Abstract

The reuse of reclaimed water from wastewater depuration is a widespread and necessary practice in many areas around the world and must be accompanied by adequate and continuous quality control. Ascaris lumbricoides is one of the soil-transmitted helminths (STH) with risk for humans due to its high infectivity and an important determinant of transmission is the inadequacy of water supplies and sanitation. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a limit equal to or lower than one parasitic helminth egg per liter, to reuse reclaimed water for unrestricted irrigation. We present two new protocols of DNA extraction from large volumes of reclaimed water. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) were able to detect low amounts of A. lumbricoides eggs. By using the first extraction protocol, which processes 500 mL of reclaimed water, qPCR can detect DNA concentrations as low as one A. lumbricoides egg equivalent, while dPCR can detect DNA concentrations as low as five A. lumbricoides egg equivalents. By using the second protocol, which processes 10 L of reclaimed water, qPCR was able to detect DNA concentrations equivalent to 20 A. lumbricoides eggs. This fact indicated the importance of developing new methodologies to detect helminth eggs with higher sensitivity and precision avoiding possible human infection risks.

1. Introduction

The reuse of wastewater after the depuration process is a widespread and necessary practice in many areas around the world, especially in areas prone to water scarcity. Reclaimed water can be used in agriculture and become a risk for human health due to the presence of an array of pathogens and pollutants in the reclaimed water used for irrigation [1–3]. In particular, helminth ova are capable of surviving months in water, or even years in soil, and are a potential concern wherever wastewater or biosolids are reused [4].

In 1989, the World Health Organization (WHO) [5] drew attention of health implications due to helminth infections associated with inadequate water quality and sanitation [2, 3]. Anemia, malnutrition, cognitive impairment, and gastrointestinal or pulmonary complaints are some of the problems associated with intestinal helminth infections [2, 6, 7]. Ascaris lumbricoides is one of the nematode species that cause soil-transmitted helminthic diseases (STH) and, globally, it affects over 819 million people. Of the 4.98 million years lived with disability (YLDs) attributable to STH, roughly 1.10 million YLDs were attributable to A. lumbricoides [8]. In addition, deaths from STH are attributable to heavy A. lumbricoides infection in children under 10 years of age [9].

Due to their environmental hardiness, the presence of parasitic helminth eggs as an indicator of sanitary risk is one of the water quality parameters recommended by the WHO [10]. An upper limit of one helminth egg per liter is recommended for reclaimed water to be judged suitable for unrestricted use [11, 12]. Following these recommendations, the modified Bailenger method was proposed as a reference method to detect a maximum limit of one intestinal helminth egg per 10 liters of water for diverse reuse in urban, agricultural, industrial, or environmental contexts [13, 14]. This method is considered to be time consuming (minimum 72 hours), not very sensitive, and involves subjective morphological identification and quantification of nematode eggs by optical microscopy after flotation [15].

Molecular techniques such as quantitative PCR (qPCR) or the recently developed digital PCR (dPCR) are faster and more precise techniques for identification of species and could facilitate clinical diagnosis and improve the reliability and objectivity of analytical methods. However, one of the key points for the success of molecular methods is to find the most appropriate method of DNA extraction to obtain a high quality DNA yield, with a minimum amount of PCR inhibitors [16].

Some authors have used qPCR to detect human intestinal parasites in water samples [17] and in feces [18–24], but not from reclaimed water. Nevertheless, non-human helminths parasites have been detected in fresh water [25], soil, and wastewater samples by qPCR [26].

Digital PCR (dPCR) has been used primarily in clinical diagnostics [27–29] and is a promising step forward, as this technology provides absolute quantification of DNA without the need for a standard curve [30, 31]. Absolute quantification via dPCR is achieved by partitioning the sample into a large number of individual reactions, then assessing the proportion of positive reactions [32]. Also, dPCR improves sensitivity when quantifying low concentrations of target genes in highly concentrated background DNA samples [27]. There have been no published methods for detecting A. lumbricoides ova in reclaimed water by qPCR or dPCR.

The success of PCR detection methods hinges on the techniques used to extract DNA. Optimal sensitivity is attained when extraction techniques are able to recover a large amount of target DNA from the sample media without also extracting PCR inhibitors [16].

The aim of this study is to demonstrate if two molecular techniques (qPCR and dPCR) can be used to detect A. lumbricoides eggs in reclaimed water. For this purpose, two new protocols of DNA extraction were developed to obtain sufficient quality to detect A. lumbricoides eggs by qPCR and dPCR.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

The experimental design consisted of three steps: (1) sterile bidistilled water (50 μL) was seeded with different amounts of A. lumbricoides eggs, and DNA extraction protocol and detection and quantification by qPCR and dPCR were optimized; (2) reclaimed water (500 mL and 10 L) was seeded with different amounts of A. lumbricoides eggs, for assaying DNA extraction of A. lumbricoides eggs and detection and quantification by qPCR and dPCR; and (3) reclaimed water (10 L) was seeded with different amounts of A. lumbricoides eggs and they were externally analyzed to detect helminth eggs in water by the modified method of Bailenger (WHO) by three ENAC (Spanish National Accreditation Body) accredited laboratories (see the following).

Chart of Extraction and Detection

Control

Volume: 50 μL of bidistilled water.

Number of eggs: 1 (×5 replicates); 2 (×5 replicates); 5 (×5 replicates); 10 (×5 replicates); 20 (×5 replicates); and 50 (×5 replicates).

Extraction: 1 × 50 μL each replicate.

qPCR dilutions: 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20 dilutions of each replicate.

Template: qPCR (3 × 5 μL aliquots of each dilution); dPCR (4 μL each replicate).

Final volume: qPCR (25 μL); dPCR (16 μL).

Protocol 1

Volume: 500 mL of reclaimed water.

Number of eggs: 1 (×5 replicates); 5 (×5 replicates); and 10 (×5 replicates).

Extraction: 1 × 50 μL each replicate.

qPCR dilutions: 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20 dilutions of each replicate.

Template: qPCR (3 × 5 μL aliquots of each dilution); dPCR (4 μL each replicate).

Final volume: qPCR (25 μL); dPCR (16 μL).

Protocol 2

Volume: 10 L of reclaimed water.

Number of eggs: 1 (×5 replicates); 2 (×5 replicates); 5 (×5 replicates); 10 (×5 replicates); 20 (×5 replicates); and 50 (×5 replicates).

Extraction: 6 × 50 μL sample of each replicate.

qPCR dilutions: 1 : 5, 1 : 10, 1 : 20 dilutions of each replicate.

Template: qPCR (3 × 5 μL aliquots of each dilution); dPCR (4 μL each replicate).

Final volume: qPCR (25 μL); dPCR (16 μL).

2.2. Source of A. lumbricoides Eggs

The A. lumbricoides eggs were extracted from infected human feces provided by Hydrolab S.L. Human feces were inactivated in 70% ethanol and preserved in saline solution where A. lumbricoides eggs were isolated under a magnifying glass and placed into 1.5 mL tubes with nuclease-free bidistilled water (bdW). Aliquots of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 eggs were stored at 4°C until use.

2.3. DNA Extraction from Bidistilled Water (bdW) Seeded with A. lumbricoides Eggs

Five replicates from 1, 5, 10, 20, or 50 A. lumbricoides eggs with 50 μL of bdW each were separated in 25 tubes. Finally, five batches with six samples each were extracted: five replicates (bdW seeded) and an extra sample without eggs by batch (bdW negative control). Each sample was washed twice with 500 μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, Dorset, UK), vortexing for 30 s and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatants were removed and pellets were resuspended in 50 μL of bdW and three borosilicate glass beads were added. Samples were subjected to three cycles of freezing with liquid nitrogen for 5 s followed by thawing in a 56°C water bath for 5 min and vortexed for 40s and speed setting of 6.0 m s−1 using the FAST-PREP® 24 instrument (Mp Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA). Samples were centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 1 min. Later, DNA concentration was measured by Quant-iTPicoGreen dsDNA assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

2.4. DNA Extraction from Reclaimed Water Seeded with A. lumbricoides Eggs

Reclaimed water was provided by Murcia Este Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP). The Murcia Este WWTP processes urban wastewater using activated sludge (type A2O) which allows a significant removal of nutrients (N and P) in the treated water. An anaerobic digestion process stabilizes the excess sludge generated. The reclaimed physicochemical water parameters were pH 7.84 ± 0.09, 3.5 ± 0.48 nephelometric turbidity units (NTU), 2.24 ± 0.12 mS cm−1 conductivity, 11.42 ± 5.96 mg L−1 total suspended solids (SS), 7.39 ± 1.96 mg L−1 biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), 36 ± 7.74 mg L−1 chemical oxygen demand (COD), 13.71 ± 3.72 mg L−1 total nitrogen (TN), and 2.48 ± 0.06 total phosphorous (TP).

2.4.1. Protocol 1 (500 mL of Reclaimed Water)

Three batches of five reclaimed water samples (500 mL) each were seeded with 1, 5, or 10 A. lumbricoides eggs (five replicates per sample). Reclaimed water not seeded was used as negative control in each batch. To retain the helminth ova, seeded reclaimed water was filtered through a 47 mm diameter Durapore® filter with a light mesh of 0.65 μm (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA). This filter was mechanically and enzymatically digested by adding 1 g of glass beads (425–600 μm diameter), 920 μL of NET 10 (10 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris HCl), 40 μL of proteinase K (30 mg mL−1), and 40 μL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, Dorset, UK). Then, samples were subjected to three cycles of freezing with liquid nitrogen for 5 s followed by thawing in a 56°C water bath for 5 min and vortexed at maximum speed in a Vortex Genie 2 machine for 2 min (MoBio Laboratories, Inc., Solana Beach, CA, USA). The samples were centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 1 min and the supernatant (containing DNA) was transferred to new tubes. DNA was extracted by conventional phenol : chloroform : isoamyl alcohol purification (25 : 24 : 1) and ethanol precipitation and further eluted in 50 μL of bdW.

2.4.2. Protocol 2 (10 L of Reclaimed Water)

Five batches of 10 L of reclaimed water were seeded with 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 A. lumbricoides eggs (five replicates per sample). Reclaimed water not seeded was used as control in each batch. This protocol was similar to protocol 1, but with some differences due to the higher amount of water to be filtered.

Ten liters of reclaimed water was filtered through two Durapore filters (5 L per each filter) of 97 mm diameter with 5 μm light mesh (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA, USA). Each filter was then introduced into a 15 mL tube with 2720 μL of CTAB buffer (2% hexadecyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide, 1.4 M NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, and 100 mM Tris pH 8.0), 2% polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP), 40 μL of proteinase K (30 mg mL−1), 240 μL of 10% SDS, and 2 g of glass beads (425–600 μm diameter) (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, Dorset, UK). After this point, each sample was divided into 3 similar aliquots (1 mL each) and the protocol continued as per the 500 mL one (protocol 1), with three cycles of freezing/thawing, centrifugation, DNA purification by phenol : chloroform : isoamyl alcohol and ethanol purification, and the pellet eluted in 50 μL of bdW. For every 10 L of reclaimed water sample, we obtained six 50 μL DNA extracts (2 filters for each 10-liter sample, each filter was divided into 3 samples); and in the case of one of them resulting in qPCR or dPCR amplification, the whole reclaimed water batch was considered to have A. lumbricoides present in the sample (positive reaction).

2.5. Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) amplifications were performed in a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems®), using a Microamp® Fast Optical 96-Well Reaction Plate with barcode (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), in a final volume of 25 μL. The final qPCR mixture contained 1x TaqMan Universal Master Mix II (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.3 μM of each primer (Roche Diagnostics, Germany), 0.1 μM of the probe, 0.2 mg mL−1 BSA, and 5 μL of DNA sample. The specific primers Alum96F and Alum183R, that amplify an 89 bp fragment of the ITS-1 (located between 18S and 5.8S rRNA genes) sequence with the FAM-labeled probe Alum124T with TMR quencher, were used to detect A. lumbricoides [18, 33]. The thermocycling conditions were 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 40 s. To detect inhibition, a TaqMan® Exogenous Internal Positive Control Reagent—containing a preoptimized internal positive control (IPC) with predesigned primers—and a TaqMan probe (Applied Biosystems) were included in all reactions, according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Each run contained one negative (bdW) and one A. lumbricoides DNA positive control. Dilutions (1 : 5, 1 : 10, and 1 : 20) of the DNA extracts were used as a template. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. In order to assess the sensitivity of the assay, the qPCR reactions were considered negative/nondetects if the Ct value exceeded 37. To calculate the copies per microliter, the dilution factor in each case was taken into account.

A standard curve of A. lumbricoides DNA was done by cloning the amplified fragment 89 bp fragment of the ITS-1 by specific primers Alum96F and Alum183R [18, 33] with TA Cloning® Kit Dual Promoter (pCR™ II vector) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the plasmid vector obtained was used to transform Escherichia coli DH5α cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), followed by purification with a QIAprep Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The DNA concentration of the plasmid standard solution was measured by fluorescence using a QuantiTPicoGreen dsDNA assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), as described by the manufacturer, and was related to the known molecular weight of a single plasmid molecule to calculate the number of copies. The standard curve was generated in triplicate by adjusting to the number of ITS-1 copies μL−1. DNA (107 ITS-1 copies μL−1) was diluted in 10-fold steps. The PCR amplification efficiency (AE) was calculated from the slopes of the regressions using the equation AE = [10(−1/slope)] − 1 [34]. The standard curve produced for the qPCR assay revealed an amplification efficiency of 92.72% and a slope of the linear equation of −3.52, with a linear correlation coefficient of 99.85%.

2.6. Digital PCR (dPCR)

Digital PCR amplification reactions were performed using QuantStudio™ 3D Digital PCR (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), with QuantStudio Digital PCR 20 K chips, in a total volume of 16 μL. The final reaction mixture contained 1x QuantStudio® 3D Digital PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 0.3 μM of each primer (Alum96F and Alum183R), 0.2 μM of the probe Alum124T [18, 33], 4 μL of DNA sample, and bdW to 16 μL. The thermal cycling conditions for the amplifications were an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 2 min at 60°C and 30 s at 98°C, and a final step of 72°C for 2 min. Template DNA extracted was used at 1 : 5 (standard curve), 1 : 10 (protocol 1; 500 mL of reclaimed water and protocol 2; 10 L of reclaimed water), or 1 : 20 dilutions (protocol 2; 10 L of reclaimed water). Dilutions were taken into account to calculate the number of copies per μL−1. The amplification results, namely, the fluorescence of each partition of chip, were analyzed with QuantStudio 3D Digital PCR System Cloud Software (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

2.7. The Modified Bailenger Method

Samples of 10 L of reclaimed water were seeded with 10 (1 sample), 50 (1 sample), and 1,000 (4 samples) A. lumbricoides eggs and analyzed following the modified method of Bailenger [15] by three different laboratories accredited by the three ENAC accredited laboratories (Spanish National Accreditation Body).

2.8. Statistics

The cycle threshold (Ct) and number of ITS-1 copies of A. lumbricoides μL−1 per number of eggs were compared using Student's t-test if the data sets were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test; P > 0.05) and homoscedastic (Levene test; P > 0.05), or with the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test, if the data sets were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test; P ≤ 0.05) or did not meet the requirement of homoscedasticity (Levene test; P ≤ 0.05) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL); Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney test with P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. qPCR

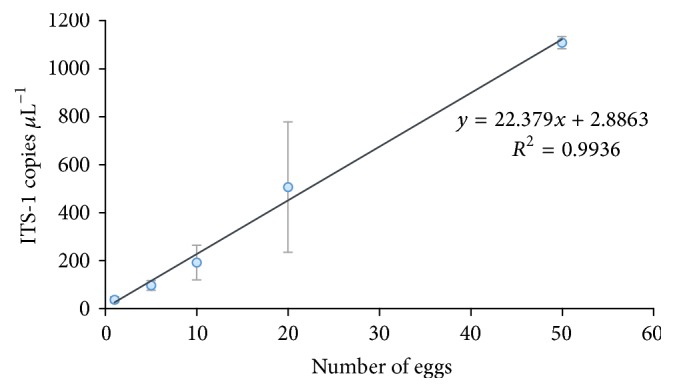

Figure 1 shows a linear regression between the ITS-1 copy numbers of A. lumbricoides per μL−1 bdW (ITS-1 copies μL−1) against different amounts of eggs in 50 μL of bdW. The number of copies μL−1 increased with the number of eggs. The negative control samples did not show amplification and the IPC and positive control amplified in all cases.

Figure 1.

Linear regression between copies ITS-1 of A. lumbricoides per microliter of bidistilled water and numbers of A. lumbricoides eggs measured by qPCR. Each value was obtained from five replicates.

The two extraction methods with water volumes of 500 mL and 10 L, protocols 1 and 2, respectively, presented promising results (Table 1). Protocol 1 was able to detect the DNA equivalent to 1, 5, and 10 A. lumbricoides eggs while protocol 2 was able to detect a minimum 20 A. lumbricoides eggs, but not less than 10 eggs or 10 eggs for 2 of the batches assayed (Table 1). Quantification of A. lumbricoides ITS-1 copies indicated that these increased with the number of eggs with both extraction protocols. The negative control samples did not show any amplification and the positive control amplified in all cases. However, the IPC amplified with a delay of two cycles in samples following protocol 2 (10 L) compared to the one from bdW or protocol 1 (500 mL), indicating that some inhibition may have been occurring in the extracts from method 2.

Table 1.

Detection of A. lumbricoides by qPCR from reclaimed water seeded with different amounts of A. lumbriocoides eggs.

| Protocol 1 (for 500 mL) | Protocol 2 (for 10 L) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eggs | Mean copies μL−1 |

Result | Number of eggs | Mean ITS-1 copies μL−1 |

Positive extractions | Result |

| 1 | 3.41 ± 0.16 | Presence | 10 | — | —/6 | Absence |

| 1 | 2.54 ± 0.32 | Presence | 10 | 46.57 ± 11.03 | 2/6 | Presence |

| 1 | 4.68 ± 3.80 | Presence | 10 | — | —/6 | Absence |

| 1 | 11.6 ± 2.02 | Presence | 10 | 45.16 ± 11.40 | 2/6 | Presence |

| 1 | 8.41 ± 1.93 | Presence | 10 | 48.68 ± 4.76 | 1/6 | Presence |

|

| ||||||

| Average ± SD | 6.14 ± 3.80 | 46.80 ± 1.78 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 5 | 42.92 ± 11.27 | Presence | 20 | 61.58 ± 9.10 | 4/6 | Presence |

| 5 | 59.31 ± 13.35 | Presence | 20 | 37.96 ± 9.02 | 2/6 | Presence |

| 5 | 54.18 ± 12.94 | Presence | 20 | 42.83 ± 3.69 | 2/6 | Presence |

| 5 | 51.51 ± 4.04 | Presence | 20 | 47.67 ± 14.40 | 1/6 | Presence |

| 5 | 64.99 ± 12.8 | Presence | 20 | 47.77 ± 4.10 | 3/6 | Presence |

|

| ||||||

| Average ± SD | 54.58 ± 8.31 | 47.56 ± 8.82 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 10 | 89.59 ± 14.4 | Presence | 50 | 123.64 ± 14.60 | 6/6 | Presence |

| 10 | 107.86 ± 4.93 | Presence | 50 | 51.76 ± 2.07 | 2/6 | Presence |

| 10 | 53.83 ± 11.04 | Presence | 50 | 39.91 ± 5.20 | 1/6 | Presence |

| 10 | 102.31 ± 11.62 | Presence | 50 | 37.64 ± 11.57 | 3/6 | Presence |

| 10 | 62.53 ± 6.84 | Presence | 50 | 56.57 ± 18.36 | 5/6 | Presence |

|

| ||||||

| Average ± SD | 83.22 ± 24.00 | 61.91 ± 35.41 | ||||

The averages are for three aliquots in 500 mL and for three aliquots of each of six different extractions per sample in 10 L. Positive extractions: number of positive extractions in each batch. Only from the “positive” aliquots were included in the calculation. Presence: Ct < 37. Absence: Ct > 37. Protocol 2, below 10-egg amplification was not observed.

Comparing both extraction methods of reclaimed water and bdW, the number of ITS-1 copies μL−1 for eggs amount showed significant differences. Statistically significant differences between ITS-1 copy number per μL from 1, 5, and 10 eggs in 50 μL of bdW and 500 mL of reclaimed water were found (P values < 0.05). Otherwise for 10, 20 eggs in bdW compared to the 10 L extraction method showed statistically significant differences in the number of copies of ITS-1 with P values < 0.05 and P < 0.001 for 50 eggs. In both cases, higher ITS-1 copy number per μL was observed in 50 μL of bdW. Furthermore, statistically significant differences were also found in 10 eggs seeding 500 mL and 10 L of reclaimed water, showing P values of <0.05 for Ct values (data not shown) but there were no statistically significant differences for ITS-1 copies μL−1 (P > 0.05).

3.2. dPCR

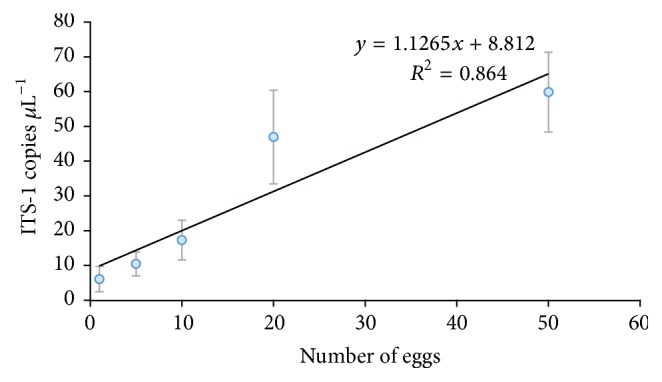

Figure 2 shows a linear regression between number of ITS-1 copies of A. lumbricoides per μL−1 bdW against 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 eggs. ITS-1 copies μL−1 increased as the number of eggs increased with an R2 of 86.4%. Negative control did not show amplification and the IPC and positive controls amplified in all cases.

Figure 2.

Linear regression between copies ITS-1 of A. lumbricoides per microliter of bidistilled water and numbers of A. lumbricoides eggs measured by dPCR. Each value was obtained from five replicates.

The number of ITS-1 copies μL−1 of A. lumbricoides following protocol 1 showed that dPCR can detect as few as 5 eggs in reclaimed water and that these increased as the number of eggs increased (Table 2). However, following protocol 2 (10 L) dPCR did not detect any eggs in seeded reclaimed water samples (Table 2). Negative control samples did not show amplification and the IPC and positive controls amplified in all cases.

Table 2.

Detection of A. lumbricoides by dPCR from reclaimed water seeded with different amounts of A. lumbriocoides eggs.

| Protocol 1 (for 500 mL) | Protocol 2 (for 10 L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eggs | Mean ITS-1 copies μL−1 |

Result | Number of eggs | Mean ITS-1 copies μL−1 |

Result |

| 1 | 4.35 | Presence | 10 | — | NA |

| 1 | — | Absence | 10 | — | NA |

| 1 | — | Absence | 10 | — | NA |

| 1 | 1.12 | Presence | 10 | — | NA |

| 1 | 7.14 | Presence | 10 | — | NA |

|

| |||||

| Average ± SD | 4.2 ± 3.01 | ||||

|

| |||||

| 5 | 13.25 | Presence | 20 | — | NA |

| 5 | 27.22 | Presence | 20 | — | NA |

| 5 | 23.77 | Presence | 20 | — | NA |

| 5 | 41.37 | Presence | 20 | — | NA |

| 5 | 7.05 | Presence | 20 | — | NA |

|

| |||||

| Average ± SD | 22.53 ± 13.27 | ||||

|

| |||||

| 10 | 16.36 | Presence | 50 | — | NA |

| 10 | 50.00 | Presence | 50 | — | NA |

| 10 | 23.30 | Presence | 50 | — | NA |

| 10 | 39.37 | Presence | 50 | — | NA |

| 10 | 28.74 | Presence | 50 | — | NA |

|

| |||||

| Average ± SD | 31.55 ± 13.31 | ||||

Presence: more than one copy μL−1. Absence: not detected; NA: no amplification.

No statistically significant differences were observed for ITS-1 copies μL−1 between eggs in bdW (1, 5, and 20) and eggs in 500 mL of reclaimed water (P values; 0.130, 0.086, and 0.060, resp.).

3.3. The Modified Bailenger Method

Table 3 shows results from the three ENAC accredited laboratories. Results indicated that the Bailenger method did not detect eggs in reclaimed water seeded with 10 and 50 eggs. When 1,000 eggs were seeded in the reclaimed water, one laboratory detected the presence of eggs but the quantified amount was very low compared with the seeded (3% of eggs).

Table 3.

Number of eggs provided by different laboratories using ENAC accredited method (modified Bailenger) from A. lumbricoides eggs seeded in 10 L of reclaimed water.

| Code number | Number of eggs seeded in 10 L of reclaimed water | Provided result by the lab |

|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | 10 | <1 egg |

| Sample 2 | 50 | <1 egg |

| Sample 3 | 1,000 | <1 egg |

| Sample 4 | 1,000 | <1 egg |

| Sample 5 | 1,000 | 28 eggs |

| Sample 6 | 1,000 | 7 eggs |

4. Discussion

The use of quantitative PCR and digital PCR could be an alternative to detect A. lumbricoides eggs in reclaimed water. Quantitative PCR could detect DNA concentrations as low as one A. lumbricoides egg equivalent in 500 mL of reclaimed water (protocol 1) and 20 A. lumbricoides eggs in 10 L of reclaimed water (protocol 2). While digital PCR detected DNA concentrations as low as five A. lumbricoides egg equivalents by first extraction protocol, no amplification could be detected by our second protocol. In bdW, both techniques were able to detect from one to 50 eggs with good correlation between ITS-1 copies μL−1 bdW to number of eggs. The detection limit of the standard curve was 10 ITS-1 copies μL−1, which is equivalent to less than one egg [35]. Similar detection limits have been reported by other authors [18].

Digital PCR was described in the 1990s and it has been focused primarily on oncology [36–38], prenatal diagnostics [39], and viruses [40–42]. Applications of dPCR for environmental samples are arising due to a high sensitivity and accurate quantification of target genes in environmental samples [43] and when there are few copies of the DNA target [36, 42, 44–46]. Some authors have reported that dPCR performed better than qPCR for DNA recovered from soils because dPCR seems to be more tolerant of PCR inhibitors [30, 38, 47].

Our study showed a good correlation with the number of eggs and dPCR in bdW (see Figure 1), but some differences were found in reclaimed water. The results showed less sensitivity of dPCR than qPCR for the DNA extractions realized by protocol 1 for 500 mL and no amplification for any of the 10 L reclaimed water samples processed via protocol 2. This could be due to increase in the reclaimed water extraction volume; then, higher inhibitory substances were extracted. Another reason might be that the volume of the template in each dPCR reaction (4/16 μL) mixture is lower than in qPCR (5/25 μL) and cannot be increased, which could have implied lower sensitivity [42].

One of the key points for the success of these DNA techniques is the use of an appropriate method of DNA extraction from samples of reclaimed water, as in this case, to obtain DNA of amplifiable quality avoiding possible inhibitions and low recovery of DNA that can reduce the efficiency of the PCR [16]. No amplification was observed following protocol 1 for 10 L of reclaimed water by both qPCR and dPCR (there is no data to show), probably due the coextraction of a high amount of inhibitory substances as organic matter that are still on reclaimed water after the depuration process, which could inhibit PCR and decrease its efficiency [16, 48–53]. Later, 500 mL of reclaimed water seeded with different amounts of A. lumbricoides eggs was extracted by the proposed protocol 1 and once optimized was adapted to DNA extraction from 10 L of reclaimed water (protocol 2). The adaptation consisted of replacing the membrane filter (higher diameter and light mesh) and the extraction buffer (CTAB + PVPP), increasing the number of filters (two filter membranes for each 10 L sample (5 L each)) and three extractions for each membrane filter. The incorporation in the DNA extraction buffer of cationic detergent CTAB [16, 54] plus polyvinylpolypyrrolidone was previously tested in DNA extractions from feces, plant, and soils to remove PCR inhibitors [18, 20, 55].

Despite the modifications, ten A. lumbricoides eggs were the minimum amount to be detected by using the optimized DNA extraction protocol (protocol 2). These results could indicate that the 10 L DNA extracts still showed some inhibition even after making the previously described changes in the DNA extraction protocols, as shown by the IPC reduction signal [16, 49, 56] because of the complex environmental matrices [30, 57] and the high volume of filtered water to detect helminth eggs following WHO recommendations [10]. Another important point could be the adherence of helminth eggs to different surfaces; the limited literature available on this indicates that the physical-chemical forces determining egg adherence are complex, and the use of plastic tubes and pipettes could be more effective than glass ones to reduce the adherence [58]. This could explain the loss of sensitivity in the detection of eggs in treated wastewater with respect to the bdW, due to the glass funnel used. Finally, the division of samples into two filters to obtain six aliquots per sample would further reduce the number of copies for detection.

WHO guidelines specify a threshold of egg number per specified volume for acceptable quality. For agricultural irrigation it recommends a value of ≤1 egg/L [11, 12], and recent epidemiological research work shows that a limit ≤ 0.1 egg/L is needed if children under 15 years are exposed [59]. Our results indicate that quantitation of ITS-1 copy number is imprecise, and sufficient accuracy has not been achieved such that the signal could be directly applied to estimating number of eggs based on ITS-1 estimates. But the most important finding stems from qualitative detection of ITS-1 from low egg number treatments, indicating sensitivity at a level approaching practical significance.

Respect to the detection of eggs by the modified Bailenger method [15], the results presented clearly show that the qPCR method developed was more efficient than the traditional method. Not many samples were sent; however, those results give us an idea of the Bailenger method sensitivity compared to the qPCR and dPCR. All samples were sent to ENAC accredited laboratories in order to be more objective in the conclusions obtained. As is well known, this traditional method implies many steps using sedimentation, desorption, centrifugation, and flotation of the material, after optical microscopy detection, where technical skills are needed to distinguish the helminth eggs [15]; therefore, it is not difficult to lose biological material in any step, leading to wrong results as was demonstrated with the samples that were sent. Finally, only one of three laboratories was able to detect nematode eggs in 10 L of wastewater in two samples (7 and 28 when 1,000 eggs were seeded).

Molecular techniques show promise for establishing the viability of helminths ova [35, 60, 61], several genetic targets can be studied at the same time [18], and it could achieve adequate sensitivity defined in formal guidelines. Therefore, these molecular techniques could be proposed a priori as alternatives to the traditional ones to assure the reuse of water with the appropriate health guarantees.

5. Conclusions

Both dPCR and qPCR can be used to detect DNA from A. lumbricoides eggs in reclaimed water. Quantitative PCR can detect DNA from one A. lumbricoides egg in 500 mL and from 10 A. lumbricoides eggs in 10 L of reclaimed water, while dPCR can detect it from one A. lumbricoides egg in 500 mL of reclaimed water. The improvement of the standardization and validation of DNA extraction protocols is a very important first step in the implementation of molecular techniques in the detection of helminth eggs and in managing the required volume of water in accordance with current legislation (10 L). The main point of this paper is that qPCR has potential application for monitoring quality of treated water. Further experiments are required to demonstrate that the method can be extensively applied in multiple settings requiring nematode eggs testing. These findings support both the continued development of this technology, and the need for further work to explore its value for routine use. A second step is to be able to detect viable eggs to enable totally safe reuse of reclaimed water.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by “Aguas de Murcia,” the company which manages the integrated cycle of water in the municipality of Murcia. The authors thank the entity of sanitation of the Region of Murcia (ESAMUR) for their interest during the development of the project.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Blumenthal U. J., Mara D. D., Peasey A., Ruiz-Palacios G., Stott R. Guidelines for the microbiological quality of treated wastewater used in agriculture: recommendations for revising WHO guidelines. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78(9):1104–1116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Silva N. R., Brooker S., Hotez P. J., Montresor A., Engels D., Savioli L. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture. Trends in Parasitology. 2003;19(12):547–551. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strunz E. C., Addiss D. G., Stocks M. E., Ogden S., Utzinger J., Freeman M. C. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001620.e1001620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordin A., Nyberg K., Vinnerås B. Inactivation of ascaris eggs in source-separated urine and feces by ammonia at ambient temperatures. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(3):662–667. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01250-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO) 778. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1989. Health guidelines for the use of wastewater in agriculture and aquaculture. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotez P. J., Brooker S., Bethony J. M., Bottazzi M. E., Loukas A., Xiao S. Hookworm infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(8):799–807. doi: 10.1056/nejmra032492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooker S., Bethony J., Hotez P. J. Europe PMC funders group human hookworm infection in the 21st century. Advances in Parasitology. 2008;(4):1–59. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(04)58004-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pullan R. L., Smith J. L., Jasrasaria R., Brooker S. J. Global numbers of infection and disease burden of soil transmitted helminth infections in 2010. Parasites and Vectors. 2014;7(1, article 37) doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Silva N. R., Chan M. S., Bundy D. A. P. Morbidity and mortality due to ascariasis: re-estimation and sensitivity analysis of global numbers at risk. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1997;2(6):519–528. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO) Deworming for Health and Development: Report of the Third Global Meeting of the Partners for Parasite Control. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Guidelines for the Safe Use of Wastewater, Excreta and Greywater. II. World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for the Safe Use of Wastewater, Excreta and Greywater: Wastewater Use in Agriculture. Vol. 2. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. (WHO Guidel. Safe Use Wastewater, Excreta Greywater). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailenger J. Mechanisms of parasitical concentration in coprology and their practical consequences. Journal of the American Medical Technologists. 1979;41(2):65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouhoum K., Schwartzbrod J. Quantification of helminth eggs in waste water. Zentralblatt fur Hygiene und Umweltmedizin. 1989;188(3-4):322–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayres R. M., Mara D. D. Analysis of Wastewater for Use in Agriculture—A Laboratory Manual of Parasitological and Bacteriological Techniques. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demeke T., Jenkins G. R. Influence of DNA extraction methods, PCR inhibitors and quantification methods on real-time PCR assay of biotechnology-derived traits. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2010;396(6):1977–1990. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-3150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hung Y. W., Remais J. Quantitative detection of Schistosoma japonicum cercariae in water by real-time PCR. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2008;2(11, article e337) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basuni M., Muhi J., Othman N., et al. A pentaplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of four species of soil-transmitted helminths. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2011;84(2):338–343. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon C. A., Gray D. J., Gobert G. N., McManus D. P. DNA amplification approaches for the diagnosis of key parasitic helminth infections of humans. Molecular and Cellular Probes. 2011;25(4):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mejia R., Vicuña Y., Broncano N., et al. A novel, multi-parallel, real-time polymerase chain reaction approach for eight gastrointestinal parasites provides improved diagnostic capabilities to resource-limited at-risk populations. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2013;88(6):1041–1047. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verweij J. J., Stensvold C. R. Molecular testing for clinical diagnosis and epidemiological investigations of intestinal parasitic infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2014;27(2):371–418. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00122-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cimino R. O., Jeun R., Juarez M., et al. Identification of human intestinal parasites affecting an asymptomatic peri-urban Argentinian population using multi-parallel quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Parasites and Vectors. 2015;8(1, article 380) doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0994-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Easton A. V., Oliveira R. G., O'Connell E. M., et al. Multi-parallel qPCR provides increased sensitivity and diagnostic breadth for gastrointestinal parasites of humans: field-based inferences on the impact of mass deworming. Parasites and Vectors. 2016;9(1, article 38) doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1314-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon C. A., McManus D. P., Acosta L. P., et al. Multiplex real-time PCR monitoring of intestinal helminths in humans reveals widespread polyparasitism in Northern Samar, the Philippines. International Journal for Parasitology. 2015;45(7):477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jothikumar N., Mull B. J., Brant S. V., et al. Real-time PCR and sequencing assays for rapid detection and identification of avian schistosomes in environmental samples. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2015;81(12):4207–4215. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00750-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gyawali P., Ahmed W., Sidhu J. P. S., et al. Quantitative detection of viable helminth ova from raw wastewater, human feces, and environmental soil samples using novel PMA-qPCR methods. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2016;23(18):18639–18648. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-7039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts C. H., Last A., Molina-Gonzalez S., et al. Development and evaluation of a next-generation digital PCR diagnostic assay for ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2013;51(7):2195–2203. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00622-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utokaparch S., Sze M. A., Gosselink J. V., et al. Respiratory viral detection and small airway inflammation in lung tissue of patients with stable, mild COPD. COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2014;11(2):197–203. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2013.836166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sze M. A., Abbasi M., Hogg J. C., Sin D. D. A comparison between droplet digital and quantitative PCR in the analysis of bacterial 16S load in lung tissue samples from control and COPD GOLD 2. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110351.e110351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoshino T., Inagaki F. Molecular quantification of environmental DNA using microfluidics and digital PCR. Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 2012;35(6):390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksson S., Graf E. H., Dahl V., et al. Comparative analysis of measures of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 eradication studies. PLoS Pathogens. 2013;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003174.e1003174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinheiro L. B., Coleman V. A., Hindson C. M., et al. Evaluation of a droplet digital polymerase chain reaction format for DNA copy number quantification. Analytical Chemistry. 2012;84(2):1003–1011. doi: 10.1021/ac202578x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiria A. E., Prasetyani M. A., Hamid F., et al. Does treatment of intestinal helminth infections influence malaria? Background and methodology of a longitudinal study of clinical, parasitological and immunological parameters in Nangapanda, Flores, Indonesia (ImmunoSPIN Study) BMC Infectious Diseases. 2010;10, article 77 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W., Li D., Twieg E., Hartung J. S., Levy L. Optimized quantification of unculturable Candidatus Liberibacter spp. in host plants using real-time PCR. Plant Disease. 2008;92(6):854–861. doi: 10.1094/pdis-92-6-0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pecson B. M., Barrios J. A., Johnson D. R., Nelson K. L. A real-time PCR method for quantifying viable Ascaris eggs using the first internally transcribed spacer region of ribosomal DNA. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72(12):7864–7872. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01983-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diehl F., Diaz L. A., Jr. Digital quantification of mutant DNA in cancer patients. Current Opinion in Oncology. 2007;19(1):36–42. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328011a8e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhat S., Herrmann J., Armishaw P., Corbisier P., Emslie K. R. Single molecule detection in nanofluidic digital array enables accurate measurement of DNA copy number. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2009;394(2):457–467. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hindson C. M., Chevillet J. R., Briggs H. A., et al. Absolute quantification by droplet digital PCR versus analog real-time PCR. Nature Methods. 2013;10(10):1003–1005. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmermann B. G., Grill S., Holzgreve W., Zhong X. Y., Jackson L. G., Hahn S. Digital PCR: A powerful new tool for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis? Prenatal Diagnosis. 2008;28(12):1087–1093. doi: 10.1002/pd.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen F., Davydova E. K., Du W., Kreutz J. E., Piepenburg O., Ismagilov R. F. Digital isothermal quantification of nucleic acids via simultaneous chemical initiation of recombinase polymerase amplification reactions on SlipChip. Analytical Chemistry. 2011;83(9):3533–3540. doi: 10.1021/ac200247e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White R. A., Quake S. R., Curr K. Digital PCR provides absolute quantitation of viral load for an occult RNA virus. Journal of Virological Methods. 2012;179(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayden R. T., Gu Z., Ingersoll J., et al. Comparison of droplet digital PCR to real-time PCR for quantitative detection of cytomegalovirus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2013;51(2):540–546. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02620-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Straub T., Baird C., Bartholomew R. A., et al. Estimated copy number of Bacillus anthracis plasmids pXO1 and pXO2 using digital PCR. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2013;92(1):9–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hindson B. J., Ness K. D., Masquelier D. A., et al. High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Analytical Chemistry. 2011;83(22):8604–8610. doi: 10.1021/ac202028g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanders R., Huggett J. F., Bushell C. A., Cowen S., Scott D. J., Foy C. A. Evaluation of digital PCR for absolute DNA quantification. Analytical Chemistry. 2011;83(17):6474–6484. doi: 10.1021/ac103230c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whale A. S., Huggett J. F., Cowen S., et al. Comparison of microfluidic digital PCR and conventional quantitative PCR for measuring copy number variation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40(11):p. e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blaya J., Lloret E., Santísima-Trinidad A. B., Ros M., Pascual J. A. Molecular methods (digital PCR and real-time PCR) for the quantification of low copy DNA of Phytophthora nicotianae in environmental samples. Pest Management Science. 2016;72(4):747–753. doi: 10.1002/ps.4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson K. H., Blitchington R. B., Greene R. C. Amplification of bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA with polymerase chain reaction. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1990;28(9):1942–1946. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1942-1946.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai Y.-L., Olson B. H. Rapid method for separation of bacterial DNA from humic substances in sediments for polymerase chain reaction. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1992;58(7):2292–2295. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2292-2295.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tebbe C., Vahjen W. 1993 interference of humic acids and DNA extracted directly from soil in detection and transformation of recombinant DNA from bacteria and a yeast. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1993;59(8):2657–2665. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2657-2665.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watson R. J., Blackwell B. Purification and characterization of a common soil component which inhibits the polymerase chain reaction. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 2000;46(7):633–642. doi: 10.1139/w00-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.LaMontagne M. G., Michel F. C., Jr., Holden P. A., Reddy C. A. Evaluation of extraction and purification methods for obtaining PCR-amplifiable DNA from compost for microbial community analysis. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2002;49(3):255–264. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(01)00377-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howeler M., Ghiorse W. C., Walker L. P. A quantitative analysis of DNA extraction and purification from compost. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2003;54(1):37–45. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(03)00006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Renshaw M. A., Olds B. P., Jerde C. L., Mcveigh M. M., Lodge D. M. The room temperature preservation of filtered environmental DNA samples and assimilation into a phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol DNA extraction. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2015;15(1):168–176. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verweij J. J., Brienen E. A. T., Ziem J., Yelifari L., Polderman A. M., Van Lieshout L. Simultaneous detection and quantification of Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator americanus, and Oesophagostomum bifurcum in fecal samples using multiplex real-time PCR. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;77(4):685–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang J., Zhu Y., Wen H., et al. Quadruplex real-time PCR assay for detection and identification of Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 strains and determination of their toxigenic potential. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2009;75(22):6981–6985. doi: 10.1128/aem.00517-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fortin N., Beaumier D., Lee K., Greer C. W. Soil washing improves the recovery of total community DNA from polluted and high organic content sediments. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2004;56(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeandron A., Ensink J. H. J., Thamsborg S. M., Dalsgaard A., Sengupta M. E. A quantitative assessment method for Ascaris eggs on hands. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096731.e96731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blumenthal U. J., Mara D. D., Peasey A., Ruiz-Palacios G., Stott R. Guidelines for the microbiological quality of treated wastewater used in agriculture: recommendations for revising WHO guidelines. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78(9):1104–1116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raynal M., Villegas E. N., Nelson K. L. Enumeration of viable and non-viable larvated Ascaris eggs with quantitative PCR. Journal of Water and Health. 2012;10(4):594–604. doi: 10.2166/wh.2012.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schmitz B., Pearce-Walker J., Gerba C., Pepper I. A method for determining Ascaris viability based on early-to-late stage in-vitro ova development. Journal of Residuals Science & Technology. 2016;13(4):275–286. doi: 10.12783/issn.1544-8053/13/4/5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]