Abstract

Bilateral arm raising movements have been used in brain rehabilitation for a long time. However, no study has been reported on the effect of these movements on the cerebral cortex. In this study, using functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), we attempted to investigate cortical activation generated during bilateral arm raising movements. Ten normal subjects were recruited for this study. fNIRS was performed using an fNIRS system with 49 channels. Bilateral arm raising movements were performed in sitting position at the rate of 0.5 Hz. We measured values of oxyhemoglobin and total hemoglobin in five regions of interest: the primary sensorimotor cortex, premotor cortex, supplementary motor area, prefrontal cortex, and posterior parietal cortex. During performance of bilateral arm raising movements, oxyhemoglobin and total hemoglobin values in the primary sensorimotor cortex, premotor cortex, supplementary motor area, and prefrontal cortex were similar, but higher in these regions than those in the prefrontal cortex. We observed activation of the arm somatotopic areas of the primary sensorimotor cortex and premotor cortex in both hemispheres during bilateral arm raising movements. According to this result, bilateral arm raising movements appeared to induce large-scale neuronal activation and therefore arm raising movements would be good exercise for recovery of brain functions.

Keywords: nerve regeneration, neuronal activation, bilateral arm raising, functional NIRS, motor control, corticospinal tract, corticoreticulospinal tract, neural regeneration

Introduction

Various therapeutic modalities, including therapeutic exercise for physical therapy intervention, neurotrophic drugs, procedures for relieving spasticity, neuromuscular electrical stimulation for the affected extremities and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, have been used in rehabilitation for patients with brain injury (Feeney et al., 1982; Bobath, 1990; Scheidtmann et al., 2001; Carr and Shepherd, 2003; Takeuchi et al., 2005; Kwon and Jang, 2012; Lee and Jang, 2012). Among these modalities, therapeutic exercise has long been a basic and essential modality of physical therapy for brain rehabilitation (Bobath, 1990; Carr and Shepherd, 2003). The focus of therapeutic exercise has been on relieving spasticity of affected extremities, or improving functional activity (Bobath, 1990; Carr and Shepherd, 2003). Consequently, little is known about the direct effect of therapeutic exercise on the brain. This information can be useful for development of scientific therapeutic strategies based on the concept of brain plasticity; therefore, clarification of this effect of therapeutic exercise would be important for patients with brain injury (Bach-y-Rita, 1981; Kaplan, 1988).

Bilateral arm raising movements have been used in therapeutic exercise of brain rehabilitation for a long time (Bobath, 1990). In addition, it is one of the most commonly recommended bedside exercises during rehabilitation in patients with brain injury (Bobath, 1990). This movement is known to be effective in practice of range of motion exercise of upper extremity, improving awareness of equality of both hands, and relieving flexor spasticity of upper extremity (Bobath, 1990). However, no study has reported on the effect of these movements on the cerebral cortex which concerned with motor planning and execution. Among functional neuroimaging techniques, functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), which measures hemodynamic changes in the cerebral cortex, would be appropriate for research on the cortical effect of bilateral arm raising movement because fNIRS is less sensitive to motion artifact (Miyai et al., 2001; Perrey, 2008; Holtzer et al., 2011; Leff et al., 2011; Karim et al., 2012; Kurz et al., 2012).

In the current study, using fNIRS, we attempted to investigate cortical activation generated during bilateral arm raising movements.

Subjects and Methods

Participants

Ten healthy subjects (eight males, two females; mean age 29.40 ± 1.43 years, range 25–32 years) with no history of neurological, physical, or psychiatric illness were recruited for this study through volunteer recruitment notice. All subjects understood the purpose of the study and provided written, informed consent prior to participation. The study protocol was approved by our Institutional Review Board (approval No. YUH-12-0419-D12).

Bilateral arm raising movements

All subjects were asked to sit comfortably on a chair in an upright position. The subjects were instructed to extend the elbow fully and clasp their fingers with the direction of their palms facing outward on the thigh, and raise their hands up to the horizontal level with the uppermost part of the head, and then return to the thigh. The motor task was performed from the knee to vertical position (Figure 1). Using a block paradigm design (three cycles; resting [20 seconds]-motor task [20 seconds]-resting [20 seconds]-motor task [20 seconds]-resting [20 seconds]-motor task [20 seconds]), bilateral arm raising movements were performed at a frequency of 0.5 Hz under metronome guidance. The motor task was repeated three times at intervals of 5 minutes for the rest between each motor task.

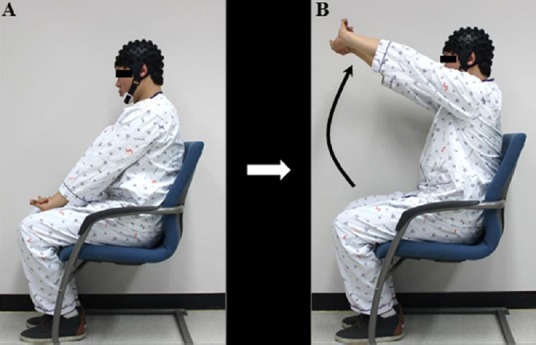

Figure 1.

Arm raising movement for the therapeutic exercise.

The subjects were instructed to extend the elbow fully and clasp their fingers with the direction of their palms facing outward on the thigh (A), and to raise their hands up to the horizontal level with the uppermost part of the head (B), and then return to the thigh.

fNIRS

The fNIRS system (FOIRE-3000; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), with continuous wave laser diodes with wavelengths of 780, 805, and 830 nm, was used for recording of cortical activity at a sampling rate of 10 Hz; we employed a 49-channel system with 30 optodes (15 light sources and 15 detectors). Based on the modified Beer-Lambert law, we acquired values for oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and total hemoglobin (HbT) following changes in levels of cortical concentration (Cope and Delpy, 1988). The international 10/20 system, with Cz (cranial vertex) located beneath the 25th channel, was used for positioning of optodes. A stand-alone application was used for spatial registration of the acquired 49 channels on the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) brain based on the 25th channel on the Cz (Cope and Delpy, 1988).

The software package NIRS-SPM (http://bisp.kaist.ac.kr/NIRS-SPM) implemented in the MATLAB environment (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) was used in analysis of fNIRS data. Gaussian smoothing with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 2 seconds was applied to correction of noise from the fNIRS system (Cope and Delpy, 1988). The wavelet-minimum description length based detrending algorithm was used for correction of signal distortion due to breathing or movement of the subject (Ye et al., 2009). SPM t-statistic maps were computed, and significant value of HbO and HbT were considered significant at the threshold of P < 0.05 (with expected Euler characteristics) (Ye et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012).

Regions of interest (ROIs)

Based on the Brodmann area (BA) and anatomical locations of brain areas, we designated five ROIs in the bilateral hemispheres as follows: the primary sensorimotor cortex (SM1) (BA1, 2, 3, 4), supplementary motor area (SMA) (medial boundary: midline between the right and left hemispheres, lateral boundary: the line 15 mm lateral from the midline between the right and left hemispheres), premotor cortex (PMC) (BA6 except for the SMA), prefrontal cortex (PFC) (BA 8,9), and posterior parietal cortex (PPC) (BA 5,7) (Brodmann, 1909; Afifi and Bergman, 2005). In addition, we divided the ROIs of the SM1 into two areas according to the homunculus: the somatotopic areas for arm and leg, respectively (Afifi and Bergman, 2005) (Figure 2A). Values for HbO and HbT were estimated from each channel of the five ROIs during performance of bilateral arm raising movements. Subsequently, using the NIRS-SPM, HbO and HbT values of each ROI were acquired based on the individual general linear model (GLM) analysis results; the values indicate the relative change of HbO and HbT between resting and motor task phase.

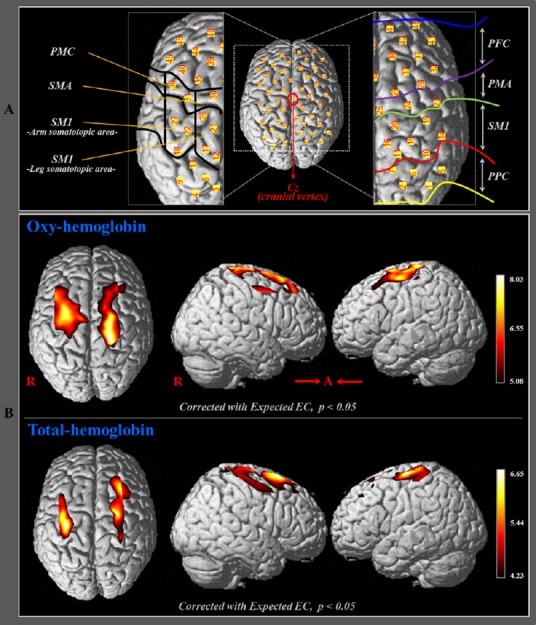

Figure 2.

Results of oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and total hemoglobin (HbT) values during bilateral arm raising movements in healthy participants.

(A) Five regions of interest based on the Brodmann area (BA) and anatomical location of areas of the brain. The primary sensorimotor cortex (SM1): BA1, 2, 3, and 4; supplementary motor area (SMA); premotor cortex (PMC); prefrontal cortex (PFC): BA8 and 9; posterior parietal cortex (PPC): BA5 and 7; the arm somatotopic area of the SM1 (medial boundary: medial margin of the precentral knob, lateral boundary: lateral margin of the precentral knob); the leg somatotopic area of the SM1 (medial boundary: longitudinal fissure, lateral boundary: medial margin of the precentral knob). (B) Group-average t-statistic maps of HbO and HbT during performance of bilateral arm raising movements using NIRS-SPM software (corrected with expected Euler characteristics, P < 0.05).

Data analysis

SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used in performance of data analysis. The Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc Mann-Whitney U test was used for determination of differences in HbO and HbT values between ROIs. Results were considered significant when P value was < 0.05.

Results

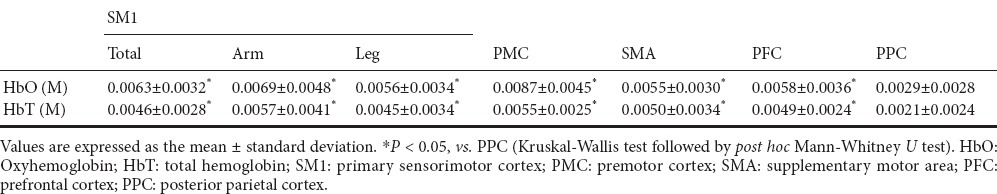

Based on the GLM analysis results, HbO and HbT values were acquired in each ROI; HbO and HbT values indicate relative change between resting and motor task phases during bilateral arm raising movements. HbO and HbT values were significantly higher in the SM1 (total: HbO = 0.0063, HbT = 0.0046; arm: HbO = 0.0069, HbT = 0.0057; leg: HbO = 0.0056, HbT = 0.0045), PMC (HbO = 0.0087, HbT = 0.0055), SMA (HbO = 0.0055, HbT = 0.0050) and PFC (HbO = 0.0058, HbT = 0.0049) than in the PPC (HbO = 0.0029, HbT = 0.0021) (P < 0.05) (Table 1). In comparisons between all SM1, PMC, SMA, and PFC, we observed no significant difference in HbO and HbT values (P > 0.05). In addition, no significant differences in HbO and HbT values were observed between the right and left hemispheres (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Comparison of oxyhemoglobin and total hemoglobin values between posterior parietal cortex and other regions of interests

t-statistic maps from HbO and HbT (corrected with expected EC, P < 0.05) values showed significant activation in bilateral SM1, PMC, and PFC during bilateral arm raising movements. Figure 2B showed higher activation in the arm somatotopic areas of the SM1 and PMC than in other ROIs in both hemispheres.

Discussion

In the current study, we measured HbO and HbT values as indices of neuronal activation in which neuronal activity was measured indirectly through detection of hemodynamic changes of the underlying cerebral cortex (oxygen consumption by neuronal cells) (Irani et al., 2007; Perrey, 2008). Cortical activation of the SM1, PMC, SMA and PFC was greater than that of PPC in both hemispheres. The results described above generally coincided with the results of t-statistic maps. Our results appear to suggest that performance of bilateral arm raising movements can activate bilateral SM1 and PMC. Consequently, bilateral arm raising movements appeared to require large-scale neuronal recruitment; therefore, it would be good exercise for brain activation.

Motor control in the human brain between musculature of proximal and distal joints has been suggested to differ (Freund and Hummelsheim, 1984, 1985; York, 1987; Davidoff, 1990; Matsuyama et al., 2004; Mendoza and Foundas, 2007; Jang, 2009; Yeo et al., 2012). Musculature of distal joints, particularly the hand, is controlled by the lateral corticospinal tract (York, 1987; Davidoff, 1990; Jang, 2009; Cho et al., 2012). By contrast, control of musculature of proximal joints, such as shoulder and hip, by the corticoreticulospinal tract has been suggested (Freund and Hummelsheim, 1984, 1985; York, 1987; Matsuyama et al., 2004; Mendoza and Foundas, 2007; Yeo et al., 2012). The corticospinal tract and corticoreticulospinal tract are known to originate mainly from the primary motor cortex and the PMC, respectively (Russell and Demyer, 1961; Jane et al., 1967; Matsuyama et al., 2004; Yeo et al., 2012). Therefore, our results showing bilateral arm SM1 and PMC were activated without difference indicate that the corticospinal tract and corticoreticulospinal tract were activated equally by performance of bilateral arm raising movements. The PMC is the cerebral area involved in planning, preparation, and initiation of movement, along with the SMA as a secondary motor area (Halsband et al., 1994; Leonard, 1998). Consequently, activation of the PMC appears to be related to motor planning for performance of bilateral arm raising movements.

Since introduction of functional neuroimaging techniques, many studies have reported on brain activation patterns during execution of various movements in normal subjects and patients with stroke (Miyai et al., 2001; Luft et al., 2002; Kapreli et al., 2006; Perrey, 2008; Holtzer et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011; Leff et al., 2011; Karim et al., 2012; Kurz et al., 2012). In 2013, using functional magnetic resonance imaging, Craciunas et al. (2013) suggested that stroke patients with poor proximal recovery showed low level of cortical activation in the SM1 and PMC (Craciunas et al., 2013). In 2015, using functional magnetic resonance imaging, Pundik et al. (2015) reported increment of cortical activation in contralesional and bilateral primary motor cortex and premotor cortex following recovery of proximal arm function in patients with stroke.

These results appear to be compatible with the results of the current study, which showed increased cortical activation in the SM1 and PMC by proximal joint movement. We believe that the results of this study would be helpful for conduct of research on brain rehabilitation. In addition, fNIRS is a good tool for use in research on the effects of therapeutic exercise on the brain, which is employed in the field of brain rehabilitation. However, this study is limited by a small sample size. In addition, the limitation that this study could not include patients with brain injury should be considered. Further studies about the clinical implications of these findings for patients with brain injury are required.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the DGIST R&D Program of the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning, No. 16-BD-0401.

Declaration of patient consent: The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Plagiarism check: This paper was screened twice using CrossCheck to verify originality before publication.

Peer review: This paper was double-blinded and stringently reviewed by international expert reviewers.

Copyedited by Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

References

- Afifi AK, Bergman RA. Functional neuroanatomy: text and atlas. 2nd Edition. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bach-y-Rita P. Brain plasticity as a basis of the development of rehabilitation procedures for hemiplegia. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1981;13:73–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobath B. Adult hemiplegia: evaluation and treatment. 3rd Edition. Oxford England: Heinemann Medical Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brodmann K. Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Grosshirnrinde in ihren Prinzipien dargestellt aufGrund des Zellenbaues. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth; 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Carr JH, Shepherd RB. Stroke rehabilitation: guidelines for exercise and training to optimize motor skill. Edinburgh; New York: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cho HM, Choi BY, Chang CH, Kim SH, Lee J, Chang MC, Son SM, Jang SH. The clinical characteristics of motor function in chronic hemiparetic stroke patients with complete corticospinal tract injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012;31:207–213. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2012-0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope M, Delpy DT. System for long-term measurement of cerebral blood and tissue oxygenation on newborn infants by near infra-red transillumination. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1988;26:289–294. doi: 10.1007/BF02447083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciunas SC, Brooks WM, Nudo RJ, Popescu EA, Choi IY, Lee P, Yeh HW, Savage CR, Cirstea CM. Motor and premotor cortices in subcortical stroke: proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy measures and arm motor impairment. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27:411–420. doi: 10.1177/1545968312469835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff RA. The pyramidal tract. Neurology. 1990;40:332–339. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney DM, Gonzalez A, Law WA. Amphetamine, haloperidol, and experience interact to affect rate of recovery after motor cortex injury. Science. 1982;217:855–857. doi: 10.1126/science.7100929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund HJ, Hummelsheim H. Premotor cortex in man: evidence for innervation of proximal limb muscles. Exp Brain Res. 1984;53:479–482. doi: 10.1007/BF00238179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund HJ, Hummelsheim H. Lesions of premotor cortex in man. Brain 108 (Pt 3) 1985:697–733. doi: 10.1093/brain/108.3.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsband U, Matsuzaka Y, Tanji J. Neuronal activity in the primate supplementary, pre-supplementary and premotor cortex during externally and internally instructed sequential movements. Neurosci Res. 1994;20:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzer R, Mahoney JR, Izzetoglu M, Izzetoglu K, Onaral B, Verghese J. fNIRS study of walking and walking while talking in young and old individuals. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:879–887. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irani F, Platek SM, Bunce S, Ruocco AC, Chute D. Functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS): an emerging neuroimaging technology with important applications for the study of brain disorders. Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;21:9–37. doi: 10.1080/13854040600910018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jane JA, Yashon D, DeMyer W, Bucy PC. The contribution of the precentral gyrus to the pyramidal tract of man. J Neurosurg. 1967;26:244–248. doi: 10.3171/jns.1967.26.2.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SH. The role of the corticospinal tract in motor recovery in patients with a stroke: a review. NeuroRehabilitation. 2009;24:285–290. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2009-0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS. Plasticity after brain lesions: contemporary concepts. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69:984–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapreli E, Athanasopoulos S, Papathanasiou M, Van Hecke P, Strimpakos N, Gouliamos A, Peeters R, Sunaert S. Lateralization of brain activity during lower limb joints movement. An fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2006;32:1709–1721. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim H, Schmidt B, Dart D, Beluk N, Huppert T. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) of brain function during active balancing using a video game system. Gait Posture. 2012;35:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Hong JH, Jang SH. The cortical effect of clapping in the human brain: A functional MRI study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2011;28:75–79. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2011-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz MJ, Wilson TW, Arpin DJ. Stride-time variability and sensorimotor cortical activation during walking. Neuroimage. 2012;59:1602–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H, Jang SH. Delayed recovery of gait function in a patient with intracerebral haemorrhage. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:378–380. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DG, Jang SH. Ultrasound guided alcohol neurolysis of musculocutaneous nerve to relieve elbow spasticity in hemiparetic stroke patients. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012;31:373–377. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2012-00806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff DR, Orihuela-Espina F, Elwell CE, Athanasiou T, Delpy DT, Darzi AW, Yang GZ. Assessment of the cerebral cortex during motor task behaviours in adults: a systematic review of functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) studies. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2922–2936. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CT. The neuroscience of human movement. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Tak S, Ye JC. Lipschitz-Killing curvature based expected Euler characteristics for p-value correction in fNIRS. J Neurosci Methods. 2012;204:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft AR, Smith GV, Forrester L, Whitall J, Macko RF, Hauser TK, Goldberg AP, Hanley DF. Comparing brain activation associated with isolated upper and lower limb movement across corresponding joints. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:131–140. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama K, Mori F, Nakajima K, Drew T, Aoki M, Mori S. Locomotor role of the corticoreticular-reticulospinal-spinal interneuronal system. Prog Brain Res. 2004;143:239–249. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)43024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza JE, Foundas AL. Clinical neuroanatomy: a neurobehavioral approach. New York; London: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miyai I, Tanabe HC, Sase I, Eda H, Oda I, Konishi I, Tsunazawa Y, Suzuki T, Yanagida T, Kubota K. Cortical mapping of gait in humans: a near-infrared spectroscopic topography study. Neuroimage. 2001;14:1186–1192. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrey S. Non-invasive NIR spectroscopy of human brain function during exercise. Methods. 2008;45:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pundik S, McCabe JP, Hrovat K, Fredrickson AE, Tatsuoka C, Feng IJ, Daly JJ. Recovery of post stroke proximal arm function, driven by complex neuroplastic bilateral brain activation patterns and predicted by baseline motor dysfunction severity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:394. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JR, Demyer W. The quantitative corticoid origin of pyramidal axons of Macaca rhesus. With some remarks on the slow rate of axolysis. Neurology. 1961;11:96–108. doi: 10.1212/wnl.11.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidtmann K, Fries W, Muller F, Koenig E. Effect of levodopa in combination with physiotherapy on functional motor recovery after stroke: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet. 2001;358:787–790. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05966-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi N, Chuma T, Matsuo Y, Watanabe I, Ikoma K. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of contralesional primary motor cortex improves hand function after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:2681–2686. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189658.51972.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JC, Tak S, Jang KE, Jung J, Jang J. NIRS-SPM: statistical parametric mapping for near-infrared spectroscopy. Neuroimage. 2009;44:428–447. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo SS, Chang MC, Kwon YH, Jung YJ, Jang SH. Corticoreticular pathway in the human brain: diffusion tensor tractography study. Neurosci Lett. 2012;508:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York DH. Review of descending motor pathways involved with transcranial stimulation. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:70–73. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198701000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]