Abstract

Background

Despite the dangers associated with hookah tobacco smoking, use and popularity in the United States among young adults continue to increase. While quantitative studies have assessed users’ attitudes towards hookah, qualitative research can provide a more in-depth description of positive and negative attitudes and beliefs associated with hookah use.

Objectives

To determine outcome expectancies associated with hookah use among young adults.

Methods

We conducted six focus groups in 2013 to identify outcome expectancies associated with hookah use. Participants (N=40) were young adults aged 18–23 who reported hookah use in the past three months. Using Outcome Expectancy Theory perspective, we posed the question “Hookah smoking is _______?” to elicit words or phrases that users associate with hookah use.

Results

Over 75% of the users’ hookah use outcome expectancies were positive, including associating hookah smoking with relaxation and a social experience. Content analysis of the words engendered 6 themes. These themes included Social Appeal, Physical Attractiveness, Pleasant Smoke, Comparison to Cigarettes, Relaxation, Deterrents. Fewer negative hookah use expectancy words and phrases were identified, but included “tar” and “cough”.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that participants lacked basic knowledge about hookah tobacco smoking, had misconceptions about its danger, and had many positive associations with hookah use. Incorporating components addressing positive hookah expectancies may improve the efficacy of established and new hookah use prevention and cessation interventions and policies.

BACKGROUND

Tobacco smoking using a hookah pipe exposes users to high concentrations of many toxicants. A typical hookah session, which can last 45 minutes or more, exposes users to high amounts of carbon monoxide (Barnett, Curbow, Soule, Tomar, Thombs, 2011; Shihadeh & Saleh, 2005), 30 times the carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Sepetdjian, Shihadeh, Saliba, 2008), 40 times the tar (Shihadeh & Saleh, 2005), and twice the amount of nicotine (Katurji, Daher, Sheheitli, Saleh, Shihadeh, 2010) compared to smoking a single cigarette. Daily hookah users have blood nicotine concentrations approaching that of a half pack a day (10/day) cigarette smoker (Neergaard, Singh, Job, Montgomery, 2007). Because hookah smokers are exposed to large concentrations of toxicants during a single hookah smoking session, hookah use is associated with cardiovascular disease (Jabbour, El-Roueihab, Sibai, 2003) and cancer (Akl et al., 2010). Given the rapidly increasing popularity of hookah smoking among young adults in the United States (Arrazola et al., 2015; Barnett, Forrest, Porter, Curbow, 2014) and the known negative health effects associated with hookah use, the long-term impact among adolescents and young adults is a major public health concern.

Past 30-day hookah use has been found to be associated with younger age (Eissenberg, Ward, Smith-Simone, Maziak, 2008; Primack et al., 2008; Primack, Walsh, Bryce, Eissenberg, 2009), being male (Grekin & Ayna, 2008; Smith-Simone, Maziak, Ward, Eissenberg, 2008; Sterling & Mermelstein, 2011), and white race (Eissenberg, Ward, Smith-Simone, Maziak, 2008; Primack et al., 2008). More recent research has suggested females are catching up and closing the gap on hookah use prevalence (Barnett et al., 2013a). In a recent study, Barnett et al. (2013a) reported that ever and past year hookah use had surpassed cigarette use prevalence among college students.

As proposed in Outcome Expectancy Theory, individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors they associate with positive outcomes and are less likely to engage in behaviors they associate with negative outcomes (Kirsch, 1995; Bandura, 1986). These associations can vary between simple beliefs (smoking is bad for my health) and complex beliefs (smoking will result in peer group acceptance) as well as vary from individual to individual. Furthermore, since these associations or outcome expectations are directly related to individuals’ beliefs, their perception of reality may not be accurate. The relationship between positive outcome expectancies and increased substance use behaviors has been previously established. For example, previous research has identified six expectancy themes related to alcohol use, some of which were in direct opposition to the physiological effects of alcohol (e.g., sexual enhancement; Brown, Christiansen, Goldman, 1987). Outcome Expectancy Theory has also been applied to cigarette use (Brandon, Juliano, Copeland, 1999; Hendricks & Brandon, 2005). In a study by Hendricks & Brandon (2005), college students were interviewed and asked to complete the sentence “Smoking makes one ______” with as many words as they could think of in 30 seconds. The word associations of the participants were used to create seven expectancy themes associated with cigarette smoking: negative consequences, positive consequences, negative reinforcement, appetite/weight control, addiction, social enhancement, and arousal.

Despite the success of previous applications of Outcome Expectancy Theory to substance use behaviors, it has not yet been applied to hookah use. Moreover, very little is known with regard to how attitudes and beliefs shape hookah use in young adults (Barnett et al., 2013b; Rezk-Hanna, Macabasco-O’Connell, & Woo, 2014). In a study of college-aged, hookah smoking adults by Griffiths & Ford (2014), 20 semi-structured interviews revealed that participants perceived low vulnerability of contracting health diseases or conditions associated with hookah. This is supportive of the findings by Primack et al. (2008), which suggested that the lack of negative attitudes toward hookah were one reason for the rise in use. Similar to other forms of tobacco use, over 40% of hookah smokers may continue to smoke despite being aware of the health risks (Rezk-Hanna, Macabasco-O’Connell, & Woo, 2014). The need to fully understand positive and negative attitudes associated with hookah tobacco smoking is paramount for determining reasons for hookah use and developing interventions to prevent hookah use. Expectancies identified for cigarette use in a college population likely will not translate to the same expectancies for hookah use. Hookah smoking and cigarette smoking pose similar health risks, however, the appeals of hookah smoking are different from cigarette smoking and therefore the expectancies associated with hookah use need to be examined. Therefore, the goal of this research was to examine the hookah use expectancies among young adult hookah users.

METHODS

Recruitment and Inclusion Criteria

This study was approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. In 2013, young adult hookah users were invited to participate in focus groups to discuss their experiences with hookah use. Research staff placed advertisements for the study in locations to attract young adults, including both college students and non-students. Advertisement locations included a university campus near dormitories, dining halls, and academic buildings; various community locations including bus stops, bars/night clubs, recreational facilities, and notice boards near establishments that provided hookah smoking. Individuals who were interested in participating in the study contacted research personnel by email or phone and were screened for inclusion criteria. In order to provide meaningful responses regarding hookah smoking outcome expectancy beliefs, participants were required to have at least some recent hookah smoking experience, defined as at least one time in the past three months. Those who reported hookah use within the past three months who were young adults between the ages of 18 and 24 and were available for focus group participation (n=47) were invited to participate in a scheduled focus group. The majority of invited participants attended focus groups (N=40, 85%) and were given $25 Visa gift cards for participating.

Focus Group Sessions

Hookah Use Word Generation

A structured prompt that allowed for a variety of responses was used to elicit words associated with hookah smoking outcome expectancy beliefs. At the beginning of each focus group, participants were asked to respond with words or phrases that appropriately completed the statement “Hookah smoking is…” This prompt was informed by previous research on cigarette smoking outcome expectancies (Hendricks & Brandon, 2005). There were no restrictions on the words that participants provided aside from needing to be related to hookah use. The words generated during the discussion were recorded on a display board. In addition to volunteering words that completed the focus prompt, focus group facilitators encouraged participants to describe experiences that were representative of the generated words. After participants agreed that the lists of hookah use words and phrases was complete, and saturation had been reached, focus group facilitators instructed the group to determine if each word was a positive, negative, or both a positive and negative expectancy associated with hookah use in order distinguish between the theoretical constructs.

At the conclusion of the focus group but prior to leaving, participants were asked to complete a brief anonymous survey to obtain demographic information and substance use information including hookah use, other tobacco use, and alcohol use. This survey was administered after the focus groups so that questions on other forms of substance use did not influence the focus group responses.

Data Analysis

The focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed. The words and phrases generated were reviewed after each focus group session. Data collection was discontinued once saturation was reached, in which all researchers agreed that no new information had emerged from the last focus group. Three researchers reviewed the words from each focus group independently to generate hookah outcome expectancy themes and their relation to positive or negative expectancies. The team then came together as a group to compare themes and reached consensus on a final list of themes and their placement with respect to the theoretical constructs (positive or negative). Transcripts of the focus group sessions were referred to throughout the theme generation process to ensure the researchers appropriately interpreted the meaning of the participant-generated words and phrases. Basic descriptive analyses of demographics and tobacco use patterns were conducted on responses to the survey.

RESULTS

Participants

A total of six focus groups were conducted over 6 months, between January and July, 2013. Groups ranged in size from five to nine participants, totaling 40 hookah smokers (47 participants were invited to scheduled focus groups, 7 did not attend); 55% were female. Focus groups lasted between 35 and 100 minutes (average duration = 60.7 minutes). The participants were 72.5% Caucasian, 7.5% black/African American, 10% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 10% other. Additionally, 30% identified as Hispanic, and 12.5% reported being of Arab/Middle Eastern descent. Participants ranged from 18 to 23 years of age (M=19.2, SD=1.4). Four of the focus groups were comprised of current college students and two included non-college students. While previous research indicates that hookah use is common among college students (Barnett et al., 2013; Eissenberg et al., 2008; Goodwin et al., 2014; Rahman et al., 2012; Primack et al., 2008; Sutfin et al., 2011; Grekin, & Ayna, 2008; Jarret et al., 2012), separate non-college student focus groups were included to obtain responses that may have been unique to non-college students. However, differing themes did not emerge in the focus groups, and therefore groups were combined for analysis.

While all participants reported smoking hookah at least once during the past three months to be eligible for the study, 72.5% reported smoking hookah in the past 30 days. Moreover, 52.5% reported hookah as the first tobacco product they ever tried followed by cigars/cigarillos (27.5%), and cigarettes (20%). The majority of male (88.9%; N=16) and female (59.1%; N=13) participants reported trying cigarettes in their lifetime. Past 30 day cigarette use was reported by 61% of males and 9.1% of females.

Word Generation

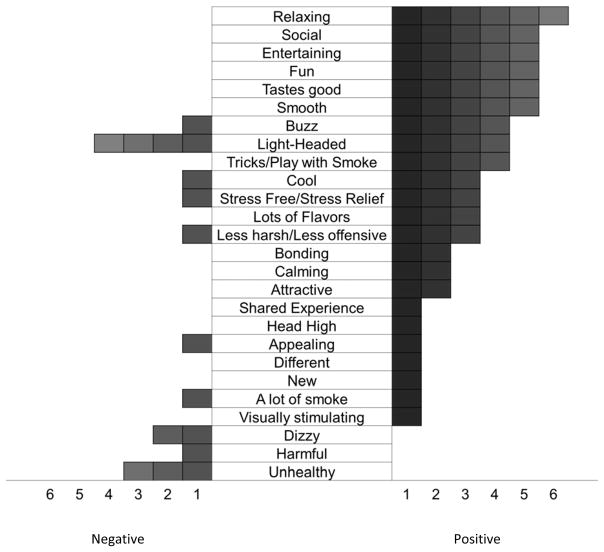

During the word and phrase generation task, participants identified a total of 277 (127 unique – a full list can be made available on request to the corresponding author) hookah-related words and phrases. More than 75% of responses were identified by participants as positive associations of hookah use. All six focus groups identified hookah smoking as relaxing and five of the six indicated hookah smoking was social. Participants identified few (19%) negative associations with hookah use. Moreover, several terms (for example, “buzz”) were described as a more desirable (positive) physical effect than negative. Figure 1 illustrates the number of positive and negative words and phrases identified in each focus group.

Figure 1.

Number of focus groups identifying words as positive and/or negative

Themes and Narratives

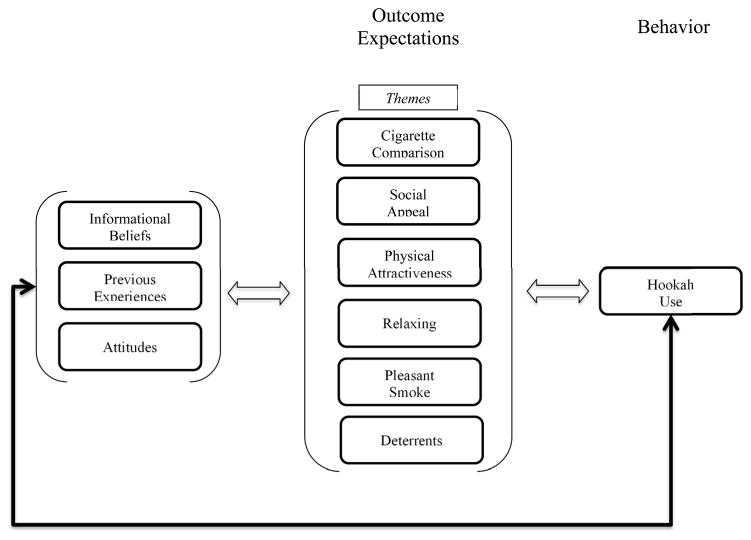

Content analysis of the participant-identified words and focus group transcripts generated 6 overarching themes regarding associations of hookah use. Table 1, including subthemes and supporting quotes, distinguishes between the positive (5) and negative (1) themes in their relation to outcome associations of hookah use. Young adults identified hookah use associations that appeared to be related to individual, interpersonal, and societal dimensions levels of the social-ecological framework (Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, & Zwi, 2002). These dimensions shaped and influenced how and when participants engaged in hookah smoking. Figure 2 illustrates how the outcome expectations identified in the study were related to behavior (hookah use) within the context of outcome expectancy theory.

Table 1.

Focus Group Themes, Subthemes and Example Narratives

| Specific Themes | Example Narrative |

|---|---|

|

Social Appeal Bonding Acceptable |

“Something my friends are doing so that’s why I’m going.” |

| “If my friends are going, I’ll hang out with them, you know like, it’s not really that I necessarily - oh yeah I really want to smoke right now.” | |

| “It is kind of like a bonding activity, people like to bond over it.” | |

| “Like, it’s like acceptable in your social world. Like it’s acceptable.” | |

|

Physical Attractiveness Appealing Attractive |

“But, yeah, so, but I mean, I would also say, I guess maybe, the foreign aura around it gives it a positive, like, appeal.” |

| “Even like aesthetically, like it’s just cooler.” | |

| “There’s a very strong aesthetic appeal to them.” | |

| “I feel like enticing or attractive maybe.” | |

|

Pleasant Smoke Flavors/Taste Tricks |

“Well that’s like, one thing with hookah is, you know, I love it, but you give me like a cigar or something, and I can’t stand it cause it’s hot smoke. It’s like I don’t like the taste of hot smoke, but there is something about the hookah when you get the flavored tobacco and it’s been cooled through the water, it’s smooth.” |

| “I like that you can do tricks and techniques.” | |

| “Yeah, but you have so many… you can have like watermelon. You can mix watermelon and apple.” | |

| “I’m just saying like as a female, there are flavors that I can feel attracted to, but I feel like they’re made for me. That I can do this too.” | |

|

Comparison to Cigarettes Process Access Acceptability Repercussions |

“I feel like it’s less harsh. Like the smoke is less harsh than a cigarette.” |

| “And kind of on another note, the smoke, the smell isn’t as bad as say like smoking a cigar or a cigarette. It definitely doesn’t linger as long or anything like that.” | |

| “I think less unattractive and less offensive than cigarettes.” | |

| “Like, in the sense of like why is somebody smoking hookah, because usually people smoke like cigarettes to calm them down or something, but there’s like a lot of different reasons to smoke hookah.” | |

| “You can buy hookahs in gas stations. Yeah, there’s whole stores that you can, so it’s very popular. Yeah, very accessible, that’s the word.” | |

|

Relaxing Atmosphere Calming Buzz |

“I like the French inhale, certain ways to make the nicotine go straight to your head. Give you like the strong buzz or head rush.” |

| “It’s like a volume, like a great volume of smoke too at one time and that’s what really produces the head high.” | |

| “I’m trying to think of a word for the atmosphere, cause usually it’s like in a really dark, like kind of laid back with music atmosphere.” | |

| “Chill feeling, different feeling, relaxing feeling, it’s a calming feeling, it’s a fun feeling, feeling like you’re doing something special.” | |

|

Deterrents Harm Chemicals |

“Yeah if the coal’s been burning too long and the shisha gets scorched, it’s like it it gets real harsh.” |

| “Once all the tobacco all gets burnt up it’s like you’re just smoking ash. It makes you cough hard.” | |

| “Toxins? I guess just the nicotine even though it’s not up there. Whatever other chemicals that are in the smoke.” |

Note: Unshaded text represent positive outcomes and shaded text represent negative outcomes.

Figure 2.

Conceptual schematic of outcome expectancy theory in context of our hookah use findings.

Participants focused heavily on the Social Appeal of smoking hookah and positively related how it created relationships and ties in an environment where it was accepted. Participants frequently discussed the bonds that can be formed during a session of hookah smoking since it is not an activity one normally does alone, and described that the purpose of group outings revolved around bonding. Additionally, respondents described the behavior as a socially acceptable, legal, nighttime activity to share with friends.

Next, the emerging theme Physical Attractiveness contained words and phrases that were mostly positively associated with smoking hookah. Participants described an aura of appeal, and strong aesthetics tied to hookah use which extended beyond the “cool” factor. Participants described that when you see someone smoking hookah or see pictures of hookah smoking, there is an inherent mystery about the person or character. Additionally, they stressed that hookah smoking would be stigmatized if it were unattractive to do so. Participants reported motivation to engage in hookah smoking in part due to their expectations of what results when others smoke hookah.

Hookah smoking elicited a strong positive association at an individual level based on the ability to personalize it, thus creating a theme around Pleasant Smoke. In most focus groups, specific flavors, taste preferences, and smoke exhale tricks were mentioned. One particular flavor, watermelon, stimulated a discussion on gender and flavor norms:

“As a female in the room, I like that it has more like feminine flavors, like watermelon, mint. So it’s like appealing to a feminine palate. Sorry, if feminine is offensive to any of you guys who appreciate watermelon.”

The ability to add a personal and unique aspect to hookah smoking brought agreement and excitement among participants who detailed their favorite way to blow bubbles or smoke rings.

Other expectancies were mentioned as reasons for smoking hookah as Compared to Cigarettes. In this theme, mostly described through positive beliefs, participants felt that hookah use resulted in smoke and odors that were more preferable and less permanent on them and their clothes compared to cigarettes. Participants discussed the differences in accessing cigarettes and hookah as well as how acceptable hookah use is perceived in public. Other arguments were conflicted with regards to which behavior is healthier. Some focused on hookah not being as negative of a behavior since it is less harsh (referring to inhaling) while others compared hookah use to smoking a pack of cigarettes. They also expressed that smoking cigarettes was often something done because it helped the smoker calm down, however, this particular aspect was not associated with hookah smoking.

Despite negative perceptions about cigarette smoking which participants indicated stemming from a desire to calm down, all focus groups positively identified hookah smoking as Relaxing. It was described by one participant as:

“when your brain gets kind of stimulated but your body gets relaxed. Like it relaxes your muscles, but stimulates your brain.”

A number of participants described symptoms pertaining to relaxing such as ‘head high’ or ‘buzz’ as calming results with positive outcomes. One participant said it was like being “sober fun” in trying to operationalize the ‘head high’ feeling. Many reported a certain feeling pertaining to the ambience or atmosphere of smoking hookah that seemed to heighten the positive expectancies of the behavior and create feelings of comfort. Very few participants had a negative association with these symptoms or feelings.

Lastly, focus group participants discussed chemicals and the potential for harm as negative attributes associated with hookah smoking. Participants listed toxins such as tar, and apprehensions about the coal burning process and water filtration in hookah as potential Deterrents for hookah smokers. Additionally, structural damages as a result of burning coals, along with concerns of minor burns, and breathing in ash were described as adverse effects of engaging in hookah use. Some participants referred to the practice as unhygienic, and harmful, while others used symptoms such as “scratchy cough” or “panic attack.” While many of the themes were predominantly positive with respect to hookah smoking, this last theme encompassed fears that were raised in the focus groups.

DISCUSSION

Users identified many positive associations and few negative associations of hookah use. All of the focus groups indicated hookah smoking was relaxing and five of six referred to it as social, entertaining, fun, smooth, and with good taste. Interestingly, the “buzz” associated with hookah smoking was described in positive terms, but the symptoms themselves (light-headed and head high) may be indications of exposure to large amounts of carbon monoxide (Barnett, Curbow, Soule, Tomar, Thombs, 2011; Shihadeh & Saleh, 2005). In contrast, terms including dizziness and nausea were also mentioned across the focus groups, but were described in more negative terms. Regardless of whether participants identified physiological outcomes of hookah use as positive or negative, they did not seem to understand the potential harmful reasons for these symptoms.

Perceptions that hookah smoking is safer and more appealing than cigarette smoking documented in our findings are consistent with existing quantitative and qualitative literature (Griffiths & Ford, 2014; Rezk-Hanna, Macabasco-O’Connell, & Woo, 2014; Sharma, Clark, Sharp, 2014; Smith-Simone, Maziak, Ward, Eissenberg, 2008). The evidence comparing a typical 45-minute hookah session and cigarettes, indicating hookah use contains 30 times the carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Sepetdjian, Shihadeh, Saliba, 2008), 40 times the tar (Shihadeh & Saleh, 2005), and twice the amount of nicotine (Katurji, Daher, Sheheitli, Saleh, Shihadeh, 2010) compared to smoking a single cigarette is clear. However, throughout the focus groups, it became apparent that many of the participants lacked this knowledge or had misconceptions about aspects of hookah smoking including how the tobacco is heated, ingredients, or potential harm. While it was evident that participants recognized the dangers of cigarette smoking, they did not associate the majority of these dangers with hookah use. Therefore, community-wide or school-based health education programs could be created to promote and reinforce the research findings that dispel such misperceptions.

In addition to common fallacies among young adults relative to the safety of hookah, specifically in comparison to cigarettes, this study found that the variety and availability of flavors present a positive experience for choosing hookah over other forms of tobacco. Though flavors in hookah tobacco are not currently regulated, the FDA will likely have regulatory authority over flavors in hookah tobacco products if the “Deeming Rule” goes into effect. Applying similar or more stringent flavor restrictions than those that are currently applied to cigarettes may have a strong impact on deterring youth and young adults from engaging in hookah use. Future research should focus on the role that policy can play in this important topic and drive instrument development for subsequent quantitative research.

This study also identified some gender differences in the flavor discussions previously unexplored in the literature. Recent trends indicate that while there have been statistically significant decreases in the use of cigarettes among young adults, hookah use has significantly increased and females have reported the same prevalence compared to males (Barnett et al., 2013a). A lack of gender differences in use patterns has also been reported for adolescent populations (Arrazola et al., 2015; Amrock et al 2014). In Florida where the current study was conducted, overall male adolescents reported higher use, but trend analysis indicated females reporting a faster increase in use (Barnett, Forrest, Porter, Curbow, 2014). Future research should explore gender differences in the use of appealing flavors that could potentially drive an increase in female prevalence among adolescents and young adults.

This study had several limitations. The generalizability of the study may be limited due to the convenience sample of hookah smokers from one city. However, the qualitative nature of the study provided rich data that would not have been feasible in a larger study. Although extensive efforts were made to recruit young adults not enrolled in college, the study was conducted in a city with both a large university and community college, thus recruiting efforts resulted in only two focus groups that were not composed of college students. We did, however, reach saturation of themes with the six focus groups. Respondents were also not identified during the focus group or survey phase in an effort to obtain truthful responses by offering anonymity. A limitation of this method includes not being able to link individuals providing responses in the focus groups to their follow-up behavioral differences obtained through the brief survey conducted at the end of the focus group.

Despite these limitations, this study demonstrated a positive user perception with regards to hookah use, similar to quantitative studies of college students (Barnett et al., 2013b). Effective interventions cannot solely focus on the harms of hookah use, but also must target the positive reasons young adults are attracted to this mode of smoking. Users provided many positive outcome expectancy beliefs and detailed descriptions of why these are important for hookah use. Such beliefs can inform targeted interventions and prevention programs, including policy regulations at various levels of the social-ecological model (Krug et al., 2002). At an individual level, participants reflected on knowledge, beliefs, and experiences that highlighted positive features of hookah smoking including “relaxing” and “less offensive than cigarettes.” Interventions at the individual level should focus on the balance between positive and negative attitudes that shape hookah use (Barnett et al., 2013b; Primack et al., 2008; Rezk-Hanna, Macabasco-O’Connell, & Woo, 2014). At an interpersonal level, responses were commensurate with peer influence (Akl et al., 2010; Hammal et al., 2015) and bonding rituals. Discussions in the focus groups centered on Social Appeal made it clear that bonding with friends and Physical Attractiveness played a key role in promoting this behavior. At an interpersonal level, interventions must target the social acceptance and ritualistic bonding associated with hookah use. This concept of social influence is supported by findings from Rezk-Hanna, Macabasco-O’Connell, & Woo (2014). With findings emphasizing bonding and relaxation as key features for hookah use, interventions could build on practical alternative methods in which young adults can meet this need without hookah.

For a broader approach, communities should consider coordinated mobilization programs that can empower young adults to partake in activities fostering positive behaviors that can achieve the same positive feelings as those associated with hookah use. Participants also identified the availability of and ease of access to hookah bars in the community as an enabling factor for use. Communities should consider placing restrictions on the number of venues, hours of operation, and age restrictions in order to decrease exposure. Additionally, exploring the locations of hookah bars and their proximity to schools may provide community level policy intervention that may address and potentially reduce hookah use. At a societal level, flavor regulations must be included in our efforts to address the positive appeal that is driving increased use. Lastly, social norms must be further explored to fully understand the intricate smoking and group identities of this population. This would allow for theory driven and evidenced-based practice public health interventions to decrease the exposure of hookah among young adults.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: National Cancer Institute (grant number R03CA165766) awarded to TEB.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None Declared

Contributor Information

Dr. Tracey Barnett, University of Florida, Epidemiology, 2004 Mowry Rd, PO Box 100231, Gainesville, 32610-0231 United States.

Mr Felix E Lorenzo, University of Florida, Social & Behavioral Sciences Program, 1225 Center Dr, Gainesville, 32611 United States.

Dr. Eric K Soule, Virginia Commonwealth University, Department of Psychology, 1001 E Broad St, Richmond, 23298-0205 United States

References

- Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Irani J. The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: a systematic review. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39(3):834–857. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrock SM, Gordon T, Zelikoff JT, Weitzman M. Hookah use among adolescents in the United States: results of a national survey. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2014;16(2):231–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg B, Bunnell RE, Choiniere CJ, King BA, Cox S, McAfee T, Caraballo RS. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students – United States, 2011–2014. [Last accessed 10.1.2015];Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2015 64(14):381–385. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6414a3.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett TE, Forrest JR, Porter L, Curbow BA. A multiyear assessment of hookah use prevalence among Florida high school students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(3):373–377. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett TE, Smith T, He Y, Soule EK, Curbow BA, Tomar SL, McCarty C. Evidence of emerging hookah use among university students: a cross-sectional comparison between hookah and cigarette use. BMC Public Health. 2013a;13:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett TE, Shensa A, Kim KH, Cook RL, Nuzzo E, Primack BA. The Predictive Utility of Attitudes toward Hookah Tobacco Smoking. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2013b;37(4):433–439. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.4.1. http://dx.doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.37.4.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett TE, Curbow BA, Soule EK, JR, Tomar SL, Thombs DL. Carbon Monoxide Levels among Patrons of Hookah Cafes. American Journal Preventive Medicine. 2011;40(3):324–328. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Juliano LM, Copeland AL. Expectancies for tobacco smoking. In: Kirsch I, editor. How expectancies shape experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 263–299. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Christiansen BA, Goldman MS. The Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire: an instrument for the assessment of adolescent and adult alcohol expectancies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 1987;48(5):483–491. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.483. http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1987.48.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T, Ward KD, Smith-Simone S, Maziak W. Waterpipe tobacco smoking on a U.S. College campus: prevalence and correlates. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(5):526–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Grinberg A, Shapiro J, Keith D, McNeil MP, Taha F, et al. Hookah use among college students: prevalence, drug use, and mental health. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;141:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER, Ayna D. Argileh use among college students in the United States: An emerging trend. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2008;69:472–474. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.472. http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2008.69.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MA, Ford EW. Hookah smoking: behaviors and beliefs among young consumers in the United States. Social Work in Public Health. 2014;29(1):17–26. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2011.619443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammal F, Wild TC, Nykiforuk C, Abdullahi K, Musie D, Finegan BA. Waterpipe (hookah) smoking among youth and women in Canada is new, not traditional. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv152. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, Brandon TH. Smoking expectancy associates among college smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(2):235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour S, El-Roueihab Z, Sibai AM. Nargileh (water-pipe) smoking and incident coronary heart disease: a case- control study. Annals of Epidemioliogy. 2003;13(8):570. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00165-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarret T, Blosnich J, Tworek C, Horn K. Hookah use among U.S. college students: results from the national college health assessment II. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(10):1145–53. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katurji M, Daher N, Sheheitli H, Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Direct measurement of toxicants inhaled by water pipe users in the natural environment using a real-time in situ sampling technique. Inhalation Toxicology. 2010;22(13):1101–1109. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.524265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch I. Self-efficacy and outcome expectancy: A concluding comment. In: Maddux JE, editor. Self-efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment: Theory, research, and application. New York: Plenum; 1995. pp. 331–345. [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neergaard J, Singh P, Job J, Montgomery S. Waterpipe smoking and nicotine exposure: a review of the current evidence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(10):987–994. doi: 10.1080/14622200701591591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal AA, Shadel WG, Donny EC, Eissenberg TE. Prevalence of and Associations with Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking among U.S. University Students. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;36(1):81–86. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Walsh M, Bryce C, Eissenberg T. Water-pipe tobacco smoking among middle and high school students in Arizona. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e282–288. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, Chang L, Hadgu S, Salinas-Miranda AA, Corvin J. Prevalence, knowledge, and practices of hookah smoking among university students, Florida, 2012. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11:E214. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezk-Hanna M, Macabasco-O’Connell A, Woo M. Hookah Smoking Among Young Adults in Southern California. Nursing Research. 2014;63(4):300–306. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepetdjian E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Measurement of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in narghile waterpipe tobacco smoke. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46(5):1582–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma E, Clark PI, Sharp KE. Understanding psychosocial aspects of waterpipe smoking among college students. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2014;38(3):440–447. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.38.3.13. org/10.5993/AJHB.38.3.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, “tar”, and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2005;43(5):655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling KL, Mermelstein R. Examining hookah smoking among a cohort of adolescent ever smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:1202–1209. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(2):393–398. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin EL, McCoy TP, Reboussin BA, Wagoner KG, Spangler J, Wolfson M. Prevalence and correlates of waterpipe tobacco smoking by college students in North Carolina. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115(1–2):131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]