Abstract

This article evaluates whether arranged marriage declined in India from 1970 to 2012. Specifically, the authors examine trends in spouse choice, the length of time spouses knew each other prior to marriage, intercaste marriage, and consanguineous marriage at the national level, as well as by region, urban residence, and religion/caste. During this period, women were increasingly active in choosing their own husbands, spouses meeting on their wedding day decreased, intercaste marriage rose, and consanguineous marriage fell. However, many of these changes were modest in size and substantial majorities of recent marriages still show the hallmarks of arranged marriage. Further, instead of displacing parents, young women increasingly worked with parents to choose husbands collectively. Rather than unilateral movement towards Western marriage practices, as suggested by theories of family change and found in other Asian contexts, these trends point to a hybridization of customary Western and Indian practices.

Modernization theory predicted that the great diversity of family behaviors found in non-Western countries would converge towards the Western nuclear model under the influence of industrialization and urbanization (Adams 2010; Goode 1963; McDonald 1993). Following this prediction, arranged marriage – a practice found largely in Asia and Africa in which parents and other family members select their children’s spouses – was expected to be replaced by Western style marriage, in which young people choose their own spouses.

This predicted decline of arranged marriage is usually conceptualized as a change in spouse choice, but it also points to other marital changes. In arranged marriages, parents customarily choose a spouse based on the caste/ethnicity, religion, and social and economic standing of the prospective spouse and their family and there is little to no contact between the prospective spouses prior to marriage. In the Western model of marriage, young people choose their own spouses on the basis of individual compatibility or love, usually gained through interactions before marriage (Macfarlane 1986; Thornton 2009). Thus, a decline of arranged marriage likely signals declines in the importance of ethnicity/caste, religion, and other aspects of the status of a prospective spouse and their family. It also implies increases in contact between prospective spouses before marriage and the importance of love or interpersonal compatibility.

Many predictions of family change found within modernization theory have been discredited, yet the theory continues to be influential. Non-western families have not uniformly converged towards the Western model and the Western nuclear family itself has undergone substantial changes in recent decades (Cherlin 2012). Yet, in many places, some of the family changes predicted by modernization theory have occurred, including widespread increases in age at marriage and declines in fertility (Bryant 2007; Ortega 2014; Raymo et al. 2015). Further, recent research on family change, including assessments of transitions from joint to nuclear families and early to late marital timing, is shaped by modernization theory (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002; Buttenheim and Nobles 2009; Niranjan, Nair and Roy 2005; Ruggles 2009).

A more recent theory of family change, developmental idealism theory, suggests that modernization theory itself is a driver of family change (Thornton 2001, 2005). According to developmental idealism theory, the values and beliefs found in modernization theory – including the valuation of Western family behaviors as good and modern and the beliefs that such behaviors are causes and consequences of development – have spread around the world. As people encounter and endorse these schemas, known collectively as developmental idealism, they increasingly adopt the Western family practices that match those schemas. Thus, while modernization theory points to economic drivers and developmental idealism highlights ideational forces, both predict the decline of arranged marriage.

An important first step in evaluating these theories relevance to marital change is establishing the extent to which arranged marriage has declined around the world. The existing empirical record suggests that parts of Asia and Africa have experienced substantial declines in arranged marriage. A small set of survey-based studies document declines in Kyrgyzstan (Nedoluzhko and Agadjanian 2015), Nepal (Axinn, Ghimire and Barber 2008; Ghimire et al. 2006), China (Xu and Whyte 1990; Zang 2007), Taiwan (Thornton, Chang and Lin 1994), Japan (Retherford and Ogawa 2006), Indonesia (Malhotra 1997), Malaysia (Jones 1994), Sri Lanka (Caldwell 1999), and Togo (Meekers 1995). For example, in Japan, the percent of women who had an arranged marriage fell from 60% among those married in the late 1950s to nearly zero in the early 2000s (Retherford and Ogawa 2006:17). Similarly, in Togo, the percent of women who had an arranged marriage fell from 46% among those married in the 1960s to 24% among those married in the 1980s (Meekers 1995). More broadly, ethnographic studies indicate that the valuation of love and choice, which are hallmarks of Western marriage, are increasingly salient to marriage in a wide range of settings (Cole and Thomas 2009; Harkness and Khaled 2014; Hirsch 2003; Hirsch and Wardlow 2006; Marsden 2007; Rebhun 1999; Yan 2003).

However, it is difficult to rigorously evaluate the extent of change in arranged marriage at global, regional, and even national scales. Measures of spouse choice and related behaviors are not standardly included in nationally representative surveys, such as the Demographic and Health Surveys. In turn, there are many countries for which no data are available. Further, many of the studies listed above use samples that are representative of cities or other localities within countries. Thus, many of the trends documented with available data cannot be generalized to countries as a whole.

This article aims to contribute to the empirical record by assessing whether arranged marriage has declined in India. Specifically, we examine changes from 1970 to 2012 in spouse choice, intercaste marriage, consanguineous marriage, and the length of time spouses knew each other prior to marriage. We examine trends in each of these behaviors at the national level, but also investigate variation by region, urban residence, and religion/caste. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the extent of change in arranged marriage at the national level in India.

India

India is a profoundly important context for understanding trends in arranged marriage. The kinship system, particularly among Hindus in the North, is strongly tied to arranged marriage, which sustains the patrilineal and patrilocal family system and the caste system (Karve 1965; Kolenda 1987). In fact, Jones (2010) classifies North India as the region that is most tied to arranged marriage in all of Asia. In addition to its theoretical relevance, the size of the population makes India a dominant force in broader regional and even global patterns. The Indian population numbers 1.3 billion, making it home to 18% of the world’s population (United Nations 2015).

Research on India itself further points to the need for better understanding of marital trends. Many studies suggest that the institution of arranged marriage may be under threat or is at least perceived to be so. Apparent growth in what are known colloquially as “love marriages” are described in ethnographic studies from Haryana (Chowdhry 2007), Delhi (Mody 2008), West Bengal (Allendorf 2013), Ladakh (Aengst 2014), Gujarat (Netting 2009), and Andhra Pradesh (Still 2011). In summarizing a collection of marriage ethnographies, Kaur and Patliwala (2014:9) conclude that “the articulated rules of partner selection have become muddied with the espousal of new ‘modern’ values of ‘love’ and ‘choice.’ Further, in keeping with developmental idealism theory, Uberoi (2006) notes that it is widely anticipated that arranged marriage will inevitably decline with India’s modernization. One Indian journalist was so convinced that the Indian family is growing to resemble the Western family that she travelled to Great Britain to witness there the supposed future of the Indian family up close (Prasad 2006). Young people choosing their own spouses for love is also commonly depicted in the mass media and popular Bollywood movies (Dwyer 2000; Uberoi 2006).

Other studies indicate that there are few, if any, changes in the dominance of arranged marriage in India. In an ethnography from Tamil Nadu, Fuller and Narasimhan (2008) suggest that the potential for interpersonal compatibility is now taken into account by parents when choosing spouses, but the broader practice of arranged marriage remains intact. In their classic article on the causes of marital change in South India, Caldwell and colleagues (1983) did not include a decline of arranged marriage among the titular changes, which instead comprised a growing surplus of brides, transition from bridewealth to dowry, and rise in women’s age at marriage. While they did describe a decline in consanguineous marriage at their fieldsite in Karnataka, they emphatically noted that “there is no claim of any decline in the significance of arranged marriage” (Caldwell, Reddy and Caldwell 1982:706). Most compellingly, less than 5% of women surveyed in the 2005 Indian Human Development Survey had the “primary role in choosing their husbands” (Desai and Andrist 2010:675). This measure of the stock of arranged marriages in 2005 does not directly assess the flow of arranged marriages in recent decades, but it does illustrate that arranged marriage must still be highly relevant in India.

Data

Our data comprise the only source of nationally representative data on arranged marriage, the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS). Specifically, we draw on both waves of the IHDS, the first collected in 2004–05 (IHDS-I) and the second in 2011–12 (IHDS-II) (Desai et al. 2007; Desai, Vanneman, and NCAER 2015). Together, these two waves comprise a panel study. The IHDS-I sample comprised 41,554 households, 83% of which were re-interviewed in IHDS-II. IHDS-II covered 42,152 households, including original IHDS-I households, households that split from original households, and a replacement sample of an additional 2,134 households.

Retrospective reports of marriage were collected in both waves from ever married women aged 15–49 residing in the selected households. Our analytical sample comprises 46,010 of these women, including 32,280 interviewed in IHDS-I and 13,730 interviewed only in IHDS-II. Since higher order marriages are rare in India and can differ in important ways from first marriages, we restricted our analysis to first marriages to ensure that trends over time are unaffected by changes in the composition of the sample by marriage order. Thus, we dropped the 988 women who had been married more than once and whose marriage reports referred to higher order marriages. We also restricted our analysis to those married in 1970 or later, dropping 270 women who married before 1970. An additional 365 women were excluded from the analytical sample because they were missing information for key variables. We should also note that the variable denoting if women were related to their husband by blood was missing in 1,258 cases. Thus, our analytical sample is further limited to 44,752 women for consanguineous marriage.

The absence of men in the sample may present a bias for estimates of spouse choice and possibly intercaste marriage. Surveys from other parts of Asia show that women exercise lower levels of spouse choice than men (Allendorf and Thornton 2015; Malhotra 1991). Ethnographic studies also suggest that men have more choice over their marriage in India as well (Allendorf 2013; Caldwell et al. 1983). Thus, our results likely underestimate the amount of choice exercised by the population of women and men as a whole. The other behaviors we examine, namely intercaste marriage, consanguineous marriage, and how long spouses knew each other before marriage, should be couple-level characteristics. Thus, using only women’s reports should not present a bias for the other behaviors. However, in a survey in neighboring Nepal, women reported substantially lower levels of intercaste marriage than men (Allendorf and Thornton 2015). If this finding is indicative of a broader regional pattern, the results presented here would also underestimate intercaste marriage.

Our measure of spouse choice is based on two questions. Women were first asked, “Who chose your husband?” with response options: 1) respondent herself, 2) respondent and parents/other relatives together, 3) parents or other relatives alone, or 4) other. Women who said their parents/other relatives alone chose their husband or chose the “other” option were also asked a yes or no, follow-up question: “Did you have any say in choosing him?” Using responses to both questions, we divided women’s choice spectrum into three categories. At one end of the spectrum are self-choice marriages, comprising all women in the “respondent herself” category for the first question. At the other end, are women who had no say in the choice, instead their parents (and/or others) chose their husbands by themselves. This category includes all women who said their parents/relatives or someone else chose their husband in the first question and said they had no say in response to the follow-up question. The third category includes all women between these extremes of choosing by themselves and having so say at all. This intermediate category includes the women who said that both they and their parents (or someone else) chose their husband together, as well as women who initially said that their parents (or someone else) chose, but when asked the follow-up question said they did have a say.

Our measure of length of acquaintanceship is taken verbatim from one question: “How long had you known your husband before you married him?” Response options included: 1) [met] on wedding or gauna (day of cohabitation) only, 2) less than one month, 3) more than one month, but less than one year, 4) more than one year, and 5) since childhood. We collapsed those who said “since childhood” into the “more than one year” category, but otherwise retained all response options.

It is important to note that there is ambiguity in this measure of length of acquaintanceship. We presume that most women interpreted “knowing” as meeting their (future) husband in person, but the interpretation may well have varied. As seen below, relatively large numbers of women reported meeting on their wedding day, even when they also said they chose their husbands by themselves. Thus, some women may have had more stringent interpretations of knowing, such as spending time in person without other people present or having some type of sustained contact. This ambiguity may also have been compounded by the translation of the questionnaire into several different languages; some languages may have had different implications for the meaning of “knowing.” It’s also possible that social desirability motivated some women to report meeting on their wedding day when they actually met earlier. Some evidence supporting this ambiguity and social desirability is found in the second round of the IHDS. In IHDS-II, women were also asked about additional contact with their (future) husband, including whether they had a chance to meet their husband before the marriage was fixed. Some responses to this question and the other question on how long they knew their husband before marriage appear to conflict. Specifically, 12% of the women who said they met on their wedding day, also said they did meet their husband before the marriage was fixed.

We should also emphasize that even if they did meet only on their wedding day, women may still have seen their husbands before marriage and had contact by email, letter, or phone. In the additional questions that appeared only in IHDS-II, women were asked whether they had talked on the phone, seen a photograph, or sent an email or internet chat before the marriage was fixed. Of those who said they met on their wedding day, 8% talked on the phone, 1% exchanged e-mail or internet chat, and 18% had seen his photo. Thus, some of the women who met on their wedding day may have developed feelings or expectations about their husband before marriage based on this type of contact.

Consanguineous marriage is the marriage of blood relatives. Thus, the measure is based on the question, “Are you related to your husband by blood?” All women who said yes are categorized as having a consanguineous marriage. Unlike the other marital behaviors we examine, consanguineous marriage is not customary across India. A preference for cross-cousin marriage, as well as marriage to uncles or other blood relatives, is only part of the southern kinship system (Dyson and Moore 1983; Karve 1965; Trautman 1981). Conversely, in the North, a blood relative is customarily not an acceptable spouse.

The measure of intercaste marriage is women’s subjective assessment that the two castes are different. Specifically, all women who said “no” to: “Is your husband’s family the same caste (jati) as your natal family?” It’s important to note that assessments of whether two castes (jatis) are the same can and does vary across individuals (Allendorf 2013; Beteille 1969). One person may say that two castes of similar origin and/or rank are the same, while another would say they are not. Thus, as noted above in the discussion of gender differences in Nepal, there is some ambiguity in this measure. Women may also under report intercaste marriage because of social desirability. These two limitations should work in opposite directions, however. We expect that women would take larger-grained views of caste for more recent marriages, which would reduce reporting of intercaste marriage for more recent marriages. At the same time, if the stigma of intercaste marriage is lessening over time and social desirability bias is declining, we would expect reporting of intercaste marriage to be higher for more recent marriages.

We measure change over time with marriage cohort. Specifically, we categorize women into four groups based on the calendar year in which their marriage took place, including 1970–79, 1980–89, 1990–99, and 2000–12. This approach can pose a truncation problem because survey data are limited to marriages experienced by women captured in the survey (Thornton 1994). In a context like India, with a relatively young age at marriage, the earliest marriage cohorts are missing women who married at younger ages. We dropped the women who were married prior to 1970 to reduce this truncation. We also use marriage cohort, rather than birth cohort, because it is a better approximation of a period measure and is subject to less truncation. However, we present national level results for both birth and marital cohorts in an appendix.

Connections among Marital Behaviors

Before examining trends over time, we first investigate the connections between spouse choice and the other three marital behaviors. As described above, while arranged marriage is often conceptualized as spouse choice, it is connected to caste endogamy, consanguineous marriage (in some contexts), and interaction prior to marriage. If these behaviors are tightly connected, a change in one behavior would inevitably result in a corresponding change in another. Conversely, if they are only loosely related, then changes in one may lead to little or no change in another. Thus, understanding the connections among the marital behaviors informs understanding of marital trends.

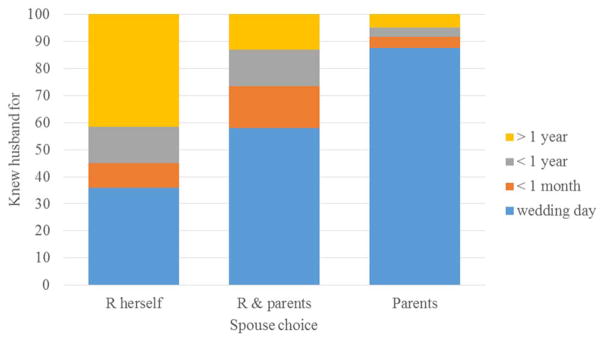

The distribution of spouse choice by the length of time women were acquainted with their husbands prior to marriage appears in Figure 1. As expected, women with more choice were acquainted with their husbands for longer periods of time. 42% of women who chose on their own met their husbands more than a year before marriage. In contrast, only 13% of women who chose jointly with their parents and 5% of women whose parents chose met their husbands more than a year prior to marriage. There are also striking differences between women who selected jointly with their parents and those who had no say in the intermediate categories. 88% of women whose parents alone chose met their husbands only on their wedding day, while 58% of women who chose jointly did so. Further, even over a third of women who chose by themselves only met on their wedding day. Thus, little to no interaction with husbands prior to marriage appears to be common among all women.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of length of acquaintanceship by spouse choice

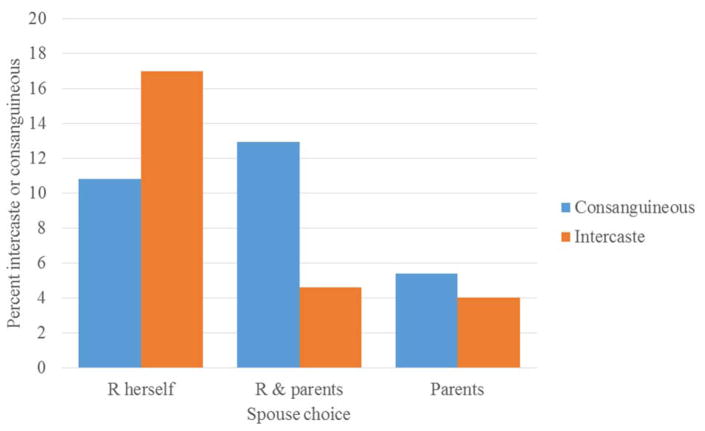

The distribution of intercaste and consanguineous marriage by spouse choice appears in Figure 2. Spouse choice is closely connected to caste endogamy with self-choice marriages standing out markedly from the other two categories. 17% of self-chosen marriages are intercaste, while less than 5% of marriages in which parents were involved are intercaste. Thus, as expected, parents are much more likely than their daughters to follow the custom of caste endogamy when selecting husbands. Women may also be less likely to approach their parents for approval of a potential marriage when they have an intercaste partner.

FIGURE 2.

Distributions of intercaste and consanguineous marriage by spouse choice

Consanguineous marriage, on the other hand, does not show the expected pattern. We expected consanguineous marriage to be more common when parents chose husbands. However, women who chose husbands jointly with their parents are the most likely to be related to their husbands at 13% (Figure 2). Only 5% of women whose parents chose and 11% of women who chose husbands by themselves are related to their husbands by blood. Thus, marriages in which women chose by themselves are more likely to be consanguineous than marriages in which parents alone selected the husband. We also examined whether the expected connection between spouse choice and consanguineous marriage did appear in the South, the only region where consanguineous marriage is customary. Even in the South, however, we did not find the expected pattern.

National Trends

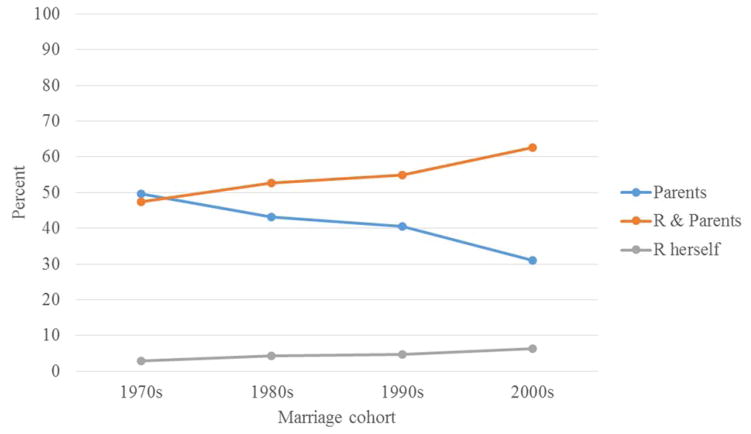

Next, we use marriage cohort to examine national trends in the four marital behaviors. National trends in spouse choice appear in Figure 3. Overall, there is a striking decline in parents alone choosing husbands for their daughters. The percent of marriages in which parents alone chose husbands fell from half in the 1970s to one-third in the 2000s. At the other extreme, self-choice marriages doubled from 3% in the 1970s to 6% in the 2000s, but remained rare in absolute terms. Instead of women choosing husbands on their own, the increasingly dominant pattern was for parents and daughters to both be involved in the selection. In the 1970s, 47% of women chose their husband jointly with their parents. Thus, at the beginning of the period, marriages in which parents alone chose outnumbered those in which women and their parents chose together. By the end of the period, however, joint selection was dominant, comprising two-thirds of marriages and outnumbering marriages in which parents alone chose by two to one.

FIGURE 3.

Spouse choice by marriage cohort

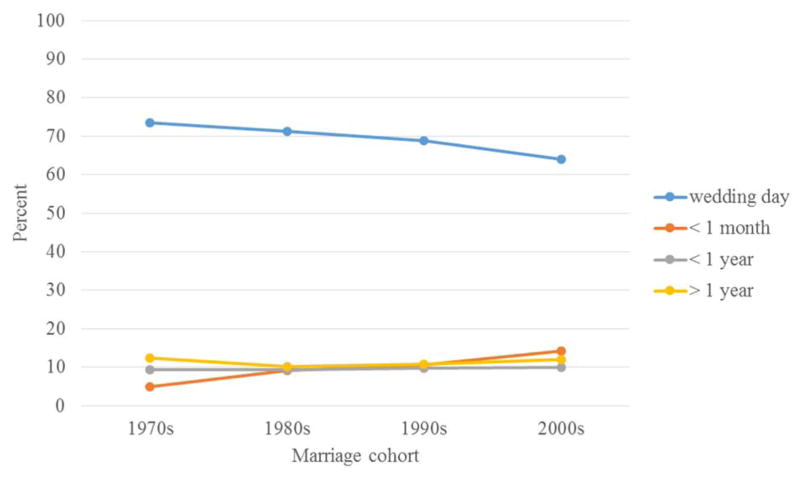

The trend in the length of time spouses knew each other prior to marriage appears in Figure 4. As expected, women did know their husbands for longer periods in the more recent cohorts, but the extent of change is modest. The percent of marriages in which women met their husbands only on their wedding day declined by 10 percentage points from 74% in the 1970s to 64% in the 2000s. Thus, even in the most recent cohort, the majority of women had little to no interaction with their husbands before marriage. Further, there was no increase in women knowing their spouses for long periods of time. The percentage of women who met their husband more than a year before marriage remained stable at 10–12% across cohorts. Similarly, the percentage who knew their husbands less than a year, but more than a month, remained stable at 9–10%. The only category that increased over time is meeting husbands less than a month before marriage, which rose from 5% in the 1970s to 14% in the 2000s. Overall, there was movement from meeting on the wedding day itself to meeting a few days or weeks before the wedding, but lengthy acquaintanceships remained rare.

FIGURE 4.

Length of acquaintanceship by marriage cohort

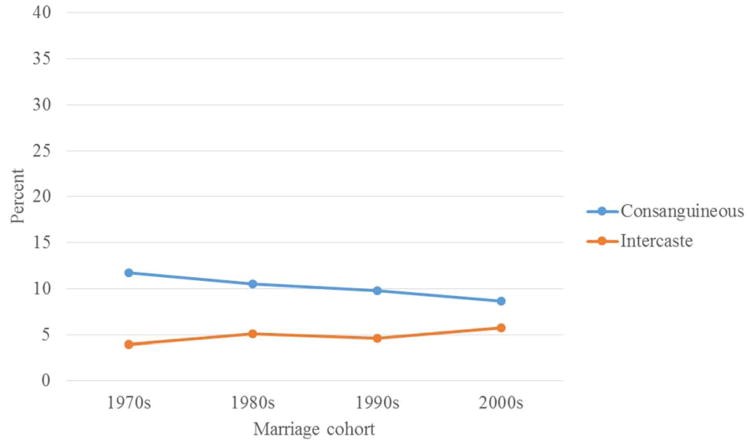

Trends in consanguineous and intercaste marriage also show changes in the expected directions (Figure 5). Consanguineous marriage declined by almost a third, from 12% in the 1970s to 9% in the 2000s. Conversely, intercaste marriage increased by nearly half, rising from 4% in the 1970s to 6% in the 2000s. However, like self-choice marriage, intercaste marriage shows a large relative change, but remained rare in absolute terms. Further, unlike consanguineous marriage, the trend in intercaste marriage was not constant throughout the period. Rather than consistently increasing, intercaste marriage held steady at 5% in 1980 and 1990.

FIGURE 5.

Consanguineous and intercaste marriage by marriage cohort

Regional Trends

India is a large and diverse country with variation in family behaviors and kinship systems across regions. Thus, understanding Indian marital trends requires going beyond the national level. Geographically, the most notable difference is the divide between the North and South (Dyson and Moore 1983; Karve 1965; Kolenda 1987). As noted above, consanguineous marriage is only customary in the South, while exogamy is customary in the North. Further, in the North, sexual purity and the seclusion of women are more highly valued and practiced and the custom of arranged marriage is customarily stronger (Jones 2010). The Northeast also differs markedly from the rest of India, but receives little attention due to its small population and peripheral location. The Northeast is inhabited by ethnic groups who have much in common with neighboring populations in Bhutan, Myanmar, and Southwestern China and the custom of arranged marriage is generally weaker there. It should also be noted, however, that there are indications that kinship practices have changed in recent decades and regional differences are breaking down (Rahman and Rao 2004). Moreover, even when famously dividing India into North and South demographic regimes, Dyson and Moore (1983) were not sure where the borders were located.

To evaluate the extent of regional diversity, we examine marital trends across six regions. We divide states and union territories into North (n=14,783), Central (n=7,261), East (n=4,906), West (n=6,176), South (n=10,810), and Northeast (n=2,074). The North includes Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkand. Central includes Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh. East comprises West Bengal and Orissa, while the West includes Gujarat, Goa, and Maharashtra. South includes Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Finally, the Northeast includes Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, Meghalaya, and Assam.

A limitation of this analysis is that a few marriages may be categorized into the wrong region. Ideally, marriages should be matched to the region where the wedding took place or where the bride and/or groom were living at the time of marriage. However, we only observe the region in which the woman resided at the time of the survey, which is several years after marriage in many cases. Thus, the marriages of women who migrated across regions in the period between marriage and the survey are misclassified. We expect that this limitation should only present a slight error. While it is common for women to migrate for marriage, it is rare for them to migrate across regions after marriage (Rao and Finnoff 2015).

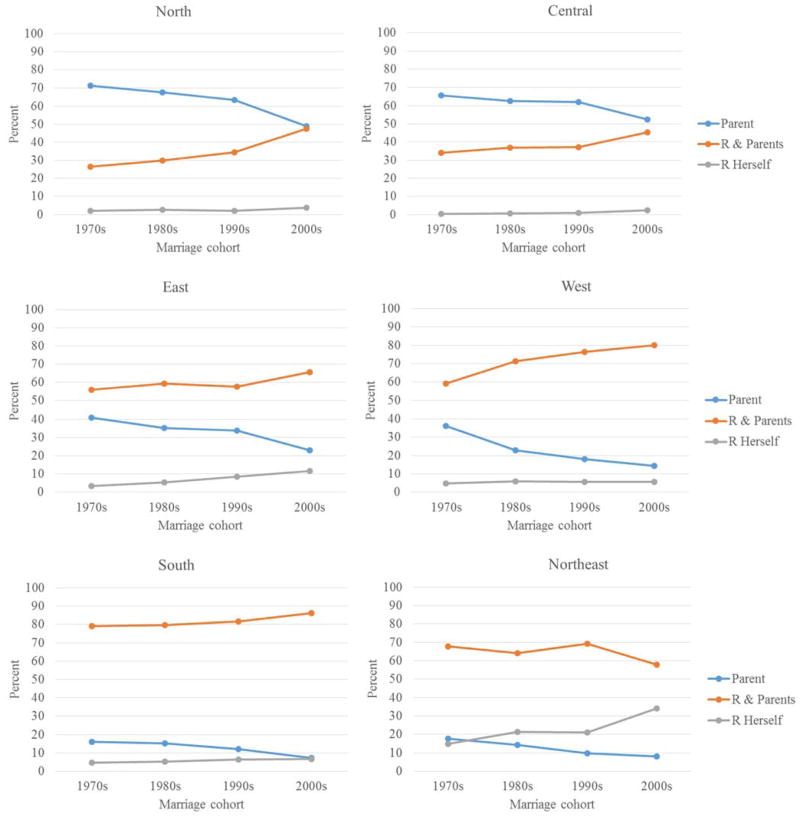

Spouse choice

Every region shows a decline in parental control, but the extent of decline, as well as initial levels, differs dramatically across regions (Figure 6). The North and Central regions stand out with high and declining parental control. Marriages in which parents alone chose comprise a dominant majority in the 1970s in these regions, at 72% and 66% respectively, and retain their majority status until the 2000s. Among the most recent cohort, choosing jointly rises substantially to roughly half of marriages, edging out those that are fully parentally controlled in the Central region and reaching parity in the North. Self-chosen marriages are also extremely rare. Self-choice marriages comprising less than 4% of marriages across the period, although there is a small rise in the 2000s.

FIGURE 6.

Spouse choice by marriage cohort and region

The South and Northeast have substantially lower levels of parental control and greater continuity over time, but still show substantial change. In these regions, marriages in which only parents only chose the husband comprised just over 15% of the total in the 1970s and fell by roughly half by the 2000s. Marriages in which parents and daughters choose jointly were the dominant majority throughout the period, comprising over 80% of marriages in the South and 60–70% of marriages in the Northeast. There is a striking difference in self-choice marriages between the South and Northeast however. In the South, self-choice marriages match the national trend of a large relative change, but consistently low absolute levels. The Northeast, on the other hand, stands out as the only region with a sizeable percentage of self-choice marriages, rising from 15% in the 1970s to 34% in the 2000s.

The trends for the East and West are in-between these extremes. Like the South, jointly chosen marriages comprise the majority across cohorts in these regions. The level of self-choice marriages is also similar overall to that of the South. However, the East shows a comparatively dramatic rise in self-choice marriages, tripling from 3% to 12%, while the West is stable at around 5%.

Other Marriage Behaviors

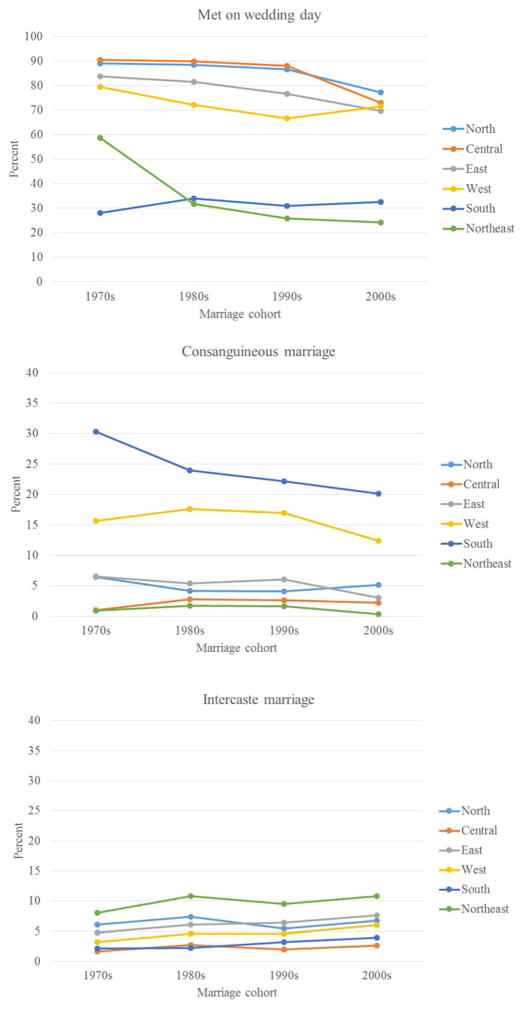

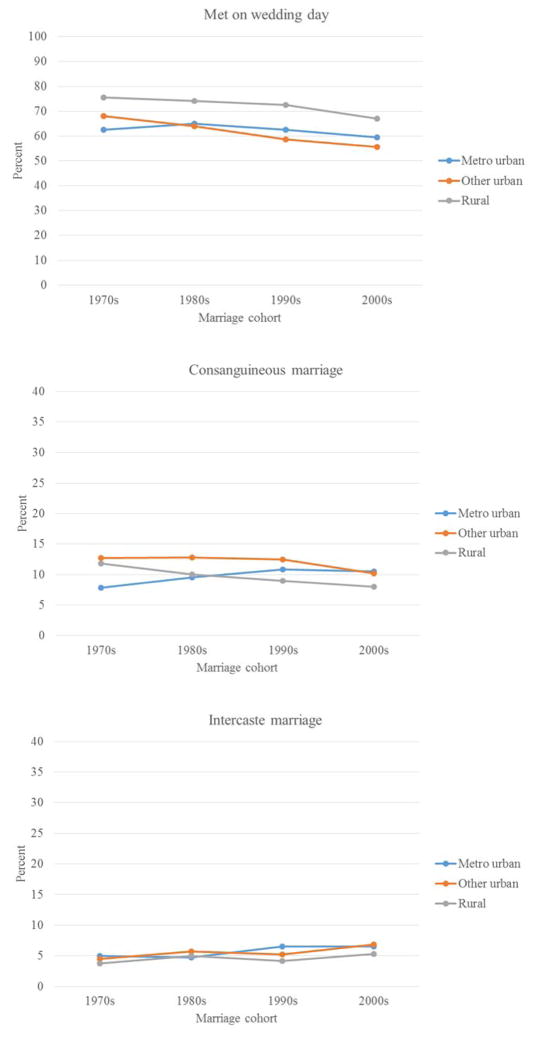

Next, we examine regional variation in the length of acquaintanceship. To ease comparison across regions, we examine only one indicator: the percent of women who reported meeting their husbands on their wedding day (Figure 7). We chose this category because it represents an extreme end of the spectrum and includes the majority of women at the national level. We should again note, however, that even if they met on their wedding day, women may still have communicated with and seen their husbands before marriage.

FIGURE 7.

Length of acquaintanceship, consanguineous marriage, and intercaste marriage by marriage cohort and region

The trends in acquaintanceship show greater homogeneity across regions than spouse choice. The North, Central, East, and West regions all show modest declines in meeting on the wedding day. Specifically, the percent of marriages in which the couple met on their wedding day fell from 80–90% in the 1970s to 70–80% in the 2000s. The South and Northeast stand out with markedly different trends. The Northeast shows a steep decline in meeting on the wedding day, falling from 59% in the 1970s to 24% in the 2000s. In the South, meeting on the wedding day was stable at around a third of marriages.

In keeping with the regional differences in the kinship systems, consanguineous marriage was rare and stable in most regions, but not the South and West (Figure 7). Across the period, marriages between blood relatives range from 1–6% of all marriages in the North, Central, East, and Northeast regions. By contrast, the South and West had high and declining levels of consanguineous marriage. However, these regional trends mask further heterogeneity at the state level. Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Maharshtra, and Goa experienced large declines in consanguineous marriage, but still had much higher levels than the rest of India even in the 2000s. The remaining Southern and Western states, namely Kerala and Gujarat, match the national trends with rare and stable levels of consanguineous marriage.

Intercaste marriage is the only behavior without any clear regional outliers, although the Northeast comes close (Figure 7). The trends, as well as the levels, are similar across regions and dovetail relatively closely with the national trend. At the start of the period, in the 1970s, intercaste marriage varies from a low of 2% in the Central region to a high of 8% in the Northeast. By the 2000s, these levels have only increased to 3% in the Central region and 11% in the Northeast. The Northeast’s relatively high level of intercaste marriage is in keeping with its high level of self-choice marriage. The generally low levels of intercaste marriage are also consistent with low levels of self-choice marriages across regions.

Trends by Urban Residence

Next, we investigate marital trends by urban residence. Both modernization theory and developmental idealism theory suggest that arranged marriage should decline first, or be less common, in urban areas. Modernization theory views arranged marriage as structurally incompatible with urban life, while developmental idealism theory suggests that urban residents encounter and adopt developmental idealism before rural residents.

We divide women into three categories by their place of residence at the time of survey: metro urban (n=3,944), other urban (n=12,372), and rural (n=26,694). Metro urban refers to the six largest metropolitan areas in India, comprising Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Bangalore, and Hyderabad. Since place of residence is measured at the time of survey, this categorization does include some error. As noted above in reference to region, marriages of women who changed their place of residence between the time of marriage and the survey are misclassified.

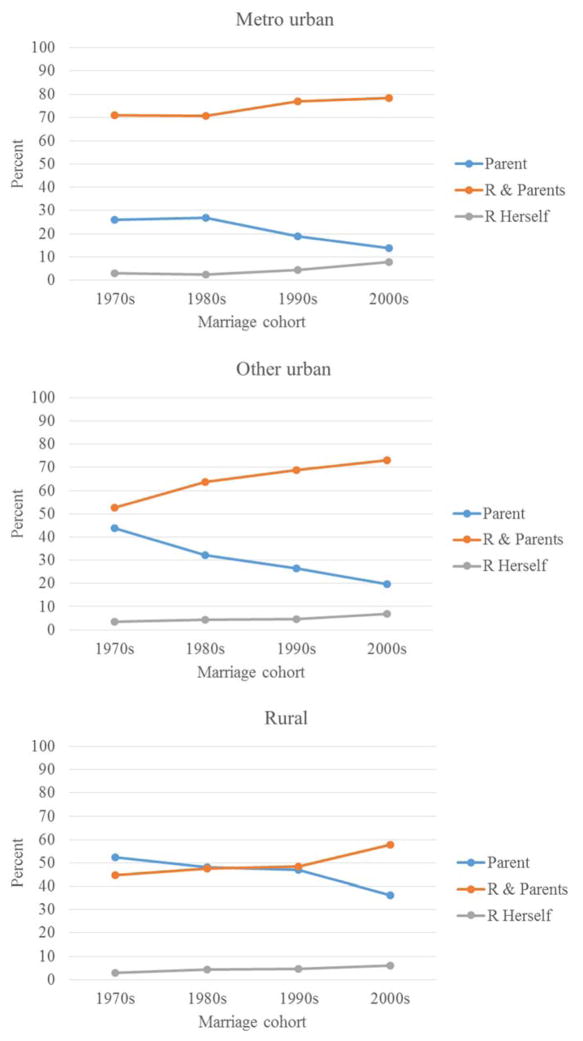

Spouse choice

Parents alone choosing husbands uniformly declined for urban and rural residents, but the levels differed substantially (Figure 8). As predicted by theory, parents only choosing husbands was highest among rural residents (53–36%), lowest among metro urban residents (26–14%), and in-between these extremes for other urban residents (44–20%). Further, women and their parents jointly choosing husbands show the inverse pattern. Choosing jointly uniformly rose across all places of residence, but was at a substantially higher level among metro urban and, to a lesser extent, other urban residents. Contrary to expectations, however, both the trends and levels of self-choice marriages did not differ by place of residence. Metro urban, other urban, and rural residents all match the national trend with the percent of marriages in which women alone chose their husbands rising from around 3% in the 1970s to 6–8% in the 2000s.

FIGURE 8.

Spouse choice by marriage cohort and urban residence

Other Marriage Behaviors

The trends in meeting on the wedding day are broadly similar across places of residence, but there were notable, albeit modest, differences (Figure 9). Across the period, rural residents were slightly more likely to meet their husband on their wedding day, than urban residents. Both rural and other urban residents also show slight declines over time. Meeting on their wedding day declined from 76% to 67% among rural residents, while it declined from 68% to 56% among other urban residents. Metro urban residents were stable with roughly 60% of women from all marital cohorts meeting husbands on their wedding day.

FIGURE 9.

Length of acquaintanceship, consanguineous marriage, and intercaste marriage by marriage cohort and urban residence

There are also modest differences in trends in consanguineous marriage (Figure 9). Rural residents show the national pattern of a slight decline in consanguineous marriage from 12% to 8%. Urban residents, on the other hand, are stable over time. Other urban residents hold at around 12% for most of the period, but decline slightly in the 2000s. Metro urban residents, show a slight increase in consanguineous marriage, from 8% in the 1970s to 11% in the 1990s and 2000s, but this difference is not statistically significant.

The trends in intercaste marriage are virtually identical across rural and urban residents (Figure 9). Metro urban, other urban, and rural residents all show the national pattern; intercaste marriage remains rare across the period, but does suggest slight increases from 4–5% in the 1970s to 5–7% in the 2000s. These rises are statistically significant for the rural and other urban residents, but not for the smaller metro urban sample.

Trends by Religion/Caste

Finally, we examine trends in marital behaviors by religion/caste. Specifically, we divide women into six groups: Upper Caste Hindus (n=10,344), Other Backward Castes (OBCs) (n=15,429), Dalits (n=9,462), Adivasis (n=3,635), Muslims (n=5,501), and other religions (n=1,639), which are composed largely of Christians, Sikhs, and Jains. The small number of women who are both Adivasi and Christian are placed in the Adivasi category. Adivasis are also known as Scheduled Tribes, while Dalits are also termed Scheduled Castes. Other Backward Castes, as well as Scheduled Tribes and Castes, are officially recognized by the Indian government as socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. We should emphasize that these categories contain multiple castes (jatis).

Ethnographic literature suggests that arranged marriage and accompanying practices are followed more closely by higher caste groups (Grover 2011; Saavala 2001). Lower caste groups tend to have looser marriage practices, including greater choice among young people and fewer restrictions on women’s sexuality. Ethnographic studies also indicate that Muslims prefer, or are at least less averse towards, marriages among relatives and within villages (Jeffery and Jeffery 1997; Kaur and Palriwala 2014).

Before describing trends by religion/caste, it is important to reflect on the extent to which these trends may be driven by an association with regional trends and vice versa. There are notable patterns in the distribution of religion/caste groups across regions. For example, Upper Caste Hindus and other religions are concentrated in the North, the Northeast has a relatively large population of Adivasis, and the South has a relatively large population of Other Backward Castes. For the most part, however, groups are spread across regions and there is not a strong overlap between region and religion/caste. For example, while 39% of Upper Caste Hindus in the sample reside in the North, only 27% of the sample from the North is comprised of Upper Castes. Similarly, while 29% of the sample from the Northeast are Adivasis, only 16% of the Adivasis in the sample reside in the Northeast. In turn, the associations between region and religion/caste are not strong enough for regional trends to markedly affect trends by religion/caste and vice versa. When we adjust for region, the bulk of the estimates for religion/caste differ by only a few hundredths and, at most, they differ by a couple percentage points. The reverse also holds; regional trends are consistent when adjusted for religion/caste.

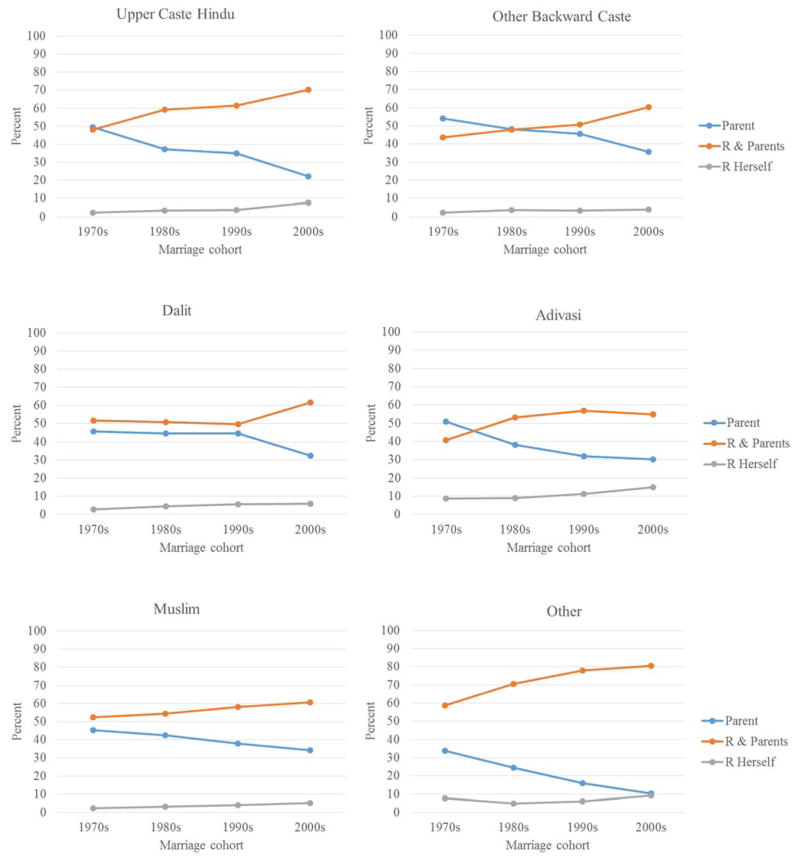

Spouse choice

Overall, the trends in spouse choice are similar across religion/caste groups. Every group shows a steady decline in parents alone choosing husbands and a corresponding rise in parents and daughters jointly choosing husbands (Figure 10). Every group, except other religions, also has a slow and steady rise in self-choice marriages. While change over time is relatively uniform, the levels are also similar. Jointly choosing husbands is not only increasing over time, but is the most common experience for all groups during most of the period. The only exception to this statement is the 1970s cohort for which parents only choosing is nearly as common as joint selection among Muslims and Dalits and parents only choosing is more or equally common among Upper Caste Hindus, Other Backward Castes, and Adivasis. Further, self-choice marriage is a distant third spouse choice category among all groups from the 1970s to the 1990s. In the 2000s, parents alone choosing declined so substantially that it was close to, or even at, the low level of self-choice marriages among Upper Caste Hindus, Advasis, and other religions.

FIGURE 10.

Spouse choice by marriage cohort and religion/caste

There are still important differences among religion/caste groups however. First, self-choice marriages are more common among Adivasis. Although the other religion category is somewhat of an exception with a high level of self-choice marriages in the 1970s. The other religion group also shows consistently high levels of joint choice and correspondingly lower levels of parents alone choosing spouses. However, the pace of change over time among other religions is comparable to other groups. Upper Caste Hindus also show higher levels of joint choice, but they do not stand out as much as other religions. Thus, in contrast to the ethnographic literature, parents alone choosing husbands is more common among Dalits and Other Backward Castes than it is among Upper Caste Hindus.

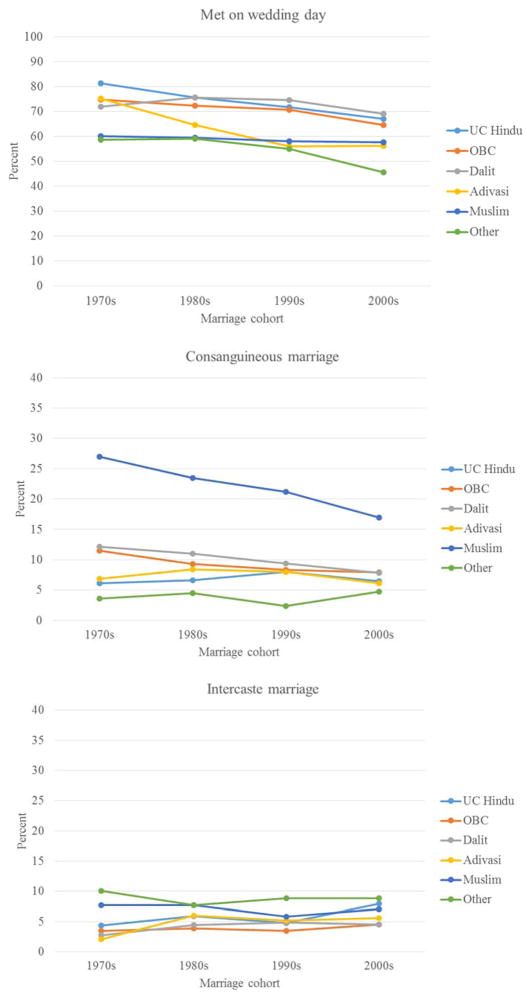

Other Marriage Behaviors

The trends in length of acquaintance are also similar among religion/caste groups (Figure 11). For Upper Caste Hindus, Other Backward Castes, Adivasis, and other religions, meeting on the wedding day declined by 10 to 18 percentage points from 59–81% in the 1970s to 46–67% in the 2000s. Muslims and Dalits, on the other hand, are stable over time at just under two-thirds and nearly three-quarters respectively. Overall, the majority of women in all groups report meeting their husbands on their wedding day throughout the period. (The only exception is the other religion group, which dips just below half in the 2000s.)

FIGURE 11.

Length of acquaintanceship, consanguineous marriage, and intercaste marriage by marriage cohort and religion/caste

Consanguineous marriage has a clear outlier among religious/caste groups (Figure 11). As expected, Muslims have substantially higher levels of consanguineous marriage and experience a steady decline over time. The proportion of Muslim marriages that are consanguineous drops from just over a quarter in the 1970s to 17% by the 2000s. Even in the 2000s though, the level of consanguineous marriage among Muslims is roughly twice that of other groups. There is also notable variation among the other groups. Like Muslims, Dalits and Other Backward Castes show steady declines in consanguineous marriage, but they start and end at much lower levels. Adivasis, Upper Caste Hindus, and the other religions, on the other hand, show low and stable levels of consanguineous marriage.

Intercaste marriage is rare and relatively stable over time among all groups (Figure 11). In the 1970s, intercaste marriage ranges from 2% among Adivasis to 10% among other religious groups. In the 2000s, this range tightened to a low of 5% among Other Backward Castes to a high of 9% among the other religions. The proportion of marriages that are intercaste is significantly higher in the 2000s than it is in the 1970s for Upper Caste Hindus, Dalits, and Adivasis. However, even these statistically significant increases in intercaste marriage are small in size.

Discussion and Conclusion

We motivated this article by noting that the extent of marital change in India, as well as many other countries, is not well established. Theories of family change suggest that arranged marriage should decline in favor of Western marriage practices and previous studies do show such declines in other Asian contexts. In India, ethnographic studies suggest that marital change is afoot, yet other evidence points to little or even no change. Thus, an assessment of the extent and nature of marital change across India is needed. Having completed such an analysis, our answer to the titular question – is arranged marriage declining – is both yes and no.

We conclude that the practice of arranged marriage is shifting, rather than declining. Marriage behaviors did change in predicted directions from the 1970s to the 2000s. Young women became increasingly active in choosing their own husbands, spouses meeting before the wedding day became more common, consanguineous marriage declined, and intercaste marriage rose. However, the size of many of these changes is modest and substantial majorities of recent marriages still show the hallmarks of arranged marriage. Arranged marriage is clearly not headed towards obsolescence any time soon.

Further, the nature of the changes in spouse choice deviates profoundly from the prediction. Rather than displacing their parents, young women joined their parents in working together to choose husbands. While self-choice marriages increased over time, they are still rare, comprising less than a tenth of all marriages in the 2000s. Moreover, even in the 2000s, parents alone choosing husbands for their daughters was more than twice as common as daughters choosing by themselves. Overall, while most parents have lost complete control over marriage, the intergenerational nature of marriage remains intact.

Rather than unilateral movement towards Western practices, these trends point to a hybridization of Western and Indian practices. In India, the colloquial opposite of an arranged marriage is a “love marriage,” which refers to the Western practice of young people choosing their own spouses on the basis of love, attraction, or interpersonal compatibility. We do not have data on the extent to which women felt such emotions prior to marriage, but our results suggest that it is rare and directed along customary lines (cf. De Munck 1996; Harkness and Khaled 2014). While intercaste marriage is more common among self-choice marriages, still less than a fifth of self-choice marriages are intercaste. Thus, it appears that, like their parents, most women follow the rules of caste endogamy. Even more strikingly, many women who choose by themselves still report meeting their husband on the wedding day or slightly before. Thus, self-arranged or jointly-arranged marriage seem more accurate than the commonly used term “love marriage” when characterizing these marriages.

Many of these national trends held across India. All regions show declines of parental control over spouse choice and, apart from the South, modest increases in spouses meeting prior to marriage. Further, all regions experienced only slight increases or no change at all in intercaste marriage. However, our findings also reinforce the value of going beyond the national level. Trends for the South, as well as the Northeast, depart markedly from some national trends. The South is the only region to experience a substantial decline in consanguineous marriages from previously high levels and the decline of parental control was much more muted. The Northeast stands out as the only region in which self-choice marriages rose to substantial levels. In keeping with high levels of self-choice marriages, intercaste marriage was also more common in the Northeast and, like the South, meeting only on the wedding day was not common as it was elsewhere. Thus, we conclude that regional differences, in particular the well-known North/South regimes and lesser known Northeastern exception, remain important demographic divides. The findings also support Jones’ (2010) identification of North India as the bastion of arranged marriage.

Differences by urban residence were far more muted. Women living in urban areas, in particular those residing in the largest cities, were substantially more likely to choose husbands jointly with their parents. In rural areas, on the other hand, parents were much more likely to choose husbands without their daughters input. However, self-choice marriages were uniformly rare across urban and rural areas. Further, trends in the length of acquaintanceship prior to marriage, consanguineous marriage, and intercaste marriage showed only slight, or even no, differences between rural and urban residents

Variation among religious/caste groups was also less than that found among regions, but there were meaningful departures from national trends. The most striking departure was found for Muslims, who like the South, show a marked decline in consanguineous marriage from previously high levels. Adivasis also stood out; like the Northeast, Adivasis had a comparatively high level and more substantial rise in self-choice marriages. Some expected differences among castes did not materialize however. As noted above, the ethnographic literature suggests that lower castes are less observant of arranged marriage. Apart from the exception of high levels of self-choice marriage among Adivasis, however, Dalits, Adivasis, and Other Backward Castes did not differ substantially and systematically from Upper Castes.

These trends have important implications for global theories of family change, which predict that arranged marriage declines in favor of Western marriage practices. Our results suggest that this prediction was only partially accurate for India. It is likely that marriage will continue to change further in the future, but past trends suggest that marital change in India is at least slower, if not qualitatively different, from other Asian contexts for which we have data. Proponents of modernization theory might suggest that India has experienced less economic change than other contexts. However, the similarities across urban and rural residents suggest that modernization theory will not adequately explain India’s trends. We speculate that developmental idealism theory may fare better. Like other contexts, the values and beliefs of developmental idealism seem to be well-known in India, but their power to change marital behavior may be muted by powerful, counter-vailing values and beliefs. In particular, the incompatibilities of developmental idealism with gendered schemas about marriage for women may be a formidable barrier in India (Allendorf forthcoming; Desai and Andrist 2010). The power of India’s caste system, and its need for caste endogamy, may be another barrier (Caldwell et al. 1998). These suggestions remain speculative, however. Future research should rigorously examine why India experienced the trends identified here.

Further research is also needed to better establish the extent and nature of marital change within and beyond India. In India itself, future research should examine men’s experiences. While it is highly likely that men have greater choice over their spouses than women, survey data on men’s experiences is needed to test that claim. Data on men is also needed to establish the extent of change in spouse choice among the population as a whole and identify whether men and women’s reports of couple-level behaviors, including consanguineous and intercaste marriage, provide comparable estimates. More importantly, similar studies are needed for other parts of the world. Establishing the extent and nature of marital change across regions and globally depends on having nationally representative data from more than a handful of countries. Luckily, given the centrality of marriage to individuals’ lives, retrospective reports of marriage behavior are likely to be very high quality. Thus, even a single, cross-sectional survey can provide valuable insights by drawing on marriage cohorts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Arland Thornton for his helpful comments and Reeve Vanneman for providing access to data from the Indian Human Development Survey.

APPENDIX

TABLE 1.

Change in Marriage Behaviors by Marriage Cohort (N=46,010)

| N | Intercaste

|

Spouse Choice

|

Knew Husband For

|

Consanguineous1

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | R herself | R & Parents | Parents | wedding day | < 1 month | < 1 year | > 1 year | Yes | ||

| Marriage | ||||||||||

| Cohort | ||||||||||

| 1970s | 4,884 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 47.4 | 49.6 | 73.5 | 4.9 | 9.3 | 12.3 | 11.8 |

| 1980s | 13,061 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 52.6 | 43.2 | 71.4 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 10.2 | 10.5 |

| 1990s | 14,162 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 54.8 | 40.6 | 68.8 | 10.6 | 9.8 | 10.8 | 9.8 |

| 2000s | 13,903 | 5.7 | 6.4 | 62.6 | 31.0 | 63.9 | 14.2 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 8.6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Absolute Change (1970s to 2000s) | 1.8 | 3.4 | 15.2 | −18.6 | −9.6 | 9.3 | 0.6 | −0.3 | −3.1 | |

| Relative Change (1970s to 2000s) | 45.4 | 114.5 | 32.2 | −37.6 | −13.0 | 190.2 | 6.6 | −2.4 | −26.6 | |

Number of cases for consanguineous marriage is 44,752 (4,837; 12,851; 13,870; 13,194 for 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s respectively).

TABLE 2.

Change in Marriage Behaviors by Birth Cohorts (N=46,010)

| N | Intercaste

|

Spouse Choice

|

Knew Husband For

|

Consanguineous1

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | R herself | R & Parents | Parents | wedding day | < 1 month | < 1 year | > 1 year | Yes | ||

| Birth Cohort | ||||||||||

| 1950s | 2,245 | 5.1 | 3.4 | 54.2 | 42.4 | 69.1 | 6.8 | 13.1 | 11.0 | 10.7 |

| 1960s | 11,892 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 53.7 | 41.9 | 70.4 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 11.1 | 10.7 |

| 1970s | 15,536 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 55.5 | 39.8 | 68.7 | 10.6 | 10.0 | 10.7 | 9.7 |

| 1980s | 13,700 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 57.4 | 37.7 | 68.0 | 11.5 | 9.1 | 11.4 | 9.5 |

| 1990s | 2,637 | 5.6 | 8.8 | 59.1 | 32.1 | 62.1 | 16.3 | 8.0 | 13.7 | 8.6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Absolute Change (1950s to 1990s) | 0.5 | 5.4 | 4.9 | −10.3 | −7.0 | 9.5 | −5.2 | 2.7 | −2.1 | |

| Relative Change (1950s to 1990s) | 9.0 | 157.9 | 9.1 | −24.3 | −10.1 | 138.3 | −39.3 | 24.5 | −19.2 | |

Number of cases for consanguineous marriage is 44,752 (2,213; 11,710; 15,205; 13,197; 2,427 for 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s respectively).

Contributor Information

Keera Allendorf, Department of Sociology, Indiana University, 1020 E. Kirkwood Ave Bloomington, IN 47405 (812)855-1540.

Roshan K. Pandian, Department of Sociology, Indiana University

References

- Adams Bert N. Themes and Threads of Family Theories: A Brief History. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2010;41(4):499–505. [Google Scholar]

- Aengst Jennifer. Adolescent Movements: Dating, Elopements, and Youth Policing in Ladakh, India. Ethnos. 2014;79(5):630–649. [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf Keera. Schemas of Marital Change: From Arranged Marriages to Eloping for Love. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75(2):453–469. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf Keera. Conflict and Compatibility? Developmental Idealism and Gendered Differences in Marital Choice. Journal of Marriage and Family forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Allendorf Keera, Thornton Arland. Caste and Choice: The Influence of Developmental Idealism on Marriage Behavior. American Journal of Sociology. 2015;121(1):243–287. doi: 10.1086/681968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axinn William G, Ghimire Dirgha J, Barber Jennifer S. International Family Change: Ideational Perspectives. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. The Influence of Ideational Dimensions of Social Change on Family Formation in Nepal,” in R. Jayakody, A. Thornton, and W.G. Axinn (eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Beteille Andre. Castes: Old and New. London: Asia Publishing House; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John, Zimmer Zachary. Living Arrangements of Older Adults in the Developing World: An Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey Household Surveys. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(3):S145–S157. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.s145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant John. Theories of Fertility Decline and the Evidence from Development Indicators. Population and Development Review. 2007;33(1):101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Buttenheim Alison M, Nobles Jenna. Ethnic Diversity, Traditional Norms, and Marriage Behaviour in Indonesia. Population Studies-a Journal of Demography. 2009;63(3):277–294. doi: 10.1080/00324720903137224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell Bruce. Marriage in Sri Lanka: A Century of Change. New Delhi: Hindustan Publishing Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John C, Caldwell Pat, Caldwell Bruce K, Pieris Indrani. The Construction of Adolescence in a Changing World: Implications for Sexuality, Reproduction, and Marriage. Studies in Family Planning. 1998;29(2):137–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John C, Reddy PH, Caldwell Pat. The Causes of Demographic Change in Rural South India - a Micro Approach. Population and Development Review. 1982;8(4):689–727. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell John C, Reddy PH, Caldwell Pat. The Causes of Marriage Change in South India. Population Studies-a Journal of Demography. 1983;37(3):343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J. Goode’s World Revolution and Family Patterns: A Reconsideration at Fifty Years. Population and Development Review. 2012;38(4):577–607. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhry Prem. Contentious Marriages, Eloping Couples: Gender, Caste, and Patriarchy in Northern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cole Jennifer, Thomas Lynn M. Love in Africa. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Munck Victor C. Love and Marriage in a Sri Lankan Muslim Community: Toward a Reevaluation of Dravidian Marriage Practices. American Ethnologist. 1996;23(4):698–716. [Google Scholar]

- Desai Sonalde, Andrist Lester. Gender Scripts and Age at Marriage in India. Demography. 2010;47(3):667–687. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai Sonalde, Amaresh Dubey BL, Joshi Mitali Sen, Shariff Abusaleh, Vanneman Reeve. Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS), 2005. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Desai Sonalde, Vanneman Reeve National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi. India Human Development Survey-II (IHDS-II), 2011–12. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer Rachel. All You Want Is Money, All You Need Is Love: Sexuality and Romance in Modern India. London: Cassell; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson Tim, Moore Mick. On Kinship Structure, Female Autonomy, and Demographic Behavior in India. Population and Development Review. 1983;9(1):35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CJ, Narasimhan Haripriya. Companionate Marriage in India: The Changing Marriage System in a Middle-Class Brahman Subcaste. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 2008;14(4):736–754. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire Dirgha J, Axinn William G, Yabiku Scott T, Thornton Arland. Social Change, Premarital Nonfamily Experience, and Spouse Choice in an Arranged Marriage Society. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;111(4):1181–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Goode William J. World Revolution and Family Patterns. London: Free Press of Glencoe, Collier-MacMillan Ltd; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Grover Shalini. Marriage, Love, Caste, and Kinship Support: Lived Experiences of the Urban Poor in India. New Delhi: Social Science Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness Geoff, Khaled Rana. Modern Traditionalism: Consanguineous Marriage in Qatar. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2014;76(3):587–603. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch Jennifer S. A Courtship after Marriage: Sexuality and Love in Mexican Transnational Families. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch Jennifer S, Wardlow Holly. Modern Love: The Anthropology of Romantic Courtship and Companionate Marriage. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery Roger, Jeffery Patricia. Population, Gender, and Politics: Demographic Change in Rural North India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Gavin W. Changing Marriage Patterns in Asia. Singapore: Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore Working Paper; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Gavin W. Marriage and Divorce in Isliam South-East Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Karve Irawati. Kinship Organization in India. Bombay: Asia Publishing House; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur Ravinder, Palriwala Rajni., editors. Marrying in South Asia: Shifting Concepts, Changing Practices in a Globalizing World. Hyderabad: Orient Black Swan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kolenda Pauline. Regional Differences in Family Structure in India. Jaipur: Rawat Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane Alan. Marriage and Love in England: Modes of Reproduction 1300–1840. Oxford: Blackwell; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra Anju. Gender and Changing Generational Relations - Spouse Choice in Indonesia. Demography. 1991;28(4):549–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra Anju. Gender and the Timing of Marriage: Rural-Urban Differences in Java. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59(2):434–450. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden Magnus. Love and Elopement in Northern Pakistan. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 2007;13(1):91–108. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald Peter. Convergence or Compromise in Historial Family Change? In: Berquo Elza, Xenos Peter., editors. Family Systems and Cultural Change. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Meekers Dominique. Freedom of Partner Choice in Togo. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1995;26(2):163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Mody P. The Intimate State: Love-Marriage and the Law in Delhi. Delhi: Routledge India; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nations U. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nedoluzhko L, Agadjanian V. Between Tradition and Modernity: Marriage Dynamics in Kyrgyzstan. Demography. 2015;52:861–882. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netting Nancy S. Marital Ideoscapes in 21st-Century India: Creative Combinations of Love and Responsibility. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;20(10):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Niranjan S, Nair Sarita, Roy TK. A Socio-Demographic Analysis of the Size and Structure of the Family in India. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2005;36(4):623–651. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Jose Antonio. A Characterization of World Union Patterns at the National and Regional Level. Population Research and Policy Review. 2014;33(2):161–188. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad Gitanjali. The Great Indian Family: New Roles, Old Responsibilities. New Delhi: Penguin Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Lupin, Rao Vijayendra. The Determinants of Gender Equity in India: Examining Dyson and Moore’s Thesis with New Data. Population and Development Review. 2004;30(2):239–268. [Google Scholar]

- Rao Smriti, Finnoff Kade. Marriage Migration and Inequality in India, 1983–2008. Population and Development Review. 2015;41(3):485–505. [Google Scholar]

- Raymo James M, Park Hyunjoon, Xie Yu, Yeung Wei-jun Jean. Marriage and Family in East Asia: Continuity and Change. Annual Review of Sociology. 2015;41:471–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebhun LA. The Heart Is Unknown Country: Love in the Changing Economy of Northeast Brazil. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Retherford Robert D, Ogawa Naohiro. Japan’s Baby Bust: Causes, Implications, and Policy Responses. In: Harris Fred R., editor. The Baby Bust: Who Will Do the Work? Who Will Pay the Taxes? Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles Steven. Reconsidering the Northwest European Family System: Living Arrangements of the Aged in Comparative Historical Perspective. Population and Development Review. 2009;35(2):249–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavala Minna. Fertility and Familial Power Relations: Procreation in South India. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Still Clarinda. Spoiled Brides and the Fear of Education: Honour and Social Mobility among Dalits in South India. Modern Asian Studies. 2011;45(05):1119–1146. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland. Truncation Bias. In: Thornton Arland, Lin Hui-Sheng., editors. Social Change and the Family in Taiwan. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland. The Developmental Paradigm, Reading History Sideways, and Family Change. Demography. 2001;38(4):449–465. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland. Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Impact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland. Historical and Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Marriage. In: Elizabeth Peters H, Kamp Dush Claire M, editors. Marriage and Family: Perspectives and Complexities. New York: Columbia University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland, Chang JS, Lin HS. From Arranged Marriage toward Love Match. In: Thornton A, Lin H-S, editors. Social Change and the Family in Taiwan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trautman Thomas R. Dravidian Kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Uberoi Patricia. Freedom and Destiny: Gender, Family, and Popular Culture in India. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Xizohe, Whyte Martin King. Love Matches and Arranged Matches: A Chinese Replication. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52(3):709–722. [Google Scholar]

- Yan Yunxiang. Private Life under Socialism: Love, Intimacy, and Family Change in a Chinese Village. Standford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zang Xiaowei. Gender and Ethnic Variation in Arranged Marriages in a Chinese City. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;29(5):615–638. [Google Scholar]