Abstract

Although a robust literature describes the intergenerational effects of traumatic experiences in various populations, evidence specific to refugee families is scattered and contains wide variations in approaches for examining intergenerational trauma. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria, the purpose of this systematic review was to describe the methodologies and findings of peer-reviewed literature regarding intergenerational trauma in refugee families. In doing so we aimed to critically examine how existing literature characterizes refugee trauma, its long-term effects on descendants, and psychosocial processes of transmission in order to provide recommendations for future research. The results highlight populations upon which current evidence is based, conceptualizations of refugee trauma, effects of parental trauma transmission on descendants’ health and well-being, and mechanisms of transmission and underlying meanings attributed to parental trauma in refugee families. Greater methodological rigor and consistency in future evidence-based research is needed to inform supportive systems that promote the health and well-being of refugees and their descendants.

Keywords: Intergenerational trauma, Refugees, Families

Introduction

The number of refugees and displaced individuals forced to migrate worldwide due to war, mass violence, and political instability has grown to unprecedented levels. There were an estimated 1.9 million refugees in 1951 and 2.4 million in 1970 globally, with dramatic increases to 12.1 million in 2000 and 14.3 million in 2014. These estimates capture only a fraction of the additional millions of other displaced persons, asylum-seekers, and stateless persons unable to return to their homelands [1]. Among refugees, traumatic exposure prior to and during migration is strongly linked to mental health problems and psychological distress [2, 3], and evidence indicates these challenges among firstgeneration refugees can persist years after resettlement [4]. Accordingly, there is increased recognition that war-related post-traumatic stress extends beyond the individual to affect families [5] with potential long-terms effects on the health and psychosocial well-being of individuals in subsequent generations [6].

Intergenerational trauma generally refers to the ways in which trauma experienced in one generation affects the health and well-being of descendants of future generations [6, 7]. Negative effects can include a range of psychiatric symptoms as well as greater vulnerability to stress [7, 8]. A robust literature documents the intergenerational effects of traumatic experiences in various populations, including the offspring of survivors of abuse, armed conflict, and genocide [7, 8]. Yet existing evidence specific to refugee families is scattered across numerous disciplines and contains wide variations in methodologies and approaches for examining intergenerational trauma. The development of a solid evidence-base regarding what is transmitted across generations as well as how transmission occurs in specific populations is needed to inform appropriate supportive policies and programs for refugee families.

The current study presents a systematic review of empirical literature to date on intergenerational trauma within refugee families. We use the term “refugee” to broadly refer to individuals forced to flee their countries of origin in the context of political violence, persecution, and instability [9, 10]. Our primary aim is to examine patterns in research methodologies and findings, with attention to how existing literature conceptualizes refugee trauma, its longterm effects, and psychosocial processes of transmission. We also provide recommendations for future directions in research in order to inform evidence-based interventions to support current and subsequent generations of refugee families.

Methods

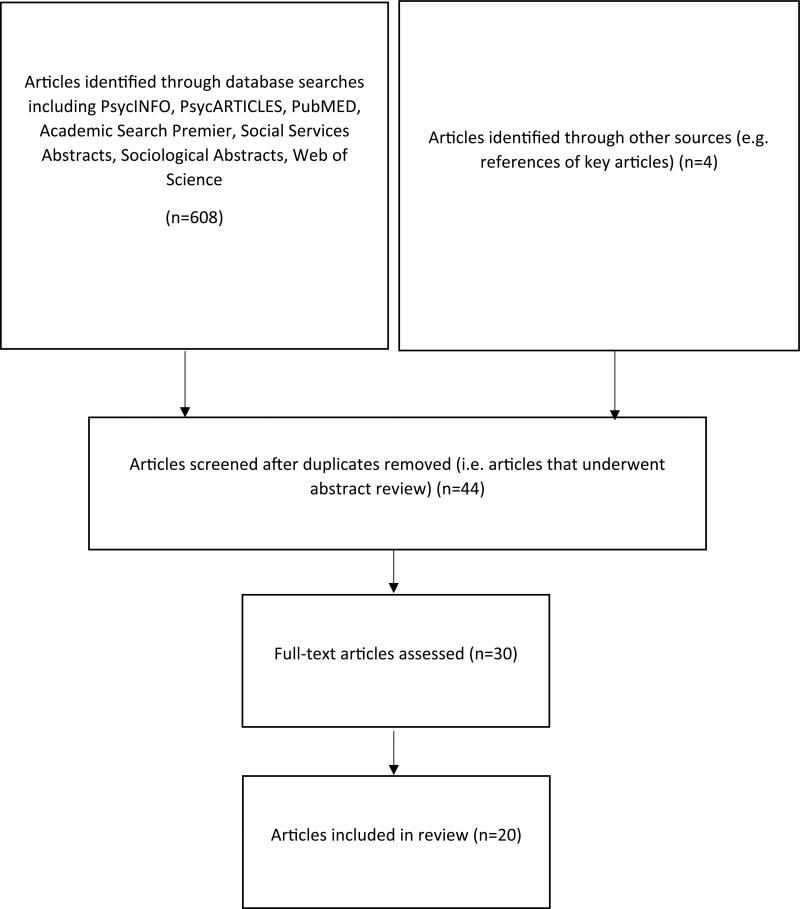

Criteria outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guided our systematic review [11]. We included studies in our review if: (a) they included refugees or individuals who were displaced from their country of origin due to war, political persecution or conflict, and mass violence; (b) the experience of trauma was collective in nature and affected a targeted group of people bound by a common cultural identity; (c) children or offspring did not experience political trauma directly themselves or fled from conflict areas with their families at a very young age; (d) articles were published in English; and (e) articles were published in peer-reviewed journals through 2015. We excluded studies that were (a) theoretical or conceptual in nature, in which no direct information was collected from individuals or groups; (b) based on non-refugee populations (e.g. military veterans); (c) focused on biological or epigenetic transmission of trauma; (d) based on clinical case studies or samples of n < 10; or (e) centered around trauma experiences that did not take place in the context of war or conflict. We did not exclude studies based on geographic location or methodology (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods designs were deemed appropriate if the aforementioned criteria were met) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection based on PRISMA method

We identified articles through PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, PubMED, Academic Search Premier (EBSCO), Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science using the Boolean search strategy to combine the following keywords: intergenerational or transgenerational trauma, refugee, and child. We found these keywords maximized the number of potential studies in our search. This led to the initial identification of 611 articles generated across the search engines. After excluding duplicates, we conducted an article title and abstract review, followed by full paper review, to determine eligibility for inclusion. We then conducted subsequent searches for relevant citations within articles subjected to a full paper review. Forty-four studies were relevant to our inclusion and exclusion criteria. Upon review of the full article, we found 30 articles appropriate for a full-text examination that met our criteria. To maintain our focus on refugees, we excluded studies on internally-displaced or post-conflict populations living in their country of origin who may not be removed from ongoing or immediate threat to safety or stability. We further excluded studies of only grandchildren of traumatized grandparents, as these studies were not clear as to the nature of family relationships and caretaking responsibilities among grandparents. We included studies with overlapping samples but ensured that such articles contained unique findings. Through this process, 20 studies met criteria for our review.

Results

Overview of Study Methodologies and Emergent Themes

Table 1 provides an overview of the included studies and their emergent themes. With regards to research design, our review included 15 studies that used quantitative methods, four studies that used qualitative methods, and one study that used mixed-methods. Among quantitative studies, 11 were comparative outcome studies testing differences between descendants of refugee trauma survivors and control groups of similar ethnic origin. The remaining four studies used correlational methods to examine the effects of parental predictors on child mental and behavioral health outcomes in community-drawn samples of trauma-affected families. Only one study incorporated a longitudinal design. Qualitative studies explored potential mechanisms by which parental trauma affects family and child well-being as well as underlying themes that inform meanings that underlie the intergenerational transmission of trauma within families. The analytic approaches among the four qualitative studies included two studies that used a Grounded Theory approach to analysis, one study that used narrative analysis, and one study that used content analysis.

Table 1.

Overview of studies and emergent themes

| Authors | Research design | Sample | Population | Study location | Concept of refugee parent trauma | Effects on child mental health and well-being | Mechanisms and meanings of parental transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braga et al. [12] | Qualitative | Community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | Brazil | Event: (1) forced displacement; (2) restriction in a ghetto; (3) permanence as a refugee or in hiding places; (4) confinement in forced labor camps or extermination camps | Not examined in study | (1) Communication style; (2) experience of trauma; (3) forms of resilience |

| Daud et al. [29] | Quantitative | Clinical and community sample | Families from Iraq and Lebanon | Sweden | Event/symptoms: harvard/uppsala trauma questionnaire (HTQ) | Children of traumatized parents showed significantly higher levels of attention deficiency, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and psychosocial stress | Not examined in study |

| Daud et al. [30] | Quantitative | Clinical and community sample | Families with parents who were torture survivors from Iraq; families with non-tortured parents from Egypt, Syria, and Morocco | Sweden | Event/symptoms: harvard/uppsala trauma questionnaire (HTQ) | Compared to children of traumatized parents with PTSD symptoms, non-symptomatic children of traumatized parents exhibited better family and peer relations, prosocial behavior, and less emotionality and general impairment | Not examined in study |

| Fridman et al. [14] | Quantitative | Population-based community sample | Holocaust survivors and offspring of holocaust survivors | Israel | Symptoms: mental health inventory (adapted version)a | Offspring of holocaust survivors showed no differences in symptoms with comparison group | Not examined in study |

| Giladi and Bell [22] | Quantitative | Community sample | American/Canadian offspring of holocaust survivors and grandchildren of holocaust survivors | North America | Symptoms: secondary trauma scaleb | Offspring and grandchildren of holocaust survivors reported significantly higher secondary trauma stress than controls | Family communication |

| Han [8] | Quantitative | Community sample | Southeast Asian young adults | United States | Event: perceived parental trauma (adapted from HTQ) | Perceived parental trauma was associated with offspring's sense of coherence | Parent–child attachment |

| Kellermann [15] | Quantitative | Community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | Israel | Event: experience linked to the holocaust | Offspring of holocaust survivors reports more responsibility and protective of survivor parent feelings | Offsprings’ perception of trauma transmitted from parent |

| Letzter-Pouw et al. [16] | Quantitative | Population-based community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors and grandchildren of holocaust survivors | Israel | Experiment 1—symptoms: clinical administered PTSD scaleb Experiment 2—symptoms: holocaust salienceb |

Perceived transmission of burden from mother and father were positively related with posttraumatic symptoms | Offsprings’ perceived parental transmission of “burden of the holocaust” |

| Lev-Wiesel [13] | Qualitative | Community sample | Three successive generations (holocaust, transit camp following migration from Morrocco, and forced relocation from Ikrit) | Israel | Symptoms: PTSD self-report questionnairea | Not examined in study | Uncovered meaning of trauma (e.g. collective or individual), psychological impact of parents’ experiences (e.g. PTSD, feelings of inferiority), losses (e.g. self-esteem), and sense of mission for the next generation |

| Lin, Suyemoto and Kiang [28] | Qualitative | Community sample | Cambodian American offspring of Khmer rouge genocide survivors | United States | Event: experience linked to the Khmer rouge genocide | Not examined in study | Silence |

| Sagi-Schwartz et al. [17] | Quantitative | Population-based community sample | Holocaust survivors, offspring of holocaust survivors, and grandchildren of holocaust survivors | Israel | Symptoms: impact of event scalec | Trauma did not appear to transmit across generations | Not examined in study |

| Shrira et al. [18] | Quantitative | Population-based community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | Israel | Event: parental experience linked to the holocaust | Offspring, especially those with two survivor parents, reported a higher sense of well-being, but more physical health problems than comparisons | Not examined in study |

| Shrira [19] | Quantitative | Community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | Israel | Event: parental experience linked to the holocaust | Offspring reported higher Iranian nuclear threat salience than comparisons. Offspring also reported slightly more anxiety symptoms than comparisons | Not examined in study |

| Spencer and Le [22] | Quantitative | Community sample | Chinese and Southeast Asian youth | United States | Event: parental refugee experience | Parents’ refugee status was a positive predictor of peer delinquency. Peer delinquency was a positive predictor of serious violence and family/partner violence. Parental engagement a negative predictor of serious violence but for Vietnamese youth only | Parental engagement and peer delinquency |

| Vaage et al. [26] | Quantitative | Community sample | Vietnamese refugees and their children | Norway | Symptoms: symptom check list-90-revisedc | Father's PTSD at arrival in Norway predicted children's mental health | Not examined in study |

| Weinberg and Cummins [25] | Quantitative | Community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | Australia | Event: parental experience linked to the holocaust | Compared to non-offspring Jews, offspring of holocaust survivors with two survivor parents had lower general positive mood | Not examined in study |

| Wiseman et al. [20] | Mixed | Community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | Israel | Event: parental experience linked to the holocaust | Not examined in study | Parental overprotection; silence |

| Wiseman [21] | Qualitative | Community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | Israel | Event: parental experience linked to the holocaust | Not examined in study | Holocaust survivors’ inability to express care and be present |

| Yehuda et al. [23] | Quantitative | Clinical and community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | United States (New York) | Symptoms: parental PTSD scaleb | Offspring of holocaust survivors had more emotional abuse and neglect than comparison group whose parents did not have PTSD | Child maltreatment |

| Yehuda et al. [24] | Quantitative | Community sample | Offspring of holocaust survivors | United States (New York) | Symptoms: parental PTSD scaleb | Higher prevalence of lifetime PTSD, mood and anxiety disorder was observed in offspring than controls | Not examined in study |

PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder

Measure completed by parents only

Measure completed by child only

Measure completed by parent and child

Sixteen studies drew from participant samples of adult offspring of trauma-affected refugee parents. Three studies based their analyses on data of parents and their children who were minors (under age 18). One study's sample consisted of adolescent children of refugee parents alone. Adult offspring participants ranged in ages from 18 to 70 years, children who participated in studies with their parents ranged from ages 4–23 years, and the study with children who were minors only had average ages of 14–15 years.

Themes that emerged in our analysis highlight populations upon which current evidence is based, conceptualizations of refugee trauma, effects of parental trauma transmission on descendants’ mental health and well-being outcomes, and the mechanisms of transmission and underlying meanings attributed to the intergenerational transmission of trauma in refugee families.

Refugee Populations and Study Locations

Fourteen of the 20 studies were conducted with the offspring of Holocaust survivors. Holocaust survivors endured various traumatic experiences under Nazi occupation in Europe during World War II. Sources of trauma included experiences in labor or extermination camps, constriction to residential ghettos, hiding from Nazis, family separation, and starvation, among other cruelties [12, 13]. Geographic locations of these studies included one study conducted in Brazil [12], nine in Israel [13–21], three in the United States and Canada [22–24], and one in Australia [25]. Offspring of Holocaust survivors were identified and recruited to studies from national samples or through local communities (educational institutions, online social networks, treatment programs, organizations), Thirteen studies drew from community samples of Holocaust survivor offspring [18–22, 24, 25] and one study consisted of a community and clinical sample [23].

Four studies examined refugees who survived the Southeast Asian wars and the Khmer Rouge genocide, The wars in Southeast Asia involved numerous countries and resulted in the forced displacement of Vietnamese, Cambodians, Lao/Mien, Hmong, and ethnic Chinese in the region, Examples of traumatic experiences among Southeast Asian refugees included genocide, explosion of landmines, serious injury in war, imprisonment in concentration camps, and flight by boat [8, 26–28]. Of these studies, three were conducted in the United States [8, 27, 28] and one in Norway [26]. Each study drew from community samples of Southeast Asian groups, One study recruited a sample of Vietnamese, Cambodians, and Hmong college students whose refugee parents fled their home countries after the Communist seizure of power over the region in 1975 [8]. Another study consisted of Chinese, Cambodian, Lao/Mien, and Vietnamese youth [27]. Two studies focused on a single Southeast Asian population, including children of refugees who fled Vietnam by boat [26] and the offspring of Cambodians who survived the genocide under the Khmer Rouge [28].

Two studies drew from the traumatic events encountered by refugees in Sweden from the Middle East, specifically those fleeing social and political instability and armed conflict in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Morocco [29, 30]. Traumatic experiences associated with displacement of peoples from this region included imprisonment, torture, rape, kidnapping, near-death experiences, and forced separations, Both studies recruited refugee parents from a treatment center for survivors of torture and their families and a comparison sample of refugees of similar backgrounds with no history of torture drawn from the community.

Conceptualization of Trauma Among Refugee Parents

Studies in our review presented refugee parent trauma as events and/or psychological symptoms, Twelve studies were based on samples of refugee parents’ offspring who experienced traumatic events alone, Among these, inclusion criteria for participation entailed having at least one parent or both parents that fled war or political persecution (see Table 1); thus, participant inclusion served as a proxy for assessing parental trauma. Research on Holocaust survivor offspring included participants whose parents fled Nazi-occupied territory [15, 16, 22], with seven studies specifying the nature of traumatic events among parents such as having experienced labor or concentration camps, starvation, or being forced to hide or flee [12, 18–21, 23, 24]. In addition, two of these studies examined the perceptions of parental trauma from the perspective of the children of Southeast Asian refugees [8, 28].

Four studies directly assessed refugee parents’ traumatic symptoms, in addition to events, using scales [17, 26, 29, 30]. Research on Middle Eastern families in Sweden showed significantly higher levels of trauma symptoms among affected parents compared to non-traumatized control parents using the Harvard/Uppsala Trauma Questionnaire [29, 30]. Similarly, using the Impact of Event Scale assessing posttraumatic stress, a study of Israeli Holocaust survivors found greater levels of traumatic stress among survivor mothers than the comparison group [17]. Among Vietnamese refugee families in Norway, Vaage et al. found 30% of children had one parent with elevated psychological distress using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist [26]. One study of Holocaust survivors and their offspring that measured trauma as psychological symptoms alone found adverse scores on scales measuring dissociate symptoms and satisfaction with life among refugee parents [14].

Effects of Trauma Transmission on Child Mental Health and Well-Being Outcomes

Thirteen studies describe effects of intergenerational trauma in refugee families, yet there was notable heterogeneity in the observed outcomes among offspring associated with refugee parental trauma. Ten studies incorporated a comparison group of offspring who did not have trauma-survivor parents. Compared to controls, children of traumatized Middle Eastern refugee parents in Sweden exhibited higher levels of depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, attention deficiency, and psychosocial stress [29]. Among studies of Holocaust survivors, compared to controls, offspring had higher lifetime prevalence rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), mood, and anxiety disorders [24], higher levels of clinical posttraumatic symptoms [16] and secondary traumatic stress [22], lower general positive mood [25], greater perceptions of taking on parental pain, burden, or responsibility for survivor parents’ feelings [15], and were more likely to have experienced emotional abuse and neglect [23]. One study found offspring of Holocaust survivors in Israel had greater anxiety related to Iranian nuclear threat compared to non-Holocaust survivor offspring controls [19].

In correlational investigations, three studies found refugee parents’ trauma was associated with negative psychological outcomes among their children. A longitudinal study found that Vietnamese fathers’ PTSD symptoms assessed within the first years of arrival in Norway predicted children's mental health 23 years later [26]. Among various groups of Southeast Asian youth in the U.S., intergenerational trauma was relevant for Vietnamese youth, in which parents’ refugee status was associated with youth's engagement in acts of serious violence, mediated by peer delinquency and lack of parental engagement [27]. Similarly, Southeast Asian college students’ perceptions of their refugee parents’ trauma experiences was associated with offspring's sense of coherence, a well-being construct [8].

In contrast, two studies did not provide evidence of intergenerational trauma. Fridman et al.'s study of Israeli adult offspring of Holocaust survivors found no differences with comparison participants along measures of physical, psychological, and cognitive functioning [14]. Similarly, Sagi-Schwartz et al.'s study found no signs of traumatic stress in a community sample of Israeli offspring of Holocaust survivors [17].

Additionally, three studies contained mixed results. Shrira et al. found that Holocaust survivor offspring reported higher levels of well-being but more physical health problems than non-survivor offspring [18], whereas Weinberg and Cummins found that Holocaust survivor offspring showed lower levels of general positive mood compared to non-Holocaust survivor offspring but only among those with two survivor parents [25]. Among children of Middle Eastern refugees, Daud et al. found that two-thirds of children with traumatized parents exhibited PTSD symptoms, yet children of traumatized parents without PTSD symptoms demonstrated forms of resilience, as in levels of close relations to family and peers, comparable to children with non-traumatized parents [30].

Trauma Transmission Across Generations: Psychosocial Mechanisms and Underlying Meanings

Six quantitative studies described parenting and family relationships as mechanisms by which trauma is transmitted intergenerationally. Among Southeast Asian college students, parent–child attachment mediated the link between perceived parental trauma and diminished sense of coherence [8], whereas parental engagement and peer delinquency mediated the link between refugee parents’ experiences and engagement in serious violence among Vietnamese American youth [27]. In research on offspring of Holocaust survivors, a history of child maltreatment [23], family communication problems [22], and perceived transmission of trauma burden were linked to poorer psychological outcomes and elevated psychiatric symptoms [15, 16].

Qualitative studies focused on various aspects of transgenerational transmission of refugee parents’ experiences, highlighting forms of risk and resiliency factors. Braga et al. focused on communication between Holocaust survivors and their children, highlighting the nature of communication style (e.g. humor, fragmented discussions, secrets and silence), experiences of trauma (e.g. parents’ inability to provide sense of stability and security), and forms of resilience (e.g. visits to concentrations camps, sense of belonging) [12]. Lin et al. explored communication within Cambodian refugee families and found that silence from family survivors impacted children's sense of belonging to a community and transmitted a continued pattern of avoidance and silence [28]. Parental silence about war-related traumas and a sense of overprotection was observed among adult offspring of Holocaust survivors [20]. Similarly, loneliness in childhood and adolescence among offspring of Holocaust survivors was linked to maladaptive patterns in communication and other interpersonal processes with survivor parents [21]. In a study of three generations of war-affected families, the meaning of trauma (e.g. collective or individual), psychological impact of parents’ experiences (e.g. PTSD, feelings of inferiority), losses (e.g. self-esteem), and the mission for the next generation were salient themes that emerged for subsequent generations [13].

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to present a systematic review of empirical research on intergenerational trauma in refugee families. We noted distinctions across research designs in order to contextualize the nature and scope of research findings. Overall, a large proportion of studies used quantitative methods to test differences in psychological and well-being outcomes among children with traumatized and non-traumatized parents, or to examine the relationship between parental trauma and child outcomes. In addition, qualitative studies explored children's perceptions of and underlying meanings derived from parental experiences of trauma. This body of literature is useful for establishing an empirical base for investigating intergenerational effects of trauma and mechanisms of transmission across generations within families in different refugee populations. Still, several quantitative studies base conclusions on relatively small sample sizes and did not use analytic techniques to control for potential confounding variables. Moreover, many of the studies in our review relied to adult children to provide insight into the long-term effects of parental trauma on the subsequent generation. Future studies can be enhanced by drawing from larger samples that allow for use more advanced statistical techniques to account for alternative factors, such as post-migration and acculturative stressors, that may explain negative outcomes among children of refugees [31, 32]. In addition, inclusion of youth participants of refugee parents would serve to identify developmentally appropriate interventions that can mitigate negative outcomes in childhood and adolescence from carrying on into adulthood. Along these lines, future studies should also incorporate longitudinal designs that can attend to processes tied to intergenerational trauma that occur over time.

Much of the existing literature on refugee families has centered on Holocaust survivor families, a refugee population more distantly removed from war-related traumas and issues of immediate resettlement. This research has provided opportunities to study diverse effects and mechanisms by which trauma among first-generation survivors is processed and transmitted over time, and has examined subsequent generations of offspring at various stages of adulthood. However, there are notable differences between Holocaust survivor families and more contemporary refugee populations, the vast majority of whom come from non-Western cultural backgrounds [33]. Furthermore, an earlier meta-analytic review that did not find evidence for the intergenerational transmission of trauma among nonclinical samples of Holocaust survivors and their families notes a number of protective factors in this population, including prewar family stability and postwar institutional supports such as the founding of the State of Israel and the public recognition of the Holocaust [34]. Given the tremendous growth of refugees in recent years, future research should examine the effects and processes of intergenerational trauma transmission in diverse and more current refugee populations.

Additionally, existing research is limited by the inconsistent ways in which trauma is conceptualized and assessed among the refugee parents’ generation. Numerous studies did not directly measure specific traumatic experiences or symptoms, instead relying on inclusion of offspring with parents who survived war or other forms of mass trauma. Incorporating both parent- and child-reported data as well as assessment of specific traumatic events and/or psychiatric symptoms among parents in future research would allow for greater precision in understanding how parental trauma is processed within families and passed on intergenerationally. Similarly, few studies used scales to evaluate the specific nature of traumatic experiences or the frequency of posttraumatic stress symptoms among first-generation refugees. Consistent use of psychometrically sound measures that distinguish war-related traumatic events and their psychosocial effects is sorely needed since not all refugees develop mental illness in light of adverse experiences [35]. We recognize that assessment of psychiatric symptoms reflects a medicalized conceptualization of trauma that may not account for culturally-specific expressions of distress [36, 37] or the broader social, political, and historical context in refugees’ countries of origin (e.g. colonialism, natural disaster, social oppression) [9, 38]. However, the use of theoretically-based scales to assess traumatic experiences and stress symptoms may be used across diverse populations and can help build a stronger evidence-base and inform best practices for appropriate interventions.

In light of diverse populations and forms of trauma across these studies, effects of refugee parents’ trauma on children and offspring were diverse yet mostly negative. More than half of the study findings in our review suggest an increased risk of adverse psychological outcomes and vulnerability to psychosocial stress within the next generation of refugee families. Adverse outcomes included PTSD, mood, and anxiety disorder symptoms, psychological pain or burden in relation to parental trauma, and greater risk of abuse and neglect. These findings underscore how intergenerational effects can go beyond the manifestation of PTSD or traumatic stress symptoms specifically to include other psychological or well-being outcomes. Still, a few studies did not find evidence of negative psychosocial or mental health effects in the following generation. Future research should consider the inclusion of positive outcomes, such as forms of resilience and post-traumatic growth, in order to bolster protective factors and account for strengths within refugee families across generations [25, 39].

Finally, over half of the studies in this review explored mechanisms by which trauma is transmitted from parents to their children as well as meanings attributed to refugee parents’ trauma. Despite the heterogeneity in populations, forms of trauma, and their effects, the literature was fairly consistent in describing parenting and family interactions as playing significant roles in the ways in which parental trauma is processed within families. Quantitative studies identified family and parent–child relationships as potential mediators in the link between the experiences of traumatized refugee parents and the emotional and behavioral health of their children. Qualitative studies were largely exploratory in nature and drew attention to the ways in which parental trauma was transformed and infused with meaning for the next generation. Theory-driven empirical investigations that test other potential mechanisms of transmission, such as biological, individual, and societal pathways, should continue to be explored in future research [40].

Conclusion

Greater methodological rigor and consistency is needed in evidence-based research on the intergenerational transmission of trauma in families. This can be done in a number of ways:

Include children and youth participants to identify potential developmental and psychological consequences of parental trauma and mental health as well as protective factors early on in order to inform appropriate interventions that can prevent negative outcomes in the future.

Account for pre-migration stressors (i.e. war-related traumatic experiences) as well as post-migration stressors in refugee families.

Incorporate longitudinal designs to examine the effects of refugee parents’ trauma over time and attend to potential effects on future generations’ at critical junctures during the lifespan.

Draw from diverse refugee populations to reflect the convergence of social, cultural, and political factors that shape pre- and post-migration influences on the health and well-being of refugee families.

Integrate data reported from the refugee parent generation and subsequent generations.

Use theoretically-sound measurements that distinguish between traumatic experiences or events and traumatic stress symptoms.

Explore protective factors and resiliency outcomes in subsequent generations, in addition to forms of psychological and emotional distress and disturbance.

Our review suggests a limited knowledgebase exists regarding intergenerational trauma in refugee families, and considerable research is needed in order to address current gaps and obtain greater insight into the nature and processes of trauma transmission. As war and mass violence continue throughout the world, individuals and families are forced to flee to other countries for sanctuary in large numbers. It is our hope that these recommendations help to advance research as well as inform responsive policies and programs that improve the long-term health and well-being of refugees and their families.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest All listed authors have reviewed and approved this manuscript, report no conflicts of interest, and will accept responsibility for its content.

References

- 1.United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR): population statistics. UNCHR; 2015. Available from http://www.unhcr.org. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fazel M, Reed RV, Panter-Brick C, Stein A. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: risk and protective factors. Lancet. 2012;379(9812):266–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, Rashid M, Ryder AG, Guzder J, Hassan G, Rousseau C, Pottie K. Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(12):E959–E967. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliott MN, Berthold SM, Chun CA. Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. JAMA. 2005;294(5):571–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weine S, Muzurovic N, Kulauzovic Y, Besic S, Lezic A, Mujagic A, Muzurovic J, Spahovic D, Feetham S, Ware N, Knafl K, Pavkovic I. Family consequences of refugee trauma. Fam Process. 2004;43(2):147–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04302002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dekel R, Goldblatt H. Is there intergenerational transmission of trauma? The case of combat veterans’ children. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(3):281. doi: 10.1037/a0013955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bezo B, Maggi S. Living in “survival mode:” Intergenerational transmission of trauma from the Holodomor genocide of 1932–1933 in Ukraine. Soc Sci Med. 2015;134:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han M. Relationship among perceived parental trauma, parental attachment, and sense of coherence in Southeast Asian American college students. J Fam Soc Work. 2005;9(2):25–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.George M. A theoretical understanding of refugee trauma. Clin Soc Work J. 2010;38(4):379–87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hein J. Refugees, immigrants, and the state. Annu Rev Sociol. 1993:43–59. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braga LL, Mello MF, Fiks JP. Transgenerational transmission of trauma and resilience: a qualitative study with Brazilian offspring of Holocaust survivors. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):134–44. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lev-Wiesel R. Intergenerational transmission of trauma across three generations: a preliminary study. Qual Soc Work. 2007;6(1):75–94. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fridman A, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Sagi-Schwartz A, Van IJzendoorn MH. Coping in old age with extreme childhood trauma: aging Holocaust survivors and their offspring facing new challenges. Aging & Ment. Health (London) 2011;15(2):232–42. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.505232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellermann NPF. Perceived parental rearing behavior in children of Holocaust survivors. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2015;38(1):58–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Letzter-Pouw S, Shrira A, Ben-Ezra M, Palgi Y. Trauma transmission through perceived parental burden among Holocaust survivors’ offspring and grandchildren. Psychol Trauma. 2013;6(4):420–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sagi-Schwartz A, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Grossmann KE, Joels T, Grossmann K, Scharf M, Koren-Karie N, Alkalay S. Attachment and traumatic stress in female Holocaust child survivors and their daughters. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1086–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shrira A, Palgi Y, Ben-Ezra M, Shmotkin D. Transgenerational effects of trauma in midlife: evidence for resilience and vulnerability in offspring of Holocaust survivors. Psychol Trauma. 2012;3(4):394–402. doi: 10.1037/a0020608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shrira A. Transmitting the sum of all fears: Iranian nuclear threat salience among offspring of Holocaust survivors. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7(4):364–71. doi: 10.1037/tra0000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiseman H, Metzl E, Barber JP. Anger, guilt, and intergenerational communication of trauma in the interpersonal narratives of second generation Holocaust survivors. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(2):176–84. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiseman H. On failed intersubjectivity: recollections of loneliness experiences in offspring of Holocaust survivors. Am J Orthopsychiatr. 2008;78(3):350–8. doi: 10.1037/a0014197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giladi L, Bell TS. Protective factors for intergenerational transmission of trauma among second and third generation Holocaust survivors. Psychol Trauma. 2012;5(4):384–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yehuda R, Halligan SL, Grossman R. Childhood trauma and risk for PTSD: relationship to intergenerational effects of trauma, parental PTSD, and cortisol excretion. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13(3):733–53. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yehuda R, Bell A, Bierer LM, Schmeidler J. Maternal, not paternal, PTSD is related to increased risk for PTSD in offspring of Holocaust survivors. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(13):1104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinberg MK, Cummins RA. Intergenerational effects of the Holocaust: subjective well-being in the offspring of survivors. J Intergener Relatsh. 2013;11(2):148–61. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaage AB, Thomsen PH, Rousseau C, Wentzel-Larsen T, Ta TV, Hauff E. Paternal predictors of the mental health of children of Vietnamese refugees. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. 2011;5(2):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer JH, Le TN. Parent refugee status, immigration stressors, and Southeast Asian youth violence. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(4):359–68. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin NJ, Suyemoto KL, Kiang PNC. Education as catalyst for intergenerational refugee family communication about war and trauma. Commun Disord Q. 2009;30(4):195–207. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daud A, Skoglund E, Rydelius PA. Children in families of torture victims: transgenerational transmission of parents’ traumatic experiences to their children. Int J Soc Welf. 2005;14(1):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daud A, Klinetberg B, Rydelius PA. Resilience and vulnerability among refugee children of traumatized and non-traumatized parents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Mental Health. 2008;2(7) doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis BH, MacDonald HZ, Lincoln AK, Cabral HJ. Mental health of Somali adolescent refugees: the role of trauma, stress, and perceived discrimination. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(2):184–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fazel M, Wheeler J, Danesh J. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1309–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Sagi-Schwartz A. Are children of Holocaust survivors less well-adapted? A meta-analytic investigation of secondary traumatization. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(5):459–69. doi: 10.1023/A:1025706427300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollifield M, Eckert V, Warner TD, Jenkins J, Krakow B, Ruiz J, Westermeyer J. Development of an inventory for measuring warrelated events in refugees. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46(1):67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisenbruch M. From post-traumatic stress disorder to cultural bereavement: diagnosis of Southeast Asian refugees. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(6):673–80. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedersen D. Political violence, ethnic conflict, and contemporary wars: broad implications for health and social well-being. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(2):175–90. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hollifield M, Warner TD, Lian N, Krakow B, Jenkins JH, Kesler J, Stevenson J, Westermeyer J. Measuring trauma and health status in refugees: a critical review. JAMA. 2002;288(5):611–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taku K, Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. The factor structure of the posttraumatic growth inventory: a comparison of five models using confirmatory factory analysis. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(2):158–64. doi: 10.1002/jts.20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weingarten K. Witnessing the effects of political violence in families: mechanisms of intergenerational transmission and clinical interventions. J Marital Fam Ther. 2004;30(1):45–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]