Abstract

Aging causes major alterations of all components of the neurovascular unit and compromises brain blood supply. Here, we tested how aging affects vascular reactivity in basilar arteries from young (<10 weeks; y-BA), old (>22 months; o-BA) and old (>22 months) heterozygous MYPT1-T-696A/+ knock-in mice. In isometrically mounted o-BA, media thickness was increased by ∼10% while the passive length tension relations were not altered. Endothelial denudation or pan-NOS inhibition (100 µmol/L L-NAME) increased the basal tone by 11% in y-BA and 23% in o-BA, while inhibition of nNOS (1 µmol/L L-NPA) induced ∼10% increase in both ages. eNOS expression was ∼2-fold higher in o-BA. In o-BA, U46619-induced force was augmented (pEC50 ∼6.9 vs. pEC50 ∼6.5) while responsiveness to DEA-NONOate, electrical field stimulation or nicotine was decreased. Basal phosphorylation of MLC20-S19 and MYPT1-T-853 was higher in o-BA and was reversed by apocynin. Furthermore, permeabilized o-BA showed enhanced Ca2+-sensitivity. Old T-696A/+ BA displayed a reduced phosphorylation of MYPT1-T696 and MLC20, a lower basal tone in response to L-NAME and a reduced eNOS expression. The results indicate that the vascular hypercontractility found in o-BA is mediated by inhibition of MLCP and is partially compensated by an upregulation of endothelial NO release.

Keywords: Aging, basilar artery, vascular hypercontractility, neurovascular uncoupling, MYPT1-T696 gene mutation, actin dynamics

Introduction

Aging causes major alterations of all components of the neurovascular unit, i.e. the endothelium, vascular smooth muscle and perivascular cells which include neurons and astrocytes, depending on the size of the blood vessels.1 Several investigations implicated an increased activity of NAD(P)H oxidases (NOX) as a major cause of aging-induced alterations of cerebral blood flow.2–4 A large body of evidence indicated that such alterations are associated with an increased risk of transient ischemic attacks, ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes, and, especially if the microcirculation is involved, dementia.5 While at the level of the microcirculation blood flow is adapted to local metabolic demand, large cerebral blood vessels are important determinants of downstream local microvascular pressure and perfusion.6 Thus, any dysfunction of the feed arteries will impede microvasculature perfusion. Most studies on brain perfusion focused on the vasculature that supplies the neocortex.2–4 The basilar artery (BA), which supplies blood to the posterior circulation, i.e. the large vascular networks of the brainstem, the occipital lobes, part of the thalami and cerebellum, brain regions of vital importance,7 appears to be understudied both clinically8 and experimentally.9 The territory of the posterior circulation is affected by occlusions in about 20% of all ischemic strokes10 and transient ischemic attacks.8 An important clinical aspect regarding the posterior circulation is its flow plasticity, which allows bidirectional flow through the numerous collaterals of this vessel network9, rendering the clinical symptoms highly diverse.11 Despite its rarity (under 5% of all cases) and the recent therapeutic advances, acute flow impairment in the BA territory has still devastating consequences for the patients, with calculated 80%–90% mortality or disability rates,12,13 and as yet there are no clear evidence-based therapeutic guidelines. A novel experimental therapeutic approach in animal models is the stimulation of the sphenopalatine ganglion14 which leads to vasodilation, likely by releasing NO from perivascular neurons.15,16

Histological and electrophysiological studies have demonstrated that cerebral arteries are innervated predominantly by preganglionic neurons originating from the superior salivatory nucleus, which via the great petrosal nerve and sphenopalatine ganglion, and after switching to small postganglionic neurons, innervate cerebral arteries and intracranial internal carotid arteries, as well as the vasculature of the lacrimal and nasal glands.17 These neurons release NO and peptides like substance P, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and calcitonin gene-related peptide. Others display cholinesterase expression.17 Transmural electrical (2–20 Hz) or chemical (nicotine) stimulation relax different cerebral vessels in a variety of species in vitro (as reviewed in Toda and Okamura18). The responses were selectively blocked by hexamethonium, tetrodotoxin and NOS inhibitors, suggesting the involvement of small perivascular nitrergic neurons.19–24 The contribution of peptide neurotransmitters and of cholinergic nerves to neuronally mediated vasodilation is still unclear.23

Pharmacological studies revealed that about two-thirds of NO originated from perivascular nerves and one-third from non-neuronal tissues, mainly the endothelium, a stoichiometry that likely also applies to humans.17 This stoichiometry of constitutive NO-production seems to be changed with senescence. For example, the vasodilatory response of brain vasculature to systemic application of nicotine is blunted in aged rats.25 Furthermore, NO liberated from the endothelium, but not from nNOS or iNOS, appears to be the predominant protective mechanism against cerebral ischemia and hypoperfusion in aged rats.26 To date, little is known how old age affects these responses in basilar arteries, especially in the mouse, which is widely used as small animal model for cerebral vascular dysfunction.27,28 Also, little is known how old age (∼2 years) of mice affects basal NO release, a major regulator of vascular tone and, hence, cerebral blood flow29 as most investigations studying aging effects use only one-year-old animals.2,4 However, old age (>20 months) changed the reactivity compared to one-year-old animals.3,30

Here, we investigated vascular reactivity of BA in 22–24 months old mice, which are close to the end of their life, and, hence are more representative than one-year-old mice of senescent humans. The goals of our study were (i) to investigate whether there is evidence for neuronally released NO by using electrical field stimulation (EFS) and inhibitors of eNOS and nNOS and whether this is affected by aging; (ii) we have previously shown31 that in young rat vessels, the responsiveness to the thromboxane analogue U46619 is blunted in a NO-dependent manner. Because of the known endothelial dysfunction in aging, we hypothesized that aged vessels are hyperreactive to U46619, (iii) that the augmented basal tone previously described in aged pressurized rat middle cerebral artery30 involves inhibition of MLCP mediated by phosphorylation of its regulatory subunit, MYPT1 and (iv) that the aging-induced changes in regulation of vascular tone are amenable to apocynin.

Materials and methods

The mice were kept in the Animal Facility of the Medical Faculty of the University of Cologne according to the European Union Recommendation 2007/526/EG. All mouse experiments were approved by the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, North Rhine Westphalia (AZ8.87-50.10.47.09.186; AZ84-02.05.20.12.147; AZ8.87-50.10.31.08.235) and carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the European Commission (Directive 2010/63/EU) and of the German Animal Welfare Act (TierSchG). This report followed the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal experiments.

Mechanical experiments

Dissection and mounting of mouse basilar arteries

Male C57/BL6NCr mice were sacrificed after isoflurane narcosis by cervical dislocation. The basilar arteries of 8–10 week (y-BA) and 22–24 months old mice (o-BA) were isolated at room temperature in physiological salt solution (PSS) containing in mmol/L: NaCl 119, KCl 4.69, MgSO4 1.17, KH2PO4 1.18, NaHCO3 25, EDTA 0.03, glucose 5.5, CaCl2 0.16 aerated with carbogen. Then, 1.8–2.0 mm long-ring segments were mounted with 25 µm tungsten wires in a wire-myograph (model 300A or 610A, DMT myotechnology, Denmark). Following mounting, CaCl2 was increased to 1.6 mmol/L, and temperature was raised to 37℃. For investigations without functional endothelium, arteries were mechanically de-endothelialized using mouse whiskers. After equilibration, the arteries were stretched to their optimal diameter using the so-called normalization protocol according to the manufacture's instruction and the DMT software (cf. also Mulvany and Halpern32, Supplementary Figure 1). Initial force between groups immediately (2 min) after the normalization procedure was not different (2.2 ± 0.08 mN in n = 8 y-BA with intact endothelium vs. 2.2 ± 0.1 mN in n = 5 de-endothelialized preparations; 2.2 ± 0.07 mN in n = 8 o-BA with intact endothelium vs. 2.5 ± 0.1 mN in n = 5 de-endothelialized preparations, all p < 0.5). This force converts into a calculated pressure of ∼6.5 kPa, which corresponds to the in vivo carotid artery blood pressure.33

Experimental protocols

U46619 dose-response curves

The vessels were activated by cumulatively adding U46619 to the organ bath (concentration range 0.01 to 3 µmol/L). To test for NO-mediated modulation of contractile activity, a second dose-response curve was obtained after pre-incubation for 20 min with L-NAME (100 µmol/L) or L-NPA (1 µmol/L) or vehicle (H2O; time-matched controls). In some experiments, the arteries were incubated with the inhibitors immediately after the normalization procedure to test for development of basal tone. Basal tone was always expressed in % of the subsequent force elicited by maximal concentration of U46619.

Transmural EFS

The vessels were electrically stimulated with a home build device via two platinum wires placed in parallel to the long axis of the arteries with unipolar rectangular 0.1 ms pulses. After determining the voltage necessary for maximal relaxation (Supplementary Figure 6), frequency response curves with supramaximal (30 V, train duration 3 s) and submaximal (12.5–17.5 V, train duration 20 s) stimulation were obtained. Submaximal EFS was chosen to analyze the NOS dependence of the initial fast phase (cf. Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figure 6). Relaxation by EFS or nicotine was expressed as % force of the submaximal U46619-induced force, i.e. (force(EFS)/U46619-induced force × 100).

Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin permeabilized vessels

Arteries were permeabilized before mounting on the myograph as described.34 The mounted preparations were stretched to their optimal lumen diameter. Submaximal contractions were elicited by pCa 6.1 for 15 min followed by maximal activation with pCa 4.3 (cf. Supplements).

Determination of media thickness

The media thickness of isometrically mounted and pre-stretched preparations (endothelium intact) was estimated from confocal Z-stack images of Alexa Fluor®555 phalloidin-stained vessels as detailed in the Supplementary Information.

eNOS and nNOS expression

BAs were isolated as for mechanical experiments and shock frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted with Maxwell 16 LEV simplyRNA kit (Promega, Madison, WI), and the amount of RNA was quantified. RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA (cDNA-kit, QuantiTec, QIAGEN). The real-time PCR was carried out with a GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI) and was run in a thermocycler (StepOnePlus™ real-time PCR System, Applied Biosystems™). Data analysis was achieved by StepOne Software v2.3.

Protein phosphorylation

Protein phosphorylation was determined by western blot analysis34 (cf. Supplementary Methods). In brief, endothelium-intact vessels were mounted on a 25-µm tungsten wire, incubated for 15 min either with vehicle (0.2% DMSO) or 600 µmol/L apocynin, then shock frozen and processed for western blotting. Primary antibodies were directed against phospho-MLC20Ser19, phospho-MYPT1T-853 or phospho-MYPT1T-696. Detection and quantification of immunoreactive signals were performed using the Odyssey system (LiCor).

G-actin content

G-actin content was determined using “G-actin/F-actin In Vivo Assay Kit” (Cytoskeleton/Biomol). Briefly, BAs from both age groups (∼4 mm long) were isolated as described above, shock frozen in liquid nitrogen, and further processed according to the manufacturer's instructions (cf. Supplementary Methods).

Gene targeting of MYPT1

A point mutation was introduced into the regulatory subunit of MYPT1 by gene targeting (knock-in) in the mouse replacing the inhibitory phosphorylation site T-696 by the non-phosphorylatable alanine (see Supplementary Methods for details). No homozygous offspring were obtained; however, heterozygous offspring were viable with no overt phenotype and reached old age. A detailed description of this mouse model will be published elsewhere.

Statistics

Data were summarized as mean and standard error (SEM). Figure legends report the number of animals investigated per group. Depending on the number of groups and the experimental design groups were compared using two-sample t-test for independent samples or one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post hoc tests (Tukey, Bonferroni or Dunnett, respectively). In case of 2 × 2 factorial designs, main effects as well as interactions between the factors were investigated using two-way ANOVA. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Version 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) and IBM-SPSS Statistics Version 23 (Armok, NY) were used to perform statistical analyses.

Results

Modulation of U46619-induced and basal tone by nNOS inhibition in young and old murine basilar arteries

Passive force following the normalization protocol (∼2.2 mN, cf. Methods) and the slope of the pressure-diameter relation were not different between groups indicating similar passive properties (Supplementary Figure 1). However, U46619-induced force was significantly blunted in young vessels from ∼2-month-old mice compared to 22–24 months old mice (Figure 1). Thus, Fmax was 1.8 ± 0.2 mN (n = 15) in y-BA compared to 3.5 ± 0.4 mN in o-BA (n = 10, p < 0.001), and pEC50 was 6.5 ± 0.1 in y-BA versus 6.9 ± 0.1 in o-BA (p < 0.01, Figure 1, Table1). The difference in Fmax remained when wall tension and wall stress were calculated taking into account the differences in segment length and the ∼10% thicker media in o-BA (cf. Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Modulation of U46619-induced contraction in young and old murine basilar arteries by NOS. (a, b): Examples of force traces with contractile responses to the thromboxane analogue U46619 (0.01–3 µmol/L) in y-BA (a) and o-BA (b) prior to and during NOS inhibition. (c, d): Dose-response curves for the effect of U46619 on force in y-BA (c) and o-BA (d): in the absence of inhibitor (open symbols; n = 15 for y-BA, n = 10 for o-BA), with 100 µmol/L pan-NOS inhibitor L-NAME (filled circles; n = 9 for y-BA, n = 5 for o-BA), with 1 µmol/L nNOS inhibitor L-NPA (filled triangles; n = 7 for y-BA, n = 5 for o-BA). Open diamonds in (c) and (d) depict the effect of U46619 in the time-matched controls from both age groups (n = 7 for y-BA, n = 4 for o-BA). The % Force in the ordinates in (c) and (d) is a normalization to the force elicited by 3 µmol/L U46619 in the absence of inhibitor. Inserts in (c) and (d) display absolute forces, elicited by 3 µmol/L U46619 without inhibitor (bars “1”), with 100 µmol/L NAME (bars “2”), with 1 µmol/L L-NPA (bars “3”). (e): Endothelium-denuded (“Endo-”) o-BA shows a continuous tone increase after mounting (n = 5), while this is not seen in denuded y-BA, nor in vessels with intact endothelium (“Endo+”). (f): Comparison of the eNOS and nNOS expression in y-BA and o-BA. The ordinate shows the fold change in the quotient of mRNA levels for eNOS/GAPDH (left) and nNOS/GAPDH (right) relative to the reference sample. As reference samples for eNOS, the young mouse tail artery was used (n = 5) and for nNOS, the young mouse fundus (n = 5). Error bars represent ±SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Pre-incubation with L-NAME significantly increased Fmax and pEC50 in y-BA versus time control (Figure 1 and Table 1) as has been found previously in cerebral vessels from young rats.31 In contrast, the L-NAME-induced leftward shift of the dose-response relation was smaller in o-BA (Table 1). As L-NAME inhibits both eNOS and nNOS, the experiments were repeated in the presence of L-NPA (1 µmol/L), which at this concentration is a rather specific inhibitor of nNOS.32 As depicted in Figure 1, L-NPA shifted the U46619 dose-response curves in y-BA by a similar extent as L-NAME (cf. Table1). No significant changes in the concentration-response curves were observed in time-matched controls (Table 1). The ETA receptor antagonist, BQ123 had no significant effect on U46619 dose-response curves with and without L-NAME (cf. Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 2) indicating that the increased responsiveness to U46619 after inhibition of NOS by L-NAME was not due to endothelin release.

Table 1.

Dose-response curves with U46619-induced contraction in y-BA and o-BA in the absence (controls, time controls) and presence of inhibitors of NOS, ETA receptor antagonist and apocynin.

| Age group and type of pharmacologic treatment | Fmax (mN) | pEC50 | ΔpEC50 | Basal tone (% Fmax) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | |||||

| Controls Time controls 100 µmol/L L-NAME 1 µmol/L L-NPA 1.5 µmol/L BQ123 1.5 µmol/L BQ123+ 100 µmol/L L-NAME | 1.8 ± 0.2 1.3 ± 0.4 3.2 ± 0.3** 3.0 ± 0.5* 2.3 ± 0.5 3.8 ± 0.4 | 6.5 ± 0.1 6.6 ± 0.1** 7.2 ± 0.1 7.0 ± 0.05 6.5 ± 0.1 7.4 ± 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.06 0.67 ± 0.1** 0.53 ± 0.08* 0.87 ± 0.2 | 11.0 ± 2.2 9.0 ± 2.1 0 15.8 ± 2.9 | 15 7 9 8 4 4 |

| Old | |||||

| Controls Time controls 100 µmol/L L-NAME 1 µmol/L L-NPA 1.5 µmol/L BQ123 1.5 µmol/L BQ123+ 100 µmol/L L-NAME 600 µmol/L Apocynin 600 µmol/L Apocynin+ 100 µmol/L L-NAME | 3.5 ± 0.4§§§ 2.5 ± 0.8 4.2 ± 0.4 3.9 ± 0.9 2.8 ± 0.2 3.5 ± 0.3 4.1 ± 0.5 4.8 ± 1.0 | 6.9 ± 0.1** 6.9 ± 0.02 7.23 ± 0.05 7.14 ± 0.2 6.9 ± 0.2 7.5 ± 0.1 7.1 ± 0.2 7.23 ± 0.2 | −0.04 ± 0.09 0.27 ± 0.1* 0.3 ± 0.1 0.59 ± 0.1 0.18 ± 0.1 | 23.0 ± 1.1* 8.9 ± 3.7 0.17 ± 2.9 29.1 ± 6.0 −3.8 ± 1.1 14.8 ± 5.7 | 10 4 5 5 4 4 3 3 |

Control refers to first dose-response relation, time control (t.c.) to second dose-response relation in the absence of inhibitors.

Fmax: Young: **t.c. vs. L-NAME p < 0.01; *t.c. vs. L-NPA p < 0.05; L-NAME vs. L-NPA or vs. BQ123+L-NAME p> 0.05; Old: §§§Controls (old) vs. Controls (young) p < 0.001; Fmax (old) no significant difference between groups (p > 0.05).

pEC50: Young: **t.c. vs. L-NAME or L-NPA p < 0.01; L-NAME vs. L-NPA or vs. BQ123+L-NAME p > 0.05; Old: pEC50 (old) no significant difference between groups (p > 0.05); pEC50 (old) vs. pEC50 (young) p < 0.01.

ΔpEC50: Young: **t.c. vs. L-NAME p < 0.01; *t.c. vs. L-NPA p < 0.05; L-NAME vs. L-NPA or vs. BQ123+L-NAME p > 0.05; Old: *L-NAME (old) vs. L-NAME (young) p < 0.05; L-NAME (old) vs. L-NPA (old); p > 0.05; L-NAME (old) vs. BQ123+L-NAME (old) p > 0.05; L-NAME (old) vs apocynin + L-NAME (old); p > 0.05.

Basal tone: *L-NAME (old) vs. L-NAME (young) p < 0.05.

Both NOS inhibitors also raised basal tone, whereby L-NPA appeared to be equally effective as L-NAME in y-BA and o-BA (Table 1, p = 0.45). In contrast, L-NAME induced a significantly larger basal tone increase in aged compared to y-BA (p < 0.05). Incubation with BQ123 did not affect the L-NAME-induced raise in basal tone (see Table1, Supplementary Figure 2). Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that in y-BA, NO was liberated from non-endothelial rather than endothelial sources, whereas in o-BA, endothelial-derived NO significantly contributed to maintenance of basal tone. This notion is supported by the finding that basal tone gradually increased in mechanically de-endothelialized preparations after the normalization procedure (Figure 1(e)). Interestingly, inhibition of L-NPA was additive to mechanical denudation in y-BA (Supplementary Figure 3).

Consistent with the mechanical observations, we found a ∼2-fold higher eNOS expression in o-BA (n = 7) compared to y-BA (p < 0.05; n = 7; Figure 1(f)). No significant increase in nNOS-mRNA (p > 0.05, n = 5) was observed. We are aware that the comparison was underpowered due to the low n-number because of the limited availability of aged mice. Of note, eNOS but not nNOS mRNA could be detected in peripheral arteries while expression of nNOS but not of eNOS was high in gastric fundus as expected. This indicates differences in the source of NO (endothelial versus non-endothelial) between cerebral and peripheral arteries.

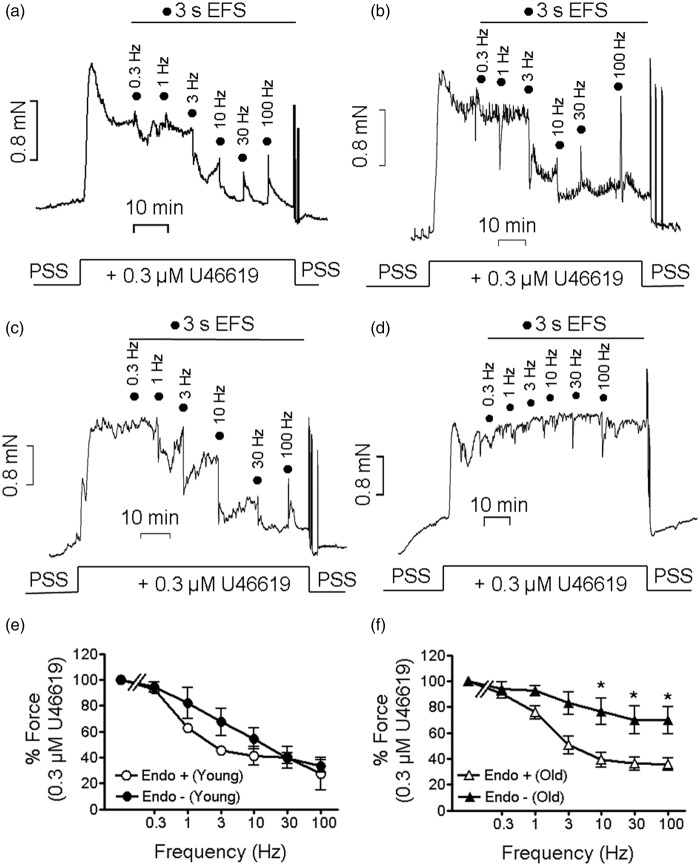

Relaxation of U46619 pre-contracted arteries by transmural EFS: Effect of apocynin

The results presented in Figure 1 indicated that non-endothelial NO release modulates resting and U46619 elicited contraction. Putative sources are besides endothelial and adventitial cells,35 perivascular neurons.36 As EFS has been shown to release NO from such neurons,18 we next tested whether transmural EFS relaxed U46619 pre-contracted BA in a NO-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 2, EFS (supramaximal voltage) relaxed both y-BA and o-BA in a frequency-dependent manner similar to a previous report in rat brain arteries.37 Relaxation was biphasic consisting of an initial fast and subsequent slow phase and was maximal at 10 Hz (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 6) while 30 and 100 Hz induced a transient contraction. In endothelium-intact preparations, EFS-induced relaxation at 10 Hz was similar in both age groups (p > 0.05, Figure 2(e) and (f)). Endothelial denudation attenuated EFS-induced relaxation in o-BA (Figure 2(f)) but not in y-BA (Figure 2(e)). This indicates that in aged but not in y-BA, endothelium modulates EFS-induced relaxation.

Figure 2.

Attenuated relaxation of de-endothelized o-BA upon supramaximal EFS. (a to d): Examples of the effect of different EFS frequencies (0.1 ms pulse duration, 30 V, 3 s trains) on 0.3 µmol/L U46619 force. (a, b): y-BA (a) and o-BA (b) with intact endothelium. (c, d): Mechanically denuded y-BA (c) and o-BA (d). N = 4–8 for a–d. (e, f): Dependency of the EFS-induced force decline on stimulation frequency in y-BA (e) and o-BA (f) with intact endothelium (open symbols, “Endo+”) or upon de-endothelization (filled symbols, “Endo-”). Ordinates in (e) and (f); normalized force to the value elicited by 0.03 µmol/L U46619 in the respective age group; *p < 0.05.

EFS: electrical field stimulation; PSS: physiological salt solution.

To further characterize EFS-induced relaxation, endothelium-denuded BAs were subjected to EFS with submaximal voltage (12.5–17.5 V) which triggered only the initial fast relaxation (Figure 3(a) and (b); Supplementary Figure 6). At 10 Hz, EFS-induced relaxation was 11.8 ± 2% in o-BA (n = 5), which was significantly different from that induced by submaximal voltage in y-BA (25 ± 2%, n = 8, p < 0.05). To test that EFS-induced relaxation involves neuronally released NO, young vessels were pre-incubated with TTX (1 or 10µmol/L) and L-NPA (3µmol/L) before eliciting a submaximal contraction with U46619. In these endothelial-denuded preparations, TTX and L-NPA had no significant effect on submaximal contraction in y-BA (force in % Fmax: time control (n = 6) 79 ± 4, 10 µmol/L TTX (n = 8), 72 ± 3, L-NPA (n = 6) 85 ± 5, all >0.05) and in o-BA (force in % Fmax: time control (n = 5) 89 ± 3, TTX (n = 3) 82 ± 11, L-NPA (n = 3) 100 ± 6, all >0.05). Relaxation in y-BA was attenuated by TTX (1 or 10 µmol/L) or L-NPA (3 µmol/L, Figure 3(c), cf. Supplementary Figure 5 for original force tracings) indicating that relaxation involves neuronally released NO. EFS-induced relaxation was not affected by either compound in o-BA (Figure 3(d)). At the end of most experiments, the preparations were additionally challenged with nicotine (100 µmol/L). The amplitude of nicotine-induced relaxation was similar to that induced by EFS (10 Hz) in y-BA consistent with other reports16 and was significantly (p < 0.001) smaller in o-BA (Figure 4(a)). In y-BA, nicotine-induced relaxation was significantly attenuated by TTX or L-NPA (p < 0.05, Figure 4(a)). We hypothesized that the attenuated relaxation of o-BA might be due to higher pre-contraction (force in % Fmax: time control y-BA 79 ± 4 (n = 6) versus o-BA 89 ± 3 (n = 5)). Therefore, we reduced U46619 to 0.1 µmol/L (denoted as normalized time control in Figure 3(d)) which lowered submaximal force to 68 ± 4% compared to 89 ± 3% at 0.3 µmol/L U46619, and which was not different from the time control in y-BA (p > 0.05). However, lowering of U46619 concentration did not restore EFS- or nicotine-induced relaxation.

Figure 3.

Aging attenuated submaximal EFS-induced relaxation of de-endothelized basilar arteries. Representative force traces from young (a) and old (b) basilar arteries pre-constricted with 0.3 (a) or 0.1 µmol/L (b) U46619. Summarized data of the relaxation induced by submaximal EFS (12.5–17.5 V, 0.1 ms pulses, 3 s trains) in young (c) and old (d) basilar arteries at control conditions (without inhibitors; n = 8 young, n = 5 old animals) and after pre-incubation with TTX (1 or 10 µmol/L, n = 5–8 young, n = 3 old animals) or L-NPA (3 µmol/L, n = 6 young and n = 3 old animals) and time-matched controls (n = 6–4). Data were expressed in percent of the force elicited by 0.3 µmol/L U46619 prior exposure to EFS and expressed as % force.

Figure 4.

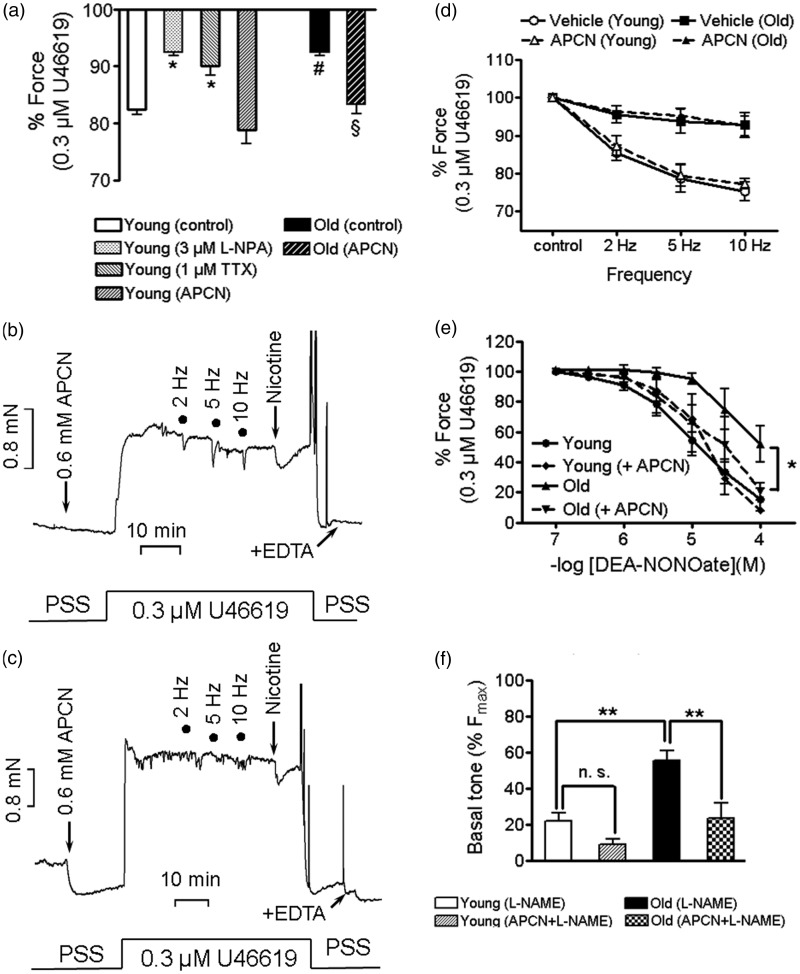

Apocynin (APCN) pre-treatment restored the impaired NO-responsiveness and the chemically but not electrically induced relaxation, and lowers basal tone of aged murine basilar arteries. (a): Effect of 100 µmol/L nicotine alone (control, n = 9 y-BA, n = 8 o-BA), and in the presence of 1 µmol/L TTX (n = 3 y-BA), 3 µmol/L L-NPA (n = 6 y-BA) and 600 µmol/L apocynin (n = 7 young and n = 4 old arteries). Force is expressed in % of 0.3 µmol/L U46619-induced contraction prior to nicotine application; *p < 0.05 TTX or L-NPA vs y-BA (control); #p < 0.001, y-BA (control) vs. o-BA (control); §p < 0.01 o-BA (control) vs o-BA with (APCN); p = 0.15 young (controls) vs. young (APCN). (b, c): Representative force traces displaying the effect of APCN on EFS and on nicotine-induced relaxation in y-BA (b) and o-BA (c). (d): Summary of the effect of submaximal EFS (12.5–17.5 V, 0.1 ms pulses, 3 s trains) in young and old BAs (n = 4). (e): Dose-response relation of DEA-NONOate-induced relaxation in y-BA and o-BA in the absence (n = 6 young, n = 5 old) and presence (n = 3 young, n = 5 old) of APCN. Before stimulation with 0.3 µmol/L U46619, arteries were pre-incubated for 15 min in 600 µmol/L APCN and were then additionally pre-treated with 100 µmol/L L-NAME. Force is expressed as percent of the force elicited by 0.3 µmol/L U46619, prior to application of DEA-NONOate, symbols represent mean ±SEM, *: p < 0.05 y-BA vs o-BA. There was no significant difference between the other groups (Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test). (f): Basal tone of y-BA and o-BA, pre-incubated with 100 µmol/L L-NAME (n = 3 young and n = 5 old) or with 600 µmol/L APCN and 100 µmol/L L-NAME (n = 5 young and old BAs). **: p < 0.01, n.s. not significantly different (p = 0.12). Force is expressed in percent of U46619-induced contraction at 3 µmol/L (Fmax). Error bars represent (±) SEM.

We then hypothesized that the attenuated relaxation in o-BA was due to ROS generation and therefore tested whether apocynin would restore relaxation. Apocynin significantly enhanced nicotine-induced relaxation in o-BA (p < 0.01; Figure 4(a) and (c)) to levels that were not significantly different from y-BA with and without apocynin. Apocynin did not enhance the nicotine-induced relaxation in young arteries (p = 0.14). It had no effect on U46619 dose-response relation in o-BA (Table 1) and on EFS-induced relaxation in both age groups (Figure 4(b) to (d)).

Effect of apocynin on NO-mediated relaxation in aged arteries

The attenuated relaxation may be caused by impaired release of NO or by attenuated responsiveness of vascular smooth muscle cells to NO. To distinguish between these possibilities, endothelium-intact BAs pre-constricted with U46619 (0.3 µmol/L) in the presence of L-NAME were incubated with increasing concentrations of DEA-NONOate. The dose-response curve to DEA-NONOate was shifted to the right towards higher concentrations in old compared to y-BA (Figure 4(e), p = 0.014). To test whether apocynin restored DEA-NONOate sensitivity, y-BA and o-BA were pre-incubated with apocynin in the presence of L-NAME (15 min alone and another 20 min together with L-NAME) followed by stimulation with 0.3 µmol/L U46619 in the continuous presence of the compounds. Apocynin had no effect on submaximal tone in both age groups (Supplementary Figure 4, p > 0.05). Apocynin had no effect on the dose-response curve to DEA-NONOate in y-BA but in o-BA it was shifted to the left towards that obtained in y-BA (Figure 4(e)). Thus, the response to 100 µmol/L DEA-NONOate was significantly (p < 0.05) smaller in o-BA compared to y-BA in the absence but not in the presence of apocynin. We then tested whether apocynin prevented the L-NAME-induced increase in basal tone in o-BA (Figure 4(f)). As depicted in Figure 4(f), L-NAME-induced force in the presence of apocynin in o-BA was comparable to that in y-BA in the absence of apocynin (p >0.05). Different from the experiments shown in Figure 1, the vessels were not stimulated with U46619 prior to incubation with L-NAME which may account for the larger increase in tone.

Aging is associated with increased basal MLC20 and MYPT1 phosphorylation and increased F-actin content

We next investigated whether there was a difference under resting conditions in MLC20 phosphorylation at S-19, the site that is responsible for activation of myosin (Figure 5(a)). As depicted in Figure 5(b), resting MLC20 phosphorylation was significantly higher in o-BA compared to y-BA (p < 0.01), and apocynin decreased MLC20 in o-BA significantly (p < 0.01) to levels that were not different from those in y-BA (p > 0.05). Further phosphorylation of the regulatory subunit of myosin phosphatase, MYPT1 at T-853 was significantly higher in old compared to y-BA (Figure 5(b)). In contrast, phosphorylation of T-696 was high in both age groups (Figure 5(b)). Apocynin significantly decreased phosphorylation of T-853 in both ages and of T-696 in y-BA. Dephosphorylation of T-696 by apocynin in o-BA did not reach the level of significance (p = 0.048). Taken together, these results suggest that MLCP is inhibited in o-BA. In keeping with this notion, basal Ca2+-sensitivity, i.e. in the absence of Ca2+-sensitizating agonists, was increased in α-toxin permeabilized o-BA (Figure 5(c)). Moreover, the increased T-853 phosphorylation suggests increased ROK activity in o-BA and requires to be tested further in the future. Augmented ROK signaling has been shown to reduce G-actin content in cerebral arteries.38 In line with this we found that fluorescence intensity of Alexa Fluor® 555-phalloidin was enhanced in confocal images of o-BA, indicating an increased F-actin fraction (Figure 5(d)). This notion was corroborated by biochemical analysis of the G-actin to F-actin ratio which was significantly lower in o-BA (Figure 5(e) and (f)).

Figure 5.

Aging increased basal phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain (pMLC20S-19) and reduced the G-actin content in murine basilar arteries. Representative western blots (a) and densitometric analysis (b) of pMLC20S-19 and of MYPT1 phosphorylation at T-853 and T-696 in vessels from both age groups, treated with vehicle (0.2% DMSO; time controls) or with 600 µmol/L apocynin (APCN). As loading controls, the membranes were incubated with antibodies against β-actin, GAPDH or MYPT1total. In (b), the ordinate represents phosphorylation as ratio of the immunoreactivities of pMLC20S-19/β-actin (n = 4) or pMYPT1T-853/MYPT1total (n = 4) or MYPT1T-696/MYPT1total (n = 3). (c): Steady state submaximal (pCa 6.1) Ca2+-induced contraction of young (n = 7) and old (n = 9) α-toxin permeabilized murine basilar arteries. Force is expressed as % of force at pCa = 4.3. (d): Representative confocal images from y-BA and o-BA co-stained with Alexa Fluor®555-phalloidin and Hoechst 33342 (a total of six arteries (six animals) per group were used for co-staining). Prior to imaging, the preparations were isometrically mounted and stretched as described in the Methods. (e): Representative western blots of centrifuged vessel preparations with the supernatant (S) containing G-actin and the pellet (P) containing F-actin (see Methods for details on preparation). The upper part of the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. Myosin heavy chain (MHC) is detected in the pellet only. Actin and GAPDH were detected with respective antibodies. (f): Densitometric analysis showing the G-actin-to-F-actin ratio (left) and the G-actin-to-GAPDH ratio in y-BA (white bars) and o-BA (black bars). Analysis included n = 5 arterial segments per age group. Error bars represent ±SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Role of inhibitory MYPT1-T-696 phosphorylation in aged arteries

The impact of T-696 phosphorylation on basal tone in o-BA was tested in heterozygous aged T-696A/+ knock-in mice, in which T-696 was exchanged by alanine, which cannot be phosphorylated. This resulted in a ∼40% reduction in phosphorylation of T-696 in the mutant compared to WT mice. MLC20 phosphorylation was reduced to that in young mice (Figure 6(b) and cf. Figure 5(b)). Basal tone in the presence of L-NAME was 14.6 ± 3.9% in mutant o-BA compared to 23.0 ± 1.2% (n = 5, p < 0.05). It was comparable to the values in WT y-BA (11.0 ± 2.1; p = 0.35; n = 9; Figure 6(c)). Interestingly, expression of eNOS was reduced in old mutant compared to old WT mice (p < 0.05, Figure 6(d)).

Figure 6.

Phosphorylation of MLC20 and MYPT1T-696, basal tone and eNOS expression in o-BA of MYPT1T696A/+-mice. (a, b): Representative western blots and densitometric quantification via calculation of the intensity ratios pMYPT1T-696 to MYPTtotal, pMLC20S-19 to β-actin and MYPTtotal to MHC, in o-BA from control animals (WT) and from MYPT1T696A/+-mice (n = 5 animals per group). The MYPTtotal-to-MHC ratio served as a measure for MYPT1 expression in WT and MYPT1T696A/+ animals (note that for MHC, the Coomassie stain signal intensity was used). (c): Comparison of the basal tone increase in the presence of L-NAME in y-BA (n = 9) and o-BA (n = 5) from WT animals, and in o-BA from MYPT1T696A/+-mice (n = 5). (d): eNOS expression, on the mRNA level, in y-BA (n = 8) and o-BA (n = 7) from WT animals, and in o-BA from MYPT1T696A/+-mice (n = 4; the data for y-BA and o-BA from WT arteries are replotted from Figure 1(f)). Relative eNOS mRNA levels are expressed as normalizations to the y-BA fold change value. Error bars represent ±SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n.s.: not significantly different.

MHC: myosin heavy chain.

Discussion

The major finding of this work is that in mouse BA, aging shifted both basal and stimulated NO release from predominantly non-endothelial, likely neuronal, towards mainly endothelial sources. This shift correlated with a ∼2-fold upregulation of eNOS expression. Chemical inhibition or mechanical denudation of the endothelium unmasked an augmented basal smooth muscle tone in o-BA which can be ascribed to a ROS-mediated inhibition of MLCP. We provide evidence that phosphorylation of MYPT1-T-696 plays an important role in the regulation of basal tone in o-BA, and in eNOS expression to our knowledge for the first time. The resting pressure-diameter relation of endothelial-intact arteries was not different between young and o-BA, indicating that the balance between vasodilatory and vasoconstricting signaling molecules is maintained, though at higher absolute levels. Thus, virtually all components of the neurovascular unit, i.e. endothelial and smooth muscle cells as well as perivascular neurons are altered by aging.

Basal NO release in aging

It is well known that basal NO release is the major regulator of cerebral blood flow/vascular tone.29 This is supported by our results where chemical inhibition of NOS or mechanical denudation of the endothelium increased basal tone in both age groups. The novel finding is that non-endothelial sources contribute significantly to basal NO liberation in y-BA. The arguments are (i) in y-BA chemical inhibition of nNOS appeared to be more effective than endothelial denudation in raising basal tone (Figure 1(e); Table 1) and (ii) chemical inhibition of nNOS was additive to endothelial denudation and raised basal tone in y-BA up to levels observed in o-BA (Supplementary Figure 3). Our results are corroborated by the immunohistochemical detection of nNOS in endothelial and adventitial cells35 and in perivascular neurons of cerebral blood vessels.36 In o-BA, the endothelium appeared to be the more important source of basal NO release, opposing the augmented/enhanced smooth muscle tone as indicated by the similar passive force of endothelium-intact young and aged vessels (Supplementary Figure 1(d)). Interestingly, if smooth muscle tone in o-BA was lowered to that in y-BA, as it was the case in o-BA from MYPT1-T696A/+ mice, then the eNOS expression was also decreased. The elucidation of the underlying mechanism for this novel and interesting observation is currently under investigation.

The finding of a shift towards predominantly eNOS regulation of cerebral vascular tone in aged vasculature is not novel. Increased reactivity toward NOS inhibitors has been reported for aged pressurized rat middle and posterior cerebral arteries.30,39 As endothelium denudation completely eliminated aging-related differences in development of myogenic tone, authors concluded that aging was associated with down-regulation of an endothelial, NOS-insensitive, mechanism, which was compensated by upregulation of NO release from the endothelium.30 Contrary to this report, endothelial denudation did not abrogate the age-dependent differences in our experiments. Therefore, endothelial release of non-NO signaling molecules appears to be of minor functional importance in our preparation.

Stimulated NO release in aging

There is a large body of evidence that electric stimulation relaxes cerebral arteries by release of NO from perivascular nitrergic neurons (as reviewed in Toda and Okamura18). Our observations that transmural electric stimulation resulted in an endothelium-independent relaxation in y-BA, that was inhibited by L-NPA and TTX and was mimicked by nicotine, are consistent with these published results. Also, and consistent with previous reports,21 electrically and chemically (nicotine) induced relaxation was independent of an intact endothelium in y-BA. In contrast, mechanical denudation attenuated EFS-induced relaxation at supramaximal voltage. Relaxation induced with submaximal voltage or EFS was also nearly abrogated in endothelium-denuded, o-BA. Thus, it appears that nNOS efficiency is significantly reduced in aged murine BA, which is consistent with a previous report on middle cerebral arteries in spontaneous hypertensive rats.35 These authors also detected no change in nNOS immunoreactivity, which is in an agreement with our finding that nNOS expression was not increased (Figure 1(f)). Apocynin treatment did not restore the attenuated vascular response to EFS in our model, suggesting that nitrergic neurons may be lost or undergo functional silencing with advanced age, perhaps due to ROS accumulation.3 A limitation is that some of the experiments in old animals were underpowered. This was due to the limited number of aged mice and requires further studies. Nevertheless, our results indicated that there are differences in the importance of the endothelium between young and old animals. Our experiments further suggest that the lowered nNOS efficiency in o-BA was compensated by the endothelium. Electrically induced, endothelial-dependent relaxation has been reported in some but not all species, and has been suggested to be due to release of vasoactive peptides, acting on the endothelium to release NO.40 Alternatively, EFS may trigger endothelial Ca2+ influx (agonist-induced Ca2+-pulsars) followed by activation of KCa2.3 or KCa3.1 channels. The ensuing membrane hyperpolarization spreads to the vascular smooth muscle cells, leading to closure of voltage-gated Ca2+-channels and, thus, to relaxation.41–43

In agreement with our previous report,31 we found that the contractile response to the thromboxane analogue U46619 was significantly attenuated in young vessels, and that the inhibition of nNOS by L-NPA potentiated the contractile response. As ThromboxaneA2-receptors have been identified in neurons and glial cells,44 this raises the intriguing possibility that U46619, like nicotine, stimulates NO release from nitrergic neurons thereby braking its own contractile action. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that inhibition of NOS disinhibits a constrictor response. We consider this less likely because we have previously shown using cerebral arteries from young rats,31 that U46619 not only activates the RhoA/ROK calcium-sensitization pathway but in parallel also the NO/cGMP/PKG calcium-desensitization pathway thereby blunting the contractile response in a L-NAME sensitive manner. Moreover, blocking ETA receptors had no effect on U46619 dose-response relations nor on basal tone. In any case, the “autoinhibitory” effect of U46619 was significantly attenuated in o-BA and is not compensated by the upregulation of endothelial NO production. This finding could be explained by a preferential action of U46619 on perivascular neurons over endothelial cells. Taken together, aging is associated with a diminution of NO released from non-endothelial sources, likely perivascular neurons, which are compensated for by an upregulation of endothelial-derived NO.

Smooth muscle hypercontractility in aging

Endothelial denudation and chemical inhibition of NO-signaling unmasked the smooth muscle hypercontractile state in o-BA. The underlying cause for the hypercontractile state may be an increased Ca2+-sensitivity, as suggested by Geary and Buchholz30 for pressurized middle cerebral arteries and, to the best of our knowledge, directly evidenced for the first time in the present work: We used α-toxin permeabilized BA (Figure 5(c)). This procedure that short-circuits ion fluxes through the membrane allows for precise control of sarcoplasmic calcium ([Ca2+]i), while leaving Ca2+-sensitizing signaling cascades functionally intact.45 We ascribe the increased Ca2+-sensitivity to the increased basal phosphorylation of the regulatory subunit of myosin phosphatase, MYPT1 at T-853, the site that is phosphorylated by ROK, which leads to a reduction in myosin phosphatase (MLCP) activity.46 The decreased MLCP activity then leads to the observed increased MLC20 phosphorylation at a given level of Ca2+-activation, i.e. an increase in Ca2+-sensitivity of contraction.47 All these events, increased tone, phosphorylation of MLC20 at S-19 and phosphorylation of MYPT1T-853 can be reversed by functional elimination of ROS by apocynin (Figure 5(a) and (b)). Furthermore, apocynin also decreased the high levels of MYPT1-T-696 phosphorylation, especially in young animals, and restored the impaired smooth muscle sensitivity to NO in aged animals (Figure 4(e)). Lowering of NO sensitivity, paralleled by a decreased serum antioxidant capacity, has recently been reported in BA in a rat aging model, corroborating our notion that aging increased ROS production impedes NO/cGMP-mediated relaxation.48

There is a large body of evidence for redox regulation of Rho/ROK signaling which alters the inhibitory phosphorylation sites of MLCP49–51 and cerebrovascular aging is associated with a loss of antioxidant capacity,48 and peroxynitrite formation52 linked to an increased eNOS expression,52,53 as well as enhanced NADPH-derived ROS production in neurons and blood vessels.3 More recently, evidence is emerging that augmented procontractile endothelin-1/G12/13 signaling drives constriction of aged peripheral arteries.54,55 Contrary to these observations in peripheral arteries, basal tone of o-BA was not affected by the ETA receptor antagonist BQ-123. It is noteworthy that apocynin, which has been widely used as a non-specific NAPDH oxidase inhibitor,56 inhibits also ROK.57 Thus, the reduction in basal tone and in MYPT1-T853 phosphorylation might be related to the latter effect. Nevertheless, the increased MYPT1-T853 phosphorylation is evident for an augmented Rho/ROK signaling to which ROS and ET-1 signaling converge.

Interestingly, phosphorylation of MYPT1-T-696, which directly inhibits MLCP activity (reviewed in Puetz et al.47), was high in both age groups and was less affected by apocynin than T-853 phosphorylation consistent with the notion that this site is largely constitutively phosphorylated. In line with this basal MLC20 phosphorylation and L-NAME-induced tone was decreased in BA from old mice carrying the T-696A/+ mutation (Figure 6(a) to (c)). This genetic knock-in approach to replace T-696 by a non-phosphorylatable alanine resulted in a ∼40% reduction of T-696 phosphorylation in o-BA (Figure 6(a) and (b)) further supporting our interpretation that inhibition of MLCP underlies the hypercontractile state of o-BA. The impact of ROK-induced MYPT1-T-853 for regulation of smooth muscle tone has recently been questioned utilizing bladder smooth muscle from mice E 18.5 fetus carrying the T-853A mutation.58 The authors suggested that the predominant mechanism of MLCP inhibition is phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T-696 which appears to maintain a basal level of Ca2+-sensitization. Our results are consistent with this idea but indicate that vascular hypercontractility in aged WT mice additionally involves an increased MYPT1-T-853 phosphorylation. In addition, ROK is involved in increasing actin polymerization that may account for the observed increased F-actin content and contribute to the increased tone. Such an increased availability of F-actin contributing to the force generation independent of increases in MLC20, phosphorylation has been demonstrated recently in pressurized rat middle cerebral arteries.38 Thus, at present, assessment of the relative contribution of the inhibitory phosphorylation of MYPT1 at T-853 or T-696 and actin dynamics in regulation of basal tone in BA remains elusive.

Taken together, the balance between intracellular contracting and relaxing pathways is shifted in o-BA in favor of the former, which can be reversed by apocynin. In this context, it is interesting that aging-induced changes in cerebral blood flow were reversed by in vivo treatment with apocynin in a mouse model of Alzheimer,4 which could be ascribed to NOX2.2 In our study, acute application of apocynin decreased the basal tone or phosphorylation of MLC20 at S-19, but it did not normalize the contractile response to U46619, nor did it restore electrically induced relaxation. These diverging results can be reconciled if one assumed that aging was associated with loss or silencing of perivascular neurons that mediate relaxation, whereas, the basal tone was increased due to acute endothelium-derived signaling events, leading to a ROS- and/or endothelin-mediated increased activity of Rho/ROK with subsequent inhibition of myosin phosphatase in smooth muscle cells. Regardless of the precise mechanism of ROS generation, another interesting observation emerging from the present study is that endothelial denudation in o-BA did not interfere with the lowering of the basal tone by apocynin. This supports the view that non-endothelial cells may be involved in ROS generation, or support the notion that apocynin acts as a ROK inhibitor.

Clinical relevance

Although the extrapolation of our in vitro findings to the in vivo behavior of the brain vasculature has to be done with great caution, two aspects of potential clinical relevance emerged from our findings: First, our finding that transmural electric stimulation is less effective in relaxing o-BA and is counteracting the smooth muscle hypercontractility indicates that any damage of the endothelium will offset the lower limits of autoregulation and endanger blood flow to vital important hind brain areas, but also to subcortical neuronal networks involved in cognitive processing. Given that apocynin reversed the augmented basal tone by disinhibiting MLCP and that it restored NO-sensitivity in o-BA should encourage its evaluation for the treatment of acute or chronic cerebral circulation deficits, at least in in vivo aging animal models. Second, in vivo electrical stimulation of the great petrosal nerve and of the pterygopalatine ganglion as a means to increase cerebral blood flow has been evaluated in a number of animal studies59–61 and has recently been suggested as an attractive concept for non-pharmacological treatment of acute stroke.14 The effectiveness of that treatment is possibly influenced if neurovascular coupling is impaired in the elderly.

Conclusions

The major findings of the present study are (i) we provided evidence for neurovascular uncoupling of BA in old age and for a hypercontractile state of smooth muscle; (ii) both are partially compensated by an upregulation of endothelial NO release; (iii) the hypercontractile state likely is due to inhibition of MLCP, leading to an increase in Ca2+-sensitivity and (iv) the increased basal tone, inhibition of MLCP and attenuated NO-sensitivity were prevented by acute application of apocynin, suggesting that these effects are mediated by ROS production. Neurovascular coupling has been investigated in the context of the cerebral microcirculation. As the endothelium appears to compensate in part for this neurovascular uncoupling and for the hypercontractility, damaged endothelium, e.g. in atherosclerosis or as a result of surgical interventions, will favor vasoconstriction and reduce blood supply, especially in the elderly. Hypercontractility and augmented eNOS expression was not found in old mice carrying the T-696A/+ mutation, corroborating the involvement of MLCP inhibition suggesting that targeting phosphorylation of MYPT1 may be a novel treatment option for BA dysfunction in the elderly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Jens Brünings (MPI for Metabolism Research) advice on gene targeting strategy and Petra Schiller (University of Cologne) for advice on statistics. The authors also acknowledge the expert technical assistance of S Hilsdorf, W Görner and H Reimer and the help of medical students N Todorović and A Burbach with preliminary experiments.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding was provided by the German Research Association (DFG, SFB612) and the Medical Faculty of University of Cologne (Koeln Fortune) to GP.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors' contributions

Idea, design of experiments and writing manuscript: LTL, HG, SyP, MMS and GP; Generation of MYPT1 T-696A+ mice: TK, SP, MMS, SZ and GP; Contractile studies: JW, DM and LTL; Manufacture of setup for electric field stimulation and test experiments: HM and JS; RT-PCR: SP, MMS, DF and LTL; Immunoblotting: LTL; Confocal imaging: KW, LTL and SyP; Determination of G/F-actin: MAA, MMS and LTL.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this paper can be found at http://jcbfm.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data.

References

- 1.Iadecola C, Park L, Capone C. Threats to the mind: aging, amyloid, and hypertension. Stroke 2009; 40: S40–S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park L, Zhou P, Pitstick R, et al. Nox2-derived radicals contribute to neurovascular and behavioral dysfunction in mice overexpressing the amyloid precursor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105: 1347–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park L, Anrather J, Girouard H, et al. Nox2-derived reactive oxygen species mediate neurovascular dysregulation in the aging mouse brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007; 27: 1908–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han BH, Zhou ML, Johnson AW, et al. Contribution of reactive oxygen species to cerebral amyloid angiopathy, vasomotor dysfunction, and microhemorrhage in aged Tg2576 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112: E881–E890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iadecola C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 2013; 80: 844–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of large cerebral arteries and cerebral microvascular pressure. Circ Res 1990; 66: 8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schonewille WJ, Wijman CA, Michel P, et al. The basilar artery international cooperation study (BASICS). Int J Stroke 2007; 2: 220–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markus HS, van der Worp HB, Rothwell PM. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack: diagnosis, investigation, and secondary prevention. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 989–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lekic T, Ani C. Posterior circulation stroke: animal models and mechanism of disease. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012; 2012: 587590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung S, Mono ML, Fischer U, et al. Three-month and long-term outcomes and their predictors in acute basilar artery occlusion treated with intra-arterial thrombolysis. Stroke 2011; 42: 1946–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattle HP, Arnold M, Lindsberg PJ, et al. Basilar artery occlusion. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 1002–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonatti G, Ferro F, Haglmuller T, et al. Basilar artery thrombosis: imaging and endovascular therapy. Radiol Med 2010; 115: 1219–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schonewille WJ, Wijman CA, Michel P, et al. Treatment and outcomes of acute basilar artery occlusion in the Basilar Artery International Cooperation Study (BASICS): a prospective registry study. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hennerici MG, Kern R, Szabo K. Non-pharmacological strategies for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 572–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toda N, Tanaka T, Ayajiki K, et al. Cerebral vasodilatation induced by stimulation of the pterygopalatine ganglion and greater petrosal nerve in anesthetized monkeys. Neuroscience 2000; 96: 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayajiki K, Kobuchi S, Tawa M, et al. Nitrergic nerves derived from the pterygopalatine ganglion innervate arteries irrigating the cerebrum but not the cerebellum and brain stem in monkeys. Hypertens Res 2012; 35: 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okamura T, Ayajiki K, Fujioka H, et al. Neurogenic cerebral vasodilation mediated by nitric oxide. Jpn J Pharmacol 2002; 88: 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toda N, Okamura T. The pharmacology of nitric oxide in the peripheral nervous system of blood vessels. Pharmacol Rev 2003; 55: 271–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toda N, Okamura T. Mechanism underlying the response to vasodilator nerve stimulation in isolated dog and monkey cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol 1990; 259: H1511–H1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toda N, Ayajiki K. Cholinergic prejunctional inhibition of vasodilator nerve function in bovine basilar arteries. Am J Physiol 1990; 258: H983–H986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayajiki K, Okamura T, Toda N. Nitric oxide mediates, and acetylcholine modulates, neurally induced relaxation of bovine cerebral arteries. Neuroscience 1993; 54: 819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toda N, Ayajiki K, Okamura T. Inhibition of nitroxidergic nerve function by neurogenic acetylcholine in monkey cerebral arteries. J Physiol 1997; 498: 453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang F, Li CG, Rand MJ. Cholinergic prejunctional inhibition of nitrergic neurotransmission in the guinea-pig isolated basilar artery. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 1999; 26: 364–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayajiki K, Fujioka H, Okamura T, et al. Relatively selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibition by 7-nitroindazole in monkey isolated cerebral arteries. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 423: 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchida S, Hotta H. Cerebral cortical vasodilatation mediated by nicotinic cholinergic receptors: effects of old age and of chronic nicotine exposure. Biol Pharm Bull 2009; 32: 341–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de la Torre JC, Aliev G. Inhibition of vascular nitric oxide after rat chronic brain hypoperfusion: spatial memory and immunocytochemical changes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2005; 25: 663–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Modrick ML, Didion SP, Sigmund CD, et al. Role of oxidative stress and AT1 receptors in cerebral vascular dysfunction with aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009; 296: H1914–H1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spescha RD, Shi Y, Wegener S, et al. Deletion of the ageing gene p66(Shc) reduces early stroke size following ischaemia/reperfusion brain injury. Eur Heart J 2013; 34: 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toda N, Ayajiki K, Okamura T. Cerebral blood flow regulation by nitric oxide: recent advances. Pharmacol Rev 2009; 61: 62–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geary GG, Buchholz JN. Selected contribution: effects of aging on cerebrovascular tone and [Ca2+]i. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2003; 95: 1746–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neppl RL, Lubomirov LT, Momotani K, et al. Thromboxane A2-induced bi-directional regulation of cerebral arterial tone. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 6348–6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulvany MJ, Halpern W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circ Res 1977; 41: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandra SB, Mohan S, Ford BM Targeted overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells improves cerebrovascular reactivity in Ins2Akita-type-1 diabetic mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015. Epub ahead of print 26 October 2015. DOI: 10.1177/0271678X15612098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Lubomirov LT, Reimann K, Metzler D, et al. Urocortin-induced decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction in mouse tail arteries is attributable to cAMP-dependent dephosphorylation of MYPT1 and activation of myosin light chain phosphatase. Circ Res 2006; 98: 1159–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daneshtalab N, Smeda JS. Alterations in the modulation of cerebrovascular tone and blood flow by nitric oxide synthases in SHRsp with stroke. Cardiovasc Res 2010; 86: 160–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minami Y, Kimura H, Aimi Y, et al. Projections of nitric oxide synthase-containing fibers from the sphenopalatine ganglion to cerebral arteries in the rat. Neuroscience 1994; 60: 745–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ignacio CS, Curling PE, Childres WF, et al. Nitric oxide-synthesizing perivascular nerves in the rat middle cerebral artery. Am J Physiol 1997; 273: R661–R668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreno-Dominguez A, El-Yazbi AF, Zhu HL, et al. Cytoskeletal reorganization evoked by Rho-associated kinase- and protein kinase C-catalyzed phosphorylation of cofilin and heat shock protein 27, respectively, contributes to myogenic constriction of rat cerebral arteries. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 20939–20952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandala M, Pedatella AL, Morales Palomares S, et al. Maturation is associated with changes in rat cerebral artery structure, biomechanical properties and tone. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2012; 205: 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang F, Li CG, Rand MJ. Mechanisms of electrical field stimulation-induced vasodilatation in the guinea-pig basilar artery: the role of endothelium. J Auton Pharmacol 1997; 17: 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longden TA, Dunn KM, Draheim HJ, et al. Intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels participate in neurovascular coupling. Br J Pharmacol 2011; 164: 922–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nausch LW, Bonev AD, Heppner TJ, et al. Sympathetic nerve stimulation induces local endothelial Ca2+ signals to oppose vasoconstriction of mouse mesenteric arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012; 302: H594–H602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sonkusare SK, Bonev AD, Ledoux J, et al. Elementary Ca2+ signals through endothelial TRPV4 channels regulate vascular function. Science 2012; 336: 597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yagami T, Koma H and Yamamoto Y. Pathophysiological roles of cyclooxygenases and prostaglandins in the central nervous system. Mol Neurobiol 2015. Epub ahead of print 2 September 2015. DOI: 10.1007/s12035-015-9355-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Pfitzer G, Lubomirov LT, Reimann K, et al. Regulation of the crossbridge cycle in vascular smooth muscle by cAMP signalling. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 2006; 27: 445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirano K. Current topics in the regulatory mechanism underlying the Ca2+ sensitization of the contractile apparatus in vascular smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Sci 2007; 104: 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Puetz S, Lubomirov LT, Pfitzer G. Regulation of smooth muscle contraction by small GTPases. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009; 24: 342–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tumer N, Toklu HZ, Muller-Delp JM, et al. The effects of aging on the functional and structural properties of the rat basilar artery. Physiol Rep 2014; 2(6)): pii: e12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin L, Ying Z, Webb RC. Activation of Rho/Rho kinase signaling pathway by reactive oxygen species in rat aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004; 287: H1495–H1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jernigan NL, Walker BR, Resta TC. Reactive oxygen species mediate RhoA/Rho kinase-induced Ca2+ sensitization in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle following chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008; 295: L515–L529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng JC, Cheng HP, Tsai IC, et al. ROS-mediated downregulation of MYPT1 in smooth muscle cells: a potential mechanism for the aberrant contractility in atherosclerosis. Lab Invest 2013; 93: 422–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Loo B, Labugger R, Skepper JN, et al. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J Exp Med 2000; 192: 1731–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Briones AM, Montoya N, Giraldo J, et al. Ageing affects nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase and oxidative stress enzymes expression differently in mesenteric resistance arteries. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol 2005; 25: 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wirth A, Wang S, Takefuji M, et al. Age-dependent blood pressure elevation is due to increased vascular smooth muscle tone mediated by G-protein signalling. Cardiovasc Res 2016; 109: 131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goel A, Su B, Flavahan S, et al. Increased endothelial exocytosis and generation of endothelin-1 contributes to constriction of aged arteries. Circ Res 2010; 107: 242–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heumuller S, Wind S, Barbosa-Sicard E, et al. Apocynin is not an inhibitor of vascular NADPH oxidases but an antioxidant. Hypertension 2008; 51: 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schluter T, Steinbach AC, Steffen A, et al. Apocynin-induced vasodilation involves Rho kinase inhibition but not NADPH oxidase inhibition. Cardiovasc Res 2008; 80: 271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen CP, Chen X, Qiao YN, et al. In vivo roles for myosin phosphatase targeting subunit-1 phosphorylation sites T694 and T852 in bladder smooth muscle contraction. J Physiol 2015; 593: 681–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yarnitsky D, Lorian A, Shalev A, et al. Reversal of cerebral vasospasm by sphenopalatine ganglion stimulation in a dog model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Surg Neurol 2005; 64: 5–11. discussion 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henninger N, Fisher M. Stimulating circle of Willis nerve fibers preserves the diffusion-perfusion mismatch in experimental stroke. Stroke 2007; 38: 2779–2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khurana D, Kaul S, Bornstein NM, et al. Implant for augmentation of cerebral blood flow trial 1: a pilot study evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the Ischaemic Stroke System for treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Int J Stroke 2009; 4: 480–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.