Abstract

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of primary cutaneous lymphomas. Several clinical variants of MF have been described. Purely, hypopigmented variant of MF (HMF) is rare. Phototherapy, especially photochemotherapy (Psoralen and ultraviolet), is the most widely used method and is recommended as the first-line treatment for HMF. However, there are no standard guidelines for phototherapy as the disease is uncommon. We, hereby, report a 30-year-old woman with HMF in whom clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical remission was achieved following narrow-band ultraviolet B therapy.

Keywords: Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides, mycosis fungoides, narrow-band ultraviolet B, phototherapy

Introduction

What was known?

Phototherapy, especially Psoralen and ultraviolet, is the first-line treatment used widely for the treatment of rare hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides.

Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides (HMF) is an atypical and uncommon variant of mycosis fungoides (MF). It differs from the classic form in clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical aspects. Psoralen and ultraviolet (PUVA) is the most widely used method for its treatment and is recommended as the first-line therapeutic modality. Narrow-band ultraviolet B (NBUVB) may be tried with same level of evidence and grade of recommendation as PUVA, thereby providing an alternative, relatively safe, and effective treatment option.

Case Report

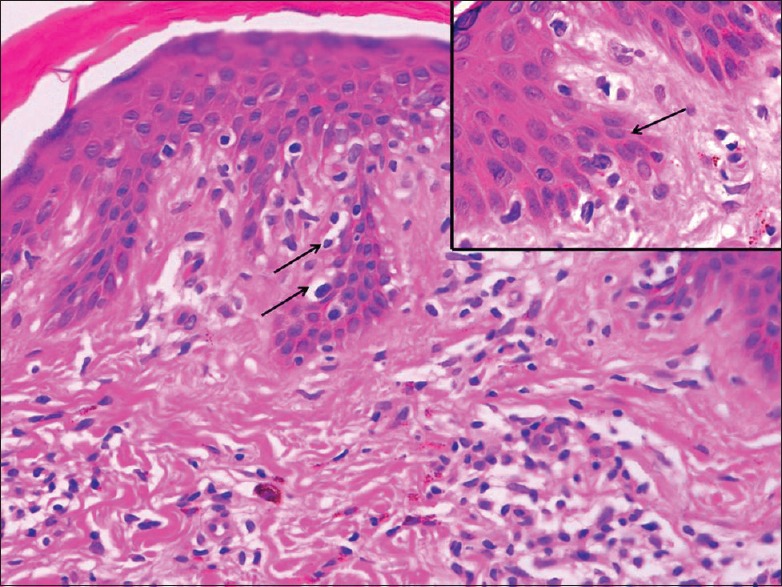

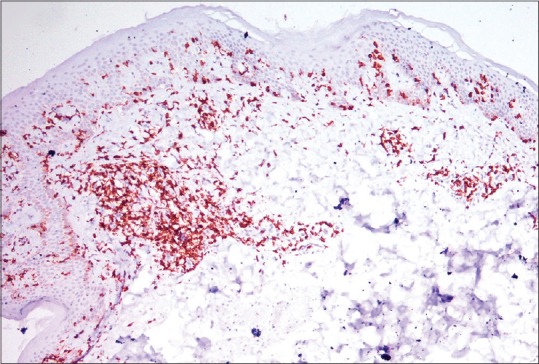

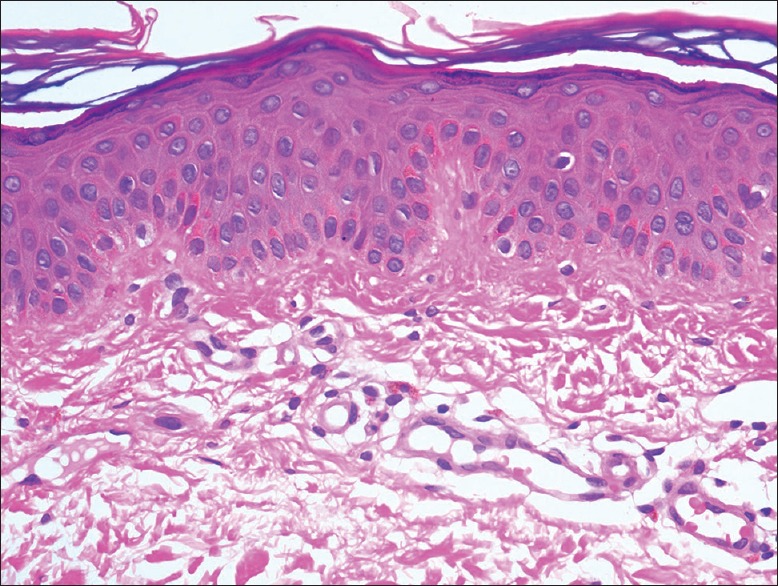

A 30-year-old woman presented to the dermatology outpatient with complaint of asymptomatic hypopigmented lesions all over the body. Initially, 2–3 lesions appeared over trunk 5 years back that gradually progressed to involve almost whole of the body sparing face and flexures. The individual lesions increased in size to coalesce. There was no remission or seasonal variation. She did not have any systemic complaints or weight loss. Her general physical examination including lymph node examination was within normal limits. Cutaneous examination revealed generalized, multiple well- to ill-defined hypopigmented, nonscaly macules without overlying atrophy or telangiectasia [Figure 1], sparing face and flexures. Mild infiltration was noted in few lesions over the back. Rest of the mucocutaneous and systemic examination was normal. Skin biopsy revealed slightly thinned out epidermis with single cell infiltration in the basal layer. The lymphoid cells appear enlarged and surrounded by clear halo with increased fibrosis in papillary dermis [Figure 2]. At higher magnification, infiltrating atypical hyperchromatic lymphoid cells were seen in the epidermis [Figure 2]. Immunohistochemistry revealed numerous T-cells arranged in bead-like fashion in the basal layer of epidermis, with focal clustering with anti-CD3-3,3'-diaminobenzidine chromogen [Figure 3]. Her routine hematological and biochemical investigations, radiograph of the chest, and USG of the abdomen revealed no abnormality. No atypical cells were seen in peripheral smear. Final diagnosis of HMF was made. The patient was extremely concerned and depressed with the diagnosis. She was counseled and started on NBUVB phototherapy, starting with 200 mJ/cm2 that was increased slowly to maximum 2100 mJ/cm2 over 3 months. NBUVB sessions were scheduled initially thrice a week for 3 months (50 sessions), followed by twice weekly for next 3 months. After 66 NBUVB sessions, the patient showed complete clearance of lesions [Figure 4]. Posttreatment biopsy showed unremarkable epidermis with lack of any atypical lymphocytes [Figure 5], and immunochemistry for CD3 did not show any evidence of epidermotropism. The patient has not shown any evidence of recurrence after 6 months of follow-up.

Figure 1.

Multiple hypopigmented nonscaly macules over buttocks and trunk

Figure 2.

Thinned out epidermis with single cell infiltration in the basal layer. The lymphoid cells appear enlarged and surrounded by clear halo (arrow). Papillary dermis shows increased fibrosis (H and E, ×100). Higher power view of epidermis in inset showing infiltrating atypical hyperchromatic lymphoid cells (H and E, ×1000)

Figure 3.

Numerous T cells arranged in bead-like fashion in basal layer of epidermis with focal clustering (anti-CD3-DAB chromogen, ×100)

Figure 4.

Complete clearance of lesions after narrow-band ultraviolet B therapy

Figure 5.

Posttreatment biopsy showing unremarkable epidermis with lack of any atypical lymphocytes (H and E, ×400)

Discussion

Primary cutaneous lymphomas (PCLs) belong to a heterogeneous group of malignant lymphoproliferative neoplasms, affecting primarily skin without any system involvement (visceral, bone marrow, or lymph nodes) at the time of diagnosis.[1] MF is the most common PCL, comprising 44%–62% of all cases. It mainly affects adults with median age at diagnosis being 55–60 years.[2] Several clinical variants of MF have been described; hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, ichthyosiform, pityriasis lichenoides-like, granulomatous, folliculotropic, pagetoid reticulosis, purpuric, hyperkeratotic, and verrucous.[2,3] Purely, HMF is rare.[1] The first case of HMF was described in 1973.[3]

HMF differs from classic MF in having a relatively younger age of onset with female predominance as was seen in our case; however, the histologic diagnosis may be delayed until 2–10 years.[1,3] HMF is reported almost exclusively in dark-skinned and Asian patients as against the classical form.[3] Clinically, HMF has asymptomatic, hypopigmented, to achromycin-scaly lesions of varying size distributed chiefly over trunk and proximal parts of extremities (buttocks, pelvic girdle, and trunk), with occasional involvement of distal extremities and head.[1,3] Differential diagnoses include hypopigmented lesion of atopic dermatitis, pityriasis alba, leprosy, vitiligo, postinflammatory hypopigmentation, sarcoidosis, pityriasis lichenoides chronica, pityriasis versicolor, and others.[3]

Histopathological features of HMF include focal parakeratosis, little or no spongiosis, upper dermal lymphocytic infiltrate with coarse collagen bundles and intense epidermotropism whereas Pautrier microabscesses are seldom noted.[3,4] Epidermotropism is predominantly by neoplastic CD4+ T-cells in classical MF and by CD8+ cells in HMF.[2,3,4,5] This immunohistochemical difference helps differentiate classical MF and HMF. This finding seems to influence the pathogenesis of HMF as the suppressor phenotype limits the disease progression by preventing cutaneous dissemination and onset of aggressive plaque stage, despite the neoplastic nature of these cells.[3] Latter coupled with early diagnosis is responsible for better prognosis of HMF as compared to the classic form.[3] Atypical neoplastic cells tend to cause melanocytes degeneration and abnormal melanogenesis resulting in hypopigmented lesions.[6]

Despite good prognosis, potential lethality of HMF should not be underestimated, and therefore, treatment is desirable. Complete clinical assessment, peripheral blood examination, quantification of Sézary cells and T-lymphocytes using flow cytometry as well imaging studies should be performed to exclude visceral involvement. Our patient did not have any evidence of systemic involvement.

Effective therapeutic modalities for HMF include phototherapy, topical nitrogen mustard, topical carmustine, and total skin electron beam therapy.[3,4,5] Phototherapy, especially photochemotherapy (PUVA), is most widely used and is recommended as the first-line treatment.[4] However, no standard guidelines for phototherapy exist. A recent review concluded that PUVA is a safe, effective, and well-tolerated therapy for early stage MF, Stage IA–IB, and Stage IIA (level of evidence 1+, grade of recommendation B).[7] Although the evidence for NBUVB is less robust (level of evidence 2++, grade of recommendation B), it has been considered at least as effective as PUVA for early-stage MF. Maintenance therapy with PUVA is to be reserved for patients who experience an early relapse.[7]

In a recent study, 7/11 patients with HMF achieved complete remission with NBUVB twice weekly (mean of 40 treatments) while remaining 4 had partial remission. Relapse was seen in three patients after a mean of 10 months.[8] In another series of nine patients, six received NBUVB and three PUVA. In 4/6 (66.7%) patients treated with NBUVB, disease recurred after a disease-free interval ranging from 2 months to 6 years.[9] Yet, another study reported phototherapy to be effective in 86.7%, with success rate of 66.7% with NBUVB and 80% with PUVA.[10] Similar observations were earlier made by Akaraphanth et al.[11]

There are no standard guidelines for phototherapy for HMF as the disease is uncommon. With wider availability of NBUVB, much better safety profile, and comparable efficacy as that of PUVA, we propose that NBUVB may be tried in more patients with HMF to arrive at a logistic conclusion. To the best of our knowledge, we report for the first time from India, clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical remission, following NBUVB therapy in HMF.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

NBUVB may be used as a relatively safe and effective therapeutic option in Indian scenario for hypopigmented variant of mycosis fungoides.

References

- 1.Naeini FF, Soghrati M, Abtahi-Naeini B, Najafian J, Rajabi P. Co-existence of various clinical and histopathological features of mycosis fungoides in a young female. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:214. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fatemi Naeini F, Abtahi-Naeini B, Sadeghiyan H, Nilforoushzadeh MA, Najafian J, Pourazizi M. Mycosis fungoides in Iranian population: An epidemiological and clinicopathological study. J Skin Cancer 2015. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/306543. 306543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furlan FC, Sanches JA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: A review of its clinical features and pathophysiology. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:954–60. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khopkar U, Doshi BR, Dongre AM, Gujral S. A study of clinicopathologic profile of 15 cases of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:167–73. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.77456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang JA, Yu JB. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in a Chinese woman. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:161. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.108093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breathnach SM, McKee PH, Smith NP. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Report of five cases with ultrastructural observations. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:643–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb11678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dogra S, Mahajan R. Phototherapy for mycosis fungoides. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81:124–35. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.152169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanokrungsee S, Rajatanavin N, Rutnin S, Vachiramon V. Efficacy of narrowband ultraviolet B twice weekly for hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Asians. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:149–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wongpraparut C, Setabutra P. Phototherapy for hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Asians. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:181–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2012.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassab-El-Naby HM, El-Khalawany MA. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Egyptian patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:397–404. doi: 10.1111/cup.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akaraphanth R, Douglass MC, Lim HW. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: Treatment and a 6(1/2)-year follow-up of 9 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:33–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]