Abstract

Objective

To test whether frailty, a novel measure of physiologic reserve, is associated with longer kidney transplant (KT) length of stay (LOS), and modifies the association between LOS and mortality.

Background

Better understanding of LOS is necessary for informed consent and discharge planning. Mortality resulting from longer LOS has important regulatory implications for hospital and transplant programs. Which recipients are at risk of prolonged LOS and its impact on mortality are unclear. Frailty is a novel preoperative predictor of poor KT outcomes including DGF, early hospital readmission, immunosuppression intolerance, and mortality.

Methods

We used registry-augmented hybrid methods, a novel approach to risk adjustment, to adjust for LOS risk factors from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (n=74,859) and tested whether 1) frailty, measured immediately prior to KT in a novel cohort (n=589), was associated with LOS (LOS: negative binomial regression; LOS≥2 weeks: logistic regression) and 2) whether frailty modified the association between LOS and mortality (interaction term analysis).

Results

Frailty was independently associated with longer LOS (RR=1.15, 95%CI: 1.03-1.29; P=0.01) and LOS≥2 weeks (OR=1.57, 95%CI:1.06-2.33; P=0.03) after accounting for registry-based risk factors, including DGF. Frailty also attenuated the association between LOS and mortality (nonfrail HR:1.55 95%CI:1.30-1.86, P<0.001; frail HR=0.97, 95%CI:0.79-1.19, P=0.80; P for interaction=0.001).

Conclusions

Frail KT recipients are more likely to experience a longer LOS. Longer LOS among nonfrail recipients may be a marker of increased mortality risk. Frailty is a measure of physiologic reserve that may be an important clinical marker of longer surgical length of stay.

Keywords: Kidney Transplantation, Length of Stay, Mortality, Frailty

INTRODUCTION

Better understanding of hospital length of stay (LOS) after a kidney transplant (KT) is necessary for informed consent, patient and caregiver counseling, and discharge planning. The sequelae of longer LOS may also have important implications for hospital reimbursements1 as well as regulatory flagging.2 While there has been a reduction in LOS over time,3 there remains a subset of KT recipients who experience a prolonged stay. Longer LOS is often attributed to greater disease burden in the recipient4-6 or organ issues including delayed graft function (DGF).7 However, the full picture of which preoperative recipient, donor, and transplant factors are associated with LOS is unclear, as is the independent role of DGF on LOS.

In addition to traditional national registry-based predictors of KT LOS, novel factors such as frailty may also be associated with longer LOS. Frailty, a phenotype of decreased physiologic reserve and inability to overcome physiologic stressors,8 is distinct from comorbidity and represents a novel preoperative predictor of poor KT outcomes including DGF, early hospital readmission, immunosuppression intolerance, and mortality.9-12 KT represents a large physiologic stressor and, thus, it is possible that recipients who are frail are at risk of a prolonged LOS, perhaps independent of other known predictors of LOS. Also, given the increased mortality risk associated with both frailty10 and LOS13 among KT recipients, it is possible that the association between LOS and mortality differs by frailty status.

The goals of this study were to 1) better understand the trends, risk factors, and subsequent mortality associated with LOS using national registry data on 74,859 KT recipients, and 2) test whether frailty is associated with LOS and is an effect modifier of the association between LOS and mortality in a prospective novel cohort of 589 KT recipients.

METHODS

National Registry Data

We used national registry data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) to better understand LOS as detailed below. The SRTR data system includes data on all donor, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. The benefits of including the entire registry is that we can examine trends in LOS for over 20 years, and identify recipient, transplant and donor factors that predict LOS on the national level with a large sample size and generalizability.

LOS for 173,868 first-time, kidney only, adult KT recipients between 1995-2014 was ascertained from SRTR. Recipients with LOS >365 days were excluded from all analyses (n=59) as previously done.13 We considered recipient factors (age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), peak panel reactive antibody (PRA), diabetes, and time on dialysis), transplant factors (number of HLA mismatches, cold ischemia time [CIT], and DGF), and donor factors (donor type, age, and race) as potential risk factors for longer LOS. We excluded KT recipients with missing data on any of the key variables. As is standard with SRTR data, mortality was augmented through linkage with the Social Security Death Master File and data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Novel Cohort Study Data

Additionally, we studied frailty, which is not collected in the national registry data, from 589 KT recipients who participated in a prospective, longitudinal cohort study at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, between December 2008 and May 2014. All participants provided written informed consent and this study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board; all procedures were conducted in accord with the ethical standards of the Committee on Human Experimentation and in accord with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. We linked SRTR data (KT LOS, recipient, transplant, and donor factors) to frailty measurements from this prospective cohort study. Frailty was measured on all participants using the physical frailty phenotype as described below. The benefit of studying LOS in the novel cohort study data is that we can ascertain granular measures of risk, like frailty.

Frailty in the Novel Cohort Data

At admission for KT (immediately prior to KT), frailty was measured by trained research assistants as defined and validated by Fried in older adults8, 14-23 and by our group in end stage renal disease and KT populations.9-11, 24-26 Frailty was based on 5 components: shrinking (self-report of unintentional weight loss of more than 10 lbs in the past year based on dry weight); weakness (grip-strength below an established cutoff based on gender and BMI); exhaustion (self-report); low activity (Kcals/week below an established cutoff); and slowed walking speed (walking time of 15 feet below an established cutoff by gender and height).8 Each of the 5 components was scored as 0 or 1 representing the absence or presence of that component. The aggregate frailty score was calculated as the sum of the component scores (range 0-5); nonfrail was defined as a score of 0 or 1, intermediately frail was defined as a score of 2, and frail was defined as a score of 3 or higher, as we have previously reported.10-12, 24-26 In this study, we empirically combined the intermediately frail and frail groups (because both groups were associated with a similar risk of prolonged LOS) as we have previously done12 and refer to this group as frail throughout the manuscript.

Distribution and Trends in KT LOS between 1995-2014 in National Registry Data

We estimated the trends in median and interquartile range (IQR) of LOS and prevalence of LOS exceeding 2 weeks by year of KT (between 1995 and 2014). We also plotted the distribution of LOS overall and by year (between 1995-2014). These analyses in trends in LOS were conducted among 173,868 KT recipients using national registry data.

Risk Factors for Longer LOS in National Registry Data

We identified which recipient, transplant, and donor factors were associated with LOS using data from all KT recipients between 2002-2014 (n=133,214). We estimated the associations using negative binomial regression (relative risk [RR]) when LOS was the outcome and logistic regression (odds ratio [OR]) when LOS exceeding 2 weeks was the outcome. In addition to the models limited to factors known at the time of KT, we also explored models that include DGF given the potential association between DGF and LOS; we considered DGF (a post-KT risk factor) as a mediator with pre-KT factors.

LOS and Mortality in National Registry Data

Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate adjusted hazard rate (HR) of mortality by LOS exceeding 2 weeks. We adjusted for all recipient, transplant, and donor factors that were associated with LOS.

Frailty, LOS, and Mortality in the Novel Cohort Data

The independent association between frailty and KT LOS was estimated using a hybrid registry-augmented regression model as we have previously described.10 Briefly, using our SRTR negative binomial model for LOS (n=74,859 KT recipients between 2008-2014) we precisely estimated the coefficients of recipient, transplant, and donor factors and introduced these coefficients back into the single-center model (using forced values). We only included recipients who received KT between 2008 and 2014 to coincide with the years of the primary cohort which included measured frailty. The coefficients of the confounders were constrained to be the coefficients observed in the SRTR model through the use of a model offset. The only coefficient estimated using our single-center data was frailty (frail/intermediately frail vs. non-frail). Robust standard errors (Huber-White sandwich estimator) were used. Similar adjusted models with and without DGF were estimated using LOS. Additionally, hybrid registry-augmented logistic regression models with and without DGF for LOS exceeding 2 weeks as the outcomes were estimated to test for mediation of the association between frailty and LOS by DGF (a post-KT risk factor).

Effect Modification of LOS and Mortality by Frailty Status in the Novel Cohort Data

We also tested for effect modification on the multiplicative scale for the association between LOS and mortality by frailty using a hybrid registry-augmented Cox proportional hazards model using a similar approach to what is described above. The only coefficients estimated using our single-center data were for the main effects of LOS and frailty as well as the interaction of LOS with frailty.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using STATA 13.0. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved the cohort study and the use of SRTR data.

RESULTS

Distribution and Trends in KT LOS in National Registry Data

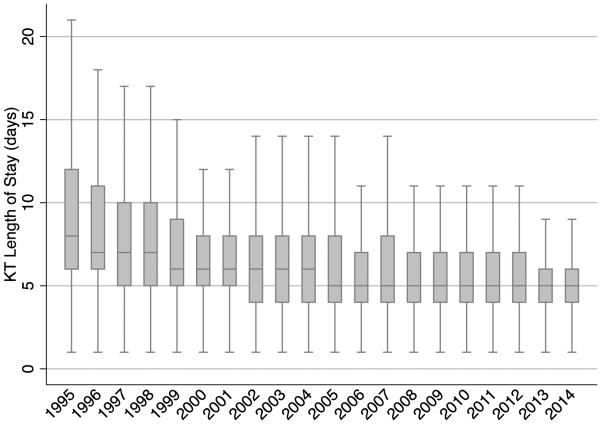

Of 173,868 KT recipients between 1995-2014, the median LOS was 5 days (IQR: 4-8) (Figure 1). The median LOS decreased over time (Figure 2A). In 1995, the median LOS was 8 days (IQR: 6-12); in the subsequent years it dropped steadily from 8 days to 7, 6 and then 5 days in 2005. The median LOS then remained at 5 days (IQR: 4-6) through 2014.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Kidney Transplantation Length of Stay Using SRTR Data between 1995-2014 (n=173,868). The figure shows the distribution of KT length of stay within 30 days. 1% had LOS between 30-365 days. Those with a LOS >365 days (n=59) were excluded from all analyses.

Figure 2A.

Distribution of Kidney Transplant (KT) Length of Stay By Year of KT Using SRTR Data between 1995-2014 (n=173,868). Note: Outliers (data points that fall outside the lower quartile-1.5*IQR, upper quartile+1.5*IQR) were excluded from the figure.

The prevalence of LOS exceeding 2 weeks also decreased over time (Figure 2B). In 1995, 21.4% of recipients were hospitalized for 2 weeks or longer; this decreased each year until 2000, where only 9.6% were hospitalized for 2 weeks or longer. By 2014, only 5.4% were hospitalized for 2 weeks or longer (Table 1).

Figure 2B.

The Prevalence of Length of Stay Exceeding 2 Weeks, by Year of Kidney Transplant Using SRTR Data between 1995-2014 (n=173,868).

Table 1.

Recipient, Transplant, and Donor Factors by Length of Stay Exceeding 2 weeks using National Registry Data (n=133,803) between 2002-2014 and Novel Cohort Data.

| National Registry Data (n=133,214) |

Novel Cohort Study (n=589) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| LOS exceeding 2 weeks | LOS exceeding 2 weeks | |||

|

| ||||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

|

| ||||

| Recipient factors | ||||

| Age ≥65 | 16.8 | 22.5 | 22.8 | 17.4 |

| Female | 39.0 | 40.6 | 36.0 | 50.0 |

| African American race | 25.0 | 34.6 | 36.7 | 45.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| <18.5 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| 18.5-24 | 30.6 | 27.8 | 34.3 | 33.1 |

| 25-29 | 34.2 | 32.7 | 34.1 | 25.6 |

| 29-34 | 22.4 | 24.1 | 20.1 | 25.0 |

| ≥35 | 10.8 | 13.2 | 8.2 | 12.8 |

| Peak PRA >80 | 6.2 | 9.0 | 14.2 | 36.6 |

| Diabetes | 33.9 | 43.3 | 15.8 | 22.1 |

| Years on dialysis | ||||

| 0 (preemptive KT) | 16.8 | 6.9 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| 0-1 | 16.4 | 9.8 | 12.5 | 7.6 |

| 1-2 | 16.0 | 13.8 | 10.8 | 6.4 |

| 2-3 | 13.2 | 14.6 | 9.4 | 7.0 |

| >3 | 37.6 | 54.9 | 67.2 | 78.5 |

| KT factors | ||||

| 0 HLA mismatches | 9.6 | 6.8 | 6.0 | 1.7 |

| CIT (hours) | ||||

| ≤12 | 47.1 | 35.3 | 54.7 | 50.0 |

| 12-23 | 31.3 | 40.3 | 17.8 | 18.6 |

| 24-36 | 9.6 | 14.2 | 21.6 | 22.1 |

| >36 | 12.0 | 10.2 | 6.0 | 9.3 |

| DGF | 14.3 | 52.2 | 11.8 | 29.7 |

| Donor factors | ||||

| Deceased standard criteria | 42.0 | 47.5 | 41.5 | 35.5 |

| Donation after cardiac death | 6.9 | 12.3 | 6.5 | 13.4 |

| Expanded criteria | 10.9 | 17.5 | 5.5 | 7.6 |

| Age (≥65 vs. <65) | 3.1 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 3.5 |

| African American race | 13.3 | 14.6 | 18.9 | 19.8 |

Percentages are presented.

Risk Factors for Longer LOS in National Registry Data and Novel Cohort Data

In the national registry data, older recipients (age ≥65 years) had a LOS that was 1.10-fold longer (95%CI: 1.09-1.12) than that of younger recipients (Table 2). Female recipients had a LOS that was 1.02-fold longer (95%CI: 1.01-1.03) and African American recipients had a LOS that was 1.05-fold longer (95%CI: 1.04-1.07). Recipients with a BMI ≥35 kg/m2 had a LOS of 1.03-fold longer (95%CI: 1.01-1.05) than those who had a BMI between 18.5 and 24 kg/m2. Additionally, peak PRA >80 (RR=1.08, 95%CI: 1.05-1.11) and diabetes (RR=1.09, 95%CI: 1.08-1.11) were associated with longer LOS. Compared to preemptive KT, longer time on dialysis was associated with a longer LOS: 0-1 year (RR=1.06, 95%CI: 1.03-1.08), 1-2 year (RR=1.14, 95%CI: 1.11-1.16), 2-3 year (RR=1.19, 95%CI: 1.16-1.22), and >3 year (RR=1.28, 95%CI: 1.25-1.30). Additionally, longer CIT was associated with a longer LOS: 12-23 hours (RR=1.06, 95%CI: 1.04-1.08), 24-36 hours (RR=1.10, 95%CI: 1.08-1.12), and >36 hours (RR=1.06, 95%CI: 1.05-1.08). Compared to live donor recipients, deceased standard criteria donor recipients had a LOS that was 1.08-fold longer (95%CI: 1.06-1.10), DCD donor recipients had a LOS that was 1.18-fold longer (95%CI: 1.15-1.21), and ECD recipients had a LOS that was 1.17-fold longer (95%CI: 1.14-1.20). Recipients with DGF had a LOS that was 1.66-fold longer (95%CI: 1.63-1.69) independent of all of the factors known at the time of KT.

Table 2.

Correlates of Kidney Transplantation Length of Stay, Using SRTR Data (n=133,214) between 2002-2014.

| Ratio (95% CI) of LOS (days) | OR (95% CI) of LOS exceeding 2 weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Recipient factors | Without DGF | With DGF | Without DGF | With DGF |

| Age (≥65 vs. <65) | 1.10 (1.09-1.12) | 1.10 (1.08-1.12) | 1.32 (1.26-1.40) | 1.34 (1.27-1.41) |

| Female | 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) | 1.06 (1.02-1.11) | 1.20 (1.14-1.25) |

| African American race | 1.05 (1.04-1.07) | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | 1.25 (1.19-1.31) | 1.15 (1.09-1.21) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.08 (1.03-1.13) | 1.08 (1.04-1.13) | 1.24 (1.07-1.44) | 1.27 (1.09-1.49) |

| 18.5-24 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 25-29 | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | 0.98 (0.92-1.03) | 0.93 (0.88-0.98) |

| 29-34 | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 0.97 (0.96-0.99) | 1.05 (0.99-1.12) | 0.94 (0.88-1.00) |

| ≥35 | 1.03 (1.01-1.05) | 0.98 (0.97-1.00) | 1.15 (1.07-1.24) | 0.94 (0.87-1.02) |

| Peak PRA >80 | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) | 1.33 (1.23-1.44) | 1.32 (1.21-1.43) |

| Diabetes | 1.09 (1.08-1.11) | 1.07 (1.06-1.09) | 1.32 (1.26-1.38) | 1.22 (1.17-1.28) |

| Years on dialysis | ||||

| 0 (preemptive KT) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 0-1 | 1.06 (1.03-1.08) | 1.03 (1.01-1.05) | 1.42 (1.28-1.57) | 1.23 (1.11-1.36) |

| 1-2 | 1.14 (1.11-1.16) | 1.09 (1.07-1.12) | 1.80 (1.63-1.98) | 1.46 (1.32-1.62) |

| 2-3 | 1.19 (1.16-1.22) | 1.12 (1.10-1.15) | 2.09 (1.89-2.31) | 1.59 (1.44-1.76) |

| >3 | 1.28 (1.25-1.30) | 1.16 (1.13-1.19) | 2.60 (2.38-2.85) | 1.75 (1.59-1.92) |

| KT factors | ||||

| 0 HLA mismatches | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | 0.77 (0.71-0.84) | 0.81 (0.74-0.88) |

| CIT (hours) | ||||

| ≤12 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 12-23 | 1.06 (1.04-1.08) | 1.03 (1.01-1.05) | 1.17 (1.10-1.24) | 1.04 (0.98-1.10) |

| 24-36 | 1.10 (1.08-1.12) | 1.03 (1.00-1.05) | 1.38 (1.28-1.48) | 1.07 (0.99-1.15) |

| >36 | 1.06 (1.05-1.08) | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | 1.31 (1.22-1.42) | 1.18 (1.09-1.27) |

| DGF | - | 1.66 (1.63-1.69) | - | 5.66 (5.39-5.94) |

| Donor factors | ||||

| Live donor KT | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Deceased standard criteria |

1.08 (1.06-1.10) | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | 1.17 (1.09-1.25) | 0.91 (0.85-0.98) |

| Donation after cardiac death |

1.18 (1.15-1.21) | 1.04 (1.02-1.07) | 1.68 (1.55-1.83) | 0.96 (0.88-1.05) |

| Expanded criteria | 1.17 (1.14-1.20) | 1.09 (1.06-1.11) | 1.45 (1.33-1.57) | 0.99 (0.91-1.08) |

| Age (≥65 vs. <65) | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) | 1.01 (0.98-1.05) | 1.03 (0.92-1.16) | 1.02 (0.91-1.15) |

| African American race | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | 1.01 (0.95-1.08) |

The ratio (95% CI) of days hospitalized was estimated using negative binomial regression and odds risk (OR) (95% CI) of 2 week length of stay was estimated using logistic regression. DGF was ascertained post-KT and thus, including DGF in the model tests for mediation by this post-KT risk factor.

Similar risk factors for LOS exceeding 2 weeks were observed (Table 2). Notably, longer time on dialysis was associated with an increased odds of LOS exceeding 2 weeks; 0-1 year (OR=1.42, 95%CI: 1.28-1.57), 1-2 year (OR=1.80, 95%CI: 1.63-1.98), 2-3 year (OR=2.09, 95%CI: 1.89-2.31), and >3 year (OR=2.60, 95%CI: 2.38-2.85). DGF was associated with 5.66-fold (95%CI: 5.63-5.94) increased odds of LOS exceeding 2 weeks independent of all of the factors known at the time of KT.

In the novel cohort data, frail KT recipients had a LOS that was 1.14-fold longer (95%CI: 1.02-1.28; P=0.02) than nonfrail recipients, even after accounting for all other donor, recipient, and transplant factors known at the time of KT (Table 3). After additionally adjusting for DGF, frailty was still an independent risk factor for longer LOS (RR=1.15, 95%CI: 1.03-1.29; P=0.01). Additionally, frail KT recipients had 1.6-fold (OR=1.63, 95%CI: 1.13-2.37, P=0.01) greater odds of LOS exceeding 2 weeks even after adjusting for the factors known at the time of KT. This risk remained significant (OR=1.57, 95%CI: 1.06-2.33; P=0.03) even after additionally accounting for DGF.

Table 3.

Frailty and Kidney Transplant Length of Stay Using Novel Cohort Data (n=589).

| Ratio (95% CI) of LOS (days) | OR (95% CI) of LOS exceeding 2 weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Without DGF | With DGF | Without DGF | With DGF | |

| Frailty | 1.14 (1.02-1.28) | 1.15 (1.03-1.29) | 1.63 (1.13-2.37) | 1.57 (1.06-2.33) |

| P-value | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

The ratio (95% CI) of days hospitalized was estimated using negative binomial regression and odds risk (OR) (95% CI) of 2 week length of stay was estimated using logistic regression. DGF was ascertained post-KT and thus, including DGF in the model tests for mediation by this post-KT risk factor.

LOS and Mortality in National Registry Data and Novel Cohort Data

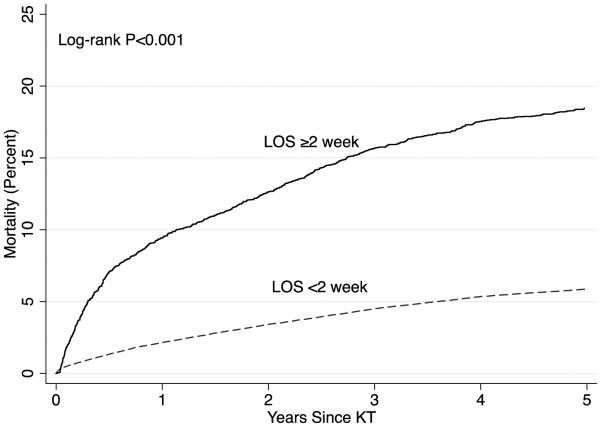

The unadjusted risk of mortality was greater in KT recipients with a LOS exceeding 2 weeks (P<0.001) (Figure 3) and remained significant even after accounting for all the factors that were associated with LOS, including DGF (HR=2.38, 95% CI: 2.20-2.58). For every 1 week increase in LOS there was a 1.08-fold (95% CI: 1.07-1.09, P<0.001) increased risk of mortality after accounting for all the factors that were associated with LOS, including DGF.

Figure 3.

Mortality by Kidney Transplant (KT) Length of Stay Using SRTR Data between 2008-2014 (n=74,859). A KT LOS exceeding 2 weeks is associated with an increased risk of mortality (Log-rank P-value <0.001).

In the novel cohort data, the risk of mortality associated with LOS differed for frail and nonfrail recipients (P for interaction=0.001) after accounting for factors known at the time of KT. Among those who were nonfrail, for every 1 week increase in LOS there was a 1.55-fold (95% CI: 1.30-1.86, P<0.001) increased risk of mortality. Among recipients who were frail, longer LOS was not associated with any increased risk of mortality (HR=0.97, 95% CI: 0.79-1.19, P=0.80).

DISCUSSION

In this national study of KT recipients, we identified a decreasing trend in LOS from 8 days in 1995 to 5 days in 2014. However, a substantial number of KT recipients still remain hospitalized for longer than 2 weeks. Recipients who were older, female, African American, obese, diabetic and of a deceased donor organ experienced longer LOS; also, longer time on dialysis and longer CIT as well as DGF were associated with longer LOS. As expected, DGF was associated with more than a 5-fold increased risk of LOS exceeding 2 weeks. Applying these findings to our prospective cohort, we found that recipients who were frail were 1.6-fold more likely to have a LOS exceeding 2 weeks. While frail recipients have a greater risk of post-KT mortality on average,10 non-frail recipients with a longer LOS are also at elevated mortality risk; there was effect modification of the association of LOS and mortality by frailty. Our study is consistent with previous findings of decreasing KT LOS through 2008,3 but we found that this decrease has plateaued (median of 5 days from 2005-2014). It is possible that the current LOS is the limit of what can be done with respect to shortening the LOS after KT.

There have been few studies of the risk factors for longer KT LOS.4-6, 27 While some studies have found that recipient comorbidities like obesity and diabetes were associated with longer KT LOS,4-6, 27 DGF has been identified as the strongest predictor of KT LOS.5 Our study confirmed these risk factors and also identified other recipient, transplant, and donor factors from the national registry data such as older age, longer time on dialysis, longer CIT, higher PRA, DCD, and ECD.

Most importantly, our study is the first to show that physiologic reserve, as measured by frailty, is a novel risk factor for longer LOS. We have previously shown that frailty is associated with DGF in KT recipients.9 We now extend these findings to show that frailty is associated with longer LOS independent of DGF. This suggests that, while frailty increases the risk of DGF, the association between frailty and LOS is not fully mediated through DGF. This independent association is plausible given that frailty is a measure of physiologic reserve that captures a patien’s ability to respond to stressors. Transplantation, like most surgeries, represents a major stressor and those who are frail are most likely to require more physical recovery time in the hospital, regardless of whether or not they experience DGF.

Previous studies have identified frailty as an important predictor of post-surgical outcomes in general surgery,28 gastrointestinal surgery,29 cardiac surgery,30, 31 as well as mortality among patients on the liver and lung transplant waitlist.32, 33 While this is the first study to show that frailty is associated with longer KT LOS, it is likely that this measure of physiologic reserve is also associated with longer LOS in other surgical settings.

One study identified an increased risk of post-KT mortality for those recipients with a longer LOS.13 Our findings confirm these findings in general, but show that they are modified by frailty. For nonfrail patients, LOS was indeed associated with higher risk of post-KT mortality. However, for frail patients, the mortality risk that accompanied this decrease in physiologic reserve was no different regardless of LOS. Although this may seem counterintuitive, it is likely that frailty captures a unique domain of risk. Therefore, if a recipient is frail they are already at an increased risk of mortality,10 and their prolonged LOS is not a driver of mortality beyond this baseline physiologic risk.

One notable limitation of this study was that frailty was only measured in our single center cohort. However, we were able to estimate with great precision and generalizability the associations between other characteristics and LOS, and these formed a strong framework for estimating this effect accurately for frailty. Strengths of this study were also the prospective measurement of a validated frailty instrument, as well as reliable ascertainment of the recipient, transplant, and donor factors. Additionally, our novel analytical method helped us properly yet efficiently adjust for many confounders without overfitting the model.

In conclusion, a number of recipient, transplant, and donor factors are associated with LOS, including frailty, a novel measure of physiologic reserve adapted from gerontology. Frail recipients and non-frail recipients with a long LOS both have a greater risk of post-KT mortality. These results may have important implications on informed consent, patient and caregiver counseling, and discharge planning by aiding in identifying which KT recipients are at increased risk of longer LOS and potentially, subsequent mortality. It is possible that in other surgical settings, frailty increases the risk of longer LOS and these patients could be targeted for special counseling and management planning.

MINI ABSTRACT.

Frailty immediately prior to kidney transplant (KT) was independently associated with longer KT length of stay (LOS) (RR=1.15, 95%CI:1.03-1.29; P=0.01) and LOS ≥2 weeks (OR=1.57, 95%CI:1.06-2.33; P=0.03) after accounting for traditional risk factors, including delayed graft function, using risk adjustment (n=74,859 KT recipients from SRTR between 2008-2014). Frailty also attenuated the association between LOS and post-KT mortality (nonfrail HR:1.55 95%CI:1.30-1.86, P<0.001; frail HR=0.97, 95%CI:0.79-1.19, P=0.80; P for interaction=0.001).

Acknowledgements

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation (MMRF) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government.

Support

This study was supported by NIH grant R01AG042504 (PI: Dorry Segev) and K24DK101828 (PI: Dorry Segev). Mara McAdams-DeMarco was supported by the American Society of Nephrology Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant and Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center, National Institute on Aging (P30-AG021334) and K01AG043501 from the National Institute on Aging. Elizabeth A. King was supported by NIA F32-AG044994 from the National Institute of Aging. Lauren M. Kucirka was supported by F32DK095545 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Sandra DiBrito was supported by F32DK105600 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Ashton Shaffer was supported by 5T32GM007309 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BMI

body mass index

- CIT

cold ischemia time

- DGF

delayed graft function

- IQR

interquartile range

- KT

Kidney Transplantation

- LOS

Length of Stay

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- PRA

peak panel reactive antibody

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

References

- 1.Hoch DA, Maynard E, Whiting J. Billing and reimbursement for advanced practice in solid organ transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2011;21(4):274–7. doi: 10.1177/152692481102100403. 283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orandi BJ, Garonzik-Wang JM, Massie AB, et al. Quantifying the risk of incompatible kidney transplantation: a multicenter study. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(7):1573–80. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janjua HS, Hains DS, Mahan JD. Kidney transplantation in the United States: economic burden and recent trends analysis. Prog Transplant. 2013;23(1):78–83. doi: 10.7182/pit2013149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pieloch D, Mann R, Dombrovskiy V, et al. The impact of morbid obesity on hospital length of stay in kidney transplant recipients. J Ren Nutr. 2014;24(6):411–6. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson CP, Kuhn EM, Hariharan S, et al. Pre-transplant identification of risk factors that adversely affect length of stay and charges for renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 1999;13(2):168–75. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matas AJ, Gillingham KJ, Elick BA, et al. Risk factors for prolonged hospitalization after kidney transplants. Clin Transplant. 1997;11(4):259–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimick JB, Chen SL, Taheri PA, et al. Hospital costs associated with surgical complications: a report from the private-sector National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(4):531–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.05.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garonzik-Wang JM, Govindan P, Grinnan JW, et al. Frailty and delayed graft function in kidney transplant recipients. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):190–3. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, King E, et al. Frailty and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(1):149–54. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(8):2091–5. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Tan J, et al. Frailty, mycophenolate reduction, and graft loss in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2015;99(4):805–10. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin SJ, Koford JK, Baird BC, et al. The association between length of post-kidney transplant hospitalization and long-term graft and recipient survival. Clin Transplant. 2006;20(2):245–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women's health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(3):262–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barzilay JI, Blaum C, Moore T, et al. Insulin resistance and inflammation as precursors of frailty: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):635–41. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cappola AR, Xue QL, Fried LP. Multiple hormonal deficiencies in anabolic hormones are found in frail older women: the Women's Health and Aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(2):243–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leng SX, Hung W, Cappola AR, et al. White blood cell counts, insulin-like growth factor-1 levels, and frailty in community-dwelling older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(4):499–502. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leng SX, Xue QL, Tian J, et al. Inflammation and frailty in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(6):864–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman AB, Gottdiener JS, McBurnie MA, et al. Associations of subclinical cardiovascular disease with frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M158–66. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, et al. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2333–41. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue QL, Bandeen-Roche K, Varadhan R, et al. Initial manifestations of frailty criteria and the development of frailty phenotype in the Women's Health and Aging Study II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(9):984–90. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.9.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang SS, Weiss CO, Xue QL, et al. Association between inflammatory-related disease burden and frailty: results from the Women's Health and Aging Studies (WHAS) I and II. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang SS, Weiss CO, Xue QL, et al. Patterns of comorbid inflammatory diseases in frail older women: the Women's Health and Aging Studies I and II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(4):407–13. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):896–901. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAdams-Demarco MA, Suresh S, Law A, et al. Frailty and falls among adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14(1):224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Tan J, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and Cognitive Function in Incident Hemodialysis Patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2181–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01960215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machnicki G, Lentine KL, Salvalaggio PR, et al. Kidney transplant Medicare payments and length of stay: associations with comorbidities and organ quality. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7(2):278–86. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.22079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):901–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner D, DeMarco MM, Amini N, et al. Role of frailty and sarcopenia in predicting outcomes among patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8(1):27–40. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung P, Pereira MA, Hiebert B, et al. The impact of frailty on postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(3):869–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.10.118. e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundermann S, Dademasch A, Praetorius J, et al. Comprehensive assessment of frailty for elderly high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39(1):33–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai JC, Feng S, Terrault NA, et al. Frailty predicts waitlist mortality in liver transplant candidates. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(8):1870–9. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer JP, Diamond JM, Gries CJ, et al. Frailty Phenotypes, Disability, and Outcomes in Adult Candidates for Lung Transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(11):1325–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1150OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]