Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The aim of this study was to analyse the impact of hiatal hernia repair (HHR) on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in morbidly obese patients with hiatus hernia undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG).

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

It is a retrospective study involving ten morbidly obese patients with large hiatus hernia diagnosed on pre-operative endoscopy who underwent LSG and simultaneous HHR. The patients were assessed for symptoms of GERD using a Severity symptom score (SS) questionnaire and anti-reflux medications.

RESULTS:

Of the ten patients, five patients had GERD preoperatively. At the mean follow-up of 11.70 ± 6.07 months after surgery, four patients (80%) showed complete resolution while one patient complained of persistence of symptoms. Endoscopy in this patient revealed resolution of esophagitis indicating that the persistent symptoms were not attributable to reflux. The other five patients without GERD remained free of any symptom attributable to GERD. Thus, in all ten patients, repair of hiatal hernia (HH) during LSG led to either resolution of GERD or prevented any new onset symptom related to GER.

CONCLUSION:

In morbidly obese patients with HH with or without GERD undergoing LSG, repair of the hiatus hernia helps in amelioration of GERD and prevents any new onset GER. Thus, the presence of HH should not be considered as a contraindication for LSG.

Keywords: Gastro-oesophageal reflux, hiatus hernia, sleeve gastrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is associated with multiple comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnoea and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Hiatal hernia (HH) and GERD are closely related.[1] Obesity is known to be an independent risk factor for the development of both GERD and HH.[2] HH is present in about 37%–50% of morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery[3,4,5] while 50%–70% of the patients undergoing this surgery have symptomatic reflux.[6,7] Laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery with HH repair (HHR) is generally the standard of care for the management of GERD. However, in morbidly obese patients with HH and/or GERD, bariatric surgery is the preferred treatment modality.[8,9,10] Laparoscopic roux-en-y bypass (LRYGB) with or without crural closure is known to improve GERD and HH.[11,12,13,14,15,16] However, there are few studies which address the impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) with crural closure on GERD in morbidly obese patients having HH. Moreover, the results of these studies are conflicting.[2,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] In this study, we retrospectively analysed the symptoms of GERD and use of anti-reflux medications (ARM) in morbidly obese patients with large hiatus hernia and who underwent concomitant HHR with LSG for morbid obesity at our centre.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

With an experience of over 500 LSG procedures performed at our centre and increasing attention to the issue of GERD after LSG, we retrospectively analysed the impact of HHR on patients undergoing this procedure. We follow the standard National Institute of Health Guidelines for bariatric surgery which include patients with morbid obesity defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥40 kg/m2 and patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities.

A routine pre-operative endoscopy is carried out in all the patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

Ten patients were identified to have a large HH (>3 cm) on pre-operative endoscopy. The presence of HH was confirmed intraoperatively. All patients underwent LSG with primary posterior crural closure after meticulous dissection to ensure adequate intra-abdominal length of oesophagus. The sleeve was created in the standard fashion over a 36-F bougie starting at 4–5 cm from pylorus. The staple line was not reinforced. Hiatal crural defect was primarily repaired posteriorly with two or three interrupted non-absorbable sutures between the right and left diaphragmatic pillars over 36 Fr bougie.

All the patients were administered oral pantoprazole at a dose of 40 mg daily for 6 weeks after LSG.

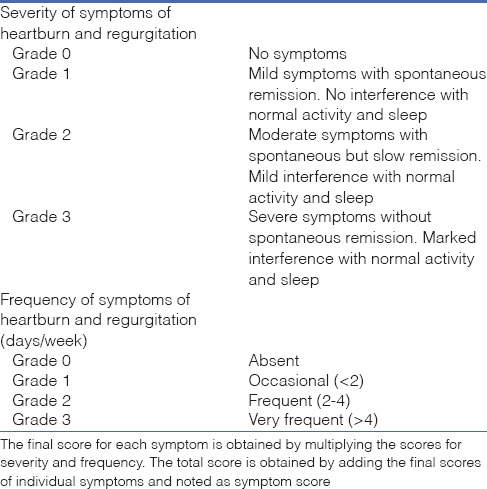

For the purpose of the study, all patients underwent assessment and grading of reflux symptoms using symptom score (SS) questionnaire [Table 1]. This standardised questionnaire, designed and validated by one of the co-authors at our centre, uses a simple system of grading of symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation based on severity and frequency of symptoms. A score ≥4 is considered positive for GERD.[24,25] Recall method was used to assess the pre-operative symptoms, and follow-up evaluation for all patients was done at least 3 months after surgery.

Table 1.

Severity symptom score used to assess gastroesphageal reflux disease

The details of the patients including demographic details, weight loss, pre-operative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) findings, SS score and use of ARM were recorded in a pre-designed pro forma.

All data were collected and entered in a computer database using the Microsoft Office Excel programme and then analysed using SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Data were first analysed using descriptive statistics. Non-parametric Wilcoxon-signed rank test was used to compare GERD SS score preoperatively and postoperatively. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Ten patients with equal number of males and females were included in the study. The mean age was 42.60 ± 14.39 years (range: 22–61 years). The mean pre-operative weight was 120.14 ± 23.71 kg (range: 97.5–173) and mean pre-operative BMI was 45.83 ± 9.28 kg/m2 (range: 33.46–67.58). The mean follow-up period was 11.70 ± 6.07 months (range: 3–18). The mean weight loss at the time of follow-up was 38.19 ± 12.60 kg (range: 14.5–55.6). Of the ten patients, five patients were diagnosed as GERD preoperatively based on a score >4 as assessed by SS questionnaire. All these five patients were using ARM, i.e., proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). In post-operative period, out of five patients diagnosed to have GERD, four patients (80%) showed complete resolution while one patient showed persistence of symptoms of GERD with SS of 8. Further evaluation of this patient with post-operative UGIE showed a complete resolution of esophagitis with no evidence of HH. This patient had a Los Angeles Grade B esophagitis in the pre-operative endoscopy. Among the other five patients who did not have GERD preoperatively, four patients (80%) did not complain any ‘de novo’ symptoms of GERD or use of ARM at the time of follow-up. One patient out of these five patients complained of symptoms including dyspepsia and pain in the right hypochondrium in the post-operative period. On evaluation, the patient was found to have symptomatic gallstone disease (GSD). The patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy at 9 months after bariatric surgery. At the time of the study (12 months after surgery), patient's symptoms have improved with SS score of 2. This patient does not use ARM routinely.

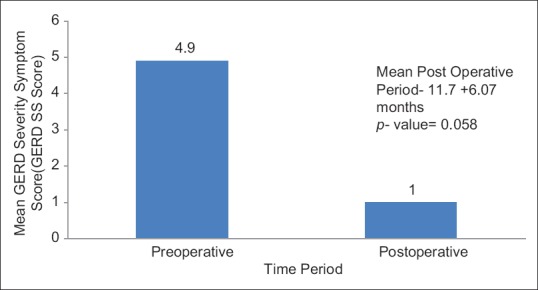

Figure 1 shows the mean pre- and post-operative GERD SS scores. Using Wilcoxon-signed rank test, there was trend approaching to be significant (P = 0.058) in improvement of GERD after concomitant LSG and HHR.

Figure 1.

Graph depicting comparison of mean pre- and post-operative gastroesophageal reflux disease severity-symptom (SS) scores

DISCUSSION

The problem of GERD following LSG is an unresolved issue. LSG has been shown to be associated with the development of GERD and frequent use of ARM in post-operative period.[26,27] In a multicentric study on the use of ARM 1 year after bariatric surgery, 6410 patients undergoing LRYGB, 2627 undergoing laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), 1567 undergoing LSG and 162 undergoing biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch were analysed. The study concluded a higher likelihood of use of ARM 1 year after LSG (odds ratio = 1.70, 95% confidence interval, 0.45–1.99) as compared to LAGB. LSG was concluded as a significant predictor for ARM use 1 year after surgery even after adjustment for concomitant HHR.[3] In another review studying the impact of various bariatric procedures (excluding HHR) in 22,870 patients with a mean follow-up of 6 months, LRYGB showed best improvement in GERD with 56.5% followed by LAGB (46%) and LSG (41%).[28] In a previous prospective study at our centre, we showed improvement in GERD based on SS score as well as improvement in grade of esophagitis on UGIE in 32 patients undergoing LSG for morbid obesity.[29] This improvement was despite radionuclide scintigraphy showing a significant increase in gastroesophageal reflux from 6.25% to 78.1% in post-operative period. The possible explanation for the paradoxical findings was that the scintigraphic reflux might not be pathological as there was decreased total acid production after LSG. The post-prandial distress rather than GERD was the main complaint after LSG as reported by Carabotti et al.[30]

The impact of LSG on GERD is hence unclear. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed for improvement in GERD following LSG. These include faster gastric emptying, reduced reservoir function of stomach and decreased acid production. A lowering of intra-abdominal pressure as a result of significant weight loss also contributes to the improvement of GERD. On the contrary, worsening of GERD has been attributed to the presence of HH and increased intraluminal pressure as a result of conversion of the stomach into a straight tubular segment of smaller capacity. Some of the sling fibres get sectioned during surgery and may contribute to increase in GERD.[29]

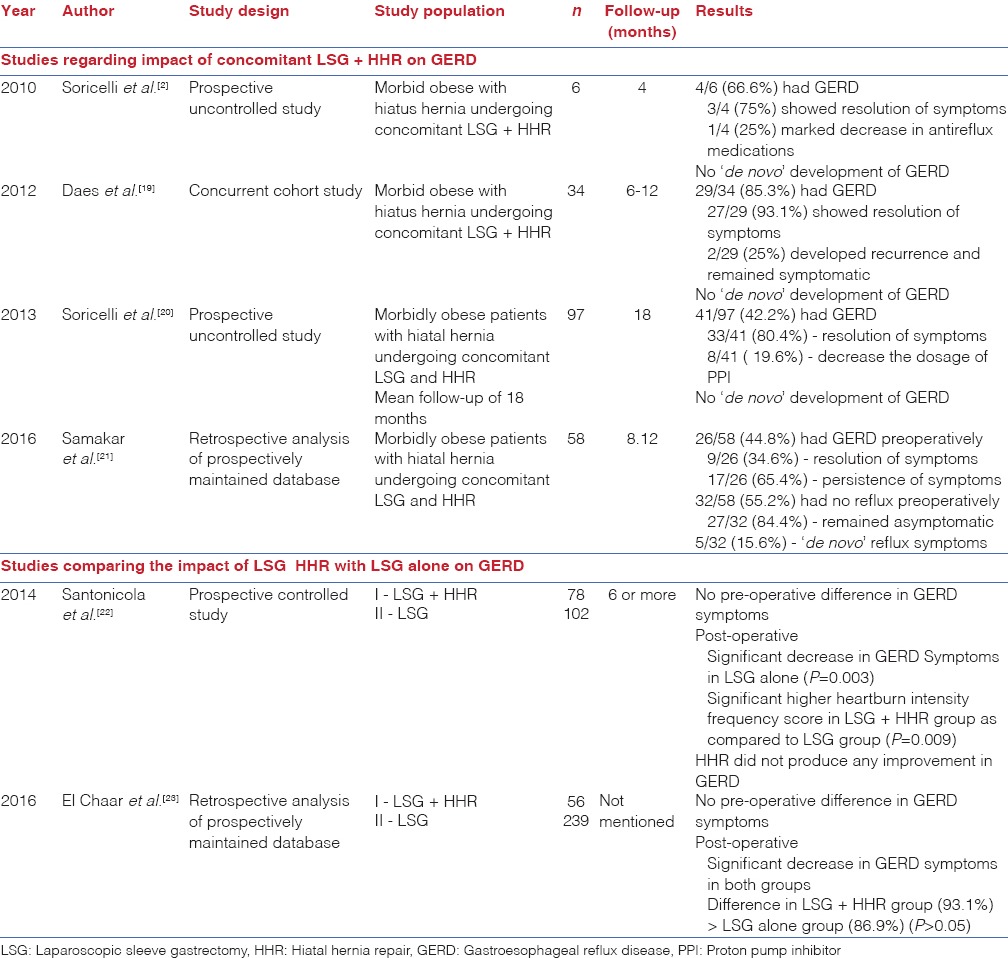

The presence of HH further complicates the management strategy of GERD in morbidly obese patients undergoing LSG. As per the International Sleeve Gastrectomy Consensus statement,[31] aggressive identification of HH should be done and if found, should always be repaired. If HH is identified, dissection should be carried out posteriorly to allow appropriate posterior crural closure. However, there are few studies addressing the impact of synchronous LSG and HHR on GERD. Table 2 shows the various studies regarding the impact of concomitant LSG and HHR on GERD.

Table 2.

Studies regarding impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with or without hiatal hernia repair on gastroesophageal reflux disease in morbidly obese patients

Korwar et al. performed concomitant HHR with LSG in a 36-year-old female with GERD which showed complete resolution of symptoms of GERD in post-operative period.[17] Cuenca-Abente et al. performed LSG and crural repair in a 70-year-old obese patient (BMI - 46 kg/m2) for symptomatic recurrence after open Nissen fundoplication.[18] The patient showed complete resolution of the symptoms 18 months after surgery. Soricelli et al. studied six morbid obese patients with HH undergoing LSG and HHR at the same time.[2] Four patients were symptomatic for GERD and were diagnosed with HH preoperatively while two other asymptomatic patients were diagnosed with HH intraoperatively. Laparoscopic crural closure was done in all cases with two cases involving prosthetic reinforcement. At mean follow -up of 4 months, symptoms of GERD resolved in three out of four symptomatic patients while the other symptomatic patient showed improvement in reflux symptoms well controlled by minimal dose of PPI (15 mg/day). In five out of six cases, there was no recurrence of HH identified using UGIE 1 month after surgery. Daes et al. also studied 34 patients undergoing concomitant LSG with HHR and reported the decrease in the incidence of GERD from 85.3% to 5.8% in the post-operative period at a mean follow-up of 6–12 months.[19] Later, Soricelli et al. further expanded their work by studying 378 patients undergoing LSG, out of which 97 patients had HH.[20] About 41 of these 97 patients (42.2%) had typical symptoms of GERD. After LSG and HHR, 33 of 41 patients (80.4%) having GERD showed resolution of symptoms while the remaining eight patients (19.6%) showed decrease in the dosage of ARM (PPIs) from 40 mg/day to 15 mg/day. In patients undergoing LSG alone, 19 patients were symptomatic for GERD in the pre-operative period. Eleven out of 19 (57.8%) patients showed remission of GERD while GERD persisted in other 8 symptomatic patients. Significantly, ‘de novo’ development of GERD in patients undergoing LSG was 22.9% as compared to 0% in patients undergoing LSG with HHR. Our findings too echo the similar results. In our study, four out of five patients with GERD (80%) preoperatively were relieved symptomatically while only one patient did not improve (20%). Paradoxically, even this patient had resolution of esophagitis on endoscopy. Thus, his symptoms were not attributable to GER. No patient in our study showed development of new onset GERD after LSG and HHR. One patient complained of dyspepsia and pain in the right hypochondrium, which were later attributed to the presence of GSD. These symptoms improved after the patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy.[32] Moreover, the improvement in GERD after LSG with HHR showed a trend approaching to be statistically significant (P = 0.056).

However, there are studies with conflicting results. In a recent study by Samakar et al.[21] involving 58 patients undergoing simultaneous LSG with HHR, 26 (44.8%) had GERD preoperatively. Only 9 out of 26 patients (34.6%) showed resolution of GERD postoperatively while 5 out of 32 patients (15.6%) developed ‘de novo’ symptoms of reflux. Thus, the role of concomitant LSG + HHR needs to determined in a systematic fashion to reach a consensus.

Few studies have compared the impact of LSG + HHR with LSG alone on GERD. Santonicola et al.[22] compared 78 morbid obese patients with HH who underwent LSG with concomitant HHR (LSG + HHR group) with 102 patients without HH who underwent only LSG (LSG group). The prevalence of symptoms of GERD did not differ significantly between the two groups in pre-operative phase. At a follow-up of 6 months or more, they showed that there was a significant decrease in the prevalence of typical symptoms of GERD only in LSG group while LSG + HHR group showed increase in heartburn and regurgitation as compared to LSG group. Heartburn and regurgitation were significantly higher in patients with HH recurrence compared with those without HH recurrence as diagnosed using double contrast barium swallow in the post-operative period. However, El Chaar et al.[23] compared 56 patients undergoing concomitant anterior HHR with 239 patients undergoing LSG alone and observed a significant improvement in reflux symptoms in both the groups (P < 0.0001). They also found higher satisfaction score in group undergoing concomitant HHR as compared to those undergoing sleeve gastrectomy alone (93.1% vs. 86.9%, respectively), but it was statistically not significant. In our study, we did not compare the patients undergoing LSG + HHR with LSG alone.

The strengths of the study include the fact that only patients with preoperatively documented large HH were included for analysis as inclusion of patients with error-prone intra-operative diagnosis of hiatus hernia may not reflect the actual picture. Moreover, all the patients underwent the same standardised technique of posterior crural closure as the management strategy for HH. There are certain limitations of the study. The number of patients studied is small. The objective evaluation of symptoms of GERD using SS score was done in the post-operative period based on patient's recall. Moreover, we did not perform any post-operative investigations such as UGIE or barium swallow, except in one patient, to document any hiatus hernia recurrence. Patients in this study did not undergo oesophageal manometry or 24 h pH monitoring.

In spite of these shortcomings, we feel that our study has addressed the topic of grave importance when management of GERD in morbid obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery is concerned.

Further large-sized prospective studies focusing on standardised GERD questionnaires and objective evidence of GERD in pre- and post-operative periods with a long-term follow-up are indispensable to fully decipher the role of concomitant HHR so as to help in the formulation of guidelines in this regard.

CONCLUSION

In morbidly obese patients planned for bariatric surgery, presence of HH with or without GERD is not a contraindication for LSG. Concomitant LSG with HHR leads to improvement of GERD and also prevents de novo symptoms attributable to GER in asymptomatic patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Rachna Chaudhary, Bariatric Coordinator and Personal Secretary to Professor Sandeep Aggarwal, Department of Surgery, AIIMS, for her help and support throughout the project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soricelli E, Casella G, Rizzello M, Calì B, Alessandri G, Basso N. Initial experience with laparoscopic crural closure in the management of hiatal hernia in obese patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1149–53. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varban OA, Hawasli AA, Carlin AM, Genaw JA, English W, Dimick JB, et al. Variation in utilization of acid-reducing medication at 1 year following bariatric surgery: Results from the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:222–8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Che F, Nguyen B, Cohen A, Nguyen NT. Prevalence of hiatal hernia in the morbidly obese. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:920–4. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutta SK, Arora M, Kireet A, Bashandy H, Gandsas A. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms and associated disorders in morbidly obese patients: A prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1243–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0485-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frigg A, Peterli R, Zynamon A, Lang C, Tondelli P. Radiologic and endoscopic evaluation for laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: Preoperative and follow-up. Obes Surg. 2001;11:594–9. doi: 10.1381/09608920160557075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ovrebø KK, Hatlebakk JG, Viste A, Bassøe HH, Svanes K. Gastroesophageal reflux in morbidly obese patients treated with gastric banding or vertical banded gastroplasty. Ann Surg. 1998;228:51–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199807000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraser J, Watson DI, O’Boyle CJ, Jamieson GG. Obesity and its effect on outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14:50–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2001.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prachand VN, Alverdy JC. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and severe obesity: Fundoplication or bariatric surgery? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3757–61. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i30.3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patterson EJ, Davis DG, Khajanchee Y, Swanström LL. Comparison of objective outcomes following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus laparoscopic gastric bypass in the morbidly obese with heartburn. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1561–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8955-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry Y, Courcoulas AP, Fernando HC, Buenaventura PO, McCaughan JS, Luketich JD. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for recalcitrant gastroesophageal reflux disease in morbidly obese patients. JSLS. 2004;8:19–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvador-Sanchis JL, Martinez-Ramos D, Herfarth A, Rivadulla-Serrano I, Ibañez-Belenguer M, Hoashi JS. Treatment of morbid obesity and hiatal paraesophageal hernia by laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2010;20:801–3. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9656-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raftopoulos I, Awais O, Courcoulas AP, Luketich JD. Laparoscopic gastric bypass after antireflux surgery for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in morbidly obese patients: Initial experience. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1373–80. doi: 10.1381/0960892042583950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angrisani L, Iovino P, Lorenzo M, Santoro T, Sabbatini F, Claar E, et al. Treatment of morbid obesity and gastroesophageal reflux with hiatal hernia by Lap-Band. Obes Surg. 1999;9:396–8. doi: 10.1381/096089299765553007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landen S. Simultaneous paraesophageal hernia repair and gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2005;15:435–8. doi: 10.1381/0960892053576730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frezza EE, Barton A, Wachtel MS. Crural repair permits morbidly obese patients with not large hiatal hernia to choose laparoscopic adjustable banding as a bariatric surgical treatment. Obes Surg. 2008;18:583–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korwar V, Peters M, Adjepong S, Sigurdsson A. Laparoscopic hiatus hernia repair and simultaneous sleeve gastrectomy: A novel approach in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease associated with morbid obesity. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:761–3. doi: 10.1089/lap.2009.0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuenca-Abente F, Parra JD, Oelschlager BK. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: An alternative for recurrent paraesophageal hernias in obese patients. JSLS. 2006;10:86–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daes J, Jimenez ME, Said N, Daza JC, Dennis R. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux can be reduced by changes in surgical technique. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1874–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0746-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soricelli E, Iossa A, Casella G, Abbatini F, Calì B, Basso N. Sleeve gastrectomy and crural repair in obese patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and/or hiatal hernia. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:356–61. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samakar K, McKenzie TJ, Tavakkoli A, Vernon AH, Robinson MK, Shikora SA. The effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with concomitant hiatal hernia repair on gastroesophageal reflux disease in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 2016;26:61–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1737-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santonicola A, Angrisani L, Cutolo P, Formisano G, Iovino P. The effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy with or without hiatal hernia repair on gastroesophageal reflux disease in obese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:250–5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Chaar M, Ezeji G, Claros L, Miletics M, Stoltzfus J. Short-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in combination with hiatal hernia repair: Experience in a single accredited center. Obes Surg. 2016;26:68–76. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1739-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vigneri S, Termini R, Leandro G, Badalamenti S, Pantalena M, Savarino V, et al. A comparison of five maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1106–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510263331703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madan K, Ahuja V, Kashyap PC, Sharma MP. Comparison of efficacy of pantoprazole alone versus pantoprazole plus mosapride in therapy of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A randomized trial. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17:274–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2004.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nocca D, Krawczykowsky D, Bomans B, Noël P, Picot MC, Blanc PM, et al. A prospective multicenter study of 163 sleeve gastrectomies: Results at 1 and 2 years. Obes Surg. 2008;18:560–5. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9288-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arias E, Martínez PR, Ka Ming Li V, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Mid-term follow-up after sleeve gastrectomy as a final approach for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2009;19:544–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9818-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pallati PK, Shaligram A, Shostrom VK, Oleynikov D, McBride CL, Goede MR. Improvement in gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms after various bariatric procedures: Review of the bariatric outcomes longitudinal database. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:502–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma A, Aggarwal S, Ahuja V, Bal C. Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux before and after sleeve gastrectomy using symptom scoring, scintigraphy, and endoscopy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:600–5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carabotti M, Silecchia G, Greco F, Leonetti F, Piretta L, Rengo M, et al. Impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1551–7. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0973-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenthal RJ, Diaz AA, Arvidsson D, Baker RS, Basso N, Bellanger D, et al. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel. International sleeve gastrectomy expert panel consensus statement: Best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li VK, Pulido N, Martinez-Suartez P, Fajnwaks P, Jin HY, Szomstein S, et al. Symptomatic gallstones after sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2488–92. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]