Keywords: nerve regeneration, edaravone, apoptosis, astrocytes, integrated stress response, reactive oxygen species, PERK, eIF2α, activating transcription factor 4, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein, caspase-3, caspase-12, neural regeneration

Abstract

We previously found that oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration (OGSD/R) induces apoptosis of spinal cord astrocytes, possibly via caspase-12 and the integrated stress response, which involves protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), eukaryotic initiation factor 2-alpha (eIF2α) and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). We hypothesized that edaravone, a low molecular weight, lipophilic free radical scavenger, would reduce OGSD/R-induced apoptosis of spinal cord astrocytes. To test this, we established primary cultures of rat astrocytes, and exposed them to 8 hours/6 hours of OGSD/R with or without edaravone (0.1, 1, 10, 100 μM) treatment. We found that 100 μM of edaravone significantly suppressed astrocyte apoptosis and inhibited the release of reactive oxygen species. It also inhibited the activation of caspase-12 and caspase-3, and reduced the expression of homologous CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, phosphorylated (p)-PERK, p-eIF2α, and ATF4. These results point to a new use of an established drug in the prevention of OGSD/R-mediated spinal cord astrocyte apoptosis via the integrated stress response.

Introduction

Astrocytes are ubiquitously distributed in the central nervous system and play an important role in synapse formation, plasticity, and the development and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier (Chen et al., 2016). They also provide metabolic and trophic support to neurons (Pabst et al., 2016). Properly functioning astrocytes are particularly important in maintaining neuronal viability under ischemic conditions, where energy depletion and metabolic disruption are severe (Ouyang et al., 2013; Shindo et al., 2016). Impairment or dysfunction of astrocytes can result in neuronal death. Edaravone (3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one) is a free radical scavenger used in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke (Turan et al., 2017). It suppresses the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), early accumulation of oxidative products, and subsequent inflammatory responses. A growing body of evidence indicates that edaravone protects all three major cell types of the neurovascular unit (neuron, astrocyte, and cerebral endothelium). For example, it protects against MPP+-induced cytotoxicity in rat primary cultured astrocytes by inhibiting the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (Chen et al., 2008). Wang et al. (2011) reported that edaravone treatment reduced brain edema, blood-brain barrier permeability, and neuronal death, and improved neurological function, in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Furthermore, our previous study suggested that caspase-12 activation and the integrated stress response, which involves protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), eukaryotic initiation factor 2-alpha (eIF2α) and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), are involved in the apoptosis of spinal cord astrocytes induced by oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration (OGSD/R) (Zhang et al., 2010).

Despite such reports of the favorable effects of edaravone on the central nervous system, its role in OGSD/R-mediated astrocytic apoptosis remains elusive. In the present study, we investigated whether edaravone protects against the integrated stress response and caspase-12 in OGSD/R-mediated astrocytic apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Female and male Sprague-Dawley rats, aged 3 months and weighing 200–250 g (Shanghai Super B&K Laboratory Animal Corp., Ltd., Shanghai, China, SCXK (Hu) 2008-0016) were housed under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. Spinal cords were obtained from the newborn rat pups (1–2 days old) for astrocyte culture. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of Soochow University, China.

Primary culture of spinal cord astrocytes

The spinal cords were dissected under sterile conditions, the meninges carefully removed, and the cord tissue dissociated in 0.25% trypsin for 6 minutes at 37°C. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 219 × g for 5 minutes. Spinal cord astrocytes were cultured in accordance with the improved method of Black et al. (1993). The cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95 % air. More than 95 % of the cells were immunopositive for the astrocytic marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). The cells were used for subsequent experiments at approximately 12–15 days in culture. They were divided into three groups, incubated under the following conditions: (1) control group: oxygen-glucose-serum (OGS)-supplied medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA); (2) OGSD/R group: OGS-deprived medium for 8 hours, followed by OGS-supplied medium for 6 hours; (3) four OGSD/R + edaravone groups: incubation in edaravone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) at concentrations of 0.1, 1, 10, or 100 μM, and subsequent incubation in OGS-deprived medium for 8 hours, then OGS-supplied medium for 6 hours.

Cell viability assay

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was used to measure cell viability, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were plated on 96-well plates (5,000 cells/well) and allowed to adhere for 24 hours at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Subsequently, CCK-8 solution was added to each well and the cells were incubated for an additional 2 hours at 37°C for optical absorbance measurement at 450 nm (ELx800 Absorbance Microplate Reader; Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Apoptotic assay

Apoptotic astrocytes were counted by plating the cells onto glass slides and allowing them to adhere for 24 hours at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The cells were then fixed for 1 hour in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and stained with 5 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Sigma) for 30 minutes at 37°C in a moist chamber. The morphological features of apoptosis were observed by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan). At least 400 cells were counted from 12 randomly selected fields per dish. Apoptotic cells were defined as those stained with Hoechst 33342, showing bright nuclei, and calculated as a percentage of the total number of cells.

ROS

ROS levels were determined using 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA) (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). Astrocytes in sub-confluent culture (5 × 104 cells/cm2) adhered on Petri dishes were incubated with or without edaravone for 30 minutes, followed by 8 hours/6 hours of OGSD/R, and then incubated with 10 μM H2DCF-DA dissolved in PBS (1 mL) at 37°C for 30 minutes. Images were captured using an Olympus BX51 microscope coupled with an Olympus DP70 digital camera. Fluorescence intensity was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 nm and 530 nm, respectively. All ROS levels were normalized to the mean ROS level of the control group.

Immunostaining

All incubations were at room temperature unless stated otherwise. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 minutes and permeabilized in 2% bovine serum albumin/0.2% Triton X-100/PBS for 1 hour. They were then incubated with goat anti-GFAP polyclonal antibody (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C, followed by FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 hours in the dark. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-caspase-12 antibody (1:100) for 10 hours at 4°C, then TRITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 hours in the dark, and finally with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1:10,000) for 15 minutes in the dark. Images were captured using a fluorescence microscopy imaging system (Olympus, Hatagaya, Japan).

Western blot assay

Cells were plated on 6-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 hours at 37°C before treatment. Astrocyte cell lysates were prepared in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Beyotime) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonylfluoride (Calbiochem). After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes, the lysate supernatants were denatured and loaded onto a 10 % gel for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The separated proteins (1 μg) were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked by overnight incubation in 5% nonfat milk at 4°C, and then incubated with the primary antibodies or 3 hours at room temperature. Individual blots were probed with mouse polyclonal anti-cleaved-caspase-3, mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-PERK, rabbit polyclonal anti-phosphorylated (p)-PERK (CST Inc., Beverly, MA, USA), polyclonal anti-eIF2α, polyclonal anti-p-eIF2α (S51), polyclonal anti-caspase-12, polyclonal anti-ATF4, and polyclonal anti-CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) (Abcam, USA). The membranes were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000) for 1 hour at room temperature. The immune complexes were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and quantified by gray value measurement using a Tanon imaging system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). The relative expression levels were calculated from the gray value ratios of the target protein to β-actin (housekeeping protein).

Statistical analysis

Paired t-tests or one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test were carried out using SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Edaravone inhibited OGSD/R-induced apoptosis of astrocytes in rat spinal cord

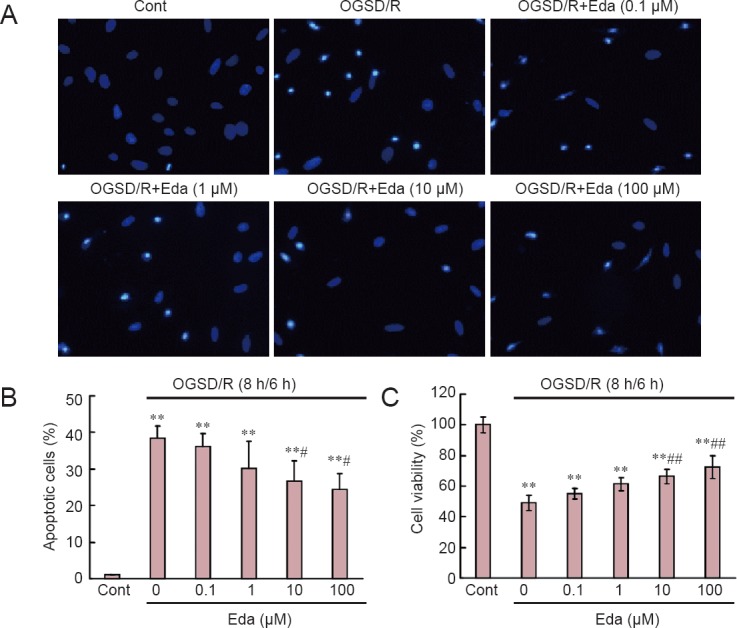

The effect of edaravone on the apoptotic status of cells in culture under OGSD/R was first assessed by morphological examination. Apoptotic cells with condensed or fragmented nuclei were detected after OGSD/R (Figure 1A). Cultures exposed to 8 hours/6 hours of OGSD/R had significantly more apoptotic cells than non-treated cultures (P < 0.05; Figure 1B). Moreover, high concentrations of edaravone (10 and 100 μM) significantly suppressed apoptosis after 8 hours/6 hours of OGSD/R (P < 0.05; Figure 1B). The CCK-8 cell viability assay confirmed the Hoechst staining results (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Edaravone (Eda) reduces oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration (OGSD/R)-induced apoptosis of spinal cord astrocytes.

(A) Apoptotic cells with condensed or fragmented nuclei were detected after OGSD/R (Hoechst 33342 staining; original magnification, × 200). (B) Quantification of apoptotic cells. Eda (0.1, 1, 10, 100 μM) suppressed OGSD/R-induced apoptosis. (C) Cell viability (Cell Counting Kit-8 assay). Data are normalized to control (Cont; no treatment). All data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 30; one-way analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test). **P < 0.01, vs. Cont; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, vs. OGSD/R. h: Hours.

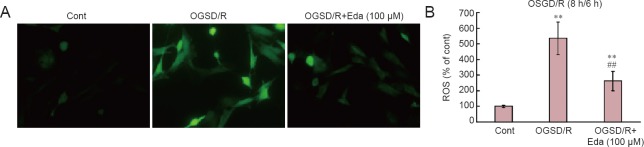

Edaravone inhibitd the release of ROS after OGSD/R

ROS production in spinal cord astrocytes was measured by fluorescent staining with fluorescent dye H2DCF-DA (Figure 2). OGSD/R led to an increase in ROS release in spinal cord astrocytes. In addition, 100 μM edaravone significantly inhibited the release of ROS after 8 hours/6 hours of OGSD/R (P < 0.05; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Edaravone (Eda) reduces oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration (OGSD/R)-induced release of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in spinal cord astrocytes.

(A) Representative images of ROS immunofluorescence (staining with fluorescent dye H2DCF-DA; × 200). (B) Quantification of ROS production. OGSD/R induced ROS production. Pre-treatment with Eda (100 μM) suppressed OGSD/R-induced ROS production. OGSD/R led to an increase of ROS release. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 34; one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test). **P < 0.01, vs. control (Cont; no treatment); ##P < 0.01, vs. OGSD/R. h: Hours.

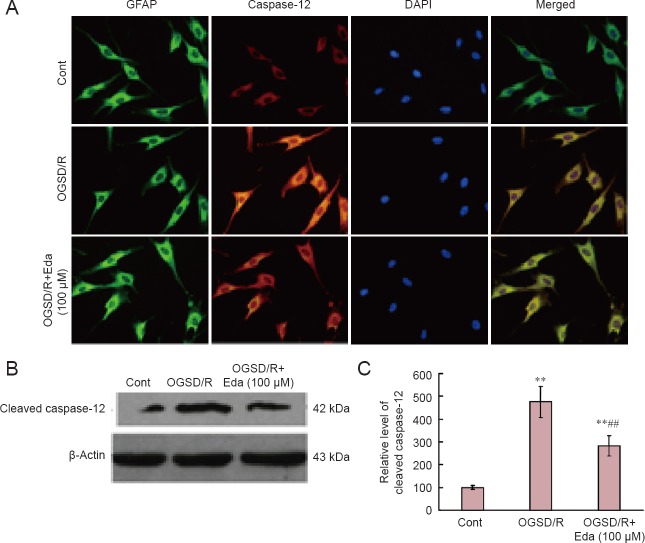

Edaravone reduced caspase-12 protein expression after OGSD/R

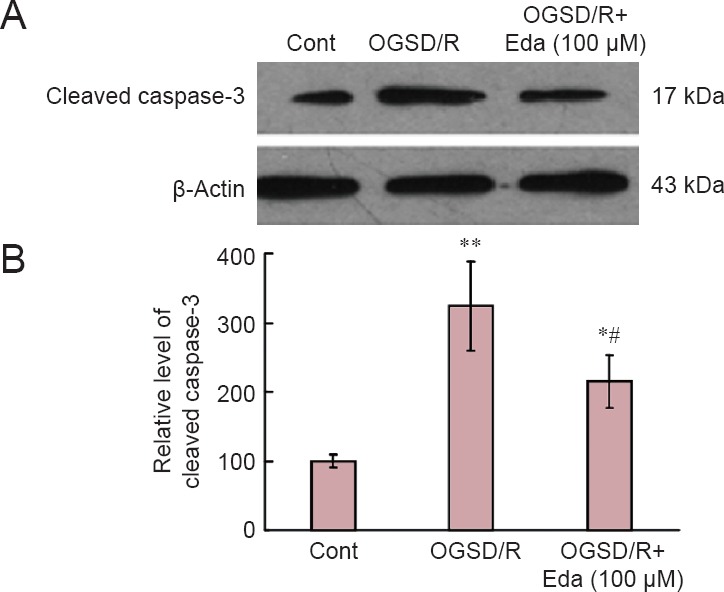

Western blot assay revealed that cleaved caspase-3 expression was elevated after 8 hours/6 hours of OGSD/R (Figure 3). Edaravone-treated cells had significantly lower cleaved caspase-3 protein expression after OGSD/R than those exposed to OGSD/R without edaravone (Figure 3; P < 0.05). Cytoplasmic staining of pro-caspase-12 was also elevated after 8 hours/6 hours of OGSD/R, and this effect was also smaller in edaravone-treated cells (P < 0.05; Figure 4A). A similar increase was observed in cleaved-caspase-12 expression in OGSD/R-exposed astrocytes, and this was also reduced by edaravone (P < 0.05; Figure 4B, C).

Figure 3.

Edaravone (Eda) inhibits the caspase-3 signaling pathway after oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration (OGSD/R).

(A) Western blots of cleaved caspase-3. (B) Quantification of cleaved caspase-3 protein expression. Eda (100 μM) inhibited OGSD/R-induced activation of caspase-3 from spinal cord astrocytes. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6; one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. control (Cont; no treatment); #P < 0.05, vs. OGSD/R group.

Figure 4.

Edaravone (Eda) reduces oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration (OGSD/R)-induced increase in caspase-12 protein expression.

(A) Changes in immunoreactivity and cellular distribution of caspase-12 in control (Cont), OGSD/R and OGSD/R + Eda (100 μM) groups. There was little caspase-12 protein expression in the Cont group (no treatment). Cytoplasm staining of caspase-12 was increased in the OGSD/R group. Green, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP); red, caspase-12; blue, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI); merged images are shown on the right. Eda inhibited OGSD/R-induced activation of caspase-12 from astrocytes (immunofluorescence staining, × 200). (B) Western blots of cleaved caspase-12 protein expression. (C) Quantification of caspase-12 protein expression. Eda inhibited OGSD/R-induced activation of caspase-12 from spinal cord astrocytes. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6; one-way analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test). **P < 0.01, vs. Cont; ##P < 0.01, vs. OGSD/R.

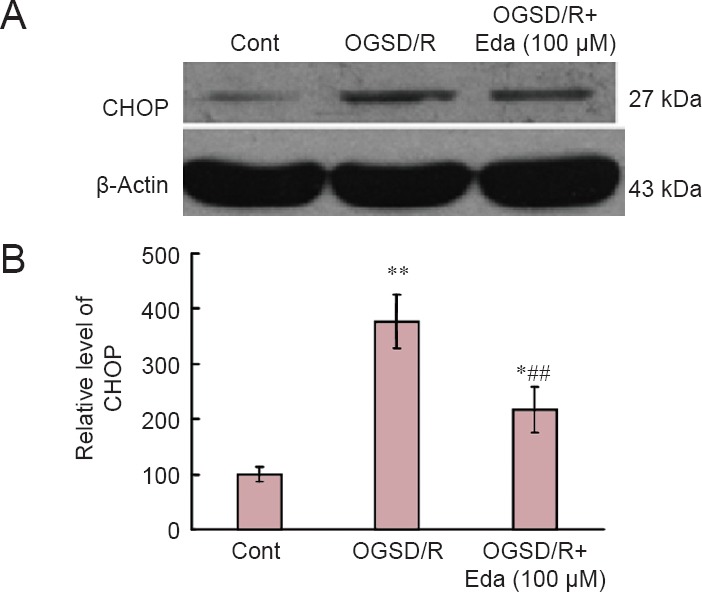

Edaravone reduced the expression of CHOP after OGSD/R

To investigate the effect of edaravone on the induction of CHOP in astrocytes exposed to OGSD/R, we examined CHOP expression by western blot assay. CHOP expression was elevated after OGSD/R, and this effect was reduced by edaravone (P < 0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of edaravone (Eda) on the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) signaling pathway after oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration (OGSD/R).

(A) Western blots of CHOP protein expression. (B) Quantification of CHOP protein expression (relative optical density of blots). Eda (100 μM) suppressed OGSD/R-induced CHOP expression in astrocytes. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6; one-way analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. control (Cont; no treatment); ##P < 0.01, vs. OGSD/R.

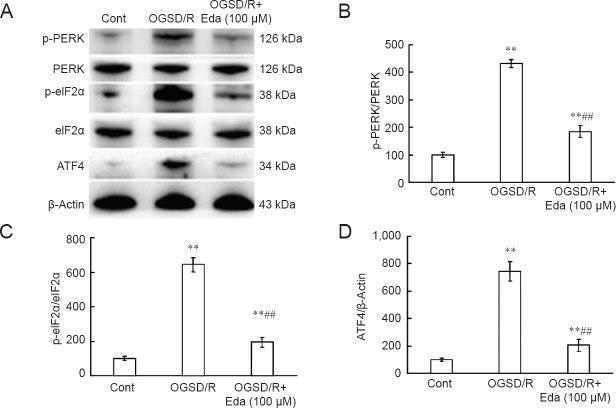

Edaravone reduced expression of p-PERK, p-eIF2α, and ATF4 after OGSD/R

Finally, we investigated the effect of edaravone on PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling after OGSD/R. Protein expression of p-PERK, p-eIF2α, and ATF4 was significantly lower after edaravone treatment in astrocytes exposed to 8 hours/6 hours of OGSD/R than in those without edaravone (P < 0.05; Figure 6). This indicates that edaravone protects spinal cord astrocytes against OGSD/R-induced apoptosis by inhibiting the integrated stress response and caspase-12.

Figure 6.

Effects of edaravone (Eda) on the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway after oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration (OGSD/R).

(A) Western blots of PERK, p-PERK, eIF2α, p-eIF2α, and ATF4 protein expression. (B–D) Quantification of p-PERK and PERK (B), p-eIF2α and eIF2α (C) and ATF4 (D) protein expression (relative optical density of bands). Eda (100 μM) suppressed activation of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 pathway in spinal cord astrocytes during OGSD/R. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6; one-way analysis of variance followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls tests). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs. control (Cont; no treatment); ##P < 0.01, vs. OGSD/R.

Discussion

We previously reported that OGSD/R induces apoptosis of spinal cord astrocytes, and that this effect is regulated by the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 integrated stress response and activation of caspase-12 (Zhang et al., 2010). Therefore, suppressing either PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 or caspase-12 activation may be novel targets for preventing OGSD/R-mediated astrocyte apoptosis. Here, we show that edaravone suppresses OGSD/R-induced elevation of PERK/eIF2α/ATF4 and CHOP expression, and activation of caspase-12 and caspase-3, subsequently decreasing apoptosis in spinal cord astrocytes.

Edaravone is an established drug in Japan, where it has been used to treat patients with acute ischemic stroke for more than 10 years, but it does not have marketing authorization in Europe or the USA (Edaravone Acute Infarction Study, 2003). Other free radical scavengers, such as ebselen and tirilazad, progressed to clinical trials in patients with cerebral infarction, but were terminated because of inadequate therapeutic effects (Handa et al., 2000; Hukkelhoven et al., 2002). In contrast, edaravone has been administered within 24 hours of cerebral infarction in patients with lacunae, large-artery atherosclerosis, and cardioembolic cerebral infarction (Okamura et al., 2014). Here, we have shown for the first time that edaravone significantly suppresses apoptosis in spinal cord astrocytes after OGSD/R.

ROS generation occurs during endoplasmic reticulum stress by protein oxidation (Bhandary et al., 2012). ROS levels increase upon exposure to toxic agents, such as irradiation and environmental pollutants, or during enzymatic reactions, including amino acid oxidase and NADP/NADPH oxidase (Kim et al., 2014). Edaravone acts as a strong scavenger of free radicals in multiple cell lines and experimental systems, including cancer cells, neurons and peripheral blood lymphocytes (Mizuno et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2014; Cheng and Zhang, 2014). Consistent with these reports, we found that edaravone inhibited the generation of ROS in spinal cord astrocytes after OGSD/R.

The endoplasmic reticulum is an active organelle that acts by folding and modifying secretory and membrane proteins. The unfolded protein response is a cellular stress response related to the endoplasmic reticulum and is activated upon the detection of an accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. A malfunction of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response caused by aging, genetic mutations, or environmental factors can result in various diseases, such as diabetes, inflammation, and nervous system disorders including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and cerebral ischemia (Yoshida, 2007; Lin, 2015; Liu and Connor, 2015; Yang and Hu, 2015). PERK undergoes dimerization and autophosphorylation to initiate a transient cellular translational arrest and inactivating eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF2α) (Harding et al., 1999; Ma et al., 2002). p-eIF2α can translate genes, one of which encodes ATF4, a member of the cAMP response element-binding family of transcription factors (Lu et al., 2004). In the present study, edaravone blocked OGSD/R-induced phosphorylation of PERK and eIF2α and expression of ATF4 in spinal cord astrocytes.

CHOP is a proapoptotic unfolded protein response gene and may play a role in the contribution of endoplasmic reticulum stress to myocardial ischemia, cerebral infarction, and acute kidney injury (Sano and Reed, 2013). During endoplasmic reticulum stress, caspase-12, an endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated apoptosis marker, dissociates from the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and is activated (Shibata and Kobayashi, 2008). Caspase-3 is the key protease in cell demolition during apoptosis (Boland et al., 2013). H2O2 could induce apoptosis in neuronal cells during endoplasmic reticulum stress by regulating the expression of CHOP, JNK, Bcl-2, Bax and Bim and the activation of caspase-12 (Ye et al., 2014). Medicarpin, a pterocarpan class of naturally occurring benzopyran furanobenzene compound, sensitizes myeloid leukemia cells to TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis through activation of the ROS-JNK-CHOP and caspase-3 pathways (Trivedi et al., 2014). Ilimaquinone, a cytoplasmic microtubule inhibitor, enhances the sensitivity of human colon cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through ROS-ERK/p38 MAPK-CHOP-mediated upregulation of TRAIL receptor 1 (DR4) and TRAIL receptor 2 (DR5) expression (Do et al., 2014). In this study, we found that edaravone decreased the expression of CHOP, and the activation of caspase-12 and -3, in spinal cord astrocytes after OGSD/R.

In conclusion, edaravone suppresses OGSD/R-induced apoptosis of spinal cord astrocytes. It blocks ROS generation, CHOP expression, caspase-12 and -3 activation, and inhibits the PERK/eIF2/ATF4 signaling pathway. Our study highlights a potential new use for an established drug: the prevention of OGSD/R-mediated spinal cord astrocyte apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

This paper was greatly improved by critical comments from Dr. Y Zhu.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Science & Technology Bureau of Changzhou City of China, No. CJ20130029.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Plagiarism check: This paper was screened twice using CrossCheck to verify originality before publication.

Peer review: This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

Copyedited by Slone-Murphy J, Frenchman B, Wang J, Li CH, Qiu Y, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- Bhandary B, Marahatta A, Kim HR, Chae HJ. An involvement of oxidative stress in endoplasmic reticulum stress and its associated diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;14:434–456. doi: 10.3390/ijms14010434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JA, Sontheimer H, Waxman SG. Spinal cord astrocytes in vitro: phenotypic diversity and sodium channel immunoreactivity. Glia. 1993;7:272–285. doi: 10.1002/glia.440070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland K, Flanagan L, Prehn JH. Paracrine control of tissue regeneration and cell proliferation by Caspase-3. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e725. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Wang S, Ding JH, Hu G. Edaravone protects against MPP+ -induced cytotoxicity in rat primary cultured astrocytes via inhibition of mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. J Neurochem. 2008;106:2345–2352. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Liu Y, Dong L, Chu X. Edaravone protects human peripheral blood lymphocytes from gamma-irradiation-induced apoptosis and DNA damage. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2014;20:289–295. doi: 10.1007/s12192-014-0542-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Boire A, Jin X, Valiente M, Er EE, Lopez-Soto A, Jacob LS, Patwa R, Shah H, Xu K, Cross JR, Massague J. Carcinoma-astrocyte gap junctions promote brain metastasis by cGAMP transfer. Nature. 2016;533:493–498. doi: 10.1038/nature18268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng XL, Zhang JJ. Effect of edaravone on apoptosis of hippocampus neuron in seizures rats kindled by pentylenetetrazole. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:769–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do MT, Na M, Kim HG, Khanal T, Choi JH, Jin SW, Oh SH, Hwang IH, Chung YC, Kim HS, Jeong TC, Jeong HG. Ilimaquinone induces death receptor expression and sensitizes human colon cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through activation of ROS-ERK/p38 MAPK-CHOP signaling pathways. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;71:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edaravone Acute Infarction Study G (2003) Effect of a novel free radical scavenger, edaravone (MCI-186), on acute brain infarction. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study at multicenters. Cerebrovasc Dis. 15:222–229. doi: 10.1159/000069318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa Y, Kaneko M, Takeuchi H, Tsuchida A, Kobayashi H, Kubota T. Effect of an antioxidant, Ebselen, on development of chronic cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage in primates. Surg Neurol. 2000;53:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Farace E, Habbema JD, Marshall LF, Maas AI. Regional differences in patient characteristics, case management, and outcomes in traumatic brain injury: experience from the tirilazad trials. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:549–557. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.3.0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HG, Kim YR, Park JH, Khanal T, Choi JH, Do MT, Jin SW, Han EH, Chung YH, Jeong HG. Endosulfan induces COX-2 expression via NADPH oxidase and the ROS, MAPK, and Akt pathways. Arch Toxicol. 2014;89:2039–2050. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1359-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CL. Attenuation of endoplasmic reticulum stress as a treatment strategy against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:1930–1931. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.169615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang Y, Xu R, Du J, Hu Z, Yang L, Chen Y, Zhu Y, Gu L. PI3K/Akt-dependent phosphorylation of GSK3beta and activation of RhoA regulate Wnt5a-induced gastric cancer cell migration. Cell Signal. 2013;25:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Connor JR. From adaption to death: endoplasmic reticulum stress as a novel target of selective neurodegeneration? Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:1397–1398. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.165227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:27–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Vattem KM, Wek RC. Dimerization and release of molecular chaperone inhibition facilitate activation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2 kinase in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18728–18735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno N, Takahashi T, Kusuhara H, Schuetz JD, Niwa T, Sugiyama Y. Evaluation of the role of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) and multidrug resistance-associated protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4) in the urinary excretion of sulfate and glucuronide metabolites of edaravone (MCI-186; 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one) Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:2045–2052. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Tsubokawa T, Johshita H, Miyazaki H, Shiokawa Y. Edaravone, a free radical scavenger, attenuates cerebral infarction and hemorrhagic infarction in rats with hyperglycemia. Neurol Res. 2014;36:65–69. doi: 10.1179/1743132813Y.0000000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada N, Kosuge Y, Ishige K, Ito Y. Characterization of neuronal and astroglial responses to ER stress in the hippocampal CA1 area in mice following transient forebrain ischemia. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang YB, Xu L, Lu Y, Sun X, Yue S, Xiong XX, Giffard RG. Astrocyte-enriched miR-29a targets PUMA and reduces neuronal vulnerability to forebrain ischemia. Glia. 2013;61:1784–1794. doi: 10.1002/glia.22556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabst M, Braganza O, Dannenberg H, Hu W, Pothmann L, Rosen J, Mody I, van Loo K, Deisseroth K, Becker AJ, Schoch S, Beck H. Astrocyte intermediaries of septal cholinergic modulation in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2016;90:853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano R, Reed JC. ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochimica Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:3460–3470. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N, Kobayashi M. The role for oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Nerve. 2008;60:157–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo A, Maki T, Mandeville ET, Liang AC, Egawa N, Itoh K, Itoh N, Borlongan M, Holder JC, Chuang TT, McNeish JD, Tomimoto H, Lok J, Lo EH, Arai K. Astrocyte-derived pentraxin 3 supports blood-brain barrier integrity under acute phase of stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:1094–1100. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi R, Maurya R, Mishra DP. Medicarpin, a legume phytoalexin sensitizes myeloid leukemia cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the induction of DR5 and activation of the ROS-JNK-CHOP pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1465. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan M, Ciger E, Arslanoglu S, Borekci H, Onal K. Could edaravone prevent gentamicin ototoxicity? An experimental study. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0960327116639360. doi:10.1177/0960327116639360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GH, Jiang ZL, Li YC, Li X, Shi H, Gao YQ, Vosler PS, Chen J. Free-radical scavenger edaravone treatment confers neuroprotection against traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:2123–2134. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JW, Hu ZP. Neuroprotective effects of atorvastatin against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through the inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10:1239–1244. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.162755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Han Y, Chen X, Xie J, Liu X, Qiao S, Wang C. l-Carnitine attenuates HO-induced neuron apoptosis via inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Neurochem Int 78C. 2014:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H. ER stress and diseases. FEBS J. 2007;274:630–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A, Zhang J, Sun P, Yao C, Su C, Sui T, Huang H, Cao X, Ge Y. EIF2alpha and caspase-12 activation are involved in oxygen-glucose-serum deprivation/restoration-induced apoptosis of spinal cord astrocytes. Neurosci Lett. 2010;478:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]