Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the independent and combined associations of maternal self-reported poor sleep quality and antepartum depression with suicidal ideation during the third trimester

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 1,298 pregnant women (between 24 and 28 gestational weeks) attending prenatal clinics in Lima, Peru. Antepartum depression and suicidal ideation were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire was used to assess sleep quality. Multivariate logistical regression procedures were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) after adjusting for putative confounders.

Results

Approximately, 17% of women were classified as having poor sleep quality (defined using the recommended criteria of PSQI global score of >5 vs. ≤5). Further, the prevalence of antepartum depression and suicidal ideation were 10.3% and 8.5%, respectively in this cohort. After adjusting for confounders including depression, poor sleep quality was associated with a 2.81-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (OR=2.81; 95% CI 1.78–4.45). When assessed as a continuous variable, each 1-unit increase in the global PSQI score resulted in a 28% increase in odds for suicidal ideation, even after adjusting for depression (OR=1.28; 95% CI 1.15–1.41). The odds of suicidal ideation was particularly high among depressed women with poor sleep quality (OR=13.56 95% CI 7.53–24.41) as compared with women without either risk factor.

Limitations

This cross-sectional study utilized self-reported data. Causality cannot be inferred, and results may not be fully generalizable.

Conclusion

Poor sleep quality, even after adjusting for depression, is associated with antepartum suicidal ideation. Our findings support the need to explore sleep-focused interventions for pregnant women.

Keywords: suicide, sleep, pregnancy, depression, Peru

INTRODUCTION

Suicidal behaviors are the leading causes of injury and death during pregnancy and postpartum (Lindahl et al., 2005; Oates, 2003) in some countries. During pregnancy, suicidal ideation is more common than suicidal attempts or deaths, with 5%–14% of women reporting suicidal thoughts (Lindahl et al., 2005). Suicidal ideation is often considered as a key predictor of later suicide attempt and completion and presents an opportunity for intervention prior to self-harm (Nock et al., 2008). Prior investigators have examined risk factors for suicidal ideation (Gelaye et al., 2016). These include history of abuse, sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric comorbidities, gender norms, family dynamics, and cultural differences (Gelaye et al., 2016). There is an accumulating body of literature implicating sleep disturbances such as nightmares, insomnia, and poor sleep quality as important risk factors for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and death by suicide (Ağargün et al., 1997a, b; Bernert et al., 2005; Fawcett et al., 1990; Goldstein et al., 2008; Krakow et al., 2000).

Pregnancy is characterized by multiple hormonal and anatomical changes, often leading to sleep disturbances (Dzaja et al., 2005; Facco et al., 2010; Hedman et al., 2002; Pien and Schwab, 2004). However, to date, we are aware of one study (Gelaye et al., 2015) that assessed self-reported sleep quality and suicide ideation among pregnant women during the first trimester. Given (1) this gap in the literature, and (2) that sleep complaints are more pronounced in late pregnancy, we sought to examine the associations of self-reported poor sleep quality and antepartum depression with suicidal ideation in pregnant women during the third trimester.

METHODS

Study Population

This study was conducted using a cohort of pregnant women enrolled in the Screening, Treatment and Effective Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (STEM-GDM) study, between February 2013 and June 2014. STEM-GDM is a prospective cohort study aimed at evaluating the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) using the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IAPSG) diagnostic criteria (Wendland et al., 2012). The cohort consisted of pregnant Peruvian women attending perinatal care at Instituto Nacional Materno Perinatal (INMP), the primary referral hospital for maternal and perinatal care in Lima Peru. Women were eligible if they were between 24 and 28 weeks gestation, were 18 years of age or older, spoke and read Spanish, and planned to deliver at INMP. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. The Institutional Review Boards of the INMP, Lima, Peru and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Office of Human Research Administration, Boston, MA, USA granted approval for the research protocol used in this study.

Analytical Population

The study population is derived from information collected from participants who enrolled in the STEM-GDM study. A total of 1,774 eligible women were approached and 1,299 (73%) agreed to participate. After excluding 1 participant with missing information on the PHQ-9 questionnaire, the final analyzed sample included 1,298 participants.

Assessment of Sleep Quality

The PSQI is a 19-item self-administered survey designed for the subjective evaluation of sleep quality and disturbances in clinical populations over the past month (Buysse et al., 1989). The 19 items are categorized into seven clinically derived components including (1) sleep duration, (2) disturbances during sleep, (3) sleep latency, (4) dysfunction during the day due to sleepiness, (5) efficiency of sleep, (6) overall sleep quality and (7) need medication to sleep. Each component score is weighted equally from 0–3 and then summed to obtain a global score ranging from 0 to 21. Higher global scores indicate poorer sleep quality. A distinction between good and poor sleep is based on a global PSQI score >5, which yields 89.6% sensitivity and 86.5% specificity (Buysse et al., 1989). Among pregnant Peruvian women, the Spanish-language version of the PSQI instrument has been found to have good construct validity (Zhong et al., 2015b).

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptomatology during pregnancy was evaluated using the eight-item depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) which includes all items from the PHQ-9 except for suicidal ideation. The PHQ-9 has been demonstrated to be a reliable tool for assessing depressive disorders among a diverse group of obstetrics-gynecology patients (Spitzer et al., 1999) and in Spanish-speaking women (Wulsin et al., 2002; Zhong et al., 2015a). The questionnaire evaluates depressive symptoms experienced by participants in the two weeks preceding the evaluation on a four-point scale a) never; b) several days; c) more than half the days; or d) nearly every day. The first 8 questions were used to calculate an overall depression score. Participants with PHQ-8 score ≥10 were categorized as showing depression, similar to the cutoff for the PHQ-9.

Suicidal Ideation

Suicidal ideation was evaluated based on participants’ response to question 9 of the PHQ-9 (thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way) in the 2 weeks prior to evaluation. Participants who responded with “several days,” “more than half the days,” or “nearly every day,” were classified as “yes” for suicidal ideation. Participants who responded “not at all” were classified as “no” for suicidal ideation.

Other Covariates

Participants completed a structured interview that collected detailed information on maternal sociodemographic characteristics, reproductive and medical histories, as well as lifestyle characteristics. Participants’ age was categorized as: 18–20, 20–29, 30–34 and ≥35 years. Other variables included maternal race (Mestizo vs. others), years of education (≤ 6, 7–12, and >12 years), marital status (married or living with partner vs. others), employment status (yes vs. no), difficulty accessing basic foods (hard vs. not very hard), parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous), planned current pregnancy (yes vs. no), smoke during pregnancy (yes vs. no), alcohol use during pregnancy (yes vs. no), gestational age at interview, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), BMI at interview, and self-reported health in the last year (good vs. poor).

Statistical Analysis

We first examined participants’ maternal sociodemographic, lifestyle, behavioral and reproductive characteristics according to suicidal ideation. Student’s t tests or Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test were used to determine differences in distributions for continuous variables, and Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) for suicidal ideation in relation to maternal reports of sleep quality and antepartum depression. To assess confounding, we entered covariates into each model one at a time and compared adjusted and unadjusted ORs. Final models included covariates that altered unadjusted ORs by at least 10% and those that were identified a priori as potential confounders. To determine the independent and joint effects of poor sleep quality and antepartum depression on suicidal ideation, we categorized participants as: (1) good sleep quality and no depression, (2) good sleep quality and depression, (3) poor sleep quality with no depression and (4) poor sleep quality with depression. Participants with good sleep quality and no depression were the reference group against which women in the other categories were compared. Additionally, we evaluated the odds of suicide ideation across tertiles of PSQI global scores, where tertiles were defined based on the distribution of the PSQI scores of the entire cohort. Linear trends in odds of suicide ideation were evaluated by modeling the three tertiles as a continuous variable after allocating scores of 1, 2 and 3 for sequentially higher tertiles. We next modeled PSQI global scores as a continuous variable to evaluate linear trends in risk of suicide ideation. Finally, we explored the possibility of a nonlinear relationship of PSQI global score with suicidal ideation by fitting a multivariable logistic regression model that implemented the generalized additive modeling (GAM) procedures with a cubic spline function. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM SPSS v22.0. Chicago, IL). The GAM analyses were performed using “R” software version 3.1.2. All reported p-values are two tailed and deemed statistically significant at α=0.05.

RESULTS

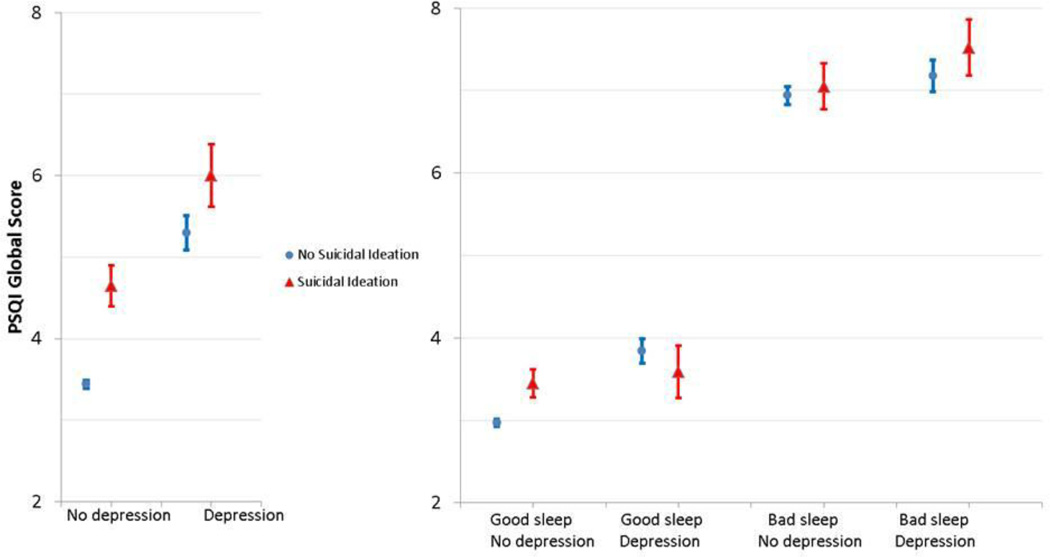

The sociodemographic and reproductive characteristic of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The cohort included 1,298 pregnant women ranging in age between 18 and 45 (mean = 28.9 ± 6.1 years) with an average gestational age of 25.6 (SD= 1.2) weeks at interview. Overall, the majority of the participants were Mestizo (98.1%), married or living with a partner (86.4%), and had 7–12 years of education (53.7%). Approximately, half of the participants reported difficulty accessing basic foods (49.3%) and poor self-reported health during pregnancy (47.7%). The prevalence of antepartum depression was 10.3% and the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 8.5% in this cohort (Table 1). Further, 16.9% of the cohort was classified as having poor sleep quality (defined using the recommended criteria of PSQI global score of >5 vs. ≤5) (Supplemental Table 1). The mean self-reported PSQI global score according to sleep quality and stratified by antepartum depression and suicidal ideation is presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Reproductive Characteristics of the Study Population

| Suicidal Ideation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (N= 1,298) |

No (N = 1,188) |

Yes (N = 110) |

|||||||

| Characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % | P value c |

||

| Age (years) a | 28.9 ± 6.1 | 28.9 ± 6.1 | 28.9 ± 6.4 | 0.95 | |||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 18–19 | 49 | 3.8 | 44 | 3.7 | 5 | 4.6 | 0.54 | ||

| 20–29 | 669 | 51.5 | 618 | 52.0 | 51 | 46.4 | |||

| 30–34 | 311 | 24.0 | 279 | 23.5 | 32 | 29.1 | |||

| ≥35 | 269 | 20.7 | 247 | 20.8 | 22 | 20.0 | |||

| Education (years)a | 12.2 ± 2.4 | 12.2 ± 2.4 | 11.6 ± 2.4 | 0.004 | |||||

| Education (years) | |||||||||

| ≤6 | 39 | 3.0 | 34 | 2.9 | 5 | 4.6 | |||

| 7–12 | 697 | 53.7 | 623 | 52.4 | 74 | 67.3 | 0.003 | ||

| >12 | 562 | 43.3 | 531 | 44.7 | 31 | 28.2 | |||

| Mestizo (race) | 0.29 | ||||||||

| Mestizo | 1273 | 98.1 | 1167 | 98.2 | 106 | 96.4 | |||

| Other | 25 | 1.9 | 21 | 1.8 | 4 | 3.6 | |||

| Marital Status | 0.16 | ||||||||

| Married/living with a partner |

1121 | 86.4 | 1032 | 86.9 | 89 | 80.9 | |||

| Single/Divorced | 176 | 13.6 | 155 | 13.1 | 21 | 19.1 | |||

| Employed | 0.17 | ||||||||

| No | 879 | 67.7 | 798 | 67.2 | 81 | 73.6 | |||

| Yes | 419 | 32.3 | 390 | 32.8 | 29 | 26.4 | |||

| Access to basic foods | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Hard | 640 | 49.3 | 574 | 48.3 | 66 | 60.0 | |||

| Not very hard | 658 | 50.7 | 614 | 51.7 | 44 | 40.0 | |||

| Nulliparous | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Nulliparous | 424 | 32.7 | 398 | 33.5 | 26 | 23.6 | |||

| Multiparous | 874 | 67.3 | 790 | 66.5 | 84 | 76.4 | |||

| Planned pregnancy | 0.006 | ||||||||

| No | 710 | 54.7 | 636 | 53.5 | 74 | 67.3 | |||

| Yes | 588 | 45.3 | 552 | 46.5 | 36 | 32.7 | |||

| Smoke during pregnancy |

0.92 | ||||||||

| No | 1285 | 99.0 | 1176 | 99.0 | 109 | 99.1 | |||

| Yes | 13 | 1.0 | 12 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.9 | |||

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 0.09 | ||||||||

| No | 1261 | 97.1 | 1157 | 97.4 | 104 | 94.5 | 0.54 | ||

| Yes | 37 | 2.9 | 31 | 2.6 | 6 | 5.5 | |||

| Gestational age at interviewa |

25.6 ± 1.2 | 25.5 ± 1.2 | 25.7 ± 1.3 | 0.24 | |||||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) |

25.2 ± 4.0 | 25.2 ± 3.9 | 25.6 ± 4.2 | 0.34 | |||||

| BMI at interview (kg/m2) |

27.7 ± 3.8 | 27.7 ± 3.8 | 27.9 ± 4.3 | 0.52 | |||||

| Self-reported health (last year) | |||||||||

| Good | 860 | 66.3 | 805 | 67.8 | 55 | 50.0 | <0.001 | ||

| Poor | 438 | 33.7 | 383 | 32.2 | 55 | 50.0 | |||

| Self-reported health status

during pregnancy |

|||||||||

| Good | 679 | 52.3 | 644 | 54.2 | 35 | 31.8 | <0.001 | ||

| Poor | 619 | 47.7 | 544 | 45.8 | 75 | 68.2 | |||

| Antepartum depressionb | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 1165 | 89.8 | 1099 | 92.5 | 66 | 60.0 | |||

| Yes | 133 | 10.2 | 89 | 7.5 | 40 | 40.0 | |||

Due to missing data, percentages may not add up to 100%.

Abbreviations: PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; BMI, Body Mass Index

: Mean ± SD (standard deviation)

: Antepartum depression was defined as the PHQ-8 score ≥ 10.

: For continuous variables, P-value calculated using Student's t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test; for categorical variables, P-value was calculated using Chi-square test or Fisher exact test.

Figure 1.

Mean (with standard error bars) self-reported Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score according to Sleep Quality a, Antepartum Depression Status b, and Suicidal Ideation (N = 1,298)

a: Good sleep quality was defined as the PSQI global score ≤5; poor sleep quality was defined as the PSQI global score >5.

b: No depression was defined as the Patient Health Questionnare-8 (PHQ-8) score < 10; antepartum depression was defined as the PHQ- 8 score ≥ 10.

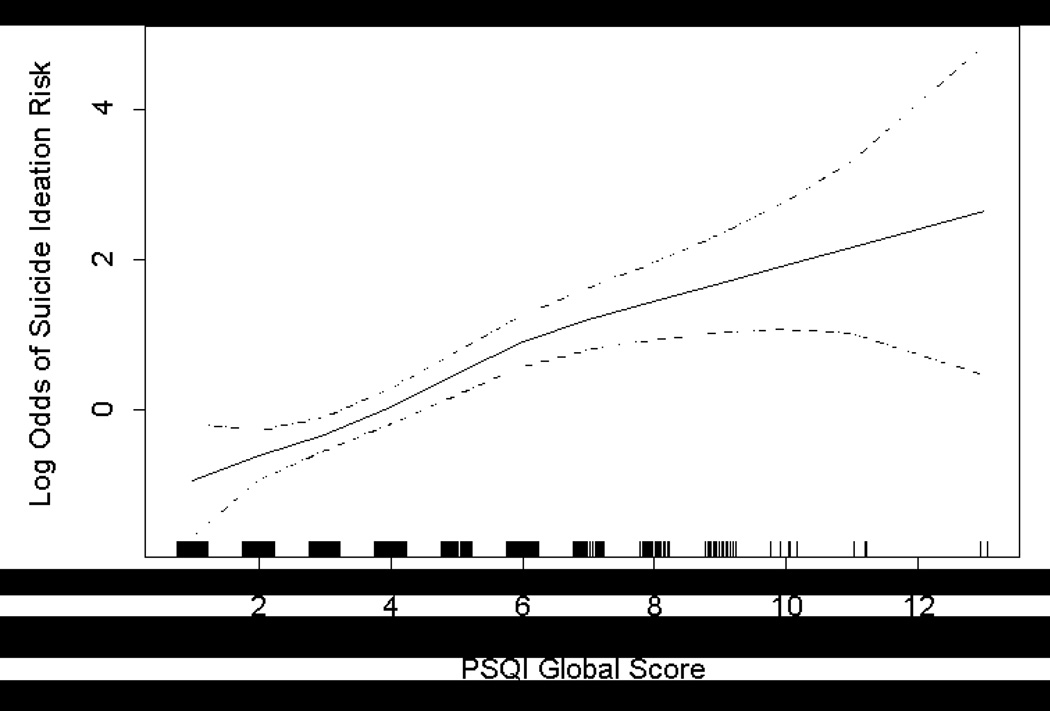

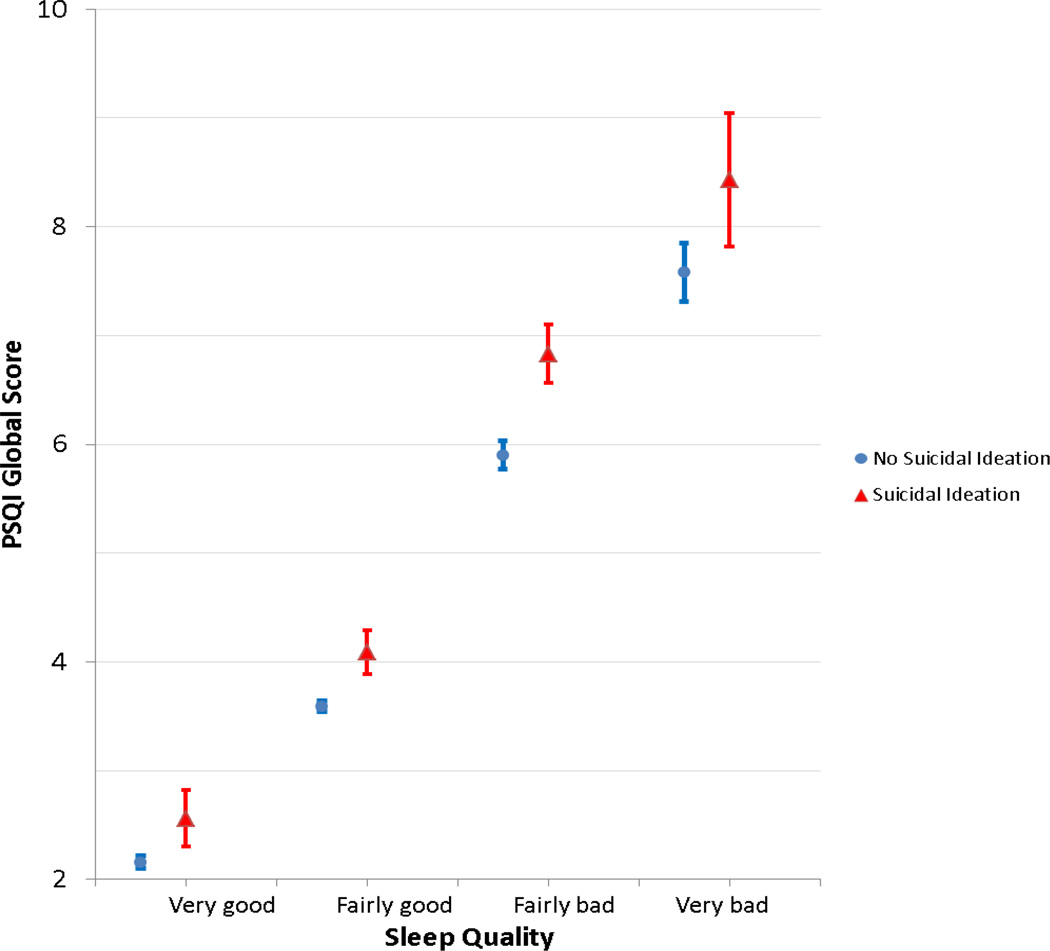

Participants with poor sleep quality had a more than 4-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (OR = 4.81; 95% CI 3.19–7.24) (Table 2). After adjusting for confounders including age, parity, access to basics, education, and unplanned pregnancy, there was a 4.47-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR = 4.47; 95% CI 2.94–6.78). Further adjustment for depression resulted in an attenuation of the association, namely after adjusting for depression, participants with poor sleep quality had 2.8-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation as compared with their counterparts who had good sleep quality (aOR = 2.81; 95%CI: 1.78–4.45) (Table 2). We also evaluated the odds of suicidal ideation across tertiles of PSQI global score. After adjustment for confounders including depression, women in the middle tertile (PSQI global score 3–5) had 1.25-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR = 1.25; 95% CI 0.66–2.37) and women in the highest tertile had 2.82-fold increased odds (aOR = 2.82; 95% CI 1.51–5.27) when compared to those in the lowest tertile (PSQI global score ≤2) (Table 2). When assessed as a continuous variable, every 1-unit increase in the global PSQI score resulted in a 28% increase in odds for suicidal ideation (aOR = 1.28; 95% CI 1.15–1.41) suggesting a linear association in PSQI global scores and the odds of suicide ideation (Table 2; Figure 2). Reports of self-rated perceived sleep quality were largely consistent with PSQI-derived global scores (Figure 3). Participants with suicidal ideation had the highest mean PSQI global scores compared with those without suicidal ideation.

Table 2.

Model Statistic for Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score Associated with Suicidal Ideation (N=1,298)

| PSQI global score | PHQ-9 Suicidal Ideation | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusteda OR (95% CI) |

Adjustedb OR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 1,188) |

Yes (N = 110) |

||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Overall sleep quality | |||||||

| Good (PSQI global score ≤5) | 1018 | 85.7 | 61 | 55.5 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Poor (PSQI global score > 5) | 170 | 14.3 | 49 | 44.5 | 4.81 (3.19–7.24) | 4.47 (2.94–6.78) | 2.81 (1.78–4.45) |

| PSQI global score | |||||||

| Lowest tertile (0–2) | 368 | 31.0 | 15 | 13.6 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Middle tertile (3–4) | 522 | 43.9 | 32 | 29.1 | 1.50 (0.80–2.82) | 1.41 (0.75–2.66) | 1.25 (0.66–2.37) |

| Highest tertile (≥5) | 298 | 25.1 | 63 | 57.3 | 5.19 (2.89–9.30) | 4.63 (2.57–8.35) | 2.82 (1.51–5.27) |

| P-value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| PSQI global score (continuous)c | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 2.3 | 1.42 (1.30, 1.56) | 1.41 (1.29, 1.54) | 1.28 (1.15, 1.41) | ||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

: Adjusted for age (years), parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous), access to basics (hard vs. not very hard), education (years) and unplanned pregnancy.

: Further adjusted for antepartum depression status (yes [PHQ-8 ≥ 10] vs. no [PHQ-8 < 10])

: Mean ± SD (standard deviation)

Figure 2.

Relation between Self-reported Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score and Risk of Suicidal Ideation (solid line) with 95% Confidence Interval (dotted lines). Vertical bars along PSQI axis indicate distribution of study subjects. Model was adjusted for maternal age, parity, access to basics, education and unplanned pregnancy.

Figure 3.

Mean (with standard error bars) Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Global Score by “Sleep Quality” Component (N=1,298)

Lastly, we explored the independent and joint effect of depression on sleep quality with the odds of suicide ideation through multivariate analyses (Table 3). In a fully adjusted model, women with depression and good sleep quality had increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR = 7.28; 95% CI 3.86–13.75), compared with women who had good sleep quality and no depression (i.e., the referent group). Women with poor sleep quality and no depression had a 3.50-fold increased odds of suicidal ideation compared to the referent group (aOR = 3.50; 95% CI 2.02–6.06). Women with poor sleep quality and depression had an increased odds suicidal ideation (aOR = 13.56, 95% CI 7.53–24.41), although the interaction term did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.18).

Table 3.

Associations between Sleep Quality, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation (N=1298)

| Sleep quality a and depressive symptomsb | Suicidal ideation | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjustedc OR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 1,188) | Yes (N = 110) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Good sleep quality, no depression | 968 | 81.5 | 44 | 40.0 | Reference | Reference |

| Good sleep quality, depression | 50 | 4.2 | 17 | 15.5 | 7.48 (3.99–14.01) | 7.28 (3.86–13.75) |

| Poor sleep quality, no depression | 131 | 11.0 | 22 | 20.0 | 3.69 (2.15–6.36) | 3.50 (2.02–6.06) |

| Poor sleep quality, depression | 39 | 3.3 | 27 | 24.5 | 15.23 (8.56–27.10) | 13.56 (7.53–24.41) |

| P-value for multiplicative interaction | 0.20 | 0.18 | ||||

: Good sleep quality was defined as the PSQI global score ≤5; poor sleep quality was defined as the PSQI global score >5.

: No depression was defined as the Patient Health Questionnare-8 (PHQ-8) score < 10; depression was defined as the PHQ - 8 score ≥ 10.

: Adjusted for age (years), parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous), access to basics (hard vs. not very hard), education (years), and unplanned pregnancy; odds ratio was calculated by including an interaction term between sleep quality and antepartum depression in the model.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 8.5% in the cohort, while poor sleep quality was reported by 16.9% of women. After adjusting for confounders including antepartum depression, women with poor sleep quality had increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR = 2.81; 95% CI 1.78–4.45) compared to those with good sleep quality. When we assessed the PSQI global score as a continuous variable, we found that the odds of suicidal ideation increased by 28% per each unit increase in PSQI global score (aOR = 1.28; 95% CI 1.15–1.41). We also found that women who reported both poor sleep quality and depression had an increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR = 13.6; 95% CI 7.53–24.41) compared to their counterparts with neither risk factor.

Previous studies have examined sleep quality and suicidal ideation in men and non-pregnant women. In a study among 51 men and women outpatients with chronic pain, those suffering from sleep onset insomnia were found to more likely to report suicide ideation and depressive symptoms (p<0.03) as compared with without sleep onset insomnia (Smith et al., 2004). Similarly, among adolescents from high-risk alcoholic families participating in a community based study in the US, sleep disturbances were reported to be associated with suicidal ideation (p < 0.05) (Wong et al., 2011). To our knowledge, there is one study that evaluated sleep quality in relation to suicidal ideation during pregnancy (Gelaye et al., 2015). In an earlier and different cohort study of pregnant Peruvian women receiving antepartum care during their first trimester, we reported that women with poor subjective sleep quality (PSQI>5) had 1.67-increased odds of suicidal ideation (aOR = 1.67; 95% CI 1.02–2.71) compared with women who had good sleep quality (PSQI<5), after adjusting for confounders including depression. Furthermore, women with poor subjective sleep quality and depression had a 3.48-increased odds of suicidal ideation after adjusting for confounders (aOR = 3.48; 95% CI: 1.96–6.18) (Gelaye et al., 2015). Hence, the present study of pregnant Peruvian women (interviewed in late pregnancy) yield associations that are largely consistent with our earlier study. Although antepartum depression is highly associated with suicidal ideation; only a proportion of participants endorsing suicidal ideation experience the co-occurrence of antepartum depression (Zhong, 2015). As such our findings showing increased risk of suicidal ideation in those with poor sleep quality in the absence of antepartum depression confirms that sleep disturbances are an important independent risk factor for suicidal ideation. In sum, available evidence indicates the need for monitoring sleep quality among pregnant women.

Observed associations of poor sleep quality with suicide ideation are biologically plausible. Poor sleep quality may contribute to changes in cognitive and emotional processes, leading to behavioral changes characterized as more irritable and emotionally labile. Changes in these emotional and cognitive processes may also pose an increased risk for suicidal behaviors (Dombrovski et al., 2008; Keilp et al., 2013; Walker, 2009). Sleep loss during pregnancy has been shown to result in increases in proinflammatory cytokines including interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Okun et al., 2007). Elevations in proinflammatory cytokines promote the release of prostaglandins which are known to trigger the onset of labor leading to an increased risk in preterm delivery (Klebanoff et al., 1990). Chronic systemic inflammation secondary to sleep disturbances, poor sleep quality and sleep loss may also contribute to alterations in neurochemical signaling pathways and the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis that may play a role in the pathogenesis of depression and suicidality (Chang et al., 2010).

There are some limitations in our study that should be considered. First, the use of a cross-sectional design in the present study does not allow us to establish causality among suicidal ideation, depression, and poor sleep quality. Second, the use of self-reported questionnaires could lead to underreporting of sensitive or stigmatized behaviors, including suicidal ideation and depression. Third, the use of a single item to measure active and passive suicidal ideation may exclude important components of suicidal ideation (Lindahl et al., 2005). Fourth, the study also has the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured factors. Additional covariates such as frequent nightmares and clinically relevant insomnia could influence sleep quality and suicidal ideation. Additional studies should incorporate the use of longitudinal study design which includes an assessment of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviors over a lifetime or in recurrent episodes as well as simultaneous measurements of chronic and acute depression. Despite these limitations, our study had a number of strengths including our sample size, use of qualified interviewers, and adjustment for several confounders in our analysis.

The findings of the present study indicate the need for careful monitoring pregnant women’s suicidal behavior and depressive symptoms especially among those with poor sleep quality. Replication of our study findings in other populations and further exploration of underlying biological mechanisms of observed associations are warranted. Future studies should also further explore intervention programs that ensure healthy support mechanisms in the final weeks of pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

This is the first reported study to assess the independent relationship between sleep quality and suicidal ideation in late pregnancy

Poor sleep quality, even after adjusting for depression, is associated with antepartum suicidal ideation.

Our findings indicate the need for careful monitoring pregnant women’s suicidal behavior and depressive symptoms especially among those with poor sleep quality.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ağargün M, Kara H, Solmaz M. Sleep disturbances and suicidal behavior in patients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997a;58:249–251. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ağargün M, Kara H, Solmaz M, et al. Subjective sleep quality and suicidality in patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 1997b;31:377–381. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(96)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernert R, Jr, T J, Cukrowicz K, Schmidt N, Krakow B. Suicidality and sleep disturbances. Sleep. 2005;28:1135–1141. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse D, 3rd, C R, Monk T, Berman S, Kupfer D. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JJ, Pien GW, Duntley SP, Macones GA. Sleep deprivation during pregnancy and maternal and fetal outcomes: is there a relationship? Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Houck PR, Clark L, Mazumdar S, Szanto K. Cognitive performance in suicidal depressed elderly: preliminary report. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:109–115. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180f6338d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzaja A, Arber S, Hislop J, Kerkhofs M, Kopp C, Pollmacher T, Polo-Kantola P, Skene DJ, Stenuit P, Tobler I, Porkka-Heiskanen T. Women's sleep in health and disease. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:55–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facco F, Kramer J, Ho K, Zee P, Grobman W. Sleep Disturbances in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:77–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c4f8ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett J, Scheftner W, Fogg L, Clark D, Young M, Hedeker D, Gibbons R. Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelaye B, Barrios YV, Zhong QY, Rondon MB, Borba CP, Sanchez SE, Henderson DC, Williams MA. Association of poor subjective sleep quality with suicidal ideation among pregnant Peruvian women. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2015;37:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelaye B, Kajeepeta S, Williams M. Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: an epidemiologic review. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2016 Jun 21; doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0646-0. 2016 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Bridge JA, Brent DA. Sleep disturbance preceding completed suicide in adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:84–91. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman C, Pohjasvaara T, Tolonen U, Suhonen-Malm A, Myllylä V. Effects of pregnancy on mothers' sleep. Sleep Medicine. 2002;3:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(01)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Russell M, Oquendo MA, Burke AK, Harkavy-Friedman J, Mann JJ. Neuropsychological function and suicidal behavior: attention control, memory and executive dysfunction in suicide attempt. Psychol Med. 2013;43:539–551. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff M, Shiono P, Rhoads G. Outcomes of pregnancy in a national sample of resident physicians. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323:1040–1045. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010113231506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakow B, Artar A, Warner T, Melendrez D, Johnston L, Hollifield M, Germain A, Koss M. Sleep Disorder, depression, and suicidality in female sexual assault survivors. Crisis. 2000;21:163–170. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.21.4.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock M, Borges G, Bromet E, Cha C, Kessler R, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. British Medical Bulletin. 2003;67:219–229. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun ML, Hall M, Coussons-Read ME. Sleep disturbances increase interleukin-6 production during pregnancy: Implications for pregnancy complications. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:560–567. doi: 10.1177/1933719107307647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pien G, Schwab R. Sleep disorders during pregnancy. Sleep. 2004;27:1405–1417. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Perlis M, Haythornthwaite J. Suicidal ideation in outpatients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: An exploratory study of the role of sleep onset insomnia and pain intensity. 2004;20:2. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MP. The role of sleep in cognition and emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1156:168–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendland EM, Torloni MR, Falavigna M, Trujillo J, Dode MA, Campos MA, Duncan BB, Schmidt MI. Gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcomes--a systematic review of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) diagnostic criteria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Brower KJ, Zucker RA. Sleep problems, suicidal ideation, and self-harm behaviors in adolescence. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulsin L, Somoza E, Heck J. The feasibility of using the Spanish PHQ-9 to screen for depression in primary care in Honduras. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;4:191–195. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v04n0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Sanchez SE, Simon GE, Henderson DC, Barrios YV, Sanchez PM, Williams MA. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to assess suicidal ideation among pregnant women in Lima, Peru. Archives of Women's Mental Health. 2015a;18:783–792. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong QY, Gelaye B, Sanchez SE, Williams MA. Psychometric properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) in a cohort of Peruvian pregnant women. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015b;11:869–877. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.