Abstract

Tissue-specific immune responses play an important role in the pathology of autoimmune diseases. In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), deposits of IgG-immune complexes and the activation of complement in the kidney have long been thought to promote inflammation and lupus nephritis. However, the events that localize cells in non-lymphoid tertiary organs and sustain tissue-specific immune responses remain undefined. In this manuscript, we show that B cell activating factor of the TNF family (BAFF) promotes events leading to lupus nephritis. Using an inducible model of SLE, we found that passive transfer of anti-nucleosome IgG into AID−/−MRL/lpr mice elevated autoantibody levels and promoted lupus nephritis by inducing BAFF production in the kidneys, and the formation of renal tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs). Reducing BAFF in vivo prevented the formation of TLSs and lupus nephritis; however, it did not reduce immune cell infiltrates, or the deposits of IgG and complement in the kidney. Mechanistically, lowering BAFF levels also diminished the number of T cells positioned inside the glomeruli and reduced inflammation. Thus, BAFF plays a previously unappreciated role in lupus nephritis by inducing renal TLSs and regulating the position of T cells within the glomeruli.

Introduction

The immune response in peripheral tissues is phenotypically and functionally different from responses in secondary lymphoid organs (1). In some autoimmune diseases, tertiary lymphoid organogenesis is evident in tonsils, islets, and the CNS (2–4). In non-lymphoid organs, cells compartmentalize into discrete areas reminiscent of the B- and T-cell zones found in secondary lymphoid organs (5). These structures are referred to tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs). In a model of pristane induced murine SLE, B cells proliferate and class switch within TLSs, and anti-Sm/RNA antibody producing plasma cells/plasmablasts home to TLSs and continuously produce autoantibodies (6, 7). Further, kidneys from SLE patients with lupus nephritis show germinal center-like structures containing follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) and in situ clonal expansion of B cells, suggesting active local tissue-specific immune responses (8). Identifying the events that initiate the formation of TLSs would advance our understanding of lupus nephritis.

The deposition of IgG-ICs and complement in the kidney has long been thought to be a dominant pathogenic factor in lupus nephritis through the binding of autoreactive IgGs to renal antigens (9–11), or their binding to chromatin fragments forming immune complexes that deposit in the kidney (12, 13). However, recent data show that in the absence of disease, deposits of IgG-ICs or complement persist in the kidney (14, 15). This suggests that deposition of ICs is not sufficient for renal pathology. This idea is supported by another study showing that expression of FcγR on hematopoietic cells, rather than kidney mesangial cells, is required for lupus nephritis (16). Further, we recently showed that IgG-ICs bound to activating FcγRs accumulate on the surface of hematopoietic cells from lupus-prone mice (17). This occurs as a result of lysosomal maturation defect that diminishes degradation of FcγR-bound ICs (18), promoting autoantibody secretion, the expansion of autoreactive B cells, and lupus nephritis (17). Thus, the emerging data suggest that lupus nephritis may require the activation of the immune system through FcγRs on hematopoietic cells.

In murine lupus, excess BAFF allows self-reactive B cells to survive and escape peripheral tolerance checkpoints (19, 20). As such, BAFF became a prime therapeutic target in SLE (21). BAFF deficiency (14) or neutralization (22) improves kidney function in mice; however, these effects could be secondary to the depletion of B cells (23). In human SLE, increased levels of BAFF are associated with disease pathology (24), and clinical trials of anti-BAFF demonstrate reduced rates of overall and severe flares in association with reduced autoreactive B cell responses (25, 26). The effectiveness of anti-BAFF therapy in human lupus nephritis has not been reported despite the wealth of knowledge regarding the role of BAFF in murine B cell responses.

Previously, we developed an inducible model of lupus where passive transfer of anti-nucleosome IgG (PL2-3) into AID−/−MRL/lpr mice elevated splenic B cell numbers and the frequency of BAFF secreting dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages (MFs) coincident with lupus nephritis (17). In the present study, we show that as the levels of BAFF and serum autoantibody increased, TLSs formed in the kidneys, and glomeruli and tubules showed cell infiltration and inflammation. Reducing BAFF levels diminished the numbers of T cells in the glomeruli, prevented lupus nephritis and the formation and/or maintenance of TLSs; however, infiltration of cells into the kidney was unaffected. These data show a previously unappreciated role of BAFF in the formation of TLSs and the localization of T cells at the onset of lupus nephritis, suggesting that reducing BAFF levels may be efficacious in preventing lupus nephritis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57B6, AID−/−MRL/lpr (27), and MRL/MpJ-Faslpr/J (Stock # 000485) (MRL/lpr) colonies were maintained in an accredited animal facility at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Passive transfer of anti-nucleosome antibody

AID−/−MRL/lpr mice (18–20 weeks old, mixed gender) were intravenously (i.v.) injected with 500 μg of PL2-3 (anti-nucleosome, IgG2a) (28), F(ab′)2 of PL2-3 (GenScript, F(ab′)2 size at 110kD by SDS-PAGE), Hy1.2 (anti-TNP, isotype control IgG2a), or PBS weekly for 2 or 5 weeks (17). The binding capacity of F(ab′)2 of PL2-3 was comparable to intact PL2-3 when analyzed by anti-nucleosome ELISA. To reduce BAFF levels, mice were treated weekly with PL2-3 (500 μg) in combination with every other week treatment of 3.3 mg/kg of BR3-Fc (Eli Lilly), or control IgG1. Five days after the 5th injection, mice were euthanized.

ELISA

The levels of serum IgM (total, anti-nucleosome, and anti-dsDNA) were quantitated as previously described (29). Serum BAFF ELISA was performed using BR3-Fc as the capture antibody and biotinylated-anti-mouse BAFF (clone 1C9, Enzo) as the detection antibody. A standard curve was generated using recombinant mouse BAFF (R&D).

ELISpot

BAFF secreting cells were enumerated on ELISpot plates (Millipore) coated with BR3-Fc. For each mouse, 1×106 total kidney cells from one kidney were incubated for 60hrs in each well of a coated ELISpot plate, and then detected with biotinylated anti-BAFF (1C9).

Histology

Formalin fixed and paraffin embedded kidney sections were stained for H&E and viewed on a conventional light microscope by a pathologist blinded to the experimental groups. The glomerular and tubulointerstitial nephritis were graded following original and modified classification of nephritis (30, 31). Scores for glomerular lesions: 0 = no H&E changes (Class I); 1 = minimal mesangial hypercellularity without visualized immune deposits (Class II); 2 = focal immune deposits (Class III); 3 = diffuse glomerulonephritis with widespread subendothelial immune deposits (Class IV); 4 = global immune deposits with associated sclerosis (Class V and VI). Interstitial inflammation was scored based on the degree of tubulointerstitial involvement: 0 = no infiltrate or inflammation; 1 = < 10%; 2 = 10% to 50%; 3 = >50% of the tubulointerstitium.

Proteinuria Scoring

Urine protein was assessed according to Uristix strip (Siemens) instruction.

Counting Tertiary Lymphoid Structures

Bright field macroscopic images of H&E stained whole kidney were obtained using Leica WILD macroscope M420 (magnification at 16× with APOZOOM lens, Epi-illumination imaging in reflected light) and QImaging micropublisher camera (QCapture software). On randomly selected images from each treatment group, clusters containing hematoxylin positive cells were counted using the tracing tool of Image J. Area (pixels) was measured on uncalibrated images. Areas >1000 pixels were defined as large clusters, and areas between 100 and 1000 pixels were defined as small clusters (area for each glomeruli is between 190 and 250 pixels).

Immunofluorescence

To assess the deposits of IgG and complement component 3 (C3), snap-frozen kidney sections (8 microns) were stained with DyLight 488 conjugated anti-IgG-Fc (Jackson Immunoresearch) and PE conjugated anti-C3 (Cedarlane). To localize immune cells and TLSs in the kidney, snap-frozen sections were stained with anti-CD19 (PE), anti-CD4 (FITC), anti-CD8 (FITC), anti-CD11b (APC), or anti-CD21 (FITC) (Biolegend), then, counter-stained with Hoechst 33342 for nuclear staining (Immunochemistry). Samples were visualized on LSM 710 spectral confocal laser scanning microscope (20x/0.8 Plan Apo lens, Carl Zeiss). Lasers excite at 405nm, 488nm, 543nm, and 633nm were used for violet, FITC, PE, and APC channels. Images were modified using Image J software. The modifications (brightness and contrast) applied to each color channels (Red, Green, Blue, and Gray) were the same for all images analyzed for TLSs, IgG, C3, or cells infiltrated to glomeruli. For quantification of IgG and C3, the integrated density of the fluorescence of each glomerulus was measured using image J software and normalized values (raw integrated density value/area measured) of IgG and C3 deposits were graphed. In all images for TLSs and cells infiltrated into glomeruli, T cells are red, B cells green and CD11b+ myeloid cells are blue. In some experiments, gray color was used for nuclear stain.

Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions of splenocytes, and total kidney cells from one kidney of each mouse, were stained with cell type specific antibodies (CD19+ B cells, CD3+ T cells, CD19negCD3negCD11chi/CD11b+ DCs, and CD19negCD3negCD11cnegCD11bhi Myeloid cells) (Biolegend) and analyzed by flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). CD45 was used to identify leukocytes within the total kidney cell population. Whole kidney was minced into fine pieces, incubated for 1 hour at 4°C in 2% FBS/PBS with shaking and pieces were washed with cold PBS. Single cell suspensions were prepared using frosted glass slides following the treatment with Collagenase Type I (2 mg/ml, 30 min at 37ºC) (Worthington) (32). This method was compared side-by-side with whole body perfusion and found to yield comparable numbers of hematopoietic cells and total kidney cells (1.03 fold perfusion/mincing).

Statistics

The Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc procedure was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc). To simplify the graphical presentations, although all the treatment groups were compared, we only showed p values of key pairwise comparisons (adjusted p<0.05).

Results

Passive transfer of anti-nucleosome IgG induces the infiltration of cells into the kidney, the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs), and lupus nephritis

To understand the impact of IgG-ICs on the immune system during the onset of SLE, we passively transferred anti-nucleosome antibody (PL2-3; IgG2a) into AID−/−MRL/lpr mice (Figure 1A). AID−/−MRL/lpr mice lack IgG due to a deficiency in isotype switching, and they do not develop lupus nephritis (27). However, passive transfer of anti-nucleosome IgG into these mice induces synchronous onset of disease (17). We found that 5 weeks of passive antibody transfer induced a 6–7 fold increase in the levels of autoreactive antibodies, and a 2.5-fold increase in glomerular and tubulointerstitial disease, including fibrocellular crescents. This phenotype required the MRL/lpr background because injection of PL2-3 into B6 mice did not induce proteinuria, deposits of IgG or complement, or glomerular inflammation (17).

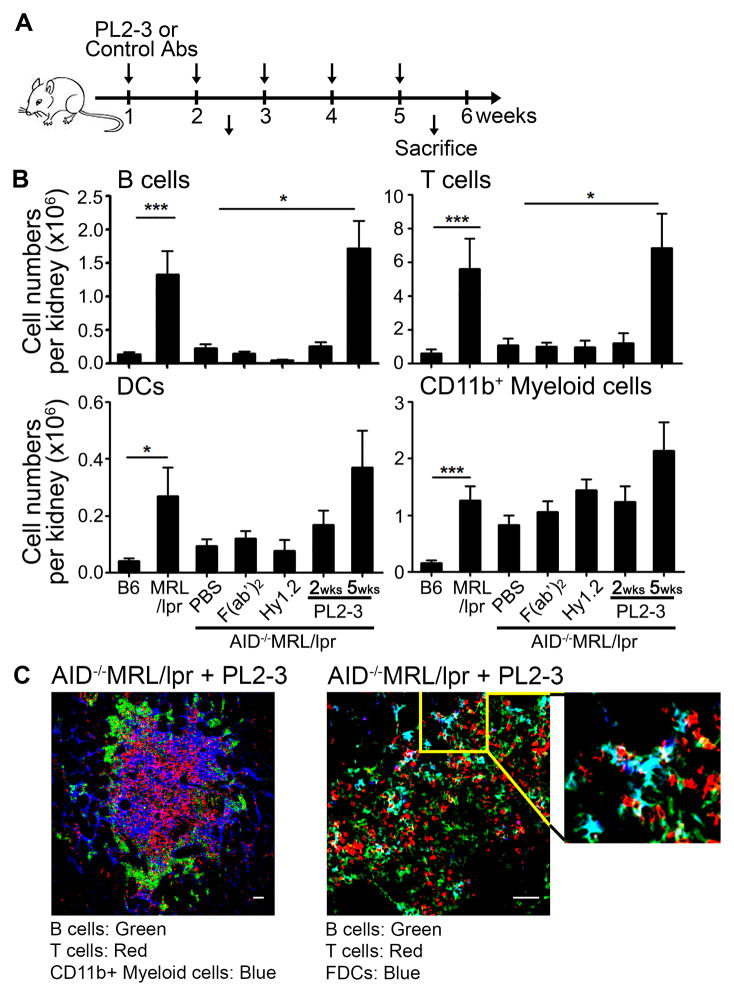

Figure 1. Treatment of AID−/−MRL/lpr mice with anti-nucleosome IgG induces the infiltration of hematopoietic cells into the kidneys and renal TLSs.

(A) AID−/−MRL/lpr mice were treated with PBS, 500 μg of PL2-3 (anti-nucleosome) or control F(ab′)2 of PL2-3 i.v. weekly for 2 or 5 weeks. (B) B cells (CD19+), T cells (CD3+), DCs (CD19negCD3negCD11b+CD11chi), and CD11b+ myeloid cells (CD19negCD3negCD11bhiCD11cneg) were enumerated by flow cytometry from total kidney cells. The cell numbers presented are from one kidney from each mouse (n= total of 10 to >25 mice per treatment from >5 separate experiments). (C) Kidneys from PL2-3 treated AID−/−MRL/lpr mice for 5 weeks were stained for CD19+ B cells (Green), CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Red), CD11b+ myeloid cells (Blue) (left panel); or CD19+ B cells (Green), CD3+ T cells (Red), CD21+ FDCs (Blue) (right panel). Images were taken at 12x magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm. Representative images from 3 experiments (n = 9 mice). In (B) results are ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc procedure.

Migration of hematopoietic cells to the kidney is necessary to induce inflammation and end-stage renal disease (33). After 2 weeks of PL2-3 treatment, hematopoietic cells had not infiltrated the kidney; however, by 5 weeks the numbers of infiltrating B and T cells increased 7-fold, DCs (CD11chiCD11b+) 4-fold, and myeloid cells (CD11cnegCD11bhi), 2-fold compared to PBS treatment (Figure 1B); levels comparable to diseased MRL/lpr mice. Within the B cell population, the plasma cells were increased 20-fold in MRL/lpr mice compared to B6, and 3-fold in PL2-3 treated AID−/−/MRL/lpr mice compared to PBS treated mice (Supplemental Figure 1A left panel). These CD19negCD138pos cells expressed XBP-1, consistent with antibody secreting plasma cells (Supplemental Figure 1A right panel). The increase in hematopoietic cells in the kidney was dependent on the Fc-region of PL2-3 because mice treated with F(ab′)2 did not show infiltrated cells. Further, the increased infiltration was not due to the binding of monomeric IgG to FcγRs, since injection of anti-TNP (Hy1.2) did not induce infiltration (Figure 1B). Last, the increased infiltration of cells to the kidney was not limited to the nucleosome-specificity of the transferred antibody, since the injection of anti-Sm (22G12; IgG2a (34)) promoted similar levels of immune cell infiltration (Supplemental Figure 1C). These data implicate FcγRs and their binding to IgG-ICs in the infiltration of hematopoietic cells into the kidneys.

The presence of TLSs in non-lymphoid tissues has been reported in various autoimmune diseases including human lupus nephritis (2, 3, 8, 35). We found that the number of TLSs, as defined by the size of cell clusters and organization, were increased 6-fold in mice treated with PL2-3 for 5 weeks compared to PBS (Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure 2). The clusters of cells were mostly found interspersed in the tubulointerstitial area with some clusters large enough to contain multiple glomeruli within the structure (Supplemental Figure 2). TLSs (large structures) were often compartmentalized, consisting of multiple clusters of B cells adjacent to areas containing T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells (Figure 1C left panel). We also found CD21+ FDCs adjacent to B cell clusters in the TLSs, suggesting active in situ B cell responses in the kidney (Figure 1C right panel). Thus, autoreactive IgG bound to apoptotic debris (IgG-ICs) and FcγRs promotes the infiltration of hematopoietic cells into the kidneys, the formation of TLSs, and lupus nephritis.

Passive transfer of autoantibody heightens BAFF production in the kidneys

In vitro, IgG-ICs have been implicated in BAFF secretion by DCs (36). To assess whether PL2-3 treatment elevated BAFF levels in vivo, we quantitated serum levels after 5 weeks of injection. We found that PL2-3, but not F(ab′)2 of PL2-3 or Hy1.2, elevated serum BAFF levels 3-fold over PBS controls; levels exceeding diseased MRL/lpr mice (Figure 2A). The inability of PL2-3 F(ab′)2 or Hy1.2 to induce heightened BAFF implicates the binding of IgG-IC to FcγRs in elevating BAFF levels.

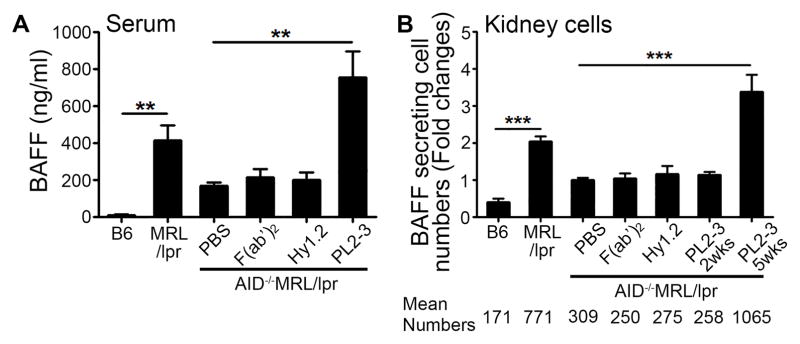

Figure 2. Treatment of AID−/−MRL/lpr mice with anti-nucleosome IgG promotes heightened BAFF production.

(A) Serum BAFF levels were analyzed by ELISA after 5 weeks of treatment. (B) BAFF secreting kidney cells were enumerated by ELISpot after 2 or 5 weeks of treatment. Fold changes over PBS treated AID−/−MRL/lpr mice were graphed. Mean numbers of BAFF secreting cells per 106 cells are presented below the graph (Cell number ranges: B6 87–661, MRL/lpr 267–1825, AID−/−MRL/lpr+PBS 181–622, AID−/−MRL/lpr+F(ab′)2 115–276, AID−/−MRL/lpr+Hy1.2 105–574, AID−/−MRL/lpr+PL2-3 2wk 225–310, AID−/−MRL/lpr+PL2-3 5wk 375–3028). Results are ± SEM from >5 experiments, n=2–5 mice per treatment per experiment. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc procedure.

In AID−/−MRL/lpr mice, the presence of TLSs and the infiltration of hematopoietic cells into the kidneys following PL2-3 treatment (Figures 1B, C) suggest that local in situ immune responses could induce renal BAFF production. Single cell suspensions of kidney cells from mice treated with PL2-3 for 5 weeks showed a 3-fold increase in the number of BAFF-secreting cells compared to PBS treatment (Figure 2B). Similar to serum BAFF, renal BAFF secretion was dependent on the binding of IgG-ICs to FcγRs since F(ab′)2 of PL2-3, or Hy1.2 did not promote BAFF secretion when compared to mice treated with PBS. This suggests that renal BAFF is also linked to FcγR and IgG-ICs.

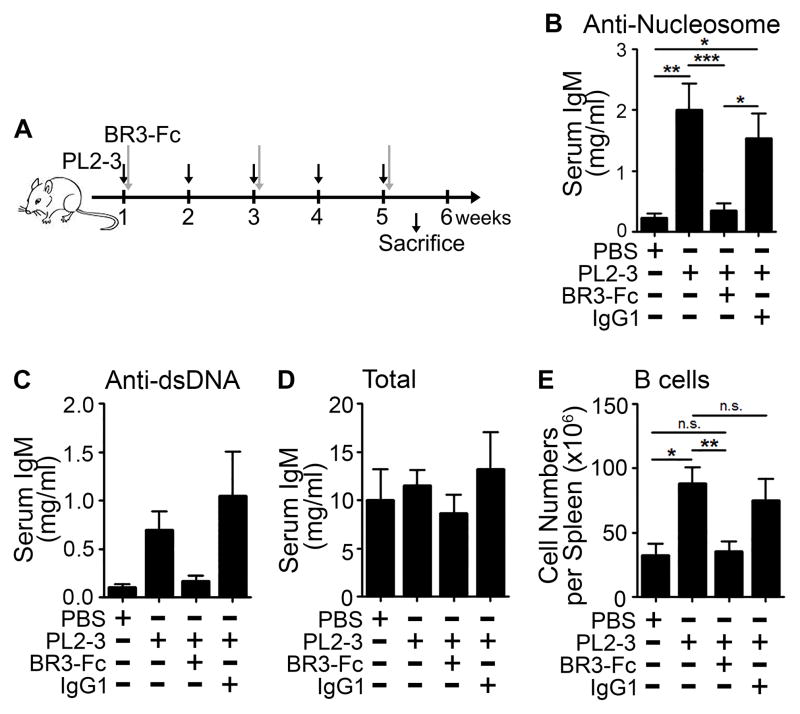

Reducing BAFF diminishes autoimmune responses and prevents lupus nephritis

Heightened levels of BAFF in the kidneys of AID−/−MRL/lpr mice following PL2-3 treatment suggest that BAFF plays a role in lupus nephritis. To assess this, we injected soluble BAFF receptor fused to the Fc portion of mouse IgG1 (BR3-Fc) into AID−/−MRL/lpr mice every other week in combination with weekly treatments of PL2-3 (Figure 3A). We titrated BR3-Fc and found that co-administration of 3.3 mg/kg of BR3-Fc significantly reduced autoantibody levels compared to mice treated with PL2-3 alone (Figure 3B, C). This was not due to B cell depletion because the numbers of splenic B cells remained comparable to those in disease-free PBS treated AID−/−MRL/lpr mice (Figure 3E). In addition, the levels of total serum IgM were unchanged (Figure 3D). A higher dose of BR3-Fc (5 mg/kg) reduced splenic B cell numbers and total IgM levels by 2-fold compared to PBS treated AID−/−MRL/lpr mice (data not shown). Thus, low dose BR3-Fc treatment was adequate to limit the expansion of autoreactive B cells induced by PL2-3 treatment. This allowed us to distinguish the effects of BAFF on lupus nephritis from secondary effects conferred by the absence of B cells.

Figure 3. Reducing BAFF levels prevents autoimmunity.

(A) AID−/−MRL/lpr mice were treated with PL2-3 (500 μg/mouse; black arrows) weekly in combination with 3.3 mg/kg of BR3-Fc or control antibody (IgG1) given every other week (gray arrows), for 5 weeks. Separate cohorts of mice were treated with PBS. (B) Serum anti-nucleosome IgM, (C) anti-dsDNA IgM, and (D) total IgM levels were measured by ELISA. (E) Splenic B cells were enumerated by flow cytometry after 5 weeks of treatment. In (B to E), results are ± SEM from 4 experiments, n=2–5 mice per treatment per experiment. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, n.s. = not significant by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc procedure.

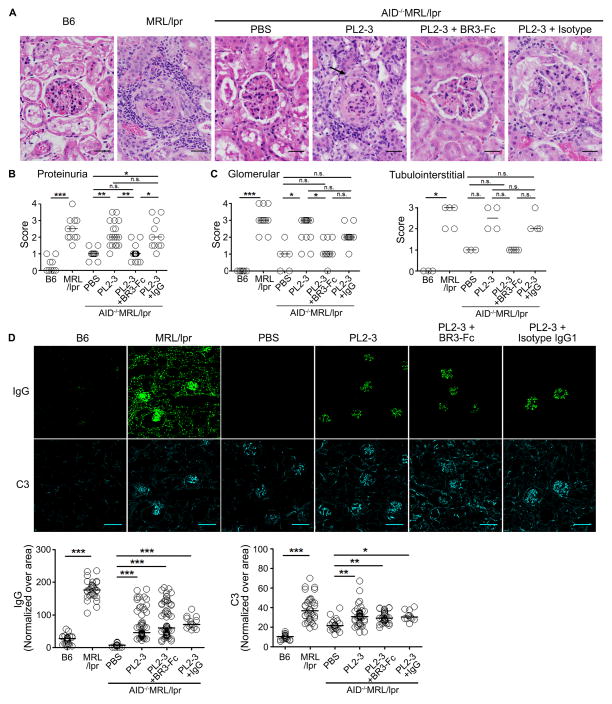

To evaluate whether BAFF plays a role in lupus nephritis, we analyzed H&E stained kidney sections. As previously reported, treatment of PL2-3 (5 weeks) severely damaged kidneys, showing the formation of fibrocellular crescents, that were comparable to MRL/lpr mice (Figure 4A, (17)). Concomitantly, PL2-3 treated mice showed increased proteinuria, glomerular, and tubulointerstitial scores that were comparable to diseased MRL/lpr mice (Figure 4B and 4C left, right panels). In contrast, co-administration of BR3-Fc (3.3 mg/kg) with PL2-3 reduced renal pathology by decreasing proteinuria, glomerular, and tubulointerstitial scores to values comparable to B6 and PBS treated AID−/−MRL/lpr mice. Consistent with these data, histology showed that mice treated with BR3-Fc exhibited limited structural damage in the kidneys (Figure 4A). In lupus, increased polarization of Th17 cells has been related to lupus nephritis (37). Further, depletion of BAFF in the synovium inhibits generation of the Th17 population coincident with improved arthritis (38). We found that T cells expressed BAFF-Rs and expression levels were unaffected by treatment (Supplemental Figure 3A, B). Heightened BAFF also increased the number of Th17 cells in the kidney (8 fold), but when BAFF was reduced, the number of Th17 cells decreased (Supplemental Figure 3C left panel). In contrast, the effects of BAFF on Th17 cells were not evident on CD4+IFNγ+ T cells (Supplemental Figure 3C right panel), suggesting that BAFF might exacerbate lupus nephritis through Th17 cells. However, although BAFF was reduced and disease was markedly ameliorated, the deposits of complement (C3) and IgG persisted (Figure 4D). When we quantified the levels of total IgG and C3 deposits per glomerulus (Figure 4D lower panels), we found that PL2-3 treatment increased the levels of IgG and C3 deposits compared to PBS treated mice. This was not due to PL2-3 binding renal antigens because injection of PL2-3 into B6 or FcγRI−/−MRL/lpr mice did not induced renal deposits of IgG (17). When BR3-Fc was co-administered with PL2-3 to reduce BAFF levels, the deposits of IgG and C3 did not change compared to PL2-3 treated mice (Figure 4D lower panels). Thus, heightened production of BAFF, induced by IgG-ICs bound to FcγRs on myeloid cells, is a primary inflammatory factor regulating lupus nephritis independent or downstream of renal deposits of IgG/C3.

Figure 4. Reducing BAFF levels prevents lupus nephritis.

(A) H&E stained kidney sections from AID−/−MRL/lpr mice treated for 5 weeks. Sections from B6 and MRL/lpr mice were shown as controls. Arrow indicates fibrocellular crescents formation. Scale bar = 25 μm. (B) Proteinuria, (C) glomerular (left panel) and tubulointerstitial (right panel) scores following 5 weeks of treatments. Each circle depicts an individual animal. (D) IgG and C3 deposits in the kidneys from AID−/−MRL/lpr mice following 5 weeks of treatments, B6, and MRL/lpr mice were assessed by immunofluorescence (upper panels). Scale bar = 140 μm. The intensity of IgG (lower left) and C3 (lower right) deposits on all the glomeruli from 2–5 sections from each mouse were measured and shown as normalized values over area. Each dot represents each glomerulus. Bars represent median and each circle represents each glomerulus. In (A and D) representative images are from >3 experiments. n=3–7 mice per treatment. In (B and C) results are from 3 experiments, n=2–5 mice per treatment per experiment, bars represent median, each circle represents each mouse. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.00, n.s. = not significant by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc procedure.

Reducing BAFF levels prevents the development of renal TLSs

Given that PL2-3 treatment promoted BAFF secretion coincident with lymphoid organogenesis in the kidneys, we reasoned that BAFF might play a role in the development of TLSs. We found that low dose BR3-Fc (3.3 mg/kg) treatment prevented the formation of TLSs (Figure 5A). Kidneys from AID−/−MRL/lpr mice treated with PL2-3 for 5 weeks showed large, compartmentalized TLSs where clusters of B cells were adjacent to the area containing T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells (Figure 1C left panel and 5A upper panel). In PL2-3 treated mice, there were 6-fold more TLSs compared to PBS treated mice (Figure 5A upper panel, Supplemental Figure 2A, 2B). Reducing BAFF levels prevented the formation of TLSs, yet many smaller clusters containing T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells were evident (Figure 5A lower panel). Compared to PL2-3 treatment, mice with reduced BAFF showed a 4-fold decrease in the number of large clusters (Supplemental Figure 2B), while the numbers of small clusters were slightly increased (Supplemental Figure 2C). These studies show a role for BAFF in the formation and/or compartmentalization of renal TLSs, and show that loss of TLSs coincides with improved renal pathology.

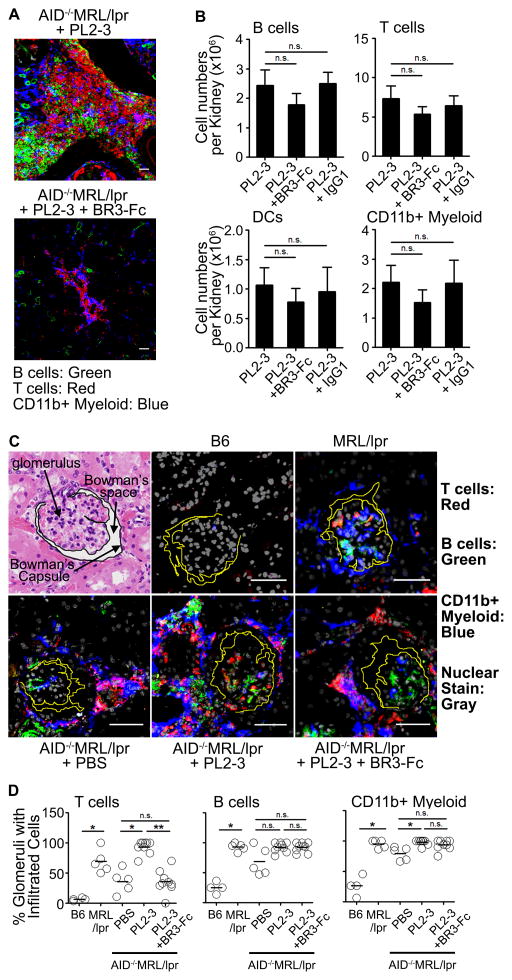

Figure 5. Lowering BAFF levels prevents renal TLSs and alters the positioning of T cells.

(A) TLSs from AID−/−MRL/lpr mice following 5 weeks of treatments were stained and imaged at 12x magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm. CD19+ B cells (Green), CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Red), CD11b+ myeloid cells (Blue). (B) Enumeration of B cells, T cells, DCs, and CD11b+ myeloid cells that infiltrated one kidney of each mouse after 5 weeks of treatment. 4 experiments, n=2–5 mice per treatment per experiment. (C) Localization of B cells (Green), T cells (Red), and CD11b+ myeloid cells (Blue) in kidneys from AID−/−MRL/lpr mice following 5 weeks of treatments or from age-matched B6, MRL/lpr mice. Gray is for nuclear stain. Images were taken at 30x magnification. Scale bar = 50 μm. The images of glomeruli were randomly captured on multiple sections of any kidneys. (D) Frequency of glomeruli containing T cells, B cells, or CD11b+ myeloid cells over total number of glomeruli counted per mouse were graphed (total of 10–40 glomeruli per mouse were randomly counted from 2–4 mice per treatment from 2 experiments). Sectioning and staining between experiments were done on different days. Each circle depicts an individual animal. In (A and C) data are from 2–3 experiments with 2–4 mice per treatment. In (B) results are ± SEM, in (D) bars represent median. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, n.s. = not significant by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc procedure.

Hematopoietic cells infiltrate the kidneys independent of BAFF

BAFF increases the chemotactic response of human B cells to CCL21, CXCL12, and CXCL13 (39). In addition, heightened BAFF could promote survival and proliferation of infiltrated B and T cells (19, 40). To address whether BAFF was important in the infiltration or expansion of cells, we assessed whether BR3-Fc treatment diminished the number of hematopoietic cells in the kidney. We found that the numbers of B cells, T cells, DCs, and CD11b+ myeloid cells that infiltrated kidneys from mice given PL2-3 + BR3-Fc were not statistically different from the mice treated with PL2-3 alone, or PL2-3 + Isotype IgG1; treatments that promoted lupus nephritis (Figure 5B and Figure 4). These data indicate that the infiltration or expansion of cells in the kidneys is independent or upstream of BAFF. Thus, the absence of B cells in the myeloid/T cell clusters that remained after BR3-Fc treatment (Figure 5A lower panel) was not due to reduced B cell numbers in the kidney.

The positioning of T cells in the glomeruli is dependent on BAFF

The data show that reducing BAFF levels prevents lupus nephritis and the development of TLSs, but not by reducing the infiltration of cells into the kidney (Figures 4, 5A and 5B). However, it does not address whether BAFF affects the positioning of immune cells within the kidneys. Using microscopy, we found that B cells, T cells, and CD11b+ myeloid cells were evenly distributed in and around the glomeruli in AID−/−MRL/lpr mice treated for 5 weeks with PL2-3 and diseased MRL/lpr mice (Figure 5C–D). In contrast, lowering BAFF levels with BR3-Fc (3.3 mg/kg) reduced the number of glomeruli that contained T cells to levels comparable to PBS treated mice. In these kidneys, T cells were exclusively positioned outside the glomeruli and around the Bowman’s capsule (Figure 5C). Despite an effect on T cells, reducing BAFF did not affect the positioning of B cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells within the glomeruli, suggesting that the events regulating the position of B cells and myeloid cells within the glomeruli might be upstream or independent of BAFF. The data show that coincident with renal inflammation and proteinuria, BAFF affects the position of T cell in the glomeruli (Figure 4, 5C and 5D). Thus, heightened BAFF, induced by the chronic binding of IgG-ICs to FcγRs on myeloid cells, contribute to lupus nephritis by inducing renal TLS and affecting the position of T cells within the glomeruli.

Discussion

Tissue-specific immune responses have been implicated in lupus nephritis; however, how they develop remains poorly understood. This study shows that during the onset of lupus nephritis, high levels of BAFF promote the formation of TLSs and increase the number of glomeruli containing T cells. We used an inducible model of lupus where passive transfer of pathogenic IgG into AID−/−MRL/lpr mice increases the levels of autoantibody and BAFF, and induces lupus nephritis (17). In this model, renal pathology was associated with elevated BAFF production from cells within the kidneys, significant renal infiltration of immune cells, development of TLSs, and glomerular deposits of IgG/C3. When BAFF levels were reduced, disease remitted coincident with loss of T cells in the glomeruli and diminished TLSs; however, the infiltration of cells to the kidney and the glomerular deposits of IgG/C3 were unaffected. Thus, BAFF plays an important role in lupus nephritis by contributing to the formation of renal TLSs and positioning of T cells within the glomerulus.

The heightened production of BAFF is a hallmark of SLE, but a mechanism explaining how BAFF becomes elevated, or how it affects lupus nephritis has not been clearly defined. Our earlier work in the AID−/−MRL/lpr model show that within 2 weeks of transferring anti-nucleosome, splenic myeloid cells accumulate surface IgG-ICs bound to activating FcγRs, and increase the number of BAFF secreting MFs (2 weeks) and DCs (5 weeks) (17). The accumulation of IgG-ICs on myeloid cells is the consequence of a lysosomal maturation defect that diminishes the degradation of IgG-ICs and induces their recycling (18); events that require FcγRI and precede the expansion of autoreactive B cells and lupus nephritis (17). In the current study, we show that the Fc portion of anti-nucleosome IgG was necessary for the infiltration of immune cells into the kidney and the production of renal BAFF, since F(ab′)2 of PL2-3 or Hy1.2 did not induce hematopoietic cell infiltration, or increase the numbers of BAFF producing cells in the kidney. This supports the idea that the interaction of IgG-ICs with FcγRs is upstream of cell infiltration. However, the infiltration of cells and IgG/C3 deposits persisted in the absence lupus nephritis when BAFF levels were reduced, indicating that hematopoietic cell infiltration into the kidney, or IgG/C3 deposits, is not sufficient for pathology. Our data suggest that the ligation of FcγR by IgG-ICs induces infiltration of hematopoietic cells into the kidney and promotes renal BAFF, is required for fulminant kidney pathology. One possible way that the accumulation of IgG-ICs on FcγRs may relate to the infiltration of immune cells into the kidney is that renal resident hematopoietic cells might be induced to secrete chemokines RANTES, MCP-1, and/or MIP-1α in response to the constant binding of IgG-ICs to activating FcγRs (41). In support of this, FcγR expression on hematopoietic cells, but not mesangial cells, is necessary for kidney pathology (16). Thus, BAFF production in the spleen (17) and kidney contributes to the pathology of SLE as a consequence of lysosomal maturation defect that promotes the accumulation of IgG-ICs (18) setting in motion immune pathology in secondary and tertiary organs.

Compartmentalization of cell clusters into properly organized structures that are anatomically reminiscent of secondary lymphoid organs is a hallmark of functionally competent TLSs (4, 5). Anatomical similarities of TLSs in non-lymphoid organs to lymphoid organs might ensure the effective immune responses at local tissues (42, 43). We found that the number of large cell clusters were increased when BAFF levels were heightened, coincident with severe glomerulonephritis and tubulointerstitial nephritis (Figure 5A upper panel and right panels). In contrast, when BAFF was reduced and mice failed to develop lupus nephritis, the numbers of small cell clusters were not different from PL2-3 treated mice (Figure 4 and 5A). Further, IgG/C3 deposition persisted (Figure 4D). This suggests that large organized TLSs, rather than small random clusters of cells or IgG/C3 deposits, serve as areas that promote or exacerbate immune responses including the in situ expansion of B cells and the development of plasmablasts reactive to renal antigens (Figure 3, Supplemental Figure 1A). These could further accelerate the formation of functional ectopic germinal centers as evidenced in human lupus (8). Moreover, the presence of FDCs, or the binding of IgG-ICs to FcγRIIB, could provide a source of intact antigen (8, 44, 45) for B cell expansion, activation, and production of lymphotoxin-α1β2, which could further organize TLS (46, 47). We also found that heightened BAFF was associated with the formation of large, compartmentalized renal TLSs. Reducing BAFF prevented the localization of B cells to the myeloid/T cell clusters, despite a constant number of total B cells infiltrating the kidney (Figures 1C, 5A, and 5B). This suggests that heightened or prolonged production of BAFF could be a key event in forming properly compartmentalized TLSs. One possibility is that small seeding clusters of CD11b+ myeloid cells secrete heightened BAFF and enhance B cell chemotactic abilities by modulating chemokine induced signaling (39), thus leading to cell aggregation and compartmentalization in the developing TLS. Activated B cells within organized TLSs (Figure 1C and 3A) may also provide a local source of autoantibody and heightened BAFF could regulate the expansion of B cells or survival of plasma cells in the kidney (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure 1A). Since heightened BAFF production and enhanced B cell responses also amplify local T cell activation (Supplemental Figure 2A and B, (48)), they might promote follicular helper T cells (Tfh) and prolong in situ germinal center responses within the renal TLSs. Further, in patients with lupus nephritis, only cognate interactions between Tfh cells and B cells induce high levels of Bcl-6 and IL21 in the renal tubulointerstitium (49). This might occur as a consequence of BAFF promoting the expression of ICOSL on activated B cells (50), and inducing the formation of Tfh cells (51, 52). Thus, renal TLSs may form in lupus nephritis as a consequence of hematopoietic cell infiltration into the kidney, but require high BAFF levels to form or maintain properly compartmentalized TLSs.

A second event identified during lupus nephritis is the ability of BAFF to alter the position of renal T cells. Studies have shown that blocking T cell costimulation (53), or neutralizing IFNγ and IL4 (54, 55) improves or delays renal pathology. Similarly, kidney biopsies from lupus patients show that T cells infiltrate and aggregate within the kidney (56). In SLE patients, the infiltration of immune cells into tubulointerstitial areas is associated with lupus nephritis (8), suggesting that the positioning of cells within kidneys is important in disease. Our findings show that the presence of T cells in the glomeruli is regulated by BAFF (Figure 5C, D). Since T cells can be activated through BAFF-R (Supplemental Figure 2A and B), their localization in the glomeruli could be a consequence of increased expression of chemokine receptors or enhanced chemokine receptor signaling in activated T cells as a consequence of BAFF-mediated activation (40). Although CXCR5 (receptor for CXCL14) and CCR7 (receptor for CCL19 and CCL21) have been implicated in the formation/organization of TLSs (57, 58), we were unable to see the changes in the expression of CCR7 or CXCR5 on T cells that infiltrated into the kidney, regardless of the treatment (data not shown). However, we have not ruled out a possibility that a small fraction of T cells positioned in the vicinity of glomeruli change the receptor levels in response to heightened BAFF, or that chemokine secretion from other cells, rather than the expression of chemokine receptors on T cells, are affected by BAFF. In patients with glomerulonephritis, CD68+ MFs are found in and around of glomeruli, while CD68+DC-SIGN+ DCs are only present inside the glomeruli (59). Thus, under conditions where BAFF is abundant, it is possible that T cells express costimulatory or adhesion molecules that allow equal interaction with DCs and MFs, while under low BAFF, the interaction of T cells may be limited with DCs outside of glomeruli.

Another mechanism whereby BAFF could promote tissue destruction is by inducing T cells to secrete inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17, IL-4, or IFNγ. Therefore, BAFF levels could affect the quality and quantity of the T-cell driven cytokines in different ways, and as a consequence, promote unique outcomes based on the cells that are activated. Others have identified that the numbers of Th17 cells in the kidney are increased in lupus-prone mice (37), that glomerular cells from mice with lupus nephritis show elevated IL-17 gene expression (60), and that BAFF contributes to the formation of Th17 cells in infection, MS, and arthritis (38, 61, 62). We found that coincident with lupus nephritis, the number of renal Th17 cells following PL2-3 treatment was increased, and this was dependent on BAFF (Supplemental Figure 2C). In contrast, the number of CD4+IFNγ+ Th1 cells, effector (CD62L−CD44+), or memory (CD62L+CD44+) T cells was unaffected (Supplemental Figure 2C, data not shown). Thus, heightened BAFF in the kidney might induce glomerular damage by positioning T cells inside the glomeruli, or possibly by inducing the formation of Th17 cells (Figure 5C, D, and Supplemental Figure 2C). Whether the position of T cells and the formation of TLSs are parallel or co-dependent processes that promote glomerulonephritis and/or tubulointerstitial nephritis remains unclear; however, our data clearly shows that BAFF induced both these renal manifestations in lupus nephritis.

Despite the availability of anti-BAFF therapy for SLE, less is known about the role of BAFF in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis. Our data indicate that in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice, renal disease is a multi-step process involving autoantibody/IgG-ICs, heightened BAFF, and the location and organization of hematopoietic cells within the kidney. Whether BAFF acts directly or indirectly to induce these events, and whether the presence of T cell within the glomeruli and formation of TLSs are necessary for renal pathology, remain unclear; however, lowering BAFF is sufficient to prevent these events concomitantly with preventing renal pathology. Therefore, our study underscores the effects of heightened BAFF on lupus nephritis, supporting the potency of anti-BAFF therapy in human lupus nephritis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank to the Flow Cytometry Core (NCI P30CA016086), the Microscopy Services Laboratory (CA 16086-26), the Histology Core Laboratory, and the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Biostatistics Core Facility for their support.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH R01AI070984, NIH R21AI105613, and Alliance for Lupus Research.

Author contribution

S-A. K. directed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; Y.F. analyzed kidney pathology; E.K.B performed experiment; Y.K.T advised on statistical analysis; K.K. provided reagents and helped writing the manuscript; B.J.V. co-directed the project and wrote the manuscript. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hu W, Pasare C. Location, location, location: tissue-specific regulation of immune responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:409–421. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0413207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bombardieri M, Barone F, Lucchesi D, Nayar S, van den Berg WB, Proctor G, Buckley CD, Pitzalis C. Inducible tertiary lymphoid structures, autoimmunity, and exocrine dysfunction in a novel model of salivary gland inflammation in C57BL/6 mice. J Immunol. 2012;189:3767–3776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astorri E, Bombardieri M, Gabba S, Peakman M, Pozzilli P, Pitzalis C. Evolution of ectopic lymphoid neogenesis and in situ autoantibody production in autoimmune nonobese diabetic mice: cellular and molecular characterization of tertiary lymphoid structures in pancreatic islets. J Immunol. 2010;185:3359–3368. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neyt K, Perros F, GeurtsvanKessel CH, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Tertiary lymphoid organs in infection and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aloisi F, Pujol-Borrell R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:205–217. doi: 10.1038/nri1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nacionales DC, Weinstein JS, Yan XJ, Albesiano E, Lee PY, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Lyons R, Satoh M, Chiorazzi N, Reeves WH. B cell proliferation, somatic hypermutation, class switch recombination, and autoantibody production in ectopic lymphoid tissue in murine lupus. J Immunol. 2009;182:4226–4236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein JS, Delano MJ, Xu Y, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Nacionales DC, Li Y, Lee PY, Scumpia PO, Yang L, Sobel E, Moldawer LL, Reeves WH. Maintenance of anti-Sm/RNP autoantibody production by plasma cells residing in ectopic lymphoid tissue and bone marrow memory B cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:3916–3927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang A, Henderson SG, Brandt D, Liu N, Guttikonda R, Hsieh C, Kaverina N, Utset TO, Meehan SM, Quigg RJ, Meffre E, Clark MR. In situ B cell-mediated immune responses and tubulointerstitial inflammation in human lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2011;186:1849–1860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun KH, Hong CC, Tang SJ, Sun GH, Liu WT, Han SH, Yu CL. Anti-dsDNA autoantibody cross-reacts with the C-terminal hydrophobic cluster region containing phenylalanines in the acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P1 to exert a cytostatic effect on the cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263:334–339. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mostoslavsky G, Fischel R, Yachimovich N, Yarkoni Y, Rosenmann E, Monestier M, Baniyash M, Eilat D. Lupus anti-DNA autoantibodies cross-react with a glomerular structural protein: a case for tissue injury by molecular mimicry. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1221–1227. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1221::aid-immu1221>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-Yehuda A, Rasooly L, Bar-Tana R, Breuer G, Tadmor B, Ulmansky R, Naparstek Y. The urine of SLE patients contains antibodies that bind to the laminin component of the extracellular matrix. J Autoimmun. 1995;8:279–291. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1995.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalaaji M, Mortensen E, Jorgensen L, Olsen R, Rekvig OP. Nephritogenic lupus antibodies recognize glomerular basement membrane-associated chromatin fragments released from apoptotic intraglomerular cells. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1779–1792. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jancar S, Sanchez Crespo M. Immune complex-mediated tissue injury: a multistep paradigm. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacob CO, Pricop L, Putterman C, Koss MN, Liu Y, Kollaros M, Bixler SA, Ambrose CM, Scott ML, Stohl W. Paucity of clinical disease despite serological autoimmunity and kidney pathology in lupus-prone New Zealand mixed 2328 mice deficient in BAFF. J Immunol. 2006;177:2671–2680. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramanujam M, Wang X, Huang W, Liu Z, Schiffer L, Tao H, Frank D, Rice J, Diamond B, Yu KO, Porcelli S, Davidson A. Similarities and differences between selective and nonselective BAFF blockade in murine SLE. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:724–734. doi: 10.1172/JCI26385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergtold A, Gavhane A, D’Agati V, Madaio M, Clynes R. FcR-bearing myeloid cells are responsible for triggering murine lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2006;177:7287–7295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang S, Rogers JL, Monteith AJ, Jiang C, Schmitz J, Clarke SH, Tarrant TK, Truong YK, Diaz M, Fedoriw Y, Vilen BJ. Apoptotic Debris Accumulates on Hematopoietic Cells and Promotes Disease in Murine and Human Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Immunol. 2016;196:4030–4039. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteith AJ, Kang S, Scott E, Hillman K, Rajfur Z, Jacobson K, Costello MJ, Vilen BJ. Defects in lysosomal maturation facilitate the activation of innate sensors in systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E2142–2151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513943113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mackay F, Woodcock SA, Lawton P, Ambrose C, Baetscher M, Schneider P, Tschopp J, Browning JL. Mice transgenic for BAFF develop lymphocytic disorders along with autoimmune manifestations. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1697–1710. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancro MP, Smith SH. Peripheral B cell selection and homeostasis. Immunol Res. 2003;27:141–148. doi: 10.1385/IR:27:2-3:141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scholz JL, Oropallo MA, Sindhava V, Goenka R, Cancro MP. The role of B lymphocyte stimulator in B cell biology: implications for the treatment of lupus. Lupus. 2013;22:350–360. doi: 10.1177/0961203312469453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramanujam M, Bethunaickan R, Huang W, Tao H, Madaio MP, Davidson A. Selective blockade of BAFF for the prevention and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus nephritis in NZM2410 mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1457–1468. doi: 10.1002/art.27368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan OT, Hannum LG, Haberman AM, Madaio MP, Shlomchik MJ. A novel mouse with B cells but lacking serum antibody reveals an antibody-independent role for B cells in murine lupus. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1639–1648. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincent FB, Morand EF, Mackay F. BAFF and innate immunity: new therapeutic targets for systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:293–303. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furie R, Stohl W, Ginzler EM, Becker M, Mishra N, Chatham W, Merrill JT, Weinstein A, McCune WJ, Zhong J, Cai W, Freimuth W G. Belimumab Study. Biologic activity and safety of belimumab, a neutralizing anti-B-lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) monoclonal antibody: a phase I trial in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:R109. doi: 10.1186/ar2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navarra SV, Guzman RM, Gallacher AE, Hall S, Levy RA, Jimenez RE, Li EK, Thomas M, Kim HY, Leon MG, Tanasescu C, Nasonov E, Lan JL, Pineda L, Zhong ZJ, Freimuth W, Petri MA, Group BS. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:721–731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang C, Foley J, Clayton N, Kissling G, Jokinen M, Herbert R, Diaz M. Abrogation of lupus nephritis in activation-induced deaminase-deficient MRL/lpr mice. J Immunol. 2007;178:7422–7431. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Losman MJ, Fasy TM, Novick KE, Monestier M. Monoclonal autoantibodies to subnucleosomes from a MRL/Mp(−)+/+ mouse. Oligoclonality of the antibody response and recognition of a determinant composed of histones H2A, H2B, and DNA. J Immunol. 1992;148:1561–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilbert MR, Wagner NJ, Jones SZ, Wisz AB, Roques JR, Krum KN, Lee SR, Nickeleit V, Hulbert C, Thomas JW, Gauld SB, Vilen BJ. Autoreactive preplasma cells break tolerance in the absence of regulation by dendritic cells and macrophages. J Immunol. 2012;189:711–720. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Churg J, Sobin LH. Renal disease classification and atlas of glomerular diseases. Igaku-Shoin; Tokyo; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, Balow JE, Bruijn JA, Cook T, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Ginzler EM, Hebert L, Hill G, Hill P, Jennette JC, Kong NC, Lesavre P, Lockshin M, Looi LM, Makino H, Moura LA, Nagata M N International Society of Nephrology Working Group on the Classification of Lupus, and N. Renal Pathology Society Working Group on the Classification of Lupus. The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. Kidney Int. 2004;65:521–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bethunaickan R, Davidson A. Process and Analysis of Kidney Infiltrates by Flow Cytometry from Murine Lupus Nephritis. Bio-protocol. 2012;2:e167. [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Agati VD, Appel GB, Estes D, Knowles DM, 2nd, Pirani CL. Monoclonal antibody identification of infiltrating mononuclear leukocytes in lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 1986;30:573–581. doi: 10.1038/ki.1986.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bloom DD, Davignon JL, Retter MW, Shlomchik MJ, Pisetsky DS, Cohen PL, Eisenberg RA, Clarke SH. V region gene analysis of anti-Sm hybridomas from MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mice. J Immunol. 1993;150:1591–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armengol MP, Juan M, Lucas-Martin A, Fernandez-Figueras MT, Jaraquemada D, Gallart T, Pujol-Borrell R. Thyroid autoimmune disease: demonstration of thyroid antigen-specific B cells and recombination-activating gene expression in chemokine-containing active intrathyroidal germinal centers. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:861–873. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61762-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boule MW, Broughton C, Mackay F, Akira S, Marshak-Rothstein A, Rifkin IR. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent and -independent dendritic cell activation by chromatin-immunoglobulin G complexes. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1631–1640. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Z, Cuda CM, Croker BP, Morel L. The NZM2410-derived lupus susceptibility locus Sle2c1 increases Th17 polarization and induces nephritis in fas-deficient mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:764–774. doi: 10.1002/art.30146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai Kwan Lam Q, King Hung Ko O, Zheng BJ, Lu L. Local BAFF gene silencing suppresses Th17-cell generation and ameliorates autoimmune arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14993–14998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806044105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badr G, Borhis G, Lefevre EA, Chaoul N, Deshayes F, Dessirier V, Lapree G, Tsapis A, Richard Y. BAFF enhances chemotaxis of primary human B cells: a particular synergy between BAFF and CXCL13 on memory B cells. Blood. 2008;111:2744–2754. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huard B, Schneider P, Mauri D, Tschopp J, French LE. T cell costimulation by the TNF ligand BAFF. J Immunol. 2001;167:6225–6231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anders HJ, Vielhauer V, Schlondorff D. Chemokines and chemokine receptors are involved in the resolution or progression of renal disease. Kidney Int. 2003;63:401–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones GW, Jones SA. Ectopic lymphoid follicles: inducible centres for generating antigen-specific immune responses within tissues. Immunology. 2016;147:141–151. doi: 10.1111/imm.12554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carragher DM, Rangel-Moreno J, Randall TD. Ectopic lymphoid tissues and local immunity. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:26–42. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qin D, Wu J, Vora KA, Ravetch JV, Szakal AK, Manser T, Tew JG. Fc gamma receptor IIB on follicular dendritic cells regulates the B cell recall response. J Immunol. 2000;164:6268–6275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki K, Grigorova I, Phan TG, Kelly LM, Cyster JG. Visualizing B cell capture of cognate antigen from follicular dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1485–1493. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen P, Fillatreau S. Antibody-independent functions of B cells: a focus on cytokines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:441–451. doi: 10.1038/nri3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tumanov AV, Kuprash DV, Mach JA, Nedospasov SA, Chervonsky AV. Lymphotoxin and TNF produced by B cells are dispensable for maintenance of the follicle-associated epithelium but are required for development of lymphoid follicles in the Peyer’s patches. J Immunol. 2004;173:86–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ng LG, Sutherland AP, Newton R, Qian F, Cachero TG, Scott ML, Thompson JS, Wheway J, Chtanova T, Groom J, Sutton IJ, Xin C, Tangye SG, Kalled SL, Mackay F, Mackay CR. B cell-activating factor belonging to the TNF family (BAFF)-R is the principal BAFF receptor facilitating BAFF costimulation of circulating T and B cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:807–817. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liarski VM, Kaverina N, Chang A, Brandt D, Yanez D, Talasnik L, Carlesso G, Herbst R, Utset TO, Labno C, Peng Y, Jiang Y, Giger ML, Clark MR. Cell distance mapping identifies functional T follicular helper cells in inflamed human renal tissue. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:230ra246. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu H, Wu X, Jin W, Chang M, Cheng X, Sun SC. Noncanonical NF-kappaB regulates inducible costimulator (ICOS) ligand expression and T follicular helper cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12827–12832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105774108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coquery CM, Loo WM, Wade NS, Bederman AG, Tung KS, Lewis JE, Hess H, Erickson LD. BAFF regulates follicular helper t cells and affects their accumulation and interferon-gamma production in autoimmunity. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:773–784. doi: 10.1002/art.38950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang S, Keener AB, Jones SZ, Benschop RJ, Caro-Maldonado A, Rathmell JC, Clarke SH, Matsushima GK, Whitmire JK, Vilen BJ. IgG-Immune Complexes Promote B Cell Memory by Inducing BAFF. J Immunol. 2016;196:196–206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schiffer L, Sinha J, Wang X, Huang W, von Gersdorff G, Schiffer M, Madaio MP, Davidson A. Short term administration of costimulatory blockade and cyclophosphamide induces remission of systemic lupus erythematosus nephritis in NZB/W F1 mice by a mechanism downstream of renal immune complex deposition. J Immunol. 2003;171:489–497. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng SL, Moslehi J, Craft J. Roles of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in murine lupus. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1936–1946. doi: 10.1172/JCI119361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haas C, Ryffel B, Le Hir M. IFN-gamma is essential for the development of autoimmune glomerulonephritis in MRL/Ipr mice. J Immunol. 1997;158:5484–5491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winchester R, Wiesendanger M, Zhang HZ, Steshenko V, Peterson K, Geraldino-Pardilla L, Ruiz-Vazquez E, D’Agati V. Immunologic characteristics of intrarenal T cells: trafficking of expanded CD8+ T cell beta-chain clonotypes in progressive lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1589–1600. doi: 10.1002/art.33488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schulz O, Hammerschmidt SI, Moschovakis GL, Forster R. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors in Lymphoid Tissue Dynamics. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:203–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wengner AM, Hopken UE, Petrow PK, Hartmann S, Schurigt U, Brauer R, Lipp M. CXCR5- and CCR7-dependent lymphoid neogenesis in a murine model of chronic antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3271–3283. doi: 10.1002/art.22939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Segerer S, Heller F, Lindenmeyer MT, Schmid H, Cohen CD, Draganovici D, Mandelbaum J, Nelson PJ, Grone HJ, Grone EF, Figel AM, Nossner E, Schlondorff D. Compartment specific expression of dendritic cell markers in human glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2008;74:37–46. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y, Ito S, Chino Y, Iwanami K, Yasukochi T, Goto D, Matsumoto I, Hayashi T, Uchida K, Sumida T. Use of laser microdissection in the analysis of renal-infiltrating T cells in MRL/lpr mice. Mod Rheumatol. 2008;18:385–393. doi: 10.1007/s10165-008-0074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou X, Xia Z, Lan Q, Wang J, Su W, Han YP, Fan H, Liu Z, Stohl W, Zheng SG. BAFF promotes Th17 cells and aggravates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Munari F, Fassan M, Capitani N, Codolo G, Vila-Caballer M, Pizzi M, Rugge M, Della Bella C, Troilo A, D’Elios S, Baldari CT, D’Elios MM, de Bernard M. Cytokine BAFF released by Helicobacter pylori-infected macrophages triggers the Th17 response in human chronic gastritis. J Immunol. 2014;193:5584–5594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.