Abstract

Background

Apremilast, an oral, small‐molecule phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, has demonstrated efficacy in patients with moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis.

Objective

Evaluate efficacy and safety of apremilast vs. placebo in biologic‐naive patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis and safety of switching from etanercept to apremilast in a phase IIIb, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study (NCT01690299).

Methods

Two hundred and fifty patients were randomized to placebo (n = 84), apremilast 30 mg BID (n = 83) or etanercept 50 mg QW (n = 83) through Week 16; thereafter, all patients continued or switched to apremilast through Week 104. The primary efficacy endpoint was achievement of PASI‐75 at Week 16 with apremilast vs. placebo. Secondary endpoints included achievement of PASI‐75 at Week 16 with etanercept vs. placebo and improvements in other clinical endpoints vs. placebo at Week 16. Outcomes were assessed through Week 52. This study was not designed for apremilast vs. etanercept comparisons.

Results

At Week 16, PASI‐75 achievement was greater with apremilast (39.8%) vs. placebo (11.9%; P < 0.0001); 48.2% of patients achieved PASI‐75 with etanercept (P < 0.0001 vs. placebo). PASI‐75 response was maintained in 47.3% (apremilast/apremilast), 49.4% (etanercept/apremilast) and 47.9% (placebo/apremilast) of patients at Week 52. Most common adverse events (≥5%) with apremilast, including nausea, diarrhoea, upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, tension headache and headache, were mild or moderate in severity; diarrhoea and nausea generally resolved in the first month. No new safety or tolerability issues were observed through Week 52 with apremilast.

Conclusion

Apremilast demonstrated significant efficacy vs. placebo at Week 16 in biologic‐naive patients with psoriasis, which was sustained over 52 weeks, and demonstrated safety consistent with the known safety profile of apremilast. Switching from etanercept to apremilast did not result in any new or clinically significant safety findings, and efficacy was maintained with apremilast through Week 52.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disease marked by overproduction of pro‐inflammatory mediators.1, 2 Early treatment with effective agents that target the pathophysiologic pathways of psoriasis and have improved safety profiles is needed for long‐term treatment of patients with chronic plaque psoriasis.3 Apremilast, an oral small‐molecule phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, works intracellularly to regulate inflammatory mediators, including pathways relevant to the pathogenesis of psoriasis.4, 5 PDE4 inhibition elevates cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, which downregulates inflammatory responses and upregulates production of anti‐inflammatory cytokines.5, 6 Apremilast has demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with active disease in the Psoriatic Arthritis Long‐term Assessment of Clinical Efficacy (PALACE) phase III clinical trial programme (PALACE 1 [NCT01172938]; PALACE 2 [NCT01212757]; PALACE 3 [NCT01212770]).7, 8, 9 The efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis who were candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy have been demonstrated in the global, phase III placebo‐controlled Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis clinical trial programme (ESTEEM 1 [NCT01194219] and ESTEEM 2 [NCT01232283]).10, 11

Here, we report the findings from a phase IIIb study (Evaluation in a Placebo‐Controlled Study of Oral Apremilast and Etanercept in Plaque Psoriasis [LIBERATE]) that evaluated apremilast vs. placebo at Week 16 in biologic‐naive patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. The study also included an active control arm that investigated the efficacy of etanercept 50 mg subcutaneous injection QW vs. placebo at Week 16 and the relative safety of switching from etanercept to apremilast at Week 16 as compared with uninterrupted apremilast through Week 52. The study was not designed or powered to make direct comparisons between apremilast and etanercept, and comparison of the efficacy and safety of the two active arms was not a pre‐specified objective of the trial. In contrast to the ESTEEM trials, the current study did not include a randomized withdrawal phase by Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) response at Week 32, allowing assessment of the efficacy of long‐term uninterrupted apremilast treatment through Week 52. Additionally, in the ESTEEM trials, up to one‐third of patients had received prior biologic therapy.10, 11

Materials and methods

LIBERATE was a global, phase IIIb, multi‐centre, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study (NCT01690299). Patients provided written informed consent. The protocol and consent were approved by institutional review boards or ethics committees for all investigational sites. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

Adult patients aged ≥18 years were eligible if they had chronic plaque psoriasis for ≥12 months (PASI score ≥12, affected body surface area [BSA] ≥10%, static Physician Global Assessment [sPGA] score ≥3 [moderate to severe]); inadequate response, intolerance or contraindication to ≥1 conventional systemic agent for treatment of psoriasis; were candidates for phototherapy or systemic (including etanercept) therapy; and had no prior exposure to a biologic therapy for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Excluded patients included those with prior failure of >3 systemic agents for treatment of psoriasis; history of known demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis or optic neuritis or history of or concurrent congestive heart failure, including medically controlled, asymptomatic congestive heart failure; other clinically significant or major uncontrolled disease; serious infection; latent, active or history of incompletely treated tuberculosis.

Permitted concomitant medications

Low‐potency topical corticosteroids as background therapy for treatment of face, axillae and groin psoriasis lesions, coal tar shampoo and/or salicylic acid scalp preparations for scalp lesions and non‐medicated emollients for body lesions were permitted except within 24 h before study visits.

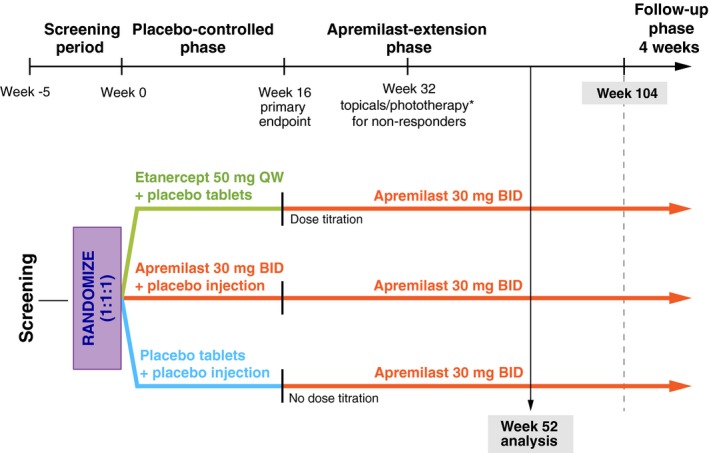

Study design

Eligible patients were randomized (1 : 1 : 1) via an interactive voice response system to placebo; apremilast oral tablet, 30 mg BID; or etanercept subcutaneous injection, 50 mg QW (placebo‐controlled phase; Fig. 1). Patients were stratified by screening body mass index (BMI; <30 and ≥30 kg/m2). Per the double‐dummy design, patients received oral tablets (apremilast 30 mg or placebo) BID and two subcutaneous injections (etanercept 25 mg each dose or saline placebo) QW. Apremilast was dose‐titrated over the first week of treatment. At Week 16, placebo and etanercept patients were switched to apremilast 30 mg BID: placebo without apremilast titration (placebo/apremilast) and etanercept with apremilast titration (etanercept/apremilast). Apremilast patients continued receiving apremilast (apremilast/apremilast). All patients maintained this dosing from Weeks 16 to 104 (apremilast‐extension phase). Blinding was maintained throughout the trial until all patients discontinued or completed the Week 104 visit. At Week 32, patients who did not achieve a ≥50% reduction from baseline in PASI score (PASI‐50) could add topical therapy including but not limited to topical corticosteroids, topical retinoids or vitamin D analogues and/or UVB phototherapy, based on investigator discretion.

Figure 1.

LIBERATE Study Design. *Starting at Week 32, all non‐responders (<PASI‐50) had the option of adding topical therapies and/or ultraviolet B phototherapy (excluding oral psoralen combined with ultraviolet A) to their treatment regimen. Two patients in each group received topical therapy and/or phototherapy. PASI‐50, 50% or greater reduction from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score.

Assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved a ≥75% reduction from baseline in PASI score (PASI‐75) at Week 16 with apremilast or placebo. A secondary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients treated with etanercept or placebo who achieved PASI‐75 at Week 16. Safety assessments included collection of adverse events (AEs), vital signs, clinical laboratory testing, physical examination, chest radiograph and 12‐lead electrocardiogram.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy assessments were conducted for the modified intent‐to‐treat (mITT) population (all randomized patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication and had both baseline PASI and ≥1 post‐treatment PASI evaluations). The safety population consisted of all patients who were randomized and received ≥1 dose of study medication. Approximately 240 patients were planned to be randomized, to yield 90% power to detect a difference of 20 percentage points between apremilast and placebo for proportions of patients achieving PASI‐75 at Week 16 (primary endpoint). The study was not powered for apremilast vs. etanercept comparisons; a post hoc comparison yielded a calculated power of 19% for detecting the observed difference. Multiplicity control of statistical testing was conducted in a hierarchical manner for secondary endpoints at Week 16 to control the overall type I error rate. Continuous endpoints were evaluated using an analysis of covariance model with treatment and baseline BMI (<30 and ≥30 kg/m2) as factors and baseline value as a covariate. Last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF) methodology was used to impute missing efficacy measurements. Multiple sensitivity analyses (including non‐responder imputation) were conducted for the primary (PASI‐75 at Week 16) and select secondary (PASI‐50 and sPGA score 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] with a ≥2‐point reduction from baseline at Week 16) endpoints. Safety data were summarized using descriptive statistics for the placebo‐controlled phase (Weeks 0 to 16) and the apremilast‐extension phase (Weeks 16 to 52).

Results

Patients

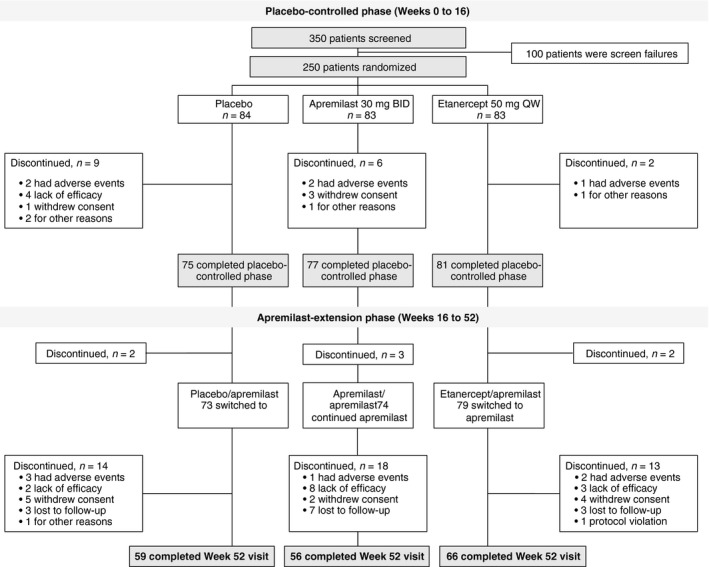

A total of 250 patients were randomized and included in the full analysis set (placebo, n = 84; apremilast, n = 83; etanercept, n = 83). Of these patients, 233 completed the placebo‐controlled phase (Weeks 0 to 16) (Fig. 2). A total of 226 patients (placebo/apremilast, n = 73; apremilast/apremilast, n = 74; etanercept/apremilast, n = 79) entered the apremilast‐extension phase (Weeks 16 to 52) and received ≥ 1 dose of study medication. Overall, 181 patients received treatment through Week 52. Demographic and baseline characteristics were generally balanced between groups (Table 1); mean psoriasis duration at baseline was 18.2 years, and mean PASI score was 19.6.

Figure 2.

Patient Disposition.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics (N = 250)

| Placebo n = 84 | Apremilast n = 83 | Etanercept n = 83 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 43.4 (14.9) | 46.0 (13.6) | 47.0 (14.1) |

| Male, n (%) | 59 (70.2) | 49 (59.0) | 49 (59.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 80 (95.2) | 79 (95.2) | 75 (90.4) |

| Asian | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Black | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.6) | 5 (6.0) |

| Other | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.4) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 29.5 (6.6) | 29.2 (5.8) | 29.9 (6.8) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 89.5 (23.1) | 88.5 (19.8) | 88.1 (20.5) |

| Duration of psoriasis, mean (SD), years | 16.6 (12.1) | 19.7 (12.7) | 18.1 (11.7) |

| PASI score (0–72), mean (SD) | 19.4 (6.8) | 19.3 (7.0) | 20.3 (7.9) |

| PASI score >20, n (%) | 32 (38.1) | 28 (33.7) | 34 (41.0) |

| Body surface area, mean (SD), % | 27.3 (16.1) | 27.1 (15.6) | 28.4 (15.7) |

| Body surface area >20%, n (%) | 42 (50.0) | 45 (54.2) | 47 (56.6) |

| sPGA of 4 (severe), n (%) | 23 (27.4) | 17 (20.5) | 13 (15.7) |

| DLQI score (0–30), mean (SD) | 11.4 (6.3) | 13.6 (6.7) | 12.5 (7.0) |

| VAS scores (0–100 mm), mean (SD), mm | |||

| Pruritus | 62.5 (22.7) | 62.6 (25.7) | 57.2 (27.7) |

| Skin discomfort/pain | 43.9 (31.2) | 51.8 (30.8) | 47.3 (32.8) |

| Patient global assessment of psoriasis disease activity | 53.6 (21.6) | 60.9 (24.6) | 55.6 (24.2) |

| Prior use of conventional systemic medications, n (%) | 70 (83.3) | 66 (79.5) | 58 (69.9) |

The n reflects the number of randomized patients; actual number of patients available for each parameter may vary. DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; sPGA, static Physician Global Assessment; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Efficacy

Weeks 0 to 16

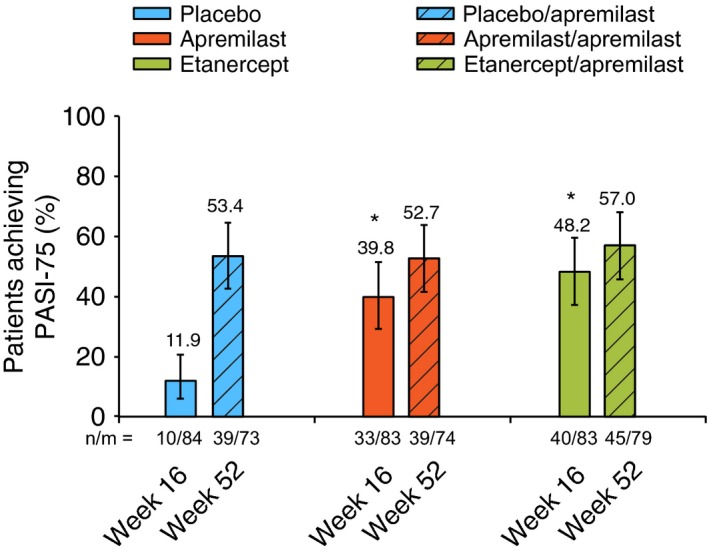

At Week 16, PASI‐75 response was achieved by significantly more patients receiving apremilast (39.8%) vs. placebo (11.9%, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3 and Table 2). At Week 16, PASI‐75 response was achieved by significantly more patients receiving etanercept (48.2%) vs. placebo (11.9%, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3 and Table 2). Results of the non‐responder imputation sensitivity analyses were similar to those of the primary analysis (Table 2).

Figure 3.

PASI‐75 Response at Week 16 (LOCF) and Week 52 (EOP). *P < 0.0001 vs. placebo. The vertical lines indicate two‐sided 95% CIs. CI, confidence interval; EOP, end of phase; LOCF, last observation carried forward; for the apremilast‐extension phase, this includes the last observation in the phase, between Week 16 and Week 52; n/m, number of responders/number of patients with sufficient data for evaluation; PASI‐75, 75% or greater reduction from baseline in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score.

Table 2.

Clinical response across efficacy endpoints at Week 16 and Week 52

| Placebo‐controlled phase: Weeks 0 to 16a | Apremilast‐extension phase: Weeks 16 to 52b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo n = 84 | Apremilast n = 83 | Etanercept n = 83 | Placebo/Apremilast n = 73 | Apremilast/Apremilast n = 74 | Etanercept/Apremilast n = 79 | |

| Primary endpoint, n (%) | ||||||

| PASI‐75 (LOCF) | 10 (11.9) |

33 (39.8) P < 0.0001 |

40 (48.2) P < 0.0001 |

39 (53.4) | 39 (52.7) | 45 (57.0) |

| P = 0.2565 APR vs. ETN (post hoc) | ||||||

| PASI‐75 (NRI) | 10 (11.9) |

30 (36.1) P = 0.0003 |

39 (47.0) P < 0.0001 |

35 (47.9) | 35 (47.3) | 39 (49.4) |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||||

| sPGA response (LOCF), n (%)c | 3 (3.6) |

18 (21.7) P = 0.0005 |

24 (28.9) P < 0.0001 |

26 (35.6) | 18 (24.3) | 21 (26.6) |

| sPGA response (NRI), n (%) | 3 (3.6) |

16 (19.3) P = 0.0015 |

24 (28.9) P < 0.0001 |

25 (34.2) | 16 (21.6) | 16 (20.3) |

| Percentage change from baseline in psoriasis affected BSA (LOCF), mean (SD) | −16.5 (36.9) |

−48.3 (35.1) P < 0.0001 |

−56.5 (31.6) P < 0.0001 |

−60.8 (37.2) | −58.6 (32.0) | −72.0 (22.8) |

| PASI‐50 (LOCF), n (%) | 28 (33.3) |

52 (62.7) P = 0.0002 |

69 (83.1) P < 0.0001 |

53 (72.6) | 52 (70.3) | 72 (91.1) |

| PASI‐50 (NRI), n (%) | 28 (33.3) |

49 (59.0) P = 0.0008 |

67 (80.7) P < 0.0001 |

48 (65.8) | 47 (63.5) | 61 (77.2) |

| Change from baseline in total DLQI score (LOCF), mean (SD) | −3.8 (5.6) |

−8.3 (7.7) P < 0.0001 |

−7.8 (6.5) P = 0.0004 |

−6.7 (6.1) | −8.2 (7.0) | −6.9 (7.3) |

| LS‐PGA response (LOCF), n (%)c | 5 (6.0) |

20 (24.1) P = 0.0011 |

19 (22.9) P = 0.0021 |

19 (26.0) | 21 (28.4) | 19 (24.1) |

| Exploratory endpoints | ||||||

| PASI‐90 (LOCF), n (%) | 3 (3.6) |

12 (14.5) P = 0.0169 |

17 (20.5) P = 0.0009 |

19 (26.0) | 13 (17.6) | 22 (27.8) |

| Percentage change from baseline in PASI score (LOCF), mean (SD) | −32.2 (33.0) |

−58.8 (28.4) P < 0.0001 |

−69.3 (23.7) P < 0.0001 |

−66.3 (32.4) | −66.2 (26.7) | −75.1 (21.0) |

| Patients with DLQI >5 at baseline | n = 84 | n = 83 | n = 83 | n = 59 | n = 66 | n = 64 |

|

Patients achieving DLQI MCID (decrease from baseline >=5 points) (LOCF), n (%) |

35 (41.7) |

54 (65.1) P = 0.0032 |

54 (65.1) P = 0.0032 |

40 (67.8) | 52 (78.8) | 43 (67.2) |

| Change from baseline in pruritus VAS score (LOCF), mean (SD), mm | −22.5 (31.8) |

−35.6 (29.0) P = 0.0026 |

−36.4 (31.6) P < 0.0001 |

−35.9 (30.0) | −31.7 (30.5) | −32.1 (33.1) |

| Change from baseline in skin discomfort/pain VAS score (LOCF), mean (SD), mm | −11.3 (30.3) |

−26.2 (34.9) P = 0.0246 |

−30.7 (30.6) P < 0.0001 |

−21.7 (29.9) | −24.9 (37.5) | −28.5 (30.9) |

| Change from baseline in patient global assessment of psoriasis disease activity VAS (LOCF), mean (SD), mm | −17.0 (25.0) |

−31.2 (32.3) P = 0.0033 |

−35.9 (28.0) P < 0.0001 |

−29.3 (30.1) | −30.7 (30.8) | −32.0 (31.3) |

| Patients with nail psoriasis at baselined | n = 42 | n = 50 | n = 50 | n = 37 | n = 48 | n = 46 |

| Percentage change from baseline in NAPSI score (LOCF), mean (SD) | −10.1 (32.6) |

−18.7 (40.2) P = 0.4959 |

−37.7 (45.9) P = 0.0024 |

−51.1 (43.5) | −44.6 (44.3) | −60.7 (39.7) |

| Patients with moderate or greater scalp psoriasis at baseline | n = 58 | n = 54 | n = 54 | n = 50 | n = 49 | n = 53 |

| ScPGA score 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) (LOCF), n (%) | 15 (25.9) |

24 (44.4) P = 0.0458 |

27 (50.0) P = 0.0083 |

26 (52.0) | 26 (53.1) | 32 (60.4) |

The n reflects the number of randomized patients; actual number of patients available for each parameter may vary.

Week 16 missing data were handled with LOCF methodology; sensitivity analyses used NRI methodology for missing values.

Data are from patients who entered and received at least one dose of study medication during the Week 16 to Week 52 apremilast‐extension phase; missing data were handled with LOCF methodology using data from the apremilast‐extension phase; sensitivity analyses used NRI methodology for missing values.

sPGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) with a ≥2‐point reduction from baseline; LS‐PGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear).

Patients with a baseline value and at least one post‐baseline value are included.

Italicized P‐values are nominal due to hierarchy of statistical testing of secondary endpoints.

APR, apremilast; BID, twice daily; BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; ETN, etanercept; LOCF, last observation carried forward; LS‐PGA, Lattice System Physician's Global Assessment; MCID, minimal clinically important difference; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; NRI, non‐responder imputation; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PASI‐50, 50% or greater reduction from baseline in PASI score; PASI‐75, 75% or greater reduction from baseline in PASI score; PASI‐90, 90% or greater reduction from baseline in PASI score; sPGA, static Physician Global Assessment (0 = clear, 1 = almost clear, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe); ScPGA, Scalp Physician Global Assessment; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Significant improvements were achieved with apremilast (vs. placebo) at Week 16 for the following secondary endpoints: sPGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear), percentage change from baseline in the psoriasis affected BSA, PASI‐50 response, change from baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) total score and Lattice System Physician's Global Assessment (LS‐PGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) (Table 2).

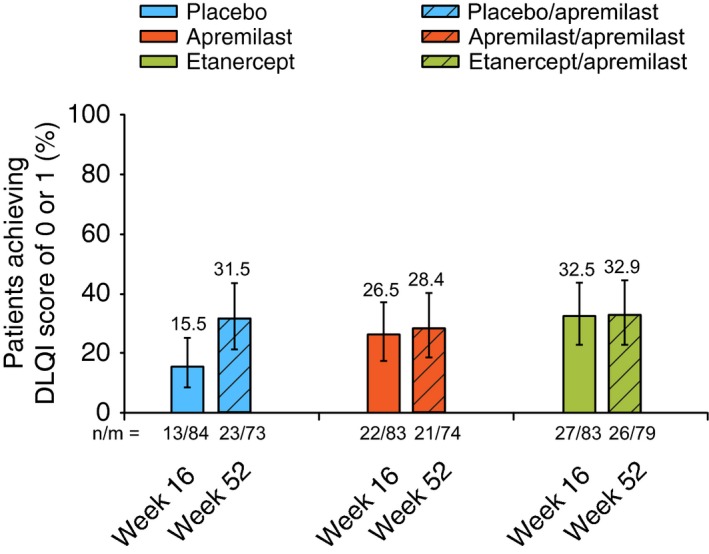

Treatment with apremilast or etanercept led to improvements from baseline at Week 16 (vs. placebo) in exploratory endpoints, including mean percentage change from baseline in PASI score, achievement of a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in DLQI score (decrease from baseline DLQI score ≥5 points)12, 13 and mean change from baseline in pruritus and skin discomfort/pain visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, Scalp Physician Global Assessment (ScPGA) response (score of 0 [clear] or 1 [minimal]) and mean percentage change from baseline in Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) score (Table 2). In a post hoc analysis (LOCF), 22 of 83 (26.5%) patients receiving apremilast and 27 of 83 (32.5%) patients receiving etanercept vs. 13 of 84 (15.5%) receiving placebo achieved a DLQI score of 0 or 1 at Week 16 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of Patients Achieving a DLQI score of 0 or 1 at Week 16 and Week 52. Based on last‐observation‐carried‐forward analysis for Weeks 16 and 52. DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Improvements in patient‐reported VAS scores for pruritus and skin discomfort/pain occurred as early as Week 2 with apremilast and etanercept vs. placebo. At Week 16, mean change from baseline in pruritus VAS was greater with apremilast and etanercept vs. placebo (Table 2; nominal P = 0.0026 apremilast vs. placebo, nominal P < 0.0001 etanercept vs. placebo), representing 56.9%, 63.6% and 36.0% reductions from baseline in mean pruritus VAS scores, respectively. A post hoc analysis (LOCF) found that an MCID in pruritus VAS (improvement of ≥20%)14 was achieved by 66 of 83 (79.5%) and 69 of 83 (83.1%) patients receiving apremilast and etanercept, respectively, vs. 45 of 84 (53.6%) patients receiving placebo at Week 16.

Results over 52 weeks

PASI‐75 response was sustained with treatment through Week 52 in patients randomized to apremilast at baseline who continued apremilast through the extension phase (apremilast/apremilast: 52.7%) and in patients switched from etanercept to apremilast at Week 16 (etanercept/apremilast: 57.0%) (Table 2). Patients switched from placebo to apremilast at Week 16 exhibited PASI‐75 responses at Week 52 (placebo/apremilast: 53.4%) that were consistent with results in patients randomized to apremilast at baseline. The non‐responder imputation sensitivity analyses demonstrated the following findings with respect to PASI‐75 response at Week 52: placebo/apremilast (47.9%), apremilast/apremilast (47.3%) and etanercept/apremilast (49.4%) (Table 2).

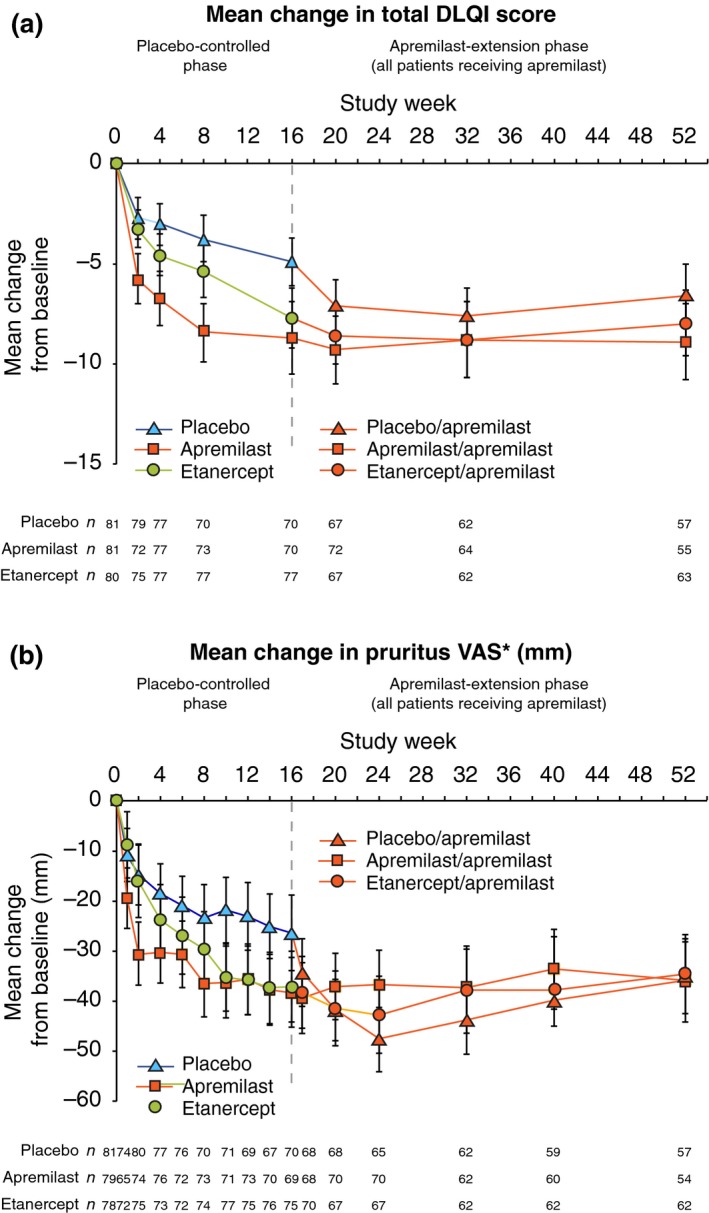

Improvements in secondary and exploratory endpoints were generally maintained at Week 52 in apremilast/apremilast patients and etanercept/apremilast patients (Fig. 5 and Table 2); responses at Week 52 among placebo/apremilast patients were generally similar to those in apremilast/apremilast patients. This pattern of clinical improvement was observed through Week 52 for the mean change in DLQI score (Table 2, LOCF; Fig. 5a, as observed), achievement of DLQI MCID (Table 2) and achievement of DLQI score of 0 or 1 (Fig. 4). Similarly, at Week 52, improvements in VAS scores for pruritus (Fig. 5b), skin discomfort/pain and patient global assessment of psoriasis disease activity (Table 2) as well as achievement of ScPGA 0 or 1 and mean percentage change in NAPSI score were sustained in the apremilast/apremilast and apremilast/etanercept groups (Table 2).

Figure 5.

(a) Mean Change in DLQI Score. Data represent the mITT population, as observed at each time point. The vertical lines indicate two‐sided 95% CIs. CI, confidence interval; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index. (b) Mean Change in Pruritus VAS Score. *Mean pruritus VAS scores (0–100 mm, where 0 = no itch at all, 100 = worst itch imaginable) were 62.5 mm (placebo), 62.6 mm (apremilast) and 57.2 mm (etanercept) at baseline. Data represent the mITT population, as observed at each time point. The vertical lines indicate two‐sided 95% CIs. VAS, visual analogue scale.

Safety

Placebo‐controlled phase: Weeks 0 to 16

A total of 250 randomized patients received ≥1 dose of study medication and were included in the safety analysis (placebo, n = 84; apremilast, n = 83; etanercept, n = 83). During the placebo‐controlled phase (Weeks 0 to 16), ≥1 AE was reported in 53.6%, 71.1% and 53.0% of patients receiving placebo, apremilast and etanercept, respectively (Table 3). Among patients with reported AEs, ≥95% of AEs were mild or moderate in severity. Severe AEs, serious AEs and AEs leading to discontinuation were infrequent and comparable across groups (Table 3). Pneumonia was the only serious AE that occurred in >1 patient (apremilast, n = 1; etanercept, n = 1). One patient treated with apremilast had community‐acquired pneumonia and sepsis, although sepsis was never confirmed; blood culture was negative, and sepsis was considered secondary to pneumonia. One serious cardiac event characterized as palpitations was reported with apremilast during the placebo‐controlled phase in a patient who had a medical history of myocardial infarction, anxiety and thyroid disease; the patient was admitted for observation and managed accordingly and continued in the study. In addition, one serious cardiac event characterized as complete atrioventricular block was reported in the etanercept group. No malignancies or serious opportunistic infections were reported. The most common AEs (in ≥5% of patients in any treatment group) were nausea, diarrhoea, upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, tension headache and headache (Table 3). In apremilast‐treated patients, more than half of the reported diarrhoea and nausea cases occurred within the first 4 weeks of dosing. These were predominantly mild in severity and generally resolved within 1 month. No patient in any group reported severe nausea or severe diarrhoea.

Table 3.

Adverse events and laboratory abnormalities during the placebo‐controlled phase (Weeks 0 to 16) and the apremilast‐extension phase (Weeks 16 to 52) (Safety population, N = 250)

| Placebo‐controlled phase: Weeks 0 to 16 | Apremilast‐extension phase: Weeks 16 to 52 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overview, patients, n (%) | Placebo n = 84 | EAIR/100 Pt‐Yrs | Apremilast n = 83 | EAIR/100 Pt‐Yrs | Etanercept n = 83 | EAIR/100 Pt‐Yrs | Placebo/Apremilastb n = 73 | EAIR/100 Pt‐Yrs | Apremilast/Apremilast n = 74 | EAIR/100 Pt‐Yrs | Etanercept/Apremilastc n = 79 | EAIR/100 Pt‐Yrs |

| ≥1 AE | 45 (53.6) | 292.0 | 59 (71.1) | 469.0 | 44 (53.0) | 288.8 | 41 (56.2) | 170.0 | 44 (59.5) | 184.9 | 49 (62.0) | 167.1 |

| ≥1 severe AE | 2 (2.4) | 8.4 | 3 (3.6) | 12.6 | 3 (3.6) | 12.0 | 3 (4.1) | 6.9 | 3 (4.1) | 6.7 | 4 (5.1) | 8.3 |

| ≥1 serious AE | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 3 (3.6) | 12.6 | 2 (2.4) | 7.9 | 4 (5.5) | 9.2 | 2 (2.7) | 4.5 | 2 (2.5) | 4.1 |

| ≥1 AE leading to drug withdrawal | 2 (2.4) | 8.3 | 3 (3.6) | 12.5 | 2 (2.4) | 7.9 | 3 (4.1) | 6.8 | 3 (4.1) | 6.7 | 2 (2.5) | 4.1 |

| Reported by ≥5% of patients in any treatment group, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Diarrhoea | 3 (3.6) | 12.9 | 9 (10.8) | 41.5 | 1 (1.2) | 4.0 | 13 (17.8) | 33.9 | 4 (5.4) | 9.3 | 6 (7.6) | 13.0 |

| Nausea | 1 (1.2) | 4.2 | 9 (10.8) | 40.9 | 4 (4.8) | 16.4 | 4 (5.5) | 9.3 | 3 (4.1) | 6.8 | 5 (6.3) | 10.8 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 2 (2.4) | 8.5 | 6 (7.2) | 25.9 | 2 (2.4) | 8.1 | 3 (4.1) | 6.9 | 4 (5.4) | 9.3 | 1 (1.3) | 2.1 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 8 (9.5) | 34.8 | 4 (4.8) | 17.0 | 8 (9.6) | 33.4 | 3 (4.1) | 7.0 | 2 (2.7) | 4.5 | 4 (5.1) | 8.5 |

| Headache | 3 (3.6) | 12.8 | 11 (13.3) | 51.6 | 5 (6.0) | 20.8 | 4 (5.5) | 9.4 | 2 (2.7) | 4.5 | 2 (2.5) | 4.2 |

| Tension headache | 4 (4.8) | 17.2 | 5 (6.0) | 21.8 | 3 (3.6) | 12.1 | 3 (4.1) | 7.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1 (1.3) | 2.1 |

| Sinusitis | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1 (1.4) | 2.2 | 4 (5.1) | 8.3 |

| Select marked laboratory abnormalities, a n/m (%) | ||||||||||||

| ALT >3 × ULN, U/L | 1/83 (1.2) | 4.2 | 1/83 (1.2) | 4.2 | 0/83 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/72 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/74 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/78 (1.3) | 2.1 |

| AST >3 × ULN, U/L | 0/83 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/83 (1.2) | 4.2 | 0/83 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/72 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/74 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/78 (1.3) | 2.1 |

| Total bilirubin >1.8 × ULN, μmol/L | 1/83 (1.2) | 4.2 | 1/83 (1.2) | 4.2 | 0/83 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/72 (1.4) | 2.3 | 0/74 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/78 (1.3) | 2.1 |

| Haemoglobin A1C >9% | 1/81 (1.2) | 4.3 | 0/79 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/81 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/72 (1.4) | 2.3 | 0/70 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/74 (0.0) | 0.0 |

| Total cholesterol >7.8 mmol/L | 4/83 (4.8) | 17.2 | 3/83 (3.6) | 12.7 | 2/83 (2.4) | 8.0 | 2/72 (2.8) | 4.6 | 5/74 (6.8) | 11.6 | 1/78 (1.3) | 2.1 |

| Triglycerides >3.4 mmol/L | 18/83 (21.7) | 84.2 | 10/83 (12.0) | 44.6 | 14/83 (16.9) | 61.0 | 8/72 (11.1) | 20.1 | 11/74 (14.9) | 27.3 | 14/78 (17.9) | 33.5 |

| Lymphocytes <0.8 × 109/L | 2/83 (2.4) | 8.4 | 3/83 (3.6) | 12.7 | 0/83 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/72 (1.4) | 2.3 | 1/74 (1.4) | 2.2 | 2/77 (2.6) | 4.2 |

| Neutrophils <1 × 109/L | 0/83 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/83 (0.0) | 0.0 | 1/83 (1.2) | 4.0 | 0/72 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/74 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0/77 (0.0) | 0.0 |

Exposure‐adjusted incidence rate (EAIR) per 100 patient‐years is defined as 100 times the number (n) of patients reporting the event divided by patient‐years within the phase (up to the first event start date for patients reporting the event). The n/m represents patients with ≥1 occurrence of the abnormality (n)/patients with ≥1 post‐baseline value (m).

All laboratory measurements are non‐fasting values.

No dose titration for apremilast.

Dose titration for apremilast.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Pt‐Yrs, patient‐years; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Apremilast‐extension phase: Weeks 16 to 52

During the apremilast‐extension phase, no increase in the incidence of common AEs was observed with continued apremilast exposure and no new safety or tolerability issues were observed in patients who switched from etanercept to apremilast at Week 16. Serious AEs, severe AEs and discontinued treatment due to AEs remained low (≤2 patients in each group) across all groups through Week 32. Incidences of common AEs through Week 32 in the placebo/apremilast, apremilast/apremilast and etanercept/apremilast groups, respectively, were nausea (4.1%, 2.7%, 6.3%), diarrhoea (16.4%, 4.1%, 7.6%), upper respiratory tract infection (1.4%, 5.4%, 0.0%), nasopharyngitis (0.0%, 1.4%, 3.8%), tension headache (4.1%, 0.0%, 0.0%) and headache (2.7%, 0.0%, 1.3%). Of note, the incidences of diarrhoea and nausea were <5.0% in the apremilast/apremilast group between Weeks 16 and 32. Diarrhoea was more frequent (16.4%) in placebo patients, who were switched to apremilast with no titration at Week 16, compared with etanercept patients, who were switched to apremilast with 1 week of titration (7.6%).

Incidence of common AEs with apremilast remained low with prolonged apremilast exposure through Week 52 compared with patients who received apremilast during Weeks 0 to 16 (Table 3). Similarly, no new AEs of clinical significance were observed in the etanercept/apremilast group through Week 52 (Table 3). Serious infection (mastoiditis) was reported in one (1.4%) patient in the apremilast/apremilast group and psychiatric events (psychotic disorder, suicidal ideation) were reported in one (1.4%) patient in the placebo/apremilast group. No serious cardiac events or malignancies were reported during the Weeks 16 to 52 apremilast‐extension phase. No cases of tuberculosis were reported in the study. No clinically meaningful changes in laboratory parameters were reported during the placebo‐controlled phase or the apremilast‐extension phase (Table 3). During the placebo‐controlled phase, mean weight change from baseline was +0.03 kg with placebo, −0.78 kg with apremilast and +1.10 kg with etanercept. Mean weight change from baseline was −1.23 kg, −0.63 kg and −0.03 kg in the placebo/apremilast, apremilast/apremilast and etanercept/apremilast groups, respectively, during the apremilast‐extension period (Table 4).

Table 4.

Weight assessments during the placebo‐controlled phase (Weeks 0 to 16) and the apremilast‐extension phase (Weeks 16 to 52)

| Bodyweight assessments | Placebo‐controlled phase: Weeks 0 to 16 | Apremilast‐extension phase: Weeks 16 to 52 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo n = 73 | Apremilast n = 74 | Etanercept n = 81 | Placebo/Apremilastb n = 70 | Apremilast/Apremilast n = 70 | Etanercept/Apremilastc n = 75 | |

| Baseline weight, kg,mean (SD) | 89.8 (24.0) | 89.9 (19.7) | 88.4 (20.5) | 90.5 (23.7) | 89.6 (19.9) | 88.7 (19.8) |

| Mean (SD) change from baseline, kg | +0.03 (3.127) | −0.78 (3.256) | +1.10 (3.079) | −1.23 (4.082) | −0.63 (3.992) | −0.03 (3.827) |

| Median (min, max) change from baseline, kg | +0.20 (−10.0, 10.0) | −0.90 (−9.9, 8.5) | +1.00 (−8.7, 12.4) | −1.05 (−14.0, 9.0) | −0.85 (−11.8, 14.9) | −0.20 (−11.1, 10.0) |

| Patients with >5% weight loss, n/m (%)a | 4/83 (4.8) | 10/81 (12.3) | 5/83 (6.0) | 13/70 (18.6) | 7/70 (10.0) | 6/75 (8.0) |

n/m, the number of patients with ≥1 occurrence at any time point/number of patients with ≥1 post‐baseline value.

No dose titration for apremilast.

Dose titration for apremilast.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that apremilast is an effective treatment option for biologic‐naive patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. The primary endpoint in this study was met, with a significantly greater proportion of patients treated with apremilast achieving a PASI‐75 response at Week 16 vs. placebo. The study also demonstrated that etanercept, as compared with placebo, was effective in the treatment of biologic‐naive patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. A post hoc analysis of PASI‐75 achievement at Week 16 revealed non‐significant differences between apremilast and etanercept. Although etanercept‐treated patients had a numerically higher PASI‐75 achievement rate than apremilast‐treated patients, the study was not powered to detect such a difference between groups.

In addition to sustained improvements in PASI‐75 response, improvement of psoriasis symptoms (i.e. pruritus and skin discomfort/pain) and quality of life were observed as early as Week 2 and were sustained in patients who were randomized to apremilast at baseline and continued to receive apremilast through Week 52. Improvements in scalp psoriasis observed at Week 16 were also maintained through Week 52 with apremilast. Mean change in NAPSI score continued to improve in patients who received apremilast through 52 weeks of treatment. Slower growth of fingernails may contribute to the lag in observed nail improvements compared with improvements in skin, and studies with biologic agents, including etanercept, have demonstrated continued improvement beyond 6 months.15, 16

In this study, most AEs were consistent with the known safety profiles of apremilast and etanercept. No increase in AEs was observed with prolonged apremilast exposure in patients who continued apremilast through Week 52 compared with Weeks 0 to 16. Higher rates of diarrhoea were observed in patients in the placebo group, who switched to apremilast without titration, vs. patients who began apremilast dosing with titration. It should be noted that the prescribing information for apremilast states that the initial dose of apremilast should be titrated over the first 5 days of administration to reduce risk of gastrointestinal symptoms.17, 18 No safety signal was detected in serious opportunistic infections, malignancies and serious cardiac events, consistent with previous studies.10, 11 In addition, no clinically meaningful changes in laboratory parameters were reported. Analysis of patients switching from etanercept to apremilast at Week 16 revealed no clinically significant safety findings through Week 52 in this study.

Weight loss has been observed in clinical studies with apremilast.10, 11 Weight gain has been noted with anti‐tumour necrosis factor‐α therapies, and it is notable that the weight gain observed in the etanercept group during the placebo‐controlled phase was reversed after patients switched to apremilast at Week 16. During the long‐term apremilast‐extension phase, weight loss did not lead to any overt medical sequelae or manifestations. In addition, the efficacy achieved with etanercept at Week 16 was generally maintained through Week 52 with apremilast.19

Limitations

This study was not designed to directly compare apremilast and etanercept, and the comparison of PASI‐75 response is limited by the post hoc nature of the analysis. The hierarchical analysis of study endpoints also limits the ability to detect differences in efficacy between the active treatment arms and placebo in some secondary endpoints. Another potential limitation of the study was the use of the 50 mg QW dose of etanercept in the active‐controlled arm, which may contribute to an underestimation of etanercept efficacy. However, it should be noted that a starting dosage of 50 mg QW has been shown to be efficacious in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis20 and is consistent with some dosing recommendations for etanercept.21, 22 A study investigating dosage patterns of etanercept during the first year of treatment for psoriasis in a general managed‐care population using a US claims database found that the starting dose of etanercept varied, and that up to one‐quarter of patients (25.8%) initiated etanercept at 50 mg QW.23 Additionally, the ability to administer injections once weekly during scheduled study office visits to maintain the blinding of patients and physicians contributed to the selection of the 50 mg QW dose for the LIBERATE study.

Patients receiving etanercept transitioned to apremilast regardless of clinical response, which may not reflect real‐world clinical scenarios; clinically, switching would likely be predicated on poor clinical response or safety findings. The results cannot be generalized to non‐plaque forms of psoriasis.

Conclusions

Apremilast and etanercept significantly reduced the severity of moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis over 16 weeks in biologic‐naive patients. Improvements were generally sustained through Week 52 in patients who continued apremilast at Week 16 across a range of endpoints, including patient‐reported outcomes, that contribute significantly to patients' disease severity and quality of life. Apremilast demonstrated an acceptable safety profile through Week 52, with no need for extensive laboratory monitoring. In addition, switching from etanercept to apremilast was well tolerated with no new safety findings; efficacy was generally maintained through Week 52 with apremilast. The findings from LIBERATE demonstrate that oral apremilast is an effective therapeutic option for the treatment of biologic‐naive patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis and provide important safety information for clinicians regarding switching from a biologic therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dale McElveen, Markus Kocher (clinical operations); Lilia Pineda, John Marcsisin, Claire Barcellona (clinical); Marlene Kachnowski (data management); Ann Marie Tomasetti, Trisha Zhang (programming); Nilam Shah, Maria Paris (safety); and Ziqi Liu (statistics). The authors would also like to thank all investigators and patients for their participation in this study. The authors received editorial support in the preparation of the manuscript from Kathy Covino, PhD, of Peloton Advantage, funded by Celgene Corporation.

Conflicts of interest

K. Reich has received honoraria as a consultant and/or advisory board member and/or acted as a paid speaker and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Centocor, Covagen, Eli Lilly, Forward Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen‐Cilag, LEO Pharma, Medac, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Novartis, Ocean Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, Takeda, UCB Pharma and XenoPort. M. Gooderham has received honoraria, grants and/or research funding as a speaker, investigator, advisory board member, data safety monitoring board member and/or consultant for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Astellas Pharma US, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene Corporation, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Pharma, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche Laboratories and Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA Inc. L. Green has been a speaker, advisory board member and/or investigator for Amgen, AbbVie, Celgene Corporation, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer and Valeant. A. Bewley has had ad hoc consultancy agreements with AbbVie, Celgene Corporation, Galderma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Novartis and Stiefel (a GSK company). Z. Zhang, R. M. Day and J. Goncalves are employees of and own stock/stock options in Celgene Corporation. K. Shah and I. Khanskaya were employees of Celgene Corporation at the time of study conduct and own stock, stock options and restricted stock units in Celgene Corporation. V. Piguet has been a principal investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Celgene Corporation and has received honoraria and/or grants as a speaker, advisory board member and/or investigator for AbbVie, Celgene Corporation, Almirall, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen and Novartis. J. Soung has received honoraria and/or grants as a speaker, advisory board member and/or investigator for AbbVie, Actelion, Allergan, Amgen, Cassiopeia, Celgene Corporation, Cutanea, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Genentech, GenZum, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Kadmon, LEO Pharma, Merz, Pfizer, Regeneron and/or Valeant.

Funding sources

This study was sponsored by Celgene Corporation.

References

- 1. Reich K. The concept of psoriasis as a systemic inflammation: implications for disease management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012; 26(Suppl 2): 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coimbra S, Figueiredo A, Castro E, Rocha‐Pereira P, Santos‐Silva A. The roles of cells and cytokines in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51: 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taheri A, Sandoval LF, Moradi Tuchay S, Alinia H, Mansoori P, Feldman SR. Emerging treatment options for psoriasis. Psoriasis Targets Ther 2014; 4: 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol 2012; 83: 1583–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schafer PH, Parton A, Capone L et al Apremilast is a selective PDE4 inhibitor with regulatory effects on innate immunity. Cell Signal 2014; 26: 2016–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perez‐Aso M, Montesinos MC, Mediero A, Wilder T, Schafer PH, Cronstein B. Apremilast, a novel phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, regulates inflammation through multiple cAMP downstream effectors. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17: 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez‐Reino JJ et al Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomized, placebo‐controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 1020–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez‐Reino JJ et al Longterm (52‐week) results of a phase III randomized, controlled trial of apremilast in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2015; 42: 479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edwards CJ, Blanco FJ, Crowley J et al Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with psoriatic arthritis and current skin involvement: a phase III, randomised, controlled trial (PALACE 3). Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 1065–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL et al Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM 1]). J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73: 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paul C, Cather J, Gooderham M et al Efficacy and safety of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis over 52 weeks: a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (ESTEEM 2). Br J Dermatol 2015; 173: 1387–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khilji FA, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. Clinical meaning of change in dermatology life quality index scores [abstract P‐59]. Br J Dermatol 2002; 147(suppl 62): 50. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, Sturkey R, Finlay AY. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology 2015; 230: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reich A, Medrek K, Stander S, Szepietowski JC. Determination of minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of visual analogue scale (VAS): in which direction should we proceed? [abstract IL26]. Acta Derm Venereol 2013; 93: 609–610. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crowley JJ, Weinberg JM, Wu JJ, Robertson AD, Van Voorhees AS. Treatment of nail psoriasis: best practice recommendations from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ortonne JP, Paul C, Berardesca E et al A 24‐week randomized clinical trial investigating the efficacy and safety of two doses of etanercept in nail psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 1080–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Celgene Corporation . Otezla [package insert]. Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Celgene Europe Ltd . Otezla [summary of product characteristics]. Celgene Europe Ltd, Uxbridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saraceno R, Schipani C, Mazzotta A et al Effect of anti‐tumor necrosis factor‐alpha therapies on body mass index in patients with psoriasis. Pharmacol Res 2008; 57: 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van de Kerkhof PC, Segaert S, Lahfa M et al Once weekly administration of etanercept 50 mg is efficacious and well tolerated in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial with open‐label extension. Br J Dermatol 2008; 159: 1177–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals . Enbrel [summary of product characteristics]. Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Hampshire, United Kingdom, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Puig L, Carrascosa JM, Dauden E et al Spanish evidence‐based guidelines on the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis with biologic agents. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2009; 100: 386–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu EQ, Feldman SR, Chen L et al Utilization pattern of etanercept and its cost implications in moderate to severe psoriasis in a managed care population. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 3493–3501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]