SCIENTIFIC ABSTRACT

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have long been known to have deficits in the performance of praxis gestures; these motor deficits also correlate with social and communicative deficits. To date, the precise nature of the errors involved in praxis has not been clearly mapped out. Based on observations of individuals with ASD performing gestures, we hypothesized that the simultaneous execution of multiple movement elements is especially impaired in affected children. We examined 25 school-aged participants with ASD and 25 age-matched controls performing seven simultaneous gestures that required the concurrent performance of movement elements and nine serial gestures, in which all elements were performed serially. There was indeed a group × gesture-type interaction (p < 0.001). Whereas both groups had greater difficulty performing simultaneous than serial gestures, children with ASD had a 2.6-times greater performance decrement with simultaneous (vs. serial) gestures than controls. These results point to a potential deficit in the simultaneous processing of multiple inputs and outputs in ASD. Such deficits could relate to models of social interaction that highlight the parallel-processing nature of social communication.

Keywords: Dyspraxia, autism, motor planning, divided attention, multiple task interference

LAY ABSTRACT

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have long been known to have difficulty performing complex gestures, such as communicative gestures (e.g., waving hello) and tool-use gestures (e.g., using a hammer). Previous studies have documented the fact of these deficits, but the precise types of mistakes made by children with ASD are not clear. It is important to understand the precise nature of these mistakes because this understanding will allow us to dig deeper into the mechanisms that may underlie not only motor problems in ASD, but also the core social/communicative problems with which motor problems correlate.

Observing a few children with ASD, we noticed that they had particular difficulty with performing gestures in which two separate movements had to be made at the same time (e.g., opening and closing the hand as the arm moves in a particular pattern). We set out to demonstrate these deficits in a systematic way. By studying 25 school-aged children with ASD and 25 controls performing gestures that involved simultaneous movements (and control gestures that had only one movement at a time), we documented that children with ASD indeed have particular difficulty when two or more movements had to be performed at the same time.

Some hypotheses propose that social interactions are particularly difficult because they require many simultaneous tasks—listening to speech, forming a reply, observing body language. The current results suggest future research studying social and motor multitasking, as similar deficits in may underlie both issues in ASD.

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have been known to show motor abnormalities since Kanner’s earliest description (Kanner, 1943). Once treated as curious epiphenomena, research over the last few decades has demonstrated specificity in the types of motor deficits and has begun to theorize as to psychological and neurobiological links between motor and social/communicative features of the disorder (Mostofsky & Ewen, 2011). Repeated studies in ASD have demonstrated deficits in praxis (dyspraxia), the performance of complex gestures that often have a communicative or functional (e.g., tool-use) purpose (Dewey, Cantell, & Crawford, 2007; Dowell, Mahone, & Mostofsky, 2009; Dziuk et al., 2007; H. Ham et al., 2010; Ham, Bartolo, Corley, Swanson, & Rajendran, 2010; Mostofsky et al., 2006; Wheaton & Hallett, 2007). Imitation of equally complex yet meaningless gestures is also impaired in ASD (Mostofsky et al., 2006), suggesting that dyspraxia is not entirely related to the semantic content of gesture production. Further, the severity of production deficits of meaningful and meaningless gestures in ASD correlates with social/communicative symptoms (Dowell et al., 2009; Dziuk et al., 2007). Non-semantic motor-control impairments in ASD may therefore share a mechanistic basis with cardinal symptoms and motivate deeper investigations of precisely what those shared deficits may be. In the current work, “praxis” refers to the production both of meaningful and meaningless gestures.

Theoretical treatments, including (but not limited to) those invoking the mirror neuron system, propose high-level reasons for a relationship between praxis and social/communicative networks (Gallese, 2007; Klin, Jones, Schultz, & Volkmar, 2003; Mostofsky & Ewen, 2011). Lacking is a description of precisely how children with ASD perform praxis gestures incorrectly. A detailed understanding of the precise error types may lead to more specific hypotheses about what affected capacities in the ASD brain underlie both dyspraxia and social/communicative symptoms.

Prior work into autistic dyspraxia, particularly using a pediatric modification of the Florida Apraxia Battery (FAB) (Mostofsky et al., 2006), has rated gesture performance using instruments designed primarily for adults with acquired apraxia (e.g., due to stroke). In order to obtain a deeper understanding of the specific errors in the praxis task made by children with ASD, we reviewed a limited number of videos. We observed what we thought to be a specific pattern of impaired performance in ASD which was not specifically targeted by the FAB. When children with ASD imitated meaningless gestures that involved simultaneous manipulation of multiple end-effectors (typically arm plus individual fingers), they often manipulated the end-effectors serially, or simply failed to manipulate one end-effector at all. We therefore sought to substantiate, using a larger group and a more focused and rigorous coding scheme, the hypothesis that children with ASD show particular difficulty in performing gestures in which there is simultaneous movements of two end-effectors.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants included children with ASD as well as controls, aged 8.0–12.9 years. The cohorts were accrued from previously collected videos of children who participated in both the published FAB (Mostofsky et al., 2006), and a similar, unpublished gesture imitation task.

Participants in the ASD group were required to meet criteria for ASD based on the clinical judgment of an experienced ASD clinician and researcher (SHM) and either the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord, Rutter, & Le Couteur, 1994), the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-G, Module 3 (ADOS-G; Lord et al., 2000), or both. All participants in this sample met criteria for ASD based on the ADOS-G and clinical judgment.

Exclusion criteria for both groups included full-scale IQ<80 on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—IV (Wechsler, 2003), history of a definitive neurological disorder (seizures, tumors, traumatic brain injury, stroke) and presence of a severe chronic medical disorder, visual impairment, history of substance abuse or dependence, or presence of childhood schizophrenia or psychosis. Additional exclusion for the ASD group included history of known etiology for autism (e.g., Fragile X) and history of documented prenatal/perinatal insult. We excluded children with ASD if they met criteria on Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—IV (DICA-IV; Reich, Welner, & Herjanic, 1997) for any diagnosis other than attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or anxiety, given the high comorbidity of these disorders with ASD. Additional exclusion for the TD group included a Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS; Constantino & Gruber, 2005) scores outside the normal range, history of a developmental disorder or a psychiatric disorder (evaluated via the DICA-IV) and having an immediate family member with an autism spectrum disorder. We also excluded subjects from both groups whose videos we examined initially to develop the hypothesis.

From our video archive, number of TD subjects who had completed both gesture tasks (below) were the limiting factor. To the TD subjects, we matched subjects with ASD by age and non-verbal IQ.

Task

For this study, we coded the previously-recorded videos of the modified FAB (Mostofsky et al., 2006) in which subjects sat across a table from a research assistant and imitated gestures. We analyzed 10 meaningless gestures from the imitation section of the FAB and an additional 6 meaningless gestures from an unpublished imitation task. The unpublished task was administered identically to the Gesture to Imitation section of the FAB, and the gestures contained therein were developed to be similar in nature and difficulty to those in the FAB. Gestures from both tasks contained multiple movement elements that were either performed simultaneously (simultaneous gestures), or all gesture elements were performed sequentially (serial gestures). The latter gestures formed the control condition. Of the 10 gestures from the FAB, 4 gestures were simultaneous and 6 serial. Of the 6 gestures from the unpublished task, 3 were classified in each category. In an example of a simultaneous gesture, subjects moved their right arm above their head, back-and-forth in the coronal plane. As they moved the arm to the left, they splayed their fingers, and as they moved it to the right, they brought their fingers together. In a serial gesture, subjects tapped the table with the hand clenched in a fist, then with the back of the hand, then the palm. All gestures are described in Supplementary Material I.

Scoring

We developed a scoring rubric to characterize simultaneous vs. serial gesture performance. We defined movement elements for each gesture. Most commonly, a gesture contained an arm trajectory element and a hand-posture element. The scoring rubric for each serial gesture consisted of a list of each movement element, which was marked as present (1) or absent (0). Our approach to scoring simultaneous gestures is the result of a functional/goal-directed view of the behavior. A person must be able to perform all simultaneous elements of a gesture in order to be functionally successful (e.g., positioning a nail while striking with a hammer). In this context, being able to execute only part of a simultaneous movement is functionally inadequate. Our current scoring rubric reflects this view and highlights the importance of simultaneous coordination. The rubric for each simultaneous gesture similarly scored presence and absence of movement element. Additionally, it accounted for simultaneity of elements by grouping elements which were to be performed concurrently and multiplying the sum by 1 (correct simultaneous performance) or by 0 (serial or dropped element). Some simultaneous gestures included two elements performed concurrently then another two performed concurrently. If the one of the first two elements was dropped but both of the second pair were performed correctly, no credit would be given for the first pair, but full credit would be given for the second. Scoring was performed by a single research assistant who was not informed of the diagnosis and who was research-trained in the coding of gesture videos. There were a total 18 possible points across 7 gestures in the simultaneous category, and 23 possible points across 9 gestures in the serial category, with 2–4 possible points per gesture. Due to varying number of items per category, we normalized each category’s score by the total number of possible points for that category.

Our primary outcome measure was the group×gesture-type interaction effect (repeated-measures ANOVA). We also examined, post hoc, group differences for each gesture type and gesture-type differences in each group (two-sided Student’s t-test; Cohen’s d).

To establish reliability, second psychological associate trained in praxis video scoring independently reviewed a subset of gestures, and Pearson’s correlation between the scores (%correct) was computed.

Results

Participants

Analyses included data from all 25 typically developing (TD) controls who met criteria and completed the previously unpublished task. The mean age for children with ASD was 10.3 years; for control children, 9.9 years (two-sided t-test p=0.26). Children with ASD had a significantly lower FSIQ than controls (ASD:100±17; TD:113±8; p=0.001), however there were no differences between groups in the three non-verbal indexes (Perceptual Reasoning Index: HFA:106±14; TD:110±9; p=0.23). For imitation performance analyses that control for IQ factors, see Supplementary Material III. 20% of subjects with ASD were female; 36% of TD subjects were female (Fisher’s Exact Test p=0.35). Within the ASD group, some subjects met criteria on the DICA-IV for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (17 children), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (5), Simple Phobia (1), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (2) and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (5); DICA-IV results were not available for one child in the ASD group. No TD participant met criteria for any diagnosis on the DICA-IV.

Behavioral Results

Overall, children with ASD imitated gestures less accurately than TD controls (F1,48=13.302, p<0.0001, ηp2 =0.22), and all subjects combined performed simultaneous gestures less well than serial gestures (F1,48=80.708, p<0.0001, ηp2=0.63). Post hoc, controls showed greater accuracy serial than simultaneous gestures (p<0.001, d=0.82), as did children with ASD (p<0.001, d=1.68).

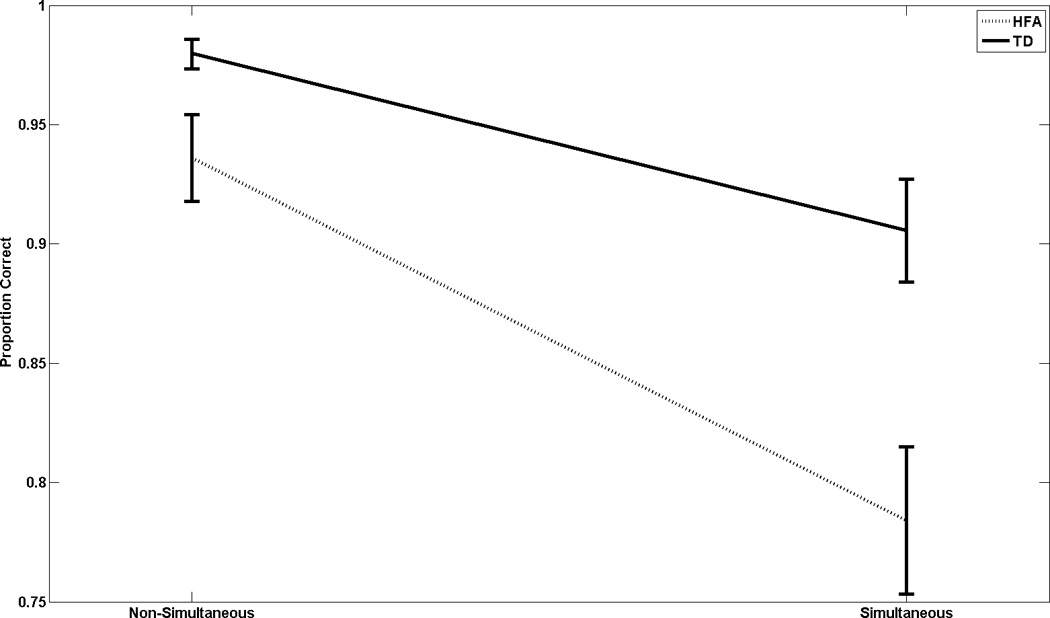

There was a significant interaction between diagnosis and gesture type (F1,48=12.346, p<0.001, η p2=0.21), demonstrating that, consistent with our hypothesis, children with ASD show a greater performance decrement when performing simultaneous gestures than do controls (Fig. 1). Also, post hoc, TD subjects performed better than children with ASD in both the serial (p=0.027; d=0.65) and simultaneous conditions (p<0.001; d=1.05).

Figure 1.

Proportion of correct responses to total points available, plotted by gesture type (x-axis) and diagnostic group (separate curves). ANOVA demonstrates, as our principal finding, a significant group × gesture-type interaction: while both groups have increased difficulty with simultaneous gestures, children with ASD have a greater incremental difficulty than controls. Moreover, children with ASD have less accuracy with both gesture types than controls.

The second rater scored full datasets from 24% of subjects (7 ASD, 5 TD). r=0.86 (p<10−6).

Discussion

The primary aim of this work was to determine whether children with ASD had difficulty imitating meaningless gestures, particularly when those gestures required the coordinated production of multiple movement elements. Indeed, the current results show this to be the case. Each group performed simultaneous gestures less well than serial gestures (difference in %correct, serial-minus-simultaneous:TD=11%;ASD=29%). The simultaneous-vs.-serial performance-cost ratio was 2.6 times greater in the ASD group than in controls. Deficits associated with simultaneous processing may therefore explain part of the impaired imitation long noted in ASD.

Impaired simultaneous processing of multiple input-output streams may have significance beyond motor function in ASD. Observations in patients with frontal lobe damage (Baddeley, Della Sala, Papagno, & Spinnler, 1997) have motivated accounts of social impairment due to deficient simultaneous monitoring of multiple inputs (e.g., semantics, facial expression) while also dynamically preparing motor and verbal responses. The deficits in simultaneous imitation via visuo-motor streams in the current work may mirror such putative social processing deficits (Mundy, Sullivan, & Mastergeorge, 2009) and may therefore serve as a link to study correlations between motor impairment and social/communicative deficits in ASD (Dowell et al., 2009; Dziuk et al., 2007). While the current work studies only a single input-output modality (visuo-motor), there is evidence for impaired cross-modal integrated perception (Silverman, Bennetto, Campana, & Tanenhaus, 2010) and synchronized production (de Marchena & Eigsti, 2010) between gestures and speech.

Future work linking this phenomenon with theoretical treatments of ASD may benefit from the literature and paradigms of multiple disciplines. For example, investigations into the relationship between executive function deficits in ASD and simultaneous motor control may be placed within the context of the experimental psychology of multitasking (Geurts, de Vries, & van den Bergh, 2014). Separately, a motor control framework could relate this phenomenon with well-studied bimanual interference (Ivry, Diedrichsen, Spencer, Hazeltine, & Semjen, 2004). Such bimanual interference effects depend on the level of abstraction at which the cues are coded (Ivry et al., 2004), which may relate to psycholinguistics. Finally, this phenomenon is described within the context of visuo-motor imitation, which links to social learning theory (Khan & Cangemi, 1979) and visuo-motor integration (Dumas, Martinerie, Soussignan, & Nadel, 2012).

Work underway will address limitations of the current work. Using purpose-designed gestures, we can systematically manipulate the simultaneity of elements. Moreover, using systematic manipulations of task demands, we can assess the relative contributions of potential limitations in encoding (e.g., divided attention, working memory) vs. in coordinated motor execution. In new cohorts, we will additionally characterize ADHD features, which could explain some of the deficits in simultaneous processing.

In conclusion, children with ASD demonstrate greater inaccuracy in imitating gestures requiring the simultaneous performance of multiple elements. A generalized difficulty in handling multiple input-output streams may contribute to impaired social cognition in ASD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Sponsor: NINDS/NIH; Grant numbers: K23NS073626 (to JBE), R21NS091569 (to JBE)

Grant Sponsor: NINDS/NIH; Grant number: R01NS048527 (to SHM)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no relevant conflict of interests.

Literature Cited

- Baddeley A, Della Sala S, Papagno C, Spinnler H. Dual-task performance in dysexecutive and nondysexecutive patients with a frontal lesion. Neuropsychology. 1997;11(2):187–194. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino J, Gruber C. Social Responsiveness Scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- de Marchena A, Eigsti IM. Conversational gestures in autism spectrum disorders: asynchrony but not decreased frequency. Autism Res. 2010;3(6):311–322. doi: 10.1002/aur.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey D, Cantell M, Crawford SG. Motor and gestural performance in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental coordination disorder, and/or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13(2):246–256. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070270. doi:S1355617707070270 [pii]10.1017/S1355617707070270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell LR, Mahone EM, Mostofsky SH. Associations of postural knowledge and basic motor skill with dyspraxia in autism: implication for abnormalities in distributed connectivity and motor learning. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(5):563–570. doi: 10.1037/a0015640. doi:2009-12548-003 [pii]10.1037/a0015640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas G, Martinerie J, Soussignan R, Nadel J. Does the brain know who is at the origin of what in an imitative interaction? Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:128. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziuk MA, Gidley Larson JC, Apostu A, Mahone EM, Denckla MB, Mostofsky SH. Dyspraxia in autism: association with motor, social, and communicative deficits. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(10):734–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00734.x. doi:DMCN734 [pii]10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallese V. Embodied simulation: from mirror neuron systems to interpersonal relations. Novartis Found Symp. 2007;278:3–12. discussion 12–19, 89–96, 216–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts H, de Vries M, van den Bergh S. Executive functioning theory and autism. In: Goldstein S, Naglieri J, editors. Handbook of executive functioning. New York: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ham H, Bartolo A, Corley M, Rajendran G, Szabo A, Swanson S. Exploring the Relationship Between Gestural Recognition and Imitation: Evidence of Dyspraxia in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham HS, Bartolo A, Corley M, Swanson S, Rajendran G. Case report: selective deficit in the production of intransitive gestures in an individual with autism. Cortex. 2010;46(3):407–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.06.005. doi:S0010-9452(09)00187-7 [pii]10.1016/j.cortex.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivry R, Diedrichsen J, Spencer R, Hazeltine E, Semjen A. In: Neuro-Behavioral Determinants of Interlimb Coordination: A multidisciplinary approach. Swinnen S, Duysens J, editors. New York: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective conduct. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Khan KH, Cangemi JP. Social Learning Theory: The role of imitation and modeling in learning socially desirable behavior. Education. 1979;100(1):41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Jones W, Schultz R, Volkmar F. The enactive mind, or from actions to cognition: lessons from autism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358(1430):345–360. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Jr, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, Rutter M. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(3):205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky SH, Dubey P, Jerath VK, Jansiewicz EM, Goldberg MC, Denckla MB. Developmental dyspraxia is not limited to imitation in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12(3):314–326. doi: 10.1017/s1355617706060437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky SH, Ewen JB. Altered connectivity and action model formation in autism is autism. Neuroscientist. 2011;17(4):437–448. doi: 10.1177/1073858410392381. doi:1073858410392381 [pii]10.1177/1073858410392381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P, Sullivan L, Mastergeorge AM. A parallel and distributed-processing model of joint attention, social cognition and autism. Autism Res. 2009;2(1):2–21. doi: 10.1002/aur.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich W, Welner Z, Herjanic B. The Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents—IV. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman LB, Bennetto L, Campana E, Tanenhaus MK. Speech-and-gesture integration in high functioning autism. Cognition. 2010;115(3):380–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler intelligence scale for children, fourth edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton LA, Hallett M. Ideomotor apraxia: a review. J Neurol Sci. 2007;260(1–2):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.014. doi:S0022-510X(07)00276-6 [pii]10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.