52% RSD in quinine elimination rates observed 24 h after dosing cessation in the same subjects who participated in this ACZ protocol.

Low variability is an important feature for an adherence marker as it increases confidence in estimates of the time of last dosing calculated by back-extrapolation from an observed sample. While this was a small study, the low variability suggests an ACZ marker may permit assessment of the number of days elapsed since last dosing with a multi-day window. Furthermore, there is no physiological background level for ACZ, and so even when the exact time of dosing is less certain, any ACZ indicates that medication has been taken at least sometime recently, which cannot be said when riboflavin is used as a marker.

Interactions of ACZ with oxycodone

The role of an adherence marker is to be concomitantly administered with other medications; thus, this study concomitantly administered ACZ and oxycodone (used as a test medication) under conditions optimized to produce interactions. Oxycodone did not affect the PK of ACZ (Fig 1 Table 1) and pharmacodynamic responses to oxycodone were unaffected by ACZ (Table 4). The formation and elimination of oxycodone’s major metabolite (noroxycodone)16 was also unaffected by ACZ (Table 4) and the PK of oxycodone was probably unaffected by ACZ. Most of the oxycodone PK parameters were not altered by the presence of ACZ (p>0.05), except that the overall oxycodone AUC on Day 1 was 20% smaller than when administered with ACZ on Day 5 (p<0.05, Fig 5, Table 4). However, that difference was not reproduced when oxycodone was given alone again on Day 8, suggesting it may have been due to natural variation in a small sample size. It is unlikely that the oxycodone AUC on Day 8 was affected by residual ACZ, as the last ACZ microdose was given on Day 5 and any remaining ACZ was largely sequestered. By the time oxycodone was administered on Day 8, the mean ACZ plasma concentration was only 2.5% of its Cmax (32±6 ng/ml). Finally, the microdose used here was only 6% of the recommended initial therapeutic dosage, and ACZ has been widely used for more than 50 years without any published records of interactions between opioids and ACZ or other carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.

Acetazolamide-drug interactions

The probability of metabolic interactions with between an ACZ marker and coadministered medications is low since ACZ is excreted without metabolism14. The most commonly reported drug interactions are due to bicarbonaturia and hypokalemia10, which are direct effects of CA inhibition and unlikely to occur with subtherapeutic microdoses. One study that examined adverse effects with therapeutic (~400 mg / day) ACZ doses concluded that side effects correlate with RBC concentrations that exceed 90 µM21. In this study RBC concentrations were only 17 µM at Cmax, and so the absence of observed side-effects is not surprising. Aspirin at very high doses (3.5–5g /day) has been reported to reduce the clearance of therapeutic doses of ACZ by two fold, due to competition at renal transporters24. However, given that the rate of microdose elimination appears to be controlled by CA depot-release rather than renal transport rates, an ACZ marker would not be expected to be as greatly affected by high aspirin doses as with a therapeutic dose. However, renal transport interactions are worthy of note if considering ACZ as a marker for high–dose medications that are primarily / exclusively eliminated via renal transport.

Study caveats

In this small inpatient study of primarily Caucasian males, all output urine was collected allowing for the data to be presented in terms of rates of elimination (µg/h). This is not generally feasible for an outpatient clinical trial, where a subject would normally provide a discrete sample during a clinic visit, and the marker concentration would be normalized against urinary creatinine concentration to control for volume and time since last void. Creatinine was not measured in this study and introduction of an extra assay could increase inter-sample variance, although equally the mean RSD in urinary ACZ might be reduced in larger studies.

Summary

The significant role that RBC sequestration plays in extending the urinary t1/2, of ACZ microdoses was unexpected. This welcome surprise demonstrates that sub-therapeutic doses of ACZ can serve as an adherence marker for a QD medication regimen, one that shows substantially less variability than the current standard (riboflavin) and exhibits an “indicator period” of up to 4 days after last dose. It is hoped that that others may consider using ACZ as a tracer when developing a point-of-care assay, in order to generate a system capable of allowing adherence issues to be detected and addressed during (rather than after) a trial. This would not only improve the accuracy of adherence and adverse event frequency estimations, but also reduce the possibility of trial failure due to insufficient exposure to the test medication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the University of Kentucky (UK) Center on Drug and Alcohol Research for research support: the UK CCTS Laboratory for assistance with specimens; the UK Investigational Pharmacy for preparing study medication, UK CCTS Inpatient Unit nursing staff for patient care, and Dr. Samy-Claude Elayi (UK Department of Cardiology, Gill Heart Institute) for patient support. We also thank Dr. Nora Chiang at the National Institute on Drug Abuse for her pharmacokinetic expertise and support. Neither Dr Hampson nor Dr Krieter had Programmatic responsibility for R01DA016718-08S1 (SLW), the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant that supported the conduct of this work. We also acknowledge nursing and inpatient support from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, UL1TR000117.

Sources of Funding.

Dr Lofwall received a grant from Braeburn Pharmaceuticals and has received an honorarium from PCM Scientific. Dr Walsh has received an honorarium from Eli Lilly, salary support from PCM Scientific and consulted for Astra Zenica, Braeburn Pharmaceuticals, Camurus, Cerecor Inc, DemeRX, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Sun Pharma and World Meds. This study was supported by research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA016718-08S1 [SLW]) and the National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing of Translational Sciences (UL1TR000117-04 [UK CTSA]; KL2TR000116-04 [SB]).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest.

For the remaining authors, no conflicts were declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fossler MJ. Patient adherence: Clinical pharmacology’s embarrassing relative. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55:365–367. doi: 10.1002/jcph.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czobor P, Skolnick P. The Secrets of a Successful Clinical Trial: Compliance, Compliance, and Compliance. Mol Interven. 2011;11:107–110. doi: 10.1124/mi.11.2.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaschke TF, Osterberg L, Vrijens B, et al. Adherence to medications: insights arising from studies on the unreliable link between prescribed and actual drug dosing histories. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:275–301. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011711-113247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson AL, Li SH, Biswas K, et al. Modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McRae-Clark AL, Baker NL, Sonne SC, et al. Concordance of Direct and Indirect Measures of Medication Adherence in A Treatment Trial for Cannabis Dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;57:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granger BB, Swedberg K, Ekman I, et al. Adherence to candesartan and placebo and outcomes in chronic heart failure in the CHARM programme: double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2005;366:2005–2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zempleni J, Galloway JR, McCormick DB. Pharmacokinetics of orally and intravenously administered riboflavin in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:54–66. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herron AJ, Mariani JJ, Pavlicova M, et al. Assessment of riboflavin as a tracer substance: comparison of a qualitative to a quantitative method of riboflavin measurement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramanujam VM, Anderson KE, Grady JJ, et al. Riboflavin as an oral tracer for monitoring compliance in clinical research. Open Biomark J. 2011;2011:1–7. doi: 10.2174/1875318301104010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swenson ER. Safety of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:459–472. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.897328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumont L, Mardirosoff C, Tramer MR. Efficacy and harm of pharmacological prevention of acute mountain sickness: quantitative systematic review. Bmj. 2000;321:267–272. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly TE, Hackett PH. Acetazolamide and sulfonamide allergy: a not so simple story. High Alt Med Biol. 2010;11:319–323. doi: 10.1089/ham.2010.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knowles S, Shapiro L, Shear NH. Should celecoxib be contraindicated in patients who are allergic to sulfonamides? Revisiting the meaning of ‘sulfa’ allergy. Drug Saf. 2001;24:239–247. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granero GE, Longhi MR, Becker C, et al. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: acetazolamide. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:3691–3699. doi: 10.1002/jps.21282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babalonis S, Hampson AJ, Lofwall MR, et al. Quinine as a potential tracer for medication adherence: A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessment of quinine alone and in combination with oxycodone in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;55:1332–1343. doi: 10.1002/jcph.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalovic B, Kharasch E, Hoffer C, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral oxycodone in healthy human subjects: role of circulating active metabolites. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:461–479. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motulsky H, Christopoulos A. Fitting models to biological data using linear and nonlinear regression: a practical guide to curve fitting. Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritschel WA, Paulos C, Arancibia A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of acetazolamide in healthy volunteers after short- and long-term exposure to high altitude. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38:533–539. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb05791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bayne WF, Chu LC, Theeuwes F. Acetazolamide binding to two carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes in human erythrocytes. J Pharm Sci. 1979;68:912–913. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600680736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace SM, Reigelman S. Uptake of acetazolamide by human erythrocytes in vitro. J Pharm Sci. 1977;66:729–731. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600660532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inatani M, Yano I, Tanihara H, et al. Relationship between acetazolamide blood concentration and its side effects in glaucomatous patients. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1999;15:97–105. doi: 10.1089/jop.1999.15.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh SL, Nuzzo PA, Lofwall MR, et al. The relative abuse liability of oral oxycodone, hydrocodone and hydromorphone assessed in prescription opioid abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser HF, Van Horn GD, Martin WR, et al. Methods for evaluating addiction liability (A) “Attitude” of opiate addicts toward opiate-like drugs (B) a short-term “direct” addiction test. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961;133:371–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweeney KR, Chapron DJ, Antal EJ, et al. Differential effects of flurbiprofen and aspirin on acetazolamide disposition in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;27:866–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]