Abstract

Increased levels of peripheral inflammatory markers, including C-Reactive Protein (CRP), are associated with increased risk for depression, anxiety, and suicidality. The brain mechanisms that may underlie the association between peripheral inflammation and internalizing problems remain to be determined. The present study examines associations between peripheral CRP concentrations and threat-related amygdala activity, a neural biomarker of depression and anxiety risk, in a sample of 172 young adult undergraduate students. Participants underwent functional MRI scanning while performing an emotional face matching task to obtain a measure of threat-related amygdala activity to angry and fearful faces; CRP concentrations were assayed from dried blood spots. Results indicated a significant interaction between CRP and sex: in men, but not women, higher CRP was associated with higher threat-related amygdala activity. These results add to the literature finding associations between systemic levels of inflammation and brain function and suggest that threat-related amygdala activity may serve as a potential pathway through which heightened chronic inflammation may increase risk for mood and anxiety problems.

Keywords: Amygdala, C-Reactive Protein, Depression, Anxiety, Inflammation

Introduction

Higher chronic inflammation is found in patients with major depression and anxiety disorders and is associated with increased risk for suicidality (Batty et al., 2016; Howren et al., 2009; Passos et al., 2015; Valkanova et al., 2013). The brain mechanisms through which inflammation may influence risk for mood-related problems remain to be determined. Our research in the Duke Neurogenetics Study (DNS) sample has demonstrated that heightened threat-related amygdala activity prospectively predicts increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in response to stress (Swartz et al., 2015), suggesting this is a potential pathway through which higher peripheral inflammation may increase risk for the future emergence of internalizing problems.

Indeed, prior research has suggested that heightened inflammation may increase the sensitivity of the amygdala to social threat. For instance, stimulating the immune system through administration of a low-dose endotoxin results in increased amygdala activity to socially threatening stimuli (Inagaki et al., 2012). Moreover, increases in interleukin-6 induced by a social stressor task are associated with greater threat-related amygdala activity (Muscatell et al., 2015). In the DNS, we have found that common variation in a gene associated with the inflammatory response predicts individual differences in amygdala activity. Specifically, a haplotype associated with increased expression of interleukin-18, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, is associated with increased threat-related centromedial amygdala activity in women (Swartz et al., 2016). In a different sample, a genetic variant in the gene encoding Interferon γ was shown to interact with early life stress to predict increased amygdala activity to emotional faces in a sample of healthy adults (Redlich et al., 2015).

In the current study, we sought to extend prior work examining the association between threat-related amygdala activity and experimentally-induced inflammation by examining naturally occurring variability in peripheral inflammation, as indexed by C-Reactive Protein (CRP), and variability in threat-related amygdala activity in a subset of healthy young adults from the DNS. Moreover, based on prior work that has demonstrated sex differences in these pathways (Moieni et al., 2015; Swartz et al., 2016), we also tested an interaction with sex to determine whether the association between CRP and threat-related amygdala activity differed between men and women.

Material and Methods

Participants included 174 undergraduate students ages 18 to 22 recruited as part of the ongoing Duke Neurogenetics Study (DNS) who had provided a blood sample and had fMRI data meeting all quality control criteria. This sample is smaller than in previously published DNS research because it includes only the subset of participants from whom we collected a dried blood spot for assays of CRP. Procedures were approved by the Duke University Medical Center and participants provided informed consent before study initiation. Full details on recruitment procedures and exclusion criteria have been reported in previous DNS papers (Prather et al., 2013; Swartz et al., 2015; Swartz et al., 2016). As described below, one participant was excluded from analyses due to an extreme value for CRP and one participant was missing data for a covariate. The remaining 172 participants were included in all analyses (Table 1). Sixty percent of participants were female; 55% self-reported as European American, 24% Asian, 9% African American, 1% Native American, 9% bi- or multi-racial, and 2% other race. Twenty-three percent of participants had a past or present DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis assessed with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) and Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV subtests (First et al., 1996). The most common diagnoses (including comorbid diagnoses) were alcohol abuse or dependence (n=21), marijuana abuse or dependence (n=6), generalized anxiety disorder (n=6), and major depressive disorder (n=5).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Men (n=69) Mean (SD) |

Women (n=103) Mean (SD) |

Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19.9 (1.3) | 19.6 (1.3) | t(170)=1.83, p=.07 |

| Time of scan | 12.2 (2.4) | 12.4 (2.5) | t(170)=−.62, p=.54 |

| BMI | 24.2 (3.3) | 23.4 (3.5) | t(170)=1.57, p=.12 |

| CRP (natural log transformed) |

−.62 (1.1) | −.25 (1.1) | t(170)=−2.26, p=.03 |

|

| |||

| Number (%) | Number (%) | ||

|

| |||

| DSM-IV diagnosis | 22 (32%) | 17 (17%) | χ2(1)=5.57, p=.02 |

| European American | 45 (65%) | 49 (48%) | χ2(1)=5.19, p=.02 |

| Asian | 16 (23%) | 26 (25%) | χ2(1)=.09, p=.76 |

| African American | 2 (3%) | 14 (14%) | χ2(1)=5.60, p=.02 |

Note: Time of scan was entered in military hours and ranged from 8.00 (8:00) to 17.5 (17:30); BMI=Body Mass Index; CRP=C-reactive protein in mg/L.

Participants underwent functional MRI (fMRI) while completing an emotional face processing task. Full details on the task, data acquisition, data pre-processing, and quality control are reported online at https://www.haririlab.com/methods/amygdala.html. Individual-level contrast maps were submitted to group-level analyses to identify a main effect of task for the contrast of Fearful and Angry Faces > Shapes at p<.05 family-wise error corrected for the search region of the left and right amygdala as defined by the Automated Anatomical Labeling atlas. Mean contrast values for left and right amygdala activity were extracted for each participant from the functional clusters that were significantly activated to the task.

CRP was assayed from dried blood spots at the Laboratory for Human Biology Research at Northwestern University following previously published methods (Mcdade et al., 2012). CRP values were natural log transformed; data from one participant with an extreme value >12 times the standard deviation of the mean was excluded from the current analyses. Our analysis controlled for multiple variables that may impact either CRP concentrations or amygdala activity including age, sex, race (with three dummy-coded variables for European American, African American, and Asian groups), body mass index (BMI), presence of a psychiatric diagnosis (coded as 0 = no psychiatric diagnosis and 1 = past or present psychiatric diagnosis), and time of day of the scan. One participant was missing data for BMI and thus was excluded from the present analyses.

All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS v23 software. The association between peripheral CRP concentrations and threat-related amygdala activity was tested using the general linear model, including all covariates described above. Based on our prior research (Swartz et al., 2016), we also modeled a CRP × sex interaction to determine if the association between CRP and threat-related amygdala activity differed for men and women. Because we had two dependent variables (left and right threat-related amygdala activity), we applied a false discovery rate (FDR) correction to correct for two comparisons.

Results

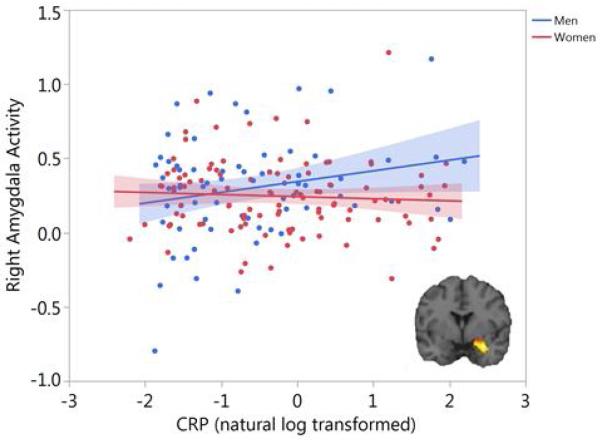

The main effect of the task (Fearful and Angry Faces > Shapes) elicited significant activity in the left, t(171)=12.73, p-corrected<.001, and right amygdala, t(171)=15.89, p-corrected<.001. While there was no significant association between amygdala activity and CRP concentrations across all participants, there was a significant interaction between CRP and sex for right threat-related amygdala activity, F(1,161)=5.37, p=.02, FDR-corrected p=.04, partial η2=.03. As shown in Figure 1, there was a significant positive association between CRP and amygdala activity in men, F(1,60)=4.95, p=.03, partial η2=.08, but not in women (p=.40). Results remained significant when winsorizing extreme values to +/−3 SD of the mean. There was no significant CRP × sex interaction, F(1,161)=2.16, p=.14, nor main effect of CRP, F(1,161)=1.55, p=.21, for left threat-related amygdala activity.

Figure 1. CRP is associated with threat-related amygdala activity in men but not women.

A functional cluster within the right amygdala region of interest was identified at p<.05 family-wise error corrected for the contrast of Fearful and Angry Faces > Shapes (inset). Mean contrast values were extracted from this functional cluster and are plotted as a function of CRP (natural log transformed) and sex. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Having found an effect for right threat-related amygdala activity to fearful and angry facial expressions, we conducted post hoc analyses to examine whether this effect was driven by one type of facial expression. These post hoc analyses indicated that the CRP × sex interaction was significant for right amygdala activity to angry facial expressions, F(1,161)=4.49, p=.04, partial η2=.03, but not fearful facial expressions, F(1,161)=1.06, p=.30, partial η2=.01, suggesting that effects were largely driven by amygdala activity to the angry facial expressions.

We also re-ran analyses excluding participants with a past or present psychiatric diagnosis. The CRP × sex interaction remained significant for right threat-related amygdala activity, F(1,123)=7.99, p=.01, with a significant association between CRP and amygdala activity in men, F(1,40)=7.59, p=.01, but not women. Additionally, within this subset of participants, the CRP × sex interaction was significant for left threat-related amygdala activity, F(1,123)=7.52, p=.01, again with only men evidencing a positive association between CRP and amygdala activity, F(1,40)=6.50, p=.02. Post hoc analyses also indicated that effects were more strongly driven by amygdala activity to angry faces, with significant associations between CRP and left and right amygdala activity to angry faces but not fearful faces.

Discussion

Here we report an association between naturally occurring variability in peripheral CRP concentrations and threat-related amygdala activity. Specifically, we report that higher peripheral CRP concentrations are associated with increased right threat-related amygdala activity in men but not women. Though these effects were observed with amygdala activity for the contrast of threatening (fearful and angry) faces versus control, post hoc analyses indicated that effects were more strongly driven by amygdala activity to angry facial expressions.

Further research is needed to test whether the observed specificity to men replicates across different samples and age groups, as this effect was not hypothesized a priori. Our prior research has found effects of genetic polymorphisms in inflammatory pathways on threat-related amygdala activity specific to women (Swartz et al., 2016). Administration of low-dose endotoxin also results in greater increases in depressed mood for women compared to men (Moieni et al., 2015). Generally, however, sex differences in the association between inflammation and internalizing problems have not always been consistent, with other studies finding a positive association between CRP levels and anxiety symptoms or disorders in men but not women (Liukkonen et al., 2011; Vogelzangs et al., 2013). Therefore, it is possible that the pathway suggested here, namely the positive association between CRP levels and amygdala activity, may be a risk pathway that plays a larger role in the etiology of internalizing problems in men compared to women. However, further research is needed before drawing strong conclusions regarding sex differences in these pathways, as differences in sample composition, as well as indices of inflammation (i.e., functional genetic polymorphism vs. peripheral CRP), may have contributed to these findings and the divergent results compared with prior research. Indeed, a limitation of our study was that the male and female groups differed in several key characteristics, including the percentage of participants with a DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis and the racial composition of the groups. Although we controlled for these as covariates in our analyses, we cannot rule out the possibility that these or other differences in sample composition may have contributed to the finding of a significant association between CRP and amygdala activity in men but not women. Therefore, further research in the future with larger sample sizes is needed to confirm the presence of these sex differences.

We also observed that effects were more strongly driven by amygdala activity to angry faces compared to fearful faces, although the effects were in the same positive direction for both conditions. Prior research suggests that angry faces with eye gaze directed at the participant may represent a more overt signal of interpersonal threat whereas fearful faces with directed eye gaze represent a more ambiguous signal of potential threat, as the source of threat causing the fearful expression is unknown (Adams et al., 2003). Therefore, it is possible that inflammation is more strongly associated with amygdala activity to clear rather than more ambiguous signals of threat, though this was not a predicted result and requires replication.

Additionally, effects were observed in the right amygdala when analyzing the full sample of participants and the subset of the sample without psychiatric diagnoses, whereas effects for the left amygdala were only observed for the subset of the sample without psychiatric diagnoses. One explanation for the more robust effects for the right amygdala may involve laterality differences in habituation. For instance, prior research suggests the right amygdala may be more involved in rapid stimulus detection whereas the left amygdala is more involved in sustained stimulus processing, as there is stronger habituation to emotional faces in the right compared to the left amygdala (Wright et al., 2001). Therefore, inflammation may be more strongly associated with this rapid threat detection process, although here too replication is required.

Overall, our current study extends prior research demonstrating associations between experimentally-induced inflammation and threat-related amygdala activity by reporting an association between naturally-occurring variation in inflammation and this brain response. Our current findings further suggest that this pattern of altered amygdala activity represents a potential pathway through which heightened chronic inflammation may increase risk for mood and anxiety problems in men specifically.

Highlights.

Association between peripheral C-Reactive Protein and amygdala activity is tested.

In men, but not women, higher CRP is associated with higher amygdala activity.

Amygdala activity is a potential pathway linking inflammation to internalizing risk.

Acknowledgments

JRS conducted the statistical analyses, interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript; AAP designed the acquisition of CRP data; ARH designed the Duke Neurogenetics Study; all authors edited and approved the final manuscript. The Duke Neurogenetics Study is supported by Duke University and NIH grant DA033369. JRS was supported by Prop. 63, the Mental Health Services Act and the Behavioral Health Center of Excellence at UC Davis. AAP was supported by NIH grant K08HL112961 and ARH was supported by NIH grants R01DA033369 and R01AG049789. The authors would like to thank Spenser Radtke, B.S., Duke University, for assistance with data collection and Annchen Knodt, M.S., Duke University, for assistance with fMRI data analysis.

Footnotes

AAP has received compensation for consulting from Posit Science on a project unrelated to this research; JRS and ARH declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams RB, Jr., Gordon HL, Baird AA, Ambady N, Kleck RE. Effects of gaze on amygdala sensitivity to anger and fear faces. Science. 2003;300:1536. doi: 10.1126/science.1082244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty GD, Bell S, Stamatakis E, Kivimaki M. Association of systemic inflammation with risk of completed suicide in the general population. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:2014–2016. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBM. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Research Version, Non-Patient Edition ed. New York Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-Reactive Protein, IL-1, and IL-6: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:171–186. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki TK, Muscatell KA, Irwin MR, Cole SW, Eisenberger NI. Inflammation selectively enhances amygdala activity to socially threatening images. NeuroImage. 2012;59:3222–3226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liukkonen T, Rasanen P, Jokelainen J, Leinonen M, Jarvelin MR, Meyer-Rochow VB, Timonen M. The association between anxiety and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels: Results from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort Study. European Psychiatry. 2011;26:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdade TW, Tallman PS, Madimenos FC, Liebert MA, Cepon TJ, Sugiyama LS, Snodgrass JJ. Analysis of variability of high sensitivity C-reactive protein in lowland Ecuador reveals no evidence of chronic low-grade inflammation. American Journal of Human Biology. 2012;24:675–681. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moieni M, Irwin MR, Jevtic I, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Eisenberger NI. Sex differences in depressive and socioemotional responses to an inflammatory challenge: Implications for sex differences in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:1709–1716. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscatell KA, Dedovic K, Slavich GM, Jarcho MR, Breen EC, Bower JE. Greater amygdala activity and dorsomedial prefrontal-amygdala coupling are associated with enhanced inflammatory responses to stress. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;43:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.06.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos IC, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Costa LG, Kunz M, Brietzke E, Quevedo J, Salum G, Magalhaes PV, Kapczinski F, Kaver-Sant'Anna M. Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:1002–1012. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather AA, Bogdan R, Hariri AR. Impact of sleep quality on amygdala reactivity, negative affect, and perceived stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2013;75:350–358. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828ef15b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redlich R, Stacey D, Opel N, Grotegerd D, Dohm K, Kugel H, Heindel W, Arolt V, Baune BT, Dannlowski U. Evidence of an IFN-γ by early life stress interaction in the regulation of amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Knodt AR, Radtke SR, Hariri AR. A neural biomarker of psychological vulnerability to future life stress. Neuron. 2015;85:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JR, Prather AA, Di Iorio CR, Bogdan R, Hariri AR. A functional interleukin-18 haplotype predicts depression and anxiety through increased threat-related amygdala reactivity in women but not men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;42:419–426. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkanova V, Ebmeier KP, Allan CL. CRP, IL-6 and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;150:736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelzangs N, Beekman ATF, de Jonge P, Penninx BWJH. Anxiety disorders and inflammation in a large adult cohort. Translational Psychiatry. 2013;3:e249. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CI, Fischer H, Whalen PJ, McInerney SC, Shin LM, Rauch SL. Differential prefrontal cortex and amygdala habituation to repeatedly presented emotional stimuli. NeuroReport. 2001;12:379–383. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200102120-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]