Abstract

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is an effective renal replacement therapy, but a significant proportion of patients suffer PD-related complications, which limit the treatment duration. Mesothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (MMT) contributes to the PD-related peritoneal dysfunction. We analyzed the genetic reprograming of MMT to identify new biomarkers that may be tested in PD-patients. Microarray analysis revealed a partial overlapping between MMT induced in vitro and ex vivo in effluent-derived mesothelial cells, and that MMT is mainly a repression process being higher the number of genes that are down-regulated than those that are induced. Cellular morphology and number of altered genes showed that MMT ex vivo could be subdivided into two stages: early/epithelioid and advanced/non-epithelioid. RT-PCR array analysis demonstrated that a number of genes differentially expressed in effluent-derived non-epithelioid cells also showed significant differential expression when comparing standard versus low-GDP PD fluids. Thrombospondin-1 (TSP1), collagen-13 (COL13), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), and gremlin-1 (GREM1) were measured in PD effluents, and except GREM1, showed significant differences between early and advanced stages of MMT, and their expression was associated with a high peritoneal transport status. The results establish a proof of concept about the feasibility of measuring MMT-associated secreted protein levels as potential biomarkers in PD.

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is an effective and cost-efficient alternative to hemodialysis in the treatment of end stage renal disease1, covering approximately 10 to 15% of the dialysis population2. During PD, the peritoneal membrane functions as a semipermeable membrane across which ultrafiltration and diffusion take place3. However, the long-term use of PD is still limited. Nearly 50% of patients are forced to switch to hemodialysis within four to five years of PD treatment, as prolonged exposure to non-physiological PD fluids, with high concentrations of glucose and glucose degradations products (GDPs) and low pH, and peritonitis episodes induce degenerative changes of the peritoneal tissue that ultimately lead to ultrafiltration failure2,4,5,6. Membrane failure is associated with structural alterations of the peritoneum including chronic inflammation, submesothelial fibrosis and angiogenesis7,8. In consequence, one of the most important goals in PD is the preservation of the peritoneal membrane integrity9,10. The use of solutions with neutral pH and with low content of GDPs may represent a potential strategy to attenuate some of the PD-related adverse effects11. The impact of these novels, more biocompatible, solutions on the clinical outcomes is currently being recognized12,13,14,15,16. One possibility to reduce the adverse effects of both classical and novel PD fluids on the peritoneum is by decreasing the dwell time of the dialysate17,18. Another alternative approach to preserve the peritoneal membrane could be the use of pharmacological agents protecting the mesothelium or targeting inflammation and fibrosis7,19.

The structure of the PM is composed of a single layer of highly specialized mesothelial cells (MCs) that lines a compact zone of connective tissue containing few fibroblasts, mast cells, macrophages and vessels20. During long-term PD, MCs undergo a progressive loss of epithelial characteristics and acquire a myofibroblast-like phenotype21. The myofibroblast conversion of the MCs could be observed both in peritoneal tissue biopsies and in ex vivo cultures of MCs obtained from the dialysates. Effluent-derived MCs can be easily isolated from PD-patients using standard methods21,22. It was described that ex vivo cultures of effluent MCs showed two main morphologies: epithelioid and non-epithelioid (fibroblast-like)22. These morphological changes as well as the down-regulation of epithelial molecules (cytokeratin and E-cadherin) and the induction of mesenchymal markers (snail, N-cadherin, fibronectin, collagen I, α-smooth-muscle actin (α-SMA), and fibroblast specific protein-1 (FSP-1)) were described to be indicative of a mesenchymal conversion7,21,22. This so called mesothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (MMT), a special type of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), is a complex and stepwise process that is characterized by the loss of apical-basolateral polarity, disruption of intercellular junctions and acquisition of migratory and invasive properties. MCs that undergo MMT acquire the ability to produce extracellular matrix components, as well as inflammatory, fibrogenic and angiogenic factors7,23,24.

Despite considerable improvements in overall PD technique survival, there is a substantial unmet medical need to identify patients on PD that are at highest risk for membrane failure and to guide these patients to personalized PD regime, peritoneal resting, to hemodialysis or to early transplantation. Previously, several effluent biomarkers, such as CA125 (believed to represent MC mass) and IL-6 (indicating local inflammation), have already been shown to be informative in the follow-up of PD patients at the population level25,26. An alternative individualized approach for the discovery of new biomarkers monitoring peritoneal remodeling is the ex vivo study of effluent-derived MCs. Interestingly, peritoneal transport of the PD patients from whom the cells were harvested was associated with the ex vivo expression levels of molecules that were over-expressed during MMT in cultured effluent MC24,27. As a proof of concept, levels of MMT-associated molecules in the PD effluent, including VEGF, CTGF/CCN2, Gremlin-1 (GREM1), and MMP9 were found to correlate with the peritoneal transport status28,29,30,31,32. Herein, by using whole genome microarray analysis of MCs undergoing MMT in vitro and ex vivo, we aimed to identify novel molecular biomarkers that may facilitate diagnosis of the integrity and functionality of the patient’s peritoneum and hence allow early adaption of treatment to the patient’s needs.

Results

Analysis of gene expression profiles during in vitro and ex vivo MMT

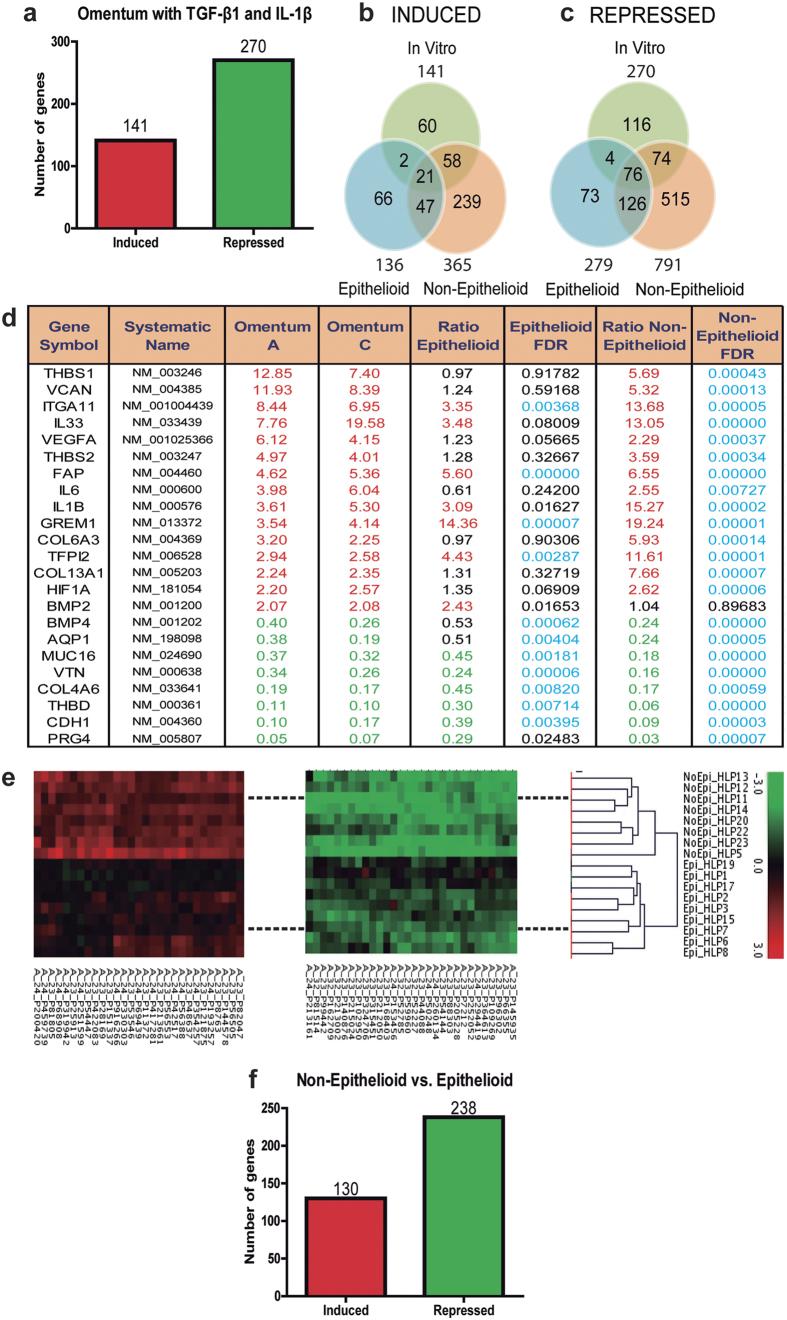

To screen novel biomarkers associated with peritoneal membrane failure, we analyzed the changes of gene expression profile along the MMT process by microarray analysis. It was previously described that the treatment of primary cultures of MCs with TGF-β1, alone or in combinations with proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β or TNF-α21,33,34, induced a myofibroblast conversion reminiscent of a MMT process. Thus, we first analyzed the gene expression changes in omentum-derived MCs induced with TGF-β1 plus IL-1β for 72 hours, and the expression fingerprint of the MMT in vitro was established comprising 141 induced and 270 repressed genes (Fig. 1a, Suppl. Tables S1 and S2).

Figure 1. Microarray analysis.

(a) Number of repressed genes is higher than induced genes in omentum-derived MCs treated with TGF-β1 and IL-1β. Untreated omentum-derived MCs were used as control. (b) Induced and (c) repressed genes in effluent-derived MCs indicate that repressed genes are higher than induced and the differential gene expression is greater in Non-Epithelioid phenotype compared to Epithelioid and partial overlapping was observed between ex vivo and in vitro models. (d) Overlapping genes in in vitro and ex vivo models. MCs from Omentum A and C were treated with TGF-β1 and IL-1β and compared with the untreated omentum-derived MCs. Ratios in Non-Epithelioid and Epithelioid depict the expression change in effluent-derived cells, with a respective FDR associated. In red: induced genes; in green: repressed genes; and in blue: statistically significant results. (e) Gene fingerprint of effluent-derived MCs grouped correctly the samples using cell phenotype by cluster analysis. (f) Number of repressed genes is higher than induce genes when Non-Epithelioid phenotype was compared with Epithelioid phenotype.

We next compared the gene expression profiles of omentum-derived MCs and 17 samples of effluent-derived MCs, subdivided into epithelioid (E, n = 9) or non-epithelioid (NE, n = 8) phenotypes. A pull of RNAs obtained from four omental specimens was used as the reference control. The global microarray analysis showed a progressive reprogramming along the ex vivo MMT process, being higher the number of changed genes in cells with NE phenotype (induced genes: 136 in E vs 365 in NE; repressed genes: 279 in E vs 791 in NE). Of these altered genes, 68 and 202 were induced or repressed in the two groups (Fig. 1b and c, see list of genes in Suppl. Tables S3–S6). Interestingly, the fingerprint of the MMT in vitro overlapped only partially with the expression profiles of MMT ex vivo (Fig. 1b–d) suggesting that MMT in vitro is a similar but not identical process as MMT ex vivo. However, this partial overlap may be considered a cross-validation of genes that change their expression during MMT independently of the stimuli triggering this process. It is worth noting, that the genetic reprogramming during MMT, in vitro and ex vivo, is predominantly based on a gene repression. Expression data for each gene within each sample was used to create a heatmap for cluster classification, which revealed a clear separation between E and NE phenotypes (Fig. 1e), indicating that the subdivision of effluent MCs according to their elliptical factor was properly done. It was previously shown that high peritoneal transport was associated with the presence of MCs with NE phenotype in the PD effluent and with up-regulated expression ex vivo of MMT-related molecules24,27. In this context, this microarray analysis identified a number of genes (130 induced and 238 repressed) that were differentially regulated in NE cells when compared with E cells (Fig. 1f, Suppl. Tables S7 and S8), which opens new opportunities for the identification of biomarkers in PD.

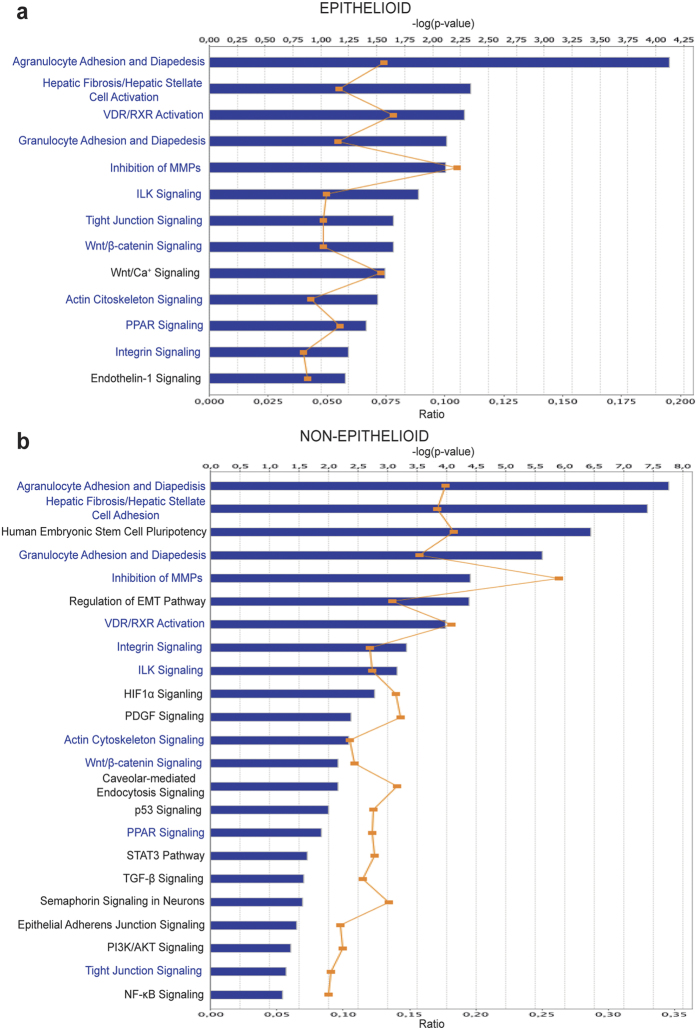

Agilent ID of differentially expressed genes in effluent cells with E and NE phenotypes were submitted to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis® (IPA) for mapping to canonical pathways and identification of upstream regulators. The analysis revealed again a progressive reprogramming along the ex vivo MMT, the number of altered pathways was higher in cells with NE phenotype (52 in E vs 105 in NE) and there was an overlapping of 31 pathways that were deregulated in both groups (Suppl. Tables S9 and S10). Among the canonical pathways that were significantly differentially regulated, many were related to key processes involved in MMT/EMT, including integrin/ILK, intercellular junction, NF-κB, HIF-1α, Wnt/β-catenin, Endothelin-1 (ET-1) and TGF-β signaling pathways (Fig. 2). Pathways endowing MCs with stemness and plasticity were also differentially regulated in cells with E and NE phenotypes, which is in line with recent reports showing that during liver development, MCs act as progenitor cells that produce hepatic stellate cells, fibroblasts around blood vessels, and smooth muscle cells. In addition, during liver injury, MCs migrate inward from the liver surface and produce hepatic stellate cells or myofibroblast depending on the etiology35,36,37. It was also noteworthy that the ET-1 signaling pathway was specifically deregulated in MCs with E phenotype, whereas TGF-β signaling was differentially regulated only in NE cells. This is in agreement with previous data that demonstrated a role for an ET-1/TGF-β axis in the control of the MMT process, in which TGF-β, responsible for the progression and maintaining of the mesenchymal stage, appeared to be downstream of ET-1-mediated signaling38.

Figure 2. Functional analysis of relevant pathways in (a) Epithelioid and (b) Non-Epithelioid phenotypes.

Although many pathways are common in both phenotypes, others are dependent of Epithelioid or Non-Epithelioid state, indicating a differential expression in pathways during MMT process. Blue: common pathways. Bold: pathways exclusive of Epithelioid or Non-Epithelioid phenotype. Ratio is the number of molecules in a given pathway that meet cutoff criteria, divided by total number of molecules that make up that pathway and that are in the reference set. Selected genes for further analysis in this work are implicated in these pathways (Suppl. Tables S9 and S10).

As expected, the number of upstream regulators was higher in MCs with NE phenotype than in E cells (Table 1). Interestingly, both cell types, E and NE, showed inhibition of E-cadherin (CDH1) as an upstream regulator. It is well known that the disruption of adherent junctions is an early step and one of the key events in MMT23. In this context, it has been reported that MMT and peritoneal membrane injury are mediated through cleavage of E-cadherin by MMP-9 and induction of β-catenin signaling32. Interestingly, we observed that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway was deregulated in both E and NE cells (Fig. 2). Among the activated upstream regulators in NE cells, we found several inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes (IL-1B, IL-1A, FGF2, SNAI1 and TGFB2) that are known master molecules in the control of MMT (Table 1). It drew our attention that in MCs with E phenotype the only activated upstream regulator was Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) (Table 1), suggesting that this nuclear receptor plays a modulatory roll in the early steps of MMT39,40,41. Taken together these data clearly indicated that the genetic fingerprints of effluent-derived MCs discriminated between two stages of MMT: early MMT (E phenotype) and advanced MMT (NE phenotype).

Table 1. Upstream Regulators.

| Cell Phenotype | Upstream Regulator | Exp Fold Change | Molecule Type | Predicted Activation State | Activation z-score | p-value of overlap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epithelioid | PPARG | 2.32 | ligand-dependent nuclear receptor | Activated | 2.69 | 6.86E-04 |

| CDH1 | −2.54 | other | Inhibited | −1.59 | 1.25E-02 | |

| Non-Epithelioid | IL1B | 15.27 | cytokine | Activated | 2.95 | 7.79E-30 |

| MMP3 | 9.08 | peptidase | Activated | 2.19 | 4.47E-01 | |

| F2R | 4.46 | g-protein coupled receptor | Activated | 2.78 | 6.05E-06 | |

| PTGS2 | 4.03 | enzyme | Activated | 3.01 | 1.23E-09 | |

| SPP1 | 3.57 | cytokine | Activated | 3.40 | 3.72E-07 | |

| ITGA2 | 3.08 | transmembrane receptor | Activated | 2.43 | 6.28E-04 | |

| FGF2 | 2.93 | growth factor | Activated | 2.64 | 4.55E-19 | |

| IL1A | 2.73 | cytokine | Activated | 4.73 | 1.02E-10 | |

| ADORA2B | 2.57 | g-protein coupled receptor | Activated | 2.34 | 5.42E-05 | |

| NRIP1 | 2.53 | transcription regulator | Activated | 2.38 | 4.39E-03 | |

| SNAI1 | 2.41 | transcription regulator | Activated | 2.25 | 3.92E-07 | |

| TGFB2 | 2.23 | growth factor | Activated | 2.09 | 5.88E-08 | |

| HMGB1 | 2.01 | transcription regulator | Activated | 3.08 | 5.35E-03 | |

| WNT4 | −4.56 | cytokine | Inhibited | −2 | 1.03E-04 | |

| GHR | −2.11 | transmembrane receptor | Inhibited | −2.19 | 1.47E-02 | |

| CDH1 | −11.24 | other | Inhibited | −2.87 | 1.43E-07 |

Table columns (left to right): Cell phenotype; Upstream regulator genes; Gene’s fold change determined in microarray analysis; Molecule type; Predicted activation state of upstream regulator; Z-score: if z-score ≥ 2 then upstream regulator is activated, and if z-score ≤ −2 then is inhibited; p-value, calculated by Fisher’s Exact Test, indicates the statistical significance of genes in the data set that are downstream of de upstream regulator. Normal letter: up-regulated genes; bold: down-regulated genes in microarrays.

Forty of the top deregulated genes in NE cells from the microarray studies were validated by quantitative RT-PCR analysis (Table 2). In addition, we could demonstrate that a number of these genes were differentially regulated in NE cells when compared with E cells (Suppl. Table S11). It is important to point out that GREM1, a key molecule implicated in EMT in general and MMT in particular31,42 was further upregulated in NE cells when compared with E cells but the difference between both did not reach statistical significance. This result was in agreement with the microarray studies that showed a similar behavior of GREM1 expression (Suppl. Tables S3 and S5). The early up-regulation of GREM1 suggested that this molecule could act as a master regulator of the MMT process.

Table 2. Microarray validation by PCR-Array.

| GENE | Non-Epithelioid |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fold change | p-value | FDR | |

| GREM1 | 7.82 | <0.001 | |

| IL1B | 27.70 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| KRT34 | 37.36 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CDH13 | 65.76 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| THBS1 | 25.87 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| COL6A3 | 43.34 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MMP1 | 16.81 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| COL13A1 | 7.71 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| IL6 | 2.52 | 0.015 | 0.017 |

| FSP1 | 11.32 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| TFPI2 | 26.61 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CAV1 | 4.51 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VCAN | 4.94 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| IL33 | 8.08 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ITGA11 | 7.26 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| THBS2 | 3.93 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MMP3 | 10.50 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| SNAI1 | 3.65 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| COL1A2 | 2.12 | 0.021 | 0.024 |

| CD44 | 8.41 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| MMP2 | 4.28 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| FAP | 3.04 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CTSK | 2.94 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CLDN1 | 0.32 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| COL4A6 | 0.43 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| WT1 | 0.36 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HSPB8 | 0.48 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| ITGB4 | 0.38 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AQP1 | 0.19 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VTN | 0.20 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BMP4 | 0.21 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CDH3 | 0.28 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HSPA2 | 0.42 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| KDR | 0.21 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CDH1 | 0.08 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LAMA5 | 0.24 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CXCL14 | 0.19 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BMP7 | 0.07 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| THBD | 0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| PRG4 | 0.06 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

A total of 40 genes, 22 induced and 18 repressed, were selected from Non-Epithelioid group in microarray and validated by RT-qPCR. Fold change, p-value (One-sample Limma test) and associated FDR multiple testing correction are show. Normal letter: up-regulated genes; bold: down-regulated genes in microarrays.

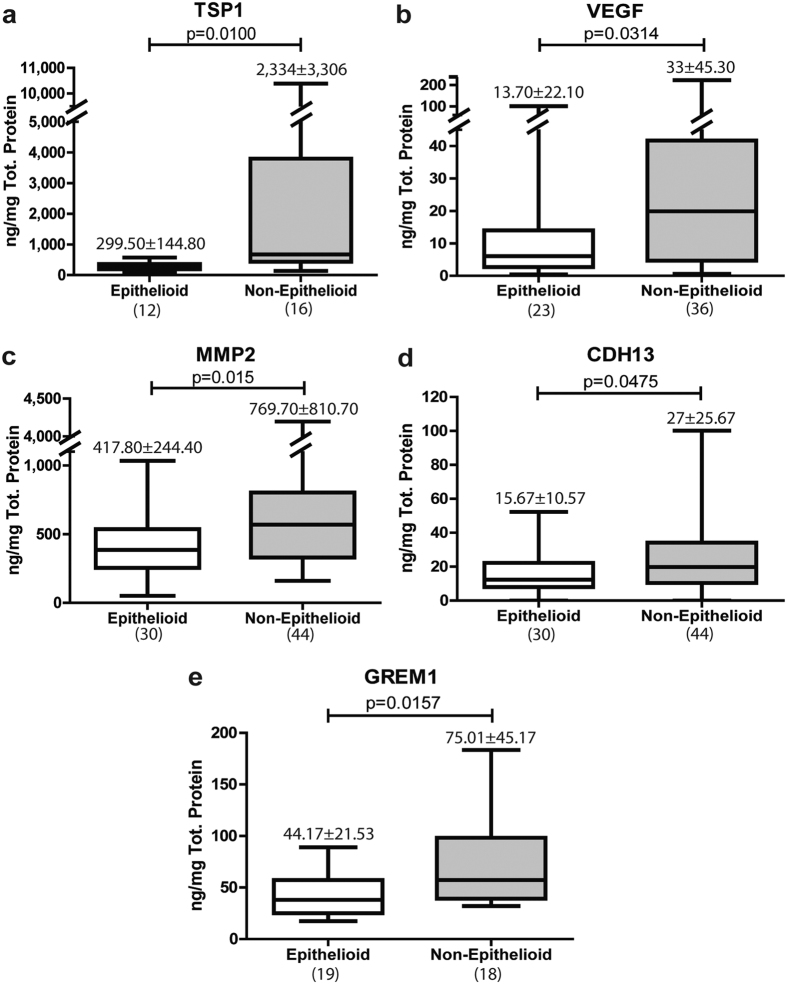

To validate the study in terms of protein expression, we measured the levels of TSP1, MMP2, CDH13 and GREM1 by ELISA in the culture supernatant of effluent-derived MCs, which were grouped in E and NE phenotypes. VEGF was included as an internal control as we have previously shown the up-regulation of this angiogenic factor along the MMT process27,43. As shown in Fig. 3, all these MMT-associated proteins, including GREM1, significantly augmented in the culture supernatant of NE cells when compared with MCs bearing E phenotype.

Figure 3. Proteins in supernatants.

(a) TSP1, (b) VEGF, (c) MMP2, (d) CDH13 and (e) GREM1 were measured in culture supernatants of effluent-derived MCs obtained from PD patients. Protein levels were higher in Non-Epithelioid phenotype in these cases. Number on top box-plot represents the mean ± standard deviation. Number in parentheses represents the N of each group. Results were significant with p < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney test).

MMT-associated transcripts discriminate between low-GDPs and high-GDPs PD fluids

We could observe that the prevalence of NE phenotype of MCs tended to be higher in the effluents of PD patients treated with high-GDPs fluids than in patients treated with low-GDPs fluids (Suppl. Table S12). Thus, as a first approach to assess the clinical value of the MMT-associated markers, a subset of 14 genes was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR in 51 samples of effluent MCs from PD patients treated either with low-GDPs (n = 28) or high-GDPs (n = 23) fluids. As expected, all these genes, except for GREM1, showed significant differences or tendencies between E and NE phenotypes (Table 3). Interestingly, most of these genes showed significant differences (CDH13, COL6A3, COL13A1, KRT34, THBS1 and VEGFA) or a tendency (MMP1 and CDH1) between low-GPDs and high-GDPs fluids (Table 3). However, other genes (KDR, THBD, TFPI2) in spite of showing differences or tendencies between E and NE phenotypes did not appear to be associated with the type of PD fluid (Table 3). Again, GREM1 did not show differences between low-GDPs and high-GDPs fluids.

Table 3. mRNA of patients.

| GEN | Epithelioid (N = 23) | Non-Epithelioid (N = 28) | p value | FDR | Low-GDP (N = 28) | High-GDP (N = 23) | p value | FDR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| GREM1 | 4.03 | 4.14 | 7.61 | 11.97 | 0.798 | 0.798 | 5.45 | 9.19 | 6.66 | 9.80 | 0.977 | 0.977 |

| CD44 | 2.88 | 2.94 | 4.87 | 3.34 | 0.001 | 0.011 | 3.53 | 2.94 | 4.51 | 3.66 | 0.135 | 0.185 |

| CDH13 | 15.07 | 13.96 | 26.16 | 23.03 | 0.049 | 0.062 | 12.39 | 8.67 | 31.84 | 24.64 | 0.003 | 0.016 |

| COL6A3 | 8.80 | 10.07 | 18.03 | 20.91 | 0.020 | 0.038 | 8.06 | 8.19 | 20.93 | 22.57 | 0.006 | 0.016 |

| COL13A1 | 1.39 | 1.34 | 3.16 | 3.54 | 0.016 | 0.038 | 1.37 | 1.27 | 3.57 | 3.77 | 0.006 | 0.016 |

| KRT34 | 7.59 | 8.23 | 27.21 | 33.15 | 0.012 | 0.038 | 8.73 | 10.64 | 30.08 | 35.17 | 0.010 | 0.020 |

| MMP1 | 1.37 | 1.25 | 6.73 | 9.83 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 4.27 | 9.49 | 4.36 | 5.12 | 0.066 | 0.114 |

| MMP2 | 3.97 | 3.90 | 4.64 | 3.27 | 0.116 | 0.125 | 3.61 | 3.02 | 5.23 | 3.98 | 0.096 | 0.149 |

| TFPI2 | 5.80 | 5.35 | 10.57 | 9.91 | 0.016 | 0.038 | 8.42 | 6.66 | 8.42 | 10.38 | 0.691 | 0.798 |

| THBS1 | 7.36 | 8.54 | 19.41 | 24.98 | 0.022 | 0.038 | 5.78 | 5.31 | 23.96 | 26.41 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| VEGFA | 1.84 | 1.32 | 3.32 | 3.29 | 0.088 | 0.105 | 1.90 | 1.85 | 3.57 | 3.24 | 0.007 | 0.016 |

| CDH1 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.061 | 0.016 |

| KDR | 0.87 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.041 | 0.062 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.325 | 0.408 |

| THBD | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.047 | 0.062 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 1.000 | 0.977 |

A total of 14 genes, 11 induced and 3 repressed in microarray studies, were analyzed in 51 samples of effluent-derived MCs in PD patients. Genes grouped by cell phenotype: A statistically significant difference (or tendency to significance) was observed in 12 mRNAs. Induced genes were higher in Non-Epithelioid phenotype, whilst in repressed genes were higher in Epithelioid phenotype. Genes grouped by content of GDPs in Peritoneal Dialysis Fluid: 8 mRNAs showed significant difference (or tendency) between low-GDP and high-GDP fluids. Normal letter: up-regulated genes; bold: down-regulated genes. Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare between groups and corrected with multiple testing FDR. Statistically significant differences are marked in bold.

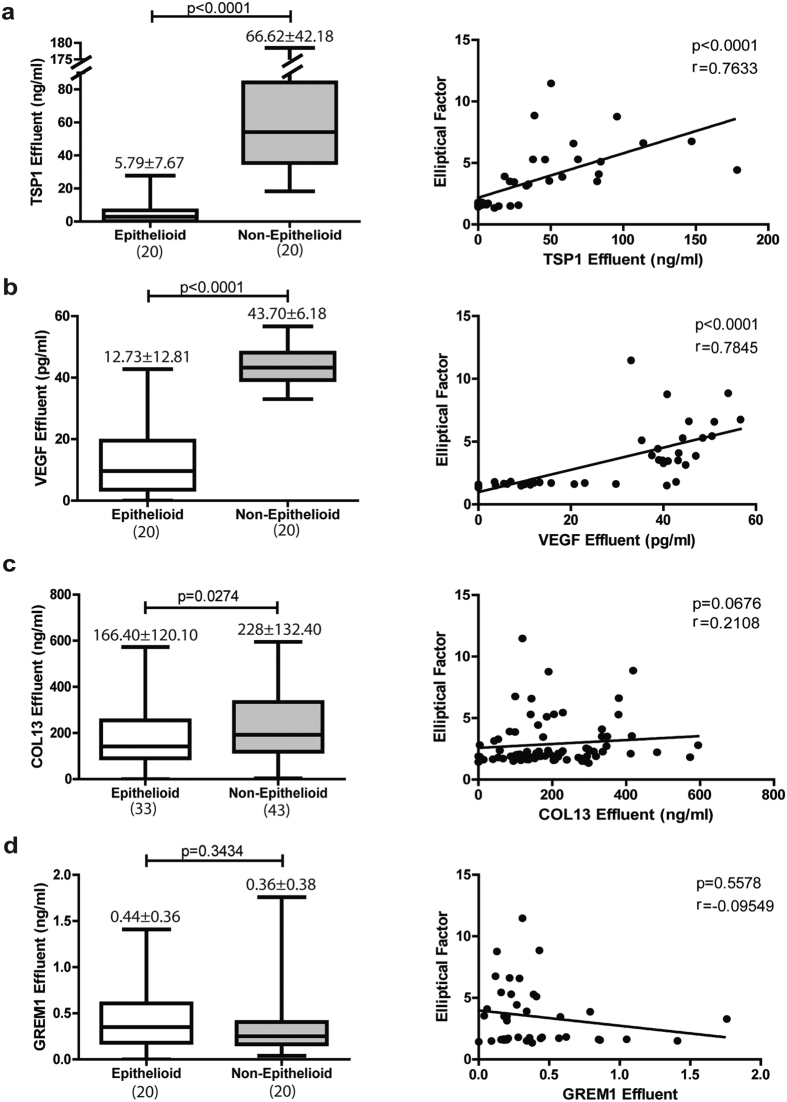

Effluent protein levels of TSP1, VEGFA and COL13 are biomarkers for membrane functional decline

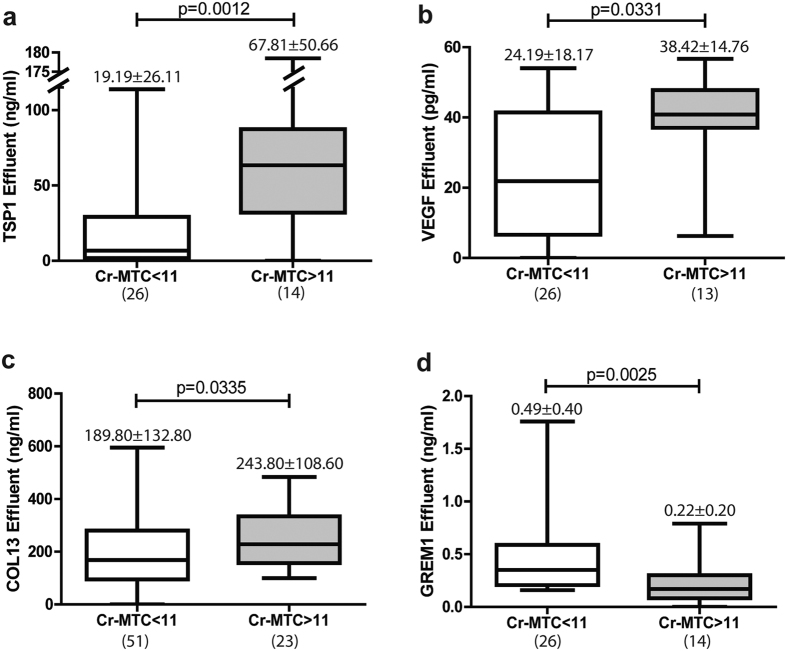

Among the secreted proteins that are up-regulated during MMT in vitro and ex vivo, thrombospondin-1 (TSP1), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), collagen-13 (COL13), and gremlin-1 (GREM1) were selected to be measured in PD effluents. TSP1 and VEGFA levels had marked differences between early (E phenotype) and advanced (NE phenotype) stages of MMT and correlated with the elliptical factor values of effluent-derived MCs (Fig. 4a and b). Effluent levels of COL13 showed significant differences between E and NE phenotypes, but did not reach statistical significance in the correlation with elliptical factor (Fig. 4c). Effluent levels of GREM1 did not show any association with MC phenotype, in agreement with the microarray and RT-PCR studies (Fig. 4d). When PD patients were subdivided into 2 groups according to peritoneal transport characteristics: low/low-average transporters (Cr-MTC < 11 mL/min) and high/high-average transporters (Cr-MTC > 11 mL/min), significantly greater effluent TSP1, VEGF and COL13 concentrations were observed in the last group (Fig. 5a–c). Surprisingly, effluent levels of GREM1 also showed statistical differences between low/low-average and high/high-average transporters, but in the opposite direction to what could be expected with respect to microarray and RT-PCR studies and according to previous reports31 (Fig. 5d). It is tempting to speculate that the higher levels of GREM1 in patients with a preserved peritoneal function could be due to a concomitant preservation of the mesothelium.

Figure 4. Proteins in effluents by Elliptical Factor.

(a) TSP1, (b) VEGF, (c) COL13 and (d) GREM1 were measured in effluents. Left panels represent level of proteins grouped by cell phenotype and right show correlations between protein in effluent and Elliptical Factor. Number on top box-plot represents the mean ± standard deviation. Whiskers in box-plot represent maximum and minimum values. Number in parentheses represents the N of each group. Results were significant with p < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney test and Spearman correlation).

Figure 5. Proteins in effluents by membrane transport.

(a) TSP1, (b) VEGF, (c) COL13 and (d) GREM1 were measured in effluents. Cr-MTC: Mass Transfer Coefficient of Creatinine (mL/min). Number on top box-plot represents the mean ± standard deviation. Whiskers in box-plot represent maximum and minimum values. Number in parentheses represents the N of each group. Results were significant with p < 0.05 (Mann-Whitney test).

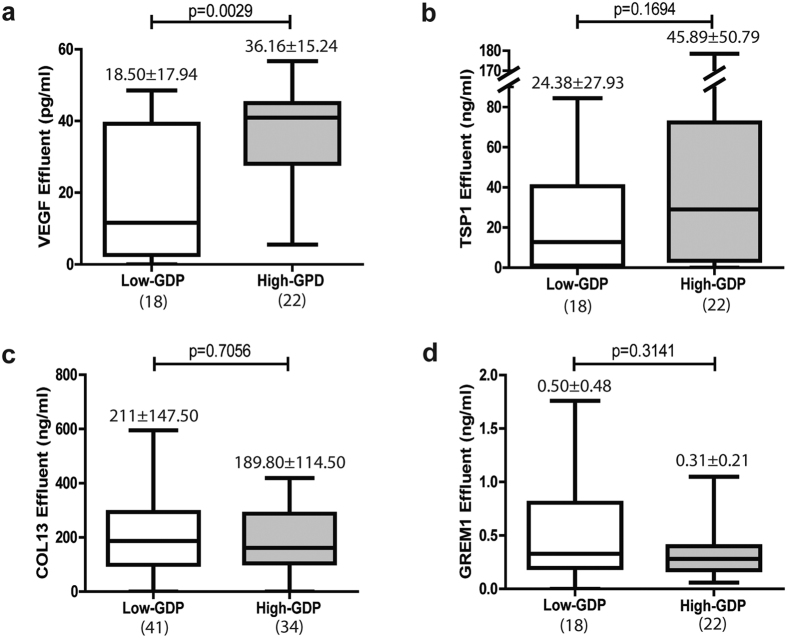

Effluent VEGF concentration showed significant difference between low-GDPs and high-GDPs fluids (Fig. 6a), whereas TSP1 levels were increased in patients treated with high-GDPs fluids, compared to those treated with low-GDPs fluids, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 6b). In contrast, effluent COL13 did not show differences between both types of fluids (Fig. 6c), which was in sharp contrast with the data obtained in the RT-PCR studies (Table 3). These results suggested that mesenchymal MCs were not the only local source of COL13 during PD-induced peritoneal damage. Again, GREM1 did not show differences between low-GDPs and high-GDPs fluids (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6. Proteins in effluents by low-GDPs or high-GDPs of Peritoneal Dialysis Fluid.

(a) VEGF, (b) TSP1, (c) COL13 and (d) GREM1. Number on top box-plot represents the mean ± standard deviation. Whiskers in box-plot represent maximum and minimum values. Number in parentheses represents the N of each group. Only (a) VEGF in effluents was significant between low-GDPs and high-GDPs fluids (Mann-Whitney test p-value < 0.05).

Discussion

Assessment of the progressive peritoneal morphological alterations during PD would require repetitive biopsies, which is not feasible in the clinical routine except during removal of the peritoneal catheter, during kidney transplantation or another laparotomy14,44,45. In addition to a sort of a routine measurement to monitor the peritoneal status for being able to timely intervene and adapt to PD regimen, PD therapy has a substantial need for early biomarkers as a tool to identify patients that are at highest risk for PD-related complications and to guide personalized interventions that may improve clinical outcome in the individual patient. Biomarkers are usually determined in plasma or serum and sometimes in urine. PD offers the unique possibility to investigate peritoneal effluent. PD effluent represents a particularly attractive material for biomarker research as it contains cells and biomolecules that are indicative of the peritoneal transport status as well as of peritoneal health, ongoing pathological processes and even the status of underlying disease and comorbidities of the individual PD patient. It has been proposed that and ideal effluent biomarker for PD should encompass the following properties: 1.- Detectable in peritoneal effluent. 2.- Local release/production within the peritoneal cavity. 3.- Involved in pathology of the peritoneal membrane. 4.- High sensitivity and specificity for the clinical outcome of interest. The research of effluent biomarkers in PD has predominantly been hypothesis-driven and based on patho-mechanisms found to be relevant for the course of disease in PD, such as chronic inflammation and peritoneal membrane remodeling. However, at present the integration of effluent biomarkers into clinical decision making in PD is only modest46.

In this study, we hypothesized that MMT is a central process implicated in PD-induced morphological and functional changes of peritoneal membrane and we analyzed and validated, for the first time, the whole genomic reprograming during MMT, in vitro and ex vivo, with the aim to identify novel biomarkers to be tested in PD-patients. These analyses showed that the number of repressed genes is higher than the number of induced genes, in both ex vivo and in vitro models, indicating that MMT is primarily a repression process. The analysis also revealed a progressive genetic reprogramming along the MMT ex vivo, and discriminated between two stages of MMT in effluent-derived MCs: early MMT (E phenotype) and advanced MMT (NE phenotype). It is generally accepted that the treatment of omentum-derived MCs with TGF-β1, alone or in combination, is a good model of MMT in vitro that mimics the mesenchymal conversion of MCs taking place in the peritoneum of PD patients7,21,22. However, the fingerprint of the MMT in vitro overlapped only partially with the expression profiles of MMT ex vivo. It is worthwhile to point out that MMT may result from an integration of diverse signals triggered by multiple factors operating in vivo, being difficult to assign priorities or hierarchies. Thus, the results obtained in cell culture experiments using one or two stimuli only should be interpreted with caution. However, the partial overlapping between in vitro and ex vivo MMT is valuable for cross-validation of altered genes during the mesenchymal conversion of MCs and may help for the selection of candidate genes as potential biomarkers.

We have previously shown that MCs from effluents with NE phenotype produced higher levels of COX-2 and VEGF than MCs with E phenotype. The levels of ex vivo expression of these molecules correlated with the mass transfer area coefficient for creatinine (Cr-MTAC) of PD patients24,27. Another study demonstrated that high peritoneal transport state was associated with increased CTGF/CCN2 mRNA synthesis by effluent MCs30. Recently, it has been described that the level of expression of MMP-9-encoding mRNA by effluent MCs correlated with solute transport data, including dialysate to plasma creatinine ratio (D/P creatinine) and a 4 h to initial PD fluid glucose ratio (D/D0 glucose)32. Herein, we demonstrate by RT-PCR array that a subset of genes differentially expressed in effluent-derived NE cells also show differential expression when comparing low-GDPs versus high-GDPs PD fluids. This result is in agreement with previous studies showing that PD fluids with low content of GDPs have less impact in vivo and ex vivo on MMT than standard non-physiological fluids14,47,48. Taken together, these studies clearly suggest that the acquisition of mesenchymal properties by MCs might be involved in the progression of peritoneal structural alteration and in high transport state, being, therefore, feasible to focus on MMT process ex vivo for the search of novel biomarkers in PD.

However, it is no always feasible to employ the ex vivo culture of effluent MCs in the regular clinical practice. An alternative approach is the use of the dialysate as a form of “liquid biopsy” in which MMT-associated molecules could be measured directly. As a proof of concept, in this study we have selected three secreted proteins that are up-regulated during MMT (thrombospondin-1; TSP1; collagen-13, COL13; and gremlin-1, GREM1) to be measured in PD effluents. Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) was also included as a control since it was previously demonstrated that the levels of this growth factor in ex vivo MCs cultures and in PD effluents correlate with the peritoneal transport status and are associated with PD fluid biocompatibility27,28,29,48. Effluent levels of TSP1, COL13 and VEGFA levels showed significant differences when comparing patients draining MCs with either early or advanced stages of MMT. In addition, the effluent levels of TSP1, COL13 and VEGFA were clearly associated with high peritoneal transport status (Cr-MTC > 11 mL/min). As expected from the microarray and RT-PCR studies, effluent levels of GREM1 did not show any association with MC phenotype. It is important to point out that GREM1, a key molecule implicated in EMT in general and MMT in particular31,42 is rapidly up-regulated in effluent-derived MCs, being highly expressed even in early stages of MMT and further augmented in MCs with NE phenotype. Thus, the early up-regulation of GREM1 suggested that this molecule could act as a master regulator of the MMT process. Surprisingly, however, effluent levels of GREM1 were higher in low/low-average than in high/high-average transporters. These results were in sharp contrast with previous reports31 and we do not have a definitive explanation for these apparent discrepancies. However, it can be speculated that the higher levels of GREM1 in patients with a preserved peritoneal function could be due to a concomitant preservation of the mesothelial mass. Thus, the ratio between effluent GREM1 and CA125 could represent better the intraperitoneal production of GREM1 per unit mass of MCs and would require further studies49.

Of the four selected MMT-related markers, effluent concentrations of TSP1 and VEGFA were associated with dialysis regime (low-GDPs or high-GDPs fluids), whereas effluent COL13, in contrast with the data obtained in the RT-PCR studies, did not show differences between both types of fluids. The weaker correlation of effluent COL13, when compared with TSP1 and VEGFA, with MC phenotypes and peritoneal transport states, and its lack of association with the GDPs content of the fluids suggest that MCs undergoing MMT is not the only source of COL13 during PD-induced peritoneal damage50. To reinforce this idea, we could demonstrate that the levels of effluent TSP1 and VEGF, but not of COL13, correlated with the expression of their respective mRNAs by MCs cultured ex vivo (Data not shown).

One of the properties for an ideal effluent biomarker is that it must be involved in the pathology of the peritoneal membrane. It is well known that VEGF, which is strongly induced in MCs undergoing MMT during PD, is a key regulator of angiogenesis and its role in peritoneal transport alteration is widely recognized27,28,29,48. Conversely, TSP1 has anti-angiogenic properties that are mediated by direct interaction with VEGF and/or by inhibition of MMP9 with the consequent retention of VEGF trapped in ECM51. It has been also shown that binding of TSP1 to its receptor CD36 can block the transduction of the VEGF signal through VEGF Receptor 2 (VEGFR2)51. In addition, TSP1 is an activator of latent TGF-β152, a master molecule controlling MMT53. Thus, during MMT, TSP1 is overexpressed and latent TGF-β1 is activated, further enhancing the MMT process and increasing the synthesis of VEGF, which promotes angiogenesis and peritoneal transport alteration.

Little information is available on the expression of type XIII collagen (COL13) in human diseases. COL13 is a type II trans-membrane protein, with a short intracellular domain and a long extracellular domain that is released by furin proteases and can be incorporated to extracellular matrix54. These two forms, trans-membrane and shed protein, have different biological functions and bind the ECM component fibronectin, which is strongly induced during MMT in PD, Nidogen-2, Perlecan or α1β1 integrin50,54,55. It has been demonstrated that factors secreted by tumor cells, in particular TGF-β1, contribute to the induction of COL13 expression by fibroblasts, and that this collagen expression may conversely contribute to tumor progression by modulating cell-matrix interactions55.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that measurement of MMT-associated molecules in PD effluents may have clinical value as biomarkers in order to personalize PD treatment and to improve the outcome of PD patients. The next goal would be to develop a combination of MMT-related molecules that can be measured in the PD effluent at once (MMT-Chip) and offer diagnostic value. Finally, well-designed clinical trials are required to prospectively test the proof of concept and clinically confirm the usefulness of the candidate biomarker in independent cohorts.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of mesothelial cells

The protocol and informed consent were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Clinic Investigation of the Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa” ref: 2010-0009 (Madrid, Spain) and “Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda”, record number 300 (Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain). Informed written consent was obtained from all PD patients and omentum donors prior to the initiation of any study-related activities. This study abides by the Declaration of Helsinki and the research was carried out in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guideline and applicable regulation.

MCs were obtained from omentum taken from patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery as well as from the effluents of PD patients as previously described22. Cells were cultured in Earle’s M199 medium (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Scientific, Cramligton, UK), 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin (PPA Laboratories GmbH, Pasching, Austria), 2% Biogro-2 (Biological Industries). The purity of the isolated omentum- and effluent-derived MCs was verified by the expression of the standard mesothelial markers intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, calretinin and cytokeratins22. All cells were negative for the endothelial marker von-Willebrand factor22, and passed through CD45-specific columns (CD45 MicroBeads; Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) to eliminate any possible contamination by macrophages56.

MCs were classified into epithelioid (E) or non-epithelioid (NE) phenotype according the Elliptical Factor (EF) which represents the relation between the major and the minor cell axis57. The dimensions of ten cells, randomly chosen in each culture, were measured using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). If the calculated EF ratio was greater than or equal 2, meaning that the cell is twice as long as it is wide, the culture was classified like NE phenotype and, in case the ratio was smaller than 2, it was categorized to have an E phenotype.

Whole Genome RNA Microarray Analysis

All microarray data were up-loaded in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (www.ncbi.nlm.nig.gov/geo) with reference number GSE92455.

Ex vivo

For ex vivo RNA microarray analysis, 17 MC samples derived from 16 PD patient’s effluents were cultured and analyzed as described above: 9 populations showed an E phenotype and 8 samples were classified as NE. Four omentum-derived MC samples were taken as controls. As there were no significant differences in their transcriptional patterns, these control cells were pooled for future experiments. Cell lysis and RNA extraction using TRI Reagent® Solution (Ambion, Austin, Texas, USA) was done according to the manufacturer´s instructions. A dye-swap design was used in these experiments, one hybridization sample was labeled in red and the control in green, whereas the other hybridization sample was labeled in green and the control in red, using the Quick Amp Labeling Kit, two-color (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). RNA microarray analysis was carried out using the Whole Human Genome Microarrays Kit 4 × 44 K (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions: 825 ng of cRNA (Cy3-cRNA and Cy5-cRNA) were incubated with blocking agent and fragmentation buffer, 30 minutes, 60 °C. Hybridization buffer was added and hybridization was performed at 65 °C, 17 hours in darkness, stirring at 10 rpm. Finally, slides were introduced in different stringencies buffered saline and in the stabilization solution and drying indicated by Agilent Technologies. Arrays were scanned on the Agilent Technologies G2505B Micro Array Scanner at 5 nm resolution.

In vitro

To analyze the gene expression in artificially induced MMT, half of the total cells obtained from omentum-derived MC samples were treated with 0.5 ng/ml human recombinant TGF-β1 and 2 ng/ml IL-1β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) for 72 h, while the other half was untreated and used as control. RNA extraction and microarray analysis was carried out as described above.

Microarray data processing and gene expression analysis

The processing and normalization was performed using the Babelomics (http://babelomics.bioinfo.cipf.es) software58. Fluorescence raw signal from each probe was corrected with the subtraction of local background and normalized with the loess method (within arrays) or the quantile method (between arrays). Fold change for a gene was determined as a quotient between normalized data from samples under study. Statistics for differential expression was obtained with Limma One Class or Limma Two Class test and corrected for multiple-test with FDR (False Discovery Rate; Benjamini & Hochberg). Genes with fold change ≥ 2 or ≤0.5, and FDR ≤ 0.01, were considered induced or repressed, respectively. Clustering was made by TIGR MeV59 v4 software using Euclidian Distance and Average Linkage Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software (Qiagen; www.ingenuity.com) was used for determination of Canonical Pathways and Upstream Regulators analysis.

RT-qPCR microarray data validation

To validate the results obtained by microarray analysis, 7 samples used in the microarray studies (3 with E and 4 with NE phenotype), 11 samples previously not included in the microarrays (2 with E and 9 with NE phenotype) and the control omentum pool (pool of 4 samples) were analyzed by RT-qPCR. For this, RealTime Ready Custom Panel Plates (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany) were used, and probes and primers were designed using the RealTime Ready Configurator tool (https://configurator.realtimeready.roche.com/assaysupply_cp/login.jsf, Roche Applied Science). 40 genes were validated: AQP1, BMP4, BMP7, CAV1, CD44, CDH1, CDH3, CDH13, CLDN1, COL1A2, COL4A6, COL6A3, COL13A1, CTSK, CXCL14, FAP, FSP1, HSPA2, HSPB8, IL1B, IL6, IL33, ITGA11, ITGB4, KDR, KRT34, LAMA5, MMP1, MMP2, MMP3, PRG4, SNAI1, TFPI2, THBD, THBS1, THBS2, VCAN, VTN and WT1.

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, Maryland, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA synthesis was done using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche Applied Science); program as follows: 25 °C, 10 minutes; 55 °C, 30 minutes; 85 °C, 5 minutes; 4 °C. RT-qPCR was conducted using the LightCycler® 480 with SYBR Green system (Roche Applied Science) with the following program: 95 °C, 10 minutes; 45 cycles of 95 °C, 10 seconds; 60 °C, 30 seconds; 72 °C, 1 second; 4 °C. Data normalized to the housekeeping gene TBP were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

For GREM1 validation, the TaqMan® Assay System (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, California, USA) was used. Oligos for GREM1 (Hs00171951_m1; Applied Biosystems and 18 S (5’ATCCATTGGAGGGCAAGTC3’ and 5’GCTCCCAAGATCCAACTACG3)’; Roche Applied Science) and TaqMan® FAM™ dye (Applied Biosystems) were used. RT-qPCR was conducted in the LightCycler® 480 (Roche Applied Science) using the FastStart Universal Probe Master (ROX) (Roche Applied Science) with the following program: 50 °C, 2 minutes; 95 °C, 10 minutes; 60 cycles of 95 °C, 15 seconds and 60 °C, 10 seconds; 4 °C.

These data were analyzed by One-sample Limma, a variant of t-test, and a p-value was obtained to validate the microarray studies. FDR multiple testing correction was calculated.

Gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR

26 patients (Baseline characteristics in Suppl. Table S13) were included in this study and 51 RNA samples from effluent-derived MC taken from these patients at different time points (2 to 24 months) were used for RT-qPCR. Omentum-derived MCs samples were used as control. The patients were either under Low GDPs containing fluid (Balance, Fresenius Medical Care) (N = 16) or High GDPs containing fluid (StaySafe, Fresenius Medical Care) (N = 10) PD regimens. Cell lysis and RNA extraction was done using TRI Reagent® Solution (Ambion,) according to the manufacturer´s instructions. Reverse transcription was realized used High Capacity RNA to cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems). The expression of the following 14 genes (Assay ID; Applied Biosystems) was assessed: CD44 (Hs01075861_m1), CDH1 (Hs01023894_m1), CDH13 (Hs01004530_m1), COL6A3 (Hs00915125_m1), COL13A1 (Hs00193225_m1), GREM1 (Hs00171951_m1), KDR (Hs00911700_m1), KRT34 (Hs02569742_s1), MMP1 (Hs00899658_m1), MMP2 (Hs01548727_m1), TFPI2 (Hs00197918_m1), THBD (Hs00264920_s1), THBS1 (Hs00962908_m1) and VEGF (Hs00900055_m1). The housekeeping gene TBP (Hs00427620_m1) was used as control.

RT-qPCR was conducted using the Taqman® Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems and Life Technologies; Carlsbad, California, USA) in 384 well plates with 2.5 μl of cDNA, 0.5 μl of Assay/primers, 5 μl of Taqman® Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and 2 μl of water per well. The 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) was used following conditions: 10’ 95 °C, 40 cycles of 15 s 95 °C, 1’ 60 °C. Data were recovered with SDS Software and analyzed with RQ Manager and DataAssist™ Software (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, California, USA). Data were normalized against TBP by 2−ΔΔCt method were selected analysis.

Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test was used to determinate significant differences between groups and corrects with FDR multiple testing correction.

Quantification of secreted protein by ELISA

Overnight peritoneal dialysis effluents from patients were collected and stored in −80 °C until used for protein analysis by ELISA. Effluent-derived MCs, effluent and supernatant samples were obtained from 26 PD patients (Suppl. Table S13) selected from ‘La Paz’ Hospital (Madrid, Spain) at initiation of PD (N = 25), 12 months (N = 23), 18 months (N = 18) and 24 months (N = 9). Protein levels of potential MMT markers TSP-1, VEGF (both R&D Systems), Collagen-13, Cadherin 13, Gremlin 1 (all of USCN Life Science Inc; Houston, Texas, USA), and MMP2 (Abnova Corporation; Taipei, Taiwan), which were identified in the microarray analysis, were analyzed in culture supernatant of effluent-derived MC by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). ELISAs were performed according to the respective manufacturer’s instructions. TSP-1, Collagen-13, Cadherin 13 and Gremlin1 were selected by their high mRNA expression in Non-Epithelioid phenotype, their expression in both ex vivo and in vitro models, their potentially secretable nature and consequently detectable in peritoneal effluents. Their relative novelty in this context also was considered. VEGF was selected as an internal control.

Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test was used to determinate significant differences between groups and Spearman correlation to linear regression between proteins in effluents and the Elliptical Factor. No correction for multiple testing was applied because this is still an exploratory study.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, GraphPad Prism v5 (GraphPad Software, Inc; La Jolla, California, USA) was used. Results are presented as mean values and SD. D’Agostino & Pearson normality test showed that the data were not normally distributed and indicated the use of non-parametric tests. One-sample Limma was used in microarray validation by RT-PCR, Mann-Whitney U-test was made for comparison between different groups in supernatants, effluents and patient mRNAs, Chi-Square Test was used to analyze the relation between phenotype and GDP-content, and a Spearman correlation was made to determinate linear regressions. Comparisons between groups in patient’s mRNAs were corrected with FDR multiple testing correction (TIGR MeV v4 software). p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Ruiz-Carpio, V. et al. Genomic reprograming analysis of the Mesothelial to Mesenchymal Transition identifies biomarkers in peritoneal dialysis patients. Sci. Rep. 7, 44941; doi: 10.1038/srep44941 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant SAF2013-47611R and SAF2016-80648R from the “Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad/Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional” (MINECO/FEDER) and by grant S2010/BMD-2321 (FIBROTEAM Consortium) from “Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid” to Manuel López-Cabrera and Rafael Selgas. Part of the study was supported by a research grant from Fresenius Medical Care. VR-C has been partially supported by a fellowship from grant BES-2008-009035 from the “Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación”.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Conception and design: V.R.-C., J.B., R.S., S.S. and M.L.-C. Development of methodology: V.R.-C., J.B. and M.L.-C. Acquisition of data: V.R.-C., P.S., P.A.-V., M.L.P.-L., G.T.G.-M., A.A.-R., J.B., P.B. and M.A.B. Analysis and interpretation of data: V.R.-C., A.A., J.G.-C., P.B., M.A.B., R.S., J.A.S.-T., D.P. and M.L.-C. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: V.R.-C., P.S., D.P., S.S. and M.L.-C. Study supervision: P.S., R.S., J.P.-D., S.S. and M.L.-C. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Krediet R. T. The peritoneal membrane in chronic peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int 55(1), 341–56 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devuyst O., Margetts P. J. & Topley N. The pathophysiology of the peritoneal membrane. J Am Soc Nephrol 21(7), 1077–85 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krediet R. T., Lindholm B. & Rippe B. Pathophysiology of peritoneal membrane failure. Perit Dial Int 20 Suppl 4, S22–42 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margetts P. J. & Churchill D. N. Acquired ultrafiltration dysfunction in peritoneal dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 13(11), 2787–94 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. J., Phillips L., Griffiths A. M., Russell L. H., Naish P. F. & Russell G. I. What really happens to people on long-term peritoneal dialysis? Kidney Int 54(6), 2207–17 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer F., Klaus G., Muller-Wiefel D. E. & Mehls O. Current practice of peritoneal dialysis in children: results of a longitudinal survey. Mid European Pediatric Peritoneal Dialysis Study Group (MEPPS). Perit Dial Int 19 Suppl 2, S445–S449 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroeira L. S. et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and peritoneal membrane failure in peritoneal dialysis patients: pathologic significance and potential therapeutic interventions. J Am Soc Nephrol 18(7), 2004–13 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margetts P. J. & Bonniaud P. Basic mechanisms and clinical implications of peritoneal fibrosis. Perit Dial Int 23(6), 530–41 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonesh E. F., Snyder J. J., Foley R. N. & Collins A. J. Mortality studies comparing peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: what do they tell us? Kidney Int Suppl (103), S3–11 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selgas R. et al. Functional longevity of the human peritoneum: how long is continuous peritoneal dialysis possible? Results of a prospective medium long-term study. Am J Kidney Dis 23(1), 64–73 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl J., Nessim S. J. & Bargman J. M. The biocompatibility of neutral pH, low-GDP peritoneal dialysis solutions: benefit at bench, bedside or both? Kidney Int 79(8), 814–24 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. D., Craig K. J., Topley N. & Williams G. T. Peritoneal dialysis: changes to the structure of the peritoneal membrane and potential for biocompatible solutions. Kidney Int Suppl (84), S158–61 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. D. et al. The Euro-Balance Trial: the effect of a new biocompatible peritoneal dialysis fluid (balance) on the peritoneal membrane. Kidney Int 66(1), 408–18 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Peso G. et al. Biocompatible dialysis solutions preserve peritoneal mesothelial cell and vessel Wall integrity. A case-control study on human biopsies. Perit Dial Int 36(2), 129–134 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y., Johnson D. W., Craig J. C., Stripolli G. F., Badve S. V. & Wiggins K. J. Biocompatible dialysis flluids for peritoneal dialysis. Cochrane Database Sys Rev Mar 27, (3), CD007554 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Z. G. et al. Biocarbonate versus lactate solutions for acute peritoneal dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Jul 4; (7), CD007034 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach M., Zaloszyc A., Schaefer B. & Schmitt C. P. Optimizing peritoneal dialysis prescription for volume control: the importance of varying dwell time and dwell volume. Pediatr Nephrol 29(8), 1321–7 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt C. P., Zaloszyc A., Schaefer B. & Fischbach M. Peritoneal dialysis tailored to pediatric needs. Int J Nephrol 2011, 940267 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Mateo G. T., Aroeira L. S., López-Cabrera M., Ruiz-Ortega M., Ortiz A. & Selgas R. Pharmacological modulation of peritoneal injury induced by dialysis fluids: is it an option? Nephrol Dial Transplant 27(2), 478–81 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo N. & Sacchi G. Atlas of peritoneal histology. Perit Dial Int 20 Suppl 3, S5–96 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yáñez-Mo M. et al. Peritoneal dialysis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells. N Engl J Med 348(5), 403–13 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Cabrera M. et al. Ex vivo analysis of dialysis effluent-derived mesothelial cells as an approach to unveiling the mechanism of peritoneal membrane failure. Perit Dial Int 26(1), 26–34 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Cabrera M. Mesenchymal conversion of mesothelial cells is a key event in the pathophysiology of the peritoneum during peritoneal dialysis. Adv Med 2014, 473134 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroeira L. S. et al. Cyclooxgenase-2 mediates dialysate-induced alterations of the peritoneal membrane. J Am Soc Nephrol 20(3), 582–92 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krediet R. T. Dialysate cancer antigen 125 concentration as marker of peritoneal membrane status in patients treated with chronic peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 21(6), 560–7 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. et al. Dialysate interleukin-6 predicts increasing peritoneal solute transport rate in incident peritoneal dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol 15, 8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroeira L. S. et al. Mesenchymal conversion of mesothelial cells as a mechanism responsible for high solute transport rate in peritoneal dialysis: role of vascular endothelial growth factor. Am J Kidney Dis 46(5), 938–48 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecoits-Filho R. et al. Plasma and dialysate IL-6 and VEGF concentrations are associated with high peritoneal solute transport rate. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17(8), 1480–6 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweers M. M., Struijk D. G., Smit W. & Krediet R. T. Vascular endothelial growth factor in peritoneal dialysis: a longitudinal follow-up. J Lab Clin Med 137(2), 125–32 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutani M. et al. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF/CCN2) is increased in peritoneal dialysis patients with high peritoneal solute transport rate. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298(3), F721–33 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique I. et al. Gremlin promotes peritoneal membrane injury in an experimental mouse model and is associated with increased solute transport in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Pathol 184(11), 2976–84 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padwal M. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 is associated with peritoneal membrane solute transport and induces angiogenesis through β-catenin signaling. Nephrol Dial Transplant pii:gfw076 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catar R. et al. The proto-oncogen c-Fos transcriptionally regulates VEGF production during peritoneal inflammation. Kidney Int 84(6), 1119–28 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strippoli R., Benedicto I., Pérez-Lozano M. L., Cerezo A., López-Cabrera M. & del Pozo M. A. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of peritoneal mesothelial cells is regulated by an ERK/NK-kappaB/Snail1 pathway. Dis Model Mech 1(4–5), 264–74 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang J. & Asahina K. Mesothelial cells give rise to hepatic stellate cells and myofibroblasts via mesothelial-mesenchymal transition in liver injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110(6), 2324–9 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Lua I., French S. W. & Asahina K. Role of TGF-β signaling in differentiation of mesothelial cells to vitamin A-poor hepatic stellate cells in liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Physiol 310(4), G262–72 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lua I. & Asahina K. The role of mesothelial cells in liver development, injury and regeneration. Gut Liver 10(2), 166–76 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busnadiego O. et al. A pathogenetic role for endothelin-1 in peritoneal dialysis-associated fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 26(1), 173–82 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. et al. Curcumin inhibits transforming growth factor-β1-induced EMT via PPARγ pathway, not Smad pathway in renal tubular epithelial cells. PLoS One 8(3), e58848 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y. L., Xiong X. Z. & Cheng N. S. Organ fibrosis inhibited by blocking transforming growth factor-β via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 11(5), 467–78 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reka A. K. et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation inhibits tumor metastasis by antagonizing Smad3-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cancer Ther 9(12), 3221–32 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Diez R. et al. Gremlim is a downstream profibrotic mediator of transforming growth factor beta in cultured renal cells. Nephron Exp Nephronl 122(1–2), 62–74 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Lozano M. L. et al. Functional relevance of the switch of VEGF receptors/coreceptors during peritoneal dialysis-induce mesothelial to mesenchymal transition. PLoS One 8(4), e60776 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Peso G. et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells is an early event during peritoneal dialysis and is associated with high peritoneal transport. Kidney Int Suppl (108), S26–33 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Heffernan J. A. et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fibroblast subpopulations in normal peritoneal tissue and in peritoneal dialysis-induced fibrosis. Virchows Arch 444(3), 247–56 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes Barreto D. & Krediet R. T. Current status and practical use of effluent biomarkers in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 62(4), 823–33 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Perpén A. et al. Influence of bicarbonate/low-GDP peritoneal dialysis fluid (BicaVera) on in vitro and ex vivo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of mesothelial cells. Perit Dial Int 32(3), 292–304 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajo M. A. et al. Low-GDP peritoneal dialysis fluid (‘balance’) has less impact in vitro and ex vivo on epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of mesothelial cells than a standard fluid. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26(1), 282–91 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do J. Y. et al. The association between the vascular endothelial growth facto-to-cancer antigen 125 ratio in peritoneal dialysis effluent and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 28 Suppl 3, S101–6 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis J. et al. Collagen XIII induced in vascular endothelium mediates alpha1beta1 integrin-dependent transmigration of monocytes in renal fibrosis. Am J Pathol 177(5), 2527–40 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler P. R. & Lawler J. Molecular basis for the regulation of angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1 and -2. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2(5), a006627 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J. C. & Lawler J. The thrombospondins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3(10), a009712 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro J. et al. Blocking TGF-β1 protects the peritoneal membrane Fromm dialysate-induced damage. J Am Soc Nephrol 22(9), 1682–95 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen A., Tu H. & Pihlajaniemi T. Collagen XIII: a type II transmembrane protein with relevance to musculoskeletal tissues, microvessels and inflammation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 44(5), 714–7 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Väisänen T., Väisänen M. R., Autio-Harmainen H. & Pihlajaniemi T. Type XIII collagen expression is induced during malignant transformation in various epithelial and mesenchymal tumours. J Pathol 207(3), 324–35 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth K. D., Chua K. Y., Talbot V. & Thomas W. R. Expression of the leukocyte common antigen CD45 by endothelium. J Immunol 1993 150(8 Pt 1), 3471–7 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strippoli R. et al. Caveolin-1 deficiency induces a MEK-ERK 1/2-Snail-1-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibrosis during peritoneal dialysis. EMBO Mol Med Dec 30 7(1), 102–23 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina I. et al. Babelomics: an integrative platform for the analysis of transcriptomics, proteomics and genomic data with advanced functional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res 38(Web Server issue), W210–3 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A. I. et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques 34(2), 374–8 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.