Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Resident participation in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is one of the first steps of laparoscopic training. The impact of this training is not well-defined, especially in developing countries. However, this training is of critical importance to monitor surgical teaching programmes.

OBJECTIVE:

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of seniority on operative time and short-term outcome of LC.

DESIGNS AND SETTINGS:

We performed a retrospective study of all consecutive laparoscopic cholecystectomies for gallbladder lithiasis performed over 2 academic years in an academic Surgical Department in Morocco.

PARTICIPANTS:

These operations were performed by junior residents (post-graduate year [PGY] 4–5) or senior residents (PGY 6), or attending surgeons assisted by junior residents, none of whom had any advanced training in laparoscopy. All data concerning demographics (American Society of Anesthesiologists, body mass index and indications), surgeons, operative time (from skin incision to closure), conversion rate and operative complications (Clavien–Dindo classification) were recorded and analysed. One-way analysis of variance, Student's t-test and Chi-square tests were used as appropriate with statistical significance attributed to P < 0.05.

RESULTS:

One hundred thirty-eight LC were performed. No differences were found on univariate analysis between groups in demographics or diagnosis category. The overall rate of operative complications or conversions and hospital stay were not significantly different between the three groups. However, mean operative time was significantly longer for junior residents (n = 27; 115 ± 24 min) compared to senior residents (n = 37; 77 ± 35 min) and attending surgeons (n = 66; 55 ± 17 min) (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION:

LC performed by residents appears to be safe without a significant difference in complication rate; however, seniority influences operative time. This information supports early resident involvement in laparoscopic procedures and also the need to develop cost-effective laboratory training programmes.

Keywords: Developing country, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, resident teaching, seniority

INTRODUCTION

General surgeons competency is critically influenced by initial education and training programme quality.[1,2] These programmes are a priority for developing country health systems.[3,4,5] In Morocco, initial education and training of future general surgeons are provided by a residency programme of 6 years following medical school that includes laparoscopy training since 1992. Resident participation in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is one of the first steps of laparoscopic training.[6] Many authors reported the increase in operative time with resident participation; however, the global impact of this training is not well-defined, especially in developing countries.[7,8,9] These data are needed to monitor the quality of surgical teaching programmes.[7,6,8,10]

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of seniority on operative time and short-term outcome in LC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We retrospectively studied data obtained from a prospective database of all consecutive LC for gallbladder lithiasis performed between January 2011 and December 2012 in our academic tertiary Surgical Department.

Patients were mostly recruited for resident training purposes. Cholecystectomy indication was divided into two groups according to its difficulty: Non-inflammatory (biliary colic) and inflammatory (chronic or acute Grade I and II according to revised[11] Tokyo guidelines) based on pre-operative, intra-operative findings and histopathologic analysis of the specimen. LC associated with additional procedure including intra-operative cholangiography was excluded from the study.

The procedure is done in French position through 3 to 4 trocars (2 × 10 mm and 1-2 × 5 mm). Meticulous dissection of the cystic duct and artery was performed using monopolar energy hook to obtain a ‘critical view of safety’ whenever possible. Both elements are clipped and cut. Gallbladder specimen was retrieved through a bag from the operative trocar. Conversion decision to open cholecystectomy was decided when main bile duct injury was suspected, bleeding could not be managed laparoscopically or when dissection could not progress. Conversion decision needed systematic attending surgeon agreement. The intra-abdominal drainage is performed at the end of the procedure, and it is retrieved on the 2nd post-operative day.

Study population was divided into three groups according to surgical seniority: Post-graduate year (PGY) 4–5 residents (junior residents), PGY 6 residents (senior residents) and professors (attending surgeons). Residents performed LC without attending surgeons’ however could ask for their assistance anytime during the procedure. None of the residents had received any specific advanced laparoscopic training at the time of the study.

All data concerning patients (age, sex, body mass index and American Society Association score, previous upper abdominal surgery and inflammatory cholecystitis), the surgical procedure (operative time from incision to skin closure, estimated blood loss, conversion to open cholecystectomy and rate of intra-operative drainage) and post-operative outcomes (complications according to Clavien–Dindo classification, hospital stay and readmission rate) were analysed.

Statistical analysis used SPSS software, version 21.0.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were presented as mean value ± standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. Data were compared using one-way analysis of variance between the three study groups, Student's t-test and Chi-square tests were used when appropriate with statistical significance attributed to P < 0.05. Post hoc Bonferroni test was used when needed.

RESULTS

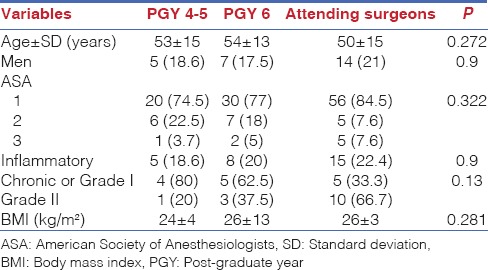

A total of 134 LC without intra-operative cholangiography were extracted from a prospective all-intervention database in our department from January 2011 to December 2012. Junior residents (PGY 4–5), senior residents (PGY 6) and attending surgeons performed, respectively, 27, 37 and 66 LC. Demographics of patient were not statistically significant between the three groups, however attending surgeons operated more Grade II acute cholecystitis (respectively, 66.7, 37.5 and 20%; P = 0.13) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Details of demographics and characteristic of the study groups: Post-graduate year 4-5 residents (junior residents), post-graduate year 6 residents (senior residents) and professors (attending surgeons)

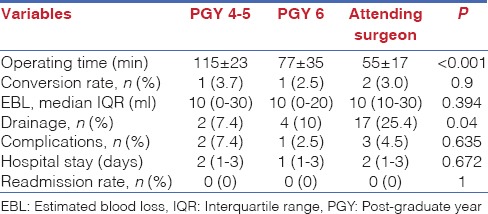

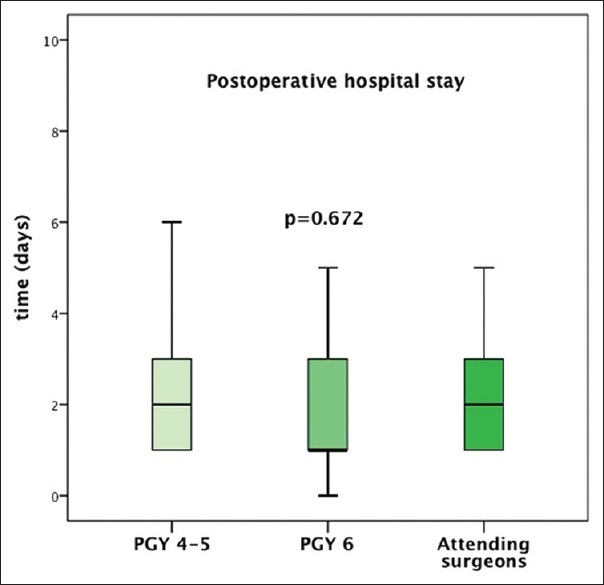

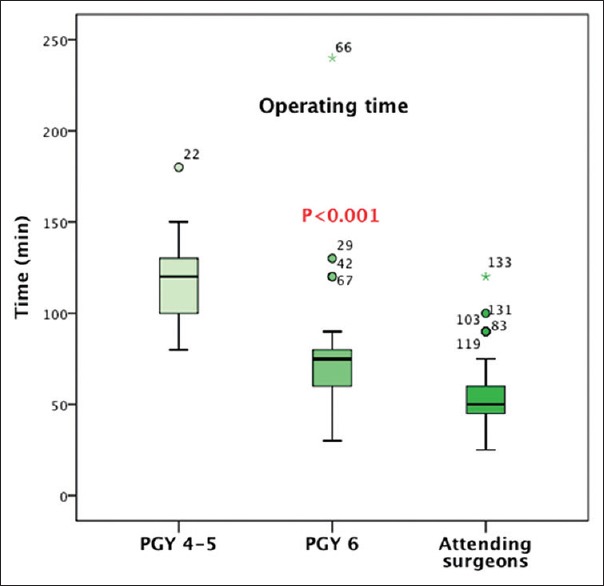

There was no post-operative mortality. Minor post-operative complications (Clavien–Dindo <3) occurred in six patients (4%). There was no bile duct injury. Demographics, cholecystitis distribution, rate of post-operative complications, rate of conversion to open cholecystectomy, estimated blood loss and hospital stay were not statistically different between the three groups on univariate analysis [Table 2]. Figure 1: postoperative hospital stay; Significant mean operative time difference was found between the three groups: Almost 2 h (115 ± 24 min) for junior residents, <1 h (55 ± 17 min) for attending surgeons and intermediate operative time of 77 ± 35 min for senior residents (P < 0.001) [Figure 2]: operating time. At the opposite drainage, rate was also higher in attending surgeons group than senior and junior groups, respectively, 25.4%, 10% and 7.4% (P = 0.04).

Table 2.

Details of the procedure, hospital stay and short-term outcomes compared according to the study groups: Post-graduate year 4-5 residents (junior residents), post-graduate year 6 residents (senior residents) and professors (attending surgeons)

Figure 1.

Distribution of post-operative hospital stay according to study groups: Group of post-graduate 4–5, post-graduate 6 and attending surgeons. The boxes are defined by the 25th and 75th percentiles. The lines inside the boxes represent the median times. The error bars represent the largest values not more than 1.5 times the length of the box from the quartiles

Figure 2.

Distribution of operating time according to study groups: Group of post-graduate 4–5, post-graduate 6 and attending surgeons. The boxes are defined by the 25th and 75th percentiles. The lines inside the boxes represent the median times. The error bars represent the largest values not more than 1.5 times the length of the box from the quartiles

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that LC performed by residents appears to be safe and that seniority impacts operative time but not complication rate.

Attending surgeons used routine drainage of the abdominal cavity more than senior and junior groups, respectively, in 25.5%, 10% and 7.4% of the cases (P = 0.04). This fact may be related to the higher rate of Grade II cholecystitis in attending surgeons compared to senior and junior resident groups even not statistically significant (respectively, 66.7, 37.5 and 20%; P = 0.13).

Many surgeons believe that routine intra-abdominal drainage after LC for acute cholecystitis may prevent post-operative intra-abdominal infection. This old dogma was recently questioned by Park et al. that demonstrated no benefit of systematic drain in preventing complications.[12]

Our study showed that operative time and room occupation are doubled between junior residents and attending surgeons. This time, variability decreased as residents gained experience in performing LC during their surgical training programme.[8,13]

This fact should lead department staff to support early resident involvement in laparoscopic procedures and the need to develop laboratory training programmes, especially in developing country.[5,14,15] Intensive animal training may also help to practice the procedure before trying on patients.[16]

Thus, this early initiation to laparoscopic skills can address prolonged procedures and subsequent costs issues and also save time during the residency for more advanced procedures training.[16]

Moreover, LC training programmes evaluation should not only focus on operative time and immediate costs but also on prevention of bile duct injury. This purpose is ensured by LC procedure technical (safe dissection and use of monopolar cautery, recognition of biliary anatomy) and behavioural (adequate decision and timing to convert or to ask for support) standardisation.[17]

A comment should be made concerning the teaching environment in the operating room in Morocco. Since surgical maturity is reached during the 4th and 5th year, residents are allowed to perform the total surgical procedures helped by PGY 1 and 2 chaperoned by an attending surgeon that would be called before any conversion. This fact may explain the increased operative time between PGY 4–5 and attending surgeons (115 min vs. 55 min). In all the other studies during LC procedures, residents are permitted to perform tasks and complete the operation; however, the attending surgeon may intervene to assist or complete these tasks leaving a minor role to young residents.[7,6,10]

In this study, PGY 6 represents the final year of residency, just before the surgical specialization, as an intermediate state between young resident and attending surgeons. These residents performed more easily and faster the LC procedure with the same safety than PGY 4–5. This fact may be a surrogate of the efficiency of laparoscopic teaching programme.

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective aspect and its small number of patients. Moreover, this study could be enlarged to include other basic procedure performed by PGY 4–5 as hernia repair or laparoscopic appendectomy.

CONCLUSION

This study provides data that support the importance of early involvement in laparoscopic surgery to reduce the financial impact of educating residents in the operative room and accelerate safely, the access for more laparoscopic advanced procedures. These facts should also lead department staff to consider surgical seniority when scheduling LC for residents.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Hady Saheb for his help rewieing this manuscript and Mrs H Benkhouya and Y. Bensouda for their unconditional supports.

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott-Conner CE, Hall TJ, Anglin BL, Muakkassa FF, Poole GV, Thompson AR, et al. The integration of laparoscopy into a surgical residency and implications for the training environment. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:1054–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00705718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung R, Pham Q, Wojtasik L, Chari V, Chen P. The laparoscopic experience of surgical graduates in the United States. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1792–5. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8922-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chauhan A, Mehrotra M, Bhatia PK, Baj B, Gupta AK. Day care laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A feasibility study in a public health service hospital in a developing country. World J Surg. 2006;30:1690–5. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brekalo Z, Innocenti P, Duzel G, Liddo G, Ballone E, Simunovic VJ. Ten years of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A comparison between a developed and a less developed country. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:722–8. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0906-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manning RG, Aziz AQ. Should laparoscopic cholecystectomy be practiced in the developing world?: The experience of the first training program in Afghanistan. Ann Surg. 2009;249:794–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a3eaa9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis SS, Jr, Husain FA, Lin E, Nandipati KC, Perez S, Sweeney JF. Resident participation in index laparoscopic general surgical cases: Impact of the learning environment on surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babineau TJ, Becker J, Gibbons G, Sentovich S, Hess D, Robertson S, et al. The “cost” of operative training for surgical residents. Arch Surg. 2004;139:366–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kauvar DS, Braswell A, Brown BD, Harnisch M. Influence of resident and attending surgeon seniority on operative performance in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Res. 2006;132:159–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.11.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseng WH, Jin L, Canter RJ, Martinez SR, Khatri VP, Gauvin J, et al. Surgical resident involvement is safe for common elective general surgery procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang WN, Melkonian MG, Marshall R, Haluck RS. Postgraduate year does not influence operating time in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Res. 2001;101:1–3. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayumi T, Someya K, Ootubo H, Takama T, Kido T, Kamezaki F, et al. Progression of Tokyo guidelines and Japanese guidelines for management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J UOEH. 2013;35:249–57. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.35.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JS, Kim JH, Kim JK, Yoon DS. The role of abdominal drainage to prevent of intra-abdominal complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: Prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:453–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkiemeyer M, Pappas TN, Giobbie-Hurder A, Itani KM, Jonasson O, Neumayer LA. Does resident post graduate year influence the outcomes of inguinal hernia repair? Ann Surg. 2005;241:879–82. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000164076.82559.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okrainec A, Smith L, Azzie G. Surgical simulation in Africa: The feasibility and impact of a 3-day fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery course. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2493–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQueen KA, Hyder JA, Taira BR, Semer N, Burkle FM, Jr, Casey KM. The provision of surgical care by international organizations in developing countries: A preliminary report. World J Surg. 2010;34:397–402. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmerman H, Latifi R, Dehdashti B, Ong E, Jie T, Galvani C, et al. Intensive laparoscopic training course for surgical residents: Program description, initial results, and requirements. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3636–41. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neychev V, Saldinger PF. Raising the thinker: New concept for dissecting the cystic pedicle during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1441–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]