Abstract

AIMS

The purpose of this investigation was to develop a non-invasive, objective, and unprompted method to characterize real-time bladder sensation.

METHODS

Volunteers with and without overactive bladder (OAB) were prospectively enrolled in a preliminary accelerated hydration study. Participants drank 2L Gatorade-G2® and recorded real-time sensation (0–100% scale) and standardized verbal sensory thresholds using a novel, touch-screen “sensation meter.” 3D bladder ultrasound images were recorded throughout fillings for a subset of participants. Sensation data were recorded for two consecutive complete fill-void cycles.

RESULTS

Data from 14 normal and 12 OAB participants were obtained (ICIq-OAB-5a = 0 vs. ≥3). Filling duration decreased in fill2 compared to fill1, but volume did not significantly change. In normals, adjacent verbal sensory thresholds (within fill) showed no overlap, and identical thresholds (between fill) were similar, demonstrating effective differentiation between degrees of %bladder capacity. In OAB, within-fill overlaps and between-fill differences were identified. Real-time %capacity-sensation curves left shifted from fill1 to fill2 in normals, consistent with expected viscoelastic behavior, but unexpectedly right shifted in OAB. 3D ultrasound volume data showed that fill rates started slowly and ramped up with variable end points.

CONCLUSIONS

This study establishes a non-invasive means to evaluate real-time bladder sensation using a two-fill accelerated hydration protocol and a sensation meter. Verbal thresholds were inconsistent in OAB, and the right shift in OAB %capacity–sensation curve suggests potential biomechanical and/or sensitization changes. This methodology could be used to gain valuable information on different forms of OAB in a completely non-invasive way.

Keywords: 3D ultrasound, non-invasive urgency characterization, perception of bladder fullness, urinary urgency, variable fill rate, verbal sensory thresholds

1 | INTRODUCTION

Overactive bladder (OAB) affects nearly 20% of the adult population.1,2 There are currently no accepted tools to evaluate the development of real-time urinary urgency, the key symptom of this condition. The evaluation of urinary urgency has relied mainly on the use of validated surveys reporting symptoms over an extended time. These methods only assess chronic urgency, as opposed to “real-time” urgency, and may be affected by recall bias. While bladder diaries serve to track bladder sensation in real-time, they may also be biased as patients typically record sensation after voiding occurs.

Conventional urodynamic (UD) studies are the accepted standard for characterization of bladder sensation. However, the use of catheters, supra-physiologic filling, and performance in an artificial setting may limit bladder sensory information. Furthermore, as defined by the International Continence Society (ICS),3 only three verbal sensory thresholds (VSTs) are recorded during UD testing: first sensation (FS), first desire to void (FD), and strong desire to void (SD).3 Unfortunately, there are no evidence-based guidelines describing how to interpret or compare VSTs. In an ideal test, filling volumes for identical VSTs (between fills) should be similar, and adjacent VSTs (within a fill) should be significantly different. However, there are no known publications that have specifically addressed this issue.

A detailed characterization of the development of unprompted real-time bladder sensation and correlation with VSTs in normal volunteers compared to volunteers with OAB using variable fill rates has not been performed outside of the UD laboratory and is the subject of the current preliminary investigation. The aim of this study was to develop a non-invasive, objective, and unprompted method to characterize real-time bladder sensation and compare this to standard VSTs in participants with and without OAB. The authors used a hydration protocol involving two consecutive fill-void cycles while participants reported continuous bladder sensation and VSTs on a hand-held device. Ultimately, the goal is to develop non-invasive methods, which in concert with a bladder diary, may provide additional information for the diagnosis and treatment of OAB.

2 | MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Virginia Commonwealth University. Normal volunteers without symptoms of urinary urgency and volunteers with complaints of OAB were recruited using printed flyers for an accelerated hydration study and asked to complete the ICIq-OAB survey.4 Normal subjects scored 0 (never) on question 5a (“Do you have to rush to the toilet to urinate?”) and ≤1 on all other questions. OAB subjects were those who scored ≥3 on question 5a (most of the time or always). Individuals answering between one and three on question 5a were not included. Participant age, gender, body mass index (BMI), race, prescription medications, and medical history were recorded.

2.1 | Accelerated hydration

Participants were first asked to void and post-void residual (PVR) volumes were assessed via a BladderScan® BVI 9400 (Verathon Inc., Bothell, WA) performed by a trained nurse or urologist. Averaged results of three successive scans were used for analysis. Participants with initial PVR volumes >20% estimated bladder capacity (voided volume + PVR) were excluded. Participants were then instructed to perform accelerated hydration by drinking 2L G2-Gatorade® as rapidly as possible. Gatorade-G2 was used to limit the rare risk of water intoxication and to avoid excessive sugar intake. Participants were observed by a medical doctor at all times during the study. Participants were seated comfortably through two successive fills. Voiding occurred in a private bathroom with volume collected in graduated containers. Immediately (typically within 1 min) after each void, PVRs were again measured via BladderScan® three times and averaged.

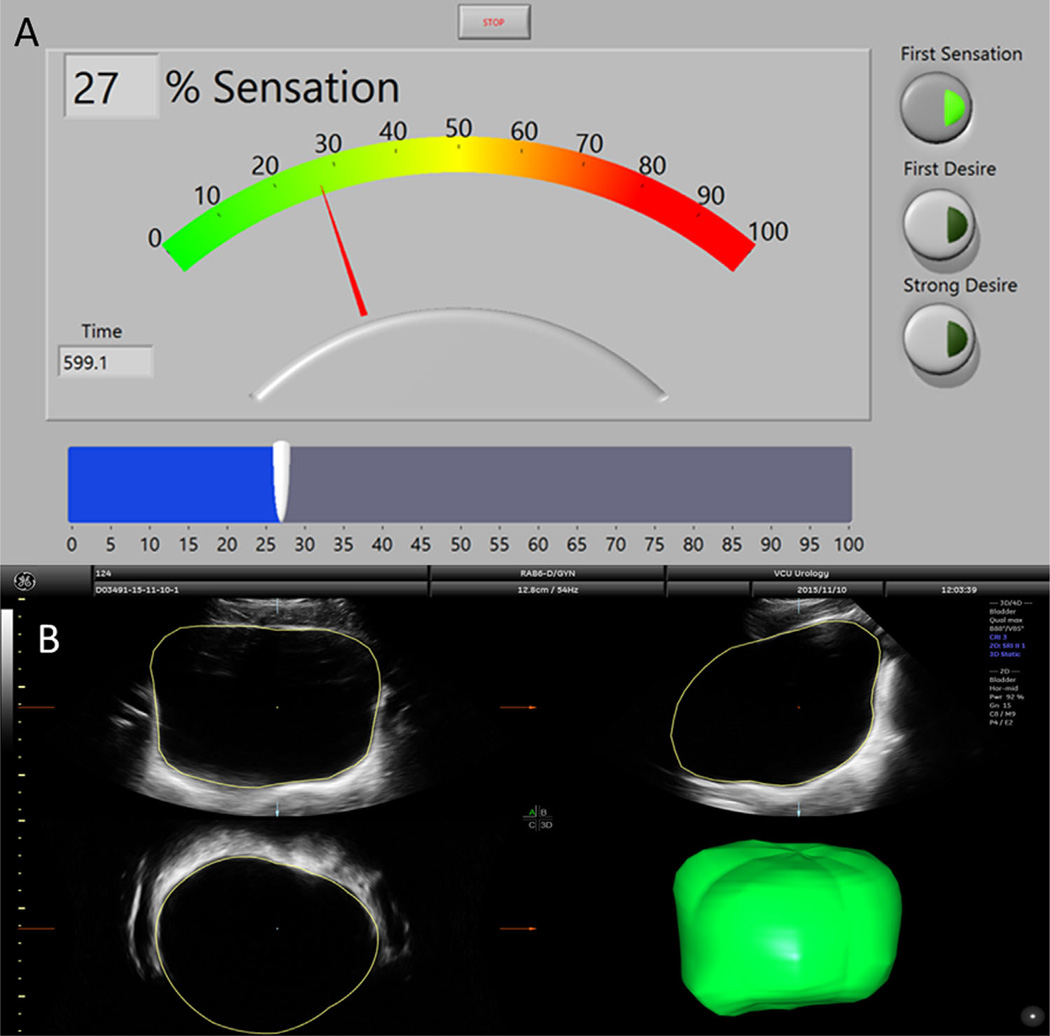

2.2 | Sensation meter

Participants were instructed on the use of a sensation meter prior to any interventions. The sensation meter is a graphical user interface implemented using LabView (National Instruments, Austin, TX) software on a tablet touch-screen Surface Pro3 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA), which allowed each participant to quantify his or her bladder sensation from 0% (feeling of complete bladder emptiness) to 100% (feeling of complete bladder fullness) every time a change in sensation was perceived (Fig. 1A). Continuous real-time sensation and time were recorded at 10 Hz during accelerated hydration with two successive fill and void cycles. This methodology, using two successive fills at variable rates, was employed in order to identify differences in sensation that could potentially be utilized to non-invasively characterize unique sensory patterns (ie, sub-types) of OAB. Participants were also asked to report standard VSTs based on written ICS definitions3 (handed to each participant) by pressing corresponding radio buttons (Fig. 1A, right). Participants were observed but not prompted. After study completion, ease of use and understanding were assessed using 10-point Likert scales.

FIGURE 1.

A. Screen shot of the sensation meter with radio buttons for verbal sensory thresholds (Right, FS is indicated in the example) and slider bar user interface for adjusting sensation from 0 to 100% (bottom, example at 27% sensation). B. An example image of how bladder volume is calculated using VOCAL in 4D View. The bladder is manually traced in several cross-sections which are automatically connected to form a continuous volume

Characterization of the following data occurred during two complete fill and void cycles: voided volumes, PVRs, bladder capacity, duration of filling, estimated filling volume (assuming constant fill rate calculated by capacity/duration), %capacity (estimated filling volume/bladder capacity of that fill), standard VSTs, and real-time sensation.

2.3 | Ultrasound

For the last three participants in each group, 3D ultrasound images of the bladder were obtained once every 5 min throughout both fills using a Voluson E8 system and a 4–8 MHz abdominal transducer (GE Healthcare, Zipf, Austria) by a certified ultrasound technologist. Bladder volume in the acquired images was measured using the Virtual Organ Computer-aided AnaLysis (VOCAL) software (4D View® Version 10.x, GE Healthcare). Bladder walls were traced manually by a trained individual in six cross-sectional image planes (rotation angle of 30°). These tracings were automatically combined to create a smooth solid by the software (Fig. 1B). Transient fill rate was calculated as the change in bladder volume divided by the change in time between temporally adjacent images.

2.4 | Statistics

The sample size used in this study was based on previous publications which detected differences in bladder volumes in subjects with OAB and normal controls.5,6 Jarque-Bera tests were used to determine normal distributions. Bivariate comparisons were performed with Student's t or Wilcoxon tests as appropriate. Multivariate comparisons were performed with repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparison post-test to identify differences between chosen data sets. Data are reported as mean ± standard error.

3 | RESULTS

Fourteen participants were enrolled in each group: eight men and six women in the normal group and seven men and seven women in the OAB group. All participants were naive to the hydration protocol and the sensation meter. One OAB woman was excluded for elevated PVR, and a second OAB female was excluded for having neurogenic bladder. Subject characteristics including gender, age, BMI, time to complete consumption of the 2 L of fluid, ICIq-OAB survey results, as well as sensation meter ease-of-use and understanding are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Subject characteristics

| Normals | OAB | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled | 14 (8 M/6 F) | 14 (7 M/7 F) | |

| Excluded | 0 | 2 (1 F, PVR; 1 F, NGB) | |

| Ultrasound subset | 3 (2 M/1 F) | 3 (2 M/1 F) | |

| Included | 14 (42.9% F) | 12 (41.7% F) | NS |

| Age | 24.7 ± 0.62 Yrs | 42.3 ± 4.67 Yrs | 0.00074 |

| BMI | 23.9 ± 0.90 kg/m2 | 36.2 ± 2.87 kg/m2 | 0.00029 |

| T Fluid | 27.1 ± 5.56 mina | 29.3 ± 3.94 min | NS |

| ICIq-OAB3a | 0.14 ± 0.10 | 2.00 ± 0.41 | 0.0008 |

| ICIq-OAB3b | 0.43 ± 0.31 | 8.25 ± 0.52 | <0.0001 |

| ICIq-OAB4a | 0.14 ± 0.10 | 2.63 ± 0.34 | <0.0001 |

| ICIq-OAB4b | 0.57 ± 0.37 | 8.08 ± 0.63 | 0.00011 |

| ICIq-OAB5a | 0 ± 0 | 3.33 ± 0.18 | <0.0001 |

| ICIq-OAB5b | 0 ± 0 | 7.92 ± 0.62 | <0.0001 |

| ICIq-OAB6a | 0 ± 0 | 1.96 ± 0.36 | 0.00021 |

| ICIq-OAB6b | 0 ± 0 | 7.00 ± 1.09 | <0.0001 |

| Ease of use | 0.14 ± 0.14 | 0.25 ± 0.18 | NS |

| Device understanding | 0.38 ± 0.20 | 0.42 ± 0.19 | NS |

BMI, body mass index; T Fluid, time of fluid consumption; F, female; M, male; NGB, neurogenic bladder; PVR, large post-void residual; Yrs, years; NS, not significant.

Ease of use Likert scale is 0–10 easy to difficult. Device understanding Likert scale is 0–10 good to poor.

Only recorded for n = 12/14.

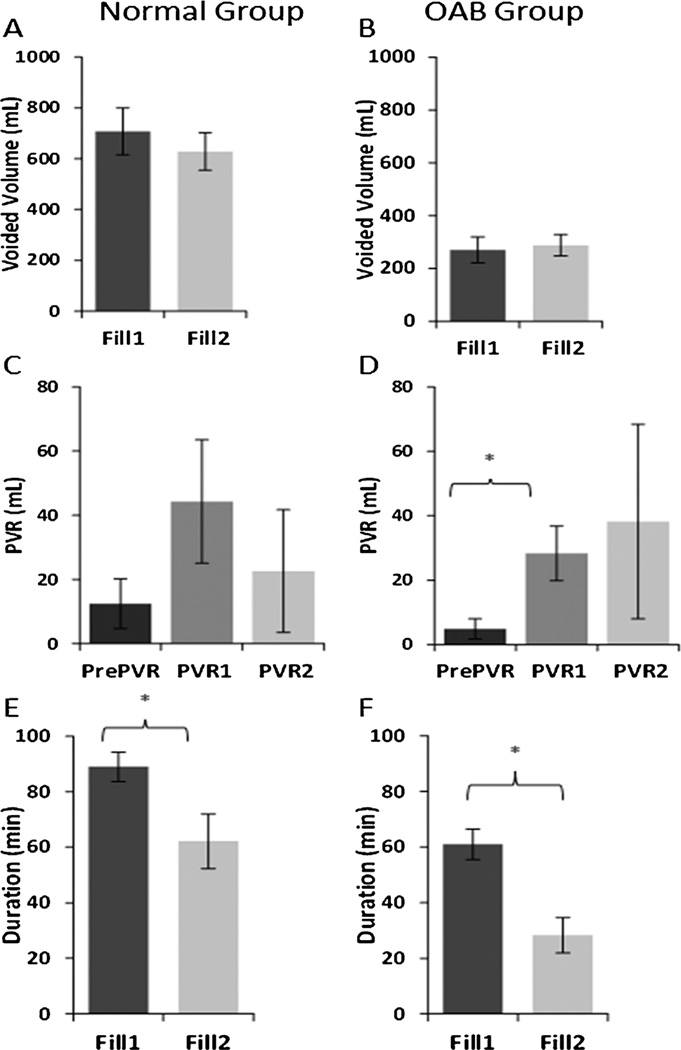

Voiding characteristics are shown in Fig. 2. There were no significant differences in voided volume or PVRs between fills in either group. The PVR performed directly before the start of the study (PrePVR) was lower than the PVRs after fill1 (PVR1) and fill2 (PVR2), but this was only statistically significant for PVR1 in the OAB group (P = 0.0036). Duration of filling was significantly higher in fill1 versus fill2 (P = 0.0012 for the normal; P < 0.001 for the OABs). There were no significant differences in voided volume or PVR between males versus females or between those who had the ultrasound images taken and those who did not (not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Comparisons between fill1 and fill2 for voided volume (A normals, mean ± standard error n = 14 and B OABs, n = 12), PVR (C normals and D OABs), and fill duration (E normals and F OABs). For the PVR comparison, values after fill1 (PVR1) and fill2 (PVR2) are compared to the pre-study PVR (PrePVR). FS, first sensation. PVR, post-void residual volume. *P < 0.05

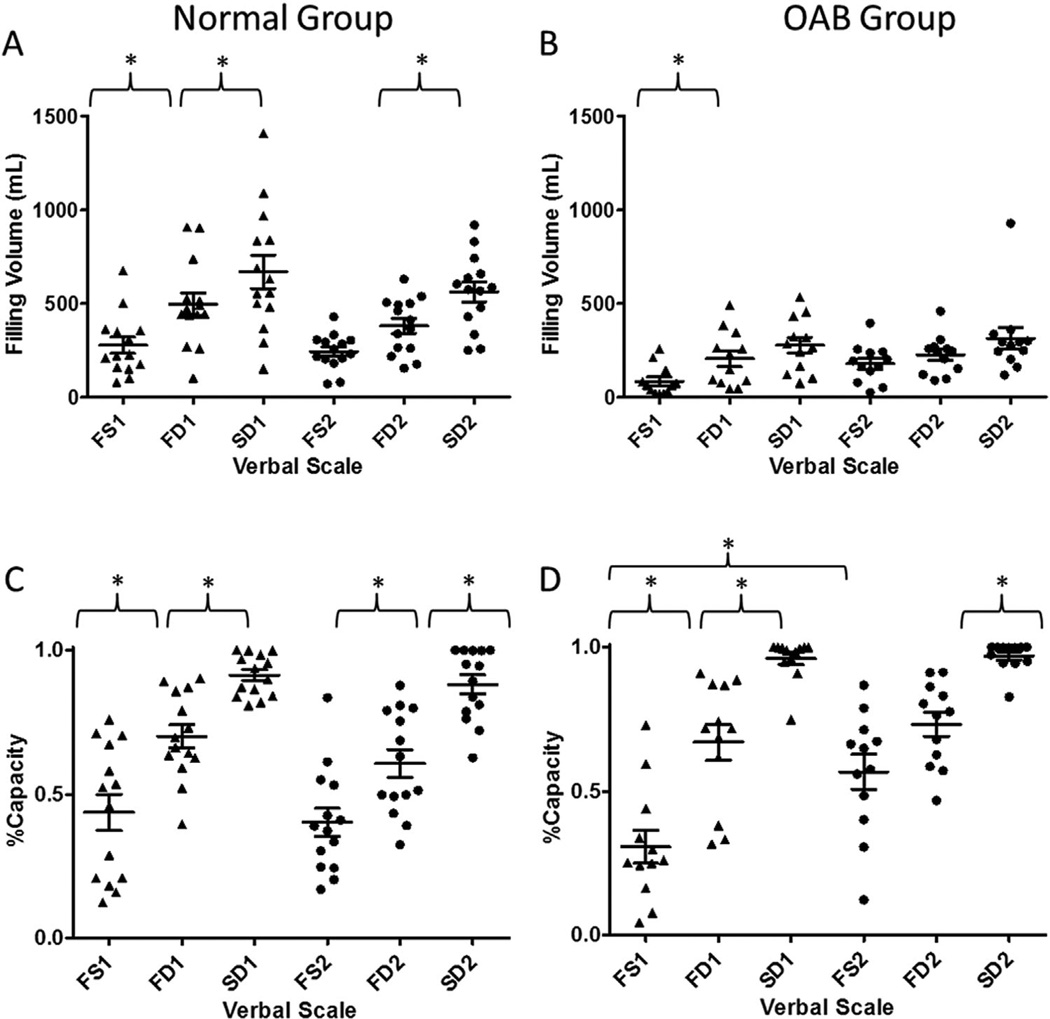

VSTs are shown in Fig. 3. Overall, higher bladder volumes (fill2 vs. fill1) were identified in OAB versus normal participants in 83% versus 43% (FS), 50% versus 29% (FD), and 67% versus 36% (SD), respectively. All VSTs occurred at significantly higher volumes in the normal group (Fig. 3A) compared to the OAB group (Fig. 3B) except for FS in fill2. In the normal group, all adjacent VSTs in fill1 (FS1 vs. FD1 vs. SD1) occurred at significantly different volumes (Fig. 3A, left), demonstrating that these could function effectively as unique volume markers. However, during fill2 (Fig. 3A, right), volumes of the first two thresholds (FS2 vs. FD2) were not different, suggesting that higher fill rates may make these VSTs overlap. When comparing identical thresholds between fill1 and fill2 (ie, FS1 vs. FS2), there were no differences in the normals, demonstrating that fill rate did not affect threshold volumes. In the OAB group, there was no statistical difference in adjacent VSTs in both fill1 and fill2 (with the exception of FS1 vs. FD1). This greater degree of adjacent threshold overlap in OAB as compared to normals suggests that these VSTs might not function effectively as unique volume markers in OAB, regardless of fill rate. Similar to the normal group, when comparing identical thresholds between fill1 and fill2, there were no differences in OAB.

FIGURE 3.

Verbal Sensory Thresholds (VSTs: FS, first sensation; FD, first desire; and SD, strong desire; verbal scale) were graphed against estimated filling volume (A normals, n = 14 and B OABs, n = 12) and %capacity (C normals and D OABs). Adjacent verbal sensory thresholds were compared within each fill, and identical thresholds were compared between fill1 (left columns) and fill2 (right columns). Each horizontal line represents the mean with corresponding error bars showing standard error. In each VST, symbols show individual data points. Significant differences at P < 0.05 level are shown within each plot with *. Significant differences between the two groups are not shown for visual clarity

To account for differences in filling volume, estimated % capacity was compared for the VSTs in both normals and OAB (Fig. 3C and D). Estimated %capacity in the normal group was significantly different between adjacent VSTs in both fill1 and fill2 (Fig. 3C), showing that these could function effectively as unique %capacity markers, regardless of fill rate. Likewise, using %capacity, all identical VSTs between fills (ie, FS1 vs. FS2) were similar. In the OAB group, there was some overlap in adjacent VSTs when compared to estimated %capacity in fill2 (see FS2 vs. FD2 in Fig. 3D), the effectiveness of these thresholds may be limited at higher fill rates. Likewise, some identical thresholds (see FS1 vs. FS2 in Fig. 3D) were significantly different in fill1 versus fill2 in OAB. In summary, the VSTs appropriately discriminated bladder %capacity in normal but not OAB participants.

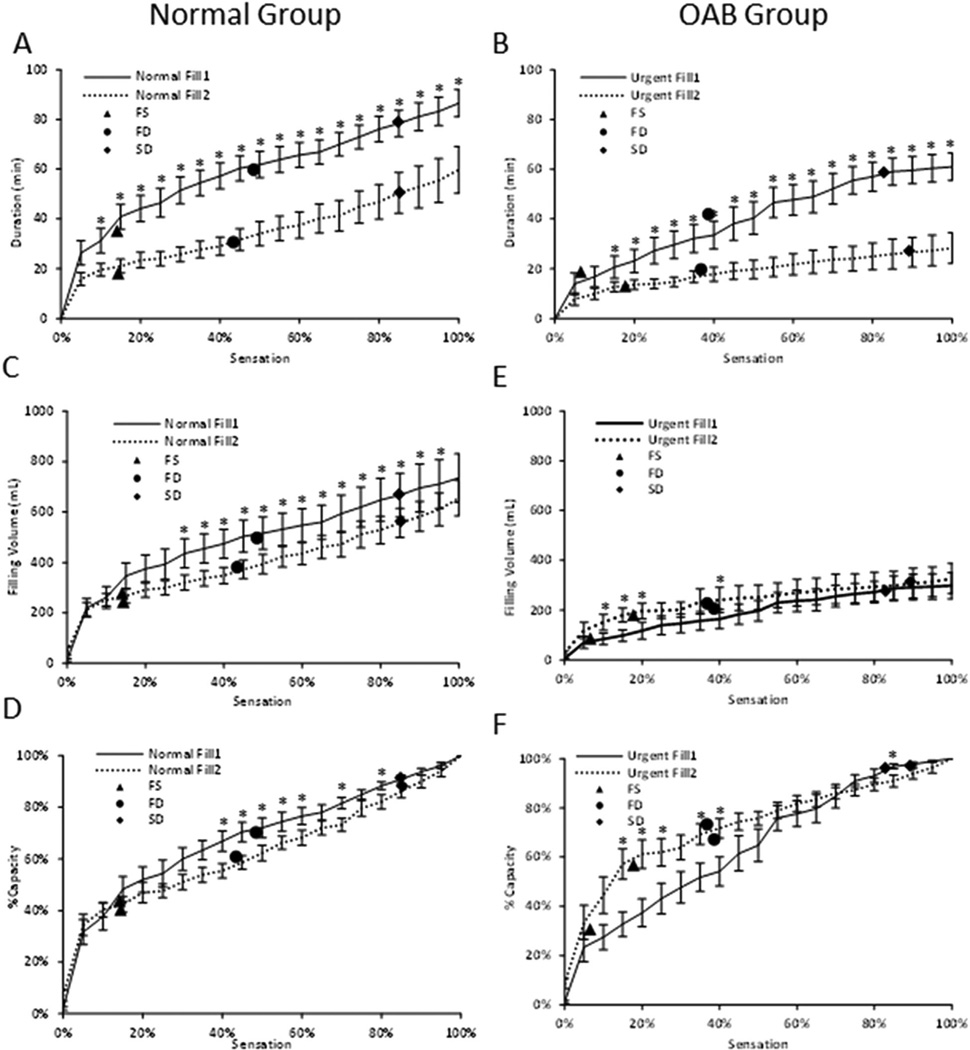

Real-time sensation curves (Fig. 4) provided a more comprehensive method to evaluate bladder filling than episodic VSTs (symbols in Fig. 4). There was a decrease in filling duration (Fig. 4A) and estimated volume (Fig. 4C) in fill2 versus fill1 in the normal group that was significant starting at 10% sensation for the duration curve and at 30% sensation for the volume curve. In the OAB group a similar trend was observed for duration (Fig. 4B), with significantly lower durations in fill2 starting at 15% sensation, but an opposite trend was observed for volume (Fig. 4E), with higher volumes in fill2 from 10% to 20% and at 40% sensation. The normal group had significantly higher %capacities (Fig. 4D) from fill1 compared to fill2 at sensations of 40–90% and the OAB group had significantly lower %capacities (Fig. 4F) at sensations of 15–40% and higher at 90% sensation.

FIGURE 4.

Comparisons of real-time sensation with Duration (A normal, mean ± standard error n = 14 and B OABs, n = 12), Filling Volume (C normals and E OABs), and %Capacity (D normals and F OABs). Comparisons between fill1 and fill2 were performed at 5% real-time sensation increments. Symbols for mean Verbal Sensory Thresholds (FS, first sensation; FD, first desire; and SD, strong desire, verbal scale) are included. *P < 0.05

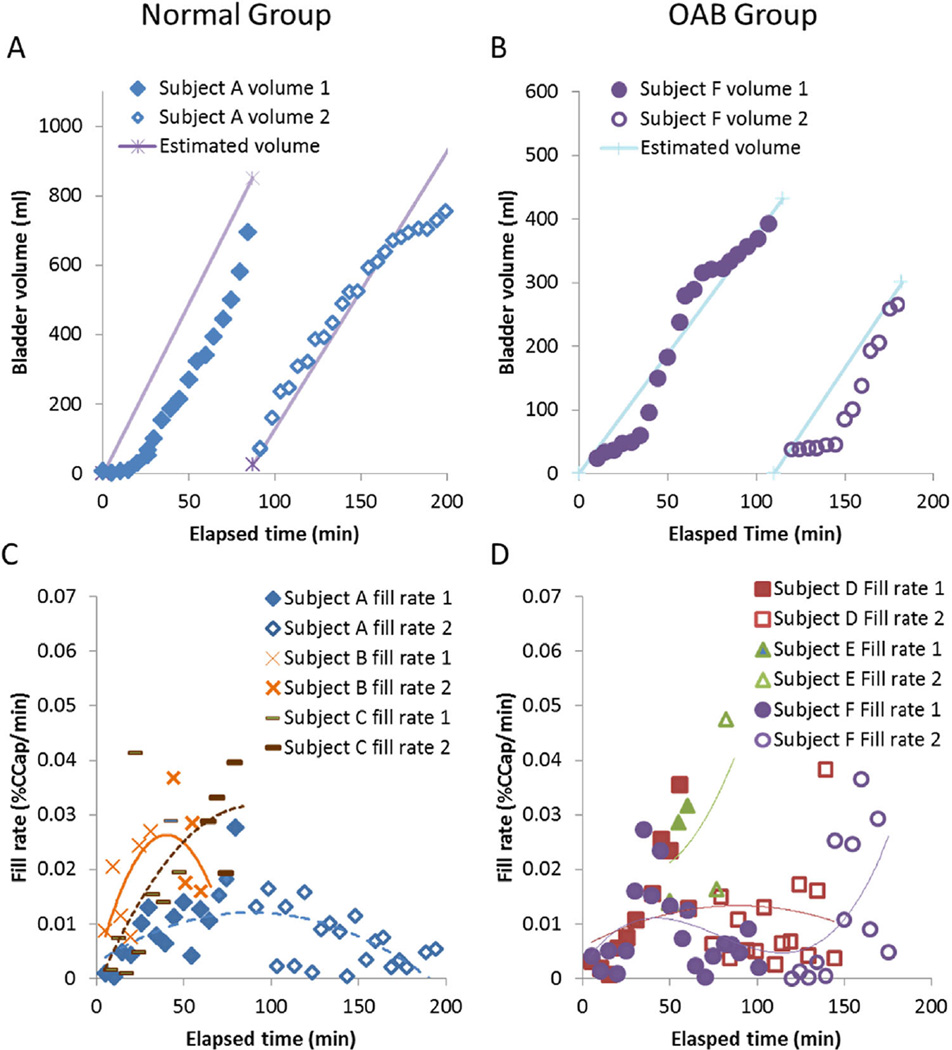

Representative volume versus time curves are shown in Fig. 5A (normal) and B (OAB), with the bladder volume measured from 3D ultrasound images plotted next to the volume estimated from the voided volume assuming linear filling. In the normal example, estimated volume overestimated the image volumes in fill1, especially early in the fill. In fill2, the estimated volume matched the image volume until near the end of the study. The concave-up shape seen in the first fill of this individual was also seen in the other two normal volunteers and one of the OAB volunteers. In the OAB example, volumes were again over estimated early in the fills. The slope of the volume versus time was not as constant, because this individual requested a third bottle of Gatorade during fill2 at time = 140 min. The sigmoidal shape seen in the first fill of this individual was also seen in one of the other OAB volunteers. Figure 5C (normal) and D (OAB) show the transient fill rates for the three subjects in each group, with polynomial curves fitted to each. Due to high abdominal obesity in Subject E (green triangles in D), bladder volumes early in each filling could not be reliably measured. The order of each polynomial was equal to the number of liters of Gatorade consumed. In three subjects (A, B, and D), the filling rate peaked around the time the subject voided between the two fills, and in the other three (C, E, and F), the filling rate continued to increase until the end of the study.

FIGURE 5.

Bladder volumes (A normals and B OABs) and fill rates (C normals and D OABs, three subjects each) as measured by 3D ultrasound. In the normal group (C), fill rates started slowly, ramped up, and in two cases ramped back down (blue diamonds and orange Xs), but in one case only levelled off by the end of fill2 (brown dashes). In the OAB group (D), fill rates started slowly and ramped up, in one case ramped down (red squares), in another case increased throughout the study (green triangles), and in the third, the subject requested more to drink, causing a second increase in fill rate (purple circles)

4 | DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated the feasibility of non-invasive, real-time characterization of bladder sensation through the use of a sensation meter and an accelerated hydration protocol in volunteers with and without OAB. Unlike UD testing that typically uses a constant rate for each fill, non-catheterized physiologic bladder fill rates can vary widely,7 and it is unclear how UD results translate to more typical bladder filling. The two-fill accelerated hydration protocol used in this study was designed to answer this question by providing fills at different rates and identified decreased duration in the second fill. The ultrasound images show that the fill rates vary significantly between the two fills and between individuals.

Investigator prompting to obtain VSTs is routinely performed during UD testing, but may bias the results.8 Previous work by De Wachter et al. on healthy volunteers initially demonstrated that graded degrees of the desire to void during filling (similar to VSTs) correlated with bladder volume.9 However, other studies by Erdem et al. demonstrated that VSTs can be achieved even in the absence of bladder filling and may be dramatically influenced by investigator prompting.10 In their study, the investigators reported that even in the absence of a urethral catheter, nearly half of the participants reported feeling a FS, and one quarter reported an FD. These authors concluded that new descriptions about bladder sensations during cystometry should be developed.

Although prior studies have attempted to measure real-time sensation to characterize voiding dysfunction, this type of study has never been performed outside of the UD laboratory with ultrasound to monitor bladder volume and fill rate. Oliver et al. described a patient-activated keypad device used to measure bladder sensations during urodynamics according to a 0–4 “urge score.”11 A later study by Lowenstein et al. described a device with a moveable lever that inputs directly into a UD unit and is used by subjects to record real-time sensations.12 However, unlike the prospective nature of the current study, the data was obtained retrospectively and, as the authors stated, UD “testing conditions may affect sensation and limit the conclusions that can be drawn.” Heeringa et al.5,6 had participants with and without OAB graph intensity of filling sensation every 10 min using a water loading protocol to ensure a repeatable fill rate and found different patterns and participant descriptions of their perceptions of bladder sensation.

Previous work in the evaluation of bladder sensation has focused on afferent nerve activity which is difficult to measure in an objective and non-invasive manner. Studies have focused on the identification of differential activation of C-fiber afferents using the ice water test which has been shown to be a lower motor neuron segmental reflex involving cold receptors.13,14 Other studies have demonstrated electrical perception threshold testing in which catheter mounted electrodes are used to stimulate the bladder and patient reported sensory thresholds are then recorded.15,16 More recently, functional MRI has been used to identify specific brain regions that are activated during UD testing.17–20

Results from this study show that use of VSTs has limited value in comparison to collection of continuous real-time sensation data using the sensation meter, especially for the OAB group. We demonstrated that estimated filling volumes for adjacent VSTs (within a fill) do not always differ depending on fill sequence (ie, FS overlaps with FD). The VSTs worked well to measure %capacity in the normal group with significantly different adjacent within-fill VSTs and identical between-fill same VST, but this was not true for the OAB group. Significant differences in identical VSTs between fills were found in the OAB group (ie, FS in fill1 differs from FS in fill2), which was also found by Gupta et al. in healthy female volunteers using urodynamics.21 More individuals in the normal group had higher bladder volumes in the second fill than the first at each VST, but there was a great deal of individual variation.

A benefit of using continuous real-time sensation is that volume and %capacity versus sensation curves can be constructed. Inverting the volume–%sensation curves, the resulting %sensation–volume curve would be concave up, the shape most commonly seen by De Wachter et al. using a water loading protocol.22 In the normal group, the curve shifted to the left between fill1 and fill2, which was consistent with viscoelastic behavior in that the faster filling in fill2 would cause greater wall tension for a given volume, triggering tension-sensitive afferent nerves responsible for sensation.23 However, in the OAB group, the opposite trend was observed. Further research is necessary to understand the biomechanical and sensitization changes responsible for this pattern. Increases in fill rate changed the firing patterns of mechanoreceptor nerves in rats, and in about half of the cases, increased afferent firing activity occurred at high bladder pressures.24 If similar patterns are true in humans, a faster fill rate may desensitize the bladder's mechanoreceptor nerves in some people to allow a rightward shift of the volume–sensation curve.24 Of the OAB participants, 83% showed a right shift while only 17% showed a left shift (similar to the normal group). The pattern of the curve (ie, left vs. right shift) may potentially indicate different causative mechanisms of OAB. Thus, this method may be a useful indicator for subcategorizing these patients either for treatment or for further testing with standard UD or repeat-fill UD.25

The fill rate measured by ultrasound was not linear as was assumed in the estimation of volume throughout filling. The initial part of the fill1 %sensation curve likely over-estimates volumes and %capacities as participants (especially those with OAB) may have started the study with a negative fluid balance. Limitations of the current study include small sample size and lack of catheterization to definitively measure filling and residual volumes. Gatorade G2 is an acidic drink (pH ~ 3), which may increase urine acidity which has been shown to increase bladder sensitivity.26 However, these limitations do not detract from the study purpose to develop a method to measure real-time bladder sensation in a non-invasive fashion. This method could be adapted to measure other filling symptoms such as pain and suddenness of urgency.

5 | CONCLUSIONS

This investigation demonstrates the feasibility of a non-invasive method to characterize real-time bladder sensation utilizing a two-fill accelerated hydration protocol and a novel sensation meter. Generation of sensation–%capacity curves may provide a method to help characterize different sensory patterns (sub-types) of OAB.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank ultrasound technologist Jary Varghese, biomedical engineering student Rachel Bernardo, registered nurse Sandra Smith, and statistician Luke Wolfe for their technical contributions to this study. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK101719) and from the Virginia Commonwealth University Presidential Research Quest Fund.

Le reports grants from National Institutes of Health, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Klausner reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Barbee reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Speich reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Nagle reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study;

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Colhoun has nothing to disclose; Dr. Ratz has nothing to disclose; Dr. Ghamarian has nothing to disclose; Dr. De Wachter has nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Agatep B, Milsom I, Abrams P. Worldwide prevalence estimates of lower urinary tract symptoms, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence and bladder outlet obstruction. BJU Int. 2011;108:1132–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Vats V, Thompson C, Kopp ZS, Milsom I. National community prevalence of overactive bladder in the united states stratified by sex and age. Urology. 2011;77:1081–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the international continence society. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:116–126. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.125704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams P, Avery K, Gardener N, Donovan J, Board IA. The international consultation on incontinence modular questionnaire: www.iciq.net. J Urol. 2006;175:1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00348-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heeringa R, de Wachter SG, van Kerrebroeck PE, van Koeveringe GA. Normal bladder sensations in healthy volunteers: a focus group investigation. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:1350–1355. doi: 10.1002/nau.21052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heeringa R, van Koeveringe G, Winkens B, van Kerrebroeck P, de Wachter S. Do patients with OAB experience bladder sensations in the same way as healthy volunteers? A focus group investigation. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:521–525. doi: 10.1002/nau.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson A, Griffiths C, Ramsden P, Neal D. Bladder function in healthy volunteers: ambulatory monitoring and conventional urodynamic studies. Br J Urol. 1994;73:242–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1994.tb07512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray M. Traces: making sense of urodynamics testing-part 8: evaluating sensations of bladder filling. Urologic Nurs. 2011;31:369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Wachter S, Heeringa R, Van Koeveringe G, Gillespie J. On the nature of bladder sensation: the concept of sensory modulation. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:1220–1226. doi: 10.1002/nau.21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erdem E, Tunçkiran A, Acar D, Kanik EA, Akbay E, Ulusoy E. Is catheter cause of subjectivity in sensations perceived during filling cystometry? Urology. 2005;66:1000–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliver S, Fowler C, Mundy A, Craggs M. Measuring the sensations of urge and bladder filling during cystometry in urge incontinence and the effects of neuromodulation. Neurourol Urodyn. 2003;22:7–16. doi: 10.1002/nau.10082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowenstein L, FitzGerald MP, Kenton K, et al. Validation of a real-time urodynamic measure of urinary sensation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:661.e1–661.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chai TC, Gray ML, Steers WD. The incidence of a positive ice water test in bladder outlet obstructed patients: evidence for bladder neural plasticity. J Urol. 1998;160:34–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Meel TD, de Wachter S, Wyndaele J. Repeated ice water tests and electrical perception threshold determination to detect a neurologic cause of detrusor overactivity. Urology. 2007;70:772–776. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Laet K, De Wachter S, Wyndaele J. Current perception thresholds in the lower urinary tract: sine-and square-wave currents studied in young healthy volunteers. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:261–266. doi: 10.1002/nau.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ukimura O, Ushijima S, Honjo H, et al. Neuroselective current perception threshold evaluation of bladder mucosal sensory function. Eur Urol. 2004;45:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krhut J, Tintera J, Holý P, Zachoval R, Zvara P. A preliminary report on the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging with simultaneous urodynamics to record brain activity during micturition. J Urol. 2012;188:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shy M, Fung S, Boone TB, Karmonik C, Fletcher SG, Khavari R. Functional magnetic resonance imaging during urodynamic testing identifies brain structures initiating micturition. J Urol. 2014;192:1149–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.04.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarrahi B, Mantini D, Balsters JH, et al. Differential functional brain network connectivity during visceral interoception as revealed by independent component analysis of fMRI time-series. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4438–4468. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao Y, Liao L, Blok BF. A resting-state functional MRI study on central control of storage: brain response provoked by strong desire to void. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47:927–935. doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-0978-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta A, Defreitas G, Lemack GE. The reproducibility of urodynamic findings in healthy female volunteers: results of repeated studies in the same setting and after short-term follow-up. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:311–316. doi: 10.1002/nau.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Wachter SG, Heeringa R, Van Koeveringe GA, Winkens B, Van Kerrebroeck PE, Gillespie JI. “Focused introspection” during naturally increased diuresis: description and repeatability of a method to study bladder sensation non-invasively. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33:502–506. doi: 10.1002/nau.22440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanai A, Andersson K. Bladder afferent signaling: recent findings. J Urol. 2010;183:1288–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Wachter S, De Laet K, Wyndaele J. Does the cystometric filling rate affect the afferent bladder response pattern? A study on single fibre pelvic nerve afferents in the rat urinary bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2006;25:162–167. doi: 10.1002/nau.20157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colhoun AF, Klausner AP, Nagle AS, et al. A pilot study to measure dynamic elasticity of the bladder during urodynamics. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016 doi: 10.1002/nau.23043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison J. The activation of bladder wall afferent nerves. Exp Physiol. 1999;8:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445x.1999.tb00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]