Abstract

Macrophages play vital functions in host inflammatory reaction, tissue repair, homeostasis and immunity. Dysfunctional macrophages have significant pathophysiological impacts on diseases such as cancer, inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease), metabolic diseases (atherosclerosis, diabetes and obesity) and major infections like human immunodeficiency virus. In view of this common etiology in these diseases, targeting the recruitment, activation and regulation of dysfunctional macrophages represents a promising therapeutic strategy. With the advancement of nanotechnology, development of nanomedicines to efficiently target dysfunctional macrophages can strengthen the effectiveness of therapeutics and improve clinical outcomes. This review discusses the specific roles of dysfunctional macrophages in various diseases and summarizes the latest advances in nanomedicine-based therapeutics and theranostics for treating diseases associated with dysfunctional macrophages.

Keywords: cell receptor, drug delivery, gene therapy, in vivo, macrophage phenotype, tissue macrophages

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

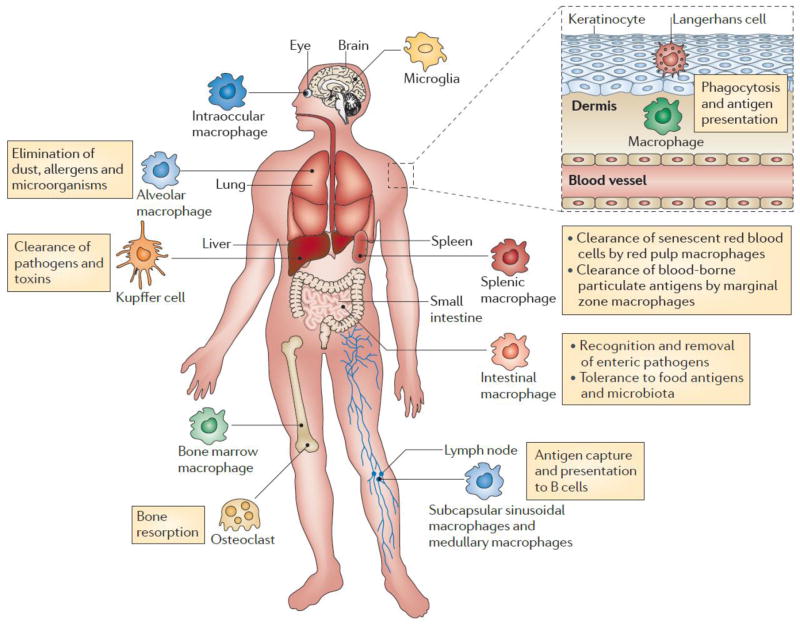

Macrophages originate from blood-derived monocytes. Granulocyte/monocyte precursor cells develop into monocytes upon endogenous stimuli such as macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-3 (IL-3). De novo monocytes leave the bone marrow, enter the bloodstream and approximately one day later migrate into the tissues throughout the body where they differentiate into tissue macrophages (also called resident macrophages). Tissue macrophages have different names based on locations such as kupffer cells in the liver, alveolar macrophages in lungs, red pulp macrophages in spleen, and sinus histiocytes in lymph nodes [1, 2]. Although tissue macrophages are anatomically distinct from one another and have diverse functional capabilities and transcriptional features, they are invariably essential in mediating inflammation, tissue repair, homeostasis and immunity (Fig. 1) [1, 3, 4].

Fig. 1.

Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Adapted with permission from [4].

In response to tissue damage as a result of infection or injury, blood monocytes are recruited from the circulation and differentiate into macrophages following migration into the affected tissues [3, 5]. Macrophages can recognize pathogen-associated molecules and apoptotic cell-associated endogenous ligands through receptor-mediated recognition patterns. These recognition events lead to pathogen clearance via phagocytosis and subsequent alleviation of infection. However, when macrophages are inappropriately activated, an uncontrolled inflammatory response is initiated, and their homeostatic and reparative functions are subverted, resulting in a causal association between macrophage infiltration and disease states [6, 7] such as growth and metastasis of malignant tumors [8–10], inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid arthritis [11–14] and inflammatory bowel disease [15, 16]), metabolic diseases (atherosclerosis [17–19], diabetes [20–22] and obesity [23, 24]), and severe infections like HIV [25, 26]. Based on their pathophysiological roles in diseases, targeting the recruitment, activation and regulation of dysfunctional macrophages represents a promising therapeutic strategy [5, 7, 27]. Many small molecule-based therapies have been developed to target dysfunctional macrophages and restore their protection functions. However, the lack of macrophage-targeting causes adverse side effects and poses restriction on their clinical application [27, 28]. The emergence and advancement of nanotechnology has given rise to targeted nanomedicines and opened up new opportunities for treating diseases associated with dysfunctional macrophages [27–31]. This review discusses how macrophages play roles in various pathophysiological diseases and then summarizes how nanomedicines are utilized to treat dysfunctional macrophage-associated diseases.

2. Nanomedicines and approaches for homing to macrophages

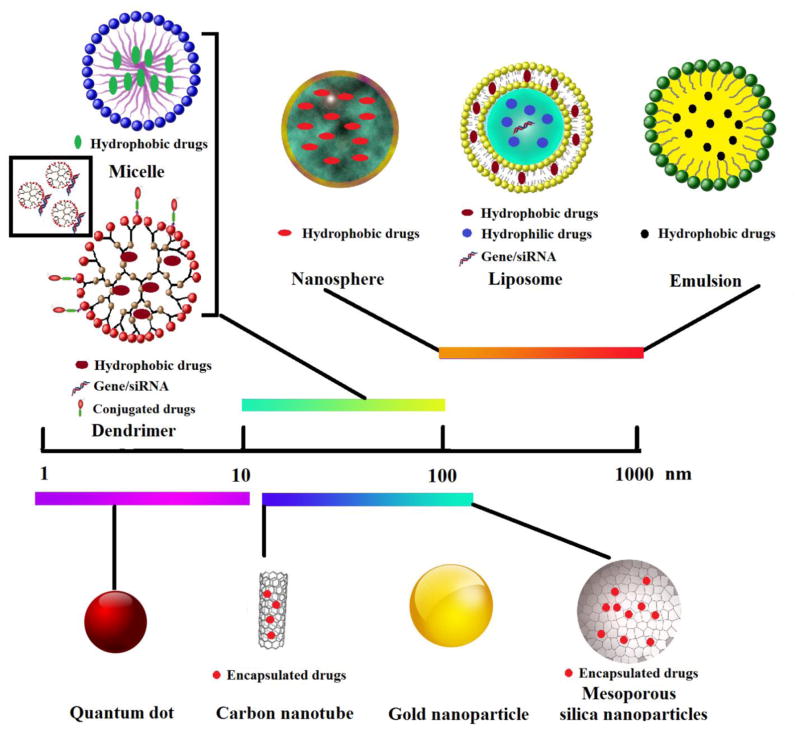

Nanomedicines, the application of nanotechnology to medicine, are anticipated to help solve a number of trepidations associated with conventional therapeutic agents such as poor water solubility, lack of targeting specificity, nonspecific distribution, systemic toxicity, and low therapeutic index [31–33]. Over the past several decades, remarkable progress has been made in the development and application of engineered nanoparticles to treat various diseases [34]. The most engineered nanoparticles include polymeric nanospheres, lipid carriers (liposomes and emulsions), polymeric micelles, dendrimers and inorganic nanoparticles (e.g., mesoporous silica nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, quantum dots and carbon nanotubes) (Fig. 2) [35–37]. The different types of nanoparticles with focus on material compositions, cargo attachment, and advantages and disadvantages are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Graphical illustration of different types of nanoparticles.

Table 1.

Summary of different types of engineered nanoparticles

| Types | Size (nm) | Compositions | Cargo loading manner | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanospheres | 10–1000 | Solid hydrophobic nanoparticles based on polymer matrix | Embedded in the polymeric matrix | High loading capacity and controllable release based on the nature of polymeric matrix | Poor colloidal stability | [38, 39] |

| Liposomes | 100–1000 | Bilayer of phospholipids | Encapsulated within the hydrophilic core and hydrophobic bilayer | Easy fabrication, better biocompatible and suitable for both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drug loading | Poor colloidal stability | [40–42] |

| Emulsions | 100–1000 | Amphipathic surfactant embedding inner hydrophobic core | Encapsulated within the hydrophobic core | Highly hydrophobic drug loading | Poor colloidal stability | [43, 44] |

| Micelles | 10–100 | A core and shell structure assembled by amphipathic polymer | Encapsulated within the inner hydrophobic core | Small size, high loading capacity, prolonged circulation | Low structural stability below critical micelle concentration and poor release profiles | [45, 46] |

| Dendrimers | 10–100 | Highly branched, star- shaped macromolecules with nano-sized dimensions | Embedded inside the branches, conjugated to the surface, or electronically complexed with gene/siRNA | Highly water soluble and functionalized surface groups. | Highly positive surface charge-related toxicity | [47–49] |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles | 20–200 | Nano-sized mesoporous silica sphere | Encapsulated within the inner pores by hydrophobic interaction | High loading capacity, and homogenous distribution for guest molecules into porous | Low drug release; lack of in vivo studies on PK/PD, bio-distribution and clearance | [50, 51] |

| Gold nanoparticles | 2–100 | Solid gold particles within nanometer | conjugated or coated on the surface | Durable photothermal properties | Difficult to load drug and poor biocompatibility- induced toxicity. | [52–54] |

| Quantum dots | 2–10 | Fluorescent semiconductor nanoparticles | conjugated or coated on the surface | Versatile surface chemistry and high photostability | Surface defects and toxicity issues | [55, 56] |

| Carbon nanotubes | 1–5 diameter 1–150 length |

Tube-shaped nanomaterials made of carbon | Attachment on the surface or within the interior core of carbon tube | Facilitated intracellular drug delivery by tube-shaped structure and high aspect ratios and surface areas allowing for high drug loading | Expensive production, poor biodegradability and organ accumulation toxicity | [57, 58] |

In comparison to traditional formulations, nanoparticle-based nanomedicines offer many distinctive characteristics such as: 1) improved bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs; 2) extended blood half-life through better protection before reaching the targets; 3) controlled drug release; 4) co-delivery of multiple types of therapeutic drugs and/or diagnostic agents (for instance, contrast/imaging agents) for combination therapy, real-time readout of therapeutic outcomes, or theranostics; and 5) targeted drug delivery to improve drug efficacy and reduce systemic side effects [32, 35]. These advantages have already been realized in those nanomedicines available on market or in clinic trials [34, 36, 59, 60]. Some of the properties have been integrated into therapeutic strategies to tackle diseases arising from dysfunctional macrophages.

To enhance the specificity of nanomedicines to dysfunctional macrophages, active targeting approaches can be employed by functionalizing nanoparticles with moieties (such as antibodies, peptide, etc.) that have high affinity for the receptors on the surface of macrophages [28, 31, 61–64]. Table 2 describes some receptors that are overexpressed on the surface of macrophages and their utility for achieving active targeting of macrophages. The commonly studied macrophage surface receptors include mannose receptor, scavenger receptors, dectin-1 receptor, tuftsin peptide, cluster of differentiation (CD) 44 receptor, folate receptor beta (FR-β) and phosphatidylserine receptor.

Table 2.

Examples of receptors targeting macrophages

| Macrophage-targeted receptors | Brief description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Mannose receptor | CD206; A C-type lectin primarily present on the surface of macrophages can recognize mannose terminal, N-acetylglucosamine and fucose residues molecules with high affinity. | [65–68] |

| Scavenger receptor | A group of receptors (categorized into classes A, B, and C) that highly recognize modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL) such as scavenger receptor (SR) B1 (SR- B1), SR-A and CD36. | [69–73] |

| Dectin-1 receptor | A non-opsonic b-glucan receptor, overexpressed in macrophages, is essential for the phagocytosis of yeast by macrophages. | [74–76] |

| Tuftsin peptide | Tetra-peptide sequence Thr-Lys-Pro-Arg; Activates macrophages and enhances their phagocytic ability. | [77–79] |

| CD44 receptor | Cell-surface glycoprotein involved in cell interactions, adhesion and migration; Distinctive receptor for hyaluronic acid and can also interact with other ligands, such as osteopontin, collagens, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). | [80–82] |

| FR-β | FR-b is specifically expressed by activated macrophages and shows a high affinity for folic acid (FA). | [83–86] |

| Phosphatidylserine receptor | Responsible for clearance of apoptotic cells overexpressing phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of plasma membrane. | [87, 88] |

3. Nanomedicines targeting dysfunctional macrophage-associated diseases

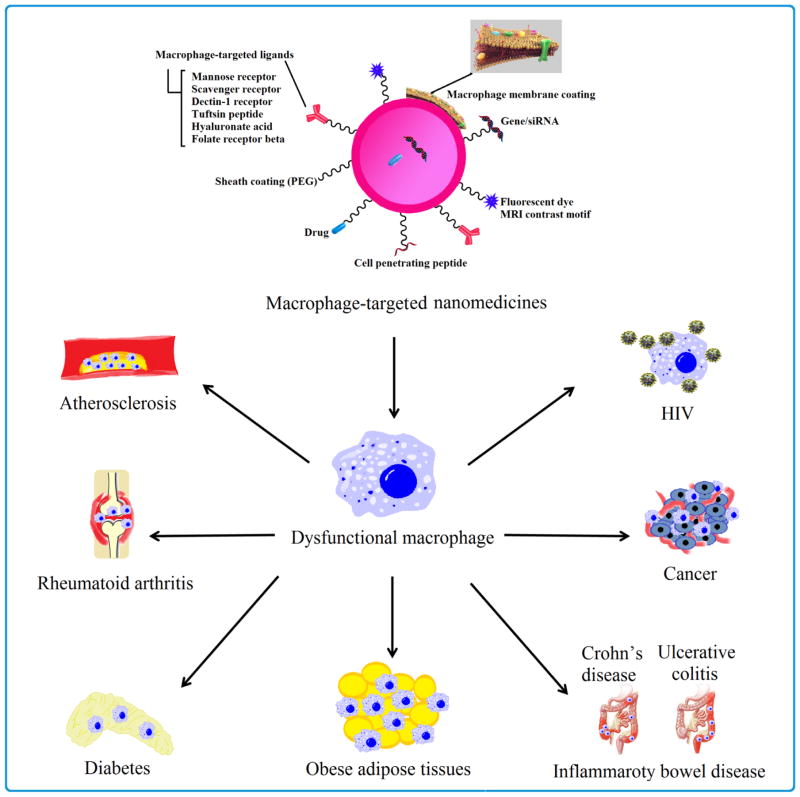

Dysfunctional macrophages have common pathological features and critical implications in the pathogenesis of various diseases, hence representing a potential target for the prevention as well as treatment of these diseases. We highlight the characteristics and potential therapeutic strategies of dysfunctional macrophage-associated diseases (Fig.3 and Table 3) along with selected examples from recently reported nanomedicine-based therapies [3, 5, 7].

Fig. 3.

Multifunctional nanomedicines targeting dysfunctional macrophage-associated diseases.

Table 3.

Overview of major dysfunctional macrophage-associated diseases and selected nanomedicines

| Disease types | Involvement of dysfunctional macrophages | Potential therapeutic strategies for dysfunctional macrophages | Selected nanomedicines based on dysfunctional macrophages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Macrophages within the tumor microenvironment, termed as tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), facilitate angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling and promote tumor cell growth and metastasis. | Inhibiting macrophages recruitment and activation; Suppressing TAMs survival; Enhancing M1-like tumoricidal activity of TAMs and blocking M2- like tumor-promoting activity of TAMs. | [89–93] |

| Atherosclerosis | Under stimulus from oxLDL, the recruited monocyte differentiates into macrophages that overexpress scavenger receptors, which internalize excessive oxLDL in an unregulated manner, thus propagating the inflammatory cascade and leading to neo-intimal plaques | Alleviate the inflammation in intima to stop the monocyte recruitment; Inhibit lipid accumulation in macrophage to stop the foam cell formation; Enhance the removal of cholesterol ester from the existing plaque. | [94–98] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | The abundance and activation of macrophages in the inflamed synovial membrane/pannus lead to inflammation and ensuing osteoclasts. | Reduce the numbers of activated macrophages to inhibit activation signals and/or their specific products that amplify the disease. | [99–102] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | A change in flora or a defect in microbial clearing processes can lead to uncontrolled microbial growth in the lamina propria, thus stimulating recruitment and activation of inflammatory macrophages | Use of receptor agonists or antagonists that stimulate intestinal immune responses to achieve the required response, thus inhibiting the recruitment of macrophage from blood. | [103–106] |

| Obesity | Adipose tissue is intimately characterized by infiltration of large number of pro- inflammatory macrophages ( termed as adipose tissue macrophages, ATMs) | Anti-inflammatory treatments; Transition in macrophage polarization from M1-like state back to M2-like state | [107–109] |

| Diabetes | Pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by M1-like macrophages abundant in adipose tissue inhibit insulin receptor signaling and lead to insulin resistance. | Anti-inflammatory treatments; Transition in macrophage polarization from M1-like state back to M2-like state | [110–112] |

| HIV | Macrophages not only act as the HIV antigen presenting cells and also disseminate HIV-1 virus throughout the body | Targeting HIV-1 reservoir in macrophages; Sensitive the antigen presenting capacity for macrophage; | [113–116] |

3.1. Dysfunctional macrophages in cancer

3.1.1. Involvement of tumor-associated macrophages in cancer development

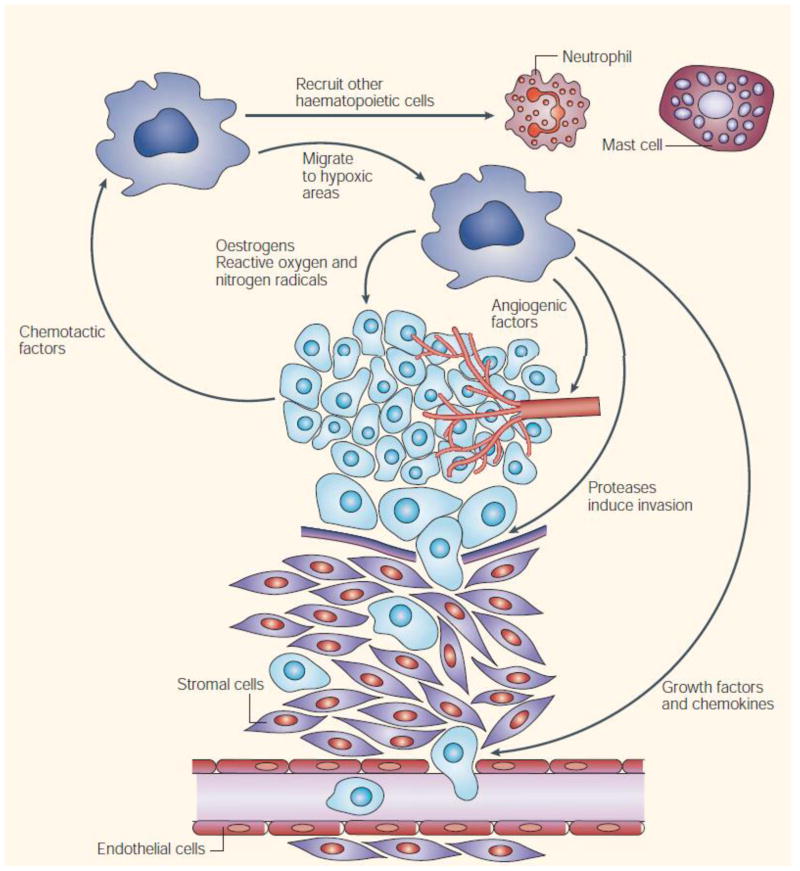

Accumulating evidence from clinical and experimental studies indicates that macrophages in tumor tissues, namely tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), have important roles in progression and metastasis of solid tumors [117–119]. TAMs are the main population of inflammatory cells in solid tumors and play diverse roles in tumor advancement. Studies have revealed that the majority of TAMs are activated M2-like macrophages with anti-inflammatory properties. The activated macrophages produce many trophic functions. They produce tumor-promoting cytokines and growth factors such as endothelial growth factor, angiopoietin, matrix metalloproteinase 9 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and facilitate tumor promotion, angiogenesis, progression and metastasis, matrix remodeling and immune evasion (Fig. 4). Furthermore, TAMs contribute to drug-resistance. The consistently elevated number of TAMs is correlated to poor prognosis and therapeutic failure in cancer treatment [91, 120]. Therefore, TAM-targeting strategies such as depletion of TAMs or conversion of tumor-promoting M2 subtype to tumor-suppressing M1 subtype are expected to generate anti-cancer effects.

Fig. 4.

Pro-tumorigenic functions of tumor-associated macrophages. Adapted with permission from [120].

3.1.2. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) as a therapeutic target for cancer treatment

Recently, TAMs-targeting strategies have achieved significant progress, and the results are very encouraging. Based on the proposed involvement of TAMs in tumors, these strategies are classified into four categories: (1) inhibiting the recruitment and activation of monocyte-derived macrophage [121]; (2) repressing survival of TAMs [122]; (3) enhancing the anti-tumor activity of M1-like TAMs [74]; (4) suppressing the tumor-promoting activity of M2-like TAMs [123–125].

Although the success of clinical application of molecular-based TAM targeting approach is still being evaluated, a number of experimental studies have reported the utility of this approach for tumor suppression with positive therapeutic outcomes, which addresses the promise of further clinical trials. Several excellent reviews [117, 118, 123–126] have been written describing targeting of tumor-associated macrophages in cancer therapy. Nonetheless, few were focused on nanomedicine-based strategies. So herein we aimed to fill the gap by reviewing the literature with a particular emphasis on the recent developments and applications of TAMs-targeting nanomedicines for cancer therapy.

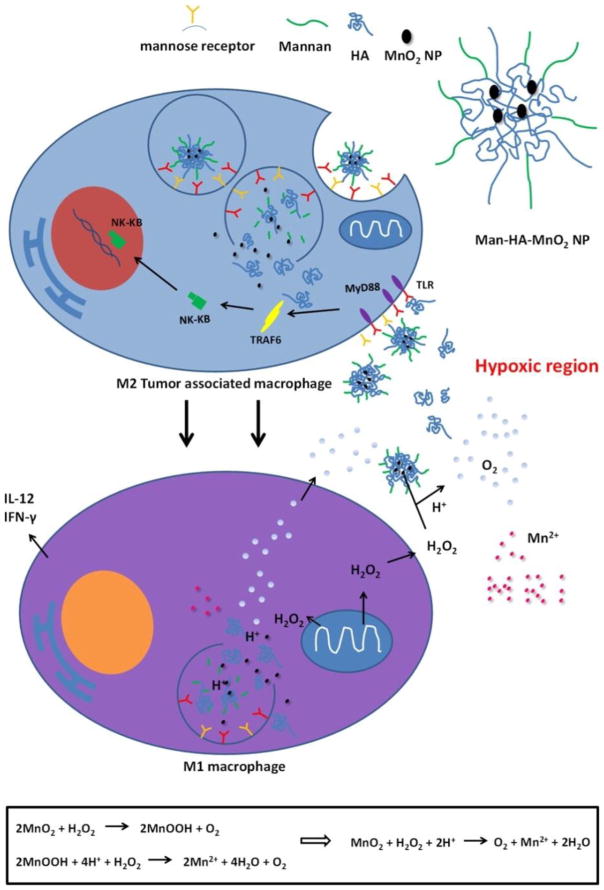

Unlike tumor-promoting M2-like macrophage, pro-inflammatory M1-like macrophages in the tumor exert anti-proliferative and cytotoxic activities against the progression of tumor by virtue of the ability to secrete oxygen species, reactive nitrogen (such as hydrogen peroxide, NO, peroxynitrite, and superoxide), and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin-1 (IL-1), and (interleukin-1) IL-6 [127–129]. Therefore, reprogramming TAMs from M2-like subtype to M1-like subtype may be a compelling strategy for anticancer therapy. Song et al. developed mannan-conjugated MnO2 particles with hyaluronic acid (HA) modification (Man-HA-MnO2 NPs). In this formulation, mannan was used for macrophage targeting, and MnO2 was used to alleviate tumor hypoxia. HA was incorporated into the delivery system to reprogram M2-like TAMs into M1-like subtype. Collectively these modifications helped reduce chemoresistance (Fig 5). The delivery of doxorubicin by Man-HA-MnO2 NPs generated synergistic effects on tumor growth inhibition [130].

Fig. 5.

Multifunctionality of Man-HA-MnO2 NPs: MnO2 particles (~15 nm) are entrapped in hyaluronic acid with mannan molecules attached. When Man-HA-MnO2 NPs are recognized and uptaken by mannose receptor of TAMs, hyaluronic acid reprograms anti-inflammatory, pro-tumoral M2 TAMs to pro-inflammatory, antitumor M1 macrophages, which might be via a TLR2-MyD88-IRAK1-TRAF6-PKCζ-NK-κB-dependent pathway. The reprogrammed M1 macrophages secrete high level of IL-12, IFN-γ and H2O2. The high reactivity of MnO2 NPs toward H2O2 allows for the simultaneous production of O2 and Mn2+ ions and regulation of pH of tumor hypoxia. Once MnO2 NPs are reduced into Mn2+ ions, they exhibit strong enhancement in both T1- and T2-weighted MRI. Adapted with permission from [130].

To actively target TAMs with anticancer agents and reduce non-specific drug uptake by normal organs, Zhu et al. developed a polyethylene glycol (PEG)-sheddable and mannose-modified nanoparticle delivery system. The nanoparticles liberated the PEG layer in the acidic tumor microenvironment and became more readily internalized by TAMs via mannose receptor-mediated endocytosis. The animal studies demonstrated higher tumor accumulation of this modified nanoparticle but reduced accumulation in normal tissues [131]. Recently, the same group applied the combination of mannose modification and acid-sensitive sheddable PEGylation to deliver doxorubicin to TAMs in triple-negative breast cancer. They reported that a single intravenous injection of such functionalized nanoparticles significantly reduced macrophage population in tumors within 2 days, and the repeated injections kept the macrophage population at a lower level for 9 days [132].

Therapeutic macromolecules (such as peptides and genes) are being actively developed as alternative to traditional chemotherapeutic drugs, which show widely observed serious side effects and poor patient compliance [133–135]. Yu et al. designed pH-responsive polymeric micelles that were mannosylated using “click” chemistry to achieve CD206 (mannose receptor)-targeted delivery siRNA to TAMs. They found that the mannosylated nanoparticles improved the delivery of siRNA into primary macrophages by 4-fold compared to the delivery by a non-targeted carrier. At 24 h post-treatment, 87 ± 10% knockdown of a model gene was observed in primary macrophages, demonstrating the site specificity of these polymeric micelles to TAMs [105]. Cieslewicz et al. designed a novel peptide, namely M2pep. It binds preferentially to M2-like macrophages as opposed to M1-like macrophages. They used M2pep to carry a pro-apoptotic peptide to TAMs and demonstrated that the selective reduction of M2-like TAMs improved survival of tumor-bearing mice [90]. The latest encouraging results underscore the importance of the M2-targeted therapeutic strategy.

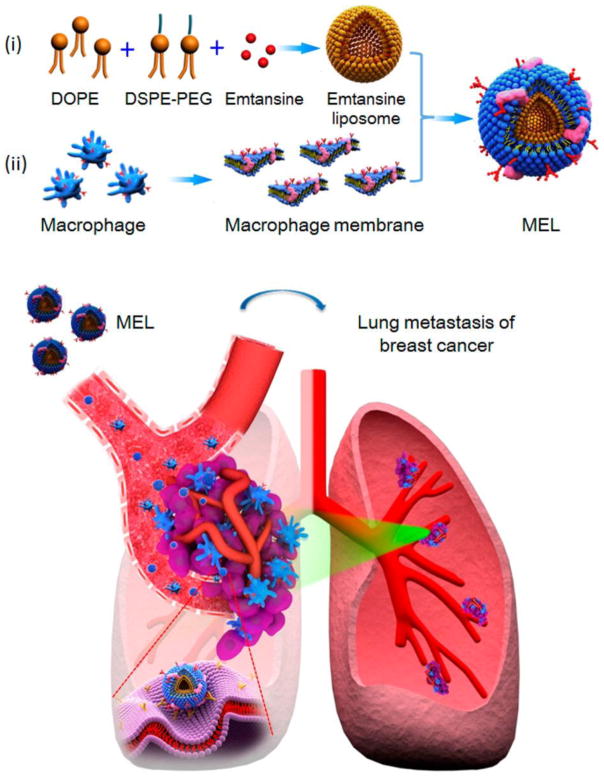

3.1.3. Macrophage membrane-camouflaged nanomedicines for cancer treatment

Bio-mimetic strategies engineer nanoparticles to mimic cellular functions. They have recently attracted due attention for drug delivery application. Because of the innate tumor homing ability, macrophages can be employed as a ‘Trojan horse’ to camouflage nanoparticles and then specifically guide nanoparticles to the tumor [136–139]. Cao et al. developed macrophage membrane-decorated liposomes, which showed improved tumor-metastasis targeting capability (though α4 integrin-VCAM-1 interactions between macrophages and metastatic cancer cells) and suppressed lung metastasis of breast cancer (Fig. 6). In particular, they isolated macrophage membranes from murine monocyte/macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 cells with high expression of α4 and used them to coat emtansine-encapsulating liposomes. This macrophage membrane decoration strategy increased the cellular uptake of the liposomes by metastatic 4T1 breast cancer cells and significantly inhibited cell viability. Appreciable inhibition of lung metastasis of breast cancer by macrophage membrane-coated emtansine liposomes was observed in vivo [89].

Fig. 6.

Scheme of macrophage-membrane-coated emtansine liposome with specific metastasis targeting for suppressing lung metastasis of breast cancer. Macrophage-membrane-coated emtansine liposome was fabricated by coating an emtansine liposome with an isolated macrophage membrane to confer the biomimetic functions of the macrophage, thereby facilitating the specific targeting to metastatic sites and enhancing the therapeutic efficacy on cancer metastasis. Adapted with permission from [89].

Xuan et al. used macrophage cell membrane (MPCM) to decorate gold nanoshells (AuNS). The resulting MPCM-coated AuNS maintained colloidal stability and near-infrared adsorption ability. Because of high density coverage of MPCM on AuNS, the function of macrophage cell membrane was nearly completely recovered, thus conferring active targeting ability upon the gold nanoparticles. The MPCM-coated AuNS had longer in vivo circulation time and were able to recognize tumor endothelium and accumulated in tumor in significant amounts. The MPCM-coated AuNS were applied for photothermal cancer therapy. Upon laser irradiation, local heat generated by the MPCM-coated AuNS achieved sufficiently high efficiency to suppress tumor growth and selectively ablated cancerous cells [140].

The aforementioned strategies are based on physical interactions between macrophage membrane fragments and an inner nanostructured core. The likely exchange of the coated macrophage membrane components with components of blood in circulation may lead to unexpected shedding of the macrophage membrane and consequent off-target effects. Therefore, developing strategies to obtain a stable macrophage membrane-derived coating warrants more efforts. Our lab exploited methods to hybridize macrophages and nanoparticles [141, 142]. One method was based on bioorthogonal chemistry. Following culture with azido sugar, RAW 264.7 macrophages expressed azides on the cell surface and were hybridized with polyamidoamine dendrimer G4.0 functionalized with dibenzocyclooctyne alkyne via bioorthogonal chemistry. Efficient selective cell surface modification by dendrimers was confirmed by confocal microscopy. The viability and motility of RAW 264.7 hybrids remained the same as untreated RAW cells as assessed by a series of bioassays. With the demonstration of the feasibility of applying bioorthogonal chemistry to create cell membrane-nanoparticle hybrids, this work provided a new approach for nanoparticle surface engineering on a cell membrane [141]. In addition to recent advances on TAMs-targeted nanomedicines, novel immunotherapy-based TAMs depletion strategies have been investigated. Some of them have already entered the clinics. We are optimistic that such additional supporting evidence provides a new driving force for innovative developments of TAMs-targeted nanomedicines in the future [118, 124, 125, 143].

3.2. Dysfunctional macrophages in atherosclerosis

3.2.1. Involvement of macrophages in the development of atherosclerosis

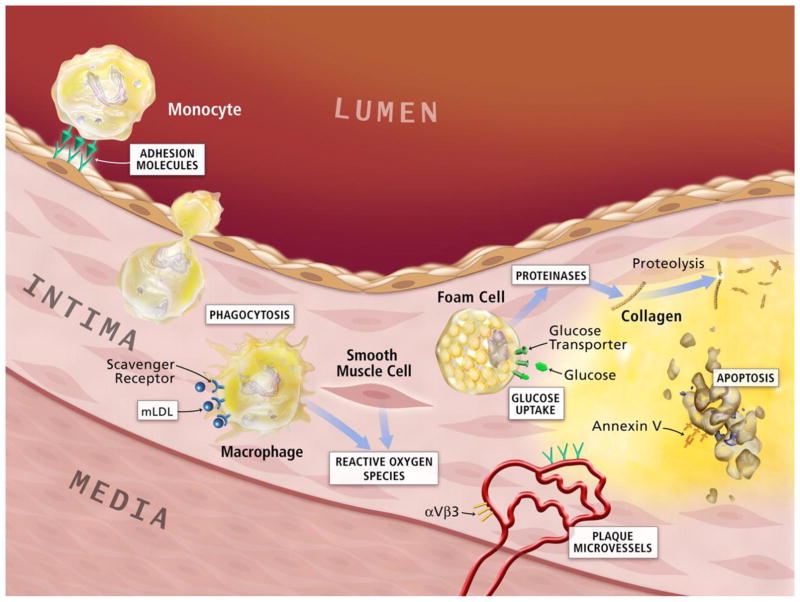

Macrophages have functions in various stages of atherosclerosis from development of fatty streak to eventual plaque rupture [144, 145]. Both the leakiness of endothelial cell junctions in areas of low shear stress and injury of endothelial cell junctions in areas of high shear stress permit excessive blood-derived LDL to enter the intima, where it is oxidized to become oxidized LDL (oxLDL). oxLDL initiates inflammation and upregulates adhesion molecules such as P-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) to recruit leukocytes such as monocytes. Recruited monocytes adhere to the leukocyte adhesion molecules expressed on the activated endothelial layer and migrate into the tunica intima, innermost layer of the arterial wall. Within the arterial intima, monocytes undergo a series of morphological changes and ultimately transform into macrophages that overexpress scavenger receptors such as the SR-A and CD36. Via unregulated uptake of oxLDL through receptors, the intimal macrophages transform into foam cells within the necrotic core. This constitutes the early atherosclerotic lesion and triggers the inflammatory cascade (Fig. 7) [146]. Several animal studies have demonstrated that macrophage depletion results in resistance to the development of atherosclerosis. Therefore, macrophages have already become a promising target for new therapeutic interventions against atherosclerosis [19, 147, 148].

Fig. 7.

Potential molecular imaging targets in atherosclerosis. White boxes show putative targets for molecular imaging of atherosclerosis. Atherogenesis involves recruitment of inflammatory cells from blood, represented by the monocyte in the upper-left-hand corner of this diagram. Monocytes are the most numerous leukocytes in atherosclerotic plaque. Recruitment depends on expression of adhesion molecules on macrovascular endothelium, as shown, and on plaque microvessels. Once resident in the arterial intima, activated macrophages become phagocytically active, a process that provides another potential target for plaque imaging. Oxidatively modified low-density lipoprotein–associated epitopes that accumulate in plaques may also serve as targets for molecular imaging. Foam cells may exhibit increased metabolic activity, augmenting their uptake of glucose, a process already measurable in the clinic by 18F-FDG uptake. Activated phagocytes can also elaborate protein-degrading enzymes that can catabolize collagen in the plaque's fibrous cap, weakening it, and rendering it susceptible to rupture and hence thrombosis. Mononuclear phagocytes dying by apoptosis in plaques display augmented levels of phosphatidylserine on their surface. Probes for apoptosis such as annexin V may also visualize complicated atheromata. Microvessels themselves can express not only leukocyte adhesion molecules (shown in green) but also integrins such as αVβ3. Proof-of-principle experiments in animals support each process or molecule in white boxes as target for molecular imaging agents. Adapted with permission from [146].

3.2.2. Dysfunctional macrophages as a therapeutic target for atherosclerosis treatment

Based on the vital roles of macrophages during progression of atherosclerosis, the following aspects may be considered as potential therapeutic targets to modulate function of macrophages [18, 149–152] to prevent atherosclerosis development: 1) inhibition of leukocyte adhesion [96, 153]; 2) inhibition of LDL oxidation to retard macrophage activation, for instance, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors to increase the resistance of circulating LDL to oxidation and reduce the development of atherosclerosis in ApoE−− mice independently out of their blood pressure-lowering effects [154, 155]; 3) suppression of macrophage scavenger receptor activities to reduce the uptake of oxLDL, thus preventing foam cell formation [97, 156], and 4) regulation of cholesterol homeostasis in macrophages, for example, reduction of cholesterol ester accumulation and enhancement of cholesterol ester efflux from macrophage within plaques [157, 158].

Many reports have indicated that modulating the polarity of macrophages from pro-inflammatory (M1-like) to anti-inflammatory (M2-like) may potentially prevent plaque destabilization and rupture [98, 147, 159, 160]. Nakashiro et al. prepared biodegradable poly (lactic-co-glycolic-acid) nanoparticles (NPs) and showed that following intravenous administration, these NPs accumulated in circulating monocytes and aortic macrophages. Additionally, weekly intravenous administration of pioglitazone-NPs for 4 weeks significantly decreased buried fibrous caps, a surrogate marker of plaque rupture, in the brachiocephalic arteries of ApoE−− atherosclerotic mice. This outcome was achieved by suppressing the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes and activating the production of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages within plaques [96].

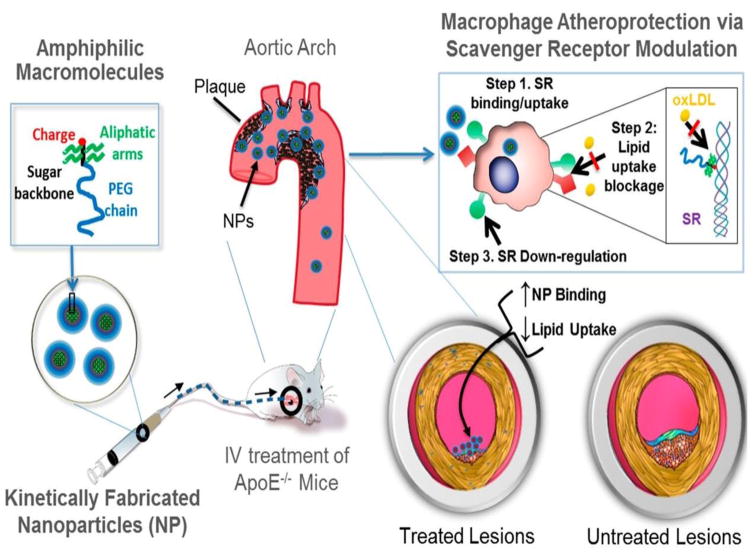

To suppress the uptake of oxLDL by macrophages and to further inhibit foam cell formation, Dr. Moghe’s laboratory designed a library of sugar-based amphiphilic core-shell layered nanoparticles (AM NPs). Due to their high binding to SR-A and CD36 on macrophages, AM NPs reduced oxLDL uptake and prevented foam cell formation (Fig. 8). Following intravenous administration, AM NPs accumulated in atherosclerotic lesions, resulting in significant reduction in neointimal hyperplasia, lipid burden, cholesterol cleft formation and overall vessel occlusion. Thus, synthetic macromolecules constructed as NPs not only effectively accumulate in lipid-rich lesions but can also be employed to counteract athero-inflammatory vascular diseases, exemplifying the promise of nanomedicines for hyperlipidemia and metabolic syndromes [97]. Zhang et al. used 1-(palmitoyl)-2-(5-keto-6-octene-dioyl) phosphatidylcholine as a CD36 ligand to improve the macrophage targeting property and antiatherogenic bioactivities of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) containing nanoparticles. This formulation delivered more EGCG to the cytosol and decreased cholesterol accumulation and inflammatory responses in macrophages, thus leading to attenuation of atherosclerosis [161]. To more effectively treat atherosclerosis, combination of certain therapeutic targets has been attempted to have additive/synergistic action, for instance, combination of reducing lipid accumulation and simultaneously minimizing inflammation. Moghe and coworkers incorporated antioxidant α-tocopherol into the nanoparticle core of sugar-derived amphiphilic polymers to suppress activity of scavenger receptor for reducing oxLDL uptake. These composite nanoparticles inhibited characteristic symptoms of atherosclerosis (modified lipid uptake and formation of foam cells), while minimizing inflammation in an ex vivo carotid plaque model [162].

Fig. 8.

The envisioned paradigm to counteract atherosclerotic plaque development aims to repress lipid-scavenging receptors at the level of lesion-based macrophages. Sugar-based AMs were designed to competitively block oxLDL uptake via binding and regulation of SRs on human macrophages. A library of AMs, with systematic variations in charge, stereochemistry, and sugar backbones, was synthesized and kinetically fabricated into serum-stable, core/shell NPs and screened in vitro to identify shell architectures that exhibited maximal atheroprotective potency. To demonstrate lesion level intervention, the lead NP was administered in an atherosclerosis animal model to challenge lesion development during coronary artery disease. Adapted with permission from [97].

Accumulation of cholesteryl ester (CE) rich macrophage foam cells in the artery wall is the hallmark of atherosclerosis. Although significant advances have been made to reduce circulating cholesterol levels by inhibiting de novo synthesis (by statins) or reducing cholesterol absorption (by Ezetimibe), therapy for plaque regression via enhanced removal of CE from existing atherosclerotic plaques is unavailable [163, 164]. The burden of existing plaques on the arteries still remains. For effective regression of existing plaques, targeted enhancement of CE mobilization represents a novel solution. CE hydrolysis by neutral cholesteryl ester hydrolase (CEH) is the obligatory first step in macrophage CE mobilization. This rate-limiting step regulates reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) and is most critically influential in eventual cholesterol clearance from the body [157]. Hence, our lab developed mannose-functionalized dendrimer nanoparticles (DNP) for the targeted delivery of liver X receptor (LXR) ligand (TO901317) [165]. LXR activation not only increases the expression of macrophage cholesterol transporters, namely ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) and ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1), but also increases CEH expression. Therefore, delivery of LXR ligand (TO901317) to plaque-associated macrophages will promote intracellular CE hydrolysis and facilitate the efflux of FC through ABCA1 and ABCG1, leading to plaque regression. Our results showed that intravenously administered mannose functionalized DNP specifically delivered LXR ligand to plaque-associated macrophages and reduced atherosclerosis.

3.2.3. HDL as a drug carrier to target dysfunctional macrophages in atherosclerosis

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory and capable of enhancing reverse cholesterol transport. HDL can be used as building blocks to construct cardiovascular drug carriers to exert additive/synergistic atheroprotective activities. The inherent macrophage-targeting property of HDL has been broadly utilized in atherosclerosis therapy [166–169]. Tang et al. discovered that either inhibition of macrophage proliferation or selective depletion of macrophages reduced plaque inflammation and produced long-term therapeutic benefits. Four-fold higher accumulation of statin-loaded HDL nanoparticles was seen in the aortic arch of atherosclerotic ApoE−− mice compared to healthy mice. As a result of reduced macrophage accumulation, inflammation in atherosclerosis was effectively attenuated. She et al. developed a cyclic peptide, LyP-1 (CGNKRTRGC), which specifically targets atherosclerotic plaques, penetrates into plaque interior, and accumulates in plaque macrophages. Systemic treatment with LyP-1 triggered apoptosis of plaque macrophages and reduced progression of plaques in ApoE−/− mice. These data suggest that peptide LyP-1 can serve as a targeting ligand for development of new nanomedicines targeting macrophages within atherosclerotic plaques [98].

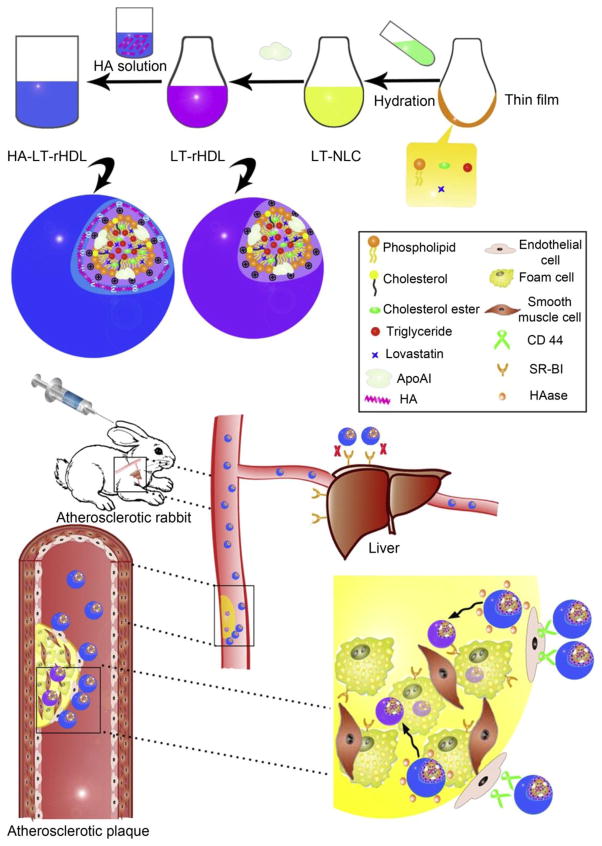

Duivenvoorden et al. developed reconstituted HDL (rHDL) nanoparticles to deliver statins to atherosclerotic plaques. rHDL labeled with Cy5.5 (lipid monolayer) and DiR (hydrophobic core) was intravenously injected into ApoE−/− mice. NIRF shows that Cy5.5 and DiR preferentially accumulated in areas rich in atherosclerotic lesions. While treatment with low-dose statin-rHDL for 3 months inhibited plaque inflammation, one-week regimen of high-dose markedly decreased inflammation in advanced atherosclerotic plaques [154]. Zhang et al. constructed recombinant HDL loaded with cardiovascular drug tanshinone IIA and demonstrated that tanshinone IIA-encapsulating rHDL accumulated in atherosclerotic plaques and showed stronger potency in reducing advancement of atherosclerosis [170]. HDL receptor SR-B1 is overexpressed not only in the atherosclerotic lesion's macrophages but in hepatocytes, inevitably resulting in the liver uptake of rHDL [167]. To reduce liver uptake, Liu et al decorated rHDL with macrophage-targeted moiety HA. This method proved to be effective in reducing uptake of rHDL by liver and directing more drugs to atherosclerotic lesions (Fig. 9). The quantitative assessment on atherosclerotic lesion size, intima-media thickness, macrophage infiltration and expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 confirmed that lovastatin (LT) delivered by HA-modified rHDL exhibited superior efficacy to other LT formulations [171].

Fig. 9.

Schematic diagram on preparation methods and atherosclerotic lesion targeting property of HA-LT-rHDL. Adapted with permission from [171].

3.3. Dysfunctional macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

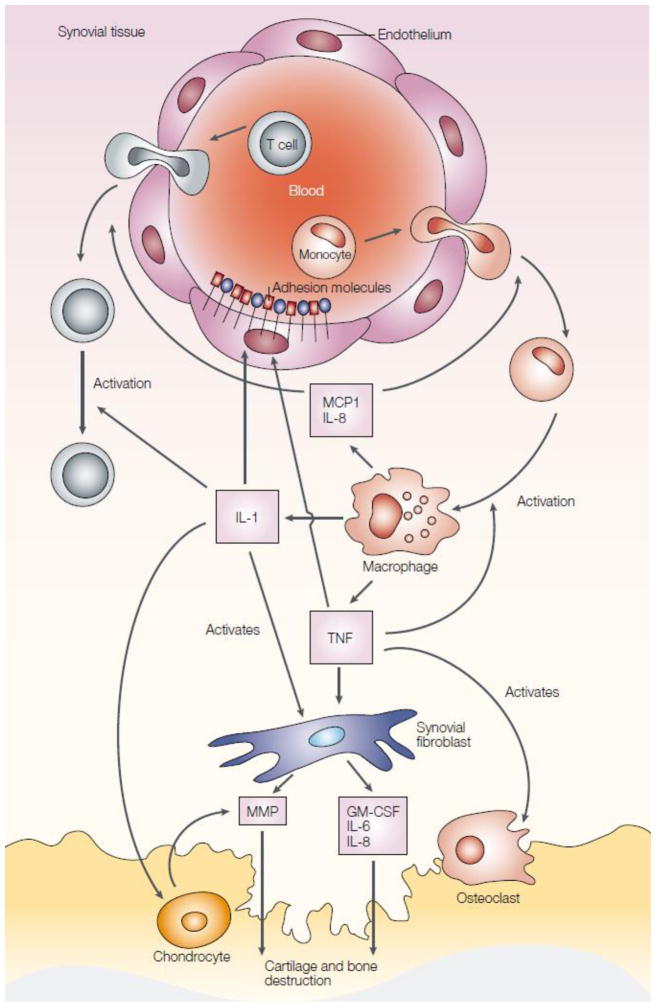

RA is an autoimmune disease characterized by chronic systemic inflammation that predominantly affects articular tissue. It is well established that macrophages act as amplifiers of local and systemic inflammation in RA and contribute directly to matrix degradation [11, 12]. Monocytes are attracted/recruited to the RA joint and differentiate into macrophages. Upon activation, macrophages secrete a number of factors such as TNF-α, IL-1, monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1), and interleukin-8 (IL-8) to initiate a cascade of events leading to cartilage and bone destruction (Fig. 10) [172, 173]. The augmentation of macrophages in the synovium is a prominent feature of inflammatory lesions and appears as an early hallmark of active rheumatic disease. The degree of synovial macrophage infiltration is positively correlated to the degree of joint erosion. The central role of activated macrophages in inflammation and bone homeostasis as well as in modulating the cytokine environment in systemic arthritis make them an ideal target for the treatment of RA [14]. Depletion of macrophages along with their adverse effects from the inflamed tissue would generate therapeutic benefits [174–176]. Currently antimacrophage therapy mainly focuses on: 1) down-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines production by active macrophage; 2) elimination of dysfunctional macrophage from the inflammatory foci or systemic loci and 3) upregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Fig. 10.

Overview of the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Monocytes are attracted to the rheumatoid arthritis joint, where they differentiate into macrophages and become activated. They secrete TNF-α and IL-1. TNF-α increases the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, which recruit more cells to the joint. Chemokines, such as MCP1 and IL-8, are also secreted by macrophages and attract more cells into the joint. IL-1 and TNF induce synovial fibroblasts to express cytokines (such as IL-6), chemokines (such as IL-8), growth factors (such as GM-CSF) and MMPs, which contribute to cartilage and bone destruction. TNF-α contributes to osteoclast activation and differentiation. In addition, IL-1 mediates cartilage degradation directly by inducing the expression of MMPs by chondrocytes. Adapted with permission from [172].

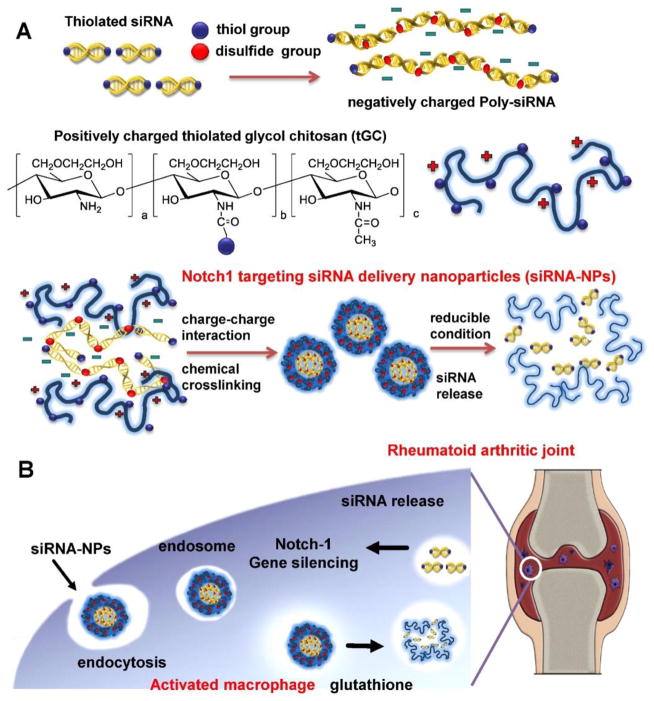

Suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by activated macrophages in synovial tissues has been studied in RA therapy [177–179]. For instance Notch1, a signaling receptor, plays an important role in the regulation of inflammatory responses. Suppression of Notch signaling with γ-secretase inhibitor has been shown to reduce the severity of inflammatory arthritis [180, 181]. Kim et al. fabricated nanoparticles for the delivery siRNA against Notch1 (siRNA-NPs) through self-assembled poly-siRNA and thiolated-glycol chitosan nanoparticles (Fig 11) [182]. Enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect made siRNA-NPs preferentially taken up by activated macrophages and reduced off-target effects of Notch1 knockdown to normal tissues. To quench the inflammation produced by activated macrophage at RA sites, Hayder et al. used azabisphosphonate-capped dendrimer to polarize inflammatory macrophage towards anti-inflammatory phenotype. They observed this method was successful in inhibiting the development of inflammatory arthritis [183].

Fig. 11.

Schematic diagram of Notch1 targeting siRNA delivery nanoparticles (siRNA-NPs). (A) The siRNA-NPs are prepared by encapsulating poly-siRNA into tGC nanoparticles. (B) The siRNA-NPs are taken by activated macrophage and the nanoparticles can deliver therapeutic Notch1-specific siRNA in RA treatment. Adapted with permission from [182].

The severity of RA has been strongly linked to the presence of pro-inflammatory macrophages in the arthritic synovium. Strategies to switch macrophage from predominantly M1 to M2 subtype have been actively evaluated. Jain et al. studied switching the macrophage phenotype by using macrophage targeted tuftsin peptide-functionalized nanoparticles to deliver plasmid DNA encoding anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 [101]. Cytosolic cPLA2α is one of the key molecules influencing development and maintenance of inflammation. Knocking down cPLA2α expression in monocytic cells with siRNA delivered by cationic liposomes was reported to be effective in treating collagen-induced arthritis in vivo [99].

3.4. Dysfunctional macrophages in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

As an integral part of the normal intestinal tissues, tissue macrophages are located in the lamina propria and Peyer's patch and function as immune effector cells without an inflammatory response. Upon inflammatory stimulation, monocytes are recruited from blood to the lamina propria and transform into inflammatory macrophages. Unlike resident intestinal macrophages, these inflammatory macrophages are able to elicit a strong pro-inflammatory response by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and initiate serious tissue damage [15, 16, 184, 185]. Therapeutic strategies to taper TNF-α activity by using anti-TNF-α antibodies such as infliximab have been evaluated for IBD [186, 187]. However, serious infections and side effects have been associated with this approach including immunodeficiency-related infections and psoriasiform skin lesions. Targeted delivery of anti-TNF-α therapeutic agents to the specific inflammatory sites would be desirable for reducing those side effects.

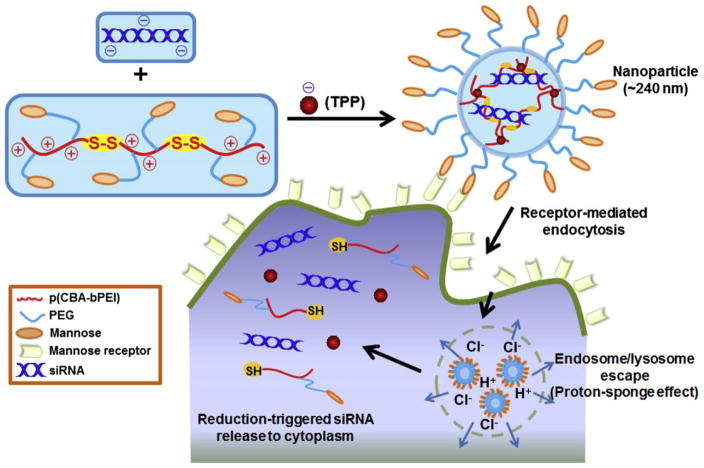

Nanoparticle-mediated siRNA delivery to modulate activated macrophages has also been tried to treat intestinal inflammation. Zhang et al. applied galactosylated trimethyl chitosan – cysteine nanoparticles to deliver siRNA to the activated macrophages in ulcerative colitis to knock down mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase-kinase-kinase 4 (Map4k4). Map4k4 is a key upstream mediator of TNF-α action. Its knockdown reduced TNF-α production and consequently brought about significant histological improvements [106]. TNF-α secretion can also be directly reduced by TNF-α gene knockdown. Laroui et al. developed biodegradable polylactide nanoparticles containing TNF-α siRNA/polyethyleneimine (PEI) complex. They showed that TNFα siRNA/PEI-loaded NPs were successfully delivered to the inflamed macrophages in the colonic tissue and inhibited synthesis/secretion of colonic TNF-α [104]. To improve macrophage targeting for IBD therapy, Xiao et al. synthesized mannose-conjugated bioreducible cationic polymer conjugates and fabricated them into nanoparticles with sodium triphosphate (TPP) for TNF-α siRNA delivery (Fig. 12). The NPs efficiently went into macrophages via mannose receptor-mediated endocytosis and promptly released siRNA achieved via strong “proton-sponge” effect for endosome/lysosome escape and thiol-disulfide exchange for nanoparticle disassembly. Remarkably reduced TNF-α expression and enhanced anti-inflammatory effects were observed both in vitro and ex vivo [105].

Fig. 12.

Schematic illustration of TPP-PPM/siRNA nanoparticle formation, macrophage-targeting delivery and the release of siRNAs to the cytoplasm. Adapted with permission from [105].

Oral drug delivery is considered the most convenient route to administer drugs. Huang et al. developed an oral nanoparticle formulation composed of three components: cationic konjac glucomannan (cKGM), phytagel, and an antisense oligonucleotide against TNF-α. siRNA/cKGM complexes were released and internalized into colonic macrophages specifically as cKGM has high content of mannose, allowing for mannose receptor-mediated uptake. As a result, secretion of TNF-α was significantly decreased accompanied with symptom alleviation of the dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis [103].

3.5. Dysfunctional macrophages in obesity and ensuing insulin resistance for type 2 diabetes

In the adipose tissue of lean individuals, ATMs constitute only 10–15% of the cell population, and they are primarily anti-inflammatory subtype. In contrast, 40–50 % of the cells in the adipose tissue of obese individuals are ATMs and the majority is pro-inflammatory M1-like subtype. Increasing evidence shows the causal relationship between development of Type 2 diabetes and increased M1 macrophage infiltration in the adipose tissue. Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of chronic low-grade systemic inflammation induced by M1-like macrophages may help reduce obesity-induced insulin resistance [21, 23, 188].

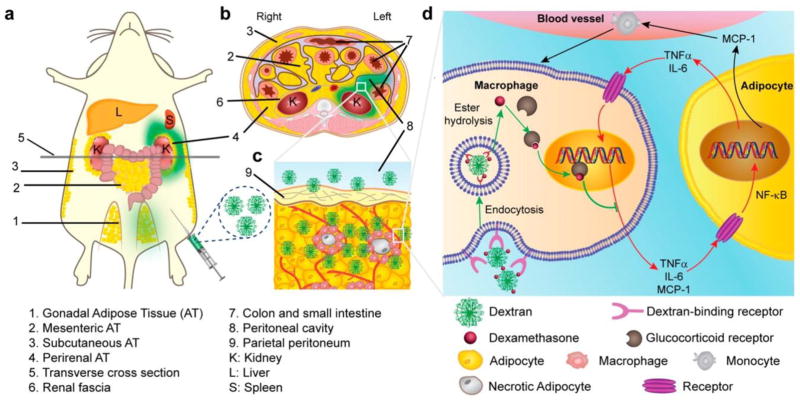

Anti-inflammatory drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin and glucocorticoids (like dexamethasone) have been commonly used in the clinic to treat inflammation involved in obesity-related complications [189–191]. However, high doses and long term administration cause serious adverse effects including bleeding, gastrointestinal irritation and Cushing-like syndrome. Clinical evidence suggests that these side effects are primarily due to off-target drug effects to liver hepatocytes, muscle cells and enterocytes. Therefore, the application of ATM-targeted nanomedicines could substantially resolve these limitations and improve therapeutic outcomes [21, 192]. Ma et al applied nanostructured polysaccharides to target ATMs in obese mice (Fig. 13). The results suggested that nanoparticles in 70–500 nm efficiently transported to the visceral adipose tissue and bound to the macrophages following regional peritoneal administration. This strategy successfully reduced significant liver uptake. Because of high adipose tissue specificity of the nanocarrier, single-dose was found to be effective reducing pro-inflammatory markers in the adipose tissue of obese mice [108].

Fig. 13.

Proposed mechanism of dextran–dexamethasone conjugate accumulation in obese VAT, macrophage uptake, and uncoupling of the paracrine loop between M1 macrophages and adipocytes: (a) dextran conjugates (green color) accumulate in the left perirenal adipose tissue (AT) and left gonadal AT after intraperitoneal left-side injection in obese mouse. The anatomical depiction shows mice, which have one mesenteric, two perirenal, and two gonadal AT depots. (b) Transverse cross section of mouse abdomen showing green dextran solution location after administration to the peritoneal cavity. (c) Rapid association of dextran conjugate with M1 macrophages in inflamed AT is enabled by transport across the peritoneum to directly access interstitial cells. (d) Simplified summary of inhibition of paracrine loop between M1 macrophages and adipocytes with dextran–dexamethasone conjugates. In the obese state, hypertrophied adipocytes produce MCP-1, which recruits monocytes, and local release of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-6 induces an M1 macrophage phenotype. M1 macrophages further release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including MCP-1, TNFα, and IL-6, which further enhance the pro-inflammatory gene expression of adipocytes through NF-κB and further enhance adipocyte inflammation. Dextran conjugates are taken up by M1 macrophages through receptor-mediated endocytosis, and free dexamethasone is released within the cells after esterase hydrolysis. Dexamethasone then binds to the glucocorticoid receptor that inhibits the transcription of pro-inflammatory genes. Additional implicated cells (e.g., T cells) and altered metabolic pathways are not depicted. Adapted with permission from [108].

Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) agonists such as rosiglitazone (RSG) have been applied clinically to attenuate macrophage-triggered inflammatory responses in the obesity [193, 194]. However, RSG causes serious side effects particularly to the heart and increased the risk of fatal cardiac arrhythmia. To reduce their side effects, Mascolo et al. synthesized polymeric NPs of 200 nm for RSG delivery (RSG-NPs). RSG-NPs were preferentially taken up by circulating monocytes and resident hepatic macrophages (kupffer cells). Consequently, RSG-NPs specifically alleviated inflammatory reaction in the white adipose tissue and liver. Unlike systemic exposure of free RSG, RSG-NPs did not alter genes related to normal lipid metabolism or cardiac function, suggesting reduction or avoidance of free RSG-related side effects [107].

3.6. Dysfunctional macrophages in human immunodeficiency virus type I (HIV-1)

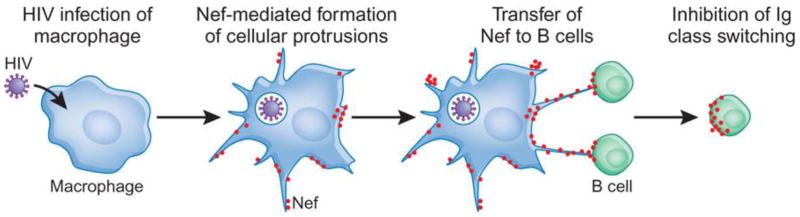

Nowadays, HIV infection remains a severe global life-threatening disease. It has high morbidity and mortality rates and poses tremendous socioeconomic burden. Studies on the pathophysiologic mechanisms of HIV infection uncovered the crucial roles that macrophages play in the various phases of HIV-1 infection [25]. Macrophages, similar to CD4+ T helper cells, express high levels of the HIV-1 receptor CD4 on the surface and are highly permissive to HIV-1 infection. In the early phase, macrophages are critically involved in the initiation and orchestration of the adaptive cellular and humoral immune response to diminish viral infection. While with the advancement of HIV infection, highly migratory infected-perivascular macrophages serve as a reservoir to further hijack and disseminate the virus throughout the patients’ body [6, 195–197]. In addition, HIV-infected macrophages in lymph nodes express viral protein negative regulatory factor (Nef), which is further shuttled to B cells. Upon arrival at B lymphocytes, Nef damages protective functions of B cell (Fig.14). Furthermore, Nef-activated and HIV-infected macrophages might also be related to the apoptosis of CD4+ and CD8+ T helper cells [198]. Taken together, HIV-infected macrophages can be a therapeutic target for treatment of HIV-related diseases.

Fig. 14.

HIV-1-infected macrophages shuttle Nef to B cells to impair follicular IgG2 and IgA responses. Adapted with permission from [198].

The current HIV-1 treatment is mainly based on antiretroviral therapy (ART). However, even with long term treatment with ART, infected cells still cannot be completely eliminated from the body. Virus levels rapidly rebound once ART treatment is stopped. The recurrence is attributed to 1) persistence of long-lived HIV-1 reservoirs such as infected-macrophages; 2) difficult eradication of HIV-1 from those reservoirs, due to ineffective targeting of HIV-1-infected macrophages by antiviral drugs; 3) resistance of infected-macrophages to antiretroviral drugs [25, 26, 116, 199]. Therefore, efficiently targeting virus-infected macrophages is needed to reduce recurrence [200, 201]. To specifically deliver ARV to HIV-1 infected-macrophage, infected-macrophage targeting delivery systems have been developed. Based on the interaction between 1,3-β-glucan (GLU) and recognition receptor dectin-1 on the surface of infected-macrophages, Kutscher et al designed GLU-decorated chitosan (CS) shell and poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) core nanoparticles(GLU-CS-PLGA) for delivery of antiretroviral drug nevirapine. They showed that GLU-CS-PLGA significantly increased the drug uptake of THP-1-derived macrophages and mainly targeted macrophages in the liver and kidney [116]. As activated macrophages express folate receptor at an elevated level, Puligujja et al. utilized folic acid-modified polymeric nanoparticles containing atazanavir/ritonavir to enhance antiretroviral activities [202]. Gallium (Ga) has been utilized as viral growth inhibitor. Narayanasamy et al. developed macrophages targeting Ga nanoparticles. Ga nanoparticle was internalized by macrophages and maintained sustained-release for an extended period of time. Significant inhibition of HIV in the macrophage lasted 5 days following single administration [203].

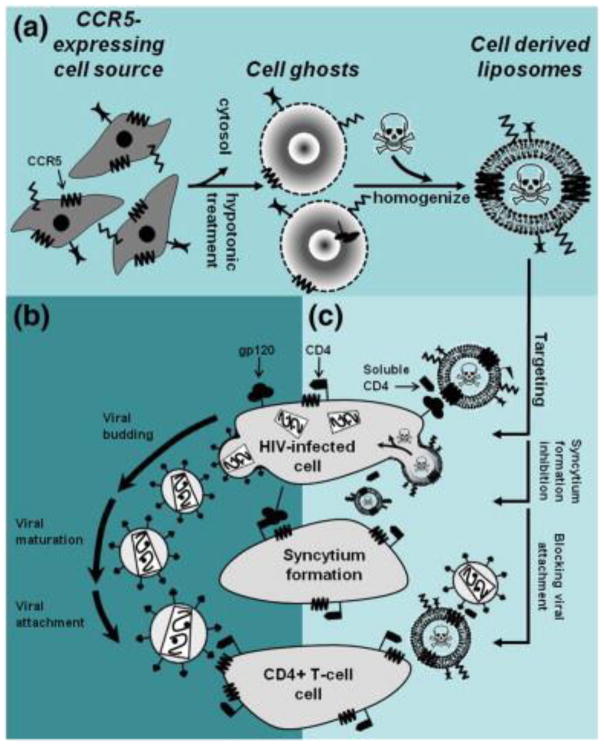

The application of molecular probing technology has led to discovery of more and more essential elements such as proteins, enzymes and receptors intimately involved in the infection and transmission of HIV-1. These elements can potentially serve as novel targets for development of anti-HIV-1 therapies. For instance, an adhesion molecule galectin-1 is overexpressed in macrophages and implicated in HIV-1 viral dissemination. Reynolds et al. demonstrated that galectin-1 siRNA delivered by gold nanorods efficiently inhibited galectin-1 gene expression on macrophages, which could potentially reduce the galectin-1-mediated HIV-1 infection [204]. The C-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) protein, predominantly expressed on HIV-1 host cells including macrophages, facilitates the entry of HIV-1 into macrophage and later transmission during the acute infection phase. Bronshtein et al. employed cytoplasmic membranes from cells expressing CCR5 to decorate liposomes containing toxin EDTA to efficiently target these HIV-infected cells (Fig. 15). CCR5-expressing cell membrane-derived liposomes specifically targeted HIV-infected cells and caused 60 % reduction in the viability of HIV-infected cells while they did not affect normal cells [205].

Fig. 15.

The concept and rational of targeting HIV-infected cells by CCR5-conjuagted cell derived liposomes. (a) Cell-derived liposomes are prepared by homogenization and extrusion of ghost cells, which membranally express the HIV co-receptor CCR5. The source of the cells can be any autologous lineages that express CCR5 (naturally or exogenously). (b) Cell derived liposomes, which will be targeted against gp120-expressing cells using CCR5 as a targeting ligand, can interfere with all extracellular steps of viral pathogenesis; Such as, syncytium formation between infected cells and uninfected susceptible cells, viral budding from infected cells, viral maturation and attachment to susceptible cells. (c) The cell derived liposomes (when administered along with soluble CD4) are primarily intended to target, fuse with and deliver their cytotoxic content into gp120-expressing/HIV-infected cells. Accordingly, the same mechanism of gp120 binding may also prove efficient in preventing syncytium formation and inactivation of roaming virions by clustering. Adapted with permission from [205].

To utilize macrophages’ innate targeting property, Dou et al. packaged nanoparticles containing indinavir (NP-IDV) into bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs). Based on the preferred distribution of macrophages in vivo, NP-IDV-BMMs increased drug accumulation in areas of active viral replication and sustained local drug release for more than 2 weeks [206]. This method has fewer side effects and higher therapeutic outcomes.

4. Nanoparticle-based theranostics for dysfunctional macrophage-associated diseases

To timely estimate the protective and detrimental effects of targeting macrophages, there is a need to develop “theranostics” that brings therapy and diagnosis together [207, 208]. Theranostics would provide essential information for developing better therapeutic intervention such as the ability of drug carriers to target macrophages (or bio-distribution), therapeutic outcome and toxicity profile in real-time. The structural features of nanoparticles that can be utilized include large surface-area-to-volume ratio for high payloads of therapeutic and imaging agents, small size enabling them to extravasate into leaky vasculature, and adaptable chemistries for functionalization with targeting ligands as well as environmental response stimulus (such as pH, temperature, enzymes, and redox potential) [209].

The high infiltration of TAMs in many human tumor types (such as lymphoma, liver, prostate, ovarian, breast and non-small cell lung cancers) is closely related to faster cancer progression and shorter patient survival [210–212]. Imaging TAMs provides invaluable prognostic information (TAMs concentration and tumor dimension) and allows for quantitative assessment of therapeutic outcomes [213]. Keliher et al. designed dextran nanoparticle labeled with zirconium-89 as a new macrophage imaging agent. Their work demonstrated that in a cancer mouse model the nanoparticles almost exclusively co-localized with TAMs at 24 h post-administration [214]. Daldrup-Link et al. used FDA-approved superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles to prove the feasibility of TAMs targeting and imaging in breast cancer. They revealed the preferential uptake of the iron oxide nanoparticles by TAMs and delayed MRIs signal in the tumor [215].

Atherosclerotic plaques develop within the arterial wall. However, as they are not easily detected by conventional angiography, information regarding the underlying processes of plaque rupture is rather limited. Techniques for efficient plaque-targeted imaging of atherosclerosis are greatly needed. Macrophage-targeting strategy is one way for imaging of atherosclerosis [146, 216, 217]. Tarin et al. developed an atherosclerotic plaque targeting probe based on gold-coated iron oxide nanoparticles modified with an anti-CD163 antibody. It binds specifically to the membrane receptor CD163 over-expressed by macrophages at inflammatory sites such as atherosclerotic plaques [218]. El-Dakdouki et al. decorated magnetic glyconanoparticles with hyaluronan, which selectively binds to CD44 overexpressed by macrophages within vulnerable plaques [219]. As a ligand for SR-A overexpressed by activated macrophages within atherosclerotic plaques, dextran sulfate (DS) was employed by You et al. to coat SPIO for imaging of atherosclerosis [220]. Similar macrophages-targeted strategies for imaging of atherosclerosis were also reported by targeting CD36 [161, 192, 221].

Given that macrophages infiltration is identified in early and even preclinical stages of rheumatoid synovitis, tracking macrophages infiltration in rheumatoid synovitis is of great importance to early detection of inflammation in RA [222]. Van der Laken et al. demonstrated that tracer 11C-(R)-PK11195 could interact with peripheral benzodiazepine receptors on macrophages in rheumatoid synovitis, thus enabling real-time monitoring of therapeutic outcomes [223]. Inflammatory bowel disease results from an inappropriate immune response to the intestinal microbes in a genetically susceptible host [224]. Infiltration of macrophages in the gastrointestinal tract plays a key role in host defense in IBD through the secretion of cytokines and the activation of downstream pathways. Therefore, imaging of macrophages infiltration in the intestine may allow for early detection of inflammation, assessment of disease progression, and evaluation of therapeutic intervention outcomes [225].Wu et al. demonstrated that superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles and 111In-labeled macrophages could be used to monitor the macrophages’ recruitment to disease’s foci and disease activity [226]. Type2-diabetes is also characterized by microvascular changes, monocyte recruitment and macrophage activation. The inability to “monitor” the disease initiation, progression or regression especially during the latent phase has been a major limitation for better understanding, prevention and cure of diabetes. Hence early diagnosis and monitoring of disease progression for patients with diabetes could be beneficial to both patients and caregivers [227–229]. In a pilot clinical study, non-diabetic healthy volunteers and patients with onset diabetes were administrated with a clinically approved MRI contrast-imaging agent Feraheme (polyglucose sorbitol carboxymethylether-coated superparamagnetic iron oxide), which is readily taken up by macrophages owing to its size and surface properties. This allowed for the effective visualization of the pancreas and distinction of onset diabetes patients from nondiabetic controls [112].

5. Concluding remarks and future perspectives

In summary, dysfunctional macrophages play critical roles in various diseases. Due to plasticity, dysfunctional macrophages undergo substantial changes in phenotype and function. Therefore, the importance of understanding and identification of distinct disease-promoting macrophages under pathological situations deserves due attention. Blockade of dysfunctional macrophages accumulation, conversion of pathogenic macrophages to therapeutic ones, and restoration of biological function of disease-fighting macrophages underlie the basis of macrophage-targeted therapeutic strategies.

While many significant advances have been made, there is room for improving the efficacy of targeting dysfunctional macrophages in a variety of diseases. Questions remain yet to be fully addressed including correct modulation of function of specific macrophage phenotype to exert therapeutic intervention, monitoring therapeutic response accurately and timely, and avoiding the compromised immune-protective functions of macrophages caused by therapeutic intervention, and many others. To translate macrophage targeting nanomedicines from bench to bedside, immediate issues must be considered including: 1) elucidation of the relationship between macrophages and nanoparticles and utility of macrophage-specific targeting; 2) development of theranostic nanomedicines, enabling therapeutic activities and real-time monitoring of the progression of diseases and during treatments; and 3) pre-clinical studies in diseased models such as PK/PD, metabolism and long-term toxicity evaluation. As understanding of the relationship between dysfunctional macrophages and diseases continues to evolve, we are optimistic that nanomedicines will be designed more rationally to target macrophages for better treatment of dysfunctional macrophage-associated diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by VCU’s CTSA award (UL1TR000058) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the CCTR Endowment Fund of Virginia Commonwealth University to HY and SG as well as NSF CAREER award CBET0954957 (HY).

Glossary of abbreviations

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- ABCG1

ATP-binding cassette transporter G1

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- AM NP

amphiphilic core-shell layered nanoparticle

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- ATM

adipose tissue macrophage

- AuNS

gold nanoshell

- BMM

bone marrow-derived macrophage

- CCR5

C-C motif chemokine receptor 5

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- CE

cholesteryl ester

- CEH

cholesteryl ester hydrolase

- CS

chitosan

- DNP

dendrimer nanoparticle

- EGCG

epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- EPR

enhanced permeation and retention

- FA

folic acid

- FC

free cholesterol

- FR-β

folate receptor beta

- Ga

gallium

- GLU

1,3-β-glucan

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor

- HA

hyaluronic acid

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- ICAM1

intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- IL

interleukin

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LT

lovastatin

- LXR

liver X receptor

- MCP1

monocyte chemotactic protein 1

- M-CSF

macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MPCM

macrophage cell membrane

- Nef

negative regulatory factor

- NP

nanoparticle

- NP-IDV

nanoparticles containing indinavir

- oxLDL

oxidized LDL

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- PLGA

polylactic-co-glycolic acid

- PPARγ

peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor γ

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RCT

reverse cholesterol transport

- rHDL

reconstituted HDL

- RSG

rosiglitazone

- S-HDL

statin-loaded HDL

- SR

scavenger receptor

- SR-A

scavenger receptor class A

- SR-B1

scavenger receptor class B, type 1

- TAM

tumor associated macrophage

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TPP

sodium triphosphate

- VCAM1

vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hettinger J, Richards DM, Hansson J, Barra MM, Joschko AC, Krijgsveld J, Feuerer M. Origin of monocytes and macrophages in a committed progenitor. Nature immunology. 2013;14:821–830. doi: 10.1038/ni.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Randolph GJ. Origin and functions of tissue macrophages. Immunity. 2014;41:21–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nature reviews immunology. 2011;11:723–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee KM, Yin C, Verschoor CP, Bowdish DM. Macrophage function disorders. eLS. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhargava P, Lee C-H. Role and function of macrophages in the metabolic syndrome. Biochemical Journal. 2012;442:253–262. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNelis JC, Olefsky JM. Macrophages, immunity, and metabolic disease. Immunity. 2014;41:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Palma M, Lewis CE. Macrophage regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies. Cancer cell. 2013;23:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. The Lancet Oncology. 2014;15:e493–e503. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germano G, Frapolli R, Belgiovine C, Anselmo A, Pesce S, Liguori M, Erba E, Uboldi S, Zucchetti M, Pasqualini F. Role of macrophage targeting in the antitumor activity of trabectedin. Cancer cell. 2013;23:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinne RW, Bräuer R, Stuhlmüller B, Palombo-Kinne E, Burmester G-R. Macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2000;2:1. doi: 10.1186/ar86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McInnes IB, Schett G. Cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2007;7:429–442. doi: 10.1038/nri2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Müller-Ladner U, Pap T, Gay RE, Neidhart M, Gay S. Mechanisms of disease: the molecular and cellular basis of joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature clinical practice Rheumatology. 2005;1:102–110. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinsbroek SE, Gordon S. The role of macrophages in inflammatory bowel diseases. Expert reviews in molecular medicine. 2009;11:e14. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xavier R, Podolsky D. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li AC, Glass CK. The macrophage foam cell as a target for therapeutic intervention. Nature medicine. 2002;8:1235–1242. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13:709–721. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraakman MJ, Murphy AJ, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Kammoun HL. Macrophage polarization in obesity and type 2 diabetes: weighing down our understanding of macrophage function? M1/M2 Macrophages: The Arginine Fork in the Road to Health and Disease. 2015:195. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olefsky JM, Glass CK. Macrophages, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Annual review of physiology. 2010;72:219–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tesch G. Role of macrophages in complications of type 2 diabetes. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2007;34:1016–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castoldi A, de Souza CN, Câmara NOS, Moraes-Vieira PM. The macrophage switch in obesity development. Frontiers in immunology. 2015;6 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carvalheira JBC, Qiu Y, Chawla A. Blood spotlight on leukocytes and obesity. Blood. 2013;122:3263–3267. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-459446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppensteiner H, Brack-Werner R, Schindler M. Macrophages and their relevance in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type I infection. Retrovirology. 2012;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Herbein G. The macrophage: a therapeutic target in HIV-1 infection. Molecular and cellular therapies. 2014;2:1. doi: 10.1186/2052-8426-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchem JB, Brennan DJ, Knolhoff BL, Belt BA, Zhu Y, Sanford DE, Belaygorod L, Carpenter D, Collins L, Piwnica-Worms D. Targeting tumor-infiltrating macrophages decreases tumor-initiating cells, relieves immunosuppression, and improves chemotherapeutic responses. Cancer research. 2013;73:1128–1141. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chellat F, Merhi Y, Moreau A, Yahia LH. Therapeutic potential of nanoparticulate systems for macrophage targeting. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7260–7275. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly C, Jefferies C, Cryan S-A. Targeted liposomal drug delivery to monocytes and macrophages. Journal of drug delivery. 2010;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/727241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia W, Hilgenbrink AR, Matteson EL, Lockwood MB, Cheng J-X, Low PS. A functional folate receptor is induced during macrophage activation and can be used to target drugs to activated macrophages. Blood. 2009;113:438–446. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-150789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svenson S, Prud'homme RK. Multifunctional nanoparticles for drug delivery applications: imaging, targeting, and delivery. Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung BL, Toth MJ, Kamaly N, Sei YJ, Becraft J, Mulder WJ, Fayad ZA, Farokhzad OC, Kim Y, Langer R. Nanomedicines for endothelial disorders. Nano today. 2015;10:759–776. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Drug delivery systems: entering the mainstream. Science. 2004;303:1818–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.1095833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. Nanomedicine: current status and future prospects. The FASEB journal. 2005;19:311–330. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2747rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun T, Zhang YS, Pang B, Hyun DC, Yang M, Xia Y. Engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2014;53:12320–12364. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner V, Dullaart A, Bock A-K, Zweck A. The emerging nanomedicine landscape. Nature biotechnology. 2006;24:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/nbt1006-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim DK, Dobson J. Nanomedicine for targeted drug delivery. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2009;19:6294–6307. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Couvreur P. Nanoparticles in drug delivery: past, present and future. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2013;65:21–23. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gref R, Domb A, Quellec P, Blunk T, Müller R, Verbavatz J, Langer R. The controlled intravenous delivery of drugs using PEG-coated sterically stabilized nanospheres. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2012;64:316–326. doi: 10.1016/0169-409X(95)00026-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2013;65:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pattni BS, Chupin VV, Torchilin VP. New developments in liposomal drug delivery. Chemical reviews. 2015;115:10938–10966. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kneidl B, Peller M, Winter G, Lindner LH, Hossann M. Thermosensitive liposomal drug delivery systems: state of the art review. International journal of nanomedicine. 2014;9:4387. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S49297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nirmala M, Nagarajan R. Microemulsions as Potent Drug Delivery Systems. J Nanomed Nanotechnol. 2016;7:e139. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muzaffar F, Singh U, Chauhan L. Review on microemulsion as futuristic drug delivery. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;5:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu L, Liu Y, Chen Z, Li W, Liu Y, Wang L, Ma L, Shao Y, Zhao Y, Chen C. Morphologically Virus - Like Fullerenol Nanoparticles Act as the Dual - Functional Nanoadjuvant for HIV - 1 Vaccine. Advanced Materials. 2013;25:5928–5936. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miura Y, Takenaka T, Toh K, Wu S, Nishihara H, Kano MR, Ino Y, Nomoto T, Matsumoto Y, Koyama H. Cyclic RGD-linked polymeric micelles for targeted delivery of platinum anticancer drugs to glioblastoma through the blood–brain tumor barrier. ACS nano. 2013;7:8583–8592. doi: 10.1021/nn402662d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kesharwani P, Jain K, Jain NK. Dendrimer as nanocarrier for drug delivery. Progress in Polymer Science. 2014;39:268–307. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Svenson S, Tomalia DA. Dendrimers in biomedical applications—reflections on the field. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2012;64:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang J, Zhang Q, Chang H, Cheng Y. Surface-engineered dendrimers in gene delivery. Chemical reviews. 2015;115:5274–5300. doi: 10.1021/cr500542t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baeza A, Colilla M, Vallet-Regí M. Advances in mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted stimuli-responsive drug delivery. Expert opinion on drug delivery. 2015;12:319–337. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2014.953051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gimeénez C, de la Torre C, Gorbe Mn, Aznar E, Sancenón Fl, Murguía JR, Martínez-Máñez R, Marcos MD, Amorós P. Gated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for the controlled delivery of drugs in cancer cells. Langmuir. 2015;31:3753–3762. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alkilany AM, Thompson LB, Boulos SP, Sisco PN, Murphy CJ. Gold nanorods: their potential for photothermal therapeutics and drug delivery, tempered by the complexity of their biological interactions. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2012;64:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rana S, Bajaj A, Mout R, Rotello VM. Monolayer coated gold nanoparticles for delivery applications. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2012;64:200–216. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vigderman L, Zubarev ER. Therapeutic platforms based on gold nanoparticles and their covalent conjugates with drug molecules. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2013;65:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Probst CE, Zrazhevskiy P, Bagalkot V, Gao X. Quantum dots as a platform for nanoparticle drug delivery vehicle design. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2013;65:703–718. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen M-L, He Y-J, Chen X-W, Wang J-H. Quantum-dot-conjugated graphene as a probe for simultaneous cancer-targeted fluorescent imaging, tracking, and monitoring drug delivery. Bioconjugate chemistry. 2013;24:387–397. doi: 10.1021/bc3004809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong BS, Yoong SL, Jagusiak A, Panczyk T, Ho HK, Ang WH, Pastorin G. Carbon nanotubes for delivery of small molecule drugs. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2013;65:1964–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mehra NK, Mishra V, Jain N. A review of ligand tethered surface engineered carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1267–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Juliano R. Nanomedicine: is the wave cresting? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2013;12:171–172. doi: 10.1038/nrd3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Etheridge ML, Campbell SA, Erdman AG, Haynes CL, Wolf SM, McCullough J. The big picture on nanomedicine: the state of investigational and approved nanomedicine products. Nanomedicine: nanotechnology, biology and medicine. 2013;9:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]