Abstract

Strawberry fruits (Fragaria vesca) are valued for their sweet fruity flavor, juicy texture, and characteristic red color caused by anthocyanin pigments. To gain a deeper insight into the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis, we performed comparative metabolite profiling and transcriptome analyses of one red-fruited and two natural white-fruited strawberry varieties in two tissues and three ripening stages. Developing fruit of the three genotypes showed a distinctive pattern of polyphenol accumulation already in green receptacle and achenes. Global analysis of the transcriptomes revealed that the ripening process in the white-fruited varieties is already affected at an early developmental stage. Key polyphenol genes showed considerably lower transcript levels in the receptacle and achenes of both white genotypes, compared to the red genotype. The expression of the anthocyanidin glucosyltransferase gene and a glutathione S-transferase, putatively involved in the vacuolar transport of the anthocyanins, seemed to be critical for anthocyanin formation. A bHLH transcription factor is among the differentially expressed genes as well. Furthermore, genes associated with flavor formation and fruit softening appear to be coordinately regulated and seem to interact with the polyphenol biosynthesis pathway. This study provides new information about polyphenol biosynthesis regulators in strawberry, and reveals genes unknown to affect anthocyanin formation.

Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) is one of the world’s most popular fruit crops with an annual production of more than 8.1 million tons in 2014 (http://faostat3.fao.org/browse/Q/QC/E). The strawberry is considered as “accessory fruit” because the fruit is not formed by the enlargement of the ovary but the edible, fruity pulp, also referred to as receptacle, is derived from adjacent tissue exterior to the carpel. The achenes (seeds) are distributed spirally across the epidermis of the pulp1. The development of the strawberry fruit is regarded independent of increased ethylene biosynthesis and respiration, which is why strawberries are considered non-climacteric fruits2, although recent studies suggest ethylene plays a role in strawberry fruit ripening3. The ripening process can be traced by observing the changes in fruit size and color. The stages are usually classified as green, white, turning, and red, and their development is accompanied by changing compositions of plant hormones and metabolites4. Strawberry fruits ripen quite fast within about 30 days. The plants are also small in size and easy to propagate. These qualities, together with an unusual fruit structure and color formation, have made the strawberry plant an advantageous model system to study fruit development. Woodland strawberry F. vesca has a small, sequenced genome (240 Mb), and is commonly used as a genetic model plant for the Rosaceae family and, in particular, the Fragaria genus.

Besides the appealing flavor, much of the attractiveness of strawberries is based on the bright red fruit-color caused by anthocyanin pigments4,5. Pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside, its 6′-O malonated derivative and cyanidin 3-O-glucoside are the major anthocyanins of strawberry fruit and are biosynthesized from phenylalanine by the phenylpropanoid-flavonoid-anthocyanin pathway, which has been thoroughly investigated by genetic, biochemical and metabolite profiling studies6. Anthocyanins are also associated with a large number of health-promoting effects. They possess anti-oxidative properties, have positive impacts on cardiovascular disorders and degenerative diseases, and are able to protect DNA integrity7,8,9. The basic biosynthetic pathway of anthocyanins is known, and most plant species share a large number of enzymatic reactions, although there are differences regarding the types of anthocyanins that accumulate10,11,12.

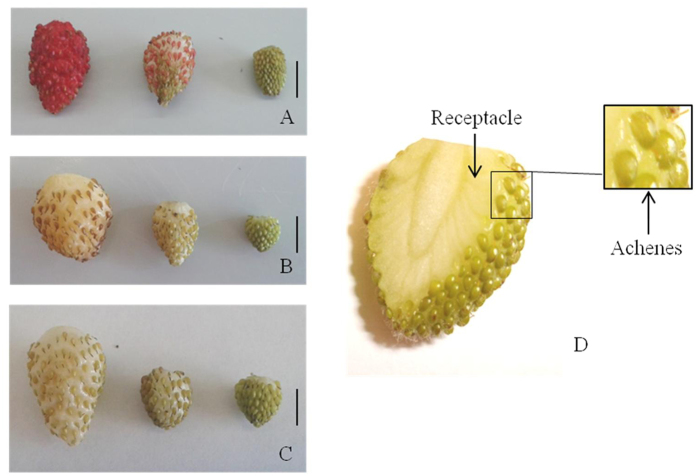

In contrast to the red-fruited F. vesca genotypes, there are also varieties that produce white fruits, even when they are fully ripened. This is not the result of continuous breeding or genetic modification, but a naturally occurring phenomenon. In the white-fruited varieties the pigment formation seems to be impaired by down-regulation of a single or multiple biosynthetic genes, or because an essential gene is non-functional. Key factors in the regulation of the flavonoid and anthocyanin pathway are MWB (MYB-bHLH-WD40) complex proteins13. In order to gain a deeper insight into the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis, we performed comparative metabolite profiling and transcriptome analysis of one red-fruited (F. vesca cv. Reine des Vallees (RdV)), and two white-fruited (F. vesca cv. Yellow Wonder (YW) and Hawaii 4 (HW4)) woodland strawberry varieties (Fig. 1) by liquid-chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry analysis (LC-MS), and RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), respectively. To survey gene expression during fruit development we performed RNA-Seq on green, intermediate and ripe (white-ripe and red-ripe, respectively) fruits, and separated the achenes (seeds) from the receptacle (pulp). To determine the metabolic differences between the three genotypes, the level of anthocyanins and relevant precursors were analyzed by LC-MS, and the expression pattern of candidate genes was validated by qPCR.

Figure 1.

Fruits of F. vesca variety Reine des Vallees (A), Yellow Wonder (B) and Hawaii 4 (C) of the ripening stages ripe (left), intermediate (middle) and green (right). Cross-section of a green fruit of F. vesca Hawaii 4 (D), with arrows indicating the tissues (receptacle, achenes) separated before RNA and metabolite extraction. Scale bars = 5 mm.

Our analysis completes a recently published F. vesca transcriptome data set, which provides gene expression data of the fruit development stages from fertilized flower to big green fruit14,15. Thus, the transcriptome of the complete strawberry fruit ripening process from flower to ripe fruit is now available, with our data covering green to ripe developmental stages (Supplementary data File S1). The analyses of the white-fruited genotypes show that the phenylpropanoid/flavonoid/anthocyanin metabolism and the gene transcript levels are already perturbed at early developmental stages in YW and HW4.

Results

Metabolite Analysis

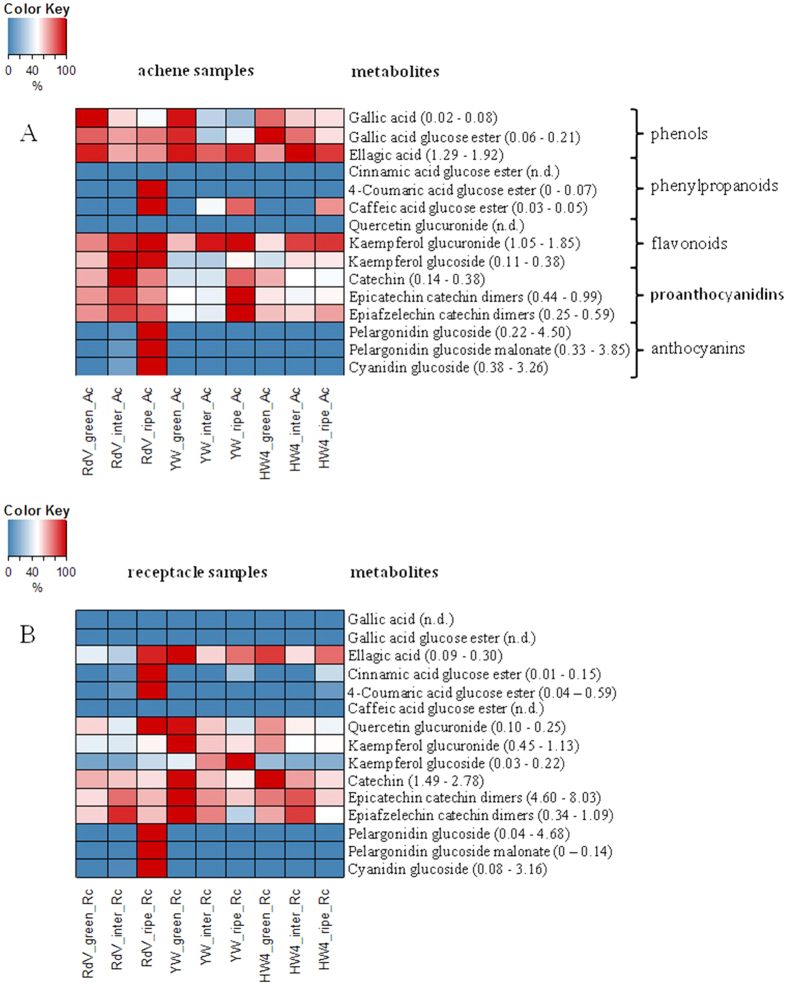

Untargeted and targeted metabolite analyses of phenols, phenylpropanoids, flavonoids, proanthocyanidins, and anthocyanins were performed by LC-MS in receptacles and achenes of green, intermediate and ripe fruits of F. vesca RdV, YW and HW4 (Figs 2 and 3). 271 untargeted metabolites showed variance between the three genotypes (p-value ≤ 0.01). Their analysis uncovered much lower variance in the data sets of the metabolites found in the achenes of RdV, YW, and HW4 than in the data of the receptacles (Fig. 2). The receptacles of the three F. vesca varieties clustered according to their developmental stages. Thus, metabolites that confer the red color to ripe RdV fruits did not strongly contribute to the variance in the data. Overall, according to the untargeted analysis, the major metabolites were similar in the three genotypes at the identical ripening stage. However, the targeted metabolite analysis showed, in line with the color change of the receptacle and achenes of RdV (Fig. 1), high levels of anthocyanins such as pelargonidin glucoside, pelargonidin glucoside malonate, and cyanidin glucoside in ripe receptacle and achenes of RdV, but not in fruits of YW and HW4 (Fig. 3). Each developmental stage and fruit tissue is dominated by a certain group of phenolic compounds. For instance, phenols such as gallic acid, gallic acid glucose ester and ellagic acid were major metabolites in green achenes of RdV, whereas flavonoids were abundant in intermediate achenes of RdV, and anthocyanins and phenylpropanoids dominated in the late developmental stage. In most cases, the levels of secondary metabolites in achenes and receptacle of the white-fruited genotypes differed considerably from the concentrations determined in the respective tissues of RdV. Although, gallic and ellagic acid accumulated in green achenes of YW to levels found in green achenes of RdV, the concentrations of flavonoids were significantly reduced. In contrast, in green receptacles of YW, the levels of flavonoids even exceeded the concentrations detected in the same tissue of RdV. Thus, the differential metabolite levels suggest that changes in secondary metabolism reflect organ and developmental specificities.

Figure 2. Untargeted analysis of secondary metabolites in receptacle and achenes of strawberry varieties RdV, YW, and HW4 of three developmental stages (green, intermediate, and ripe).

3–5 biological replicates per data point. The variance in the data is depicted by principal component analysis (PCA).

Figure 3. Quantification of secondary metabolites by LC-MS in achenes and receptacle of strawberry fruits.

Heatmaps show levels that are expressed as per mil equivalents of the dry weight (relative concentration), with lowest levels shown in blue, and highest levels in red. Individual min. and max. values are given in parentheses. (A) Colour code presentation of metabolite levels in achene (Ac) tissues of different ripening stages (green, intermediate, ripe), and F. vesca varieties (RdV, YW, and HW4). (B) Metabolite levels in receptacle (Rc) tissues. n.d. not detected. Three to five replicates were analyzed.

Global Analysis of the Fruit Transcriptome

Global mRNA sequencing of the receptacle and achenes of red-fruited F. vesca RdV variety, and both white-fruited F. vesca YW and HW4 varieties was performed to investigate the differential accumulation of transcripts. RNA was pooled from receptacles and achenes of ten fruits per sample to ensure high reliability regarding the stage of fruit ripening (Supplementary Table S1). Sequencing yielded 249,582,360 reads of 100 bp in length (Supplementary Table S2), giving ~25 billion nucleotides of total sequence data. After quality clipping, 245,603,827 reads were selected. The mapping of the selected reads to the F. vesca reference genome resulted in a total pool of 204,888,523 transcript counts (greater than 83% overall mapping rate, Supplementary Table S3). Subsequently, the read counts were normalized by DESeq2 size factors, and scaled to per million range (rpm: reads per million). Genes with fewer than 20 normalized counts summed across samples were considered as not expressed. Out of 33673 annotated F. vesca genes, 19208 were expressed above this threshold.

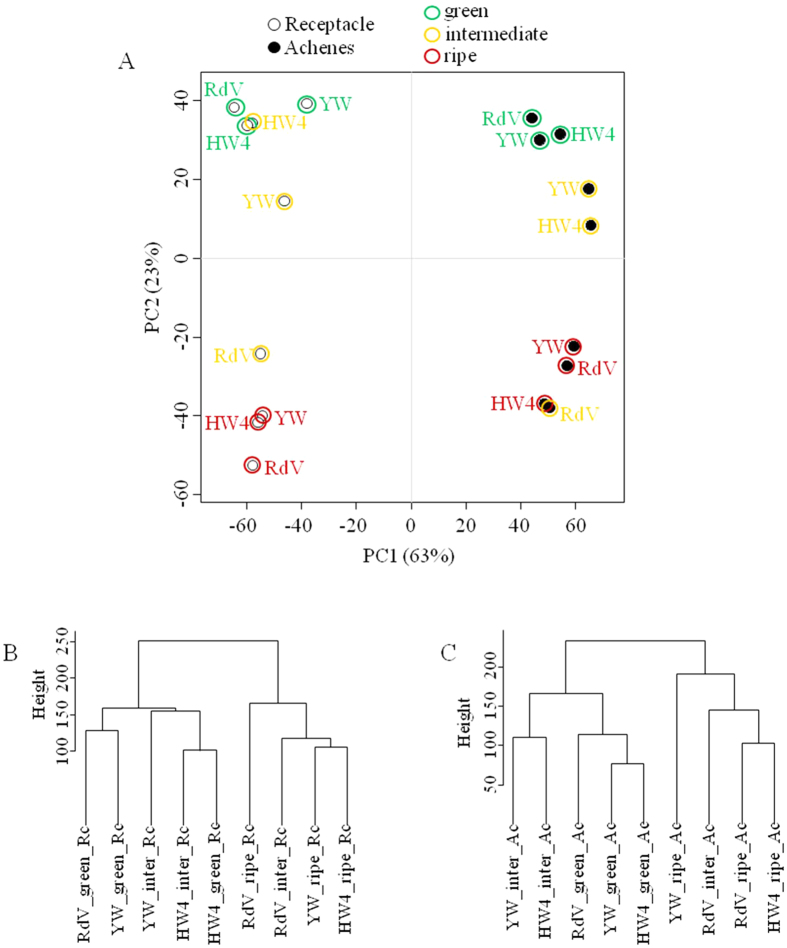

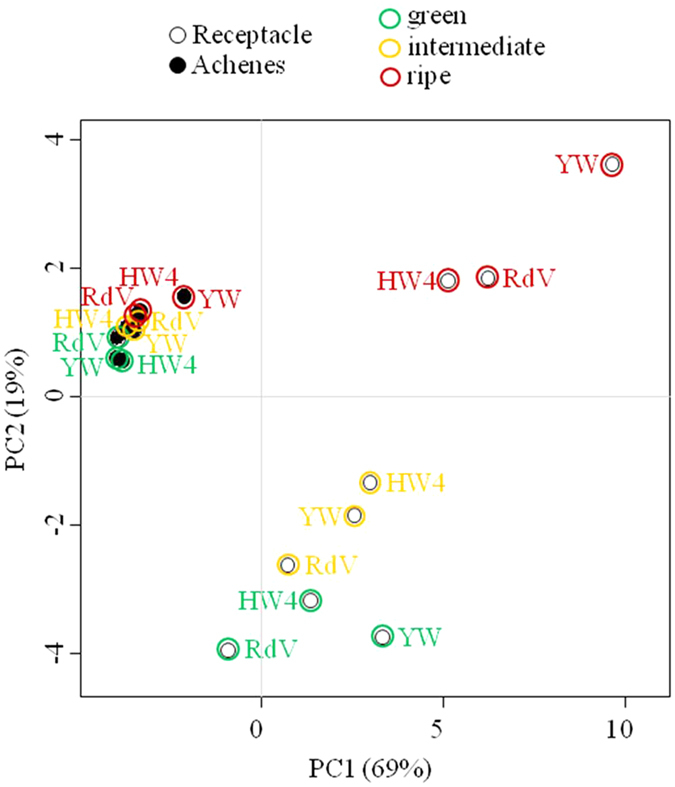

To investigate global gene expression relationships, we performed a principle component analysis (PCA), and visualized the correlations also by dendrograms of the achenes and receptacle data sets (Fig. 4). When the 500 most highly expressed transcripts were employed for PCA analysis, the receptacles and achenes were clearly set apart (left and right), as well as the green and ripe developmental stages (top and bottom, Fig. 4A). The receptacles and achenes of the intermediate ripening stage of YW and HW4 grouped with the green tissues, whereas the receptacle and achenes of intermediately ripened RdV clustered with the ripe tissues of all varieties. Thus, gene expression of the white genotypes at the intermediate stage is more closely related to green unripe tissue, and the intermediate stage of the red genotype RdV to the ripe tissues. This observation was also confirmed by hierarchical clustering of the achenes and receptacle data (Fig. 4B and C).

Figure 4. Global analysis of gene expression among samples and strawberry varieties.

(A) Principle component analysis (PCA) of transcripts (top 500) in F. vesca varieties RdV, YW, and HW4, in two different tissues (achenes and receptacle) and of three ripening stages green, intermediate and ripe. (B) Cluster dendrogram showing global relationship among achenes samples. (C) Cluster dendrogram showing global relationship among receptacle samples.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes between RdV and both white genotypes YW and HW4

To find candidate genes that might explain the loss-of-color phenotype in YW and HW4, differential expression between genotypes was assessed. Thirty-three genes were significantly down-regulated in white genotypes (YW, HW4) compared to the red genotype RdV (Table 1). Five genes encode enzymes with confirmed biochemical functions in F. vesca or F. × ananassa. Transcript levels of early (chalcone synthase FaCHS2–2: gene26826, chalcone isomerase FaCHI: gene 21346, and flavanone 3-hydroxylase FHT: gene14611), and late (dihydroflavonol reductase DFR: gene15176, anthocyanin synthase ANS: gene32347, and anthocyanin 3-O-glucosyltransferase FaGT1: gene12591) anthocyanin biosynthesis genes were equally reduced. Furthermore, gene31672 a predicted glutathione S-transferase is among the genes showing highest differential expression (logFC = −7.2), with transcripts accumulating almost exclusively in ripe and intermediate tissues of the red genotype RdV (Supplementary data File S1).

Table 1. Fold change (logFC) of genes significantly down-regulated in both white genotypes F. vesca YW and HW4 compared to the red genotype RdV.

| Gene_ID | logFC | SUM RdV | SUM YW | SUM HW4 | Prediction | Confirmed function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gene00395 | −1.9 | 732 | 315 | 151 | protein ZINC INDUCED FACILITATOR-LIKE 1-like (LOC101299619) | |

| gene01839 | −1.9 | 10,330 | 3,811 | 2,475 | probable cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (LOC101292655) | |

| gene04905 | −3.7 | 98 | 50 | 2 | receptor-like protein 12 (LOC101309371) | |

| gene05464 | −7.8 | 45 | 2 | 0 | uncharacterized sequence | |

| gene06602 | −1.7 | 2,566 | 922 | 710 | crocetin glucosyltransferase, chloroplastic-like (LOC101309923) | |

| gene07846 | −4.2 | 35 | 47 | 0 | pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein At1g12300, mitochondrial-like (LOC101315323) | |

| gene08163 | −5.0 | 58 | 30 | 0 | uncharacterized sequence | |

| gene10142 | −5.0 | 1,112 | 113 | 157 | 2-alkenal reductase NADP(+)-dependent-like (LOC101302097) | |

| gene12477 | −6.1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 12-oxophytodienoate reductase 3-like (LOC101293338) | |

| gene12565 | −4.2 | 1,996 | 591 | 187 | S-norcoclaurine synthase-like (LOC101292845) | |

| gene12591 | −9.2 | 2,341 | 10 | 6 | anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase 2 (LOC101300000) | GT127 |

| gene12759 | −3.4 | 310 | 370 | 3 | putative F-box/LRR-repeat protein 23 (LOC101304436) | |

| gene12884 | −4.0 | 394 | 4 | 95 | dirigent protein 1-like (LOC101292468) | |

| gene13009 | −4.3 | 76 | 12 | 3 | F-box protein CPR30-like (LOC101302499) | |

| gene14611 | −2.4 | 2,517 | 665 | 763 | naringenin, 2-oxoglutarate 3-dioxygenase (LOC101300182) | FHT6 |

| gene15176 | −3.6 | 715 | 307 | 133 | bifunctional dihydroflavonol 4-reductase/flavanone 4-reductase (DFR) (LOC101293459) | DFR37 |

| gene16103 | −1.4 | 771 | 318 | 268 | pyridoxal kinase (LOC101304704) | |

| gene16795 | −4.7 | 58 | 53 | 0 | uncharacterized sequence | |

| gene17181 | −5.7 | 8 | 0 | 0 | lysine histidine transporter-like 8 (LOC101292649) | |

| gene20261 | −8.0 | 45 | 3 | 0 | TMV resistance protein N-like (LOC101312392) | |

| gene21346 | −2.2 | 1,209 | 729 | 319 | probable chalcone--flavonone isomerase 3 (LOC101305307) | CHI10 |

| gene23269 | −2.7 | 221 | 277 | 4 | uncharacterized sequence | |

| gene24010 | −4.6 | 54 | 7 | 10 | uncharacterized sequence | |

| gene24179 | −1.7 | 648 | 202 | 160 | aspartic proteinase Asp1 (LOC101314219) | |

| gene25083 | −4.9 | 33 | 1 | 8 | 12-oxophytodienoate reductase 2-like (LOC101297812) | |

| gene26826 | −3.2 | 1,309 | 407 | 246 | polyketide synthase 1 (LOC101298456) | FvCHS2-235 |

| gene27955 | −4.9 | 69 | 6 | 1 | receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase SD1-8 (LOC101306554) | |

| gene30678 | −4.1 | 188 | 179 | 1 | transmembrane protein 184 homolog DDB_G0279555-like (LOC105350765) | |

| gene31672 | −7.2 | 678 | 17 | 1 | glutathione S-transferase F11-like (LOC101294111) | |

| gene32347 | −3.3 | 1,161 | 253 | 205 | leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase (LOC101308284) | ANS6 |

| gene32421 | −3.0 | 642 | 92 | 88 | protein P21-like (LOC101300343) | |

| gene32435 | −2.5 | 551 | 198 | 92 | short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase 2b-like (LOC101296098) | |

| gene33838 | −1.4 | 291 | 188 | 57 | AMP deaminase-like (LOC101301583) |

On the contrary, 31 genes were significantly up-regulated in both white genotypes (Table 2). Many candidates currently lack a functional prediction but show remarkable differences between the genotypes. For example candidate gene20847 (logFC = 10.7), almost not expressed in any tissues of RdV exhibits very high expression (up to 1,785 RPM) in tissues of HW4, and lower but considerable expression in tissues of YW. Furthermore, gene27422 a predicted transcription factor ORG2-like of the bHLH class is exclusively expressed in the white genotypes.

Table 2. Fold change (logFC) of genes significantly up-regulated in both white genotypes F. vesca YW and HW4 compared to the red genotype RdV.

| Gene_ID | logFC | SUM RdV | SUM YW | SUM HW4 | Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gene01275 | 6.7 | 0 | 7 | 8 | uncharacterized sequence |

| gene03760 | 5.3 | 4 | 67 | 87 | ceramide−1-phosphate transfer protein (LOC101298698) |

| gene04372 | 4.4 | 1 | 1 | 150 | mitochondrial saccharopine dehydrogenase-like oxidoreductase At5g39410 (LOC101312472) |

| gene07901 | 2.4 | 126 | 633 | 441 | 18.1 kDa class I heat shock protein-like (LOC101300322) |

| gene08062 | 7.1 | 0 | 10 | 10 | CDT1-like protein b (LOC101298288) |

| gene08537 | 2.5 | 82 | 339 | 403 | uncharacterized LOC101304935 (LOC101304935) |

| gene09254 | 4.5 | 3 | 8 | 442 | uncharacterized LOC101298543 (LOC101298543) |

| gene12602 | 6.4 | 0 | 1 | 99 | uncharacterized LOC101291726 (LOC101291726) |

| gene12786 | 3.8 | 4 | 8 | 138 | B3 domain-containing transcription factor VRN1-like (LOC101297387) |

| gene13191 | 1.5 | 1,127 | 2,885 | 3,654 | heat shock protein 83 (LOC101307345) |

| gene13320 | 2.1 | 63 | 207 | 337 | BCL2-associated athanogene 3 (BAG3) |

| gene16235 | 2.5 | 69 | 232 | 472 | homeobox-leucine zipper protein ATHB-6-like (LOC101309384) |

| gene16479 | 5.0 | 0 | 16 | 19 | cysteine synthase-like (LOC101302477) |

| gene16510 | 4.4 | 2 | 27 | 41 | uncharacterized LOC101294957 (LOC101294957) |

| gene19533 | 7.2 | 0 | 4 | 35 | putative receptor-like protein kinase At4g00960 (LOC105350176) |

| gene20844 | 9.1 | 0 | 15 | 99 | uncharacterized LOC105353058 (LOC105353058) |

| gene20847 | 10.7 | 6 | 1,038 | 5,630 | calmodulin-interacting protein 111-like (LOC101311429) |

| gene24034 | 5.2 | 5 | 68 | 142 | uncharacterized LOC101294593 (LOC101294593) |

| gene24512 | 11.3 | 0 | 159 | 225 | uncharacterized LOC101301427 (LOC101301427) |

| gene24545 | 2.8 | 56 | 335 | 226 | uncharacterized LOC101302298 (LOC101302298) |

| gene24775 | 5.8 | 0 | 3 | 10 | uncharacterized LOC101301427 (LOC101301427) |

| gene24779 | 7.1 | 0 | 8 | 18 | uncharacterized LOC101302918 (LOC101302918) |

| gene26609 | 2.9 | 16 | 74 | 140 | dolichyl-phosphate beta-glucosyltransferase (LOC101312675) |

| gene27422 | 10.3 | 0 | 25 | 426 | transcription factor ORG2-like (LOC101309207) |

| gene27944 | 6.0 | 0 | 0 | 67 | uncharacterized LOC101309177 (LOC101309177) |

| gene27945 | 4.9 | 0 | 0 | 209 | uncharacterized LOC101305101 (LOC101305101) |

| gene28620 | 8.7 | 0 | 20 | 43 | trifunctional UDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase/UDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-D-glucose 3,5-epimerase/UDP-4-keto-L-rhamnose-reductase RHM1-like (LOC101302674) |

| gene29781 | 7.2 | 0 | 15 | 11 | anthocyanidin 3-O-glucoside 2″-O-glucosyltransferase-like (LOC101310006) |

| gene30676 | 7.2 | 0 | 0 | 522 | uncharacterized sequence |

| gene30960 | 4.6 | 110 | 743 | 4,114 | uncharacterized sequence |

| gene32014 | 5.9 | 0 | 6 | 3 | ABC transporter C family member 10-like (LOC101302270) |

Transcript level profiles of known anthocyanin and flavonoid pathway genes during strawberry fruit development

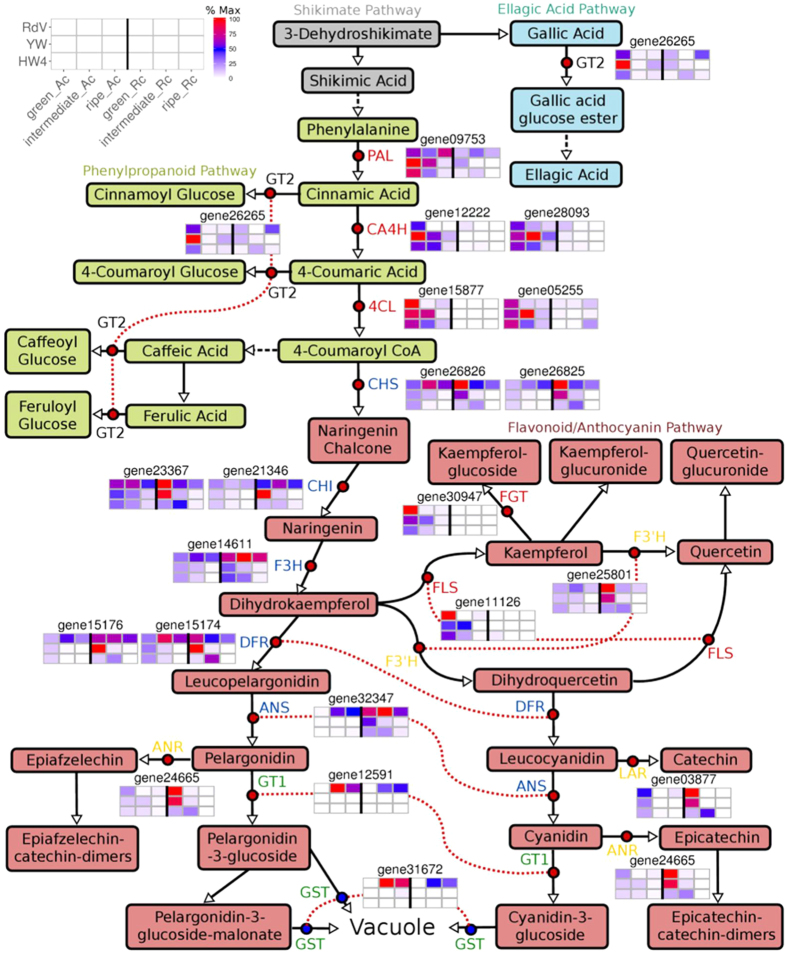

Next, we analyzed the transcript level profiles of anthocyanin and flavonoid pathway genes, whose encoded proteins have already been biochemically characterized. Gene expression levels in achenes and receptacle of RdV, YW, and HW4 of three developmental stages (green, intermediate and ripe) were compared (Fig. 5). Four groups of genes could be clearly distinguished by means of their transcript profiles. Early anthocyanin and flavonoid pathway genes such as PAL, CA4H, 4CL, FLS, and a flavonoid glucosyltransferase (FGT) gene show high expression levels in green achenes of RdV, YW, and HW4 as well as in achenes of YW and HW4 of the intermediate ripening stage (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). CHS, CHI, F3H, DFR, and ANS formed the second group. Transcript abundance of these genes was high in achenes and receptacles of RdV of all developmental stages but low in fruit of YW and HW4, except for green achenes and receptacle, and intermediate receptacle. Gene transcript levels of the first two groups differed considerably between the red- and white-fruited genotypes in achenes and receptacle at the intermediate (and ripe) developmental stage. However, the most significant difference was observed for the mRNA abundance of the anthocyanidin glucosyltransferase gene FaGT1 and an uncharacterized glutathione S-transferase gene. Both were exclusively expressed in fruit of RdV at the intermediate and ripe developmental stage. F3′H, ANR, and LAR formed the fourth group. They were primarily expressed in the green fruit of the three genotypes, and in intermediate receptacle of HW4. The transcript profiles of F3′H, ANR, and LAR in fruit of HW4 was clearly different from that of RdV and YW. Thus, gene expression perturbation of flavonoid pathway genes in HW4 occurs already in the green developmental stage. The glucosyltransferase gene FaGT2 was mainly expressed in green achenes of the three genotypes, and ripe receptacles of RdV.

Figure 5. Schematic illustration of the shikimate, ellagic acid, phenylpropanoid, flavonoid and anthocyanin pathway.

Red dots indicate biochemically characterized enzymes in strawberry fruit: ANS, anthocyanidin synthase; ANR, anthocyanidin reductase; CA4H, cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; CHS, chalcone synthase; 4CL, 4-coumaroyl-CoA ligase; DFR, dihydroflavonol reductase; FGT, flavonoid glucosyltransferase; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3′H, flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase; FLS, flavonol synthase; GT1, anthocyanidin glucosyltransferase; GT2, (hydroxy)cinnamic acid and (hydroxy)benzoic acid glucosyltransferase; LAR, leucoanthocyanidin reductase; PAL, phenylalanine ammonia lyase. Blue dots indicate putative GST, glutathione S-transferase. Identical genes are connected by a dotted red line when adjacent. Enzymes shown in the same color are co-regulated. Heatmaps show relative transcript levels (% Max) of genes in receptacle (Rc) and achenes (Ac) of F. vesca RdV, YW, and HW4 at the green, intermediate and ripe developmental stage.

Expression levels of genes involved in fruit softening and flavor formation

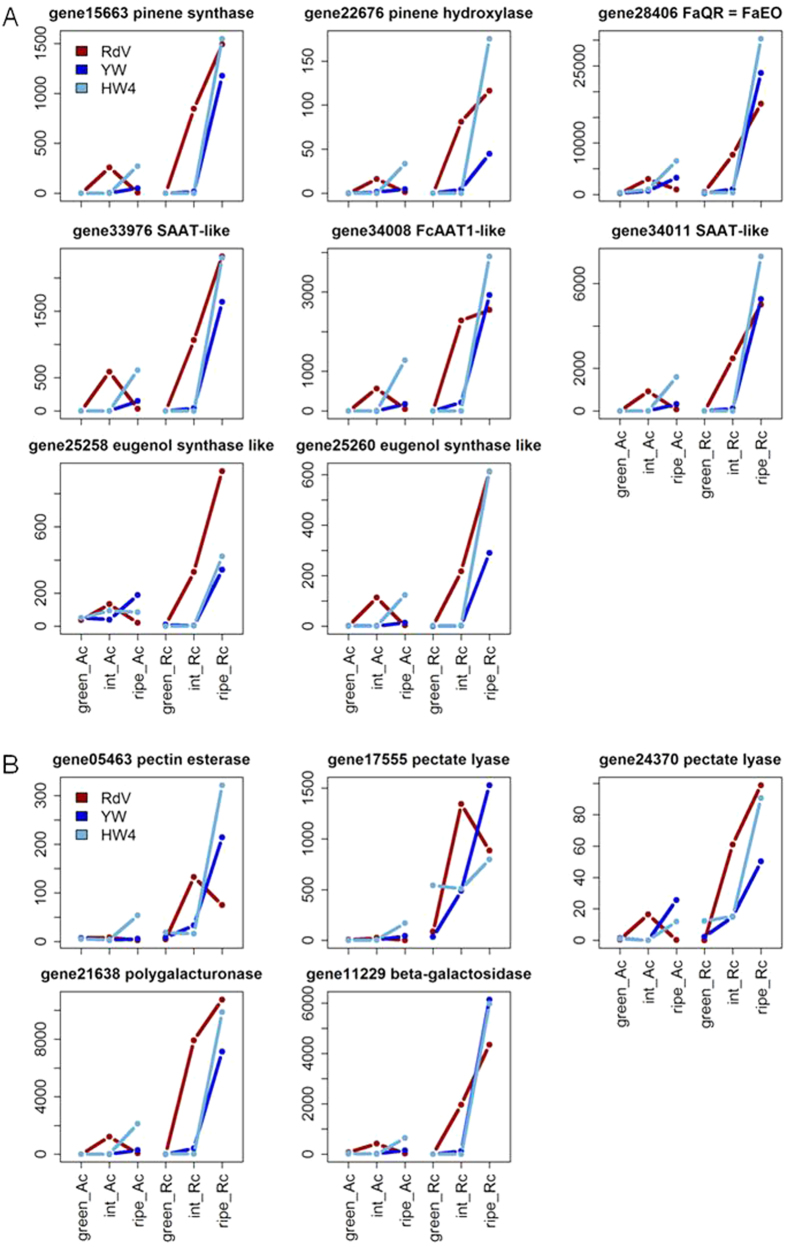

Finally, we wanted to know whether the impaired anthocyanin pathway in YW and HW4 affects the expression of genes involved in fruit flavor formation, and fruit softening. Transcript levels of well-characterized genes associated with volatile terpene (pinene synthase and hydroxylase), ester (acyltransferases FcAAT1, and SAAT), furaneol (FaQR), and eugenol (eugenol synthase) formation, as well as genes affecting fruit softening (pectin esterase, pectate lyase, polygalacturonase and beta-galactosidase) were analyzed in the data sets of RdV, YW, and HW4 (Fig. 6). The genes showed a similar ripening-related expression profile in the receptacles of the three genotypes, peaking at the ripe stage. It seems that the ripening process is slowed down in the white-fruited genotypes in comparison to RdV, because transcripts of genes involved in fruit flavor production, and degradation of cell wall polysaccharides are already abundant in receptacle of RdV at the intermediate stage, whereas these genes are almost solely expressed in ripe receptacle of YW and HW4.

Figure 6.

Transcript levels (normalized RPM) of genes encoding enzymes involved in fruit flavor formation (A) and softening (B) in receptacle (Rc) and achenes (Ac) of F. vesca RdV, YW, and HW4 at the green, intermediate (int) and ripe developmental stage.

Discussion

Considerable information on the polyphenolic composition of commercial strawberry fruit (F. × ananassa)16,17,18 and woodland strawberry F. vesca fruit19,20,21 exist. However, data on the levels of phenolics in developing F. vesca fruits is missing, completely. The bright color of red-fruited strawberries is due to four major anthocyanins, pelargonidin 3-glucoside, pelargonidin 3-glucoside 6′-malonate, pelargonidin 3-rutinoside and cyanidin 3-glucoside22,23,24,25, which are formed by the phenylpropanoid/flavonoid/anthocyanin pathway during fruit ripening6,26,27. In white colored strawberries, these anthocyanins are reduced in the receptacle, and in some cases also in the achenes28,29,30. Similarly, only trace amounts of pelargonidin 3-glucoside, pelargonidin 3-glucoside 6′-malonate, and cyanidin 3-glucoside were detected in the ripe receptacle and achenes of YW and HW4; in contrast to their high abundance in fruit of RdV (Fig. 3). Untargeted analysis of secondary metabolites by PCA separated the achenes from the receptacles, whereas the receptacles were further subdivided according to their ripening stage (Fig. 2). Ripe fruit of RdV, YW, and HW4 clustered in the PCA plot, but can be readily differentiated by the different pigmentation (Fig. 1). Thus, the anthocyanin level in RdV fruit is not the primary variance in the data.

Although, green achenes of RdV, YW, and HW4 accumulated comparable levels of gallic acid, gallic acid glucose ester, and ellagic acid, the immature seeds of the three genotypes can be clearly differentiated by their varying flavonoid concentration (Fig. 3). Achenes of RdV exhibited a tri-phasic polyphenol accumulation profile. The levels of phenols, flavonoids, and anthocyanins/phenylpropanoids peaked in green, intermediate, and ripe seeds of the red-fruited genotype, respectively. During ripening of YW and HW4, flavonoids did not reach the concentrations found in RdV, except for kaempferol glucuronide in intermediate and ripe achenes of both white-fruited genotypes, and epicatechin catechin and epiafzelechin catechin dimers in ripe achenes of YW. In addition, the total amount of polyphenols is reduced in the white-fruited genotypes. Receptacles of RdV showed a bi-phasic formation of polyphenols, as flavonoid levels peak at the intermediate ripening stage, and anthocyanins, quercetin glucuronide, phenylpropanoids, and ellagic acid are abundant in the ripe pulp. In contrast, receptacles of YW contained high levels of ellagic acid and flavonoids with declining concentrations during ripening, except kaempferol glucoside. HW4 displayed a mixed pattern of polyphenol accumulation in the pulp, whereas the lowest levels were found at the ripe developmental stage. Overall, the divergent profiles of secondary metabolites suggest an interference of the pathway in the white-fruited genotypes YW and HW4 at an early developmental stage.

In addition to metabolite profiling, gene transcript abundance was quantified by RNA-seq analysis in achenes and receptacles of the red- and white fruited varieties during fruit ripening. Analysis of global gene expression by PCA separated the achenes from the receptacles, as well as green from ripe tissues (Fig. 4A). Intermediate receptacle and achenes of YW and HW4 clustered with green fruit samples, and intermediate pulp and seeds of RdV with ripe fruit samples. This indicates that variance in gene expression is highest between samples of the intermediate ripening stage, and confirms the hypothesis that the ripening process in YW and HW4 is already affected at an early stage. In contrast, the untargeted analysis of the metabolites did not show equal variance, as the achene samples of all genotypes grouped together (Fig. 2). On the other hand, ripe receptacle of RdV, YW and HW4 grouped together in the PCA of the transcripts (Fig. 4A), similar to the PCA of secondary metabolites (Fig. 2).

Analysis of differentially expressed genes revealed that expression of major genes in the anthocyanidin/flavonoid biosynthesis pathway was down-regulated in the white varieties (Table 1). The expression of the branch point gene CHS (gene26826 polyketide synthase 1) was severely reduced. CHS expression is known to be associated with fruit coloring, because artificial down-regulation of CHS function via antisense and RNAi methods leads to pigment loss in flowers or fruits of different plant species31,32,33,34,35. Furthermore, five genes acting downstream of CHS were also clearly down-regulated (Table 1). The protein encoded by CHI (gene21346 chalcone-flavonone isomerase 3) catalyzes the conversion of naringenin chalcone to the flavanone naringenin, thereby producing the basic skeleton of all flavonoid metabolites10. The protein encoded by FHT (gene14611 naringenin, 2-oxoglutarate 3-dioxygenase) oxidizes the central B ring of the flavanone naringenin to produce dihydrokaempferol10. The enzyme encoded by DFR (gene15176 bifunctional dihydroflavonol 4-reductase/flavanone 4-reductase) reduces dihydrokaempferol to colorless leucoanthocyanidins36,37. The polypeptide encoded by ANS (gene32347 leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase) generates colored anthocyanidins like pelargonidin38, and the protein encoded by FaGT1 (gene12591 anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase 2) stabilizes the anthocyanidins by glucosylation27. The resulting anthocyanins accumulate, and are responsible for the coloring of fruits and flowers39. Thus, formation of anthocyanin precursors is considerably hampered in the white varieties. Among the significantly down-regulated candidates is also gene31672, a glutathione S-transferase (GST, Table 1) orthologous to GST Solyc02g081340 from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Transgenic tomato fruits exhibiting higher anthocyanin content showed increased expression of Solyc02g08134040,41, whereas expression in the anthocyanin absent mutant was barely detectable42. It has been proposed that anthocyanins might be transported into vacuoles via the noncovalent activity of GSTs43. Several GST genes with such functions have been characterized in plants including the TT19 gene (encoding a type I GST) of Arabidopsis, Bronze-2 (encoding a type III GST) of maize, AN9 (encoding a type I GST) of petunia44,45,46 and two GST genes from grape47. Therefore, gene31672 might act in anthocyanin transport.

In addition to genes down-regulated in the white genotypes, also candidates significantly up-regulated were found (Table 2), such as a yet uncharacterized transcription factor (TF) of the bHLH class (gene27422 ORG2-like). It is widely acknowledged that TFs of the MYB and bHLH protein classes regulate the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes48,49. MYBs linked to the anthocyanin pathway possess a highly conserved DNA-binding domain, which usually comprises two repeats (R2R3)49, and are suggested to interact with bHLH TFs48. Both, activators and repressors are known50,51. The bHLH proteins have not been extensively studied in plants. Those that have been characterized function in anthocyanin biosynthesis, phytochrome signaling, globulin expression, fruit dehiscence, and carpel and epidermal development52,53. Consequently, gene27422 could encode a bHLH TF regulating pigment formation in strawberry fruit. Recently, MYB10 (encoded by gene31413) was characterized as positive regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in F. × ananassa50, and F. vesca54. RNAi-mediated down-regulation of MYB10 resulted in significant reduction of anthocyanin concentration in ripe receptacle of red-fruited F. × ananassa, and F. vesca varieties, while over-expression resulted in dark red fruits50,54,55. Furthermore, recent transcriptomic and SNP variant analysis revealed a single amino acid change in the MYB10 protein of the white-fruited varieties YW and HW4 that could be responsible for the loss-of-colour phenotypes56. Our data showed that MYB10 transcripts were more abundant in ripe receptacles of the white-fruited varieties YW and HW4 than in red-fruited RdV (Supplemental Figure S3A) contradicting the observation that MYB10 is not differentially expressed in YW in comparison to the red-fruited F. vesca variety Ruegen57. Although MYB10 seems to be an important regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in receptacle, our data indicated that MYB10 might also have a significant role in ripe achenes due to the high transcript level. However, metabolic and transcriptional variations in fruit of natural white-fruited Fragaria vesca genotypes were already found at early developmental stages where MYB10 is almost not transcribed. Therefore, additional transcriptions factors might account for these differences. MYB1, a transcriptional repressor in regulating the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in strawberry29,51,58, was not among the differentially expressed genes (Supplemental File S1). This indicates that MYB1 might not be the anthocyanin biosynthesis repressor responsible for the loss-of-color phenotype in the white-fruited F. vesca genotypes.

Amongst the differentially expressed genes (Tables 1 and 2) are candidates featuring comparable RPM levels in both white genotypes, such as gene01839 and gene13191. In contrast, other candidates showed diverging levels, such as gene30676 and gene30960. This indicates that in addition to metabolic differences among the two white genotypes (Fig. 3), also transcriptional differences can be found.

The general biosynthesis pathway of anthocyanins has been thoroughly investigated at both, the biochemical and the genetic level, in particular in A. thaliana and Vitis sp.49,59. Also in the Fragaria genus the key flavonoid pathway genes have been cloned, and their encoded proteins functionally characterized6. Enzymatic analysis of PAL, CHS/CHI, F3H, FLS, flavonoid 3-O-GT, and flavonoid 7-O-GT activity in crude fruit extracts demonstrated two distinct activity peaks during fruit ripening at early and late developmental stages for all enzymes except FLS60. The high activity at the immature stage corresponds to the formation of flavanols, while the second peak is clearly related to anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation60. According to our data, a biphasic transcript expression pattern for the flavonoid pathway genes was not observed (Fig. 5). Instead, genes could be grouped into classes according to their expression profiles in receptacle and achenes. Transcripts of key genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway (PAL, CA4H, and 4CL) were highly abundant in immature seeds of F. vesca, and their expression profile suggests a coordinated transcriptional regulation in receptacles and achenes during fruit ripening (Fig. 5). At the gateway of primary metabolism PAL, CA4H, and 4CL play a pivotal role as they are producing the precursor molecules of all polyphenols, including lignin. High degree of coordination in the overall expression of these three genes has been shown in parsley leaves, and cell cultures treated with UV light or fungal elicitor61. The gene expression profile of FLS and a putative flavonoid GT (gene30947 FGT) matched the transcript expression pattern of the phenylpropanoid genes, but act more downstream in the flavonoid pathway (Fig. 5). The fruit ripening program in red-fruited RdV is characterized by down-regulation of PAL, CA4H, and 4CL in achenes of the intermediate developmental stage, which did not occur in seeds of YW and HW4. Thus, in immature fruit the early polyphenol biosynthesis pathway is already differently regulated in the red- and white-fruited genotypes. Similarly, flavonoid genes (CHS, CHI, F3H, DFR, and ANS) were coordinately expressed in a spatial and temporal manner (Fig. 5). They are involved in the supply of precursor molecules for proanthocyanidin, flavonoid, and anthocyanin production. In apple fruit, the anthocyanin biosynthetic genes, CHS, F3H, DFR, and ANS, are coordinately expressed during red coloration in skin, and their levels of expression are positively related to anthocyanin concentration62. Transcript levels of the flavonoid genes were particularly abundant in green receptacle of YW in comparison to HW4 (Fig. 5) and might, therefore, contribute to the high levels of flavonoids and proanthocyanidins in green pulp of YW (Fig. 3). The differential expression of the anthocyanidin glucosyltransferase gene FaGT127 (gene12591), in the red-fruited and white-fruited F. vesca genotypes is striking (Fig. 5). Similarly, white-colored grape cultivars appear to be lacking anthocyanins because of the absence of an anthocyanidin GT63. In apple fruits, the transcript expression level of an anthocyanidin GT is positively related to anthocyanin concentration, and the gene is coordinately expressed with CHS, F3H, DFR, and ANS during red coloration in apple skin62. Moreover, late genes in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway are coordinately expressed during red coloration of litchi fruits, where low expression of DFR and GT result in absence or extremely low anthocyanin concentrations64. Interestingly, the transcript expression pattern of the putative GST candidate gene (gene31672) matched exactly the expression of FaGT1 (Fig. 5), emphasizing its putative role in anthocyanin transport. The transcript expression profile of FaGT2 (gene26265), a gene encoding a (hydroxyl)cinnamate GT65 suggests that GT2 might contribute to the production of gallic acid glucose ester (Fig. 3) in early developmental stages and to the production of (hydroxyl) cinnamic acid glucose esters in stages66.

The formation of red pigments would require the maintenance of high expression levels of CHS, CHI, F3H, DFR, and ANS in the receptacle and achenes, as well as the down-regulation of PAL, CA4H, and 4CL in achenes of the intermediate ripening stage. In the white-fruited F. vesca genotypes, transcript expression profiles of the proanthocyanidin biosynthesis genes (F3′H, ANR, and LAR) and the pattern of flavonoid genes (CHS, CHI, F3H, DFR, and ANS) were coordinately regulated, and their ripening program appears to be unable to switch from the biosynthesis of flavonoids and proanthocyanidins occurring at the early stage to the production of anthocyanins in later stages. The polyphenol biosynthesis pathway in fruit of HW4 seems to be disturbed at an even earlier stage, as proanthocyanidin biosynthesis genes are already weakly expressed in green receptacle of HW4.

The interaction of polyphenol metabolism and fruit flavor formation has been frequently demonstrated as phenolic compounds can act as precursors of flavor molecules67. Thus, expression profiles of functionally characterized flavor biosynthesis genes pinene synthase and hydroxylase68, AAT69, QR70, and eugenol synthase67 were analyzed in the three genotypes (Fig. 6A). Transcripts of flavor genes were already abundant in red-fruited RdV at the intermediate fruit ripening stage, whereas in YW and HW4 mRNA of genes involved in flavor formation were only detectable at the ripe stage. It appears that the ripening program in the white-fruited genotypes is delayed, which is also supported by the comparison of the transcript profiles of the fruit softening genes pectin esterase71, pectate lyase72, polygalacturonase73, and beta-galactosidase74 in RdV and YW, as well as in HW4 (Fig. 6B). Overall, the flavor and softening genes seem to be coordinately regulated. It has been shown, that ripe fruits of red and white F. vesca varieties share most volatile organic compounds. Varying levels among the genotypes occur, but the main compounds such as esters presumably formed by AATs are present75.

Material and Methods

Plant Material

F. vesca Reine des Vallees (RdV), Yellow Wonder (YW) and Hawaii 4 (HW4) are three botanical forms of F. vesca, all of which produce small-sized plants and propagate without runners, except HW4. RdV has fruits with red flesh and red skin, whereas YW and HW4 fruits have both yellow flesh and skin (Fig. 1). The genetic and growth characteristics of YW and HW4 have been described56. F. vesca cv. RdV, YW and HW4 strawberry plants were grown at the Call Unit for plant research (Technische Universität München, Germany). Fruits were harvested in three ripening stages green [~10 days post-anthesis (DPA)], intermediate [~25 DPA], and ripe [~35 DPA] according to literature4,26. Fruits were sampled between May and August 2014/2015, frozen in liquid nitrogen directly after harvest, and stored at −80 °C until further usage (Fig. 1).

Chemicals

Except where otherwise stated, chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany), Fluka (Steinheim, Germany) or Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany).

RNA-Isolation, -Quantity and -Quality Assessment

For RNA isolation achenes were separated from the pulp, and each sample was ground to a fine powder by mortar and pestle. Three woodland strawberry varieties (Fragaria vesca cv. RdV, YW, and HW4), three fruit ripening stages (green, intermediate, ripe) and two tissues (achenes, receptacle), in total 18 different samples were processed. For each sample the RNA of 10–15 fruits was pooled. Total RNA was extracted according to the CTAB protocol (Liao et al., 2004). DNA was removed by treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Germany) for 1 h at 37 °C. RNA yields were measured and the RNA Integrity Number (RIN, Supplementary Table S1) was determined on a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Germany) equipped with a RNA 6000 Nano Kit.

RNA Sequencing and Library Preparation

Total RNA was sent to Eurofins Genomics (Germany), where RNA sequencing and library preparation was carried out. The 3′ fragment cDNA library was generated through fragmentation of total RNA by ultrasound before poly(A)-tailed 3′-RNA fragments were isolated using oligo-dT chromatography. Then, an RNA adapter was ligated to the 5′-ends of the poly(A)-tailed RNA fragments. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using an oligo(dT)-adapter primer and reverse transcriptase. The resulting cDNA was PCR-amplified using a high fidelity DNA polymerase. Each final cDNA library was purified, size selected, quantified and analyzed by capillary electrophoresis before RNA-Seq analysis was performed on an Illumina HiSeq2000 platform (Illumina Inc., USA). A PhiX library (Illumina Inc., USA) was added before sequencing to estimate the sequencing quality. Reads were processed by the CASAVA 1.8 package. Sequencing results are summarized in Supplementary Table S2.

Quality Trimming, Mapping and Data Normalization

RNA-seq data processing was performed on Galaxy, a free public server that was installed locally76,77,78. The Application Programming Interface (API) and the Galaxy Data Manager were used for automation of the pipeline analyses79, and handling of built-in reference data80, respectively. The bioinformatics tools were installed and organized via the Galaxy ToolShed81. http://www.rosaceae.org/Reads were trimmed using the Trimmomatic tool82 with default settings for single end reads. The TruSeq3 adapters were removed in an initial ILLUMINACLIP step. Quality trimming was performed with a SLIDINGWINDOW step, and finally reads below 20 bp were discarded with a MINLEN step. Before and after trimming, the overall data quality was evaluated with the FastQC software (quality control tool for high throughput sequence data http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/).

Trimmed reads were aligned to the F. vesca reference genome (version 2.0.a1 downloaded from Genome Database for Rosaceae, GDR, www.rosaceae.org83) with TopHat84 using default settings. The results of the read mapping are summarized in Table S3. Aligned reads were quantified using HTSeq-count85 in “Union” mode for stranded reads with a minimum alignment quality of 10. The gene prediction input file was downloaded from GDR83. As poly A-tail selection was performed after fragmentation of the RNA, reads were derived from only the 3′ ends of transcripts and normalization by gene length to Reads Per Kilobase of exon per Million mapped reads (RPKM) or Transcripts per Million (TPM) would be inappropriate. Instead, the raw read counts were normalized for library size using the DESeq2 R package86, and adjusted to per million scale (divided by total normalized counts for all samples, times 18 for sample number, times 1,000,000), to produce normalized rpm.

Differential Expression

Deferentially expressed genes were defined using the general linear models in edgeR87. Specifically, models were fitted with a factor for tissue, stage, and mature color of genotype and likelihood ratio test was performed comparing the white genotypes (YW and HW4) to RdV. The false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated according to88 and genes with FDR < 0.05 were considered significant. Accession numbers of flavonoid genes differentially expressed in the red- and white-fruited genotypes and transcription factors analyzed in this study are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Flavonoid genes differentially expressed in the red- and white-fruited genotypes and transcription factors analyzed in this study.

| GT1 | gene12591 | XM_004307828 |

| F3H | gene14611 | XM_004287766 |

| DFR | gene15176 | XM_004291810 |

| CHI | gene21346 | XM_004307686 |

| CHS2-2 | gene26826 | XM_004306495 |

| ANS | gene32347 | XM_004298672 |

| GST | gene31672 | XM_004288530 |

| ORG2 (bHLH) | gene27422 | XM_004290363 |

| MYB10 | gene31413 | XM_004302169 |

| MYB1 | gene09407 | XM_004299494 |

Global Sequencing Data Analysis

The data were analyzed in R (R Core Team, 2015), employing appropriate packages mostly accessed via the open source software framework Bioconductor89. Before the cluster dendrogram was generated, the dataset was transformed using variance stabilization90. Subsequently, hierarchical clustering was performed using the complete method and Spearman distance metric. The PCA analysis was performed according to ref. 91. For assignment of functional gene predictions, MapMan “BINs”92 and open-source F. vesca gene ontology (GO) annotation93,94 were used.

Metabolite Extraction

50 mg of lyophilized fruit powder was weighed (n = 3–5). The resulting samples were extracted with 250 μl of internal standard solution (0.2 mg ml−1 biochanin A and 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-glucuronide in methanol) and 250 μl methanol. After vortexing (1 min), sonication (10 min), and centrifugation (10 min, 16,000 g) the supernatant was collected. The residue was re-extracted with 500 μl methanol, and the supernatants were combined and dried in a vacuum concentrator. The secondary metabolites were re-dissolved in 50 μl of water, vortexed, sonicated and centrifuged. The clear supernatant was used for LC-MS analysis.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

Levels of secondary metabolites were determined on an Agilent 1100 HPLC/UV system (Agilent Technologies, Germany) equipped with a reverse-phase column (Luna 3 u C18(2) 100 A, 150 × 2 mm; Phenomenex, Germany), a quaternary pump, and a variable wavelength detector. Connected to the HPLC was a Bruker esquire3000plus ion-trap mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Germany). HPLC and mass spectrometry were performed at optimized conditions33,95. Resulting data were analyzed with Data Analysis 5.1 software (Bruker Daltonics, Germany), and metabolites were identified using the in-house database. Levels (per mil equivalents of the dry weight, ‰ equ. dw.) of secondary metabolites quantified during targeted analyses are summarized in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5.

Untargeted Metabolite Data Analysis

Untargeted metabolite profiling analysis of the LC-MS data set was done according to published reports96,97,98 in R (Fig. 3). Peaks were grouped together across samples after correction of retention time deviations. After integration of the peak areas, the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test was used to determine differences across genotypes (RdV, YW, and HW4). Only metabolites with a p-value ≤ 0.01 were used for computation of subsequent data analysis. The secondary metabolites were quantified according to the internal standard method95, and the values are expressed as per mil equivalent of the dry weight (‰ equ. dw). Hierarchical clustering and PCA analysis were generated by the same R packages used for the sequencing data91.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

The same total, DNAse I treated RNA used for RNA-sequencing, was also used to confirm candidate gene expression by RT-PCR analysis. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed in 20 μl reactions, containing 1 μg of total RNA template, 10 μM of Oligo (dT) 15 primers, and 200 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase (both Promega, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Analyses were carried out on a StepOnePlusTM System (Applied BiosystemsTM, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, US-MA) equipped with StepOneTM software v2.1. For each PCR reaction (10 μl in total), 2 μl cDNA, 400 nM primers, and 5 μl 2x master mix (SensiFastTM SYBR Hi-Rox Kit, Bioline,) were used. Prior to gene expression analysis, PCR reactions were optimized in cDNA concentration, primer concentration, and annealing temperature (FvGT1 gene12591: 1x cDNA, 61 °C; FvMYB10 gene31413: 0.1x cDNA, 57 °C; FvUBC9 gene12591: 0.1x cDNA, 55 °C; 400 nM primers for all three genes). The efficiency of each primer pair was determined using the standard curve of a serial cDNA dilution. Several possible reference genes from literature were tested, but in the end only FvUBC9 was suitable, amplified by a primer set according to literature54 (Table S6). It was, however, differentially expressed between achenes and receptacle, but showed uniform levels within the respective tissue (Figure S3). Achenes and receptacle samples were, consequently, normalized separately. The cycling program was 2 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 5 sec at 95 °C, 10 sec at 55–61 °C, and 20 sec at 72 °C, and ending in a melting curve detection of 15 sec at 95 °C, 1 min at 60 °C, and 15 sec at 95 °C. Analyses were performed in triplicates. Relative quantification was performed according to99 using UBC9 as reference gene.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Härtl, K. et al. Early metabolic and transcriptional variations in fruit of natural white-fruited Fragaria vesca genotypes. Sci. Rep. 7, 45113; doi: 10.1038/srep45113 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Karen-Svenja Graul for her help with the LC-MS sample preparation. Furthermore, we thank Benedikt Kirchner and Prof. Dr. Michael Pfaffl (Chair of Physiology, Technical University Munich) for a helpful R introduction, and for providing their Bioanalyzer for determination of the RIN values. We would also like to acknowledge the help of Prof. Dr. Hans-Rudolf Fries (Chair of Animal Breeding, Technical University Munich), who helped with the setup of data analyses. Moreover, we acknowledge the financial support provided by SFB924 and GOODBERRY (European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme; grant agreement No 679303).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions W.S., T.H. and K.H. conceived and designed the experiments; K.H. and K.F.O. and M.S. performed the experiments; A.D., K.H. and T.H. carried out the bioinformatic analysis; K.H., W.S., A.D. and B.U. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Perkins-Veazie P. Growth and ripening of strawberry fruit. Hortic. Rev. 17, 267–297 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni J. J. Genetic regulation of fruit development and ripening. Plant Cell 16, 170–180 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchante C. et al. Ethylene is involved in strawberry fruit ripening in an organ-specific manner. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 4421–4439 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Metabolic profiling of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) during fruit development and maturation. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 1103–1118 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koes R., Verweij W. & Quattrocchio F. Flavonoids: a colorful model for the regulation and evolution of biochemical pathways. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 236–242 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J. R. M. et al. Characterization of major enzymes and genes involved in flavonoid and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis during fruit development in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 465, 61–71 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafra-Stone S. et al. Berry anthocyanins as novel antioxidants in human health and disease prevention. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 51, 675–683 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Teresa S. de, Moreno D. A. & García-Viguera C. Flavanols and anthocyanins in cardiovascular health: a review of current evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 11, 1679–1703 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. & Giusti M. M. Anthocyanins: natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 1, 163–187 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forkmann G. Flavonoids as Flower Pigments. The formation of the natural spectrum and its extension by genetic engineering. Plant Breed 106, 1–26 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Holton T. A. & Cornish E. C. Genetics and Biochemistry of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. Plant Cell 7, 1071–1083 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springob K., Nakajima J.-I., Yamazaki M. & Saito K. Recent advances in the biosynthesis and accumulation of anthocyanins. Nat. Prod. Rep. 20, 288 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubos C. et al. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 15, 573–581 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C. et al. Genome-scale transcriptomic insights into early-stage fruit development in woodland strawberry Fragaria vesca. Plant Cell 25, 1960–1978 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish O. et al. SGR: an online genomic resource for the woodland strawberry. BMC Plant Biol. 13, 223 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby K., Ekeberg D. & Skrede G. Characterization of phenolic compounds in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) fruits by different HPLC detectors and contribution of individual compounds to total antioxidant capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 4395–4406 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaby K., Mazur S., Nes A. & Skrede G. Phenolic compounds in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) fruits: Composition in 27 cultivars and changes during ripening. Food Chem. 132, 86–97 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buendía B. et al. HPLC-MS Analysis of Proanthocyanidin Oligomers and Other Phenolics in 15 Strawberry Cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58, 3916–3926 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Bubba M. et al. Liquid chromatographic/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometric study of polyphenolic composition of four cultivars of Fragaria vesca L. berries and their comparative evaluation. J. Mass Spectrom. 47, 1207–1220 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Liu X., Yang T., Slovin J. & Chen P. Profiling polyphenols of two diploid strawberry (Fragaria vesca) inbred lines using UHPLC-HRMSn. Food Chem. 146, 289–298 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia M., Schwab W., Hoffmann T. & Monfort A. Genetic dissection of the (poly)phenol profile of diploid strawberry (Fragaria vesca) fruits using a NIL collection. Plant Sci. 242, 151–168 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosar M., Kafkas E., Paydas S. & Baser K. H. C. Phenolic composition of strawberry genotypes at different saturation stages. J. Agr. Food Chem. 52, 1586–1589 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simirgiotis M. J., Theoduloz C., Caligari, Peter D. S. & Schmeda-Hirschmann G. Comparison of phenolic composition and antioxidant properties of two native Chilean and one domestic strawberry genotypes. Food Chem. 113, 377–385 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Tulipani S. et al. Antioxidants, phenolic compounds, and nutritional quality of different strawberry genotypes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 696–704 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz C. et al. Polyphenol composition in the ripe fruits of Fragaria species and transcriptional analyses of key genes in the pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 12598–12604 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fait A. et al. Reconfiguration of the achene and receptacle metabolic networks during strawberry fruit development. Plant Physiol. 148, 730–750 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesser M. et al. Redirection of flavonoid biosynthesis through the down-regulation of an anthocyanidin glucosyltransferase in ripening strawberry fruit. Plant Physiol. 146, 1528–1539 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheel J. et al. E-cinnamic acid derivatives and phenolics from Chilean strawberry fruits, Fragaria chiloensis ssp. chiloensis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 8512–8518 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatierra A., Pimentel P., Moya-León M. A. & Herrera R. Increased accumulation of anthocyanins in Fragaria chiloensis fruits by transient suppression of FcMYB1 gene. Phytochemistry 90, 25–36 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simirgiotis M. J. & Schmeda-Hirschmann G. Determination of phenolic composition and antioxidant activity in fruits, rhizomes and leaves of the white strawberry (Fragaria chiloensis spp. chiloensis form chiloensis) using HPLC-DAD–ESI-MS and free radical quenching techniques. J. Food Compost. Anal. 23, 545–553 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Deroles S. C. et al. An antisense chalcone synthase cDNA leads to novel colour patterns in lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum) flowers. Mol. Breed. 4, 59–66 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Que Q., Wang H.-Y. & Jorgensen R. A. Distinct patterns of pigment suppression are produced by allelic sense and antisense chalcone synthase transgenes in petunia flowers. Plant J. 13, 401–409 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T., Kalinowski G. & Schwab W. RNAi-induced silencing of gene expression in strawberry fruit (Fragaria × ananassa) by agroinfiltration: a rapid assay for gene function analysis. Plant J. 48, 818–826 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenbein S. et al. Molecular characterization of a stable antisense chalcone synthase phenotype in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa). J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 2145–2153 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C. et al. Acylphloroglucinol biosynthesis in strawberry fruit. Plant Physiol. 169, 1656–1670 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al. Functional characterization of dihydroflavonol-4-reductase in anthocyanin biosynthesis of purple sweet potato underlies the direct evidence of anthocyanins function against abiotic stresses. PloS one 8, e78484 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miosic S. et al. Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase genes encode enzymes with contrasting substrate specificity and show divergent gene expression profiles in Fragaria species. PloS one 9, e112707 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams S. et al. The Arabidopsis TDS4 gene encodes leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase (LDOX) and is essential for proanthocyanidin synthesis and vacuole development. Plant J. 35, 624–636 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotewold E. The Science of Flavonoids (Springer, New York, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z. et al. The tomato Hoffman’s Anthocyaninless gene encodes a bHLH transcription factor involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis that is developmentally regulated and induced by low temperatures. PloS one 11, e0151067 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T. et al. Ectopic expression of snapdragon transcription factors facilitates the identification of genes encoding enzymes of anthocyanin decoration in tomato. Plant J. 83, 686–704 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. et al. Fine mapping and molecular marker development of anthocyanin absent, a seedling morphological marker for the selection of male sterile 10 in tomato. Mol. Breed. 36, 107 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Alfenito M. R. et al. Functional complementation of anthocyanin sequestration in the vacuole by widely divergent glutathione S-transferases. Plant Cell 10, 1135–1149 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S., Shikazono N. & Tanaka A. TRANSPARENT TESTA 19 is involved in the accumulation of both anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 37, 104–114 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs K. A., Alfenito M. R., Lloyd A. M. & Walbot V. A glutathione S-transferase involved in vacuolar transfer encoded by the maize gene Bronze-2. Nature 375, 397–400 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller L. A., Goodman C. D., Silady R. A. & Walbot V. AN9, a petunia glutathione S-transferase required for anthocyanin sequestration, is a flavonoid-binding protein. Plant Physiol. 123, 1561–1570 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn S., Curtin C., Bézier A., Franco C. & Zhang W. Purification, molecular cloning, and characterization of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) from pigmented Vitis vinifera L. cell suspension cultures as putative anthocyanin transport proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 3621–3634 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan A. C., Hellens R. P. & Laing W. A. MYB transcription factors that colour our fruit. Trends Plant Sci. 13, 99–102 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola L. New insights into the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in fruits. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 477–483 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Puche L. et al. MYB10 plays a major role in the regulation of flavonoid/phenylpropanoid metabolism during ripening of Fragaria x ananassa fruits. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 401–417 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni A. et al. The strawberry FaMYB1 transcription factor suppresses anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in transgenic tobacco. Plant J. 28, 319–332 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaart J. G. et al. Identification and characterization of MYB-bHLH-WD40 regulatory complexes controlling proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in strawberry (Fragaria× ananassa) fruits. New Phytol. 197, 454–467 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallarino J. G. et al. Central role of FaGAMYB in the transition of the strawberry receptacle from development to ripening. New Phytol. 208, 482–496 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin-Wang K. et al. Engineering the anthocyanin regulatory complex of strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Front. Plant Sci. 5, 1–14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin-Wang K. et al. An R2R3 MYB transcription factor associated with regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in Rosaceae. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 50 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins C., Caruana J., Schiksnis E. & Liu Z. Genome-scale DNA variant analysis and functional validation of a SNP underlying yellow fruit color in wild strawberry. Sci. Rep. 6, 29017 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Transcript Quantification by RNA-Seq Reveals Differentially Expressed Genes in the Red and Yellow Fruits of Fragaria vesca. PloS one 10, e0144356 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadomura-Ishikawa Y., Miyawaki K., Takahashi A. & Noji S. RNAi-mediated silencing and overexpression of the FaMYB1 gene and its effect on anthocyanin accumulation in strawberry fruit. Biol. Plant 59, 677–685 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Cheynier V., Comte G., Davies K. M., Lattanzio V. & Martens S. Plant phenolics: Recent advances on their biosynthesis, genetics, and ecophysiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 72, 1–20 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbwirth H. et al. Two-Phase Flavonoid Formation in Developing Strawberry (Fragaria× ananassa) Fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 1479–1485 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logemann E., Parniske M. & Hahlbrock K. Modes of expression and common structural features of the complete phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene family in parsley. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5905–5909 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda C. et al. Anthocyanin biosynthetic genes are coordinately expressed during red coloration in apple skin. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 40, 955–962 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S., Ishimaru M., Ding C. K., Yakushiji H. & Goto N. Comparison of UDP-glucose:flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT) gene sequences between white grapes (Vitis vinifera) and their sports with red skin. Plant Sci. 160, 543–550 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y.-Z. et al. Differential Expression of Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Genes in Relation to Anthocyanin Accumulation in the Pericarp of Litchi Chinensis Sonn. PLoS one 6, e19455 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenbein S. et al. Cinnamate metabolism in ripening fruit. Characterization of a UDP-glucose:cinnamate glucosyltransferase from strawberry. Plant Physiol. 140, 1047–1058 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg K. et al. Formation of β-glucogallin, the precursor of ellagic acid in strawberry and raspberry. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 2299–2308 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeduka T. et al. Eugenol and isoeugenol, characteristic aromatic constituents of spices, are biosynthesized via reduction of a coniferyl alcohol ester. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10128–10133 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni A. et al. Gain and loss of fruit flavor compounds produced by wild and cultivated strawberry species. Plant Cell 16, 3110–3131 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni A. et al. Identification of the SAAT gene involved in strawberry flavor biogenesis by use of DNA microarrays. Plant Cell 12, 647–661 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab T. et al. FaQR, required for the biosynthesis of the strawberry flavor compound 4-hydroxy-2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furanone, encodes an enone oxidoreductase. Plant Cell 18, 1023–1037 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillejo C., de la Fuente José Ignacio, Iannetta P., Botella M. Á. & Valpuesta V. Pectin esterase gene family in strawberry fruit: study of FaPE1, a ripening‐specific isoform*. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 909–918 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benítez‐Burraco A. et al. Cloning and characterization of two ripening‐related strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Chandler) pectate lyase genes. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 633–645 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redondo‐Nevado J., Moyano E., Medina‐Escobar N., Caballero J. L. & Muñoz‐Blanco J. A fruit‐specific and developmentally regulated endopolygalacturonase gene from strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Chandler). J. Exp. Bot. 52, 1941–1945 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua C. et al. Antisense down-regulation of the strawberry β-galactosidase gene FaβGal4 increases cell wall galactose levels and reduces fruit softening. J. Exp. Bot. 67, 619–631 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich D. & Olbricht K. Diversity of volatile patterns in sixteen Fragaria vesca L. accessions in comparison to cultivars of Fragaria × ananassa. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual., 37–46 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Giardine B. et al. Galaxy: a platform for interactive large-scale genome analysis. Genome Res. 15, 1451–1455 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J., Nekrutenko A. & Taylor J. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 11, R86 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D. et al. Galaxy: a web-based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 89, 19.10.1–19.10.21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloggett C., Goonasekera N. & Afgan E. BioBlend: automating pipeline analyses within Galaxy and CloudMan. Bioinformatics 29, 1685–1686 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D., Johnson J. E., Taylor J. & Nekrutenko A. Wrangling Galaxy’s reference data. Bioinformatics 30, 1917–1919 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D. et al. Dissemination of scientific software with Galaxy ToolShed. Genome Biol. 15, 403 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Lohse M. & Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen J. A., Govindarajulu R., Ashman T.-L. & Liston A. Evolutionary origins and dynamics of octoploid strawberry subgenomes revealed by dense targeted capture linkage maps. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 3295–3313 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P. T. & Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S. & Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. D., McCarthy D. J. & Smyth G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y. & Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B Met. 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Huber W. et al. Orchestrating high-throughput genomic analysis with Bioconductor. Nat. Methods 12, 115–121 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber W., Heydebreck A., von Sultmann H., Poustka A. & Vingron M. Variance stabilization applied to microarray data calibration and to the quantification of differential expression. Bioinformatics 18, 96–104 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie M. E. et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M. et al. Mercator: a fast and simple web server for genome scale functional annotation of plant sequence data. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 1250–1258 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulaev V. et al. The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Nat. Genet. 43, 109–116 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish O., Shahan R., Liu Z., Slovin J. P. & Alkharouf N. W. Re-annotation of the woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) genome. BMC Genomics 16, 29 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring L. et al. Metabolic interaction between anthocyanin and lignin biosynthesis is associated with peroxidase FaPRX27 in strawberry fruit. Plant Physiol. 163, 43–60 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. A., Want E. J., O’Maille G., Abagyan R. & Siuzdak G. XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal. Chem. 78, 779–787 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautenhahn R., Böttcher C. & Neumann S. Highly sensitive feature detection for high resolution LC/MS. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 504 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton H. P., Want E. J. & Ebbels T. M. D. Correction of mass calibration gaps in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry metabolomics data. Bioinformatics 26, 2488–2489 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 45e–45 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.