Abstract

Pham, Luu V., Christopher Meinzen, Rafael S. Arias, Noah G. Schwartz, Adi Rattner, Catherine H. Miele, Philip L. Smith, Hartmut Schneider, J. Jaime Miranda, Robert H. Gilman, Vsevolod Y. Polotsky, William Checkley, and Alan R. Schwartz. Cross-sectional comparison of sleep-disordered breathing in native Peruvian highlanders and lowlanders. High Alt Med Biol. 18:11–19, 2017.

Background: Altitude can accentuate sleep disordered breathing (SDB), which has been linked to cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. SDB in highlanders has not been characterized in large controlled studies. The purpose of this study was to compare SDB prevalence and severity in highlanders and lowlanders.

Methods: 170 age-, body-mass-index- (BMI), and sex-matched pairs (age 58.2 ± 12.4 years, BMI 27.2 ± 3.5 kg/m2, and 86 men and 84 women) of the CRONICAS Cohort Study were recruited at a sea-level (Lima) and a high-altitude (Puno, 3825 m) setting in Peru. Participants underwent simultaneous nocturnal polygraphy and actigraphy to characterize breathing patterns, movement arousals, and sleep/wake state. We compared SDB prevalence, type, and severity between highlanders and lowlanders as measured by apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and pulse oximetry (SPO2) during sleep.

Results: Sleep apnea prevalence was greater in highlanders than in lowlanders (77% vs. 54%, p < 0.001). Compared with lowlanders, highlanders had twofold elevations in AHI due to increases in central rather than obstructive apneas. In highlanders compared with lowlanders, SPO2 was lower during wakefulness and decreased further during sleep (p < 0.001). Hypoxemia during wakefulness predicted sleep apnea in highlanders, and it appears to mediate the effects of altitude on sleep apnea prevalence. Surprisingly, hypoxemia was also quite prevalent in lowlanders, and it was also associated with increased odds of sleep apnea.

Conclusions: High altitude and hypoxemia at both high and low altitude were associated with increased SDB prevalence and severity. Our findings suggest that a large proportion of highlanders remain at risk for SDB sequelae.

Keywords: : altitude, Andean, apnea, epidemiology, hypoxia

Introduction

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is a major source of morbidity and mortality in low-altitude populations; it significantly contributes to morbidity, including glucose homeostasis disturbances, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and heart failure (Peppard et al., 2000; Punjabi et al., 2004; Gottlieb et al., 2010). SDB can also cause neurocognitive impairment and excessive daytime somnolence (Yaffe et al., 2011). All-cause mortality and especially cardiovascular deaths are increased in patients with severe disease sleep apnea (Marin et al., 2005). Moreover, the treatment of SDB is associated with reductions in incident cardiovascular events, metabolic dysfunction, and hypertension (Campos-Rodriguez et al., 2014; Gottlieb et al., 2014; Pamidi et al., 2015). Thus, SDB represents a modifiable risk factor for chronic diseases.

An estimated 140 million people are found to be living at a high altitude (Moore et al., 1998), where ambient hypoxia is a well-known trigger for SDB. Specifically, ambient hypoxia and hypoxemia destabilize respiratory patterns and play a major role in the pathogenesis of periodic breathing. In several small case series, investigators have documented a high prevalence of central and obstructive sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoxemia in highlanders (Kryger et al., 1978; Lahiri et al., 1983b; Coote et al., 1992; Normand et al., 1992; Sun et al., 1996; Arai et al., 2002; Pływaczewski et al., 2003; Spicuzza et al., 2004; Julian et al., 2013). Large uncontrolled surveys in clinical patients have also reported high rates of periodic apneic events (Bazurto et al., 2014). In contrast, a convenience sample nested within an epidemiological cohort did not confirm these prior findings (Bouscoulet et al., 2008). Thus, the prevalence, type, and severity of SDB in highland populations have not been considered.

The purpose of the present study was to systematically compare SDB in highlanders with that in age-, sex-, and body-mass-index (BMI)-matched lowlanders. We hypothesized that living at an altitude was associated with elevations in SDB prevalence and severity, which were mediated by altitude-related reductions in oxyhemoglobin saturation. We further hypothesized that hypoxemia within populations further predicted increases in sleep apnea prevalence. To address these hypotheses, we recruited pair-matched high- and low-altitude participants in an ongoing epidemiological cohort, and we systematically compared SDB patterns in highlanders and lowlanders.

Materials and Methods

Study setting and design

The current investigation is an ancillary study of the CRONICAS Cohort Study, a prospective cohort study designed to characterize the prevalence of cardiometabolic and pulmonary risk factors and patterns of disease progression in distinct Peruvian geographical settings (Miranda et al., 2012). Briefly, the umbrella CRONICAS Cohort study is an age-, sex-, and site-stratified population-based cohort conducted in four Peruvian settings differing by degree of urbanization, level of ambient and household air quality, and altitude. The present study was conducted in a subsample of participants in two study sites. The high-altitude site of the cohort was based in the urban and rural settings of Puno, located at 3825 m above sea level. The sea-level site was located in Pampas de San Juan de Miraflores, a peri-urban community of Lima. As part of the parent study, demographic data, anthropometrics, and pulmonary function by spirometry were assessed.

A convenience sample of 205 highlanders were recruited from Puno, from whom 170 were matched to lowlanders for sex, BMI within 2 kg/m2, and age within 5-year strata. Subjects were matched based on concurrent measures of BMI or BMI was imputed by carrying the last measure forward and adjusting for the cohort's mean rate of change in BMI (0.18 kg/m2/year, n = 25). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, USA (00002716), and Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia and A.B. PRISMA in Lima, Peru (reference number not applicable). The majority of highland subjects spoke Spanish and/or either Amayra or Quechua. All sea-level subjects spoke Spanish. Because of low literacy rates, field personnel, who spoke Spanish and either Amayra or Quechua at the high-altitude site and spoke Spanish at the sea-level site, explained the study to each participant before obtaining verbal informed assent.

Nocturnal recording and scoring methods

Participants underwent unattended nocturnal recordings of activity (Actiwatch 16 or 64; Philips Respironics, Amsterdam, NL), nasal airflow, thoracic excursion, and pulse oximetry (SPO2) (ApneaLink Plus; ResMed, Ltd., San Diego, USA). These devices were synchronized to a single computer the morning before a recording. Participants were instructed to wear and activate the devices at bedtime and to remove their devices after final awakening. A minimum of 4 hours of recording time was required to be included in the study. If recording data were insufficient, studies were repeated when possible, or otherwise excluded.

Recordings were scored and reviewed at the Johns Hopkins Sleep Disorders Center. Actigraphy provided an indicator of sleep-wake state and movement arousals. Sleep-wake state was estimated in 30-second epochs from actigraphy with a validated algorithm based on a weighted sum of actigraphy counts across successive epochs (Kushida et al., 2001).

Definitions

Arousals were defined by movements or swallow artifacts. Movements were indicated by abrupt increases in actigraphy count or blocking artifacts in the effort channel. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was defined as the number per hour of sleep of apneas and hypopneas, which were scored and classified in accordance with 2007 AASM recommended guidelines (Berry et al., 2012). Apneas were defined as the absence of flow for ≥10 seconds and were further classified as obstructive, central, or mixed in accordance with standard criteria. Hypopneas were defined as a reduction in nasal pressure by 30% and either a 4% desaturation or movement arousal. Hypopneas were also classified into obstructive, mixed, and central types based on evidence of flow limitation, as previously described (Palombini et al., 2013). Wake SPO2 and sleep SPO2 were defined as the mean SPO2 during wakeful and sleep epochs, respectively. In addition, we defined baseline SPO2 as the mean SPO2 at the beginning of all SDB events, and mean low SPO2 as the mean of SPO2 nadirs after all SDB events.

Biostatistical methods

To test the hypothesis that altitude is associated with increases in SDB, McNemar's tests were used to compare sleep apnea prevalence in highlanders with lowlanders. Differences in AHI and SPO2 in highlanders compared with lowlanders were examined with the Wilcoxon-signed-rank and paired t-tests, respectively. A mixed-effects linear regression model was used to examine sleep and altitude as predictors of nocturnal oxygenation.

To determine whether hypoxemia during wakefulness could account for the increased prevalence of sleep apnea in highlanders, Chi-squared analysis was used to compare prevalence of moderate-to-severe sleep apnea (AHI ≥15) across tertiles of wake SPO2 in highland and lowland samples. Logistic regression analysis was then used to examine the independent effects of wake SPo2 on odds for moderate-severe sleep apnea while adjusting for age, sex, and BMI to establish daytime hypoxemia as a potential mediator. The methods described by Imai et al. (2010) were then deployed to distinguish the direct effects of altitude from the indirect effects of altitude that might be mediated by hypoxemia. In this analysis, hypoxemia was calculated as differences in SPO2 from the mean of the overall sample and rescaled by dividing by a factor of 10, which approximates the mean difference in awake SPO2 between highlanders and lowlanders.

Analyses were performed by using R (www.r-project.org, with the linear mixed-effects models using “eigen” and s4, and mediation packages).

Results

Participant characteristics

One hundred seventy high-/low-altitude sex-, age-, and BMI-matched pairs underwent nocturnal polygraphy (Table 1). Participants were evenly split between men and women. On average, participants were middle aged and modestly overweight. Highlanders and lowlanders were similar in other SDB risk factors, including waist circumference, hip circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and body fat percentage (measured by bioelectrical impedance). Pulmonary function assessed by spirometry was similar in the two populations, although we observed a trend toward somewhat reduced forced vital capacity (FVC) in lowlanders compared with highlanders (p = 0.06). As expected, wake SPO2 was significantly lower in highlanders compared with lowlanders. Study participants had similar demographic and anthropometric characteristics to the parent population-based cohort located at a high altitude (Supplementary Data S1 and Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ham).

Table 1.

Study Participant Characteristics by Population Altitude

| Highlanders | Lowlanders | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 58.2 ± 12.4 | 57.8 ± 12.0 | 0.18 |

| Sex (F:M) | 84:86 | 84:86 | 1 |

| Anthropometrics, mean ± SD | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.2 ± 3.5 | 27.2 ± 3.5 | 0.68 |

| Waist (cm) | 91.1 ± 10.4 | 90.4 ± 9.1 | 0.20 |

| Hip (cm) | 95.3 ± 7.1 | 96.4 ± 7.3 | 0.02 |

| Waist:hip | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.63 |

| Body fat (%) | 30.2 ± 8.0 | 30.2 ± 7.5 | 0.89 |

| Pulmonary function, mean ± SD | |||

| FVC (L) | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 0.06 |

| FEV1 (L) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 0.42 |

| FEV1:FVC | 75.5 ± 7.2 | 76.8 ± 6.9 | 0.07 |

| % Predicted FVC | 107.8 ± 15.2 | 104.7 ± 17.0 | 0.12 |

| % Predicted FEV1 | 105.1 ± 16.7 | 103.6 ± 18.8 | 0.55 |

| Wake SpO2 (%) | 84.4 ± 2.2 | 94.3 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary disease prevalence, % | |||

| Chronic obstructive lung diseasea | 6.8 | 5.4 | 0.76 |

| Asthmab | 1.8 | 9.4 | 0.005 |

COPD was defined by a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC less than the lower limit of normal for a given age, sex, and height by using the Global Lung Function Initiative mixed ethnic population reference equation.

Asthma was defined by a physician diagnosis, self-report of wheezing attack, or use of asthma medications.

BMI, body-mass-index; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Sleep and respiratory patterns

We summarized sleep architecture in highlanders and lowlanders in Table 2. The mean recording time and total sleep time (TST) were greater in highlanders compared with lowlanders (p < 0.001). Sleep efficiency was reduced; wake after sleep onset and arousal index were elevated in highlanders compared with lowlanders (p = 0.01, p < 0.001, and p = 0.03, respectively), which suggest greater disturbances in sleep in highlanders compared with lowlanders.

Table 2.

Summary of Polygraphic Results by Population

| Highlanders | Lowlanders | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep characteristics | |||

| Total recording time (minutes) | 443.0 ± 79.5 | 396.6 ± 76.5 | <0.001 |

| TST (minutes) | 408.8 ± 76.1 | 370.8 ± 71.5 | <0.001 |

| Sleep efficiency (%) | 93.4 ± 4.3 | 94.6 ± 3.8 | 0.03 |

| Wake after sleep onset (minutes) | 26.8 ± 22.1 | 18.4 ± 17.7 | <0.001 |

| Arousal Index (events/h) | 6.3 (4.0–8.1) | 5.6 (3.5–7.1) | 0.03 |

| Respiratory analysis | |||

| Apnea Hypopnea Index (events/h) | 11.7 (5.9–25.1) | 6.1 (2.2–12.6) | <0.001 |

| Obstructive Event Index (events/h) | 4.6 (1.6–11.5) | 4.3 (1.4–10.7) | 0.61 |

| Central Event Index (events/h) | 4.4 (2.1–9.1) | 0.6 (0.2–1.7) | <0.001 |

| Mixed Event Index (events/h) | 0.0 (0.0–0.3) | 0.0 (0.0–0.2) | 0.01 |

| Oxygen Desaturation Indexa (events/h) | 10.8 (5.4–23.1) | 4.9 (1.8–12.0) | <0.001 |

| Mean event duration (seconds) | 21.3 (17.9–25.3) | 34.0 (27.9–39.4) | <0.001 |

| Oxygenation analysis | |||

| Mean sleep SPO2 (%) | 83.0 ± 2.4 | 93.3 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Mean nocturnal desaturation (%) | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Mean baseline SPO2 (%) | 84.3 ± 2.5 | 94.7 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Mean low SPO2 (%) | 79.5 ± 3.1 | 89.8 ± 2.0 | <0.001 |

| % TST with SPO2 ≤90 | 99.4 (96.4–99.9) | 2.4 (0.6–9.4) | <0.001 |

| % TST with SPO2 ≤80 | 4.6 (0.8–27.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | <0.001 |

Mean ± standard deviation and median (interquartile range) have been presented for normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively.

Oxygen Desaturation Index was defined by the number of ≥4% desaturation per hour.

TST, total sleep time.

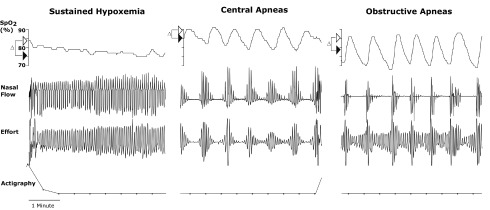

Three distinct SDB patterns were observed in highlanders, as illustrated in representative nocturnal polygraphic recordings in Figure 1. First, sustained hypoxemia was manifested by a decrease in SPO2 from wake to sleep and a stable respiratory pattern (left panel of Fig. 1). Second, intermittent hypoxemia resulted from central and obstructive sleep apneas (middle and right panels of Fig. 1, respectively). As shown, central sleep apneic events were characterized by decreases in respiratory effort with corresponding reductions in flow, whereas obstructive sleep apneas were characterized by progressive increases in effort.

FIG. 1.

Three distinct SDB patterns in highlanders. SPO2, nasal flow, respiratory effort, and actigraphy recordings are illustrated in three participants. Δ indicates differences in SPO2 between wakefulness (open arrowhead) and sleep (filled arrowhead). Sustained hypoxemia was manifested by a fall in SPO2 from wakefulness to sleep and a stable respiratory pattern (left panel). Intermittent hypoxemia resulted from periodic central apnea and obstructive sleep apnea (middle and right panel, respectively), which were characterized by period cessation in flow and either absence of effort (central apnea, middle panel) or progressively increasing effort (obstructive sleep apnea, right panel). SDB, sleep-disordered breathing.

SDB characteristics

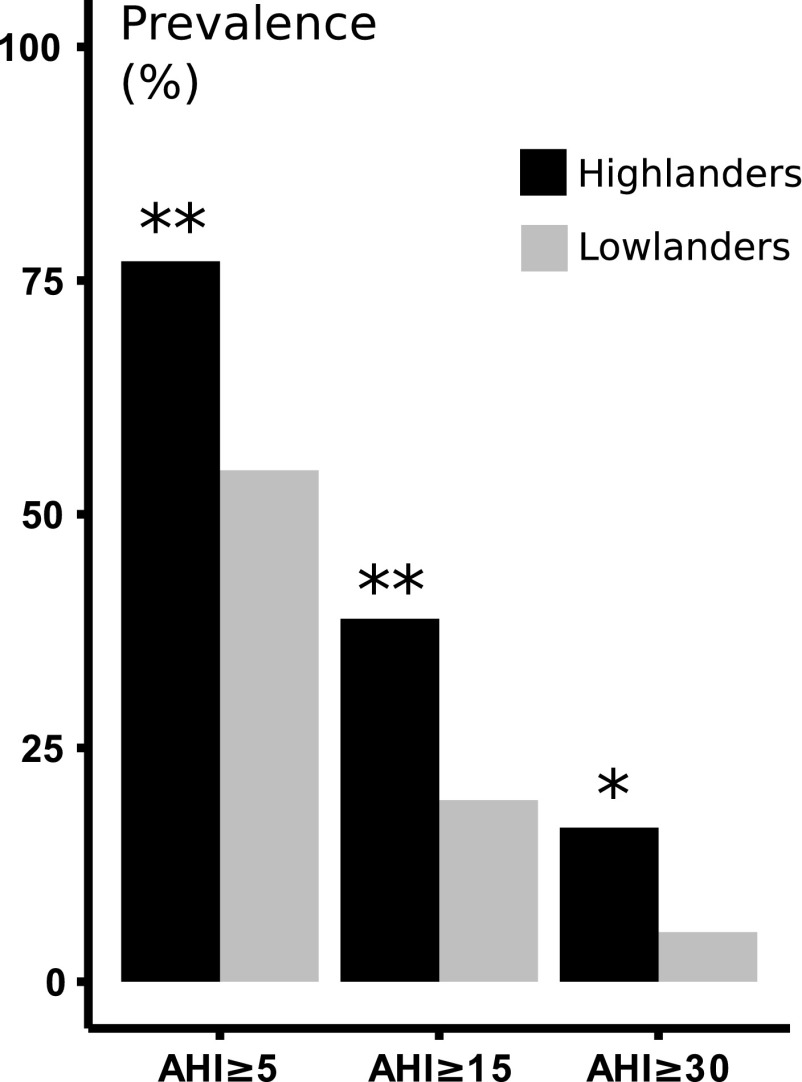

We present sleep apnea prevalence in Figure 2 at AHI thresholds of 5, 15, and 30 events/h. Sleep apnea prevalence was greater in highlanders compared with lowlanders (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p = 0.006, respectively). Of note, sleep apnea was present in the vast majority of highlanders, and a relatively large proportion of highlanders had severe sleep apnea (AHI ≥30). On average, we observed twofold elevations in AHI in highlanders compared with lowlanders (Table 2, p < 0.001). This elevation was largely explained by an increased frequency of central rather than obstructive apneic episodes. These results were not significantly affected by the imputation of BMI (see Supplementary Data S2 and Supplementary Table S2).

FIG. 2.

Unadjusted sleep apnea prevalence. Prevalence of sleep apnea in highlanders versus lowlanders at AHI thresholds of 5, 15, and 30 events/h. * and ** denote p = 0.006 and p < 0.001, respectively. At each cut-off, the prevalence of sleep apnea was significantly greater in highlanders compared with lowlanders. AHI, apnea-hypopnea index.

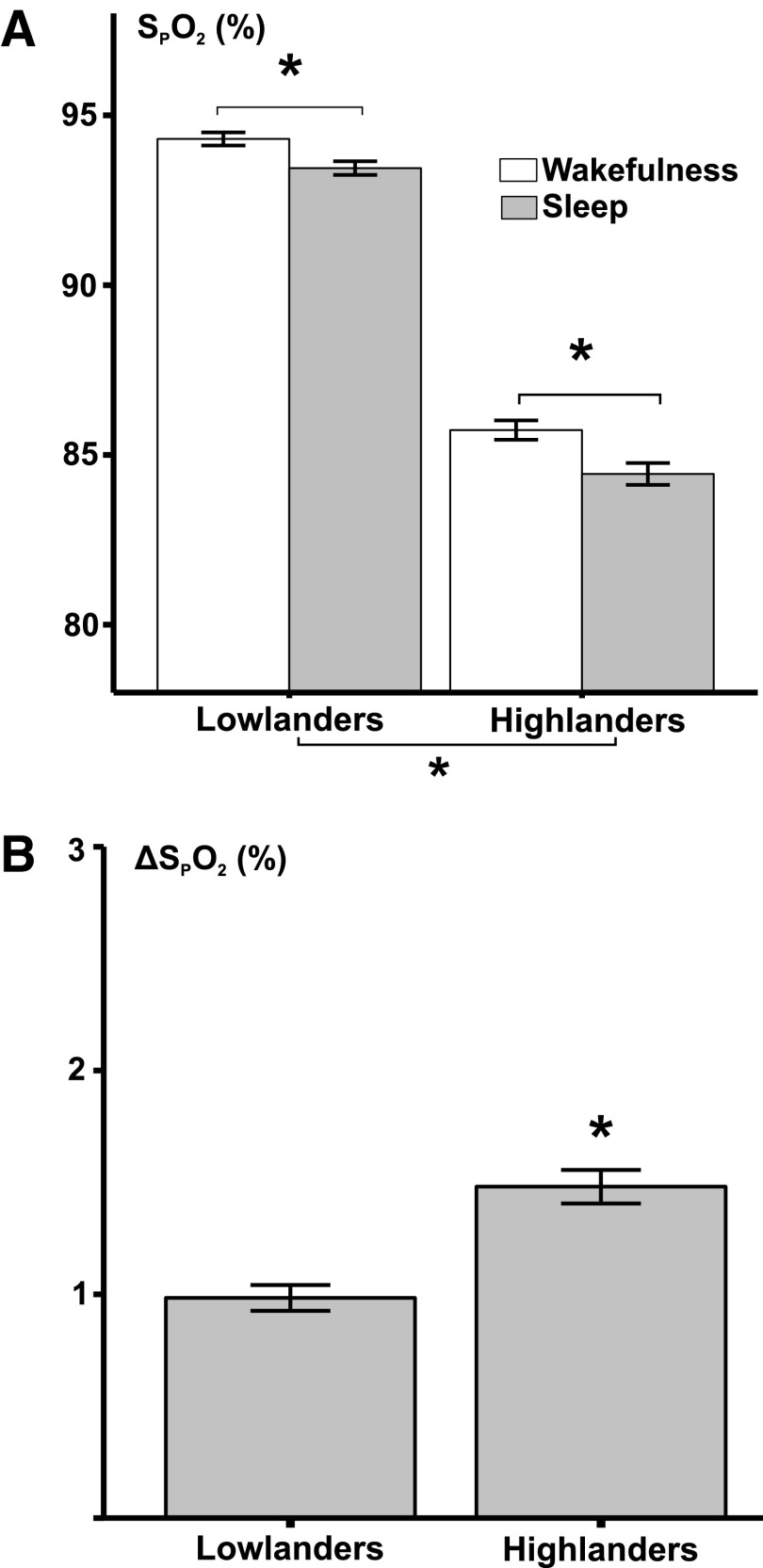

Oxygenation during sleep and wake in highlanders and lowlanders is represented in Figure 3. As expected, high altitude was independently associated with lower SPO2 during both wakefulness and sleep compared with sea level (p < 0.001). SPO2 decreased during sleep compared with wakefulness in both highlanders and lowlanders (p < 0.001). Sleep in highlanders was associated with an ∼1.5-fold greater fall in nocturnal saturation compared with lowlanders (p < 0.001). In fact, SPO2 fell 20% faster during apneic episodes in highlanders than lowlanders, even though apnea duration was shorter (Supplementary Data S3 and S4, Supplementary Table S4, and Supplementary Fig. S1).

FIG. 3.

Effects of altitude and sleep on hypoxemia exposures. (A) Average SPO2 ± standard error of the mean during wakefulness and sleep in highland and lowland populations were represented. (B) Decreases in mean SPO2 between wakefulness and sleep have been plotted. *p < 0.001. Altitude was associated with significant reductions in SPO2 during both wakefulness and sleep. Sleep was also associated with decreases in SPO2. Sleep in highlanders was associated with significantly greater decreases in SPO2 than sleep in lowlanders.

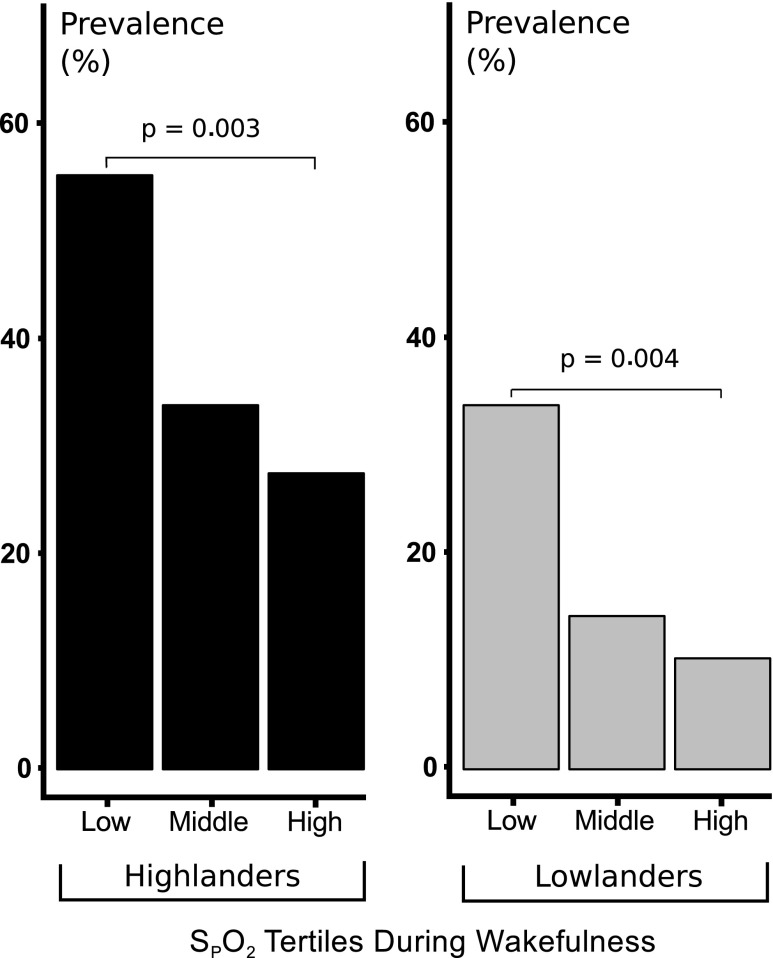

In Figure 4, sleep apnea prevalence is illustrated for tertiles of wake SPO2. Sleep apnea prevalence increased progressively with reductions in wake SPO2 in both highland and lowland cohorts (p = 0.003 and p = 0.004 in highlanders and lowlanders, respectively). These associations remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, and BMI (p = 0.02 and p = 0.048, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Associations between sleep apnea prevalence and hypoxemia: The prevalence of sleep apnea defined by AHI ≥15 is plotted as a function of tertiles of SPO2 during wakefulness in highlanders (left panel) and lowlanders (right panel). SPO2 ranges in low, middle, and high tertiles were 78.2 to <83.5, 83.5 to <85.5, and 85.5 to 89.8, respectively, in highlanders, and 89.6 to <93.7, 93.7 to <94.9, and 94.9 to 97.3, respectively, in lowlanders. Prevalence of sleep apnea fell progressively, with elevations in SPO2 during wakefulness. The prevalence of sleep apnea was significantly greater in low compared with high SPO2 tertile in both highlanders and lowlanders (p = 0.003 and 0.004, respectively).

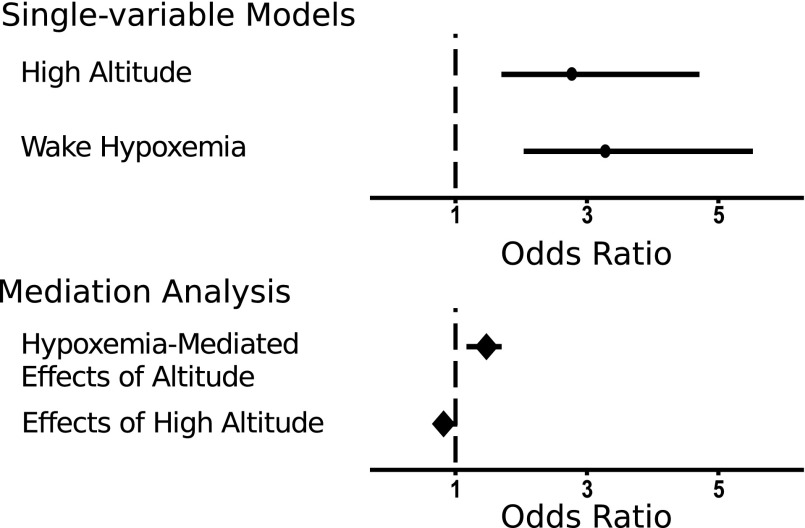

Single-variable logistic regression models demonstrated that living at a high altitude was associated with approximately a threefold increased odds for moderate-severe sleep apnea compared with the living at sea level (top panel of Fig. 5). A 10% reduction in SPO2 was also associated with a similar increase in odds for sleep apnea, suggesting that hypoxemia during wakefulness could mediate the effects of altitude on sleep apnea prevalence.

FIG. 5.

Sleep apnea odds. Estimated odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for having AHI ≥15 predicted by high altitude (referenced to low altitude) and hypoxemia (per 10% decrease in SPO2) in single-variable logistic regression models and mediation analysis. In bi-variable models, both altitude and hypoxemia were associated with similarly increased odds for sleep apnea (circles, top panel). Mediation analysis demonstrated that hypoxemia during wakefulness mediated the effects of altitude on the odds for having sleep apnea (odds ratio [OR] of 2.7 per 10% decrease in SPO2, bottom panel).

To further examine this possibility, mediation analysis demonstrated that hypoxemia was independently associated with sleep apnea while adjusting for altitude (odds ratio [OR] = 1.47, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.17–1.70, bottom panel of Fig. 5). Moreover, hypoxemia suppressed the direct effects of altitude on odds for sleep apnea, suggesting that hypoxemia mediates increases in sleep apnea susceptibility at a high altitude (OR = 0.81, CI = 0.70–1.02, bottom panel of Fig. 5).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated substantial increases in the prevalence and severity of SDB in highlanders compared with lowlanders in a large, rigorously matched sample. Elevations in AHI primarily resulted from a greater frequency of central apneic events in highlanders compared with lowlanders. As expected, living at a high altitude was associated with reductions in SPO2 during wakefulness and sleep, but decreases in SPO2 from wake to sleep were particularly pronounced at a high altitude. In addition, we found that reductions in SPO2 during wakefulness mediated increases in sleep apnea prevalence with altitude. Surprisingly, hypoxemia during wakefulness was also quite prevalent in our lowland population and predicted further increases in sleep apnea prevalence within both populations. We conclude that ambient hypoxia and hypoxemia place large segments of global populations at risk for SDB sequelae.

SDB has not been well characterized in large native highland cohorts; nor has SDB in highlanders been systematically compared with that in matched lowlanders. Nevertheless, prior studies describe substantial levels of periodic breathing and nocturnal hypoxemia in Asian and Andean highlanders (Lahiri et al., 1983a; Normand et al., 1992; Arai et al., 2002; Latshang et al., 2013). The effects of altitude cannot be clearly discerned, however, without suitable lowland control groups. Studies in native highlanders also suggest a high burden of SDB in those with chronic mountain sickness and pulmonary hypertension (Normand et al., 1992; Sun et al., 1996; Julian et al., 2013; Latshang et al., 2013). The PLATINO study characterized SDB in a somewhat larger community-based cohort and documented an ∼10% prevalence of moderate-to-severe sleep apnea in native highlanders at 2240 m elevation (Bouscoulet et al., 2008). In the present study, we found a considerably higher prevalence of sleep apnea, which can be attributed to greater degrees of hypoxemia at a higher altitude (3825 m) (Otero et al., 2016). In controlling for traditional risk factors for SDB with a pair-match design, we have isolated the effects of altitude on SDB in highlanders, and we have demonstrated that altitude is independently associated with a marked increase in the prevalence and severity of sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoxemia.

Several factors can account for increases in SDB prevalence and severity in highlanders. First, SPO2 in highlanders lay on the steep portion of the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve, leading to greater decreases in SPO2 during SDB events, which frequently exceed the 4% threshold required to score SDB episodes. In fact, we found that highlanders desaturated more rapidly than lowlanders during apneic events (Supplementary Fig. S3). Second, ambient hypoxia at altitude is known to destabilize ventilation and trigger periodic breathing during sleep. Concomitant decreases in resting PaCO2 are likely predisposed to periodic breathing at an altitude as PaCO2 approaches the apneic threshold at which central apneas and hypopneas occur (Beall et al., 1997; Xie et al., 2002). Third, ambient hypoxia increases ventilatory drive, which can account for reductions in event duration in highlanders compared with lowlanders. It can also further destabilize breathing during sleep and account for excess central rather than obstructive events in our highland versus lowland sample (Longobardo et al., 1982; Khoo et al., 1991; Wellman et al., 2008; Owens et al., 2010). Fourth, our analyses suggest that hypoxemia during wakefulness mediates these increases in sleep apnea prevalence between populations at different altitudes and accounts for variability in sleep apnea prevalence within populations at any altitude. Fifth, horizontal posture and decreases in ventilatory drive during sleep can lead to worsening V/Q mismatch, shunt, and hypoventilation. Because baseline SPO2 is on the steep portion of the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve in highlanders, these alterations appeared to exert greater influence on nocturnal oxygenation and can account for 1.5-fold greater desaturations during sleep in highlanders compared with lowlanders (Fig. 3). Taken together, our findings suggest that sleep amplifies disturbances in oxygenation and ventilatory stability at high altitude, substantially increasing the burden of intermittent and sustained nocturnal hypoxemia in highlanders.

An unexpected finding was the high prevalence of sleep apnea in lowlanders. Its prevalence was nearly twofold greater than that found in the Wisconsin Sleep and Hispanic Community Health/study of Latinos cohorts, which had similar demographic and anthropometric characteristics (Peppard et al., 2013; Redline et al., 2014). We also found that the severity of sleep apnea was somewhat greater in our cohort than the HypnoLaus study of Swiss lowlanders (Heinzer et al., 2015). These elevations in sleep apnea prevalence and severity may be due to racial and/or ethnic differences between our Peruvian and other Western cohorts (Kripke et al., 1997; Chen et al., 2015). Alternatively, daytime hypoxemia predicted sleep apnea in both Peruvian highland and lowland populations, suggesting that environmental exposures and/or concomitant cardiopulmonary dysfunction could also account for worsening of sleep apnea in our lowlanders. In fact, our lowlanders were more hypoxemic than expected, possibly due to the effects of urban air pollution and a high background prevalence of COPD and asthma in this district (Gaviola et al., 2016). Thus, the unusually high prevalence of hypoxemia in our lowland control population may have elevated the prevalence of SDB and attenuated the observed differences between our highland and lowland groups.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, instead of full polysomnography, we characterized SDB with limited respiratory polygraphy and estimated TST with actigraphy. Although we deployed an algorithm that has been validated in patients with obstructive sleep apnea for assessing sleep-wake state from actigraphy, this method is a rather insensitive indicator of EEG cortical arousal and may have overestimated TST (Kushida et al., 2001). As a result, this method may have underestimated the severity and prevalence of SDB in Peruvians. In contrast to the validated use of actigraphy in estimating TST in obstructive sleep apnea, its accuracy has not been examined in central sleep apnea patients, leading to some uncertainty in the estimation of sleep apnea severity in our highlanders. Nevertheless, systematic bias should be minimized by the uniform application of actigraphy across highlanders and lowlanders. Second, we acknowledge that we did not systematically survey the populations of interest, which may have introduced selection bias. Nevertheless, selection bias was minimized by the fact that study samples did not demonstrate substantial differences in demographics and anthropometry from the population-based highland cohort. Third, although we matched for recognized SDB risk factors, it is still possible that differences in unmeasured anthrometric characteristics (e.g., neck circumference), ethnicity, and environmental exposures exerted differential effects on SDB prevalence and severity in highland and lowland populations (Chen et al., 2015). Fourth, despite our relatively large sample size, we recognize that adaptations to a high altitude can differ substantially among highland populations worldwide (Beall, 2013). Thus, our findings in Andean highlanders may not be generalizable to other high-altitude natives (e.g., Tibetans and Ethiopians). Nevertheless, our study was specifically designed to examine the effects of altitude on SDB and provides a unique comparison of SDB patterns in highland and lowland populations. Finally, although our analysis suggests that hypoxemia mediates sleep apnea pathogenesis, causality cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional design of this study, which might also be influenced by residual confounding. Nevertheless, the hypothesis that hypoxemia plays a role in sleep apnea pathogenesis in highlanders is biologically plausible and consistent with results from a recent study that demonstrated an association between hypoxemia and sleep apnea severity (Rexhaj et al., 2015).

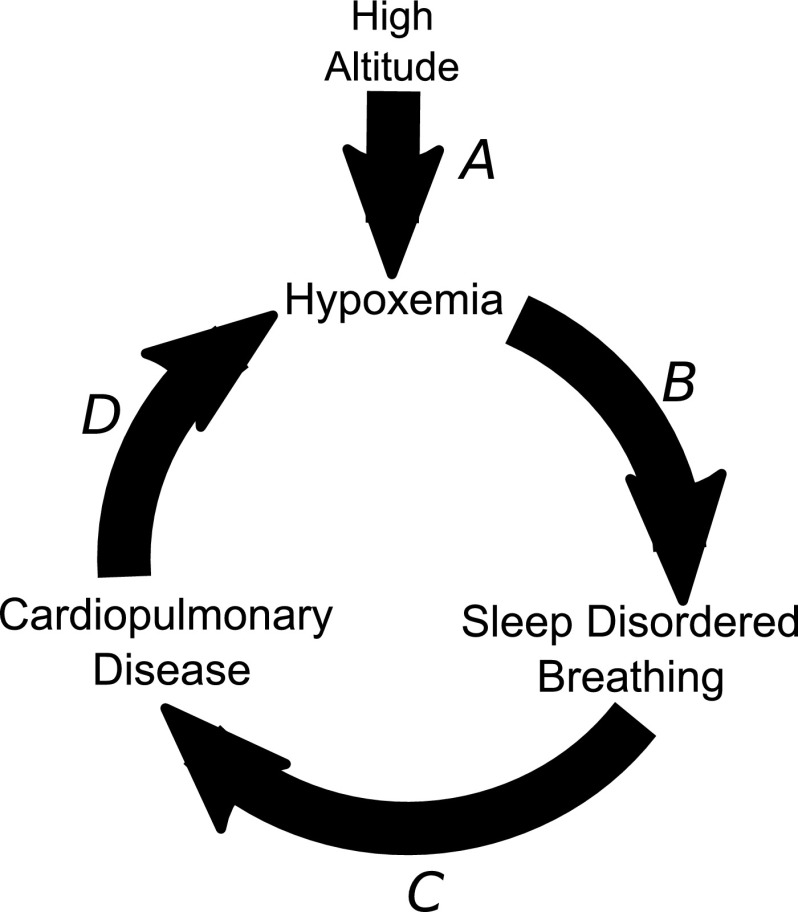

Conclusions

In summary, we found a high prevalence of SDB in Andean highlanders that was related to the severity of hypoxemia during wakefulness. Our findings suggest that hypoxic exposure at an altitude places highlanders at risk for the development of clinical sequelae of SDB, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and neurocognitive impairment (Punjabi et al., 2004; Marin et al., 2005; Yaffe et al., 2011). These findings lead us to speculate that altitude may telescope the development and progression of chronic disease in SDB (Fig. 6A). In addition, our findings indicate that SDB is accentuated in those who are already hypoxemia during the day (Fig. 6B), which could hasten the progression of underlying cardiopulmonary disease (Fig. 6C). Worsening cardiopulmonary disease, in turn, can cause further decreases in oxyhemoglobin saturation and exacerbate SDB (Fig. 6D). Thus, high altitude may set into motion a vicious cycle of hypoxemia, SDB, and chronic cardiopulmonary disease. High altitude may, therefore, provide a unique opportunity to study health effects of SDB on chronic disease. Further studies are necessary to determine the impact of SDB on chronic disease in highland populations.

FIG. 6.

A cycle of hypoxemia, sleep-disordered breathing, and cardiopulmonary disease. At a high altitude, ambient hypoxia causes hypoxemia (A), which predisposes to SDB (B). SDB can accelerate the progression cardiopulmonary disease (C), which can further decrease oxyhemoglobin saturation and exacerbate sleep-disordered breathing (D). High altitude may, therefore, foster a vicious cycle of worsening hypoxemia, sleep-disordered breathing, and chronic disease.

Sources of Funding

This project was funded with federal funds from the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN268200900033C. Luu Pham was further supported by an NIH National Research Service Award (5T32HL1109523). J. Jaime Miranda is supported by the Fogarty International Centre (R21TW009982), Grand Challenges Canada (0335-04), International Development Research Center Canada (106887-001), Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research (IAI CRN3036), Medical Research Council UK (M007405), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (U01HL114180), and National Institutes of Mental Health (U19MH098780). Vsevolod Y. Polotsky was supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grants (R01s HL133100, HL128970, HL080105) and by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences P50ES018176. Alan R. Schwartz was supported by NHLBI grants (HL128970 and HL133100). ResMed, LTD. provided ApneaLink recording devices. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of this article. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Francis Sgambati in the Johns Hopkins Center for Interdisciplinary Sleep Research and Education for his role in merging actigraphy and nocturnal respiratory recordings and in developing protocols for data transfer and management.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Arai Y, Tatsumi K, Sherpa NK, Masuyama S, Hasako K, Tanabe N, Takiguchi Y, and Kuriyama T. (2002). Impaired oxygenation during sleep at high altitude in Sherpa. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 133:131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazurto Zapata MA, Dueñas Meza E, Jaramillo C, Maldonado Gomez D, and Torres Duque C. (2014). Sleep apnea and oxygen saturation in adults at 2640 m above sea level. Sleep Sci 7:103–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall CM. (2013). Human adaptability studies at high altitude: Research designs and major concepts during fifty years of discovery. Am J Hum Biol 25:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall CM, Strohl KP, Blangero J, Williams-Blangero S, Almasy LA, Decker MJ, Worthman CM, Goldstein MC, Vargas E, Villena M, Soria R, Alarcon AM, and Gonzales C. (1997). Ventilation and hypoxic ventilatory response of Tibetan and Aymara high altitude natives. Am J Phys Anthropol 104:427–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, Gozal D, Iber C, Kapur VK, Marcus CL, Mehra R, Parthasarathy S, Quan SF, Redline S, Strohl KP, Ward SLD, and Tangredi MM. (2012). Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: Update of the 2007 AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. J Clin Sleep Med 8:597–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouscoulet LT, Vazquez-Garcia JC, Muino A, Marquez M, Lopez MV, de Oca MM, Talamo C, Valdivia G, Pertuze J, Menezes AM, and Perez-Padilla R. (2008). Prevalence of sleep related symptoms in four Latin American cities. J Clin Sleep Med 4:579–585 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Rodriguez F, Martinez-Garcia MA, Reyes-Nuñez N, Caballero-Martinez I, Catalan-Serra P, and Almeida-Gonzalez CV. (2014). Role of sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure therapy in the incidence of stroke or coronary heart disease in women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189:1544–1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, Lutsey PL, Javaheri S, Alcántara C, Jackson CL, Williams MA, and Redline S. (2015). Racial/ethnic differences in sleep disturbances: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Sleep 38:877–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coote JH, Stone BM, and Tsang G. (1992). Sleep of Andean high altitude natives. Eur J Appl Physiol 64:178–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaviola C, Miele CH, Wise RA, Gilman RH, Jaganath D, Miranda JJ, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Hansel NN, Checkley W, and CRONICAS Cohort Study Group. (2016). Urbanisation but not biomass fuel smoke exposure is associated with asthma prevalence in four resource-limited settings. Thorax 71:154–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Mehra R, Patel SR, Quan SF, Babineau DC, Tracy RP, Rueschman M, Blumenthal RS, Lewis EF, Bhatt DL, and Redline S. (2014). CPAP versus oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 370:2276–2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb DJ, Yenokyan G, Newman AB, O'Connor GT, Punjabi NM, Quan SF, Redline S, Resnick HE, Tong EK, Diener-West M, and Shahar E. (2010). A prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: The sleep heart health study. Circulation 122:352–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzer R, Vat S, Marques-Vidal P, Marti-Soler H, Andries D, Tobback N, Mooser V, Preisig M, Malhotra A, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Tafti M, and Haba-Rubio J. (2015). Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the general population: The HypnoLaus study. Lancet Respir Med 3:310–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Keele L, and Tingley D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods 15:309–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian CG, Vargas E, Gonzales M, Davila RD, Ladenburger A, Reardon L, Schoo C, Powers RW, Lee-Chiong T, and Moore LG. (2013). Sleep-disordered breathing and oxidative stress in preclinical chronic mountain sickness (excessive erythrocytosis). Respir Physiol Neurobiol 186:188–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo MC, Gottschalk A, and Pack AI. (1991). Sleep-induced periodic breathing and apnea: A theoretical study. J Appl Physiol 70:2014–2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke DF, Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Wingard DL, Mason WJ, and Mullaney DJ. (1997). Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in ages 40–64 years: A population-based survey. Sleep 20:65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryger M, Glas R, Jackson D, McCullough RE, Scoggin C, Grover RF, and Weil JV. (1978). Impaired oxygenation during sleep in excessive polycythemia of high altitude: Improvement with respiratory stimulation. Sleep 1:3–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O, and Dement WC. (2001). Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients. Sleep Med 2:389–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri S, Maret K, and Sherpa MG. (1983a). Dependence of high altitude sleep apnea on ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia. Respir Physiol 52:281–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri S, Maret K, and Sherpa MG. (1983b). Dependence of high altitude sleep apnea on ventilatory sensitivty to hypoxia. Respir Physiol 52:281–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latshang TD, Furian M, Aeschbacher S, Ulrich S, Myrzaakmatova AK, Osmonov B, Mirrakhimov EM, Sooronbaev T, Aldashev A, and Bloch KE. (2013). Association among sleep apnea and pulmonary hypertension in highlanders. Eur Respir J 42(Suppl 57):P2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longobardo GS, Gothe B, Goldman MD, and Cherniack NS. (1982). Sleep apnea considered as a control system instability. Respir Physiol 50:311–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, and Agusti AG. (2005). Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: An observational study. Lancet 365:1046–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda JJ, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Smeeth L, Gilman RH, and Checkley W. (2012). Addressing geographical variation in the progression of non-communicable diseases in Peru: The CRONICAS cohort study protocol. BMJ Open 2:e000610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LG, Niermeyer S, and Zamudio S. (1998). Human adaptation to high altitude: Regional and life-cycle perspectives. Am J Phys Anthropol Suppl 27:25–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normand H, Vargas E, Bordachar J, Benoit O, and Raynaud J. (1992). Sleep apneas in high altitude residents (3,800 m). Int J Sports Med 13 Suppl 1:S40–S42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero L, Hidalgo P, González R, and Morillo CA. (2016). Association of cardiovascular disease and sleep apnea at different altitudes. High Alt Med Biol 17:336–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens RL, Malhotra A, Eckert DJ, White DP, and Jordan AS. (2010). The influence of end-expiratory lung volume on measurements of pharyngeal collapsibility. J Appl Physiol 108:445–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palombini LO, Tufik S, Rapoport DM, Ayappa IA, Guilleminault C, de Godoy LBM, Castro LS, and Bittencourt L. (2013). Inspiratory flow limitation in a normal population of adults in São Paulo, Brazil. Sleep 36:1663–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamidi S, Wroblewski K, Stepien M, Sharif-Sidi K, Kilkus J, Whitmore H, and Tasali E. (2015). Eight hours of nightly continuous positive airway pressure treatment of obstructive sleep apnea improves glucose metabolism in patients with prediabetes. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 192:96–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, and Hla KM. (2013). Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 177:1006–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, and Skatrud J. (2000). Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med 342:1378–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pływaczewski R, Wu T-Y, Wang X-Q, Cheng H-W, Śliwiński P, and Zieliński J. (2003). Sleep structure and periodic breathing in Tibetans and Han at simulated altitude of 5000 m. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 136:187–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, Gottlieb DJ, Givelber R, and Resnick HE. (2004). Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: The sleep heart health study. Am J Epidemiol 160:521–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redline S, Sotres-Alvarez D, Loredo J, Hall M, Patel SR, Ramos A, Shah N, Ries A, Arens R, Barnhart J, Youngblood M, Zee P, and Daviglus ML. (2014). Sleep-disordered breathing in Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189:335–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexhaj E, Rimoldi SF, Pratali L, Brenner R, Andries D, Soria R, Salinas Salmón C, Villena M, Romero C, Allemann Y, Lovis A, Heinzer R, Sartori C, and Scherrer U. (2015). Sleep disordered breathing and vascular function in patients with chronic mountain sickness and healthy high-altitude dwellers. Chest 149:991–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicuzza L, Casiraghi N, Gamboa A, Keyl C, Schneider A, Mori A, Leon-Velarde F, Di Maria GU, and Bernardi L. (2004). Sleep-related hypoxaemia and excessive erythrocytosis in Andean high-altitude natives. Eur Respir J 23:41 46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Oliver-Pickett C, Ping Y, Micco AJ, Droma T, Zamudio S, Zhuang J, Huang SY, McCullough RG, Cymerman A, and Moore LG. (1996). Breathing and brain blood flow during sleep in patients with chronic mountain sickness. J Appl Physiol 81:611–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman A, Malhotra A, Jordan AS, Stevenson KE, Gautam S, and White DP. (2008). Effect of oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea: Role of loop gain. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 162:144–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie A, Skatrud JB, Puleo DS, Rahko PS, and Dempsey JA. (2002). Apnea–hypopnea threshold for CO2 in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165:1245–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, Redline S, Spira AP, Ensrud KE, ncoli-Israel S, and Stone KL. (2011). Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA 306:613–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.