Highlights

-

•

First study comparing climate impacts of tillage systems in organic arable farming.

-

•

No tillage system impact on N2O and CH4 emissions in grass-clover and wheat.

-

•

Higher N2O pulses after tillage operations with increasing soil organic carbon.

-

•

Higher soil organic carbon stocks with reduced tillage in slurry fertilised fields.

Keywords: Organic farming, Reduced tillage, Nitrous oxide, Soil organic carbon stocks, Grass-clover, Wheat

Abstract

Organic reduced tillage aims to combine the environmental benefits of organic farming and conservation tillage to increase sustainability and soil quality. In temperate climates, there is currently no knowledge about its impact on greenhouse gas emissions and only little information about soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks in these management systems. We therefore monitored nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) fluxes besides SOC stocks for two years in a grass-clover ley – winter wheat – cover crop sequence. The monitoring was undertaken in an organically managed long-term tillage trial on a clay rich soil in Switzerland. Reduced tillage (RT) was compared with ploughing (conventional tillage, CT) in interaction with two fertilisation systems, cattle slurry alone (SL) versus cattle manure compost and slurry (MC). Median N2O and CH4 flux rates were 13 μg N2O-N m−2 h−1 and −2 μg CH4C m−2 h−1, respectively, with no treatment effects. N2O fluxes correlated positively with nitrate contents, soil temperature, water filled pore space and dissolved organic carbon and negatively with ammonium contents in soil. Pulse emissions after tillage operations and slurry application dominated cumulative gas emissions. N2O emissions after tillage operations correlated with SOC contents and collinearly to microbial biomass. There was no tillage system impact on cumulative N2O emissions in the grass-clover (0.8–0.9 kg N2O-N ha−1, 369 days) and winter wheat (2.1–3.0 kg N2O-N ha−1, 296 days) cropping seasons, with a tendency towards higher emissions in MC than SL in winter wheat. Including a tillage induced peak after wheat harvest, a full two year data set showed increased cumulative N2O emissions in RT than CT and in MC than SL. There was no clear treatment influence on cumulative CH4 uptake. Topsoil SOC accumulation (0–0.1 m) was still ongoing. SOC stocks were more stratified in RT than CT and in MC than SL. Total SOC stocks (0–0.5 m) were higher in RT than CT in SL and similar in MC. Maximum relative SOC stock difference accounted for +8.1 Mg C ha−1 in RT-MC compared to CT-SL after 13 years which dominated over the relative increase in greenhouse gas emissions. Under these site conditions, organic reduced tillage and manure compost application seems to be a viable greenhouse gas mitigation strategy as long as SOC is sequestered.

1. Introduction

Conservation tillage has proven to be advantageous in terms of soil erosion control and water conservation and e.g. no-till farming (NT) is widely adopted, particularly in dryer regions (Derpsch et al., 2010). However, no-till can reduce yields and seems profitable only in combination with other measures of conservation agriculture like improved crop rotations and residue management (Pittelkow et al., 2015). With the aim of profiting from the benefits and omitting the risks of intensive herbicide application in conventional NT systems, reduced tillage systems (RT) are thus developing in the context of organic farming (Mäder and Berner, 2012, Peigné et al., 2015). Organic reduced tillage systems include “tillage systems that operate at shallower depths or at lower intensity compared to customary ploughing in a given region” (Mäder and Berner, 2012; p. 8), in combination with adjustments of crop rotations, mechanical weeding and green manure management within an organic farming system. Current knowledge indicates that soil organic matter increases with conversion to organic reduced tillage (Emmerling, 2007, Gadermaier et al., 2012). Yet, yield reductions of about 7%, as well as more difficult nutrient management and weed control in comparison with ploughing (CT) are the main challenges which have been the focus of recent research (Casagrande et al., 2015, Cooper et al., 2016). The climatic impact of organic reduced tillage systems is still poorly understood due to limited data availability, but there is much greater information regarding the effects of NT compared to CT in conventional farming systems. Those direct effects of farm management on climate change include changes in soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks and direct emissions of nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) from fertilised soils. In the conventional context, an accumulation of SOC by conversion of CT to NT was found to be mostly restricted to the topsoil whilst in lower horizons, a decrease in SOC stocks was detected. The overall SOC stock gain seems to be rather small (Angers and Eriksen-Hamel, 2008, Luo et al., 2010). With regard to N2O in temperate humid climates, data compilations show that N2O emissions increase in the initial years after conversion from CT to NT/RT, but decrease after more than ten years (Six et al., 2004) or may not differ overall (van Kessel et al., 2013). Additionally, Rochette (2008) addressed the factor of soil aeration status and found higher N2O emissions in NT than CT in poorly aerated soils, but not in well aerated soils. The influence of different tillage systems on CH4 uptake has not been thoroughly assessed, but some studies suggest an increased uptake with conversion to NT/RT management (Hütsch, 2001).

There are several organic reduced tillage trials, but SOC was only sampled in a few of them. Crittenden et al. (2015) did not find significant differences in SOC stocks (0–0.5 m) between ploughing and non-inversion tillage after three years. Schulz et al. (2014) only reported SOC stocks per soil layer, with higher SOC stocks in 0–0.3 m in the RT compared to CT treatment after 11 years, and lower SOC stocks at lower depth (0.3–0.9 m). Zikeli et al. (2013) found higher SOC concentrations in RT compared to CT in the topsoil (0–0.2 m) and no changes below (0.4-0.6 m) after 12 years. This restricted dataset reflects the difficulty in SOC data availability, whilst the variability between results does not allow for conclusions yet. For N2O and CH4 emissions, the only studies comparing CT and RT under organic farming conditions were conducted in vegetable production (Kong et al., 2009, Yagioka et al., 2015). They either reported higher N2O emissions in minimum tilled soils due to restricted aeration (Kong et al., 2009) or no tillage system effect (Yagioka et al., 2015). The low gas sampling frequency in both studies however restricts conclusions, and the comparability with organic arable farming in temperate Europe is also questionable.

As there is evidence that organic farming practices increase at least topsoil SOC stocks (Gattinger et al., 2012), and N2O emissions were found to be lower (Skinner et al., 2014) compared with conventional farming systems, it is difficult to transfer findings from conventional tillage studies to the organic farming context. The difference between organic and conventional farming is an increased complexity of soil C and N cycling through the use of diverse crop rotations with green manures and leys, biological nitrogen fixation by legumes, besides different types of organic, rather than mineral fertilisers (Watson et al., 2002). For example, solid organic manures have been demonstrated to maintain (Schulz et al., 2014) or increase SOC stocks (Koga and Tsuji, 2009, Viaud et al., 2011, Powlson et al., 2012, Maltas et al., 2013) through regular C-input compared to stockless or synthetically fertilised systems, and to lower N2O emissions compared with liquid manures or mineral fertilisers (Gregorich et al., 2005). Soil biochemical quality is also enhanced as microbial abundance increased and community composition changed with organic versus conventional farming (Mäder et al., 2002, Hartmann et al., 2015) and by conversion from ploughing to reduced tillage (Six et al., 2006, Gadermaier et al., 2012, Kuntz et al., 2013). Therefore conditions for microbial C and N turnover and thus N2O production and SOC dynamics are expected to differ between conventional no-till and organic reduced tillage systems.

The scope of this study was to monitor N2O and CH4 trace gas fluxes for two years and to assess SOC stocks in an organic long-term tillage trial. In interaction with tillage systems, two organic fertiliser types were included to assess the impact of different C and N availabilities. The cropping sequence included a grass-clover ley and winter wheat as typical crops in organic rotations found on European farms. We hypothesized that more than ten years of differentiated tillage and fertilisation management; i) do not impact total SOC stocks and cumulative N2O emissions but do increase CH4 uptake with reduced tillage in relation with ploughing, according to global meta-analyses on tillage system studies, and ii) decrease N2O emissions but increase CH4 uptake and total SOC stocks when comparing a manure compost/slurry system with slurry fertilisation only due to the higher C input and lower N availability. We further aimed at assessing drivers of N2O emissions in these site conditions and to estimate the overall potential to mitigate direct greenhouse gas emissions by such a management system change.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Site conditions and field trial setup

This study was conducted in a three factorial organic long-term trial with four treatment replicates, which was established in autumn 2002 in Frick (Switzerland, 47°30′N, 8°01′E, 350 m altitude). The trial is managed organically according to the European Union Regulation (EC) No 834/2007, and was designed to assess reduced and conventional tillage systems under organic farming conditions. Tillage is distinguished between conventional mouldboard ploughing (CT, 0.15–0.18 m) and reduced tillage (RT, 0.07–0.1 m). In the reduced tillage system, a skim plough (‘Stoppelhobel’, Zobel, D) and a chisel plough (‘WeCo-Dyn system’, Friedrich Wenz GmbH, D) were used and tillage timing occasionally differed from CT. Seedbed preparation was carried out on both treatments with a rotating harrow (0.05 m, Rau Landtechnik GmbH, D). Additionally, two organic fertilisation systems were compared with the same total N input within a crop rotation: cattle slurry (SL) versus cattle manure compost, in addition to reduced amounts of cattle slurry (MC). Manure compost was spread with a manure spreader (Gafner Maschinenbau AG, CH) and slurry applied superficially with a drag hose (Hochdorfer Technik AG, CH). The trial design was described in detail in Berner et al. (2008) and the management during 2013–2014 including fertiliser properties is presented in Table 1. The influence of biodynamic preparations, the third experimental factor, was not considered in this study. The six year crop rotation of the first two periods included maize (Zea mays L.), winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L. cv. ‘Wiwa’), an oat-clover-vetch intercrop (Avena sativa L., Trifolium incarnatum L., Vicia villosa R.), sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), spelt (Triticum spelta L.) and a 2-year grass-clover ley mixture. In 2014, the rotation was changed and winter wheat (2014) followed grass-clover (2013). Characterised as a Vertic Cambisol (WRB), the calcareous clay soil (45% clay, 27% silt, 28% sand) exhibits considerable swelling/shrinking properties (Fontana et al., 2015) and a mean pH (H2O) of 7.1. In 2012 to 2014, mean annual precipitations were 1303, 1112 and 966 mm with mean annual temperatures of 10.1, 9.7 and 11.1 °C respectively.

Table 1.

Farm operations in the Frick trial in 2013 and 2014.

| Date | Farm operation | Treatments | Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31th Aug 2011 | seedbed preparation and seeding of grass-clover | all | grass-clover mixture OH-330, 33 kg ha−1 |

| 2013 | |||

| 19th March | manure compost application | only MC | 55 kg Nt ha−1, 20.3% dm, C/N 11.3 |

| 23th May | 1st cut | all | |

| 4th June | 1st slurry application | all | MC: 25 kg Nt ha−1, SL: 50 kg Nt ha−1, 3.5% dm, C/N 10.2 |

| 4th July | 2nd cut | all | |

| 18th July | 2nd slurry application | all | MC: 22 kg Nt ha−1, SL: 44 kg Nt ha−1, 2.9% dm, C/N 9.1 |

| 27th Aug | 3rd cut | all | |

| 23th Sep | reduced ley termination | only RT | skim plough, 0.07–0.1 m |

| 2nd Oct | reduced ley termination | only RT | chisel plough, 0.1 m |

| 7th Oct | 4th cut | only CT | |

| 9th Oct | ley termination by ploughing | only CT | mouldboard plough, 0.15–0.18 m |

| 20th Oct | seedbed preparation and seeding of winter wheat | all | rotary tiller, 0.05 m winter wheat cv. ‘Wiwa’, 250 kg ha−1 |

| 2014 | |||

| 11th March | manure compost application | only MC | 62 kg Nt ha−1, 25.8% dm, C/N 11.7 |

| 19th March | 1st slurry application | all | MC: 27 kg Nt ha−1, SL: 55 kg Nt ha−1, 3.5% dm, C/N 9.5 |

| 9th Apr | 2nd slurry application | all | MC: 30 kg Nt ha−1, SL: 61 kg Nt ha−1, 4.6% dm, C/N 11.4 |

| 17th July | wheat harvest | all | |

| 25th Aug | seedbed preparation and seeding of a cover crop | all | rotary tiller, 0.05 m Orgamix DS mixture (Trifolium incarnatum L., Vicia villosa R., Secale cereale L.), 60 kg ha−1 |

CT – ploughing, RT – reduced tillage, SL – slurry, MC – manure compost, Nt – total nitrogen, dm – dry matter.

2.2. Greenhouse gas monitoring

Soil nitrous oxide (N2O) and methane (CH4) fluxes were measured using closed static chambers. Two base rings per plot (n = 8 per treatment, 0.3 m diameter) were permanently installed in the soil (0.1 m depth) and only removed for tillage operations. They were arranged within the 12 × 12 m plots in 2 m distance from plot margins. Two pseudoreplicates per plot were chosen to cover spatial heterogeneity. The corresponding use of 40 chambers in total allowed only for manual chamber measurements.

As plants were included in the base rings, all management operations except tillage and seedbed preparation were carried out manually according to the rest of the trial. Fertiliser amounts are given in Table 1. As the original trial design did not include an unfertilised control, we defined two additional plots with a size of 2 × 12 m per tillage treatment at the margins of the tillage strip. These unfertilised control plots were equipped with two base rings (n = 4 per tillage treatment) and were used to determine emission factors and to estimate the correlation between cumulative N2O emissions and N input but not to assess treatment effects statistically. Gas and corresponding soil samples were taken at least once a week between 9:00 and 12:00 o’clock. Sampling in this time slot was shown to cover the mean daily soil temperature and therefore helped to avoid biases in the calculation of cumulative N2O emissions caused by diurnal temperature driven changes of N2O fluxes (Alves et al., 2012). In addition, more frequent samplings took place just before and after fertiliser applications and tillage operations. Further additional samplings were conducted whenever possible if weather induced pulse emissions were expected. The vented PVC flux chambers used for our monitoring had an inner diameter of 0.3 m (0.12 m height) and have been described in detail by Flessa et al. (1995). To account for the increasing crop height within season, additional rings were placed between base rings and chambers prior to each sampling. Fans were installed in these additional rings to assure a sufficient gas distribution within the large chamber volume. Four gas samples were taken periodically within a deployment time of 30 min (chamber only) or 50 min (with additional rings). Chamber headspace temperature was recorded per chamber in the beginning and the end of sampling and soil temperature in 0.1 m depth once per sampling date. Gas samples were taken with a 20 ml plastic syringe (Luer-Lock, Becton Dickinson AG, CH) and injected into 12 ml gas-tight Exetainers (Labco Ltd, UK). Exetainers were evacuated in advance and controlled for tightness before sampling. Gas samples were analysed simultaneously for carbon dioxide (CO2), N2O and CH4 via gas chromatography (7890A, Agilent Technologies, CA) equipped with an electron capture detector (ECD) for N2O analysis and a flame ionisation detector (FID) for the quantification of CO2 and CH4 concentrations in the samples. This special greenhouse gas configuration is described in detail in Wang (2010) (Method 2). An autosampler (MPS 2XL, Gerstel AG, CH) facilitated sample injection. Peak areas were integrated by Open Lab Chemstation Software (Agilent Technologies, CA). For calibration, three standard gas mixtures ranging from ambient to ten times ambient were analysed with each sampling batch. Calibration and flux calculation was done in R (R Core Team, 2013). GC stability was regularly tested and only baseline signal coefficient of variances lower than 3% accepted. Flux calculation based on a mixed linear/non-linear approach under consideration of headspace temperatures. The adjusted algorithm based on the HMR package in R (Pedersen, 2012) and is described in Leiber-Sauheitl et al. (2013) in more detail. The script selects automatically the most suitable model for each flux being either a robust linear or a non-linear (HMR) model. Compared with the linear regression for flux calculation, cumulative N2O emissions were on average 20% higher in this study. As chambers included plants, CO2 fluxes represent the ecosystem respiration as a sum of plant and soil respiration. We therefore used CO2 flux data for interpretation solely after tillage operations when soil respiration was the only source for CO2 emissions.

Cumulative N2O and CH4 emissions [kg ha−1] were integrated per chamber with the trapezoid rule (linear interpolation between measured gas fluxes over the time interval in between). Calculated emissions per time interval were summed to be the total cumulative emission per defined time period (period dates see Table S1 in Supplement material). To detect treatment differences in regard to crop management, periods after tillage operations and slurry applications were visually defined. Fluxes were cumulated from the sampling after the operation until fluxes returned to 20 μg N2O-N m−2 h−1. All fluxes between these management induced N2O emission periods were defined as baseline fluxes.

To determine fertiliser derived emissions, N2O emission factors (EF) were calculated as

| EF1 = N2O-Ntreatment/Ntapplied × 100 | (1) |

| EF2 = (N2O-Ntreatment − N2O-Ncontrol)/Ntapplied × 100 | (2) |

with EF in % and all cumulative N2O emissions and total N-inputs in kg N ha−1. N2O-Ntreatment refers to cumulative N2O-N emissions from the different fertiliser treatments, Ntapplied to the total input by the organic manures and N2O-Ncontrol to the cumulative N2O-N emissions from the unfertilised control plots. N input by biological nitrogen fixation during the grass-clover period was assumed to be similar between treatments as botanical composition did not differ in 2012 and 2013 (data not shown).

2.3. Soil sampling

With each gas sampling, ancillary soil samples were taken with a soil auger (0.01 m diameter) to 0.2 m depth in each plot. The four field replicates were pooled to one batch per treatment. The soil was immediately processed. Gravimetric water content was analysed after drying at 105 °C for 24 h. Calculation of the water filled pore space (WFPS) posed a challenge in our study. The clayey soil contains about 45% of swellable clay minerals (mainly illite, vermiculite and smectite). It was thus impossible to determine bulk densities with the cylinder method during dry season when the soil matrix was hard and large cracks occurred. We therefore used soil physical parameters elaborated with a shrinkage analysis for both tillage treatments of the Frick trial by Fontana et al. (2015). Specific pore volumes and in turn bulk densities at each sampling date were modelled based on soil shrinkage characteristics, clay and soil organic carbon content per treatment in relation to the gravimetric water content per sampling date. This approach revealed more realistic WFPS values over time than using bulk densities that were measured twice per year during soil water saturation (data not shown). WFPS data should consequently be used only for the interpretation of N2O fluxes. The WFPS was calculated by

| WFPS = (WC * BD)/(1 − BD/PD) | (3) |

with WFPS [%], WC = gravimetric water content [%], BD = soil bulk density [Mg dry matter soil m−3] and PD = particle density of quartz [2.67 Mg m−3].

For the analysis of dissolved carbon and mineral nitrogen, a 20 g fresh soil aliquot was processed to 5 mm aggregates, suspended with 0.01 M CaCl2 solution (1:4, w/v) and horizontally shaken for 1 h at 175 rpm (SM-30, Edmund Bühler GmbH, D), passed through a cellulose filter (MN 619EH, Macherey–Nagel, D) and stored at −18 °C. Soil extracts were analysed for mineral nitrogen (nitrate and ammonium) spectrophotometrically (SAN-plus Segmented Flow Analyser, Skalar Analytical B.V., NL). Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was determined in the same soil extracts with a TOC analyser (DIMA-TOC 100, Dimatec Analysentechnik GmbH, D).

In March 2015, soil samples were taken plotwise with soil augers in the range of three depths (0–0.1, 0.1–0.2, 0.2–0.5 m) for the analysis of soil organic carbon (SOC) and microbial biomass. Soil organic carbon (SOC) concentration was assessed by wet oxidation of 1 g of dry soil in 20 ml concentrated H2SO4 and 25 ml 2 M K2Cr2O7 according to Agroscope (2012). To determine microbial biomass, 20 g of field moist soil was extracted with the chloroform fumigation extraction method (CFE) using 0.5 M K2SO4-solution (1:4, w/v) as described in detail by Fließbach et al. (2007). CFE-C and N were analysed with the TOC analyser and may not fully represent microbial biomass as visible but not all fresh roots were removed by soil preparation (Mueller et al., 1992). For a precise calculation of SOC stocks, soil bulk density was determined in three depths (0–0.1, 0.1–0.2, 0.2–0.5 m) using soil cylinders and special augers (Ø 0.05 m, Sample ring kit C, Eijkelkamp, NL) at the end of the greenhouse gas monitoring in November 2014. The soil was fully water saturated at that time. SOC stocks were calculated from SOC concentrations (2015, %) and measured bulk densities (2014) per soil layer by

| SOCstocks = SOCcontent × BD × h × 0.1 | (4) |

with SOC stocks in Mg ha−1, SOC contents in kg Mg−1, BD = soil bulk density [Mg dry matter soil m−3], h = layer thickness [m].

SOC stocks per layer were summed up to total SOC stocks in 0–0.5 m. To account for tillage induced bias as discussed by Ellert and Bettany (1995), we used the equivalent soil mass approach (ESM) suggested by Appel (2011). In brief, mean soil mass of all ploughed plots (0–0.5 m) was taken as reference soil mass. Thickness of subsoil layers (0.2–0.5 m) were adjusted accordingly and SOC stocks recalculated. ESM corrected SOC stocks were therefore based on the same soil mass. To display the long-term development of SOC concentrations, field data of the Frick trial from earlier years (2002–2008) published in Gadermaier et al. (2012) were complemented with data from 2012 and 2015. SOC concentrations were analysed identically (wet titration) at the same laboratory in all years with the use of internal standards.

2.4. Data processing and statistics

All data processing and statistics were accomplished in R (R Core Team, 2013). Arithmetic means of the two pseudo-replicated chambers per plot were taken for statistical analysis of gas data. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) of cumulative gas emissions (Table 2, Fig. 2) and soil properties (Table 3, Table S3 in Supplement material) were calculated with a generalised least square model with plots as spatial replicates (gls function of nlme package (Pinheiro et al., 2014)) to assess treatment effects. Clay gradient within the field trial explained spatial heterogeneity better than the trial design (strip-split plot) and was therefore included as a covariate. To assure model homoscedasticity, treatment or block variance was included as a variance covariate. For the multiple regression of time series gas and soil data (Table 4), N2O fluxes were pooled per treatment and log transformed. Due to occasional negative N2O fluxes (min. −2.9 μg N2O-N m−2 h−1), all N2O fluxes were transformed to positive values by adding a constant beforehand. This affected 23 out of 480 data points. Temporal dependence was considered in the correlation term and sampling dates included as variance covariate. The regression of N2O and CO2 fluxes after tillage operations (period see Table S1 in Supplement material) was treated likewise. Single linear regressions were accomplished to assess drivers of N2O emissions. For all analyses, model residuals were checked for normality and homoscedasticity graphically.

Table 2.

Yields, cumulative N2O-N and CH4-C emissions and N2O emission factors (EF) of two cropping seasons: grass-clover (18/09/2012–22/09/2013, 369 days) and winter wheat (22/09/2013–15/07/2014, 296 days). Means (SE, n = 8 for gas data, n = 4 for yield data) are given per treatment and ANCOVA results mark significant differences between tillage and fertiliser systems.

| Treatments | grass-clover ley |

winter wheat |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yield | N2O-N |

CH4-C | yield | N2O-N |

CH4-C | |||

| t ha−1 | kg ha−1 | EF% | kg ha−1 | t ha−1 | kg ha−1 | EF% | kg ha−1 | |

| CT x SL | 11.7 (0.4) | 0.82 (0.09) | 0.71a/0.09b | −0.14 (0.02) | 4.49 (0.12) | 2.07 (0.23) | 1.64a/0.24b | −0.24 (0.04) |

| CT x MC | 11.3 (0.7) | 0.82 (0.12) | 0.69/0.09 | −0.12 (0.08) | 4.32 (0.19) | 2.96 (0.56) | 1.91/0.77 | −0.25 (0.06) |

| RT x SL | 11.2 (0.2) | 0.75 (0.20) | 0.65/0.16 | 0.01 (0.10) | 4.62 (0.07) | 2.27 (0.24) | 1.81/0.29 | −0.08 (0.05) |

| RT x MC | 10.3 (0.3) | 0.89 (0.22) | 0.74/0.27 | −0.07 (0.03) | 4.23 (0.22) | 2.80 (0.24) | 1.80/0.57 | −0.39 (0.08) |

| ANCOVA (F-Statistics and significance levels) | ||||||||

| Clay content | 2.11 ns | 9.04 * | 15.07 ** | 47.63 *** | 2.14 ns | 5.68 * | ||

| Tillage | 9.08 * | 0.02 ns | 4.78 (*) | 2.72 ns | 0.82ns | 0.37 ns | ||

| Fertilisation | 7.12 * | 0.05 ns | 0.01 ns | 5.16 * | 3.91 (*) | 12.25 ** | ||

| Tillage x Fertilisation | 0.23 ns | 0.14 ns | 0.82 ns | 0.55 ns | 0.23 ns | 5.31 * | ||

Treatments: CT – ploughing, RT – reduced tillage, SL – slurry, MC – manure compost. ns = not significant.

(*)p < 0.1. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

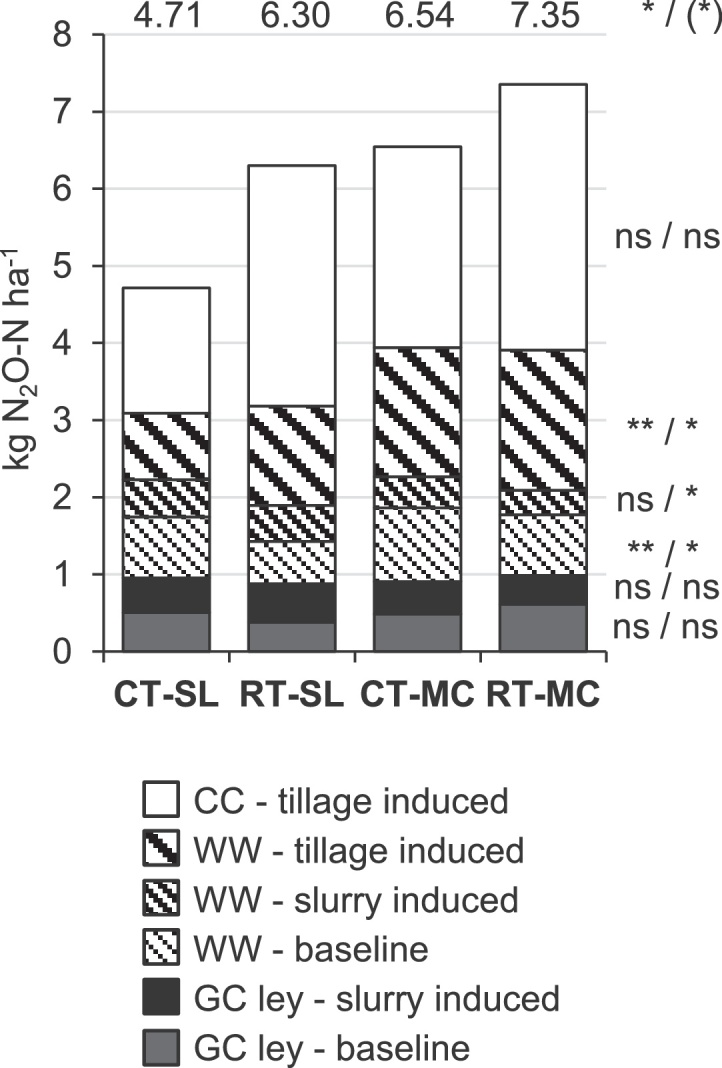

Fig. 2.

Management induced cumulative N2O emissions per cropping season (GC ley – grass-clover, WW – winter wheat, CC – cover crop) and total cumulative emissions of the two year monitoring period. Management induced emissions are assigned to emissions after slurry application and tillage operations (periods see Table S1, Supplement material). Baseline emissions refer to remaining emissions in the respective cropping period . Total two years N2O emissions are represented by the entire bar and by values displayed on top. Mean cumulative N2O emissions (n = 8) are displayed per treatment with CT – ploughing, RT – reduced tillage, SL – slurry and MC – manure compost. Significant tillage/fertiliser system effects on total N2O-N emissions and emissions in each period are shown on the right hand side (ANCOVA, F-test, Level of significance: (*)p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ns = not significant).

Table 3.

Soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks (Mg ha−1) in three soil layers (0–0.1, 0.1–0.2, 0.2–0.5 m) and total SOC stocks (0–0.5 m) sampled in 2014/2015. Total SOC stocks are given as sum of SOC stocks per soil layer and normalised to the total mean soil mass of CT plots by the equivalent soil mass approach (ESM) after Appel (2011). Means (SE, n = 4) are given per treatment and ANCOVA results mark significant differences between tillage and fertiliser systems. SOC concentrations and bulk densities are given in Table S3 in the Supplementary material.

| SOC stocks per soil layer |

total SOC stocks (0–0.5 m) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | 0–0.1 m | 0.1–0.2 m | 0.2–0.5 m | sum | ESM corrected |

| CT-SL | 25.4 (1.4) | 26.8 (1.4) | 48.1 (5.8) | 100.3 (8.5) | 101.2 (10.9) |

| CT-MC | 28.2 (1.7) | 28.1 (1.7) | 50.3 (3.5) | 106.6 (5.8) | 107.9 (8.6) |

| RT-SL | 29.8 (1.0) | 29.2 (1.5) | 49.7 (3.9) | 108.7 (6.2) | 109.2 (8.0) |

| RT-MC | 31.2 (0.9) | 28.8 (1.7) | 47.8 (3.6) | 107.8 (6.0) | 109.3 (8.4) |

| ANCOVA (F-Statistics and significance levels) | |||||

| Clay content | 3.2 × 1010*** | 231.7 *** | 147.9 *** | 277.0 *** | 193.1 *** |

| Tillage | 4.8 × 108*** | 4.0 (*) | 11.0 ** | 1.8 ns | 0.4 ns |

| Fertilisation | 1.4 × 109*** | 18.4 ** | 3.1 ns | 1.1 ns | 1.9 ns |

| Tillage x Fert. | 2.2 × 102*** | 17.2 ** | 3.1 ns | 8.5 * | 6.2 * |

Treatments: CT – ploughing, RT – reduced tillage, SL – slurry, MC – manure compost. ns = not significant.

(*)p < 0.1. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Multiple regression of time series data of log transformed N2O fluxes (μg m−2 h−1) and soil properties over the course of two years. Soil properties include nitrate, ammonium and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentrations (mg kg−1), water filled pore space (WFPS, %) and soil temperature (°C). Parameter estimates (B), standard errors and t-statistics are given. Temporal correlation between sampling dates was considered in the generalised least square model.

| Parameter | B | B SE | t(417) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −3.41 | 0.36 | −9.4 | <0.001 |

| log(Nitrate) | 0.48 | 0.05 | 10.5 | <0.001 |

| log(Ammonium) | −0.10 | 0.02 | −5.3 | <0.001 |

| log(DOC) | 0.43 | 0.06 | 7.2 | <0.001 |

| soil temperature | 0.08 | 0.004 | 18.2 | <0.001 |

| WFPS | 4.10 | 0.36 | 11.9 | <0.001 |

3. Results

3.1. Greenhouse gas fluxes and cumulative emissions

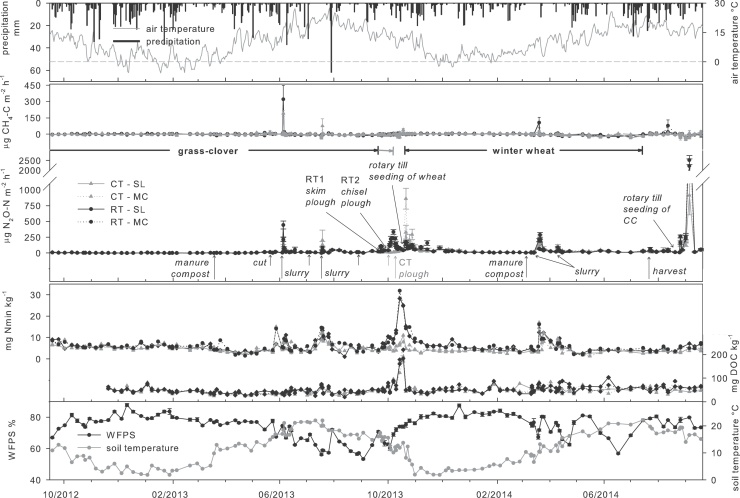

N2O and CH4 fluxes of the two year field monitoring are shown in Fig. 1. In contrast to the manure compost application, high N2O flux rates were measured after slurry application and after tillage operations. Minor elevated fluxes occurred also after some grass-clover cuts. The highest peak with a maximum flux of 3468 μg N2O-N m−2 h−1 followed seedbed preparation and seeding of a cover crop into a mix of wheat stubbles and volunteer grass under wet conditions in autumn 2014. Weather induced N2O emissions were only observed after a 60 mm rainfall following the second slurry application in grass-clover. Freezing/thawing induced emissions were not detected. Median N2O fluxes of the two year period ranged between 12 and 13 μg N2O-N m−2 h−1 with no treatment effect (statistics not shown). Cumulative N2O emissions ranged from 0.8 to 0.9 kg N2O-N ha−1 in grass-clover and from 2.1 to 3.0 kg N2O-N ha−1 in winter wheat (Table 2). The wheat period included N2O peak emissions after ley termination. There were no significant differences in cumulative N2O emissions between tillage systems in both cropping seasons. Yet, N2O emissions induced after tillage operations were higher in RT than in CT (Fig. 2). If the large N2O peak emitted after cover crop seeding following winter wheat was included to complete a two year dataset, overall cumulative N2O emissions were consequently higher in RT than CT. As tillage induced N2O emissions were increased in MC compared with SL plots, overall cumulative N2O emissions were higher in MC (Fig. 2). N2O emission factors per crop are shown in Table 2. If N2O emissions of the full two years and all fertiliser N inputs were considered, mean N2O emission factors accounted for 2.3% (uncorrected) and 0.7% (background corrected), respectively. Cumulative N2O emissions of the unfertilised control used for background correction are displayed in Table S2, in Supplement material.

Fig. 1.

N2O and CH4 fluxes, soil (0–0.2 m) and environmental parameters during a two year monitoring in a grass-clover – winter wheat – cover crop (CC) sequence.

Means (±SE, n = 8) of gas fluxes besides mineral nitrogen (Nmin, nitrate + ammonium) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) contents, that were sampled treatment wise are displayed per treatment with CT – ploughing, RT – reduced tillage, SL – slurry and MC – manure compost. Soil water filled pore space (WFPS) is shown as mean (±SE, n = 4) across all treatments. Soil temperature in 0.1 m depth was recorded once during sampling. Daily precipitation and mean daily air temperature derive from the weather station.

Concerning CH4 fluxes, short-lived pulses were detected directly after slurry application with a maximum flux of 1172 μg CH4-C m−2 h−1. Overall, the studied soil acted as a CH4 sink with low median uptake rates between −1.4 and −1.9 μg CH4-C m−2 h−1 and no treatment effects (statistics not shown). There were no clear treatment effects on cumulative CH4 emissions between the cropping seasons (Table 2).

3.2. Soil parameters

Repeated soil sampling of pooled samples per treatment (0–0.2 m) over the two year monitoring period revealed overall higher mean and median nitrate and DOC concentrations in RT than CT (Table S4, in Supplement material). Ammonium concentrations and WFPS did not differ between tillage treatments. C and N availability increased from the unfertilised control to the fertilised treatments. Aggregated mineral N, DOC and WFPS data per sampling date are shown in Fig. 1.

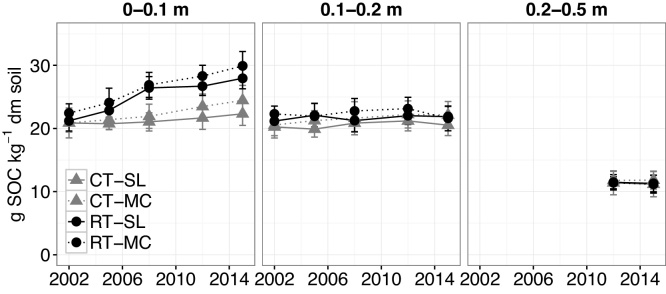

SOC concentrations increased from trial start in 2002 to 2015 in the top 0–0.1 m but not in the lower soil layers (Fig. 3). In 2015, significantly higher SOC, CFE-C and N (microbial biomass) concentrations were found in 0–0.1 m of RT compared to CT and for SOC concentrations also in MC than SL (Table S3, in Supplement material). SOC concentrations correlated spatially to the clay content within the trial (0–0.1 m, b = 8.4, t(14) = 4.7, p < 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.59) and to CFE-C concentrations over all soil depths (0–0.5 m, b = 0.02, t(46) = 26.1, p < 0.0001, adj.R2 = 0.94). Conversion from CT to RT significantly increased SOC stocks in 0-0.1 m (+17% in SL, +11% in MC) and in tendency in 0.1–0.2 m (+9% in SL, +2% in MC, Table 3). In the lower soil layer (0.2–0.5 m) however, either a slight increase in SL (+3%) or a depletion in MC (−5%) was observed. ESM corrected total SOC stocks (0–0.5 m) were finally higher in RT than in CT in SL (+8%, 8.0 Mg ha−1) and similar in MC (+1%, 1.4 Mg ha−1). The relative increase from CT-SL to the largest enrichment in RT-MC accounted for +8% (8.1 Mg ha−1).

Fig. 3.

Development of soil organic carbon (SOC) concentrations from trial start in 2002 to 2015 in three soil layers (0–0.1, 0.1–0.2, 0.2–0.5 m). Means (±SE, n = 4) are displayed per treatment with CT – ploughing, RT – reduced tillage, SL – slurry and MC – manure compost.

3.3. Drivers of N2O emissions

N2O fluxes during the two sampled years were positively correlated to soil temperature, water filled pore space (WFPS), nitrate and DOC while a slight negative correlation was found for ammonium (Table 4). There was a positive relation of log transformed N2O and CO2 fluxes after tillage operations (b = 0.7, t(806) = 26.8, p < 0.0001). The sum of cumulative tillage induced N2O emissions according to Fig. 2 correlated positively to topsoil SOC concentrations (b = 2.4, t(14) = 4.2, p < 0.001, adj.R2 = 0.52) and topsoil CFE-C (b = 0.01, t(14) = 3.5, p < 0.05, adj.R2 = 0.42). Including the unfertilised control, the sum of cumulative N2O emissions induced by slurry application correlated to the slurry Nt applied (b = 0.002, t(34) = 5.1, p < 0.0001, adj.R2 = 0.42) which was higher in SL than MC. However, total cumulative N2O emissions of the two years correlated only slightly with total N input by all fertilisers (b = 0.01, t(34) = 2.7, p < 0.05, adj.R2 = 0.15).

4. Discussion

4.1. N2O emissions and drivers

Cumulative N2O emissions of 0.7–0.9 kg N ha−1 were in the lower range of 0.5–3 kg N ha−1 reported for organic grass-clover leys in European temperate climates (Ball et al., 2002, Ball et al., 2014, Nadeem et al., 2012, Brozyna et al., 2013). Studies reporting N2O emissions in organic winter wheat varied with precrop with 0.5–1.8 kg N ha−1 after potato (Chirinda et al., 2010, Brozyna et al., 2013) and 4.0 kg N ha−1 after soybean (Johnson et al., 2012). Wheat N2O emissions in our monitoring (2.1–3.0 kg N ha−1) relate more to the latter study which confirms findings of increased N2O emissions following the incorporation of legumes (Ball et al., 2007, Jensen et al., 2012, Brozyna et al., 2013) due to high denitrification rates in relation with easy decomposable legume C and N (Jensen et al., 2012). With our sampling scheme, we covered management induced and rewetting emissions well. Freezing/thawing emissions, that can be relevant for annual N2O budgets in temperate climates (Kaiser and Ruser, 2000), were however not found in sampled occasions. Those could have either been missed by the manual sampling scheme or were negligible due to mild winters with hardly any frost during the monitoring period. The extended weekly sampling scheme used in this study was found to provide less than 10% deviation compared with cumulative N2O emissions obtained with automated, near continuous measurements (Flessa et al., 2002). We therefore expect that measured cumulative emissions provide realistic estimates with some remaining uncertainty.

Treatment impacts on N2O emissions varied between tillage and fertilisation systems. Tillage system effects were thereby not that clear and have to be distinguished between cumulative emissions per cropping season and responses to single tillage operations. In our study, there was no tillage system impact on cumulative N2O emissions in the grass-clover and wheat cropping season after more than ten years of differentiated management. Results therefore confirm minor tillage system effects on N2O budgets under conventional management, as reported in a meta-analysis for different crops (van Kessel et al., 2013) and for wheat in similar climatic conditions (Koga et al., 2004, Grandy et al., 2006, Chatskikh et al., 2008, Fuss et al., 2011). Yet, N2O peaks induced by single tillage operations were higher in RT than CT. In the wheat period, higher fluxes in RT after ley termination were outbalanced by higher fluxes in CT during the growing season with no overall tillage system impact on cumulative emissions. However, the large peak following the seeding of a green manure after wheat harvest highly influenced the two year gross N2O budget with consequently higher overall emissions in RT than CT. As this peak assigned more to the following but not sampled maize crop, it remains an open question if higher emissions in RT would have been again compensated in CT thereafter. A similar response to tillage operations was seen by Chatskikh et al. (2008) in Denmark who also found higher N2O fluxes in RT than CT after autumn tilling for winter wheat. Fluxes during the wheat growing period however did not show large differences in their case. The study of Olesen et al. (2005) conducted in the same Danish trial, found that a tillage operation reduced the ammonium-oxidation potential in CT by 20% in relation to RT but not other enzyme activities (dehydrogenase, arylsulfatase). A laboratory study accompanying our field monitoring revealed higher abundances of ammonium oxidising bacteria and archaea in RT compared with CT soils (Krauss et al., 2017). Higher NO3− concentrations were furthermore observed in RT than CT during the field monitoring, especially after ley termination where moisture conditions were ideal for nitrification. Higher N2O fluxes after tillage operations in RT may thus indicate enhanced nitrification related N2O emissions during phases of high microbial activity. Nitrification and nitrifier denitrification are found to contribute largely to N2O emissions in a range of 50–70% water filled pore space (Kool et al., 2011). Which processes lead to enhanced N2O emissions in the rest of the wheat season in CT remains unsolved. Higher N2O fluxes after tillage operations in RT than in CT and also in MC than SL reflected the significant differences in topsoil SOC and microbial biomass between treatments. They may however also relate to the differing input of organic residues during tillage (more grass-clover stubbles and weeds in RT and manure particles in MC) which cannot fully be clarified. To our knowledge, effects of soil organic matter on tillage induced N2O emissions were not observed yet. The size of N2O fluxes after tillage operations was beyond regulated by actual moisture and temperature conditions as commonly reported (Butterbach-Bahl et al., 2013) and were therefore higher under wet and warm soil conditions.

Regarding fertilisation systems, short-term N2O pulses were induced by slurry application, but not after spreading of manure compost superficially. However, N2O fluxes were higher in MC than in SL after tillage operations later in the year, where the manure compost was incorporated. Overall, cumulative N2O emissions were ultimately higher in MC than SL over the two years. Our hypothesis that less available nitrogen in solid manures and better conditions for denitrification during slurry application would lead to lower annual N2O emissions by solid fertilisation, as found by Gregorich et al. (2005), was consequently rejected. Instead, the higher microbial biomass and topsoil SOC stocks from the long-term manure application and their effect on tillage induced emissions, seemed to have a greater impact on cumulative N2O emissions than the high short-term pulses after slurry application. Also Mogge et al. (1999), who compared N2O emissions in long-term farmyard manure (FYM) and slurry amended fields similar to our study, related overall higher N2O emissions in FYM amended fields to increased SOC and microbial biomass contents. The varying impact of organic fertiliser systems on N2O emissions may thus be more C than N driven in the long-term. Differing temporal response to fertiliser application, a high share of tillage induced N2O emissions to total emissions and relatively high background emissions (on average 0.6 kg N2O-N ha−1 in grass-clover and 1.8 kg N2O-N ha−1 in wheat) may explain the weak relationship of total cumulative N2O emissions with total N input by fertiliser application in our study. It indicates that N2O production is not a simple response to fertilisation rate as reported for mineral fertilisation (Shcherbak et al., 2014). Following the results from our study, N derived from soil organic matter and from biological nitrogen fixation are likely important sources for N2O emissions, too. The intrinsic complexity of soil derived N2O emissions thus questions the current calculation of N2O emission factors (IPCC, 2006) in the context of organic rotations at least on a crop basis (Brozyna et al., 2013). It is therefore suggested that emission factors derived from greenhouse gas monitoring of an entire crop rotation would better acknowledge the complexity of organic farming systems. Improving biophysical modelling approaches, which can also handle other N sources than just fertiliser input, is very much recommended to have more realistic N2O emission estimates for upscaling.

4.2. CH4 emissions

A clear treatment effect of neither tillage nor fertilisation system on cumulative CH4 emissions/uptake could be found between cropping seasons in our study, presumably due to the overlapping effect of CH4 emissions after slurry applications and CH4 uptake for most of the year. Under field conditions, no tillage system effects on CH4 uptake (Regina and Alakukku, 2010, Tellez-Rio et al., 2015) or a higher uptake in NT/RT than CT (Kessavalou et al., 1998, Koga et al., 2004, Ussiri et al., 2009) were reported for mineral fertilised upland soils. This shows that tillage system effects are not that clear in practice although a higher potential to oxidise CH4 in long-term NT managed soils was found in lab studies (Hütsch, 1998, Jacinthe et al., 2014, Prajapati and Jacinthe, 2014).

In our study, the median CH4 uptake rate of 0.04 mg CH4-C m−2 d−1 was lower than uptake rates of arable studies collected in a review by Hütsch (2001) with a range of 0.05–1.03 mg CH4-C m−2 d−1. This can be explained by the high clay content restricting gaseous diffusion (Boeckx et al., 1997) and by the regular application of animal manures which have the potential to inhibit CH4 oxidation in the long run (Hütsch, 2001). Overall low uptake rates may also explain inconsistent treatment effects.

Slurry application was found to induce short-lived CH4 peaks, which were higher in SL than MC plots, according to the amount of slurry applied. It has been suggested that CH4 peaks after slurry application are attributable to emissions from the slurry itself (Chadwick and Pain, 1997). The short peak duration can be explained by the inhibition of methanogenesis in the slurry when O2 starts to diffuse into the manure spread at soil surface (Chadwick et al., 2011). CH4 peaks were most pronounced in RT-SL plots that ultimately resulted in the lowest cumulative CH4 uptake. As bulk densities in the top ten centimetres were lower in RT and there are indications that reduced tillage intensity increases infiltration (Strudley et al., 2008), it is unlikely that logging of slurry at soil surface caused increased emissions. Increased CH4 emissions may relate to the higher SOC content in RT than in CT, as Chadwick and Pain (1997) found higher CH4 emissions in a SOC rich clay compared with a sandy soil after adding different slurries. They however questioned if this was a C and N effect or a different infiltration behaviour. It therefore remains speculative as no study exists to our knowledge that assessed slurry induced CH4 emissions in soils with the same texture but varying tillage history.

4.3. SOC stocks and relevance for climate change mitigation

Time series of SOC concentrations indicated that a new equilibrium was not reached yet in RT thirteen years after conversion. Topsoils were still accumulating SOC, a process that was estimated to take 20–50 years (Smith, 2004). This was also seen in SOC stocks. Taking CT-SL as a starting point, which was the management system before trial start and which further represents a common management system in Switzerland, both, conversion to RT and MC increased SOC stratification. While SOC stocks in each soil layer were increased by CT-MC and RT-SL management, the most pronounced stratification in relation to CT-SL was detected in RT-MC with highest accumulation of SOC in the surface layer and a slight SOC depletion in 0.2–0.5 m. This can be explained by the incorporation of the C rich manure compost into the RT topsoil layer only. Ploughing mixed the manure compost more thoroughly in this regard, and slurry is able to migrate into deeper soil layers. Fertilisation with liquid or solid manures had thus an interactive effect with tillage on SOC stratification. This effect might explain the pronounced SOC stock stratification in RT soils when rotted manure was used (Schulz et al., 2014) and the lacking difference in SOC stocks by mixed slurry and manure application (Crittenden et al., 2015). The observed stratification is in accordance with findings from meta-analyses where SOC stock changes from conversion of CT to NT lead to superficial accumulation and subsoil depletion (Angers and Eriksen-Hamel, 2008, Luo et al., 2010). Luo et al. (2010) also explained the decline in subsoil SOC as a result of lacking redistribution of surface soil C into deeper soil layers by ploughing and added that restricted root growth due to soil compaction may limit root penetration into deeper soil layers in addition.

In their global meta-analysis, changes in total SOC stocks (>0.4 m profile depth) between NT and CT were overall small and insignificant (Luo et al., 2010). Much larger variation was found for RT systems in temperate Europe with extended crop rotations and the application of animal manure: In our study, lowest total SOC stocks (0-0.5 m were found in the CT-SL treatment. Both, reducing tillage intensity and additional application of manure compost showed a SOC stock increase after thirteen years (+8.1 Mg C ha−1, 0-0.5 m). Viaud et al. (2011) only found slight but insignificant increase in total SOC stocks by RT and manuring after eight years (+3.5 and +5.8 Mg C ha−1, respectively, 0–0.4 m). Crittenden et al. (2015) reported no changes between tillage treatments after three years (0–0.5 m) and Schulz et al. (2014) detected an insignificant decrease in total SOC stocks in RT compared with CT after eleven years (−6.6 Mg C ha−1, 0–0.9 m). Differences between studies are likely related to soil texture, experimental duration and different manure management. As clay minerals are known to form organo-mineral complexes that bind organic matter (von Luetzow et al., 2006), the high clay content (45%) at our site might already explain the pronounced SOC stock increase compared to the other studies with clay contents between 17 and 29%. It therefore seems, that conclusions about the SOC sequestration potential of RT systems with manure based fertilisation cannot be drawn yet and that further investigations are needed.

To understand if a management system change serves as a climate change mitigation option, N2O and CH4 emissions have to be considered besides SOC stock changes. A relative evaluation between the standard and an alternative system was therefore performed as proposed by Li et al. (2005) comparing RT-MC with CT-SL. For such a relative assessment, measured SOC stocks after 13 years, and cumulative N2O and CH4 emissions of the two years field monitoring were normalised to annual fluxes and converted to CO2-equivalents like in Li et al. (2005) but with updated global warming potentials (N2O = 265, CH4 = 28, IPCC, 2014). The relative change in CO2-equivalent emissions between RT-MC and CT-SL resulted in overall 1763 kg CO2 eq. ha−1 a−1 less emissions in RT-MC due to the high increase in SOC stocks (ΔSOC: −2308 kg, ΔN2O: +545 kg, ΔCH4: +0.2 kg CO2-eq. ha−1 a−1). Our estimates were lower than examples assessed by Li et al. (2005, Table IV) including a study that compared no-till versus ploughing (−670 kg CO2-eq. ha−1 a−1) and a study about manure addition versus no fertilisation (+2700 kg CO2-eq. ha−1 a−1). In contrast to their findings, the estimate in our case suggests that the management change towards reduced tillage and manure compost application contributed to greenhouse gas mitigation during the years of ongoing SOC accumulation which will be likely temporally limited. As this refers to direct changes in the field, greenhouse gas emissions during manure management or diesel use were not considered and would be required for a Life Cycle Assessment.

5. Conclusions

This study filled important knowledge gaps about the impact of organic reduced tillage on greenhouse gas emissions, SOC stock changes and its potential for climate change mitigation. We demonstrated that i) organic reduced tillage increased SOC stocks after 13 years compared to ploughing in slurry fertilised plots and that tillage system effects were of minor importance in terms of N2O and CH4 emissions when the cropping seasons were considered. N2O fluxes after single tillage events were however higher in the reduced system. We further observed that ii) fertilising with manure compost increased N2O emissions and SOC stocks compared to fertilisation with slurry with little effects on CH4 uptake. The results indicated that reduced tillage and manure compost application were both valuable measures for climate change mitigation in relation to the traditional ploughing system with slurry application due to the domination of SOC sequestration in the first decade after conversion. N2O fluxes were triggered by actual pedoclimatic conditions and influenced by soil biochemical properties. To reduce the impact of tillage operations on N2O emissions, it is recommended to reduce tillage frequency and to adjust tillage timing to cold and dry soil conditions whenever possible.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all colleagues who helped with the labour intensive monitoring, namely the technicians Frédéric Perrochet, Adolphe Munyangabe and Anton Kuhn and various students and interns, Marie Arndt, Christoph Barendregt, Scott Brainard, Cornelia Bufe, Amanda Buol, Roman Hüppi, Hannes Keck, Johanna Rüegg, Colin Skinner, Simone Spangler and Hassan Younes. We also like to thank Alfred Berner and Alfred Schädeli who managed the Frick tillage trial. For the assistance with bulk density calculations in relation to the clay content, we thank Frédéric Lamy and Pascal Boivin of Hepia Geneva. We furthermore thank Simon Moakes for the language check. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this project provided by COOP Sustainability fund and the CORE Organic II funding bodies, being partners of the FP7 ERA-Net project (www.coreorganic2.org). We thank the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) for financing the gas chromatograph and the Software AG-Stiftung, Stiftung zur Pflege von Mensch, Mitwelt und Erde and Swiss Federal Office for Agriculture (FOAG) for financing the Frick tillage trial.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.01.029.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Agroscope, 2012 Referenzmethoden der Forschungsanstalten Agroscope: Band 1, Bodenuntersuchungen zur Düngeberatung, Bestimmung des organisch gebundenen Kohlenstoffs (Corg), Switzerland.

- Alves B.J.R., Smith K.A., Flores R.A., Cardoso A.S., Oliveira W.R.D., Jantalia C.P., Urquiaga S., Boddey R.M. Selection of the most suitable sampling time for static chambers for the estimation of daily mean N2O flux from soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012;46:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Angers D.A., Eriksen-Hamel N.S. Full-inversion tillage and organic carbon distribution in soil profiles: a meta-analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2008;72:1370–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Appel T. DBG; Berlin: 2011. Weniger Kohlenstoff im Boden nach langjährig pflugloser Bodenbearbeitung. DBG Tagung, Böden verstehen, Böden nutzen, Böden fit machen. [Google Scholar]

- Ball B.C., McTaggart I.P., Watson C.A. Influence of organic ley-arable management and afforestation in sandy loam to clay loam soils on fluxes of N2O and CH4 in Scotland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002;90:305–317. [Google Scholar]

- Ball B.C., Watson C.A., Crichton I. Nitrous oxide emissions, cereal growth, N recovery and soil nitrogen status after ploughing organically managed grass/clover swards. Soil Use Manag. 2007;23:145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ball B.C., Griffiths B.S., Topp C.F.E., Wheatley R., Walker R.L., Rees R.M., Watson C.A., Gordon H., Hallett P.D., McKenzie B.M., Nevison I.M. Seasonal nitrous oxide emissions from field soils under reduced tillage, compost application or organic farming. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014;189:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Berner A., Hildermann I., Fließbach A., Pfiffner L., Niggli U., Mäder P. Crop yield and soil fertility response to reduced tillage under organic management. Soil Tillage Res. 2008;101:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Boeckx P., Van Cleemput O., Villaralvo I. Methane oxidation in soils with different textures and land use. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 1997;49:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Brozyna M.A., Petersen S.O., Chirinda N., Olesen J.E. Effects of grass-clover management and cover crops on nitrogen cycling and nitrous oxide emissions in a stockless organic crop rotation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013;181:115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Butterbach-Bahl K., Baggs E.M., Dannenmann M., Kiese R., Zechmeister-Boltenstern S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: how well do we understand the processes and their controls? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2013;368 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande M., Peigné J., Payet V., Mäder P., Sans F.X., Blanco-Moreno J.M., Antichi D., Bàrberi P., Beeckman A., Bigongiali F., Cooper J., Dierauer H., Gascoyne K., Grosse M., Heß J., Kranzler A., Luik A., Peetsmann E., Surböck A., Willekens K., David C. Organic farmers’ motivations and challenges for adopting conservation agriculture in Europe. Org. Agric. 2015:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick D.R., Pain B.F. Methane fluxes following slurry applications to grassland soils: laboratory experiments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1997;63:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick D., Sommer S.G., Thorman R., Fangueiro D., Cardenas L., Amon B., Misselbrook T. Manure management: implications for greenhouse gas emissions. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011;166–67:514–531. [Google Scholar]

- Chatskikh D., Olesen J.E., Hansen E.M., Elsgaard L., Petersen B.M. Effects of reduced tillage on net greenhouse gas fluxes from loamy sand soil under winter crops in Denmark. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008;128:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chirinda N., Carter M.S., Albert K.R., Ambus P., Olesen J.E., Porter J.R., Petersen S.O. Emissions of nitrous oxide from arable organic and conventional cropping systems on two soil types. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010;136:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J., Baranski M., Stewart G., Nobel-de Lange M., Bàrberi P., Fließbach A., Peigné J., Berner A., Brock C., Casagrande M., Crowley O., David C., De Vliegher A., Döring T.F., Dupont A., Entz M., Grosse M., Haase T., Halde C., Hammerl V., Huiting H., Leithold G., Messmer M., Schloter M., Sukkel W., van der Heijden M.G.A., Willekens K., Wittwer R., Mäder P. Shallow non-inversion tillage in organic farming maintains crop yields and increases soil C stocks: a meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016;36:22. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden S.J., Poot N., Heinen M., van Balen D.J.M., Pulleman M.M. Soil physical quality in contrasting tillage systems in organic and conventional farming. Soil Tillage Res. 2015;154:136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Derpsch R., Friedrich T., Kassam A., Li H. Current status of adoption of no-till farming in the world and some of its main benefits. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2010;3:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ellert B.H., Bettany J.R. Calculation of organic matter and nutrients stored in soils under contrasting management regimes. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1995;75:529–538. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerling C. Reduced and conservation tillage effects on soil ecological properties in an organic farming system. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2007;24:363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Flessa H., Dörsch P., Beese F. Seasonal variation of N2O and CH4 fluxes in differently managed arable soils in southern Germany. J. Geophys. Res. 1995;100:23115–23124. [Google Scholar]

- Flessa H., Ruser R., Schilling R., Loftfield N., Munch J.C., Kaiser E.A., Beese F. N2O and CH4 fluxes in potato fields: automated measurement, management effects and temporal variation. Geoderma. 2002;105:307–325. [Google Scholar]

- Fließbach A., Oberholzer H.-R., Gunst L., Mäder P. Soil organic matter and biological soil quality indicators after 21 years of organic and conventional farming. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007;118:273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana M., Berner A., Mäder P., Lamy F., Boivin P. Soil organic carbon and soil bio-physicochemical properties as co-influenced by tillage treatment. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2015;79:1435–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Fuss R., Ruth B., Schilling R., Scherb H., Munch J.C. Pulse emissions of N2O and CO2 from an arable field depending on fertilization and tillage practice. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011;144:61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Gadermaier F., Berner A., Fließbach A., Friedel J.K., Mäder P. Impact of reduced tillage on soil organic carbon and nutrient budgets under organic farming. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2012;27:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gattinger A., Müller A., Haeni M., Skinner C., Fliessbach A., Buchmann N., Mäder P., Stolze M., Smith P., Scialabba N.E.-H., Niggli U. Enhanced top soil carbon stocks under organic farming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:18226–18231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209429109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandy A.S., Loecke T.D., Parr S., Robertson G.P. Long-term trends in nitrous oxide emissions, soil nitrogen, and crop yields of till and no-till cropping systems. J. Environ. Qual. 2006;35:1487–1495. doi: 10.2134/jeq2005.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorich E.G., Rochette P., VandenBygaart A.J., Angers D.A. Greenhouse gas contributions of agricultural soils and potential mitigation practices in Eastern Canada. Soil Tillage Res. 2005;83:53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hütsch B.W. Tillage and land use effects on methane oxidation rates and their vertical profiles in soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 1998;27:284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hütsch B.W. Methane oxidation in non-flooded soils as affected by crop production – invited paper. Eur. J. Agron. 2001;14:237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M., Frey B., Mayer J., Mäder P., Widmer F. Distinct soil microbial diversity under long-term organic and conventional farming. ISME J. 2015;9:1177–1194. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC, 2006. Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (Volume 4) – Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use − Chapter 11: N2O emissions from managed soils, and CO2 emissions from lime and urea application.

- IPCC . IPCC; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Google Scholar]

- Jacinthe P.-A., Dick W.A., Lal R., Shrestha R.K., Bilen S. Effects of no-till duration on the methane oxidation capacity of Alfisols. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2014;50:477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen E.S., Peoples M.B., Boddey R.M., Gresshoff P.M., Hauggaard-Nielsen H.J.R., Alves B., Morrison M.J. Legumes for mitigation of climate change and the provision of feedstock for biofuels and biorefineries. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012;32:329–364. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.M.F., Weyers S.L., Archer D.W., Barbour N.W. Nitrous oxide, methane emission, and yield-scaled emission from organically and conventionally managed systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2012;76:1347–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser E.A., Ruser R. Nitrous oxide emissions from arable soils in Germany – an evaluation of six long-term field experiments. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2000;163:249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Kessavalou A., Mosier A.R., Doran J.W., Drijber R.A., Lyon D.J., Heinemeyer O. Fluxes of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane in grass sod and winter wheat-fallow tillage management. J. Environ. Qual. 1998;27:1094–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Koga N., Tsuji H. Effects of reduced tillage, crop residue management and manure application practices on crop yields and soil carbon sequestration on an Andisol in Northern Japan. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2009;55:546–557. [Google Scholar]

- Koga N., Tsuruta H., Sawamoto T., Nishimura S., Yagi K. N2O emission and CH4 uptake in arable fields managed under conventional and reduced tillage cropping systems in northern Japan. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2004;18 [Google Scholar]

- Kong A.Y.Y., Fonte S.J., van Kessel C., Six J. Transitioning from standard to minimum tillage: Trade-offs between soil organic matter stabilization, nitrous oxide emissions, and N availability in irrigated cropping systems. Soil Tillage Res. 2009;104:256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Kool D.M., Dolfing J., Wrage N., Van Groenigen J.W. Nitrifier denitrification as a distinct and significant source of nitrous oxide from soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011;43:174–178. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss M., Krauss H.-M., Spangler S., Kandeler E., Behrens S., Kappler A., Mäder P., Gattinger A. Tillage system affects fertilizer-induced nitrous oxide emissions. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2017;53:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz M., Berner A., Gattinger A., Scholberg J.M., Mäder P., Pfiffner L. Influence of reduced tillage on earthworm and microbial communities under organic arable farming. Pedobiologia. 2013;56:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Leiber-Sauheitl K., Fuß R., Voigt C., Freibauer A. High greenhouse gas fluxes from grassland on histic gleysol along soil carbon and drainage gradients. Biogeosci. Disc. 2013;10:11283–11317. [Google Scholar]

- Li C.S., Frolking S., Butterbach-Bahl K. Carbon sequestration in arable soils is likely to increase nitrous oxide emissions, offsetting reductions in climate radiative forcing. Clim. Change. 2005;72:321–338. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z.K., Wang E.L., Sun O.J. Can no-tillage stimulate carbon sequestration in agricultural soils?: A meta-analysis of paired experiments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010;139:224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Mäder P., Berner A. Development of reduced tillage systems in organic farming in Europe. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2012;27:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mäder P., Fließbach A., Dubois D., Gunst L., Fried P., Niggli U. Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science. 2002;296:1694–1697. doi: 10.1126/science.1071148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltas A., Charles R., Jeangros B., Sinaj S. Effect of organic fertilizers and reduced-tillage on soil properties, crop nitrogen response and crop yield: Results of a 12-year experiment in Changins, Switzerland. Soil Tillage Res. 2013;126:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mogge B., Kaiser E.A., Munch J.C. Nitrous oxide emissions and denitrification N-losses from agricultural soils in the Bornhoved Lake region: influence of organic fertilizers and land-use. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999;31:1245–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Müller T., Joergensen R.G., Meyer B. Estimation of soil microbial biomass-C in the presence of living roots by fumigation extraction. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1992;24:179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem S., Hansen S., Bleken M.A., Dorsch P. N2O emission from organic barley cultivation as affected by green manure management. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:2747–2759. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen J.E., Hansen E.M., Elsgaard L. Udledning af drivhusgasser ved pløjefridyrkningssystemer. In: Olesen J.E., editor. Drivhusgasser fra jordbruget – reduktionsmuligheder DJF rapport. Danish Institute of Agricultural Science; Markbrug 113, Foulum, Denmark: 2005. pp. 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A.R. 2012. HMR: Flux Estimation with Static Chamber Data. [Google Scholar]

- Peigné J., Lefevre V., Vian J., Fleury P. Conservation agriculture in organic farming: experiences, challenges and opportunities in Europe. In: Farooq M., Siddique K., editors. Conservation Agriculture. Springer International Publishing; Switzerland: 2015. pp. 559–578. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J., Bates D., DebRoy S., Sarkar D., R Core Team . 2014. Nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. [Google Scholar]

- Pittelkow C.M., Liang X., Linquist B.A., van Groenigen K.J., Lee J., Lundy M.E., van Gestel N., Six J., Venterea R.T., van Kessel C. Productivity limits and potentials of the principles of conservation agriculture. Nature. 2015;517:365–368. doi: 10.1038/nature13809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powlson D.S., Bhogal A., Chambers B.J., Coleman K., Macdonald A.J., Goulding K.W.T., Whitmore A.P. The potential to increase soil carbon stocks through reduced tillage or organic material additions in England and Wales: a case study. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012;146:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati P., Jacinthe P.A. Methane oxidation kinetics and diffusivity in soils under conventional tillage and long-term no-till. Geoderma. 2014;230:161–170. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Regina K., Alakukku L. Greenhouse gas fluxes in varying soils types under conventional and no-tillage practices. Soil Tillage Res. 2010;109:144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rochette P. No-till only increases N2O emissions in poorly-aerated soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2008;101:97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz F., Brock C., Schmidt H., Franz K.-P., Leithold G. Development of soil organic matter stocks under different farm types and tillage systems in the Organic Arable Farming Experiment Gladbacherhof. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2014;60:313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbak I., Millar N., Robertson G.P. Global metaanalysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322434111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six J., Ogle S.M., Jay breidt F., Conant R.T., Mosier A.R., Paustian K. The potential to mitigate global warming with no-tillage management is only realized when practised in the long term. Glob. Change Biol. 2004;10:155–160. [Google Scholar]

- Six J., Frey S.D., Thiet R.K., Batten K.M. Bacterial and fungal contributions to carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2006;70:555–569. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner C., Gattinger A., Müller A., Mäder P., Flie ßbach A., Stolze M., Ruser R., Niggli U. Greenhouse gas fluxes from agricultural soils under organic and non-organic management - A global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;468–469:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. Soils as carbon sinks: the global context. Soil Use Manag. 2004;20:212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Strudley M.W., Green T.R., Ascough Ii J.C. Tillage effects on soil hydraulic properties in space and time: State of the science. Soil Tillage Res. 2008;99:4–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tellez-Rio A., Garcia-Marco S., Navas M., Lopez-Solanilla E., Tenorio J.L., Vallejo A. N2O and CH4 emissions from a fallow-wheat rotation with low N input in conservation and conventional tillage under a Mediterranean agroecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;508:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussiri D.A.N., Lal R., Jarecki M.K. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions from long-term tillage under a continuous corn cropping system in Ohio. Soil Tillage Res. 2009;104:247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Viaud V., Angers D.A., Parnaudeau V., Morvan T., Menasseri-Aubry S. Response of organic matter to reduced tillage and animal manure in a temperate loamy soil. Soil Use Manag. 2011;27:84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Agilent Technologies Inc.; USA: 2010. Simultaneous Analysis of Greenhouse Gases by Gas Chromatography. Application Note. [Google Scholar]

- Watson C.A., Atkinson D., Gosling P., Jackson L.R., Rayns F.W. Managing soil fertility in organic farming systems. Soil Use Manag. 2002;18:239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Yagioka A., Komatsuzaki M., Kaneko N., Ueno H. Effect of no-tillage with weed cover mulching versus conventional tillage on global warming potential and nitrate leaching. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015;200:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zikeli S., Gruber S., Teufel C.-F., Hartung K., Claupein W. Effects of reduced tillage on crop yield, plant available nutrients and soil organic matter in a 12-year long-term trial under organic management. Sustainability. 2013;5:3876–3894. [Google Scholar]

- van Kessel C., Venterea R., Six J., Adviento-Borbe M.A., Linquist B., van Groenigen K.J. Climate, duration, and N placement determine N2O emissions in reduced tillage systems: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2013;19:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Luetzow M., Koegel-Knabner I., Ekschmitt K., Matzner E., Guggenberger G., Marschner B., Flessa H. Stabilization of organic matter in temperate soils: mechanisms and their relevance under different soil conditions – a review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2006;57:426–445. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.