Abstract

Herein, we report the synthesis and structure–activity relationship of a series of chiral alkoxymethyl morpholine analogs. Our efforts have culminated in the identification of (S)-2-(((6-chloropyridin-2-yl) oxy)methyl)-4-((6-fluoro-1H-indol-3-yl)methyl)morpholine as a novel potent and selective dopamine D4 receptor antagonist with selectivity against the other dopamine receptors tested (<10% inhibition at 1 µM against D1, D2L, D2S, D3, and D5).

Keywords: Dopamine 4 receptor, Antagonist, Morpholine, L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia, Dopamine Selectivity

Dopamine (DA) is a major neurotransmitter and is the primary endogenous ligand for the dopamine receptors. Dopamine receptors are members of the Class A G-protein coupled receptors. There are five dopamine receptor subtypes which are subdivided into two families, the D1-like family and the D2-like family. The D1-like family consists of the D1 and D5 receptor subtypes which are coupled to Gs and mediate excitatory neurotransmission. The D2-family consists of three receptor subtypes (D2, D3, and D4) which are coupled to Gi/Go and mediate inhibitory neurotransmission. Of the subtypes, the dopamine D4 receptor (D4R) has received considerable attention as a potential target for pharmacological intervention due to disorders linked to dysfunction of this receptor (schizophrenia1–3, Parkinson’s disease4,5, and substance abuse6–8).

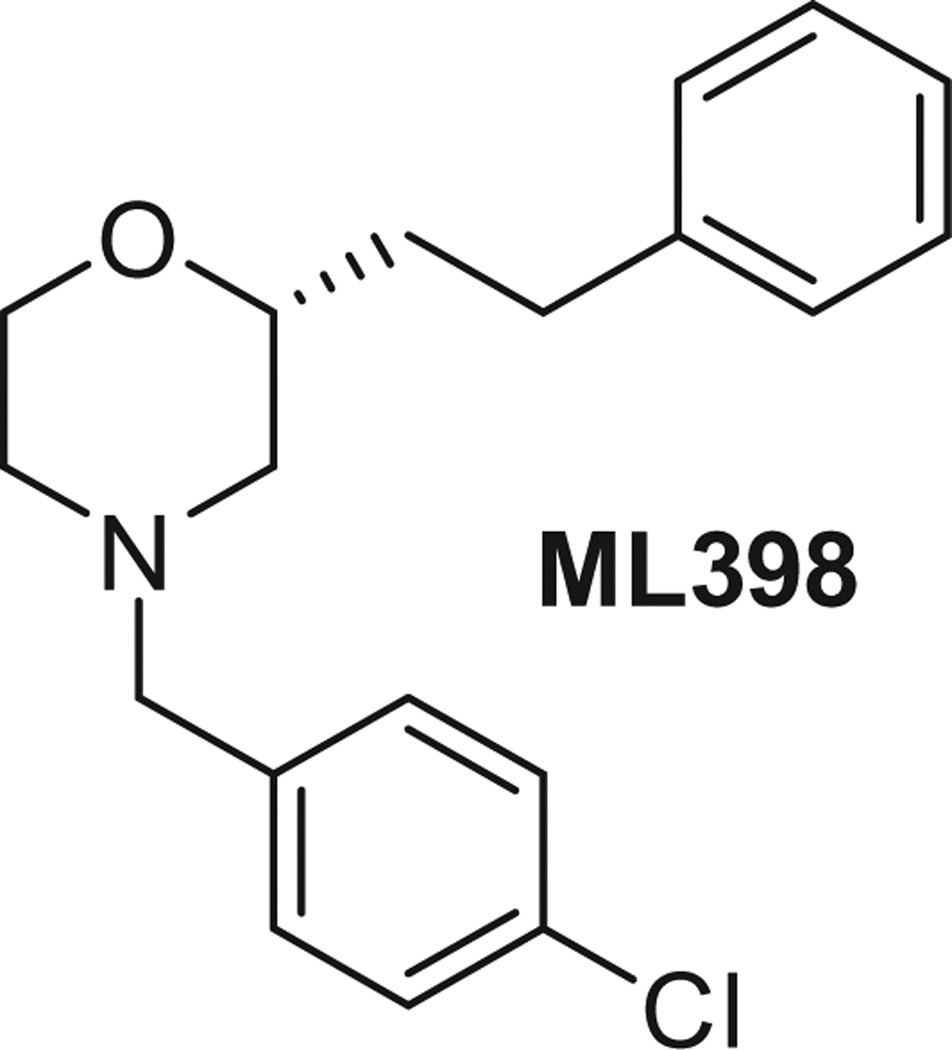

Recently, we reported on the identification of a chiral morpholine scaffold as a potent and selective D4R antagonist, ML398 (Fig. 1).9,10 ML398 was active in vivo; however, the SAR analysis was limited due to the synthetic feasibility of modification of the upper right-hand phenethyl group. Thus, we wanted to evaluate alternative linker groups in order to more fully explore the SAR around both the N-linked groups as well as moieties adjacent to the oxygen group of the morpholine.

Figure 1.

Structure of previously disclosed chiral morpholine D4 antagonist, ML398.

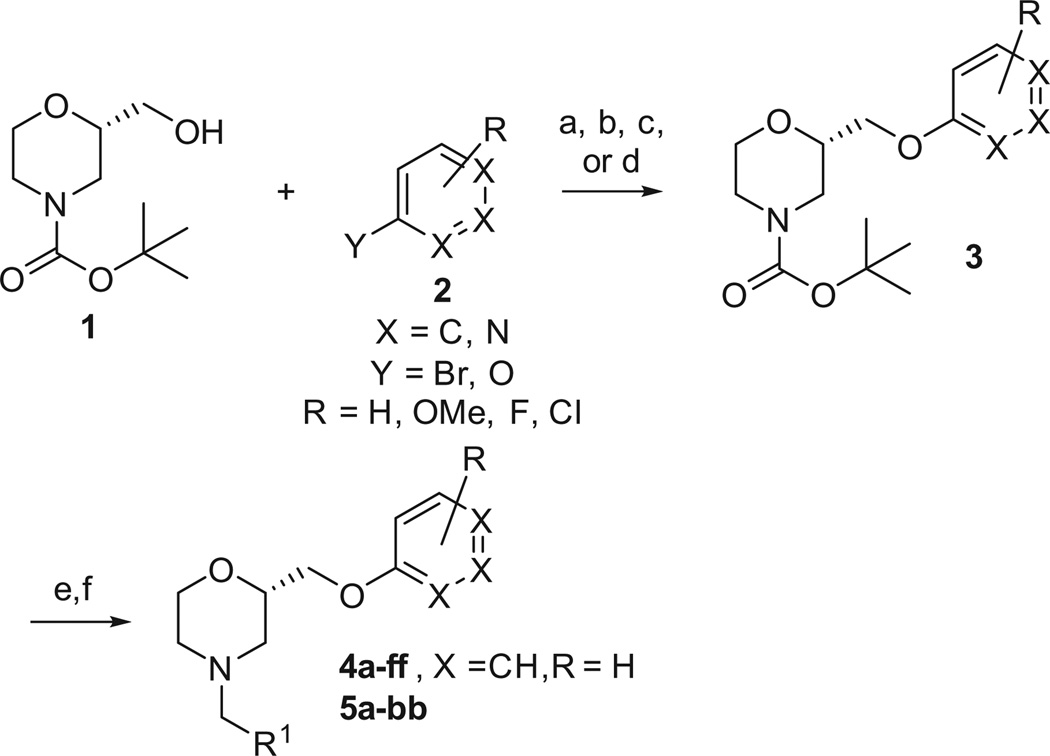

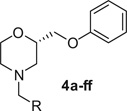

To this end, we set out to replace the ethyl linker with a hydroxymethyl group as this would allow for significant diversification of this portion of the molecule.11 In addition, as we have shown previously, the activity of the chiral morpholine scaffold resides in the (S)-enantiomer and the starting Boc-protected (S)-2-(hydroxymethyl)morpholine is commercially available. The synthetic procedure to access these compounds is shown in Scheme 1. The tert-butyl (S)-2-(hydroxymethyl)morpholine-4-carboxylate, 1, was coupled with the appropriate aryl bromide, 2, under copper mediated conditions to afford 3.12 Alternatively, the aryl ethers could be formed under Mitsunobu conditions13 (ArOH, PPh3, DIAD, µW, 180 °C) in good yield. Next, the Boc group was removed under acidic conditions and reductive amination with polymer bound CNBH3 provided the final compounds in modest overall yields.14

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) CuI, Me4Phen, Cs2CO3, toluene (14–30%); (b) ArOH, PPh3, DIAD, benzene, rt (51%); (c) ArOH, PS-PPh3, DIAD, THF, rt (21–25%); (d) ArOH, PPh3, DIAD, THF, µW, 180 °C, 5 min (62%); (e) 4 M HCl in dioxanes; (f) polymer bound CNBH3, R1CHO, acetic acid, DCM (16–42%).

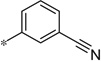

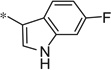

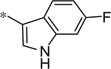

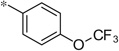

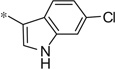

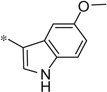

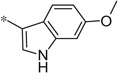

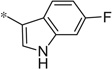

The first set of analogs that we synthesized and evaluated kept the upper right-hand portion constant as the unsubstituted phenoxy moiety and modified the southern nitrogen substituents. A key component for the design of the molecules was to lower the cLogP of the compounds since ML398 was rather lipophilic (cLogP = 5.10), with a design on potency and pharmacokinetic parameters. The 4-chlorobenzyl, 4a, direct comparator to ML398 (Ki = 36 nM) was equipotent to its predecessor compound (Ki = 42 nM) and the introduction of an ether linker led to a significant improvement (lowering) of the cLogP (5.10 vs. 3.73).10 Further substitution around the benzyl group led to a more active compound (3,4-dimethyl, 4b, Ki = 12.3 nM). Additional steric bulk was well tolerated as the naphthyl group was active as well (4d, Ki = 17.8 nM). Interestingly, the 2-substituted quinoline, 4e, was significantly less potent (Ki = 310 nM) compared to the naphthyl group. Multiple substitution patterns around the phenyl group are well tolerated (4f–4s) with a few notable exceptions. Namely, the 3-chloro-4-fluorophenyl (4f, Ki = 170 nM) and 3, 4-difluorophenyl (4h, Ki = 150 nM) were less potent than the other analogs tested. The transposed 4-chloro-3-fluorophenyl (4g, Ki = 19.1 nM) and the 3,4-dichlorophenyl (4i, Ki = 27 nM) were more active by ~10-fold, suggesting the 4-fluoro substitution is not as well tolerated. However, this is not a fully general phenomenon as the 3-methoxy-4-fluoro analog, 4m, is one of the most potent compounds in this series (Ki = 11.6 nM), along with the 3-methoxy-4-chloro compound (4p, Ki = 11.6 nM) and 4-methoxy-3-chloro (4n, Ki = 10.4 nM). As an additional confirmation of the (S)-enantiomer activity, the (R)-enantiomer of 4n was made and evaluated, and it was not active (4o, 35% inhibition at 10 µM). In addition to substituted benzyl groups in the southern portion of the molecule, heteroaryl moieties were also well tolerated. The imidazo[1,5-a]pyridine, 4u (Ki = 35 nM), was equipotent with ML398; however, the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine, 4t (Ki = 160 nM) was less potent. Moving to the 3-substituted indole compounds yielded the most active compounds in this set of analogs. The 6-chloro (4aa, Ki = 2.2 nM), 6-methoxy (4dd, Ki = 5.4 nM) and 6-fluoro (4ee, Ki = 5.2 nM) were all productive changes. The corresponding 5-substituted indole compounds were not as active (4bb and 4cc), nor was a 4-substituted analog (4ff).

Next, we turned our attention to the alkoxy substituents (R2, Table 2) in conjunction with the southern fragments (R1, Table 1). Initial evaluation utilized the 4-chlorobenzyl and 4-methoxybenzyl groups as these were shown to be potent antagonists of the D4R. The first analogs tested were 5-pyrimidine and 2-pyrimidine replacements for the phenyl group. Neither of these replacements led to active compounds; although 5a did show weak activity (76% inhibition at 10 µM), and introduction of these polar groups led to a significant lowering of the cLogP, as expected. However, removal of one of the nitrogen atoms in the 5-pyrimidine analog led to the 3-pyridine analog and resulted in significant recovery of the potency (5e, Ki = 47 nM; 5f, Ki = 59 nM). Similar removal of a nitrogen atom in the 2-pyrimidine series leaving the 2-pyridine analogs only led to modest recovery of the potency in one of the analogs (5g, Ki = 730 nM). Substituted 3- or 4-methoxy groups on the phenyl ether were comparable in activity to the unsubstituted phenethyl derivatives (5p–5r). The 3-fluoro and 4-fluoro substituted compounds were well tolerated resulting in very potent compounds (5k, Ki = 10.4 nM; 5l, Ki = 13.1 nM; 5m, Ki = 10.8 nM; 5n, Ki = 10.1 nM). Unexpectedly, the 2-halogen-6-alkoxypyridine compounds were active; unlike the 2-alkoxypyridine analogs (vide supra). In fact, combining the 6-fluoro-3-indole analog (4ee) with the 2-chloro-6-alkoxypyridine led to one of the most potent compounds from this series (5y, Ki = 3.3 nM). Lastly, two compounds in which the sulfide linker replaced the alkoxy linker were synthesized; this proved to be a fruitful change as well (5aa, Ki = 9.4 nM; 5bb, Ki = 7.4 nM).

Table 2.

Structure and D4 activity of the O- and N-linked analogs

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compd | R1 | R2 | cLogPa | IC50 (nM)b | Ki (nM)b |

| ML398 | 5.10 | 130 | 36 | ||

| 5a |  |

|

1.83 | 76%c | |

| 5b |  |

1.17 | −4%c | ||

| 5c |  |

2.33 | 31%c | ||

| 5d |  |

1.67 | 8%c | ||

| 5e |  |

2.42 | 103 | 47 | |

| 5f |  |

1.77 | 210 | 59 | |

| 5g |  |

2.83 | 2,630 | 730 | |

| 5h |  |

2.17 | 57%c | ||

| 5i |  |

2.79 | 34%c | ||

| 5j |  |

2.79 | 37%c | ||

| 5k |  |

|

3.84 | 38 | 10.4 |

| 5l |  |

3.18 | 47 | 13.1 | |

| 5m |  |

3.80 | 39 | 10.8 | |

| 5n |  |

3.80 | 37 | 10.1 | |

| 5o |  |

3.18 | 92 | 26 | |

| 5p |  |

|

3.70 | 150 | 42 |

| 5q |  |

3.04 | 380 | 110 | |

| 5r |  |

3.70 | 130 | 36 | |

| 5s |  |

|

3.41 | 100 | 28 |

| 5t |  |

3.41 | 130 | 36 | |

| 5u |  |

|

3.47 | 76 | 21 |

| 5v |  |

3.33 | 460 | 130 | |

| 5w |  |

3.30 | 260 | 73 | |

| 5x |  |

3.30 | −3%c | ||

| 5y |  |

3.99 | 11.9 | 3.3 | |

| 5z |  |

3.85 | 100 | 29 | |

| 5aa |  |

4.41 | 34 | 9.4 | |

| 5bb | 4.35 | 27 | 7.4 | ||

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental).

IC50 and Ki values were run in duplicate in a radioligand binding assay using Spiperone at EuroFins (www.EuroFins.com).

% inhibition at 10 µM.

Table 1.

Structure and D4 activity of the N-linked analogs

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | cLogP a | IC50 (nM)b | Ki (nM)b |

| ML398 | 5.10 | 130 | 36 | |

| 4a |  |

3.73 | 150 | 42 |

| 4b | 3.68 | 45 | 12.3 | |

| 4c |  |

3.08 | 160 | 44 |

| 4d | 4.40 | 64 | 17.8 | |

| 4e | 3.15 | 1110 | 310 | |

| 4f |  |

3.84 | 62 | 170 |

| 4g |  |

3.84 | 69 | 19.1 |

| 4h |  |

3.54 | 530 | 150 |

| 4i |  |

4.35 | 97 | 27 |

| 4j |  |

4.21 | 58 | 16.2 |

| 4k |  |

4.21 | 320 | 89 |

| 4l |  |

3.18 | 56 | 14.3 |

| 4m |  |

3.18 | 42 | 11.6 |

| 4n |  |

3.70 | 38 | 10.4 |

| 4o | (R)-4n | 3.70 | 35%c | |

| 4p |  |

3.70 | 42 | 11.6 |

| 4q |  |

4.48 | 180 | 51 |

| 4r |  |

3.04 | 150 | 43 |

| 4s |  |

3.75 | 58 | 16.1 |

| 4t |  |

2.89 | 590 | 160 |

| 4u |  |

3.51 | 130 | 35 |

| 4v |  |

3.73 | 65 | 18.1 |

| 4w |  |

3.77 | 130 | 37 |

| 4x | 3.83 | 260 | 72 | |

| 4y |  |

3.20 | 170 | 47 |

| 4z |  |

3.77 | 58 | 15.9 |

| 4aa |  |

4.39 | 8.0 | 2.2 |

| 4bb |  |

3.73 | 460 | 130 |

| 4cc |  |

4.39 | 130 | 37 |

| 4dd |  |

3.73 | 19.5 | 5.4 |

| 4ee |  |

3.87 | 18.9 | 5.2 |

| 4ff |  |

3.87 | 3830 | 1060 |

Calculated using Dotmatics Elemental (www.dotmatics.com/products/elemental).

IC50 and Ki values were run in duplicate in a radioligand binding assay using Spiperone at EuroFins (www.EuroFins.com).

% inhibition at 10 µM.

Having identified a number of active D4R antagonists, we next wanted to profile these compounds against the other dopamine receptors (D1, D2L, D2S, D3, and D5) (Table 3). Generally speaking, the compounds are selective against the D1-like family of receptors (D1 and D5), both the phenoxy (4) and substituted phenoxy or heteroarylalkoxy compounds (5) are selective against the D1-like family of receptors. The compounds are less selective for the D2-like family, specifically the D2S and D2L receptors. That being said, a number of compounds prove completely selective against all of the dopamine receptors (Table 3), despite high sequence homology. Notably, the 6-fluoro-3-indole compound (4ee) showed activity against both D2L and D2S (78% and 76%, respectively). However, the comparator 2-halogen-6-alkoxypyridine compounds (5u and 5y) were fully selective against all of the dopamine receptors tested. Gratifyingly, 5y is one of the most potent analogs that was made and tested. In addition, the sulfide analogs were also selective (5aa and 5bb).

Table 3.

Dopamine receptor selectivity of select compounds

| Compound | D4 (nM) | % inhibition at 10 µMa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 (%) | D2L (%) | D2S (%) | D3 (%) | D5 (%) | |||

| 4b | 12.3 | <50 | |||||

| 4l | 14.3 | <50 | 78 | 76 | <50 | ||

| 4n | 10.4 | <50 | |||||

| 4p | 11.6 | <50 | 52 | 60 | <50 | ||

| 4u | 35 | <50 | |||||

| 4v | 18.1 | <50 | |||||

| 4z | 15.9 | <50 | 64 | 64 | <50 | ||

| 4aa | 2.2 | <50 | 94 | 93 | 70 | <50 | |

| 4dd | 5.4 | <50 | 87 | 82 | 70 | <50 | |

| 4ee | 5.2 | <50 | 78 | 76 | <50 | ||

| 5k | 10.4 | <50 | 83 | 79 | 51 | <50 | |

| 5l | 13.1 | <50 | 88 | 82 | 76 | <50 | |

| 5m | 10.8 | <50 | |||||

| 5n | 10.1 | <50 | |||||

| 5u | 21 | <50 | |||||

| 5y | 3.3 | <50 | |||||

| 5aa | 9.4 | <50 | |||||

| 5bb | 7.4 | <50 | |||||

% inhibition values were run in duplicate in a radioligand binding assay at EuroFins (www.EuroFins.com).

Having identified a number of potent and selective compounds, we further profiled selected compounds in a battery of Tier 1 in vitro DMPK assays (Table 4). The intrinsic clearance (CLINT) was assessed in liver microsomes (rat and human), and many of the compounds proved to be unstable to oxidative metabolism and were predicted to display high clearance in both species.15 However, a few compounds were shown to have moderate predicted clearance, such as 4t (imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine) and 4g (3-fluoro-4-chlorophenyl), which presumably can block oxidation of the phenyl group. Utilizing an equilibrium dialysis approach, the protein binding of the compounds was evaluated in both human and rat plasma. The fraction unbound (Fu) ranged from low to moderate, and these values loosely correlated with the calculated logP of the compounds. Although it is understood that fraction unbound is a difficult parameter to SAR around, lowering cLogP within a series can tend to produce better values. As such, 4t, 4l, and 4y had the highest fraction unbound and the lowest cLogP values. Lastly, we assessed the ability of these compounds to cross the blood–brain barrier in a rodent IV cassette experiment to determine brain-to-plasma ratios (Kp).16,17 A selection of compounds is shown in Table 3, and, although the compounds show high clearance in rat, the compounds are able to cross the BBB with Kp values >2.

Table 4.

In vitro and in vivo DMPK results of select compounds

| Compound | D4 (nM) | Microsome intrinsic clearance (mL/min/kg) |

Plasma unbound fraction (Fu) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hCLINT | rCLINT | Human | Rat | ||

| 4a | 12.3 | 147 | 4518 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| 4g | 19.1 | 65.3 | 251 | 0.006 | 0.012 |

| 4i | 27 | 50.5 | 621 | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| 4j | 16.2 | 50.5 | 247 | 0.002 | 0.007 |

| 4l | 14.3 | 71.9 | 2128 | 0.031 | 0.037 |

| 4n | 10.4 | 78.7 | 1597 | 0.010 | 0.019 |

| 4p | 11.6 | 79.7 | 1505 | 0.010 | 0.025 |

| 4t | 160 | 17.3 | 154 | 0.057 | 0.215 |

| 4y | 47 | 60.5 | 433 | 0.039 | 0.074 |

| 4z | 15.9 | 135 | 3137 | 0.035 | 0.069 |

| 4aa | 2.2 | 46.7 | 614 | 0.006 | 0.010 |

| 4dd | 5.4 | 31.6 | 184 | 0.037 | 0.075 |

| 4ee | 5.2 | 71.1 | 1686 | 0.017 | 0.047 |

| 5m | 10.8 | 93.0 | 1499 | 0.006 | 0.013 |

| 5n | 10.1 | 68.9 | 1774 | 0.011 | 0.014 |

| 5u | 21 | 101 | 4010 | 0.009 | 0.015 |

| 5y | 3.3 | 230 | 4195 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| 5z | 29 | 98.2 | 5313 | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| 5aa | 9.4 | 122 | 3217 | 0.008 | 0.005 |

| 5bb | 7.4 | 366 | 6436 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Rodent IV cassette (0.25 mg/kg, 0.25 h) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma (ng/mL) | Brain (ng/g) | Kp | |

| 4a | 42.5 | 197 | 4.62 |

| 4l | 14.7 | 108 | 7.38 |

| 4y | 37.3 | 83.1 | 2.23 |

| 4aa | 74.8 | 246 | 3.29 |

| 5aa | 26.1 | 131 | 5.03 |

| 5bb | 23.1 | 132 | 5.73 |

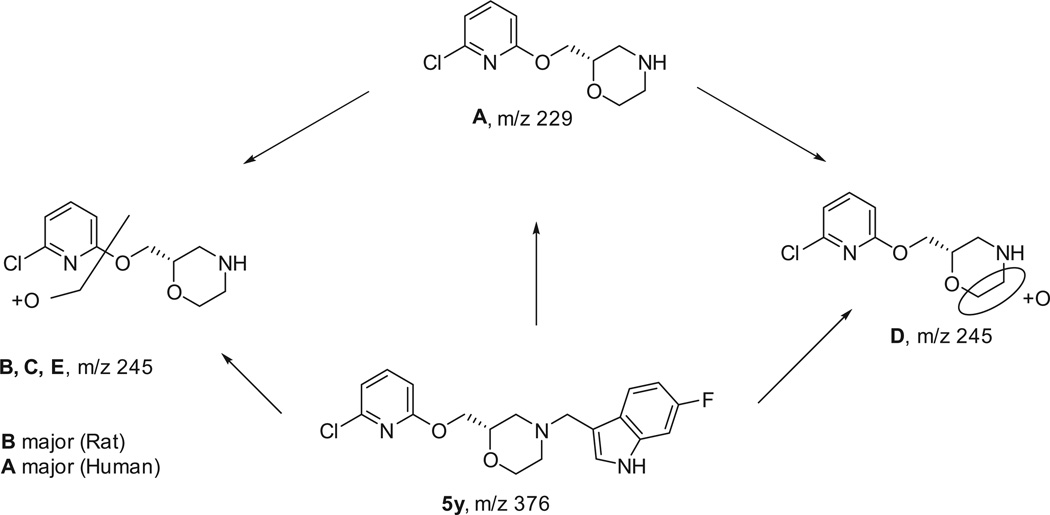

In order to better understand the nature of the instability in liver microsomes in both human and rat, we analyzed 5y in a metabolic soft-spot experiment (Q2 Solutions, www.q2labsolutions.com). 5y was highly metabolized in both rat and human liver microsomal samples in the presence of NADPH. Compound B was the major metabolite in the rat microsomes (N-dealkylation + oxidation), and the major metabolite in human microsomes was Compound A (N-dealkylation). The parent compound, 5y, was observed in the rat and human samples in the absence of NADPH. Thus, further analog work will concentrate on blocking the N-dealkylation mechanism of metabolism (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Metabolic soft-spot analysis of 5y in liver microsomes.

In conclusion, we have further elaborated our initial D4R antagonist, ML398, by changing the ethyl linker to a hydroxymethyl linker on the chiral morpholine scaffold. A number of compounds are very potent (D4 Ki <20 nM) with excellent selectivity against the other dopamine receptors. Notably, compounds 5y, 5aa, and 5bb were shown to have D4 Kis <10 nM and be completely selective against the other dopamine receptors (Kis >10 µM, ie., >1000-fold selectivity). Compounds 4ee and 5y are intriguing molecules as they contain molecular handles and possess desirable physicochemical properties (cLogP) for potential radioligand development. Many of the compounds identified were highly cleared in both human and rat liver microsomes, and we have shown that N-dealkylation is a major contributor to the instability. Lastly, compounds from this scaffold class are highly brain penetrant as assessed in a rodent IV cassette experiment to determine brain-to-plasma ratios (Kp values >2). Further optimization and in vivo behavioral efficacy experiments will be disclosed in due course.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research for research support for CRH (MJFF Grant ID: 10000) and Jarrett Foster, Sichen Chang, and Xiaoyan Zhan for their contributions to the DMPK screening tier.

References and notes

- 1.Lahti RA, Roberts RC, Cochrane EV, Primus RJ, Gallager DW, Conley RR, Tamminga CA. Mol. Psychiatry. 1998;3:528. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanyal S, Van Tol HHM. J. Psychiatry Res. 1997;31:219. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(96)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bristow LJ, Kramer MS, Kulagowski J, Patel S, Ragan CI, Seabrook GR. Trends Pharm. Sci. 1997;18:186. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huot P, Johnston TH, Koprich JB, Espinosa MC, Reyes MG, Fox SH, Brotchie JM. Behav. Pharmacol. 2015;26:101. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huot P, Johnston TH, Koprich JB, Aman A, Fox SH, Brotchie JM. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012;342:576. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.195693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Ciano P, Grandy DK, Le Foll B. Adv. Pharmacol. 2014;69:301. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00008-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutt DJ, Lingford-Hughes A, Erritzoe D, Stokes PRA. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015;16:305. doi: 10.1038/nrn3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Reilly MC, Lindsley CW. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2910. doi: 10.1021/ol301203z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry CB, Bubser M, Jones CK, Hayes JP, Wepy JA, Locuson C, Daniels JS, Lindsley CW, Hopkins CR. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:1060. doi: 10.1021/ml500267c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Audouze K, Nielsen EØ, Peters D. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:3089. doi: 10.1021/jm031111m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman RA, Shafir A, Lichtor PA, Buchwald SL. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:284. doi: 10.1021/jo702024p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitsunobu O. Synthesis. 1981:1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Experimental Procedure for the synthesis of 5y: tert-Butyl (S)-2-(hydroxymethyl)morpholine-4-carboxylate, 1, (110.0 mg; 0.507 mmol) and DMF (2.5 mL) were added to a vial equipped with a stir bar. The mixture was cooled to 0 °C and then NaH (24.3 mg; 0.608 mmol) was added and the mixture was stirred until fully dissolved. Next, 2-chloro-6-fluoropyridine (133.3 mg; 1.013 mmol) was added and then the reaction mixture was warmed to 60 °C. After 90 min, the reaction was cooled to rt and CH2Cl2 was added along with 5% LiCl in H2O. The layers were separated and the organic layer was dried (MgSO4) and collected and concentrated. The crude product was purified via flash column chromatography (5–30% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide the N-Boc product. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.45 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.84 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.64 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.28 (2H, d, J = 4.9 Hz), 3.87 (2H, d, J = 10.6 Hz), 3.72–3.69 (2H, m), 3.51 (1H, dt, J = 11.6, 2.7 Hz), 2.92 (1H, t, J = 22.3 Hz), 2.76 (1H, s), 1.40 (9H, s). The product was treated with 2.0 mL of 4 M HCl/dioxanes and stirred at rt for 30 min. At this time, the mixture was concentrated and the material was converted to the free base via an SCX column. The material was added to a microwave vial along with MP-CNBH3 (88.2 mg; 2.28 mmol/g polymer; 0.201 mmol), acetic acid (23.0 µL; 0.402 mmol) and CH2Cl2 (1.0 mL) and then heated in a microwave at 110 °C for 7 min. The reaction mixture was cooled to rt, filtered and washed with CH2Cl2 and purified by flash column chromatography (5–30% EtOAc/hexanes) leaving the desired compound (12.0 mg; 0.0320 mmol; 42%). [α]D +18.84 (c 1.0, CH3OH); LCMS: RT = 0.786 min, >98% @ 254 nm, m/z = 376.2 [M+H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.01 (1H, br s), 7.60 (1H, dd, J = 8.7, 5.5 Hz), 7.42 (1H, t, J = 7.7 Hz), 7.03 (1H, d, J = 1.4 Hz), 6.97 (1H, dd, J = 9.6, 2.0 Hz), 6.84–6.79 (1H, m), 6.63 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), 4.24–4.22 (2H, m), 3.86 (2H, br d, J = 10.9 Hz), 3.68–3.65 (1H, m), 2.80 (1H, d, J = 11.1 Hz), 2.68 (1H, d, J = 11.4 Hz), 2.17 (1H, dt, J = 11.4, 3.2 Hz), 2.00 (1H, t, J = 10.6 Hz); 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 163.2, 161.3, 158.9, 148.1, 140.6, 136.3, 124.3, 123.8, 120.5, 116.5, 109.5, 108.5, 97.5, 74.1, 67.6, 66.9, 54.8, 54.0, 52.9.

- 15.Obach RS. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1999;27:1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith NF, Raynaud FI, Workman P. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007;6:428. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bridges TM, Morrison RD, Byers FW, Luo S, Daniels JS. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2014:2. doi: 10.1002/prp2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]