Abstract

RNA enzymes have remarkably diverse biological roles despite having limited chemical diversity. Protein enzymes enhance their reactivity through recruitment of cofactors. The naturally occurring glmS ribozyme uses the glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) organic cofactor for phosphodiester bond cleavage. Prior structural and biochemical studies implicated GlcN6P as the general acid. Here we describe new catalytic roles for GlcN6P through experiments and calculations. Large stereospecific normal thio effects and lack of metal ion rescue in the holoribozyme show that nucleobases and the cofactor play direct chemical roles and align the active site for self-cleavage. Large stereospecific inverse thio effects in the aporibozyme suggest that the GlcN6P cofactor disrupts an inhibitory interaction of the nucleophile. Strong metal ion rescue in the aporibozyme reveals this cofactor also provides electrostatic stabilization. Ribozyme organic cofactors thus perform myriad catalytic roles, allowing RNA to compensate for its limited functional diversity.

Enzymes catalyze diverse chemical reactions and utilize a variety of strategies to do so. RNA enzymes are known to employ at least four different catalytic strategies: in-line nucleophilic attack, neutralization of the non-bridging oxygens, deprotonation of the 2′OH nucleophile, and protonation of the 5′O leaving group1–3. Chief amongst these are general acid-base catalysis to facilitate proton transfer and electrostatic catalysis to stabilize charge build-up4. Protein enzymes frequently recruit exogenous species such as metal ions and small molecule cofactors to aid in chemical catalysis. RNA enzymes, or ribozymes, also recruit cofactors to aid in catalysis. For instance, the group I intron uses exogenous guanosine as the nucleophile in its self-excising mechanism5. Because it has only four similar nucleobases, RNA is much less chemically diverse than proteins. It is thus of keen interest to understand the diversity of catalytic roles cofactors might play in RNA.

Herein we study the mechanism of the glmS ribozyme. This ribozyme is comprised of four large pairings and is double pseudoknotted (Fig. 1a). The glmS ribozyme uses G33 as the putative base, with data suggesting that G33 may never fully deprotonate, may have an elevated pKa, or may be involved in a proton relay involving its protonated state6–8. The ribozyme recruits glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) as a cofactor that has been shown to act as the general acid in the self-cleavage mechanism (Fig. 1b)9–12. The work presented here focuses on identifying and understanding the multiplicity of catalytic roles that the GlcN6P cofactor serves within the glmS ribozyme. We examine the reaction in the presence of the GlcN6P cofactor (holoribozyme) and measure thio effects and metal ion rescue to investigate the contributions of metal ions to the reaction in a stereospecific way. In an effort to understand additional roles the cofactor might be playing, we also study the aporibozyme that lacks the GlcN6P cofactor, again measuring thio effects and metal ion rescue. Calculations performed in the presence and absence of GlcN6P provide molecular level insight into the experimental observations.

Figure 1. Secondary structure, active site, and overall fold-SAXS envelope of the glmS ribozyme.

(a) Secondary structure of the two-piece glmS ribozyme from B. anthracis used in these studies, modeled after a previously published secondary structure . T he GlcN 6P cofactor is shown in red along with the contacts it makes to the glmS ribozyme, which include G1(5’O), G1(pro-RP), A42(2’O), U43(O4), U43(pro-RP), and G57(N1). (b) Hydrogen bonding interactions of the non-bridging oxygen atoms of the scissile phosphate. The non-bridging oxygen atoms are shown as red spheres and labeled ‘pro-RP’ and ‘pro-SP’. The pro-RP oxygen accepts hydrogen bonds from G57(N2) and GlcN6P(O1). The pro-SP oxygen accepts hydrogen bonds from both the N1 and N2 of G32. GlcN6P is also shown interacting with the G1(5’O) leaving group. Nucleotides bordering the scissile phosphate are blue; other nucleotides are magenta. Adapted from the B. anthracis crystal structure (PDB ID 2NZ4).10 (c) Overlay of the SAXS reconstruction for the wild-type aporibozyme with oxo substrate (constructed from ten independent DAMMIF runs) and crystal structure from PDB ID 2NZ4 modified using Coot39 to match the experimental construct. See Supplementary Information for complete SAXS data.

Through these combined experimental and computational studies, we identify four roles for the GlcN6P cofactor within the glmS ribozyme: protonation of the 5′O leaving group, alignment of the active site, activation of the 2′O nucleophile, and charge stabilization of the non-bridging oxygen atoms during the reaction. These findings illustrate new ways in which RNA enzymes can perform chemical catalysis. Cofactors or nucleobases could play similar roles in other RNA enzymes, both in modern biology as well as in the RNA world.

RESULTS

Optimization of ribozyme constructs

RNA enzymes are prone to misfolding13. In an effort to attain a homogeneous natively folded ribozyme population, we tested various ribozyme preparations and renaturation protocols. Ideally, kinetic profiles should be monophasic, fast, and go to completion—behavior that simplifies mechanistic interpretation of the data14,15. We pursued various purification and renaturation protocols of the ribozyme and characterized these by kinetic profiles and small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) (Online Methods).. We identified an optimal preparation of ribozyme that reacts in a monophasic, fast (kobs = 80 min−1), and complete (90%) fashion according to equations (1) and (2) (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. 1); has saturating concentrations of enzyme, GlcN6P cofactor, and Mg2+ (Supplementary Fig. 2); and is monomeric and natively folded according to SAXS Rg, MW, and Dmax values, as well as SAXS profile overlays with the crystal structure (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Table 1, and Supplementary Fig. 3). As described below, this optimized ribozyme was subjected to detailed kinetic analyses to assess contributions that the GlcN6P cofactor makes to catalysis.

Large normal thio effects revealed for the holoribozyme

Effects of sulfur substitution at the non-bridging oxygen atoms of the scissile phosphate were previously reported under slow-reacting conditions for the glmS ribozyme16. In that work, the RP and SP thio diastereomers were left as a mixture, and a ~3-fold thio effect was observed in 10 mM Mg2+. We note that these rates were ~100-fold slower than those herein. Additionally, rescue of the thio effect was tested in Mn2+, which was found to not rescue16, but not in Cd2+ which is a more thiophilic metal ion17.

We probed the effect of sulfur substitution at each of the non-bridging oxygen atoms independently using our fast-reacting glmS construct. The RP and SP thio diastereomers were separated by HPLC and confirmed using mass spectrometry (Supplementary Fig. 4). Rate constants were determined for the oxo, RP thio, SP thio, and dithio substrates, using rapid-quench and hand-mixing kinetics as appropriate, and used to calculate thio effects. Kinetic parameters are provided in Supplementary Table 2. For the holoribozyme, in 10 mM Mg2+, the RP and SP thio substrates react with rate constants (+/− s.d.) of 0.40 ± 0.05 min−1 and 5 ± 1 min−1, respectively, while the oxo substrate reacts with a rate constant of 80 ± 20 min−1 (Fig. 2a). Thus, both the RP and SP thio substrates react significantly slower than the oxo substrate, giving thio effects of 200 and 15, respectively, in 10 mM Mg2+. These effects are much larger than 3-fold thio effects previously reported16. This may be because the constructs used herein are fast reacting and so report the chemical step of the reaction.

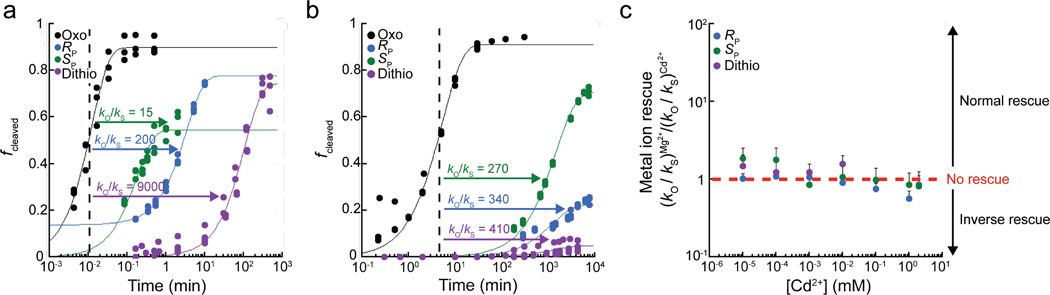

Figure 2. Large normal thio effects and lack of metal ion rescue for the holoribozyme.

(a,b) Fraction cleaved versus time traces demonstrating large normal thio effects in the presence of 10 mM GlcN6P cofactor for the RP thio (blue), SP thio (green), and dithio (purple) substrates compared to the oxo substrate (black) in (a) 10 mM Mg2+ and (b) 3 M K+ with 100 mM EDTA. Values of the thio effects are provided in the panels. Individual data points from at least three independent trials are plotted in panels (a) and (b). Kinetic data in these panels are zero-subtracted and so were fit to a version of equation (1) that forces them through zero, except for the RP thio substrate in 10 mM Mg2+, which was fit to equation (1) as given owing to background cleavage before initiation with cofactor, stemming from the inverse thio effect in the aporibozyme. (c) Thiophilic metal ion rescue values in the presence of 10 mM GlcN6P cofactor for the RP thio, Spthio, and dithio substrates as a function of Cd2+ concentration in a background of 10 mM Mg2+. Each data point in panel (c) is the average of at least three independent trials, where standard deviation is indicated with error bars.

A dithio substrate with sulfur substitution at both of the non-bridging oxygen was also tested for reactivity. This substrate reacts very slowly with a rate constant of 0.009 ± 0.001 min−1 but still with an amplitude of 75% indicating that most of this substrate is involved in a productive reaction channel. The thio effect for the dithio substrate is ~9,000-fold, which is ~3-fold of the product of the RP and SP thio substrate thio effects, indicating that the effects of sulfur substitutions are approximately additive. A large thio effect for the dithio substrate emphasizes the important roles non-bridging oxygen atoms play during the chemical step of self-cleavage.

High concentrations of monovalent ions support glmS ribozyme cleavage activity16,18,19. Stereospecific thio effects under these conditions can test whether the mechanism is similar to that in the presence of divalent metal ions. The RP thio, SP thio, and dithio substrates were thus subjected to reaction in 3 M K+, conducted in the presence of 100 mM EDTA to chelate any contaminating divalent metal ions20,21. These experiments revealed large normal thio effects, similar in magnitude to those in 10 mM Mg2+ (compare Fig. 2a to 2b). The thio effects for the RP thio, SP thio, and dithio substrates are 340, 270, and 410, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). We note that the amplitudes for the RP thio and dithio substrates are diminished but measureable under these conditions. The data can be considered semi-quantitatively as well, examining the extent of reaction at a fixed point in time. Reactivity follows the order oxo>SP thio>RP thio>dithio for 10 mM Mg2+ and 3M K+/100 mM EDTA conditions. The matching nature of these trends suggests that divalent cations do not play a direct role in catalysis of holoribozyme self-cleavage. To test this notion directly, we carried out metal ion rescue experiments.

Metal ion rescue is not observed for the holoribozyme

As described, all thio substrates show large, normal thio effects in the holoribozyme. One possible explanation is inner-sphere interaction of a metal ion with a non-bridging oxygen atom22. Prior studies investigated metal ion rescue but, as described above, were conducted on a mixture of thio substrates in which chemistry was not fully rate-limiting, and the most thiophilic metal ion, Cd2+, was not tested16. We conducted kinetics in the presence of various levels of Cd2+ in a background of 10 mM Mg2+ and 10 mM GlcN6P (Supplementary Table 2). For the RP and SP thio substrates at all concentrations of Cd2+ tested, the magnitude of kO/kS in the presence of Cd2+ and 10 mM Mg2+ is approximately the same as that in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ alone, giving rise to a metal ion rescue of unity, i.e. no rescue (Fig. 2c). For instance, at the highest Cd2+ concentration tested (2 mM), the RP and SP thio substrates exhibit kO/kS values of 170 and 18, respectively, while in just 10 mM Mg2+ these substrates gave similar values of 150 and 15, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). For the dithio substrate, no rescue was found up to 0.01 mM Cd2+; higher concentrations of Cd2+ could not be assessed due to desulfurization (see Online Methods). Lack of metal ion rescue directly supports absence of a metal ion at the active site of the holoribozyme, consistent with above observation that thio effects are similar in 10 mM Mg2+ and 3 M K+ for all three substrates.

Large normal thio effects are supported by simulations

The previous sections revealed large, normal thio effects in the holoenzyme and showed that they were not due to the participation of divalent metal ions. We turned to calculations to gain insight into the origin of these effects. Three independent 50 ns classical molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories were propagated starting from different initial configurations. In one trajectory, GlcN6P(O1) (93%), G57(N2) (52%), and A–1(O2′) (21%) compete to form a bifurcated hydrogen bond with the pro-RP oxygen. (Percentages of configurations where the pro-RP oxygen exhibits hydrogen bonds with these moieties are provided in parentheses; see Fig. 1b for hydrogen bonding interactions.) In 77% of the configurations for this same trajectory, the A–1(O2′) hydrogen bonds to the putative base G33(N1). For the other two independent trajectories with different initial configurations, alternative hydrogen-bonding patterns are observed. In one of these trajectories, the pro-RP oxygen is hydrogen bonded to A– 1(O2′) and GlcN6P(O1) during the entire trajectory, while in the other trajectory, the pro-RP oxygen is hydrogen bonded to the N1 and N2 of G57 during the entire trajectory. Given the dependence of the hydrogen-bonding patterns on the initial configuration, it is likely that the pro-RP oxygen could accept hydrogen bonds from any two of these hydrogen bond donors at a given time and that the hydrogen-bonding pattern changes due to thermal fluctuations. However, the trajectories were not long enough to observe such changes in the hydrogen-bonding pattern or to determine the relative probability of each pattern. Notably, the hydrogen-bonding interactions between the pro-RP oxygen and the cofactor or G57 weaken the observed hydrogen bond between A–1(O2′) and the pro–RP oxygen.

We next examined the effect of substituting sulfur at the pro-RP oxygen. Quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) geometry optimization of two different configurations, in which the pro-RP oxygen is hydrogen bonded to both G57(N2) and GlcN6P(O1) or to both A–1(O2′) and GlcN6P(O1), indicated a lengthening of these hydrogen bonds when the pro–RP oxygen is substituted by sulfur (Supplementary Table 4). For instance, the hydrogen bond distances increase from 2.80 and 2.63 Å to 2.97 and 2.94 Å, and from 2.85 and 2.69 Å to 3.23 and 3.22 Å, respectively. As a result of the increased distance between GlcN6P and the pro-RP sulfur, the positively charged cofactor is less effective in aligning the active site and in stabilizing the developing negative charge on the non–bridging sulfur atoms during the self–cleavage reaction. This reduction in stabilization is consistent with the experimentally observed normal thio effect at the pro–RP oxygen, in which the rate constant decreases severely upon sulfur substitution. Note that this analysis is based only on distances and does not provide information about free energy differences related to this stabilization.

A similar analysis was performed for the hydrogen-bonding interactions involving the pro-SP oxygen. The pro–SP oxygen forms hydrogen bonds with G32(N1) and sometimes G32(N2) during the three classical MD trajectories. QM/MM geometry optimizations were used to examine the thio effect at the pro-SP position and revealed that thio substitution at the pro-SP oxygen lengthens the hydrogen-bonding distance to G32(N1) (Supplementary Table 4). The hydrogen-bonding interaction between the pro-SP oxygen and G32 helps align the active site and provides stabilization for the developing negative charge on the non–bridging oxygen atoms during the self-cleavage reaction. Thus, weakening of this hydrogen bond upon sulfur substitution is consistent with the experimentally observed normal thio effect at the pro-SP position.

Inverse thio effect for RP thio substrate in aporibozyme

Given the large normal thio effects found for the holoribozyme, some of which arose from the GlcN6P cofactor, we reasoned that the cofactor might perform diverse catalytic roles in the reaction. In order to test this idea, we performed thio effect and metal ion rescue studies in the absence of the cofactor. Previous crystallographic studies suggest that the ribozyme structure is pre-formed prior to GlcN6P binding, indicating that the cofactor is not an allosteric cofactor (Supplementary Table 3)23. This is supported by our SAXS experiments comparing holo and aporibozymes (Supplementary Fig. 3).

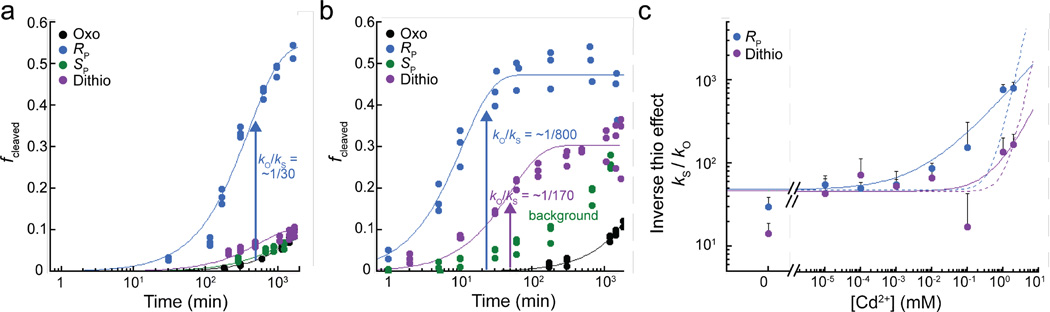

Removing the cofactor reduces rate constants of self-cleavage for all substrates (Supplementary Table 5). However, in the presence of 10 mM Mg2+ and the absence of GlcN6P, the RP thio substrate cleaves with a much faster rate constant than the oxo substrate, giving rise to a large inverse thio effect of ~30 (Fig. 3a). In other words, having sulfur at the pro-RP position of the scissile phosphate facilitates ribozyme self-cleavage. Additionally, an inverse thio effect exclusively in the aporibozyme suggests that in the holoribozyme, GlcN6P may perform a related beneficial role (see Discussion). In contrast to the RP thio substrate, the SP thio substrate is essentially as unreactive as the oxo substrate in 10 mM Mg2+ and the absence of GlcN6P, while the dithio substrate shows a slight inverse thio effect (see Fig. 3a).

Figure 3. Large inverse thio effect and presence of metal ion rescue for the aporibozyme.

(a) Fraction cleaved versus time traces in 10 mM Mg2+ showing a ~30-fold inverse thio effect for the RP thio substrate (blue). The SP thio substrate (green) displays similar reactivity as the oxo substrate (black), and the dithio substrate (purple) displays a slightly inverse thio effect. (b) Fraction cleaved versus time traces in 2 mM Cd2+ in 10 mM Mg2+ showing an increase in reactivity for the RP thio and dithio substrates versus the 10 mM Mg2+-alone conditions. Individual data points from at least three independent trials are plotted in panels (a) and (b). Kinetic data in panels (a) and (b) were zero-subtracted and fit to a version of equation (1) (or equation (2)) that forces them through zero. The SP thio substrate (green) data represent background (see Supplementary Fig. 5). (c) Inverse thio effect values (kS/kO) for the RP thio and dithio substrates as a function of Cd2+ concentration in a background of 10 mM Mg2+. Fits are to a binding equation (equation (5)) where the Hill coefficient was floated (solid lines) or fixed to 2 (dashed lines). Data for the RP and dithio substrates gave floating Hill coefficient values of 0.5 and 0.9, respectively; these data fit poorly to a binding equation with a Hill coefficient fixed at a value of 2. Each data point in panel (c) is calculated using two rate constants, each of which was measured three or more times.

According to the MD simulations described above for the holoenzyme, GlcN6P(O1) donates a hydrogen bond to the pro-RP oxygen of the scissile phosphate 93% of the time in one of the trajectories. Thus, GlcN6P, when present, can weaken the hydrogen-bonding interaction between the A–1(O2′) nucleophile and the pro–Rp oxygen via this competition. By liberating the A–1(O2′), the cofactor allows the putative base G33(N1) to deprotonate the nucleophile and promotes the nucleophilic attack of A–1(O2′) on the scissile phosphate. Simulations on the aporibozyme further support this model (see below).

Metal ion rescue is observed for aporibozyme

In the holoribozyme, normal thio effects were found for all three thio substrates, and these were not rescuable by Cd2+. We tested for divalent metal ion binding in the aporibozyme through the addition of Cd2+ in a background of 10 mM Mg2+. In contrast to the holoribozyme, strong metal ion rescue is observed for the aporibozyme. In 2 mM Cd2+, self-cleavage activity is rescued for the dithio substrate (metal ion rescue of at least 12) and is enhanced for the RP thio substrate (metal ion rescue of 30), whereas self-cleavage activity of the oxo substrate remains relatively unchanged (Fig. 3b). Metal ion rescue of the SP thio substrate could not be assessed due to background reaction (Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, a metal ion interacts stereospecifically with the scissile phosphate in the aporibozyme.

In order to quantitate rescue and test for saturation, we next plotted the data as inverse thio effect versus Cd2+ concentration, as previously described17. The inverse thio effect is relatively independent of Cd2+ concentration up to ~1 µM Cd2+ given the errors in the values, consistent with absence of significant Cd2+ binding over this concentration range. The metal ion rescue is apparent at higher Cd2+ concentrations, although it does not saturate for either of the thio substrates (Fig. 3c). This lack of saturation is not surprising, as this site evolved to bind an organic cofactor rather than a metal ion; moreover, similar plots for the group I intron, which binds three metal ions, did not reveal saturation of the rescuing metal ion either, even with dithioates17. The data fit well to equation (5) in which the RP thio and dithio substrates give Hill coefficients of 0.5 and 0.9, respectively.

Inverse thio effect is diminished by Mg2+

The large inverse thio effect observed for the RP thio substrate in the aporibozyme supports a model in which the A–1(O2′) is sequestered in hydrogen bonding with the pro-RP oxygen of the scissile phosphate for some fraction of time, while the metal ion rescue seen in the aporibozyme supports a metal ion binding at the scissile phosphate. We reasoned that at high concentrations, Mg2+ ions may bind at the scissile phosphate and in so doing compete with and liberate the A–1(O2′). To test this idea, we measured the thio effect for the RP thio substrate in the aporibozyme as a function of Mg2+ concentration (Supplementary Table 5). Increasing the concentration of Mg2+ from 1 to 50 mM resulted in increase in reactivity of both the RP thio and oxo substrates, with a larger increase for the oxo substrate (Fig. 4a). The inverse thio effect thus trended downward with increasing Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 4b). In particular, inverse thio effects of 50 and 17 were observed at Mg2+ concentrations of 1 and 50 mM, corresponding to an ~3-fold decrease in inverse thio effect. The increase in the oxo substrate rate with increasing Mg2+ concentration suggests that a divalent metal ion can provide a similar beneficial effect as a sulfur substitution at the pro-RP oxygen.

Figure 4. Increasing concentrations of Mg2+ in the aporibozyme result in diminished inverse thio effect for the RP thio substrate.

(a) Fraction cleaved versus time traces for the oxo (black) and RP thio substrate (blue) in 1 mM (open circles; dashed line) and 50 mM (closed circles; solid line) Mg2+ for the aporibozyme. (b) Increasing the concentration of Mg2+ from 1 to 50 mM decreases the inverse thio effect value in the aporibozyme. The line is drawn to denote the trend. Oxo substrate data did not show a plateau for low Mg2+ concentrations; as such, all oxo data in this plot were fit to a version of equation (1) with a common end point. We chose the end point to be that in 10 mM Mg2+ (88%) because this is the standard Mg2+ concentration in our study. Data points in both panels are the average of at least three independent trials, where standard deviation is indicated with error bars.

Simulations support inverse thio and metal ion effects

The previous section revealed metal ion rescue for the thio substrates in the aporibozyme. In an effort to understand these effects, we performed classical and QM/MM calculations for the aporibozyme with a Mg2+ ion introduced at the cleavage site. We first investigated the coordination of Mg2+ to non-bridging oxygen atoms at the scissile phosphate and compared this to the experimental results of the last section where Mg2+ diminishes the inverse thio effect. We then calculated the effects of thio substitutions at these oxygen atoms and compared these to our observed inverse thio effect.

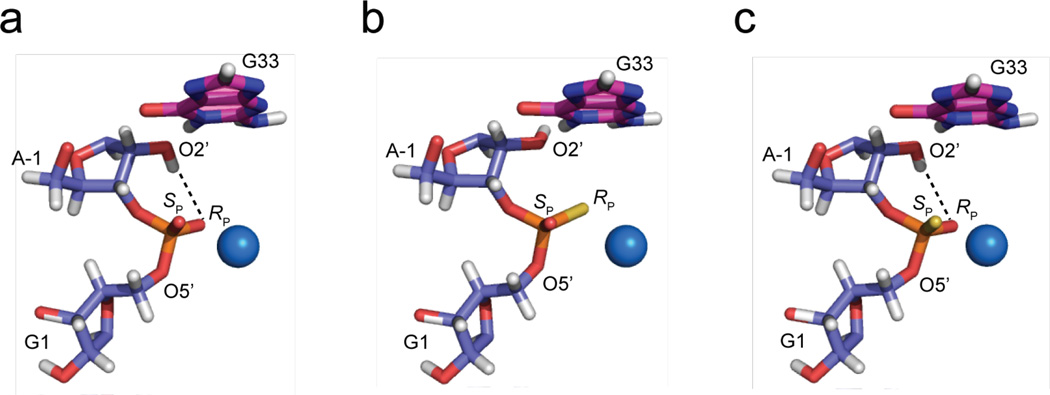

In classical free energy simulations probing the positioning of a Mg2+ ion at the scissile phosphate, the Mg2+ ion was found to be thermodynamically favored near the pro-RP oxygen (). Specifically, the relative free energy as the Mg2+ moves from the pro-RP to the pro-SP site was calculated (Supplementary Fig. 6). These simulations suggest that the Mg2+ ion can interact with either non-bridging oxygen but is thermodynamically favored by ~14 kcal/mol to be coordinated to the pro–RP oxygen, most likely because it is less crowded near the pro–RP oxygen than the pro–SP oxygen. Moreover, when the Mg2+ ion is coordinated to the pro–RP oxygen, the simulations indicate that the A-1(O2′):pro–RP hydrogen bond is disrupted. This observation is consistent with metal ion rescue being observed only at the pro-RP position. As such, we describe here only effects and substitutions when Mg2+ is near the pro-RP position (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 6; effects when Mg2+ is near the pro-SP position can be found in Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 6). When the Mg2+ ion is near the pro-RP oxygen (Fig. 5a), it disrupts or weakens the hydrogen bond between the pro-RP oxygen and the A–1(O2′), according to the results of classical MD simulations, QM/MM geometry optimizations, and QM/MM MD simulations. As discussed below, the inverse thio effect is explained in terms of the sulfur substitution disrupting this inhibitory hydrogen bond. The observation that the Mg2+ ion can also disrupt this hydrogen bond is consistent with the diminished inverse thio effect in high Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 4b).

Figure 5. Active site structures from QM/MM optimizations for glmS aporibozyme with Mg2+ closer to the RP position.

The Mg2+ ion is represented by the blue sphere and is closer to the RP position in these conformations. Only key residues are shown. Sulfur substitution is indicated by yellow, and hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. The optimized geometries are for the (a) oxo substrate, (b) RP thio substrate, and (c) SP thio substrate. See Supplementary Table 6 for distances and angles associated with these three conformations. For the oxo substrate, the A–1(O2′):pro-RP hydrogen bond is relatively weak but stable, with a distance of 3.21 Å between the two oxygen atoms (panel a). In classical MD trajectories of the oxo substrate, the A–1(O2′):pro–RP hydrogen bond was completely disrupted with an average A–1(O2′):pro–RP distance of 4.88 Å and average hydrogen bond angle of 71.6°. Because classical MD simulations may not reliably describe these interactions, a 1 ps nonequilibrium QM/MM MD trajectory was propagated to sample the conformational space near this configuration. In this QM/MM trajectory, the weak hydrogen bond remained with an average A–1(O2′):pro–RP distance of 3.21 Å, while the Mg2+ ion remained coordinated to the pro-RP oxygen. Thio substitution at the pro-RP atom in the Mg2+pro-RP background leads to rotation of 2′OH and therefore disrupts this hydrogen bond, as indicated by the hydrogen bond angle of 67.9° (panel b), while thio substitution at the pro-SP atom does not significantly impact this hydrogen bond (panel c).

We repeated the QM/MM geometry optimizations for the two monothio substrates (Fig. 5b, 5c), starting from a geometry in which the hydrogen bond between the pro-RP oxygen and the A–1(O2′) is weakened but not disrupted. Thio substitution at the pro-RP position disrupts this inhibitory hydrogen bond by decreasing the A-1(O2′):H:RP angle from 144° in the oxo substrate to 67.9° in the pro-RP substrate (Fig. 5b), although the distance between A-1(O2′) and the pro-RP oxygen remains similar (Supplementary Table 6). This disruption of the inhibitory hydrogen bond is qualitatively consistent with the observed inverse thio effect in that it facilitates nucleophilic attack by A–1(O2′). Similar qualitative behavior was observed in our previous thio effect studies of the HDV ribozyme24.

To further examine the interaction between the pro-RP oxygen, the active site Mg2+ ion, and A-1(O2′), we propagated a 1 ps QM/MM MD trajectory for the oxo substrate with the Mg2+ ion near the pro-RP oxygen. In this trajectory, the Mg2+ ion remained closer to the pro-RP oxygen, and the weak hydrogen bond between A-1(O2′) and the pro-RP oxygen was retained. As mentioned above, however, thio substitution at the pro-RP position completely disrupts this inhibitory hydrogen bond, thereby explaining the inverse thio effect. Moreover, at high Mg2+ concentration, the Mg2+ ion can also partially disrupt this inhibitory hydrogen bond as revealed by the 3-fold diminished inverse thio effect.

DISCUSSION

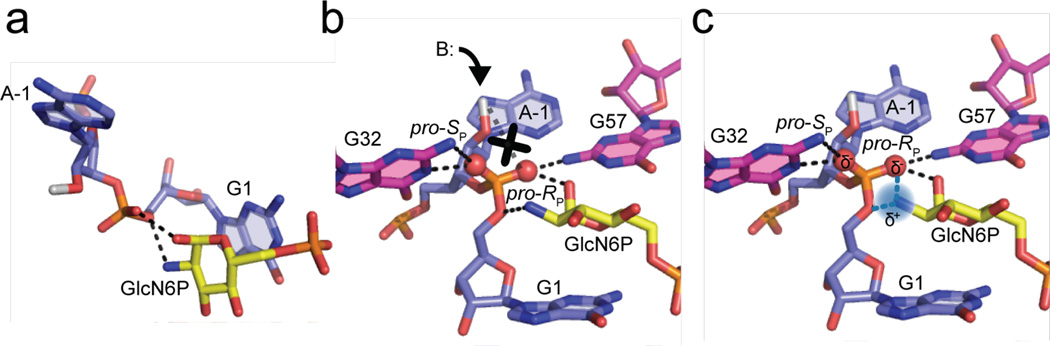

Ribozymes typically use two main species in catalysis, metal ions and nucleobases. Structural and mechanistic studies first elucidated roles for metal ions in ribozymes25,26. More recently, nucleobases were shown to play key roles in the mechanisms of small ribozymes27. In our present study, we investigated the catalytic contributions of a small organic cofactor, which is a third species that ribozymes can use in catalysis. We presented a combination of experiments and calculations which support the premise that the GlcN6P cofactor plays multiple catalytic roles in the holoribozyme; as summarized in Fig. 6, these are (1) donation of a proton to the leaving group as the general acid (Fig. 6a), (2) alignment of the active site (Fig. 6b), (3) disruption or weakening of an inhibitory hydrogen bond involving the nucleophile (Fig. 6b), and (4) stabilization of charge development during the reaction (Fig. 6c). The first role was previously established by structural and mechanistic studies9–11, whereas the other three roles are established in the present study.

Figure 6. Multiple catalytic roles for the GlcN6P cofactor.

(a) Protonation of 5′O leaving group as general acid. (b) Disruption of inhibitory A–1(O2′): pro-RP interaction, denoted with an ‘X’, and alignment of active site via extensive hydrogen bonding with both non-bridging oxygens. The putative base that deprotonates the 2′OH, G33, is denoted as ‘B:’. (c) Stabilization of developing charge on the non-bridging oxygen atoms (partially negative as indicated by the ‘δ’) via hydrogen bonding with various moieties as well as through-space charge-charge interaction with the amine group of the cofactor (partially positive as indicated by the ‘δ+’). Hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions are indicated by dashed black lines and dashed blue lines, respectively.

In this work, we present data for the glmS holoribozyme revealing that thio effects for the SP and especially RP thio substrates are large at 15 and 200, respectively. Previous studies reported thio effects of only ~3 but were under conditions where the observed rate constant was ~100-fold slower16, likely reflecting a rate-limiting conformational change28,29. The large thio effects observed herein, which are similar in magnitude to those in ribozymes where direct interactions with divalent cations mediate catalysis30–32, strongly support chemistry as rate-limiting in our experiments. Calculations suggest that thio effects in the holoribozyme arise from weakening of the hydrogen-bonding interactions of the non-bridging oxygen atoms at the scissile phosphate upon substitutions of sulfur. Weakening of these hydrogen bonds reduces stabilization of the developing negative charge on the non-bridging oxygen atoms during self-cleavage. The larger effect for the RP thio substrate may occur because this phosphate oxygen hydrogen bonds to the cofactor, and sulfur substitution could misalign the cofactor in the active site. Such “approximation” effects are key to enzyme function33; given that the cofactor has multiple roles in catalysis, such perturbations are expected to be especially penalizing. Our studies further reveal that the large thio effects are also present in 3 M K+/100 mM EDTA and are not rescued by Cd2+, indicating that the holoribozyme operates without the participation of divalent metal ions in the active site. Recent calculations on the holoribozyme suggest that the presence of a Mg2+ ion near the scissile phosphate oxygen atoms at the cleavage site would be anticatalytic because of electrostatic repulsion of the cofactor, disruption of key hydrogen bonds, and obstruction of nucleophilic attack34. Apparently, hydrogen-bonding interactions involving nucleobases and the cofactor stabilize charge development in the holoribozyme.

Experiments on the aporibozyme revealed a surprising inverse thio effect of 30, stereospecific for the RP thio substrate. Inverse thio effects at a non-bridging oxygen were reported in the HDV ribozyme in monovalent ions and had a similar mechanistic origin24. We provided a model for the glmS reaction, which was supported by classical MD and QM/MM calculations, wherein this sulfur substitution disrupts an inhibitory A–1(O2′) to pro-RP oxygen hydrogen-bonding interaction. Given the ability of any hydroxyl group to engage in three hydrogen bonding interactions, prevention of spurious 2′OH hydrogen bonding may be an underappreciated strategy of ribozymes to activate the nucleophile. Another intriguing possibility is that the A–1(O2′) to pro-RP oxygen hydrogen-bonding interaction evolved to inactivate the nucleophile in the absence of cofactor. Such hydrogen-bonding interactions may be a general strategy of RNAs to prevent unwanted cleavage. Disruption of the A–1(O2′) inhibitory interaction, revealed by the inverse thio effect at the pro-RP position, is naturally achieved with the oxo substrate in the holoribozyme by GlcN6P, where our calculations reveal that a GlcN6P(O1)-pro-RP hydrogen-bonding interaction acts to help prevent or weaken the inhibitory A–1(O2′) to pro-RP oxygen interaction. Aporibozyme experiments where the concentration of Mg2+ is varied show a diminishing inverse thio effect for the RP thio substrate at high Mg2+ concentrations due in large part to increase in the rate of the oxo substrate, suggesting that Mg2+ can act similarly to both GlcN6P in the holoribozyme and the RP sulfur in the aporibozyme to break the inhibitory A–1(O2′) to pro-RP oxygen interaction. Metal ion rescue experiments in the aporibozyme show rescue by Cd2+ for the RP thio and dithio substrates, indicating the presence of a stereospecific metal ion interaction at the active site of the aporibozyme. Hill coefficients of 0.5 and 0.9 were found for the RP and dithio substrates, respectively. These values are consistent with partial and full occupancy by a single divalent ion for the RP thio and dithio substrates, respectively.

This leads to a model where a divalent metal ion substitutes for the missing GlcN6P cofactor in the aporibozyme and fulfills roles that GlcN6P performs in the holoribozyme. These roles include release of the nucleophile and charge stabilization of the non-bridging oxygen atoms during self-cleavage. We previously presented evidence for the amine group of GlcN6P aiding in charge stabilization8 consistent with this notion. A recent study used in vitro selection to identify a GlcN6P-independent glmS ribozyme35. This selected ribozyme, which had three key nucleotide changes, requires multiple divalent metal ions for activity. Its cleavage mechanism is likely different from that of the wild-type aporibozyme studied herein, however, because phosphorothioate effects in the selected ribozyme were found at positions away from the scissile phosphate.

The glmS holoribozyme operates using exclusively nucleobases and a cofactor at the active site, while the wild-type aporibozyme uses a metal ion to carry out catalytic roles performed by the cofactor. It thus appears that an organic cofactor can assume the role of an inorganic metal ion cofactor in the active site of a ribozyme. Metal ions are ubiquitous in cells and in the active sites of many large and small ribozymes. Thus, one way specificity might evolve in a ribozyme is through substitution of metal ions with an organic cofactor that binds specifically and participates in chemistry. Given the plethora of protein enzymes that use organic cofactors in their reactions, it is plausible that RNA enzymes could use these organic cofactors, several of which derive from adenosine, to do many of the same reactions. Indeed, in vitro selections have identified several RNA and DNA enzymes that use diverse organic cofactors in their mechanisms36–38. The ability of the glmS ribozyme to position a small molecule cofactor to partake in multiple catalytic roles deepens insight into the versatility of catalytic RNA.

ONLINE METHODS

Chemicals

D-glucosamine 6-phosphate (GlcN6P; ≥98%) was purchased (Sigma-Aldrich). A 100 mM stock was prepared and brought to pH 7.0 with a small amount of ~5 M sodium hydroxide. The pH was checked periodically by spotting a small volume on pH paper. Cadmium chloride (CdCl2; ≥99.0%) was purchased (Sigma-Aldrich); a 100 mM stock was prepared and buffered with 10 mM sodium HEPES (pH 7.0) to prevent precipitation as Cd(OH)2. Heparin (sodium salt) from porcine (molecular weight of ~3000) was purchased (MP Biomedicals), LLC and a 5 mM stock solution was prepared (pH ~6.0). All stock solutions were filter sterilized through a 0.2 µ filter prior to use in experiments.

RNA oligonucleotides and constructs

The RNA was prepared as a two-piece construct. The shorter strand, the –3/16 substrate strand, has the sequence 5′ GAA* GCG CCA GAA CUA CAC C, where the asterisk denotes the scissile phosphate and also, therefore, the location of the thio substitutions for the RP thio, SP thio, or dithio substrates. The oxo, RP thio, and SP thio substrates were purchased (IDT or Dharmacon). The RP and SP thio substrates were synthesized on the solid-phase as a mixture of the two diastereomers and were separated using C18 reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Waters ACQUITY Arc instrument. Following a 10 min column equilibration step, a linear gradient from ~3.9 to ~6.2% acetonitrile over 30 min in a constant background of 0.1 M ammonium acetate was used for separation. Identities of the stereoisomers were confirmed by digestion with snake venom phosphodiesterase and nuclease P1, and the RP thio isomer was found to elute before the SP thio isomer, as is typical. After ethanol precipitation, the baseline-separated RP and SP thio stereoisomers were re-injected onto the HPLC to confirm their purity. These substrates were re-injected into the HPLC periodically to ensure both purity and absence of desulfurization. The dithio substrate was prepared using automated, solid-phase phosphorothioamidite chemical synthesis by AM Biotechnologies, LLC. Purities of the oxo and dithio substrates were also assessed using the HPLC gradient above and gave single peaks as expected. Retention times for the oxo, RP thio, SP thio, and dithio substrates were ~24, 24, 29, and 26.5 min, respectively. Absence of oxo substrate in the RP thio substrate, which had the same retention time despite trying multiple elution conditions, was ascertained by absence of a burst phase in the holoribozyme after obtaining new RP thio substrate or re-purification of existing RP thio substrate. The identities of the RP thio, SP thio, and dithio substrates were confirmed by mass spectrometry, which was performed by the Penn State Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Core Facility - University Park, PA. The purified substrate strands were radiolabeled on their 5’-ends using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]ATP.

The enzyme strand was prepared by T7 transcription under standard conditions (100 ng/µL DNA template; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 25 mM MgCl2; 2 mM DTT, 1 mM spermidine; and 4 mM each ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP) using a double-stranded template, which was prepared as follows. A plasmid containing the full 169 nt ribozyme, obtained as a gift from Professor Michael Been at Duke University Medical Center, was transformed into competent DH5α E. coli cells and amplified, and the sequence was confirmed with dideoxy sequencing, which was performed by the Penn State Genomics Core Facility -University Park, PA. The plasmid served as a template for PCR reactions to produce the double-stranded glmS enzyme strand DNA template used for transcriptions. A top strand (forward) primer of the sequence 5′ GCT AAT ACG ACT CAC TAT AGG TGT AGT TGA CGA GGT GGG GT, which contains the T7 promoter sequence, and a bottom strand (reverse) primer of the sequence 5′ TCT CTC ATC ACA CTT TCA CCT TTG were used to amplify the portion of the plasmid corresponding to the 18/145 glmS enzyme strand. Transcriptions using an annealed aliquot of this PCR product afforded the 128 nt enzyme strand of the ribozyme with the sequence 5′ GGU GUA GUU GAC GAG GUG GGG UUU AUC GAG AUU UCG GCG GAU GAC UCC CGG UUG UUC AUC ACA ACC GCA AGC UUU UAC UUA AAU CAU UAA GGU GAC UUA GUG GAC AAA GGU GAA AGU GUG AUG AGA GA. Following transcription, the enzyme strand was purified on a 6% denaturing PAGE gel, visualized by UV shadowing, and the appropriate band was excised, and eluted overnight at 4°C into 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 250 mM NaCl. The extracted RNA was precipitated with three volumes of ethanol and re-suspended in sterile water. All RNA samples were stored at −80°C.

Ribozyme kinetic assays and data analysis

Unless otherwise noted, typical self-cleavage reactions contained 0.25 nM radiolabeled substrate and enzyme at a saturating concentration of 100 nM. For all experiments, the enzyme and substrate RNA were brought to 1/20 the total reaction volume in a final concentration of 10 mM HEPES (pH 6.0) and 100 mM K+ prior to renaturation as described below.

Experiments in the presence of GlcN6P contained 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 10 mM GlcN6P, and either 10 mM Mg2+/50 mM Na+ or 3 M K+/100 mM EDTA. For the metal ion rescue experiments, various concentrations of Cd2+ were added in the background of 10 mM Mg2+, which was used to keep the ribozyme folded. For these holoribozyme reactions, the RNA stock was heated at 95°C for 3 min and snap-cooled on ice for 10 min. The RNA stock was then combined with the rest of the reaction mixture excluding GlcN6P, heated at 55°C for 3 min, and cooled at room temperature for 10 min to afford optimal reacting ribozyme (standard holoribozyme renaturation). For reactions where time points were collected by hand, a zero time point was taken from this mixture and 90 µL of the mixture was added to 10 µL of a 100 mM GlcN6P stock, done in this order to afford good mixing. For reactions that proceeded too fast to be monitored by hand (> ~2 min−1), rapid mixing experiments were performed using a Kintek RQF-3 Rapid Quench-Flow instrument. Holoribozyme experiments with the RP thio substrate, which had the large inverse thio effect without cofactor, as well as some control experiments with the oxo substrate were not subjected to heating at 55°C for 3 min and cooling at room temperature for 10 min in order to minimize the fraction of ribozyme cleaved at initiation with GlcN6P.

Experiments performed for the aporibozyme contained 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) and 10 mM Mg2+/50 mM Na+ without added cofactor. For aporibozyme metal ion rescue experiments, various concentrations of Cd2+ were added in the background of 10 mM Mg2+, which was used to keep the ribozyme folded. For the aporibozyme experiments, the RNA stock was heated at 95°C for 3 min and snap-cooled on ice for 10 min to afford optimal reacting ribozyme (standard aporibozyme renaturation). Next, 5 µL of the RNA stock was aliquoted to a new tube to which the metal and buffer solution was added to initiate the reaction. Of the remaining renatured RNA stock, a zero time point was taken after appropriate dilution.

For both the holo and aporibozyme hand mixing experiments, time points were taken throughout each reaction and quenched with an equal volume containing EDTA in excess of Mg2+, 1 mM heparin to prevent RNA aggregation in gel wells, and ~70% formamide. Time points were diluted 1:10 with a solution containing formamide and 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5) to minimize smearing of bands on gels due to high concentrations of salt. For the holoribozyme rapid mixing experiments, time points were quenched with EDTA in excess of Mg2+. Aliquots of 5 µL from quenched rapid mixing time points were diluted with a 45 µL solution containing similar concentrations of heparin, formamide, and Tris as above. Samples were loaded onto 18% acrylamide/8.3 M urea gels for separation of RNA species, gels were dried, and the fraction of substrate cleaved versus time was calculated after imaging of bands with a Typhoon PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Monophasic data were fit to a single exponential equation of the form

| (1) |

where fcleaved is the fraction of substrate cleaved at time t, A is the final fraction of substrate cleaved, -B is the amplitude of the phase, kobs is the observed rate constant, and A+B is the fraction cleaved at time zero. As needed, data were fit to a double exponential equation of the form

| (2) |

where fcleaved is the fraction of substrate cleaved at time t, A is the final fraction of substrate cleaved, -B is the amplitude of the fast phase, kobs,fast is the observed rate constant of the fast phase, -C is the amplitude of the slow phase, kobs,slow is the observed rate constant of the slow phase, and A+B+C is the fraction cleaved at time zero. For most fraction cleaved versus time plots presented in figures, the fraction cleaved at time zero was subtracted from all data points and points from three separate trials are plotted together.

Aporibozyme experiments and holoribozyme experiments in 3 M K+ required time courses that lasted for several days. In these cases, control experiments were performed with a non-cleavable deoxy substrate to ensure that the substrate strand was not degrading significantly during this time. For all experiments without Cd2+, degradation was less than 8% for the longest time point. For experiments with Cd2+, degradation was less than 11% and 5% for the longest time points with the apo and holoribozymes, respectively.

All thio substrates were tested for desulfurization in the presence of varying concentrations of Cd2+ up to 2 mM and in the absence of Cd2+ in both the holoribozyme and aporibozyme without the enzyme RNA strand present. Samples were incubated in the presence or absence of GlcN6P and Cd2+ for timescales relevant to the ribozyme reactions. Samples were quenched with excess EDTA, ethanol precipitated, and run on HPLC with the column heated to 65 °C. In the holoribozyme, significant desulfurization of the dithio substrate occurred at Cd2+ concentrations above 10 µM on the timescale of the ribozyme reaction for this substrate. Thus, these points were not included. In the aporibozyme, some desulfurization of the thio substrates occurred at higher concentrations of Cd2+ on the timescale of the ribozyme reactions. However, because the oxo substrate is the slowest reacting of all the substrates, this leads to observed thio effects for the aporibozyme that are a lower limit to the actual thio effects of these thio substrates.

Thio effects and metal ion rescue

The effect of substituting a sulfur atom for a non-bridging oxygen atom at the scissile phosphate is referred to as a thio effect, which was determined for non-thiophilic metal ions such as Mg2+ and K+ as

| (3) |

where kO and kS are the observed rate constants for the oxo and thio substrates. Three limiting outcomes are possible: kO = kS, no thio effect; kO > kS, normal thio effect; kO < kS, inverse thio effect. For the holoribozyme reactions with the RP thio substrate where the cofactor-free renaturation did not include the step of heating at 55°C and cooling at room temperature, the thio effect was calculated using a kO from a reaction with oxo substrate that was renatured in the same manner.

To test if a thio effect is due to loss of metal ion binding at the site of sulfur substitution, experiments were performed with the thiophilic metal ion Cd2+ in the reaction mixture. The effect of adding the thiophilic metal ion is measured as “metal ion rescue,” given by

| (4) |

17. A value of unity indicates no metal ion rescue and thus suggests no metal ion interaction at the site of sulfur substitution, whereas a value greater than one indicates normal metal ion rescue, which suggests interaction between the thio-substituted atom and thiophilic metal ion. Plots of inverse thio effect versus the concentration of Cd2+ were fit to the binding equation given by

| (5) |

17 where is the ratio kS/kO (the inverse thio effect), is kS/kO in 10 mM Mg2+ (a value that was defined for each substrate individually during the fitting process to be the average kS/kO for the four lowest Cd2+ concentrations of 0, 0.01 µM, 0.1 µM, and 1 µM Cd2+ ), KD is the dissociation constant for Cd2+ binding, and n is the Hill coefficient. In some cases n was left as a floating variable, whereas in other cases n was set as a fixed value.

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and gel shift assays

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was used to purify some of the glmS enzyme strand and to test whether the denaturing gel-purified and native gel-purified enzyme species were folded similarly. Native gels contained 1X THE (34 mM Tris, 66 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, and 8% acrylamide and were run at 37°C. RNA samples were renatured as described above (see standard holoribozyme renaturation) prior to loading onto the running gel. SYBR Gold was used to stain the gels and a Molecular Imager Gel Doc XR System (Bio-Rad) was used to visualize the stained gel.

Gel shift assays to determine the KD of substrate to enzyme binding were performed using native gels containing 1X THE (pH 7.0), 10 mM MgCl2, and 20% acrylamide and run at 37°C. RNA samples were renatured as described above (see standard holoribozyme renaturation) prior to loading onto the running gel.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) data collection

In order to probe the global folding of the glmS ribozyme under various experimental conditions, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) experiments were performed. Data were collected at room temperature on beamline G1 at MacCHESS, the Macromolecular Diffraction Facility at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS)40,41 . The detector used was a dual 100K-S SAXS/WAXS detector (Pilatus). The sample-to-detector distance setup allowed simultaneous collection of small- and wide-angle scattering data covering a momentum-transfer range (q-range) of 0.0075 < q < 0.8 Å−1 (q = 4πsin(θ)/λ, where 2θ is the scattering angle). The energy of the X-ray beam was 9.962 keV with a wavelength of 1.245 Å and the beam diameter was 250 µm × 250 µm.

Prior to all data collection, RNA was renatured similar to how it is for kinetic experiments. Samples were then spun down at 6K rpm for 7 min to remove any particulates prior to injection into either a Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) or a KW402.5–4F size-exclusion column (Shodex) for size-exclusion chromatography SAXS. In the inline size-exclusion chromatography setup, a GE HPLC (ÄKTApurifier) routed sample directly and continuously into the BioSAXS flow cell as the SAXS data was being collected. Sample was monitored with UV-vis detection in line with scattering detection.

The folding of the RNA in 10 mM Mg2+ , 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), and 50 mM Na+ (conditions corresponding to the Mg2+ kinetic experiments) was probed using SEC-SAXS at room temperature. Renatured samples were loaded at a concentration of 0.6 mg/mL onto a SEC column pre-equilibrated with buffer containing the same reagents as the samples at a flow rate of 0.12 mL/min. Buffer that eluted before the RNA was used as the buffer blank.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) data analysis

After the images were collected, scattering profiles were generated for each sample and buffer-subtracted using BioXTAS RAW42. For the SEC-SAXS data (Supplemental Fig. 3), three sections of the SEC RNA trace were analyzed: a middle portion consisting of twenty frames and a left and a right portion each consisting of twenty frames spaced thirty frames to the left and right of the middle portion. For the buffer subtraction, forty frames to the left of the SEC peak were used. In some cases, the left-most portion of the SEC peak showed evidence of a slightly larger SAXS envelope, and for this reason, the middle portion of the peak was used for data analysis. Molecular weight and Rg calculations were performed across the entire peak for SEC samples using BioXTAS RAW (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Kratky plots (I(q)*q2 versus q) were generated and a Guinier analysis was performed using BioXTAS RAW. The linear region of the ln(I) vs. q2 plot where qmaxRg < 1.3 was used for the Guinier analysis. The forward scattering I(0) as well as the radius of gyration (Rg) and molecular weight (Supplementary Table 1) were calculated using the Guinier approximation, which assumes that at very small angles (q < 1.3/Rg) the intensity is approximated as I(q) = I(0)exp(−(qRg)2/3). The maximum particle dimension (Dmax) and Rg (Supplementary Table 1) were estimated from the pair-distance distribution function p(r) that was computed using GNOM. The program PRIMUS from the ATSAS software package43 was used for running GNOM.

The GNOM output file was subsequently submitted to the online DAMMIF server to create ab initio models using low-resolution data in the range 0 < q < ~0.28 Å−1. The DAMMIF algorithm constructs bead models that yield a scattering profile closest to the experimental data, with the lowest possible discrepancy (χ), while keeping the models compact with the beads interconnected. Ten independent DAMMIF runs were performed and consensus shape reconstruction was done with DAMAVER43. The normalized spatial discrepancy (NSD) parameters provided by DAMAVER for the corresponding DAMFILT envelopes indicate that the similarity between each set of ten models is high (average NSD value is ≤1).

Coot39 was used to correct a glmS ribozyme crystal structure from Bacillus anthracis (2NZ4) to match the construct used for the SAXS experiments. This included removing of the loop at the end of P1, mutating nucleobases to match the experimental sequence, and choosing a conformation of the non-crystallographic 3′-tail (residues 142–145) to suitably match the SAXS envelope. The DAMFILT envelope was then overlaid with this Coot-corrected crystal structure model using SUPCOMB43 (RMSD and excluded volume values in Supplementary Table 1). Comparison of the SAXS envelope and the Coot-corrected glmS crystal structure was performed using Pymol44. The theoretical scattering profile of the Coot-corrected crystal structure was calculated and fit to the experimental data using CRYSOL. The program CRYSOL was also used to calculate the theoretical Rg value of the Coot-corrected crystal structure model.

Optimization and SAXS characterization of ribozyme constructs for mechanistic studies

The enzyme RNA strand was purified by either denaturing or native preparative PAGE and then analyzed by denaturing or native analytical PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Denaturing PAGE purification afforded one band (labeled ‘DM’ for denaturing monomer) that had fast mobility on the analytical native PAGE, whereas native PAGE purification afforded two bands (labeled ‘NM’ and ‘ND’ for native monomer and dimer) that had slower and much slower mobilities as compared to DM on the analytical native PAGE. Each of these three enzyme species (NM, ND, and DM) ran identically on the denaturing PAGE confirming that they are the same length and not degraded (Supplementary Fig. 1a). These enzyme species were tested for self-cleavage activity with the oxo substrate, under renaturation conditions determined to be optimal (see below), and all three enzyme species (NM, ND, and DM) reacted with similar reaction profiles (data not shown). Because DM migrated fastest by native PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 1a), it was deemed likely to be the most compact of the purified enzyme samples, which was confirmed by SAXS where the NM/ND mixture showed an extended SAXS envelope (see below). The DM species was further analyzed by several renaturation protocols and tested for native folding by SAXS (see below).

Several renaturation procedures were tested on the DM ribozymes. Incubation times and temperatures, point of MgCl2 addition, and presence or absence of an additional incubation at 55°C and cooling at room temperature for 10 min were varied. The optimal renaturation identified involves incubation at 95°C for 3 min, snap-cooling on ice for 10 min, and incubation at 55°C for 3 min in the presence of Mg2+ followed by cooling at room temperature for 10 min. The oxo substrate and denaturing gel-purified enzyme subjected to this renaturation react in a monophasic fashion with a very fast rate constant of 80 min−1, which goes to 90% completion (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c). These rates are similar to those used for general acid studies on the glmS ribozyme11. In addition, concentrations of enzyme, GlcN6P cofactor, and MgCl2 were saturating as determined by kinetic and binding assays (Supplementary Fig. 2). As described in the main text, this preparation gave large normal thio effects for the holoribozyme, indicating that chemistry is the rate-limiting step.

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) experiments were performed on the DM apo and holoribozymes bound to either oxo or deoxy substrates at beamline G1 at MacCHESS, the Macromolecular Diffraction Facility at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS)40,41. Samples were fractionated by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) and analyzed by scattering profiles, Kratky plots, p(r) plots, molecular weight vs. elution profiles, Rg vs. elution profiles, and 10 DAMMIF reconstructions (Supplementary Fig. 3). The Rg values from GNOM and Guinier analyses are in excellent agreement (Supplementary Table 1). Similar SAXS parameters were obtained for apo and holoribozymes containing oxo or deoxy substrates. The SEC traces consisted of a single peak, suggestive of one population with a single fold. The Kratky plot returned to baseline, which suggests that the RNA is well-folded and not flexible45,46. The Rg, MW, and Dmax values for the aporibozyme and holoribozyme with the oxo and deoxy substrates were in good agreement with values calculated from the Coot-corrected crystal structure (Supplementary Table 1). For example, the SAXS-measured values for aporibozyme with the oxo substrate for Rg (GNOM), MW (Guinier), and Dmax were 39 Å, 54.1 kDa, and 131 Å, respectively, and the calculated values were 30.3 Å, 47.7 kDa, and 120 Å, respectively. In addition, the SAXS profiles generated for these ribozymes and substrates using the online DAMMIF server overlay well with the crystal structure of glmS ribozyme (PDB ID 2NZ4)10 that was modified to match the experimental construct using Coot (Supplementary Fig. 3)39. In sum, the above analyses support the glmS ribozyme, purified and renatured according to the above protocol, as being a monomeric and natively folded species; having saturating levels of enzyme, cofactor, and Mg2+, and with fast, single-exponential, and complete kinetics having chemistry as the rate-limiting step.

Classical MD simulations

The glmS systems used in the computational studies are from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis. The glmS holoribozyme system was modified from a pre-cleavage crystal structure with deoxyribose A-1 (PDB ID 2Z75), where the A-1(H2′) was replaced by A-1(2′OH). The glmS aporibozyme system was modified from a pre-cleavage crystal structure that included A-1(2′OH) (PDB ID 2GCS). For the above two structures, missing residues and hydrogen atoms were added using the Maestro utility. All of the Mg2+ ions in the crystal structures were retained, and an additional Mg2+ ion was added to the active site of the glmS aporibozyme system at different positions. The subsequent system preparation and classical MD simulations in the NVT ensemble were performed with AMBER1447 using the AMBER FF12 force field48 and additional parameters for Mg2+ ions49 . The ribozymes were solvated with TIP3P explicit water molecules and neutralized by adding Na+ ions, followed by addition of ~0.15 M NaCl. Then the systems were minimized and equilibrated to a temperature of 300 K as follows. Initially a minimization was performed by following seven steps. In the first step, the system was minimized while the solute (ribozyme) atoms were restrained with a force constant of 100 kcal/(mol Å2). In the second step, the system was minimized while the heavy atoms of the solute were restrained with the same force constant. In the next four steps, the full system was minimized while the backbone atoms of the ribozyme were restrained with a force constant decreasing from 100 to 50 to 10 and finally to 1 kcal/(mol Å2). In the seventh step, the full system was minimized without restraints. After minimization, an NVT simulated annealing procedure of 200 ps was performed to raise the system temperature from zero to 300 K, while the solute was restrained with a force constant of 1 kcal/(mol Å2). A 5 ns NPT MD equilibration, followed by a 1 ns NVT MD equilibration, was then performed on the full system without restraints. G33(N1) and A-1(O2’) were in their canonical protonation states for all classical and QM/MM calculations herein. The key hydrogen bonds in the active site were restrained during the minimization and the first two equilibration steps. After equilibration, MD trajectories in the NVT ensemble were propagated. Multiple independent trajectories of 50 ns each were generated for both systems with an additional active site Mg2+ ion positioned at various locations for the glmS aporibozyme system.

Classical free energy simulations

The free energy change associated with the active site Mg2+ moving from the pro-RP site to the pro-SP site in the glmS aporibozyme system was examined with a combination of the finite temperature string method and umbrella sampling. The details of this free energy simulation approach and its application to ribozymes have been discussed elsewhere8,50–53. Because no bonds are broken or formed during the movement of the Mg2+ ion, the classical force field AMBER FF12 was used in these free energy simulations. The system was prepared from an equilibrated structure obtained from a classical MD trajectory of the glmS aporibozyme. The solvent box was truncated to a layer of 10 Å thickness around the ribozyme. The reactant structure has a Mg2+ ion near the pro-RP oxygen of the scissile phosphate, which disrupts the A–1(O2′): pro-RP hydrogen bond. The product structure was generated by manually moving the Mg2+ to the pro-SP site. The initial string was constructed by a linear interpolation of the reactant and product structures. The string was represented with 20 images, and the Mg2+ movement was described with three reaction coordinates (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The CHARMM54 program was used to perform the umbrella sampling, in which the harmonic restraints were applied to the three reaction coordinates for each image. The total sampling time was 7.2 ns. The unbiased free energy surface was obtained using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM)55. Note that the disruption of the A-1(O2′): pro-RP hydrogen bond in the initial string, as well as the properties of the classical force field, may bias the free energy toward Mg2+ being located near the pro-RP oxygen. QM/MM geometry optimizations and MD provided further insights into these issues, as discussed in the main text.

QM/MM geometry optimizations

Configurations obtained from the classical MD trajectories and classical free energy simulations were used as starting structures for QM/MM geometry optimizations. For the configurations obtained from classical MD trajectories, the solvent box was truncated to a layer of 10 Å thickness around the ribozyme. The geometry optimizations were conducted with CHARMM54 interfaced to Q-Chem56. For thio effect calculations, sulfur substitutions were performed manually using the Maestro utility. The QM region contained residues A–1, G1, and G33, as well as the cofactor for the glmS holoribozyme or an active-site Mg2+ ion for the glmS aporibozyme. The QM region was treated at the DFT-B3LYP57–60 level of theory using the 6–31G** basis set. Hydrogen capping was utilized to treat the QM-MM boundary. The MM region was described by the AMBER FF12 force field. The MM residues more than 18 Å from the scissile phosphate were kept frozen during the QM/MM geometry optimizations.

QM/MM MD simulations

Structures from the QM/MM geometry optimizations were used as initial structures for short, nonequilibrium QM/MM MD simulations to further sample the conformational space around the optimized geometries. An interfaced version of CHARMM54 and Q-Chem56 was used to perform these simulations. The QM region was chosen to be the same and was treated at the same level of theory as in the QM/MM geometry optimizations, and the MM region was described by the AMBER FF12 force field. Only the residues within a sphere of 18 Å radius centered at the scissile phosphate were allowed to move. Each nonequilibrium QM/MM MD trajectory was propagated for 1 ps at 300 K.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Been at Duke University Medical Center for the generous gift of the plasmid containing the glmS ribozyme sequence as well as Richard Gillilan and Lois Pollack for help with small-angle X-ray scattering experiments. We also thank Erica Frankel and Kathleen Leamy for assistance with fast hand-mixing reaction time points. Finally, we thank Erica Frankel, Raghav Poudyal, Laura Ritchey, and Pallavi Thaplyal for helpful comments on revising the manuscript. This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant GM056207 (S.Z., D.R.S., and S.H.-S.) and U.S. National Science Foundation Grant CHE-1213667 (J.L.B. and P.C.B.). D. R. S. is a member of the National Institutes of Health Chemistry-Biology Interface (Training Grant NRSA 1-T-32-GM070421). This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by the National Science Foundation. This work is based upon research conducted at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS), which is supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences under NSF award DMR-0936384, using the Macromolecular Diffraction at CHESS (MacCHESS) facility, which is supported by award GM-103485 from the National Institutes of Health, through its National Institute of General Medical Sciences. We also thank the Penn State Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry Core Facility - University Park, PA, and the Penn State Genomics Core Facility - University Park, PA.

Footnotes

Author contributions

J.L.B. and P.C.B. designed experiments. J.L.B. performed the biochemistry experiments. J.L.B., N.H.Y., and P.C.B. collected and analyzed SAXS data. S.Z., D.R.S., and S.H.S. designed calculations. S.Z. and D.R.S. performed the calculations. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Supplemental information is available in the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Li Y, Breaker RR. Kinetics of RNA degradation by specific base catalysis of transesterification involving the 2′-hydroxyl group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:5364–5372. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soukup GA, Breaker RR. Relationship between internucleotide linkage geometry and the stability of RNA. RNA. 1999;5:1308–1325. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emilsson GM, Nakamura S, Roth A, Breaker RR. Ribozyme speed limits. RNA. 2003;9:907–918. doi: 10.1261/rna.5680603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fersht A. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cech TR, Zaug AJ, Grabowski PJ. In vitro splicing of the ribosomal RNA precursor of Tetrahymena: Involvement of a guanosine nucleotide in the excision of the intervening sequence. Cell. 1981;27:487–496. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viladoms J, Scott LG, Fedor MJ. An active-site guanine participates in glmS ribozyme catalysis in its protonated state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18388–18396. doi: 10.1021/ja207426j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soukup JK. Chapter five - The structural and functional uniqueness of the glmS ribozyme. In: Soukup GA, editor. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Vol. 120. Academic Press; 2013. pp. 173–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang S, et al. Role of the active site guanine in the glmS ribozyme self-cleavage mechanism: quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical free energy simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:784–798. doi: 10.1021/ja510387y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein DJ, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Structural basis of glmS ribozyme activation by glucosamine-6-phosphate. Science. 2006;313:1752–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.1129666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochrane JC, Lipchock SV, Strobel SA. Structural investigation of the glmS ribozyme bound to its catalytic cofactor. Chem. Biol. 2007;14:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viladoms J, Fedor MJ. The glmS ribozyme cofactor is a general acid-base catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19043–19049. doi: 10.1021/ja307021f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein DJ, Wilkinson SR, Been MD, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Requirement of helix P2.2 and nucleotide G1 for positioning the cleavage site and cofactor of the glmS ribozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;373:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uhlenbeck OC. Keeping RNA happy. RNA. 1995;1:4–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chadalavada DM, Senchak SE, Bevilacqua PC. The folding pathway of the genomic hepatitis delta virus ribozyme is dominated by slow folding of the pseudoknots. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:559–575. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown TS, Chadalavada DM, Bevilacqua PC. Design of a highly reactive HDV ribozyme sequence uncovers facilitation of RNA folding by alternative pairings and physiological ionic strength. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;341:695–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth A, Nahvi A, Lee M, Jona I, Breaker RR. Characteristics of the glmS ribozyme suggest only structural roles for divalent metal ions. RNA. 2006;12:607–619. doi: 10.1261/rna.2266506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frederiksen JK, Piccirilli JA. Identification of catalytic metal ion ligands in ribozymes. Methods. 2009;49:148–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klawuhn K, Jansen JA, Souchek J, Soukup GA, Soukup JK. Analysis of metal ion dependence in glmS ribozyme self-cleavage and coenzyme binding. Chem Bio Chem. 2010;11:2567–2571. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks KM, Hampel KJ. Rapid steps in the glmS ribozyme catalytic pathway: cation and ligand requirements. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2424–2433. doi: 10.1021/bi101842u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray JB, Seyhan AA, Walter NG, Burke JM, Scott WG. The hammerhead, hairpin and VS ribozymes are catalytically proficient in monovalent cations alone. Chem. Biol. 1998;5:587–595. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrotta AT, Been MD. HDV ribozyme activity in monovalent cations. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11357–11365. doi: 10.1021/bi061215+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frederiksen JK, Li N-S, Das R, Herschlag D, Piccirilli JA. Metal-ion rescue revisited: biochemical detection of site-bound metal ions important for RNA folding. RNA. 2012;18:1123–1141. doi: 10.1261/rna.028738.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hampel KJ, Tinsley MM. Evidence for preorganization of the glmS ribozyme ligand binding pocket. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7861–7871. doi: 10.1021/bi060337z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thaplyal P, Ganguly A, Hammes-Schiffer S, Bevilacqua PC. Inverse thio effects in the hepatitis delta virus ribozyme reveal that the reaction pathway is controlled by metal ion charge density. Biochemistry. 2015;54:2160–2175. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeRose VJ. Metal ion binding to catalytic RNA molecules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:317–324. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson-Buck AE, McDowell SE, Walter NG. Metal ions: supporting actors in the playbook of small ribozymes. Met. Ions. Life Sci. 2011;9:175–196. doi: 10.1039/9781849732512-00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bevilacqua PC, Yajima R. Nucleobase catalysis in ribozyme mechanism. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cochrane JC, Lipchock SV, Smith KD, Strobel SA. Structural and chemical basis for glucosamine 6-phosphate binding and activation of the glmS ribozyme. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3239–3246. doi: 10.1021/bi802069p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooks KM, Hampel KJ. A rate-limiting conformational step in the catalytic pathway of the glmS ribozyme. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5669–5678. doi: 10.1021/bi900183r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott EC, Uhlenbeck OC. A re-investigation of the thio effect at the hammerhead cleavage site. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:479–484. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshida A, Sun S, Piccirilli JA. A new metal ion interaction in the Tetrahymena ribozyme reaction revealed by double sulfur substitution. Nature Structural Biology. 1999;6:318. doi: 10.1038/7551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward WL, DeRose VJ. Ground-state coordination of a catalytic metal to the scissile phosphate of a tertiary-stabilized Hammerhead ribozyme. RNA. 2012;18:16–23. doi: 10.1261/rna.030239.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jencks WP. Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology. New York: Dover Publications, Inc; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang S, et al. Assessing the potential effects of active site Mg2+ ions in the glmS ribozyme- cofactor complex. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016;7:3984–3988. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b01854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau MWL, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. An in vitro evolved glmS ribozyme has the wild-type fold but loses coenzyme dependence. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:805–810. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chinnapen DJ-F, Sen D. A deoxyribozyme that harnesses light to repair thymine dimers in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:65–69. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305943101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cernak P, Sen D. A thiamin-utilizing ribozyme decarboxylates a pyruvate-like substrate. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:971–977. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poon LCH, et al. Guanine-rich RNAs and DNAs that bind heme robustly catalyze oxygen transfer reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1877–1884. doi: 10.1021/ja108571a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Acerbo AS, Cook MJ, Gillilan RE. Upgrade of MacCHESS facility for X-ray scattering of biological macromolecules in solution. J. Synchrotron. Radiat. 2015;22:180–186. doi: 10.1107/S1600577514020360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skou S, Gillilan RE, Ando N. Synchrotron-based small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) of proteins in solution. Nat. Protoc. 2014;9:1727–1739. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen SS, et al. BioXTAS RAW, a software program for high-throughput automated small-angle X-ray scattering data reduction and preliminary analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009;42:959–964. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petoukhov MV, et al. New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012;45:342–350. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. San Carlos: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rambo RP, Tainer JA. Improving small-angle X-ray scattering data for structural analyses of the RNA world. RNA. 2010;16:638–646. doi: 10.1261/rna.1946310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lipfert J, Herschlag D, Doniach S. Riboswitch conformations revealed by small-angle X-ray scattering. In: Serganov A, editor. Riboswitches: Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2009. pp. 141–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.AMBER 14. San Francisco: University of California; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yildirim I, Stern HA, Kennedy SD, Tubbs JD, Turner DH. Reparameterization of RNA % Torsion Parameters for the AMBER Force Field and Comparison to NMR Spectra for Cytidine and Uridine. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:1520–1531. doi: 10.1021/ct900604a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allnér O, Nilsson L, Villa A. Magnesium ion-water coordination and exchange in biomolecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:1493–1502. doi: 10.1021/ct3000734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.E W, Ren W, Vanden-Eijnden E. Finite temperature string method for the study of rare events. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:6688–6693. doi: 10.1021/jp0455430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Torrie GM, Valleau JP. Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: Umbrella sampling. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:187–199. [Google Scholar]