Abstract

A 2-month-old boy was presented with widespread lateralized blue macules (nevus cesius), an extensive nevus flammeus, and large patches of cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. Moreover, he had macrocephaly, a coarse facial appearance with depressed nasal bridge, retinal abnormalities, septal defects of the heart, and obliteration of the left brachiocephalic vein and major veins of the left arm with pronounced collateralization. The multisystem disorder of this boy cannot be categorized within the present classification of distinct types of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. Although some similar complex cases have previously been reported, it seems too early to give them a specific name. Rather, the present case should be included, so far, into the group of unclassifiable types of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.

Keywords: Cardiac defects, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, lateralized blue macules, nevus cesius, nevus flammeus, phacomatosis pigmentovascularis, retinal malformation, venous abnormalities

Introduction

What was known?

The present classification of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis includes four distinct types, namely, phacomatosis cesioflammea, phacomatosis cesiomarmorata, phacomatosis spilorosea, and phacamatosis melanorosea. An additional group comprises various unclassifiable forms of extensive capillary nevi coexisting with a large pigmented nevus.

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) is an umbrella term including several different skin disorders being characterized by the coexistence of a large vascular nevus and an extensive pigmentary nevus. All of these types reflect postzygotic mosaicism and occur sporadically. In the past, they were taken as possible examples of nonallelic twin spotting,[1] but this hypothesis has recently been withdrawn by Happle[2] because both nevus flammeus and Sturge–Weber syndrome were found to originate from a postzygotic heterozygous GNAQ mutation,[3] thus excluding loss of heterozygosity as a mechanism explaining phacomatosis cesioflammea. Recently, phacomatosis cesioflammea was found to be caused by postzygotic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ genes.[4]

Within the group of PPV, the most frequently encountered form is phacomatosis cesioflammea. Other distinct types include phacomatosis cesiomarmorata, phacomatosis spilorosea, and phacomatosis melanorosea [Table 1]. We here present a male infant with an extremely unusual combination of skin lesions in the form of nevus cesius, nevus flammeus, and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC)-like lesions. Moreover, the boy had serious venous malformations, hepatosplenomegaly, and various other extracutaneous defects. Remarkably, a similar case has recently been published in this journal,[9] which is why we wonder if such unclassifiable cases may later qualify to be taken as a distinct disorder within the group of PPV.

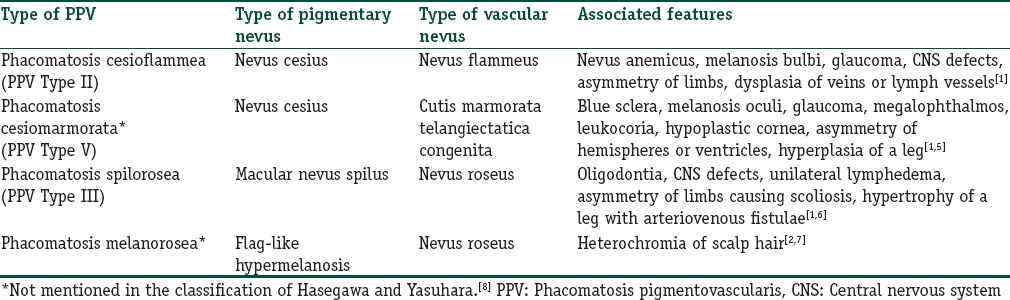

Table 1.

Present classification of distinct types of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis

Case Report

A 2-month-old boy, a product of nonconsanguineous parents, was admitted for increased head size, high-grade fever, and dark yellow discoloration of sclera and urine for the past week. There was no significant neonatal history. The mother reported a history of fever with a blistering eruption during the 2nd month of gestation. The rash had spontaneously resolved leaving hyperpigmentations that lasted for 2 months. His weight was 2.7 kg (<3rd centile). His head was large with open sutures of the anterior fontanelle. He had a coarse face with depressed nasal bridge. His skin was icteric, and the abdomen was distended. There were no petechiae or other signs of bleeding. He had a moderately enlarged palpable liver and spleen. A large bluish-gray macule covered the back, the buttocks, and the anterolateral part of the abdominal wall, compatible with a diagnosis of segmental dermal melanocytosis (nevus cesius). Moreover, an extensive nevus flammeus involved his face, neck, upper part of the chest, and the left arm [Figure 1a]. Histopathological examination of biopsies obtained from the two skin lesions showed findings compatible with segmental dermal melanocytosis and nevus flammeus. On the left side, an accessory preauricular tragus was noted [Figure 1b]. In the presternal and epigastric area, there was a thick, cord-like varicosity from which multiple thinner varicosities were radiating like roots of a tree. The legs showed marmorations as seen in cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita [Figure 1c].

Figure 1.

Widespread lateralized blue macules and nevus flammeus in a 2-month-old boy. (a) Pronounced venous collateralization due to obliteration of veins of neck and arm on the left side. (b) Nevus flammeus and preauricular tragus. (c) Lesions suggesting cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita on the right leg. The left leg was similarly affected

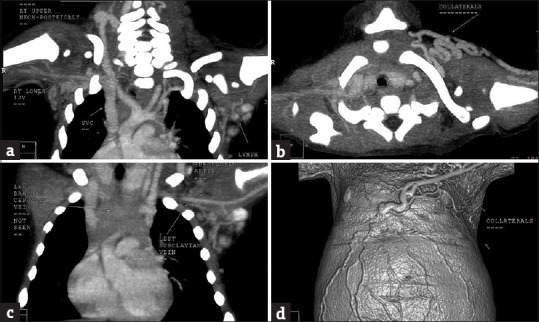

Fundus examination revealed absent macular foveal reflex, and the periphery of retina was tessellated. Hemoglobin was 6.4 g, total leukocyte count was 15,400/mm3, and platelet count was 161,000. His liver profile was abnormal with bilirubin 16.6 mg/dl, serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase 1072, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase 234, alkaline phosphatase 481, and gamma-glutamyl transferase 102. Proteins were normal. His 25-hydroxy Vitamin D level was 3 ng/ml. Venereal disease research laboratory, rapid plasma reagin, TORCH tests were negative. The urine showed precipitation. Ultrasonography of the brain did not show any calcification or hydrocephalus. No intra-abdominal abnormality was seen apart from an undescended testis in the right iliac fossa. Echocardiography showed four tiny muscular ventricular septal defects with a left-to-right shunt. X-rays of limbs and thorax showed normal mineralization of bones with normal joint spaces and alignment. Bone length was normal, and no lytic or sclerotic lesion was present. Heart and aorta appeared normal on X-rays. The left brachiocephalic vein, and the major deep veins of the left arm were obliterated [Figure 2a–c]. The venous flow from the left internal jugular vein and arm was diverted into the right brachiocephalic vein through internal mammary collateralization. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showed multiple anomalies involving the left subclavian, left brachiocephalic, and right inferior jugular veins [Figure 2d].

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows collaterals due to anomalies of the left brachiocephalic and subclavian veins and hypoplastic right internal jugular vein. (a) Venous collaterals in the right upper posterior area of the neck draining into the lower internal jugular vein that is hypoplastic. (b) The left brachiocephalic vein is not seen. (c) Venous collaterals around the left clavicle. (d) Surface collaterals as shown in a three-dimensional computed tomography image

A diagnosis of unclassifiable type of PPV (phacomatosis cesioflammea overlapping with phacomatosis cesiomarmorata) was made. The parents of the child refused permission to obtain any more tissue samples for molecular analysis.

Discussion

The rather uncommon clinical presentation of this boy fulfills the criteria of PPV, but because of overlapping features, it is difficult to categorize this multisystem disorder within the present classification of PPV. Currently, this list includes four distinct types as summarized in Table 1. We prefer this new categorization to the time-honored classification of Hasegawa and Yasuhara[8] because today, their Type I can no longer be accepted as a particular form of PPV,[1] whereas some new types have meanwhile been described [Table 1].

For heuristic purposes, our patient's disorder should be listed, for the time being, within the group of unclassifiable PPV, together with some previous reports on phacomatosis cesioflammea overlapping with CMTC-like lesions[8,10,11] and on other unusual phenotypes.[2] From a dermatological point of view, the present phenotype may represent a mixture of phacomatosis cesioflammea and phacomatosis cesiomarmorata. So far, however, it would be premature to describe such cases as a distinct entity with a specific name such as “phacomatosis cesio-flammeo-marmorata.” Future molecular research may throw more light on this issue. A limitation in the workup of the present case was the refusal of the parents to give permission to obtain additional tissue samples for molecular testing. Hence, the categorization of such unusual examples of PPV remains unsettled, so far.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Herein we describe a further example of unclassifiable phacomatosis pigmentovascularis showing features of both phacomatosis cesioflammea and phacomatosis cesiomarmorata

This seems remarkable because similar phenotypes have previously been reported. Further molecular research may show whether these peculiar examples of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis deserve to be categorized as an arbitrary coincidence, or whether they represent a distinct entity that we propose be called “phacomatosis cesio-flammeo-marmorata”.

References

- 1.Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Happle R. Mosaicism in Human Skin: Understanding Nevi, Nevoid Skin Disorders, and Cutaneous Neoplasia. Berlin: Springer; 2014. pp. 116–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, Baugher JD, Frelin LP, Cohen B, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Rivière JB, O'Shaughnessy R, Al-Olabi L, St-Onge J, et al. Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torrelo A, Zambrano A, Happle R. Large aberrant Mongolian spots coexisting with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type V or phacomatosis cesiomarmorata) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:308–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdivielso-Ramos M, Mauleón C, Hernanz JM. Phacomatosis spilorosea with oligodontia, scoliosis and fibrous cortical defects. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:260–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almeida HD, Jr, Happle R, Jr, Reginatto F, Jr, Basso F, Jr, Duquia R., Jr Phacomatosis melanorosea with heterochromia of scalp hair. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:598–9. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasegawa Y, Yasuhara M. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IVa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:651–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namiki T, Arai M, Miura K, Yokozeki H. A case of phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type II: Port-wine stain and dermal melanocytosis with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita-like lesions. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:302–3. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2016.2737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang BP, Hsu CH, Chen HC, Hsieh JW. An infant with extensive Mongolian spot, naevus flammeus and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita: A unique case of phakomatosis pigmentovascularis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:1068–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu N, Nakagawa K, Taguchi M, Okabayashi A, Kishida M, Kinoshita R, et al. Unusual case of phakomatosis pigmentovascularis in a Japanese female infant associated with three phakomatoses: Port-wine stain, dermal melanocytosis and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. J Dermatol. 2015;42:1006–7. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]