Abstract

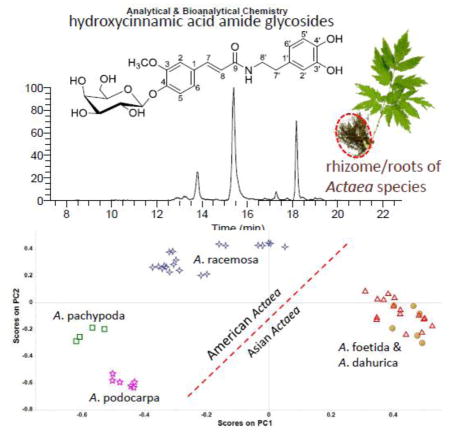

Due to the complexity and variation of the chemical constituents in authentic black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) and its potential adulterant species, an accurate and feasible method for black cohosh authentication is not easy. A high resolution accurate mass (HRAM) LC-MS fingerprinting method combined with chemometric approach was employed to discover new marker compounds. Seven hydroxycinnamic acid amide (HCAA) glycosides are proposed as potential marker compounds for differentiation of black cohosh from related species, including two Asian species (A. foetida, A. dahurica) and two American species (A. pachypoda, A. podocarpa). These markers were putatively identified by comparing their mass spectral fragmentation behavior with those of their authentic aglycone compounds and phytochemistry reports. Two isomers of feruloyl methyldopamine 4-O-hexoside ([M+H]+ 506) and one feruloyl tyramine 4-O-hexoside ([M+H]+ 476) contributed significantly to the separation of Asian species in principle component analysis (PCA) score plot. The efficacy of the models built on four reasonable combinations of these markers in differentiating black cohosh and its adulterants were evaluated and validated by partial least-square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). Two models based on these reduced dataset achieved 100% accuracy based on the current sample collection, including the model that used only three feruloyl dopamine-O-hexoside isomers ([M+H]+ 492) and one feruloyl dopamine-O-dihexoside ([M+H-hexosyl]+ at m/z 492).

Keywords: Hydroxycinnamic Acid Amide glycoside, Hydroxycinnamic Acid ester, UHPLC-HRMS, nitrogen-containing, PCA, PLS-DA

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Black Cohosh is officially defined as the dried rhizome and roots of Actaea racemosa L. [formerly Cimicifuga racemosa (L.) Nutt.] of the family Ranunculaceae harvested in the summer [1]. It is a plant native to eastern North America with a long history of medicinal use for the treatment of menopausal symptoms in North America and Europe. In recent years, black cohosh has enjoyed a rapid rise in popular use as a non-estrogenic alternative to hormone replacement therapy, which has been shown to cause increased risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular diseases [2–4], for the amelioration of menopausal symptoms.

The majority of commercial black cohosh is still wild crafted in the United States, and overharvesting is beginning to threaten its existence in the wild [5]. As a result of increasing commercial demand and shrinking natural stocks, black cohosh products in market may be adulterated with widely cultivated and less expensive Asian Actaea species [6]. Asian species of Actaea were generally used as traditional medicines for centuries. A. heracleifolia (Kom.), A. dahurica, and A. foetida are listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia as Sheng-Ma for their anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic properties [7]. Although these Sheng-Ma species share some constituents with black cohosh, their medical usage are different. Additionally, A. racemosa is often unintentionally mixed with other American Actaea species, such as A. podocarpa (yellow cohosh) and A. pachypoda (white cohosh) during harvest, due to its similar appearance and growing locales. These potential contaminants exerted unknown effect on menopausal symptoms [8]. Adulteration and plant misidentification of black cohosh remains a serious health concern.

Despite increasing consumption and extensive investigation, the mechanisms of its alleviation of climacteric symptoms remain largely undefined [9–11]. The phytochemical constitution of black cohosh is complex and the active ingredients remain unknown. The phytochemical investigation of black cohosh in the past several decades has focused almost exclusively on two abundant classes of compounds: triterpene glycosides and phenolic acid derivatives [12]. Cycloartane triterpenes constitute the majority of Actaea triterpenes, which are typically glycosylated at the C-3 position with D-xylose or L-arabinose. Abundant triterpenes such as actein and 23-epi-26-deoxyactein are often used as markers for the standardization of black cohosh preparations [13]. But these major constituents were also present in other American and Asian Actaea species [6, 14].

The phenolic compounds from Actaea species mainly consist of esters between the carboxyl group of caffeic, ferulic or isoferulic acid and the hydroxyl group of fukiic or piscidic acid (i.e. hydroxycinnamic acid esters). Profile analysis of phenolics and triterpenes using HPLC-UV, HPLC-MS and HPLC-ELSD (evaporative light scattering detection) have been successfully applied to distinguish A. racemosa from other American (i.e. A. pachypoda, A. podocarpa, and A. rubra), and Asian Actaea species [11, 14–17]. These profiling methods relied on the identification and comparison of chromatographic patterns of the complex components between Actaea species, which are not easy to perform routinely. Advanced expertise in both phytochemistry and MS is a prerequisite to recognizing specific marker compounds from the candidate pool which is composed of complicated and similar structural analogs.

He and co-workers indicated that two chromones, cimifugin and cimifugin glucoside, were present in Asian Actaea species (i.e. A. foetida, A. dahurica, and A. simplex), but absent in A. racemosa and some American Actaea [6, 18]. Cimifugin and cimifugin glucoside have been used as good indicators of commonly encountered Asian adulterants [8]. But cimifugin was not found in any of the A. rubra, A pachypoda, and A. podocarpa species [15]. Hence, differentiation of black cohosh from its American adulterants is still problematic.

The previous work of ours [19, 20] and other researchers [6, 8, 11, 14, 16, 18, 21–23] on black cohosh components focused primarily on: 1) using ESI-negative mode to detect phenolic acids and phenolic esters; 2) using ESI/APCI-positive mode to detect triterpenes. In order to explore useful information that may be neglected in the MS positive data, principle component analysis (PCA) was performed on positive data (especially compounds eluted ahead of triterpenes on reverse phase column) in this study. Seven hydroxycinnamic acid amide (HCAA) glycosides were identified as potential markers to distinguish black cohosh and other Actaea species. Partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) models based on these markers were investigated using leave-one-out cross-validation. It was discovered that feruloyl dopamine-O-hexosides can be used as effective marker compounds for authentication of Black Cohosh.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials and Chemicals

The certified rhizome/roots materials from various species of Actaea were purchased from the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia (AHP). The Standard Reference Material® Actaea racemosa was obtained from the National Institutes of Standards and Technology (NIST). The Actaea dahurica samples were purchased from the Internet and local stores in China. Commercial black cohosh supplements from different manufactures were purchased locally or from the Internet. All plant materials and finished products were authenticated using validated DNA sequencing authentication methods for Actaea [20, 24] at AuthenTechnologies LLC. These samples are all listed in Table 1. The reference compounds trans-N-caffeoyltyramine, trans-N-p-coumaroyltyramine, and trans-N-feruloyltyramine were kindly provided by Dr. Min Yang (National Engineering Laboratory for TCM Standardization Technology, Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences). HPLC grade methanol, acetonitrile, and formic acid were purchased from VWR International, Inc. (Clarksburg, MD, USA). HPLC water was prepared from distilled water using a Milli-Q system (Millipore Laboratories, Bedford, MA, USA).

Table 1.

Actaea samples used in this study

| ID | Species | Source |

|---|---|---|

| BCR01 | racemosa | AHP |

| BCR02 | pachypoda | AHP |

| BCR03 | foetida | AHP |

| BCR04 | racemosa | AHP |

| BCR05 | pachypoda | AHP |

| BCR06 | racemosa | AHP |

| BCR07 | racemosa | AHP |

| BCR08 | racemosa | AHP |

| BCR09 | racemosa | AHP |

| BCR10 | podocarpa | AHP |

| BCR11 | podocarpa | AHP |

| BCR12 | podocarpa | AHP |

| BCR13 | foetida | AHP |

| BCR16 | racemosa | AHP |

| BCR17 | racemosa | AHP |

| BCR18 | foetida | AHP |

| BCR19 | foetida | AHP |

| BCR20 | foetida | AHP |

| BCR21 | foetida | AHP |

| BCR22 | foetida | AHP |

| BCR23 | foetida | AHP |

| BCR24 | foetida | AHP |

| SRM3295 | racemosa | NIST |

| BCA06 | dahurica | Hebei, China |

| BCA07 | dahurica | Sichuan, China |

| BCA08 | dahurica | North Korea |

| BCS01 | supplement | Manufacture A |

| BCS02 | supplement | Manufacture B |

| BCS03 | supplement | Manufacture C |

| BCS04 | supplement | Manufacture D |

| BCS05 | supplement | Manufacture E |

Sample Preparation

Samples were ground into fine powder and then passed through a 20 mesh sieve. The extraction procedure was according to our previous report [25] with slight modification. Breifly, a 10 mg aliquot of each sample were extracted with 5.0 mL of methanol-water (7:3, v/v) using sonication and centrifugation as described. Then the supernatant was diluted 1:10 (v/v) with water and filtered through a 17 mm (0.20 μm) PVDF syringe filter (VWR Scientific, Seattle, WA) and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Each sample was extracted in duplicate. The injection volume for all samples was 2 μL.

UPLC-HRMSn Conditions

The UHPLC-HRMSn system consists of a LTQ Orbitrap XL MS with an Accela 1250 binary Pump, a PAL HTC Accela TMO autosampler, an Accela PDA detector (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA), and an Agilent G1316A column compartment (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The operating conditions of the electrospray (ESI) source were similar to our previous work [25] with the differeces were as follows: sheath gas at 70 (arbitrary units), spray voltage at 4.5 kV; capillary temperature, 250 °C; capillary voltage, 50 V; tube lens offset, 120 V. MSn activation parameters used an isolation width of 2.0 amu, max ion injection time of 200 ms, and normalized collision energy at 35%. The UHPLC separation was carried out on a Hypersil Gold C18 column (200 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of a combination of A (0.1% formic acid in water) and B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). A gradient elution program was employed as follows: from 5% to 25% B over 0–30.0 min, to 30% B at 40.0min, to 85% B at 60.0 min, to 95 % B at 65.0 min, and then a return to the initial conditions. The column temperature was set at 50 °C.

Data Processing

Data were initially acquired as RAW files which were first converted into mzXML by use of an open-source software package, ProteoWizard [26], and then processing of mzXML files using XCMS online [27] resulted in time-aligned ion features, which are defined as a unique m/z at a unique retention time. Parameter settings for XCMS processing were as follows: centWave for feature detection (Δ m/z = 2.5 ppm, minimum peak width = 5 s, and maximum peak width = 20 s); obiwarp settings for retention-time correction (profStep = 0.1); and parameters for chromatogram alignment, including mzwid = 0.015, minfrac = 0.25, and bw = 5. The relative quantification of ion features was based on EIC (extracted ion chromatogram) areas. The ion feature list was downloaded and the ion features at retention time 4.0–35.0 min of positive data were used for further statistical analysis in SIMCA-P (version 13.0 Umetrics, Sweden).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

PCA of Actaea samples using chromatographic fingerprints

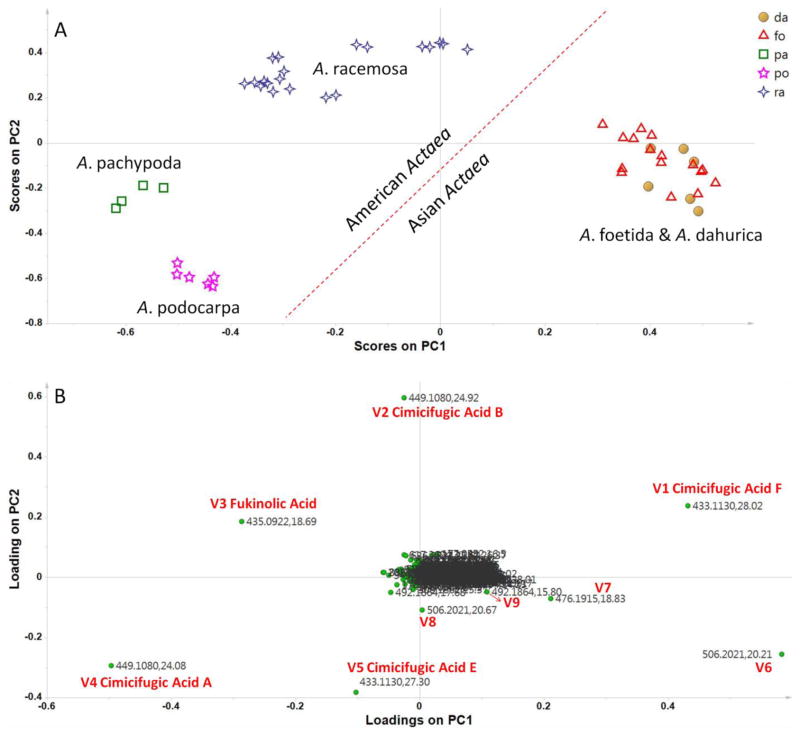

Fig. S1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) shows the eluting profiles of black cohosh over the entire UHPLC run time recorded by UV, ESI positive mode and ESI negative mode. PCA was performed on the ion features described in “Data processing” section. Fig. 1A shows a two-dimensional score plot for the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). The score plot provides a conceptual overview of the samples by explaining 63.3% of the total variance. A clear four-group separation was observed. A. racemosa could be distinguished from two Asian species A. foetida and A. dahurica, and the other two American species A. pachypoda and A. podocarpa. The three American Actaea species are clearly separated from the two Asian ones. The corresponding loading plot (Fig. 1B) reflects how much each of the variables contributes to the classification. The variables V1–V9 are far away from the origin, indicating they contribute significantly to the separation, among which, V6–V9 with even-numbered m/z value are positioned to the right of the loading plot, and accordingly the two Asian Actaea species with relatively high level of these variables stay in the right part of the score plot.

Fig. 1.

(A) PCA-score plot based on HRAM ESI positive data from all Actaea samples listed in Table 1. Sample icons: ○ dahurica (da), △ foetida (fo), □ pachypoda (pa), ☆ podocarpa (po), and ✧ racemosa (ra, i.e. black cohosh). (B) PCA-loading plots for samples of the five Actaea species.

The variables V1–V5 have been identified as cimicifugic acid F, cimicifugic acid B, fukinolic acid, cimicifugic acid A, cimicifugic acid E, respectively, in our previous study on flow injection mass spectrometric differentiation method for black cohosh (by ESI negative mode) [19]. The HPLC-UV fingerprint of them has been used to distinguish A. racemosa from major American and Asian Actaea species [11, 21]. The current study demonstrated that the EIC profile in MS positive mode of these five hydroxycinnamic acid esters could also distinguish A. racemosa from the other two American species and two Asian adulterants successfully, as shown in Fig. S2 (see ESM).

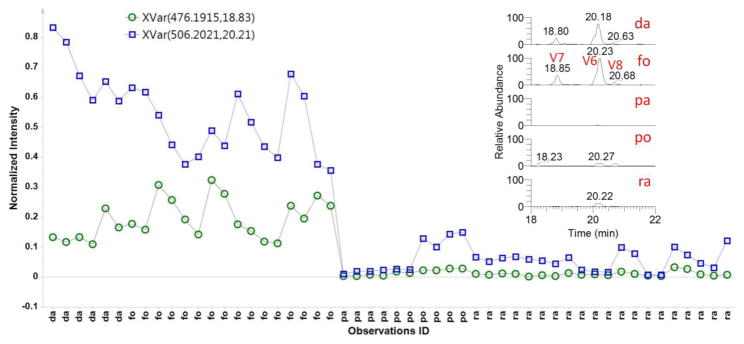

The variables V6–V9 are rarely mentioned in the literature on black cohosh authentication. Their even-numbered m/z value indicated that they probably are nitrogen containing compounds. The variable line plot of V6 and V7 revealed clearly their higher content levels in the two Asian species compared with the three American species (Fig. 2), which agreed with the EICs for V6 (V8, isomer of V6) and V7.

Fig. 2.

Line plot of variable V6 (blue square) and V7 (green circle) for all the Actaea samples in Table 1. Axis labels: da=dahurica; fo=foetida; pa=pachypoda; po=podocarpa; ra=racemosa. Extracted ion chromatograms for V6–V8 from five Actaea species were shown as references.

Putative Identification of Discriminative Compounds

The structural characterization of the discriminatory variables relies on HRAM values, retention times, MS2–MS5 mass spectra, ring-plus-double-bond (RDB) equivalent, literature reports and the use of standards when available.

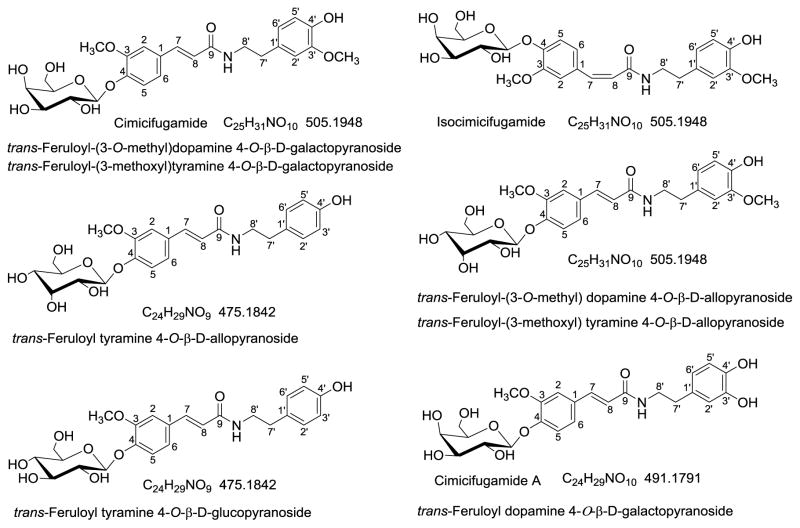

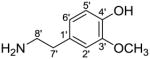

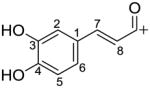

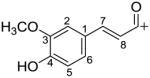

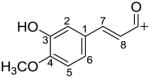

The spectrometric and chromatographic evidence of the ions with even-numbered m/z value pointed to a class of compounds, the hydroxycinnamic acid amide (HCAA) glycosides. HCAAs are a diverse group of nitrogenous compounds found in higher plants [28]. Generally speaking, HCAAs are conjugates of hydroxycinnamic acid and amine via amide bonds. They occur as basic or neutral forms. In the basic forms, only one amine group of an aliphatic di- or poly-amine is linked with a hydroxycinnamic acid. In neutral forms, type 1, each terminal amine group of an aliphatic amine is neutralized by a hydroxycinnamic acid. In neutral forms, type 2, they are aromatic amines, instead of aliphatic amines, conjugated with hydroxycinnamic acid [29]. The Actaea HCAAs belong to the type 2 neutral form. In contrast to triterpenes and phenolic acids/esters, HCAAs from Actaea species have received far less attention. Only six HCAA glycosides including Cimicifugamide [30], isocimicifugamide [31], trans-feruloyl-tyramine 4-O-β-D-alloside [32], trans-feruloyl-(3-O-methyl) dopamine 4-O-β-D-alloside [32], trans-feruloyl tyramine 4-O-β-glucopyranoside [33], and cimicifugamide A [33] have been isolated from Asian Actaea species (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Structures of hydroxycinnamic acid amide (HCAA) glycosides isolated from genus Actaea.

Three authentic HCAAs, trans-N-caffeoyltyramine, trans-N-p-coumaroyltyramine, and trans-N-feruloyltyramine, were used as reference compounds to investigate the fragmentation behaviors in ESI positive mode on our platform. The spectra of trans-N-caffeoyltyramine and trans-N-feruloyltyramine (ESM Fig. S3) demostrated consistent fragmentation patterns. Accurate mass measurement MS and MS2 spectra showed that the cleavage of the amide bond to eliminate the amine moiety is preferred, and produces a predominant ion corresponding to the hydroxycinnamoyl group, which is in accordance with previous reports [34, 35]. The amine moiety could be determined by the exact neutral loss value. The carboxylic acid portion was able to be further confirmed by the characteristic ions in the subsequent multi-stage fragmentation. The caffeoyl moiety yielded ions of m/z 163, 145, 135, 117, and 89 (ESM Fig. S3A); whereas feruloyl/isoferuloyl group was characterized by product ions at m/z 177, 145, 117, and 89 (ESM Fig. S3B) [36].

In Fig. S4A (see ESM), compound V6 presents the protonated molecular ion at m/z 506.2023 (C25H32NO10, 0.449ppm) and HCAA aglycone ion at m/z 344.1497 by eliminating a hexosyl moiety (162.0526 Da, very close to the theoretical value 162.0528 Da). The HCAA aglycone ion underwent further fragmentation similar to that observed in the reference compound trans-N-feruloyltyramine (Fig. S3B). The ion at m/z 177 originated from the loss of 167.0947 Da, corresponding to 3-methoxytyramine (Table 2). The fragment ions of m/z 177, 145, 117 indicated the feruloyl/isoferuloyl moiety. Nikolic et al.[36] distinguished between feruloyl and isoferuloyl based on the presence of a low abundance but diagnostic fragment ion at m/z 163, which was observed only during the fragmentation of protonated isoferulic acid, but not ferulic acid. By this method, the carboxylic acid portion was assigned as ferulic acid due to the absence of ion at m/z 163.

Table 2.

Typical neutral loss of amine moiety and cation of hydroxycinnamyl moieties in HCAAs

| Name & Formula | Structure | Accurate mass value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amine moiety (neutral loss) | Tyramine C18H11NO |

|

137.0841 |

| Dopamine C18H11NO2 |

|

153.0790 | |

| 3-Methoxytyramine/3-O-methyldopamine |

|

167.0946 | |

| Hydroxycinnamoyl group (cation) | Caffeoyl C9H7O3+ |

|

163.0390 |

| Feruloyl C10H9O3+ |

|

177.0546 | |

| Isoferuloyl C10H9O3+ |

|

177.0546 |

Considering the six HCAA glycosides isolated from Actaea plants are all glycosylated on the acid portion (4-O-glycosidation, Fig. 3), the position of glycosylation was assigned to the hydroxyl group on the feruloyl portion. The neutral loss of the amino moiety and the hexosylated feruloyl acylium ion at m/z 339 further supported the proposed assignment. Thus, V6 was partially characterized as feruloyl methyldopamine 4-O-hexoside. V8 was an isomer of V6 based on the almost identical spectra (data not shown) as V6. Three isomeric form of V6 have been isolated from genus Actaea, as shown in Fig. 3.

The full scan mass spectrum of V7 (ESM Fig. S4B) gave the [M+H]+ ion at m/z 476.1917 (C24H30NO9, 0.192ppm) and its dimer ion [2M+H]+ at m/z 951.3757. In the MS2 spectrum of the protonated molecular ion, the base peak at m/z 314 was produced by loss of 162 Da (the exact mass neutral loss was 162.0528 Da) corresponding to a hexosyl moiety. In Actaea species, the presence of glucose, galactose, and allose was reported to be attached to phenol group on the hydroxycinnamoyl portion (4-O-, Fig. 3) [30–33]. Further fragmentation of the [M+H-hexosyl]+ ion at m/z 314 produced a predominant ion at m/z 177 in MS3 spectrum, together with the ions at m/z 145 and 117observed in the successive MS4 and MS5 spectra, thus a feruloyl group could be deduced. The exact neutral loss from m/z 314 to 177 was 137.0841 Da, which was ascribed to tyramine (Table 2) [34]. Therefore, compound V7 can be putatively assigned as feruloyl tyramine 4-O-hexoside. Two isomers have been isolated from Actaea plants (Fig. 3).

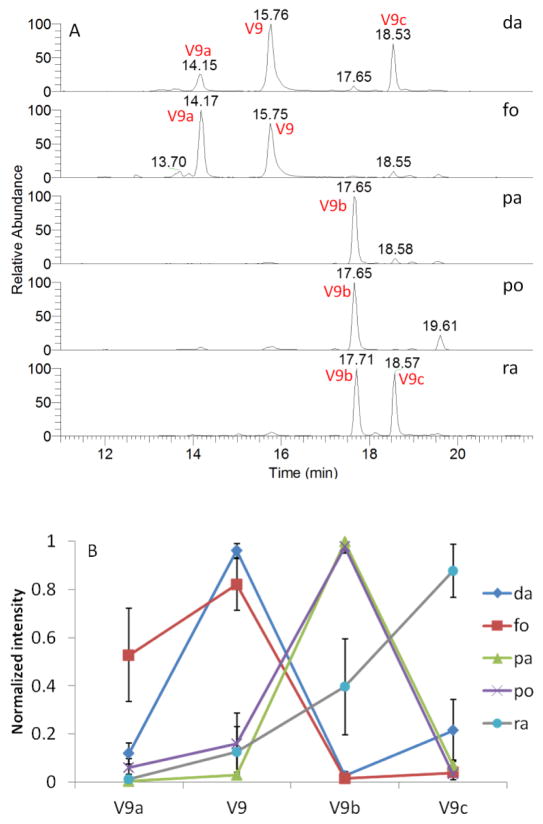

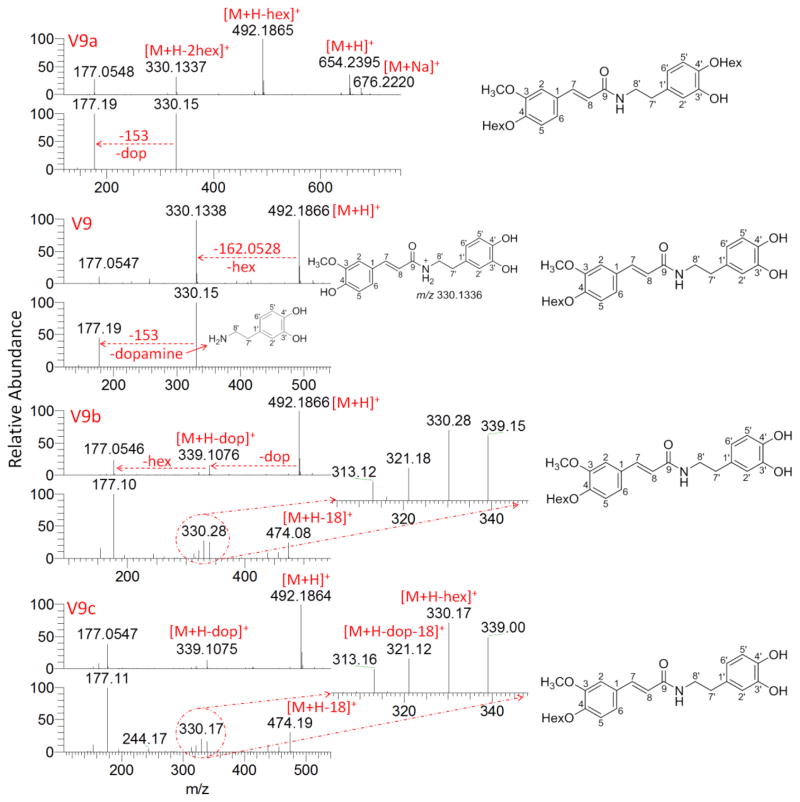

The EIC of ions at m/z 492 provided very interesting results, as seen in Fig. 4A. Three more major peaks were obtained other than compound V9. From their high resolution full scan spectra and the fragments of ions at m/z 492 (Fig. 5), compound V9, V9b, and V9c are isomers of feruloyl dopamine-O-hexosides, and V9a is feruloyl dopamine-O-di-hexoside. However, the determination of the glycosidation position is a very challenging task. Although the isolated hexosides of HCAA from Actaea plants were found to be 4-O-hexosides exclusively, both 4-O and 4′-O-hexosides have been described in other plants [37]. The hexosylated acylium ion of ferulic acid at m/z 339 and its water-loss ion at m/z 321 of V9b and V9c are evidence of 4-O-hexosides; but their lack of presence can not be the proof of 4′-O-hexosides in V9. Based on chemotaxonomic considerations, V9 had a great chance to be 4-O rather than 4′-O-hexosides. The presence of an ion at m/z 177 and absence of the diagnostic ion at m/z 163 strongly suggested that these compounds are amides of ferulic acid and not isoferulic acid, as mentioned above. Therefore, compound V9, V9b, and V9c can be partially characterized as feruloyl dopamine 4-O-hexoside, Cimicifugamide A and/or its isomers.

Fig. 4.

A) Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) for ion at m/z 492.18–492.19 of five Actaea species. B) Comparison of normalized intensity of V9a, V9, V9b, and V9c across species. Error bars represent standard deviations. Legends: da=dahurica; fo=foetida; pa=pachypoda; po=podocarpa; ra=racemosa.

Fig. 5.

Full scan (HRAM) and MS2 mass spectra of ions at m/z 492 from compound V9a, V9, V9b and V9c. Abbreviations: hex=hexosyl; dop=dopamine.

Compound V9a possessed the [M+H]+ ion at m/z 654.2395 (C30H40NO15, RDB 11.5, 0.389ppm) with an additional 162.0528 mass shift (compared to V9, V9b, and V9c) and [M+Na]+ ion at m/z 676.2220 (C30H39NO15Na, RDB 11.5, 1.197ppm). The product ion at m/z 492.1865 formed during in-source fragmentation and its further fragmented product ion at m/z 330, 177 supported the deduction that V9a was a dihexoside of ferulic acid amide. So V9a was assigned as feruloyl dopamine 4, 4′-O-dihexoside. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description of a HCAA dihexoside in plant. This assignment was in accordance with the elution behavior that V9a eluted first due to its higher polarity caused by one more sugar moiety.

Marker Compounds Selection for Black Cohosh Authentication

As indicated in the PCA loading plot (Fig. 1A), V1–V9 contributed to the separation between Actaea clusters and could be marker candidates for the authentication of black cohosh. In this study, PLS-DA models were constructed using whole and four reduced datasets which comprised selected variables: 1) V1–V9, V9a, V9b, and V9c (dataset A); 2) V1–V5 (dataset B); 3) V6–V8 (dataset C); 4) V9, V9a, V9b, and V9c (dataset D). The plant samples were grouped into two classes: black cohosh (BC) and black cohosh adulterant/contaminant (BCA). A cross-validation method that leaves one sample out was used to evaluate the model and the prediction rate (the number of samples used to build the model that are correctly classified) was calculated based on the class of BC and BCA, respectively. Then the discrimination models were used to predict the class membership of new samples, the supplements samples, yielding prediction rate of test samples, i.e. the number of independent samples that are correctly classified.

The PLS-DA model built on whole dataset (Model W) and four reduced datasets (Model A–D) were evaluated by prediction rate of plant materials BC/BCA and black cohosh supplements, shown in Table 3. The Model A and D achieved equivalent result as Model W, producing 100% accuracy, which means the taxonomic origin of plant samples were correctly assigned to their own class (BC or BCA). The PCA score plot using dataset A (ESM Fig. S5A) are very similar with its whole dataset counterpart in Fig. 1A, demonstrating that those 12 variables could be representative of the whole dataset chosen in the study. Although only four variables were used, Model D can differentiate black cohosh from four other potential adulterants. The PCA score plot (ESM Fig. S5D) based on the four variables also demonstrates an isolated group of A. racemosa. The normalized intensity of V9 family members across Actaea species is shown in Fig. 4B. The distribution curves of two Asian species showed similar trends, so did the two American species, whereas the black cohosh demonstrated a completely different tendency. It is interesting to compared Model A with Model D, since both provide 100% accuracy to classify the training and test samples into BC or BCA group. Obviously, the method using V9 family is much more convenient with fewer variables and only one m/z value (492) involved. However, dataset A applies when the differentiation of each individual American species is also the interest of the study and not just authentication.

Table 3.

PLS-DA models using whole and four reduced datasets

| PLS-DA Model | Variables Used | Prediction Ratea

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCb | BCAc | Supplementd | ||

| Model W | Whole dataset | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Model A | V1–V9, V9a, V9b, V9c | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Model B | V1–V5 | 65.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| Model C | V6–V8 | 100.0% | 81.3% | 100.0% |

| Model D | V9, V9a, V9b, V9c | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

the number of samples that are correctly classified.

Actaea racemosa plant samples, used as training samples.

other Actaea plant samples, used as training samples.

used as test samples.

The prediction rate of Model B on BC and Model C on BCA (Table 3) were not satisfactory; indicating that authentication of black cohosh could not solely rely on the combination of V1–V5 or V6–V8, although some of those variables could be used as indicators of certain species. PCA score plots using dataset B and dataset C are shown in Figs. S5B and S5C (see ESM), some of A. racemosa samples were observed to overlap with A. dahurica and A. podocarpa, respectively.

The supplement samples were classified correctly as BC by all five models in the current collection of samples, pointing out the possibility of applying the method to supplements authentication. Further investigation will be carried out to verify or improve this approach with more supplements samples.

Conclusions

An HRAM LC-MS fingerprinting method combined with PCA was employed to search for new potential black cohosh authentication marker compounds. Five hydroxycinnamic acid esters (V1–V5, i.e. cimicifugic acid F, cimicifugic acid B, fukinolic acid, cimicifugic acid A, cimicifugic acid E) and seven HCAA glycosides (V6–V9 family) stood out from the loading plot. PLS-DA models were built on the whole dataset and four combinations of those marker candidates and the prediction rate were calculated. Models based on dataset A (V1–V9 family) and dataset D (V9 family only) achieved 100% prediction rate of BC and BCA in our current collection of both plant materials and dietary supplements. Model D, requiring only one m/z value at 492 (corresponding to four feruloyl dopamine-O-hexosides), is recommended as a faster and easier approach to authenticate black cohosh. HCAA glycosides were firstly proposed to be used as black cohosh authentication marker compounds and feruloyl dopamine 4, 4′-O-dihexoside (V9a) was described in plants for the first time. Using V9 family ions to differentiate A. racemosa from its common adulterant, the two Asian species, and its common contaminants, the two American black cohosh species, is quick, easy and robust since it is not economically to add or extract a member of V9 family for adulteration purposes. Thus, they can be used as effective marker compounds as orthogonal validation for authentication of Black Cohosh, or even used by themselves if necessary.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1 UHPLC chromatograms of Black Cohosh (Actaea racemosa) obtained from PDA and Orbitrap MS. A: UV 190–600nm; B: ESI positve mode; C: ESI negative mode

Fig. S2 Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) in the positive ionization mode for variable V1–V5 at m/z 433.11–433.12, 435.09–435.10, and 449.10–449.12. A: A. racemosa; B: A. pachypoda; C: A. podocarpa; D: A. foetida; E: A. dahurica

Fig. S3 HRAM full scan/MS2, multi-stage mass spectra and main fragmentation for reference compounds trans-N-caffeoyltyramine (A) and trans-N-feruloyltyramine (B)

Fig. S4 Full scan (HRAM) and MS2–MS5 mass spectra of compound V6 (A) and V7 (B). Abbreviations: hex=hexosyl; dop=dopamine; medop=methyldopamine

Fig. S5 PCA score plot with variable (A) V1–V9, V9a, V9b, and V9c (dataset A); (B) V1–V5 (dataset B); (C) V6–V8 (dataset C); (D), V9a, V9, V9b, and V9c (dataset D)

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and an Interagency Agreement with the Office of Dietary Supplements of the National Institutes of Health (Grant Y01 OD001298-01). Dr. Mengliang Zhang is a fellow of John A. Milner Fellowship program supported by USDA Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center and the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest and no non-financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. United States Pharmacopoeia 38–National Formulary 33. Rockville, MD, U.S: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative I. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narod SA. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(11):669–76. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Million Women Study C. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. The Lancet. 2003;362(9382):419–27. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14065-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Small CJ, Chamberlain JL, Mathews DS. Recovery of Black Cohosh (Actaea racemosa L.) Following Experimental Harvests. The American Midland Naturalist. 2011;166(2):339–48. doi: 10.1674/0003-0031-166.2.339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He K, Pauli GF, Zheng B, Wang H, Bai N, Peng T, et al. Cimicifuga species identification by high performance liquid chromatography–photodiode array/mass spectrometric/evaporative light scattering detection for quality control of black cohosh products. Journal of Chromatography A. 2006;1112(1–2):241–54. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.China Pharmacopoeia Committee. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. 2015. Beijing: Chinese medicine and technology publishing house; 2015. pp. 73–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang B, Kronenberg F, Nuntanakorn P, Qiu M-H, Kennelly EJ. Evaluation of the Botanical Authenticity and Phytochemical Profile of Black Cohosh Products by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Selected Ion Monitoring Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(9):3242–53. doi: 10.1021/jf0606149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu F, McAlpine JB, Krause EC, Chen S-N, Pauli GF. Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products 99. Springer; 2014. Pharmacognosy of black cohosh: the phytochemical and biological profile of a major botanical dietary supplement; pp. 1–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viereck V, Emons G, Wuttke W. Black cohosh: just another phytoestrogen? Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;16(5):214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.05.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuntanakorn P, Jiang B, Yang H, Cervantes-Cervantes M, Kronenberg F, Kennelly EJ. Analysis of polyphenolic compounds and radical scavenging activity of four American Actaea species. Phytochem Anal. 2007;18(3):219–28. doi: 10.1002/pca.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li JX, Yu ZY. Cimicifugae Rhizoma: From origins, bioactive constituents to clinical outcomes. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;13(24):2927–51. doi: 10.2174/092986706778521869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betz JM, Anderson L, Avigan MI, Barnes J, Farnsworth NR, Gerdén B, et al. Black Cohosh: Considerations of Safety and Benefit. Nutrition Today. 2009;44(4):155–62. doi: 10.1097/NT.0b013e3181af63f9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma C, Kavalier AR, Jiang B, Kennelly EJ. Metabolic profiling of Actaea species extracts using high performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218(11):1461–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gafner S, Sudberg S, Sudberg EM, Villinski JR, Gauthier R, Bergeron C. Chromatographic fingerprinting as a means of quality control: distinction between Actaea racemosa and four different Actaea species. Acta Hortic. 2006;720(Proceedings of the IVth International Conference on Quality and Safety Issues Related to Botanicals, 2005):83–94. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2006.720.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avula B, Ali Z, Khan IA. Chemical fingerprinting of Actaea racemosa (Black cohosh) and its comparison study with closely related Actaea species (A. pachypoda, A. podocarpa, A. rubra) by HPLC. Chromatographia. 2007;66(9/10):757–62. doi: 10.1365/s10337-007-0384-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang B, Ma C, Motley T, Kronenberg F, Kennelly EJ. Phytochemical fingerprinting to thwart black cohosh adulteration: a 15 Actaea species analysis. Phytochem Anal. 2011;22(4):339–51. doi: 10.1002/pca.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He K, Zheng B, Kim CH, Rogers L, Zheng Q. Direct analysis and identification of triterpene glycosides by LC/MS in black cohosh, Cimicifuga racemosa, and in several commercially available black cohosh products. Planta Med. 2000;66(7):635–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang H, Sun J, McCoy J-A, Zhong H, Fletcher EJ, Harnly J, et al. Use of flow injection mass spectrometric fingerprinting and chemometrics for differentiation of three black cohosh species. Spectrochim Acta, Part B. 2015;105:121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sab.2014.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harnly J, Chen P, Sun J, Huang H, Colson KL, Yuk J, et al. Comparison of Flow Injection MS, NMR, and DNA Sequencing: Methods for Identification and Authentication of Black Cohosh (Actaea racemosa) Planta medica. 2016;82(3):250–62. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1558113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bittner M, Schenk R, Springer A, Melzig MF. Economical, Plain, and Rapid Authentication of Actaea racemosa L. (syn. Cimicifuga racemosa, Black Cohosh) Herbal Raw Material by Resilient RP-PDA-HPLC and Chemometric Analysis. Phytochemical Analysis. 2016;27(6):318–25. doi: 10.1002/pca.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li W, Sun Y, Liang W, Fitzloff JF, van Breemen RB. Identification of caffeic acid derivatives in Actea racemosa (Cimicifuga racemosa, black cohosh) by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17(9):978–82. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H-K, Sakurai N, Shih CY, Lee K-H. LC/TIS-MS fingerprint profiling of Cimicifuga species and analysis of 23-epi-26-deoxyactein in Cimicifuga racemosa commercial products. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(5):1379–86. doi: 10.1021/jf048300d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynaud D. DNA sequencing of SRM 3295, Actaea racemosa. AuthenTechnologies, LLC; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geng P, Sun J, Zhang M, Li X, Harnly JM, Chen P. Comprehensive characterization of C-glycosyl flavones in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) germ using UPLC-PDA-ESI/HRMSn and mass defect filtering. J Mass Spectrom. 2016;51(10):724–40. doi: 10.1002/jms.3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessner D, Chambers M, Burke R, Agus D, Mallick P. ProteoWizard: open source software for rapid proteomics tools development. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(21):2534–6. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tautenhahn R, Patti GJ, Rinehart D, Siuzdak G. XCMS Online: a web-based platform to process untargeted metabolomic data. Anal Chem. 2012;84(11):5035–9. doi: 10.1021/ac300698c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Facchini PJ, Hagel J, Zulak KG. Hydroxycinnamic acid amide metabolism: physiology and biochemistry. Canadian Journal of Botany. 2002;80(6):577–89. doi: 10.1139/b02-065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin-Tanguy J. The occurrence and possible function of hydroxycinnamoyl acid amides in plants. Plant Growth Regulation. 1985;3(3):381–99. doi: 10.1007/bf00117595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Chen D, Xiao P, Hong S, Ma L. Chemical Constituents of Traditional Chinese Drug “Sheng-ma”(Cimicifuga Dahurica). II. Chemical Structure of Cimicifugamide. Acta Chim Sinica. 1994;52(3):296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li C, Chen D, Xiao P. Studies on phenolic glycosides isolated from Cimicifuga dahurica. Acta Pharm Sinica. 1994;29:199. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yim S-H, Kim H-J, Jeong N-R, Park K-D, Lee Y-J, Cho S-D, et al. Structure-guided identification of novel phenolic and phenolic amide allosides from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga heracleifolia. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2012;33(4):1253–8. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2012.33.4.1253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang F, Han L-F, Pan G-X, Peng S, Andre N. A new phenolic amide glycoside from Cimicifuga dahurica. Acta Pharm Sinica. 2013;48(8):1281–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Guan S, Sun J, Liu T, Chen P, Feng R, et al. Characterization and profiling of phenolic amides from Cortex Lycii by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;407(2):581–95. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun J, Song Y-L, Zhang J, Huang Z, Huo H-X, Zheng J, et al. Characterization and Quantitative Analysis of Phenylpropanoid Amides in Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) by High Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Diode Array Detection and Hybrid Ion Trap Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63(13):3426–36. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikolic D, Godecke T, Chen S-N, White J, Lankin DC, Pauli GF, et al. Mass spectrometric dereplication of nitrogen-containing constituents of black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa L.) Fitoterapia. 2012;83(3):441–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yahagi T, Yamashita Y, Daikonnya A, Wu J-b, Kitanaka S. New Feruloyl Tyramine Glycosides from Stephania hispidula YAMAMOTO. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2010;58(3):415–7. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 UHPLC chromatograms of Black Cohosh (Actaea racemosa) obtained from PDA and Orbitrap MS. A: UV 190–600nm; B: ESI positve mode; C: ESI negative mode

Fig. S2 Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) in the positive ionization mode for variable V1–V5 at m/z 433.11–433.12, 435.09–435.10, and 449.10–449.12. A: A. racemosa; B: A. pachypoda; C: A. podocarpa; D: A. foetida; E: A. dahurica

Fig. S3 HRAM full scan/MS2, multi-stage mass spectra and main fragmentation for reference compounds trans-N-caffeoyltyramine (A) and trans-N-feruloyltyramine (B)

Fig. S4 Full scan (HRAM) and MS2–MS5 mass spectra of compound V6 (A) and V7 (B). Abbreviations: hex=hexosyl; dop=dopamine; medop=methyldopamine

Fig. S5 PCA score plot with variable (A) V1–V9, V9a, V9b, and V9c (dataset A); (B) V1–V5 (dataset B); (C) V6–V8 (dataset C); (D), V9a, V9, V9b, and V9c (dataset D)