Abstract

There is increasing interest in making patient participation an integral component of medical research. However, practical guidance on optimizing this engagement in healthcare is scarce. Since 2002, patient involvement has been one of the key features of the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) international consensus effort. Based on a review of cumulative data from qualitative studies and internal surveys among OMERACT participants, we explored the potential benefits and challenges of involving patient research partners in conferences and working group activities. We supplemented our review with personal experiences and reflections regarding patient participation in the OMERACT process. We found that between 2002 and 2016, 67 patients have attended OMERACT conferences, of whom 28 had sustained involvement; many other patients contributed to OMERACT working groups. Their participation provided face validity to the OMERACT process and expanded the research agenda. Essential facilitators have been the financial commitment to guarantee sustainable involvement of patients at these conferences, procedures for recruitment, selection and support, and dedicated time allocated in the program for patient issues. Current challenges include the representativeness of the patient panel, risk of pseudo-professionalization, and disparity in patients’ and researchers’ perception of involvement. In conclusion, OMERACT has embedded long-term patient involvement in the consensus-building process on the measurement of core health outcomes. This integrative process continues to evolve iteratively. We believe that the practical points raised here can improve participatory research implementation.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) has shown that long-term involvement of patients in research is beneficial for identifying and validating outcomes that matter to patients. |

| Building and sustaining successful partnerships with patients requires restructuring of the research process and investing time and budgets into training and support of patient research partners (PRPs). |

| The integration of qualitative and quantitative data, complemented by participation of PRPs, enhances the face validity of outcome research. |

| Ensuring representativeness of the patient perspective for diagnosis, disease severity and cultural, social-economic, and geographical diversity is still challenging. |

Introduction

There is a growing trend in healthcare research to focus more on outcomes that matter to patients, and more widely on patient-centered research [1, 2]. To this end, the involvement of patients not just as subjects of research but as partners in the design, assessment, and implementation of health research is recommended, and is sometimes mandatory for grant approval [3–5]. In the USA, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) was established in 2010 to promote research that focuses on those aspects of health that are most meaningful and important to patients. PCORI involves patients at critical stages of the research process to ensure that the questions being asked are relevant and the results are meaningful to people living with a given health condition [6]. In Canada, a unique study explored perspectives of people with osteoarthritis with full involvement of patients in all research phases [7]. In the context of the Innovative Medicine Initiative, the European Union, in collaboration with the pharmaceutical industry, has initiated the European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI) to promote the education and active involvement of patients in health research [8]. Internationally, the Cochrane Collaboration involves patients in the development of systematic reviews [9, 10]. The UK has the longest tradition of public and patient involvement through a National Institute of Health Research program called Involve [11]. Within the specialty of rheumatology, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [12], Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT), an international consensus effort, and its member working parties [13], the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) [14], and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) [15] have gained experience and published regarding active involvement of patients in their main activities. In the past years, EULAR and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) have included patient representatives in their guideline development and other initiatives. In several European countries, arthritis patient organizations have established networks of trained research partners [16, 17].

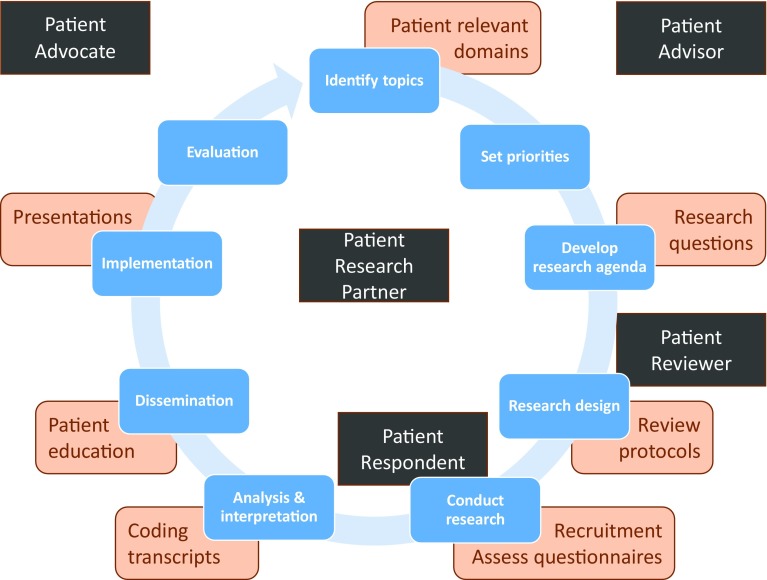

Although patient engagement in research is promoted, it is often limited to evaluating research proposals for funding or participating in advocacy groups. However, patients can contribute to research in different roles, not only as respondents or study participants but also as advocates, advisors, reviewers, or research partners (Fig. 1). When referring to higher levels of engagement, involving close collaboration in the research process itself, we use the term ‘patient research partner’ (PRP). A PRP is someone living with the relevant disease or condition who participates as an active team member on an equal basis with professional researchers, adding the benefit of his/her experiential knowledge to research projects [13]. There is limited guidance on how high-level patient involvement in research can be achieved, and few case studies to illustrate its success [18–20].

Fig. 1.

The empirical research circle: potential patient contributions and potential patient roles in research. Phases of the empirical research circle are in blue, examples of potential patient contributions are in orange, and five potential patient roles in research are in black. The role of patient research partner and patient advisor are applicable throughout the research circle. The role of patient reviewer is particularly relevant in the phase of assessing grant applications, often used by research funding bodies. The roles of patient respondent or patient participant mostly relate to the phase of data collection. The role of patient advocate is generally beneficial in the phases of fundraising, establishing supportive legislation for medical research, and dissemination

OMERACT, an independent international organization of health professionals, epidemiologists, outcomes researchers, pharmaceutical representatives, and patients [21], has engaged PRPs consistently and increasingly over a period of 14 years [22]. The involvement of patients has been rewarding for both the researchers and the patient representatives. By collaborating with PRPs, relevant outcomes for patients such as fatigue, well-being, and sleep-disturbances have been identified, and PRPs have reported increased knowledge, self-confidence, and empowerment [23, 24]. OMERACT has incrementally learned how to support, promote, and gain from this process. Here we review how PRP involvement in OMERACT was developed, supported, and promoted, how challenges were addressed, and the benefits that have accrued.

Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) and the Involvement of Patients

The first OMERACT conference (1992) was convened at a time of actively questioning traditional but arbitrary approaches to assessing the benefits of treatment in rheumatic diseases. The conference aimed to consolidate methodologically oriented approaches that had begun separately in the USA through activities within the ACR and in Europe through the World Health Organization and International League of Associations of Rheumatology (WHO/ILAR). One of the objectives of the first OMERACT conference was to develop consensus on the minimum number of outcome measures to be included in all rheumatoid arthritis (RA) randomized controlled trials. The conference brought together 92 rheumatologists, methodologists, regulatory officials, and pharmaceutical industry researchers from around the world. Agreement was achieved on the outcome domains that are known as the RA core set [25].

Subsequent meetings of OMERACT followed every 2 years, developing and validating specific outcome measures and developing core sets for other rheumatic diseases as proposed by Working Groups within OMERACT. The basis of OMERACT is evidence-based discussions with consensus through nominal group techniques.

In 2000, during discussions about “minimum clinically important” differences in outcome measures [26], there was uncertainty whether the perspective of physicians and researchers was similar to that of patients. Concluding that a representative consensus should include all three, the final plenary voting session at the conference recognized that the patients’ perspective was needed [27], and a decision was made to invite patients to the next meeting.

The 11 PRPs who attended OMERACT 6 (2002) had a limited degree of participation in the meeting. They were asked to review the RA core set from the patient perspective and to identify domains that mattered to patients. It became clear that the views of researchers and patients were not identical [28]. Symptoms of importance to patients such as fatigue, overall well-being, and sleep disturbances were not included in the existing RA core set. Also, the design of clinical trials at that time would not provide patients with the information they felt was needed to judge the success of new treatments. After this meeting, the leadership of OMERACT and a sufficiently large proportion of those actively involved in OMERACT-related research were convinced that PRPs should continue to be involved. Since then, between 17 and 21 patients have participated in each of the OMERACT conferences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients attending Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) conferences

| Characteristics | 2002: Gold Coast, QLD, Australia | 2004: Asilomar, CA, USA | 2006: St. Julian’s Bay, Malta | 2008: Kanaskis, AB, Canada | 2010: Borneo, Malaysia | 2012: Pinehurst, NC, USA | 2014: Budapest, Hungary | 2016: Whistler, BC, Canada |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 9 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 18 |

| Male | 2 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Previous attendance | ||||||||

| Yes | 0 | 6 | 15 | 8 | 14 | 10 | 16 | 14 |

| No | 11 | 12 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 8 |

| Condition | ||||||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 11 | 17 | 15 | 7 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| Osteoarthritis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Psoriatic arthritis | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Fibromyalgia | 3 | 1 | ||||||

| Gout | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Vasculitis | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 2 | |||||||

| Myositis | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Connective tissue diseases | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Behçet’s syndrome | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Chronic pain | 1 | |||||||

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 1 | |||||||

| Country | ||||||||

| USA | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| UK | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Australia | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Norway | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Sweden | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Denmark | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Canada | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Germany | 1 | |||||||

| New Zealand | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| France | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Malaysia | 3 | |||||||

| Turkey | 1 | |||||||

| Italy | 1 | |||||||

| Proportion of all attending the conference (%) | 7.9 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 9.0 | 18.1 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 10.0 |

Each meeting included patients with the rheumatologic condition featured in the program because experiential knowledge of the condition itself was felt to be critical. Thirty of the 67 PRPs (45 %) have participated in at least two OMERACT conferences, ten of whom have participated in at least four OMERACT conferences. In recent years many more PRPs have been members of OMERACT Working Groups, which carry forward the research agenda between the biannual meetings.

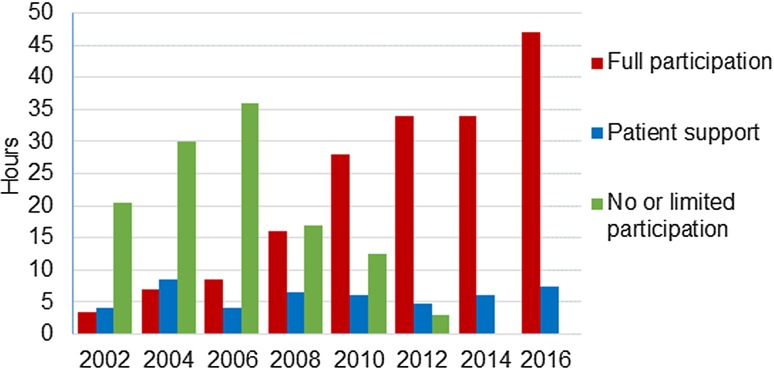

The extent to which PRPs are integrated into the OMERACT meeting program has steadily expanded (Fig. 2). As a consequence, the timetable commitment for PRPs during the meeting has increased from 7.5 h in 2002 to 47 h in 2016. In parallel, OMERACT has developed systems for the selection and support of PRPs, with the funding and organization of their attendance being a practical challenge. However, developing and implementing rules and guidelines recognizing that PRPs are an essential element of all OMERACT activities has been the greatest intellectual challenge [13].

Fig. 2.

Outcome measures in rheumatology (OMERACT) conference timetabled hours designated for full participation of patient research partners in the program and for patient research partners support sessions

Recognizing Patient Research Partners (PRPs) as an Essential Element of all OMERACT Activities

Endorsement by the Leadership and Full Participation in the OMERACT Process

The continuous support of the OMERACT leadership has been crucial, as has the continued increase of experience and patient involvement (Fig. 2) [29]. Initiatives taken by patients, such as producing the OMERACT Glossary (which is now part of every conference information pack) have gradually convinced the majority of OMERACT participants that PRPs make a positive contribution. Results from a recent survey of repeat OMERACT attendees concluded that working with PRPs was one of the aspects that made them return to these meetings [30].

OMERACT values the perspectives of all stakeholders and stimulates open discussions through an interactive meeting design. All participants should be treated as equals and have the same opportunities to contribute to the process. An introductory patient session familiarizes PRPs with the conditions under discussion at the meeting, OMERACT terminology, and procedures. Session moderators provide patients with a pre-session subject overview and provide an environment that encourages all stakeholders, but particularly patients, to speak up and contribute actively in all aspects of the meeting. When voting on consensus decisions, PRPs have full voting rights. The roles played by PRPs at and between OMERACT meetings have steadily expanded to include leading, mentoring, reporting small group discussions, chairing plenary sessions, writing reports, helping to design and facilitate research between meetings, securing funding, and writing and editing papers.

Support of PRPs and the Sustainability of Participation

OMERACT support for PRPs evolved as experience working together accumulated. Increasing integration of patients into the program (Fig. 2) combined with the achievement of specific milestones was accompanied by greater attention to the support of PRPs (Table 2). Orientation and training sessions have been cumulative and written into the conference program design. The increasing time demand on PRPs has resulted in the introduction of personalized programs to ensure that each PRP is able to attend the sessions most relevant to their condition. Arriving 1 day before the conference and scheduling ‘down time’ during the meeting are included to prevent overburdening and respect disease management (e.g., time for activities of daily living, resting, and doing exercises). An important innovation in 2008 was the introduction of a ‘buddy system,’ where new patient participants are paired with more experienced PRPs. New participants found this extremely helpful [23].

Table 2.

Milestones and cumulative patient research partner support activities: 2000–2016

| Year | Milestone | PRP support activities |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Vote at the final plenary to include the patient perspective at the next OMERACT | Establishment of Patient Stream Coordinator with allocated funding for patient support |

| 2002 | First patients participating in the conference | Participation in two main sessions only with special patient group workshop Pre-session briefing and post-session debriefing Experienced clinical researcher available for questions, discussion, and general support Nominated clinician available for individual assistance |

| 2004 | Establishment of Patient Panel with a chair | Production (by PRPs) of OMERACT Glossary |

| Post-meeting educational day in Bristol for European patients | ||

| Patient newsletter started (by PRPs) | ||

| 2006 | First policy statement: patient involvement becomes mandatory for module and workshop applications | Patients provided with their own meeting room |

| Brief patient introduction session before start of meeting | ||

| Patient Panel wrap-up meeting included in program | ||

| 2008 | PRPs responsible for supporting each other | Substantial patient introduction session before start of meeting Buddy system introduced Pre-conference PRP dinner |

| OMERACT Glossary in conference information pack for all attendees | ||

| Fatigue included as a recommended outcome in the RA core set | ||

| 2010 | Second policy statement: integral involvement of patients in all working groups | Daily patient update sessions introduced |

| 2012 | Evaluation of a decade of patient involvement in OMERACT presented | Pre-conference patient information pack, including lay summaries of all the sessions Introduction of personalized programs PRPs fully involved in development of OMERACT Filter 2.0 |

| 2014 | Consensus on recommendations for the involvement of patient research partners in OMERACT working groups approved | Daily patient evaluation sessions introduced |

| PRP becomes a member of OMERACT Executive | ||

| 2016 | Preparatory internet seminars for patients |

OMERACT Outcome Measures in Rheumatology, PRP patient research partner

Facilitating PRP participation in ongoing research between meetings has been a challenge. Working Group leaders have been confronted with practical issues such as providing lay summaries of documents, preventing overburdening, ensuring sufficient lead time for PRPs to read information and provide feedback, and adequate acknowledgment of PRPs’ contributions. In addition, it is not always clear whether (all) PRPs fulfil the criteria for authorship of peer-reviewed publications. The criteria can vary between groups, to some degree influenced by the PRP’s decision to be coauthor or not. These processes are continually evolving.

Acceptance of the Role of PRPs by OMERACT Members

In 2014, recommendations for the involvement of PRPs in OMERACT Working Groups were approved by an overwhelming majority at the OMERACT plenary voting session [13]. Together with the appointment of a patient delegate to the Executive Committee, this demonstrates the OMERACT commitment to the principles and practice of substantive patient engagement in the research process to ensure the inclusion of that perspective as a mandatory feature of high-quality outcomes research [13]. This point was arrived at in a stepwise process, with many OMERACT participants gradually changing their views on PRPs’ contributions, and realizing the value they can add to the research process. These developments [29] can be summarized in the observation that increasing experience of working with PRPs has the greatest influence on researchers’ perceptions.

Organizing the Attendance of PRPs

Recruitment, Selection, and Representativeness of PRPs

Potential OMERACT PRPs are first approached by a member of a Working Group, usually a physician. Minimum requirements include being diagnosed with the condition being studied and the ability to speak English, articulate the lived experience with the disease, and travel abroad and participate in an intense 4-day OMERACT working conference. The patient stream leader, who is one of the members of the Executive Committee, approves nominations and invites PRPs to attend the conference. OMERACT aims at an adequate representation of continents, sexes, conditions, and experiences appropriate to each conference program. Ensuring appropriate representativeness of PRPs has been an ongoing challenge. Detailed characteristics have not been systematically collected, but the majority of OMERACT PRPs have been white, middle-class, middle-aged, and higher educated. Attempts have been made to broaden the diversity of the OMERACT PRPs, such as finding participants from Malaysia when the meeting was held there, but it is difficult to involve patients from countries where participatory research is less recognized and physician–patient relationships are traditionally more paternalistic [31]. Nevertheless, the countries of residence of the PRPs (Table 1) are similar to those of the rest of the participants in OMERACT, as is the proportion residing in the USA, Europe, and elsewhere (23, 48, and 29 %, respectively, for PRPs compared with 30, 45, and 25 % for other participants).

Patients and their treating physician are often both involved in OMERACT research, requiring a separation of roles of patient/doctor in the clinic from that of collaborative partners at OMERACT [32]. To facilitate this, each OMERACT meeting has a designated consultant physician available for patients if they have health concerns.

OMERACT expects PRPs to represent their personal perspective of living with the disease, not that of a particular group of patients. Guidelines have been developed to help PRPs and researchers focus on the personal lived experience rather than personal agendas or organizational advocacy [13].

Resources for Participation

Patient participation in research, and in particular at conferences, requires financial resources. The cost of each PRP attending OMERACT have been met by OMERACT funds or donations organized by Working Groups. These expenses have been considerable, and accommodating patients with severe disabilities may require special transportation arrangements (e.g., supplemental oxygen on flights, personal assistance, or special travel arrangements). The average cost per patient has been similar for almost all meetings; the total cost for patient attendance for each of the last three meetings has been approximately US$100,000 per meeting (in 2014 values [US$] after correction for US inflation). This is a considerable portion of the central funds available to OMERACT and represents a major fundraising commitment by the OMERACT Executive Committee.

Challenges and Benefits

Demonstrating the Impact of PRPs

There is evidence that engaging patients structurally in outcomes research provides benefits for the overall research process [5, 33, 34]. Patients’ questions, opinions, and concerns provided face validity to the OMERACT process and widened the research agenda [24]. New domains, including fatigue, foot problems, stiffness definition, work productivity, and flares, were identified by patients and prompted new research. The involvement of PRPs enhanced the inclusion of patient-relevant outcomes in core sets. It changed the culture of OMERACT and may influence practice in other disciplines and research contexts. At the individual level, PRPs reported ‘positive pay-back’ in feeling more empowered towards their own disease, they appreciated opportunities to contribute to the greater community, and felt better able to keep abreast of research developments related to their disease [24].

In the 2014 OMERACT survey, Working Group leaders valued the PRPs’ feedback as a reality check of the relevance and quality of their project, and stated that the feedback influenced the choice of appropriate outcomes and instruments. Interestingly, patients were less certain about the added value of their experiential knowledge to the overall research. This confirms earlier findings that patients tend to underestimate their contribution to the research process [23].

Risk of Pseudo-Professionalization

Almost half of OMERACT PRPs have attended two or more OMERACT conferences and some are highly involved in other ongoing research projects. As these patient participants have become more experienced, some researchers have welcomed their increased familiarity with research processes and vocabulary. However, others have questioned the authenticity of their patient perspective because they felt training and support over a long period of time could result in ‘professional patients’ who are not able to represent the ‘naïve’ or ‘authentic’ patient perspective [29] and therefore do not represent ‘ordinary’ patients. Whether this is true is open to debate [29], but OMERACT minimizes this risk by ensuring a mixture of new and more experienced PRPs at meetings, and by focusing education on the ability of PRPs to articulate their personal experience in the context of outcome research.

Extent of Patient Participation Between Meetings

A 2014 internal OMERACT survey showed that 14 of 18 Working Group leaders reported patient involvement between conferences, usually including at least two PRPs. Involvement included regular electronic communications, teleconferences, and face-to-face meetings where possible. The survey revealed differences between researchers and PRPs in their perception of the role played by PRPs. Most PRPs perceived themselves as “advisors” or “information providers”; four viewed themselves as collaborators and one PRP reported a leadership role. In contrast, Working Group leaders perceived that PRPs had higher levels of involvement: ten Working Group leaders viewed PRPs as “collaborators” in their projects and two Working Group leaders mentioned the role as being “in control”. This disparity might be explained by the varying maturity of Working Groups in regards to their activities and the tendency of PRPs to underestimate the influence of their participation [23].

PRPs in Different Types of Projects

There remains some debate as to whether the appropriate extent of patient participation may depend on the particular research project. Although OMERACT recommends involvement of patients as PRPs throughout the research process, in reality this is not always feasible. Some patients provide valuable input into one or more research phases, not as a PRP but as a patient advisor. For example, in a study to develop or evaluate a new imaging modality, it may be argued that patients’ perspectives are not as necessary for the assessment of the measurement algorithms or scoring method. However, it would be appropriate for patients to comment on the burden, safety, and feasibility of a test and to understand how the results could be used in guiding their care.

Examples of PRPs in Working Groups

A detailed analysis of the consequences of PRP involvement in OMERACT has been published [24, 27]. Here we showcase two working groups that substantively engaged patients in all their activities. After patients identified fatigue as an often ignored and under-researched disease symptom, the OMERACT Fatigue Working Group initiated a research agenda with studies at different centers to systematically explore the phenomenon of fatigue. The Working Group looked at its severity and evaluated existing measurement instruments and are developing new ones. Patients have been involved on different levels and in different roles [35]. In the development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for fatigue, patients played a pivotal role in focus group meetings, individual interviews, surveys, clinical trials, cognitive interviews, as well as in the OMERACT Working Group. The result has been a new instrument, the Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue (BRAF) questionnaire [36], which is based on the conceptual framework developed from qualitative studies, ensuring its face validity. New data on the impact and measurement of fatigue have resulted in the recommendation to measure fatigue in clinical trials [37] and in clinical care to reconcile disparities between physician and patient assessments of disease activity [38].

The OMERACT RA Flare Working Group involved patients from its initiation through every stage of the project. Since the inception of the project in 2006, the role of PRPs has been intense and diverse [35]. Tasks were related to developing the design of the study, co-organizing focus group meetings, and coding and analyzing transcripts. PRPs participated in international, bi-weekly teleconferences to discuss the development of an instrument to measure flares, and a patient committee held additional face-to-face meetings and teleconferences with other group leaders for feedback and discussion of research progress and interim findings [39]. This work is ongoing.

Discussion

The way patients are involved as research partners in OMERACT has grown from an initial tightly circumscribed and experimental arrangement in 2002 to complete involvement at all levels of activity, supported by an inclusive and supportive code of practice approved by the membership in 2014. During this time, OMERACT has successfully introduced a number of conceptual, structural, and practical processes to ensure the integration of the patient perspective and substantive engagement throughout outcome measure development. These have centered on recognizing PRPs as an essential element of all OMERACT activities and funding and organizing the attendance of PRPs. Initial leadership commitment to providing resources for participation and a structure for the recruitment, selection, and support of PRPs was crucial. The experience of working with PRPs led to a stepwise acceptance and then encouragement of the role by OMERACT members and has resulted in increased PRP engagement in Working Group activities between OMERACT meetings. This approach can be applied by other societies and research groups [40], and may result in the development of different structural and procedural changes to ensure that PRPs are supported and productive in that setting.

PRP inclusion in the OMERACT process is not intended to represent the perspective of all patients as they only represent themselves and their experiences. However, having two patients within a Working Group, whatever their background and experience, is infinitely better than not involving patients at all. Ensuring a more representative view may be achieved through the use of mixed research methods that include qualitative interviews, focus groups, Delphi methods, or surveys to expand the input across a wider spectrum of patients [19]. Such methods are increasingly recognized as an essential requisite of outcomes research in identifying and defining the concept of measurement (e.g., what you are seeking to measure) grounded in the patient experience, and to ensure that the ultimate measure is reflective of this concept [2].

While many have advocated increased participation in research, developing metrics to demonstrate the added value of such inclusion is challenging. In this report we provide not only experiential evidence from the perspectives of patients and researchers, but real evidence of change in the direction of research endeavors, and more detailed analyses are available [17, 23, 24, 27, 29, 30]. The recognition of fatigue as an important aspect of living with RA has now been incorporated into recommendations for patient assessments in clinical care, and for clinical trials, though the optimal measure has yet to be defined. There are few publications that have described methods of successful engagement in detail [41], and further studies are needed to provide additional evidence of the benefits and impact of patient participation.

While the work reported here has been limited to rheumatology, the conceptual foundations and the framework developed for patient inclusion are widely applicable across all chronic diseases and beyond outcomes research [42, 43]. EULAR now recommends involvement of PRPs throughout the research process, preferably from the beginning [12]. PCORI has also recently developed a rubric for patient and stakeholder engagement that provides examples of how patients can be involved at different phases of research [44, 45]. The US Food & Drug Administration Critical Path Initiative, the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative [46], and the International Society for Quality of Life research (ISOQOL) [47] have also begun to integrate PRPs in their work. The process explained here should be useful in other contexts and to other specialties. Moving such an agenda forward is time consuming and necessitates enthusiasm and perseverance, particularly to support and train patients and health professionals. However, OMERACT researchers value patient participation highly in conferences and this is one of the central reasons for their ongoing participation [30]. The dialogue and engagement between researchers and PRPs has greatly improved the quality of core outcome sets, by ensuring that outcomes are relevant to patients [48, 49]. Patient participation has enriched the research agendas and enhanced mutual understanding of outcomes of importance for both patients and researchers [24].

The experience of OMERACT should help move policy makers, funders, and researchers closer to the view that participatory research is not only a normative imperative for outcome research, but is also effective in producing relevant research and health outcomes [41].

Author contributions

MdeW, JRK, PT, and LG drew together the main elements of the article. All authors were then involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to the content of this paper. PGC is supported in part by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Financial disclosures

The authors received no specific funding for this paper and have no financial disclosures directly linked with the contents of this paper. OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatology) is an international research group that is supported by registration fees and has received unrestricted hands-off funding from more than 23 pharmaceutical and clinical research companies over the past 2 years. MdeW, JRK, PT, DB, MB, PB, PGC, MADA, LM, LSS, JAS, VS, COB, and LG are, or were previously, members of the OMERACT Executive Committee; they received no financial remuneration for their participation in this role. COB was supported, in part, through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Pilot Project Program Award (1IP2-PI000737-01) and a PCORI Methods Award (SC14-1402-10818). All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Contributor Information

Maarten de Wit, Phone: +31 20 4448219, Phone: +31 418 515904, Email: mp.dewit@vumc.nl, Email: martinusdewit@hotmail.com.

John R. Kirwan, Email: john.kirwan@bristol.ac.uk

Peter Tugwell, Email: Tugwell.BB@uOttawa.ca.

Dorcas Beaton, Email: beatond@smh.ca.

Maarten Boers, Email: m.boers@vumc.nl.

Peter Brooks, Email: brooksp@unimelb.edu.au.

Sarah Collins, Email: sarah.collins_counsellor@btopenworld.com.

Philip G. Conaghan, Email: P.Conaghan@leeds.ac.uk

Maria-Antonietta D’Agostino, Email: maria-antonietta.dagostino@aphp.fr.

Cathie Hofstetter, Email: mcfence@on.aibn.com.

Rod Hughes, Email: Rod.Hughes@asph.nhs.uk.

Amye Leong, Email: amye@healthymotivation.com.

Ann Lyddiatt, Email: alyddiatt@primus.ca.

Lyn March, Email: lyn.march@sydney.edu.au.

James May, Email: jmay@seanet.com.

Pamela Montie, Email: plmontie@gmail.com.

Pamela Richards, Email: pamrichards@mac.com.

Lee S. Simon, Email: lssconsult@aol.com

Jasvinder A. Singh, Email: jasvinder.md@gmail.com

Vibeke Strand, Email: vibekestrand@me.com.

Marieke Voshaar, Email: Marieke@voshaar.nl.

Clifton O. Bingham, III, Email: cbingha2@jhmi.edu.

Laure Gossec, Email: laure.gossec@aphp.fr.

References

- 1.Staniszewska S, Haywood KL, Brett J, Tutton L. Patient and public involvement in patient-reported outcome measures: evolution not revolution. Patient. 2012;5:79–87. doi: 10.2165/11597150-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speight J, Barendse SM. FDA guidance on patient reported outcomes. BMJ. 2010;340:c2921. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright MT, Roche B, von Unger H, Block M, Gardner B. A call for an international collaboration on participatory research for health. Health Promot Int. 2010;25:115–122. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slager M, Tritter JQ. Exchanging knowledge on participation by EU health consumers and patients in research, quality and policy [conference report] Health Expect. 2013;16:128–129. doi: 10.1111/hex.12114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, et al. A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. Patient. 2014;7:387–395. doi: 10.1007/s40271-014-0065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank L, Basch E, Selby JV. The PCORI perspective on patient-centered outcomes research. JAMA. 2014;312:1513–1514. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller JL, Teare SR, Marlett N, Shklarov S, Marshall DA. Support for living a meaningful life with osteoarthritis: a patient-to-patient research study. Patient. 2016;9(5):457–464. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EUPATI. European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovations. 2013. http://www.patientsacademy.eu/. Accessed 25 Aug 2013.

- 9.Kelson MC. Consumer collaboration, patient-defined outcomes and the preparation of cochrane reviews. Health Expect. 1999;2:129–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.1999.00042.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shea B, Santesso N, Qualman A, Heiberg T, Leong A, Judd M, et al. Consumer-driven health care: building partnerships in research. Health Expect. 2005;8:352–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2005.00347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.INVOLVE. Website Supporting public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. 2016. http://www.invo.org.uk/. Accessed 10 Feb 2016.

- 12.de Wit MP, Berlo SE, Aanerud GJ, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Croucher L, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the inclusion of patient representatives in scientific projects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:722–726. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.135129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung PP, de Wit M, Bingham CO 3rd, Kirwan JR, Leong A, March LM, et al. Recommendations for the involvement of patient research partners (PRP) in OMERACT Working Groups. A report from the OMERACT 2014 Working Group on PRP. J Rheumatol 2016;43:187–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.de Wit MPT, Campbell W, Orbai AM, Tillett W, FitzGerald O, Gladman D, et al. Building bridges between researchers and patient research partners: a report from the GRAPPA 2014 annual meeting. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:1021–1026. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Mielants H, Feldtkeller E, Braun J. ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis: the patient version. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1381–1386. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kjeken I, Ziegler C, Skrolsvik J, Bagge J, Smedslund G, Tøvik A, et al. Research priorities, attitudes and experiences among individuals with rheumatic diseases in Scandinavia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:793. [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Wit MP, Elberse JE, Broerse JE, Abma TA. Do not forget the professional - the value of the FIRST model for guiding the structural involvement of patients in rheumatology research. Health Expect. 2015;18:489–503. doi: 10.1111/hex.12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CAPA. Canadian Arthritis Patient Alliances: patient involvement in research. 2015. http://www.arthritispatient.ca/research. Accessed 29 June 2015.

- 19.De Wit M, Kvien T, Gossec L. Patient participation as an integral part of patient reported outcomes development guarantees the representativeness of the patient voice—a case-study from the field of rheumatology. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000129. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, Sabharwal R, Rein A, Konopka K, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:13–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.OMERACT. 2016. http://www.omeract.org/. Accessed 10 Feb 2016.

- 22.Kirwan J, de Wit MPT. What have we learned from a decade of patient involvement in OMERACT and its effect on trial outcome assessments? Trials. 2011;12(suppl 1):A80. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-S1-A80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Wit MPT, Koelewijn-van Loon MS, Collins S, Abma TA, Kirwan JR. “If I wasn’t this robust”: patients’ expectations and experiences at the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Conference 2010. Patient. 2013;6:179–87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.de Wit M, Abma T, Koelewijn-van Loon M, Collins S, Kirwan J. Involving patient research partners has a significant impact on outcomes research: a responsive evaluation of the international OMERACT conferences. BMJ Open. 2013;3. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Boers M, Tugwell P, Felson DT, van Riel PL, Kirwan JR, Edmonds JP, et al. World Health Organization and International League of Associations for Rheumatology core endpoints for symptom modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1994;41:86–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells G, Anderson J, Beaton D, Bellamy N, Boers M, Bombardier C, et al. Minimal clinically important difference module: summary, recommendations, and research agenda. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:452–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Wit MP, Abma TA, Koelewijn-van Loon MS, Collins S, Kirwan J. What has been the effect on trial outcome assessments of a decade of patient participation in OMERACT? J Rheumatol. 2014;41:177–184. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hewlett SA. Patients and clinicians have different perspectives on outcomes in arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:877–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Wit M, Abma T, Koelewijn-Van Loon M, Collins S, Kirwan J. Facilitating and inhibiting factors for long-term involvement of patients at outcome conferences–lessons learnt from a decade of collaboration in OMERACT: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003311. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flurey CA, Kirwan JR, Hadridge P, Richards P, Grosskleg S, Tugwell PS. The spirit of OMERACT: Q methodology analysis of conference characteristics valued by delegates. J Rheumatol. 2015. doi:10.3899/jrheum.150113. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Gossec L, Kirwan J, de Wit MPT. Patient perspective in outcome measures developed by OMERACT. Indian J Rheumatol. 2013;8:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.injr.2013.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hewlett S, De Wit M, Richards P, Quest E, Hughes R, Heiberg T, et al. Patients and professionals as research partners: challenges, practicalities, and benefits. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:676–680. doi: 10.1002/art.22091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mockford C, Staniszewska S, Griffiths F, Herron-Marx S. The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24:28–38. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindenmeyer A, Hearnshaw H, Sturt J, Ormerod R, Aitchison G. Assessment of the benefits of user involvement in health research from the Warwick Diabetes Care Research User Group: a qualitative case study. Health Expect. 2007;10:268–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2007.00451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bingham CO, 3rd, Alten R, de Wit MP. The importance of patient participation in measuring rheumatoid arthritis flares. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1107–1109. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hewlett S, Dures E, Almeida C. Measures of fatigue: Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multi-Dimensional Questionnaire (BRAF MDQ), Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Numerical Rating Scales (BRAF NRS) for Severity, Effect, and Coping, Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ), Checklist Individual Strength (CIS20R and CIS8R), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Functional Assessment Chronic Illness Therapy (Fatigue) (FACIT-F), Multi-Dimensional Assessment of Fatigue (MAF), Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), Pediatric Quality Of Life (PedsQL) Multi-Dimensional Fatigue Scale, Profile of Fatigue (ProF), Short Form 36 Vitality Subscale (SF-36 VT), and Visual Analog Scales (VAS) Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(Suppl 11):S263–S286. doi: 10.1002/acr.20579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, Bathon J, Boers M, Bombardier C, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1371–1377. doi: 10.1002/art.24123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan NA, Spencer HJ, Abda E, Aggarwal A, Alten R, Ancuta C, et al. Determinants of discordance in patients’ and physicians’ rating of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:206–214. doi: 10.1002/acr.20685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bykerk VP, Lie E, Bartlett SJ, Alten R, Boonen A, Christensen R, et al. Establishing a core domain set to measure rheumatoid arthritis flares: report of the OMERACT 11 RA flare Workshop. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:799–809. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jinks C, Carter PE, Rhodes C, Beech R, Dziedzic K, Hughes R, et al. Sustaining patient and public involvement in research: a case study of a research centre. J Care Serv Manag. 2013;7:146–154. doi: 10.1179/1750168715Y.0000000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Mockford C, Barber R. The GRIPP checklist: strengthening the quality of patient and public involvement reporting in research. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2011;27:391–399. doi: 10.1017/S0266462311000481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nierse CJ, Schipper K, van Zadelhoff E, van de Griendt J, Abma TA. Collaboration and co-ownership in research: dynamics and dialogues between patient research partners and professional researchers in a research team. Health Expect. 2012;15:242–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00661.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abma TA, Nierse C, Widdershoven G. Patients as partners in responsive research: methodological notions for collaborations in mixed research teams. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:401–415. doi: 10.1177/1049732309331869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.PCORI. PCORI engagement rubric. 2015. http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Engagement-Rubric-with-Table.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr 2015.

- 45.Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, Schrandt S, Sheridan S, Gerson J, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033–1041. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0893-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williamson P, Clarke M. The COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative: its role in improving Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:ED000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Haywood K, Brett J, Salek S, Marlett N, Penman C, Shklarov S, et al. Patient and public engagement in health-related quality of life and patient-reported outcomes research: what is important and why should we care? Findings from the first ISOQOL patient engagement symposium. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(5):1069–1076. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0796-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirwan JR, Bartlett SJ, Beaton DE, Boers M, Bosworth A, Brooks PM, et al. Updating the OMERACT filter: implications for patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1011–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Kirwan JR, Fries JF, Hewlett SE, Osborne RH, Newman S, Ciciriello S, et al. Patient perspective workshop: moving towards OMERACT guidelines for choosing or developing instruments to measure patient-reported outcomes. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1711–1715. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]