Abstract

A novel metabolomics approach for NMR‐based stable isotope tracer studies called PEPA is presented, and its performance validated using human cancer cells. PEPA detects the position of carbon label in isotopically enriched metabolites and quantifies fractional enrichment by indirect determination of 13C‐satellite peaks using 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra. In comparison with 13C‐NMR, TOCSY and HSQC, PEPA improves sensitivity, accelerates the elucidation of 13C positions in labeled metabolites and the quantification of the percentage of stable isotope enrichment. Altogether, PEPA provides a novel framework for extending the high‐throughput of 1H‐NMR metabolic profiling to stable isotope tracing in metabolomics, facilitating and complementing the information derived from 2D‐NMR experiments and expanding the range of isotopically enriched metabolites detected in cellular extracts.

Keywords: metabolism, metabolomics, NMR spectroscopy, stable isotopes

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry are the primary analytical tools used to profile metabolite levels in biological samples.1 However, the steady‐state concentration of metabolites is not sufficient to study the regulation of cellular metabolism. Elucidating the flow of chemical moieties through the complex set of metabolic reactions that happen in the cell is essential for understanding the regulation of metabolic pathways.2 For that, stable isotope tracer studies are needed, which usually require model cell lines that are fed a stable isotopically labeled substrate. Due to the unique ability of NMR to characterize isotopomers of metabolites by detecting labeling patterns in individual atoms, 13C‐NMR in combination with selective 13C‐stable isotope tracers have traditionally been used to analyze 13C enrichment in isolated metabolites3 and biological crude mixtures,4, 5, 6 enabling models of metabolic flux to be generated.7 The advent of comprehensive metabolic profiling technologies has broadened the coverage of these studies allowing for an unbiased mapping of fluxes through multiple metabolic pathways.8 The so‐called stable isotope resolved metabolomics (SIRM)9, 10 has emerged as a powerful untargeted approach to classical 13C‐NMR‐based stable isotope tracing studies. NMR‐based SIRM primarily uses homonuclear 2D 1H‐1H TOCSY (total correlation spectroscopY) and heteronuclear 2D 1H‐13C HSQC (heteronuclear single‐quantum correlation) for analyzing isotopomers in crude cell extracts,11, 12, 13, 14 NMR‐acquisition times necessary to obtain suitable TOCSY or HSQC spectra for SIRM applications are two to three orders of magnitude higher than 1D‐1H‐NMR. Even so, sensitivity issues with respect to enriched metabolites in complex biological extracts and technical complexity in data acquisition and interpretation have limited the application of 2D‐NMR for isotope tracer studies. Thus, NMR‐based SIRM is rather often used to obtain qualitative inputs on one or few samples, whereas quantitative information on larger sample sets is obtained via complementary mass spectrometry isotopologue analysis.8, 15

To make NMR more accessible to comprehensive metabolic analyses, we have developed a new methodology called PEPA (positional enrichment by proton analysis). PEPA detects the position of carbon label in isotopically enriched metabolites and quantifies their fractional enrichment in 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra. In principle, the ability of 1D‐1H‐NMR to observe 13C‐satellite peaks makes it suitable for tracer studies.3 However, direct quantification of 13C‐satellites in 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra of cell extracts is generally only possible for a few metabolites characterized by well‐resolved resonances with recognizable 13C‐satellite peaks such as lactate and alanine.16 The vast majority of 13C‐satellites remain overlapped by the large body of redundant resonances that populate 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra of biological cell extracts. 1D 13C‐edited 1H NMR offers an alternative method for carbon tracking studies.17 However, the difficulty to filter high‐intensity 12C signals, the partial or complete resonance overlap of 13C satellites in complex biological mixtures, and the lack of databases with labeled compounds, makes the untargeted profiling of enriched metabolites very problematic. Altogether this has prevented the use of 1D‐1H‐NMR for comprehensive isotope tracer studies. PEPA circumvents this limitation by indirectly determining 13C‐satellites from the decayed central peak area observed in 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra of biological equivalent replicates of labeled experiments as compared to the spectra acquired from unlabeled controls (Scheme 1 and Figure S5 in the Supporting Information). According to PEPA, the area of 13C‐satellite peaks in 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra can be indirectly determined as detailed in Equation (1):

| (1) |

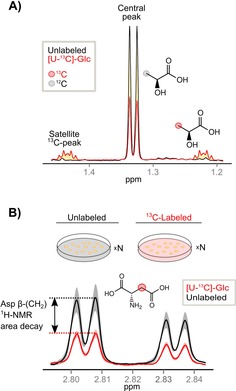

Scheme 1.

A) PEPA's conceptual framework: 1D‐1H‐NMR spectral resonance of methyl protons in lactate at δ(1.33 ppm) obtained from cell extracts of two identical U2OS osteosarcoma cell cultures grown in either unlabeled glucose (black solid line) or [U‐13C]‐glucose (Glc) (red solid line). The latter shows evenly spaced 13C‐satellite peaks located at ±1 J(C–H)/2 from the central peak. These 13C‐satellite peaks result from heteronuclear (13C–1H) scalar couplings due to the replacement of 12C‐atoms in the methyl group of lactate by 13C‐atoms from [U‐13C]‐Glc. The area of 13C‐satellite peaks (yellow‐shaded) indicates the amount of 13C‐labeled methyl group in lactate while the area of the central peak (red line) represents the amount of unlabeled methyl group left. As the labeled substrate [U‐13C]‐Glc is metabolized into lactate, the area of 13C‐satellite peaks increases proportionally with the decay of the central peak (red line). The decayed area of this central peak can be quantified from the total pool of lactate in unlabeled equivalent samples (black line). B) PEPA's workflow: metabolites are extracted from replicates (n≥3) of unlabeled and 13C‐labeled (e.g., [U‐13C]‐Glc) biologically equivalent samples and these measured by 1D‐1H‐NMR. Next, 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra are profiled and resonances quantified. Significant decayed areas of central peaks in [U‐13C]‐Glc spectra by comparison with non‐labeled controls are determined via statistical testing. As an example, aspartate β(CH2) resonance at 2.82 ppm in three replicates of unlabeled (black) and labeled (red) samples provides the mean value of the area (solid line) and standard deviations (color shaded). Significant central peak decay proves 13C‐enrichment in this position indicating metabolic transformation of glucose into aspartate in U2OS osteosarcoma cell lines.

where I represents a central peak area in each biological replicate exposed to labeled substrate, and is the mean area of the same central peak from all unlabeled replicates. The fractional 13C enrichment for each resonance in the 1D‐1H‐NMR can be calculated as detailed in Equation (2) (see also Supporting Information for a detailed discussion):

| (2) |

Consequently, by indirect determination of 13C‐satellites areas, PEPA goes beyond classical assessment of labeled metabolites by NMR and it significantly widens the coverage of the metabolic network that can be investigated using 1D‐1H‐NMR.

U2OS osteosarcoma cells were used as a cellular model for the implementation of PEPA. U2OS cells were subjected during 6 hours to culture medium containing 13C‐enriched substrates (either uniformly labeled glucose [U‐13C]‐Glc or uniformly labeled glutamine [U‐13C]‐Gln) or to culture medium with unlabeled substrates (each condition was run in triplicate, see Supporting Information for details). Overall, 84 different resonances underlying 46 polar metabolites were identified in 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra (Table S1) using BBioref AMIX database from Bruker, Chenomx, HMDB18 and complex mixture analysis by NMR (COLMAR)19 leading to the metabolic network coverage shown in Figure S4. The area of 1D‐1H‐NMR resonances in Table S1 were quantified using DOLPHIN,20 a spectral library‐guided line shape‐fitting and deconvolution algorithm specially developed for quantifying partially overlapped and poorly resolved 1D‐1H‐NMR resonances (Figure S1 and S2). Among the 84 proton resonances profiled in the 1H‐NMR spectra, we determined via statistical testing that 37 resonances showed significant decays in the central peak area in samples that were fed a stable isotopically labeled substrate (Figure S3). Figure 1 depicts fractional enrichments calculated according to Equation (2) for these 37 resonances.

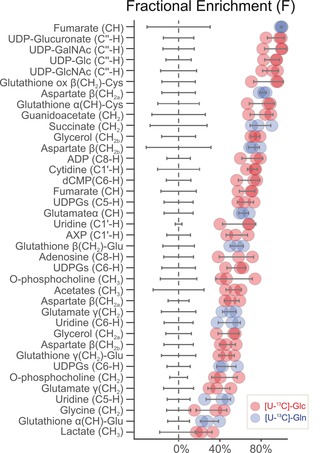

Figure 1.

PEPA predicted significant fractional enrichments (F) calculated following Equation (2). Red and blue dots represent individual F values calculated for each of the three replicate samples using [U‐13C‐Glc] or [U‐13C Gln], respectively. Gray lines indicate F standard deviation.

According to PEPA, metabolic fates of [U‐13C]‐Glc were found in the riboside C1′, glucose anomeric C1′′ and uracil ring C5 and C6 positions of UDP‐Glucose, UDP‐Glucuronate, UDP‐GlcNAc and UDP‐GalNAc. The C1′‐riboside position was also found enriched in cytidine and adenosine nucleotides (AXP, where X refers to the number of phosphate groups). AXP, in addition, showed 13C‐labeling in C2 and C8 positions of the adenine ring. Finally, the metabolic fate of labeled glucose was also found in glycine(CH2); glycerol(CH2‐OH); guanidoacetate(CH2‐OH); glutamate γ(CH2); acetates(CH3‐); aspartate β(CH2); o‐phosphocholine(‐CH2‐O/CH3‐); fumarate(CH) and glutathione γ(CH2)‐Glu/α(CH) and β(CH2)‐Cys. Thus, by using PEPA we were able to monitor the carbon fate of [U‐13C]‐Glc into the glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle, pentose phosphate pathway, glycine metabolism, hexosamine pathway and both purine and pyrimidine biosynthetic pathways (Figure S4 and S5). On the other hand, the main metabolic fates of [U‐13C]‐Gln were found in fumarate (CH) and succinate (CH2), both accounting for 99 % and 79 % fractional enrichment in mean, respectively. 13C‐atoms from [U‐13C]‐Gln were also incorporated in aspartate β(CH2) and in C5 and C6 positions of uracil in pyrimidine nucleotides, suggesting de novo synthesis of pyrimidine ring from aspartate. Finally, the fate of [U‐13C]‐Gln was detected in glutamate γ(CH2)/α(CH) and glutathione α(CH)/β(CH2), indicating activation of glutaminolysis and biosynthesis of glutathione in this cancer cell line (Figure S5).

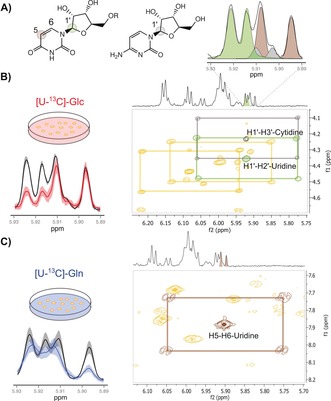

In order to confirm PEPA's results, 13C‐NMR and 2D‐edited NMR experiments (TOCSY, HSQC and HMBC) were acquired on representative sample extracts grown either in unlabeled or labeled substrates. Figure 2 shows the validation by TOCSY analysis of enrichments originally detected by 1D‐1H‐NMR and PEPA in C1′ position of uridine and cytidine, and C5 position of uridine at δ[5.89–5.93 ppm] (Figure 2 A). In [U‐13C]‐Glc experiments (Figure 2 B), the 13C‐cross‐peaks patterns around the central unlabeled peaks of H1′–H3′–cytidine (gray) and H1′–H2′–uridine (green) correlations, confirmed the predicted isotopic enrichment of such metabolites in C1′ position by PEPA. In [U‐13C]‐Gln experiments, the 13C‐cross peak pattern around the central H5–H6 correlation peak of uridine in the TOCSY spectrum (Figure 2 C) confirms the isotopic enrichment of C5 position of the uracil ring determined by PEPA. Altogether, uridine serves as a good example that dispersal of carbon flux across a range of metabolic substructures may determine the regulation of many metabolites that are assembled from these substructures.21

Figure 2.

Validation of PEPA using TOCSY (A) 1D‐1H‐NMR spectral region at δ[5.89–5.93 ppm] shows the deconvolution of overlapping proton resonances in C1′‐H position of uridine (d,J=4.4 Hz, green) and cytidine (d,J=4.1 Hz, gray), and C5‐H position of uracil in the uridine structure (d,J=8.5 Hz, brown). B) Left panel: mean area (solid line) and standard deviation (color‐shaded) of 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra acquired on unlabeled (black) and [U‐13C]‐Glc (red) cell extracts showing a significant decayed area of C1′‐H uridine and cytidine doublets. Right panel: TOCSY spectrum shows 13C cross‐peaks traced around their corresponding central unlabeled signals in green (H1′–H2′ correlation of uridine) and gray (H1′–H3′ correlation of cytidine). Additional 13C cross‐peaks for H1′–H3′ correlation of adenosine and H1′–H2′ of UDPG‐derived compounds are also indicated. C) Left panel: mean area (solid line) and standard deviation (color‐shaded) of 1D‐1H‐NMR spectra acquired on unlabeled (black) and [U‐13C]‐Gln (blue) cell extracts showing a significant decayed area for C5‐H position of uracil in the uridine structure. Right panel: TOCSY spectrum shows 13C cross‐peaks traced around the corresponding central unlabeled signal in brown (H5–H6 correlation of uridine).

Noteworthy, each of the 37 positional 13C‐enrichments observed by PEPA could only be qualitatively confirmed using a combination of 13C‐NMR and 2D‐edited NMR experiments (all spectra are available in MetaboLights with accession number MTBLS247; Table S2 shows the structural assignments). Many of the positional enrichments in Figure 1 were confirmed using 13C‐NMR. The analysis of splitting patterns (i.e., multiplicities in 13C‐NMR and 13C‐cross‐peaks in TOCSY spectra) is useful to highlight some constraints of PEPA. As with TOCSY and HSQC, PEPA cannot estimate enrichment at non‐protiated sites. The composition of positional isotopomers can neither be elucidated using PEPA. For instance, the analysis of 13C‐NMR splitting patterns of aspartate‐β(CH2) and glutamate(γCH2/βCH2) from cells cultured in [U‐13C]‐Glc revealed various 13C‐positional isotopomers. This information enables elucidating the number of turns of the TCA cycle. It is nonetheless also true that PEPA detected significant 13C‐enrichments in metabolites with either symmetric or non‐correlated protons, including fumarate, succinate, guanidoacetate and acetates, an information that cannot be otherwise detected using TOCSY experiments. The carbon labels of these metabolites were confirmed using HSQC spectra acquired on labeled sample extracts and contrasting them with HSQC spectra from unlabeled equivalent replicates. Occasionally, despite decays of central peaks, the statistical test used to determine differences between labeled and unlabeled equivalent samples do not always reach the conventional significance threshold value. This is the case of lactate and alanine. The former showed consistent central peak decays of C3 (−1.32 fold‐change at δ1.33 ppm) and C2 (−1.20 fold‐change at δ4,11 ppm). The latter showed C3 central peak decay (−1.27 fold‐change at δ1.46 ppm). This is due to the variability within and between labelled and unlabeled samples, which we mainly attribute to metabolite extraction methods and natural biological variability of cell culture replicates, in that order.22

In summary, PEPA takes advantage of the sensitivity, robustness, quantitativeness, high‐throughput capabilities and ease‐to‐implement of 1D‐1H‐NMR to study the position of carbon labels in large sample sets. Here we proved that PEPA can span the range of isotopically enriched metabolites detected in cellular extracts over 13C‐NMR and 2D‐edited experiments. PEPA greatly simplifies NMR untargeted carbon fate tracking and complements the information derived from 2D‐NMR and 13C‐NMR. Further experiments by 2D NMR and 13C‐NMR on the compounds initially screened by PEPA may enable a more comprehensive isotopomer and isotopologue characterization, including non‐protiated sites. Altogether, PEPA will accelerate the implementation of NMR in cell metabolism studies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Joan Guinovart for helpful suggestions and Dr. Maria J. Macias, Dr. Pau Martín, Dr. Gary J. Patti, Dr. Reza Zalek and Dr. Xavier Correig for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank for the financial support from the Spanish Biomedical Research Centre in Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Disorders (CIBERDEM), and the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (MINECO) grants to O.Y. (SAF2011‐30578 and BFU2014‐57466) and T.S. (BFU2012‐39521 and BFU2015‐68354). S.A. was supported by a Finnish Cultural Society Fellowship. IRB Barcelona gratefully acknowledges institutional funding from the MINECO through the Centres of Excellence Severo Ochoa award and from the CERCA Programme of the Catalan Government.

M. Vinaixa, M. A. Rodríguez, S. Aivio, J. Capellades, J. Gómez, N. Canyellas, T. H. Stracker, O. Yanes, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3531.

Contributor Information

Dr. Maria Vinaixa, Email: maria.vinaixa@urv.cat.

Dr. Oscar Yanes, Email: oscar.yanes@urv.cat.

References

- 1. Patti G. J., Yanes O., Siuzdak G., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zamboni N., Saghatelian A., Patti G. J., Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stothers J. B., Carbon-13 NMR Spectroscopy, Academic Press, New York, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 4. DeBerardinis R. J., Mancuso A., Daikhin E., Nissim I., Yudkoff M., Wehrli S., Thompson C. B., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19345–19350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen S. M., Glynn P., Shulman R. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 60–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen S. M., Ogawa S., Shulman R. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 1603–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zamboni N., Fendt S.-M., Rühl M., Sauer U., Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 878–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu W., Le A., Hancock C., Lane A. N., Dang C. V., Fan T. W.-M., Phang J. M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8983–8988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fan T. W.-M., Lane A. N., Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2008, 52, 69–117. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fan T. W.-M., Lane A. N., J. Biomol. NMR 2011, 49, 267–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lane A. N., Fan T. W.-M., Metabolomics 2007, 3, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reed M. A. C., Ludwig C., Bunce C. M., Khanim F. L., Günther U. L., Cancer Metab. 2016, 4, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carrigan J. B., Reed M. A. C., Ludwig C., Khanim F. L., Bunce C. M., Günther U. L., ChemPlusChem 2016, 81, 453–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hollinshead K. E. R., Williams D. S., Tennant D. A., Ludwig C., Probing Cancer Cell Metabolism Using NMR Spectroscopy, Springer International Publishing, 2016, pp. 89–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Le A., Lane A. N., Hamaker M., Bose S., Gouw A., Barbi J., Tsukamoto T., Rojas C. J., Slusher B. S., Zhang H., et al., Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 110–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lloyd S. G., Zeng H., Wang P., Chatham J. C., Magn. Reson. Med. 2004, 51, 1279–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Graaf R. A., Chowdhury G. M. I., Behar K. L., Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 5032–5038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wishart D. S., Jewison T., Guo A. C., Wilson M., Knox C., Liu Y., Djoumbou Y., Mandal R., Aziat F., Dong E., et al., Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D801–D807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bingol K., Li D.-W., Bruschweiler-Li L., Cabrera O. A., Megraw T., Zhang F., Brüschweiler R., ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 452–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gómez J., Brezmes J., Mallol R., Rodríguez M. A., Vinaixa M., Salek R. M., Correig X., Cañellas N., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 7967–7976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moseley H. N. B., Lane A. N., Belshoff A. C., Higashi R. M., Fan T. W. M., BMC Biol. 2011, 9, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beltran A., Suarez M., Rodríguez M. A., Vinaixa M., Samino S., Arola L., Correig X., Yanes O., Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 5838–5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary