Abstract

This study examined whether Medicaid claims and other administrative data could identify high-need individuals with serious mental illness in need of outreach in a large urban setting. A claims-based notification algorithm identified individuals belonging to high-need cohorts who may not be receiving needed services. Reviewers contacted providers who previously served the individuals to confirm whether they were in need of outreach. Over 10,000 individuals set a notification flag over 12-months. Disengagement was confirmed in 55 % of completed reviews, but outreach was initiated for only 30 %. Disengagement and outreach status varied by high-need cohort.

Keywords: Engagement, Behavioral health, Administrative data, Medicaid, Outreach, Serious mental illness

Introduction

Mental health policy makers and services researchers routinely use administrative and claims data to describe population characteristics, service costs, quality of care, and treatment outcomes (Nosé et al. 2003; Gilmer et al. 2004; Fischer et al. 2008; Riley 2009; Frayne et al. 2010; Olfson et al. 2012). These are often retrospective efforts, however, and as health information technology advances, the question arises whether service providers can use administrative data to inform and enhance individual care planning. For example, 30–40 % of individuals with serious mental illness fail to attend scheduled initial outpatient mental health clinic visits (Nosé et al. 2003; Compton et al. 2006; Kruse et al. 2002; Mitchell and Selmes 2007; Stein et al. 2007) and up to 45 % discontinue recommended treatment (Fischer et al. 2008; Nosé et al. 2003; O’Brien et al. 2009; Kreyenbuhl et al. 2009). Real-time availability of service history data should help providers understand why individuals are not receiving needed services and improve outreach and engagement efforts. Algorithms using prior service use data have been developed to identify and intervene with high-cost, high-need users of physical health services (Billings and Mijanovich 2007; Raven et al. 2009) but we know of no similar efforts that focus on high-need individuals with serious mental illness.

The New York City Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative was an effort to use administrative data to identify high-need individuals with serious mental illness who may not be receiving adequate community-based services, or who may be using excessive acute services. Previous reports described the development and implementation of the project (Smith et al. 2011a, b). In this report, we present findings from the initiative’s first 12 months of care monitoring. We document efforts to confirm engagement status of identified high-need individuals, and describe patterns of disengagement from services.

Methods

The New York City Public Mental Health System

In 2010, New York City (NYC) had a population of over 8 million individuals, including ~3 million who were eligible for Medicaid, the United States’ publicly financed health and long-term care coverage program for low-income people. Medicaid provides coverage for individuals who are unable to obtain private insurance or for whom such insurance is inadequate. Medicaid is an important national safety net program for poor individuals with chronic illnesses and/or disabilities (Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured 2010). Behavioral health services for the approximately 125,000 NYC Medicaid beneficiaries who were disabled due to a psychiatric disorder were paid for via fee-for-service (other Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in managed care plans that covered their physical and behavioral health services). These individuals, who accounted for over 26,000 inpatient mental health admissions in 2010, were the target population for the project reported herein. Outpatient services were available to this population from over 250 licensed clinics, nearly 12,000 case management slots, and 44 Assertive Community Treatment teams.

The NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative

The NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative was implemented by city and state mental health oversight agencies in 2009 following recommendations of a review panel that examined prior instances of violence involving individuals with mental illness (Hogan et al. 2008; Smith and Sederer 2009). The panel found that individuals with serious mental illness who were involved in episodes of violence were often well known to the mental health treatment system. These individuals typically had received extensive services but frequently discontinued care, especially when using substances or experiencing crises such as severe symptom exacerbations, criminal justice involvement, or housing problems. Mental health providers had little incentive to outreach to these individuals after they had discontinued care. The panel recommended that city and state mental health oversight agencies develop an initiative that used Medicaid claims and other administrative data to help providers identify and outreach to high-need individuals with serious mental illness who were at risk for discontinuing needed services.

The NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative used Medicaid claims and other state administrative data to identify Medicaid-enrolled adults age 18 and older belonging to 1 of 7 high-need cohorts. The cohorts were defined such that nearly all individuals had a serious mental illness. Four of the 7 cohorts were defined based upon receipt of community-based mental health services in the prior 12 months, including individuals who: (1) had an active court order to receive Assisted Outpatient Treatment under New York State’s outpatient commitment statute (AOT cohort); (2) had received Assertive Community Treatment in the prior 12 months (ACT cohort); (3) had received intensive case management services in the prior 12 months (ICM cohort); or (4) had received blended case management (which included a combination of intensive and supportive case management) services in the prior 12 months (BCM cohort) (see Table 1 for description of services). The remaining cohorts included individuals who: (5) had previously received but were not currently receiving Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT Expired cohort); (6) had previously received mental health services in a state forensic psychiatric setting and were presently living in the community (Forensic cohort); or (7) had two or more psychiatric emergency room or inpatient hospitalizations in the prior 12 months where the primary diagnosis was serious mental illness or substance abuse disorder (Multi-Acute User cohort). Individuals were assigned to these high-need cohorts hierarchically in the order above, with individuals assigned to the first cohort for which they qualified. Cohort membership was originally established in September 2009 and updated each month throughout the project period.

Table 1.

Description of selected programs and case management services for individuals with serious mental illness in New York City, 2010

| Description | Eligibility criteria | Staff caseload | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT) | Court-ordered services for individuals with mental illness who, in view of their treatment history and circumstances, are unlikely to survive safely in the community without supervision | Adults with mental illness who have not been adherent with treatment and have had: (a) ≥2 psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 36 months or any forensic mental health treatment in prior 6 months; and (b) one of more acts of serious violent behavior toward self or others or threats of, or attempts at, serious physical harm to self or others within the last 48 months | Individual treatment plans must include either ACT or case management services |

| Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) | Multi-disciplinary team offering community-based treatment and support services | Serious mental illness with functional impairments, not adherent with clinic care, and high use of acute services (e.g., ≥4 psychiatric hospitalizations, or ≥3 emergency room/mobile crisis visits, in prior 12 months) | Client: Staff ratio not to exceed 9.9:1 |

| Intensive Case Management (ICM) | Trained case manager helps individuals access needed medical, social, psychosocial, educational, financial, and other services required to encourage independent functioning in the community | Serious mental illness with functional impairments and high use of acute services (e.g., ≥2 psychiatric hospitalizations, or ≥3 emergency room/mobile crisis visits, in prior 12 months) | Not to exceed 12; at least 1 contact/week |

| Supportive Case Management (SCM) | As above | Serious mental illness with functional impairments and demonstrated need for ongoing supportive services | Not to exceed 20; at least 2 contacts/month |

The state mental health oversight agency also created 3 “notification flags” using Medicaid claims data to identify individuals who may have disengaged from community-based services. The flags identified individuals who: (1) failed to fill psychotropic medication prescriptions for more than 60 days; (2) had no community-based mental health services in the prior 120 days; or (3) had two or more psychiatric inpatient admissions or emergency room visits in the prior 120 days.

During a 3-month training and pilot phase from October–December 2009, state project oversight leaders met with a contracted managed behavioral health organization (MBHO) several times per week to develop procedures for examining prior service use data, conducting reviews, and coding engagement status. Names and prior service use data for individuals in the high-need cohorts who set one or more of the notification flags were provided to the MBHO each month. These data were loaded into the MBHO’s electronic health record and reviewed by licensed, experienced mental health clinicians. The MBHO hired and trained 8 clinician “care monitors” for the first team, which covered the borough of Brooklyn. A care monitor examined the notification and prior service use data and initiated telephone contact with providers identified in the claims data who had served the individual. In some instances this required one or a few calls. The project targeted individuals who were likely to have disengaged from care, however, many of whom had multiple brief contracts with providers in emergency room, inpatient, mobile crisis, case management, and clinic settings in the prior 12 months. The majority of cases therefore required phone calls to several prior providers. The care monitor identified the provider most familiar with the individual’s prior plan of care, alerted the provider to the individual’s recent pattern of service use, and determined whether the individual was currently receiving adequate and appropriate community-based services. If not, the care monitor helped the provider develop a plan for outreach, when possible. Care monitors encouraged providers who had previous service relationships to outreach to individuals who were disengaged from services, and followed up with providers at least monthly to track re-engagement status.

Early in the initiative, providers expressed concerns about confidentiality and expectations regarding case reviews for individuals, many of whom had been discharged from their care. Care monitors and the MBHO leadership committed significant resources to educating providers regarding the role of the initiative and its authority to conduct reviews. For approximately 50 % of cases, care monitors completed reviews within 40 days of MBHO receipt of notification data. The remaining cases took longer to review because of difficulty identifying providers familiar with the individual and able to participate in the reviews.

An important distinction was made between complete versus incomplete reviews, with incomplete reviews grouped into three categories: (1) cases in which there was inadequate clinical information available to determine the individual’s current situation (e.g., when there was no or minimal prior service use and the care monitor was unable to identify a provider to review the case); (2) cases in which providers identified with recent claims were not licensed or contracted by the NY city/state mental health regulatory agencies and hence not able to be contacted by the care monitors under confidentiality rules (e.g., private practitioners or clinics licensed by the NYS Department of Health or the NYS Office of Alcohol and Substance Abuse Services did not fall under the purview of the mental health authorities and therefore could not be contacted to review confidential protected health information); and (3) cases in which providers did not respond to care monitor requests for clinical reviews.

Completed case reviews were assigned to 1 of 3 categories. Level 1 cases included those where the apparent gap in services did not represent a clinical concern (“No Clinical Concern”). For example, individuals setting the “no medication” notification flag may have received medication from a provider’s sample supplies, and therefore had not used Medicaid prescription benefits. Level 2 or “Moderate Clinical Concern” cases involved situations where the individual was not adequately engaged in community-based care but for whom a provider had implemented a suitable outreach plan. An example was an individual receiving Assertive Community Treatment, who had a symptom relapse and was hospitalized twice in the prior 4 months. This case was categorized as Level 2 because the Assertive Community Treatment team was aware of the hospitalizations, identified the stressors associated with the relapse, and worked with the inpatient treatment team to modify the individual’s care plan such that the individual remain engaged with the community-based team and no longer required acute inpatient care. Level 3 (“High Clinical Concern”) cases involved situations where the individual was disengaged from care and no provider outreach had been initiated. Examples included individuals who refused treatment and were lost to care, as well as situations when providers referred individuals to services that were never received (e.g., no follow up after discharge from a hospital).

The care monitors met weekly with project leadership throughout the initiative to review cases and criteria for level assignments. The MBHO employed a quality manager who conducted quarterly record reviews to monitor reliability of case level assignments. The first 3 months of case reviews were not included in this report because the level criteria were being refined and staff were being trained. The city/state mental health oversight team conducted an on-site review in the 10th month of the project, which included 35 randomly selected closed record reviews. The accuracy of care monitor ratings across all levels was high; auditors agreed with care monitor coding on 34 of the 35 cases.

Case Summaries and Data Analyses

Data were extracted from MBHO records of care monitor reviews of individuals in the high-need cohorts who set one or more notification flags between January and December 2010, and who were residing in Brooklyn (where the initial care monitoring team was located). Completed case reviews were assigned to one of the 3 level categories (No, Moderate, or High Clinical Concern) and cases in the High Clinical Concern category were further assigned to one of 5 subcategories based upon the type of disengagement from care. Cases were coded as “No Identified Service Provider” when the individual was lost to care and there was no provider who could attempt outreach at the time of the review. The “Outreach Underway” assignment was made when a provider was identified that could provide outreach to the disengaged individual. For example, recent service use information for a disengaged individual was provided to a case manager who worked with the individual in the prior year. The case manager agreed to contact and attempt to re-engage the individual.

The third subcategory included cases coded as “Incarcerated” when the individual was in jail or prison. An “Enhanced Outreach Necessary” assignment reflected the care monitor’s assessment that a significant risk of imminent poor outcome existed and that unusually close monitoring and heightened efforts to outreach to the individual were warranted. An example was a single woman with a serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use, who also had a history of arrest for assault and several prior suicide attempts. She had previously self-referred to a clinic after giving birth to her fifth child but had discontinued care. Given her history and child-care responsibilities, the care monitor determined that this woman should receive immediate outreach and sustained efforts to re-engage. A final subcategory of “Re-Engaged Within the Month” was used for individuals who had re-engaged with adequate and appropriate services within the monthly review period after being determined to have discontinued needed services.

The data reported herein include counts of: (1) individuals belonging to the high-need cohorts in Brooklyn during calendar year 2010; (2) individuals setting each notification; (3) cases reviewed and completed; and (4) assignments to the defined review categories. The results of reviews are described in aggregate form and broken out for the identified high-need cohorts. The institutional IRB found the initiative to be a quality improvement activity that did not constitute research involving human subjects.

Results

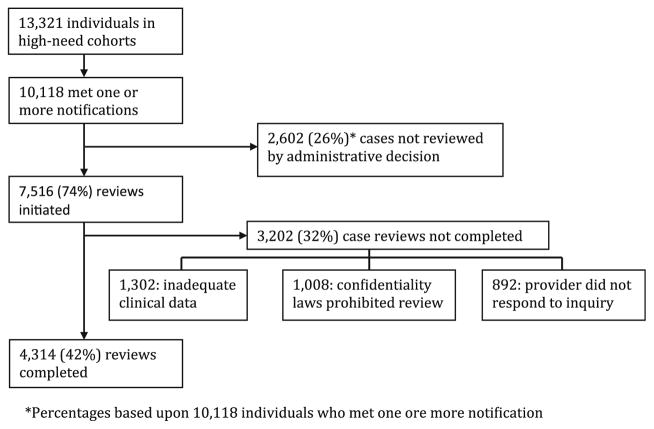

Between January and December 2010, 13,321 individuals belonged to one of the 7 high-need cohorts in Brooklyn and 10,118 (76 %) set one or more notification flags (Fig. 1). Care monitors initiated reviews for 7,516 of these individuals. There were no similar programs from which to estimate staffing needs and the MBHO did not have enough care monitors to review all cases. The MBHO leadership used various triage strategies over the 12-month period to prioritize cases for review. For example, individuals in the Multi-Acute User cohort with no or minimal recent service use were triaged as lowest priority for initiating reviews, given the low likelihood that care monitors would have been able to contact a provider familiar with the individual’s recent care. Of the 7,516 initiated cases, reviews could not be completed for 3,202 (43 %). For 1,302 (41 %) of these cases there was inadequate clinical information and for 1,008 (31 %) cases, confidentiality restrictions prevented care monitors from completing reviews with providers. Providers did not respond to care monitor requests for clinical reviews for the remaining 892 (28 %) incomplete reviews.

Fig. 1.

Target high-need cohorts and cases reviewed in NYC Care Monitoring Initiative, January–December 2010, Brooklyn

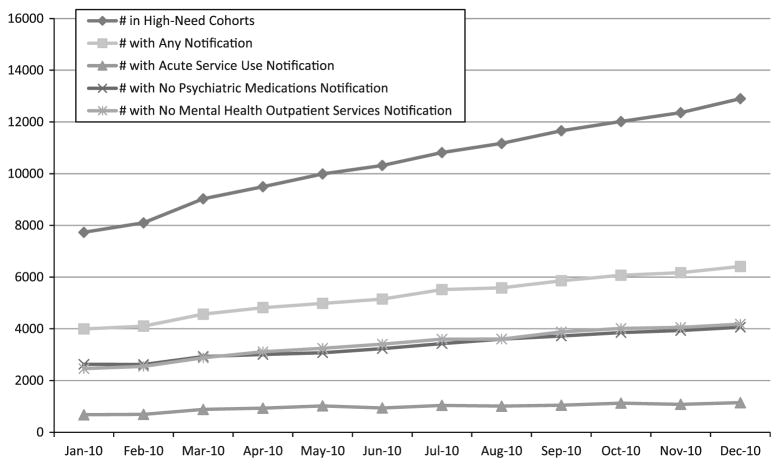

Figure 2 shows the cumulative numbers of individuals setting notification flags each month. High-need cohort membership was refreshed each month and new individuals added such that the total cohort membership in Brooklyn increased from 7,732 in January 2010 to approximately 13,000 in December 2010. No individuals were removed from any cohort and the size of the cohorts increased steadily throughout the year. The rates at which individuals set the three notification flags each month remained stable throughout 2010, such that the numbers of individuals setting specific notifications increased steadily and paralleled the increase in overall cohort size.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative numbers of individuals in high-need cohorts meeting notifications in Brooklyn, January–December 2010

Table 2 lists the cumulative numbers of individuals in the high-need cohorts along with those who set a notification and had a review initiated. The AOT cohort had significantly fewer individuals (37 %) setting a notification than other cohorts (χ2 = 222.07, p < 0.001), while between 56 and 70 % of the ACT, ICM, BCM, AOT Expired, and Forensic cohorts set a notification at some point in 2010. The Multi-Acute User cohort was the largest and included over 80 % of the total number of individuals in the project. Eighty-seven percent of the Multi-Acute User cohort set a notification flag in 2010.

Table 2.

Results of case reviews for individuals belonging to high-need cohorts in Brooklyn, January–December 2010

| Size of risk cohort | Individuals meeting a notification (N, % of risk cohort)

|

Reviews completed (N, % of cases with notification)

|

Complete review ratings (N, % of reviews completed)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No concern

|

Moderate concern

|

High concern

|

|||||||||

| N | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| AOT | 270 | 101 | 37 | 100 | 99 | 66 | 66 | 9 | 9 | 25 | 25 |

| ACT | 1,091 | 612 | 56 | 530 | 87 | 199 | 38 | 116 | 22 | 215 | 41 |

| ICM | 596 | 417 | 70 | 345 | 83 | 107 | 31 | 67 | 19 | 171 | 50 |

| BCM | 1,620 | 941 | 58 | 764 | 83 | 254 | 33 | 197 | 26 | 313 | 41 |

| AOT expired | 599 | 358 | 60 | 288 | 80 | 53 | 18 | 30 | 10 | 205 | 71 |

| Forensic | 1,427 | 1,009 | 71 | 556 | 55 | 84 | 15 | 66 | 12 | 406 | 73 |

| Multi-acute | 7,718 | 6,680 | 87 | 1,731 | 26 | 166 | 10 | 512 | 30 | 1,053 | 61 |

| Total | 13,321 | 10,118 | 76 | 4,314 | 43 | 929 | 22 | 997 | 23 | 2,388 | 55 |

AOT assisted outpatient treatment, ACT assertive community treatment, ICM intensive case management, BCM blended case management, AOT expired assisted outpatient treatment-expired order, Multi-acute multiple acute service use

Reviews were initiated for 62 % of cases from the Multi-Acute User cohort and for 80–99 % of the ACT, ICM, BCM and AOT Expired cases setting a notification. Completion rates were significantly lower for the Forensic (55 %; χ2 = 305.04; p < 0.001) and Multi-Acute User cohorts (26 %; χ2 = 2430.81; p < 0.001) than for the other groups. Individuals in these 2 cohorts were more likely to have had providers that the MBHO could not contact due to confidentiality restrictions, or for there to be insufficient information for the care monitors to judge whether the individual was engaged in adequate services. Care monitors documented diagnoses from provider records, and many individuals had multiple diagnoses. Alcohol dependence was the most common diagnosis in the Multi-Acute User cohort, followed by schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder. In the Forensic cohort, schizoaffective disorder and alcohol dependence were the most common diagnoses. For all other cohorts, schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder were the most common diagnoses.

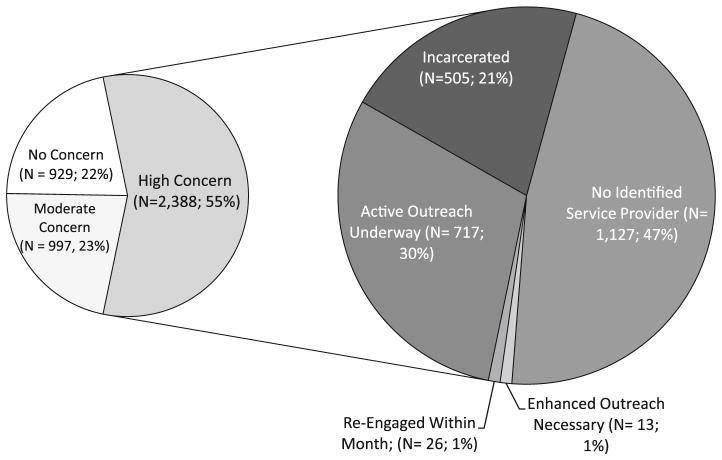

Figure 3 shows the level assignments for the 4,314 cases in which care monitors completed reviews. For 22 % of cases there was no clinical concern associated with the notification, but in 78 % of the completed reviews the individual was noted to have a current or recent gap in services (the Moderate and High Clinical Concern categories). The AOT Expired (71 %; χ2 = 85.7, p < 0.001), Forensic (73 %; χ2 = 164.8, p < 0.001), and Multi-Acute User cohorts (61 %; χ2 = 85.7, p < 0.001), had significantly higher rates of High Clinical Concern cases relative to the AOT (25 %), ACT (41 %), ICM (50 %), and BCM (41 %) cohorts (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Category assignments for 4,314 completed case reviews with High Clinical Concern subgroup classifications

Figure 3 also shows a breakdown of the 2,388 cases listed as High Clinical Concern based upon care monitor ratings of the type of disengagement from care. Forty-seven percent of High Clinical Concern cases were coded as No Identified Service Provider. For 30 % of High Clinical Concern cases, a provider was identified that could provide outreach to the individual at the time of review, while for another 21 %, the individual was in jail or prison. One percent of the High Clinical Concern cases were coded as Enhanced Outreach Necessary and another 1 % of cases were coded as Re-Engaged Within the Month after being determined to have discontinued needed services.

Table 3 lists numbers of individuals in each of the high-need cohorts that had completed reviews and were coded in one of the High Clinical Concern subcategories. The Multi-Acute User cohort had the highest rate of individuals confirmed to be lost to care (59 % coded as No Identified Service Provider) while the other cohorts ranged from 12 to 43 % of High Clinical Concern cases in this category. The AOT, ACT, ICM, and BCM cohorts had higher percentages of individuals in the Outreach Underway category (41–84 %). For individuals in high-need cohorts defined according to prior legal involvement (the AOT Expired and Forensic cohorts), 33–43 % of the disengaged individuals were incarcerated at the time of the review, versus 0–19 % of individuals in all other cohorts.

Table 3.

Classification of high clinical concern cases by risk cohort

| Number of high clinical concern cases | Outreach underway

|

Enhanced outreach necessary

|

Incarcerated with anticipated released <3 months

|

No identified service provider

|

Re-engaged with month

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| AOT | 25 | 21 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 4 |

| ACT | 215 | 125 | 58 | 1 | 0 | 40 | 19 | 48 | 22 | 1 | 0 |

| ICM | 171 | 77 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 12 | 73 | 43 | 1 | 1 |

| BCM | 313 | 129 | 41 | 3 | 1 | 45 | 14 | 134 | 43 | 2 | 1 |

| AOT Expired | 205 | 48 | 23 | 6 | 3 | 67 | 33 | 84 | 41 | 0 | 0 |

| Forensic | 406 | 64 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 176 | 43 | 161 | 40 | 4 | 1 |

| Multi-Acute | 1,053 | 253 | 24 | 2 | 0 | 157 | 15 | 624 | 59 | 17 | 2 |

| Total | 2,388 | 717 | 30 | 13 | 1 | 505 | 21 | 1,127 | 47 | 26 | 1 |

AOT assisted outpatient treatment, ACT assertive community treatment, ICM intensive case management, BCM blended case management, AOT expired assisted outpatient treatment-expired order, Multi-acute multiple acute service use

Although not the primary focus of this report, we examined reasons for disengagement for a subset of 151 individuals coded as High Clinical Concern-Outreach Underway in the first quarter of 2010. The most common provider-reported reason for disengagement involved individuals who failed to connect with outpatient services following a hospitalization (43 %). For 23 % of cases, providers reported disagreements regarding treatment plans as the primary reason for disengagement and for 9 % of cases, disengagement was related to failed transition from one provider to another. Refusal of services by individuals was listed as the primary reason for disengagement in only 6 % of cases.

Discussion

In the NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative, an administrative and Medicaid claims data monitoring system successfully identified high-need individuals with serious mental illness who were experiencing gaps in needed services. During a 12-month period the data monitoring system identified over 10,000 high-need individuals and trained clinical staff reviewed 7,500 cases. More than 75 % of the 4,300 individuals with completed reviews were recently or currently disengaged from community-based care.

Our findings of high rates of disengagement are consistent with those from the National Comorbidity Study, a population-based survey which found that only 38.5 % of individuals with serious mental illness received stable treatment in the previous 12 months (Kessler et al. 2001) and only 15 % received minimally adequate care (Wang et al. 2002). The rate of disengagement in our study is higher than the treatment dropout rates reported in clinical samples, which vary from 30 to 50 % depending on the time period and measurement strategy (Nosé et al. 2003; Compton et al. 2006; Stein et al. 2007; O’Brien et al. 2009; Kreyenbuhl et al. 2009). This is likely due to our project’s specific focus on high-need populations with recent service use data suggesting individuals were not engaged in adequate or appropriate services.

Fifty percent of cases with completed reviews were not engaged in adequate and appropriate services at the time of review. Of these, 75 % were either in the criminal justice system or lost to care. The involvement with the criminal justice system is consistent with other studies showing that increasing numbers of individuals with serious mental illness receive services in prison or jail settings (Theriot and Segal 2005; Cuellar et al. 2007; Ascher-Svanum et al. 2010). This underscores the need for services that identify individuals with serious mental illness within the criminal justice system and coordinate mental health services accordingly. Our preliminary data regarding reasons for disengagement for individuals receiving active outreach from providers also highlights the importance of efforts to facilitate transitions among providers and between levels of care.

The significant percentage of individuals who were lost to care suggests that much can be done to enhance engagement and retention in services for high-need individuals. Several interventions exist to improve treatment adherence (Zygmunt et al. 2002; Dolder et al. 2003; Burns et al. 2007; Appelbaum and Le Melle 2008), yet little can be done when an individual has left care entirely. The findings from this project underscore the importance of provider strategies to engage and retain individuals in care. For example, a recovery-oriented approach emphasizes individual choice, shared decision-making, and personalized goals (Farkas et al. 2005; Sowers 2005; Adams et al. 2007; Drake and Deegan 2009). Such an approach is more likely to be effective with the high-need individuals described in this report, who do not consistently engage in traditionally defined and organized services.

Findings from this project reinforce the need for greater outreach to high-need individuals with serious mental illness. The relatively lower percentage of individuals in the AOT cohort who set notifications supports this notion, as these individuals receive intensive monitoring (though other research has not established that court orders in and of themselves lead to improved engagement; see Burns et al. 2013). The ACT, ICM, and BCM cohorts had intermediate rates of setting notifications and confirmed disengagement, whereas the Multi-Acute User cohort had the highest rates of setting one or more notifications. This likely reflects the impact of programs like ACT and case management that include varying levels of community outreach and engagement efforts.

The Multi-Acute User cohort was the largest of all cohorts, and had a high percentage of individuals who remained disengaged from community-based services following discharge from emergency room or inpatient units. These individuals had few or no recent connections with community-based providers, were high users of acute services, and had significant rates of co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders. Many were not impaired enough to be mandated into care (either inpatient or outpatient) and presented a dilemma to providers who are unable to engage them in short-term, fast-paced acute service environments. These individuals could benefit greatly from “bridger” programs or other critical time intervention services during transitions from inpatient to community-based care.

There are important limitations to these findings. We did not assess reliability of claims diagnoses nor were we able to report rates of specific disorders or co-occurring/co-morbid conditions. Of the 10,118 individuals who set one or more notifications, only 4,314 (43 %) had completed reviews, raising concerns about whether the findings are representative of the overall target population. It is possible that this study underestimates the numbers of high-need individuals who were disengaged from services. Completed reviews identified providers who were aware of individuals’ prior service plans and needs, suggesting that these individuals were more likely to be engaged in care as compared to cases in which no provider could be identified to review individuals’ prior service plans. Also, many of the Multi-Acute User cases that were triaged out and not reviewed due to staffing limitations had no or minimal recent service use, making it unlikely that a provider could be identified who was familiar with the individual.

At the same time, this project may have had a response bias in favor of identifying disengaged individuals. For many cases, substance use treatment providers were not contacted because of confidentiality regulations, and it is possible that many of the individuals receiving services from these providers were engaged in adequate and appropriate services. Future similar initiatives could address the confidentiality issue, for example by creating memoranda of understanding with other state regulatory agencies (department of health, substance abuse services authority) that oversee those service providers. Our approach also did not account for individuals who may have achieved significant recovery. These individuals could meet the flags for receiving no Medicaid-funded services, but may have graduated from publicly funded community mental health services to independence or to more normalized community supports.

Our approach focused on defined high-need cohorts, and 76 % of individuals belonging to these cohorts met one or more of the notification flags over the 12-month project period. A priori, we did not anticipate such a high percentage of individuals meeting notification flags. Further analyses of our data should identify patterns of notifications that are more predictive of disengagement status as confirmed by reviews, and will dictate modifications to the notification algorithms that could increase the sensitivity of this monitoring approach.

The NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative focused on Brooklyn residents during 2010. Prior analyses suggested that Brooklyn residents account for approximately 30 % of the total NYC intensive case management service and Assertive Community Treatment services. Brooklyn is a large, diverse borough that provides a representative cross-section of NYC services and individuals who access care. New York State is undertaking significant Medicaid reform (New York State Department of Health 2012), which will include enrollment of all beneficiaries into managed care plans. In 2012, New York State contracted with MBHOs to begin concurrent review for inpatient behavioral health services statewide, and based upon information generated by the NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative, MBHOs are required to incorporate monitoring activities for a subset of the original high-need cohorts identified in the project described in this report.

There are no other published studies using claims and administrative data to track engagement in high-need populations such as those defined in this project, and we do not know if the patterns we observed would be seen in populations in other communities or in other populations of individuals with serious mental illness. NYC is a large urban area with multiple unique characteristics, and the high-need cohorts chosen for monitoring reflect the structure of the city’s public mental health system. Funding streams, oversight activities, and service arrays for individuals receiving public mental health services vary widely across states. Efforts to implement similar care monitoring approaches should identify high-need cohorts and notification flags most relevant to regional public mental health system characteristics and priorities. The NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative is a useful model for other states that demonstrates how administrative data can be used to monitor high-need populations and identify individuals who are inadequately engaged in community-based services and in need of outreach. The cost to implement the project in Brooklyn was $2.2 million over a fiscal year, which was a small fraction of the $5 billion in state Medicaid funds spent on behavioral health services in 2009. Given the high costs incurred in the care of these individuals, as well as the burden on individuals, families, and communities related to inadequately treated mental illness, states should consider similar efforts to monitor service use and support provider outreach.

Conclusions

The NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative used administrative data to identify individuals with serious mental illness and high service needs who appeared not to be receiving appropriate services. Providers were able to initiate outreach for only 30 % of disengaged individuals, suggesting that further work is needed to improve care coordination within the public mental health system. Data from this project will be examined further to identify factors and interventions that predict re-engagement in services and further enhance the safety net for high-need populations.

Footnotes

This manuscript has not been presented at an academic meeting.

Contributor Information

Thomas E. Smith, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, New York, NY, USA. New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York State Office of Mental Health, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, NY 10032, USA

Anita Appel, New York City Field Office, New York State Office of Mental Health, New York, NY, USA.

Sheila A. Donahue, Office of Performance Measurement and Evaluation, New York State Office of Mental Health, New York, NY, USA

Susan M. Essock, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, New York, NY, USA. New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York State Office of Mental Health, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, NY 10032, USA

Doreen Thomann-Howe, Harlem United, New York, NY, USA.

Adam Karpati, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, New York, NY, USA.

Trish Marsik, Bureau of Mental Health, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, New York, NY, USA.

Robert W. Myers, New York State Office of Mental Health, Albany, NY, USA

Mark J. Sorbero, Community Care Behavioral Health Organization, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Bradley D. Stein, RAND Corporation, New York, NY, USA. University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

References

- Adams JR, Drake RE, Wolford GL. Shared decision-making preferences of people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(9):1219–1221. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Le Melle S. Techniques used by assertive community treatment (ACT) teams to encourage adherence: Patient and staff perceptions. Community Mental Health Journal. 2008;44(6):459–464. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascher-Svanum H, Nyhuis AW, Faries DE, Ball DE, Kinon BJ. Involvement in the US criminal justice system and cost implications for persons treated for schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(11) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings J, Mijanovich T. Improving the management of care for high-cost Medicaid patients. Health Affairs. 2007;26(6):1643–1654. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Catty J, Dash M, Roberts C, Lockwood A, Marshall M. Use of intensive case management to reduce time in hospital in people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-regression. BMJ. 2007;335(7615):336. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39251.599259.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Rugkasa J, Molodynski A, Dawson J, Yeeles K, Vazquez-Montes M, Voysey M, Sinclair J, Priebe S. Community treatment orders for patients with psychosis (OCTET): A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60107-5. Early Online Publication, March 26, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Rudisch BE, Craw J, Thompson T, Owens DA. Predictors of missed first appointments at community mental health centers after psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(4):531–537. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar AE, Snowden LM, Ewing T. Criminal records of persons served in the public mental health system. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(1):114–120. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Leckband S, Jeste DV. Interventions to improve antipsychotic medication adherence: Review of recent literature. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;23(4):389–399. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000085413.08426.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Deegan PE. Shared decision making is an ethical imperative. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(8):1007. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas M, Gagne C, Anthony W, Chamberlin J. Implementing recovery oriented evidence based programs: Identifying the critical dimensions. Community Mental Health Journal. 2005;41(2):141–158. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-2649-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer EP, McCarthy JF, Ignacio RV, Blow FC, Barry KL, Hudson TJ, et al. Longitudinal patterns of health system retention among veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Community Mental Health Journal. 2008;44(5):321–330. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9133-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayne SM, Miller DR, Sharkansky EJ, Jackson VW, Wang F, Halanych JH, et al. Using administrative data to identify mental illness: What approach is best? American Journal of Medical Quality. 2010;25(1):42–50. doi: 10.1177/1062860609346347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Folsom DP, Lindamer L, Garcia P, et al. Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):692–699. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan MF, Gibbs LI, O’Donnell DE, Feinblatt J. New York State/New York City Mental Health-Criminal Justice Panel Report and Recommendations. Albany: New York State Office of Mental Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid. A primer. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, Koch JR, Laska EM, Leaf PJ, et al. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental Illness. Health Services Research. 2001;36(6 Pt 1):987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenbuhl J, Nossel IR, Dixon LB. Disengagement from mental health treatment among individuals with schizophrenia and strategies for facilitating connections to care: A review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35(4):696–703. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse GR, Rohland BM, Wu X. Factors associated with missed first appointments at a psychiatric clinic. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(9):1173–1176. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. A comparative survey of missed initial and follow-up appointments to psychiatric specialties in the United Kingdom. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(6):868–871. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York State Department of Health. A plan to transform the empire state’s Medicaid program. New York: New York State Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nosé M, Barbui C, Tansella M. How often do patients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment programmes? A systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(7):1149–1160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien A, Fahmy R, Singh SP. Disengagement from mental health services: A literature review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatry Epidemiology. 2009;44(7):558–568. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Bridge JA. Emergency treatment of deliberate self-harm. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(1):80–88. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven MC, Billings JC, Goldfrank LR, Manheimer ED, Gourevitch MN. Medicaid patients at high risk for frequent hospital admission: Real-time identification and remediable risks. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;86(2):230–241. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9336-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley GF. Administrative and claims records as sources of health care cost data. Medical Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S51–S55. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819c95aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Sederer LI. Changing the landscape of an urban public mental health system: The 2008 New York State/New York City Mental Health-Criminal Justice Review Panel. Journal of Urban Health. 2009;87(1):129–135. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Appel A, Donahue SA, Essock SM, Jackson CT, Karpati A, et al. Use of administrative data to identify potential service gaps for individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2011a;62(9):1094–1097. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.9.pss6209_1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Appel A, Donahue SA, Essock SM, Jackson CT, Karpati A, et al. Public-academic partnerships: Using Medicaid claims data to identify service gaps for high-need clients: The NYC Mental Health Care Monitoring Initiative. Psychiatric Services. 2011b;62(1):9–11. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.1.pss6201_0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers W. Transforming systems of care: The American Association of Community Psychiatrists Guidelines for Recovery Oriented Services. Community Mental Health Journal. 2005;41(6):757–774. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-6433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Kogan JN, Sorbero MJ, Thompson W, Hutchinson SL. Predictors of timely follow-up care among Medicaid-enrolled adults after psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(12):1563–1569. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theriot MT, Segal SP. Involvement with the criminal justice system among new clients at outpatient mental health agencies. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(2):179–185. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Demler O, Kessler RC. Adequacy of treatment for serious mental illness in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(1):92–98. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, Mechanic D. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1653–1664. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]