Abstract

Objective

To determine the outcome of definitive concurrent chemoradiation with platinum for locally advanced sinonasal carcinomas.

Study Design

Retrospective cohort

Materials and Methods

23 nonsurgically and definitively treated patients diagnosed between July 1998 and February 2009 were analyzed. Patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma or adenocarcinoma were treated with photons and neutrons; the other histologies received photons alone. The vast majority received chemotherapy. Descriptive statistics were utilized, and Kaplan-Meier estimates were computed.

Results

Female (57%) and Caucasian (74%) preponderance were observed. Eighty seven percent were unresectable; the maxillary and naso-ethmoid sites were equally prevalent. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and photons alone were utilized in 74% and 70%, respectively. Platinum agents were given in 95% of chemotherapy patients. Complete response was observed in 64% of patients. Median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 28.8 and 65.3, months respectively. Three-year PFS and OS rates were 44% and 72%, respectively; 5-year PFS and OS rates were 30% and 60%, respectively. IMRT and a maxillary site of origin showed a trend towards superior PFS; higher-dose regimens were associated with somewhat shorter PFS. Relapse was observed in 59% of patients, predominantly local. There were few unanticipated adverse effects- no Grade IV/V events were reported.

Conclusion

Advanced sinonasal carcinomas are chemoradiosensitive tumors, albeit with a high propensity for local relapse. There is a definite indication for IMRT and a potential curative role of platinum-based chemoradiation regimens.

Keywords: carcinoma, sinonasal, unresectable, chemoradiation, cisplatin

Introduction

Cancers of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are uncommon tumors, and comprise about 3–5% of head and neck cancers1. Cure rates depend on stage and extent of local invasion. A 5-year survival rate of 40% and local control rate of 59% have been reported previously. Traditional management of locally advanced sinonasal carcinomas has been surgical resection and adjuvant radiation therapy (RT)2, 3. For advanced stage disease, cure rates have been disappointing, and complete surgical extirpation is associated with high rates of morbidity. Furthermore, tumors of these sites are unique with respect to proximity to vital structures and are frequently unresectable at presentation. For unresectable disease, options are limited and include RT or chemotherapy alone.

Sinonasal carcinomas are radiosensitive tumors, and there is a definite potential for cure with nonsurgical management. In recent years, combinations of RT and chemotherapy have demonstrated a survival benefit when compared with RT alone4. In unresectable disease, concurrent chemoradiation with cisplatin has emerged as standard of care, with 3-year overall survival rates of 37%5. A pertinent concern is the increased toxicity associated with chemoradiation regimens, and whether the potential benefits outweigh the risks and toxicities. This is especially important in sinonasal tumors, where the possibility of damage to the central nervous system is more likely.

In view of the recent advances in radiation and medical oncology, a comparison of concurrent chemoradiation versus surgical approach with or without adjuvant therapy is clinically relevant. In this study, we aim to retrospectively determine outcomes of nonsurgical treatment in locally advanced sinonasal carcinoma.

Methods and Materials

Patients from July 1998 to February 2009 with carcinoma involving the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses treated with radiation with or without chemotherapy with curative intent were included. Patients with surgical management alone were excluded. Patients with invasive epithelial malignancies were included; those with lymphoma, sarcoma, melanoma, esthesioneuroblastoma and other histological subtypes were excluded. Patients with noninvasive histology, distant metastases at presentation, or a follow-up of less than 5 years were also excluded. A total of 23 patients were included for final analysis.

Data was obtained from electronic medical records at Karmanos Cancer Institute. An appropriate nonsurgical protocol was formulated based on tumor stage, histology, age, and comorbidities. Tumors were retrospectively staged based on the 7th Edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)6. For the lone patient with a sphenoid tumor, the naso-ethmoid classification system was used. Tumors were considered unresectable (T4b) when there was involvement of the nasopharynx, orbital apex, dura, brain, middle cranial fossa, cranial nerves other than V2, or clivus.

Surgery was offered as a treatment option to the 3 patients with Stage III/IVA disease. However, patient preference and unwillingness to undergo surgery formed the basis of a chemoradiation protocol for these patients. The said protocols were specific to each patient, and were based on tumor stage and histology, and patient characteristics including age and comorbidities.

Radiation treatment details

Patients with adenoid cystic carcinoma or adenocarcinoma received treatment with photons and neutrons (‘mixed beam’). Other histological subtypes were treated with photons alone. All patients underwent virtual CT simulation without contrast. Techniques of neutron therapy at our institution are previously described7. IMRT or 3D CRT was delivered via 6 MV photon beams. All RT was delivered via the sequential boost technique. Simultaneously integrated IMRT boost technique was not used. Treatments were delivered once a day, 5 days per week, with 1.8–2 Gy per fraction for photons or 1 NGy per fraction for neutrons.

Response assessment and follow up

Tumor response was based on Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.18. The day after completion of radiation treatment was considered the start of follow-up period. Baseline imaging was obtained at 8–12 weeks following treatment and annually thereafter. Patients were followed for at least 5 years.

Statistical Methods

Relapse/progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the day after completion of therapy to the date of documented disease relapse or progression. Patients free of progressive disease were censored as of the date of their last assessment. Overall survival (OS) was measured from day after completion to date of death. Patients not known to have died were censored as of most recent exam. Patients who were last confirmed to be alive> 12 months prior to recording date were considered lost to follow-up (LFU). Standard Kaplan-Meier (K-M) estimates of censored PFS and OS distributions were computed. Survival statistics were estimated using linear interpolation among successive event times9. The censored duration of PFS or OS was compared via log-rank test.

This study was approved by Institutional Review Board at Wayne State University, Protocol Review and Monitoring Committee at Karmanos Cancer Institute, and Research Review Committee at Detroit Medical Center.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Tumor Stage

| Demographic | n | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 13 | 57 | |

| Male | 10 | 43 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 17 | 74 | |

| African American | 6 | 26 | |

| Smoking history | |||

| Never | 7 | 32 | |

| Former | 11 | 50 | |

| Current | 4 | 18 | |

| Alcohol use | |||

| None | 7 | 32 | |

| Social/occasional | 12 | 54 | |

| Regular | 3 | 14 | |

| T stage | |||

| T3 | 2 | 9 | |

| T4a | 1 | 4 | |

| T4b | 20 | 87 | |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | 22 | 96 | |

| N2b | 1 | 4 | |

| Overall stage | |||

| III | 2 | 9 | |

| IVA | 1 | 4 | |

| IVB | 20 | 87 | |

| Site of origin of primary tumor | |||

| Maxillary sinus | 11 | 48 | |

| Ethmoid sinus | 4 | 17 | |

| Nasal cavity | 7 | 30 | |

| Sphenoid sinus | 1 | 4 | |

| Histological subtype | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 10 | 43 | |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 6 | 26 | |

| Sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma |

4 | 17 | |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 2 | 9 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | 4 | |

There was a slight female predominance (F: M=1.3:1), and majority was Caucasian. Age ranged from 31 to 88 years. Sixty eight percent of the patients were former or current smokers, with a mean exposure of 22 pack years. Regular alcohol use was reported in 14%. A history of occupational exposure to wood dust or environmental carcinogens could not be elicited. Tumors originated in maxillary (n=11, 48%) and naso-ethmoid (n=11, 48%) regions with similar frequency. The histologic subtype encountered most commonly was squamous cell carcinoma (43%), followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma (26%) and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma (17%). Eighty seven percent of tumors were unresectable (T4b). Only one patient (4%) had cervical nodal disease (N2b) at presentation.

Radiation treatment

IMRT was utilized in the majority (74%) of patients, with 3D CRT being used in the remainder. Seventy percent of patients received photons alone, and the remainder received ‘mixed beam’. Conventional fractionation was used in the majority of patients (95%). The median dose equivalent for ‘photon only’ and ‘mixed beam’ patients was 70 and 66 Gy respectively. All patients completed their planned RT.

Chemotherapy

The majority of patients (91%) received chemotherapy. All patients were treated with concurrent regimens, with induction in 6 (29%) patients. Cisplatin was the most frequently utilized chemotherapeutic agent (70%), followed by 5-fluorouracil (39%), and carboplatin (22%). Cetuximab, capecitabine, gemcitabine, and paclitaxel were used in 2 patients (9%), and etoposide, adriamycin, and methotrexate in 1 patient (4%). There were no dose reductions; however, the number of cycles had to be reduced in 4 patients (20%) due to toxicity.

The median follow-up time for OS for the 15 patients who were alive or LFU at the last follow-up date was 50.9 months. Three patients were deemed lost to follow up.

Treatment outcomes data

Response

Response was not evaluable in one patient due to inadequate follow-up. Of the remaining 22 patients, there was complete response in 14 (64%). Seven patients (32%) had a partial response, and 1 (4%) had stable disease. The single patient with cervical nodal disease (N2b) had complete response.

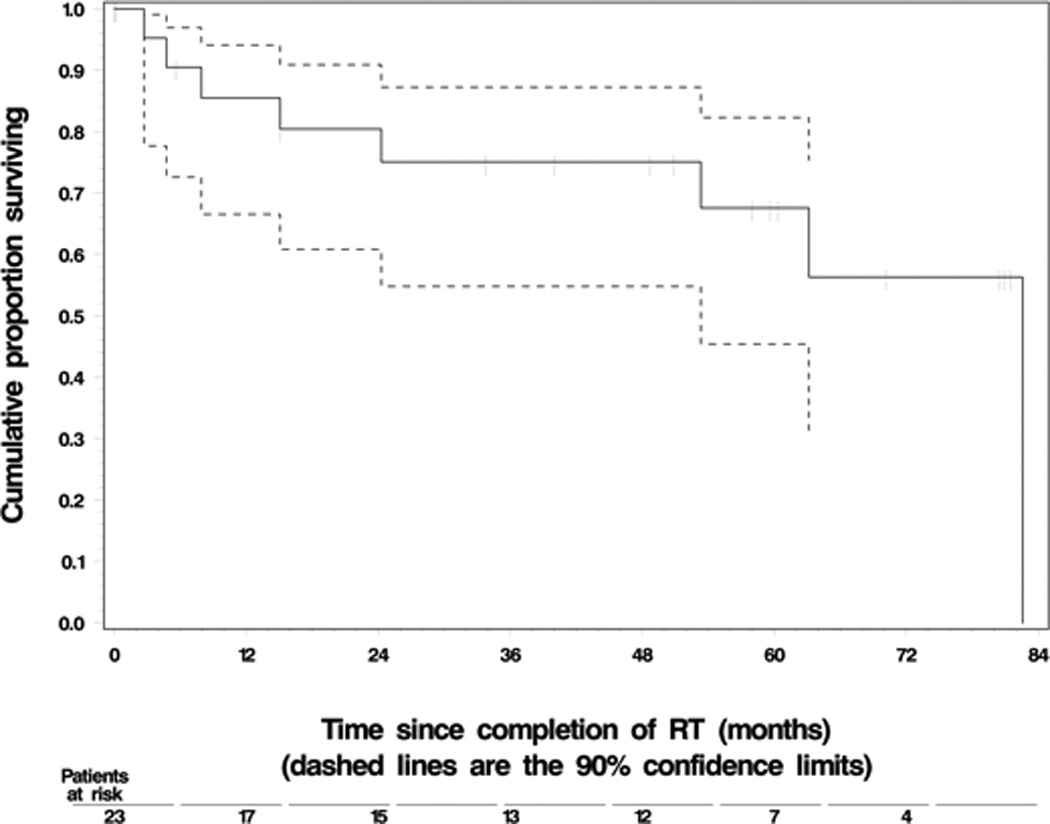

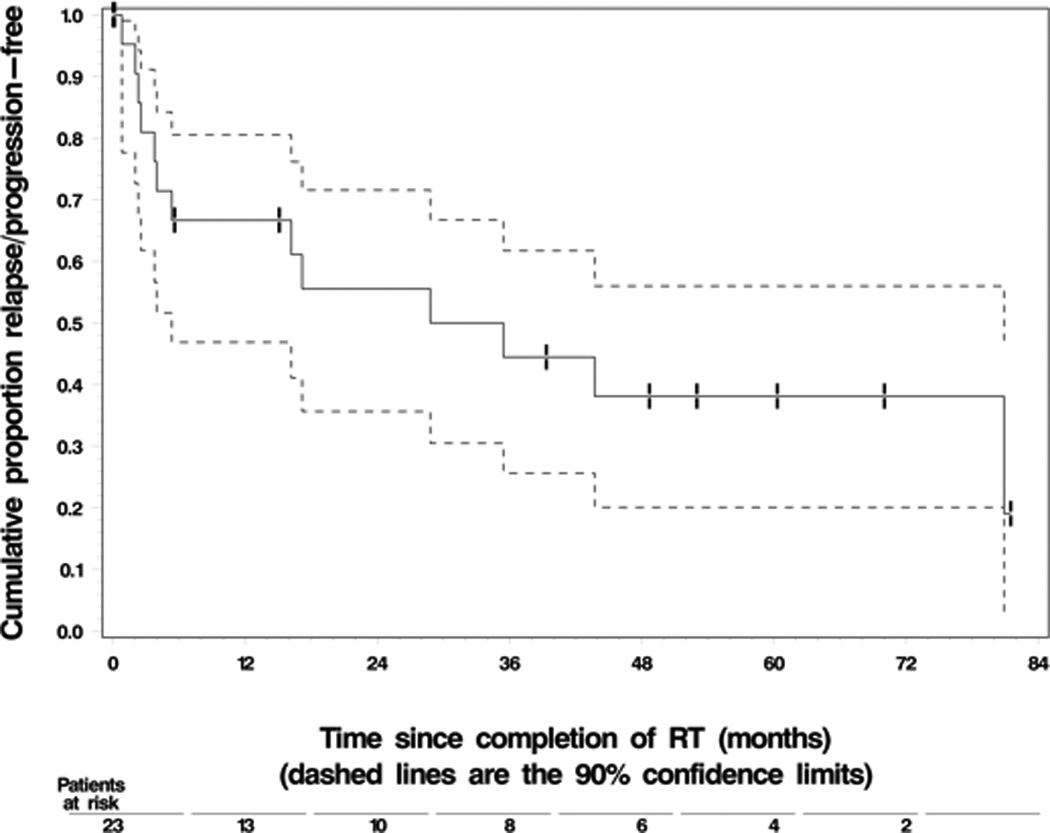

Survival

Twelve patients (52%) were alive at last follow up, 8 (35%) had expired, and 3 patients (13%) were LFU. The median OS and median PFS were 65.3 months and 28.8 months respectively. The 3-year and 5-year PFS rates were 44% and 30%, respectively; and 3 and 5-year OS rates were 72% and 60%, respectively. Figures 1 and 2 show K-M curves for OS and PFS.

For the 20 Stage IV B patients, the median OS and median PFS were 65.7 months and 33.8 months, respectively. Their 3-year and 5-year PFS rates were 48% and 32%, respectively. Their 3-year and 5-year OS rates were identical to those for all 23 patients combined.

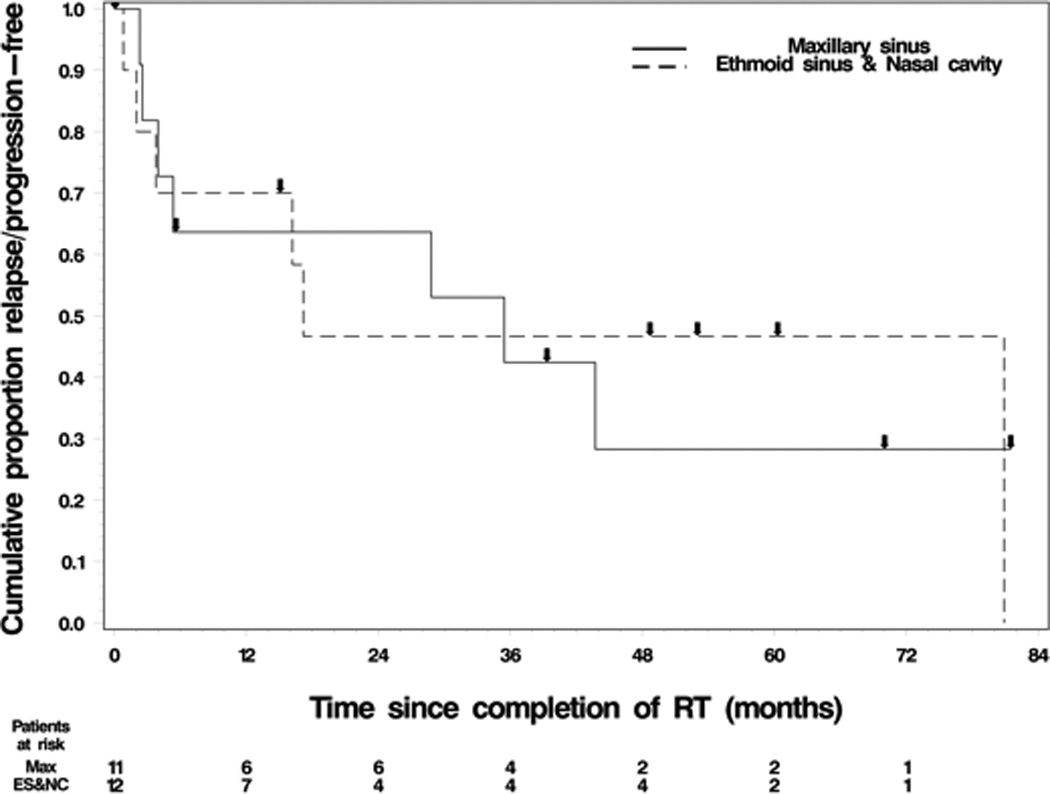

PFS and OS were estimated with respect to site of origin, RT dose, and RT modality. For site comparison, median PFS was 30.7 months for maxillary sinus tumors, while median PFS was 16.9 months for nasal cavity and ethmoid sinus tumors. The 3-year OS rate was 66% for maxillary and 71% for naso-ethmoid tumors. Figure 3 presents the K-M curves of PFS by origin site.

Figure 3. Relapse/progression-free survival based on site of origin.

a. Key: Line = maxillary sinus, Dashed Line = ethmoid sinus and nasal cavity

b. Abbreviations: Radiotherapy (RT)

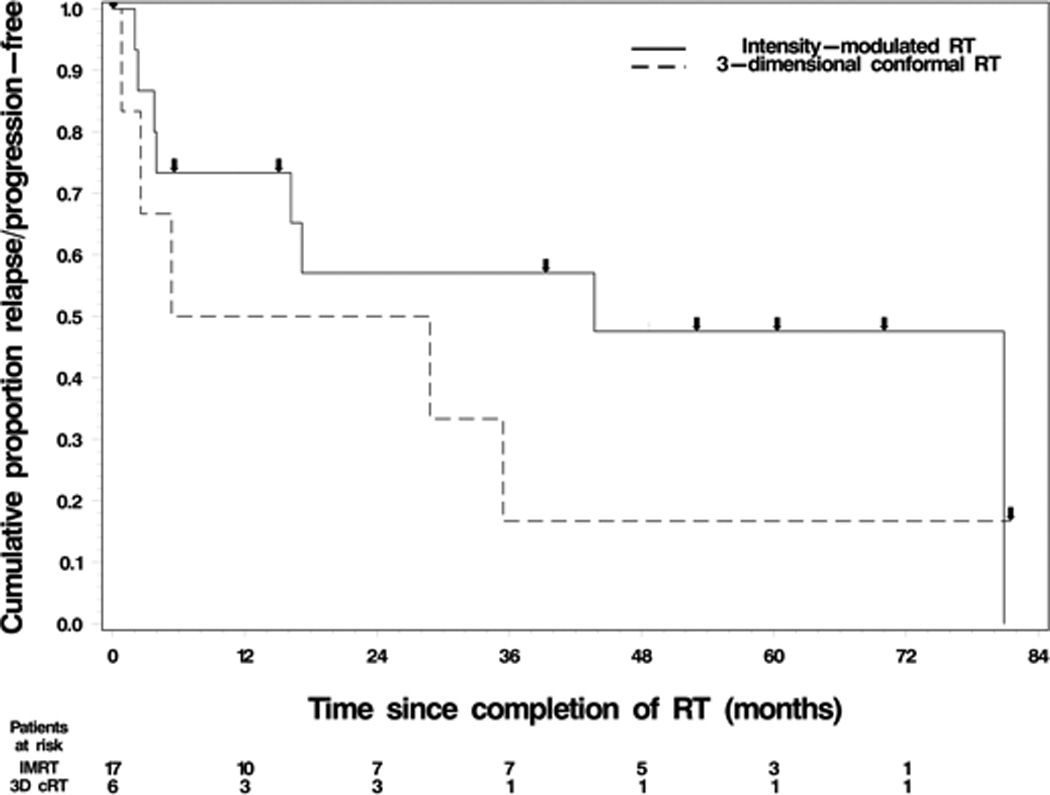

For IMRT versus 3D CRT comparison, median PFS was 36.8 months for the former and 5.4 months for the latter. Three-year OS rates were 73% and 59% respectively. K-M comparison curves of PFS are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Relapse/progression-free survival based on radiotherapy modality.

a. Key: Line = intensity modulated RT, Dashed Line = 3-dimensional conformal RT

b. Abbreviations: Radiotherapy (RT)

For RT dose comparison, patients treated with total dose 65 Gyor less were compared with those greater than 65 Gy. Median PFS for patients receiving 65 Gy or less (32.4 months) was somewhat superior compared with the patients receiving greater than 65 Gy (23.6 months). Three-year PFS and OS rates were 48% and 78% respectively for lower dose group, compared to 36% and 62% for the higher dose group.

Relapse/Progression (Table 2)

Table 2.

Patient Treatment and Outcome

| Characteristic | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse/progression status | |||

| No | 9 | 41 | |

| Yes | 13 | 59 | |

| Site(s) of initial relapse/progression | |||

| Local | 8 | 62 | |

| Regional | 1 | 8 | |

| Distant | 3 | 23 | |

| Multiple sites (Local + New primary) | 1 | 8 | |

| Stage of initial relapse/progression | |||

| II | 1 | 8 | |

| IVA | 3 | 23 | |

| IVB | 6 | 46 | |

| IVC | 3 | 23 | |

| Treatment intent | |||

| No treatment | 1 | 8 | |

| Curative | 8 | 62 | |

| Palliative | 4 | 31 | |

Percentages may not always sum to 100 due to rounding.

At last follow-up date, 13 (59%) patients had relapsed or progressed. An estimate of median survival after relapse or progression (36.5 months) was obtained by utilizing median OS and median PFS values. The predominant patterns of relapse/progression were local (69%) or distant relapse (23%), with only one patient experiencing a regional relapse. Greater than 90% of patients who progressed or relapsed had recurrent Stage IV disease. The majority of relapsed/progressed patients (62%) were treated with curative intent.

Toxicities

Toxicities were graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.0, published by the National Cancer Institute10. There were no reported Grade IV or V events.

RT toxicity (Table 3)

Table 3.

Incidence of Radiation and Chemotherapy Toxicities

| Radiation toxicity | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Xerostomia | 14 | 70 |

| Dermatological toxicity | 11 | 55 |

| Mucositis | 7 | 35 |

| Dysphagia | 4 | 20 |

| Unknown | 3 | 15 |

| None | 2 | 10 |

| Trismus | 2 | 10 |

| Conjunctivitis | 2 | 10 |

| Blindness | 1 | 5 |

| Xerophthalmia | 1 | 5 |

| Chemotherapy toxicity | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| None | 6 | 30 |

| Dehydration/ renal failure | 5 | 25 |

| Ototoxicity/ hearing loss | 5 | 25 |

| Hematological toxicity | 4 | 20 |

| Skin rash | 1 | 5 |

| Gastrointestinal toxicity | 5 | 25 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 3 | 15 |

| Mucositis | 1 | 5 |

| Unknown | 1 | 5 |

No chemotherapy – 2 patients

Xerostomia (70%), skin toxicity (55%), and mucositis (35%) were the most common toxicities associated with RT. Dysphagia (20%) was mostly transient. Ocular toxicities were encountered, including conjunctivitis (10%), xeropthalmia (5%), and blindness (5%). Rare toxicities included trismus (10%) and temporal lobe radionecrosis.

Chemotherapy toxicity (Table 3)

Renal dysfunction, ototoxicity, and gastrointestinal toxicity were observed in 5 (25%) patients. Of the patients with renal dysfunction, 3 had received cisplatin and 2 carboplatin. Ototoxicity was primarily manifested as sensorineural hearing loss, and all of these patients received cisplatin. Hematological toxicity, manifested as neutropenia or febrile neutropenia, was observed in 4 (20%) patients. All patients with heme toxicity received combination chemotherapy. Peripheral neuropathy occurred in 3 (15%) patients, all of whom had received cisplatin. Maculopapular skin rash was noted in one of two patients who received Cetuximab, and mucositis was seen accompanying 5-fluorouracil administration in 1 patient.

Discussion

The widely regarded standard of care for carcinomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses is surgical extirpation, followed by adjuvant therapy as indicated. Few studies have dealt with nonsurgical management of these tumors11, 12. In addition, owing to the proximity of important anatomical structures, the option of nonsurgical management needs to be further investigated.

We retrospectively analyzed 23 patients with locally advanced carcinomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Our sample size was small owing to multiple factors. Carcinomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are rare, comprising only 3–5% of head and neck cancers and often present as unresectable disease1. The remainder (13%) of our patients, who presented with locally advanced but operable (Stage III and IVA) disease, elected not to undergo surgery2, 8. Given these limitations, our sample size compared favorably3, 11–16.

Patient and tumor characteristics

We found a slight predominance of female patients (56%). This is in agreement with some (49%)11 and in contrast with other (14%)12 series. Our patients were predominantly Caucasian (74%), which is similar to other reports3. Sixty eight percent of our patients were former or current smokers, as seen with other studies12, 13, 17. We also examined nicotine exposure in our patient population, and observed a mean of 22 pack years. We did not find literature for comparison of nicotine exposure.

Tumor characteristics exhibited some concordance with literature. In accordance with our findings, two published series showed maxillary sinus as being the most common site of origin and squamous cell carcinoma as the most common histology11, 16. In contrast, two European studies13, 14 demonstrated ethmoid sinus and adenocarcinoma as most common. All of these studies are limited by small sample size. Due to this limitation, it is difficult to draw conclusions. It is known that adenocarcinoma does tend to be the predominant histology in ethmoidal malignancies, and is especially known to occur with occupational exposure to wood dust18, 19. None of our patients provided such history.

When discussing tumor site, multiple sinuses are frequently involved, and predicting site of origin is difficult. In these cases, an assumption is made based on the epicenter of disease. The vast majority of our patients (87%) had Stage IVB disease, which is understandable considering patients with early-staged disease would be expected to undergo surgery. This is consistent with other reports11, 20, 21.

Response and survival

We observed a complete response in just below two-thirds of patients, and a partial response in another third. Only one patient did not respond. To our knowledge, the initial response rate has never been reported. Due to the paucity of available literature, it is not possible to compare our proportion of complete responders with other studies.

From studying OS, 72% and 60% of our patients were alive at 3 and 5 years respectively, with a median OS of 65.3 months. This compared quite favorably with other studies11,12. Our observations, along with the findings in other studies, indicate the aggressive nature of sinonasal carcinomas, and their tendency to relapse or progress locally. In our opinion, conclusions cannot be made from observed differences due to small patient populations.

Seventy four percent of our patients received IMRT and the remainder were treated with 3D CRT. IMRT has been increasingly used in the treatment of sinonasal carcinomas, as it can achieve homogenous dose distributions sparing vital neurovascular structures. It has been shown to not compromise local control or overall survival14. Cumulative radiation dose has been the subject of considerable debate, due to concern for dose-related toxicities, and whether dose intensified regimens improve survival. A number of studies12, 13, 22, 23 have demonstrated the absence of a statistically significant survival benefit for higher-dose regimens. One study by Jansen et al23 reported a worse overall survival with a cumulative RT dose exceeding 65Gy. Similarly, in our study, the lower dose group (≤ 65 Gy) had a better 3-year PFS rate (48%) and OS rate (78%) compared with the higher dose group (> 65 Gy), who had 3-year PFS and OS rates of 36% and 62%, respectively. The results reported merit careful interpretation. Sinonasal carcinomas have potentially life-threatening dose-related toxicities. The observation of inferior survival with higher dose regimens could be a manifestation of the same. It may also be construed that regimens of greater intensity may have been employed for more advanced disease. Our patients received 56–70 Gy (median 66 Gy), with other studies reporting wider RT dose ranges. Our study population consisted of a greater proportion of locally advanced disease (T4b in 87% patients) in comparison with the study by Jansen, even though Stage III and IV tumors did comprise the majority of their patients (86%). The dose range in Jansen’s study was 39–70 Gy, with a median of 66 Gy. The majority of their patients had received 3D CRT. In contrast, the series by Hoppe et al11 showed that patients receiving a dose ≥ 65 Gy had improved local PFS and OS than patients who received < 65 Gy. Another study by Szutkowski et al24 showed that doses greater than 60 Gy had a clear beneficial impact on treatment results. In light of these contrasting findings, there is need for more investigation.

Regarding survival, few studies have focused on site of origin with respect to survival. Recent studies12, 19, 22 have dealt only with one subsite. Studies by Dirix et al13 and Madani et al14 compared ethmoidal malignancies with other sinonasal locations. While there was a tendency for a lower rate of local control, statistical significance was not found. Our findings were in support of the above observations.

In our series, we had 13 (59%) of patients who were known to have progressed or relapsed. Most of these patients had local progression or relapse (69%). This would be typical of squamous cell carcinoma, which was the most prevalent histopathological subtype in our series of patients. The abovementioned relapse/progression rates are in accordance with reported literature3, 25. There can be multiple proposed factors associated with high local recurrence rate observed in series where surgery was part of definitive management13, 21. They would include a complex three-dimensional anatomy, relative proximity to sites signifying preoperative unresectability, the difficulty in en bloc resection in advanced tumors, and the lack of feasibility in performing margin analysis post-resection. The substantial progression or relapse rates observed in other studies on nonsurgical management11, 12 can be explained on the basis of a high proportion of unresectable tumors in study populations. We observed that our progression/relapse rates were comparable with other series on nonsurgical management.

Regarding toxicity, xerostomia was the most common radiation-induced toxicity found in our study (70%), followed by dermatological toxicity (manifested as skin darkening in 55%), and mucositis (35%). Even though the above three were graded as toxicities, it is commonplace to encounter all of the problems on a short-lived basis. In this regard, they are considered radiation sequelae, are typically managed conservatively without necessitating treatment breaks, and may subside in due course. Permanent radiation-induced toxicities warrant significantly greater concern – one patient experienced unilateral partial blindness and radionecrosis of the temporal lobe. Both short and long-term toxicities have been reported to be less prevalent in patients treated with IMRT and 3D-conformal RT15 than those treated with conventional RT. The rate and outcomes of these toxicities in our series is comparable3, 12, 14.

The rate and nature of toxicities secondary to chemotherapy was also similar to that reported3. The most common toxicities encountered were renal dysfunction, ototoxicity, and gastrointestinal toxicity. Most of these patients had received cisplatin as part of the chemotherapy regimen. The toxicities encountered were known toxicities associated with these agents26.

Limitations

Significant limitations included the low number of patients recruited, lack of diversity in tumor location, mixed histology of epithelial malignancies presented, and the retrospective nature of this study. For this reason, the results are largely descriptive. The sample size was understandably attributable to the uncommon nature of the disease and the application of additional filters and exclusion criteria as mentioned. Furthermore, with respect to comparison between variables, even a nearly equal dichotomy of patients would have low power. In regards to the combination of mixed histologies presented, the most common histology in our study was squamous cell carcinoma. Since patients with squamous cell carcinoma often have poorer outcomes than with other histologic subtypes, there is significant selection bias in our study population. Further studies of higher power with a more evenly-distributed histologic subtype could yield further conclusions and are under investigation.

Conclusions

We have attempted to report and classify outcomes of nonsurgical treatment of locally advanced and unresectable sinonasal carcinomas, a topic that is under-addressed due to the rarity of disease and predilection for surgery. Our survival outcomes compare favorably with other nonsurgical series, even though this remains an aggressive disease with a high rate of progression or relapse. In our experience, advanced naso-ethmoid carcinomas appear to have a trend towards inferior survival compared with a maxillary site of origin. There is also a proposed benefit for improved disease control with IMRT over 3D CRT. There remains the need for a more uniform and universally accepted cumulative RT dose cut-off, bearing in mind potential toxicities. With the increased acceptability and utilization of IMRT and image-guided techniques, the elusive balance between efficacy and toxicity should be attainable. There remains a need for studies with a larger patient base, preferably prospective and multi-institutional, to develop strategies that can ensure wide implementation.

Figure 1. Overall Patient Survival.

a. Key: Dashed lines represent 90% confidence limits

Figure 2. Relapse/Progression Free Survival.

a. Key: Dashed lines represent 90% confidence limits

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by NIH Cancer Center Support Grant CA-22453.

Footnotes

Research Location: Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 48201.

Conflicts of Interest: HS Lin has a consultant agreement as a proctor with Intuitive Surgical Inc.

Financial Disclosures: HS Lin has a consultant agreement as a proctor with Intuitive Surgical Inc.

Contributor Information

Shamit Chopra, Chair, Department of Head and Neck Surgery, Patel Hospital, Jalandhar, India.

Dev P. Kamdar, Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine, Hempstead, New York.

David S. Cohen, Department of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery, Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan..

Lance K. Heilbrun, Biostatistics Core, Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University.

Daryn Smith, Biostatistics Core, Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University.

Harold Kim, Department of Radiation Oncology, Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan..

Ho-Sheng Lin, Department of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery, Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan..

John R. Jacobs, Department of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery, Karmanos Cancer Institute, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan..

George Yoo, Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, AND Department of Oncology.

References

- 1.Muir CS, Nectoux J. Descriptive epidemiology of malignant neoplasms of nose, nasal cavities, middle ear and accessory sinuses. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1980 Jun;5(3):195–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1980.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dulguerov P, Jacobsen MS, Allal AS, Lehmann W, Calcaterra T. Nasal and paranasal sinus carcinoma: are we making progress? A series of 220 patients and a systematic review. Cancer. 2001 Dec 15;92(12):3012–3029. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011215)92:12<3012::aid-cncr10131>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoppe BS, Stegman LD, Zelefsky MJ, Rosenzweig KE, Wolden SL, Patel SG, Shah JP, Kraus DH, Lee NY. Treatment of nasal cavity and paranasal sinus cancer with modern radiotherapy techniques in the postoperative setting—the MSKCC experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007 Mar 1;67(3):691–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.09.023. Epub 2006 Dec 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignon JP, le Maître A, Maillard E, Bourhis J MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomized trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009 Jul;92(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. Epub 2009 May 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, Wagner H, Jr, Kish JA, Ensley JF, Schuller DE, Forastiere AA. An Intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 1;21(1):92–98. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual. (7th) 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forman JD, Duclos M, Sharma R, Chuba P, Hart K, Yudelev M, Devi S, Court W, Shamsa F, Littrup P, Grignon D, Porter A, Maughan R. Conformal mixed neutron and photon irradiation in localized and locally advanced prostate cancer: preliminary estimates of the therapeutic ratio. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996 May 1;35(2):259–266. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(96)00020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors- Version 1.1 update. www.recist.com/recist-in-practice. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee E, Wang JW. Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis. 3rd. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2003. pp. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0 (CTCAE) National Cancer Institute; Publish Date: May 28, 2009. http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.02_2009-09-15_QuickReference_5x7.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoppe BS, Nelson CJ, Gomez DR, Stegman LD, Wu AJ, Wolden SL, Pfister DG, Zelefsky MJ, Shah JP, Kraus DH, Lee NY. Unresectable carcinoma of the paranasal sinuses: outcomes and toxicities. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008 Nov 1;72(3):763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waldron JN, O'Sullivan B, Warde P, Gullane P, Lui FF, Payne D, Cummings B. Ethmoid sinus cancer: twenty-nine cases managed with primary radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998 May 1;41(2):361–369. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dirix P, Nuyts S, Guessens Y, Jorissen M, Vander Poorten V, Fossion E, Hermans R, Van Den Bogaert W. Malignancies of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: long-term outcome with conventional or three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:1042–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madani I, Bonte K, Vakaet L, Boterberg T, De Neve W. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for sinonasal tumors: Ghent University Hospital update. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:424–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rischin D, Porceddu S, Peters L, Martin J, Corry J, Weih L. Promising results with chemoradiation in patients with sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma. Head Neck. 2004 May;26(5):435–441. doi: 10.1002/hed.10396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabriele AM, Airoldi M, Garzaro M, Zeverino M, Amerio S, Condello C, Trotti AB. Stage III–IV sinonasal and nasal cavity carcinoma treated with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Tumori. 2008 May-Jun;94(3):320–326. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allen MW, Schwartz DL, Rana V, Adapala P, Morrison WH, Hanna EY, Weber RS, Garden AS, Ang KK. Long-term radiotherapy outcomes for nasal cavity and septal cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008 Jun 1;71(2):401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bimbi G, Saraceno MS, Riccio S, Gatta G, Licitra L, Cantù G. Adenocarcinoma of ethmoid sinus: an occupational disease. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2004 Aug;24(4):199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayr SI, Hafizovic K, Waldfahrer F, Iro H, Kütting B. Characterization of initial clinical symptoms and risk factors for sinonasal adenocarcinomas: results of a case-control study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010 Aug;83(6):631–638. doi: 10.1007/s00420-009-0479-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guntinas-Lichius O, Kreppel MP, Stuetzer H, Semrau R, Eckel HE, Mueller RP. Single modality and multimodality treatment of nasal and paranasal sinuses cancer: a single institution experience of 229 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKay SP, Shibuya TY, Armstrong WB, Wong H–S, Panossian AM, Ager J, Mathog RH. Cell carcinoma of the paranasal sinuses and skull base. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007;28:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magrini SM, Nicolai P, Somensari A, Scheda A, Bignardi M, Bonetti B, Frata P, Huscher A, La Face B, Tonoli S. Which role for radiation therapy in ethmoid cancer? A retrospective analysis of 84 cases from a single institution. Tumori. 2004 Nov-Dec;90(6):573–578. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansen EP, Keus RB, Hilgers FJ, Haas RL, Tan IB, Bartelink H. Does the combination of radiotherapy and debulking surgery favor survival in paranasal sinus carcinoma? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000 Aug 1;48(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szutkowski Z, Kawecki A, Wasilewska-Teśluk E, Kraszewska E. Results of treatment in patients with paranasal sinus carcinoma. Analysis of prognostic factors. Otolaryngol Pol. 2008;62(1):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6657(08)70206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porceddu S, Martin J, Shanker G, Weih L, Russell C, Rischin D, Corry J, Peters L. Paranasal sinus tumors: Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute experience. Head Neck. 2004;26:322–330. doi: 10.1002/hed.10388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Go RS, Adjei AA. Review of the comparative pharmacology and clinical activity of cisplatin and carboplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1999 doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]