Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to assess whether the intrafollicular cytokine profile in naturally developed follicles is different in women with endometriosis, possibly explaining the lower reproductive outcome in endometriosis patients.

Methods

A matched case-control study was conducted at a university-based infertility and endometriosis centre. The study population included 17 patients with laparoscopically and histologically confirmed endometriosis (rAFS stages II–IV), each undergoing one natural cycle IVF (NC-IVF) treatment cycle between 2013 and 2015, and 17 age-matched NC-IVF women without diagnosed endometriosis (control group). Follicular fluid and serum was collected at the time of follicle aspiration. The concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, IL-18, TNF-α) and hormones (testosterone, estradiol, AMH) were determined in follicular fluid and serum by single or multiplexed immunoassay and compared between both groups.

Results

In the follicular fluid, IL-1β and IL-6 showed significantly (P < 0.001 and 0.01, respectively) higher median concentrations in the endometriosis group than in the control group and a tendency towards endometriosis severity (rAFS stage) dependence. The levels of the interleukins detectable in follicular fluid were significantly higher than those in the serum (P < 0.01). Follicular estradiol concentration was lower in severe endometriosis patients than in the control group (P = 0.036). Follicular fluid IL-1β and IL-6 levels were not correlated with estradiol in the same compartment in neither patient group.

Conclusions

In women with moderate and severe endometrioses, some intrafollicular inflammatory cytokines are upregulated and not correlated with intrafollicular hormone concentrations. This might be due to the inflammatory microenvironment in endometriosis women, affecting follicular function and thereby possibly contributing to the reproductive dysfunction in endometriosis.

Keywords: Natural cycle IVF, Follicular fluid, Endometriosis, Interleukin, Estradiol

Introduction

Endometriosis, defined as the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside of the uterine cavity [1], is a common, chronic, progressive and inflammatory disease, associated with local and systemic abnormal immunity [2]. It is considered to be a complicated cause of female infertility and affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age [3], while 30–40% of women with endometriosis experience infertility [4].

Endometriosis is associated with inflammatory changes in the peritoneum, and which can be reflected in the serum. Several studies have found increased levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β [5], IL-6 [6, 7], IL-8 [8] and IL-18 [9] in the peritoneal fluid [5, 8, 9] and in the circulation [6, 7] in patients with endometriosis.

Furthermore, altered levels of inflammatory cytokines have been found in the follicular fluid of endometriosis patients undergoing conventional, gonadotropin-stimulated IVF (cIVF). Most but not all [6, 8, 10] studies revealed increased intrafollicular levels of cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 [6] and IL-8 [8]. In addition, previous reports have demonstrated that the hormonal milieu was altered in the follicular fluid of patients with endometriosis, such as a decreased estradiol concentration [2].

A dysregulated intrafollicular hormone milieu [11] as well as an abnormal intrafollicular cytokine profile might therefore be a cause of reduced fertility in endometriosis patients. This suggestion is in line with studies from oocyte donation programmes. Implantation rates were reduced with oocytes from women with endometriosis transferred to women without endometriosis, whereas embryos from healthy donors, transferred to women with endometriosis, did not affect implantation rates [12].

However, the findings mentioned above were mostly obtained from cIVF in which the exogenous gonadotropins considerably affect the intrafollicular hormonal milieu [11] and immune system [13].

Therefore, it seems logical to determine the function of the unstimulated follicle with and without endometriosis to better understand the physiological situation. Based on this knowledge, studies analysing the follicular milieu after high-dosage gonadotropin stimulation might be easier to interpret.

Natural cycle IVF (NC-IVF) seems to be an adequate model for a physiological follicle because the follicles undergo the maturation process without any stimulation apart from a single HCG administration to induce ovulation and therefore closely represent natural follicles [11]. Therefore, we have used the model of NC-IVF in a selected group of women with histologically proven endometriosis and carefully selected matched controls to analyse the concentrations of several inflammatory cytokines and hormones present in the follicular fluid and serum at the time of follicular aspiration. We aimed to better understand the impact of endometriosis on the physiology of the unstimulated follicles with the wider implication of improving the outcome of IVF treatment in endometriosis patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

The matched case-control study involved a total of 34 women performing an NC-IVF cycle between 2013 and 2015. To avoid a bias in the selection of the patients, the biologist (N.A.B.) independently selected the patients and the controls from a list of patients provided by the physician (M.v.W.). Furthermore, the technician performing the cytokine and hormone analysis was blinded to patient’s group. Seventeen of them were diagnosed with endometriosis by laparoscopy and histology. The operation was performed 0.25–3.0 (1.6 ± 0.9) years before follicle aspiration for IVF, and endometriosis was staged according to the “Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis”, rAFS [14], based on the point system as described in the reference. Some women were also diagnosed potential infertility causes such as male (n = 5), tubal (n = 4) and other infertility factors such as peritubal adhesions (n = 1). Another 17 women served as controls in which endometriosis was excluded by medical history (no dysmenorrhea, no dyspareunia), vaginal ultrasound (no endometrioma, no signs of uterine adenoma or adhesions) and clinical examination. Women in the control group were diagnosed with male (n = 8), tubal (n = 4), idiopathic (n = 4) or other infertility factors such as myoma (n = 2) (one woman had two different infertility factors, resulting in n = 18). Women included in the study neither suffered from any infectious diseases nor did they take medications apart from folic acid. Women had to be 18–42 years of age and the body mass index needed to be below 35 kg/m2. The controls were matched with the endometriosis cases for age, thus resulting in 17 pairs. The age of the controls was in the range of ±2 years of the endometriosis women (mean 0.3 ± 1.7 years). Basic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of cases with proven endometriosis and without diagnosed endometriosis

| Endometriosis (n = 17) | No endometriosis (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years)a | 35.4 (±4.3, 26–42) | 35.7 (±3.1, 29–41) |

| Aetiology of infertility (n/total) | ||

| Endometriosis, total (rAFS stages II–IV) | 17/17 | 0/17 |

| rAFS stage II | 7/17 | |

| rAFS stage III + IV | 10/17 | |

| Male factor | 5/17 | 8/17 |

| Tubal factor | 4/17 | 4/17 |

| Idiopathic | 0/17 | 4/17 |

| Others | 1/17 | 2/17 |

| Anti-Mullerian hormone (pmol/L)b | 13.8 (±14.3) | 16.1 (±12.7) |

aPatients were age matched for the purpose of this study

bAMH was determined in the serum before undergoing IVF treatment. Values do not differ between the two groups (Wilcoxon-paired test)

IVF procedure and sample collection

The patients were monitored by ultrasound and analysis of luteinizing hormone (LH) and serum 17β-estradiol (E2) concentrations. When the latter was above 800 pmol/L, 5000 IU of hCG (Pregnyl®; MSD Merck Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Lucerne, Switzerland) was administered. Transvaginal oocyte retrieval was performed 36 h later without anaesthesia as described elsewhere [15]. As the follicles were flushed to increase oocyte yield, only the first aspirate was used for analysis in this study (dead volume, which remained in the needle, 0.9 mL). Follicular fluid which appeared macroscopically clear without any blood contamination was clarified by centrifugation at 600×g for 10 min and at 1300×g for another 10 min successively to eliminate cells and cell debris, respectively. Then, the supernatant fluids were stored at −70 °C until further analysis. Besides the 34 (17 cases and 17 matched controls) follicular fluids (FFs), serum was available from the venous blood, collected at the time of follicle aspiration, of 10/17 endometriosis and of 7/17 control cycles. Serum was not available from all women as some of them did not provide consent to provide blood. Serum aliquots were stored at −70 °C.

Multiplexed cytokine determinations

The follicular fluids were assayed using a Bio-Plex® platform (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA). The custom-designed six-plex kit included reagents to detect human cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, IL-18 and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). We have chosen these cytokines as previous studies have shown dysregulation of these factors in endometriosis in serum [6], peritoneal [9] and follicular fluid of conventional, gonadotropin-stimulated IVF [6, 16–18], suggesting these factors to be associated with endometriosis. The Bio-Plex® assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and has previously been described [13]. As a consequence, follicular fluids were diluted 1:3 using the sample diluent provided with the kit. Briefly, capture beads (50 μL per well) were added to pre-wetted filter plates, and then standards and test samples were added to respective sample wells (50 μL per well) in duplicates. A mixture of biotinylated detection antibodies (25 μL per well) and labelled streptavidin (50 μL per well) was added as the first and the second detection steps successively. Following each of the aforementioned steps, the test samples were incubated at room temperature on a vibrating platform covered by a sealing tape.

The collected sera were assayed similarly using the 1:4 dilution as suggested by the manufacturer. The kit was designed to detect the four human interleukins: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-18; the cytokines IL-15 and TNF-α which turned out to be undetectable in a majority of samples in the previous run with FFs were excluded from the serum analysis.

Data acquisition was set to 50 beads per region and the bead map to 100 regions. The instrument DD gates were set to 5000 (low) and 25,000 (high). The plate was read at the high-sensitivity setting. Data analysis and transfer of raw data and standard curve calculations into Excel tables were performed using Bio-Plex Manager software, version 6.1.

Measurement of hormones

Total testosterone (T) and estradiol (E2) concentrations were determined by electro-chemiluminescent immunoassay (ECLIA) on a COBAS 6000 (e601 module) station (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) of these assays were less than 4%. Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) was determined manually with a commercially available microplate enzyme immunometric assay (ELISA) kit obtained from Cloud-Clone Corp. (Wuhan, China) and performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Inter-assay CV was below 12%.

Statistical analysis

The number of analysed samples in this study, i.e. 17 matched pairs (34 samples), was determined by the strict inclusion criteria applied. Since all the data showed skewed distributions, logarithmic transformation was performed and the data was transformed into an approximate normal distribution before statistical analyses. Statistical analyses were performed by a statistician blinded for the patient’s group using a linear regression mixed-effects model and an orthogonal contrast posttest for the comparison of follicular fluid or serum cytokine concentrations or intrafollicular hormone levels. The analysis was performed for all stages combined (rAFS II to IV) and for rAFS II and rAFS III + IV groups separately compared to controls. A P value below 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Two hundred sixty-nine women were screened, and 222 were identified as being eligible in fulfilling the inclusion criteria for the study group. Of these, 17 women were diagnosed to have endometriosis of rAFS stages II–IV and were included in the study.

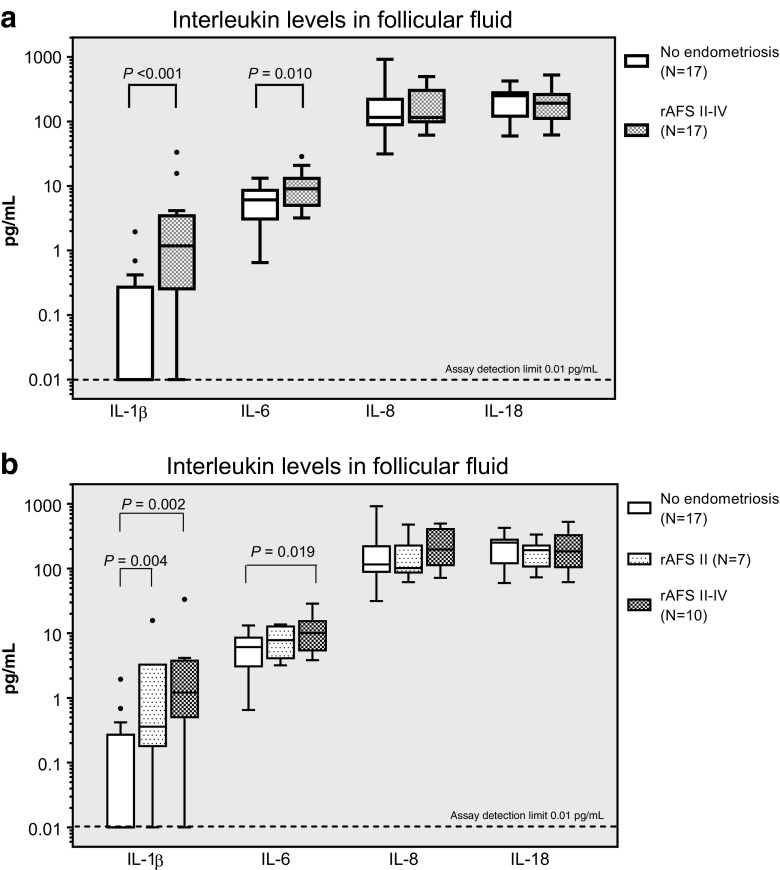

Cases with endometriosis and women without diagnosed endometriosis were not significantly different regarding basic characteristics (Table 1). In the follicular fluid, IL-1β and IL-6 showed significantly higher median concentrations in the endometriosis than in the control group (P < 0.001 and 0.010, respectively, N = 17, Fig. 1a). IL-8 and IL-18 were not significantly different. The power to detect a significant difference of cytokine concentrations was according to the mean and standard deviation of 76.4% (IL-1β), 80.3% (IL-6), 50.1% (IL-8) and 50.7% (IL-18) (α = 0.05, two-tailed).

Fig. 1.

Box plots of the follicular fluid concentrations for the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-18 as determined using the Bio-Plex method. a Endometriosis group (all stages combined) vs control group. b rAFS stage II (moderate endometriosis) plotted separately from the more severe rAFS stage III + IV. Boxes represent the 10th and 90th centiles. Data points outside this range are plotted as individual points. P values shown in the graph are significant (P < 0.05). Please note the logarithmic scale

Moreover, IL-1β and IL-6 showed a tendency towards a dependence on the severity of the disease (rAFS stage II, Fig. 1b) while no such trend was observed for the FF concentrations of IL-8 and IL-18. IL-15 and TNF-α could not be detected in the follicular fluid.

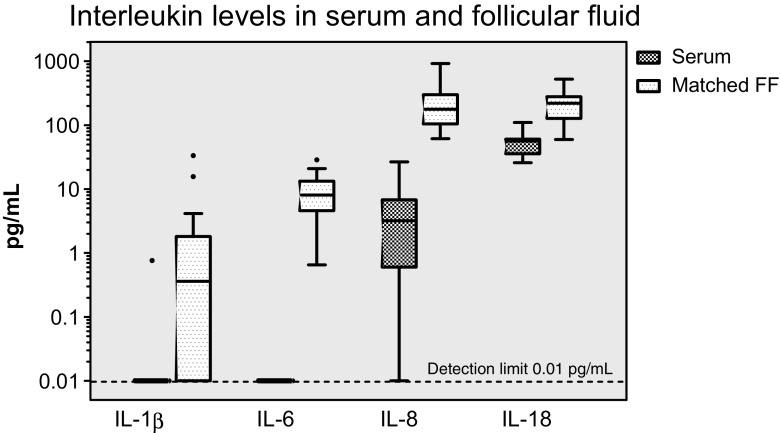

The four cytokines which were measurable in follicular fluid were also investigated in the serum. IL-1β and IL-6 could not be detected in the matching serum samples collected on the day of oocyte recovery (and follicular fluid collection), except for one result for IL-1β. The concentrations of all four interleukins were significantly higher (P < 0.01) in the follicular fluid than in the serum over the entire study population (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Box plots of the above cytokines as a comparison between matched serum and follicular fluid samples, with the case and control groups combined (controls: N = 7; rAFS stage II: N = 4; rAFS stage III/IV: N = 6). IL-1β and IL-6 could not be detected in the serum (P < 0.01 pg/mL) with the exception of one result for IL-1β. The differences are highly significant for all markers (P < 0.01). For other details, see the legend in Fig. 1. Please note the logarithmic scale

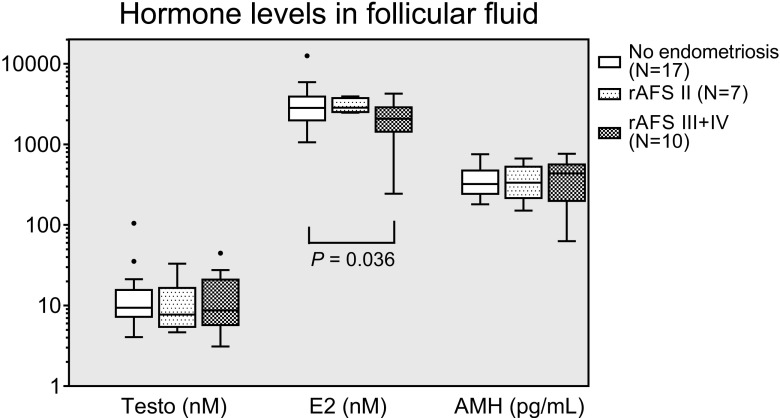

Regarding the hormones in follicular fluid, E2 concentrations were lower in severe than in mild cases of endometriosis (without statistical significance) and in control women (P = 0.036) (Fig. 3). The median follicular AMH concentration was slightly increased with severe endometriosis (without reaching statistical significance), while testosterone did not differ between groups (Fig. 3). In the follicular fluid, hormone and cytokine concentrations did not correlate with the different endometriosis stages.

Fig. 3.

Box plots of the follicular fluid concentrations for the hormones testosterone (Testo), estradiol (E 2) and anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) in endometriosis (rAFS stages II and III + IV) and control IVF patients. No statistically significant differences were observed between the subgroups except one significance between the disease severities for E2 (see graph). For other details, see the legend in Fig. 1. Please note the logarithmic scale

Discussion

Our study revealed an increase of some inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 in naturally matured follicles in women with proven endometriosis (rAFS stages II–IV) compared to controls without diagnosed endometriosis.

Some previous studies had already described altered levels of inflammatory cytokines in the follicular fluid of endometriosis patients, but all these had been performed in women undergoing conventional, gonadotropin-stimulated IVF (cIVF). As the follicular function is strongly affected by high-dosage gonadotropin stimulation [11], we aimed to analyse the effect of endometriosis on naturally matured follicles in natural cycle IVF (NC-IVF).

We have chosen a panel of cytokines which have been shown in previous studies to be increased in the follicular fluid of gonadotropin-stimulated endometriosis patients, such as IL-1β [16, 19] and IL-6 [6, 20], or which are known to play a role in endometriosis such as IL-8 [21, 22] and IL-18 [9].

Pellicer et al. [6] had found non-significantly increased concentrations of IL-1β and significantly increased concentrations of IL-6 in the serum and in the follicular fluid of 12 women with severe endometriosis undergoing cIVF. Our findings obtained here with 17 NC-IVF women with moderate and severe endometrioses confirm these results.

The similar results in stimulated as well as in unstimulated follicles clearly indicate an alteration of the cytokine milieu in women with moderate and severe endometrioses. As cytokines are involved in the regulation of follicles and as the follicular fluid contains cytokine-producing immune cells [23], increased intrafollicular inflammatory cytokine concentrations might have an effect on follicular physiology, resulting in lower oocyte quality and thereby in reduced outcome of IVF therapies. This suggestion is clinically supported by Altun et al. [24]. They have reported an increased likelihood for clinical pregnancies in patients with low intrafollicular IL-6 cytokine concentrations in women without endometriosis.

However, such a negative effect of high cytokine concentrations has not been described for IL-1β. Zollner et al. [25] even found increased fertilisation rates, and Asimakopoulos et al. [26] found increased pregnancy rates in women with increased intrafollicular concentrations of IL-1β.

We have also analysed the intrafollicular concentration of IL-8 and IL-18 as these cytokines are strongly associated with endometriosis [9, 21, 22, 27]. These factors also seem to play a role in reproduction as previous studies [28, 29] noted a correlation of IL-8 with follicular size and therefore suggested IL-8 as an intrafollicular marker of follicular maturity. Follicular fluid IL-18 at the time of oocyte retrieval was positively correlated with the number of oocytes and the chance for successful pregnancy [30, 31]. In contrast to IL-1β and IL-6, our study did not reveal any differences in the concentration of IL-8 and IL-18 as a function of the presence of endometriosis. Therefore, this disease seems to be associated with a selective but not with a general increase of pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations in follicular fluid.

Hypothetically, cytokines might diffuse from the blood circulation into the follicles. Such an event would lead to increased concentrations of cytokines such as IL-8 and IL-18 which are highly concentrated in peritoneal fluid in endometriosis. A significant influx of cytokines from the circulation, however, seems unlikely as we have demonstrated cytokine concentrations to be much higher in the follicles than in the serum.

Therefore, it can be assumed that increased amounts of intrafollicular cytokines are produced by the granulosa cells or the intrafollicular immune cells. Follicular fluid contains a broad spectrum of immune cells such as leucocytes and lymphocytes [23] which might be, similar to the situation in peritoneal fluid, increasingly produced or activated in endometriosis. However, as neither the concentration nor the activity of intrafollicular immune cells has yet been analysed in endometriosis patients, this assumption remains hypothetical.

Endometriosis seems to have a distinct but still poorly understood effect on the cytokine spectrum of the follicles, resulting in increased concentrations of IL-1β and IL-6 but not of IL-8 and IL-18. Furthermore, it is still not clear whether the increased cytokine concentrations would have a detrimental effect on follicular physiology. Increased cytokine concentrations in endometriosis suggest such a hypothetical detrimental effect. However, as shown above, increased IL-1β concentrations have also been reported to be beneficial as high IL-1β correlated with higher fertilisation and pregnancy rates [25, 26]. This raises the question whether the maturing follicles require a balanced cytokine profile. A moderate increase of intrafollicular IL-1β might be beneficial, whereas a marked increase might be deleterious.

Following the detection of significantly increased intrafollicular concentrations of IL-1β and IL-6, we have performed an analysis of intrafollicular hormone concentrations in order to study a potential impact of increased cytokine concentrations on the intrafollicular endocrine milieu. We had previously characterised the intrafollicular milieu in naturally matured follicles [11]. Based on these findings and the study from Wunder et al., who found decreased follicular fluid estradiol concentrations in endometriosis patients undergoing cIVF [16], and studies suggesting AMH to be a marker of oocyte quality [32, 33, 34], we chose testosterone, E2 and AMH to characterise the endocrine milieu.

In the endometriosis group, we have found decreased E2 concentrations in follicular fluid. Therefore, we have looked at the correlations of cytokine concentrations with E2 levels to support or reject the existence of such a link. As we were unable to demonstrate such a correlation and as testosterone and AMH concentrations were not altered in women with endometriosis, we assume that the follicular hormone milieu would not be relevantly affected by the presence of endometriosis. This conclusion is partly in line with Pellicer et al. [6]. They have analysed several steroid hormones in the follicular fluid obtained from 24 cIVF cycles. They have found an increase of intrafollicular progesterone, decreased testosterone and unaffected E2. However, as the steroid hormones were not uniformly affected and as they were not able to identify a steroid hormone which correlated with the quality of embryos, a significant and clinically relevant effect of endometriosis on the intrafollicular endocrine milieu seems to be unlikely.

Can therapeutic consequences be drawn from these findings? It has been proven by several studies that surgical therapy of endometriosis and ultralong downregulation before IVF therapy resulted in higher pregnancy rates [35]. Therefore, the concept that the follicular physiology could be improved by reducing the activity of endometriosis and possibly also resulting in reduced intrafollicular cytokine concentrations seems to be intriguing. However, such a concept requires further studies confirming that surgical or medical endometriosis therapy would lead to a reduction of intrafollicular cytokine concentrations.

Furthermore, it needs to be stressed that the study has several limitations. Firstly, it is based on the assumption that women in our study group, who were previously diagnosed with endometriosis, still had endometriosis when the follicle aspiration was performed. Secondly, we assumed that women in our control group without any symptoms and direct or indirect clinical signs of endometriosis did not have a moderate or severe stage (rAFS stages II–IV) of endometriosis. We did not prove that women of the control group were free of endometriosis as laparoscopy without any signs of endometriosis is not indicated and, therefore, ethically not acceptable. However, as women without any sign and symptoms might still have minimal endometriosis (rAFS stage I), we only included women with endometriosis rAFS stages II–IV into our study group to reduce this potential error. The value of the rAFS classification has been controversially discussed. Although it has been suggested to be of low prognostic value for obtaining spontaneous pregnancies [36], it was shown to correlate well with the success of IVF treatments [37], qualifying this classification for this study.

In summary, the cytokine milieu is affected not only in gonadotropin stimulated, as has been shown previously, but also in naturally matured follicles in women with proven endometriosis. However, this increase does not appear to have a substantial impact on the follicular endocrine milieu. It remains open whether increased intrafollicular cytokines have an impact on follicular physiology and thereby on the quality of oocytes in women with endometriosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Anne Vaucher for her support in performing the immunoassays.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study was approved by the local ethical committee and informed written consent was obtained from all patients.

Funding

This work was financed by grant-in-aid for scientific research from the National Natural Science Foundation for the Youth of China (No. 81601240) and was supported by an unrestricted grant from the IBSA Institut Biochimique SA, Lugano, Switzerland.

Conflict of interest

The study was supported by an unrestricted research grant from the IBSA Institut Biochimique SA. The authors are clinically involved in the low-dose monofollicular stimulation and IVF therapies, using gonadotropins from all gonadotropin distributors on the Swiss market, including the IBSA Institut Biochimique SA.

References

- 1.Sampson JA. Metastatic or embolic endometriosis, due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the venous circulation. Am J Pathol. 1927;3:93–110.43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wunder DM, Mueller MD, Birkhäuser MH, Bersinger NA. Steroids and protein markers in the follicular fluid as indicators of oocyte quality in patients with and without endometriosis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2005;22:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s10815-005-5149-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giudice LC. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2389–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1000274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Endometriosis and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sikora J, Mielczarek-Palacz A, Kondera-Anasz Z. Association of the precursor of interleukin-1β and peritoneal inflammation-role in pathogenesis of endometriosis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Pellicer A, Albert C, Mercader A, Bonilla-Musoles F, Remohí J, Simón C. The follicular and endocrine environment in women with endometriosis: local and systemic cytokine production. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:425–431. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashanian M, Sariri E, Vahdat M, Ahmari M, Moradi Y, Sheikhansari N. A comparison between serum levels of interleukin-6 and CA125 in patients with endometriosis and normal women. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29:280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malhotra N, Karmakar D, Tripathi V, Luthra K, Kumar S. Correlation of angiogenic cytokines-leptin and IL-8 in stage, type and presentation of endometriosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28:224–227. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2011.593664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arici A, Matalliotakis I, Goumenou A, Koumantakis G, Vassiliadis S, Mahutte NG. Altered expression of interleukin-18 in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:889–894. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)01122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammadeh ME, Ertan AK, Zeppezauer M, Baltes S, Georg T, Rosenbaum P, et al. Immunoglobulins and cytokines level in follicular fluid in relation to etiology of infertility and their relevance to IVF outcome. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2002;47:82–90. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2002.1o024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Wolff M, Kollmann Z, Flück CE, Stute P, Marti U, Weiss B, et al. Gonadotrophin stimulation for in vitro fertilization significantly alters the hormone milieu in follicular fluid: a comparative study between natural cycle IVF and conventional IVF. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:1049–1057. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hauzman EE, Garcia-Velasco JA, Pellicer A. Oocyte donation and endometriosis: what are the lessons? Semin Reprod Med. 2013;31:173–177. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bersinger NA, Kollmann Z, Von Wolff M. Serum but not follicular fluid cytokine levels are increased in stimulated versus natural cycle IVF: a multiplexed assay study. J Reprod Immunol. 2014;106:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:817–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.von Wolff M, Schneider S, Kollmann Z, Weiss B, Bersinger NA. Exogenous gonadotropins do not increase the blood-follicular transportation capacity of extra-ovarian hormones such as prolactin and cortisol. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:87. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wunder DM, Mueller MD, Birkhäuser MH, Bersinger NA. Increased ENA-78 in the follicular fluid of patients with endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:336–342. doi: 10.1080/00016340500501715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falconer H, Sundqvist J, Gemzell-Danielsson K, von Schoultz B, D’Hooghe TM, Fried G. IVF outcome in women with endometriosis in relation to tumour necrosis factor and anti-Müllerian hormone. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;18:582–588. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi YS, Cho S, Seo SK, Park JH, Kim SH, Lee BS. Alteration in the intrafollicular thiol-redox system in infertile women with endometriosis. Reproduction. 2015;149:155–162. doi: 10.1530/REP-14-0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert S, Santulli P, Chouzenoux S, Marcellin L, Borghese B, de Ziegler D, et al. Endometriosis: increasing concentrations of serum interleukin-1β and interleukin-1sRII is associated with the deep form of this pathology. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2014;43:735–743. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z, de Matos DG, Fan HY, Shimada M, Palmer S, Richards JS. Interleukin-6: an autocrine regulator of the mouse cumulus cell-oocyte complex expansion process. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3360–3368. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borrelli GM, Abrão MS, Mechsner S. Can chemokines be used as biomarkers for endometriosis? A systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:253–266. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Velasco JA, Arici A. Chemokines and human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:983–993. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(99)00120-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider S, Kollmann Z, Bersinger NA, Mueller MD, Dahinden C, von Wolff M. Charakterisierung der immunzellpopulation in Follikelflüssigkeitsaspiraten: Ein Vergleich zwischen natural cycle IVF und konventioneller IVF. J Reproduktionsmed Endokrinol. 2013;10:310–311. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altun T, Jindal S, Greenseid K, Shu J, Pal L. Low follicular fluid IL-6 levels in IVF patients are associated with increased likelihood of clinical pregnancy. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28:245–251. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9502-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zollner KP, Hofmann T, Zollner U. Good fertilization results associated with high IL-1beta concentrations in follicular fluid of IVF patients. J Reprod Med. 2013;58:485–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asimakopoulos B, Demirel C, Felberbaum R, Waczek S, Nikolettos N, Köster F, et al. Concentrations of inflammatory cytokines and the outcome in ICSI cycles. In Vivo. 2010;24:495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bersinger NA, Dechaud H, McKinnon B, Mueller MD. Analysis of cytokines in the peritoneal fluid of endometriosis patients as a function of the menstrual cycle stage using the Bio-Plex® platform. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2012;118:210–218. doi: 10.3109/13813455.2012.687003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malizia BA, Wook YS, Penzias AS, Usheva A. The human ovarian follicular fluid level of interleukin-8 is associated with follicular size and patient age. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:537–543. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Runesson E, Bostrom EK, Janson PO, Brannstrom M. The human preovulatory follicle is a source of the chemotactic cytokine interleukin-8. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2:245–250. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.4.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutman G, Soussan-Gutman L, Malcov M, Lessing JB, Amit A, Azem F. Interleukin-18 is high in the serum of IVF pregnancies with ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;51:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarapik A, Velthut A, Haller-Kikkatalo K, Faure GC, Béné MC, de Carvalho Bittencourt M, et al. Follicular proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines as markers of IVF success. Clin Develop Immunol. 2012;2012:606459. doi: 10.1155/2012/606459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fanchin R, Mendez Lozano DH, Frydman N, Gougeon A, di Clemente N, Frydman R, et al. Anti-Müllerian hormone concentrations in the follicular fluid of the preovulatory follicle are predictive of the implantation potential of the ensuing embryo obtained by in vitro fertilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1796–1802. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takahashi C, Fujito A, Kazuka M, Sugiyama R, Ito H, Isaka K. Anti-Müllerian hormone substance from follicular fluid is positively associated with success in oocyte fertilization during in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pabuccu R, Kaya C, Cağlar GS, Oztas E, Satiroglu H. Follicular-fluid anti-Mullerian hormone concentrations are predictive of assisted reproduction outcome in PCOS patients. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, Calhaz-Jorge C, D’Hooghe T, De Bie B, et al. European society of human reproduction and embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:400–412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, De Giorgi O, Consonni D, Crosignani PG, et al. Reproductive performance, pain recurrence and disease relapse after conservative surgical treatment for endometriosis: the predictive value of the current classification system. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2679–2685. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pop-Trajkovic S, Popović J, Antić V, Radović D, Stefanović M, Vukomanović P. Stages of endometriosis: does it affect in vitro fertilization outcome. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:224–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2013.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]