Abstract

A main challenge in realizing the full potential of nucleic acid therapeutics is efficient delivery of them into targeted tissues and cells. N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) is a well-defined liver-targeted moiety benefiting from its high affinity with asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR). By conjugating it directly to the oligonucleotides or decorating it to a certain delivery system as a targeting moiety, GalNAc has achieved compelling successes in the development of nucleic acid therapeutics in recent years. Several oligonucleotide modalities are undergoing pivotal clinical studies, followed by a blooming pipeline in the preclinical stage. This review covers the progress of GalNAc-decorated oligonucleotide drugs, including siRNAs, anti-miRs, and ASOs, which provides a panorama for this field.

Keywords: GalNAc, siRNA, anti-miR, ASO, liver-targeted delivery, ASGPR, oligonucleotide, RNAi

Introduction

RNAi enables efficient target gene silencing by cleaving mRNA or repressing mRNA translation. Through these processes, it compromises gene expression and regulates gene activity. It has not only become a powerful experimental tool for basic research but also provides a new approach to drug discovery and development.1, 2 Over 20 small interfering RNA (siRNA)-based therapeutics are currently in clinical trials, aiming to cure diseases such as transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis,3, 4 delayed graft function (DGF) (A.O. Gaber et al., 2010, Am. J. Transplant., abstract; V. Peddi et al., 2014, Transplantation, abstract), non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION),5 diabetic macular edema (DME),6 hypercholesterolemia,7 cancer,8, 9 Ebola,10 and hepatitis B.11

MicroRNA (miRNAs) are also main family members of RNAi. Their aberrant expression may be involved in various human diseases. Therefore, correcting these miRNA deficiencies by either antagonizing or restoring miRNA function may provide a therapeutic benefit. Several miRNA-based therapeutics are in clinical trials, such as MRX34 (a miR-34a mimic for cancer treatment)12, 13 and RG-101 (an miR-122 inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C) (M.H. van der Ree et al., 2015, Hepatology, abstract). Mirna Therapeutics recently halted a phase 1 study of MRX34 because multiple immune-related severe adverse events (SAEs, grade 4) were observed in five patients dosed with the study drug.14 The reported cytokine release syndrome might be induced by Smarticles, a liposome delivery technology licensed by Marina Biotech.13, 15 Mirna Therapeutics is now pursuing next-generation delivery technology to restart certain projects.

Furthermore, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are also currently in clinical trials for targeting RNAs involved in various diseases, such as prostate/lung cancer (J. Von Pawel et al., 2015, J. Thorac. Oncol., abstract),16 familial amyloid polyneuropathy,17 and Crohn’s disease.18, 19 One ASO named mipomersen (KYNAMRO)20, 21 has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Recently, Exondys 51 (Exondys or eteplirsen), an antisense oligonucleotide indicated for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) in patients who have a confirmed mutation of the DMD gene, was approved by FDA after a complicated and controversial discussion among FDA officials, the sponsor (Sarepta), patients, politicians, and physicians.22, 23 This is a result of struggling to balance a tremendous patient need against the paucity of clinical data. Concern regarding the efficacy of this drug will be further addressed in the results of the new phase III trial. Overall, continued compelling results from clinical trials elicit the anticipation that more oligonucleotide therapeutics will be clinically approved over the next few years. The functional pathway of RNAi, anti-miR, and ASO is shown in Figure 1.

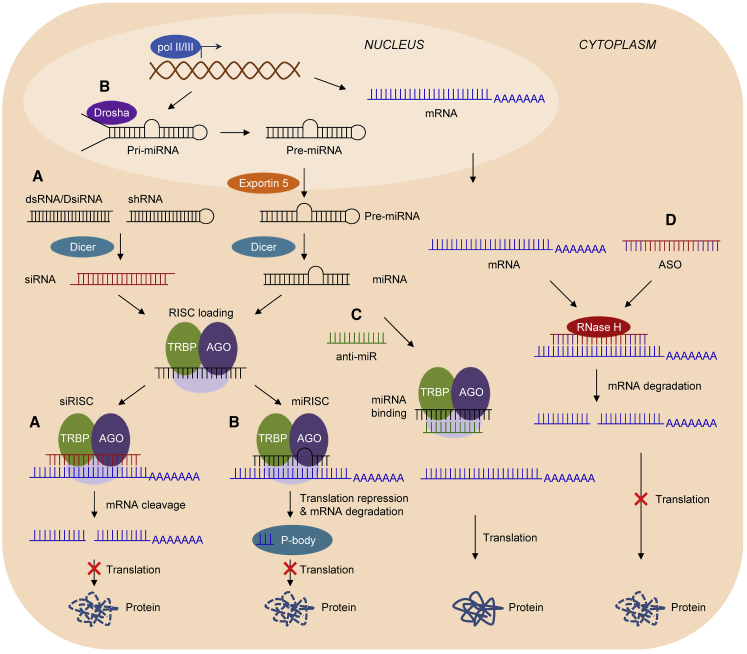

Figure 1.

Gene Regulation Pathways for siRNA, miRNA, Anti-miR, and ASO

(A and B) RNAi pathway. (A) First, miRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II or III (pol II/III) into long (60- to 100-nt) primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) sequences with stem-loop structures that are further cleaved by the Drosha–DGCR8 (DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8) complex to form ∼70-nt precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) structures containing 2-nt overhangs at their 3′ ends.118, 119 After being transported to the cytoplasm by exportin-5, pre-miRNAs are processed by Dicer into mature (∼22-nt) miRNAs. (B) siRNAs can be obtained directly by chemical synthesis. They can also be generated from the cleavage of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), DsiRNA, or short hairpin RNA (shRNA) by Dicer.120, 121 shRNA is transcribed by pol II from an shRNA-expressing plasmid. A chemically synthesized siRNA-, dsRNA-, DsiRNA-, or shRNA-expressing plasmid can be exogenously added into the cell. Then, mature miRNA and siRNA will be assembled into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). RISC contains AGO (Argonaute), TRBP (HIV-1 transactivation responsive element [TAR] RNA-binding protein), and other proteins. The antisense (guide) strand of siRNA/miRNA remains in the RISC, forming activated siRISC or miRISC. Activated siRISC finds its target mRNA in a complete-match way, cleaves the target mRNA, and thus blocks its translation (A). Meanwhile, activated miRISC binds to target mRNA by forming a bulge sequence in the middle and inhibits its expression by either translation repression or mRNA cleavage (B). Translationally repressed mRNA is either stored in P bodies or enters the mRNA decay pathway for destruction. (C) When anti-miRs are added into the cell, they can specifically associate with Argonaute-bound miRNAs, preventing association with target mRNAs, which leads to increased expression of the targeted mRNAs.122 (D) ASOs commonly have a phosphorothioate backbone with flanks that are modified with 2′-O-methyl (2′-OMe) or 2′-MOE or S-cEt residues (highlighted in purple).94 Flank modifications can improve the binding affinity and nuclease resistance of ASOs and reduce immune stimulation of the PS backbone and do not support RNase H cleavage. The unmodified “gap” in a gapmer-mRNA duplex will recruit RNase H, resulting in degradation of duplexed mRNA.123

However, efficient and targeted delivery remains the bottleneck for nucleic acid-based drug development because of the large molecular weight and negative charge. From the 1960s, the action mechanism of the ligands interacting with asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) was thoroughly investigated. ASGPR was first discovered by Morell and colleagues when they studied the metabolism of ceruloplasmin in 1968. It is conserved across species and highly expressed in hepatocytes (∼500,000 copies/cell).24, 25, 26 It can facilitate uptake and clearance of circulating glycoproteins with exposed terminal galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine [GalNAc], an amino sugar derivative of galactose) glycans via clathrin-mediated endocytosis.24, 27, 28 The presence of Ca2+ ions is required for proper recognition and binding of the ligands to the carbohydrate recognition domain of the receptor.29, 30 Only ∼15 min are required for ASGPR internalization and recycling to the cell surface.31

The role of surface carbohydrates in hepatic recognition and transport of circulating glycoproteins, properties of internalization and degradation of asialo-fetuin, and the binding site of hepatic lectin have already been investigated four decades ago.32, 33, 34, 35, 36 In the following three decades (1980s–2000s), asialo-orosomucoid (ASOR, a protein containing galactose and GalNAc residues), galactose, galactoside, galactosamine, galactan, as well as GalNAc were widely tested for the delivery of glycopeptide,37 plasmid DNA,38, 39, 40, 41, 42 ASO,43, 44 antisense peptide nucleic acid (asPNA),45 glycolipid,46 nucleotide analogs,47 and small molecules48, 49 into hepatocytes. Meanwhile, the influences of type,46, 50, 51, 52, 53 number,53, 54 and spatial orientation53, 54, 55 of the sugar moieties and particle size51 on cell uptake by hepatocytes were thoroughly investigated in past decades. As a result, people have reached a consensus that triantennary GalNAc with a mutual distance of ∼20 Å exhibits the highest affinity with ASGPR.51, 56 When GalNAc is used as a targeting moiety in certain nanoparticles, the size of the nanoparticle should be less than 70 nm.51 Consequently, GalNAc has been widely used for liver-targeted delivery of various payloads.56

Recently, GalNAc blooms again for its application in liver-targeted delivery of various oligonucleotides. By attaching GalNAc to the nucleic acid molecules, drug payloads can be efficiently delivered into hepatocytes and trigger the corresponding biological function, which represents a powerful and promising delivery method for nucleic acid-based drug development. This review covers the preclinical and clinical advances of GalNAc-decorated nucleic acid therapeutics, including siRNAs, anti-miRs, and ASOs.

GalNAc Used for siRNA Delivery

Recently, GalNAc was successfully used for liver-targeted siRNA delivery (Figure 2A). As a pioneer in this field, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals has made plenty of advancements (Tables 1 and 2).57 At the beginning, the triantennary GalNAc moiety is covalently attached to the siRNA through a (3R,5S)-3-hydroxy-5-hydroxymethylpyrrolidine scaffold.57, 58 Typically, siRNA is composed of a sense strand with 21 nucleotides (nt) and an antisense strand with 23 nt (S21nt/AS23nt). All nucleotides are completely complementary when pairing with target mRNA. There is a 2-nt overhang at the 3′ end of the antisense strand, which means that it is blunt-ended 3′ of the sense strand and 5′ of the antisense strand. The bases of the siRNA are modified according to standard template chemistry (STC), in which an alternating 2′-F/2′-OMe motif is employed with two phosphorothioate (PS) linkages at the 3′ end of the antisense strand. Modification with 2′-F or 2′-OMe means that the 2′-H is substituted with 2′-F or 2′-OCH3, which may improve the stability and affinity of siRNA. Based on this technology, STC-siRNA-GalNAc conjugates are subcutaneously injected into animals or human beings and trigger efficient gene silencing.

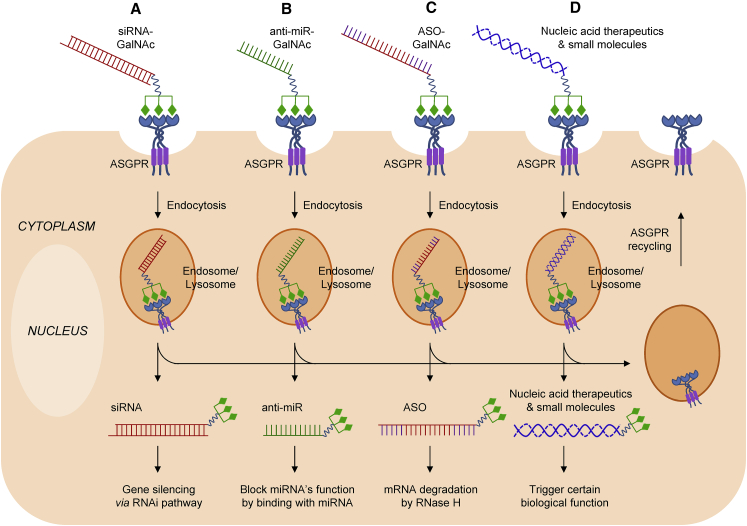

Figure 2.

GalNAc/ASGPR-Mediated Oligonucleotide Delivery to Hepatocytes

(A–D) First, GalNAc-decorated oligonucleotides (siRNA, A; anti-miR, B; ASO, C) are recognized by ASGPR, which triggers endocytosis via the clathrin-mediated pathway. All conjugations of mono-, di-, tri-, or tetra-GalNAc sugars can enhance the delivery efficiency of oligonucleotides to hepatocytes.51, 107 For simplicity, only trivalent GalNAc conjugates are indicated. Then, the payloads escape from the endosome/lysosome and further mediate RNAi (for siRNA, A) block the function of miRNA (for anti-miR, B), or cause mRNA degradation (for antisense, C). The exact mechanism for GalNAc conjugate escaping from the endosome/lysosome is still unspecified. Moreover, GalNAc conjugate can also be used for liver-targeted delivery of other nucleic acid therapeutics and small molecules (such as miRNA and doxorubicin), resulting in certain biological effect in the cells (D). Meanwhile, ASGPR will recycle to the cell surface within ∼15 min31 and mediate the next internalization.

Table 1.

Disease Targets and Nucleic Acid Therapeutic Candidates in the Development Pipeline

| Indication(s) | Therapeutic Name | Target | Type | Delivery | Administration Route | Clinical Status | Company | NCT Number | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familial amyloidotic cardiomyopathy | ALN-TTRsc/Revusiran | TTR | siRNA | STC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase III, terminated | Alnylam | NCT01814839, NCT02292186, NCT01981837, NCT02319005, NCT02595983 | J.D. Gillmore, et al., 2015, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., abstract; 64, 65, 70 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | ALN-PCSsc | PCSK9 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase II | Alnylam | NCT02314442, NCT02597127 | K.J. Pasi et al., 2016, Haemophilia, abstract; K. Fitzgerald et al., 2015, Circulation, abstract; 74, 110 |

| Hemophilia and rare bleeding disorders | ALN-AT3/Fitusiran | AT | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I/II | Alnylam | NCT02035605, NCT02554773 | K.J. Pasi et al., 2016, Haemophilia, abstract; 71, 72, 111 |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria | ALN-CC5 | C5 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I/II | Alnylam | NCT02352493 | 75, 112 |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | ALN-AAT | AAT | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I/II, terminated | Alnylam | NCT02503683 | 66 |

| Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 | ALN-GO1 | GO (HAO1) | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I/II | Alnylam | NCT02706886 | 76, 77, 113 |

| Hepatitis B virus infection | ALN-HBV | conserved region of HBV | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I/II | Alnylam | NCT02826018 | L. Sepp-Lorenzino et al., 2015, Hepatology, abstract;78, 79, 114 |

| Hepatic porphyrias | ALN-AS1 | ALAS1 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I | Alnylam | NCT02452372 | 80, 81, 115 |

| Familial amyloidotic cardiomyopathy | ALN-TTRsc02 | TTR | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I | Alnylam | NCT02797847 | 116 |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | ALN-AAT02 | AAT | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | ||

| β-Thalassemia/iron overload disorders | ALN-TMP | Tmprss6 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | J. Butler et al., 2013, Blood, abstract | |

| Hereditary angioedema | ALN-F12 | F12 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | Akinc et al., 2016, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., abstract | |

| Thromboprophylaxis | ALN-F12 | F12 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | ||

| Hypertriglyceridemia | ALN-AC3 | ApoC3 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | 74 | |

| Mixed hyperlipidemia/hypertriglyceridemia | ALN-ANG | ANGPTL3 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | W. Querbes et al., 2013, Circulation, abstract | |

| Hypertension/pre-eclampsia | ALN-AGT | AGT | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | ||

| Hepatitis D virus infection | ALN-HDV | HDV genome | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | ||

| Chronic liver infection | ALN-PDL | PD-L1 | siRNA | ESC-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Alnylam | ||

| Hepatitis B virus infection | ARC-520 | conserved region of HBV | siRNA | GalNAc-masked DPC | i.v. | phase IIb | Arrowhead | NCT01872065, NCT02535416, NCT02065336, NCT02604199, NCT02604212, NCT02452528, NCT02738008, NCT02577029 | 11, 89, 117 |

| Hepatitis B virus infection | ARC-521 | integrated DNA of HBV genome | siRNA | GalNAc-masked DPC | i.v. | phase I/IIa | Arrowhead | NCT02797522 | |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | ARC-AAT | AAT | siRNA | GalNAc-masked DPC | i.v. | phase I | Arrowhead | NCT02363946 | 89 |

| Thrombosis and angioedema | ARC-F12 | F12 | siRNA | GalNAc-masked DPC | i.v. | preclinical | Arrowhead | S. Melquist et al., 2016, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., abstract | |

| Primary hyperoxaluria type 1 | DCR-PHsc | HAO1 | siRNA | DsiRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Dicerna | 91 | |

| Orphan genetic disease | DCR-undisclosed | undisclosed target | siRNA | DsiRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Dicerna | 91 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | DCR-PCSK9 | PCSK9 | siRNA | DsiRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | research | Dicerna | 91 | |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | DCR-AAT | AAT | siRNA | DsiRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | research | Dicerna | 91 | |

| Fibrotic liver diseases | DCR-HMGB1a | HMGB1 | siRNA | DsiRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | research | Dicerna | 91 | |

| Hepatitis B virus infection | DCR-HBVa | conserved region of HBV | siRNA | DsiRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | research | Dicerna | 91 | |

| Chronic liver diseases (liver fibrosis) | DCR-β-catenina | CTNNB1 | siRNA | DsiRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | research | Dicerna | 91 | |

| Rare genetic diseases/metabolic disorder/multiple liver-related diseases | GalXC UDT #1–#8 | eight undisclosed targets | siRNA | DsiRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | research | Dicerna | 91 | |

| Unknown | unknown | undisclosed targets | siRNA | siRNA-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | research | Silence | ||

| Rare genetic diseases 1 | unknown | undisclosed targets | unknown (ASO or RNAi) | GalNAc-conjugated molecule | NA | research | Wave Life Science | ||

| Rare genetic diseases 2 | unknown | undisclosed targets | unknown (ASO or RNAi) | GalNAc-conjugated molecule | NA | research | Wave Life Science | ||

| Hepatitis C virus infection | RG-101 | microRNA-122 | anti-miR | anti-miR-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase II | Regulus | NA | M.H. van der Ree et al., 2015, Hepatology, abstract;92 |

| NASH/type 2 diabetes/pre-diabetes | RG-125 | microRNA-103/107 | anti-miR | anti-miR-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I | Regulus/AstraZeneca | NA | M. Sundqvist et al., 2015, Diabetologia, abstract; B. Wagner et al., 2015, Diabetologia, abstract;93 |

| High lipoprotein(a) | IONIS-APO(a)-LRx | Apo(a) | ASO | ASO-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | Phase I/IIa | Ionis/Akcea | NCT02414594 | 97, 98, 99 |

| Mixed dyslipidemias | IONIS-ANGPTL3-LRX | ANGPTL3 | ASO | ASO-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I/II | Ionis/Akcea | NCT02709850 | 98 |

| Ocular disease | IONIS-GSK4-LRx | Undisclosed targets | ASO | ASO-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I | Ionis/GSK | NA | |

| Hepatitis B virus infection | IONIS-HBV-LRx | HBV genome | ASO | ASO-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | phase I | Ionis/GSK | NA | 100, 101 |

| Severe high triglycerides / High triglycerides with type 2 diabetes | IONIS-APOCIII-LRX | ApoC3 | ASO | ASO-GalNAc-conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Ionis/Akcea | ||

| Acromegaly | IONIS-GHR-LRx | GHr | ASO | ASO-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Ionis | 102 | |

| β-Thalassemia | IONIS-TMPRSS6-LRx | Tmprss6 | ASO | ASO-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Ionis | 103 | |

| Treatment-resistant hypertension | IONIS-AGT-LRx | AGT | ASO | ASO-GalNAc conjugate | s.c. | preclinical | Ionis |

Abbreviations: TTR, transthyretin amyloidosis; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; AT, antithrombin; C5, complement component 5; AAT, alpha-1 antitrypsin; HAO1 (GO), hydroxyacid oxidase (glycolate oxidase) 1; ALAS1, aminolevulinic acid synthase 1; Tmprss6, transmembrane protease serine 6; F12, factor XII; ApoC3, Apolipoprotein C3; ANGPTL3, Angiopoietin-like 3; AGT, angiotensinogen; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; HMGB1, high mobility group box 1 protein; CTNNB1, catenin beta-1 or β-catenin; GHr, growth hormone receptor; s.c., subcutaneous; i.v., intravenous; NCT, national clinical trial; NA, not available.

Predicted name.

Table 2.

Dosing, Efficacy, and Safety Profiles of siRNA Therapeutics in Clinical Stage Developed by Alnylam

| Therapeutic Name | Clinical Status | Dose and Regimen | Annualized Exposure Levels (g) | Subjects | Efficacy | Safety | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALN-TTRsc/Revusiran | phase II/III | MD | 500 mg, daily × 5, followed by weekly | 28 | patients with ATTR amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy | durable TTR lowering of >85% through 18 months: maximum knockdown of serum TTR up to 98%; mean maximum knockdown of 88% | imbalance of mortality in the Revusiran arm compared with placebo |

| five of nine hATTR-CM patients have stable 6-MWD at 12 months | causes of these safety findings still unclear | ||||||

| ALN-PCSsc | phase I | SAD | 25, 100, 300, 500, 800 mg | NA | patients with elevated LDL-C, patients with high cardiovascular risk and elevated LDL-C | max PCSK9 inhibition of 88.7% with mean max of 82.3% (±2.0) | one subject (800 mg) with mild, localized ISRs |

| max LDL-C reduction of 78.1% with mean max of 59.3% (±5.0) | |||||||

| max reductions: LP(a) (–77%), Total-C (–48%), ApoB (–72%), non-HDL (–68%) | |||||||

| MAD | 125 mg qW × 4 | NA | max PCSK9 inhibition of 94.4% with mean max of 88.5% (±1.6) | three subjects with mild, localized ISRs at higher drug exposures | |||

| 250 mg q2W × 2 | max LDL-C reduction of 83.0% with mean max of 64.4% (±5.4) | one subject (500 mg qM × 2 + statin) experienced ALT elevation ∼4 × ULN without rise in bilirubin—related to concomitant statin therapy | |||||

| 300 mg qM × 2 | max reductions: LP(a) (–76%), total-C (–55%), ApoB (−68%), non-HDL (–73%) | ||||||

| 500 mg qM × 2 | durability sustained up to 6 months supporting bi-annual, low-volume SC dose regimen | ||||||

| on or off statins | |||||||

| phase II | PFD | 300 mg q3M | 1.2, 0.6 | patients | NA | NA | |

| 300 mg q6M | |||||||

| ALN-AT3/Fitusiran | phase I/II | SAD | 0.030 mg/kg × 1 | NA | healthy volunteers | mean maximal AT lowering of 87 ± 1% at 80 mg fixed dose; | no SAEs related to study drug; no thromboembolic events; |

| MAD | 0.015 mg/kg qW × 3 | NA | patients with hemophilia A or B | median ABR = 0, with 53% patients bleed-free and 82% patients experiencing zero spontaneous bleeds in monthly dose cohorts | AEs (excluding ISRs) in ≥ 10% of patients, majority mild or moderate in severity | ||

| 0.045 mg/kg qW × 3 | one patient with transient elevations of ALT (10 × ULN), AST (8 × ULN), CRP, and D-dimer; no increase in total bilirubin | ||||||

| 0.075 mg/kg qW × 3 | |||||||

| 0.225 mg/kg qM × 3 | NA | patients with hemophilia A or B | |||||

| 0.450 mg/kg qM × 3 | |||||||

| 0.900 mg/kg qM × 3 | |||||||

| 1.800 mg/kg qM × 3 | |||||||

| 80 mg qM × 3 | |||||||

| 50 mg qM × 3 | NA | patients with hemophilia A or B with inhibitors | |||||

| 80 mg qM × 3 | |||||||

| PFD | 80 mg qM | 0.96 | patients | ||||

| ALN-CC5 | phase I/II | SAD | 50, 200, 400, 600, 900 mg | NA | healthy volunteers | after single dose, up to 99% C5 KD with mean max KD of 98 ± 0.9% | no reported SAEs, all AEs mild or moderate, no discontinuations, low incidence of mild ISRs |

| after multiple doses, up to 99% C5 KD with mean max KD of 99 ± 0.2% | |||||||

| clamped lowering of C5 with very low inter-subject variability | |||||||

| durable KD and complement inhibition lasting months, supportive of once monthly and potentially once quarterly SC dose regimen | |||||||

| MAD | 100 mg qW × 5; | NA | healthy volunteers | NA | NA | ||

| 200 mg qW × 5; | |||||||

| 400 mg qW × 5; | |||||||

| 600 mg q2W × 7; | |||||||

| 200 mg qW × 5, q2W × 4; | |||||||

| 200 mg qW × 5, qM × 2. | |||||||

| PFD | 600 mg, q3M | 2.4 | patients | NA | NA | ||

| ALN-AAT | phase I/II | SAD | 0.1 mg/kg | NA | healthy volunteers | 6.0 mg/kg dose group; | dose-dependent increase in hepatic transaminase observed |

| 0.3 mg/kg | max AAT KD: 88.9% | three patients at 6.0 mg/kg with liver enzyme (ALT, AST) elevation (∼6–8 ULN) | |||||

| 1.0 mg/kg | mean maximal KD: 83.9 ± 2.6% | ||||||

| 3.0 mg/kg | mean AAT KD at ∼6 months: 75.0 ± 1.2% | ||||||

| 6.0 mg/kg | |||||||

| MAD | 1.0 mg/kg, q28d × 4 | ∼1.0 | healthy volunteers | AAT knockdown at 1 mg/kg multidose comparable with 3 and 6 mg/kg single doses | NA | ||

| ALN-GO1 | phase I/II | SAD | 0.3 mg/kg × 1 | NA | healthy volunteers | dose-dependent increase in plasma and urine glycolate levels, with earliest onset of activity at higher doses evident by day 29 post dose and sustained until day 85 | no drug-related SAEs or discontinuations because of AEs |

| 1.0 mg/kg × 1 | the lowest dose with appreciable glycolate increase is 1 mg/kg | total of 61 AEs reported, all were mild to moderate | |||||

| 3.0 mg/kg × 1 | |||||||

| 6.0 mg/kg × 1 | |||||||

| MAD | 1.0 mg/kg, q28d × 3 | NA | PH1 patients | NA | NA | ||

| ALN-HBV | phase I/II | SAD | 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0 mg/kg; 2 optional doses | NA | healthy volunteers | preclinical data in AAV-HBV mouse model | NA |

| SAD | 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 3.0 mg/kg; 3 optional doses | NA | patients | single SC dose at 3 mg/kg achieves > 2 log10 HBsAg reduction lasting > 30 days | |||

| MAD | starting dose TBD, Q4W × 4 doses; TPP: 100–200 mg fixed dose monthly | TPP: 1.2–2.4 | patients | > 4 month HBsAg KD after 3 mg/kg qW × 3. | |||

| ALN-AS1 | phase I | SAD | 0.035 mg/kg × 1 | NA | ASHE patients | rapid, dose-dependent, and durable lowering of ALAS1 mRNA and urinary ALA and PBG | no drug-related SAEs or discontinuations because of AEs |

| 0.10 mg/kg × 1 | for mRNA: 64% ± 1% with a single 2.5 mg/kg dose and 54% ± 2% with multiple 1.0 mg/kg doses | all AEs were mild or moderate in severity | |||||

| 0.35 mg/kg × 1 | for urinary ALA and PBG: 86% and 95%, respectively, with a single 2.5 mg/kg dose | two SAD subjects (0.035 and 0.10 mg/kg) were hospitalized for SAE of “abdominal pain” but not drug-related | |||||

| 1.0 mg/kg × 1 | 84% and 89%, respectively, with multiple 1.0 mg/kg doses | one MAD subject (1 mg/kg) experienced a miscarriage but not drug-related | |||||

| 2.5 mg/kg × 1 | |||||||

| MAD | 0.35 mg/kg qM × 2 | NA | |||||

| 1.0 mg/kg qM × 2 | |||||||

| MD | TBD | NA | AIP patients with recurrent attacks | NA | NA | ||

| PFD | 2.5 mg/kg qM | ∼2.4 | patients | NA | NA | ||

| ALN-TTRsc02 | Phase I | SAD and MAD | in NHP: | TPP in human: ∼0.4 | phase I: healthy volunteers | in NHP; | NA |

| 1 or 3 mg/kg qM × 4. | TPP: patients with ATTR amyloidosis | sustained ≥ 95% TTR knockdown with qM dosing at 1 mg/kg in NHP | |||||

| TPP in human: | sustained 90% TTR knockdown up to 4 months after last 3 mg/kg dose | ||||||

| 50–100 mg qQ | SD 1 mg/kg ALN-TTRsc02 triggered higher serum TTR lowering compared with MD 5 mg/kg Revusiran | ||||||

Developed by Alnylam.70, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116 Abbreviations: SAD, single ascending dose; MAD, multiple ascending dose; SD, single dose; MD, multiple dose; PFD, projected fixed dose; qW, weekly; qM, monthly; qQ, quarterly; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; total-C, total cholesterol; non-HDL, non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol; ApoB, apolipoprotein B; ABR, annualized bleeding rate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein; PH1, primary hyperoxaluria type 1; AAV, adeno-associated virus; ASHE, asymptomatic high excreters; AIP, acute intermittent porphyria; KD, knockdown; TBD, to be determined; TPP, target product profile; NHP, non-human primate.

For the second-generation technology, siRNAs are modified with enhanced stabilization chemistry (ESC).56 In this case, modifications may be made according to, but not limited to, the following principles. (1) Three consecutive nucleotides located at the 11, 12, and 13 positions of the antisense strand from the 5′ end are modified with 2′-OMe, and three complementary nucleotides on the sense strand are modified with 2′-F. For siRNA with a S21nt/AS23nt structure, three 2′-F modifications are located at 9, 10, and 11 from the 5′ end of the sense strand. Basically, three consecutive 2′-F modifications occur at or near the cleavage site of the sense strand. Optionally, additional consecutive 2′-OMe modifications may occur at the 21, 22, and 23 positions of the antisense strand from the 5′ end.57 More motifs with three identical modifications on three consecutive nucleotides may occur, according to several patent documents filed by Alnylam.59 (2) Other nucleotides of both the sense and antisense strands are still modified with alternating 2′-F/2′-OMe motifs, wherein the modification of the nucleotide adjacent to the motif with three consecutive modifications is different than the modifications on that motif.59 (3) The nucleotide at the 1 position of the 5′ end of the duplex in the antisense strand is selected from the group consisting of adenosine (A), 2'-deoxyadenosine (dA), 2'-deoxyuridine (dU), uridine (U), and 2'-deoxythymidine (dT), and at least one of the first, second, and third base pairs from the 5′ end of the antisense strand is an AU base pair.59, 60 (4) In addition to the changes on the nucleotide sequence, two additional phosphorothioate (or methylphosphonate) internucleotide linkages were also incorporated at the 5′ ends of both strands.

Furthermore, the latest progress in siRNA modification provides more complicated information,60 which includes the following. (1) A thermally destabilizing nucleotide (e.g., an acyclic nucleotide such as unlocked nucleic acid [UNA] or glycol nucleic acid [GNA], mismatch, abasic, or DNA) may be placed at a site opposite to the seed region of the antisense strand (i.e., at positions 2–8 of the 5′ end of the antisense strand), which typically may be placed at 14–17 (e.g., 15) of the 5′ end of the sense stand.60 (2) One position at the sense strand (e.g., 11) and three positons at the antisense strand (e.g., 2, 14, and 10) may use nucleotides comprising a modification, providing the nucleotide a steric bulk that is less than or equal to the steric bulk of a 2′-OMe modification. This nucleotide can be selected from DNA, RNA, locked nucleic acid (LNA), 2′-F, or 2′-F-5′-methyl.60 (3) It may comprise a 5′-vinyl phosphonate (5′-VP) because this phosphate mimic can enhance the potency of synthetic siRNA.61, 62 (4) Strategies regarding the sequence length and structure of siRNA, blocks of phosphorothioate internucleotide linkages, and AU pairing at the 5′ end of the antisense strand are similar to the abovementioned principles. However, there is a claim that the double-strand RNA agent does not contain any 2′-F modification, which is very different from the above descriptions and even from the claims in the same patent document.60 It is worth noting that the exact chemical composition of ESC is not disclosed, and there is no strict discrimination between STC and ESC. The modifications may be varied among different siRNA sequences.

Resulting from these changes, the stability of ESC-siRNA-GalNAc conjugates was significantly enhanced. The pharmacokinetic properties of ESC siRNA were superior to the STC siRNA. In a direct comparison of the two siRNA chemistries, ESC-siRNA-GalNAc conjugates exhibited 5- to 10-fold higher potency than STC-siRNA-GalNAc conjugates. For transthyretin (TTR)-targeting siRNA-GalNAc conjugates, refinements of the siRNA chemistry achieved a 5-fold improvement in efficacy over the parent design in vivo, with a median effective dose (ED50) of 1 mg/kg following a single dose,57 whereas, for antithrombin (AT3)-targeting siRNA-GalNAc conjugates, the ESC modulator showed a >10-fold improvement in efficacy over the STC design after a single dose.63

Revusiran (ALN-TTRsc) (J.D. Gillmore et al., 2015, J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., abstract)64, 65 is a TTR-targeting siRNA-GalNAc conjugate employing STC technology. Initial data from the Revusiran phase 2 open-label extension (OLE) study64 continued to show robust (serum TTR levels reduced by ∼90% with multiple dosing) and sustained (clinical measures typically stable to day 90) knockdown of serum TTR in hereditary ATTR (hATTR) patients with cardiomyopathy. Five of nine patients had a stable 6-min walk distance (6-MWD) at 12 month (Table 2). Unfortunately, Alnylam recently discontinued the development of Revusiran because of an imbalance of mortality in the Revusiran arm compared with placebo (Table 2). There were 17 deaths among patients on the study drug and two deaths among patients on placebo up to October 8, 2016. Although no conclusive evidence for a drug-related neuropathy signal was found in the phase III ENDEAVOUR study, the data monitoring committee found that the benefit-risk profile for Revusiran no longer supported continued dosing. The exact reason for the deaths was still unclear, the company said. However, Revusiran is the only project using STC technology, and the annualized exposure level of Revusiran (∼28 g) is much higher (∼12–70 times) than that of other ESC-GalNAc conjugate projects (∼0.4–2.4 g) (Table 2). On the other hand, patient recruitment in the clinical study of IONIS-TTRRX,17 a similar project developed by Ionis Pharmaceuticals, started earlier than Revusiran. The total patient volume of this orphan disease is limited. As a result, the health condition of some patients recruited by Alnylam might be not well. Moreover, the phase III APOLLO study of Patisiran, a liposome-based sister product of Revusiran, will continue.

Based on the technology of ESC-siRNA-GalNAc conjugate, Alnylam has established a promising siRNA drug development pipeline for genetic medicines, cardio-metabolic diseases, and hepatic infectious diseases. Among them, ALN-AAT66 is a phase I/II RNAi therapeutic targeting alpha-1 antitrypsin for the treatment of alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency-associated liver disease. Unfortunately, Alnylam also discontinued its development at the end of September, 2016 because they observed transient, asymptomatic, and dose-dependent increases in liver enzymes in 3 of 15 healthy volunteers exposed to single doses of ALN-AAT (Table 2). Although there were no drug-related SAEs, discontinuations because of AEs, or injection site reactions (ISRs) reported, the company still decided to optimize the tolerability profile for this project. As a result, ALN-AAT02, a follow-on molecule targeting a different sequence, has been added to the discovery pipeline (Table 1).

Actually, elevated liver enzymes were also observed for projects of ALN-PCSsc (one patient) and ALN-AT3 (one patient), which showed ∼4 × upper limit of normal (ULN) and 8–10 × ULN increases in enzymes, respectively. However, they showed no increase in total bilirubin. No clear explanation for the toxicity was provided. It is unclear why Alnylam claims, in the patent of WO2016028649,60 that double-stranded RNA does not contain any 2′-F modification. They perhaps just intend to own the property of an siRNA agent without a 2′-F modification. However, it is also possible that Alnylam has some special considerations; e.g., safety issues. Moreover, ASOs with a full PS backbone may result in obvious toxicities, such as increased coagulation times, decreased platelets, and immune activation;67, 68, 69 the increased PS linkages in ESC may also contribute to toxicity.

ALN-TTRsc02, another ESC-siRNA-GalNAc conjugate, is in phase I clinical study. Preclinical data of ALN-TTRsc02 showed potent and highly durable knockdown of serum TTR of up to 99%, with multi-month durability achieved after just a single dose. It was also found to be generally well tolerated with no SAEs at doses as high as 100 mg/kg. The annualized exposure level of ALN-TTRsc02 (∼0.4 g as the target product profiles described70) is projected to be much lower than that of Revusiran (∼28 g) (Table 2).

Except for the above projects, Fitusiran (ALN-AT3) (K.J., Pasi et al., 2016, Haemophilia, abstract)71, 72 (targeting antithrombin for the treatment of hemophilia and rare bleeding disorders), ALN-PCSsc (K. Fitzgerald et al., 2015, Circulation, abstract)73, 74 (targeting proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia), ALN-CC575 (targeting complement component 5 for the treatment of complement-mediated diseases), ALN-GO176, 77 (targeting glycolate oxidase for the treatment of primary hyperoxaluria type 1), and ALN-HBV (L. Sepp-Lorenzino et al., 2015, Hepatology, abstract)78, 79 (targeting the hepatitis B virus [HBV] genome for the treatment of HBV infection) are undergoing phase II or phase I/II clinical trial. ALN-AS180, 81 (targeting aminolevulinic acid synthase 1 for the treatment of acute hepatic porphyrias) is in phase I clinical study. Moreover, several other projects, including ALN-TMP (J. Butler et al., 2013, Blood, abstract), ALN-F12 (A. Akinc et al., 2016, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., abstract), ALN-AC374, ALN-ANG (W. Querbes et al., 2013, Circulation, abstract), ALN-AGT, ALN-HDV, and ALN-PDL, are undergoing preclinical investigations (Table 1). It is worth noting that all of these programs employ ESC-GalNAc conjugate delivery technology, which may open a window for siRNA-GalNAc conjugate therapeutics.

Moreover, Alnylam continuously worked on improving the conjugate chemistry. Matsuda et al. (Alnylam team)82 systematically explored the effect of display and positioning of the GalNAc moiety within the siRNA duplex on ASGPR binding and RNAi activity. Data suggested that an array of nucleosidic GalNAc monomers resembling a dispersed trivalent ligand at or near the 3′ end of the sense strand retained in vitro and in vivo siRNA activity, similar to the parent clustered conjugate design. Rajeev et al., (Alnylam team)58 further proved that simplified trivalent GalNAc-conjugated siRNAs, based on a novel non-nucleosidic linker, could be synthesized by sequential covalent attachment of the trivalent GalNAc to the 3′ end of the sense strand under solid-phase synthesis conditions. The novel siRNA-GalNAc conjugates showed similar in vitro and in vivo potency as the parent trivalent siRNA-GalNAc one.

In addition, Prakash and colleagues (Ionis team)62 investigated the effect of combing the PS modification with a metabolically stable phosphate analog (E)-5′-VP and GalNAc cluster conjugation on the activity of fully 2′-modified siRNA in cell culture and mice. Data revealed that integrating multiple chemical approaches in one siRNA molecule improved potency 5- to 10-fold. Parmar et al. (Alnylam team)61 also demonstrated that incorporation of (E)-5′-VP results in up to 20-fold-improved in vitro potency and up to a 3-fold benefit in in vivo activity by promoting Ago2 loading and enhancing metabolic stability.

The great improvements of siRNA-GalNAc conjugate chemistries, in terms of both siRNA stabilization/recognition and the linkage methodologies, will facilitate GalNAc conjugate oligonucleotides-based drug development. Taken together, the sequence (which originally determines its activity), modification (which influences siRNA stability, activity, and the pharmacokinetics [PK] profile in the liver), linker chemistry, display, and positioning of the GalNAc moiety will all affect the potency and safety of the siRNA modality. Hence, people should treat the siRNA-GalNAc conjugate as a whole when they use it.

Dynamic polyconjugates (DPCs), a delivery platform developed by Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals,11, 83, 84, 85, 86 employs GalNAc as a targeting and masking moiety linked to the side chain by carboxy dimethyl maleic anhydride (CDM) bond. CDM bond is a pH-sensitive linkage that is degraded quickly in an acidic environment. The backbone is an endosomolytic polymer (DPC1.0)83, 84 or polypeptide (DPC2.0).11 The low pH in the endosome/lysosome environment results in CDM degradation, leaving of the masking agents (GalNAc or polyethylene glycol [PEG]), and protonation of the backbone.87 Protonation further leads to inflow of H+ and Cl− and water into the endosomes, resulting in osmotic swelling and endosome rupture.88 As a result, siRNAs successfully release from the endosome and/or lysosome and trigger RNAi. By this smart design, all functional elements, including the endosomolytic backbone, charge-masking agents (GalNAc and/or PEG), environment-responsive linkage (CDM), targeting ligand (GalNAc), and siRNA, accomplish their missions at different stages and finally induce efficient gene silencing.

For the first-generation technology (DPC1.0), siRNA was covalently conjugated to the polymer backbone (a polymer composed of butyl and amino vinyl ether, PBAVE) by disulfide linkage.83 However, siRNA is not linked with the polypeptide (melitin-linked peptide, a kind of membrane-lytic peptide) for the second-generation technology (DPC2.0).11 Instead, siRNA is modified with cholesterol, a lipophilic molecule facilitating membrane penetration. Cholesterol-modified siRNA (chol-siRNA) and GalNAc-masked polypeptides are co-injected into animals or human beings. In addition, chol-siRNA can also be co-injected with GalNAc/PEG-masked PBAVE, resulting in efficient gene silencing in animals.84

By employing DPC2.0, Arrowhead has established an attractive siRNA therapeutics pipeline (Table 1). ARC520, a potentially curative therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B infection, is undergoing phase IIb clinical trial.11, 89 According to the clinical data disclosed by Arrowhead, ARC-520 could silence all HBV gene products and intervene upstream of the reverse transcription process. ARC-520 and entecavir produced rapid HBV DNA suppression with all hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg)-positive, treatment-naive patients, achieving serum HBV DNA reductions of up to 5.5 log10 (99.9997%), and all HBeAg-negative, treatment-naive patients, achieving reductions that put them below the limit of quantitation. ARC-520 effectively inhibited HBV covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA)-derived mRNA with observed viral protein reduction in HBV patients of up to 2.0 log10 (99%) after a single dose. Complexed hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) antibodies (anti-HBs) were developed and detected in HBV patients treated with ARC-520, which may represent a recovery of the immune system response and functional cure. Meanwhile, inspired by the discovery that integrated HBV DNA plays a pivotal role in the HBV life cycle and HBsAg expression, Arrowhead further developed ARC-521, a siRNA therapeutic targeting integrated HBV DNA. It has been dosed in a first-in-human phase I/IIa study now.90 Moreover, ARC-AAT (C.I. Wooddell et al., 2014, Hepatology, abstract) (targeting alpha-1 antitrypsin for the treatment of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency) is in phase I clinical study. ARC-F12 (S. Melquist et al., 2016, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., abstract), a pre-clinical program, is designed for the treatment of hereditary angioedema (HAE) and thromboembolic disorders.

GalNAc delivery technology is also progressing greatly in Dicerna Pharmaceuticals. Different from Alnylam’s triantennary GalNAc conjugates, tetra-antennary GalNAc conjugates (GalXC) were preferred by Dicerna.91 In fact, it has been well documented that the dramatic hierarchy of the inhibitory ability of different valences of oligosaccharides to inhibit the binding of labeled ligand to the mammalian hepatic lectin on rabbit hepatocytes is as follows: tetra-antennary > triantennary ≫ biantennary ≫ monoantennary.51, 54 However, the inhibition potency of tetra-antennary oligosaccharide was just slightly higher than triantennary oligosaccharide.54 Four GalNAc molecules are attached to four bases of an internal complementation pairing constant sequence. This constant sequence is linked to the 3′ end of the passenger strand. Finally, the guide strand and the extended passenger strand are annealed, forming a mature Dicer-substrate RNA (DsiRNA)-GalNAc conjugate with a nick at the 3′ end of the guide strand. Dicerna claimed that tetraloop-structured GalNAc conjugate provides enhanced stabilization, rapid generation time, and simple “on-column” oligo manufacturing, and properly orients multiple ligands for presentation to hepatocytes. Based on this technology, many siRNA drug candidates are developed at the preclinical stage (Table 1). Potent and durable pharmacodynamic effects have been achieved for several targeted genes, such as HAO1, AAT, HMGB1, β-catenin, PCSK9, and HBV.91 For example, a single dose of DCR-PHsc (3 mg/kg) achieved 94% maximum HAO1 mRNA silencing and 88% average silencing. A 6-month multi-dose of DCR-PHsc achieved 93% maximum mRNA silencing on day 77. The no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) of this GalNAc conjugate is >100 mg/kg after being administered via subcutaneous injection weekly.

Moreover, Silence Therapeutics has also added siRNA-GalNAc conjugates to their drug development pipeline. However, no detailed information is disclosed to date. Recently, Wave Life Sciences announced that it has reached a cooperation agreement with Pfizer for the potential development of nucleic acid therapies. The collaboration will combine Wave’s proprietary antisense and RNAi capabilities with GalNAc and Pfizer’s hepatic targeting technology for potential development of optimized therapeutics.

GalNAc Used for Liver-Targeted Delivery of Anti-miRs

GalNAc conjugate technology has also been used for anti-miR (antagomir) delivery (Figure 2B; Table 1). RG-101, a GalNAc-conjugated oligonucleotide targeting miR-122 developed by Regulus Therapeutics, is the first microRNA therapeutic for the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV). Phase II clinical data demonstrated that a single dose of RG-101 resulted in a mean viral load reduction of 4.8 log10 (4 mg/kg) and 4.1 log10 (2 mg/kg) at 29 days and a mean viral load reduction of 4.7 log10 (4 mg/kg) and 3.6 log10 (2 mg/kg) at 57 days.92 More importantly, a single dose of RG-101 has resulted in undetectable HCV RNA levels in chronic hepatitis C patients at week 28 of follow-up (M.H. van der Ree et al., 2015, Hepatology, abstract). RG-125 (AZD4076), another GalNAc-conjugated anti-miR targeting microRNA-103/107 for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in patients with type 2 diabetes/pre-diabetes, has been dosed in a first-in-human phase I study by Regulus’s collaboration partner AstraZeneca (M. Sundqvist et al., 2015, Diabetologia, abstract; B. Wagner et al., 2015, Diabetologia, abstract).93 Regulus’s anti-miR modulators combine all three leading RNA technologies: Alnylam’s GalNAc delivery platform, Ionis’s G2.5 modification strategy, and Regulus’s proprietary linker conjugate. Their proprietary linker chemistry allows quick release of anti-miR to the cytoplasm after hepatocytes uptake.

GalNAc Used for ASO Delivery to Hepatocytes

GalNAc conjugate was also employed in ASO drug development (Figure 2C). Among the ligand conjugate antisense (LICA) drugs developed by Ionis Pharmaceuticals, GalNAc is a leading conjugate technology that was designed to enhance the delivery of ASOs to hepatocytes. With the GalNAc conjugate, GalNAc-ASO showed ∼10-fold greater potency than ASO without conjugate,94 which supported lower doses and/or less frequent dosing (potential for once monthly). The enhanced drug profile is optimal for use in broader patient populations because it showed greater convenience for patients, better potency and tolerability, and higher probability of compliance.

Ionis has developed generation 2.5 chemistry for ASO modification in which short S-2′-O-Et-2′,4’-bridged nucleic acid (S-cEt) is used to modify an ASO gapmer. The potency of ASO designs comprised with S-cEt was enhanced approximate 10-fold compared with the ASO modified with 2′-O-methoxyethyl [2′-MOE], Generation 2.0).94 When combining GalNAc conjugation with S-cEt modification, ∼60-fold enhancement in potency relative to the parent MOE ASO was observed.94 MOE or S-cEt modifications are placed at the 5′ and 3′ wings of the ASO gapmer. DNA bases are located at the middle, and phosphorothioate linkages may be employed throughout the sequence. Moreover, except for 2′ modification chemistry (e.g., 2′-F, 2′-OMe, 2′-MOE, and 2′-O-ethyl [cEt]), 2′,4′-constrained bicyclic nucleic acid (BNA) can be also used to build ASOs, such as LNA, 2′-O-Ethyl cEt BNA, and 2′-O-methoxyethyl (cMOE) BNA.95

Ionis comprehensively investigated structure-activity relationships of triantennary GalNAc-conjugated ASOs.96 Seventeen GalNAc clusters were assembled from six distinct scaffolds, including the structures of Tris, Triacid, Lys-Lys, Lys-Gly, Trebler, and Hydroxyprolinol, and attached to ASOs. The potency of these conjugates was thoroughly evaluated both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that a simplified Tris-based GalNAc cluster (trishexylamino [THA]-GalNAc) empowered the ASOs’ wonderful potency and safety. THA-GalNAc can be efficiently assembled using readily available starting materials and conjugated to ASOs using a solution-phase conjugation strategy, providing a clinically applicable GalNAc-ASO modality. Ionis has added the THA-C6 triantenerrary GalNAc to eight liver-targeted ASOs, including ISIS-APO(a)-LRx,97, 98, 99 IONIS-ANGPTL3-LRx,98 IONIS-GSK4-LRx, IONIS-HBV-LRx (ISIS-GSK6-LRx),100, 101 IONIS-APOCIII-LRx, IONIS-GHR-LRx,102 IONIS-AGT-LRx, and IONIS-TMPRSS6-LRx.103

IONIS-APO(a)-LRx is a LICA version of IONIS-APO(a)Rx. IONIS-APO(a)-LRx demonstrated over 20- to 30-fold improvement in potency over IONIS-APO(a)Rx, as measured by liver apo(a) mRNA and plasma apo(a) protein levels.96, 97 Subjects who received a single dose of 80 mg IONIS-APO(a)-LRx achieved substantial reductions in lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) of up to 97% and a mean reduction of 79% (p = 0.01) at 30 days. The long duration of the effect resulted in significant Lp(a) reductions of nearly 50% 90 days after the single dose.

In addition, Ionis demonstrated that the triantennary GalNAc cluster could be readily assembled on the 5′ end of ASOs via solid-phase synthetic methods using phosphoramidite chemistry.104 It could be also attached to 5′-hexylamino (5′-HA)-modified ASOs via a solution-phase conjugation strategy by involving pentafluorophenolic ester intermediates, which avoided loading of GalNAc clusters onto a solid support.105 Meanwhile, 5′ conjugation of the GalNAc cluster could be easily achieved based on a nitromethanetrispropionic acid core.106 Data manifested that 5′-conjugated ASOs are more potent in primary hepatocytes as well as in animals than 3′-conjugated ASOs,105 and the GalNAc ASOs showed 5- to 10-fold improvement in activity compared with the parent ASOs without GalNAc moiety.104, 106

Recently, Ionis further proved that conjugation of two and even one GalNAc sugar to single-stranded chemically modified ASOs can enhance potency 5- to 10-fold in mice.107 Yamamoto et al.108 observed that LNA-modified ASOs tethered to a synthetically accessible, phosphodiester-linked monovalent GalNAc unit at the 5′ terminus showed ideal potency in vivo. Phosphodiester was preferable to phosphorothioate as an interunit linkage in terms of ASGPR binding and subcellular behavior of the ASOs. The gene-silencing effects are positively correlated with the number of GalNAcs.

In another Ionis study,109 the THA-C6 triantenerrary GalNAc conjugate at the 5′ end of the ASO was rapidly metabolized and excreted with 25.67% ± 1.635% and 71.66% ± 4.17% of radioactivity recovered in rat urine and feces within 48 hr post dose. Unchanged drug, short-mer ASOs, and linker metabolites were detected in the urine. Fourteen novel linker-associated metabolites were discovered in rat urine, and metabolites in the bile and feces were identical to urine except for oxidized linear and cyclic linker metabolites. These findings provided an improved understanding of GalNAc-conjugated-ASO metabolism pathways for similar ASO agents. All of the above efforts will undoubtedly shed light on ASO-GalNAc chemistry and the mechanism of GalNAc/ASGPR recognition and facilitate ASO-based drug development.

Conclusions and Insights

GalNAc represents a powerful and reliable liver-targeted delivery platform for the development of nucleic acid therapeutics. In addition to siRNAs, anti-miRs, and ASOs, other nucleic acid therapeutics or small molecules, such as miRNA, nucleoside analog (fluorouracil [5-Fu]),47 small molecules (e.g., doxorubicin),48 and even plasmid DNA41 and mRNA (Figure 2D), can also be decorated with GalNAc, which may remarkably enhance their potency compared with their parent modalities without conjugation. With the continuous optimizations of conjugate chemistry and manufacturing technique as well as the improved understanding of ligand/receptor recognition and drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK) properties in vivo, GalNAc modulators could strongly influence biomedical prospects in the next few years.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81402863), the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2014M550008 and 2015T80016), and financial support from the Beijing Institute of Technology.

References

- 1.Bumcrot D., Manoharan M., Koteliansky V., Sah D.W. RNAi therapeutics: a potential new class of pharmaceutical drugs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:711–719. doi: 10.1038/nchembio839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lares M.R., Rossi J.J., Ouellet D.L. RNAi and small interfering RNAs in human disease therapeutic applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coelho T., Adams D., Silva A., Lozeron P., Hawkins P.N., Mant T., Perez J., Chiesa J., Warrington S., Tranter E. Safety and efficacy of RNAi therapy for transthyretin amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:819–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suanprasert N., Berk J.L., Benson M.D., Dyck P.J., Klein C.J., Gollob J.A., Bettencourt B.R., Karsten V., Dyck P.J. Retrospective study of a TTR FAP cohort to modify NIS+7 for therapeutic trials. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014;344:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solano E.C., Kornbrust D.J., Beaudry A., Foy J.W., Schneider D.J., Thompson J.D. Toxicological and pharmacokinetic properties of QPI-1007, a chemically modified synthetic siRNA targeting caspase 2 mRNA, following intravitreal injection. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2014;24:258–266. doi: 10.1089/nat.2014.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee D.U., Huang W., Rittenhouse K.D., Jessen B. Retina expression and cross-species validation of gene silencing by PF-655, a small interfering RNA against RTP801 for the treatment of ocular disease. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;28:222–230. doi: 10.1089/jop.2011.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald K., Frank-Kamenetsky M., Shulga-Morskaya S., Liebow A., Bettencourt B.R., Sutherland J.E., Hutabarat R.M., Clausen V.A., Karsten V., Cehelsky J. Effect of an RNA interference drug on the synthesis of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and the concentration of serum LDL cholesterol in healthy volunteers: a randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:60–68. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61914-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tabernero J., Shapiro G.I., LoRusso P.M., Cervantes A., Schwartz G.K., Weiss G.J., Paz-Ares L., Cho D.C., Infante J.R., Alsina M. First-in-humans trial of an RNA interference therapeutic targeting VEGF and KSP in cancer patients with liver involvement. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:406–417. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis M.E., Zuckerman J.E., Choi C.H., Seligson D., Tolcher A., Alabi C.A., Yen Y., Heidel J.D., Ribas A. Evidence of RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted nanoparticles. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geisbert T.W., Lee A.C., Robbins M., Geisbert J.B., Honko A.N., Sood V., Johnson J.C., de Jong S., Tavakoli I., Judge A. Postexposure protection of non-human primates against a lethal Ebola virus challenge with RNA interference: a proof-of-concept study. Lancet. 2010;375:1896–1905. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60357-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wooddell C.I., Rozema D.B., Hossbach M., John M., Hamilton H.L., Chu Q., Hegge J.O., Klein J.J., Wakefield D.H., Oropeza C.E. Hepatocyte-targeted RNAi therapeutics for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Mol. Ther. 2013;21:973–985. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beg M., Brenner A., Sachdev J., Borad M., Cortes J., Tibes R. 4LBA A phase 1 study of first-in-class microRNA-34 mimic, MRX34, in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or advanced cancer with liver metastasis. Eur. J. Cancer. 2014;50 196–196. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouchie A. First microRNA mimic enters clinic. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:577. doi: 10.1038/nbt0713-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirna. (2016). Mirna Therapeutics Halts Phase 1 Clinical Study of MRX34. http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/AMDA-2PXH94/3644053911x0x908896/E5BD13E6-BF9E-4FA3-9651-B51597F7FC90/MIRN_News_2016_9_20_General_Releases.pdf.

- 15.Sheridan C. Drug developers refocus efforts on RAS. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:217–218. doi: 10.1038/nbt0316-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saad F., Hotte S., North S., Eigl B., Chi K., Czaykowski P., Wood L., Pollak M., Berry S., Lattouf J.B., Canadian Uro-Oncology Group Randomized phase II trial of Custirsen (OGX-011) in combination with docetaxel or mitoxantrone as second-line therapy in patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer progressing after first-line docetaxel: CUOG trial P-06c. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:5765–5773. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ackermann E.J., Guo S., Benson M.D., Booten S., Freier S., Hughes S.G., Kim T.W., Jesse Kwoh T., Matson J., Norris D. Suppressing transthyretin production in mice, monkeys and humans using 2nd-Generation antisense oligonucleotides. Amyloid. 2016;23:148–157. doi: 10.1080/13506129.2016.1191458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteleone G., Neurath M.F., Ardizzone S., Di Sabatino A., Fantini M.C., Castiglione F., Scribano M.L., Armuzzi A., Caprioli F., Sturniolo G.C. Mongersen, an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide, and Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1104–1113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteleone G., Di Sabatino A., Ardizzone S., Pallone F., Usiskin K., Zhan X., Rossiter G., Neurath M.F. Impact of patient characteristics on the clinical efficacy of mongersen (GED-0301), an oral Smad7 antisense oligonucleotide, in active Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;43:717–724. doi: 10.1111/apt.13526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raal F.J., Santos R.D., Blom D.J., Marais A.D., Charng M.J., Cromwell W.C., Lachmann R.H., Gaudet D., Tan J.L., Chasan-Taber S. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, for lowering of LDL cholesterol concentrations in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:998–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60284-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein E.A., Dufour R., Gagne C., Gaudet D., East C., Donovan J.M., Chin W., Tribble D.L., McGowan M. Apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibition with mipomersen in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess efficacy and safety as add-on therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2012;126:2283–2292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.104125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dowling J.J. Eteplirsen therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: skipping to the front of the line. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016;12:675–676. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Editorial (2016). Railroading at the FDA. Nat Biotechnol. 34, 1078. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Spiess M. The asialoglycoprotein receptor: a model for endocytic transport receptors. Biochemistry. 1990;29:10009–10018. doi: 10.1021/bi00495a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz A.L., Rup D., Lodish H.F. Difficulties in the quantification of asialoglycoprotein receptors on the rat hepatocyte. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:9033–9036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stockert R.J. The asialoglycoprotein receptor: relationships between structure, function, and expression. Physiol. Rev. 1995;75:591–609. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bareford L.M., Swaan P.W. Endocytic mechanisms for targeted drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007;59:748–758. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steirer L.M., Park E.I., Townsend R.R., Baenziger J.U. The asialoglycoprotein receptor regulates levels of plasma glycoproteins terminating with sialic acid alpha2,6-galactose. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:3777–3783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808689200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drickamer K. Ca2+-dependent carbohydrate-recognition domains in animal proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1993;3:393–400. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meier M., Bider M.D., Malashkevich V.N., Spiess M., Burkhard P. Crystal structure of the carbohydrate recognition domain of the H1 subunit of the asialoglycoprotein receptor. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:857–865. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz A.L., Fridovich S.E., Lodish H.F. Kinetics of internalization and recycling of the asialoglycoprotein receptor in a hepatoma cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:4230–4237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashwell G., Morell A.G. The role of surface carbohydrates in the hepatic recognition and transport of circulating glycoproteins. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1974;41:99–128. doi: 10.1002/9780470122860.ch3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolleshaug H., Berg T., Nilsson M., Norum K.R. Uptake and degradation of 125I-labelled asialo-fetuin by isolated rat hepatocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1977;499:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(77)90230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein J.L., Anderson R.G., Brown M.S. Coated pits, coated vesicles, and receptor-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 1979;279:679–685. doi: 10.1038/279679a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarkar M., Liao J., Kabat E.A., Tanabe T., Ashwell G. The binding site of rabbit hepatic lectin. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:3170–3174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolleshaug H., Berg T., Frölich W., Norum K.R. Intracellular localization and degradation of asialofetuin in isolated rat hepatocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1979;585:71–84. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90326-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baenziger J.U., Fiete D. Galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine-specific endocytosis of glycopeptides by isolated rat hepatocytes. Cell. 1980;22:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu G.Y., Wu C.H. Receptor-mediated in vitro gene transformation by a soluble DNA carrier system. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:4429–4432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu G.Y., Wu C.H. Receptor-mediated gene delivery and expression in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:14621–14624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu G.Y., Wu C.H. Evidence for targeted gene delivery to Hep G2 hepatoma cells in vitro. Biochemistry. 1988;27:887–892. doi: 10.1021/bi00403a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plank C., Zatloukal K., Cotten M., Mechtler K., Wagner E. Gene transfer into hepatocytes using asialoglycoprotein receptor mediated endocytosis of DNA complexed with an artificial tetra-antennary galactose ligand. Bioconjug. Chem. 1992;3:533–539. doi: 10.1021/bc00018a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merwin J.R., Noell G.S., Thomas W.L., Chiou H.C., DeRome M.E., McKee T.D., Spitalny G.L., Findeis M.A. Targeted delivery of DNA using YEE(GalNAcAH)3, a synthetic glycopeptide ligand for the asialoglycoprotein receptor. Bioconjug. Chem. 1994;5:612–620. doi: 10.1021/bc00030a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu G.Y., Wu C.H. Specific inhibition of hepatitis B viral gene expression in vitro by targeted antisense oligonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:12436–12439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hangeland J.J., Levis J.T., Lee Y.C., Ts’o P.O. Cell-type specific and ligand specific enhancement of cellular uptake of oligodeoxynucleoside methylphosphonates covalently linked with a neoglycopeptide, YEE(ah-GalNAc)3. Bioconjug. Chem. 1995;6:695–701. doi: 10.1021/bc00036a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biessen E.A., Sliedregt-Bol K., 'T Hoen P.A., Prince P., Van der Bilt E., Valentijn A.R., Meeuwenoord N.J., Princen H., Bijsterbosch M.K., Van der Marel G.A. Design of a targeted peptide nucleic acid prodrug to inhibit hepatic human microsomal triglyceride transfer protein expression in hepatocytes. Bioconjug. Chem. 2002;13:295–302. doi: 10.1021/bc015550g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rensen P.C., van Leeuwen S.H., Sliedregt L.A., van Berkel T.J., Biessen E.A. Design and synthesis of novel N-acetylgalactosamine-terminated glycolipids for targeting of lipoproteins to the hepatic asialoglycoprotein receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:5798–5808. doi: 10.1021/jm049481d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rohlff C., Watson S.A., Morris T.M., Skelton L., Jackman A.L., Page M.J. A novel, orally administered nucleoside analogue, OGT 719, inhibits the liver invasive growth of a human colorectal tumor, C170HM2. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1268–1272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seymour L.W., Ferry D.R., Anderson D., Hesslewood S., Julyan P.J., Poyner R., Doran J., Young A.M., Burtles S., Kerr D.J., Cancer Research Campaign Phase I/II Clinical Trials committee Hepatic drug targeting: phase I evaluation of polymer-bound doxorubicin. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:1668–1676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fiume L., Di Stefano G. Lactosaminated human albumin, a hepatotropic carrier of drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010;40:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iobst S.T., Drickamer K. Selective sugar binding to the carbohydrate recognition domains of the rat hepatic and macrophage asialoglycoprotein receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:6686–6693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rensen P.C., Sliedregt L.A., Ferns M., Kieviet E., van Rossenberg S.M., van Leeuwen S.H., van Berkel T.J., Biessen E.A. Determination of the upper size limit for uptake and processing of ligands by the asialoglycoprotein receptor on hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:37577–37584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101786200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khorev O., Stokmaier D., Schwardt O., Cutting B., Ernst B. Trivalent, Gal/GalNAc-containing ligands designed for the asialoglycoprotein receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:5216–5231. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baenziger J.U., Maynard Y. Human hepatic lectin. Physiochemical properties and specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:4607–4613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee Y.C., Townsend R.R., Hardy M.R., Lönngren J., Arnarp J., Haraldsson M., Lönn H. Binding of synthetic oligosaccharides to the hepatic Gal/GalNAc lectin. Dependence on fine structural features. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Biessen E.A., Beuting D.M., Roelen H.C., van de Marel G.A., van Boom J.H., van Berkel T.J. Synthesis of cluster galactosides with high affinity for the hepatic asialoglycoprotein receptor. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:1538–1546. doi: 10.1021/jm00009a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang Y.Y., Liang Z.C. Asialoglycoprotein Receptor and Its Application in Liver-targeted Drug Delivery. Prog Biochem Biophys. 2015;42:501–510. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nair J.K., Willoughby J.L., Chan A., Charisse K., Alam M.R., Wang Q., Hoekstra M., Kandasamy P., Kel’in A.V., Milstein S. Multivalent N-acetylgalactosamine-conjugated siRNA localizes in hepatocytes and elicits robust RNAi-mediated gene silencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:16958–16961. doi: 10.1021/ja505986a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rajeev K.G., Nair J.K., Jayaraman M., Charisse K., Taneja N., O’Shea J., Willoughby J.L., Yucius K., Nguyen T., Shulga-Morskaya S. Hepatocyte-specific delivery of siRNAs conjugated to novel non-nucleosidic trivalent N-acetylgalactosamine elicits robust gene silencing in vivo. ChemBioChem. 2015;16:903–908. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rajeev, K.G.Zimmermann, T., Manoharan, M., Maier., M., Kuchimanchi, S., and Charisse, K. (2013). Modified RNAi agents. U.S. Patent WO2013074974.

- 60.Maier, M., Foster, D., Milstein, S., Kuchimanchi, S., Jadhav, V.,Rajeev, K., Manoharan, M., and Parmar, R. (2016). Modified double-stranded RNA agents. U.S. Patent WO2016028649.

- 61.Parmar R., Willoughby J.L., Liu J., Foster D.J., Brigham B., Theile C.S., Charisse K., Akinc A., Guidry E., Pei Y. 5′-(E)-Vinylphosphonate: A Stable Phosphate Mimic Can Improve the RNAi Activity of siRNA-GalNAc Conjugates. ChemBioChem. 2016;17:985–989. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201600130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prakash T.P., Kinberger G.A., Murray H.M., Chappell A., Riney S., Graham M.J., Lima W.F., Swayze E.E., Seth P.P. Synergistic effect of phosphorothioate, 5′-vinylphosphonate and GalNAc modifications for enhancing activity of synthetic siRNA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:2817–2820. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alnylam. (2014). Advances in Delivery of RNAi Therapeutics with Enhanced Stabilization Chemistry (ESC)-GalNAc-siRNA Conjugates. http://www.alnylam.com/web/assets/Roundtable_ESC-GalNAc-Conjugates_072214.pdf.

- 64.Hawkins P.N., Ando Y., Dispenzeri A., Gonzalez-Duarte A., Adams D., Suhr O.B. Evolving landscape in the management of transthyretin amyloidosis. Ann. Med. 2015;47:625–638. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1068949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Butler J.S., Chan A., Costelha S., Fishman S., Willoughby J.L., Borland T.D., Milstein S., Foster D.J., Gonçalves P., Chen Q. 279 Preclinical evaluation of RNAi as a treatment for transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2016;23:109–118. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2016.1160882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sehgal A., Blomenkamp K.S., Qian K., Simon A., Haslett P., Barros S. Pre-Clinical Evaluation of ALN-AAT to Ameliorate Liver Disease Associated With Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficiency. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:S-975. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Henry S.P., Novotny W., Leeds J., Auletta C., Kornbrust D.J. Inhibition of coagulation by a phosphorothioate oligonucleotide. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997;7:503–510. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ferdinandi E.S., Vassilakos A., Lee Y., Lightfoot J., Fitsialos D., Wright J.A., Young A.H. Preclinical toxicity and toxicokinetics of GTI-2040, a phosphorothioate oligonucleotide targeting ribonucleotide reductase R2. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011;68:193–205. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1473-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moreno P.M., Pêgo A.P. Therapeutic antisense oligonucleotides against cancer: hurdling to the clinic. Front Chem. 2014;2:87. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alnylam. (2015). Alnylam R&D Day. http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/ABEA-430HSO/1862527561x0x865960/B08F6EC1-4FF6-48AD-A2E3-8CB626DE3B5D/RD_Day_2015_Full_Day_FINALnapdf.

- 71.Sehgal A., Barros S., Ivanciu L., Cooley B., Qin J., Racie T., Hettinger J., Carioto M., Jiang Y., Brodsky J. An RNAi therapeutic targeting antithrombin to rebalance the coagulation system and promote hemostasis in hemophilia. Nat. Med. 2015;21:492–497. doi: 10.1038/nm.3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morfini M., Zanon E. Emerging drugs for the treatment of hemophilia A and B. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs. 2016;21:301–313. doi: 10.1080/14728214.2016.1220536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strat A.L., Ghiciuc C.M., Lupuşoru C.E., Mitu F. NEW CLASS OF DRUGS: THERAPEUTIC RNAi INHIBITION OF PCSK9 AS A SPECIFIC LDL-C LOWERING THERAPY. Rev. Med. Chir. Soc. Med. Nat. Iasi. 2016;120:228–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gaudet D. Novel therapies for severe dyslipidemia originating from human genetics. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2016;27:112–124. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hill A., Taubel J., Bush J., Borodovsky A., Kawahata N., McLean H., Powell C., Chaturvedi P., Warner G., Garg P. A subcutaneously administered investigational RNAi therapeutic (ALN-CC5) targeting complement C5 for treatment of PNH and complement-mediated diseases: interim Phase 1 study results. Blood. 2015;126:2413. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liebow A., Li X., Racie T., Hettinger J., Bettencourt B.R., Najafian N., Haslett P., Fitzgerald K., Holmes R.P., Erbe D. An Investigational RNAi Therapeutic Targeting Glycolate Oxidase Reduces Oxalate Production in Models of Primary Hyperoxaluria. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030338. ASN.2016030338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carney E.F. Stones: A novel RNAi therapy for PH1. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016;12:508. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petersen J., Thompson A.J., Levrero M. Aiming for cure in HBV and HDV infection. J. Hepatol. 2016;65:835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maepa M.B., Roelofse I., Ely A., Arbuthnot P. Progress and prospects of anti-HBV gene therapy development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:17589–17610. doi: 10.3390/ijms160817589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yasuda M., Gan L., Chen B., Kadirvel S., Yu C., Phillips J.D., New M.I., Liebow A., Fitzgerald K., Querbes W., Desnick R.J. RNAi-mediated silencing of hepatic Alas1 effectively prevents and treats the induced acute attacks in acute intermittent porphyria mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:7777–7782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406228111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chan A., Liebow A., Yasuda M., Gan L., Racie T., Maier M., Kuchimanchi S., Foster D., Milstein S., Charisse K. Preclinical Development of a Subcutaneous ALAS1 RNAi Therapeutic for Treatment of Hepatic Porphyrias Using Circulating RNA Quantification. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2015;4:e263. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsuda S., Keiser K., Nair J.K., Charisse K., Manoharan R.M., Kretschmer P., Peng C.G., V Kel’in A., Kandasamy P., Willoughby J.L. siRNA conjugates carrying sequentially assembled trivalent N-acetylgalactosamine linked through nucleosides elicit robust gene silencing in vivo in hepatocytes. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015;10:1181–1187. doi: 10.1021/cb501028c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rozema D.B., Lewis D.L., Wakefield D.H., Wong S.C., Klein J.J., Roesch P.L., Bertin S.L., Reppen T.W., Chu Q., Blokhin A.V. Dynamic PolyConjugates for targeted in vivo delivery of siRNA to hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12982–12987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703778104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wong S.C., Klein J.J., Hamilton H.L., Chu Q., Frey C.L., Trubetskoy V.S., Hegge J., Wakefield D., Rozema D.B., Lewis D.L. Co-injection of a targeted, reversibly masked endosomolytic polymer dramatically improves the efficacy of cholesterol-conjugated small interfering RNAs in vivo. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2012;22:380–390. doi: 10.1089/nat.2012.0389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sebestyén M.G., Wong S.C., Trubetskoy V., Lewis D.L., Wooddell C.I. Targeted in vivo delivery of siRNA and an endosome-releasing agent to hepatocytes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1218:163–186. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1538-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rozema D.B., Blokhin A.V., Wakefield D.H., Benson J.D., Carlson J.C., Klein J.J., Almeida L.J., Nicholas A.L., Hamilton H.L., Chu Q. Protease-triggered siRNA delivery vehicles. J. Control. Release. 2015;209:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kanasty R., Dorkin J.R., Vegas A., Anderson D. Delivery materials for siRNA therapeutics. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:967–977. doi: 10.1038/nmat3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Varkouhi A.K., Scholte M., Storm G., Haisma H.J. Endosomal escape pathways for delivery of biologicals. J. Control. Release. 2011;151:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yuen M.F., Chan H.L.Y., Liu S.H.K., Given B., Schluep T., Hamilton J., Lai C.L., Locarnini S., Lau J.Y., Ferrari C., Gish R.G. ARC-520 produces deep and durable knockdown of viral antigens and DNA in a phase II study in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2015;62:1385A. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arrowhead. (2016). Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals Doses First Patient with Hepatitis B in Multiple Ascending Dose Portion of Phase 1/2 Study of ARC-521. http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/AMDA-2OTJP1/1862504966x0x907254/5730467A-2DC8-4079-97B0-195D1A96B95A/ARWR_News_2016_9_7_General_Releases.pdf.

- 91.Dicerna. (2016). Welcome to Investor Day. http://files.shareholder.com/downloads/AMDA-2IH3D0/3375799178x0x898098/D565497C-DCC6-40C5-91C7-60C010D9A346/DicernaInvestorDayJune292016.pdf.

- 92.Van der Ree M., de Vree M.L., Stelma F., Willemse S., van der Valk M., Rietdijk S., Molenkamp R., Schinkel J., Hadi S., Harbers M. A single subcutaneous dose of 2 mg/kg or 4 mg/kg of RG-101, a GalNAc-conjugated oligonucleotide with antagonist activity against miR-122, results in significant viral load reductions in chronic hepatitis C patients. J. Hepatol. 2015;62:S261. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vienberg S., Geiger J., Madsen S., Dalgaard L.T. MicroRNAs in Metabolism. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 2016 doi: 10.1111/apha.12681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Prakash T.P., Graham M.J., Yu J., Carty R., Low A., Chappell A., Schmidt K., Zhao C., Aghajan M., Murray H.F. Targeted delivery of antisense oligonucleotides to hepatocytes using triantennary N-acetyl galactosamine improves potency 10-fold in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:8796–8807. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pallan P.S., Allerson C.R., Berdeja A., Seth P.P., Swayze E.E., Prakash T.P., Egli M. Structure and nuclease resistance of 2′,4′-constrained 2′-O-methoxyethyl (cMOE) and 2′-O-ethyl (cEt) modified DNAs. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2012;48:8195–8197. doi: 10.1039/c2cc32286b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Prakash T.P., Yu J., Migawa M.T., Kinberger G.A., Wan W.B., Østergaard M.E., Carty R.L., Vasquez G., Low A., Chappell A. Comprehensive structure-activity relationship of triantennary N-acetylgalactosamine conjugated antisense oligonucleotides for targeted delivery to hepatocytes. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:2718–2733. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu R.Z., Graham M.J., Post N., Riney S., Zanardi T., Hall S., Burkey J., Shemesh C.S., Prakash T.P., Seth P.P. Disposition and Pharmacology of a GalNAc3-conjugated ASO Targeting Human Lipoprotein (a) in Mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e317. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2016.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yamamoto T., Wada F., Harada-Shiba M. Development of Antisense Drugs for Dyslipidemia. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2016;23:1011–1025. doi: 10.5551/jat.RV16001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]