Abstract

Background

Synuclein-γ (SNCG) is highly expressed in advanced solid tumors, including in uterine serous carcinoma (USC). The goal was to determine if SNCG protein was associated with survival and clinical covariates using the largest existing collection of USC from the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG-8023).

Methods

High-density tissue microarrays (TMAs) of tumor tissues of 313 patients with USC were stained by immunohistochemistry (IHC) for SNCG, p53, p16, FOLR1, pERK, pAKT, ER, PR, and HER2/neu. Association of SNCG and other tumor markers with overall and progression-free survival was assessed using Logrank tests and Cox proportional hazards models including adjustment for age, race, and stage.

Results

Overall survival at 5 years was 46% for high and 62% for low SNCG expression groups (logrank p=0.021, hazard ratio [HR]=1.31, 95% confidence interval [CI]= 0.91-1.9 in adjusted Cox model). Progression free survival at 5 years was worse for high SNCG at 40% compared to 56% for low SNCG (logrank p=0.0081, [HR]=1.36, 95% [CI]= 0.96-1.92 in adjusted Cox model). High levels of both p53 and p16 were significantly associated with worse overall survival (p53: [HR]=4.20, 95% [CI]=1.54-11.45; p16: [HR]= 1.95, 95% [CI]=1.01-3.75) and progression-free survival (p53: [HR]= 2.16, 95% [CI]=1.09-4.27; p16: ([HR]= 1.53, 95% [CI]=0.87-2.69) compared to low levels.

Conclusions

This is the largest collection of USC cases to date demonstrating that SNCG was associated with poor survival in USC in univariate analyses. SNCG does not predict survival outcome independently of p53 and p16 in models that jointly consider multiple markers.

Keywords: Endometrial cancer, Uterine Serous Carcinoma, SNCG, p53, p16

BACKGROUND

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States with an estimated 54,870 cases in 2015 1. Despite an overall good prognosis, survival varies dramatically depending upon the histologic subtype. Although uterine serous carcinoma (USC) accounts for about 10% of endometrial cancers, prognosis is substantially worse than the more common endometrioid adenocarcinoma, with frequent recurrences and high mortality rates 2, 3. Active treatment modalities remain elusive as neither its pathogenesis nor the nature of its aggressive behavior and chemoresistance are well understood.

Synuclein-γ (SNCG) has been demonstrated to be overexpressed in USC 4-6. SNCG is a member of the synuclein (SNC) family of proteins that are small, soluble, highly conserved neuronal proteins, implicated in both neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. SNCG overexpression occurs in multiple cancers including colon, gastric, pancreatic, ovarian, and lung cancer 7-14. SNCG was first termed breast cancer-specific gene 1 (BCSG1) as it was shown to be correlated with poor prognosis and advanced stage in breast cancer 7, 10. The mechanisms by which SNCG promotes advanced disease and chemoresistance have been shown to involve modulating the mitogen-activated kinases (MAPKs), extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) 15. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that SNCG interferes with paclitaxel-induced mitotic arrest by interacting with the mitotic checkpoint kinase BubR1 resulting in the inability of preventing cells with misaligned chromosomes from exiting mitosis 16. Additional studies are necessary to define the role of SNCG in USC.

We first identified SNCG expression specifically in USC through a pathway focused expression array, followed by correlative analysis of SNCG expression with survival in 20 USC patients 6. While statistical significance was not reached due to a limited sample size, a trend for an association of SNCG with decreased progression-free survival was evident. In a larger study evaluating 279 endometrial carcinomas with varying histologies, of which 46 were USC, SNCG expression was positive in tumors with worse overall outcome, especially in clear cell, serous, and carcinosarcoma histologies 5. These data strongly suggest that SNCG may be a prognostic biomarker for USC.

The objective of this study was to determine if SNCG protein was associated with clinicopathologic variables and patient outcomes in a sufficiently large collection of USC tumors. The associations of SNCG and other tumor markers, including p53 and p16, with multiple clinical parameters including survival were determined. This is the largest collection of USC cases to date representing 313 women with USC obtained from the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG), through its clinical trial programs.

METHODS

Patient Selection

As described in the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study GOG-8023, women with USC who were eligible for and enrolled in GOG-0210 (a molecular staging study17), who had consented for future research and had histologically confirmed USC were included for TMA construction. If there was insufficient tissue submitted on GOG 210, then tissue collected on another study, GOG-0136 (a specimen banking study) was used. The diagnosis of USC was reviewed for each case by the GOG Pathology Committee. Research specimens were reviewed by the study pathologists to confirm that primary tumor consisted of at least 90% serous carcinoma. The presence of any non-serous histologic components was noted, but the histology in all cases was considered consistent with USC overall.

Clinical data

Overall survival was defined as observed length of life from study entry to death. Progression was defined as increasing clinical, radiologic, or histologic evidence of disease after study entry, and progression-free survival was defined as the time from study entry to the date of disease recurrence, progression, or death (whichever occurred first). Lengths of follow-up from study entry until date of last contact for women without death or progression were treated as censored observations for overall survival and progression-free survival analyses, respectively. Types of adjuvant therapy were recorded using the following general terms: chemotherapy, radiation therapy, chemo-radiation, hormonal therapy, other treatment regimen, or none. Additional details were recorded when appropriate. Other variables examined were age (at study entry), race, FIGO 1988 surgical stage (I-II vs. III-IV), presence or absence of lymphovascular space invasion, depth of myometrial invasion (none, <50%, ≥50%, serosal involvement), involvement of pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes, and presence or absence of pelvic disease, abdominal disease, peritoneal disease and distant disease.

Tissue Microarray

A high-density tissue microarray (TMA) was created by the GOG Tissue Bank, which consisted of four 10×10 grids of 0.6 mm tissue cores, positioned as four quadrants on one microarray. Each 10×10 grid included 90 randomly positioned USC patient tissues as well as 10 control tissues (5 normal human tissues, 5 human cancer tissues). Of the 90 tumors, 47 were represented in duplicate for a total of 313 patient tumors represented in the TMA. There were four replicate tissue microarrays.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses were performed for the following biomarkers: SNCG, estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), p53, HER2/neu, folate receptor 1 (FOLR1), p16, pAKT, and pERK. Immunostains for all except HER2/neu were performed at the GOG Tissue Bank housed at the Biopathology Center, part of the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital under the supervision of Dr. Nilsa Ramirez. Immunostaining for HER2/neu was performed at the Pathology Core Facility of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, under the supervision of Dr. Jian-Jun Wei. The details for each antibody are summarized in Table 1. All antibodies were tested on negative and positive control tissues provided by both the Northwestern Human Pathology Core and the GOG Tissue Bank.

Table 1.

Antibody assay characteristics

| Antibody | Source | Clone | Dilution | Antigen Retrieval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNCG | Abcam | EP1539Y | 1:500 | TRS |

| ER | Dako | 1D5 | 1:600 | TRS |

| PR | Dako | PgR 636 | 1:10 | TRS |

| p53 | Dako | DO-7 | 1:50 | TRS |

| HER2/neu | Dako | A0485 Polyclonal |

1:1000 | Decloaking chamber, pH6 |

| p16 | Ventana | E6H4 | 1:600 | CC1 |

| P(S473)-AKT | Abcam | Polyclonal | 1:100 | TRS |

| p(Y204)-ERK | Abcam | Polyclonal | 1:200 | TRS |

| FOLR1 | Leica Microsystems | BN3.2 | 1:50 | EDTA |

TRS: Target Retrieval Solution,

CC1: Cell Condition 1;

EDTA: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

To validate the immunostains, each biomarker was also assessed in conventional blocks from 10% of the cases to confirm that the expression of each biomarker in the 0.6 mm cores was representative of the expression in full tissue sections. A semiquantitative immunoreactivity for all markers was scored by two pathologists. All immunostains except HER2/neu were scored by intensity (1+, 2+, or 3+) and by percent of tumor cells staining (0, 1-10%, 11-20%, 21-30%, 31-40%, 41-50%, 51-60%, 61-70%, 71-80%, 81-90%, 91-100%). HER2/neu was scored as 0, 1+, 2+, or 3+ based on the 2007 scoring criteria established for breast cancer 18. Marker definitions for each of the included biomarkers are delineated in Table 2. For SNCG, intensity and percentage scores were initially combined into overall scores of low, medium, and high. The “low” category was defined as no staining (0%) or as 1+ intensity with ≤ 20% cells staining. The “medium” category was defined as 1+ intensity with >20% cells staining, or 2-3+ intensity with 1-50% cells staining. The “high” category was defined as 2-3+ intensity with >50% cells staining. For p53, “high” category was defined as >30% with any intensity or 0% labeling index (dead negative, indicative of null mutation).

Table 2.

Marker expression pattern definitions

| Marker | Expression pattern definitions (%, intensity) | Expression patterns included |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High expression | Medium expression |

Low expression | ||

| SNCG | >20%, 2+/3+ | >20%, 1+, or 1-50%, 2+/3+ |

≤ 20%, 0/1+ | Cytoplasmic + Nuclear |

| ER | >10%, any intensity |

NA | 0%, or ≤10%, any intensity |

Nuclear |

| PR | >10%, any intensity |

NA | 0%, or ≤10%, any intensity |

Nuclear |

| p53 | >30%, any intensity, or 0% labeling index |

NA - | 1-30%, any intensity |

Nuclear |

| p16 | >50%, any intensity |

NA | ≤50%, any intensity |

Nuclear + cytoplasmic |

| pAKT | >50%, 1+, or >20%, 2+/3+ |

NA | ≤50%, 1+, or ≤20%, 2+/3+ |

Membranous + cytoplasmic |

| pERK | >50%, 1+, or >20%, 2+/3+ |

NA | ≤50%, 1+, or ≤20%, 2+/3+ |

Nuclear + cytoplasmic |

| FOLR1 | >10%, any intensity |

NA | ≤10%, any intensity |

Membranous |

| HER2/neu* | Positive (Score 3+) |

Equivocal (Score 2+) |

Negative (Score 0 or 1+) |

Membranous |

Scoring for Her2/neu was based on the 2007 scoring criteria recommended for breast cancer [15]

NA=not applicable

The final immunoscores for SNCG, p53, and pAKT were given based on the most frequent score of quadruplicate tissue cores. When this algorithm was inconclusive, the raw data were reviewed and a representative summary score was determined. For the remaining markers, only one TMA reading was performed. Upon initial analysis for SNCG staining, it was observed that survival curves were similar for “medium” and “high” groups. Thus, these categories were combined into one “high” category, resulting in two SNCG expression groups (“low” and “high”) that were subsequently used for analysis.

Power Considerations

The study was originally designed to include three SNCG expression groups (low, medium, high). Across a range of SNCG expression group distributions, a total sample size of 300 afforded 80% power at 5% two-sided Type I error and 10% loss-to-follow up to detect overall survival hazard ratios of 0.46-0.56 for low versus medium SNCG expression and 1.63-1.81 for high versus medium SNCG expression depending on the size of the low, medium and high groups 19. A target sample size of 360 for TMA construction was set to allow for potential core loss. In our analyses, due to similarity of effect estimates, the medium and high expression groups were combined for analysis. In post-hoc power calculations, our observed sample sizes in the SNCG expression groups yielded 80% power at 5% two-sided Type I error to detect a hazard ratio of roughly 1.62 for the high v. low SNCG expression group.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical and biomarker variables were summarized using the mean and standard deviation for age and tables of frequencies and counts for all other categorical variables. SNCG expression was the primary predictor of interest. Analyses were initially conducted using three SNCG expression categories as planned. Few differences in survival distributions and hazard functions were observed in all analyses for the original medium and high expression groups, hence these two categories were combined and two SNCG expression groups (high vs low) were used for final analyses (Table 3). Secondary predictors of interest were expression of FOLR1, pERK, pAKT, p53, p16, ER, and PR (all high vs low), as well as HER2/neu expression (positive, negative, or equivocal). The primary outcome was overall survival (time in months) and the secondary outcome was progression-free survival (time in months).

Table 3.

Marker expression frequencies

| Low n (%) |

High n (%) |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNCG | 115 (38.2%) | 186 (61.8%) | 301 |

| p53 | 42 (13.6%) | 267 (86.4%) | 309 |

| p16 | 35 (12.2%) | 252 (87.8%) | 287 |

| FOLR1 | 104 (37.0%) | 177 (63.0%) | 281 |

| pERK | 237 (82.0%) | 52 (18.0%) | 289 |

| pAKT | 264 (85.7%) | 44 (14.3%) | 308 |

| PR | 184 (63.5%) | 106 (36.6%) | 290 |

| ER | 171 (59.2%) | 118 (40.8%) | 289 |

| Negative n(%) | Equivocal n(%) | Positive n(%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HER2/neu^ | 299 (95.5%) | 7 (2.2%) | 7 (2.2%) | 313 |

Since the sample sizes for HER2/neu are so small, survival analyses are not reported.

Age, race, surgical stage, presence of lymph-vascular space invasion, depth of myometrial invasion, pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph node involvement, pelvic disease, abdominal disease, peritoneal disease, distant disease, and adjuvant treatment were all summarized to describe the patient population and examined for association with SNCG expression using a t-test for age and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Clinical characteristics demonstrating association with SNCG expression group at p<0.05 were included in Cox proportional hazards models to assess potential confounding in SNCG associations with time to event outcomes.

Kaplan-Meier curves for overall survival and progression-free survival were generated for both SNCG groups. Logrank tests were used to assess differences between the curves. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios and adjustments for age, race and stage were examined in Cox models. The same process was used for all tumor markers of secondary interest. Hazard ratios were estimated in multiple marker models for SNCG and p16 as well as SNCG and p53.

RESULTS

SNCG in Uterine Serous Carcinoma

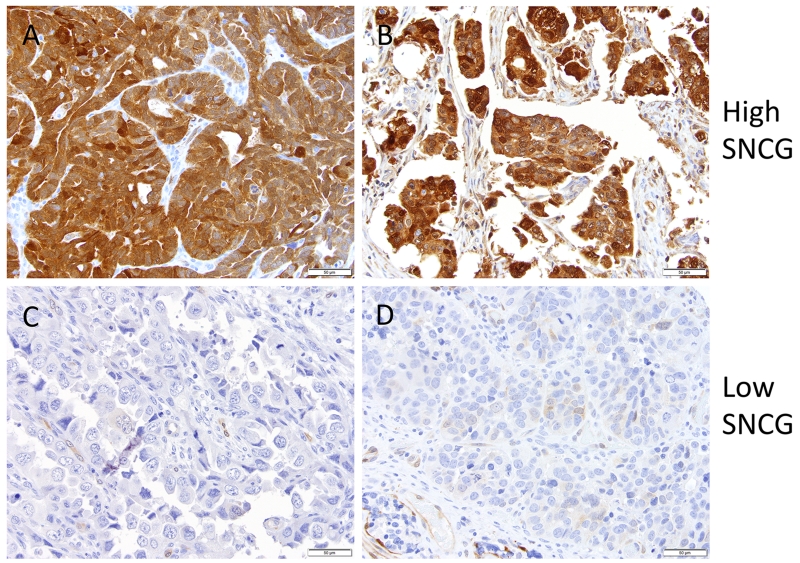

USC tumors from patients enrolled in GOG-0210, were collected and tissue microarrays were constructed by the GOG Tissue Bank (http://www.nationwidechildrens.org/biopathology-center-collaborations). Clinical data and adequate tissue specimens were available for analysis from 313 patients. Immunostaining for SNCG revealed a variable extent (focal/patchy to extensive/diffuse) and intensity of staining, localized predominantly to the cytoplasm of tumor cells with occasional nuclear staining (Fig 1). The staining was categorized as high and low based on intensity of staining and the percentage of cells stained (Table 2; low=0-1 intensity with ≤20% of tumor cells staining; high= 2-3 intensity or >20% of tumor cells staining). High expression of SNCG was seen in 61.8% of cases (Table 3). The mean age at diagnosis was statistically significantly different with 67.2 years for low and 69.8 years for high SNCG expression (p = 0.01; Table 4). Surgical stage, histologic heterogeneity, the presence of lymphovascular space invasion, depth of myometrial invasion, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node metastasis, the presence of pelvic, abdominal, peritoneal or distant disease, and the type of adjuvant treatment were similar across the SNCG groups. While no differences in SNCG expression were observed according to race or stage, these covariates were included along with age in adjusted models due to known associations with overall survival.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of SNCG in tumor cores in the USC TMA. Two representative sections of A,B) high and C,D) low expression are shown. Brown color represents positive SNCG staining.

Table 4.

Patient characteristics

| All Patients n=313 |

Low SNCG n=115 |

High SNCG n=186 |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean and sd) | 68.7 (8.6) | 67.2 (9.0) | 69.8 (8.1) | 0.01 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 217 (74.3%) | 88 (79.3%) | 129 (71.3%) | 0.33 |

| Black | 70 (24.0%) | 22 (19.8%) | 48 (26.5%) | |

| Other | 5 (1.7%) | 1 (0.9%) | 4 (2.2%) | |

| FIGO 1988 Surgical Stage | ||||

| Stage 1-2 | 154 (49.2%) |

61 (53.0%) | 85 (45.7%) | 0.22 |

| Stage 3-4 | 159 (50.8%) |

54 (47.0%) | 101 (54.3%) |

|

| Diagnostic Pathology Review Classification |

||||

| Pure Serous Carcinoma | 239 (76.4%) |

83 (72.3%) | 145 (78.0%) |

0.18 |

| Serous with Endometrioid Features (indeterminate) |

42 (13.4%) | 15 (13.0%) | 26 (14.0%) | |

| Other | 32 (10.2%) | 17 (14.8%) | 15 (8.1%) | |

| Malignant cells in vascular lymphatic space |

||||

| Absent | 169 (55.0%) |

65 (58.0%) | 97 (53.0%) | 0.40 |

| Present | 138 (45.0%) |

47 (42.0%) | 86 (47.0%) | |

| Depth of myometrial invasion | ||||

| None | 64 (20.9%) | 16 (14.2%) | 42 (23.1%) | 0.25 |

| <50% | 119 (38.8%) |

50 (44.3%) | 66 (36.3%) | |

| >50% | 105 (34.2%) |

41 (36.3%) | 63 (34.6%) | |

| Serosa | 19 (6.2%) | 6 (5.3%) | 11 (6.0%) | |

| Pelvic and/or paraaortic nodal metastisis |

||||

| None | 177 (63.2%) |

76 (69.7%) | 101 (59.1%) |

0.15 |

| Pelvic only | 37 (13.2%) | 10 (9.2%) | 27 (15.8%) | |

| Paraaortic with or without positive pelvic nodes |

66 (23.6%) | 23 (21.1%) | 43 (25.2%) | |

| Pelvic disease | ||||

| No | 210 (71.4%) |

87 (77.7%) | 123 (67.6%) |

0.06 |

| Yes | 84 (28.6%) | 25 (22.3%) | 59 (32.4%) | |

| Abdominal disease | ||||

| No | 222 (81.6%) |

85 (86.7%) | 137 (78.7%) |

0.10 |

| Yes | 50 (18.4%) | 13 (13.3%) | 37 (21.3%) | |

| Peritoneal disease | ||||

| No | 210 (70.2%) |

86 (74.8%) | 124 (67.4%) |

0.17 |

| Yes | 89 (29.8%) | 29 (25.2%) | 60 (32.6%) | |

| Distant disease | ||||

| No | 151 (98.0%) |

54 (98.2%) | 91 (97.9%) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 3 (2.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 2 (2.2%) | |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 122 (51.1%) |

46 (50%) | 70 (51.1%) | 0.40 |

| Radiation | 27 (11.3%) | 8 (8.7%) | 19 (13.9%) | |

| Chemotherapy and radiation |

90 (37.7%) | 38 (41.3%) | 48 (35.0%) |

P-values are for comparisons of characteristics across low and high SNCG expression groups. Student’s t-test was used for comparison of age. All other categorical comparisons were evaluated using chi-square tests, except for depth of myometrial invasion and distant disease, which used Fisher’s exact test.

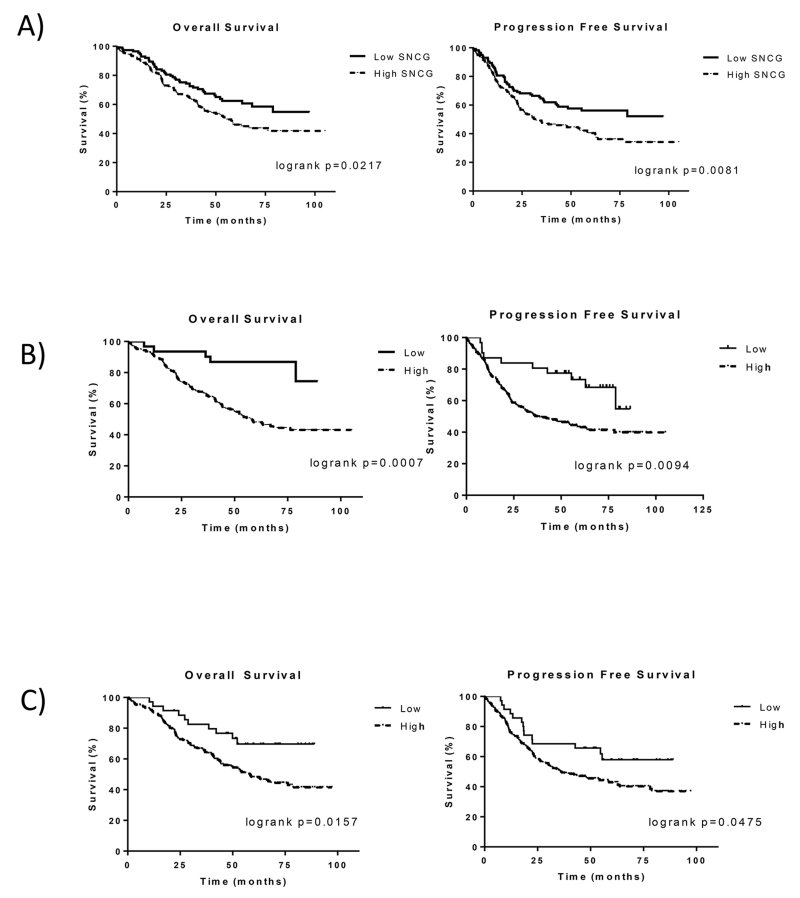

In unadjusted analyses, overall survival was statistically significantly worse for women whose tumors demonstrated high SNCG expression (Fig 2, Table 5, logrank test p=0.021). At 5 years, the overall survival estimates were 62% for those with low SNCG expressing cancers and 46% for those with high expression of SNCG. The association between SNCG and overall survival was attenuated in adjusted Cox models with a hazard ratio of 1.31 (95% CI: 0.91-1.9, p=0.15) after adjusting for age, race and stage. Progression-free survival was also statistically significantly lower for women with tumors that had high SNCG expression in unadjusted analyses (Fig 2, Table 5; logrank test, p=0.0081). At 3 years, 63% of women with low SNCG expression were progression-free compared to 47% of women with high expression. This was also seen at 5 years with a progression-free survival of 56% and 40% for low and high SNCG groups, respectively. The Cox model hazard ratio adjusted for age, race, and stage favored low SNCG expression (HR = 1.36 for high v. low expression, 95% CI 0.96-1.92, p=0.086). The Kaplan–Meier plots illustrate lower survival for high SNCG compared to low SNCG expression (Fig 2). Trends were similar when survival was examined for white race and black race separately (Suppl Fig 1).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with USC stratified according to A) SNCG, B) p53 and C) p16 expression (high versus low). Statistically and clinically significant differences were observed between the groups for both overall survival and progression-free survival.

Table 5.

SNCG expression and survival estimates

| SNCG | n (n events) |

Overall survival | Logrank p-value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI, p) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year | 3-years | 5-years | 0.021 | 1.31 (0.91-1.9, 0.15) |

||

| High | 186 (93) | 0.89 | 0.66 | 0.46 | ||

| Low | 115 (43) | 0.94 | 0.73 | 0.62 | ||

| Progression-free survival | ||||||

| 1-year | 3-years | 5-years | 0.0081 | 1.36 (0.96-1.92, 0.086) |

||

| High | 186 (109) | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.40 | ||

| Low | 115 (49) | 0.81 | 0.63 | 0.56 | ||

Overall and progression-free survival estimates were evaluated based on high and low SNCG expression levels with a logrank test. The hazard ratio compared high versus low SNCG expression and is adjusted for age, race, and stage with a 95% confidence interval and p value.

Association of other tumor markers in USC

We next sought to determine the expression pattern of other known molecular markers in endometrial cancer and associations with progression and survival outcomes. The TMAs were stained for p53, p16, FOLR1, pERK, pAKT, PR, ER, and HER2/neu and scored as high or low (Suppl Fig 2, Suppl Fig 3, Table 3). As summarized in Table 3, more than 50% of the patients had high immunoreactivity of SNCG, p53, p16, and FOLR1. HER2/neu was positive in only 2.2% of USC cases and negative in over 95% of these samples. Less than 20% of cases exhibited high immunoreactivity for pERK and pAKT while the majority (> 80%) had low levels. Both ER and PR immunoreactivity were low in more than half of the cases.

Among the markers tested, only p53 and p16 were significantly associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes. Women whose cancer demonstrated high p53 expression had worse overall survival (HR=4.2, 95% CI 1.54-11.45, p=0.005) and disease progression (HR=2.16, 95% CI 1.09-4.27, p=0.027) (Table 6A). Trends were also evident for tumors with high p16 expression associated with worse overall survival (HR=1.95, 95% CI 1.01-3.75, p=0.046) and progression free survival (HR=1.53, 95% CI 0.87-2.69, p=0.14) (Table 6A). Expression levels of p16 and p53 were associated with each other with about 92% of tumors with high p53 expression also demonstrating high p16 expression (p<0.0001). Cox models using multiple markers were also examined to determine whether the association of SNCG with overall survival and progression-free survival was independent of p53 and p16 associations. In Cox models including SNCG and p53 as well as age, race, and stage, associations of SNCG with the outcomes were attenuated and no longer statistically significant, with hazard ratio of 1.19 (95% CI 0.81-1.73, p=0.37) for overall survival and 1.27 (95% CI 0.89-1.81, p=0.19) for progression-free survival. When SNCG and p16 were included in a model together, associations with overall and progression-free survival were attenuated and not statistically significant for both markers. Nevertheless, over 90% of high SNCG tumors also had high p53 and/or p16 expression (Table 6B). The expression of FOLR1, pERK, pAKT, PR, and ER and the hazard ratios for these markers were not statistically significant (Table 7).

Table 6A.

p53 and p16 expression relationship to survival

| n (n events) |

Overall survival | Logrank p-value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI, p) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year | 3-years | 5-years | 0.0008 | 4.20 (1.54-11.45, 0.005) |

|||

| p53 | High | 267 (130) | 0.90 | 0.66 | 0.48 | ||

| Low | 42 (9) | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.80 | |||

| p16 | High | 252 (124) | 0.90 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.016 | 1.95 (1.01-3.75, 0.046) |

| Low | 35 (10) | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.70 | |||

| Progression-free survival | |||||||

| 1-year | 3-years | 5-years | 0.0092 | 2.16 (1.09-4.27, 0.027) |

|||

| p53 | High | 267 (147) | 0.78 | 0.50 | 0.42 | ||

| Low | 42 (15) | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.71 | |||

| p16 | High | 252 (141) | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.048 | 1.53 (0.87-2.69, 0.14) |

| Low | 35 (14) | 0.89 | 0.69 | 0.58 | |||

Overall and progression free survival estimates based on high and low p53 and p16 expression with a logrank test. The hazard ratio compared high versus low expression and is adjusted for age, race, and stage with a 95% confidence interval and p value.

Table 6B.

Associations between significant markers

| p53 Low |

p53 High |

p16 Low |

p16 High |

p16 Low |

p16 High |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNCG Low |

23 (0.20) |

92 (0.80) |

SNCG Low |

24 (0.22) |

84 (0.78) |

p53 Low |

19 (0.54) |

16 (0.46) |

| SNCG High |

16 (0.09) |

170 (0.91) |

SNCG High |

11 (0.06) |

168 (0.94) |

p53 High |

19 (0.08) |

233 (0.92) |

| p=.00042 | p<.0001 | p<.0001 | ||||||

Data represent counts. The values in parentheses are row percentages. P values indicate whether association between high and low expression of pairs of markers is statistically significant

Table 7.

Hazard ratios for the additional markers

| HR | FOLR1 | pERK | pAKT | PR | ER | |

| OS | 1.04 (0.72-1.51, 0.84) |

1.10 (0.68-1.76, 0.70) |

1.00 (0.63-1.58, 0.99) |

0.82 (0.57-1.19, 0.30) |

0.92 (0.65-1.32, 0.66) |

|

| PFS | 1.16 (0.81-1.64, 0.42) |

1.22 (0.80-1.85, 0.37) |

1.09 (0.73-1.65, 0.67) |

.78 (0.55-1.09, 0.15) |

.90 (0.65-1.25, 0.52) |

The hazard ratio compared high versus low expression of each marker and is adjusted for age, race, and stage with a 95% confidence interval and p value.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of USC is rare accounting for only 10% of newly diagnosed endometrial cancers. It is, however, one of the most aggressive tumors of the endometrium, with high recurrence and associated mortality rates 2, 3. Active treatment modalities remain elusive, as neither its pathogenesis nor its chemoresistance is well understood. A third to one half of USC tumors are admixed with other histologic subtypes,20 although recent literature based on data from The Cancer Genome Atlas indicates that the morphologic reproducibility of carcinomas with mixed or ambiguous histology is poor, and POLE-ultramutated endometrioid carcinomas in particular may be morphologically misdiagnosed as USC 21, 22. Notwithstanding this newer data, however, morphology-based studies have found that even when the USC component contributes as little as 10% to the tumor, its behavior can resemble pure serous carcinoma 23. A significant limitation to studying USC is the small number of cases that can be collected at any one institution. The Gynecologic Oncology Group with the cooperation of multiple centers has collected thousands of endometrial cancer samples through various clinical trial protocols. Specifically, USC tumor specimens used in this study were collected and banked as part of the clinical trials, GOG-0210 and GOG-0136. As a result, 313 USC cases with adequate tumor represented on the TMA and detailed clinical information were available for this study, representing the largest collection of USC tumors with corresponding clinical information available for investigation to date. The statistical study design planned the sample size to have 80% statistical power at 5% Type I error with 10% loss to follow-up to detect hazard ratios of 0.46-0.56 for low versus medium SNCG expression and 1.63-1.81 for high versus medium SNCG expression in the original three group design. The study results revealed a statistically significant association between SNCG expression and overall as well as progression-free survival in univariate analyses. In addition, given the size of this cohort, standardized criteria for a relatively reliable cut-off score for SNCG to allow for interpretation of immunoreactivity for SNCG could be established. Consistent with a recent study 4, a score of low and high expression of SNCG is a reproducible approach to interpreting IHC score of SNCG in USC. Further validation of technical methodology and interpretation criteria will be needed before widespread adoption of SNCG IHC staining as a diagnostic or prognostic marker.

According to our study, the survival of women with high expression of SNCG was worse, despite no statistically significant association between SNCG expression and certain clinical parameters at the time of a uterine serous carcinoma diagnosis, including stage, depth of myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, and nodal metastasis. Unadjusted analyses demonstrated a statistically significant association between SNCG expression and overall and progression-free survival, although associations were attenuated after adjustment for age, race and stage. Additional investigations with larger sample size may clarify associations since observed hazard ratios for both time-to-event outcomes in these data were slightly lower than those we were adequately powered to detect. USC is an aggressive malignancy with early intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal spread even in the absence of traditional risk factors, such as deep myometrial invasion, tumor size, and lymphovascular space invasion (3). Thus SNCG may be associated with mechanisms related to this unique spread pattern. However, there is still much to be learned regarding the genes and pathways that permit metastasis preferentially into the abdominal and peritoneal cavities.

Molecular studies have implicated SNCG to be involved in chemoresistance. It was shown that SNCG bound to a spindle checkpoint kinase, BubR1, thereby inducing a structural change of BubR1. This inhibited its kinase activity as well as attenuated its interaction with other key checkpoint proteins such as Cdc20, compromising the spindle assembly checkpoint 16, 24, 25. The lack of checkpoint function would allow cells to override G2/M arrest with aneuploidy proliferation to perpetuate genomic instability. By targeting SNCG with a specific peptide, sensitivity to paclitaxel was enhanced 26. Association of SNCG with clinical chemoresistance was not assessed in this study due to insufficient information and remains an unanswered question. Most women in this study received some form of adjuvant therapy and the distribution of chemotherapy, pelvic radiotherapy, or both were similar in both the low and high SNCG expression groups. The use of SNCG as a marker for chemoresistance is a plausible option that should be explored.

The association of SNCG with other tumor markers was examined in this study. Among the markers tested, only p53 and p16 were associated with overall survival and progression-free survival. To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort that demonstrates the association of p53 or p16 with survival in USC, providing evidence of the prognostic potential of these two markers. Only one study demonstrated p53 to be significantly associated with worse survival in 34 cases of USC 27 while association studies of p16 and survival in USC have not been reported, underscoring the relevance of our study of 313 cases of USC. High versus low expression of the other markers, pAKT, pERK, ER, PR, and FOLR1, was not significantly associated with survival. The expression of pAKT, pERK, ER, PR, and FOLR1 has been studied extensively in endometrioid carcinoma, but their role in USC is less understood. ER has been shown to associate with SNCG which increases transcriptional activity of ER to mediate estrogen driven proliferation in the mammary gland 28-30. SNCG can stimulate membrane-initiated estrogen signaling to stimulate growth and promote tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells 30. The data as to whether ER contributes to the aggressive nature of USC are sparse even though USC is distinct from endometrioid adenocarcinoma with regards to hormone-dependence. An analysis of 71 USC cases in Japan demonstrated an overall and progression-free survival advantage with positive hormone receptor status 31. However, in our study, neither ER nor PR was associated with survival outcomes. In our study, we grouped IHC staining for ER and PR as high versus low expression whereas the Japanese study compared hormone positive (either ER or PR are expressed) versus negative for either ER or PR. Nevertheless, in our study, 40% and 36% of USC cases expressed high levels of ER and PR, respectively. It remains to be studied whether ER and PR actively influence USC behavior. Signaling pathways including AKT and MAPK have been implicated in driving metastasis and chemoresistance in tumors 32-36 and, therefore, were markers of interest in this study. Moreover, SNCG has been shown to maintain pAKT and mTOR activities protecting cells from the cytotoxicity related to disabling Hsp90 37. Similarly, SNCG protected HER2/neu function rendering it resistant to Hsp90 mediated toxicity 38. In this study, although each of these markers was not independently associated with survival, it is possible they may play a role in resistance to treatments as chemoresistance was not part of the analysis in this study. HER2/neu is amplified in a wide range of cases from 10% to 65% depending on the study 39-42. In our study, staining of HER2/neu was low. Of note, this study employed breast cancer criteria for scoring HER2/neu expression in USC, as specific criteria for scoring HER2/neu in USC have not yet been established. One study reported that screening for HER2/neu with IHC overestimated the number of cases showing HER2/neu gene amplification as there was significant discordance between IHC and in situ hybridization 43. Clinical relevance of HER2/neu in USC is also not entirely clear as some studies have shown association with poor overall survival in patients with type II endometrial cancer and specifically USC 39, 44 while others have demonstrated no association with survival 41. Survival analysis for HER2/neu expression could not be done in this study due to the low number of tumors that exhibited staining. Additional testing with in situ hybridization staining along with IHC would be a more accurate measure of the positive cases.

In summary, this study demonstrated a statistically significant association of SNCG with poor survival outcomes in USC in unadjusted analyses, with some attenuation of the association after adjustment for age, race and stage. Levels of p53 and p16 were also significantly associated with worse survival. In analyses of multiple markers, SNCG did not demonstrate statistically significant association after adjustment for p53 or p16; hence, these data do not support SNCG as an independent predictor of survival outcomes. However, the association of SNCG with markers of advanced disease merit further investigation of its role in USC biology or as a predictive biomarker. Unlike p53 or p16, SNCG has been detected in the serum of patients harboring tumors 9, 14, 45, 46. A serum biomarker along with other tumor markers could aid in earlier diagnosis or recurrence. Additionally, the role of SNCG in predicting chemoresistance remains to be studied. Finally, this study reports the largest collection of USC cases with clinical information showing that SNCG, p53 and p16 are associated with worse survival outcome. This resource can be used to study other promising tumor marker candidates for this rare uterine cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding : This study was supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Administrative Office (CA 27469), Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical Office (CA 37517), Gynecologic Oncology Group Tissue Bank (U10 CA27469, U24 CA114793, and U10 CA 180868), NRG Oncology Group Grant 1 U10 CA180822 and NRG Oncology Operations Grant U10CA180868. The following Gynecologic Oncology Group member institutions participated in the primary treatment studies: Roswell Park Cancer Institute, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Duke University Medical Center, Abington Memorial Hospital, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Wayne State University, University of Minnesota Medical School, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Colorado Gynecologic Oncology Group P.C., University of California at Los Angeles, University of Washington, University of Pennsylvania Cancer Center, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Indiana University School of Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, University of California Medical Center at Irvine, Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center, Magee Women’s Hospital, University of New Mexico, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Washington University School of Medicine, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Cooper Hospital/University Medical Center, Columbus Cancer Council, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Women’s Cancer Center, University of Oklahoma, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, University of Chicago, Mayo Clinic, Case Western Reserve University, Tampa Bay Cancer Consortium, Yale University, University of Wisconsin Hospital, Women and Infants Hospital, The Hospital of Central Connecticut, GYN Oncology of West Michigan, PLLC, Aurora Women’s Pavilion of West Allis Memorial Hospital, University of California, San Francisco-Mt. Zion and Community Clinical Oncology Program, University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System.

This work was also funded by National Cancer Institute grant R21CA135467 (JJK). We thank the GOG for constructing and providing the TMAs, and the immunohistochemical staining. We thank the Pathology Core Facility at Northwestern University for assistance in HER2/neu immunostain.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization: Barbara Buttin, Denise M. Scholtens, Virginia L. Filiaci, J. Julie Kim

Formal Analysis: Abigail D. Winder, Kruti P. Maniar, Jian-Jun Wei, Dachao Liu, Denise M. Scholtens, J. Julie Kim

Resources: Jian-Jun Wei, Heather A. Lankes, Nilsa C. Ramirez, Kay Park, Meenakshi Singh, Richard W. Lieberman, Robert S. Mannel, Matthew A. Powell, Floor J. Backes, Cara A. Mathews, Michael L. Pearl, Angeles Alvarez Secord, David J. Peace, David G. Mutch, William T. Creasman

Writing Original Draft: Abigail D. Winder, Kruti P. Maniar, Denise M. Scholtens, J. Julie Kim,

Writing – Review & Editing: Abigail D. Winder, Kruti P. Maniar, Jian-Jun Wei, Denise M. Scholtens, John R. Lurain, Julian C. Schink, Barbara Buttin, Virginia L. Filiaci, J. Julie Kim, Heather A. Lankes, Nilsa C. Ramirez, Kay Park, Meenakshi Singh, Richard W. Lieberman, Robert S. Mannel, Matthew A. Powell, Floor J. Backes, Cara A. Mathews, Michael L. Pearl, Angeles Alvarez Secord, David J. Peace, David G. Mutch, William T. Creasman

Supervision: Jian-Jun Wei, Denise M. Scholtens, John R. Lurain MD1, Julian C. Schink, Barbara Buttin, J. Julie Kim

Funding Acquisition: Barbara Buttin, Virginia L. Filiaci, J. Julie Kim, Heather A. Lankes, Nilsa C. Ramirez, Kay Park, Meenakshi Singh, Richard W. Lieberman, Robert S. Mannel, Matthew A. Powell, Floor J. Backes, Cara A. Mathews, Michael L. Pearl, Angeles Alvarez Secord, David J. Peace, David G. Mutch, William T. Creasman

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greggi S, Mangili G, Scaffa C, et al. Uterine papillary serous, clear cell, and poorly differentiated endometrioid carcinomas: a comparative study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:661–667. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182150c89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton CA, Cheung MK, Osann K, et al. Uterine papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas predict for poorer survival compared to grade 3 endometrioid corpus cancers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:642–646. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong DG, Park NY, Chong GO, et al. The correlation between expression of synuclein-gamma, glucose transporter-1, and survival outcomes in endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2013;34:128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Wang D, Syriac S, et al. Synuclein-gamma (SNCG) protein expression is associated with poor outcome in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan J, Hoekstra AV, Chapman-Davis E, Hardt JL, Kim JJ, Buttin BM. Synuclein-gamma (SNCG) may be a novel prognostic biomarker in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu K, Weng Z, Tao Q, et al. Stage-specific expression of breast cancer-specific gene gamma-synuclein. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:920–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu C, Dong B, Lu A, et al. Synuclein gamma predicts poor clinical outcome in colon cancer with normal levels of carcinoembryonic antigen. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:359. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwaki H, Kageyama S, Isono T, et al. Diagnostic potential in bladder cancer of a panel of tumor markers (calreticulin, gamma -synuclein, and catechol-o-methyltransferase) identified by proteomic analysis. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:955–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu K, Huang S, Zhu M, et al. Expression of synuclein gamma indicates poor prognosis of triple-negative breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:612. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0612-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C, Ma H, Qu L, Wu J, Meng L, Shou C. Elevated serum synuclein-gamma in patients with gastrointestinal and esophageal carcinomas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:2222–2227. doi: 10.5754/hge12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Jiao L, Xu C, et al. Neural protein gamma-synuclein interacting with androgen receptor promotes human prostate cancer progression. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:593. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tastekin D, Kargin S, Karabulut M, et al. Synuclein-gamma predicts poor clinical outcome in esophageal cancer patients. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:11871–11877. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z, Sclabas GM, Peng B, et al. Overexpression of synuclein-gamma in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:58–65. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan ZZ, Bruening W, Giasson BI, Lee VM, Godwin AK. Gamma-synuclein promotes cancer cell survival and inhibits stress- and chemotherapy drug-induced apoptosis by modulating MAPK pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35050–35060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta A, Inaba S, Wong OK, Fang G, Liu J. Breast cancer-specific gene 1 interacts with the mitotic checkpoint kinase BubR1. Oncogene. 2003;22:7593–7599. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinton LA, Felix AS, McMeekin DS, et al. Etiologic heterogeneity in endometrial cancer: evidence from a Gynecologic Oncology Group trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Schwartz JN, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:118–145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoenfeld DA. The asymptotic properties of nonparametric tests for comparing survival distributions. Biometrika. 1981;68:316–319. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roelofsen T, van Ham MA, Wiersma van Tilburg JM, et al. Pure compared with mixed serous endometrial carcinoma: two different entities? Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1371–1381. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e318273732e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussein YR, Broaddus R, Weigelt B, Levine DA, Soslow RA. The Genomic Heterogeneity of FIGO Grade 3 Endometrioid Carcinoma Impacts Diagnostic Accuracy and Reproducibility. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016;35:16–24. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussein YR, Weigelt B, Levine DA, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of endometrial carcinomas harboring somatic POLE exonuclease domain mutations. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:505–514. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quddus MR, Sung CJ, Zhang C, Lawrence WD. Minor serous and clear cell components adversely affect prognosis in “mixed-type” endometrial carcinomas: a clinicopathologic study of 36 stage-I cases. Reprod Sci. 2010;17:673–678. doi: 10.1177/1933719110368433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inaba S, Li C, Shi YE, Song DQ, Jiang JD, Liu J. Synuclein gamma inhibits the mitotic checkpoint function and promotes chromosomal instability of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;94:25–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-6938-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao S, Wu K, Zhang B, et al. Synuclein gamma compromises spindle assembly checkpoint and renders resistance to antimicrotubule drugs. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:699–713. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh VK, Zhou Y, Marsh JA, et al. Synuclein-gamma targeting peptide inhibitor that enhances sensitivity of breast cancer cells to antimicrotubule drugs. Cancer Res. 2007;67:626–633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urabe R, Hachisuga T, Kurita T, et al. Prognostic significance of overexpression of p53 in uterine endometrioid adenocarcinomas with an analysis of nuclear grade. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:812–819. doi: 10.1111/jog.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang Y, Liu YE, Goldberg ID, Shi YE. Gamma synuclein, a novel heat-shock protein-associated chaperone, stimulates ligand-dependent estrogen receptor alpha signaling and mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4539–4546. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang Y, Liu YE, Lu A, et al. Stimulation of estrogen receptor signaling by gamma synuclein. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3899–3903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi YE, Chen Y, Dackour R, et al. Synuclein gamma stimulates membrane-initiated estrogen signaling by chaperoning estrogen receptor (ER)-alpha36, a variant of ER-alpha. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:964–973. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Togami S, Sasajima Y, Oi T, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic impact of human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 (HER2) and hormone receptor expression in uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:926–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He J, Xie N, Yang J, et al. siRNA-Mediated Suppression of Synuclein gamma Inhibits MDA-MB-231 Cell Migration and Proliferation by Downregulating the Phosphorylation of AKT and ERK. J Breast Cancer. 2014;17:200–206. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2014.17.3.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang X, Fraser M, Moll UM, Basak A, Tsang BK. Akt-mediated cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer: modulation of p53 action on caspase-dependent mitochondrial death pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3126–3136. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gagnon V, Mathieu I, Sexton E, Leblanc K, Asselin E. AKT involvement in cisplatin chemoresistance of human uterine cancer cells. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mansouri A, Ridgway LD, Korapati AL, et al. Sustained activation of JNK/p38 MAPK pathways in response to cisplatin leads to Fas ligand induction and cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19245–19256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang G, Xiao X, Rosen DG, et al. The biphasic role of NF-kappaB in progression and chemoresistance of ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2181–2194. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang W, Miao S, Zhang B, et al. Synuclein gamma protects Akt and mTOR and renders tumor resistance to Hsp90 disruption. Oncogene. 2015;34:2398–2405. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao Y, Wang B, Shi D, et al. Synuclein gamma protects HER2 and renders resistance to Hsp90 disruption. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:1521–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konecny GE, Santos L, Winterhoff B, et al. HER2 gene amplification and EGFR expression in a large cohort of surgically staged patients with nonendometrioid (type II) endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:89–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slomovitz BM, Lu KH. Commenting on “HER2/neu overexpression: has the Achilles’ heel of uterine serous papillary carcinoma been exposed? (88:263-5) by Santin AD”. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:386–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.10.013. author reply 387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh P, Smith CL, Cheetham G, Dodd TJ, Davy ML. Serous carcinoma of the uterus-determination of HER-2/neu status using immunohistochemistry, chromogenic in situ hybridization, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction techniques: its significance and clinical correlation. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:1344–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santin AD, Bellone S, Van Stedum S, et al. Amplification of c-erbB2 oncogene: a major prognostic indicator in uterine serous papillary carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:1391–1397. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mentrikoski MJ, Stoler MH. HER2 immunohistochemistry significantly overestimates HER2 amplification in uterine papillary serous carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:844–851. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santin AD, Bellone S, Siegel ER, et al. Racial differences in the overexpression of epidermal growth factor type II receptor (HER2/neu): a major prognostic indicator in uterine serous papillary cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu C, Qu L, Lian S, et al. Unconventional secretion of synuclein-gamma promotes tumor cell invasion. FEBS J. 2014;281:5159–5171. doi: 10.1111/febs.13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu C, Guo J, Qu L, et al. Applications of novel monoclonal antibodies specific for synuclein-gamma in evaluating its levels in sera and cancer tissues from colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:148–158. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.