Abstract

Introduction

This study examined the prevalence of the use of different complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) strategies, families’ attitudes and belief systems about the use of these strategies, and the economic burden of these strategies placed on family income in families of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Method

A questionnaire survey concerning the use of CAM in children with ASD was administered to parents in the five different geographic locations in Turkey.

Result

Of the 172 respondents, 56% had used at least one CAM therapy. The most frequently used CAM intervention was spiritual healing. Among the most reported reasons for seeking CAM were dissatisfaction with conventional interventions and a search for ways to enhance the effectiveness of conventional treatments. The most frequently reported source of recommendation for CAM was advice from family members. The mean economic burden of the CAM methods was a total of 4,005 Turkish lira ($2,670) in the sample using CAM. The CAM usage rate was lower in parents who suspected genetic/congenital factors for the development of ASD.

Conclusion

This study observed the importance of socioeconomic and cultural factors as well as parents’ beliefs about the etiology of ASD in treatment decisions about CAM.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, autism, complementary and alternative medicine, treatment

ÖZET

Giriş

Bu çalışmada otizm spektrum bozuklug̃u (OSB) olan çocuklarda tamamlayıcı ve alternatif tıp (TAT) uygulamalarının kullanım sıklıg̃ı, ailelerin bu uygulamalar hakkındaki tutum ve inançları ve bu uygulamaların aile bütçesine olan ekonomik yükü incelendi.

Yöntem

Bu amaçlara ulaşılması için Türkiye’nin beş farklı bölgesinde OSB’li çocuklarda TAT uygulamaları hakkında çocukların ebeveynlerine bir anket uygulandı

Bulgular

Yüz yetmiş iki kişilik örneklemin %56’sının TAT uygulamalarını kullandıg̃ı saptandı. En sık kullanılan TAT yönteminin dua okutma oldug̃u belirlendi. TAT yöntemlerine başvurma nedeni olarak en sık konvansiyonel tedavilerin tatmin edici olmaması ve konvansiyonel tedavilerin etkinlig̃inin arttırılması isteg̃i gösterildi. TAT uygulamaları hakkında en fazla bilgi alınan kaynag̃ın ise aile bireyleri oldug̃u belirtildi. TAT uygulamalarını kullananlarda bu uygulamaların toplam maliyeti 4005 Türk lirası (2670 dolar) olarak belirlendi. TAT kullanım oranı OSB gelişimi açısından genetik/konjenital faktörleri suçlayanlarda daha düşüktü.

Sonuç

Bu çalışma sosyoekonomik ve kültürel faktörlerin ve ebeveynlerin OSB etiyolojisi hakkındaki inançlarının TAT yöntemlerine başvuru açısından önemini göstermektedir.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD), which includes the diagnoses of autism, Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), and Asperger’s Disorder (AD) are lifelong neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by severe qualitative impairments in reciprocal social interaction; communication; and restricted, repetitive behavior, interests, and activities. The rate of children diagnosed with ASD has increased, and a recent estimate about the prevalence of these disorders is close to 1% (1). The etiology of the ASD is not known, although these disorders are currently seen as genetic conditions (2). While there are many behavioral and educational interventions that enhance communication, promote developmental progress, and manage behavioral difficulties, none are curative (3).

Because of the high prevalence rate and the lack of effective treatment, many theories about the etiology of ASD have been proposed (3,4). Those theories have resulted in numerous biological or nonbiological treatment suggestions, such as gluten-free or casein-free diets, secretin, withholding immunizations, or craniosacral manipulation. These methods are considered to be outside of conventional medicinal, educational, and behavioral interventions. They are termed complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the literature and CAM methods are commonly used in children with ASD as well as other childhood neuropsychiatric disorders (5,6,7,8,9). Some of these CAM strategies have been popularized by the media and implemented by families before standard scientific validation of safety and efficacy has occurred.

Researchers observed that over half of the families of children with ASD are using CAM therapies for their child, and they often believe that CAM would improve their child’s health and well-being (6,7,8,9). However, many physicians do not know that their clients are using these treatments (8,10). Because parents of the children with ASD felt a barrier to telling their physicians, this prevented an open discussion with their physician about CAM strategies, and parents may be hesitant about reporting their CAM use (8). Parents of children with autism spectrum disorders experience more psychiatric difficulties and family problems compared to general population (11). Considering that CAM strategies may cause physical harm and bring extra emotional and economic burdens to the family, physician awareness of the use of CAM treatments is very important in patients with ASD.

CAM use appears to be strictly related to cultural factors (12,13,14). Studies showed that most families used biological-based therapies, such as dietary management, vitamins and minerals, or chelation therapy in western countries (6,7,8). However, Wong reported that only a small minority of parents in Hong Kong used these biological-based strategies, and acupuncture and traditional Chinese medicine were the main CAM therapies used in Hong Kong. The results of the published studies are not generalized for Turkish children. So far, there had been only one study concerning CAM use in children with ASD in Turkey, and it had a small sample size (15). In this study, a survey questionnaire was mailed to more than 400 parents with ASD. However, only 44 parents wanted to participate in the study, and only 38 were kept for analyses, because of survey filing and recording errors. Parents mentioned vitamins and minerals, special diet, sensory integration, other dietary supplements, and chelation as five most frequently used CAM treatments.

In the present study, we surveyed parents of children with ASD to explore the use of conventional medicine and CAM, the attitudes about the use of these interventions, the belief systems about etiology of ASD, and the economic burden of these interventions. We surveyed families from different sociocultural levels in Turkey. To achieve this goal, our study was conducted in five different geographic locations in Turkey, and it consisted of face to face interviews with parents.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of a series of children under 18 years of age who were admitted to one of six child and adolescent psychiatry clinics in five different geographic locations in Turkey. The six study sites were Gulhane Military Medical Academy (n=16), Ankara University Faculty of Medicine (n=18), Istanbul Bakirkoy Prof. Dr. Mazhar Osman Mental Health and Neurology Training and Research Hospital (n=50), Ordu Government Hospital (n=27), Malatya Government Hospital (n=37), and Mersin Woman’s and Children’s Hospital (n = 24). Three of the study centers were secondary healthcare settings, and three of them were tertiary centers. This cross-sectional survey was conducted from April 2010 to January 2011, and a total of 172 outpatients participated in the study. Patients were considered suitable for the study if the diagnosis of ASD was present for at least six months prior to the study. All information was collected from the parents of the children with ASD through a questionnaire designed by a child and adolescent psychiatrist. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee, and the parents of the subjects, who agreed to take part, provided informed consent.

Measures

The diagnostic category of ASD confirmed by a child and adolescent psychiatrist was based on a comprehensive history followed by an assessment based on DSM-IV criteria (15). The interviewer-administered questionnaire inquired about sociodemographic and medical information. The parents were given a definition of CAM therapy and all CAM therapy types, and then were requested to note which therapies had been used with their child. The parents could have multiple responses about CAM therapies. Educational and behavioral techniques and prescription drugs were considered conventional interventions. Additionally, because sensory integration therapies are widely implemented in the special education center, we have not considered these interventions as CAM methods. The perceived helpfulness of the various interventions, the reason for seeking CAM use, the source of recommendation about CAM treatments, and the family economic burden of the CAM therapies were also evaluated in the groups who used CAMs. Whether parents had communication with their physicians about CAM therapies, their personal preference on the choice of treatment for autism, and their belief about the etiology of the ASD were assessed throughout the entire sample (please refer to Appendix).

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the data was performed using the statistical software SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). The descriptive statistics of patients’ characteristics and the clinical features were calculated. Student t-test and correlation analyses were used to compare continuous variables, and the chi-square test compared the categorical variables. All the statistical tests were two-sided, and p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Most of the 172 children with ASD were male (81%), which is compatible with the male-female ratio for ASD disorders. Of the patients, 85% had a diagnosis of autism, 14% had a diagnosis of PDD-NOS, and 1% had a diagnosis of AD. The mean disease duration from diagnosis was more than five years. The number of admissions to a psychiatric clinic was approximately four in the last year. The majority of the families had low or medium socioeconomic status. Almost all of the patients (99%) had used conventional treatment methods. Of the parents, 6% (11/171) reported very high efficacy, 40% (69/171) high efficacy, 29% (49/171) moderate efficacy, 20% (34/171) a little efficacy, and 4% (8/171) had no efficacy with conventional interventions. The sociodemographic and patient characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic features of children with autism spectrum disorders

| Characteristic | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean±SD) (year) | 8.8±3.7 |

| Gender (n=172) | |

| Male | 139 (81%) |

| Female | 33 (19%) |

| Diagnoses (n=172) | |

| Autism | 146 (85%) |

| PDD-NOS | 24 (14%) |

| Asperger Disorder’s | 2 (1%) |

| Maternal education (Mean±SD) (year) (n=172) | 7.8±4.0 |

| Paternal education (Mean±SD) (year) (n=172) | 9.1±3.9 |

| Number of children | 2.2±1.1 |

| Family income (n=171) | |

| ≤ 500 TL ($330) monthly | 14 (8%) |

| 500–1,000 TL ($330–660) monthly | 51 (30%) |

| 1,000–2,000 TL ($660–1,320) monthly | 61 (36%) |

| 2,000–3,000 TL ($1,320–1,980) monthly | 33 (19%) |

| >3,000 TL ($1,980) monthly | 12 (7%) |

| Years since diagnosis (Mean±SD) | 5.6±3.6 |

| Number of admission to a psychiatry clinic (per year) (Mean±SD) | 4.1±2.9 |

| Conventional treatments (n=171) | |

| History of educational and behavioural techniques | 170 (99%) |

| History of pharmacotherapy drugs | 127 (74%) |

SD, Standard deviation; PDD-NOS, Pervasive developmental disorders-not otherwise specified; TL, Turkish lira

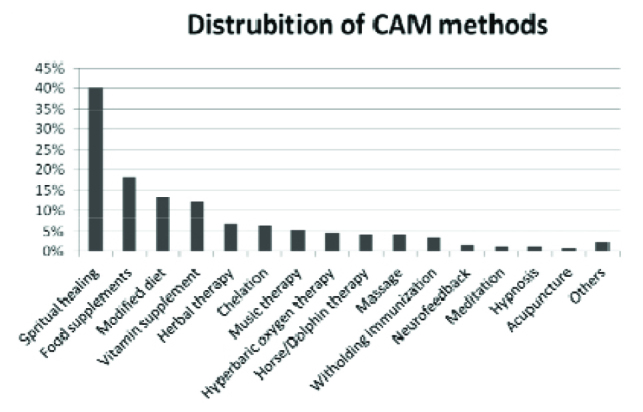

Overall, 97 parents (56%) had used CAM therapies for their child. The most frequently used CAM interventions were spiritual healing, food supplements, modified diet (such as gluten-free, casein-free, wheat-free, or sugar-free diets), and vitamin supplements, in that order. The rate of biological-based therapy use was 30% (51/171). Of the sample, 57% (55/97) had tried only one CAM, 12% (12/97) had tried two, 11% (11/97) had tried three, and 20% (19/97) had tried four to nine strategies. The mean number of treatments was 2.2±1.8. Mothers’ and fathers’ education levels and high family income had an increasing effect on the number of treatments that were tried (r=0.39, p<0.001; r=0.35, p=0.001; rs=0.25, p=0.016, respectively). No relationship was found between the number of treatments that were tried and the other variables. The frequency of different CAM strategies used in the children with autism spectrum disorders is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The frequency of complementary and alternative therapies used in children with autism spectrum disorders (%)

There were no differences in CAM use regarding gender, age, number of children, parental education, duration from diagnosis, diagnosis category, or the perceived helpfulness of conventional interventions. We think that the use of spiritual healing is related to cultural beliefs, and there are unique reasons to refer to it compared to other CAM methods. Therefore, 41 patients who used only spiritual healing were excluded, and the same analysis was performed again. There were associations between mothers’ and fathers’ education levels and CAM use when spiritual healing was excluded (f=15.5, p<0.001; f=10.1, p=0.002, respectively). In addition, the number of children in the family was negatively related to CAM use when spiritual healing was excluded (f=10.8, p=0.001).

Dissatisfaction with conventional interventions and an attempt to enhance the effectiveness of conventional treatments were among the most reported reasons for seeking CAM methods (Table 2). The most reported source for getting information about CAM was advice from family members. Other common sources of advice were other parents who had children with ASD and websites or media (Table 2). We also evaluated whether or not a child’s physician had informed parents about CAM therapies. Only 23% (40/172) of parents communicated with their physicians about CAM, and 3% (5/172) even reported that their request for information on CAM had been rejected by their physicians.

Table 2.

Reasons of complementary and alternative therapy use and source of recommendation about these therapies in children with autism spectrum disorders

| Characteristic | n | Count (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Reason of CAM use | ||

| Inefficacy of conventional interventions | 96 | 31 (32%) |

| Enhancing of efficacy of conventional interventions | 96 | 27 (28%) |

| Cultural tradition/family tradition | 97 | 20 (21%) |

| Belief that the etiology of ASD is related to CAM theories | 97 | 12 (12%) |

| Preferred natural therapies | 97 | 12 (12%) |

| Avoiding side effects of pharmacotherapy | 96 | 6 (6%) |

| Others | 97 | 16 (16%) |

| Source of recommendation | ||

| Family members | 95 | 50 (53%) |

| Other parents who had children with ASD | 96 | 20 (21%) |

| Media/websites | 96 | 19 (20%) |

| Physician recommended | 95 | 15 (16%) |

| Preferred by the special educator of children | 96 | 6 (6%) |

| Herbalist | 95 | 4 (4%) |

| Others | 95 | 3 (3%) |

CAM: complementary and alternative therapy; ASD: autism spectrum disorders, Note: Parents might have chosen more than one option to report which factors have a role of the etiology of ASD

Parent perception of the efficacy of CAM interventions and the economic burden of the CAM use were also evaluated. The satisfaction rating for CAM was lower than that for conventional interventions. Of the parents, 74% (71/96) reported no efficacy, 18% (17/96) a little efficacy, 4% (4/96) moderate efficacy, 2% (2/96) high efficacy, and 1% (1/96) very high efficacy in their CAM use. Satisfaction was somewhat higher in the spiritual healing-excluded group with a 64% (36/56) no efficacy rating. On the other hand, only 9% (9/96) of families reported that any of the interventions were harmful. The mean total economic burden of CAM methods until the time of interview was 4.005±13.150 (0–100000) Turkish lira [$2.670±8.767 ($0–66,000)]. The amount of money spent was positively associated with the mothers’ education level and years since diagnosis (r=0.21, p=0.04; r=0.22, p=0.03). However, fathers’ education level was not related with economic burden and family income.

We examined the personal preference of the parents’ choice of treatment for their children. About 83% (138/167) of the parents reported using only conventional medicine as their preference, and none of them preferred only CAM interventions. On the other hand, 17% of them (29/167) preferred both methods. Higher educational level in mothers was related to preference for both conventional and CAM interventions (t=1.98, p=0.049).

Finally, we examined the parents’ beliefs about the etiology of ASD and its relationship with CAM use. With regard to the etiology of ASD, approximately half of the parents suspected genetic/congenital factors and birth complications. Poor parental style, immunization, and mercury toxicity followed, and a minority of families reported other reasons (Table 3). The rate of CAM use was lower in the parents who suspected the role of genetic/congenital factors (χ2=7.1, p=0.008). The belief that immunization may cause ASD was also positively related to CAM use (χ2=4.8, p=0.03).

Table 3.

Parents’ beliefs about etiology of autism spectrum disorders (n=171)

| Characteristic | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Genetics/Congenital factors | 74 (43%) |

| Birth complications | 79 (46%) |

| Poor parental style | 34 (20%) |

| Toxicity of mercury | 24 (14%) |

| Immunization | 28 (16%) |

| Foods | 14 (8%) |

| Physical trauma | 13 (8%) |

| Infections | 15 (8.8%) |

| Antibiotics | 5 (3%) |

| Prematurity | 9 (5%) |

| Medical interventions/Mistakes of the physicians | 6 (5%) |

| No idea | 17 (10%) |

| Febrile convulsions | 7 (4%) |

| Destiny | 8 (4%) |

| Others | 24 (14%) |

Note: Parents might have chosen more than one option to report which factors have a role of the etiology of ASD, that is why the total of the percentages are more than 100.

Discussion

The present study indicated that 56% of children diagnosed with ASD have used CAM treatments. Previous studies reported a wide range (30 to 92%) of CAM use in children with ASD. This discrepancy appears to be related to the methodological difference among these studies (6,8,14,17,18). Studies on CAM use have generally used retrospective card reviews of hospital records (18), phone interviews (8), or mailed questionnaires (6,7,15). A study conducted by Levy et al. (17) has used an unstructured interview method, but its sample consisted of only newly diagnosed or suspected cases. Additionally, there is a lack of agreement about which treatments were classified as CAM in these reports. Therefore, we could not perform a direct comparison between our results and previous ones.

Studies have generally observed that the most used CAM strategies in Western countries were biological-based therapies (6,8,17). However, the main form of CAM therapy in our study was spiritual healing. CAM therapy use has been strictly linked to cultural factors (12,13). Since the causes of psychiatric disorders are easily attributed to spiritual events by general public (19), we consider that our results are related to prevailing beliefs about mental diseases in Turkey. Although a study (15) conducted on Turkish children reported biological-based therapy as the most frequently used strategy, the sociocultural level of the parents was higher compared to the sample in our study. Another study (14) performed in Hong Kong also supported the importance of cultural differences in CAM use. In this study, Wong found that acupuncture was the most common CAM used in Chinese children, and the use of biological-based therapy was uncommon (2.5%). Consistent with Western countries, other popular practices in Turkish children for the treatment of ASD included food supplements, modified diet, and vitamin supplements. However, the use of these biological-based therapies was rare compared to that of Western families (70–71% in Canada, 54% in Boston), and this rate was 30% in our study.

CAM use was not related to demographic or clinical variables for the entire subjects in our study. We have considered that the individual motivations for trying alternative medical approaches are similar across different groups. Nevertheless, when spiritual healing was excluded, there were associations of higher education level of the parents with the number of children they had and their CAM use. A link between higher education and CAM therapy use has also been established in studies conducted in the United States (US) and Canada (6,8). However, supporting results were not reported in a study (14) conducted in Chinese children, whose parents mostly used acupuncture as a CAM strategy. We suggest that the higher education level of the parents seems to be related to the use of biological-based CAM strategies. On the other hand, previous studies done in Canada and Hong Kong found no relationship between the number of children in the household and CAM use (8,14). Our result is not compatible with these other studies when spiritual healing use is excluded from the sample. This has led us to consider that the difference may be related to the lower socioeconomic status of our sample compared to the participants in these studies. Because a higher number of children create an economic burden on family income, this could prevent the use of expensive CAM strategies.

The average number of CAM treatments that were tried was 2.2 and showed an increase when the parents had higher education levels and family incomes. Şenel (15) reported that an average of five CAM treatments was tried by 38 parents of Turkish children. The research of Green et al. (20) found an average of seven CAM treatments, but more treatments were used for more severe cases and younger children. These two studies were based on an internet survey, and their sample had higher sociocultural levels than ours. These results also supported the importance of study design and sociocultural factors for CAM use.

The approval rate of conventional therapies was higher in our study. Almost all of the families had used conventional therapies, and these therapies were reported as helpful, at least moderately, by more than two-thirds of the parents. However, no association was observed between the perceived efficacy of conventional interventions and the prevalence of CAM use. This result suggests that the use of CAM strategies is based on different and complicated factors (21). On the other hand, most CAM was reported by families as having no effect. The rate of satisfaction for CAM therapies was lower in our study compared to the literature with 74% and 65% no efficacy rates for the total sample and spiritual healing-excluded group, respectively. In their study, Wong and Smith reported that 75% of the parents in the ASD group felt that biological-based therapies were beneficial to their children (8). In other studies, about half of those using CAM modalities found them useful (6,14). We suggest that this discrepancy among studies may be related to methodology. The parents were directly interviewed by a physician in our study, and this could have affected their answers, if they felt the physician would not approve of CAM use. Very few families reported that any of the CAM interventions were harmful.

In the present study, widely reported reasons for choosing CAM therapies included the disappointment with conventional interventions, attempts to enhance the effectiveness of conventional treatments, and cultural traditions. This issue was also evaluated by Hanson et al. (6) in the US, and concerns with the safety and side effects of prescription drugs were found to be the most cited reason for CAM use. We consider that this inconsistency among studies may be related to sociocultural differences in samples. The lower educational level of parents in our study, the dominant role of the physicians over the patient, and the patient-physician relationships in Turkish culture may prevent families from deviating from conventional treatments.

We observed that only 23% of the parents who had used CAM therapies had informed their physicians. The rate of getting information from physician about CAM therapies for ASD was reported as 62% in Canada (8). Other studies from the US showed that 53% of the surveyed caregivers reported a desire to discuss CAM therapy use with their pediatricians, but only 36% of the parents who had used CAM for their child had discussed it (22). Studies have found that patients anticipate disinterest and disapproval from their physician regarding CAM therapies, which may preclude parent physician communication about CAM use (10,22,23). We have considered that this negative anticipation, which prevents disclosure of CAM use, may be stronger in Turkey.

CAM therapies were chosen by families because of advice from multiple sources. The main source of information about CAM strategies was family members/friends in our study. Other families that have children with ASD and websites/media followed as the next highest source of CAM information. Şenel (15) found that the families of Turkish children generally decided to try CAM treatments due to other parents’ results and advice, searches on the internet or information from books, scientific journals or from medical doctors. In Şenel’s study, the role of relatives/friends was very low (2%), which is inconsistent with our study. Although both Şenel’s research and our study were conducted in Turkey, there were discrepancies among the results. We consider that the importance of the socioeconomic and cultural status of the sample is demonstrated in the recommendation source for CAM therapies. Şenel’s study employed a mailed survey questionnaire, and 71% of parents had undergraduate or graduate level education; on the other hand, we conducted our study in the hospital setting, and the mean duration of education for mothers and fathers was only 7.8 and 9.1 years, respectively. In another study, Harrington et al. (7) reported that in the US, parents selected therapies based primarily on the advice of physicians/nurses. However, in our study, the role of physicians with regard to CAM therapies was lower. This could be related to the fact that there are many practitioners aligned with the CAM approach in the US (24) as well as to the cultural differences associated with the patient-physician relationship in the US and Turkey.

We found that the use of CAM strategies led to a significant economic burden on families in Turkey. Although 93% of the families in our sample had a monthly family income of less than 3,000 Turkish lira ($1,980), the mean total cost of the CAM methods used at the time of the interview was 4005 Turkish lira ($2,670). Interestingly, the amount of money spent on CAM use was related to the education level of the mothers and the length of time since the diagnosis, but not family income. In the present study, the mother’s education level appeared to be among the most important variables for CAM use because it showed relationships with both the trying CAM methods and the amount of spending money. On the other hand, an increased length of time since the diagnosis may be associated with greater frustration among the families, giving rise to CAM use. Longer lengths of time since the child was diagnosed may allow for the opportunity to receive more information about these methods, as well.

Parents’ ideas about the use of unconventional medicine were very optimistic in previous studies (6,8,13). These studies also observed that parents tend to use conventional and unconventional medicine concurrently. However, only 17% of the parents reported the preference of using both conventional and unconventional medicine, and none of them used only CAM strategies, in our survey. In line with other studies, we observed that the choice of CAM therapy is higher among parents with higher education levels. When considering this finding, the discrepancy between our study and previous studies in choosing treatments may be related to lower parent-education levels in our sample. Additionally, the face to face interview design may cause parents to feel the physician would disapprove of their preference and it may give rise to the lack of parental disclosure of CAM use.

We also evaluated parents’ beliefs concerning the etiology of ASD and their relationship with CAM use. It was found that about half of the parents suspected genetic/congenital factors and birth complications. The parents mentioned poor parental style, immunization, and mercury toxicity as the three most common reasons for developing ASD. The parents who suspected the role of genetic/congenital factors were less likely to use CAM therapy. On the other hand, CAM use was greater among parents who believed that immunization cause the development of ASD. We have considered that these results point to the importance of informing families about the etiology of the ASD.

There were some limitations in this study. The questions were asked by a child and adolescent psychiatrist, and this may have resulted in an unwillingness to give information, as parents may have been hesitant to report CAM use to their physicians in a hospital setting. This may have led to under-reporting of CAM use and discrepancies in other related variables. Another limitation is that because children with ASD, especially those in a low socioeconomic and cultural bracket, are usually admitted to hospital for the management of severe behavioral problems in Turkey, the rate of the patients who were diagnosed as PDD-NOS or AD was very low in this study. However, there was also a major strength in the current study. The data were collected from a sample at six different clinics in the five distinct geographic locations in Turkey, which may better represents the general population compared to previous studies.

In conclusion, over half of the parents of children with ASD reported using or having used at least one CAM therapy for their child, and the economic burden of the CAM methods on family income was very high. Given the frequency of parental use of a variety of CAM therapies in Turkey, caregivers should inquire about CAM usage in all ASD patients. CAM methods may cause physical harm and bring extra emotional and economic burdens to families and, parents are less likely to independently offer information about CAM use to their physicians. Lack of parental disclosure of CAM use to their physicians, due to expectations of disapproval and in inadequate therapeutic alliance, precludes the dissemination CAM education from accurate sources. The lower CAM usage rate in parents who had more accurate knowledge about ASD etiology demonstrates the importance of the physician-patient relationship.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors reported no conflict of interest related to this article.

Çıkar çatışması: Yazarlar bu makale ile ilgili olarak herhangi bir çıkar çatışması bildirmemişlerdir.

References

- 1.Lazoff T, Zhong L, Piperni T, Fombonne E. Prevalence of pervasive developmental disorders among children at the English Montreal School Board. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:715–720. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veenstra-Vanderweele J, Christian SL, Cook EH., Jr Autism as a paradigmatic complex genetic disorder. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2004;5:379–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.5.061903.180050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy SE, Hyman SL. Use of complementary and alternative treatments for children with autistic spectrum disorders is increasing. Pediatr Ann. 2003;32:685–691. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-20031001-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steyaert JG, De la Marche W. What’s new in autism? Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:1091–1101. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0764-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kılınçaslan A, Tutkunkardaş MD, Mukaddes NM. Complementary and alternative treatments of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Neuropsychiatry. 2011;48:94–102. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanson E, Kalish LA, Bunce E, Cuntis C, McDaniel S, Ware j, Petry J. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:628–636. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrington JW, Rosen L, Garnecho A, Patrick PA. Parental perceptions and use of complementary and alternative medicine practices for children with autistic spectrum disorders in private practice. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(Suppl 2):156–161. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604002-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong HH, Smith RG. Patterns of complementary and alternative medical therapy use in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:901–909. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liptak GS, Orlando M, Yingling JT, Theurer-Kaufman KL, Malay DP, Tompkins LA, Flynn JR. Satisfaction with primary health care received by families of children with developmental disabilities. J Pediatr Health Care. 2006;20:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Committee on Children with Disabilities. American Academy of Pediatrics. Counseling families who choose complementary and alternative medicine for their child with chronic illness or disability. Pediatrics. 2001;107:598–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilgiç A, Uslu R, Kartal OÖ. Comparison of toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay based on Diagnosis Classification: 0–3 Revised. Archives of Neuropsychiatry. 2011;48:188–194. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petry JJ, Finkel R. Spirituality and choice of health care practitioner. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10:939–945. doi: 10.1089/acm.2004.10.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong WC. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in autism spectrum disorder (ASD): comparison of Chinese and western culture (Part A) J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:454–463. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Şenel HG. Parents’ views and experiences about complementary and alternative medicine treatments for their children with autistic spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:494–503. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0891-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Task Force on DSM-IV. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy SE, Mandell DS, Merhar S, Ittenbach RF, Pinto-Martin JA. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among children recently diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24:418–423. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nickel R. Controversial therapies for young children with developmental disabilities. Infants Young Children. 1996;8:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Referans to non-medical persons of the patients treated in psychiatry clinic of Erzurum Numune Hospital, for their mental disorders. Düşünen Adam: Psikiyatri ve Nörolojik Bilimler Dergisi. 1992;5:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green VA, Pituch KA, Itchon J, Choi A, O’Reilly M, Sigafoos J. Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autistic. Res Dev Disabil. 2006;27:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akins RS, Angkustsiri K, Hansen RL. Complementary and alternative medicine in autism: An evidence-based approach to negotiating safe and efficacious interventions with families. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sibinga EM, Ottolini MC, Duggan AK, Wilson MH. Parent-pediatrician communication about complementary and alternative medicine use for children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2004;43:367–373. doi: 10.1177/000992280404300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MH, Kemper KJ. Complementary therapies in pediatrics: a legal perspective. Pediatrics. 2005;115:774–780. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy SE, Hyman SL. Novel treatments for autistic spectrum disorders. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11:131–142. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]