Abstract

We compare the folding transition state (TS) of ubiquitin previously identified by using ψ analysis to that determined by using φ analysis. Both methods attempt to identify interactions and their relative populations at the rate-limiting step for folding. The TS ensemble derived from ψ analysis has an extensive native-like chain topology, with a four-stranded β-sheet network and a portion of the major helix. According to φ analysis, however, the TS is much smaller and more polarized, with only a local helix/hairpin motif. We find that structured regions can have φ values far from unity, the canonical value for such sites, because of structural relaxation of the TS. Consequently, these sites may be incorrectly interpreted as contributing little to the structure of the TS. These results stress the need for caution when interpreting and drawing conclusions from φ analysis alone and highlight the need for more specific tools for examining the structure and energetics of the TS ensemble.

Keywords: multiple pathways, phi analysis, protein folding, transition state

Mutational φ analysis has been a major method for characterizing the structure of transition states (TSs) for protein folding (1, 2) and other reactions (3, 4). In this approach, the energetic effect of an amino acid substitution on the folding-activation energy relative to its effect on equilibrium stability, quantified as φ, is interpreted as the extent to which a mutated residue is involved in the formation of the TS. Values of zero and one are taken to indicate that the influence of the side chain is either absent or fully present, respectively, in the TS.

However, in protein folding studies, interpretational issues arise because most φ values are fractional, generally lying in the range of 0.1–0.5 (5–14). These intermediate values might be due to partial structure formation in the TS or the presence of multiple TS structures. Furthermore, if multiple, alternative TSs exist, a destabilizing mutation will reduce the fraction of states in the ensemble that involve this residue and, thus, generate a lower than expected φ value (8, 14, 15). For example, our earlier work with the GCN4 coiled coil protein found low single-site φ values (16), which turned out to be caused by alternative nucleation positions rather than by the lack of participation by the mutated position (8, 11).

Even in the case of a single pathway, a mutation can shift the location of the TS either through Hammond or anti-Hammond behavior (15). In general, the effects of an amino acid substitution can depend on an indeterminate combination of local, long-range, native, and even nonnative interactions, and secondary structure preferences. As a consequence, the translation of fractional energetic changes into the language of TS structure is difficult. Some of the problems may be addressable with multiple mutations at a given site (12, 15).

The ψ analysis methodology overcomes several of these short-comings by identifying structure and shifts in TS populations upon perturbation (11). In this method, engineered bi-His metal ion binding sites are introduced one at a time at known positions throughout the protein to stabilize secondary and tertiary structures. The addition of increasing concentrations of metal ions stabilizes the interaction between the two known His positions in a continuous way. The effect is measured for both the folding TS and the native protein. A multitude of data points is acquired, which displays in detail the response of the folding rate to the increased stability of known, pairwise interactions. The analysis, thereby, is able to quantitatively evaluate in real thermodynamic terms the shift in the TS ensemble resulting from the metal-induced stabilization of the bi-His site. Finally, the translation of a measured ψ value to structure formation is straightforward because the proximity of two known positions is probed.

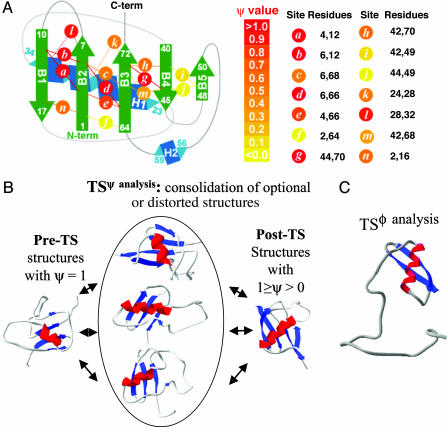

Here we apply φ and ψ analyses to mammalian ubiquitin (Ub) (17), a protein that folds in a two-state manner (18–21). φ values obtained for a set of substitutions in which Ile or Leu core residues are changed to Ala on each of the seven major structural elements, along with those previously obtained for surface residues (14), imply a small, polarized TS. Our previous ψ analysis study (14), however, found a much more extensive TS (Fig. 1). The origins of this discrepancy are discussed.

Fig. 1.

Ub TS identified by using ψ and φ analyses. (A) Schematic representation of ψ values. Bi-His sites are shown (circles with italic letters); each site was studied individually. The color intensity represents the value of ψ.(B) The major folding pathway identified by using ψ analysis (14) is best described with a TS ensemble that emerges from a conserved nucleus. This preTS structure, defined by regions where ψ = 1, either spreads in a number of possible directions reflecting TS heterogeneity, illustrated here with three representative structures, or contains distorted regions with binding affinities less than those in the native structure. The postTS structure is the union of all structures with fractional ψ values. (C) The smaller and polarized TS determined by using φ analysis is based on the present mutational data and earlier studies (14). Renderings were created in swiss-pdb viewer (Glaxo Wellcome).

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Stopped-Flow Measurements. Variants of the pseudowild-type protein Ub F45W (19) were created by using a QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Rapid-mixing fluorescence experiments were performed by using a Biologic SFM-400 stopped-flow apparatus connected by a fiber optic cable to a PTI A101 arc lamp with a 0.8-mm path length (19). Trp fluorescence spectroscopy was performed by using λexcite and λemis of ≈280–290 nm and 300–400 nm, respectively. The denaturant dependence of activation energies (1), with activation free energy of folding, ΔGf, and unfolding, ΔGu, was fit with a linear dependence on denaturant concentration, ΔGf,u([Den]) = –RT ln  , where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature, by using origin software (Mircocal, Amherst, MA).

, where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature, by using origin software (Mircocal, Amherst, MA).

ψ and φ Analyses. Both ψ and φ analyses monitor the change in activation free energy relative to the change in stability, ΔΔGf/ΔΔGeq, as depicted in a Brønsted plot (Fig. 2). In φ analysis, a single point on the Brønsted plot is obtained for any given mutation. The relationship between ΔΔGf and ΔΔGeq is assumed to be linear with the slope, or φ value, representing the fractional energetic contribution of the mutated side chain to a single TS structure (1–4). The φ value is effectively a two-point fit between the wild type and mutant (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of TS heterogeneity. (A) Application of ψ analysis to a two-route scenario, illustrated with a helical site with native binding affinity that is formed on 9% of the pathways before addition of metal. The absent route contains a TS that cannot bind metal without undergoing a conformational transition. The folding rate for the route with the bi-His site present (kpresent, lower pathway) increases from 1 to 100 upon the addition of 2.86 kcal·mol–1 of metal-ion-binding energy at 20°C. This enhancement increases the flux down the metal-ion-stabilized route (divalent metal ion, M2+) relative to all other routes (kabsent), from  , to metal-enhanced condition, ρM2+ = 10/100, where ρ0 is the ratio of rates in the absence of metal ions for pathways in which the bi-His site is formed to those in which the bi-His site is not formed. The corresponding ψ values increase from ψ0 = 0.1 to ψM2+ = 0.9. The binding energy,

, to metal-enhanced condition, ρM2+ = 10/100, where ρ0 is the ratio of rates in the absence of metal ions for pathways in which the bi-His site is formed to those in which the bi-His site is not formed. The corresponding ψ values increase from ψ0 = 0.1 to ψM2+ = 0.9. The binding energy,  , required to stabilize a TS and switch a minor route to a major route identifies the barrier height for this route relative to that for all other routes. (B) In the corresponding Brønsted plot, the fraction of TSs with the site present is the ψ value, which is the instantaneous slope at any given [M2+]. The equations shown are applicable to this situation. Alternatively, when the metal binding affinity in the TS is less than in the native state, the curvature also can be accounted for with a homogeneous TS ensemble with the ψ value at the origin equating to the fraction of the native binding energy realized in TS. (C) Brønsted plot illustrating that, when there is TS heterogeneity, φ values underestimate the relative importance of an interaction. For a completely native-like interaction that is present in only 50% of the TS ensemble (Keq = 1), destabilizing mutations of 0.4, 1.3, and 2.7 kcal·mol–1 reduce Keq to 0.33, 0.09, and 0.01, respectively. The corresponding φ values will be 0.42, 0.26, and 0.15, although the contribution of the residue to the TS of the wild-type protein is φ (0) = 0.5. Hence, the desirability of having large energetic perturbations to generate accurate φ values (27) can be detrimental to correctly assessing the contribution of a residue to the TS ensemble.

, required to stabilize a TS and switch a minor route to a major route identifies the barrier height for this route relative to that for all other routes. (B) In the corresponding Brønsted plot, the fraction of TSs with the site present is the ψ value, which is the instantaneous slope at any given [M2+]. The equations shown are applicable to this situation. Alternatively, when the metal binding affinity in the TS is less than in the native state, the curvature also can be accounted for with a homogeneous TS ensemble with the ψ value at the origin equating to the fraction of the native binding energy realized in TS. (C) Brønsted plot illustrating that, when there is TS heterogeneity, φ values underestimate the relative importance of an interaction. For a completely native-like interaction that is present in only 50% of the TS ensemble (Keq = 1), destabilizing mutations of 0.4, 1.3, and 2.7 kcal·mol–1 reduce Keq to 0.33, 0.09, and 0.01, respectively. The corresponding φ values will be 0.42, 0.26, and 0.15, although the contribution of the residue to the TS of the wild-type protein is φ (0) = 0.5. Hence, the desirability of having large energetic perturbations to generate accurate φ values (27) can be detrimental to correctly assessing the contribution of a residue to the TS ensemble.

ψ analysis uses deliberately placed bi-His sites to probe the fraction of native metal ion binding energy realized in the TS. Data are obtained for each bi-His variant over a range of metal ion concentrations. Thus, for each bi-His variant, a continuous range of values for ΔΔGf and ΔΔGeq is obtained. The Brønsted plot (see Fig. 2) is fit to a model with two parameters, ψ and f. The latter term represents the final slope that is near unity, its theoretical limit at high metal concentrations where the population shift in the TS ensemble saturates. Explicitly, the ψ value is the instantaneous slope at any metal concentration. ψ values are sensitive to the proximity of two known partners and hence directly report on site connectivity. ψ values of zero and unity indicate that either none of the TS ensemble has the binding site present or the entire ensemble has the site formed in a native-like manner, respectively.

When the TS ensemble is heterogeneous or the metal binding affinity of the TS is less than that in the native state, the ψ value will be fractional. The Brønsted plot will curve upward as added metal continuously increases the representation of the particular bi-His site in the TS ensemble. When the metal binding affinity in the TS is native-like, the ψ value obtained at any given metal concentration is the fraction of the TS ensemble that has the two His in a geometry capable of binding metal (Fig. 1). Alternatively, the ψ value at zero metal ion concentration could reflect the fraction of the native binding stabilization realized in a potentially homogeneous TS ensemble.

The heterogeneous scenario was successfully applied to the folding of a dimeric α-helical coiled coil (11), a system known to have multiple nuclei (8). The analysis shown in Fig. 2 quantitatively identified the level of TS heterogeneity determined from multi-site Ala/Gly surface mutations (8). Potentially, binding sites introduced into helices often will have native-like binding affinities in the TS, in which case, fractional ψ values will be due to TS heterogeneity.

Delineation between the heterogeneous and homogeneous scenarios may be achieved through the study of two metal ions that have different coordination geometries. The two ions are likely to manifest the same ψ value only in the case of transition state heterogeneity, because the same fractional binding affinity is unlikely to be realized with both ions. Alternatively, the stability of the TS structure with the site present can be altered by means of mutation (without perturbing the binding site); if the ψ value responds accordingly, as we observed in the coiled coil (11), the heterogeneity model is the more parsimonious.

Metal-to-bi-His binding is in fast on/off equilibrium and stabilizes binding-competent conformations on existing or nascent pathways (14). In addition, ψ values are obtained even in the limit of zero stabilization (slope at the origin), precluding the involvement of entirely new routes. Metal-binding does not induce the bi-His site to form on an otherwise unpopulated pathway.

Although ψ values are a function of metal-binding stabilization, we often refer to ψ0, the value at zero stabilization. In addition, we correct the ψ0 value to obtain ψcorr0, to account for any change in stability because of the bi-His substitution when the heterogeneous model is appropriate (see equation 5 in ref 14).  is the ψ0 value appropriate for the wild-type protein. With this correction, the ψ values for all of the bi-His variants can be combined to construct an accurate representation of the TS ensemble that is appropriate for the wild-type protein before any perturbation because of bi-His substitution or metal binding. For simplicity, we will refer to ψcorr0 as the ψ value in the present work.

is the ψ0 value appropriate for the wild-type protein. With this correction, the ψ values for all of the bi-His variants can be combined to construct an accurate representation of the TS ensemble that is appropriate for the wild-type protein before any perturbation because of bi-His substitution or metal binding. For simplicity, we will refer to ψcorr0 as the ψ value in the present work.

Results

We substituted Ile and Leu core residues with Ala residues at positions on each of the seven major structural elements of Ub: the five β-strands and the α- and 310-helices. These substitutions destabilize the protein by 2.6–4.4 kcal·mol–1 (1 cal = 4.184 J) (Table 1). For most substitutions, the folding and unfolding arms of the chevron are nearly parallel to that of the wild type (Fig. 3), generating denaturant-independent φ values.

Table 1. Mutational φ values.

| Mutant | Location | ΔΔGeq* | ΔGf = -RT In kf | m0 | -mf | φ value* | Side-chain surface burial,† % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13A | B2 | 3.86 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 2.6 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 81 |

| L15A | B1 | 3.72 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 89 |

| H68N | |||||||

| 130A | α-helix | 3.10 ± 0.04 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.41 ± 0.1 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 89 |

| H68N | |||||||

| L43A | B4 | 4.35 ± 0.04 | 1.38 ± 0.02 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 92 |

| H68N | |||||||

| L50A | B5 | 3.19 ± 0.04 | 1.87 ± 0.01 | 2.5 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.0 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 12 |

| H68N | |||||||

| L56A | 310-helix | 3.56 ± 0.04 | 1.53 ± 0.02 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 1.3 ± 0.0 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0 |

| H68N | |||||||

| L67A | B3 | 2.57 ± 0.03 | 1.91 ± 0.01 | 2.5 ± 0.0 | 1.6 ± 0.0 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 74 |

| F45W | pseudowt1 | (7.8 ± 0.1) | 2.25 ± 0.03 | 2.4 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.0 | N/A | N/A |

| H68N | pseudowt2 | (7.5 ± 0.1) | 1.96 ± 0.02 | 2.3 ± 0.0 | 1.4 ± 0.0 | N/A | N/A |

Units are kcal·mol-1 (free energies) or kcal·mol-1·M-1 (m values). All variants contain a F45W substitution to permit folding to be monitored by fluorescence. N/A, not applicable.

Calculated according to ΔΔGeq = ΔΔGf - ΔΔGu, and φ = ΔΔGf/ΔΔGeq, where ΔGf and ΔGu were obtained at 1 M and 4 M guanidinium chloride, respectively, to minimize extrapolation errors. Values in parentheses are the values of ΔG for the pseudowild-type proteins F45W and F45W/H68N, to which the mutants are compared. The H68N mutation was introduced to avoid complications caused by spurious metal ion interactions in the original ψ analysis study.

Fig. 3.

Denaturant dependence of folding rates for Ub. Locations of the mutations in the TSφ analysis and the TSψ analysis, defined by theψ = 1 sites, are shown with Corey–Pauling–Koltun space-filling spheres. All variants contained the F45W substitution to permit folding to be monitored by fluorescence, whereas the H68N mutation was introduced in all but variants I3A and L67A to avoid complications caused by spurious metal-ion interactions in the original ψ analysis study. Experiments were conducted at 20°C, 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and a final protein concentration of 0.2–1 μM. GdmCl, guanidinium chloride.

However, the chevron slopes are noticeably different for variants I15A, I30A, L43A, and L56A, most frequently on the unfolding side. For these versions, the computed φ values depend on denaturant concentration. The most notable variant is L56A, for which the φ value changes sign as its folding arm crosses that of the wild type. At denaturant concentrations below the chevron vertex, |φL56A| < 0.2.

The only locations where φ ≥ 0.5 are on the β1- to β2-hairpin and the α-helix (Table 1). For L67A on the adjoining β3-strand, the φ value is zero. Roder and colleagues (13) measured a value of φVal26Ala ≈ 0.5 for another core mutation on the helix. We previously performed numerous Ala/Gly comparisons at surface positions (14), finding φ values of >0.5 only for sites in the hairpin and helix, whereas the other sites often were ≈0.3 (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These three φ analysis studies produce a picture of a small, polarized TS, containing only the hairpin and helix.

The application of ψ analysis (14) indicated that Ub folds through a much more organized TS ensemble (TSψ analysis). The TSψ analysis has a common nucleus consisting of a partially formed four-stranded sheet network (β1–β4) and the carboxyl terminus of the major helix (Fig. 1B). This TS structure is defined by the bi-His sites with unity ψ values whose interpretation is unequivocal (Table 2). Therefore, the TS identified by ψ analysis is considerably larger than that identified by φ analysis, the critical issue for the present discussion.

Furthermore, ψ values for sites around the common nucleus indicate that additional structure exists the TS ensemble. These surrounding regions are either differentially populated according to their relative stability or distorted, with their binding sites having affinities weaker than those in the native state. These optional or distorted structures surrounding the obligatory core possess ψ values that range from 0.26 to 0.75. Their formation serves to consolidate the sheet network and helical structure.

Noncanonical φ Values in Structured and Unstructured Regions. The highest φ values, 0.49–0.54, are for I3A, L15A, and I30A, located in the amino-terminal β-hairpin and α-helix. These residues are buried in the TS identified by both φ and ψ analyses. We estimate that the side chains of these three residues are ≈80–90% buried in TSψ analysis, based on solvent accessibility in our model of TSψ analysis (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Despite this burial level, their φ values deviate significantly from unity.

The deviation from unity is most pronounced for the L67A substitution on strand β3. The side chain of L67 is estimated to be 74% buried in the TSψ analysis. Additionally, the four bi-His sites located on either side of L67 have ψ values ranging from 0.3–1 (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the φ value for L67A is 0.02 ± 0.01.

Residues 50 and 56 are located in regions that are unstructured in the TSψ analysis and have φ values of 0.12 and 0.20, respectively. Their nonzero φ values imply that they participate in the TS to some degree, potentially making a few nonnative hydrophobic interactions. Hence, residues found to be both structured and unstructured by TSψ analysis can have similar φ values.

Discussion

The minimal TS structure for Ub identified with ψ analysis solely by the ψ = 1 sites contains a four-stranded β-sheet network along with a partially formed helix. This structure was not identified by using φ analysis. One may consider that aggressive core mutations with large ΔΔGeq may have favored the identification of a polarized TS. However, Fersht and Sato (15) point out that large perturbations would tend to have the opposite effect, which further emphasizes the identification of a polarized TS.

Part of the discrepancy between the two methods arises from the interpretation of fractional φ values. We observed 0 ≤ φ < 0.6 for core residues that are buried in the TSψ analysis. These results indicate that φ values can appear to be much less than unity even for well buried residues, even when the backbone is in an otherwise native context.

High ψ values for bi-His sites may indicate structure formation in the core, but they do not mandate that hydrophobic core residues have a native-like conformation. The low φ values for residues buried in TSψ analysis probably indicate that the tertiary contacts are not rigid, even when backbone positions are established. For the Leu/Ile→Ala substitutions, the flexible TS may well relax to accommodate the void caused by the loss of methyl groups in a way that is not available to the more constrained native state. As a result of the TS relaxation, the energetic penalty of the Ala substitution can be ameliorated at the rate-limiting step. Hence, the folding rate is largely unchanged, even though the substitution is highly destabilizing in the native state. The small φ values for L43A and L67A and the higher values for I3A, L15A, and I30A suggest that such an adjustment can be better accomplished for substitutions on the periphery of the sheet as opposed to those buried in the more ordered parts of the TS structure.

The ability of the TS to relax to accommodate mutations is supported by other observations. A Ub mutant with a seven simultaneous core mutations loses only 1.2 kcal·mol–1 (22). Mutations in apomyoglobin regularly give smaller changes in ΔGeq for the pH 4 intermediate than for native apomyoglobin (23). Small, energetic effects were found for mutations in highly structured regions of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor equilibrium intermediates (10). The physical properties of TSs are likely to be close to that of equilibrium molten globule intermediates. In addition, nonnative packing has been observed in a folding intermediate of a four-helix bundle (24), indicating structural relaxation to minimize free energy. These and our results suggest that the magnitude of φ values can greatly underestimate the native-like character of a residue in the TS.

Another source of uncertainty arises when φ values, which reflect energetic perturbations, are used to describe the structure of the TS. Only in a few cases does a clear correspondence between the φ value and structure formation exist, for example, in the Ala to Gly mutations on the surface of a helix (14) or in exposed turns that form specific interactions (25). In other circumstances, converting energetic changes into structure is difficult. This issue is further complicated by the possibility of nonnative interactions, which can generate nonzero φ values for what should otherwise be unstructured residues. Nevertheless, a recent study of the three-strand Pin WW domain probing hydrogen bond formation (site-resolved amide to ester changes) did observe qualitative agreement between mutational φ values (26).

Effects of TS Heterogeneity on φ Values. φ values will also be lower than appropriate for interactions that are present in only a subpopulation of the TS ensemble (Fig. 2C). Upon destabilization, the relative influence of such interactions is reduced. This situation will apply to residues that lose only a portion of their interactions yet still participate in the TS, as well as those residues that lose all their interactions and become fully unstructured. In both cases, the measured φ value will be lower than expected because they both reflect the postmutation condition for which the importance of the interaction is reduced.

This effect is exacerbated by the desirability of having large energetic perturbations to generate accurate φ values (27) and may contribute to the low values observed for L67A and L43A. In the wild-type protein, these residues could make contact with the fractionally populated amino terminus of the α-helix located across the core. Such contacts would be reduced after the ≥2.6 kcal·mol–1 destabilization resulting from the Ala substitutions.

In principle, a φ value could be corrected for the magnitude of the mutation's destabilization. However, implementation is challenging because it requires knowledge of the limiting φ value for the condition where the interaction is present in the entire TS ensemble. For most residues, this value cannot be predicted. For example, we found that φ values generally are far below unity even for well buried residues in the TS nucleus. Hence, correcting observed φ values for the destabilizing effect of a mutation is difficult.

This obstacle might be overcome by studying an appropriate series of mutations. For this strategy to be successful, each mutation must affect the stability of the TS in a similar manner. Otherwise, the φ values would not be constant across the data set. This criterion may be difficult to achieve because most residues are chemically and sterically dissimilar (15). This dissimilarity results in φ values at a given site being quite disparate when different pairs of residues are compared, even for surface substitutions (e.g., φF4A = 0.24 and φA4G = 1.00). Therefore, it may be very difficult to obtain a suitable mutational data set with enough high-quality data points to evaluate by using the ψ analysis formalism.

Even so, a constant φE24 = 0.32 was observed for over a dozen substitutions at a turn position in Src homology 3 (12). Despite these mutations spanning a stability range of 4 kcal·mol–1, a linear Brønsted plot was observed. This linearity indicates a uniform 32% interaction in the TS and not pathway heterogeneity. This result is unexpected because the E24 side chain is involved in electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonds. It seems unlikely that the same fractional interaction can be maintained across the whole library of chemically distinct substitutions, although no reasonable alternative is apparent.

Other Considerations. For Ub, general considerations support the validity of the TS determined by using ψ analysis compared with that determined by using φ analysis. The amount of long-range structure in TSφ analysis appears inconsistent with the known correlation between relative contact order (COrel) of the native state and the logarithm of kf (28). The only structure in the polarized TSφ analysis, the local helix-hairpin motif, does not constrain the chain to adopt the topology of the native state. This insufficiency is reflected in the COrel of TSφ analysis being only ≈30% of the native value. In contrast, the topology of the TSψ analysis ensemble is quite native-like, with a COrel that is ≈80% of the native value. The correlation between the native state's COrel and the logarithm of kfold, which can only reflect properties of the TS, can be rationalized by the topology of the TS resembling that of the native state. Because TSψ analysis has a native-like topology and COrel, whereas TSφ analysis does not, the TSψ analysis is more consistent with the COrel correlation.

The TS determined by using ψ analysis is also more consistent in terms of the amount of surface burial in the TS, estimated from the denaturant dependence, mf/mo = 65%. In the polarized TSφ analysis, the number of structured residues is only ≈40% of the total, and the TS is localized to the amino terminus. Although no simple translation of structure to a denaturant m value exists, a linear correlation between the number of residues and the m values has been observed for numerous proteins (29). By using this linear estimate, the m value of TSφ analysis is lower than the amount observed in the TS (40% versus 65%). In the TSψ analysis ensemble, the essential nucleus is composed of about half of the total number of residues. When combined with some of the optional or distorted structures having fractional ψ values, the aggregate number is close to the measured level of surface burial in the TS.

Calculating ψ Values from Simulations. When the binding site is native-like in the TS, the ψ value is the fraction of the TS ensemble in which the two residues composing the bi-His site have simultaneously adopted a native geometry. This fraction can be obtained from the folding behavior of the wild-type protein alone, because ψ values are extrapolated to the limit of no added stability and they have been corrected for the effects of the introduction of the bi-His site. Consequently, ψ values can be calculated simultaneously for all sites on the protein.

This option to calculate ψ values requires that the TS ensemble be identified. This task may be challenging because the ensemble can depend on the choice of reaction coordinate (30, 31). Simulations that follow folding trajectories can avoid this problem by calculating folding rates after stabilizing conformations where the two residues of interest are in a native geometry. The resulting change in folding rate as a function of stabilization can be directly compared with the experimental data on the Brønsted plot. Although this strategy avoids the need to identify the TS ensemble, it does require that accurate folding rates be determined for multiple conditions and for each bi-His site separately, which may become computationally challenging.

The metal-induced stabilization can be mimicked without incorporating a bi-His site per se. One can add an energetic benefit whenever both residues have adopted a native geometry. For simulations that use the equations of motion, a differentiable energy term is required. A possible implementation is to add a harmonic potential, for example, between the carbonyl oxygen and either the amide proton or nitrogen if the two residues are hydrogen-bonded to each other.

Conclusion

The net consequence of (i) fractional interactions, (ii) relaxation of the TS to accommodate a mutation, (iii) TS heterogeneity, (iv) the loss of interactions upon mutation, and (v) nonnative interactions is that most φ values will cluster in the range 0.1–0.5 rather than taking on the canonical values of zero and one. In particular, a highly structured region can have φ values far from unity. These values can even be smaller than values resulting from nonnative interactions. Furthermore, inferring structure from φ values, which reflect energetic effects, is difficult. For Ub, these issues resulted in the identification of a small, polarized TS. This identification is inconsistent with the much more organized TS ensemble identified by using ψ analysis, even when based solely on ψ = 1 values.

In general, the use of φ values to identify a TS structure is problematic. Therefore, the classification of a TS in other proteins as polarized, diffuse, or expanded based on φ values alone should be reevaluated. To this end, it would be very desirable if a method were developed that could characterize the rigidity and packing of core residues in the TS just as the bi-His strategy identifies chain connectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. W. Englander, A. R. Fersht, D. Goldenberg, Y. Bai, N. Kallenbach, R. L. Baldwin, L. Mayne, V. Pande, S. Jackson, and members of our group for helpful discussions. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions: T.R.S., R.S.D., and B.A.K. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: TS, transition state; Ub, mammalian ubiquitin.

See Commentary on page 17327.

References

- 1.Matthews, C. R. (1987) Methods Enzymol. 154, 498–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fersht, A. R., Matouschek, A. & Serrano, L. (1992) J. Mol. Biol. 224, 771–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fersht, A. R., Leatherbarrow, R. J. & Wells, T. N. C. (1986) Nature 322, 284–286. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leatherbarrow, R. J., Fersht, A. R. & Winter, G. (1985) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 7840–7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fersht, A. R., Itzhaki, L. S., ElMasry, N. F., Matthews, J. M. & Otzen, D. E. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10426–10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, D. E., Yi, Q., Gladwin, S. T., Goldberg, J. M. & Baker, D. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 284, 807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez, J. C., Pisabarro, M. T. & Serrano, L. (1998) Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moran, L. B., Schneider, J. P., Kentsis, A., Reddy, G. A. & Sosnick, T. R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 10699–10704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozkan, S. B., Bahar, I. & Dill, K. A. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulaj, G. & Goldenberg, D. P. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 326–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krantz, B. A. & Sosnick, T. R. (2001) Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 1042–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Northey, J. G., Maxwell, K. L. & Davidson, A. R. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 320, 389–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khorasanizadeh, S., Peters, I. D. & Roder, H. (1996) Nat. Struct. Biol. 3, 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krantz, B. A., Dothager, R. S. & Sosnick, T. R. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 337, 463–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fersht, A. R. & Sato, S. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 7976–7981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sosnick, T. R., Jackson, S., Wilk, R. M., Englander, S. W. & DeGrado, W. F. (1996) Proteins 24, 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vijay-Kumar, S., Bugg, C. E., Wilkinson, K. D., Vierstra, R. D., Hatfield, P. M. & Cook, W. J. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 6396–6399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacob, J., Krantz, B., Dothager, R. S., Thiyagarajan, P. & Sosnick, T. R. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 338, 369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krantz, B. A. & Sosnick, T. R. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 11696–11701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Went, H. M., Benitez-Cardoza, C. G. & Jackson, S. E. (2004) FEBS Lett. 567, 333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krantz, B. A., Mayne, L., Rumbley, J., Englander, S. W. & Sosnick, T. R. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 324, 359–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benitez-Cardoza, C. G., Stott, K., Hirshberg, M., Went, H. M., Woolfson, D. N. & Jackson, S. E. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 5195–5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kay, M. S. & Baldwin, R. L. (1996) Nat. Struct. Biol. 3, 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng, H., Takei, J., Lipsitz, R., Tjandra, N. & Bai, Y. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 12461–12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCallister, E. L., Alm, E. & Baker, D. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deechongkit, S., Nguyen, H., Powers, E. T., Dawson, P. E., Gruebele, M. & Kelly, J. W. (2004) Nature 430, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez, I. E. & Kiefhaber, T. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 334, 1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plaxco, K. W., Simons, K. T. & Baker, D. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 277, 985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers, J. K., Pace, C. N. & Scholtz, J. M. (1995) Protein Sci. 4, 2138–2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding, F., Dokholyan, N. V., Buldyrev, S. V., Stanley, H. E. & Shakhnovich, E. I. (2002) Biophys. J. 83, 3525–3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shea, J. E., Onuchic, J. N. & Brooks, C. L., III (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16064–16068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraczkiewicz, R. & Braun, W. (1998) J. Comp. Chem. 19, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.