Abstract

Naive CD4 T cell responses, especially their ability to help B cell responses, become compromised with aging. We find that using APC pre-treated ex vivo with TLR agonists, polyI:C and CpG, to prime naive CD4 T cells in vivo, restores their ability to expand and become germinal center T follicular helpers and enhances B cell IgG antibody production. Enhanced helper responses are dependent on IL-6 production by the activated APC. Aged naive CD4 T cells respond sub-optimally to IL-6 compared to the young, such that higher doses are required to induce comparable signaling. Pre-activating APC overcomes this deficiency. Responses of young CD4 T cells are also enhanced by pre-activating APC with similar effects but with only partial IL-6 dependency. Strikingly, introducing just the activated APC into aged mice significantly enhances otherwise compromised antibody production to inactivated influenza vaccine. These findings reveal a central role for production of IL-6 by APC during initial cognate interactions in the generation of effective CD4 T cell help, which becomes greater with age. Without APC activation aging CD4 T cell responses shift towards IL-6-independent Th1 and ThCTL responses. Thus, strategies that specifically activate and provide antigen to APC could potentially enhance Ab mediated protection in vaccine responses.

Introduction

With increasing age, immune responses in both mice and humans become progressively compromised (1, 2). In the elderly, naïve T and B cells make less effective responses to new antigens, resulting in greater morbidity and mortality after infection with novel pathogens or new strains of recurrent pathogens. Many current vaccines induce only low titers of long-lived Ab and little T cell memory in the elderly, rendering them more susceptible to infection. The great impact of poor vaccine efficacy in aged humans is that despite widespread influenza immunization, the incidence of heart attacks, stroke and other lethal events in the elderly closely follow the annual outbreaks of influenza infection (3).

Multiple changes in aged naive CD4 T cells contribute to their poor response. The size of the naive CD4 T cell pool declines due to a marked reduction in new thymic emigrants caused by thymic involution (4, 5) and the T cell receptor (TcR) repertoire becomes smaller (6–8). The remaining aged naive CD4 T cells make less IL-2, proliferate less and give rise to fewer CD4 effectors with impaired function (1, 2, 9–11). CD4 helper function, necessary for B cell Ab response (12) is particularly compromised in aged mice, explaining in part the generation of fewer IgG antibody (Ab)-producing B cells and long-lived antibody (Ab) (13, 14). In addition, the generation of T and B cell memory from aged naive cells is highly compromised (15, 16). Many of the naïve CD4 T cells defects that develop are cell-intrinsic and a consequence of increased cellular age, rather than the effect of the aged host environment (11, 16–18), making it challenging to develop reasonable interventions for the defects. One cause of aged naive CD4 defects seems to be their reduced responsiveness to TcR triggering (10, 19, 20). While the existence and impact of these defects is well documented, the molecular basis of their reduced function that could provide clues for overcoming defects, remains poorly understood (11, 14, 21).

Given the key role of Tfh in B cell responses (22), it is important to determine whether the reduced helper CD4 function of naive CD4 T cells might be reversed or overcome by strategies that enhance their initial response. Naïve T cells require a strong cognate interaction with antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DC-APC) which must include T cell receptor (TcR) triggering via recognition of antigen (Ag) presented by MHC, interactions of CD28 on the naïve cell with CD80/CD86 on the DC and also third signals from cytokines secreted by the DC (23). These three types of signals synergize to drive activation, division, survival, the programming of effectors to produce different patterns of cytokine production and may as well influence further differentiation and memory generation (24). Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1 (24) and TNF, especially in combination, provide important early signals to naive CD4 T cells (25), and can induce both better CD4 effector response (26) and superior help from aged naive CD4 T cells when introduced systemically (27). These three cytokines are prominent among those induced by Toll-Like Receptor (TLR)-triggering of APC, including the DC that cross-present IAV and other viruses (28, 29). TLR signaling also induces costimulatory ligands and higher levels of MHC Class II on APC that optimize Ag presentation. While there is some impairment of DC function with age, TLR activation can often enhance APC function and cytokine production in both aged mice and humans (30, 31).

A drawback to using TLR agonist adjuvants in the aged is that when administered systemically, they act pleiotropically on innate immune cells and lymphocytes (29, 32) and drive non-Ag-specific immune activation and local and possibly systemic release of inflammatory cytokines (33–35). Though adjuvants have been shown to increase efficacy of various vaccines, in the aged their use is of particular concern because inflammation and pro-inflammatory cytokines are already elevated by a phenomenon called “inflammaging” that is associated with senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) and contributes to age-associated diseases (1, 36, 37). As a result, most current vaccines for the aged are formulated without adjuvants and this correlates with their poor efficiency.

Previously, we examined the potential of TLR-activated DC (designated hereafter *DC) to enhance in vitro responses of aged naive CD4 T cells (31). The ex vivo activated *DC were superior APC for aged CD4 T cells, enhancing their expansion and effector generation. We have suggested that aging causes naive CD4 T cells to become more dependent on strong co-stimulatory or pro-inflammatory cytokine signals and that this contributes to their poor anti-IAV responses (38). However, whether these pathways can enhance aged naïve CD4 T cell function in vivo and the mechanisms involved have not been established. We postulate that if we provide more signals from activated APC in a vaccine model, we might enhance critical functions of aged naive CD4 T cells, including their helper function for B cell response (38, 39). We also reason that if we use TLR agonists to activate *DC in vitro and then used them as the APC (*DC-APC) in vivo, we could focus the adjuvant effect directly on the Ag-specific naive CD4 T cells. Here we test these hypotheses in an in vivo influenza vaccine model.

We analyzed whether IAV peptide-pulsed *DC as APC, could enhance aged naive CD4 T cell responses to inactivated IAV (IIV) in vivo. Since inactivated virus cannot replicate, it has limited, though still detectable, TLR agonist activity (40). We find that in CD4 helper-deficient hosts, the *DC, compared to non-activated DC, drove the co-transferred, IAV-specific aged naïve CD4 T cells to expand more and to develop into more IAV-specific T follicular helper cells (Tfh), germinal center (GC)-Tfh and effectors producing IL-21. In addition, the *DC-APC drove increased GC B cell (GCB) generation and production of IAV-specific IgG Ab to IAV, even though the added APC expressed only the viral epitope seen by the CD4 T cells. We find that *DC enhanced both young and aged naive CD4 T cell expansion and helper function. Importantly, we show that IL-6 which is made by the *DC during *DC:T cell interaction, is critical for the GC Tfh, B cell responses and IL-21-producing Th, but not for generation of Th1 effectors or CD4 cytotoxic effectors. We found that IL-6 signaling of aged, compared to young, naïve CD4 T cells is quantitatively reduced, so that higher IL-6 levels are needed for a comparable response. We suggest that high, directly delivered levels of IL-6, are a central factor for generating optimal helper CD4 T cell responses that in turn drive the IgG Ab response and that this requirement is higher in the aged. Confirming this, we show that by increasing IL-6 via TLR-agonist activation of the DC used as APC, it is possible to broadly improve aged as well as young naïve CD4 responses in situ. We also found enhanced responses adding *DC-APC to non-transgenic aged vs. young mice. Even in the aged mice the *DC-APC drove a substantial enhanced, long-lived IgG Ab response. As predicted the *DC-APC effect was restricted to the Ag-specific CD4 T cells, and so is expected to cause little if any systemic non-Ag-specific inflammation and immunopathology.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Naive CD4+ T cells were purified from young (5–8 wk old) and aged (14–18 months old) HNT.Thy1.1/Thy1.2 mice on a BALB/c background. The HNT TcR recognizes amino acids 126–138 (HNTNGVTAACSHE) of PR8 HA (41).

The mice were bred and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at UMass Medical School. Recipients of cell transfers include 8–10 wk old DO11.10 TcR Tg mice that were obtained from Taconic Biosciences (Germantown, NY), CD4 KO or intact BALB/cByJ mice bred at UMass from breeders obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). BMDC were derived from either BALB/c ByJ or from Il6−/− BALB/c ByJ, both obtained from Jackson Laboratory. All experimental animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the University of Massachusetts Medical School Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines and those from NIH.

Virus Infection

A/PR8/34 influenza virus (H1N1) (PR8) was produced by the Swain and Dutton laboratories at the Trudeau Institute, Saranac Lake NY. The original viral stock was provided by Allen Harmsen (Trudeau Institute), and virus was grown in the allantoic cavity of embryonated chicken eggs. Mice were infected intra-nasally under light isoflurane anesthesia (Webster Veterinary Supply).

Isolation of young and aged CD4 T cells

CD4 T cells were purified from the spleens of HNT TCR Tg mice as previously described (42). In brief, young and aged CD4 T cells were enriched using magnetic separation with anti-CD4 beads according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and then stained with PECy7–anti-CD4 (Affymetrix eBioscience, San Diego, CA) (RM4–5), FITC–anti-CD44 (Affymetrix eBioscience) (IM7), APC–anti-CD62L (Affymetrix eBioscience) (MEL-14), and PE–anti-Vβ8.3 (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) (1B3.3). Naive CD4 HNT T cells were sorted to be CD4+Vβ8.3+CD44loCD62Lhi using a MoFlo XDP Sorter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) or FACSAria Sorter (BD Bioscience). The purity of sorted CD4 naïve T cell populations was ≥95%.

Phenotypic analysis by FACS

For flow cytometric analysis, cells were suspended in PBS supplemented with 2% BSA and 0.1% NaN3 and incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated Abs for 30 min on ice and in the dark. Cells were either analyzed immediately or fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde or permeabilized with different permeabilizing reagents. The flurochrome-conjugated mAb used for studying DC were specific for CD11c-APCCy7 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), (N418), CD80-Pacific Blue (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) (16-10A1), CD86-APC (Affymetrix eBioscience, San Diego, CA), (GL1), CD40-PE (Biolegend), (3/23). To study CD4 T cell responses we looked at CD4-AF780 (Affymetrix eBioscience), (RM4–5), Thy1.1-efluor450 (Affymetrix eBioscience), (HIS51), PD1-PECy7 (Biolegend), (29F.1A12), CXCR5-PerCPCy5.5 (BD Biosciences), (2G8), GL7-AF488 (BD Biosciences), (GL7) and ICOS-APC (Affymetrix eBioscience), (C398.4A). B cell responses were characterized by looking at CD19-PECy7 (Affymetrix eBioscience), (1D3), B220-PerCP (Biolegend), (RA3–6132), Fas-PE (BD Biosciences), (J02), PNA-FITC (Sigma), (L7831), and GL7-APC (BD Biosciences), (GL7).

For Intracellular cytokine staining, splenocytes were stimulated for 4hrs with PMA (20ng/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and Ionomycin (1ug/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich). Brefeldin A (10ug/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added after 2hrs of stimulation. 2hrs later, cells were stained with surface markers and then fixed with BD Biosciences Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit. Then, the fixed and permed cells were stained for intracellular cytokines. Antibodies used for ICCS were as follows: IL-2-PE (Affymetrix eBioscience), (JES6-5H4), IFNγ-PerCPCy5.5 (BD Biosciences), (B27), IL-17-PE (BD Biosciences), (TC11–18H10), and IL-21-Unconjugated (BD Biosciences), (I76–539), with Goat anti-mouse-AF488 (Thermofisher Life Technology), (S32357). In IL-6 signaling experiments expression of IL-6Rα-PE (CD126) (Affymetrix eBioscience ), (D7715A7), and GP130-APC (CD130) (Affymetrix eBioscience), (KGP130), markers were determined as were levels of pSTAT3 with AF647 (BD Biosciences), (4/P-STAT3). Flow cytometric data were acquired on LSR2 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) cytometer using FACS DIVA (BD Biosciences) software. Analysis of flow cytometric data was done using FlowJo version 6.1.1 software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Measurement of IL-6 Signaling

Young or aged sorted naïve CD4 T cells were plated in 96 well plates (2×105 per well) and treated with increasing doses of IL-6 (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5, and 5 ng/ml). Cells were collected after 3 hours and stained for surface markers IL-6Rα and GP130 (43). Similar results were seen at 30 min and 1 and 2 hrs. Another set of cells were fixed with Lyse/Fix solution (BD Biosciences) and permeabilized with Buffer III (BD Biosciences) stained for phosphorylated STAT3 (44). IL-6Rα shedding/cleavage into the culture supernatant was quantified using Mouse IL-6 R alpha Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis).

Generation and activation of mouse bone marrow–derived dendritic cells

Bone marrow-derived DC (DC) were generated as previously described (45), with minor changes. In brief, bone marrow was flushed from femurs and tibia from either young BALB/c ByJ or from Il6 −/− BALB/c ByJ mice and plated at 8 × 105 cells/ml in complete RPMI 1640 plus 10 ng/ml recombinant murine GM-CSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). On days 3 and 5, half of the culture media was replaced with fresh complete RPMI 1640 + GM-CSF. On day 6 the TLR9 agonist CpG 1826 (1μM; type B unmethylated CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides [ODNs]) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA), was added to the “activated” DC group followed 3 hours later by Poly I:C (10 μg/ml; Invivogen, San Diego, CA), a combination shown to have a synergistic adjuvant effect (31). On day 7 non-adherent unactivated DC and TLR agonist activated *DC were harvested and enriched by positive selection using directly conjugated CD11c magnetic beads and a MACS column, as per manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec).

Adoptive Transfer Model to determine role of *DC in enhancing aged CD4 T cell response

To evaluate the response of aged vs. young naïve CD4 T cells, naïve CD4 T cells were isolated from pooled spleens and enlarged lymph nodes of young or aged BALB/c.HNT.Thy1.1 TcR transgenic mice. Routinely 7×104 naïve CD4 T cells were transferred by i.v. injection into groups of 4 or more, DO11.10 (irrelevant TcR recognizing a peptide of Ovalbumin (OVA) BALB/c background mice. The donor cells were detected and followed by staining for the congenic marker CD90.1. In addition, 3 × 105 BMDC, activated (*DC) or not (DC) with TLR ligands, were pulsed with the HNT peptide, recognized by the CD4 T cells, HNTNGVTAACSHE at (18 μg/ml) and co-injected into the groups of hosts with young or aged CD4 donor T cells. All hosts mice were also inoculated with 2.5 ug of formalin inactivated PR8 virus (Charles River). After 7 days, five mice in each group were sacrificed and the donor CD4 T cells, in lung and spleen and host B cells were analyzed separately by staining and FACS analysis. Another five mice from each group were bled at different time points to monitor influenza specific Ab responses. Results are representative of 2 or more independent experiments with 5 mice per group.

In Vivo Cytotoxicity

In vivo cytotoxicity assays were performed as described with minor modifications (46). Naïve CD4 HNT T cells and *DC pulsed with HNT peptide, were transferred into BALB/cByJ with inactivated PR8 virus. Six days later, targets were prepared from BALB/cByJ splenocytes by negative selection with magnetic beads specific for CD90.2 using MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) depletion. This heterogeneous T cell depleted population was separated into target and bystander groups. Targets were pulsed with the class II-restricted HA126–138 peptide while bystanders were not pulsed, Both were kept for 1 h at 37°C in a water bath. Targets were labeled with 0.2 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes) and bystanders labeled with 2 μM CFSE. Targets and bystanders were combined at a 1:1 ratio, and a total of 5 × 106 cells/mouse were injected i.v. into hosts being evaluated. Control BALB/cByJ mice that did not receive CD4 HNT and DCs were also given targets and bystanders. 18 hours after injection, mice were sacrificed, spleens were removed, red cells lysed and cells were re-suspended in FACS buffer. The percentage of peptide-specific cytotoxicity was calculated from the differential recovery of CFSE-labeled pulsed targets and unpulsed bystanders, as follows: [1 − (live targets/live bystanders normalized to the ratio found in control mice) × 100].

PR8–specific Ab Titers

Influenza-specific Ab titers in were determined at different time points using ELISA. ELISA Plates (Nunc) were coated overnight at 4°C with influenza PR8 in coating buffer and were washed and blocked with PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.001% Tween 20. Serum samples serially diluted in PBS-Tween 20 with 1% BSA were incubated 2 h at room temperature. After washing, HRP-conjugated Abs specific for mouse total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and IgG2b (Southern Biotechnology Associates) were added at 0.2 μg/ml in PBS-Tween 20 with 1% BSA, and plates were incubated 1 h at room temperature. After washing, the HRP substrate o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride was added, and the OD of the color reaction was measured at 492 nm. Endpoint serum titers were defined by the OD reading of serum from unimmunized mice as negative control values giving baseline OD readings.

Medium and peptide and viral Ag

All cells were grown in complete RPMI 1640 containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), 50 μM 2- Mercaptoethanol (2ME) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 8% FBS (HyClone). The HNT peptide from PR8 HA(H1) (HA126–138; HNTNGVTAACSHE) was synthesized by New England Peptide (Gardner, MA) Formalin inactivated Influenza A/PR8/34(H1N1)/Inactivated/Purified Antigen was purchased from Charles River (North Franklin, CT)

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses compairing one sample to another were performed in Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) using Student’s t test. The p values <0.05 were considered significant. Error bars in figures represent the standard error of the mean (SEM), with the number of * indicating different levels of significance as described in the corresponding figure legends.

RESULTS

TLR agonist activation of *DC-APC leads to enhanced aged naive CD4 T cell expansion and generation of follicular helper cell subsets

We designed a reductionist in vivo mouse model to allow us to isolate the effects of TLR ligand-activation of the DC on the response of aged vs. young naive CD4 T cells from effects in other cells and to analyze the APC contribution to the mechanisms involved in the enhanced response. We generated BMDC in vitro, from young donors, since we had shown previously that BMDC generated from young donors gave equivalent results to those from old mice (31). BMDC were cultured overnight with TLR agonists, Poly I:C and CpG, which engage TLR 3 and 9 respectively and which together optimally induce *DC-APC that enhance aged naïve CD4 T cell expansion in vitro (31). The resulting *DC were compared to DC cultured without TLR agonists. Both were pulsed with peptide Ag (the HNT peptide from the H1 hemagglutinin of A/PR8) and co-transferred with naïve CD4 T cells with a transgenic TcR (HNT) specific for that peptide.

Naïve CD4 T cells were purified from young vs. aged HNT TcR Tg mice to accurately compare equal numbers of well-defined naive CD4 T cells with equivalent TcR affinity from young vs. aged mice. In the majority of experiments, they were then transferred at low numbers (7 ×104) into syngeneic young transgenic BALB/c hosts bearing an irrelevant TcR (Figure 1A). The CD4 T cells in the irrelevant TcR hosts (BALB/c.DO.11.10) recognize only the OVAII peptide and they thus lack helper function for PR8 IAV, but the mice are less CD4 T cell lymphopenic than T cell deficient mice. To evaluate the helper function of the transferred T cells, the host mice were injected with formalin-inactivated A/PR8/34 influenza virus (IIV) to provide a “vaccine-like” source of IAV Ag to the B cells, which may include activities of cells in the intact hosts such as follicular dendritic cells. This model, illustrated in Figure 1A, allowed us to manipulate each of the key variables involved in the response, to compare how DC-APC activation affected the generation of different CD4 subsets from young and aged naive CD4 T cells, and to evaluate the impact of those changes in CD4 T cells on GC B cell responses and long-term Ab response to IAV.

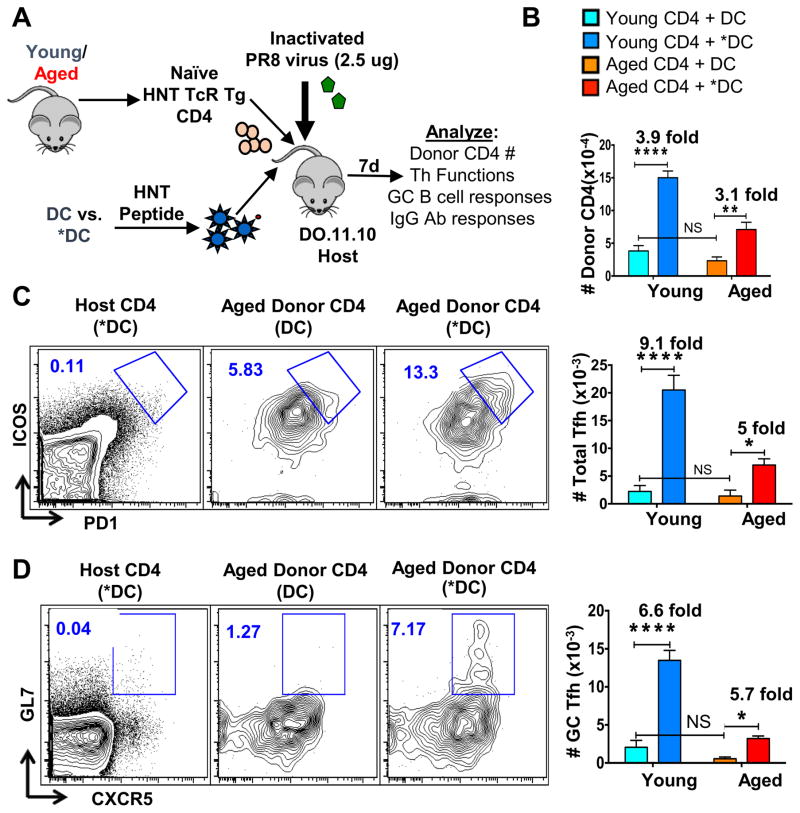

Figure 1. BMDC stimulated with TLR ligands and used as APC drive enhanced naïve CD4 expansion and Tfh generation in vivo.

We transferred sorted naïve CD4 T cells (7×104) from young vs. aged TCR transgenic HNT mice that recognize the HNT peptide and express the congenic marker CD90.1 (HNT.Thy1.1) into separate groups of DO.11.10 TcR Tg host mice. BMDC were generated as described previously and treated overnight with TLR agonists (*DC) or no agonist (DC). The two DC populations were pulsed with HNT peptide and 3 × 105 peptide-loaded DC were injected with CD4 T cells i.v. into separate groups of hosts. All host mice were also inoculated i.v. with 2.5μg formalin-inactivated PR8 virus. After 7 days, the splenocytes from individual mice were analyzed by flow cytometry and the percentage and absolute numbers of each cell type calculated.. A. Schematic illustrating experimental setup. B. Absolute numbers of donor CD4 T, donor Tfh and donor GC-Tfh cells found in spleens of host mice. C. Representative FACS analysis of donor aged HNT CD4 T cells expressing high levels of Tfh markers PD-1 and ICOS. D. Representative FACS analysis of donor aged HNT CD4 T cells expressing high levels of GC-Tfh markers CXCR5 and GL7. These data are representative of three separate experiments each with four mice per group. Statistically significant p values between groups of individual mice are shown and were determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM), with * indicating P < 0.05, ** indicating P < 0.005, and *** indicating P < 0.001. This experiment has been repeated 3 times in this exact model and in other hosts as indicated in Table 1.

Compared to control DC-APC, *DC-APC, led to greater recovery of aged CD4 effectors at day 7 post immunization from aged (3.1 fold) naïve CD4 donor T cells in spleen (Figure 1B). The *DC-APC vs. DC-APC also led to greater generation of aged donor Tfh (Figure 1B middle, Figure 1C) and GC-Tfh (Figure 1B bottom, Figure 1D), with 5-fold more Tfh and 5.7-fold more GC-Tfh (Fig 1B bottom). As expected, injecting HNT peptide-pulsed *DC did not drive significant host CD4 T cell responses indicating the necessity for the *DC as the cognate APC (Figure 1C left, Figure 1D left). In each case the responses of young IAV-specific CD4 Tg cells were comparably enhanced (Figure 1B). The enhanced response of the aged cells led to development of Tfh and GC-Tfh numbers that were approximately equivalent to those of young cells responding to DC that were not pre-activated (Figure 1B). Following live IAV infection, we usually detect Tfh subsets in both the spleen and draining lymph node (dLN), but with inactivated virus introduced intravenously (i.v.), we found the majority of the donor T and host B cells response was in the spleen, so we do not present the minor LN responses.

Previous studies have shown that DC migration is impaired in aged hosts due to reduced chemokine expression (9, 47) and one can imagine that co-injecting T cells with the DCs might give the CD4 T cells some unanticipated advantage. To ask if similar increases in aged CD4 T cell responses were seen in our model (Figure 1A) when *DC-APC and CD4 T cells were not co-injected, we transferred donor CD4 T cells either by co-injection with APC or one day after APC injection. Similar increases in aged donor CD4 T cell numbers were seen when APC were co-transferred in comparison to APC transferred a day earlier (Supplemental Figure 1A), suggesting the CD4 T cells and APC home correctly and do not have an advantage if co-injected.

We found that the same pattern of results was also observed when *DC-APC were transferred to intact BALB/c mice or T-deficient BALB/c mice in that the *DC-APC induced enhanced aged CD4 T cell expansion and Tfh responses similarly as summarized in Table 1. This indicates the reproducibility of the enhanced naive CD4 response induced by *DC-APC and confirms that it is independent of the presence of responding host T cells or the degree of lymphopenia in the mouse model used. Next, we asked if BMDC generated from old donors, also enhanced aged CD4 T cell responses similarly when activated by TLR agonists. We found a similar increase in the generation of total aged donor CD4 T cell effectors and in aged Tfh generation when aged as compared to young *DC-APC were used (Supplemental Fig 1B–C), confirming the ability of aged DC to be activated to enhance the helper response.

Table 1.

Summary of fold-increase in expansion of donor CD4 T cells, donor Tfh, and ThCTL and host GC B cells in different hosts receiving *DC compared to untreated DC using the model described in Enhanced of Responses when *DC compared to DC

| Donor Cells | Host Mice | Fold Increase (Spleen) | Fold Increase (Lung) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor CD4 | Donor Tfh | GCB cell | Donor CD4 | Donor ThCTL | ||

| HNT TcR Tg CD4 T cells | DO11.10 TcR Tg | 3.5 (±0.4) | 7.0 (±2) | 2.6 (±0.1) | 6.25 (±1.75) | 5.85 (±0.85) |

| HNT TcR Tg CD4 T cells | CD4KO | 3.55 (±0.15) | 7.2 (±0.8) | 2.5 (±0) | 7.5 (±3.5) | 13.5 (±8.5) |

| HNT TcR Tg CD4 T cells | Intact Host | 3.35 (±0.05) | 4.85 (±0.35) | 1.53 (±0.03) | 3.2 (±0.9) | 12.55 (±4.15) |

*DC-APC enhance GC B cell responses and IAV-specific Ab responses

The enhanced Tfh and GC-Tfh might enhance B cell responses, if CD4 help is limiting, which we expect is the case especially in aged mice. We asked if administering *DC-APC would induce enhanced GC B cell development, and IAV-specific IgG Ab, when the help was provided by aged or young donor naive CD4 T cells. As described above in Figure 1, aged and young naive HNT CD4 T cells were transferred to DO11.10 hosts which were primed with HNT peptide-pulsed DC or *DC, along with inactivated A/PR8 virus. We found a nearly 3-fold increase in frequency (Figure 2A) and numbers (Figure 2B) of GC B cells (GL7hiPNAhi) in spleens of mice that received donor aged naïve CD4 T cells and peptide-pulsed *DC-APC compared to those in mice with untreated DC-APC, suggesting that unactivated DC generated limiting CD4 T cell help from the aged CD4 T cells. Little B cell response was detected in mice that did not receive CD4 T cells (Figure 2A, left panel), confirming the lack of host CD4-mediated help. An increase in GC B frequency was also observed when aged *DC-APC were used, although unactivated aged DC-APC were attenuated in their ability to enhance GC B frequency when compared to young DC-APC (Supplemental Figure 1D). This suggests that although aging can attenuate DC activity, activation by TLR agonists is sufficient to restore their ability to act as better APC for aged naive CD4 T cells.

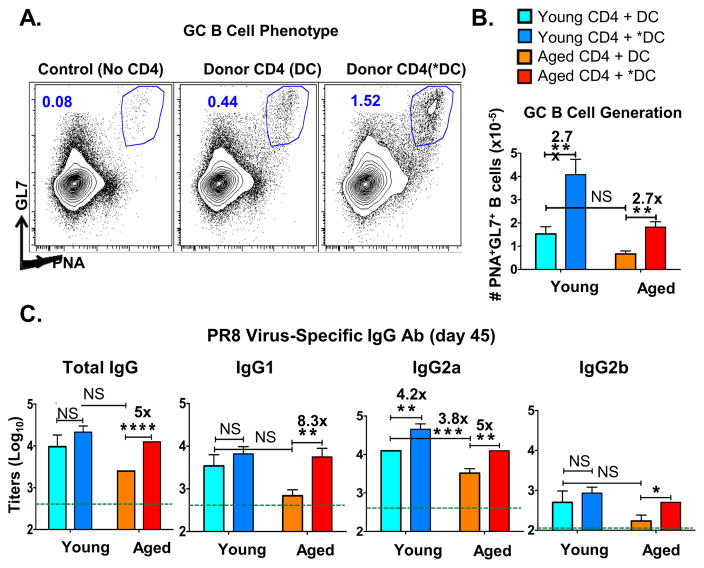

Figure 2. *DC used as APC for aged naïve CD4 T cells in vivo result in enhanced GC B cell and IgG Ab responses.

In the same experimental design described in Fig 1, a cohort of mice were analyzed for germinal center B cells (GCB) 7 days post transfer (dpt) of donor TcR transgenic CD4 T cells and HNT peptide-pulsed BMDC along with inactivated PR8 virus. Other mice were bled at 45 dpt for determination of serum total IgG Ab and IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b subclasses specific for PR8 virus by ELISA. A. Representative FACS plot showing the proportion of B cells expressing GCB cell markers GL7 and PNA. B. The absolute numbers of GCB cells in spleen as defined in A. C. PR8-specific total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a and IgG2b titers were determined in sera of individual mice at 45 dpt. Dotted lines show average background Ab levels in serum pooled from unimmunized BALB/c mice. Data shown are from one experiment and are representative of three separate experiments with 4–5 mice per group, analyzed individually. Statistically significant p values between experimental groups are indicated and were determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars represent SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001.

In young mice, live PR8 influenza induces a vigorous isotype-switched long-lived Ab response with production of high titers of IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b Ab specific for IAV (48). In the DO.11.10 hosts that lack IAV-specific CD4 T cells, inactivated IAV (IIAV) immunization without cell transfer resulted in low Ab levels (Figure 2C, indicated by lines across each panel). The increase in IgG Ab levels over the background after adoptive transfer of *DC and the aged donor naive CD4 T cells thus most likely reflects the ability of the *APC to drive CD4 helper development, which in turn determines the level of the B cell response and Ab production. We measured anti-influenza IgG responses in serum taken at 45 days after transfer and priming (Figure 2C). Comparing Ab generated in hosts given aged CD4 T cells (red and orange bars), there were significantly higher levels of IgG1 and IgG2a anti-influenza Ab when *DC rather than DC were used as APC. We note that there was little or no difference between the responses generated by young CD4 T cells with DC vs. *DC-APC, except for IgG2a levels, which were enhanced by *DC activation even when young CD4 T cells provided help. This suggests that CD4 T cell helper activity for IgG1 and IgG2b, is limiting in aged but not young naive CD4 T cells, but that the help for driving the IgG2a response is limiting in both young and aged.

The low but significant, background IAV-reactive IgG levels seen in young DO.11.10 hosts (indicated by dotted lines), was perhaps due to T-independent B cell responses or natural antibodies cross-reacting with IAV. However, the addition of the naïve CD4 T cells led to 10–100 fold increase over that background, clearly indicating the need for CD4 help for the majority of the IgG production (Figure 2C). That *DC activation strongly enhanced the IgG Ab production in hosts receiving aged, IAV-peptide specific CD4 T cells as measured 45 days later, suggested that long-lived plasma cells (LLPC) were generated. Thus, the treatment of DC-APC with TLR agonists initiated a greater Tfh response of the aged donor HNT T cells (Figure 1), and this in turn drove greater GC response and generation of enhanced long-lived anti-IAV Ab in response to the IIAV vaccine (Figure 2).

We asked if the increased anti-influenza antibody titers when *DC-APC were used, would contribute to increased protection from in vivo IAV infection. We collected sera from the two groups of mice receiving aged naive HNT CD4 T cells and inactivated PR8 and given either unactivated DC or *DC treated with TLR agonists (as described in Figure 1A). Each sera was injected at 100μl or 10 μl into groups of JhD mice that were then challenged with a lethal dose of PR8. Both doses of serum from *DC mice, were significantly better at preventing weight loss than the serum from DC mice at different time points, supporting improved protective ability (Supplemental Figure 2). Mice with no sera, all lost weight progressively and died by day 8, while all mice with sera survived. This suggests that increased Ab titers generated by *DC were indeed resulting in increased protective capacity against in vivo IAV infection.

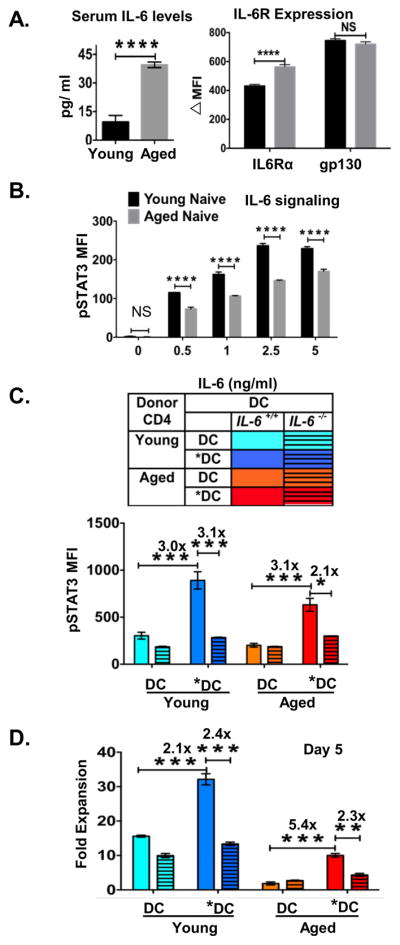

Aged naïve CD4 T cells have reduced IL-6 receptor signaling compared to young

In our previous study, we showed that the ability of *DC-APC to enhance naïve aged CD4 T cell response in vitro was reduced by blocking the IL-6 made by the *DC during the cognate *DC:CD4 T cell response (31). Since levels of systemic IL-6 are enhanced with age (36, 37), we considered the possibility that IL-6 receptor signaling in the aged CD4 T cells might be de-sensitized, possibly due to increased ambient levels of the cytokine, and that this could cause reduced response of aged naive CD4 T cells. We analyzed the concentration of IL-6 in serum of our aged BALB/c mice and as expected found a highly significant increase (Figure 3A, left panel), consistent with the possibility that naive CD4 T cells are exposed to higher systemic IL-6 levels in aged, compared to young, lymphoid organs. sIL-6Rα in the serum has also been shown to play an important role in IL-6 signaling (49, 50). We measured levels of sIL-6Rα in the serum to analyze if the increased levels of serum IL-6 with aging is due to decreased sIL-6Rα in circulation. There was no difference in levels of serum sIL-6Rα between aged and young mice, thus showing that sIL-6Rα did not play a role in increased serum IL-6 levels (Supplemental Figure 3A). To determine if aged naïve CD4 T cell express reduced levels of IL-6 receptor (IL-6R) chains, we analyzed young and aged naive CD4 T cells for surface expression. Compared to the young, unstimulated aged naive CD4 T cells had equivalent Il6R expression of gp130 subunits and but a small, but significant increase in the level of IL-6Rα (Figure 3A, right panel), arguing against a role of reduced receptor expression.

Figure 3. IL-6 signaling, determined in vitro, is less effective in aged vs. young naïve CD4 T cells.

Young and aged mice were bled and serum collected and naive CD4 T cells sorted from each were evaluated ex vivo by staining and FACS analysis.

A. Left: Levels of IL-6 in serum of individual unimmunized young and aged BALB/c mice were determined by IL-6 ELISA (n=4 mice per group). Right: IL-6 receptor expression was determined by staining and FACS analysis of gated naïve cells from (n=4 individual unimmunized young and aged mice). B. Doses of IL-6 (0.5–5ng/ml) were added to sort-purified young and aged naïve CD4 T cells cultured ex vivo. Cells were incubated with increasing doses of IL-6. The level of phospho-STAT3 expression was determined by FACS analysis. was determined by FACS staining of cells recovered 3 hr after addition of IL-6 (n=4 mice per group) C. Young and aged naïve CD4 T cells were cultured with TLR-activated (*DC) or non-activated DC pulsed with HNT peptide. After 80 hr, the level of phospho-STAT3 expression was determined by FACS analysis. D. After 5 days, cells were recovered from the cultures described in C, and donor CD4 cells enumerated. Fold expansion of naïve aged HNT CD4 T cells was determined. n= 3 wells. Experiment is representative of one of 3 separate experiments. Error bars represent SD of mean, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To evaluate the responsiveness of young and aged naïve CD4 T cells to IL-6, naïve young and aged HNT CD4 T cells were treated ex vivo with increasing doses of IL-6 and we measured phosphorylation of STAT3 (51), a key functional consequence necessary for IL-6-mediated activity. The phosphorylation of STAT3 was reduced in aged compared to young naive CD4 T cells, with about 5-fold greater IL-6 levels required by aged cells for the same level of response (Figure 3B). We examined expression of IL-6Rα following stimulation of naive young and aged CD4 T cells with IL-6 doses. The receptor complex is internalized following IL-6 binding resulting in reduced expression (43). The internalization of IL-6Rα was reduced in aged compared to young naive CD4 T cells, with aged cells requiring greater than a 10-fold increase in IL-6 levels for the same level of reduction (Supplemental Figure 3B). The reduction in IL-6Rα expression on the cells could also be because of IL-6Rα shedding or cleavage at the surface by matrix metalloproteinases which would result in increased sIL-6Rα in the supernatants. To evaluate this possibility, we tested for sIL-6Rα in the in vitro assay supernatants from experiment shown in Supplemental Figure 3B. No sIL-6Rα was detected in either young or aged naïve CD4 T cell supernatants at different IL-6 doses (Supplemental Figure 3C). Together these data support the hypothesis that aged naïve CD4 T cells intrinsically require higher levels of IL-6 to respond, and that this reduced response is not due to changes in IL-6 receptor levels or of sIL-6Rα in the circulation.

If reduced IL-6 signaling is responsible for the poor response of aged CD4 T cells, we reasoned the *DC should act in vitro to restore IL-6 induction of pSTAT3 and that using *DC made from BM of Il6−/− mice should prevent the advantage conferred by the TLR agonist activation of the APC. We cultured *DC-APC or DC-APC from WT or Il6−/− mice with young and aged naive TcR Tg HNT CD4 T cells and assessed upregulation of pSTAT3 (Figure 3C), The WT *DC-APC induced higher levels of pSTAT3 than DC-APC, in both young and aged CD4 T cells, but the *DC from Il6−/− mice lost the ability to induce higher pSTAT3, indicating that the induction was IL-6 dependent. To link the impact of the *DC-APC to induction of naive CD4 expansion, we asked if in the same conditions as Figure 3C, *DC induced greater aged vs. young naive CD4 expansion over a 5 day in vitro culture and if the IL-6 defective *DC failed to induce more expansion (Figure 3D). Indeed, *DC were able to support greater expansion and that expansion was reduced when *DC were from Il6−/− mice.

We conclude that despite high levels of systemic IL-6, aged CD4 T cells require higher levels of IL-6 produced during the CD4-APC cognate interaction, when compared to young CD4 T cells, to effectively induce downstream IL-6 signaling pathways. The ability of *DC-APC to enhance the in vitro response of aged naive CD4 T cells depends on their production of IL-6, although other components induced by TLR agonist activation may also be involved.

IL-6 production by *DC is necessary for enhanced naive CD4 Tfh generation in vivo

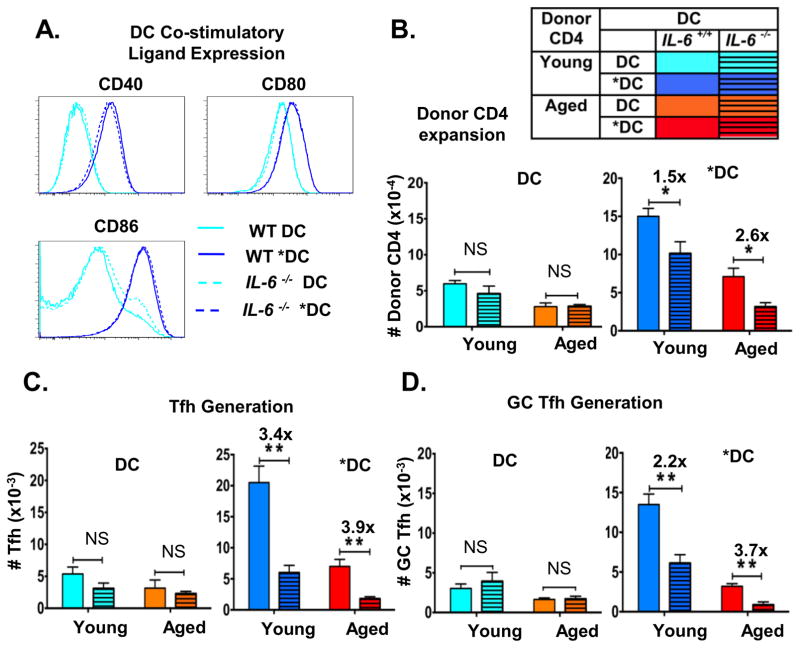

To analyze the in vivo role of IL-6 in *DC-mediated enhanced helper ability, we used the in vivo adoptive transfer model (Figure 1A) and used DC derived from WT vs. Il6−/− bone marrow. Since DC derived from Il6−/− mice might have inherent defects in expression of co-stimulatory molecules, which would provide other possible explanations for any observed defects in *DC priming of aged CD4 T cells, we evaluated the expression of co-stimulatory molecules, CD40, CD80 and CD86 in WT and Il6−/− DC and *DC (Figure 4A). We found that WT and IL-6-deficient DC express equivalent levels of co-stimulatory molecules and that each was enhanced equivalently by TLR agonist stimulation, suggesting IL-6 deficiency does not impact other aspects if DC activation

Figure 4. Enhanced expansion of donor CD4 T cells and the generation of Tfh due to pre-activating *DC-APC requires their production of IL-6.

BMDC were prepared from wild-type or Il6−/− mice and DC and *DC prepared from each. BMDC were pre-activated or not with TLR agonists as in Figures 1–2. A. The 4 different DC populations were analyzed by FACS analysis for expression of CD40, CD80, and CD86. B. Young and aged donor naïve HNT CD4 T cells and HNT-peptide-pulsed BMDC from WT and Il6−/− mice along with inactivated PR8 virus were transferred to DO.11.10 hosts as in Figure 1 and 2. After 7 dpt spleens from a cohort of mice were analyzed for donor CD4 T cell expansion and generation of total numbers of donor CD4 T cells recovered in mice receiving WT vs. Il6−/− DC and *DC are shown. C. The total number of donor HNT cells expressing Tfh markers of high levels of PD1 and ICOS. D. The total donor HNT cells expressing high levels of GC-Tfh markers CXCR5 and GL7. Data representative of two separate experiments with 4 mice per group analyzed individually. Statistically significant p values are shown and were determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars represent SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001.

In vivo, IL-6 deficient and WT DC-APC supported comparable modest expansion of donor young and aged naive CD4 T cells (Figure 4B. left panel) and equivalent generation of both splenic Tfh (Figure 4C. left panel) and GC-Tfh (Figure 4D left panel). In contrast, activated WT *DC-APC induced greater donor CD4 expansion (Figure 4B), generation of Tfh (Figure 4C) and GC-Tfh (Figure 4D), while IL-6-deficient *DC-APC failed to enhance CD4 T cell response of all types. Adding *DC-APC enhanced young as well as aged CD4 T cell responses and this was reversed when IL-6 was missing. This demonstrates that production of IL-6 by TLR agonist activation of DC is necessary for their ability to enhance expansion of aged CD4 T cells and their differentiation to Tfh and GC-Tfh.

*DC enhances generation of IL-21-secreting and Th17 polarized CD4 effectors

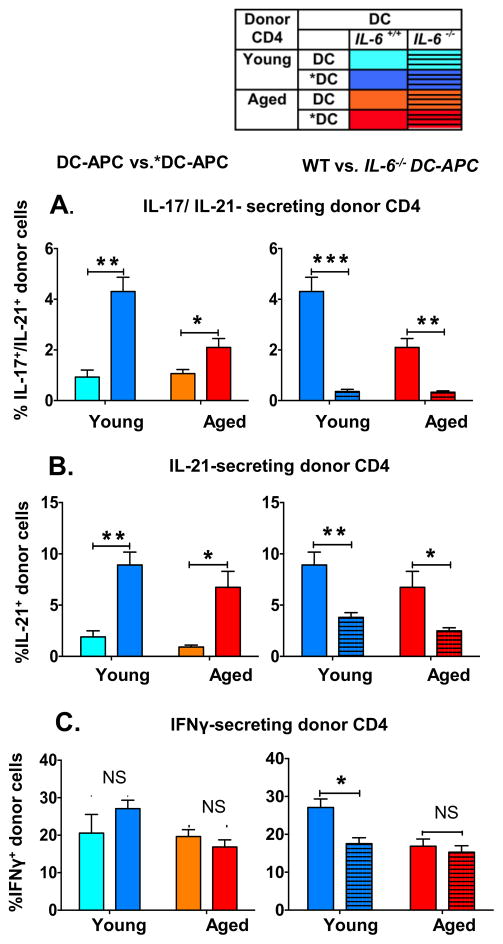

IL-6 and IL-21 both play key roles in the generation of Tfh (52–54) and hence Ab production (53). IL-6 has also been shown to be a key factor for Th17 generation (55, 56 ) and for IL-21 generation (53). We asked if *DC-APC would also enhance generation of effectors producing IL-21 with or without IL-17 in vivo from naive aged CD4 T cells and if that change would be IL-6 dependent. Ability of donor cells to produce IL-17, IL-21 and IFNγ was analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining (Figure 5). Compared to DC-APC, *DC-APC caused development of a significantly enhanced frequency of aged donor CD4 effectors that secreted IL-21 alone and that secreted both IL-17 and IL-21 (Figure 5A and 5B left). IL-17 only-secreting cells were rare and are not shown. The *DC-APC generated from Il6−/− BMDC did not have the ability to enhance either of the IL-21-producing populations indicating that DC-produced IL-6 is necessary for generation of IL-21 producing CD4 T cells (Figure 5A and 5B right). The frequency of IL-21–secreting young donor cells was also enhanced by *DC-APC and the increase was again IL-6 dependent as expected (53) Since *DC also enhanced the recovery of donor CD4 effectors (Figures 1 and 4), the impact of DC pre-activation on total number of IL-21-secreting cells is amplified. In contrast to the IL-21 secreting populations of effectors, the frequency of IFNγ-secreting effectors was not enhanced by *DC (Figure 5C left) and the absence of IL-6 secretion in *DCs did not impact the fraction of aged CD4 effectors making IFNγ (Figure 5C right).

Figure 5. IL-6 made by *DC-APC drives the enhanced production of CD4 effectors that produce IL-21 but not IFNγ.

As in Figures 1 and 2, donor aged vs. young naïve HNT CD4 T cells and HNT peptide pulsed BMDC from wild-type vs. Il6−/− mice, both unactivated and TLR agonist activated were transferred along with inactivated PR8 virus to DO.11.10 hosts. At the effector stage, 7 dpt, donor CD4 T cells were analyzed by intracellular cytokine-staining (ICCS) to detect their ability to secrete IL-17, IL-21 and IFNγ. Left panels compare DC to *DC, right DC from WT vs. Il6−/− mice A. Percent of donor HNT cells co-expressing IL-17 and IL-21. B. Percent of donor HNT cells expressing IL-21 but not IL-17. C. Percent of donor HNT cells expressing IFNγ. Data shown are from one experiment and are representative of two separate experiments with 4 mice per group analyzed individually. Statistically significant p values are shown and were determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars represent SEM of mean *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001.

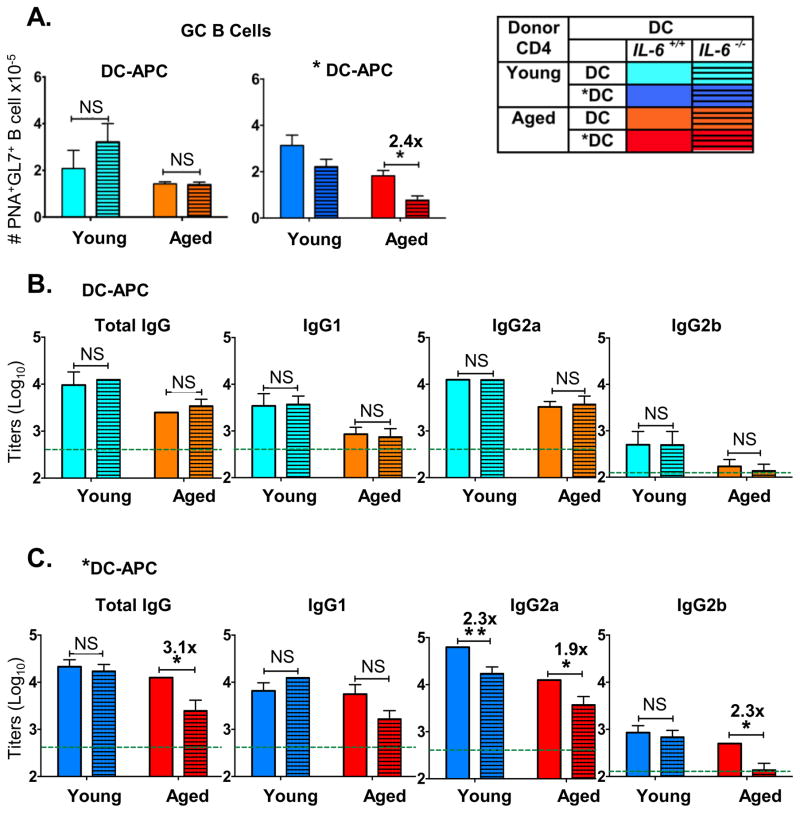

IL-6 production by *DC is required to enhance GC B generation and IgG Ab to IAV driven by aged CD4 T cells

Since the *DC-APC enhanced Tfh, GC-Tfh and IL-21 producing effectors were all IL-6 dependent, we asked if the improved GCB generation and IAV-specific IgG Ab production, as seen in Figure 2 would also depend on *DC-produced IL-6. When DC-APC were not activated, lack of IL-6 had no significant effect on GCB cell generation in hosts that received either young or aged naive CD4 T cells (Figure 6A, left). However, *DC-APC enhanced GCB cell generation in hosts that received aged naive CD4 T cell help (Figure 6A, right) and the enhanced response was lost when Il6−/− *DCs were used.

Figure 6. IL-6 made by *DC-APC is required for enhanced GC B cell generation and IgG Ab response.

As in Figures 4 and 5, peptide-pulsed control or pre-activated DC from WT vs. II6−/− were used as the APC for donor TcR transgenic CD4 T cells that were transferred with inactivated PR8 virus. After 7 dpt spleens were analyzed for generation of GC B cell and IgG Ab to PR8 IAV. A. Total numbers of host B cells recovered expressing high levels of GCB cell markers, PNA and Fas in mice with WT vs IL-6−/− DC (left) or *DC (right) as APC. B. Serum PR8-specific titers for total IgG, IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b at day 30 in groups receiving DC (WT vs. Il6−/−). C. Titers in serum from mice receiving *DC (WT vs. Il6−/−). Dotted lines show average background Ab levels in serum pooled from unimmunized BALB/c mice. Data are representative of two separate experiments with 4–5 mice per group analyzed individually. Statistically significant p values are shown and were determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars represent the SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001.

Production of IAV-specific total IgG and IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b in serum was determined by ELISA analysis of serum collected at day 30. With unactivated DC-APC, IL-6 deficiency did not decrease total IgG Ab or any of the isotypes (Figure 6B), but when *DC-APC were used (Figure 6C) and aged HNT CD4 T cells provided help, higher titers of total IgG and IgG2a and IgG2b were produced (as in Figure 2C) and the enhanced response in all but IgG1 was lost when *DC were IL-6 deficient (Figure 6C). In agreement with results in Figure 2, recipients of young helper cells did not show a significant impairment in total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2b when *DC were IL-6 deficient, but IgG2a was significantly reduced without IL-6 (Figure 6C). These results indicate that aged CD4 T cells that drive T-dependent B cell responses are more dependent on IL-6 than are young ones. They also suggest that while help provided by aged CD4 helper responses for the GCB response and development of long-lived Ab-secreting cells is limiting, that provided by young Tfh and GC-Tfh is less or not limiting. Interestingly, the development of IgG2a Ab-secreting B cells was reduced by loss of IL-6 even when young helper cells were present, suggesting that IL-6 may play an additional important role in the switch to the IgG2a isotype. Thus most aspects of CD4 follicular helper function read out as GCB and production of IgG Ab, were enhanced by activating *DC-APC with TLR agonists and when help was limiting as in the case of aged CD4 T cells, the enhanced response required *DC-APC production of IL-6.

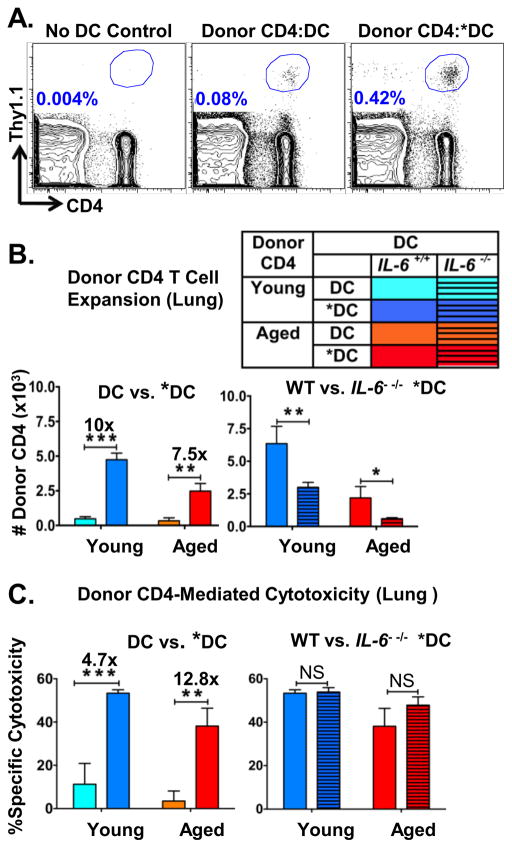

*DC enhances recovery of lung CD4 T cells including those with cytotoxic function, but development of cytotoxicity is IL-6 independent

Immune responses in the lung have been shown to be important in protection against and clearance of IAV infections (57, 58). To better understand the abilities of *DC to enhance naïve CD4 T cell responses, we asked how those CD4 effector responses within the lung were impacted by the pre-activation of DC with TLR agonists. We analyzed total donor cell recovery in the lung. Addition of Ag-pulsed DC, even without activation, induced enhanced recovery of total donor CD4 T cells in the lung (Figure 7A) and *DC-APC caused a greater increase in overall number of lung donor CD4 T cells (Figure 7A and 7B) than DC-APC. IL-6 production by the *DC-APC was needed for the increased recovery (Figure 7B) of naive CD4 aged T cells. IL-6 production by *DC-APC also enhanced recovery of young naïve CD4 T cells, though this enhancement by *DC was not solely dependent on IL-6 in case of young CD4 T cells.

Figure 7. *DC-APC enhance expansion of donor CD4 T cells in the lung but IL-6 made by *DC-APC is not necessary for generation of ThCTL.

In the same experiments as shown in Figure 6, donor cells in the lung were analyzed and an in vivo cytotoxicity assay was done. A. Lungs of hosts were analyzed for donor CD4 T cell expansion by FACS. A representative FACS analysis of donor CD4 T cells showing recovery in lungs of mice with no transferred DC-APC (left) or with DC or *DC as APC. B. The bar graphs show total numbers of donor HNT CD4 T cells recovered from the lungs of mice with APC derived from DC vs. *DC (left) and from WT vs. Il6−/− DC (right). C. In vivo cytotoxicity. At 6 dpt groups of mice described above were given a mixture of peptide-pulsed CFSElo and control unpulsed CFSEhi targets and after 18 hr the specific cytotoxicity was determined by enumerating surviving targets recovered in the spleen. Data representative of two separate experiments with 4 mice per group. Statistically significant p values are shown and were determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars represent the SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001

CD4 cytotoxic T helper cells (ThCTL) have been shown to be an important effector population generated in the tissue during IAV immune responses (57, 59, 60). Generation of ThCTL depend on IL-2, but in vitro development of cytotoxicity is not IL-6 dependent (57), though in vivo requirements for IL-6 in ThCTL generation are not known. We assayed whether *DC-APC and IL-6 would alter the degree to which CD4 lung effectors that could kill specific peptide-pulsed targets develop in vivo. To assess cytotoxicity, we co-injected unpulsed CFSEhigh bystanders and CFSElow targets pulsed with the HNT peptide (HA126–138) which is recognized by donor CD4 T cells into hosts transferred 6 days previously with HNT TcR transgenic young or aged CD4, DC or *DC pulsed with HNT peptide and inactivated PR8. HNT-specific cytotoxicity, indicated by the preferential deletion of HA126–138 (HNT) peptide-loaded targets, was higher in mice that received *DC compared to mice which received unactivated DC in groups receiving either young or aged donor CD4 T cells, with over 12-fold more killing in mice receiving aged CD4 T cells (Figure 7C). Unlike recovery of total lung CD4 effectors, IL-6 from *DC was not needed for generation of ThCTL with enhanced cytotoxic function and there was no effect of Il6 deletion on HNT-specific cytotoxicity (Figure 7C). This data demonstrates the selective importance of IL-6 for those CD4 subsets that are involved in helper functions–Tfh, GC-Tfh and those that produce IL-21; while other subsets such as Th1 cells (Figure 5C) and here ThCTL cells in the lung, shown here, are not dependent on IL-6 produced by *DC.

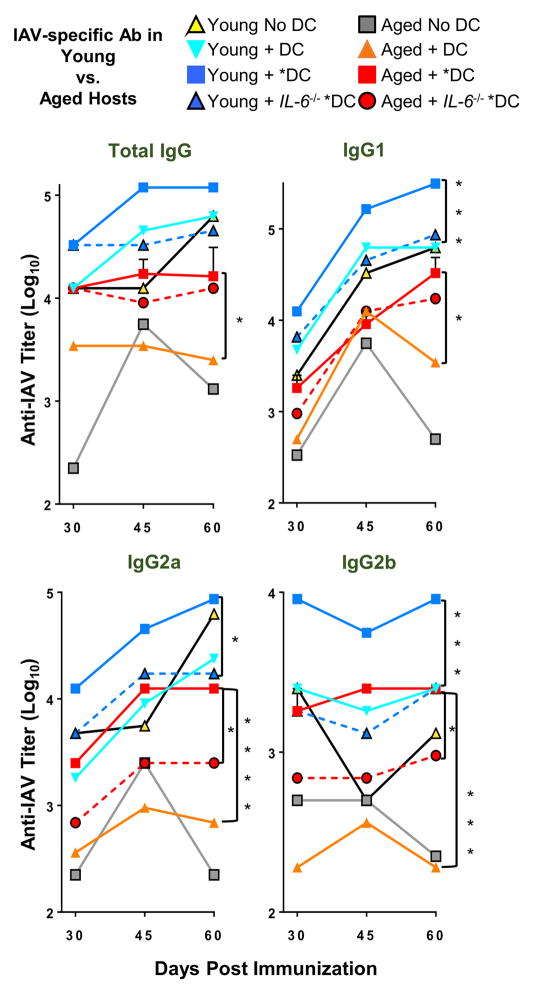

*DC-APC alone can enhance the polyclonal responses of aged hosts

Recent studies suggest that the aged host microenvironment plays a significant role in impaired aged immune responses at several levels as does aging of B cells (37, 47). To study if *DC could also enhance the polyclonal response in the aged host environment, where all T, B and APC are aged, we immunized intact aged and young mice with unactivated DC vs. *DC, each pulsed with inactivated whole PR8 virus, instead of the HNT peptide used in previous experiments. On day 4, each mouse received a dose of 2.5ug inactivated PR8 (IIAV) to provide sustained Ag for B cell and Tfh development. Since it would be difficult to identify the small fraction of IAV-specific CD4 Tfh or GC B cells generated in this model, we measured only the generation of IAV-specific IgG Ab. Titers of anti-IAV IgG responses were determined by ELISA in sera taken at days 30, 45 and 60 post-immunization, to encompass early B cell Ab production as well as long-lived Ab-producing cells (Figure 8, Supplemental Figure 4).

Figure 8. Inactivated PR8 virus pulsed DC* used as APC in young or aged, enhance host IgG Ab response.

Inactivated PR8 virus-loaded DC (5 × 105) activated overnight with (*DC) or without (DC) TLR ligands were transferred to young or aged BALB/c hosts. Mice were inoculated with inactivated PR8 IAV (IIAV) after 4 days, to provide viral Ag. After 30, 45 and 60 days of DC immunization, mice were bled and total serum IgG levels and IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b specific for PR8 were determined by ELISA.

Data are representative of three separate experiments with 4–5 mice per group. Statistically significant p values comparing DC vs. *DC, and *DC vs. *DC. Il6−/− within young or aged groups at day 60 only are shown and were determined using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars represent the SEM, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

We were not surprised to find that in the intact mice the results were more variable than in our reductionist model. So we will point out only the significant differences we saw between groups (Figure 8), and indicate if they were seen at all time-points (Supplemental Figure 4). Aged responses with no DC (Figure 8 grey squares) and aged responses with DC (orange diamonds) were consistently lower than young responses, and addition of the *DC to aged mice (red squares) enhanced the aged Ab responses including significant increases between *DC vs. DC in total IgG at all 3 time-points: day 30, 45 and 60, in IgG1 only at day 60, and in IgG2a and IgG2b at all time-points (Supplemental Figure 4). When the *DC were from IL-6 deficient mice, the IgG2a and IgG2b responses in aged mice were significantly reduced at days 45 and 60, but significant reductions were not seen in the total IgG or IgG1 response.

In summary, in this polyclonal model in intact aged vs. young mice addition of *DC vs. DC led to higher titers of all isotypes at all time points measured in aged mice, but these reached significance only part of the time in young mice, indicating a more modest effect. The impact of removing IL-6 was also consistently significant only for aged IgG2a and IgG2b responses, though effects were also observed at some time points in young mice. It is also clear that the young Ab response with DC is greater than that of aged mice with DC (all isotypes, all time points) and the effects of *DC vs DC including those mediated by IL-6 are more obvious in aged mice. As noted above *DC consistently enhance the aged response up to day 60, suggesting both earlier Ab and LLPC (days 45 and 60) were enhanced by *DC-APC in aged mice.

Although further studies are needed to analyze the effects in polyclonal models, these results indicate *DC-APC activated before transfer by TLR agonists, can often enhance polyclonal helper-CD4 dependent B cell Ab responses in aged animals and confirms that DC produced IL-6, as a consequence of DC activation by TLR agonists, is important for enhancing IgG2a and IgG2b isotypes of with variable effects on IgG1 and Total IgG. The results suggest *DC also enhance CD4 T cells by other pathways in addition to those mediated by IL-6. The fact that addition of *DC-APC presenting Ag can act on polyclonal naive CD4 T cell in the context of the aged host sufficiently to enhance defective aged B cell Ab response, indicates that this is a robust phenomenon.

Discussion

We find that TLR agonist-activated *DC, acting as APC, have a striking ability to enhance the in vivo generation of CD4 T cells with helper functions from naive aged CD4 T cells that in turn promote greater Ab responses to IIV. Thus, key age-associated naive CD4 T cell defects can be substantially overcome merely by exposing the DC-APC to PRR agonists. The APC must be able to make IL-6 to enhance expansion of both aged and young naïve CD4 and their differentiation to Tfh, GC-Tfh and IL-21-secreting effectors. This reveals a central role for IL-6 made by activated APC during the initial cognate interaction to comprehensively drive helper CD4 function at multiple levels. Our results indicate that the IL-6 produced by unactivated DC-APC becomes insufficient to drive the aged naïve CD4 T cell helper response leading to a limited GCB cells and IgG antibody production. We thus suggest that IL-6 is a key “signal three” for eliciting helper CD4 effectors and that activating APC with PRR-signals to enhance IL-6 production and Ag presentation improves CD4 helper responses to vaccines with low adjuvanticity in both young and aged cells.

The sufficiency of PRR-driven APC activation to enhance CD4 helper T cell and B cell immune responses, without the need for introducing TLR agonists into the animals, could point the way to non-inflammatory strategies to improve vaccines for the elderly and the young. When already activated APC present class-II restricted viral epitopes, they engage and secrete IL-6 only when they interact with the epitope-specific CD4 T cells and thus their effect is restricted to the CD4 T cells recognizing antigen, avoiding non-antigen specific effects of PRR agonists.

Also of note, we find poor responses of aged naïve CD4 T cells to IL-6 and selective deficiency of helper functions, compared to inflammatory and cytotoxic functions that are less impaired in the aged. This implies complex re-programming of priorities instead of an indiscriminate loss of immune function with age. As this phenomenon becomes better understood, it could also turn our attention to approaches that selectively harness the functions best retained in the aged.

Importantly, the reduced IL-6 signaling responses of aged naive CD4 T cells are restored by higher IL-6 levels. In vitro activation of aged naive CD4 T cells as indicated by phosphorylation of STAT3 (pSTAT3) and down-regulation of IL-6Rα were thus dependent on higher doses of IL-6 than those required by young naive CD4 T cells (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure 3B). Consistent with the proposed central role of IL-6, *DC-APC drove enhanced pSTAT3 and enhanced expansion in interacting naïve aged CD4 T cells (Figure 3C–D) and these were dependent on IL-6. When IL-6 deficient *DC were used, the *DC were no better than DC without pre-activation, supporting the hypothesis that TLR agonist induction of enhanced capacity of APC to make elevated IL-6, is a key requirement for their ability to enhance aged CD4 responses. This explains our earlier in vitro studies where blocking Ab to IL-6, but not TNFα prevented the aged naive CD4 expansion in response to *DC-APC (31). Thus, we suggest the reduced responsiveness to IL-6 is a key component of age-associated defective naïve CD4 responses. This is in line with previously published studies where an intrinsic defect in aging CD4 T cells has been identified (11, 61)

Our earlier studies indicated that agonists for most TLR receptors were effective in enhancing expansion of aged CD4 T cells in vitro, with the combination of Poly I:C (a TLR 3 agonist) and CpG (a TLR 9 agonist), synergizing to produce optimum results (31). The TLR3/9 combination greatly enhanced DC expression of class II and costimulatory ligands CD80, CD86 and CD40 (Figure 4A) and these activated *DC when used as APC secreted much higher levels of IL-6, KC, IL-12 and TNFα and other pro-inflammatory cytokines during the cognate interaction with CD4 T cells (31). We have not explored other TLR and PRR agonist pathways for in vivo effects, but predict multiple pathways that enhance inflammatory cytokine production would produce similar enhancement that would be correlated with their induction of IL-6 produced during subsequent cognate interactions. While IL-6 production is a key factor here, we suspect other features of activated APC also contribute to the response. For instance, enhanced ThCTL responses were driven by *DC-APC, but were not IL-6 dependent (Figure 7) suggesting such other pathways. The unique aspect of these studies, as opposed to the multitude of studies where introduction of PPR systemically enhances responses, is that only the APC are activated, restricting the impact mostly to the T cells recognizing the specific Ag presented by the APC. In fact the APC are short-lived and disappear within 48 h, limiting broader effects. *DC-APC, transferred to adoptive hosts, also present Ag for less than 2 d, so they must play their role early, likely at the initial cognate interaction with naive CD4 T cells (62).

*DC-APC promoted multiple IL-6 dependent aspects of CD4 help causing higher CD4 effector recovery in both spleen and lung (Figures 1B, 4B and 7B) and polarization and generation of Tfh, GC-Tfh and IL-21-producing CD4 effectors. It is well known that IL-6 has a general effect on reducing CD4 cell death and promoting expansion in vitro (25, 31, 63, 64), and the studies here indicate this same role is prominent in vivo. IL-6 production by *DC selectively enhanced the generation of Tfh and GC-Tfh effector subsets (Figures 1B, 4C and 4D) and of effectors that produce IL-21 (Figure 5A–B). In each case, the enhanced responses of aged cells, were lost when the DC were derived from Il6−/− mice, indicating that the multiple survival and polarizing in vivo roles of IL-6, many of which have been previously established (31, 52, 53, 64), are mediated coordinately by IL-6 produced by the APC acting during initial cognate recognition. Because responses of aged CD4 T cells require more IL-6 than young, it is predictable that help for B cells is limiting and that un-activated APC support sub-optimal T-dependent B cell Ab responses and this revealed the full extent of the coordinate enhancement of IL-6 produced by APC on helper differentiation.

The enhanced generation of GCB cells and production of IAV-specific Ab, achieved by providing *DC-APC (Figure 6), required the addition of peptide-specific CD4 T cells (Figure 2) and was thus most likely due to a secondary effect of the greater help that is generated. The exogenous *DC-APC that were added presented only the HNT peptide recognized by the Tg TcR of the donor naive CD4 T cells, so presumably they would not themselves interact with IAV-specific B cell BcR that recognize only IAV determinants. In support of this, in the absence of Ag specific donor CD4 T cells, *DC-APC did not enhance B cell responses (Figure 2A).

Impressively, transferring TLR agonist pre-activated *DC presenting IAV Ag, also enhanced the long-lived IgG response in intact aged mice compared to unactivated DC presenting IAV Ag, despite the fact that all lymphocytes and other cells, including the responding B cells, are “aged” and the host T cells were polyclonal (Figure 8). This result reinforces the physiological relevance of the effects seen throughout this study, and supports the concept that the activation of the initial APC presenting Ag to naïve CD4 T cells has permanent effects that are of sufficient impact to drive improved Ab production in aged mice.

Although we have stressed the improved responses of aged naïve CD4 T cells, each of the young naïve CD4 T cell helper responses tested was comparably enhanced by TLR agonist-activated *DC-APC (Figure 1B) indicating that when IIV is the immunogen, the CD4 expansion and helper responses of young CD4 T cells are also suboptimal for generation of CD4 helper responses. As in the case of aged cells, the *DC-enhanced generation of Tfh, GC-Tfh and IL-21 secreting cells from young naive CD4 cells, was reversed when the *DC were IL-6 deficient (Figure 4B–D and Figure 5A–B). However, when young CD4 were the source of help in the transfers to DO.11.10 hosts, while GCB numbers increased, IgG Ab production was only variably enhanced by *DC-APC (Figure 2 and 6), suggesting that the young CD4 T cell helper function was often sufficient for driving Ab production without the additional *DC-APC enhancement of helper subsets. In the more physiologic, non-transfer model in which we looked at polyclonal responses enhanced by *DC-APC (Figure 8), Ab production was broadly enhanced in aged mice, while results in young mice were lower in magnitude, and not significant at all time points. Thus, it is likely that generation of CD4 T cell help is only sometimes limiting in the un-manipulated young animals, but that it is nearly always limiting in aged ones. The IIV vaccine used here contrasts sharply with live virus that creates very high titers of Ag-presentation for a prolonged time and in the lung as well as secondary lymphoid organs (39), with IAV clearance beginning only about day 7 (65). Live IAV brings with it a broad spectrum of PRR agonists, which should obviate the need for exogenous *DC-APC activation. Thus, our studies are relevant to the limited CD4 responses induced by vaccines devoid of live pathogen and lacking strong PAMP expression. We predict that exogenous activated APC that secrete IL-6 should in most cases be un-necessary following live infections, since activated APC will be generated by the infection. This is consistent with the lack of a need for IL-6 for T cell help in infection models (22). Perhaps other costimulatory pathways or cytokines can substitute for IL-6 when PRR can activate large numbers of activated APC.

Of note, IgG2a and IgG2b showed some dependency on the IL-6 produced by TLR stimulation of *DC (Figure 6C, Figure 8, Supplemental Figure 1). This is consistent with the concept that there is a hierarchy among B cell responses with differentiation to IgG2a and possibly IgG2b requiring more help and showing greater IL-6 dependence than other IgG isotypes and raising the possibility that IL-6 is a switch factor for IgG2a and IgG2b. Various cytokines such as IL-4, TGFβ and IFNγ have been implicated in class-switching recombination (CSR) and they activate transcription factors that initiate IH-S-CH transcription (66, 67). Whether IL-6 plays a role in CSR, preferentially directing switching towards IgG2a and IgG2b transcripts, is an important question that warrants further investigation. Recent studies have also shown an important role for IgG2a broadly neutralizing Ab (bNAbs) over IgG1 with the same specificity, in mediating ADCC in vivo and thus viral clearance in context of influenza infection (68, 69). The selective impact of IL-6 on IgG2a and IgG2b may prove to be important in this context as well.

The marked enhancement of naive CD4 T cell responses and especially their differentiation to Tfh and GC-Tfh that drive B cell short and long-term IgG Ab responses, suggest that IL-6 acts as a “third signal” cytokine as defined for CD8 T cells (23). Inflammatory cytokines (IL-12 and type I IFN) provide necessary signals for the initial activation of naive CD8 T cells during the first interaction with peptide-MHC on APC, and there is a comparable, but unidentified, third signal for CD4 T cells. Our results suggest that IL-6 provides a comparable third signal for CD4 helper differentiation, while Th1 effector development and cytotoxic development are not IL-6 dependent and likely depend on other distinct APC-produced inflammatory cytokines (24). Recent results suggest IL-6 can enhance the response of human CD4 T cells to influenza ex vivo (1) raising the possibility that the enhancing effects of *DC-APC, may extend to already primed CD4 T cells as well as naïve cells.

The findings here that TLR-activation generates *DC–APC enhanced donor CD4 expansion and cytotoxicity in the lung but that the level of cytotoxicity and Th1 generation was independent of IL-6 (Figure 7C), help to explain observations that aged naïve CD4 T cells make poor helper responses (12) but still make Th1 effectors and ThCTL (38). We conclude that with advanced age, there is an exaggerated impairment of IL-6 dependent CD4 helper responses and the B cell responses they support, while other arms of the CD4 response such as the Th1 and ThCTL effector generation remain relatively unimpaired, leading to a major shift in the aged CD4 T cell response and its protective potential. Further investigation of this shift and how it impacts protective immunity is in progress.

We, and others have shown that CD4 memory cells that develop early in life, remain functional and protective with age (15) and that many age-associated defects in naïve CD4 T cells, including their helper function, are the result of intrinsic changes with age in the naive CD4 cells that are mostly independent of the aged environment (16–18). A program that assured age-associated dependence on higher levels of PRR agonists could limit un-necessary immune responses and dangerous ones such as those to self, while retaining those to dangerous pathogens. Our findings in this study also point to an intrinsic defect in aged CD4 T cells where higher levels of IL-6 are required to elicit a robust response. With memory T cells in place to previously encountered pathogens and some preservation of Th1 and cytotoxic responses, the aged immune system may have evolved this stronger PRR-dependence to reduce naïve CD4 helper responses except when a new strain or pathogen emerges. Previous studies have also described an age-associated defect in APC homing and activation where higher levels of TLR stimulation are required for equivalent inflammatory responses from aged DCs (47, 70–72). We have argued in past that limiting immune responses that result in extensive proliferation of CD4 T and B cells could also be part of a general tumor suppressor mechanism, and indeed aged naive CD4 T cells also express higher levels of tumor suppressor-associated products such as p16ink4a (61). If so, the age-associated changes that occur may have a selective advantage for overall health despite the fact they subvert the effectiveness of vaccines in the aged.

It is important to determine whether activating DC-APC in humans can also result in the restoration of improved helper T cells via production of IL-6 by the APC or other pathways. Recent systems-biology analyses of human responses to influenza vaccines suggest activation of APC is an important correlate of successful Ab response and that with age such activation is reduced (73), as would be predicted if activation of DC played a pivotal role in successful helper responses and thus protective Ab responses.

How might this activation of APC be achieved? A few promising approaches involving the use of antigens linked to antibodies or aptamers specific for various DC receptors such as DEC-205, Clec9A and Clec12A have emerged in the past few years (39, 74–77). The observation that age-associated defects in naïve CD4 T cells could be largely circumvented by using TLR agonist-activated *DC as the APC in vivo, provides a proof-of-principle that if strategies can be developed to effectively co-target APC with Ag and TLR agonists in vivo, the resultant *DC-APC should enhance Ag–specific CD4 helper responses without generating non-specific effects seen with injection of adjuvants containing PAMPs (34). Thus, safe strategies to improve the poor vaccine efficacy often seen in the elderly, may be possible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this manuscript is supported by grants from NIH, including R37AG025805 and P01AG021600 to S.L.S.

We thank the UMMS flow cytometry core for help with cell sorting. We thank all members of the Swain-Dutton lab for their helpful discussion throughout.

Abbreviations used in this article

- DC

dendritic cell

- dpv

days post vaccination

- dpt

days post transfer

- GC

germinal center

- GCB

germinal center B cell

- IAV

influenza A virus

- IIV

formalin-inactivated A/PR8/34 influenza virus

- Tfh

T follicular helper cells

- Tg

transgenic

- ThCTL

CD4 cytotoxic T helper cells

- WT

wild type

References

- 1.McElhaney JE, Kuchel GA, Swain S, Haynes L. T cell immunity to influenza in older adults: A pathophysiological framework for development of more effective vaccines. Frontiers in Immunology. 2016:7. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haynes L, Swain SL. Why aging T cells fail: implications for vaccination. Immunity. 2006;24:663–666. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElhaney JE. Influenza vaccine responses in older adults. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taub DD, Longo DL. Insights into thymic aging and regeneration. Immunol Rev. 2005;205:72–93. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hale JS, Boursalian TE, Turk GL, Fink PJ. Thymic output in aged mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8447–8452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601040103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yager EJ, Ahmed M, Lanzer K, Randall TD, Woodland DL, Blackman MA. Age-associated decline in T cell repertoire diversity leads to holes in the repertoire and impaired immunity to influenza virus. J Exp Med. 2008;205:711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazuardi L, Jenewein B, Wolf AM, Pfister G, Tzankov A, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Age-related loss of naive T cells and dysregulation of T-cell/B-cell interactions in human lymph nodes. Immunology. 2005;114:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.02006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shifrut E, Baruch K, Gal H, Ndifon W, Deczkowska A, Schwartz M, Friedman N. CD4(+) T Cell-Receptor Repertoire Diversity is Compromised in the Spleen but Not in the Bone Marrow of Aged Mice Due to Private and Sporadic Clonal Expansions. Front Immunol. 2013;4:379. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linton PJ, Haynes L, Klinman NR, Swain SL. Antigen-independent changes in naive CD4 T cells with aging. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1891–1900. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia GG, Miller RA. Age-dependent defects in TCR-triggered cytoskeletal rearrangement in CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:5021–5027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haynes L, Swain SL. Aged-related shifts in T cell homeostasis lead to intrinsic T cell defects. Semin Immunol. 2012;24:350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton SM, Burns EM, Kusser K, Randall TD, Haynes L. Age-related defects in CD4 T cell cognate helper function lead to reductions in humoral responses. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1613–1622. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frasca D, Blomberg BB. Aging impairs murine B cell differentiation and function in primary and secondary lymphoid tissues. Aging Dis. 2011;2:361–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swain SL, Blomberg BB. Immune senescence: new insights into defects but continued mystery of root causes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25:495–497. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Randall TD, Swain SL. CD4 T cell memory derived from young naive cells functions well into old age, but memory generated from aged naive cells functions poorly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15053–15058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433717100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsukamoto H, Clise-Dwyer K, Huston GE, Duso DK, Buck AL, Johnson LL, Haynes L, Swain SL. Age-associated increase in lifespan of naive CD4 T cells contributes to T-cell homeostasis but facilitates development of functional defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18333–18338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910139106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Randall TD, Swain SL. Newly generated CD4 T cells in aged animals do not exhibit age-related defects in response to antigen. J Exp Med. 2005;201:845–851. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eaton SM, Maue AC, Swain SL, Haynes L. Bone marrow precursor cells from aged mice generate CD4 T cells that function well in primary and memory responses. J Immunol. 2008;181:4825–4831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia GG, Miller RA. Age-related changes in lck-Vav signaling pathways in mouse CD4 T cells. Cell Immunol. 2009;259:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perkey E, Fingar D, Miller RA, Garcia GG. Increased mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 signaling promotes age-related decline in CD4 T cell signaling and function. J Immunol. 2013;191:4648–4655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Swain SL. Effect of age on naive CD4 responses: impact on effector generation and memory development. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2002;24:53–60. doi: 10.1007/s00281-001-0095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crotty S. A brief history of T cell help to B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:185–189. doi: 10.1038/nri3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtsinger JM, Mescher MF. Inflammatory cytokines as a third signal for T cell activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Sasson SZ, Hu-Li J, Quiel J, Cauchetaux S, Ratner M, Shapira I, Dinarello CA, Paul WE. IL-1 acts directly on CD4 T cells to enhance their antigen-driven expansion and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7119–7124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902745106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vella AT, Mitchell T, Groth B, Linsley PS, Green JM, Thompson CB, Kappler JW, Marrack P. CD28 engagement and proinflammatory cytokines contribute to T cell expansion and long-term survival in vivo. J Immunol. 1997;158:4714–4720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haynes L, Eaton SM, Burns EM, Rincon M, Swain SL. Inflammatory cytokines overcome age-related defects in CD4 T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:5194–5199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maue AC, Eaton SM, Lanthier PA, Sweet KB, Blumerman SL, Haynes L. Proinflammatory adjuvants enhance the cognate helper activity of aged CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:6129–6135. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]