Abstract

Objectives

To explore the experiences of caregivers of terminally ill patients with delirium, to determine the potential role of caregivers in the management of delirium at the end of life, to identify the support required to improve caregiver experience and to help the caregiver support the patient.

Methods

Four electronic databases were searched—PsychInfo, Medline, Cinahl and Scopus from January 2000 to July 2015 using the terms ‘delirium’, ‘terminal restlessness’ or ‘agitated restlessness’ combined with ‘carer’ or ‘caregiver’ or ‘family’ or ‘families’. Thirty‐three papers met the inclusion criteria and remained in the final review.

Results

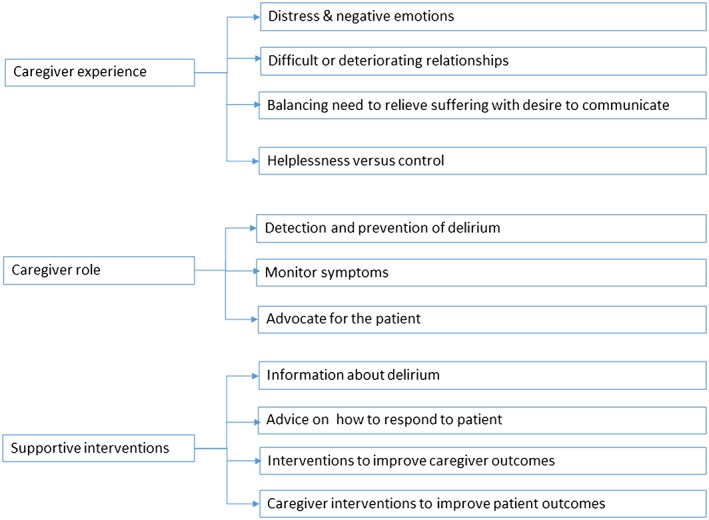

Papers focused on (i) caregiver experience—distress, deteriorating relationships, balancing the need to relieve suffering with desire to communicate and helplessness versus control; (ii) the caregiver role—detection and prevention of delirium, symptom monitoring and acting as a patient advocate; and (iii) caregiver support—information needs, advice on how to respond to the patient, interventions to improve caregiver outcomes and interventions delivered by caregivers to improve patient outcomes.

Conclusion

High levels of distress are experienced by caregivers of patients with delirium. Distress is heightened because of the potential irreversibility of delirium in palliative care settings and uncertainty around whether the caregiver–patient relationship can be re‐established before death. Caregivers can contribute to the management of patient delirium. Additional intervention studies with informational, emotional and behavioural components are required to improve support for caregivers and to help the caregiver support the patient. Reducing caregiver distress should be a goal of any future intervention.© 2016 The Authors. Psycho‐Oncology Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Keywords: cancer, oncology, delirium, hospice, palliative, caregiver

Background

Delirium is a serious and distressing neuropsychiatric syndrome frequently experienced by patients in palliative care settings. It affects up to 62% of patients during a palliative care inpatient admission and up to 88% in the days or hours preceding death 1. It is the most common and distressing neuropsychiatric complication experienced by patients with advanced cancer and is often underdiagnosed and undertreated 2. Delirium is characterized by disturbed consciousness, with reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention; altered cognition or perceptual disturbance; and an acute onset that occurs over a short period of time and fluctuates throughout the day 3.

Evidence gathered from patients who could recall experiencing delirium during a hospital admission reveals that memories of having had delirium are distressing 4, 5, 6. In particular, patients recalled experiences of reality and unreality, day–night disorientation, clouding of thought, lack of control, strong emotions and misperceptions, hallucinations and delusions. O'Malley et al. 5 identified a number of studies indicating that patients recall being aware of their inability to communicate with family caregivers and healthcare professionals, compounding their feelings of distress and humiliation. Despite this, retrospective patient reports suggest that the presence of family caregivers is beneficial, helps orientate the confused patient and protects against fear, anxiety and isolation 4, 7, 8, 9.

Complex issues arise in relation to the treatment and management of patients with delirium in palliative care settings. Reversibility of a particular delirium episode can be difficult to ascertain, and decision‐making relating to delirium management can be challenging for clinicians and caregivers acting as proxy decision‐makers 10. One study in a hospital palliative care unit estimated that approximately 50% of delirium episodes in patients receiving palliative care cannot be reversed 11. Patient and family distress because of impaired communication and decision‐making capacity in the terminal phase is common, and concerns often arise in relation to balancing the benefits of investigating the precipitating factors with treatment burden and sedation 12. In the advanced stages of illness, goals of care should be clarified with the patient, or primary caregiver if the patient is unable to participate. The greater likelihood of irreversible or terminal delirium and impending death distinguishes the experience of delirium in palliative care settings from other contexts.

Caregivers play a vital role in supporting the patient approaching end of life. Two domains of support for caregivers of people approaching end of life have been identified: (i) support for the caregiver themselves and (ii) support for the caregiver to support the patient 13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guidelines advocate the involvement of caregivers in the management of patients with delirium and recommend that information and support in relation to delirium should be offered to them 14.

The current review draws on qualitative, quantitative and mixed‐method studies to better understand the role and experience of caregivers of terminally ill patients with delirium and to identify helpful forms of support. Caregivers are broadly defined as family members, relatives or friends who are involved in the practical or emotional care of the patient. By integrating evidence relating to all aspects of the caregiver experience, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the evidence base to inform the development of caregiver interventions. The following questions form the basis for the review:

What are the experiences of caregivers of terminally ill patients with delirium?

What is the role of caregivers in the identification or management of delirium in terminally ill patients?

What type of support improves the experience of caregivers of terminally ill patients with delirium or helps the caregiver to support the patient?

While we are primarily concerned with delirium in palliative care settings, our literature search includes studies relating to experiences of caregivers of patients with delirium in other settings such as Medicine of the Elderly and Intensive Care. Such studies contain findings relevant to caregivers of terminally ill patients with reversible delirium and may include findings regarding caregivers of patients with an advanced illness who have not yet been formally identified as receiving or benefitting from palliative care.

Method

Design

An integrative review was undertaken. This approach is increasingly recognized as appropriate to inform evidence based practice—an important purpose of this study. An integrative review synthesizes findings from a diverse range of primary experimental and non‐experimental research methods, thus providing a breadth of perspectives and a comprehensive understanding of a healthcare issue 15. The approach reported here was modelled on key aspects of the systematic review methods advocated by the Cochrane Collaboration and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN)16, PRISMA standards for reporting systematic reviews 17 and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for the appraisal of qualitative research studies 18.

Search strategy

Four electronic databases were searched by the first author (AF)—PsychInfo, Medline, Cinahl and Scopus using the terms ‘delirium’, ‘terminal restlessness’ or ‘terminal agitation’ combined with ‘caregiver’ or ‘carer’ or ‘family’ or ‘families’. The search included literature published between January 1990 and July 2015.

Papers that met the following criteria were included: (i) written in English, (ii) full papers published in a peer reviewed journal, (iii) primary qualitative and quantitative research studies, (iv) caregivers were participants in the study or were actively involved in delivering the intervention and (v) caregiver outcomes could be distinguished from general outcomes. Papers were excluded if they did not focus, at least in part, on caregiver experience or the role of caregivers in relation to patients with delirium.

Search outcome

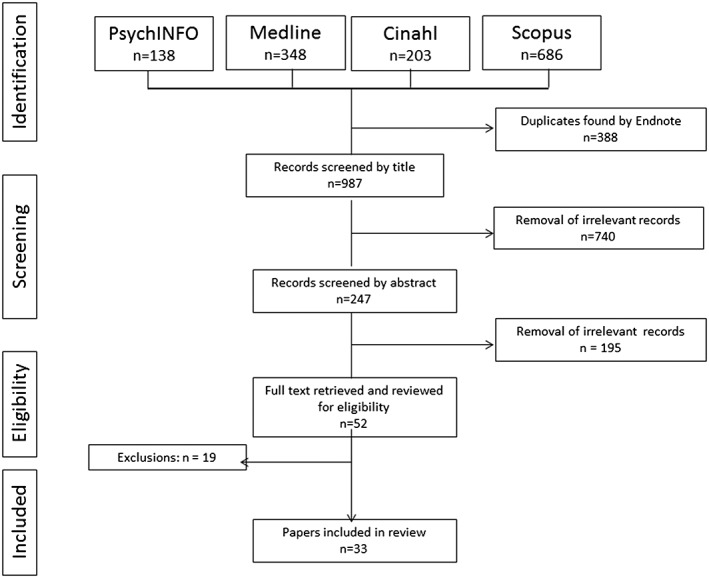

The initial search yielded 1375 records resulting in 987 distinct records once duplicates were removed. Records were first screened by AF by title, and articles with title words such as ‘delirium tremens’, ‘alcohol’, ‘suicide’ and ‘schizophrenia’ were removed. Next both titles and abstracts were read by two reviewers, AF and JL, and papers that were not relevant were removed, leaving 52 papers in total.

Each of the 52 papers were read and independently assessed by AF and JL for relevance. Nineteen papers were excluded for the following reasons: (i) literature reviews (n = 6), (ii) findings were not focused on delirium or informal caregivers (n = 5), (iii) unable to answer research question (n = 1), (iv) unable to distinguish between caregiver and patient data (n = 3), (v) study protocol only (n = 1), (vi) full text not in English (n = 1), (vii) published abstract only (n = 1) and (viii) comment/discussion paper (n = 1). Where there was any concern whether a paper should be excluded, the article was discussed with all members of the team and a decision was reached by consensus. Of the six literature review papers identified 4, 5, 19, 20, 21, 22, only two were specifically focused on caregivers 20, 21. Day and Higgins 20 conducted a narrative review of family members' experiences of older loved ones' delirium based on three papers, a PhD thesis, a book chapter and a government report, while Halloway 21 reviewed 11 papers outlining family approaches to delirium. Both these reviews were narrower in scope than the present study, and contained papers already identified. Thirty‐three papers were included in the final review (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the search strategy

Quality appraisal

We used the SIGN levels of evidence to assess the quality of the 20 papers which were predominantly quantitative and the two mixed‐method papers 16. The SIGN scoring system ranges from a 1++ score for high‐quality systematic reviews or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a low risk of bias to a score of 4 for expert opinion based evidence (refer to Table S1 in the Supporting Information). AF and JL independently graded each of the papers. In the event of a mismatch, consensus was achieved through discussion. Where uncertainty remained CK provided an opinion and a consensus was achieved.

We drew on the CASP guidelines for qualitative research to appraise the 11 papers which were predominantly qualitative 18. The CASP consists of 10 questions to guide the evaluation of research – two broad screening questions and 8 general questions. AF and JL independently assessed each qualitative paper with the CASP tool to determine whether each paper provided strong, moderate or weak evidence. In the event of a mismatch, consensus was achieved through discussion with the wider research team.

Data extraction and synthesis

All 33 papers were read by AF and JL, and data were extracted under the following headings: author(s) and publication year, country, setting, caregiver‐related aim, participants, study design and main caregiver‐related finding. A thematic analysis approach to data synthesis was adopted 23, 24. Themes from each paper relating to the research questions were identified and coded independently by AF and JL. These themes were collated in MS EXCEL and classified by AF and JL into higher order themes. The overarching themes were discussed, reviewed and agreed by all members of the research team.

Results

Characteristics of reviewed papers

Nearly half of all the papers reviewed focused on caregivers of patients receiving palliative care (n = 16). The remaining papers were concerned with caregivers of older adults (n = 9), caregivers of patients accessing oncology services but not identified as palliative (n = 2), and caregivers of patients with delirium or at risk of developing delirium in other hospital settings (n = 6). Twelve papers (36%) were specifically concerned with caregivers of patients with cancer who had experienced delirium or were at risk of experiencing delirium. Six papers focused on terminal delirium or terminal restlessness 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30.

DSM criteria were most commonly used to identify delirium (n = 11) 25, 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale was used in five papers 25, 26, 40, 41, 42, the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) was used in 10 papers 37, 38, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49 and the Confusion Rating Scale was used in two papers 44, 50. Three delirium detection studies used the Family Confusion Assessment Method (FAM‐CAM) 38, 45, 46. The Delirium Experience Questionnaire was used to explore experiences of delirium in two studies 40, 41. Terminal restlessness was assessed by an instrument developed by Jones et al. 51 in two papers 28, 29.

Quality of reviewed papers

There was only one RCT study; this was accorded a 1− grade 49 (Appendix 1). Five studies were evaluated as well conducted case control studies with a low risk of confounding bias and were given a 2+ grade 33, 44, 48, 50, 52. Eleven studies were characterized by a potentially high risk of bias and given a 2− grade 25, 26, 31, 36, 38, 40, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47. Three studies were graded as Level 3 non‐analytic studies 43, 53, 54. The quantitative part of the two mixed method studies was graded as 2− and 3 in terms of levels of evidence 47, 55.

Eleven predominantly qualitative papers were appraised following CASP guidance and classified as providing strong, moderate, adequate or weak evidence. Two qualitative papers were assessed as providing strong evidence 27, 37. Four were assessed as providing moderate to strong evidence 28, 29, 30, 32, three provided moderate levels of evidence 34, 56, 57 while the two remaining papers were assessed as providing adequate levels of evidence 35, 58.

Synthesized thematic findings

The main caregiver‐related findings identified in the 33 reviewed papers are highlighted in Table S2 in the Supporting Information. The overarching themes are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Themes identified from the literature review

Experiences of caregivers of patients with delirium

Eighteen papers included in the final review explored the experiences of caregivers of patients with delirium. Four sub‐themes were identified: (i) generalized distress and negative emotions, (ii) difficult or deteriorating relationships, (iii) balancing the need to relieve suffering with the desire to communicate and (iv) helplessness versus control

Generalized distress and negative emotions

Several papers report that moderate to severe levels of distress are experienced by the majority of caregivers of patients with delirium 25, 26, 32, 34, 40, 41. In two studies of patients with cancer, distress was found to be greater in caregivers compared with patients experiencing delirium 40, 41. Patient correlates of caregiver distress include poor physical performance status, the presence of hyperactive delirium, hallucinations, agitation, cognitive decline and incoherent speech 25, 26, 32, 34, 40. Caregivers of patients receiving palliative care were particularly worried about caring for the patients alone and were anxious about leaving the patient 25.

Anxiety is frequently reported. Buss et al. 31 found that caregivers of patients with advanced cancer who had recently seen the patient in a confused or delirious state were 12 times more likely to have generalized anxiety compared with caregivers of patients who were not thought to have delirium. Anxieties relating to the loss of the loved one before death emerged in a number of studies involving patients with advanced cancer and/or receiving palliative care 31, 37, 44, 56, 58. Day and Higgins describe the caregiver's experience of suddenly being with an unrecognizable familiar person during delirium, an ‘in‐stranger.’ This experience of being with their loved one but encountering a stranger is unsettling and distressing 37.

Specific negative emotions such as fear, embarrassment, anger, sadness and guilt are also experienced. Some caregivers experienced the patient's behaviour as unnatural and frightening 28 in particular if the patient became aggressive during the delirium episode 44, 56. Not knowing the cause of delirium was also frightening for caregivers 32. Some caregivers were embarrassed by the patient's actions during delirium, especially in the presence of others 56. Anger and disappointment were experienced by caregivers when they could no longer have a meaningful interaction with the patient 29, and caregivers felt sadness relating to the changes in the patient or the premature loss of contact before death 37, 44, 55. Guilt often occurred when caregivers felt that patients had died with unresolved issues and when caregivers felt that they had not been able to better care for the patient 25, 56.

Difficult or deteriorating relationships

Three types of relationship difficulties were identified: (i) between caregivers and staff, (ii) between caregivers and the patient and (iii) between caregivers themselves. In a qualitative study of terminal restlessness, Brajtman 30 reported disagreements and tension between staff and caregivers which stemmed from differing understandings of the patient's needs. The caregiver–patient relationship also suffers as caregivers experience the loss of a loved and familiar person before their actual death 37, 56. Caregivers of patients in palliative care settings had concerns about not having the opportunity for final goodbyes and were concerned that they had not talked about end of life issues with the patient 32, 56. Caregivers may experience difficulties with other family caregivers. Some felt isolated and unsupported by other family members, and sometimes felt that the patient acted differently with other family members, adding to the burden of caring for patient 56.

Balancing the need to relieve suffering with the desire to communicate

Caregivers of hospice patients experience tension in relation to decision‐making around sedation 29. Caregivers want the patient's suffering to end, but express regret over the patient's inability to communicate because of sedation 56. Mixed feelings in relation to what is best for the patient are experienced. In a multi‐centre questionnaire study involving 242 bereaved caregivers of patients who had experienced terminal delirium, 64% of caregivers simultaneously wanted to relieve the patient from suffering, but also wanted the patient to remain conscious 25.

Helplessness versus control

Feelings of helplessness and loss of control are common. Cohen et al. 32 found that caregivers of patients with advanced cancer in a palliative care inpatient unit felt helpless and had concerns about their own well‐being as well as about how best to help the patient. In Morita et al's 25 study of bereaved caregivers of patients with terminal delirium, 33% of caregivers reported feeling helpless in relation to how to behave around the patient and 28% reported helplessness in the context of not understanding what was happening. In that same study, up to one third of caregivers reported that they felt a burden in relation to proxy decision‐making and felt helpless. When caregivers of patients experiencing terminal restlessness have some control over treatment decision‐making, they are more accepting of future difficult decisions 30. For some caregivers, involvement in decision‐making reduces helplessness and increases acceptance and control, whereas for others it increases burden 25.

Enabling an active role for families in caring for the patients can be beneficial for both the caregiver and the patient. Toye et al. 55 found that caregivers of older adults in a hospital delirium unit welcomed any opportunity to inform personalized care of the patient and felt that they could add value to the care provided by staff. There is also evidence that an active role for caregivers has psychological benefits for patients 52.

Role of caregivers in the management of delirium

Fifteen of the 33 papers reviewed discuss the role of caregivers in the management of delirium. Three sub‐themes emerged: (i) the role of the caregivers in the prevention and detection of delirium, (ii) the caregiver's role in symptom management and (iii) the caregiver as advocate for the patient.

Prevention and detection

Eleven studies considered the potential role of caregivers in the prevention and/or detection of delirium in the cared‐for person 33, 38, 42, 43, 45, 46, 49, 50, 52, 54, 58. A number of studies have focused on the role of caregivers in early screening and detection. Kerr et al. 33 describe using family caregiver ‘expertise’ to examine precursors of delirium and found that caregivers of patients with delirium in a hospice inpatient unit (n = 20) could identify prodromal symptoms of delirium. In a separate retrospective study of 23 caregivers of patients with head and neck cancer, Bond et al. 43 found that the incidence of caregiver reported delirium was substantially higher than the rate of delirium documented by clinicians, but comparable to the rate of subsyndromal delirium, suggesting a role for caregivers in early detection. Intervention studies have reported mixed results. Gagnon et al. 50 found no effect of an intervention involving family caregivers on delirium prevention in terminal cancer, whereas Martinez et al. 49 found that a non‐pharmacological intervention delivered by families reduced delirium occurrence in hospitalized older adults compared with a control group.

There is some evidence that caregivers can administer clinical tools which could improve delirium prevention and detection. Steis et al 45 reported that the FAM‐CAM is a sensitive tool for delirium screening when used by caregivers and that caregivers report no difficulty in using it. Martins et al. 38 found evidence to support the use of the FAM‐CAM for caregiver detection of delirium, while Sands et al. 42 found that asking family members the Single Question in Delirium, ‘Do you think [name of patient] has been more confused lately?’ performs well in terms of delirium detection and demonstrates potential as a simple clinical tool worthy of further investigation. Feasibility studies provide preliminary evidence that active engagement of family caregivers of hospitalized older adults in preventive interventions is feasible and may lead to improvements in well‐being 47, 54.

Role in symptom monitoring

Six papers suggest a role for caregivers in symptom monitoring. Bruera et al. 41 retrospectively examined delirium symptom recall in patients with advanced cancer who had experienced delirium and their caregivers (n = 99 patient/caregiver dyads). High levels of agreement were evidenced between caregiver and patient‐reported delirium symptom frequency and related distress. Bruera et al. suggest that caregivers can play an important role in monitoring patient behaviour or response to treatment. Three other studies show that caregivers can potentially help monitor symptoms because of their close proximity to patients 43, 54, 58. Furthermore, there is preliminary evidence that the use of symptom assessment tools or smartphones to track delirium symptoms is feasible and acceptable to caregivers of older adults 45, 46.

Caregiver as advocate

Caregivers potentially have a role to play acting as the advocate for the patient during delirium. In a focus group study 30, palliative care health professionals (n = 12) reported that there is an onus on the caregiver to help interpret the patient's behaviour given the patient's inability to communicate and that caregivers' assessments of the patient's needs provide valuable information for the clinical team, which could be incorporated into patient treatment plans. Namba et al. 27 found that caregivers could play a role in interpreting patient talk that may appear strange to clinicians and could explain how talk about seemingly unconnected events may be linked with past real events. Having a role in caring or advocating for the patient is valued by some caregivers and staff facilitation of this is considered one aspect of emotional care 55.

Support or interventions to improve the experience of caregivers of patients with delirium or to help the caregiver support the patient

Sixteen papers identify support for caregivers of patients with delirium or support for the caregiver to help the patient. Four subthemes were identified: (i) caregivers desire for information, (ii) caregivers wish for advice on how to respond to the patient, (iii) interventions to improve caregiver experience and (iv) caregiver interventions to improve patient outcomes.

Caregivers desire for information about delirium

Five studies identify informational needs of caregivers 27, 29, 35, 55, 56. Caregivers would like clearer information about possible causes of delirium as well as what to expect in terms of progression and treatment 27, 35, 55, 56. Caregivers also desire information about how they can play a role in reducing delirium reoccurrence 55. Caregivers of patients with advanced cancer 56 report that information early on or prior to the onset of delirium would be helpful. Some caregivers would like information on how the patient is likely to be feeling during a delirium episode 55. Bereaved caregivers of patients who had experienced terminal delirium found that information about the causes, pathologies, possible treatments and expected course was helpful, as was reassurance regarding the universality of delirium 27.

Caregivers wish for advice on how to respond to the patient with delirium

Caregivers want advice on how to respond to patients with delirium 27, 55. Caregivers and healthcare professionals suggested approaches that seemed effective based on their experiences. Bereaved caregivers of patients with advanced cancer reported that talking to the delirious person, sitting quietly with them and explaining things that were happening provided a calming effect 56. A calming environment, including quiet music, soothing touch and familiar surroundings were also reported by caregivers to be effective. Toye et al. 55 found that professional care that was calm, understanding or cheerful provided emotional support, which reassured families and also provided indications to the caregiver of how to behave with the patient.

There were differing views on re‐orienting the patient. Bereaved caregivers of patients with terminal delirium felt that staff should ‘respect the patient's subjective world’ during delirium 27. Similarly, bereaved caregivers of patients in a palliative setting felt that challenging the patient about the delirium could exacerbate their condition 56. Otani et al. 36 advise caregivers of terminally ill patients with advanced cancer to converse with patients in a way that puts them at ease and to avoid ‘correcting mistakes’. In contrast, Gagnon et al. 44 advise caregivers to gently reorient the patient if they have ‘inappropriate thoughts’. Despite some consensus, clear evidence for the use of specific supportive behaviours, in particular reorienting, is lacking.

Caregiver interventions focused on improving caregiver experience

Five papers examined interventions to support caregivers. Three of these were leaflet or booklet interventions designed to improve family awareness and understanding of delirium 36, 39, 44 and two were educational interventions to improve caregiver knowledge of delirium 47, 53.

Information leaflets or booklets along with routine discussion with a clinician can improve knowledge and confidence of caregivers. In Gagnon et al.'s study 44 caregivers were given a brochure consisting of a brief definition of delirium, and information on its principle symptoms, causes and treatments. Those who received the brochure were more confident about decision‐making and were more likely to know what delirium was compared with those in the control group (35% vs. 21%). However, overall benefit of the intervention was modest, and there were no differences in caregiver mood across both groups. Adopting a similar approach, Otani et al. examined the perceived usefulness of a delirium information leaflet for 113 caregivers of patients receiving palliative care alongside the usual practice of verbal discussion 36, 39. A questionnaire sent to caregivers following bereavement found that 81% of respondents reported that the leaflet had been useful, helped them understand the dying process (84%), helped them identify what they could do for the patient (80%), helped them understand the patient's physical condition (76%) and was useful in preparing for the patient's death (72%) 36. Knowledge was significantly higher in those that had received the leaflet compared with a historical control group 39. However, as in the Gagnon et al. study, increased knowledge did not translate into emotional benefits.

Two papers reported educational interventions to increase knowledge of delirium with a view to prevention and early detection 47, 53. Keyser, Buchanan and Edge 53 ran a once‐off community educational intervention for families of older adults (n = 22). Questionnaires designed to assess knowledge of delirium showed some evidence for improvement post‐intervention; however, the study was weakened by low participation rates, low questionnaire response rates, poor participation in follow‐up interviews and a high risk of bias. Rosenbloom and Fick 47 designed the Nurse/Family Caregiver Partnership for Delirium Prevention educational programme to teach staff and families about delirium and to explore attitudes towards partnership. The results of a pre‐test and post‐test questionnaire showed improved knowledge of delirium and attitudes towards the caregiver–staff partnership, suggesting that educational interventions involving both staff and caregivers are feasible. However, the effect of these interventions on caregiver outcomes such as distress was not assessed.

Caregiver interventions focused on improving patient outcomes

Three intervention studies focused specifically on involving caregivers in interventions to improve outcomes for patients 49, 50, 52. Black et al. 52 explored the effects of nurse‐facilitated family participation in psychological care of the patient on the extent of delirium and psychological recovery following critical illness. Caregivers in the intervention group received a booklet containing information about delirium and a step‐by‐step guide to providing psychological care to the patient. The intervention did not reduce the incidence of delirium; however, patients who received the intervention demonstrated better psychological recovery and well‐being compared with those in the control group at 4, 8 and 12 weeks post‐admission, suggesting that caregiver interventions focusing on psychological care for the patient can have a beneficial impact on the patient that is sustained for some time.

Two intervention studies investigated whether involving caregivers would reduce the incidence and severity of delirium 49, 50. In Gagnon et al 50, a bedside nurse provided education to caregivers and was instructed to orient the patient as early as possible in the work shift. Adherence to the intervention was high; however, the intervention was ineffective in reducing delirium incidence or severity in patients compared with usual care. In contrast, Martinez et al. 49 examined the effectiveness of an intervention delivered by caregivers to reduce delirium occurrence in at‐risk hospitalized patients. The intervention consisted of an educational component, as well as the provision of a clock and calendar in the patient's room, avoidance of sensory deprivation, presence of familiar objects, reorientation of the patient by family members and extended visitation times. Delirium occurred in 13.3% of the control group (n = 143) compared with only 5.6% of patients in the intervention group (n = 144), suggesting a clear benefit. These studies suggest that caregiver interventions are acceptable to at least some caregivers and professionals; however, evidence remains mixed in relation to their effect on delirium occurrence.

Conclusions

This integrative review demonstrates the high level of distress and negative emotions experienced by caregivers of patients with delirium. This confirms previous evidence highlighting significant caregiver distress during patient delirium 4, 5, 20 and extends previous findings by identifying the range of negative emotions that can be experienced including sadness, guilt, shame, anger and embarrassment 25, 29, 32, 44, 55, 56. High levels of emotional distress may be linked with the breakdown in the relationship with the patient, confusion and lack of information about the causes and course of delirium, as well as helplessness in relation to how to support the patient. Reducing caregiver distress and anxiety should be an important goal of future intervention.

The findings show that delirium disrupts the relationship between the caregiver and the cared‐for person 31, 37, 56, 57. This disruption is temporary in some settings such as intensive care, but potentially permanent in palliative care settings as delirium may be irreversible. Anxiety is heightened because of uncertainty around whether the relationship between the caregiver and the patient can be re‐established before death 37, 56, 57. The need for communication with the patient increases as death approaches; caregivers want to say their final goodbye, and to understand what the patient may be trying to tell them 25, 29. Clinicians need to be sensitive to the relationship needs of caregivers and help them to relate to the patient during delirium. Clinicians can support the caregiver by providing advice on how to communicate and maintain aspects of the patient–caregiver relationship in spite of delirium that may be irreversible.

Several papers provide suggestions on the type of information that would be useful to caregivers of patients with delirium. This includes information on the causes of delirium, possible treatments, expected course and advice on how to behave around the cared‐for person 27, 29, 35, 55, 56. Intervention studies show that leaflets in conjunction with a discussion with the patient's clinician can increase caregiver knowledge around delirium 36, 39, 44 and have the potential to improve patient outcomes 49, 52. Consequently, an informational component is recommended as part of any caregiver intervention.

A few papers describe behavioural strategies that caregivers report as being effective. These include playing quiet music, soothing touch and re‐orienting the patient 55, 56. However, there is little evidence to support the effectiveness of particular strategies. Perspectives on whether it is best to re‐orient the patient vary with some studies taking the view that re‐orienting is helpful 44 and others believing that it is best to respect the patient's subjective world even in delirium 27, 36, 56. Further research on the effectiveness of different strategies that caregivers can use to support the patient during delirium is warranted.

Several papers demonstrate that caregivers can play a role in detection and prevention 33, 38, 42, 43, 46, 52, 54, 58, symptom monitoring 41, 43, 54, 58 and acting as an advocate for the patient 27, 30. Preliminary evidence suggests that such interventions are feasible and caregivers are generally positive about playing a more active role 46, 54, 55, although research on optimal levels of caregiver involvement in patient care is necessary. Given limited availability but growing demand for healthcare resources, interventions that optimize caregiver participation in patient care are vital.

There were shortcomings in the quality of many of the reviewed papers which is unsurprising given the challenging nature of research design, participant recruitment and retention in palliative care 59. Most studies, apart from those focused on delirium detection and prevention, used retrospective rather than prospective designs—caregivers were asked to report on the delirium experience some time after the event. While this is a pragmatic approach in palliative care, it heightens the risk of recall bias, in particular if the patient has subsequently died. Poor response rates to questionnaires were common causing concern that those responding may differ from the general population of caregivers being studied. Only five quantitative studies included control groups 39, 44, 49, 50, 52, and there was only one RCT 49. Outcome measures were often based on questionnaires with face validity, as opposed to psychometric testing, and some measures may have lacked the sensitivity required to detect differences in the outcome measure being assessed. Many of the qualitative studies were small scale, narrow in scope and focused on particular contexts and settings as is typical for qualitative work. However, such studies provide important insights into experiences of caregivers that inform the development of caregiver‐focused interventions.

Recommendation for a future caregiver‐focused research

The Medical Research Council identifies four key elements in the development and evaluation of complex interventions 60: (i) development of an intervention, (ii) piloting and feasibility testing, (iii) evaluation and (iv) implementation. We identified 18 papers focused on the experiences of caregivers of patients with delirium providing a strong evidence base from which new interventions can be developed. We identified a smaller number of pilot and feasibility studies and eight intervention studies. This review reveals a need for further piloting and feasibility testing of caregiver interventions, and components of interventions, as well as robust evaluation studies. Caregiver interventions in palliative care settings should include informational, emotional and behavioural elements. Given strong evidence of high levels of caregiver distress during patient delirium, reducing caregiver distress should be important outcome of any future intervention. Studies to explore the differences of the impact of delirium according to family dynamics (e.g. cohesive or conflicting) are also recommended.

Strengths and limitations of this review

A strength of this integrative review is that it includes quantitative and qualitative research as well as studies based on a range of designs. The qualitative and questionnaire studies provide important insights into caregiver's experiences and support needs, while the intervention studies provide evidence of the feasibility and the effectiveness of different approaches to improving caregiver and patient outcomes. While the focus of this review is on palliative care settings, we drew on papers outwith palliative care as many of the findings from medicine of the elderly and oncology are also relevant in palliative care. However, there are distinct differences in palliative care, most obviously the imminence of death and the possibility of terminal delirium, that are not central to non‐palliative settings. Consequently, we have drawn attention to evidence specific to terminal care at certain points throughout this paper. Finally, given the range of countries, in which these studies were conducted, findings need to be interpreted in view of the cultural context and structure of the healthcare system in each country.

Concluding comment

This integrative review highlights the high levels of distress and negative emotion experienced by caregivers of patients with delirium. In palliative care settings, distress is heightened because of uncertainty around whether the relationship between the caregiver and the patient can be re‐established before death. Significantly, we have identified the potential contributions of caregivers to managing this distressing syndrome and the potential for reciprocal benefits for patients and caregivers themselves. Caregiver interventions with informational, emotional and behavioural components are warranted to improve support for caregivers and to help support the patient. Reducing caregiver distress should be an important goal of any future intervention.

Supporting information

Table S1. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Levels of Evidence

Table S2 (online Supporting Information). Characteristics of papers included in review

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

The posts of AF and JS were funded by Marie Curie: https://www.mariecurie.org.uk.

Finucane, A. M. , Lugton, J. , Kennedy, C. , and Spiller, J. A. (2017) The experiences of caregivers of patients with delirium, and their role in its management in palliative care settings: an integrative literature review. Psycho‐Oncology, 26: 291–300. doi: 10.1002/pon.4140.

References

- 1. Hosie A, Davidson PM, Agar M, Sanderson CR, Phillips J. Delirium prevalence, incidence, and implications for screening in specialist palliative care inpatient settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2013;27(6):486–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bush SH, Bruera E. The assessment and management of delirium in cancer patients. Oncologist 2009;14(10):1039–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (5th edn.), American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Partridge JS, Martin FC, Harari D, Dhesi JK. The delirium experience: what is the effect on patients, relatives and staff and what can be done to modify this? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;28(8):804–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. O'Malley G, Leonard M, Meagher D, O'Keeffe ST. The delirium experience: a review. J Psychosom Res 2008;65(3):223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duppils GS, Wikblad K. Patients' experiences of being delirious. J Clin Nurs 2007;16(5):810–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Granberg A, Engberg IB, Lundberg D. Patients' experience of being critically ill or severely injured and cared for in an intensive care unit in relation to the ICU syndrome. Part I. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1998;14(6):294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roberts BL, Rickard CM, Rajbhandari D, Reynolds P. Factual memories of ICU: recall at two years post‐discharge and comparison with delirium status during ICU admission – a multicentre cohort study. J Clin Nurs 2007;16(9):1669–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stenwall E, Jonhagen ME, Sandberg J, Fagerberg I. The older patient's experience of encountering professional carers and close relatives during an acute confusional state: an interview study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45(11):1577–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lawlor PG, Davis DHJ, Ansari M, et al An analytical framework for delirium research in palliative care settings: integrated epidemiologic, clinician–researcher, and knowledge user perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48(2):159–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lawlor PG, Gagnon B, Mancini IL, et al Occurrence, causes, and outcome of delirium in patients with advanced cancer ‐ a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 2000;160(6):786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leonard M, Agar M, Mason C, Lawlor P. Delirium issues in palliative care settings. J Psychosom Res 2008;65(3):289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ewing G, Grande G. Development of a Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for end‐of‐life care practice at home: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2013;27(3):244–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. NICE . Delirium: diagnosis, prevention and management 2010. [updated July 2010].

- 15. Whittlemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: update methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005;52(5):546–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network . SIGN 50: A Guideline Developer's Handbook, Revised Edition. Health Improvement Scotland: Edinburgh, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Public Health Resource Unit . Critical Appraisal Skills programme 2014. Available from: http://www.casp‐uk.net/wp‐content/uploads/2011/11/casp_qualitative_appraisal_checklist_14oct10.pdf#!casp‐tools‐checklists/c18f8 [Accessed 30 July 2014].

- 19. Antai‐Otong D. Managing geriatric psychiatric emergencies: delirium and dementia. Nurs Clin North Am 2003;38(1):123–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Day J, Higgins I. Adult family member experiences during an older loved one's delirium: a narrative literature review. J Clin Nurs 2015;24(11‐12):1447–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Halloway S. A family approach to delirium: a review of the literature. Aging Ment Health 2014;18(2):129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rockwood K. Educational interventions in delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1999;10(5):426–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bettany‐Saltikov J. How to Do a Aystematic Review in Nursing: A Step‐by‐Step Guide, Open University Press: Berkshire, England, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dixon‐Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morita T, Akechi T, Ikenaga M, et al Terminal delirium: recommendations from bereaved families' experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34(6):579–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morita T, Hirai K, Sakaguchi Y, Tsuneto S, Shima Y. Family‐perceived distress from delirium‐related symptoms of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychosomatics 2004;45(2):107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Namba M, Morita T, Imura C, Kiyohara E, Ishikawa S, Hirai K. Terminal delirium: families' experience. Palliat Med 2007;21(7):587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brajtman S. Helping the family through the experience of terminal restlessness. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2005;7(2):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brajtman S. The impact on the family of terminal restlessness and its management. Palliat Med 2003;17(5):454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brajtman S. Terminal restlessness: perspectives of an interdisciplinary palliative care team. Int J Palliat Nurs 2005;11(4):170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buss MK, Vanderwerker LC, Inouye SK, Zhang B, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Associations between caregiver‐perceived delirium in patients with cancer and generalized anxiety in their caregivers. J Palliat Med 2007;10(5):1083–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cohen MZ, Pace EA, Kaur G, Bruera E. Delirium in advanced cancer leading to distress in patients and family caregivers. J Palliat Care 2009;25(3):164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kerr CW, Donnelly JP, Wright ST, et al Progression of delirium in advanced illness: a multivariate model of caregiver and clinician perspectives. J Palliat Med 2013;16(7):768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Grover S, Shah R. Delirium‐related distress in caregivers: a study from a tertiary care centre in India. Perspect Psychiatr Care 2013;49(1):21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Grover S, Shah R. Perceptions among primary caregivers about the etiology of delirium: a study from a tertiary care centre in India. Afr J Psychiatry (South Africa) 2012;15(3):193–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Otani H, Morita T, Uno S, et al Usefulness of the leaflet‐based intervention for family members of terminally ill cancer patients with delirium. J Palliat Med 2013;16(4):419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Day J, Higgins I. Existential absence: the lived experience of family members during their older loved one's delirium. Qual Health Res 2015;25(12):1700–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martins S, Conceicao F, Paiva JA, Simoes MR, Fernandes L. Delirium recognition by family: European Portuguese validation study of the family confusion assessment method. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62(9):1748–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Otani H, Morita T, Uno S, et al Effect of leaflet‐based intervention on family members of terminally ill patients with cancer having delirium: historical control study. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2014;31(3):322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A. The delirium experience: delirium recall and delirium‐related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics 2002;43(3):183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J, et al Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer 2009;115(9):2004–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sands M, Dantoc B, Hartshorn A, Ryan C, Lujic S. Single Question in Delirium (SQiD): testing its efficacy against psychiatrist interview, the Confusion Assessment Method and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. Palliat Med 2010;24(6):561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bond SM, Dietrich MS, Shuster JL Jr, Murphy BA. Delirium in patients with head and neck cancer in the outpatient treatment setting. Support Care Cancer 2012;20(5):1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gagnon P, Charbonneau C, Allard P, Soulard C, Dumont S, Fillion L. Delirium in advanced cancer: a psychoeducational intervention for family caregivers. J Palliat Care 2002;18(4):253–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Steis MR, Evans L, Hirschman KB, et al Screening for delirium using family caregivers: convergent validity of the Family Confusion Assessment Method and interviewer‐rated confusion assessment method. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(11):2121–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Steis MR, Prabhu VV, Kolanowski A, et al Detection of delirium in community‐dwelling persons with dementia. Online J Nurs Inform 2012;16(1):6–20. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rosenbloom DA, Fick DM. Nurse/family caregiver intervention for delirium increases delirium knowledge and improves attitudes toward partnership. Geriatr Nurs 2014;35(3):175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shankar KN, Hirschman KB, Hanlon AL, Naylor MD. Burden in caregivers of cognitively impaired elderly adults at time of hospitalization: a cross‐sectional analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62(2):276–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martinez FT, Tobar C, Beddings CI, Vallejo G, Fuentes P. Preventing delirium in an acute hospital using a non‐pharmacological intervention. Age Ageing 2012;41(5):629–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gagnon P, Allard P, Gagnon B, Merette C, Tardif F. Delirium prevention in terminal cancer: assessment of a multicomponent intervention. Psycho‐Oncology 2012;21(2):187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jones CL, King MB, Speck P, Kurowska A, Tookman AJ. Development of an instrument to measure terminal restlessness. Palliat Med 1998;12(2):99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Black P, Boore JR, Parahoo K. The effect of nurse‐facilitated family participation in the psychological care of the critically ill patient. J Adv Nurs 2011;67(5):1091–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Keyser SE, Buchanan D, Edge D. Providing delirium education for family caregivers of older adults. J Gerontol Nurs 2012;38(8):24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rosenbloom‐Brunton DA, Henneman EA, Inouye SK. Feasibility of family participation in a delirium prevention program for hospitalized older adults. J Gerontol Nurs 2010;36(9):22–33; quiz 4‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Toye C, Matthews A, Hill A, Maher S. Experiences, understandings and support needs of family carers of older patients with delirium: a descriptive mixed methods study in a hospital delirium unit. Int J Older People Nurs 2013;9(3):200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Greaves J, Vojkovic S, Nikoletti S, White K, Yuen K. Family caregivers' perceptions and experiences of delirium in patients with advanced cancer. Aust J Cancer Nurs 2008;9(2):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stenwall E, Sandberg J, Jonhagen ME, Fagerberg I. Relatives' experiences of encountering the older person with acute confusional state: experiencing unfamiliarity in a familiar person. Int J Older People Nurs 2008;3(4):243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Szarpa KL, Kerr CW, Wright ST, Luczkiewicz DL, Hang PC, Ball LS. The prodrome to delirium: a grounded theory study. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2013;15(6):332–337. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grande G, Todd C. Why are trials in palliative care so difficult? Palliat Med 2000;14:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Levels of Evidence

Table S2 (online Supporting Information). Characteristics of papers included in review

Supporting info item