Keywords: nerve regeneration, mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease, neuroimaging, resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging, brain network, acupuncture, Tiaoshen Yizhi, neural regeneration

Abstract

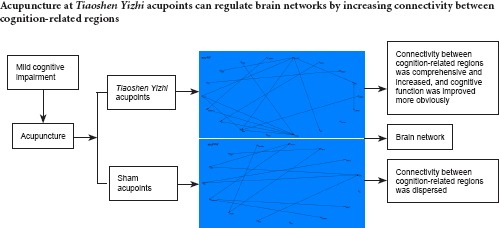

Functional magnetic resonance imaging has been widely used to investigate the effects of acupuncture on neural activity. However, most functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have focused on acute changes in brain activation induced by acupuncture. Thus, the time course of the therapeutic effects of acupuncture remains unclear. In this study, 32 patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment were randomly divided into two groups, where they received either Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture or sham acupoint acupuncture. The needles were either twirled at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints, including Sishencong (EX-HN1), Yintang (EX-HN3), Neiguan (PC6), Taixi (KI3), Fenglong (ST40), and Taichong (LR3), or at related sham acupoints at a depth of approximately 15 mm, an angle of ± 60°, and a rate of approximately 120 times per minute. Acupuncture was conducted for 4 consecutive weeks, five times per week, on weekdays. Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging indicated that connections between cognition-related regions such as the insula, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, inferior parietal lobule, and anterior cingulate cortex increased after acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints. The insula, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus acted as central brain hubs. Patients in the Tiaoshen Yizhi group exhibited improved cognitive performance after acupuncture. In the sham acupoint acupuncture group, connections between brain regions were dispersed, and we found no differences in cognitive function following the treatment. These results indicate that acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints can regulate brain networks by increasing connectivity between cognition-related regions, thereby improving cognitive function in patients with mild cognitive impairment.

Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has received increasing attention in the field of cognitive neuroscience. MCI is thought to correspond to an intermediate state between normal aging and Alzheimer's disease (AD), which is the most common form of dementia globally (Petersen et al., 1999; Farlow, 2009). Research has shown that the incidence of dementia increases greatly with age (Chen et al., 2013). Although dementia is a leading cause of death in the United States, it is under-recognized as a terminal illness. The median survival value has been reported as 478 days, with a 24.7% probability of death within 6 months (Hsu and Kao, 2010). Multivariable analyses have shown that dementia and cognitive impairment are very strongly and independently associated with other chronic health disorders (Sousa et al., 2009). Therefore, it may be advantageous to focus on preventing the progression of MCI rather than concentrating on AD. However, no pharmaceutical treatments have been found to delay the long-term progression of MCI and conversion to dementia (Farlow, 2009; Sabat, 2009). An increasing number of clinical reports have indicated that acupuncture, a therapy with minimal side effects compared with drug therapy, has promise in treating individuals with MCI (Jiang et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). However, the mechanisms underlying the effects of acupuncture in terms of brain networks involving MCI are still unclear (Bai et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014). Recently, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become available for the immediate, dynamic, and non-invasive investigation of the effects of acupuncture on MCI. At present, fMRI has become a primary technique for exploring the underlying mechanisms of acupuncture (Chen et al., 2014).

Previous fMRI studies that reported no effects of acupuncture treatment generally used a block-design fMRI paradigm with “on-off” specifications (Hui et al., 2000, 2005; Fang et al., 2009; Kong et al., 2009). However, abundant clinical reports and traditional Chinese medicine theory suggest that the effects of acupuncture have time-varying characteristics, i.e., the effects may last for a long time period, even after the acupuncture needles are removed (Bai et al., 2009b, c, 2010; Fang et al., 2009). Several recent studies have addressed the sustained effects of acupuncture, specifically post-acupuncture resting-state networks, using functional connectivity analysis, which is a type of undirected graphical analysis of temporal correlations between different brain regions (Zhong et al., 2012). Additionally, a number of neuroimaging studies have indicated that the primary effects of acupuncture are mediated by the central nervous system (Chen et al., 2012), and that acupuncture can activate certain cognition-related brain regions in AD and MCI patients. Other studies have demonstrated the specificity of acupuncture using different perspectives. For example, Chen et al. (2008) compared verum acupuncture with sham acupuncture at the Shenmen (HT7) acupoint and found that true acupuncture elicited significant activation in cognition-related brain regions. This suggests that acupuncture can activate resting brain networks, which include anti-nociceptive, memory, and affective brain regions. However, most of the participants involved in the above-mentioned studies were healthy. According to traditional Chinese medicine theory, the effects of acupoint acupuncture are more easily observed in people who are ill or suffering (Chen et al., 2014). Thus, it may be more effective to explore the effects of acupuncture on brain function in a patient sample. In addition, most fMRI studies compared brain activity patterns induced by the acute effects of acupuncture at acupoint vs. non-acupoint positions, or between different acupoints (Jiao et al., 2011). Similarly, some previous studies examined activation in various brain areas without examining connectivity (Chen et al., 2013). Recently, it has been possible to examine the modulation of brain networks by acupuncture using resting-state fMRI (Chen et al., 2012).

Acupuncture has been found to activate cognition-related brain regions, but previous studies have not explored other forms of modulation. Based on the cognitive brain network, we hypothesize that acupuncture can improve cognitive function by regulating the connectivity between cognition-related regions. In this study, we sought to examine acupuncture-related changes in brain network connectivity and cognitive function, as well as the relationship between these two variables.

Participants and Methods

Participants

We assessed cognitive function in a group of community-dwelling individuals aged 55–70 years. Patients with MCI were selected according to the results of a cognitive assessment. Eligible participants were selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 32 participants (16 males and 16 females, aged 55–70 years old) were enrolled in the study.

The study inclusion criteria were: (1) adherence to the diagnostic criteria for MCI (Petersen, 2004); (2) 55–70 years of age; (3) an education level greater than middle school; (4) mentally and physically healthy; (5) a body mass index of 20–24; (6) right-handed; and (7) provided informed consent.

The criteria for amnestic MCI were: (1) complaints of memory impairment from patient or family members; (2) memory assessment scores (Petersen, 2004) 1.5 standard deviations lower than those obtained by age- and education-matched normal controls; (3) grade 2–3 on the Global Deterioration Scale (Petersen, 2004) or a Clinical Dementia Rating score (Petersen, 2004) of 0.5; (4) normal general cognitive function; (5) normal activities of daily living; (6) no impaired brain function caused by mental or physical diseases.

The study exclusion criteria were: (1) severe visual or hearing disorders, or aphasia; (2) presence of metal within the body, i.e., from surgery or tattoos; (3) unable to undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) due to fear or other factors; (4) a disease focus or suspected focus in the brain; (5) suspected pathology based on blood examination or electrocardiogram; (6) a history of mental disease or epilepsy; (7) a history of alcohol or drug abuse; (8) pre-menopausal women.

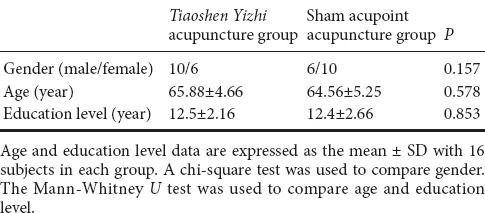

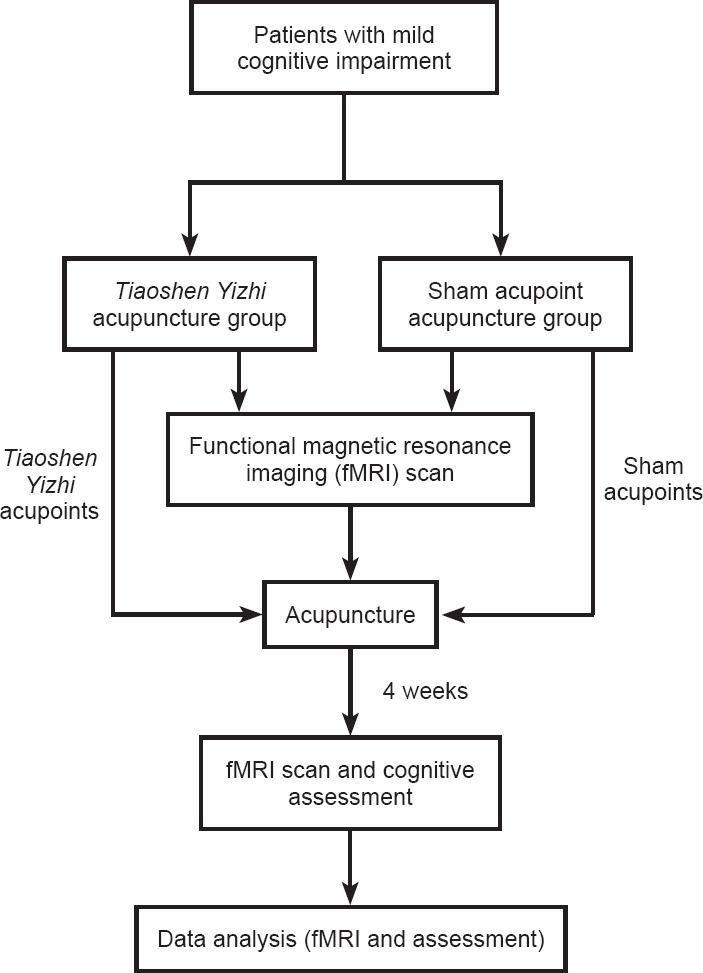

Patients were randomly divided into two groups, namely a Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture group (n = 16) and a sham acupoint acupuncture group (n = 16). Demographic information did not significantly differ between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 1). All protocols were approved by a local subcommittee for human studies in Shenzhen Baoan Hospital, Southern Medical University, China, and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the study procedure.

Table 1.

Baseline comparison of patients with mild cognitive impairment prior to Tiaoshen Yizhi or sham acupoint acupuncture

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study procedure.

Cognitive assessment

We assessed cognition in each subject before and after 4 weeks of acupuncture. We assessed cognition using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), digit-symbol substitution test, digit-span test, and the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) (Jia et al., 2011). We conducted each test individually in the order listed above. During the assessments, we took measures to ensure that no distractions would occur, and assessments were completed by the same researcher (who had experience with the scale).

Acupuncture

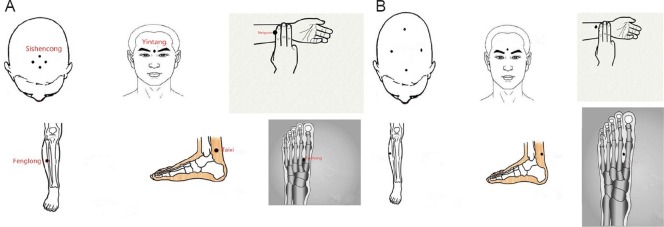

We used the following acupoints in the Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture group: Sishencong (EX-HN1), Yintang (EX-HN3), Neiguan (PC6), Taixi (KI3), Fenglong (ST40), and Taichong (LR3) (Figure 2A). Each needle was inserted at a depth of approximately 15 mm. During stimulation, each needle (Hwato silver needle with a diameter of 0.35 mm and length of 25 mm, Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory, China) was manually twirled at an angle of ± 60° and a rate of approximately 120 times per minute. For the sham acupoint acupuncture group, we used non-acupoints located beside the real acupoints used for the Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoint acupuncture group (Figure 2B). Acupuncture was conducted five times a week, on weekdays, for 4 consecutive weeks. A single acupuncturist, who had more than 10 years of professional experience, administered the acupuncture.

Figure 2.

Acupoints used in the Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture group (A) and sham acupoint acupuncture group (B).

fMRI design

For each subject, we collected a MRI scan before and after the 4-week acupuncture program. All scans were performed using a 3.0T MRI scanner (Siemens, Shenzhen, China). Brain and resting-state functional imaging commenced after head fixation. Precisely, axial anatomic imaging was performed using a gradient-echo echo planar imaging sequence. Data were collected at the level parallel to a line drawn between the anterior and posterior commissure, and for the area covering the entire brain. The parameters were as follows: repetition time = 2 seconds, echo time = 30 ms, field of view = 22 mm × 22 cm, flip angle = 77°, matrix = 64 × 64, slice thickness = 4 mm, slice interval = 1 mm, for a total of 30 slices. For anatomic imaging, we used a T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence. Functional images were obtained at the same orientation as the anatomic images. The parameters were as follows: repetition time = 2.1 seconds, echo time = 4.6 ms, matrix = 256 × 256, field of view = 230 mm × 230 cm, flip angle = 8°, slice thickness = 1 mm. All participants were asked to remain relaxed and still without engaging in any mental tasks. According to the participant reactions after scanning, they had remained immobile and awake during the process.

fMRI data analysis

Preprocessing was performed using Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM8, http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). Initially, the first five time points were discarded due to the potential instability of the initial MRI signal (Sun et al., 2012). The image data underwent slice-timing correction and realignment for head motions using least-squares minimization. None of the participants made any head movements exceeding 1 mm on any axis or head rotations greater than one degree. A mean image created from the realigned volumes was co-registered with each subject's individual structural T1-weighted volume image (Feng et al., 2011). The images were normalized to the standard echo planar imaging template and re-sampled to a voxel size of 2 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm (Demirci et al., 2009). Subsequently, these data were filtered using a bandpass filter (0.01–0.08 Hz) to reduce the effect of low-frequency drift and high-frequency noise (Greicius et al., 2003; Jiao et al., 2011). Finally, the images were smoothed spatially using a 6 mm full-width-at-half maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel.

Each region of interest (ROI) was correlated to every other ROI to obtain a 39 × 39 matrix of correlation coefficients, and the mean functional connectivity matrix (FC matrix) was computed by averaging all the correlation matrices. We then created an unweighted binary graph in which the nodes were connected if the correlation coefficients exceeded the threshold (Fisher's r-to-z transformation was applied). For direct analysis of the brain network, single nodes were deleted according to the artificial settings. To characterize the interregional relationships between our defined ROIs, we used graph theory to define a graph as a set of nodes and edges (Dosenbach et al., 2007). We used the correlation method of estimation described by Salvador et al. (2005) to calculate the interregional partial correlations and test for non-zero partial correlations to construct the brain networks. Given a set of random variables, the partial correlation matrix is a symmetric matrix in which each off-diagonal element is the correlation coefficient between a pair of variables after partialling out (conditioning under normality) the contributions to the pairwise correlation of all other variables included in the dataset. To estimate the partial correlation matrix, we used a method that includes a fairly general assumption that the observations have multivariate normality. However, our data included a series of time points and therefore we needed to assume jointly Gaussian stationary multivariate stochastic processes. The partial correlation matrices individually obtained from each participant were averaged to estimate the group mean interregional functional connectivity matrix.

Statistical analysis

Measurement data are expressed as the mean ± SD. SPSS 22.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA)was used for clinical data analysis. We used the chi-square test, two-sample t-test, and Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons between groups. The paired-sample t-test and Wilcoxon signed rank test were used for within-group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of acupuncture on cognitive assessment in MCI patients

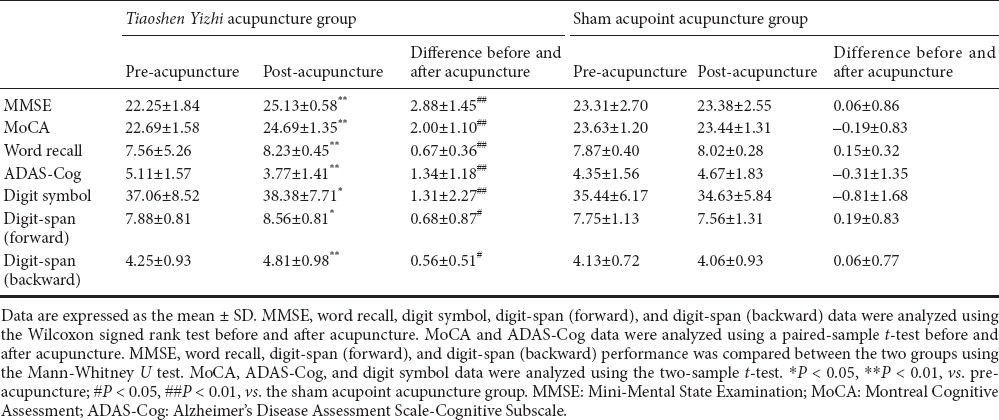

Prior to acupuncture, scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), MoCA, digit-symbol task, digit-span task, and ADAS-Cog did not significantly differ between the two groups (P > 0.05). After 4 weeks of acupuncture, scores increased on all scales in the Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture group, and improvement in the ADAS-Cog was reflected in the word recall task (P < 0.05, vs. before treatment). In the sham acupoint acupuncture group, the scores did not significantly differ before vs. after acupuncture (P > 0.05). After treatment, the scores obtained by the two groups were significantly different (P < 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of acupuncture on cognitive performance in patients with mild cognitive impairment

Resting brain networks following acupuncture

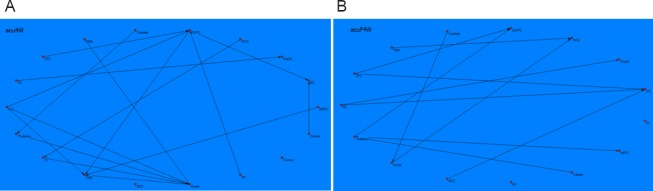

Following Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture in MCI patients, the brain network graph showed that the insula, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus acted as central hubs. The insula received causal inflows from most nodes in the brain network, including the thalamus, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex, and primary somatosensory cortex. The hippocampus received causal inflows from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex received causal inflows from the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and primary motor cortex. Additionally, the inferior parietal lobule received causal inflows from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and culmen. The precuneus received causal inflows from the fusiform gyrus, the thalamus received causal inflows from the caudate, the supplementary motor area received causal inflows from the insula, and the somatosensory cortex received causal inflows from the middle temporal gyrus (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Brian network revealed by resting-state fMRI following acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints and sham acupoints.

The connectivity patterns of the resting brain networks are described as directed graphs. The arrow direction of each connecting line represents the direction of the causal influence. Only significant effective connectivity (P < 0.05) is presented in the graphs. (A) Brain network revealed by resting-state fMRI following acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints. The graph shows comprehensive connections between brain regions, mainly connecting the insula, DLPFC, HIPP, thalamus, IPL, and ACC. The insula, DLPFC, and HIPP acted as central hubs. (B) Brain network revealed by resting-state fMRI following acupuncture at sham acupoints. The connections between brain regions were noncohesive with respect to those observed after acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints. fMRI: Functional magnetic resonance imaging; DLPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; HIPP: hippocampus; IPL: inferior parietal lobule; ACC: anterior cingulate cortex; FG: fusiform gyrus; OFC: orbitofrontal cortex; MTG: middle temporal gyrus; PreCN: precuneus; MPFC: medial prefrontal cortex; HYPO: hypothalamus; SMA: supplementary motor area; M1: primary motor cortex; MCC: middle cingulate cortex; SI: primary somatosensory cortex.

Following sham acupuncture, the inferior parietal lobule, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and middle temporal gyrus acted as central hubs. The inferior parietal lobule received causal inflows from the orbitofrontal cortex, the middle cingulate cortex, and the fusiform gyrus. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex received causal inflows from the thalamus and orbitofrontal cortex. The middle temporal gyrus received causal inflows from the insula and hypothalamus. The precuneus received causal inflows from fusiform gyrus, the medial prefrontal cortex received causal inflows from thalamus, and the insula received causal inflows from caudate. Moreover, several areas, such as the primary motor cortex and somatosensory cortex, had no connections with other regions (Figure 3B).

Discussion

AD, as a progressive neural degenerative disease, is irreversible and can lead to disability in elderly people (Triaca and Calissano, 2016; Shimada et al., 2016). MCI is the preclinical state of AD, and patients with MCI are at higher risk of developing AD compared with those without MCI (Lauterbach, 2016). Thus, early interventions for MCI are vitally important. However, no drugs have been found to reliably delay the progression of AD or MCI for long periods of time (Farlow, 2009; Petersen et al., 2014). In the past decades, traditional Chinese medicine has become increasingly prevalent in the treatment of MCI. The Tiaoshen Yizhi method of acupuncture, which acts on body meridians, has been frequently adopted because it has few side effects compared with pharmaceutical medicine, and is thought to be effective. Previous research has shown that acupuncture at a single cognition-related acupoint can induce activation in cognitive brain regions (Zhou et al., 2013; Leung et al., 2015). Therefore, Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints should have an impact on cognitive impairment.

fMRI studies of MCI have shown that brain networks may be injured even when there are no pathologic changes in the brain structures of MCI patients. The human brain can be thought of as a “small world” network with high differentiation, high integration, high convergence, and short path lengths, which can form an optimally connected structure to enable high-efficiency information transmission, such as that involved in the connectivity between brain regions (Salvador et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2013). The “small world” brain network properties of MCI and AD patients may be seriously damaged (He et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2014). For instance, MCI patients exhibit reduced connection strength and efficiency of resting-state functional brain networks, as well as the loss of default network integration (Drzezga et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013). Indeed, abnormal functional connections have been identified in the brain regions of MCI patients (Delbeuck et al., 2003), indicating that pathologic changes have occurred in brain networks of these patients. fMRI may enable the prediction of future conversion from MCI to AD (Nakata et al., 2008). Therefore, studying changes in brain networks may assist in the early diagnosis and treatment of MCI.

Several fMRI studies that adopted acupuncture in the treatment of cognitive deficits were limited in that they focused on the acute effects of acupuncture, and few studies have assessed the modulation of brain networks by acupuncture. In MCI, several functional regions may be affected, along with abnormal connections between regions, resulting in cognitive impairment. Increasing evidence from structural and functional MRI studies has suggested that AD and MCI may target specific brain networks (deToledo-Morrell et al., 2004). Brain network connections and nodal attributes are also abnormal in MCI patients (Xiang et al., 2013). Thus, we used resting-state fMRI to examine changes in brain networks after 4 weeks of acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints in MCI patients, and to examine the relationship between post-acupuncture changes in brain networks and improved cognitive function.

Our brain network graph from resting-state fMRI following Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture indicated increased and comprehensive connections between a number of brain regions, mainly the insula, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, inferior parietal lobule, anterior cingulate cortex, and primary somatosensory cortex. The insula had the most connections with other regions in the brain network, including the thalamus, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex, and primary somatosensory cortex. A meta-analyses of 1,768 functional neuroimaging experiments revealed four functionally distinct regions in the human insula that map to the cognitive network of the brain: the social-emotional, sensorimotor, and olfactory-gustatory regions (Kurth et al., 2010). An abnormal insula functional network is associated with episodic memory decline in amnestic MCI (Xie et al., 2012). Emotional awareness is engendered in the right anterior insula (Chen et al., 2012). One study indicated that decreased connectivity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may be the basis of cognitive impairment in MCI (Liang et al., 2011). The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex plays a role in sustaining attention and working memory (Lie et al., 2006; Hare et al., 2009). Lesions in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex can lead to impaired short-term memory and difficulty inhibiting behavioral responses (Petrides and Pandya, 1999). In addition, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has recently been implicated in self-control (Hare et al., 2009). Inhibition of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex could modulate excitability in a bilateral network of brain regions, thus restoring an adaptive equilibrium in MCI patients (Turriziani et al., 2012). One study showed abnormalities in hippocampal connectivity in MCI patients (Bai et al., 2009a, 2010; Xie et al., 2013). Functional results indicated that cortical activation was reduced in the default-mode network for MCI patients, compared with age- and education-matched healthy elderly controls (De Vogelaere et al., 2012). The hippocampus plays a key role in a distributed network supporting memory encoding, episodic memory, and retrieval, and it is the first cognition-related region that exhibits pathologic changes (Moser and Moser, 1998). The anterior cingulate cortex is part of the cerebral limbic system, which plays an important role in conflict monitoring, intensive learning, and error detection (Stevens et al., 2011). The anterior cingulate cortex is also associated with attention and executive function (Lie et al., 2006). The thalamus is functionally connected to the hippocampus, as part of the extended hippocampal system (Stein et al., 2000). The specialization of cortical areas in the mesio-temporal lobe, i.e., involvement in recollection and familiarity processes, may also extend to discrete regions of the thalamus (Carlesimo et al., 2011). MCI patients exhibit decreased functional connectivity between the left thalamus and a set of regions, but increased connectivity between the left and right thalamus (Wang et al., 2012). AD patients exhibit a reduced connection between the thalamus and the brain default-mode network. Further, the connection strength appears to correspond to MMSE scores, as well as immediate and delay word recall.

The connections between brain regions in the sham acupoint acupuncture group were remarkably different from those in the Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture group. Moreover, connections were significantly noncohesive. They were dispersive and did not centralize in the cognitive-related regions. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal lobule, and middle temporal gyrus had more connections with other regions than with one another.

The brain networks revealed via resting-state fMRI in the two groups illustrated that Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture elicited more brain connections compared with sham acupuncture. Moreover, in the Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture group, the brain connections linked regions correlated more strongly with cognition, while those in the sham acupuncture group were more widely dispersed. Therefore, our results indicate that increased connections between cognition-related brain regions following Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture may correspond to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture for treatment of MCI. Acupuncture has shown promise for treating chronic pain and other disorders by mobilizing the neurophysiological system to modulate multisystem functions (Bai et al., 2009b). Our findings coincide with this concept.

Previous cognition-related studies of acupuncture have mainly documented the activation of specific cognitive regions. Nevertheless, interaction between brain regions is vital for general cognitive function. Increased connectivity between cognitive regions can strengthen such interactions.

Our clinical cognitive assessment showed that, in the Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture group, MMSE, MoCA, digit-symbol, digit-span, ADA-Cog, and word recall performance all increased remarkably, while scores did not increase in the sham acupoint acupuncture group. MMSE and MoCA are used to measure cognitive function. The digit-symbol and digit-span tasks mainly reflect attention and working memory. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, right precuneus, and medial parietal lobule are associated with working memory (Owen et al., 2005). The frontal lobe and anterior cingulate cortex are related to attention. We found reduced connections between the hippocampus and a number of regions, including the right frontal lobe, bilateral temporal lobe, and bilateral insula. Impaired hippocampal connectivity is associated with cognitive decline (Wang et al., 2011). Activity in the caudate was positively correlated with MoCA scores. As mentioned, acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints led to increased connections between the hippocampus and insula, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and precuneus, and insula and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. These last two regions are cognition-related and are connected to additional structures including the anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, and inferior parietal lobule, among others. Some of the above-mentioned regions associated with executive function and memory exhibited activity that was correlated with cognitive performance. Thus, our cognitive assessment scores and brain network results appear to be highly consistent. As mentioned above, brain network connections were noncohesive after acupuncture at sham acupoints, and we found no increased connections between cognition-related regions. This was consistent with the lack of improvement in cognitive performance. These data indicate that Tiaoshen Yizhi acupuncture could improve cognitive function in MCI patients.

Studies have suggested that acupuncture can have different effects, as revealed via fMRI, under pathological and physiological states (Li et al., 2015). According to traditional Chinese medicine theory, the effects of acupoint acupuncture are best observed in people who are experiencing a pathological imbalance (Chen et al., 2014). Indeed, previous studies have shown that acupuncture plays a homeostatic role, and thus, that it may have a greater effect on patients with a pathological imbalance compared with healthy controls (Kaptchuk, 2002; Feng et al., 2012). In addition, Chen et al. (2014) demonstrated that differential activation resulting from verum or sham acupuncture may be attributed to the more varied and stronger sensations evoked by verum acupuncture. Therefore, acupuncture at verum acupoints may induce more brain network changes, which could improve cognitive function in MCI patients. This could account for the differences in results between acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints vs. sham acupoints.

Our study had several limitations. We observed differences in cognitive function and brain networks between the two groups after 4 weeks of acupuncture. However, with a longer duration of therapy and a longer follow-up period, it would have been possible to observe the persistence of the effect. This may be a topic for future research. Besides, as some participants dropped out in the research, the sample size was not large enough. This may lead to result bias for the results. In future studies, we will enlarge sample size.

Conclusions

Resting-state fMRI and cognitive assessments indicated the efficacy of acupuncture at Tiaoshen Yizhi acupoints in MCI patients. Changes in brain networks manifested as an increase in connectivity between multiple brain regions. This confirms our hypothesis that acupuncture can improve cognitive function by regulating the connectivities between cognition-related regions, and provides a new direction for cognitive research.

Acupuncture appears to have a modulatory effect on brain networks, thus improving cognitive function in MCI patients. As it has minimal side effects, acupuncture should be applied generally in the clinic for treatment of cognitive impairment.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 81173354; a grant from the Science and Technology Plan Project of Guangdong Province of China, No. 2013B021800099; a grant from the Science and Technology Plan Project of Shenzhen City of China, No. JCYJ20150402152005642.

Declaration of patient consent: The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Plagiarism check: This paper was screened twice using CrossCheck to verify originality before publication.

Peer review: This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

Copyedited by Koke S, Stow A, Yu J, Li CH, Qiu Y, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- Bai F, Zhang Z, Watson DR, Yu H, Shi Y, Yuan Y, Zang Y, Zhu C, Qian Y. Abnormal functional connectivity of hippocampus during episodic memory retrieval processing network in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Biol Psychiatry. 2009a;65:951–958. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Qin W, Tian J, Dong M, Pan X, Chen P, Dai J, Yang W, Liu Y. Acupuncture modulates spontaneous activities in the anticorrelated resting brain networks. Brain Res. 2009b;1279:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Yan H, Li L, Qin W, Chen P, Liu P, Gong Q, Liu Y, Tian J. Neural specificity of acupuncture stimulation at pericardium 6: evidence from an FMRI study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31:71–77. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Qin W, Tian J, Liu P, Li L, Chen P, Dai J, Craggs JG, von Deneen KM, Liu Y. Time-varied characteristics of acupuncture effects in fMRI studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009c;30:3445–3460. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Zhang M, Chen S, Ai L, Xu M, Wang D, Wang F, Liu L, Wang F, Lao L. Characterizing acupuncture de qi in mild cognitive impairment: relations with small-world efficiency of functional brain networks. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013. 2013:304804. doi: 10.1155/2013/304804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlesimo GA, Lombardi MG, Caltagirone C. Vascular thalamic amnesia: a reappraisal. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:777–789. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Bai L, Xu M, Wang F, Yin L, Peng X, Chen X, Shi X. Multivariate granger causality analysis of acupuncture effects in mild cognitive impairment patients: an FMRI study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013. 2013:127271. doi: 10.1155/2013/127271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SJ, Liu JW, Liu B, Wu SS, Chen J, Ran PC, Xiao YC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging study on acupuncturing Shenmen (HT 7) and sham acupoint. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. 2008;6:242–244. [Google Scholar]

- Chen SJ, Meng L, Yan H, Bai LJ, Wang F, Huang Y, Li JP, Peng XM, Shi XM. Functional organization of complex brain networks modulated by acupuncture at different acupoints belonging to the same anatomic segment. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012;125:2694–2700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SJ, Xu MS, Li H, Liang JP, Yin L, Liu X, Jia XY, Zhu F, Wang D, Shi XM, Zhao LH. Acupuncture at the Taixi (KI3) acupoint activates cerebral neurons in elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:1163–1168. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.135319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vogelaere F, Santens P, Achten E, Boon P, Vingerhoets G. Altered default-mode network activation in mild cognitive impairment compared with healthy aging. Neuroradiology. 2012;54:1195–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00234-012-1036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbeuck X, Van der Linden M, Collette F. Alzheimer's disease as a disconnection syndrome? Neuropsychol Rev. 2003;13:79–92. doi: 10.1023/a:1023832305702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirci O, Stevens MC, Andreasen NC, Michael A, Liu J, White T, Pearlson GD, Clark VP, Calhoun VD. Investigation of relationships between fMRI brain networks in the spectral domain using ICA and Granger causality reveals distinct differences between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Neuroimage. 2009;46:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deToledo-Morrell L, Stoub TR, Bulgakova M, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Leurgans S, Wuu J, Turner DA. MRI-derived entorhinal volume is a good predictor of conversion from MCI to AD. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:1197–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NU, Fair DA, Miezin FM, Cohen AL, Wenger KK, Dosenbach RA, Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Raichle ME, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11073–11078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704320104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drzezga A, Becker JA, Van Dijk KRA, Sreenivasan A, Talukdar T, Sullivan C, Schultz AP, Sepulcre J, Putcha D, Greve D, Johnson KA, Sperling RA. Neuronal dysfunction and disconnection of cortical hubs in non-demented subjects with elevated amyloid burden. Brain. 2011;134:1635–1646. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Jin Z, Wang Y, Li K, Kong J, Nixon EE, Zeng Y, Ren Y, Tong H, Wang Y, Wang P, Hui KK. The salient characteristics of the central effects of acupuncture needling: Limbic-paralimbic-neocortical network modulation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:1196–1206. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow MR. Treatment of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:362–367. doi: 10.2174/156720509788929282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Bai L, Ren Y, Chen S, Wang H, Zhang W, Tian J. FMRI connectivity analysis of acupuncture effects on the whole brain network in mild cognitive impairment patients. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Bai L, Zhang W, Xue T, Ren Y, Zhong C, Wang H, You Y, Liu Z, Dai J, Liu Y, Tian J. Investigation of acupoint specificity by multivariate granger causality analysis from functional MRI data. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:31–42. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare TA, Camerer CF, Rangel A. Self-control in decision-making involves modulation of the vmPFC valuation system. Science. 2009;324:646–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1168450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Chen Z, Evans A. Structural insights into aberrant topological patterns of large-scale cortical networks in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4756–4766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0141-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu A, Kao H. The clinical course of advanced dementia. New Engl J Med. 2010;362:363. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0911058. author reply 364-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KK, Liu J, Marina O, Napadow V, Haselgrove C, Kwong KK, Kennedy DN, Makris N. The integrated response of the human cerebro-cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. Neuroimage. 2005;27:479–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui KK, Liu J, Makris N, Gollub RL, Chen AJ, Moore CI, Kennedy DN, Rosen BR, Kwong KK. Acupuncture modulates the limbic system and subcortical gray structures of the human brain: evidence from fMRI studies in normal subjects. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;9:13–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(2000)9:1<13::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia JP, Wang YH, Zhang ZX. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and management of cognitive impairment and dementia (III): psychometric selection. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;91:735–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang DL, Chu X, Hu LL, Jiang SY, Hu F, Sun JM, Li CW. Yizhi Xingnao prescription improves the cognitive function of patients after a transient ischemic attack. Neural Regen Res. 2012;7:434–439. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Q, Lu G, Zhang Z, Zhong Y, Wang Z, Guo Y, Li K, Ding M, Liu Y. Granger causal influence predicts BOLD activity levels in the default mode network. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011;32:154–161. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:374–383. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Kaptchuk TJ, Webb JM, Kong JT, Sasaki Y, Polich GR, Vangel MG, Kwong K, Rosen B, Gollub RL. Functional neuroanatomical investigation of vision-related acupuncture point specificity-a multisession fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:38–46. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth F, Zilles K, Fox PT, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB. A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:519–534. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach EC. Six psychotropics for pre-symptomatic & early Alzheimer's (MCI), Parkinson's, and Huntington's disease modification. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:1712–1726. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.194708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AW, Lam LC, Kwan AK, Tsang CL, Zhang HW, Guo YQ, Xu CS. Electroacupuncture for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:232. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0740-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MK, Li YJ, Zhang GF, Chen JQ, Zhang JP, Qi J, Huang Y, Lai XS, Tang CZ. Acupuncture for ischemic stroke: cerebellar activation may be a central mechanism following Deqi. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:1997–2003. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.172318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Li YP, Zhu WZ, Chen X. Changes in brain functional network connectivity after stroke. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:51–60. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.125330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Wang Z, Yang Y, Jia X, Li K. Functional disconnection and compensation in mild cognitive impairment: evidence from DLPFC connectivity using resting-state fMRI. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie CH, Specht K, Marshall JC, Fink GR. Using fMRI to decompose the neural processes underlying the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Neuroimage. 2006;30:1038–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser MB, Moser EI. Distributed encoding and retrieval of spatial memory in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7535–7542. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07535.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata Y, Sato N, Abe O, Shikakura S, Arima K, Furuta N, Uno M, Hirai S, Masutani Y, Ohtomo K, Aoki S. Diffusion abnormality in posterior cingulate fiber tracts in Alzheimer's disease: tract-specific analysis. Radiat Med. 2008;26:466. doi: 10.1007/s11604-008-0258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, McMillan KM, Laird AR, Bullmore E. N-back working memory paradigm: a meta-analysis of normative functional neuroimaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25:46–59. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Caracciolo B, Brayne C, Gauthier S, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L. Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. J Intern Med. 2014;275:214–228. doi: 10.1111/joim.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M, Pandya DN. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: comparative cytoarchitectonic analysis in the human and the macaque brain and corticocortical connection patterns. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1011–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabat SR. Dementia in developing countries: a tidal wave on the horizon. Lancet. 2009;374:1805–1806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador R, Suckling J, Coleman MR, Pickard JD, Menon D, Bullmore E. Neurophysiological architecture of functional magnetic resonance images of human brain. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1332–1342. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Lee S, Suzuki T. Cognitive Impairment and Disability in Older Japanese Adults. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa RM, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Albanese E, Guerra M, Huang Y, Jacob KS, Jotheeswaran AT, Rodriguez JJL, Pichardo GR, Rodriguez MC, Salas A, Sosa AL, Williams J, Zuniga T, Prince M. Contribution of chronic diseases to disability in elderly people in countries with low and middle incomes: a 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based survey. Lancet. 2009;374:1821–1830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61829-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein T, Moritz C, Quigley M, Cordes D, Haughton V, Meyerand E. Functional connectivity in the thalamus and hippocampus studied with functional MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1397–1401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens FL, Hurley RA, Taber KH, Hurley RA, Hayman LA, Taber KH. Anterior cingulate cortex: unique role in cognition and emotion. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23:121–125. doi: 10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnp121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Qin W, Jin L, Dong M, Yang X, Zhu Y, Yang Y, von Deneen KM, Gong Q, Tian J. Impact of global normalization in FMRI acupuncture studies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012. 2012:467061. doi: 10.1155/2012/467061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Yin Q, Fang R, Yan X, Wang Y, Bezerianos A, Tang H, Miao F, Sun J. Disrupted functional brain connectivity and its association to structural connectivity in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triaca V, Calissano P. Impairment of the nerve growth factor pathway driving amyloid accumulation in cholinergic neurons: the incipit of the Alzheimer's disease story? Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:1553–1556. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.193224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turriziani P, Smirni D, Zappalà G, Mangano GR, Oliveri M, Cipolotti L. Enhancing memory performance with rTMS in healthy subjects and individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment: the role of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:62. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zuo X, Dai Z, Xia M, Zhao Z, Zhao X, Jia J, Han Y, He Y. Disrupted functional brain connectome in individuals at risk for Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:472–481. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Jia X, Liang P, Qi Z, Yang Y, Zhou W, Li K. Changes in thalamus connectivity in mild cognitive impairment: Evidence from resting state fMRI. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Liang P, Jia X, Qi Z, Yu L, Yang Y, Zhou W, Lu J, Li K. Baseline and longitudinal patterns of hippocampal connectivity in mild cognitive impairment: Evidence from resting state fMRI. J Neurol Sci. 2011;309:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang J, Guo H, Cao R, Liang H, Chen JJ. An abnormal resting-state functional brain network indicates progression towards Alzheimer's disease. Neural Regen Res. 2013;8:2789–2799. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.30.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C, Li W, Chen G, Ward BD, Franczak MB, Jones JL, Antuono PG, Li SJ, Goveas JS. Late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment and hippocampal functional network architecture. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;3:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C, Bai F, Yu H, Shi Y, Yuan Y, Chen G, Li W, Chen G, Zhang Z, Li SJ. Abnormal insula functional network is associated with episodic memory decline in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2012;63:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SQ, Wang YJ, Zhang JP, Chen JQ, Wu CX, Li ZP, Chen JR, Ouyang HL, Huang Y, Tang CZ. Brain activation and inhibition after acupuncture at Taichong and Taixi: resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:292–297. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.152385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong C, Bai L, Dai R, Xue T, Wang H, Feng Y, Liu Z, You Y, Chen S, Tian J. Modulatory effects of acupuncture on resting-state networks: a functional MRI study combining independent component analysis and multivariate granger causality analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35:572–581. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Zhang YL, Cao HJ, Hu H. Treating vascular mild cognitive impairment by acupuncture: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2013;33:1626–1630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]