Abstract

When lipid membranes containing ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acyl chains are subjected to oxidative stress, one of the reaction products is 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) – a chemically reactive short chain alkenal that can covalently modify proteins. The ubiquitin proteasome system is involved in the clearing of proteins modified by oxidation products such as HNE, but the chemical structure, stability and function of ubiquitin may be impaired by HNE modification. To evaluate this possibility, the susceptibility of ubiquitin to modification by HNE has been characterized over a range of concentrations where ubiquitin forms non-covalent oligomers. Results indicate that HNE modifies ubiquitin at only two of the many possible sites, and that HNE modification at these two sites alters the ubiquitin oligomerization equilibrium. These results suggest that any role ubiquitin may have in clearing proteins damaged by oxidative stress may itself be impaired by oxidative lipid degradation products.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, oxidative stress, tandem mass spectrometry, photocrosslinking, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, ubiquitin

INTRODUCTION

Ubiquitination of a protein, i.e. the covalent addition of one or more ubiquitin (Ub) units to the protein, initiates a sequence of events that lead to the degradation of the protein via the proteasome.1 Because of the importance of this mechanism in cell homeostasis, Ub is highly conserved throughout the eukaryotes, and the ubiquitination process is tightly regulated.2 One of the well-known regulatory mechanisms is the location of the covalent bond between Ub molecules on a polyubiquitinated protein. Depending on the site of the linkage, di- and poly(Ub)s exhibit distinct quaternary structures and linkage-specific functions such as endocytosis and DNA repair (linked to Lys-63),3 or proteosomal degradation (linked to Lys-11 and Lys-48).4 However, it has also been observed that Ub can dimerize noncovalently at physiological concentrations, and noncovalent oligomers may have significant regulatory roles.5,6

Disruption of the proteasome mediated degradation system is linked to debilitating pathological conditions.7 For example, a mutated ubiquitin (UBB+1) accumulates in Alzheimer’s disease (AD)8 where it co-localizes with amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.9 Another prominent pathological process in AD is oxidative stress,10 which has the potential to disrupt protein function by producing reactive lipid degradation products such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE).11 HNE is derived from ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acyl chains, which are common in the triglycerides and phospholipids present in cell membranes. HNE can spontaneously modify amino acid side chains, disrupting protein function12 and/or accelerating protein degradation within cells.13 HNE is known to modify Ub,14,15 and these modifications have been associated with AD.16 However, the sites of HNE modifications of Ub are unclear, and they have not thus far been correlated to its oligomeric state.

In this work, the modification of Ub by HNE has been characterized by a mass spectrometric approach, along with the effects of modification on the non-covalent oligomerization of Ub. Results indicate that HNE only reacts with two amino acidic residues of naturally folded Ub, and that HNE modification at these sites inhibits the concentration-dependent non-covalent oligomerization of Ub. They suggest that Ub function may be altered by the same processes (HNE modification) that make other proteins targets for ubiquitination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) and 4-hydroxy hexenal (HHE) in ethanol were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) and stored as a stock solution at −80 °C under argon. Prior to use, ethanol in the HNE or HHE stock solution was removed by argon flow and HNE or HHE was solubilized in the buffer. Guanidine-HCl Solution 8M was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. In order to monitor the HNE modification to unfolded Ub, Guanidine-HCl solution was added (final concentration 6M) to the Ub solution prior trypsin digestion. Trypsin Ultra-Mass Spectrometric Grade in trypsin buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 20mM CaCl2, pH 8.0), was purchased from Biolab, New England. Ub was purchased from Abcam. Bradykinin (Bk) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

For kinetics measurements, reagents were added (final volume 100 µl) to a vial immersed in ice in the following order: HNE or HHE from evaporated ethanol (final concentration 400 µM), HEPES buffer, and finally Ub (40 µM final concentration in HEPES 30 mM). After collecting the first aliquot (10 µl) of the sample (time 0), it was incubated at 37°C. Samples were collected at the time points specified, and the reaction was stopped by adding HCl to the collected aliquots. Finally, bradykinin was added to a final concentration of 40 µM as an internal standard and samples were stored at −20°C prior to analysis. For digestions with trypsin, 5 µl of 1µg/µl trypsin was mixed with 15 µl of 2X trypsin buffer and 10 µl of Ub at the concentrations specified. When HNE was present, unreacted HNE was removed by threefold extraction with hexane before the digestion with trypsin.

Chromatographic separations were performed with solvents A (0.01% TFA in water) and B (0.01% TFA in acetonitrile) on a Zorbax-SB C18 (1.0×150mm, 3.5µm particle size) column, at a flow rate of 100µl min–1. The LC gradient was: 0 – 35 min / 1 – 90% B; 35 – 40 min / 90% B; 40 – 45 min / 90 – 100% B. Mass spectrometric measurements were carried out on a 4000 QTrap LC/MS/MS System (Applied Biosystem, MDS SCIEX). Injection volumes were 3 µl, declustering potential was 75V and a collision energy of 30V was used. Uncharged Ub with a formula of C378H629N105O118S1 has a monoisotopic (all 12C) mass of M = 8559.6 Da and a most prevalent mass of M* = 8563.6 due to natural abundance 13C. The most abundant ion has a +7 charge, so that [M*+7H]+7 = 1224.4. A multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) method was developed with the transitions listed in table 1.

Table 1.

MRM transitions (masses corrected for natural abundance 13C)

| MRM transition | (Parention) → (Production) | CE (volts) |

|---|---|---|

| 1224.4 → 1307.1 | (Ub7+) → | 55 |

| 1246.7 → 1338.3 | (Ub · HNE7+) → (y58 · HNE5+) | 57 |

| 1269.0 → 1266.4 | (Ub · HNE27+) → (Ub · HNE2 – H2O7+) | 32 |

| 530.8 → 175.1 | (Bk2+) → Arg+ | 40 |

Photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified proteins (PICUP) was performed according to published methods.17–19 In this application, 1 µL of 1 mM (Ru(byp)3)Cl2 and 1 µL of 20 mM APS in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4 were added to 0.5 nmol of Ub in HEPES 30 mM. The volumes of the various Ub solutions at each concentration were adjusted to keep the amount of Ub constant. The mixture was illuminated for 1 s using a shuttered 150W xenon lamp. The mixture was immediately quenched with 10 µL of Tricine sample buffer (Invitrogen) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Cross-linked mixtures were fractionated without boiling by SDS-PAGE using 10–20% Tricine gels (1.0 mm X 10 wells, Invitrogen) and silver-stained using a Silver-Xpress kit (Invitrogen).

RESULTS

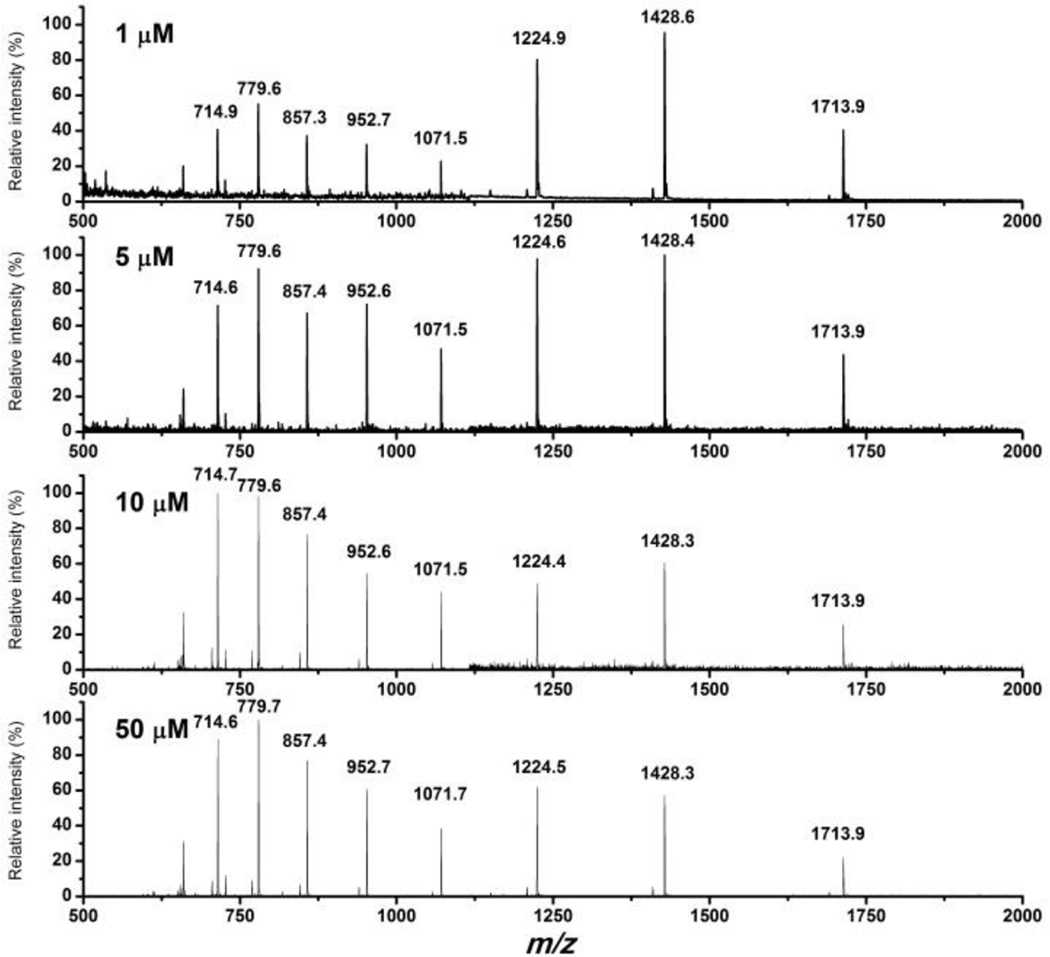

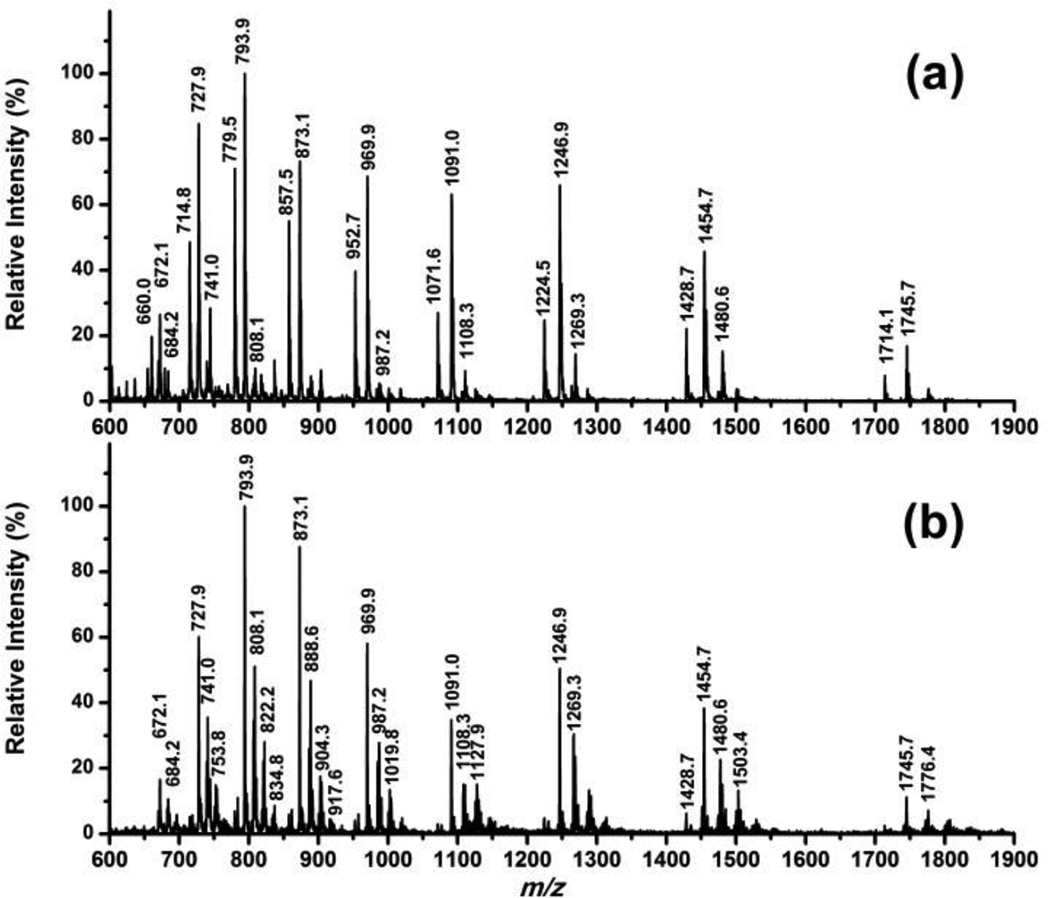

ESI mass spectra for Ub at various concentrations are shown in figure 1, and expected masses are listed in table 2. The pattern of multi-charged ion intensities varied in a manner that was reproducible: higher Ub concentrations (> 5 µM) always yielded lower relative signal intensities for lower charge states (experiments run in triplicate). When Ub was treated with HNE as described in the previous section, a different mass spectrum was recorded (figure 2). Indeed, mass increases suggested that one or two HNE modifications had occurred, with only trace signals from protein with three modifications (figure 2a). In contrast, when the protein is treated with guanidine prior to HNE modification (figure 2b), signals due to Ub with three or more HNE modifications were abundant in the mass spectrum indicating that some potential HNE modification sites were protected by the protein fold.

Figure 1.

+ve ESI mass spectra for Ub solution at the indicated concentrations.

Table 2.

Ub m/z ratios for various charge states and modifications

| Species | Unmodified | + HNE | + 2 HNE | + 3 HNE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [M + H]+1 | 8560.6 | 8715.6 | 8871.6 | 9027.6 |

| [M + 2H]+2 | 4280.8 | 8716.6 | 8872.6 | 9028.6 |

| [M + 3H]+3 | 2854.2 | 4358.8 | 4436.8 | 4514.8 |

| [M + 4H]+4 | 2140.9 | 2906.2 | 2958.2 | 3010.2 |

| [M + 5H]+5 | 1712.9 | 2179.9 | 2218.9 | 2257.9 |

| [M + 6H]+6 | 1427.6 | 1744.1 | 1775.3 | 1806.5 |

| [M + 7H]+7 | 1223.8 | 1453.6 | 1479.6 | 1505.6 |

| [M + 8H]+8 | 1071.0 | 1246.1 | 1268.4 | 1290.7 |

| [M + 9H]+9 | 952.1 | 1090.5 | 1110.0 | 1129.5 |

| [M + 10H]+10 | 857.0 | 969.4 | 986.7 | 1004.1 |

| [M + 11H]+11 | 779.1 | 872.6 | 888.2 | 903.8 |

| [M + 12H]+12 | 714.3 | 793.3 | 807.5 | 821.7 |

| [M + 13H]+13 | 659.4 | 671.4 | 683.4 | 695.4 |

Figure 2.

+ve ESI mass spectra for Ub solution 100µM after incubation with HNE 400 µM for 24 h in HEPES buffer without (a) and with (b) the addition of Guanidine-HCl Solution (final concentration 6M).

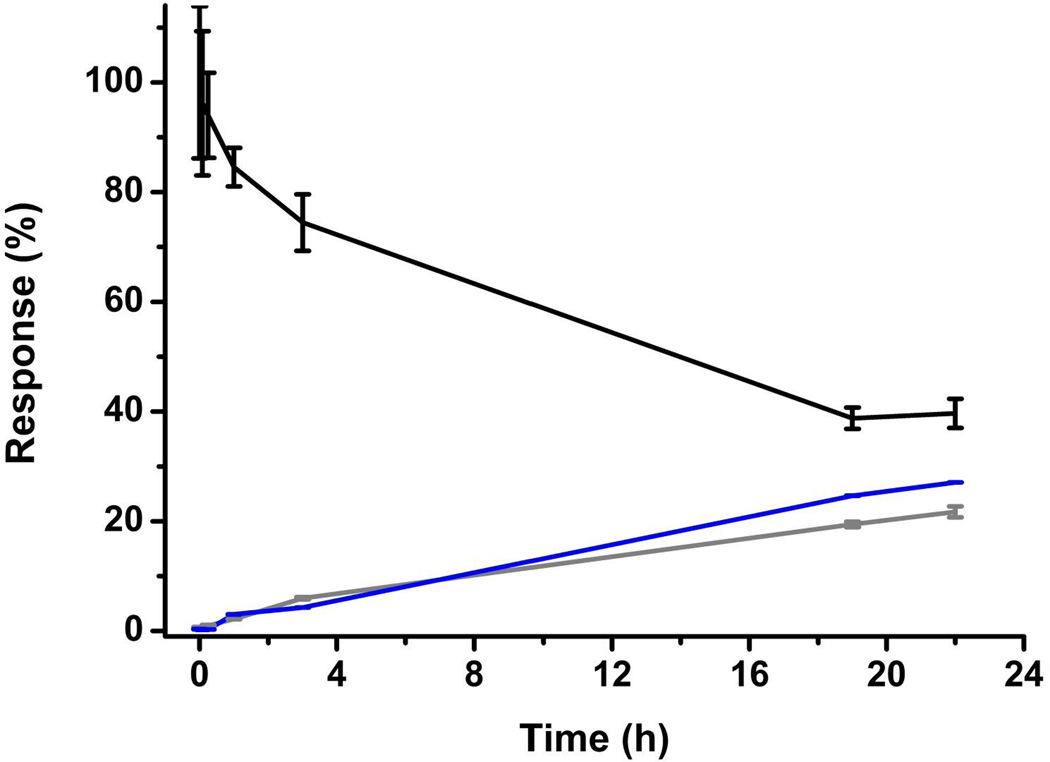

An MRM method was developed to quantify the extent of HNE modification over time, using bradykinin as an internal standard. Under the conditions described in the methods section, the reactions were largely complete by 24 h (figure 3). All subsequent experiments were performed with “HNE treatment” referring to a 24 h treatment under these conditions.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of HNE (400 µM) addition to Ub (40 µM) in HEPES as measured by MRM/MS. The ratio between the Ub, Ub·HNE1 and Ub·HNE2 peaks, respectively black, blue and grey and spiked bradykinin was monitored as a function of reaction time. Error bars have been calculated from the standard deviations obtained from 3 different measurements.

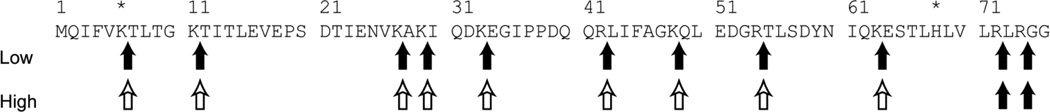

The treatment of Ub at concentrations < 5µM (concentrations 1µM, 2µM, 3µM and 4µM were tested) with trypsin yielded all expected fragments with no missed cleavage sites (table 3, figure 4). In contrast, trypsin digestion to solutions of Ub at concentrations ≥ 5µM (Ub concentrations 5µM, 10µM, 50µM and 100µM were tested) yielded fragments from only two expected cleavage sites (table 4 and figure 4). HNE treatment of Ub at concentrations < 15µM (Ub concentrations 5µM, 10µM, 14µM were tested) prior to digestion restored the trypsin cleavages in the middle portion of the molecule, producing the same mass spectrum as in the case of unmodified Ub with concentrations < 5µM. However, for Ub concentrations ≥ 15µM (Ub concentrations 15µM, 50µM, and 100µM were tested) the missed cleavages were observed even after HNE treatment. Sequencing mass spectrometry indicated that only Lys-6 and His-68 were modified by HNE when Ub ≥ 15µM (figure 1S and 2S).

Table 3.

Trypsin fragments identified in the mass spectra of Ub solutions ≤ 5 µM. HNE-modified fragments in bold in the lower portion of the table were detected when Ub ≤ 15 µM was HNE-treated.

| Unmodified fragments | Experimental (m/z) |

Calculated monoisotopic (m/z) |

|---|---|---|

| LR+H+ | 288.2 | 288.2 |

| MQIFVK+2H+ | 383.2 | 383.2 |

| MQIFVKTLTGK+3H+ | 422.6 | 422.6 |

| IQDK+H+ | 503.2 | 503.3 |

| TLTGK+H+ | 519.2 | 519.3 |

| EGIPPDQQR+2H+ | 520.2 | 520.3 |

| ESTLHLVLR+2H+ | 534.2 | 534.3 |

| TLSDYNIQK+3H+ | 541.2 | 541.3 |

| MQIFVKTLTGK+2H+ | 634.2 | 633.4 |

| LIFAGK+H+ | 648.3 | 648.4 |

| AKIQDK+H+ | 703.3 | 702.4 |

| QLEDGR+H+ | 717.3 | 717.3 |

| MQIFVK+H+ | 765.4 | 765.4 |

| TITLEVEPSDTIENVK+2H+ | 894.4 | 894.5 |

| EGIPPDQQR+H+ | 1039.4 | 1039.5 |

| ESTLHLVLR+H+ | 1067.5 | 1067.6 |

| TLSDYNIQK+H+ | 1081.4 | 1081.5 |

| TITLEVEPSDTIENVK+H+ | 1788.9 | 1787.9 |

| Peptide fragments only observed with HNE modification |

||

|---|---|---|

| MQIFVK+HNE+2H+ | 461.8 | 462.3 |

| ESTLHLVLR+HNE+2H+ | 612.8 | 613.4 |

| ESTLHLVLR+HNE+H+ | 1225.7 | 1225.8 |

Figure 4.

Ub sequence showing consistent trypsin cleavage sites (solid arrows) and inconsistent cleavage sites (open arrows). Asterisks indicate sites of HNE modification. Low: Ub ≤ 5 µM or Ub ≤ 15 µM + HNE. High: Ub > 15 µM.

Table 4.

Tryptic fragments with missed cleavages identified in the mass spectra of Ub solutions > 5 µM. HNE-modified fragments in the lower portion of the table were detected when Ub > 15 µM was HNE-treated.

| Unmodified fragments | Observed peaks (m/z) | Deconvoluted mass | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPDQQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKESTLHLVLR | 683.0 769.6 879.4 |

1023.4 1230.5 |

6147.9 |

| MQIFVKTLTGKTITLEVEPSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPDQQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKES TLHLVLR |

630.6 682.8 744.9 819.2 910.0 |

1023.4 1169.6 1364.3 1637.0 2046.0 |

8180.8 |

| MQIFVKTLTGKTITLEVEPSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPDQQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKES TLHLVLRLR |

705.4 769.4 845.9 |

939.9 1057.4 1208.1 |

8450.6 |

| Peptide fragments only observed with HNE modification | Observed peaks (m/z) | Deconvoluted mass | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MQIFVKTLTGKTITLEVEPSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPDQQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKES TLHLVLR + HNE |

696.0 759.2 834.9 927.4 |

1043.1 1192.0 1390.3 1668.2 |

8338.8 |

| MQIFVKTLTGKTITLEVEPSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPDQQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKES TLHLVLR + 2HNE |

773.4 850.5 944.8 |

1062.8 1214.1 1416.5 |

8496.8 |

| MQIFVKTLTGKTITLEVEPSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPDQQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKES TLHLVLRLR + HNE |

663.4 718.4 783.5 861.8 957.4 |

1076.6 1230.5 1435.5 1722.3 |

8608.6 |

| MQIFVKTLTGKTITLEVEPSDTIENVKAKIQDKEGIPPDQQRLIFAGKQLEDGRTLSDYNIQKES TLHLVLRLR + 2HNE |

675.1 731.4 797.7 877.2 |

974.4 1096.4 1252.9 |

8766.6 |

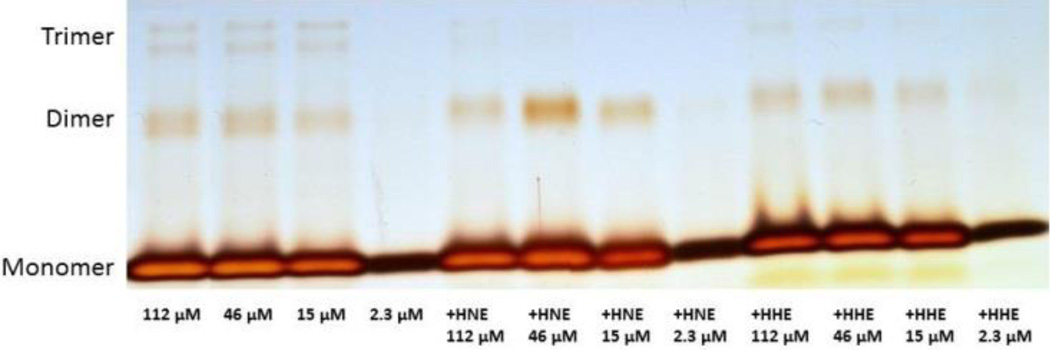

The basis for missed cleavages at Ub concentrations ≥ 5µM, but not at concentrations < 5µM, was explored with photochemical crosslinking. Results indicate that only monomeric Ub was observed at 2.8 µM, but dimeric and trimeric forms were present at concentrations between 15 – 112 µM (figure 5). HNE modification hindered the formation of trimeric species at all concentrations examined, although the dimeric form is still detected at similar relative amounts to the monomer. When the same experiment was performed with HHE instead of HNE, trimeric forms of Ub at high concentrations persisted, although they were less abundant.

Figure 5.

SDS-PAGE using 10–20% Tricine gels and silver-stained. Oligomeric species detected for Ub solutions at the indicated conditions. Splitting of the bands is likely due to alternative crosslink structures. The more intense monomeric and dimeric bands in the sixth line are due to sample overload. Experiment was performed in duplicate.

DISCUSSION

ESI/MS revealed that the relative intensity of signals of Ub arising from various charge states varied with the solution concentration: higher Ub concentrations (> 5 µM) yielded lower signals for lower charge states. It is impossible to draw conclusions about protein structure and/or oligomerization states from data so capricious as the relative signal strengths from various charge states. However, this result prompted us to investigate if Ub solutions at different concentrations in the µM range could have different oligomerization states,5 and if MS was a suitable analytical approach for such purpose. Indeed, the observed empirical relationship between concentration and charge state may not have been observed previously because the amounts involved are close to the detection limits of common mass spectrometers (i.e. 10−12 mol). However, these concentrations are in the range expected in mammalian cells3 and therefore, concentration-dependent phenomena may be physiologically significant.

To investigate a possible correlation between Ub concentrations and protein oligomerization by MS, Ub at various concentrations were treated with trypsin and resulting solutions were analysed by MS. At Ub concentrations ≥ 5µM, trypsin efficiently cleaved only at the N- and C-terminals. Cleavage sites in the middle portion of the Ub sequence were protected. Missed cleavages have been reported previously in the case of polyUb,20 suggesting that the missed cleavages we observed may be due to oligomer formation at higher concentrations of Ub. There were no missed cleavages at concentrations < 5 µM, whereas most cleavages were missed at concentrations ≥ 5 µM. Clearly, there was a concentration-dependent phenomenon protecting most of the cleavage sites.

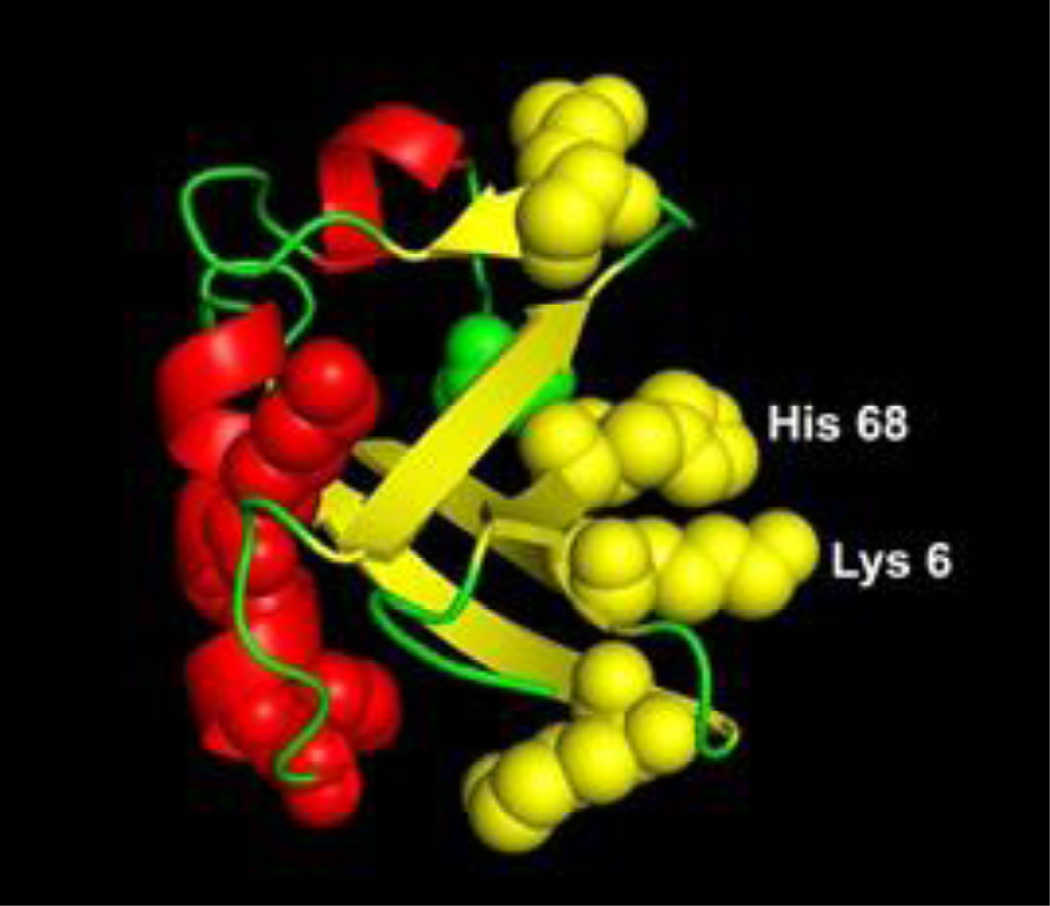

Despite numerous potential sites of modification, HNE treatment of Ub generally modified only one or two sites, even at the most extreme conditions examined (3 days incubation with [Ub]/[HNE]=1/400). The two residues modified, Lys-6 and His-68, are adjacent to each other and solvent accessible in the crystal structure of Ub (figure 6).21 MS2 spectra identifying the specific sites of HNE modification are shown in figure 1S and 2S of the supplementary material. This result is consistent with previous reports that residues in three acidic regions of the protein (i.e. residues 4–12, 42–51, and 62–71) are buried when Ub forms dimers.5 Since the two sites of HNE modification we obtain are in those regions, it appears that HNE precludes dimer formation by altering a portion of the surface that is buried upon dimer formation.

Figure 6.

Crystal structure (1UBQ) of Ub showing the location of 6Lys and 68His side chains.

Ub with more than two HNE adducts were only observed if a denaturant agent is added to the solution (figure 2b). This result demonstrates that the correct folding of Ub is responsible for the HNE addition to the native protein at only two sites rather than the many ones available according to the protein amino acidic sequence. We suspect that reports describing HNE modification of other sites in Ub are due to unreacted HNE remaining in the mixture after trypsin digestion,14,15 or to denaturing conditions. In this work, unreacted HNE was removed by hexane extraction prior to HNE modification. When excess HNE was removed from Ub solutions prior to trypsin digestion and non-denaturing conditions were used (absence of guanidine) HNE modifications were limited to two sites. As shown in figure 3S, additional HNE modifications are observed if a hexane extraction step to remove HNE prior to trypsin digestion is not performed.

Altogether, these results suggest that Ub oligomerizes at concentrations ≥ 5 µM, and that HNE interferes with this oligomerization. Indeed, we have found that HNE modified Ub forms oligomers only for concentrations ≥ 15µM. As it has been estimated that the concentration of free ubiquitin in cells is ~10 µM in mammalian cells,3 our results indicate that HNE modification of Ub could have a significant impact on Ub oligomerization also in vivo. Results were also confirmed by the PICUP experiments, which show that in the case of HNE modified Ub trimeric Ub species are not detected at all concentrations investigated (figure 5). HHE has a similar, albeit less potent effect.

These results may have important biological implications. Ub concentrations in cells are likely to be tightly regulated to carry out its functions. HNE modification of the protein would occur under conditions of oxidative stress, and may alter the oligomeric equilibrium in a way that interferes with the essential functions performed by Ub. Therefore, the alteration of Ub properties by HNE modification may regulate the ability of Ub to mediate the degradation of proteins under conditions of oxidative stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Information

This work was supported by NS74178 and GM76201 from the NIH, and grants from the Alzheimer’s Association, (to P.H.A.). G.G. thanks the U.S.-Italy Fulbright Commission for a 2015–2016 Fulbright grant and PRIN 2015 Prot. 20157WZM8A for financial support.

Abbreviations

- HNE

4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- HHE

4-hydroxy-2-hexenal

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Ub

ubiquitin

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Vilchez D, Saez I, Dillin A. The role of protein clearance mechanisms in organismal ageing and age-related diseases. Nature Communications. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukai A, Yamamoto-Hino M, Komada M, Okano H, Goto S. Balanced ubiquitination determines cellular responsiveness to extracellular stimuli. Cellular And Molecular Life Sciences. 2012;69:4007–4016. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicke L, Schubert HL, Hill CP. Ubiquitin-binding domains. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nrm1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dikic I, Wakatsuki S, Walters KJ. Ubiquitin-binding domains - from structures to functions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10:659–671. doi: 10.1038/nrm2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z, Zhang WP, Xing Q, Ren XF, Liu ML, Tang C. Noncovalent Dimerization of Ubiquitin. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2012;51:469–472. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Servage KA, Silveira JA, Fort KL, Clemmer DE, Russell DH. Water-Mediated Dimerization of Ubiquitin Ions Captured by Cryogenic Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry. J.Phys.Chem.Lett. 2015;6:4947–4951. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keller JN, Hanni KB, Markesbery WR. Impaired proteasome function in Alzheimer's disease. J.Neurochem. 2000;75:436–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindsten K, de Vrij FMS, Verhoef LGGC, Fischer DF, van Leeuwen FW, Hol EM, Masucci MG, Dantuma NP. Mutant ubiquitin found in neurodegenerative disorders is a ubiquitin fusion degradation substrate that blocks proteasomal degradation. J.Cell.Biol. 2002;157:417–427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Leeuwen FW, de Kleijn DPV, van den Hurk HH, Neubauer A, Sonnemans MAF, Sluijs JA, Koycu S, Ramdjielal RDJ, Salehi A, Martens GJM, Grosveld FG, Burbach JPH, Hol EM. Frameshift mutants of beta amyloid precursor protein and ubiquitin-B in Alzheimer's and Down patients. Science. 1998;279:242–247. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Axelsen PH, Komatsu H, Murray IVJ. Oxidative Stress and Cell Membranes in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Physiol. 2011;26:54–69. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00024.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakita C, Honda K, Shibata T, Akagawa M, Uchida K. A method for detection of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal adducts in proteins. Free Rad.Biol.Med. 2011;51:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaur RJ, Siems W, Bresgen N, Eckl PM. 4-Hydroxy-nonenal-A Bioactive Lipid Peroxidation Product. Biomolecules. 2015;5:2247–2337. doi: 10.3390/biom5042247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marques C, Pereira P, Taylor A, Liang JN, Reddy VN, Szweda LI, Shang F. Ubiquitin-dependent lysosomal degradation of the HNE-modified proteins in lens epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2004;18:1424. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1743fje. + [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colzani M, Criscuolo A, Casali G, Carini M, Aldini G. A method to produce fully characterized ubiquitin covalently modified by 4-hydroxy-nonenal, glyoxal, methylglyoxal, and malondialdehyde. Free Rad.Res. 2016;50:328–336. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2015.1118472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colzani M, Criscuolo A, De Maddis D, Garzon D, Yeum KJ, Vistoli G, Carini M, Aldini G. A novel high resolution MS approach for the screening of 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal sequestering agents. J.Pharm.Biomed.Anal. 2014;91:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed TT, Pierce WM, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Proteomic identification of HNE-bound proteins in early Alzheimer disease: Insights into the role of lipid peroxidation in the progression of AD. Brain Res. 2009;1274:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fancy DA, Kodadek T. Chemistry for the analysis of protein-protein interactions: Rapid and efficient cross-linking triggered by long wavelength light. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1999;96:6020–6024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bitan G, Lomakin A, Teplow DB. Amyloid β-Protein Oligomerization: Prenucleation Interactions Revealed by Photo-Induced Cross-Linking of Unmodified Proteins. J.Biol.Chem. 2001;276:35176–35184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bitan G, Teplow DB. Rapid photochemical cross-linking - A new tool for studies of metastable, amyloidogenic protein assemblies. Acc.Chem.Res. 2004;37:357–364. doi: 10.1021/ar000214l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burke MC, Wang Y, Lee AE, Dixon EK, Castaneda CA, Fushman D, Fenselau C. Unexpected Trypsin Cleavage at Ubiquitinated Lysines. Anal.Chem. 2015;87:8144–8148. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b01960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vijay-Kumar S, Bugg CE, Cook WJ. Structure of Ubiquitin Refined at 1.8 A Resolution. J.Mol.Biol. 1987;194:531–544. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90679-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.