Abstract

The term “Primary Cutaneous B-Cell Lymphoma” (PCBCL) comprehends a variety of lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by a clonal proliferation of B-cells primarily involving the skin. The absence of evident extra-cutaneous disease must be confirmed after six-month follow-up in order to exclude a nodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) with secondary cutaneous involvement, which may have a completely different clinical behavior and prognosis. In this article, we have summarized the clinico-pathological features of main types of PCBCL and we outline the guidelines for management based on a review of the available literature.

Keywords: Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma, Primary Cutaneous Marginal zone Lymphoma, Primary cutaneous follicle-center lymphoma, Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma leg type, Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B cell Lymphoma other

Introduction

What was known?

Under the 4th World Health Organization classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, cutaneous B-cell lymphomas are classified in: primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (PCMZL), primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (PCDLBCL) leg type (LT) and primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, other.

The absence of evident extra-cutaneous disease is a necessary condition for the diagnosis of CBCL because they have a completely different clinical behavior and prognosis from nodal counterpart.

The term “primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma” (PCBCL) comprehends a variety of lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by a clonal proliferation of B-cells, which primarily involves the skin. In the late 1980s, cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) were for the first time recognized as an autonomous clinical entity based on homogeneous clinical and prognostic characteristics, with an overall better disease course if compared with nodal counterparts.[1,2] The absence of evident extracutaneous disease is a necessary condition for the diagnosis of PCBCL to be confirmed after 6-month follow-up to exclude a nodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) with secondary cutaneous involvement[2] that may have a completely different clinical behavior and prognosis.

Classification

Nowadays, long debate has been made about pathologic classification of PCBCL. Due to the different clinical behavior, the distinction of cutaneous lymphomas from nodal counterparts is mandatory to settle the optimal treatment, but it is a relatively recent achievement. In fact, both Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms[3] and World Health Organization (WHO)[4] classifications for NHLs do not deal specifically with cutaneous lymphomas even if they can be adapted to include most of the entities primarily involving the skin. Applying the same terminology used in nodal lymphoma classification, the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) proposed a new classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas.[5] Conversely, in 2001, the WHO proposed a unified system that referred to both extranodal (including primary cutaneous) and nodal lymphomas adopting a similar terminology.[6] The differences among original EORTC and WHO CBCL's classifications lead to confusion.[7] For example, many lesions classified as “follicle center cell lymphoma” in the original EORTC classification and may be classified as “diffuse large B-cell lymphoma” (DLBCL) in the WHO classification and, in contrast with their nodal counterpart, they exhibit clinically indolent behavior and respond to radiotherapy without need of systemic chemotherapy.[8] The definition of “large B-cell lymphoma of the leg” can easily show the intrinsic limits of the original EORTC classification. “Large B-cell lymphoma of the leg” was defined CBCL with preponderance of large B-cells arising in the lower extremities. Based on this criteria, histologically, identical lesions would be classified as “large B-cell lymphoma of the leg” if located on the lower extremities and “follicle center cell lymphoma” if located elsewhere.[8]

In response to the need of a univocal and comprehensive classification solely devoted to primary cutaneous lymphoma, the WHO-EORTC published in 2005 the unified classification for primary cutaneous lymphoma.[9] These guidelines were incorporated into the revised 4th WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008 using the framework for nodal lymphomas.[10] Under this classification, primary cutaneous lymphoma are divided into cutaneous T-cell and natural killer-cell lymphomas, CBCLs, and precursor hematologic neoplasm. The CBCLs are classified into primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (PCMZL), primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL), primary cutaneous DLBCL (PCDLBCL), leg type (LT), and PCDLBCL, other.[9,10]

Epidemiology

PCBCLs represent up to 25%–29% of primary cutaneous lymphomas,[11] for which an estimated annual incidence of 0.5–1 new case/100,000 has been reported.[12,13]

Three of the main European works analyzing the occurrences of cutaneous lymphomas published in 1983,[14] 1984,[15] and 1997[16] reported, respectively, a 25%, 32%, and 20.8% of B-cells lymphomas. In 1997, Willemze et al.[5] reported that B-cell lymphomas represent the 18.8% of diagnosis in 626 patients registered by the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Working Group between 1986 and 1994. Zackheim et al.[12] reviewing data from three United States (US) institutions with active PCBCLs found a considerably lower (4.5%) relative frequency of PCBCL in the US. The first large population-based study focusing on cutaneous lymphoma in the USA[11] reported that CBCLs accounted for 29% (IR = 3.1/1,000,000 person-years) of the 3884 cutaneous lymphomas registered. In recent retrospective studies from Japan and Korea,[17,18] lower rates of PCBCL were found when compared to those reported in Western countries. Thus, the etiology of cutaneous lymphoma subtypes remains largely unknown, comparison of incidence rates, and patterns for specific subtypes may elucidate important clues for future studies.[11]

PCBCL are more common in male and, in contrast to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, they are almost exclusively a disease of non-Hispanic White.[11] Consisting with previous reports,[19,20] Bradford et al.[11] found that the rates of CBCL steadily rose with age. Chronic inflammation, DNA damage, and diminished immune surveillance that occur with older age may contribute to lymphoma development.[11]

Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone Lymphoma

Introduction

PCMZL is defined by the 2008 WHO classification for hematopoietic and lymphoproliferative disorders[10] as an indolent B-cell lymphoma composed of small B-cells, lymphoplasmacytoid cells, and mature plasma cells.[9,21] It is included in the group of extranodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.[10,22] However, it has been debated since its first descriptions if PCMZL really shares pathogenic mechanisms and biological similitudes with systemic MALT counterpart, or it has to be considered a completely distinct entity, based on evidence of different translocations, expression of class-switched immunoglobulins (Igs), chemokine receptors, association with infective triggers.[23,24]

Clinical appearance

PCMZL presents as single or more often multifocal, asymptomatic, or slightly itchy lesions that tend to Table 2 enlarge slowly and may reach over 3 cm of diameter. They appear as erythemato-cyanotic papules or nodules with shiny surface and no desquamation, more frequently localized at the arms or trunk. Rarely, PCMZL may present as multiple erythematous Figure 1 papules localized symmetrically on the face and thus mimicking granulomatous rosacea (PCMZL agminate). Furthermore, in patients which show serological positivity to antiphospholipid antibodies classical lesions associated with anetodermic scar.[25,26,27]

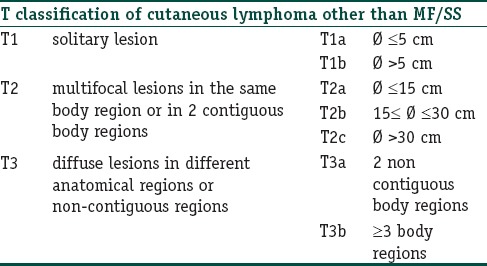

Table 2.

Tumor node metastases (TNM) classification of cutaneous lymphoma other than mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome

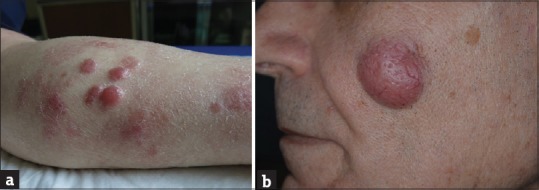

Figure 1.

Clinical presentation of primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma with an erythematous plaque (right arm) and nodular lesion with shiny surface and no desquamation (left arm)

Histopathology

PCMZL is characterized by nodular infiltration of dermis and subcutis Figure 2 by small lymphocytic cells, lymphoplasmacytoid cells, mature plasma cells, and reactive germinal centers with macrophages.[21,28] The infiltrate could be intermingled with a reactive T-cell infiltrate, in some cases almost totally obscuring the neoplastic B-cells. It could also be observable a diffuse plasmacytoid differentiation.[29] At immunohistochemistry, tumor cells show positivity for CD20, CD79a, and BCL-2 but are negative for BCL-6; plasmocytes are monotypic for kappa or lambda.

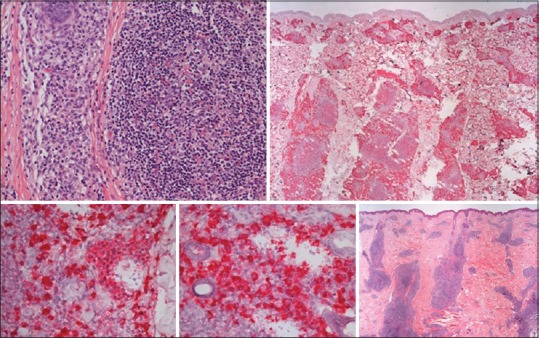

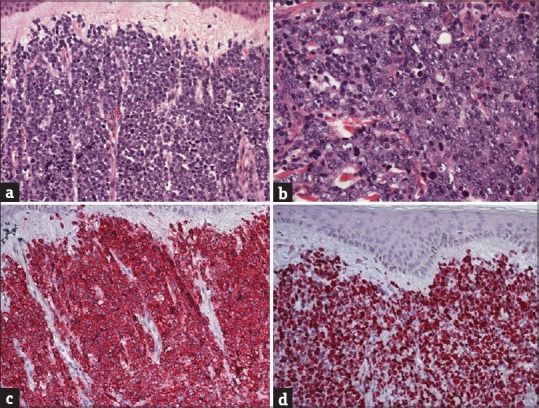

Figure 2.

Histological aspect of primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, “class-switched.” (a) Dense nodular periadnexial and perivascular infiltrate throughout dermis ad subcutis, surrounding and partially colonizing reactive lymphoid germinal centers. (b) The infiltrate consists of small B-cells, with lymphoplasmacytoid and plasma cells appearance. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, “class-switched” tumor strongly express IgM, are CD20+ CD79+, BCL-2+, but BCL-6

Two subtypes of PCMZL have been described:[24] A more common subtype (class-switched) with perivascular and periadnexial nodular infiltrate of plasma cells expressing IgG, IgA, IgE, and many intermingled T-cells. There are reactive germinal centers which express IgD. Neoplastic cells lack CXCR3 expression. The other subtype is the nonclass-switched one, and it is characterized by larger nodular infiltrates of neoplastic B-cells expressing IGM and CXCR3, a receptor for interferon (IFN)-gamma induced chemokines (a feature shared with other MALT lymphomas) in half of the cases and lower number of reactive T-cells.

Histopathological differential diagnosis

The most difficult differential diagnosis is versus B-cell pseudolymphomas that are often a true challenge, both for the dermatologist and for pathologist. Multifocal lesions, recalcitrant and relapsing clinical course, and demonstration of predominance of K or L light chain or monoclonality (using JH and JK primers) suggest a diagnosis of PCMZL. However, cases of pseudolymphomas with multifocal presentation are described[30] and “pseudoclonality” in the presence of oligoclonal B-cell infiltrate is a common problem with clonality assessment.[31]

Other important differential diagnosis is B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) which secondarily involves skin in about 2% of cases.[32] Cutaneous involvement by CLL/SLL may resemble closely PCMZL both clinically and histologically, but tumor cells express a distinct immunophenotype (CD20+, CD79a+, CD5+, CD23+, and CD43+).[33,34]

Other differential diagnosis is cutaneous infiltration by an extramedullary plasmacytoma, especially when dense dermal infiltrate shows plasma cells with monotypic Ig light chains.[10,21]

Prognosis and prognostic factors

Prognosis of PCMZL is excellent, with an overall survival estimated up to 99% at 5 years.[9,35,36,37,38,39] Up to 50% of patients experience cutaneous relapses, locally or at a distance, but these do not impair prognosis.[40,41] Extracutaneous spread is quite rare, observable in <10% of patients, especially in the nonclass-switched subtype.[24]

Systemic spread is often preceded by large cell transformation and the demonstration of translocations t(14;18)(q32;q21) IgH/BCL-2 and t(14;18)(q32;q21) IgH/MALT1.[42] Histological transformation of low-grade B-cell lymphomas toward more aggressive forms is a well-known phenomenon and it represents an independent negative prognostic factor, leading to resistance to treatments and higher mortality rates. Blastic transformation (presence of up to 30% of large transformed cells in the infiltrate) is a rare event, especially in cutaneous MZL. Its correlation with a more aggressive behavior has been recently analyzed by Magro et al.[43]

Therapy

Due to Table 4 lack of randomized, controlled trials, treatment recommendations for PCMZL are based on small retrospective studies. Consensus recommendations have been published by the EORTC and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma (ISCL),[44] but in most cases, the best approach requires a multidisciplinary evaluation by dermatologist, medical oncologist, hematologist, and radiotherapist.

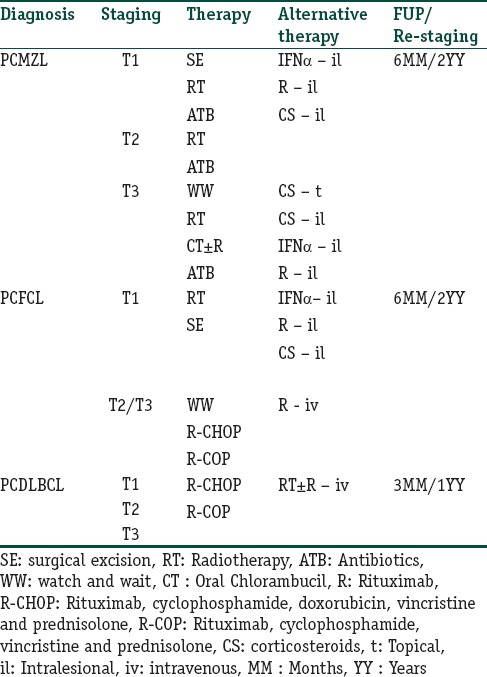

Table 4.

Treatment options and follow-up in principal primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

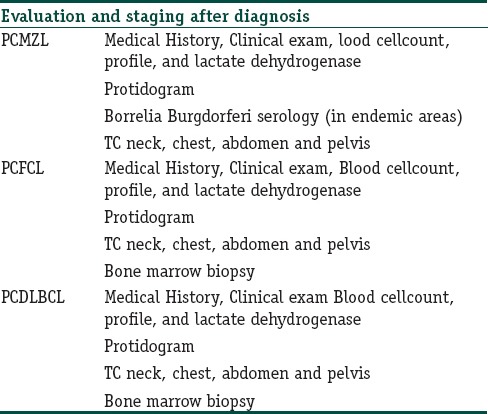

Table 3.

Evaluation and staging after the first diagnosis of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

For single small lesion/multiple localized lesions, the recommended first-line treatments are radiotherapy or surgical excision. In selected cases with positive serology for chronic Borrelia burgdorferi infection, oral antibiotics (cephalosporins or tetracyclines classes) can be tried. As second line treatment in these cases, intralesional (IL) IFN-alpha (3 mil UI three times/week), IL rituximab (CR 71%),[45] and IL corticosteroid are all viable options.

In multifocal disease, local radiotherapy, intravenous rituximab, oral antibiotics (if B. burgdorferi positive), oral chlorambucil are all well-tolerated and safe options.[46] Second-line treatments include IL IFN-alpha, IL rituximab, topical or IL steroids.

In all cases, a wait-and-see strategy, reserving active treatments only to symptomatic lesions, is a feasible option.

Primary Cutaneous Follicle Center Lymphoma

Introduction

PCFCL represents about the 11%–18%[9,47] of all cutaneous lymphomas and is the most common variant of PCBCL representing approximately the 55% of all CBCLs.[10] It is described as a separate entity in the WHO-EORTC classification of primary cutaneous lymphomas[9] as well as in the new WHO classification of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissue tumors.[10]

Clinical appearance

PCFCL usually presents as solitary or Table 2 grouped plaques, nodules, or tumors. Presentation with multifocal skin lesion is rarer and it is not associated with a more unfavorable prognosis.[9,19,48] Lesions are typically red to violet and have a smooth shiny mamillated surface.[49] The presence of erythematous papules and slightly indurated plaques surrounding tumor is a characteristic finding. In some cases, these lesions precede the development of tumor for months or even many years. The term of “reticulohistiocytoma of the dorsum” or “Crosti lymphoma” was used to describe the typical presentation of the PCFCL on back.[50]

Less typical presentation may represent a diagnostic challenge. In literature, they are described cases of PCFCL presenting as miliary papules and pustules on the face and forehead, difficult to differentiate from the most common face dermatosis (rosacea, folliculitis, acne, lupus miliaris).[51,52] Rosacea-like presentation of PCFCL may include the presence of infiltrative lesions of the nose or rhinophyma.[27,53] Scalp localization may mimic other causes of scarring alopecia by presenting as cluster of tumid annular erythematous plaques.[54] Differential diagnoses include inflammatory lesions (e.g., acne cysts and epidermal inclusion cysts), arthropod bites, other cutaneous neoplasms (basal cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia), and other non-B-cell cutaneous lymphomas (e.g., CD8 cutaneous lymphoma of the ear, CD4 pleomorphic small, medium T-cell lymphoma, or folliculotropic mycosis fungoides).[55]

Histopathology

PCFCL exhibits dermic and subcutaneous infiltrates composed of neoplastic follicle center cells that almost constantly spare the epidermis. Neoplastic follicle center cells usually are a mixture of centrocytes (small/medium and large cleaved and often multilobulated follicular center cells) and variable numbers of centroblasts (large noncleaved follicular center cells with prominent nucleoli).

Architectural pattern is variable along a continuum from follicular, nodular, diffuse growth patterns and a combination thereof. Age, growth rate, and location of biopsied lesions influenced the framework of histological presentation.[9,12,49,56] Small and early lesions contain a mixture of centrocytes, relatively few centroblasts, and many reactive T-cells. Early infiltrates may have a patchy perivascular and periadnexal growth pattern, a common diagnostic pitfall of a reactive infiltrate or “pseudolymphoma.”[57,58,59] With the progression of lesions to tumor, neoplastic B-cells increase in both number and size whereas the number of reactive T-cells steadily decreases.[9,49,60]

The typical follicular growth pattern is more frequently observed on scalp lesions than in those arising on the trunk.[56] The abnormal follicles are composed of malignant BCL-6 follicle center cells enmeshed in a network of CD21 or CD35 follicular dendritic cells. The follicles are ill-defined mantle zone that is frequently reduced or absent and lacks on tingible body macrophages.[56,61] In tumorous skin lesions, follicular structures are no longer visible, except for occasional scattered CD21 or CD35 follicular dendritic cells. Generally, a monotonous population of large centrocytes and multilobulated cells, and in rare cases, spindle-shaped cells, with a variable admixture of centroblasts and immunoblasts is present.[49,50,52,61]

The follicle center cells express a CD20+, CD79a+, BCL-6+, BCL-2− immunophenotype and a monotypic staining for surface Igs (commonly undetectable in tumorous lesions). Clonally rearranged Ig genes are usually demonstrable as the presence of somatic hypermutation of variable heavy and light chain genes.[62]

The expression of CD43 and CD10 is variable 64, 65. A positivity for the CD10 is predominantly observed in PCFCL with follicular growth pattern and uncommonly in the diffuse one.[63,64]

Immunostaining for multiple myeloma-1/IFN-regulatory factor-4 (MUM1/IRF4) and Forkhead box P1 (FOX-P1) is negative in the majority of cases,[65] and their rare positivity does not seem to influence the prognosis.[66] PCFCLs do not show the BCL-2 protein and its locus containing t(14;18) translocation, which is distinctive of systemic follicular lymphomas and a fraction of systemic DLBCL LT.[60,67,68,69]

Prognosis and predictive factors

The prognosis of PCFCLs is always excellent with a 5-year survival of >95% in large studies.[2,5,19,49,50,56,60] PCFCL is an indolent disease, even if left untreated, skin lesions may be stable, gradually increase in size over years, or regress in rare cases. Dissemination to extracutaneous sites remains an exceptional event (it occurs in 5%–10% of cases).[54]

As reported by Zinzani et al. in one of the largest series published in literature,[70] recurrence after therapy is common (up to 46.5% of cases), it is usually confined to the skin, and it does not affect prognosis. Although the higher incidence of relapse was observed in the first 4 years, a constant 2% to 6% risk of relapse was noted beyond 10 years.[70]

The growth pattern (follicular or diffuse), number of blast cells, likewise the presence of multifocal skin disease, do not seem to influence prognosis.[9,19,48] In contrast, site of presentation is suggested to influence prognosis: PCFCL presenting on the leg carries a poorer prognosis, with 5-year disease specific survival reported at 41%.[71]

There are instances of PCFCL either progressing or coexisting with DLBCL.[66] Transformation to high-grade lymphoma is an independent negative prognostic factor.

Therapy

Local radiation Table 4 therapy with a dose of at least 30 Gy and a margin of clinically uninvolved skin of at least 1–1.5 cm is the treatment of choice in patients presenting with solitary or localized skin lesions.[44]

Surgical excision is a reasonable option for small, well-demarcated, solitary lesions. No details are provided concerning excision margins.[44] Surgery appears to be an equally effective treatment option for PCBCL, while avoiding some local complications associated with radiation therapy.[72]

Patients with indolent, few scattered lesions of PCFCL may be treated by radiotherapy of all visible skin lesions. Alternatively, a wait-and-see policy associated with treatment of only symptomatic skin lesions is considered acceptable for initial management. IL treatment with IFN-alpha (all the seven cases described in literature obtained a complete response) or rituximab (10 of the 12 patients treated reached a complete response and 2 patients reached a partial response)[46] are proposable second-line choices.[44]

Topical therapies such as high-potency steroids, imiquimod, nitrogen mustard, and bexarotene and IL steroids[73] seem to have some success in selected, symptomatic patients.[44,74]

Similar approach can be adopted to treat relapses that occur in approximately 30% of patients and does not affected prognosis.[44,46]

In patients with very extensive skin lesions, particularly where local treatment is not effective or desirable, systemic rituximab (375 mg/m2 weekly for 1–8 week) can be purposed.[44]

Combination chemotherapy (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone [R-CHOP] or rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisolone) should be reserved for the exceptional cases of patients with resistant, relapsing, or progressive disseminated skin lesion or large tumors or extracutaneous disease.[44,75]

Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma, Leg Type

Introduction

PCDLBCL, LT is an aggressive type of CBCL, characterized by skin lesions mainly on the legs and a predominance of diffuse sheets of centroblasts and immunoblasts.[9]

PCDLBCL, LT was first reported as a subgroup of PCFCL in 1987 based on its particular histological feature and more aggressive behavior.[60] In 1996, Vermeer et al. proposed the term “primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma of the leg,” which was used to classify it as a distinctive subgroup in the EORTC classification.[5] In the last WHO-EORTC classification, this entity was finally defined PCDLBCL, LT to reflect the predominant but not exclusive anatomic location of the lesions. In this classification, PCDLBCL, LT was distinguished from other CBCL which may present large B-cells: PCFCL and PCDLBCL, other a group of rare large B-cell lymphomas.[9,76]

PCDLBCL, LT represents 5%–10% of all PCBCLs commonly presenting in elderly females (male:female 1:3–4), with a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life.[77]

Clinical appearance

Patients present solitary or multiple Table 2, rapidly growing, red to bluish-red firm tumors on one or both legs, usually below the knee [Figure 3a]. In 10%–15% of cases, the lesions are localized at other sites such as the trunk, head-neck, and upper arms.[Figure 3b] Multiple lesions may be disseminated or aggregated [Figure 5].[9,70,77] Extracutaneous spreading is often reported, most commonly in lymph nodes, bone marrow, and nervous system.[78]

Figure 3.

(a) Usual clinical presentation of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: Solitary plaques or nodules typically red to violet with a smooth, shiny mamillated surface. (b) The presence of erythematous slightly indurated arciform plaques surrounding tumor is a characteristic finding in primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. (c) In a small minority of patients, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma presents with multifocal skin lesions

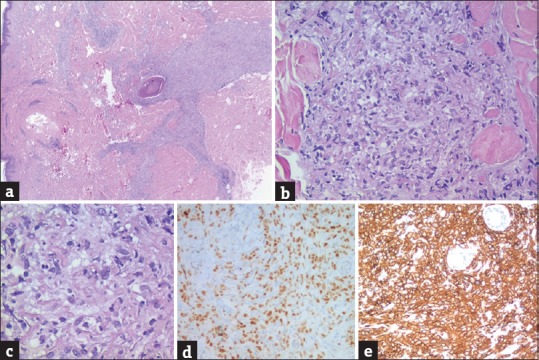

Figure 5.

Typical aspect of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type: (a) Multiple, rapidly growing, red, firm tumors on the leg. (b) Tumor lesion of facen

Histopathology

Histologically, there is a diffuse and dense infiltrate throughout the dermis that often involves the subcutis but is separated from the epidermis by a Grenz zone [Figure 6]. The infiltrate mainly consists of confluent sheets of large B-cells with roundish nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and open chromatin resembling centroblasts and immunoblasts [Figure 4].

Figure 6.

Histological aspect of primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. (a) Diffuse and dense infiltrate throughout the dermis ad subcutis separated from the epidermis by a Grenz zone. (b) The infiltrate is mainly consisting of confluent sheets of large B-cells with roundish nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and open chromatin resembling centroblasts and immunoblasts. (c and d) Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type is usually characterized by strong CD20 positivity and a high proliferation rate (Ki-67 > 70%) and BCL-6, CD5, CD10, CD30, CD138, and cyclin D1 negativity

Figure 4.

(a-c) Dermic and subcutaneous infiltrates composed of neoplastic follicle center cells that are a mixture of centrocytes and centroblasts. Neoplastic cells are BCL-6 (d) and CD20 (e) positives

The morphology of these cells is different from the cleaved and irregular nuclear morphology of the large centrocytes typically present in the infiltrate of PCFCL. Anaplastic cells are occasionally seen. Mitotic figures are frequently observed. T-cells are rare.[19,77,78,79,80]

Tumor cells express B-cell markers (CD20, CD79a, and PAX5) and possible monotypic, surface, and cytoplasmic, Ig. In particular, cytoplasmic IgM expression seems to be a sensitive marker of PCDLBCL, LT as it is negative in PCFCL.[81] BCL-2, MUM1/IRF4, and FOX-P1 are strongly expressed in PCDLBCL, LT regardless of the location of the skin lesions, but not expressed in PCFCL. This immunophenotype is useful for the diagnosis of PCDLBCL, LT even if 10% of cases are negative for BCL-2 and MUM1/IRF4.[76,78,82]

BCL-2 overexpression is associated with a chromosomal amplification of BCL-2 gene in some cases, but t(14;8) is usually not found.[83,84] PCDLBCL, LT is usually characterized by a high proliferation rate (>70%) and BCL-6, CD5, CD10, CD30, CD138, and cyclin D1 negativity[77] [Figure 6c and d].

Cytogenetic studies have revealed a frequent inactivation of p15(INK4b) and p16(INK4a) as a result of promoter hypermethylation (respectively, 11% and 44% of all PCDLBCLs)[85] and chromosomal imbalances in up to 85% of PCDLBCL, LT (mainly gains of chromosome 2q, 3, 7p, 12q, 18q and losses of 6q, 13,14,17p, 19).[9,84,86,87] Translocations of myc, BCL-6, and IgH genes have been demonstrated by fluorescence in situ hybridization in PCDLBCL, LT but not PCFCL.[88] One gene expression study has revealed an activated B-cell profile in PCDLBCL, LT.[65]

Prognosis and prognostic factor

The prognosis of PCDLBCL, LT is poor and characterized by frequent relapses and extracutaneous spreading. The 5-year survival rate is 40%–55%.[55,79,81] Higher survival rates have been reported by Zinzani et al.[70] and Kodama et al.[76] (61.7%). A location on the leg is a well-known negative prognostic factor, characterizing PCDLBCL, LT[19,79,83,106] and, in addition, a large multicenter French study found that multiple skin lesions were also negative prognostic factors.[81] The presence of round cell morphology also correlates with a short survival.[19] Other factors that have been reported to be linked to a worse prognosis are the high expression of MUM1 and FOX-P1, and, as in other aggressive lymphomas, deletion of the CDKN2A locus on chromosome 9p21.[71,76] Expression of BCL-2, associated with a reduced survival in the past, does not seem to have any prognostic role.[76,77]

Therapy

Given Table 4 the poor prognosis, old age at onset, frequent relapses, and extracutaneous spread of PCDLBCL, LT, it is often managed as a systemic lymphoma depending on its staging and location, number of skin lesions, and general status of the patient. The EORTC and ISCL consensus recommendations[44] indicate immunochemotherapy with R-CHOP with or without involved-field radiotherapy as the first-line therapy for single, localized, or generalized lesions. The use of local radiotherapy or rituximab as a single agent can be considered in particular cases. In relapsed cases, the use of protocols for relapsed systemic DLBCLs is recommended. Paulli et al.[77] have reported autologous stem cell transplant as standard of care. Oral lenalidomide monotherapy has demonstrated significant clinical activity but is still under evaluation as there are new monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors.[77,107]

Primary Cutaneous Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma, Other

Introduction

The term PCDLBCL, other, encompasses all cases of CBCL with diffuse infiltration composed of large cells not adaptable in the histopathological criteria for DLBCL, LT. It seems a very rare entity, poorly characterized that shares few cytological features with DLBCL-LT, namely, an infiltrate composed of centroblastic roundish cells and a strong BCL-2 positivity. Neoplastic cells express BCL-6 in all cases described MUM-1+ in 67% and FOX-P1 in 50%. In addition, this large cell infiltrate can be admixed with small lymphocytes. Inside the definition of PCDLBL, others are also included cases with different and even rare morphological variants such as anaplastic, plasmablastic, or T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma,[9,89] Epstein–Barr virus-positive DLBCL of the elderly, and intravascular lymphoma.[90,91]

Principal entities and their clinical and histopathological features are resumed in Tables 1–4.

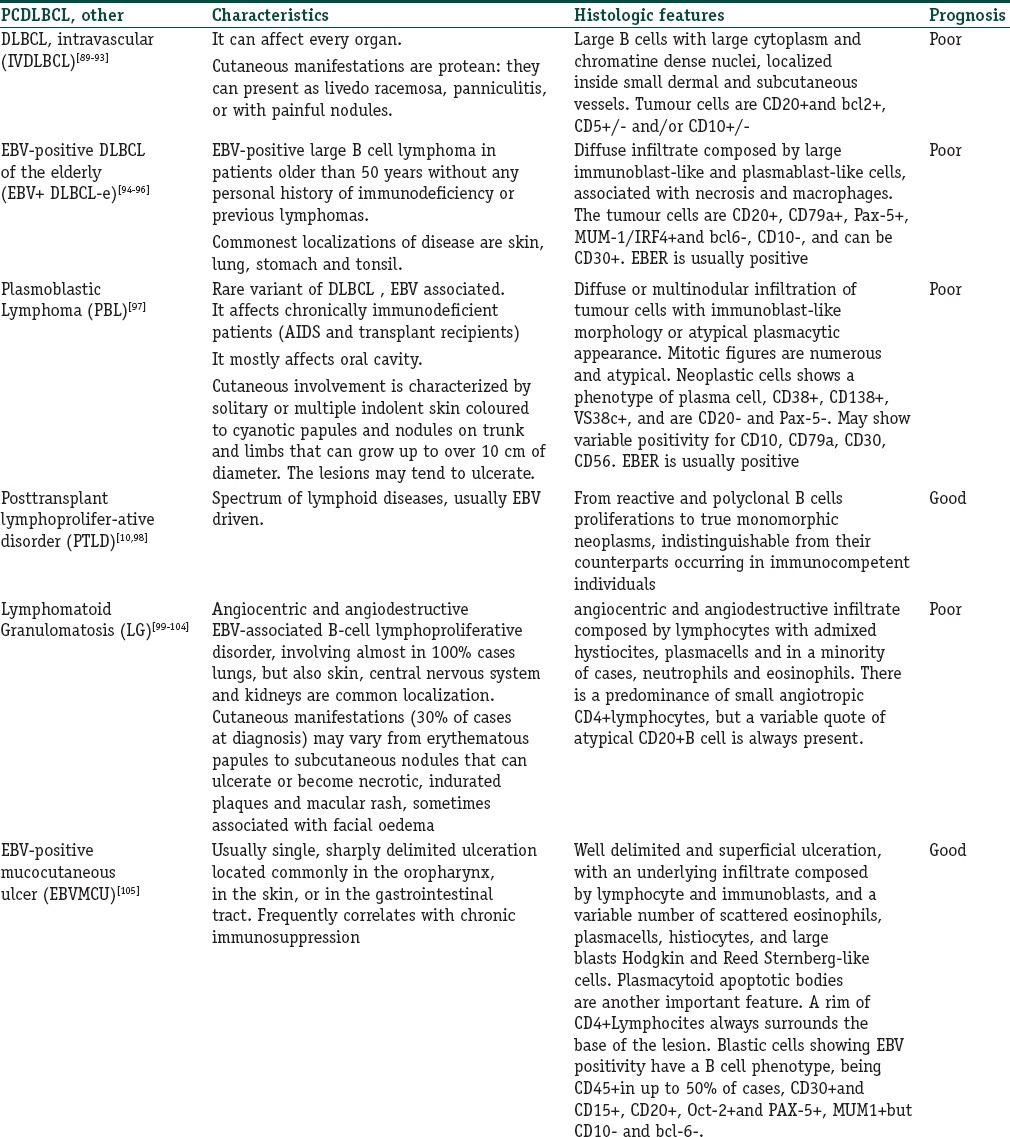

Table 1.

Principal entities classified in primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, other

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Through a review of the available literature, we have highlighted the unique clinical and histological characteristics of the main CBCL, we have underlined their prognosis and we have summarized the diagnostic approach and the therapeutic management.

References

- 1.Pimpinelli N, Masala G, Santucci M, Miligi M, Alterini R, Cardini P. Primary cutaneous lymphomas in Florence: A population-based study 1986-1995. Ann Oncol. 1996;(Suppl 3):130. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink-Puches R, Zenahlik P, Bäck B, Smolle J, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous lymphomas: Applicability of current classification schemes (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, World Health Organization) based on clinicopathologic features observed in a large group of patients. Blood. 2002;99:800–5. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JK, Cleary ML, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: A proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84:1361–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Diebold J, Muller-Hermelink HK. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111(Suppl 1):S8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vermeer MH, Geelen FA, van Heselen CW, et al. Primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas of the legs A distinct type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma with an intermediate prognosis. Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Working Group. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1304–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith BD, Wilson LD. Cutaneous lymphoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2008;32:43–87. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith BD, Glusac EJ, McNiff JM, Smith GL, Heald PW, Cooper DL, et al. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma treated with radiotherapy: A comparison of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the WHO classification systems. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:634–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris, et al. WHO Classification of Tumors of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradford PT, Devesa SS, Anderson WF, Toro JR. Cutaneous lymphoma incidence patterns in the United States: A population-based study of 3884 cases. Blood. 2009;113:5064–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zackheim HS, Vonderheid EC, Ramsay DL, LeBoit PE, Rothfleisch J, Kashani-Sabet M. Relative frequency of various forms of primary cutaneous lymphomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5 Pt 1):793–6. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.110071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstock MA, Horm JW. Mycosis fungoides in the United States. Increasing incidence and descriptive epidemiology. JAMA. 1988;260:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burg G, Braun-Falco O. Cutaneous Lymphomas, Pseudolymphomas, and Related Disorders. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1983. p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burg G, Kerl H, Przybilla B, Braun-Falco O. Some statistical data, diagnosis, and staging of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:256–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1984.tb00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burg G, Kempf W, Haeffner AC, Nestle FO, Schmid MH, Doebbeling U, et al. Cutaneous lymphomas. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1997;9:137–204. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JH, Shin HT, Lee DY, Lee JH, Yang JM, Jang KT, et al. World Health Organization-European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification of cutaneous lymphoma in Korea: A retrospective study at a single tertiary institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1200–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujita A, Hamada T, Iwatsuki K. Retrospective analysis of 133 patients with cutaneous lymphomas from a single Japanese medical center between 1995 and 2008. J Dermatol. 2011;38:524–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grange F, Bekkenk MW, Wechsler J, Meijer CJ, Cerroni L, Bernengo M, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas: A European multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3602–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith BD, Smith GL, Cooper DL, Wilson LD. The cutaneous B-cell lymphoma prognostic index: A novel prognostic index derived from a population-based registry. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3390–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kempf W, Ralfkiaer E, Duncan L, Burg G, Willemze R, Swerdlow SH, et al. Cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. In: LeBoit P, Burg G, Weedon D, editors. World Health Organization Classi-cation of Tumors. Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumors. Lyon, France: WHO IARC; 2006. pp. 194–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isaacson PG, Chott A, Nakamura S, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris NL, Swerdlow SH. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. pp. 214–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Maldegem F, van Dijk R, Wormhoudt TA, Kluin PM, Willemze R, Cerroni L, et al. The majority of cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphomas expresses class-switched immunoglobulins and develops in a T-helper type 2 inflammatory environment. Blood. 2008;112:3355–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edinger JT, Kant JA, Swerdlow SH. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphomas have distinctive features and include 2 subsets. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1830–41. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181f72835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasper RC, Wood GS, Nihal M, LeBoit PE. Anetoderma arising in cutaneous B-cell lymphoproliferative disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:124–32. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodak E, Feuerman H, Barzilai A, David M, Cerroni L, Feinmesser M. Anetodermic primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: A unique clinicopathological presentation of lymphoma possibly associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:175–82. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, David M, Feinmesser M, Halpern M, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824–31. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Servitje O, Gallardo F, Estrach T, Pujol RM, Blanco A, Fernández-Sevilla A, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: A clinical, histopathological, immunophenotypic and molecular genetic study of 22 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1147–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geyer JT, Ferry JA, Longtine JA, Flotte TJ, Harris NL, Zukerberg LR. Characteristics of cutaneous marginal zone lymphomas with marked plasmacytic differentiation and a T cell-rich background. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133:59–69. doi: 10.1309/AJCPW64FFBTTPKFN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moulonguet I, Ghnassia M, Molina T, Fraitag S. Miliarial-type perifollicular B-cell pseudolymphoma (lymphocytoma cutis): A misleading eruption in two women. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:1016–21. doi: 10.1111/cup.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Böer A, Tirumalae R, Bresch M, Falk TM. Pseudoclonality in cutaneous pseudolymphomas: A pitfall in interpretation of rearrangement studies. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:394–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swerdlow SH, Kurrer M, Bernengo M, Büchner S. Cutaneous involvement in primary extracutaneous B-cell lymphoma. In: LeBoit PE, Burg G, Weedon D, Sarasin A, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors: Pathology and Genetics: Skin Tumors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2006. pp. 204–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kash N, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Cutaneous manifestations of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection showing a marginal zone B-cell lymphoma-like infiltrate. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:712–5. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181fc576f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levin C, Mirzamani N, Zwerner J, Kim Y, Schwartz EJ, Sundram U. A comparative analysis of cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and cutaneous chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:18–23. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31821528bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang B, Tubbs RR, Finn W, Carlson A, Pettay J, Hsi ED. Clinicopathologic reassessment of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas with immunophenotypic and molecular genetic characterization. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:694–702. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeBoit PE, McNutt NS, Reed JA, Jacobson M, Weiss LM. Primary cutaneous immunocytoma. A B-cell lymphoma that can easily be mistaken for cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:969–78. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baldassano MF, Bailey EM, Ferry JA, Harris NL, Duncan LM. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia and cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma: Comparison of morphologic and immunophenotypic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:88–96. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cerroni L, Signoretti S, Höfler G, Annessi G, Pütz B, Lackinger E, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: A recently described entity of low-grade malignant cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1307–15. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199711000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hallermann C, Niermann C, Fischer RJ, Schulze HJ. Survival data for 299 patients with primary cutaneous lymphomas: A monocentre study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:521–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Golling P, Cozzio A, Dummer R, French L, Kempf W. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas-clinicopathological, prognostic and therapeutic characterisation of 54 cases according to the WHO-EORTC classification and the ISCL/EORTC TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:1094–103. doi: 10.1080/10428190802064925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoefnagel JJ, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, Heule F, van Voorst Vader PC, Sanders CJ, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: Clinical and therapeutic features in 50 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1139–45. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.9.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmedo G, Hantschke M, Rütten A, Mentzel T, Kempf W, Tomasini D, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma may exhibit both the t(14;18)(q32;q21) IGH/BCL2 and the t(14;18)(q32;q21) IGH/MALT1 translocation: An indicator for clonal transformation towards higher-grade B-cell lymphoma? Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:231–6. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31804795a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Magro CM, Yang A, Fraga G. Blastic marginal zone lymphoma: A clinical and pathological study of 8 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:319–26. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318267495f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, Bagot M, Berti E, Cerroni L, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-152850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peñate Y, Hernández-Machín B, Pérez-Méndez LI, Santiago F, Rosales B, Servitje O, et al. Intralesional rituximab in the treatment of indolent primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: An epidemiological observational multicentre study. The Spanish Working Group on Cutaneous Lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:174–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morales AV, Advani R, Horwitz SM, Riaz N, Reddy S, Hoppe RT, et al. Indolent primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: Experience using systemic rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:953–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouaziz JD, Bastuji-Garin S, Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Wechsler J, Bagot M. Relative frequency and survival of patients with primary cutaneous lymphomas: Data from a single-centre study of 203 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1206–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bekkenk MW, Vermeer MH, Geerts ML, Noordijk EM, Heule F, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Treatment of multifocal primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: A clinical follow-up study of 29 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2471–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santucci M, Pimpinelli N, Arganini L. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: A unique type of low-grade lymphoma. Clinicopathologic and immunologic study of 83 cases. Cancer. 1991;67:2311–26. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910501)67:9<2311::aid-cncr2820670918>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berti E, Alessi E, Caputo R, Gianotti R, Delia D, Vezzoni P. Reticulohistiocytoma of the dorsum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(2 Pt 1):259–72. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soon CW, Pincus LB, Ai WZ, McCalmont TH. Acneiform presentation of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:887–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Laimer M, Rütten A, Vale E, Cerroni L. Miliary and agminated-type primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma: Report of 18 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:749–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seward JL, Malone JC, Callen JP. Rhinophymalike swelling in an 86-year-old woman. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma of the nose. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:751–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.6.751-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kluk J, Charles-Holmes R, Carr RA. Primary cutaneous follicle centre cell lymphoma of the scalp presenting with scarring alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:205–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suárez AL, Pulitzer M, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C, Myskowski PL. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: Part I. Clinical features, diagnosis, and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:329.e1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cerroni L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Fink-Puches R, LeBoit PE, Kerl H. Cutaneous spindle-cell B-cell lymphoma: A morphologic variant of cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:299–304. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200008000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gulia A, Saggini A, Wiesner T, Fink-Puches R, Argenyi Z, Ferrara G, et al. Clinicopathologic features of early lesions of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, diffuse type: Implications for early diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:991–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Santucci M, Pimpinelli N. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Current concepts. I. Haematologica. 2004;89:1360–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pimpinelli N, Santucci M, Carli P, Paglierani M, Bosi A, Moretti S, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular center cell lymphoma: Clinical and histological aspects. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1990;19:203–20. doi: 10.1159/000418093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willemze R, Meijer CJ, Scheffer E, Kluin PM, Van Vloten WA, Toonstra J, et al. Diffuse large cell lymphomas of follicular center cell origin presenting in the skin. A clinicopathologic and immunologic study of 16 patients. Am J Pathol. 1987;126:325–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goodlad JR, Krajewski AS, Batstone PJ, McKay P, White JM, Benton EC, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular lymphoma: A clinicopathologic and molecular study of 16 cases in support of a distinct entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:733–41. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gellrich S, Rutz S, Golembowski S, Jacobs C, von Zimmermann M, Lorenz P, et al. Primary cutaneous follicle center cell lymphomas and large B cell lymphomas of the leg descend from germinal center cells. A single cell polymerase chain reaction analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1512–20. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Leval L, Harris NL, Longtine J, Ferry JA, Duncan LM. Cutaneous b-cell lymphomas of follicular and marginal zone types: Use of Bcl-6, CD10, Bcl-2, and CD21 in differential diagnosis and classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:732–41. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim BK, Surti U, Pandya AG, Swerdlow SH. Primary and secondary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphomas: A multiparameter analysis of 25 cases including fluorescence in situ hybridization for t(14;18) translocation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:356–64. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoefnagel JJ, Dijkman R, Basso K, Jansen PM, Hallermann C, Willemze R, et al. Distinct types of primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Blood. 2005;105:3671–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swerdlow SH, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Willemze R, Kinney MC. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: Report of the 2011 Society for Hematopathology/European Association for Haematopathology workshop. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:515–35. doi: 10.1309/AJCPNLC9NC9WTQYY. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoefnagel JJ, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, Fleuren GJ, Meijer CJ, Willemze R. Bcl-2, Bcl-6 and CD10 expression in cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: Further support for a follicle centre cell origin and differential diagnostic significance. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1183–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cerroni L, Volkenandt M, Rieger E, Soyer HP, Kerl H. bcl-2 protein expression and correlation with the interchromosomal 14;18 translocation in cutaneous lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;102:231–5. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Child FJ, Russell-Jones R, Woolford AJ, Calonje E, Photiou A, Orchard G, et al. Absence of the t(14;18) chromosomal translocation in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:735–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zinzani PL, Quaglino P, Pimpinelli N, Berti E, Baliva G, Rupoli S, et al. Prognostic factors in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: The Italian Study Group for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1376–82. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Senff NJ, Zoutman WH, Vermeer MH, Assaf C, Berti E, Cerroni L, et al. Fine-mapping chromosomal loss at 9p21: Correlation with prognosis in primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1149–55. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Parbhakar S, Cin AD. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: Role of surgery. Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19:e12–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perry A, Vincent BJ, Parker SR. Intralesional corticosteroid therapy for primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:223–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Farkas A, Kemeny L, French LE, Dummer R. New and experimental skin-directed therapies for cutaneous lymphomas. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2009;22:322–34. doi: 10.1159/000241302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fierro MT, Savoia P, Quaglino P, Novelli M, Barberis M, Bernengo MG. Systemic therapy with cyclophosphamide and anti-CD20 antibody (rituximab) in relapsed primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: A report of 7 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:281–7. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kodama K, Massone C, Chott A, Metze D, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas: Clinicopathologic features, classification, and prognostic factors in a large series of patients. Blood. 2005;106:2491–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paulli M, Lucioni M, Maffi A, Croci GA, Nicola M, Berti E. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (PCDLBCL), leg-type and other: An update on morphology and treatment. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2012;147:589–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type: Diagnostic considerations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:876–81. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0195-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vermeer MH, Geelen FA, van Haselen CW, van Voorst Vader PC, Geerts ML, van Vloten WA, et al. Primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphomas of the legs. A distinct type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma with an intermediate prognosis. Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Working Group. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1304–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Senff NJ, Hoefnagel JJ, Jansen PM, Vermeer MH, van Baarlen J, Blokx WA, et al. Reclassification of 300 primary cutaneous B-Cell lymphomas according to the new WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas: Comparison with previous classifications and identification of prognostic markers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1581–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koens L, Vermeer MH, Willemze R, Jansen PM. IgM expression on paraffin sections distinguishes primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma, leg type from primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1043–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e5060a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grange F, Beylot-Barry M, Courville P, Maubec E, Bagot M, Vergier B, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type: Clinicopathologic features and prognostic analysis in 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1144–50. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.9.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Geelen FA, Vermeer MH, Meijer CJ, Van der Putte SC, Kerkhof E, Kluin PM, et al. bcl-2 protein expression in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma is site-related. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2080–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.6.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mao X, Lillington D, Child F, Russell-Jones R, Young B, Whittaker S. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: Identification of common genomic alterations in disease pathogenesis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;35:144–55. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Child FJ, Scarisbrick JJ, Calonje E, Orchard G, Russell-Jones R, Whittaker SJ. Inactivation of tumor suppressor genes p15(INK4b) and p16(INK4a) in primary cutaneous B cell lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:941–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dijkman R, Tensen CP, Jordanova ES, Knijnenburg J, Hoefnagel JJ, Mulder AA, et al. Array-based comparative genomic hybridization analysis reveals recurrent chromosomal alterations and prognostic parameters in primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:296–305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hallermann C, Kaune KM, Siebert R, Vermeer MH, Tensen CP, Willemze R, et al. Chromosomal aberration patterns differ in subtypes of primary cutaneous B cell lymphomas. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1495–502. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2003.12635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hallermann C, Kaune KM, Gesk S, Martin-Subero JI, Gunawan B, Griesinger F, et al. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of chromosomal breakpoints in the IGH, MYC, BCL6, and MALT1 gene loci in primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:213–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kempf W, Kazakov DV, Mitteldorf C. Cutaneous lymphomas: An update. Part 2: B-cell lymphomas and related conditions. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:197–208. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e318289b20e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, Willemze R, Ilariucci F, Ambrosetti A, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: Clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the 'cutaneous variant'. Br J Haematol. 2004;127:173–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ponzoni M, Arrigoni G, Gould VE, Del Curto B, Maggioni M, Scapinello A, et al. Lack of CD29 (beta1 integrin) and CD54 (ICAM-1) adhesion molecules in intravascular lymphomatosis. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:220–6. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(00)80223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Röglin J, Böer A. Skin manifestations of intravascular lymphoma mimic inflammatory diseases of the skin. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Asada N, Odawara J, Kimura S, et al. Use of random skin biopsy for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1525–7. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(11)61097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hoeller A, Tzankov A, Pileri SA, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in elderly patients is rare in Western populations. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:352–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wong HH, Wang J. Epstein-Barr virus positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:335–40. doi: 10.1080/10428190902725813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ok CY, Ye Q, Li L, et al. Age cut-off for Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma - is it necessary? Oncotarget. 2015;6:13935–13946. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morscio J, Dierickx D, Nijs J, et al. Clinicopathologic comparison of plasmablastic lymphoma in HIV-positive, immunocompetent, and posttransplant patients: single-center series of 25 cases and meta-analysis of 277 reported cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:875–86. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seçkin D, Barete S, Euvrard S, et al. Primary cutaneous posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in solid organ transplant recipients: A multicenter European case series. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2146–53. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Katzenstein AL, Doxtader E, Narendra S. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis: insights gained over 4 decades. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:e35–48. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181fd8781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Song JY, Pittaluga S, Dunleavy K, et al. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis-a single institute experience: pathologic findings and clinical correlations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:141–56. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rysgaard CD, Stone MS. Lymphomatoid granulomatosis presenting with cutaneous involvement: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:188–93. doi: 10.1111/cup.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.James WD, Odom RB, Katzenstein AL. Cutaneous manifestations of lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Report of 44 cases and a review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:196–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carlson KC, Gibson LE. Cutaneous signs of lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1693–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Beaty MW, Toro J, Sorbara L, et al. Cutaneous lymphomatoid granulomatosis: correlation of clinical and biologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1111–20. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Raffeld M, et al. EBV Positive Mucocutaneous Ulcer—A Study of 26 Cases Associated With Various Sources of Immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:405–17. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf8622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Goodlad JR, Krajewski AS, Batstone PJ, McKay P, White JM, Benton EC, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Prognostic significance of clinicopathological subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1538–45. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200312000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Savini P, Lanzi A, Foschi FG, Marano G, Stefanini GF. Lenalidomide monotherapy in relapsed primary cutaneous diffuse large B cell lymphoma-leg type. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:333–4. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1787-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]