Abstract

Our objective was to use a community-based participatory research approach to identify and compare barriers to healthcare experienced by autistic adults and adults with and without other disabilities. To do so, we developed a Long- and Short-Form instrument to assess barriers in clinical and research settings. Using the Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Long Form, we surveyed 437 participants (209 autistic, 55 non-autistic with disabilities, and 173 non-autistic without disabilities). Autistic participants selected different and greater barriers to healthcare, particularly in areas related to emotional regulation, patient-provider communication, sensory sensitivity, and healthcare navigation. Top barriers were fear or anxiety (35% (n = 74)), not being able to process information fast enough to participate in real-time discussions about healthcare (32% (n = 67)), concern about cost (30% (n = 62)), facilities causing sensory issues 30% ((n = 62)), and difficulty communicating with providers (29% (n = 61)). The Long Form instrument exhibited good content and construct validity. The items combined to create the Short Form had predominantly high levels of correlation (range 0.2–0.8, p < 0.001) and showed responsiveness to change. We recommend healthcare providers, clinics, and others working in healthcare settings to be aware of these barriers, and urge more intervention research to explore means for removing them.

Keywords: accessiblity, adults, autism spectrum disorders, community-based participatory research, health services, instrument development

Background

Adults with disabilities experience significant healthcare disparities (Krahn et al., 2015; Lagu et al., 2014; Okumura et al., 2013; Vohra et al., 2016). Contributing to these disparities are individual and systemic barriers to access, such as physically inaccessible facilities, discriminatory provider attitudes, inadequate caregiver support, and lack of clinician training or experience (Drainoni et al., 2006; Kirschner et al., 2007; Mudrick et al., 2012; Scheer et al., 2003; Weiss et al., 2016; Zerbo et al., 2015). Barriers to access can lead to complex, interlinked consequences, such as increased physical and mental-health concerns, decreased independence, and increased economic hardship (Neri and Kroll, 2003). Furthermore, the relationship among barriers can be complex, with multiple barriers interacting with each other, making it more difficult to find effective solutions (Drainoni et al., 2006). Recognition of the need to reduce barriers to healthcare access for people with disabilities has improved in the United States in recent years and is supported via policy such as the Americans with Disabilities Act. However, issues are far from resolved.

Less is known about barriers to healthcare specific to autistic people, particularly in how those barriers may differ from those experienced by people with other types of disabilities or that are commonly addressed in modern healthcare settings (e.g. ramp access to buildings and elevators). Autistic people do experience significant disparities in life expectancy (Hirvikoski et al., 2016), as well as in healthcare usage, satisfaction, and self-efficacy (Nicolaidis et al., 2013). Our prior qualitative work with autistic adults suggests that their barriers to healthcare may both overlap and be different from those identified as problematic for people experiencing other types of disabilities (Nicolaidis et al., 2015). We also know that there is no “one size fits all” solution for accommodations, for example, providing accessible medical equipment, such as adjustable tables, might improve access to physical exams for patients with mobility impairments but would do little to remove language-related barriers for patients with communication impairments. It is necessary to learn directly from people who experience a particular type of impairment to understand both barriers and their solutions (Jaeger, 2008; Kelly et al., 2009).

In order to improve healthcare for autistic adults, interventions targeting autism-specific barriers are needed. This requires an understanding of autism-specific barriers, which in turn requires instruments that can evaluate and assess both autism-specific and general barriers to health-care. To date, national surveys have tended to focus on access barriers to healthcare for people with disabilities in general and have not included autism-specific items (e.g. 2010 GAP Survey, National Survey of Children’s Health). Smaller studies have focused only on a narrow subset of domains (e.g. economic barriers) or populations (e.g. only individuals receiving government insurance; Henning-Smith, 2013). A comprehensive, validated measure with autism-specific items is currently lacking.

Our objective was to use a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to identify and compare barriers to healthcare experienced by autistic adults and adults with and without other disabilities. We also used results from this study to develop a Long- and Short-Form instrument to assess barriers in clinical and research settings.

Methods

CBPR approach

The Academic Autism Spectrum Partnership in Research and Education (AASPIRE) is a collaboration between autistic individuals, family members, health and disability services professionals, and academic scientists. We use a CBPR approach to conduct research that addresses the priorities of the autistic community. CBPR is a type of action research that emphasizes community as a unit of identity, promotes equitable collaboration between academic and community partners, focuses on research for action, and adheres to the nine principles of CBPR (Israel et al., 2005; Nicolaidis and Raymaker, 2015). Academic and community team members serve as equal partners in all phases of the research process. Further information about our collaboration processes can be found elsewhere (Nicolaidis et al., 2011).

Setting, participants, and recruitment

In this analysis, we used data from an online healthcare survey of autistic and non-autistic adults. Details about the survey methods are presented elsewhere (Nicolaidis et al., 2013). Briefly, in 2009–2010, we recruited participants from a national convenience sample of Internet users who completed the Gateway Survey, an online registration system for research projects committed to inclusion, respect, accessibility, and community relevance (Nicolaidis et al., 2013). From registrants, we invited US residents who are 18 and older and who are identified as being on the autism spectrum. We then matched those participants by age and sex with non-autistic adults. To increase representation of people with disabilities for comparison, we over-sampled non-autistic individuals who identified as having a disability and/or answered affirmative to at least one of the six US census items related to disability (United States Census Bureau, 2016). We emailed participants a link to the online survey, which they accessed via their Gateway Project account. Participants received three reminder emails, each 1 week apart, until they either completed the survey or 4 weeks had passed.

Instrument development

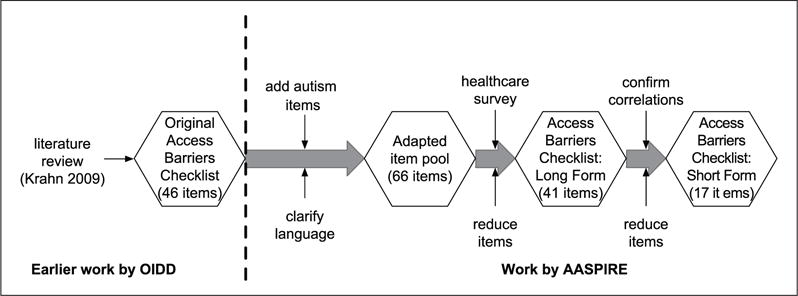

Figure 1 outlines the steps used to develop the Long and Short Forms of the Barriers to Healthcare Checklist.

Figure 1.

Instrument development.

Prior to conducing the survey, we adapted the 46-item “Access Barriers Checklist: Advocates” instrument, a cross-disability measure developed by the Oregon Institute on Development and Disability based on their systematic literature review (Rehabilitation Research Center on Health and Wellness for Persons with Long-term Disabilities, 2008). The items—yes/no checklists—were organized under the categories of transportation; availability and access of service or system; insurance; access and accommodation within facilities; social, family, and caregiver support; and individual (e.g. finding the medical system too confusing or fear). We felt many of the items had good face validity, but we were concerned that the language might not be accessible to some autistic individuals and that the items did not address some important autism-related barriers. As a group, the AASPIRE team adapted the items to make them more accessible to autistic participants by clarifying language or sentence structure and adding pop-up definitions for difficult words. We also removed redundant items, added items we felt were important autism-specific barriers—such as sensory discomforts, difficulty identifying symptoms, or concerns about melt-downs—and replaced the single item on communication with a new, more detailed, section of communication-related barriers. We also added “other” options in each section for barriers not listed. The final instrument included in the healthcare survey had 60 potential barriers, as well as six options for “other” (one per category: transportation and access to services; insurance; access and accommodation within facilities; social, family, and caregiver support; individual level; communication).

After data collection, we reduced the pool of 66 barrier items on our healthcare survey to the 41 barriers that were endorsed by 10% or more of participants in any of the three groups (i.e. those items that presented barriers to a non-trivial proportion of participants). To aid with clarity of data analysis and presentation, we qualitatively sorted the 41 barriers into semantically related categories: (1) emotional, (2) executive function, (3) healthcare navigation, (4) provider attitudes, (5) patient-provider communication, (6) sensory, (7) socio-economic, (8) support, and (9) waiting. We consider these 41 items to be the “Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Long Form” and present results for these items here.

We also wished to create a Short Form version that would be more practical to use in clinical or research settings. We combined functionally redundant items; for example, “Transportation costs too much,” and “I live in rural areas or the doctor’s office is too far away” became, “I do not have a way to get to my doctor’s office.” We also combined items at a low level of granularity into a higher level of granularity or dropped lower granularity items in favor of higher granularity ones; for example, separate items about sensory issues in facilities, sensory issues affecting communication, and sensory issues impacting tests and exams became, “Sensory discomforts (for example, the lights, smells, or sounds) get in the way of my healthcare.” We collapsed some related items into single items; for example, separate items about “fear and anxiety,” “embarrassment,” and “frustration or anger” became a single item “Fear, anxiety, embarrassment, or frustration keeps me from getting primary care.” The final items—the Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Short Form—are shown with the original items they were derived from in Table 1. We also added an “other: write in” option.

Table 1.

Item-development Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Long Form and Short Form.

| Long-Form item | Rationale | Correlation | Short-Form item |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional | |||

| Fear or anxiety keeps me from getting primary care Embarrassment keeps me from getting primary care I worry that the stress of interacting with the healthcare system will cause me to lose control of myself (e.g. melt down, shut down, freak out) Frustration or anger keeps me from getting primary care Lack of confidence keeps me from getting primary care Fatigue or pain keeps me from getting primary care |

Higher level item includes lower level examples and/or items collapsed into a single sentence | Range: 0.2–0.6 all p ≤ 0.001 | Fear, anxiety, embarrassment, or frustration keeps me from getting primary care |

| 2. Executive function | |||

| I have trouble following up on care (e.g. going to pharmacy, taking prescribed drugs at the right time, or making a follow-up appointment) I often miss appointments due to memory problems |

Higher level item includes lower level examples | 0.4 p < 0.0001 |

I have trouble following up on care (e.g. going to pharmacy, taking prescribed drugs at the right time, or making a follow-up appointment) |

| I have trouble following medical instructions in the way they are presented to me I have difficulty understanding how to translate medical information into concrete steps that I can take to improve my health |

Items functionally similar; selected clearly worded one | 0.3 p < 0.0001 |

I have difficulty understanding how to translate medical information into concrete steps that I can take to improve my health |

| 3. Healthcare navigation | |||

| I don’t understand the healthcare system or I find it too hard to work through (e.g. managed care, billing system) | Simplified language | NA | I don’t understand the healthcare system |

| I find it too hard to seek primary care or follow-up with primary care | Simplified language | NA | It is too difficult to make appointments |

| I have problems filling out paperwork | No changes | NA | I have problems filling out paperwork |

| 4. Provider attitudes | |||

| My behaviors are misinterpreted by my provider or the staff | No changes | NA | My behaviors are misinterpreted by my provider or the staff |

| My providers or the staff do not believe me when I tell them that new symptoms I experience are not related to an existing condition or disability | Higher level item includes lower level examples | 0.4 p < 0.0001 |

My providers or the staff do not take my communications seriously |

| My providers or the staff do not take my communications seriously | |||

| My providers or the staff are unwilling to communicate with me in the mode I’ve specified (e.g. writing down instructions instead of saying them out loud) | Higher level item includes lower level examples | 0.2 p = 0.0002 |

I cannot find a healthcare provider who will accommodate my needs |

| I cannot find a provider who will accommodate my need | |||

| My providers or the staff do not include me in discussions about my health | No changes | NA | My providers or the staff do not include me in discussions about my health |

| 5. Patient-provider communication | |||

| I cannot process information fast enough to participate in real-time discussions about healthcare | Higher level item includes lower level examples | Range: 0.5–0.3 all p < 0.0001 | Communication with my healthcare provider or the staff is too difficult |

| I have difficulty communicating with my doctors or the staff | |||

| I have trouble following spoken directions | |||

| Appointments are too short to accommodate my communication needs | |||

| I have difficulty moving or communicating effectively when in crisis | |||

| When I experience pain and/or other physical symptoms, I have difficulties identifying them and reporting them to my healthcare provider | No changes | NA | When I experience pain and/or other physical symptoms, I have difficulties identifying them and reporting them to my healthcare provider |

| 6. Sensory | |||

| Healthcare facilities cause me sensory discomfort (e.g. the lights, smells, or sounds make visits uncomfortable) Sensory issues (e.g. sensitivity to light, sounds, or smells) make it difficult for me to communicate well in healthcare settings |

Higher level item includes lower level examples | Range: 0.7–0.8 all p < 0.0001 | Sensory discomforts (e.g. the lights, smells, or sounds) get in the way of my healthcare |

| Sensory issues (e.g. sensitivity to light, sounds, or smells) make tests, screenings, and medical exams difficult or impossible | |||

| 7. Socio-economic | |||

| Concern about the cost of care keeps me from getting primary care I don’t have insurance coverage My insurance coverage does not cover medications, or the co-payments are too high My insurance coverage does not cover care coordination services I have trouble getting reimbursements for atypical treatments (e.g. pool therapy) |

“Concerns about insurance” includes example concerns, added concern about cost as another financial barriers | Correlations between concern regarding cost, no coverage, insufficient coverage: range: 0.2–0.4, p < 0.0004 Correlations between care coordination, insufficient coverage, atypical treatment: range: 0.2–0.3, p < 0.0002 No other correlations |

Concerns about cost or insurance coverage keep me from getting primary care |

| Transportation costs too much I live in rural areas or the doctor’s office is too far away |

Higher level item includes lower level examples | 0.3 p < 0.0001 |

I do not have a way to get to my doctor’s office |

| 8. Support | |||

| I am socially isolated I have inadequate social, family, or caregiver support I have difficulty getting personal assistance |

Higher level item includes lower level examples | Range: 0.4-0.3 p < 0.0001 | I have inadequate social, family, or caregiver support |

| 9. Waiting | |||

| I find it hard to handle the waiting room The wait in the healthcare office is too long for me |

Higher level item includes lower level examples | 0.4 p < 0.0001 |

I find it hard to handle the waiting room |

To verify our qualitative item reduction and Short Form creation process, we calculated pairwise correlations between those items we had grouped together to confirm that they were highly correlated with each other (or uncorrelated, for items for which a correlation would be counter-intuitive such as having no insurance and insurance not covering certain services).

Data analysis

We calculated summary statistics to describe participant characteristics and the proportion of groups, and between the autistic and non-autistic non-disabled (NAND) groups. We used Stata (StataCorp LP, 2013) for all analyses.

Results

Participants

Totally, 209 autistic individuals, 55 non-autistic individuals with disabilities, and 173 non-autistic individuals without disabilities completed the healthcare survey. The mean age was 40, and the majority of participants were female non-Hispanic white. The autistic and disability groups had less education, lower incomes, and lower overall self-reported health status than the NAND group. The autistic and disability groups also had a similar insurance spread (approximately 60% private and 20% government, as opposed to 81% private for the NAND group); however, 12% (n = 26) of the autistic group was uninsured compared with 4% (n = 2) of the disability group. Instead, the autistic and NAND groups had a similar proportion of uninsured participants. Mobility and sensory disabilities were more represented in the disability group, though difficulty learning/remembering was reported in similar proportion for the autistic and disability groups (50% (n = 102) and 45% (n = 25), respectively) (see Table 2: demographics).

Table 2.

Demographics for healthcare survey.

| Autistic group N = 209 |

Disability group N = 55 |

NAND group N = 173 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 37 (13) | 45 (14) | 38 (12) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 119 (57%) | 37 (69%) | 109 (63%) |

| Male | 84 (40%) | 17 (31.5%) | 64 (37%) |

| Other | 5 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 178 (86%) | 47 (85%) | 178 (86%) |

| Personal education | |||

| High school or less | 17 (8%) | 5 (9%) | 10 (6%) |

| College (but no degree) | 87 (42%) | 18 (35%) | 34 (20%) |

| Bachelors degree | 57 (28%) | 16 (31%) | 69 (40%) |

| Graduate degree | 44 (21%) | 12 (23%) | 58 (34%) |

| Health insurance | |||

| Private | 123 (59%) | 34 (62%) | 140 (81%) |

| Governmental only | 41 (20%) | 13 (24%) | 7 (4%) |

| Other | 19 (9%) | 6 (11%) | 12 (7%) |

| None | 26 (12%) | 2 (4%) | 13 (8%) |

| Required assistance from others in the past 12 months to receive healthcare | 84 (41%) | 24 (43%) | 15 (9%) |

| Disability type(s) | |||

| Vision/hearing | 18 (9%) | 7 (12%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mobility | 30 (13%) | 30 (55%) | 0 (0%) |

| Learning/remembering | 102 (50%) | 25 (45%) | 0 (0%) |

| Activities of daily living | 16 (8%) | 6 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Leaving home alone | 54 (26%) | 13 (24%) | 0 (0%) |

| Working at a job | 111 (55%) | 34 (64%) | 0 (0%) |

| Overall health status | |||

| Excellent | 20 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 33 (19%) |

| Very good | 68 (33%) | 11 (20%) | 77 (45%) |

| Good | 65 (31%) | 38 (21%) | 51 (30%) |

| Fair | 45 (22%) | 18 (32%) | 11 (6%) |

| Poor | 10 (5%) | 4 (7%) | 0 (0%) |

Psychometric properties of Barriers to Healthcare Checklist: Long and Short Forms

Content validity

We used the expertise of our community partners to help ensure content validity. The full AASPIRE team evaluated the Barriers to Healthcare Checklist instrument for completeness at all stages of its development. Additionally, participants in the healthcare survey were given an option of “other” for barriers in each section; less than 10% of participants selected the “other” option in all sections, with the exception of other insurance barriers.

Construct validity

The autistic and disability groups endorsed considerably more items than the NAND group in the healthcare study, suggesting that the items largely represent barriers specific to individuals with disabilities. Furthermore, differences between the autistic and disability groups are in alignment with the clinical criteria for autism spectrum disorders (ASD); specifically, barriers related to social communication, sensory processing, and coping with deviations from routine were endorsed by the autistic group but not by individuals with other types of disabilities.

To test whether collapsed items on the Short Form comprise highly correlated items from the item pool of 41 Long-Form barriers, we ran correlation matrices of the items in confirmatory mode. In those instances where the original items were components of the collapsed item, we confirmed predominantly high levels of correlation (range 0.2–0.8, p < 0.001). For example, the three sensory items we covered with a single higher granularity item were correlated at 0.8–0.7, p < 0.001. For collapsed items where the original items are different manifestations of the larger construct, correlation was not anticipated and was confirmed to not be occurring for mutually exclusive items. For all items, we confirmed correlations in the anticipated direction (Table 1).

Comparison of barriers to healthcare between autistic individuals and those with and without other disabilities

Similarities and differences in barriers to healthcare between the three groups are shown in Table 3. The NAND group experienced far fewer barriers to healthcare than either the autistic or the disability group. Of those items endorsed by more than 5% (i.e. presented barriers for a non-trivial proportion) of the NAND group—concern about cost; fear, anxiety, or embarrassment; insurance issues; and trouble understanding the healthcare system— none are specifically related to disability, although they may be more pronounced for people with disabilities due to additional disparities, such as employment inequity. The most highly endorsed item among the NAND group was concern about cost (16%), second was fear or anxiety (10%). No other items were selected by 10% or more of the NAND group, and only 10 items were endorsed by more than 5% of the NAND participants.

Table 3.

Comparison Barriers to Healthcare Checklist (Long Form).

| Potential barrier | Autistic group N = 209 |

Disability group N = 55 |

p autistic/disability | NAND group N = 173 |

p autistic/NAND |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional | |||||

| Fear or anxiety keeps me from getting primary care | 74 (35%) | 10 (18%)* | 0.015 | 17 (10%)* | <0.001 |

| Embarrassment keeps me from getting primary care | 54 (26%) | 7 (13%)* | 0.041 | 10 (6%)* | <0.001 |

| I worry that the stress of interacting with the healthcare system will cause me to lose control of myself (e.g. melt down, shut down, freak out) | 53 (26%) | 3 (6%)* | 0.001 | 4 (2%)* | <0.001 |

| Frustration or anger keeps me from getting primary care | 49 (23%) | 5 (9%)* | 0.019 | 6 (4%)* | <0.001 |

| Lack of confidence keeps me from getting primary care | 48 (23%) | 5 (9%)* | 0.023 | 7 (4%)* | <0.001 |

| Fatigue or pain keeps me from getting primary care | 22 (11%) | 9 (17%) | 0.227 | 2 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| 2. Executive function | |||||

| I have trouble following up on care (e.g. going to pharmacy, taking prescribed drugs at the right time, or making a follow-up appointment) | 48 (23%) | 7 (13%) | 0.098 | 6 (4%)* | <0.001 |

| I often miss appointments due to memory problems | 24 (12%) | 6 (11%) | 0.912 | 1 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| I have trouble following medical instructions in the way they are presented to me | 31 (15%) | 0 (0%)* | 0.002 | 0 (0%)* | <0.001 |

| I have difficulty understanding how to translate medical information into concrete steps that I can take to improve my health | 25 (12%) | 4 (7%) | 0.326 | 0 (0%)* | <0.001 |

| 3. Healthcare navigation | |||||

| I don’t understand the healthcare system or I find it too hard to work through (e.g. managed care, billing system) | 56 (27%) | 4 (7%)* | 0.002 | 13 (7%)* | <0.001 |

| I find it too hard to seek primary care or follow-up with primary care | 44 (21%) | 5 (9%)* | 0.043 | 7 (4%)* | <0.001 |

| I have problems filling out paperwork | 25 (12%) | 2 (4%) | 0.07 | 0 (0%)* | <0.001 |

| 4. Provider attitudes | |||||

| My behaviors are misinterpreted by my provider or the staff | 42 (20%) | 3 (6%)* | 0.01 | 2 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| My providers or the staff do not believe me when I tell them that new symptoms I experience are not related to an existing condition or disability | 23 (19%) | 9 (16%) | 0.627 | 4 (2%)* | <0.001 |

| My providers or the staff do not take my communications seriously | 31 (15%) | 4 (7%) | 0.138 | 3 (2%)* | <0.001 |

| My providers or the staff are unwilling to communicate with me in the mode I’ve specified (e.g. writing down instructions instead of saying them out loud) | 20 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 0.058 | 0 (0%)* | <0.001 |

| I cannot find a provider who will accommodate my needs | 16 (8%) | 8 (15%) | 0.114 | 0 (0%)* | <0.001 |

| 5. Patient-provider communication | |||||

| I cannot process information fast enough to participate in real-time discussions about healthcare | 67 (32%) | 4 (7%)* | <0.001 | 1 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| I have difficulty communicating with my doctors or the staff | 61 (29%) | 5 (9%)* | 0.002 | 4 (2%)* | <0.001 |

| I have trouble following spoken directions | 49 (24%) | 3 (6%)* | 0.003 | 1 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| Appointments are too short to accommodate my communication needs | 43 (21%) | 7 (13%) | 0.182 | 7 (4%)* | <0.001 |

| I have difficulty moving or communicating effectively when in crisis | 42 (20%) | 3 (6%)* | 0.01 | 1 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| When I experience pain and/or other physical symptoms, I have difficulties identifying them and reporting them to my healthcare provider | 48 (23%) | 3 (6%)* | 0.003 | 3 (2%)* | <0.001 |

| 6. Sensory | |||||

| Healthcare facilities cause me sensory discomfort (e.g. the lights, smells or sounds make visits uncomfortable) | 62 (30%) | 5 (9%)* | 0.002 | 2 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| Sensory issues (e.g. sensitivity to light, sounds, or smells) make it difficult for me to communicate well in healthcare settings | 55 (26%) | 2 (4%)* | <0.001 | 2 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| Sensory issues (e.g. sensitivity to light, sounds, or smells) make tests, screenings and medical exams difficult or impossible | 49 (24%) | 3 (6%)* | 0.003 | 2 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| 7. Socio-economic | |||||

| Concern about the cost of care keeps me from getting primary care | 62 (30%) | 15 (28%) | 0.74 | 29 (16%)* | 0.003 |

| I don’t have insurance coverage | 27 (13%) | 2 (4%) | 0.055 | 13 (7%) | 0.087 |

| My insurance coverage does not cover medications or the co-payments are too high | 25 (12%) | 9 (17%) | 0.408 | 11 (6%)* | 0.046 |

| My insurance coverage does not cover care coordination services | 21 (10%) | 5 (10%) | 0.87 | 0 (0%)* | <0.001 |

| I have trouble getting reimbursements for atypical treatments (e.g. pool therapy) | 20 (10%) | 9 (17%) | 0.134 | 3 (2%)* | 0.001 |

| Transportation costs too much | 34 (17%) | 5 (9%) | 0.171 | 2 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| I live in rural areas or the doctor’s office is too far away | 25 (12%) | 2 (4%) | 0.066 | 3 (2%)* | <0.001 |

| Co-payment is too high | 15 (07%) | 6 (11%) | 0.337 | 7 (04%) | 0.193 |

| Waiting for insurance plan approval | 13 (06%) | 7 (13%) | 0.093 | 5 (03%) | 0.128 |

| 8. Support | |||||

| I am socially isolated | 56 (26%) | 10 (18%) | 0.184 | 2 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| I have inadequate social, family, or caregiver support | 44 (21%) | 10 (18%) | 0.627 | 2 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| I have difficulty getting personal assistance | 28 (14%) | 5 (10%) | 0.384 | 1 (1%)* | <0.001 |

| 9. Waiting | |||||

| I find it hard to handle the waiting room | 43 (21%) | 4 (7%)* | 0.022 | 6 (4%)* | <0.001 |

| The wait in the healthcare office is too long for me | 38 (18%) | 7 (13%) | 0.338 | 11 (7%)* | 0.001 |

Bold indicates a statistically significant result.

While the most endorsed barriers for the disability group were also cost and fear or anxiety, the percentage endorsing each was higher than the NAND group (28% and 18%, respectively). Endorsed at the same rate as fear or anxiety were social isolation and inadequate support. The disability group endorsed considerably more barriers than the NAND group, with 34 barriers endorsed by 5% of the population or more.

Overall the autistic group showed a different pattern than the other two groups. Not only were 56 barriers endorsed by at least 5% of the population, but 23 barriers were endorsed by 20% or more. This pattern included cross-disability barriers that were part of the original measure, not just those added through the CBPR process. The top five items were endorsed by a third or more of the autistic participants: fear or anxiety (35%), can’t process information fast enough (32%), concern about cost (30%), facilities cause sensory issues (30%), and difficulty communicating with providers (29%).

In pairwise comparisons of the Long-Form items between the autistic and NAND groups, all items except lack of insurance (to be expected as both groups had a similar number of uninsured) showed statistically significant differences, with greater proportions in the autistic group. Between the autistic and disability groups statistically significant differences—again with higher proportions in the autistic group—were found for all items related to sensory sensitivity, healthcare navigation, and the individual items difficulty handling the waiting room, having behaviors misinterpreted, and trouble following medical instructions as presented. This pattern is consistent with the characteristics of ASD, which include atypical social communication, sensory processing, and deviations from routine activities (American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013). While both the autistic and disability groups experienced many disability-related barriers to healthcare access, the nature of those barriers was specific to the type of functional impairments experienced.

We found the most striking differences in the areas of communication and sensory processing. Items related to patient-provider communication were among the most endorsed by the autistic group. More than a third cited not being able to process information fast enough to participate in real-time discussions about healthcare as a barrier, and nearly a third cited difficulty communicating with the providers or staff. Both the autistic and disability groups reported that appointments were too short to accommodate communication needs (21% and 13%, respectively; compared with only 4% for NAND).

Sensory distress caused by the facilities was cited by a third of the autistic participants, and the impact of sensory distress on communication and capacity to tolerate exams and tests were endorsed by a quarter of the autistic participants. These proportions were significantly greater than both the disability and NAND groups.

Discussion

In summary, autistic adults experience many similar barriers to healthcare access as people with other types of disabilities; however, they experience them at higher rates, and also experience unique autism-specific barriers that may be less likely to be addressed in modern healthcare systems.

Autistic adults in our study experienced many of the barriers identified in studies of adults with other disabilities, such as increased socio-economic barriers, difficulty getting sufficient support, and discrimination (World Health Organization (WHO), 2011; WHO, 2013). There were also similarities between the autistic and disability groups in barriers related to executive functioning. Difficulties with planning, sequencing, and understanding complex instructions are reported by many individuals on the spectrum (Landa and Goldberg, 2005) as well as by others (e.g. those with traumatic brain injury, intellectual disability, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder). Interventions targeted toward improving healthcare access for people with disabilities more generally may also help autistic people, and existing literature and interventions related to these items may be transferrable to autistic patients.

Results also reflect the differences in barriers autistic individuals may experience due to characteristics associated with ASD; specifically, barriers related to emotional regulation, patient-provider communication, and sensory issues. It is well-known that many individuals on the autism spectrum report difficulty with emotional regulation (Mazefsky et al., 2013), that autism is a social-communication disability (APA, 2013), and that sensory differences are a core aspect of the diagnostic criteria for ASD (Crane et al., 2009). Our prior qualitative work (Nicolaidis et al., 2015) started to explore how such autism-related issues may contribute to patients’ healthcare experiences. However, no prior studies have quantitatively assessed autism-specific barriers to care—a necessary step in targeting solutions. Our findings provide an important addition to the autism literature and may help future interventions target barriers most commonly experienced by autistic adults.

In beginning substantive work to reduce barriers to healthcare for people with disabilities and thus reduce healthcare disparities, it is necessary to have instruments that are effective for both identifying barriers and assessing if barriers have been ameliorated. The Barriers to Healthcare Checklist could serve this purpose for autistic adults, while still capturing important barriers to health-care for people with other disabilities. We recently used the Short Form instrument to evaluate an intervention targeting many of the barriers identified in the healthcare study. In pre–post comparisons, we found a significant decrease in number of barriers endorsed (mean 4.07 at baseline and 2.82 at post, p < 0.001), indicating that the Short-Form instrument is responsive to change. Details of that study are presented elsewhere (Nicolaidis et al., 2016). Our instrument fills an important gap in existing psychometrically evaluated disability, and autism-specific, instrumentation for assessing barriers.

Limitations

We collected self-report data from a convenience sample of individuals with access to the Internet and the ability to complete an online survey either independently or with support. Results may not be generalizable to all people on the autism spectrum. Furthermore, the disability group in the barriers comparison had a small N compared with the autistic and NAND groups. Future work with the Barriers to Healthcare Checklist instruments in other settings, including with individuals whose circumstances would prevent them from completing an online survey, would be useful in expanding our findings.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was implemented by the US government after we completed data collection for the healthcare survey. What impact the ACA may have had since—or may yet have on—insurance-related barriers, cost-related barriers to preventive care, or on the proportion of uninsured participants is unknown.

Implications

We recommend that clinicians, disability support professionals, and policy makers be aware of the barriers to healthcare access commonly faced by individuals on the autism spectrum, and work with individuals and systems to reduce those barriers. We have developed clinician resources (Nicolaidis et al., 2014) and tools for both patients and providers (autismandhealth.org) to assist in identifying, and finding creative strategies for removing, barriers. Given the high percentage of individuals endorsing barriers to healthcare access, we strongly recommend that further interventions directly address those barriers for individuals on the autism spectrum and for others with accessibility needs. Identifying barriers is the first step in addressing them in order to reduce healthcare inequities.

We recommend healthcare providers, clinics, and others working with autistic adults in healthcare settings use the Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Long-Form or Short-Form instruments to help assess the needs of their autistic patients, and to help assess the success of interventions to remove barriers within the healthcare system. Since the measures items are independent from each other, intervention evaluators may select those items which their intervention is likely to target. The measure can be scored with a sum to indicate overall systemic barrier reduction of a system-level intervention.

We based our Long-Form instrument on the cross-disability work started by the Oregon Institute on Development and Disability (OIDD), and we expect that it can continue to be used by people with a variety of disabilities. However, just as we recognized that the checklist was missing some autism-specific barriers, it is possible that other disability groups may feel it does not capture important barriers specific to their disability. To address missing items, we recommend using a participatory approach to research, such as CBPR, which would enable members of disability communities to comment on and make recommendations directly. It is known that direct involvement is the only way to fully understand and meet accessibility needs (Jaeger, 2008; Kelly et al., 2009). Further work might see adaptations of the long and short versions of our Barriers to Healthcare Checklist to work with caregivers. We found the Barriers to Healthcare Long Form useful for identifying areas to target an intervention, and our further revised Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Short-Form useful in assessing the potential effectiveness of our intervention.

Last, more research is needed to understand how best to start removing identified barriers within the healthcare system. More intervention research is needed to explore effective means of barrier removal and to evaluate both short- and long-term outcomes with respect to improving healthcare and health for autistic people, and for others who experience access barriers to healthcare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study participants and all AASPIRE team members, past and present, for their invaluable insights. They also thank Jennifer Stevenson for her support during the early stages of this project. Finally, the authors thank the Autistic Self Advocacy Network for their help with recruitment and dissemination and for their ongoing support of our work. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Funding

AASPIRE’s work is supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant number R34MH092503; Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI) grant number UL1 RR024140 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research; Portland State University; and the Burton Blatt Institute at Syracuse University.

Appendix 1

Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Long Form

Emotional

Fear or anxiety keeps me from getting primary care.

Embarrassment keeps me from getting primary care.

I worry that the stress of interacting with the health-care system will cause me to lose control of myself (e.g. melt down, shut down, freak out).

Frustration or anger keeps me from getting primary care.

Lack of confidence keeps me from getting primary care.

Fatigue or pain keeps me from getting primary care.

Executive function

I have trouble following up on care (e.g. going to pharmacy, taking prescribed drugs at the right time, or making a follow-up appointment).

I often miss appointments due to memory problems.

I have trouble following medical instructions in the way they are presented to me.

I have difficulty understanding how to translate medical information into concrete steps that I can take to improve my health.

Healthcare navigation

I don’t understand the healthcare system or I find it too hard to work through (e.g. managed care, billing system).

I find it too hard to seek primary care or follow-up with primary care.

I have problems filling out paperwork.

Provider attitudes

My behaviors are misinterpreted by my provider or the staff.

My providers or the staff do not believe me when I tell them that new symptoms I experience are not related to an existing condition or disability.

My providers or the staff do not take my communications seriously.

My providers or the staff are unwilling to communicate with me in the mode I’ve specified (e.g. writing down instructions instead of saying them out loud).

I cannot find a provider who will accommodate my need.

My providers or the staff do not include me in discussions about my health.

Patient–Provider Communication

I cannot process information fast enough to participate in real-time discussions about healthcare.

I have difficulty communicating with my doctors or the staff.

I have trouble following spoken directions.

Appointments are too short to accommodate my communication needs.

I have difficulty moving or communicating effectively when in crisis.

When I experience pain and/or other physical symptoms, I have difficulties identifying them and reporting them to my healthcare provider.

Sensory

Healthcare facilities cause me sensory discomfort (e.g. the lights, smells, or sounds make visits uncomfortable).

Sensory issues (e.g. sensitivity to light, sounds, or smells) make it difficult for me to communicate well in healthcare settings.

Sensory issues (e.g. sensitivity to light, sounds, or smells) make tests, screenings and medical exams difficult or impossible.

Socio-economic

Concern about the cost of care keeps me from getting primary care.

I don’t have insurance coverage.

My insurance coverage does not cover medications or the co-payments are too high.

My insurance coverage does not cover care coordination services.

I have trouble getting reimbursements for atypical treatments (e.g. pool therapy).

Transportation costs too much.

I live in rural area or the doctor’s office is too far away.

Support

I am socially isolated.

I have inadequate social, family, or caregiver support.

I have difficulty getting personal assistance.

Waiting and Examination Rooms

I find it hard to handle the waiting room.

The wait in the healthcare office is too long for me.

Barriers to Healthcare Checklist–Short Form

Fear, anxiety, embarrassment, or frustration keeps me from getting primary care.

I have trouble following up on care (e.g. going to pharmacy, taking prescribed drugs at the right time, or making a follow-up appointment).

I have difficulty understanding how to translate medical information into concrete steps that I can take to improve my health.

I don’t understand the healthcare system.

It is too difficult to make appointments.

I have problems filling out paperwork.

My behaviors are misinterpreted by my provider or the staff.

My providers or the staff do not take my communications seriously.

I cannot find a healthcare provider who will accommodate my needs.

My providers or the staff do not include me in discussions about my health.

Communication with my healthcare provider or the staff is too difficult.

When I experience pain and/or other physical symptoms, I have difficulties identifying them and reporting them to my healthcare provider.

Sensory discomforts (e.g. the lights, smells, or sounds) get in the way of my healthcare.

Concerns about cost or insurance coverage keep me from getting primary care.

I do not have a way to get to my doctor’s office.

I have inadequate social, family, or caregiver support.

I find it hard to handle the waiting room.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) 5th. Washington, DC: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crane L, Goddard L, Pring L. Sensory processing in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2009;13:215–228. doi: 10.1177/1362361309103794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drainoni M-L, Lee-Hood E, Tobias C, et al. Cross-disability experiences of barriers to health-care access: consumer perspectives. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2006;17:101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith C, McAlpine D, Shippee T, et al. Delayed and unmet need for medical care among publicly insured adults with disabilities. Medical Care. 2013;51:1015–1019. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a95d65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvikoski T, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Boman M, et al. Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;208:232–238. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, et al. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Fransisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger PT. User-centered policy evaluations of Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2008;19:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B, Sloan D, Brown S, et al. Accessibility 2.0: next steps for web accessibility. Journal of Access Services. 2009;6:265–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner KL, Breslin M, Iezzoni LI. Structural impairments that limit access to health care for patients with disabilities. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:1121–1125. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn GL, Walker DK, Correa-De-Araujo R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(2 Suppl):S198–S206. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagu T, Iezzoni LI, Lindenauer PK. The axes of access–improving care for patients with disabilities. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:1847–1851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1315940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa RJ, Goldberg MC. Language, social, and executive functions in high functioning autism: a continuum of performance. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005;35:557–573. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-0001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazefsky CA, Herrington J, Siegel M, et al. The role of emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudrick NR, Breslin ML, Liang M, et al. Physical accessibility in primary health care settings: results from California on-site reviews. Disability and Health Journal. 2012;5:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri MT, Kroll T. Understanding the consequences of access barriers to health care: experiences of adults with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2003;25:85–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM. Community based participatory research with communities defined by race, ethnicity, and disability: translating theory to practice. In: Bradbury H, editor. The SAGE Handbook of Action Research. SAGE Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Kripke CC, Raymaker D. Primary care for adults on the autism spectrum. Medical Clinics of North America. 2014;98:1169–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, Ashkenazy E, et al. “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: health-care experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2015;19:824–831. doi: 10.1177/1362361315576221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, McDonald K, et al. Collaboration strategies in non-traditional community-based partnerships: lessons from an academic-community partnership with autistic self-advocates. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2011;5:143–150. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, McDonald K, et al. The development and evaluation of an online healthcare toolkit for autistic adults and their primary care providers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3763-6. Epub ahead of print 06 June. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis C, Raymaker DM, McDonald KE, et al. Comparison of healthcare experiences in autistic and non-autistic adults: a cross-sectional online survey facilitated by an academic-community partnership. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28:761–769. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura MJ, Hersh AO, Hilton JF, et al. Change in health status and access to care in young adults with special health care needs: results from the 2007 national survey of adult transition and health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHS University, editor. Rehabilitation Research Center on Health and Wellness for Persons with Long-term Disabilities. Barriers to Accessing Healthcare for People with Disabilities: A Checklist for People with Disabilities, Their Families and Disability Advocates. Portland, OR: Oregon Health & Science University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scheer J, Kroll T, Neri MT, et al. Access barriers for persons with disabilities: the consumer’s perspective. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2003;13:221–230. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp LP. Stata: data analysis and statistical software. 2013 Available at: http://www.stata.com/

- United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS) 2016 Available at: https://www.census.gov/people/disability/methodology/acs.html.

- Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U. Emergency department use among adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46:1441–1454. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2692-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JA, Tint A, Paquette-Smith M, et al. Perceived self-efficacy in parents of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016;20:425–434. doi: 10.1177/1362361315586292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) World Report on Disability. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) WHO | Disability and health. 2013 Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs352/en/index.html.

- Zerbo O, Massolo ML, Qian Y, et al. A study of physician knowledge and experience with autism in adults in a large integrated healthcare system. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2015;45:4002–4014. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]