Abstract

Few studies have focused on the epidemiology of Cryptosporidium in resource-challenged settings in China. We report a community-based cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection and its risk factors and associations with hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections. The prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection was 12.6% (95% confidence interval = 11.0–14.3). Individuals living in households with ≥ 5 family members and raising domestic pigs tended to have a greater risk of Cryptosporidium infection. In addition, Cryptosporidium infection was significantly associated with HBV infection. There were no significant associations of Cryptosporidium infection with HIV viral load and HBV viral load. Further studies are needed to determine the association of Cryptosporidium infection with HBV infection.

Background

Cryptosporidium is one of the most widespread diarrhea-causing parasites in humans globally and is the third most common causes of moderate-to-severe diarrhea in infants (aged 0–11 months) and the fifth most common diarrhea-causing pathogen in toddlers (aged 12–23 months), especially in low-resource settings.1,2 Although infections are manifested as self-limiting diarrhea in immunocompetent individuals, they can become severe and chronic in young children, elderly people, and immunocompromised patients.3 Cryptosporidium is a major source of opportunistic coinfection in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients.4 Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is frequently present in individuals seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) because of shared transmission routes. China has the world's largest burden of HBV infection with an estimated overall prevalence of 7–8% and nearly 300,000 deaths from HBV-related liver diseases every year.5,6 Chronic HBV infection may increase the susceptibility to human parasite infection due to damaged T-cell function and subsequent depressed production of cytokines.6,7 It has been indicated that HBV infection was associated with Ascaris lumbricoides.8 Yet so far, few studies have attempted to examine the relationship between HBV infection and Cryptosporidium infection.

In China, since the first report of human Cryptosporidium infection in 1987, growing attention has been paid to Cryptosporidium and its existence has been confirmed in at least 14 out of 32 provinces in China.9,10 Although there is a considerable amount of information on cryptosporidiosis in children and diarrheal patients or HIV-infected individuals, few studies have focused on the overall prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection and its determinants in general population in China.9,11 Little is known about the ecology of Cryptosporidium in areas with frequent human–animal contacts, which also bear a heavy burden of both HBV and HIV endemics.

The Yi Autonomous Prefecture is an underprivileged region with a high prevalence of HIV, holding more than half (53%) of the HIV/AIDS patients in Sichuan Province, China.12 This prefecture also bears a high HBV burden.13 This study investigates Cryptosporidium infection in residents in three selected towns. Local residents are engaged in grain cultivation and animal husbandry with high human–livestock interactions. The current study examined the occurrence of Cryptosporidium infection and its determinants in a population of mainly Yi people. We also examined the coexistence of HBV and HIV infections with Cryptosporidium infection and the possibility for HBV and HIV viral loads as predictors for Cryptosporidium infection.

Methods

Study site.

The study took place in a Yi autonomous prefecture of southwestern China. It has a population of approximately 4.9 million people, of which almost half belong to the Yi ethnic group.14 This region is noted for its HIV/AIDS endemic. Rugged mountainous terrain and the sparsely scattered rural populations have hindered local economic development. The present study was conducted in three towns (A, B, and C) from two counties (A from Mg County, B and C from Pg County). Pg County and Mg County were state-level poverty-stricken counties. These towns were selected because they shared similar social demographic characters (such as age structure, education level, and proportion of Yi people), meanwhile these towns were presumed to have high prevalence rate of intestinal parasites, including Cryptosporidium spp. According to the 2010 Chinese Census, the population of A, B, and C towns were approximately 7,000, 3,000, and 10,000, respectively.15 Local residents are engaged in mixed agriculture, have frequent human contacts with livestock, and are at a great risk for zoonotic diseases.

Survey data and sample collections.

The study was carried out during the period from October 2014 to August 2015. To improve participant enrollment, village chiefs were first contacted and invited to the preparation meetings for the field work. The village chiefs then explained the purpose, procedures, potential risk and discomforts, and benefits of the study to the villagers, invited them to a scheduled survey, and distributed clean plastic containers for stool sample collection. The participants were residents of the village, who provided informed consent by themselves or the guardians and were willing to provide a single stool specimen. Participants were instructed to provide their fecal samples of at least 30 g collected in the morning at home and to avoid contamination. Concurrent with human fecal sample collection, a standardized questionnaire was administered to each participant by trained health workers. The survey focused on sociodemographic characteristics (including age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, occupation, annual family income, and number of persons/houses), personal hygiene (including drinking unboiled water, washing hands before meals and after defecation, and washing before eating raw fruits and raw vegetables), raising domestic animals, and access to safe water and sanitation facilities.

Stool samples were collected from each participant. All the participants had a finger prick to obtain about 1 mL of blood and were screened for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV), and anti-HIV antibodies by using the Diagnostic Kit for HBV (Colloidal Gold) (Livzon Pharmaceutical Group Inc., Zhuhai, China), the Diagnostic Kit for HCV (Colloidal Gold) (Livzon Pharmaceutical Group Inc.), and the Diagnostic Kit for HIV (Colloidal Gold) (Livzon Pharmaceutical Group Inc.). Colloidal gold kits are convenient and rapid tools for detecting HBsAg.16 Those with positive screening results were asked to provide a 5 mL blood sample for confirmation tests. Both stool and blood samples were transported to the local Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laboratory as soon as possible.

Laboratorial procedures.

All the stool specimens were processed and labeled with a unique identification number at the same day that they were collected. Modified acid-fast staining was used to detect the existence of Cryptosporidium oocysts. Two thin smears were prepared from each freshly collected stool sample. Slides were air-dried and heat fixed using a candle flame for 5 seconds. The smears were stained with carbol fuchsin for 10 minutes, thoroughly washed with tap water, and then decolorized with 3% acid alcohol for 2 minutes. Slides were rinsed in tap water and then counterstained with methylene blue for another 30 seconds. Finally, these slides were rinsed thoroughly and air-dried. In this method, Cryptosporidium oocysts appear as pink to red, spherical to ovoid bodies ranged between 4 and 6 μm against blue background of debris. A stool was labeled as positive if the size of the oocysts ranged between 4 and 6 μm. Every smear was examined by two separate technicians and a third examiner was called in, if there was a disagreement.

CD4 cell counts were measured in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid blood using Becton Dickinson (BD) FACScount (version 1.5, Franklin Lakes, NJ; BD FACScount™ controls, Cat No.: 340166; BD FACScount™ reagents, Cat No.: 340167). Plasma aliquots were stored at −20°C and were then transported in ice to Shanghai and tested for viral load by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Plasma viral loads of HBV, HCV, and HIV were measured by using the diagnostic kit for quantification of HBV DNA, HCV RNA, and HIV-1 RNA (PCR-Fluorescence Probing) (DaAn Gene Group Inc., Zhongshan, China) in the Center for Tropical Disease Research at Fudan University. Standard procedures for sample preparation, storage, and testing were strictly followed. Not all patients had the test results of HIV or HBV viral load due to inadequate plasma aliquots. CD4 cell count was unavailable for some HIV-infected individuals because we had no access to the equipment needed at some of the local hospitals.

Ethical considerations.

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Ethical Institute of the School of Public Health, Fudan University. All participants provided consent and were informed of their right to refuse to participate or withdraw at any point during the study.

Statistical analysis.

Data were input and cross-checked by using the EpiData software (version 3.1; The EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). Statistical analyses were conducted with the SPSS software (version 20.0; IBM SPSS Institute, Inc., Chicago, IL). Demographic characteristics and risk factors were coded as categorical variables. We used Pearson χ2 tests to compare differences between different demographic and risk groups and crude odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed. Variables with a P value ≤ 0.2 from univariable results were included in the initial multivariable logistic regression model. We then used a backward selection approach to produce a final multivariable model with all variable P value ≤ 0.05.17,18 We accounted for familial clustering with generalized estimating equations.18,19 We also developed separate multivariable models of risk factors for Cryptosporidium in each town. In addition, Pearson χ2 test was used to examine the associations of Cryptosporidium sp. infection with HBV infection, HIV infection, HBV and HIV viral loads, and CD4 cell count. Fisher's exact test was used when indicated. P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant in all the analyses.

Results

A total of 1,635 individuals were investigated with mean age of 29 years, ranging from 1 to 82 years. Supplemental Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics and personal behaviors of the study population. Participants were predominantly of Yi people (96.6%). Of these, 1,003 (61.3%) were female, and nearly half were unmarried (48.4%).

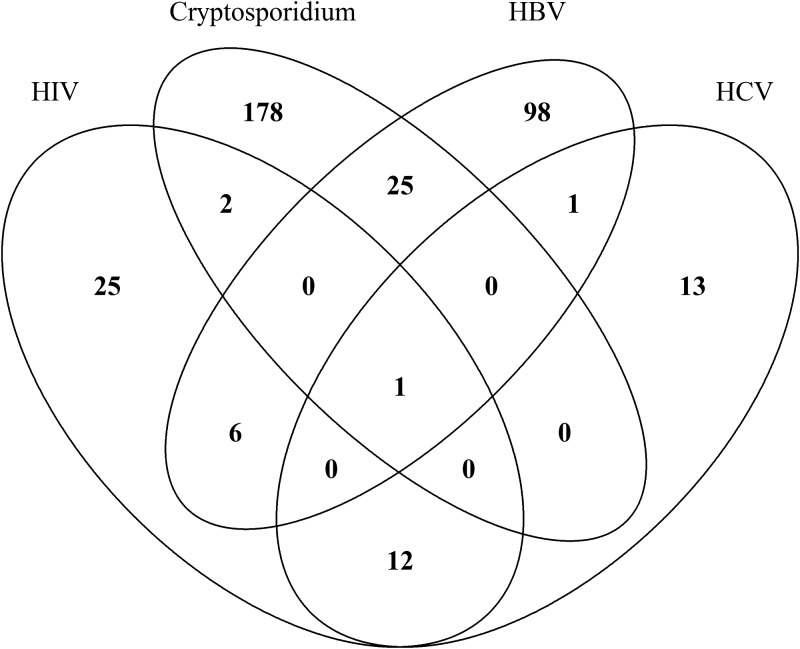

The prevalences of HIV, HBV, HCV, and Cryptosporidium infections were 2.8% (95% CI = 2.1–3.7), 8.0% (95% CI = 6.7–9.4), 1.7% (95% CI = 1.1–2.4), and 12.6% (95% CI = 11.0–14.3), respectively (Table 1). The prevalences of HIV/Cryptosporidium, HBV/Cryptosporidium, and HCV/Cryptosporidium coinfections were 0.1% (95% CI = 0–0.5), 1.6% (95% CI = 1.0–2.3), and 0.2% (95% CI = 0–0.3), respectively. Figure 1 shows the distribution of mixed infections in this study.

Table 1.

Prevalence of infections and coinfections of HBV, HIV, HCV, and Cryptosporidium

| No. of participants | Cases | Prevalence (% [95% CI]) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | 1,635 | 46 | 2.8 (2.1–3.7) |

| HBV | 1,635 | 131 | 8.0 (6.7–9.4) |

| HCV | 1,635 | 27 | 1.7 (1.1–2.4) |

| Cryptosporidium | 1,635 | 206 | 12.6 (11.0–14.3) |

| Coinfection | |||

| HIV and Cryptosporidium | 1,635 | 3 | 0.2 (0–0.5) |

| HBV and Cryptosporidium | 1,635 | 26 | 1.6 (1.0–2.3) |

| HCV and Cryptosporidium | 1,635 | 1 | 0.1 (0–0.3) |

CI = confidence interval; HBV = hepatitis B virus; HCV = hepatitis C virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing the distribution of mixed infections in this study.

Table 2 shows potential risk factors associated with Cryptosporidium infection. Significant variations were observed in the risk of Cryptosporidium infection including county of residence, number of family members, raising domestic pigs, and HBV infection. The prevalence of Cryptosporidium was markedly lower in town A (4.6%) compared with town B (11.9%) or town C (15.9%) (Table 2). Having ≥ 5 family members was significantly associated with an increased risk of Cryptosporidium infection (adjusted OR [aOR] = 1.44, 95% CI = 0.99–2.09, P = 0.05). Individuals living with domestic pigs tended to have a greater odds of Cryptosporidium infection (aOR = 1.70, 95% CI = 1.11–2.61, P = 0.01). In addition, HBV was a predictor for increased risk of Cryptosporidium infection (aOR = 1.90, 95% CI = 1.18–3.05, P < 0.01). We found no significant associations of Cryptosporidium infection with HIV or HCV infection and drinking unboiled water, eating raw food, and not washing hands before meals or after defecation (Table 2). Further analysis by each town showed that only HBV infection was positively associated with Cryptosporidium infection (aOR = 4.07, 95% CI = 1.01–16.46, P < 0.05) in town A. HBV infection (aOR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.15–4.85, P = 0.02) and raising domestic pigs (aOR = 3.61, 95% CI = 1.72–7.56, P < 0.01) were associated with Cryptosporidium infection in town B. No risk factor was found in town C (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable binary logistic generalized estimating equation regression analyses of risk factors for Cryptosporidium infection

| Variable | Participants with Cryptosporidium infection N (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Town | |||||

| A | 12/260 (4.6) | 1.00 | < 0.01 | 1.00 | |

| B | 73/615 (11.9) | 2.68 (1.43–5.04) | < 0.01 | 3.01 (1.58–5.76) | 0.001 |

| C | 121/760 (15.9) | 3.85 (2.08–7.12) | < 0.01 | 4.06 (2.20–7.52) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 84/632 (13.3) | 1.16 (0.85–1.57) | 0.35 | ||

| Female | 122/1,003 (12.2) | 1.00 | |||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 0–9 | 44/331 (13.3) | 1.00 | |||

| 10–19 | 49/340 (14.4) | 1.08 (0.68–1.70) | 0.76 | ||

| 20–29 | 17/158 (10.8) | 0.71 (0.38–1.31) | 0.28 | ||

| 30–39 | 27/272 (9.9) | 0.68 (0.41–1.15) | 0.15 | ||

| 40–49 | 33/291 (11.3) | 0.76 (0.46–1.25) | 0.29 | ||

| 50–59 | 24/166 (14.5) | 1.01 (0.58–1.75) | 0.99 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 12/76 (15.8) | 1.04 (0.51–2.15) | 0.91 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Yi | 200/1,580 (12.7) | 1.00 | |||

| Other | 6/55 (10.9) | 0.72 (0.28–1.84) | 0.50 | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Not married | 107/791 (13.5) | 1.00 | |||

| First marriage | 74/648 (11.4) | 0.78 (0.57–1.08) | 0.14 | ||

| Others | 25/196 (12.8) | 0.82 (0.51–1.34) | 0.43 | ||

| No. of persons in household | |||||

| < 5 | 41/427 (9.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 159/1,167 (13.6) | 1.52 (1.05–2.20) | 0.03 | 1.44 (0.99–2.09) | 0.05 |

| Education | |||||

| Illiterate | 88/721 (12.2) | 1.00 | |||

| Primary school | 101/786 (12.8) | 1.11 (0.81–1.52) | 0.51 | ||

| Middle school or above | 17/128 (13.3) | 1.09 (0.61–1.96) | 0.78 | ||

| Annual family income (yuan) | |||||

| < 3,000 | 83/575 (14.4) | 1.00 | |||

| 3,000–4,999 | 50/441 (11.3) | 0.75 (0.51–1.10) | 0.14 | ||

| 5,000–9,999 | 33/257 (12.8) | 0.95 (0.61–1.48) | 0.83 | ||

| ≥ 10,000 | 39/345 (11.3) | 0.77 (0.51–1.17) | 0.22 | ||

| Raising cattle | |||||

| No | 139/1,075 (12.9) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 67/560 (12.0) | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 0.61 | ||

| Raising pigs | |||||

| No | 38,399 (9.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 168/1,236 (13.6) | 1.54 (1.05–2.26) | 0.03 | 1.70 (1.11–2.61) | 0.01 |

| Raising horses | |||||

| No | 186/1,462 (12.7) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 20/173 (11.6) | 0.88 (0.53–1.46) | 0.62 | ||

| Raising poultry | |||||

| No | 56/506 (11.1) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 150/1,129 (13.3) | 1.26 (0.90–1.76) | 0.18 | ||

| Raising cats and/or dogs | |||||

| No | 124/1,010 (12.3) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 82/625 (13.1) | 1.06 (0.78–1.44) | 0.73 | ||

| Source of drinking water | |||||

| Spring | 156/1,183 (13.2) | 1.00 | |||

| Wells | 28/265 (10.6) | 0.79 (0.52–1.22) | 0.29 | ||

| River or pond | 20/170 (11.8) | 0.92 (0.55–1.54) | 0.76 | ||

| Drinking unboiled water | |||||

| Never | 5 (10.9) | 1.00 | |||

| Occasionally | 26 (11.9) | 1.44 (0.48–4.37) | 0.46 | ||

| Always | 175 (12.9) | 1.48 (0.52–4.18) | 0.52 | ||

| Washing hands before meals | |||||

| Always | 22/368 (12.3) | 1.00 | |||

| Occasionally | 128/985 (13.0) | 1.16 (0.74–1.80) | 0.52 | ||

| Never | 45/371 (12.1) | 1.07 (0.64–1.79) | 0.79 | ||

| Washing hands after defecation | |||||

| Always | 32/282 (11.3) | 1.00 | |||

| Occasionally | 122/924 (13.2) | 1.31 (0.84–2.06) | 0.24 | ||

| Never | 52/419 (12.4) | 1.25 (0.76–2.06) | 0.39 | ||

| Washing fruits and raw vegetables before eating | |||||

| No fruits and raw vegetables | 25/196 (12.1) | 1.00 | |||

| Always | 70/436 (16.1) | 1.17 (0.70–1.94) | 0.27 | ||

| Occasionally or never | 111/1,003 (11.1) | 0.77 (0.48–1.23) | 0.54 | ||

| HIV infection | |||||

| No | 203/1,589 (12.8) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 3/46 (6.5) | 0.51 (0.16–1.66) | 0.26 | ||

| HBV infection | |||||

| No | 180/1,504 (12.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 26/131 (19.8) | 1.82 (1.14–2.90) | 0.01 | 1.90 (1.18–3.05) | < 0.01 |

| HCV infection | |||||

| No | 205/1,608 (12.7) | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1/27 (3.7) | 0.26 (0.04–1.93) | 0.19 | ||

CI = confidence interval; HBV = hepatitis B virus; HCV = hepatitis C virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; OR = odds ratio.

The number of diagnosed cases with Cryptosporidium infection was the highest for young adolescents aged 10–19 years, followed by children aged 0–9 years (Table 1). Table 3 shows the age and sex distributions of Cryptosporidium prevalence.

Table 3.

Age and sex distributions of Cryptosporidium infection prevalence

| Age group (years) | Prevalence of Cryptosporidium N (% [95% CI]) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Male | Female | P value | |

| 0–4 | 7/26 (26.9 [11.6–47.8]) | 7/21 (33.3 [14.6–57.0]) | 0/5 (0) | 0.28 |

| 5–9 | 37/305 (12.1 [8.7–16.3]) | 23/149 (15.4 [10.0–22.3]) | 14/156 (9.0 [5.0–14.6]) | 0.11 |

| 10–14 | 41/259 (15.8 [11.6–20.9]) | 25/121 (20.7 [13.8–29.0]) | 16/138 (11.6 [6.8–18.1]) | 0.06 |

| 15–19 | 8/81 (9.9 [4.4–18.5]) | 4/33 (12.1 [3.4–28.2]) | 4/48 (8.3 [2.3–20.0]) | 0.71 |

| 20–24 | 6/67 (9.1 [3.3–18.5]) | 3/25 (12.5 [2.5–31.2]) | 3/42 (7.1 [1.5–19.5]) | 0.66 |

| 25–29 | 11/92 (12.0 [6.1–20.4]) | 4/30 (13.3 [3.8–30.7]) | 7/62 (11.3 [4.7–21.9]) | 0.75 |

| 30–34 | 13/120 (10.8 [5.9–17.8]) | 2/28 (7.1 [0.9–23.5]) | 11/92 (12.0 [6.1–20.4]) | 0.73 |

| 35–39 | 14/152 (9.2 [5.1–15.0]) | 2/48 (4.2 [0.1–14.3]) | 12/104 (11.5 [6.1–19.3]) | 0.23 |

| 40–44 | 15/148 (10.1 [5.8–16.2]) | 4/44 (8.3 [2.5–21.7]) | 11/100 (11.0 [5.6–18.8]) | 0.77 |

| 45–49 | 18/143 (12.6 [7.6–19.2]) | 2/43 (4.7 [0.1–15.8]) | 16/100 (16.0 [9.4–24.7]) | 0.06 |

| 50–54 | 14/90 (15.6 [8.8–24.7]) | 1/25 (4.0 [0.1–20.4]) | 13/65 (20.0 [11.1–31.8]) | 0.10 |

| 55–59 | 10/76 (13.2 [6.5–22.9]) | 3/26 (11.5 [2.4–30.2]) | 7/50 (14.0 [5.8–26.7]) | 1.00 |

| ≥ 60 | 12/76 (15.8 [8.4–26.0]) | 4/35 (11.4 [3.2–26.7]) | 8/41 (19.5 [8.8–34.9]) | 0.38 |

| Total | 206/1,635 (12.6 [11.0–14.3]) | 84/632 (13.3 [10.7–16.2]) | 122/1,003 (12.2 [10.2–14.3]) | 0.54 |

CI = confidence interval. P value was calculated by Fisher's exact test.

Supplemental Table 3 shows that Cryptosporidium infection was not significantly associated with HIV infection (Fisher's exact P = 0.26), which was not modified by the presence of HBV or HCV infection. The number of cases with HCV infection was small in the current study.

HBV infection was significantly associated with Cryptosporidium infection overall (Fisher's exact P < 0.01; Table 4) or in those free from HIV and HCV infections (Fisher's exact P = 0.01). For HIV-infected persons, there was no significant association between HBV and Cryptosporidium infections (Fisher's exact P = 1.00). For patients coinfected with HIV and HCV, HBV increased the risk of Cryptosporidium infection although this association was not significant (Fisher's exact P = 0.08). For HCV-positive individuals, it was not feasible to access the association of HBV and Cryptosporidium infections because of small number.

Table 4.

Crude association between HBV infection and Cryptosporidium infection stratified by status of HIV and/or HCV infections

| HIV (n) | HBV infection (n) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| Cryptosporidium infection (n) | Total | No | 1,324 | 105 | 0.01 |

| Yes | 180 | 26 | |||

| HIV(−) and HCV (−) | No | 1,274 | 98 | 0.01 | |

| Yes | 178 | 25 | |||

| HIV (+) and HCV (−) | No | 25 | 6 | 1 | |

| Yes | 2 | 0 | |||

| HIV (−) and HCV (+) | No | 13 | 1 | NA | |

| Yes | 0 | 0 | |||

| HIV (+) and HCV (+) | No | 12 | 0 | 0.08 | |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | |||

HBV = hepatitis B virus; HCV = hepatitis C virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; NA = not applicable. P value was calculated by Fisher's exact test.

Table 5 shows the association between Cryptosporidium infection and HIV viral load, HBV viral load, and CD4+ T lymphocyte count. Results of HIV and HBV viral loads were available for 26 and 98 participants, respectively. There were no significant associations of Cryptosporidium infection with HIV and HBV viral loads (Fisher's exact P = 1.00 and 0.66, respectively). The result of CD4+ T lymphocyte count was available for 23 patients. HIV-positive individuals with lower CD4 cell count (defined as < 200/μL) tended to have a greater risk of Cryptosporidium infection, although it did not reach statistical significance (Fisher's exact P = 0.06).

Table 5.

Association between Cryptosporidium infection and HIV viral load, HBV viral load, and CD4+ T lymphocyte count

| N (%) | No. of participants (%) with Cryptosporidium infection | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV viral load, IU/mL | 0.53 | ||

| < 105 | 9/26 (34.6) | 0 | |

| ≥ 105 | 17/26 (65.4) | 2 (11.8) | |

| HBV viral load, IU/mL | 0.66 | ||

| < 30 (undetectable) | 15/98 (15.3) | 2 (13.3) | |

| 30–99,999 | 40/98 (40.8) | 10 (25.0) | |

| ≥ 100,000 | 43/98 (43.9) | 8 (18.6) | |

| CD4+ T lymphocyte (no./μΛ) | |||

| < 200 | 6/23 (26.1) | 2 (33.3) | 0.06 |

| ≥ 200 | 17/23 (73.9) | 0 | |

HBV = hepatitis B virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus. P value was calculated by Fisher's exact test.

Discussion

High prevalence of Cryptosporidium and geographical differences.

Our results demonstrated that the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in rural southwestern China was 12.6% (95% CI = 11.0–14.3). Our prevalence estimates were considerably higher than the prevalences detected by modified acid-fast staining of fecal smears in similar populations from Yuxi, southern areas of Guizhou and Shiyan, China.11,20,21 The high prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection documented in our study may be due to poor sanitation, poverty, and lack of diagnostic tools.3,22 Since our study was performed in late summer and early autumn, these results might also reflect the seasonality of Cryptosporidium transmission.23–25 We noted that the prevalence of Cryptosporidium was different among the towns and therefore carried out a stratified analysis. Risk factors varied from town to town. Such geographical variations of risk factors might be responsible for the differences of Cryptosporidium prevalence among towns.

Age and sex distribution of Cryptosporidium infection.

Although Cryptosporidium can infect people of all ages, the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection was most common among children aged 10–14 years and elderly adults aged ≥ 60 years, followed by those aged 50–54 years and young children aged 0–9 years. Similar findings have been noted in the other studies, which reflected the fact that children and the elderly are more susceptible to Cryptosporidium infection.24 Overall, the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection was similar for males and females.

Assessment of risk factors for Cryptosporidium infection.

Participants from town A were at much lower risk of Cryptosporidium infection than participants from towns B and C. The difference remained after adjustment for covariates, which might underscore the importance of geographical distribution of Cryptosporidium. Overcrowding has been associated with Cryptosporidium infection, specifically with Cryptosporidium huminis.26 A high secondary infection rate (39%) was reported in households with children diagnosed with Cryptosporidium infection.27 In the present study, we found a significant association between having more than five family members and Cryptosporidium infection. This might be related to the crowded conditions in a household, which may translate into more frequent human-to-human contact, especially with children diarrhea, thus increasing the risk of Cryptosporidium transmission within families.28–30

It was previously found that residents who raised livestock or poultry were more likely to be infected with Cryptosporidium in this area, supporting the hypothesis of zoonotic transmission of domestic animals. Domestic pigs in this region were mostly free ranging and tended to be around the residences. Humans can be easily infected through direct contact with them or by indirect contact with their infective feces on the ground or ingestion of contaminated food or water. However, we identified no significant association of Cryptosporidium infection with other agricultural/domestic animals including cattle, horses, poultry, cats, and dogs. Previous studies also found that raising cattle, especially calve, was a risk factor for human Cryptosporidium infection.3,31 In this area, cattle usually graze on the nearby hills away from human settlements, thus human–cattle contacting is less frequent. Horses, cats, and dogs are primarily infected with host-specific Cryptosporidium species or genotypes, and therefore, the actual risk of zoonotic transmission of these animals may be low.32,33 Nevertheless, genotyping and subtyping studies of Cryptosporidium from domestic animals will help to clarify zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium. Surprisingly, unsafe drinking water sources were not found to increase the risk of Cryptosporidium infection, which could be the result of degradation or improper tapping of the water distribution system, exposing water to environmental contamination.34 In addition, drinking unboiled water was found to be associated with Cryptosporidium infection in this study, for various reasons. First, other transmission pathways, such as animal contact, or anthroponotic transmission might play a relatively important role as we found raising pigs and living in a household with ≥ 5 members were associated with greater odds of Cryptosporidium infection. Routinely drinking boiled water at home does not necessarily prevent drinking untreated water, for instance, during farm work far away on the hills or during a visit to a neighbor's house.

Associations of Cryptosporidium infection with HBV, HIV, and HCV infections and with viral loads and CD4 cell counts as indicators of immunity changes.

Intriguingly, we found that Cryptosporidium infection was significantly associated with HBV infection, but not with HCV infection. To determine whether the immunity changes caused by HBV lead to a greater risk of Cryptosporidium infection, we examined the association between the levels of HBV DNA and prevalence of Cryptosporidium. HBV viral load was used as a surrogate marker for host immunity status and was only divided into three categories due to small sample size: < 30 IU/mL (undetectable), 30–99,999 IU/mL, and ≥ 100,000 IU/mL. Although the prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection increased with HBV DNA levels, this difference was not statistically significant suggesting that HBV viral load is not likely a suitable predictor of risk of Cryptosporidium infection in HBV-infected individuals. Further study is needed to determine the interactions between HBV and Cryptosporidium infections.

Previous studies have identified HIV infection as a risk factor for Cryptosporidium infection.35,36 Unexpectedly, HIV did not appear significantly related to Cryptosporidium infection in our study. One possible reason for this is that most of HIV-infected individuals were less immunocompromised based on their HIV RNA levels and CD4 cell counts. Our study showed that quantitative HIV RNA levels and CD4 cell counts did not correlate with the risk of Cryptosporidium infection, but the two cases of Cryptosporidium/HIV coinfection with available test results occurred in patients with HIV viral loads ≥ 105 IU/mL and CD4 cell counts < 200/μL. It should be noted that our results were preliminary and based on a small sample size.

Broadly speaking, the immunosuppression imposed by HIV results in reduced rates of HBV and HCV clearance and increases the risk of chronic liver diseases in the setting of coinfection.37 Conversely, existing evidence points out that HBV and HCV coinfections are associated with worse outcomes for HIV-positive patients.37–39 In addition, HBV/HCV coinfection may accelerate liver disease progression and increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.40 Thus the question of whether the interplay among HIV, HBV, and HCV infections influences Cryptosporidium infection is important. When stratified by the status of HBV infection, we found no significant association between Cryptosporidium and HIV infections. For HIV-negative–HCV-negative individuals, HBV was associated with an increased risk of Cryptosporidium infection, but not for HIV-positive–HCV-negative persons. For patients coinfected with HIV and HCV, HBV increased the risk of Cryptosporidium infection although this association was not significant. Overall, the risk of Cryptosporidium infection was strongly associated with HBV infection, but not with HIV infection and HIV/HBV coinfection. Coinfection with HIV might neutralize the impact of HBV infection on the risk of Cryptosporidium infection. However, since the number of participants coinfected with Cryptosporidium and viruses was small, our data only help to generating hypothesis concerning the interactions of these viruses and changes in the host immune system and subsequent Cryptosporidium infection.

Our study has several limitations. First, there were fewer males than females because many young males migrated to the cities to make a living. This underrepresentation of young males may lead to an underestimate of the prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV infections, as they are at greater risk than other age groups. Second, we collected only one stool sample from each participant, which may result in an underestimate of the true prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection. Also, misclassification may have occurred because colloidal gold kits are slightly less sensitive compared with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and the sensitivity of modified acid-fast staining technique is 70% compared with that of immunofluorescent antibody stains.16,23 Because of limited research funds, data on Cryptosporidium genotypes were not available. Further research should include molecular analysis to determine the roles of anthroponotic and zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium in rural China. In view of these limitations, the findings should be interpreted discreetly.

Conclusions

Our results reveal a high prevalence of Cryptosporidium infection in rural areas of southwest China and its close associations with HBV infection and raising domestic pigs. Further studies are needed to clarify the association of Cryptosporidium infection with HBV infection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the local CDC personnel for assistance in field investigation and sample collection.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Ya Yang, Yibiao Zhou, Wanting Cheng, Xiang Pan, Penglei Xiao, Yan Shi, Jianchuan Gao, Xiuxia Song, and Qingwu Jiang, Fudan University School of Public Health, Shanghai, China, E-mails: yayang14@fudan.edu.cn, z_yibiao@hotmail.com, 15211020042@fudan.edu.cn, 14211020063@fudan.edu.cn, xiaopl90@163.com, 13211020008@fudan.edu.cn, 13211020003@fudan.edu.cn, xxsong@fudan.edu.cn, and jiangqw@fudan.edu.cn. Yue Chen, School of Epidemiology, Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, E-mail: yue.chen@uottawa.ca.

References

- 1.Liu J, Platts-Mills JA, Juma J, Kabir F, Nkeze J, Okoi C, Operario DJ, Uddin J, Ahmed S, Alonso PL, Antonio M, Becker SM, Blackwelder WC, Breiman RF, Faruque AS, Fields B, Gratz J, Haque R, Hossain A, Hossain MJ, Jarju S, Qamar F, Iqbal NT, Kwambana B, Mandomando I, McMurry TL, Ochieng C, Ochieng JB, Ochieng M, Onyango C, Panchalingam S, Kalam A, Aziz F, Qureshi S, Ramamurthy T, Roberts JH, Saha D, Sow SO, Stroup SE, Sur D, Tamboura B13, Taniuchi M, Tennant SM, Toema D, Wu Y, Zaidi A, Nataro JP, Kotloff KL, Levine MM, Houpt ER. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children: a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. Lancet. 2016;388:1291–1301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31529-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, Wu Y, Sow SO, Sur D, Breiman RF, Faruque AS, Zaidi AK, Saha D, Alonso PL, Tamboura B, Sanogo D, Onwuchekwa U, Manna B, Ramamurthy T, Kanungo S, Ochieng JB, Omore R, Oundo JO, Hossain A, Das SK, Ahmed S, Qureshi S, Quadri F, Adegbola RA, Antonio M, Hossain MJ, Akinsola A, Mandomando I, Nhampossa T, Acácio S, Biswas K, O'Reilly CE, Mintz ED, Berkeley LY, Muhsen K, Sommerfelt H, Robins-Browne RM, Levine MM. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abeywardena H, Jex AR, Gasser RB. A perspective on Cryptosporidium and Giardia, with an emphasis on bovines and recent epidemiological findings. Adv Parasitol. 2015;88:243–301. doi: 10.1016/bs.apar.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Connor RM, Shaffie R, Kang G, Ward HD. Cryptosporidiosis in patients with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2011;25:549–560. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437e88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vellozzi C, Averhoff F. An opportunity for further control of hepatitis B in China? Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:10–11. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trépo C, Chan HLY, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014;384:2053–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung M, Pape GR. Immunology of hepatitis B infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:43–50. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao P, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Yang Y, Shi Y, Gao J, Yihuo W, Song X, Jiang Q. Prevalence and risk factors of Ascaris lumbricoides (Linnaeus, 1758), Trichuris trichiura (Linnaeus, 1771) and HBV infections in Southwestern China: a community-based cross sectional study. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:661. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1279-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lv S, Tian L, Liu Q, Qian M, Fu Q, Steinmann P, Chen J, Yang G, Yang K, Zhou X. Water-related parasitic diseases in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:1977–2016. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10051977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han F, Tan W, Zhou X. Two case reports of cryptosporidiosis in Nanjing. Jiangsu Med J. 1987;12:692. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang HY, Rong JQ, Wu GP. Investigation on cryptosporidiosis in some southern areas of Guizhou Province. J Trop Med. 2006;6:717–718. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong C, Huang ZJ, Martin MC, Huang J, Liu H, Deng B, Lai W, Liu L, Yang Y, Hu Y, Qin G, Zhang L, Song Z, Wei D, Nan L, Wang Q, Deng H, Zhang J, Wong FY, Yang W. The impact of social factors on human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus co-infection in a minority region of Si-chuan, the People's Republic of China: a population-based survey and testing study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li K, Wu G, Xu H, Zou K. Prevalence of HBV in a mountainous area. Mod Prev Med. 2007;34:2557–2558. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y, Wang Q, Liang S, Gong Y, Yang M, Nie S, Nan L, Yang A, Liao Q, Yang Y, Song XX, Jiang QW. HIV-, HCV-, and co-infections and associated risk factors among drug users in southwestern China: a township-level ecological study incorporating spatial regression. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NBS . Tabulation on the 2010 Census of the People's Republic of China (In Chinese) Beijing, China: National Bureau of Statistics; 2012. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm Available at. Accessed October 20, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Shao T, Zhou C, Lv W. The comparison between colloidal gold stripes and ELISA in human albumin HBsAg detection. Int J Lab Med. 2014;3:2550–2554. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dippel S, Dolezal M, Brenninkmeyer C, Brinkmann J, March S, Knierim U, Winckler C. Risk factors for lameness in cubicle housed Austrian Simmental dairy cows. Prev Vet Med. 2009;90:102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Condon J, Kelly G, Bradshaw B, Leonard N. Estimation of infection prevalence from correlated binomial samples. Prev Vet Med. 2004;64:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanley JA. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu M, Zhu J, Wang S, Song M. A survey of Cryptosporidium infection among humans being in Shiyan, China. J Path Biol. 2009;4:685–686. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan B, He XY, Huang ZM, Wang WL, Bo WF, Su Q. Epidemiological investigation of cryptosporidiosis in Yuxi district. Chin J Pest Contr. 1992;4:228–230. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Speich B, Croll D, Furst T, Utzinger J, Keiser J. Effect of sanitation and water treatment on intestinal protozoa infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:87–99. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Checkley W, White AC, Jaganath D, Arrowood MJ, Chalmers RM, Chen X, Fayer R, Griffiths JK, Guerrant RL, Hedstrom L, Huston CD, Kotloff KL, Kang G, Mead JR, Miller M, Petri WA, Jr, Priest JW, Roos DS, Striepen B, Thompson RC, Ward HD, Van Voorhis WA, Xiao L, Zhu G, Houpt ER. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Painter JE, Hlavsa MC, Collier SA, Xiao L, Yoder JS. Cryptosporidiosis surveillance-United States, 2011–2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015;64:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jagai JS, Castronovo DA, Monchak J, Naumova EN. Seasonality of cryptosporidiosis: a meta-analysis approach. Environ Res. 2009;109:465–478. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korpe PS, Haque R, Gilchrist C, Valencia C, Niu F, Lu M, Ma JZ, Petri SE, Reichman D, Kabir M, Duggal P, Petri WA., Jr Natural history of cryptosporidiosis in a longitudinal study of slum-dwelling Bangladeshi children: association with severe malnutrition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e4564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman RD, Zu SX, Wuhib T, Lima AA, Guerrant RL, Sears CL. Household epidemiology of Cryptosporidium parvum infection in an urban community in northeast Brazil. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:500–505. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-6-199403150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman RD, Sears CL, Moore SR, Nataro JP, Wuhib T, Agnew DA, Guerrant RL, Lima AA. Longitudinal study of Cryptosporidium infection in children in northeastern Brazil. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:167–175. doi: 10.1086/314820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katsumata T, Hosea D, Wasito EB, Kohno S, Hara K, Soeparto P, Ranuh IG. Cryptosporidiosis in Indonesia: a hospital-based study and a community-based survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:628–632. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy SL, DeLong SM, Stenzel SA, Shiferaw B, Roberts JM, Khalakdina A, Marcus R, Segler SD, Shah DD, Thomas S, Vugia DJ, Zansky SM, Dietz V, Beach MJ, Emerging Infections Program FoodNet Working Group Risk factors for sporadic cryptosporidiosis among immunocompetent persons in the United States from 1999 to 2001. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2944–2951. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.2944-2951.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsons MB, Travis D, Lonsdorf EV, Lipende I, Roellig DMA, Kamenya S, Zhang H, Xiao L, Gillespie TR. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in humans, wild primates, and domesticated animals in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e3529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucio-Forster A, Griffiths JK, Cama VA, Xiao L, Bowman DD. Minimal zoonotic risk of cryptosporidiosis from pet dogs and cats. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fayer R, Lihua X. Cryptosporidium and Cryptosporidiosis. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onda K, LoBuglio J, Bartram J. Global access to safe water: accounting for water quality and the resulting impact on MDG progress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:880–894. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9030880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedersen SH, Wilkinson AL, Andreasen A, Warhurst DC, Kinung'Hi SM, Urassa M, Mkwashapi DM, Todd J, Changalucha J, McDermid JM. Cryptosporidium prevalence and risk factors among mothers and infants 0 to 6 months in rural and semi-rural Northwest Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adamu H, Petros B, Zhang G, Kassa H, Amer S, Ye J, Feng Y, Xiao L. Distribution and clinical manifestations of Cryptosporidium species and subtypes in HIV/AIDS patients in Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lacombe K, Rockstroh J. HIV and viral hepatitis coinfections: advances and challenges. Gut. 2012;61:i47–i58. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sulkowski MS. Viral hepatitis and HIV coinfection. J Hepatol. 2008;48:353–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matthews PC, Geretti AM, Goulder PJR, Klenerman P. Epidemiology and impact of HIV coinfection with hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses in sub-Saharan Africa. J Clin Virol. 2014;61:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potthoff A, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. Treatment of HBV/HCV coinfection. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:919–928. doi: 10.1517/14656561003637659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.