Abstract

Lacosamide is an antiseizure agent that targets voltage-dependent sodium channels. Previous experiments have suggested that lacosamide is unusual in binding selectively to the slow-inactivated state of sodium channels, in contrast to drugs like carbamazepine and phenytoin, which bind tightly to fast-inactivated states. Using heterologously expressed human Nav1.7 sodium channels, we examined the state-dependent effects of lacosamide. Lacosamide induced a reversible shift in the voltage dependence of fast inactivation studied with 100-millisecond prepulses, suggesting binding to fast-inactivated states. Using steady holding potentials, lacosamide block was very weak at −120 mV (3% inhibition by 100 µM lacosamide) but greatly enhanced at −80 mV (43% inhibition by 100 µM lacosamide), where there is partial fast inactivation but little or no slow inactivation. During long depolarizations, lacosamide slowly (over seconds) put channels into states that recovered availability slowly (hundreds of milliseconds) at −120 mV. This resembles enhancement of slow inactivation, but the effect was much more pronounced at −40 mV, where fast inactivation is complete, but slow inactivation is not, than at 0 mV, where slow inactivation is maximal, more consistent with slow binding to fast-inactivated states than selective binding to slow-inactivated states. Furthermore, inhibition by lacosamide was greatly reduced by pretreatment with 300 µM lidocaine or 300 µM carbamazepine, suggesting that lacosamide, lidocaine, and carbamazepine all bind to the same site. The results suggest that lacosamide binds to fast-inactivated states in a manner similar to other antiseizure agents but with slower kinetics of binding and unbinding.

Introduction

Epilepsy is most commonly treated by drugs that inhibit voltage-dependent sodium channels, including carbamazepine, diphenyhydantoin, and lamotrogine (Rogawski and Löscher, 2004). All these “classic” sodium channel-blocking antiseizure drugs inhibit sodium channels in a state-dependent manner, with higher-affinity binding to the inactivated state of the channel than to the resting state (Catterall, 1999). Carbamazepine, diphenylhydantoin, and lamotrigine all appear to share the same binding site (Kuo, 1998), which has been localized to the pore of the sodium channel, formed by amino acid residues in the S6 regions of domains I, III, and IV (Ragsdale et al., 1994; 1996; Yarov-Yarovoy et al., 2001, 2002; reviewed by Catterall and Swanson, 2015).

Lacosamide is a relatively new antiseizure agent approved in the United States and Europe for adjuvant treatment of partial-onset seizures (Beyreuther et al., 2007; Cross and Curran, 2009; Rogawski et al., 2015). Lacosamide appears to act by sodium channel inhibition (Errington et al., 2008; Sheets et al., 2008; reviewed by Rogawaski et al., 2015); however, experiments examining the mechanism of lacosamide block of neuronal sodium channels have suggested that the interaction of lacosamide with sodium channels is fundamentally different from that of the classic antiepileptic drugs in that lacosamide appears to selectively bind to the slow-inactivated state of the channel (Errington et al., 2008; Sheets et al., 2008; Niespodziany et al., 2013), suggesting a different binding site and novel mode of action. Recently, Wang and Wang (2014) investigated lacosamide’s interaction with human cardiac Nav1.5 channels, which have less pronounced slow inactivation compared with neuronal channels (Richmond et al., 1998; O’Reilly et al., 1999). They found effective lacosamide block of cardiac sodium channels, including moderately strong open-channel block of channels modified to be inactivation-deficient, and, most surprisingly, they found that mutation of an S6 residue involved in the binding of local anesthetics completely eliminated lacosamide’s block of the channels, suggesting overlapping binding sites.

Because of these conflicting pictures of lacosamide’s interaction with neuronal and cardiac sodium channels, we have further examined lacosamide interaction with neuronal sodium channels using Nav1.7 channels, one of the isoforms in which previous experiments suggested binding to a slow-inactivated state (Sheets et al., 2008). Using protocols designed to distinguish between selective binding to slow-inactivated states and slow binding to fast-inactivated states, we conclude that interaction of lacosamide with Nav1.7 channels can best be explained in terms of slow binding to fast-inactivated states rather than selective binding to slow-inactivated states. Consistent with this, we find that binding of lidocaine or carbamazepine can prevent binding of lacosamide, consistent with a shared or overlapping binding site.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

Human embryonic kidney cell line 293 (HEK293) cells stably expressing human Nav1.7 channel (Liu et al., 2012) were grown in minimum essential medium (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma) under 5% CO2 at 37°C. For electrophysiological recording, cells were grown on coverslips for 12–24 hours after plating.

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell recordings were obtained using patch pipettes with resistances of 2–3.5 MΩ when filled with the internal solution, consisting of 61 mM CsF, 61 mM CsCl, 9 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM MgCl2, 9 mM EGTA, 14 mM creatine phosphate (Tris salt), 4 mM MgATP, and 0.3 mM GTP (Tris salt), 9 mM HEPES, pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. The shank of the electrode was wrapped with Parafilm (Sigma-Aldrich) to reduce capacitance and allow optimal series resistance compensation without oscillation. Seals were obtained and the whole-cell configuration established with cells in Tyrode’s solution consisting of 155 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. After establishing whole-cell recording, cells were lifted off the bottom of the recording chamber and placed in front of an array of quartz flow pipes (250-µm internal diameter, 350-µm external). Recordings were made using a base external solution of Tyrode’s solution with 10 mM tetraethylammonium chloride. Solution changes were made (in <1 second) by moving the cell between adjacent pipes. Lacosamide was purchased from AK Scientific (Union City, CA), and carbamazepine, diphenylhydantoin, lidocaine, and Brilliant Blue G (BBG) from Sigma.

The amplifier was tuned for partial compensation of series resistance (typically 70%–80% of a total series resistance of 4–10 MΩ), and tuning was periodically readjusted during the experiment. Currents were recorded at room temperature (21–23°C) with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Sunnyvale, CA) and filtered at 5 kHz with a low-pass Bessel filter. Currents were digitized using a Digidata 1322A data acquisition interface controlled by pClamp9.2 software (Axon Instruments, Molecular Devices) and analyzed using programs written in Igor Pro 6 (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR), using DataAccess (Bruxton Software, Seattle, WA) to read pClamp files into Igor Pro. Currents were corrected for linear capacitative and leak currents, which were determined using 5-mV hyperpolarizations delivered from the resting potential (usually −100 or −120 mV) and then appropriately scaled and subtracted. Data are given as mean ± S.E.M., and statistical significance was assessed using Student’s paired t test.

Results

Lacosamide Inhibition Is Potentiated at Depolarized Holding Potentials.

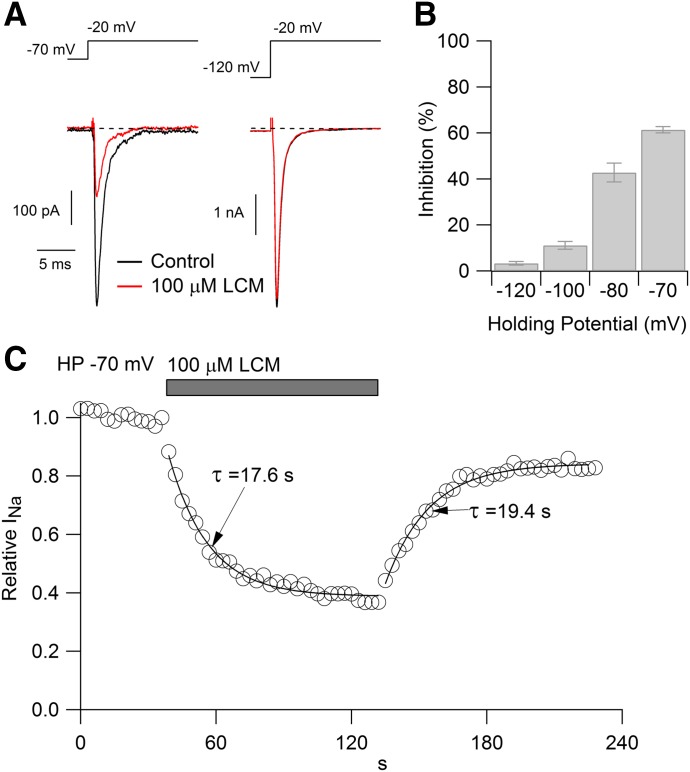

HEK293 cells expressing Nav1.7 channels were voltage clamped in the whole-cell configuration, and peak current was evoked by 30-millisecond test pulses to −20 mV delivered from steady holding potentials ranging from −70 to −120 mV. At a holding potential of −70 mV, near the typical resting potential of a neuron, 100 µM lacosamide reduced the sodium current by 61% ± 1% (Fig. 1A, left; n = 8). When cells were held at more hyperpolarized holding potentials, however, block was significantly less dramatic, producing inhibition by 43% ± 4% (n = 9) when tested from −80 mV, by 11% ± 2% (n = 6) from −100 mV, and by only 3% ± 1% (n = 9) when tested from −120 mV (Fig. 1A, right). The difference in blocking potency at the different holding potentials can be explained if lacosamide binds more tightly to the inactivated state of the Nav1.7 channel than to the closed “resting” state.

Fig. 1.

Lacosamide inhibition of Nav1.7 channels. (A) Effect of 100 μM lacosamide on current evoked at −20 mV when applied from a steady holding potential of −70 mV (left) or −120 mV (right). (B) Average inhibition (mean ± S.E.M.) by 100 μM lacosamide tested with steady holding potentials of −120 (n = 9), −100 (n = 6), −80 (n = 9), and −70 mV (n = 8). Lacosamide was applied for 30–60 seconds to reach steady-state block. (C) Time course of development and recovery from lacosamide applied at a holding potential of −70 mV (sodium current evoked by 30-millisecond test pulses to −20 mV delivered every second).

Figure 1C shows an example of the time course of lacosamide inhibition when tested with depolarizing pulses delivered from −70 mV. The time course of inhibition could be approximated reasonably well with a single exponential, with an average time constant of 22 ± 2.2 seconds (n = 8). Recovery from inhibition occurred with a similar time course, with an average time constant of 19 ± 2.7 seconds (n = 4). The onset and offset of lacosamide inhibition are far slower than that of lidocaine or carbamazepine, both of which inhibit and reverse within 1 or 2 seconds. This finding suggests that lacosamide binds and unbinds from channels much more slowly than either lidocaine or carbamazepine if it binds to the fast-inactivated state, as do lidocaine and carbamazepine; however, if lacosamide interacts preferentially with a slow-inactivated state, it is also possible that the slow kinetics reflect slow equilibration between this state and other states of the channel.

Lacosamide Shifts the Midpoint of the Fast Inactivation Curve

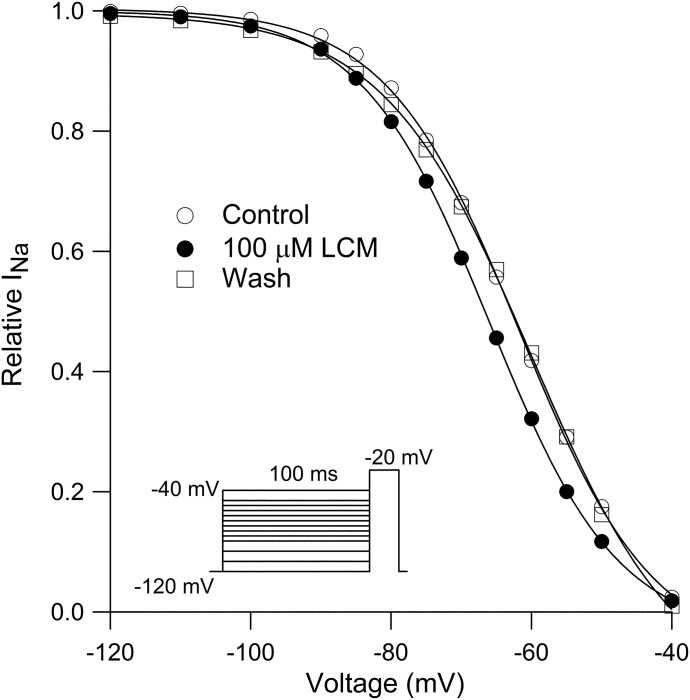

One of the most striking phenomenological differences previously reported between lacosamide and other classic anticonvulsants is that lacosamide was found to have no effect on the voltage dependence of the fast-inactivation curve (Sheets et al., 2008). We examined this point, determining the voltage dependence of fast inactivation using 100-millisecond steps to various voltages from −120 to −40 mV, followed by a test pulse to −20 mV. The voltage dependence of inactivation could be fit well by a Boltzmann function, and it was reversibly shifted in the hyperpolarizing direction in the presence of 100 µM lacosamide (Fig. 2). In 13 cells in which the fast-inactivation curve was determined in control and after application of 100 µM lacosamide, the midpoint shifted by an average of −9.1 ± 1.2 mV, from −60 ± 2 mV in control to −69 ± 1.9 mV in 100 µM lacosamide. There was little effect on the steepness of the curve, which had a slope factor of 9.4 ± 0.7 mV in control and 9.3 ± 0.3 mV in 100 µM lacosamide. These results suggested that lacosamide binds to the fast-inactivated state.

Fig. 2.

Reversible shift of the voltage dependence of fast inactivation by lacosamide. Sodium channel availability was assayed by a test step to −20 mV after a 100-millisecond prepulse to varying voltages. Prepulse-test pulse combinations were delivered at 5-second intervals to avoid use-dependent accumulation of lacosamide inhibition. Data in each condition were fit by the Boltzmann equation (1 + exp((V − Vh)/k)), where Vh is voltage of half-maximal inactivation, V is test potential, and k is the slope factor. Before lacosamide (open circles): Vh= −62 mV, after 100 μM lacosamide (filled circles): Vh = −66 mV, after washout (open squares): Vh= −60 mV.

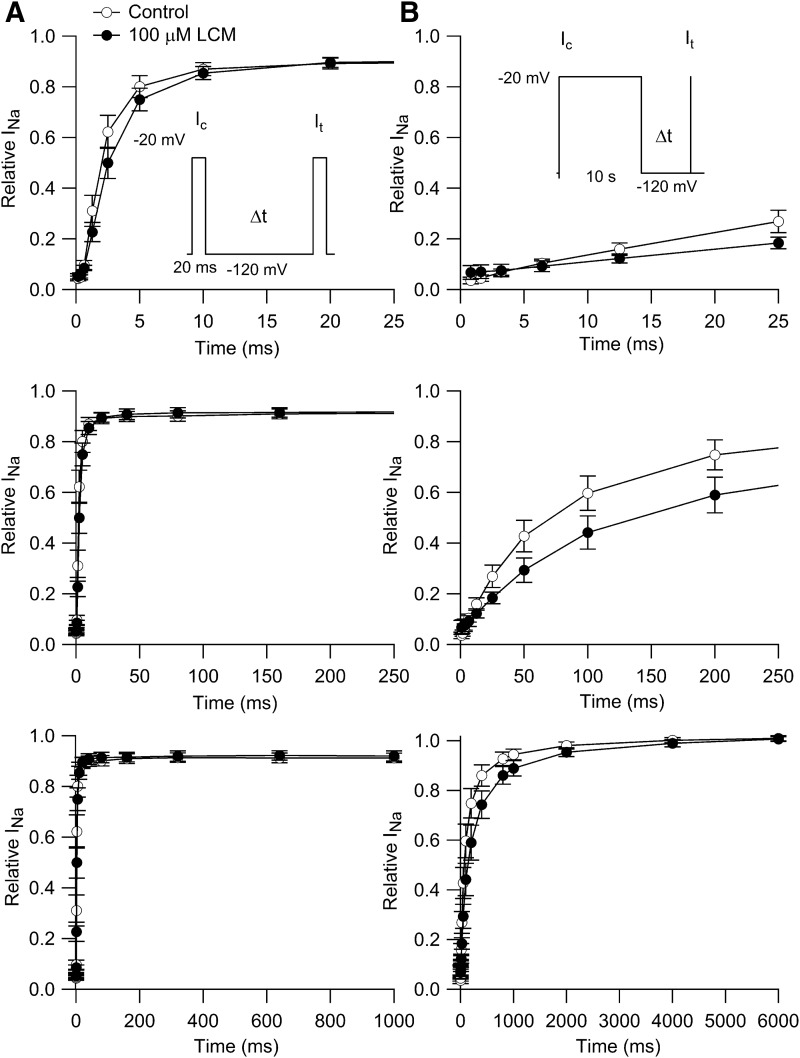

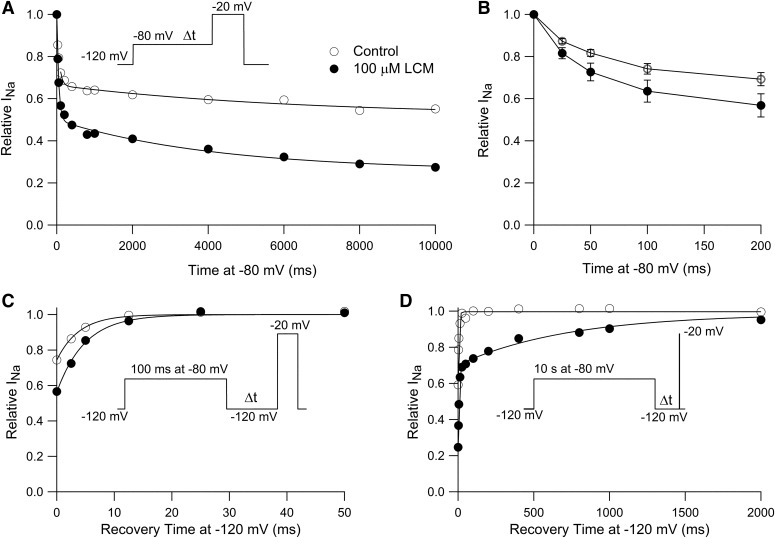

Lacosamide Slows Recovery from Inactivation

We next examined the effect of lacosamide on the time course of recovery from inactivation. In the first series of experiments (Fig. 3A), we examined recovery at a holding potential of −120 mV after a short (20-millisecond) prepulse to −20 mV. In control, the time course of recovery had a rapid phase plateauing at 92% recovery that was fit by a single exponential with a time constant of 2.5 ± 0.4 milliseconds (n = 7). Recovery was slightly slower in 100 µM lacosamide, but not dramatically, with a time constant of approximately 3.4 ± 0.5 ms (n = 7).

Fig. 3.

Effect of lacosamide on the time course of recovery from inactivation. (A) Inactivation was produced by a 20-millisecond conditioning pulse (Ic) to −20 mV, and recovery was assayed by a test pulse to −20 mV after a varying time (Δt) at −120 mV. Relative INa was calculated as It / Ic. Points and error bars show mean ±S.E.M. for experiments in seven cells, each with measurements in control and with 100 μM lacosamide. (B) Time course of recovery after a 10-second conditioning pulse to −20 mV, tested with a 20-millisecond test pulse to −20 mV at varying times after return of the voltage to −120 mV. Test currents were normalized to the largest current elicited by the step to −20 mV in each condition. Points and error bars show mean ± S.E.M. (n = 6).

After inactivation induced by a 10-second depolarization to −20 mV, recovery from inactivation had a biphasic time course in both control and with 100 µM lacosamide. Both phases of recovery were slower in lacosamide. In control, the initial phase comprised 73% ± 4% of the total and had a time constant of 88 ± 27 milliseconds, followed by a slower phase with a time constant of 650 ± 111 milliseconds (n = 7). In 100 µM lacosamide, the initial phase comprised 72% ± 1% of the total and had a time constant of 208 ± 68 millisecond, followed by a slow phase with a time constant of 1.9 ± 1 seconds (n = 7). Thus, both phases were two to three times slower in the presence of lacosamide.

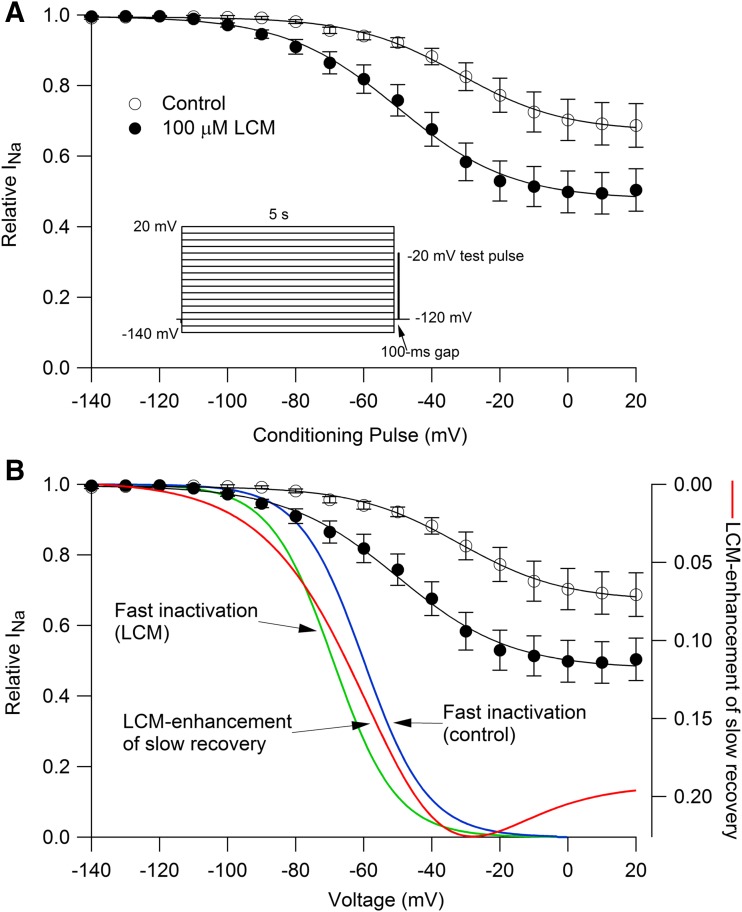

Voltage Dependence of Slowly Recovering Channels before and after Lacosamide

Lacosamide was proposed to inhibit sodium channels by binding selectively to slow-inactivated states (Errington et al., 2008; Sheets et al., 2008; Niespodziany et al., 2013). Figure 4 shows the effect of lacosamide using a voltage protocol that assays the fraction of channels that recovers from inactivation slowly. A 5-second prepulse to various voltages was followed by a 100-millisecond recovery interval at −120 mV to allow complete recovery from fast inactivation, followed by a test pulse to −20 mV (Fig. 4A). In control, 30% ± 6% of channels recovered slowly after a 5-second pulse to +20 mV, and the slowly recovering fraction of channels was increased to 50% ± 7% in 100 µM lacosamide (n = 7). Lacosamide also altered the voltage dependence with which channels entered the slowly recovering fraction. The voltage at which entry into slowly recovering states was half-maximal changed from −33 ± 4 mV in control (n = 7) to −50 ± 3 mV in 100 µM lacosamide (n = 7).

Fig. 4.

Enhancement of slowly recovering channels by lacosamide matches the voltage dependence of fast inactivation. (A) Slowly recovering fraction of channels after a 5-second conditioning depolarization to various voltages was assayed by a test pulse to −20 mV, delivered after 100-millisecond at −120 mV to allow recovery from fast inactivation. Sodium current was normalized to that with a conditioning pulse to −140 mV. Lacosamide enhanced the fraction of slowly recovering channels. Points and error bars show mean ± S.E.M. (n = 7). Data are fit by a modified Boltzmann equation (Carr et al., 2003): I/Imax = (1 − Iresid)/((1 + exp((Vm − Vh)/k)) + Iresid. Control: Vh= −33 ± 4 mV, k = 16 ± 2 mV, Iresid = 0.7 ± 0.06; lacosamide: Vh = −50 ± 3 mV; k = 15 ± 1.4 mV, Iresid = 0.5 ± 0.07. (B) The enhancement of the slowly recovering fraction of channels by lacosamide was calculated at each voltage as the difference between the fitted curves for control and lacosamide and is plotted (red curve, right-hand axis) versus conditioning voltage. The extra fraction of slowly recovering channels in lacosamide has a voltage dependence similar to that of fast inactivation. Curves for fast inactivation are drawn according to 1/(1 + exp((V−Vh)/k)), with Vh = −60 mV and k = 9.4 mV (blue, average values from experimental data for control, n = 13) and Vh = -69 mV and k = 9.3 mV (green, average values from experimental data with 100 μM lacosamide, n = 13).

There are two possible explanations for lacosamide enhancement of the slowly recovering fraction of channels. One is that lacosamide binds to the slow-inactivated state and thereby (by mass action) increases the total fraction of channels recovering slowly. This is the interpretation given previously. A second possible interpretation is that lacosamide binds to the fast-inactivated state and that lacosamide-bound fast-inactivated channels recover slowly. Both mechanisms can produce enhancement of slowly recovering fractions of channels and can be difficult to distinguish (Karoly et al., 2010). In our data, the voltage dependence with which lacosamide enhances the fraction of slowly-recovering channels seems more consistent with binding to fast-inactivated channels. If lacosamide bound to slow-inactivated channels (which are populated ∼5% after a 5-second pulse to −70 mV and ∼30% after a 5-second pulse to +20 mV), the enhancement of slowly recovering channels would increase monotonically with the fraction of channels in the slow-inactivated state in control. In fact, however, the lacosamide enhancement of the slowly recovering fraction (red curve in Fig. 4) was maximal for steps to near −30 mV, with less enhancement of slowly recovering channels for steps to more depolarized voltages. At −30 mV, where lacosamide enhancement of slowly recovery channels is maximal, fast inactivation has saturated but slow inactivation is not yet maximal. The voltage dependence of the lacosamide enhancement of slowly recovering channels is similar to the voltage dependence of fast inactivation (blue and green curves for control and with 100 µM lacosamide, respectively).

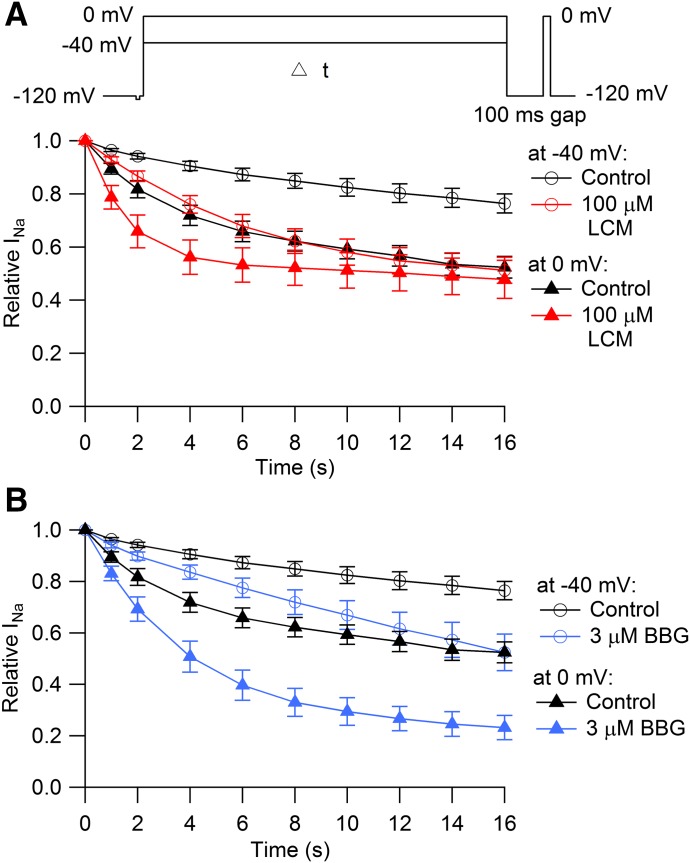

Time Course of Entry into Slowly-Recovering States

Next, we tested the kinetics with which channels enter into slowly recovering states in control and in the presence of lacosamide. Examination of kinetics can help distinguish slow binding to fast-inactivated channels from selective binding to slow-inactivated channels (Karoly et al., 2010). We compared the kinetics of entry into slowly recovering states at two different voltages: −40, where fast inactivation is complete but slow inactivation is not, and at 0 mV, where slow inactivation is maximal. At −40 mV in control, channels entered slowly recovering states relatively slowly, increasing to 24% ± 4% after 16 seconds at −40 mV. In the presence of 100 µM lacosamide, the fraction of slowly recovering channels at −40 mV doubled, increasing to 49% ± 5% after 16 seconds. At 0 mV in control, 48% ± 4% channels entered slowly recovering states after 16 seconds. Interestingly, with 100 µM lacosamide at 0 mV, there was little enhancement in the fraction of channels that reached slowly recovering states after 16 seconds at 0 mV (52% ± 7%); however, entry into slowly recovering states at 0 mV was substantially faster with 100 µM lacosamide (time constant of 2.0 ± 0.2 seconds) than in control (time constant of 3.5 ± 0.5 seconds, n = 6).

Thus, in the presence of lacosamide, the fraction of slowly recovering channels after 16 seconds is only slightly greater at 0 mV than at −40 mV, even though there is much more occupancy of slow-inactivated states in control at 0 mV compared with −40 mV. Also, the fraction of slowly recovering channels after 16 seconds at 0 mV is only slightly more in lacosamide (52%) than in control (49%), but the entry into slowly recovering states occurs faster in lacosamide. Both sets of observations suggest that the slowly recovering states in lacosamide result mainly from lacosamide binding to fast-inactivated states. The near lack of effect of lacosamide on the fraction of slowly recovering channels following long depolarizations to 0 mV is similar to results of Niespodziany et al. (2013), who saw little effect of lacosamide on the steady-state fraction of slowly recovering channels after 10-second depolarizations to +30 mV but dramatic enhancement for depolarizations near −80 to −60 mV.

Previously, we have analyzed interaction of the dye brilliant blue G (BBG) with sodium channels in the N1E-115 cell line (mainly Nav1.3 channels) and concluded that BBG binds with fairly high affinity to both rapidly and slow-inactivated states with higher affinity (Kd ∼0.2 µM) to slow-inactivated states than fast-inactivated states (Kd ∼5 µM) (Jo and Bean, 2011). BBG therefore offers a comparison with an agent that interacts most strongly with slow-inactivated states. Using the same protocol as in Fig. 5A, we analyzed the entry of channels into slowly recovering states in the presence of BBG. The results with BBG were strikingly different from those with lacosamide. BBG (3 µM) enhanced the slowly recovering fraction of channels after 16 seconds at 0 mV quite dramatically (from 48% ± 4% in control to 77% ± 5% in 3 µM BBG, n = 6), in contrast to the minimal steady-state effect of lacosamide at 0 mV. The different characteristics seen with lacosamide and BBG results seem consistent with BBG binding tightly to both slow-inactivated and fast-inactivated states and lacosamide binding mainly to fast-inactivated states.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of entry into slowly recovering states with lacosamide and BBG. (A) A step to either −40 or 0 mV varying in length from 1 to 16 seconds was given from a holding potential of −120 mV. A 100-millisecond interval at −120 mV then allowed for recovery of fast-inactivated channels, and the fraction of channels remaining in slowly recovering states was assayed by a pulse to 0 mV. Control, black symbols (n = 13); 100 μM lacosamide, red symbols (n = 6). (B) Entry into slowly recovering states at −40 mV and 0 mV with the same protocol, comparing control (black symbols, n = 13) and with 3 μM BBG (blue symbols, n = 6).

Rapid Component of Lacosamide Enhancement of Fast Iinactivation

The results shown in Fig. 5 show that lacosamide enhancement of slowly recovering channels develops relatively slowly, over seconds, suggesting relatively slow binding to inactivated states; however, lacosamide produced a hyperpolarizing shift of the inactivation curve determined by 100-millisecond prepulses, suggesting that there must be significant binding of lacosamide within 100 milliseconds. To explore this point further, we examined the time course with which lacosamide enhanced inactivation at −80 mV, a voltage at which inactivation is only partial and would be expected to reflect almost entirely fast-inactivated states. Figure 6A shows an experiment measuring the time course with which channels become unavailable during a step to −80 mV, as assayed by a test step to −20 mV. In control, the time course of inactivation developed with a biphasic time course. A fraction (34%) of the channels inactivated with a time constant of 62 milliseconds and a smaller fraction (14%) of channels inactivated with a slower time constant of 6279 milliseconds. In the presence of 100 µM lacosamide, the total fraction of channels that inactivated during the 10-second pulse increased from 48% to 72%, with increases in both the faster inactivating fraction (34% to 50%, time constant of 50 milliseconds in lacosamide) and the slower inactivating fraction (14% to 22%, time constant of 4183 seconds in lacosamide). In collected results from six cells, the total fraction of channels inactivating during 10 seconds at −80 mV increased from 42% ± 4% in control to 63% ± 6% in 100 μM lacosamide, with an increase in both the rapidly inactivating fraction from 33% ± 4% in control (with a time constant of 63 ± 4 milliseconds) to 44% ± 6% (with a time constant of 56 ± 5 milliseconds) in 100 μM lacosamide and also an increase in the slowly inactivating fraction, from 9% ± 1% in control (with time constant of 3003 ± 1226 milliseconds) to 19% ± 3% (with time constant of 4403 ± 737 milliseconds) in 100 μM lacosamide.

Fig. 6.

Fast component of lacosamide binding at −80 mV. (A) A step to −80 mV varying in length from 25 milliseconds to 10 seconds was given from a holding potential of −120 mV, and the fraction of available channels was assayed by a test pulse to −20 mV. Data are from a single example cell. Solid line was fit to control: 1–0.34*exp(−t/62 millisecond)−0.14*exp(−t/6279 milliseconds). Solid line was fit to the results with 100 μM lacosamide: 1–0.50*exp(−t/50 milliseconds)−0.22*exp(−t/4183 milliseconds). (B) Time course of inactivation at −80 mV; collected results are shown on an expanded time base for 25–200 milliseconds (mean ± S.E.M., n = 6; paired recordings in each cell in control and with 100 μM lacosamide). (C) Time course of recovery of channels after a 100-millisecond step to −80 mV in an example cell. Fitted solid curves are single exponential functions with time constants of 4.6 milliseconds in control and 5.3 milliseconds with 100 μM lacosamide. (D) Recovery of channels after a 10-second step to −80 mV [same cell as (C)]. Solid line was fit to control: 1-exp(−t/5.0 milliseconds). Solid line was fit to results with 100 μM lacosamide: 1–0.62exp(−t/7.1 milliseconds)–0.38exp(−t/727 milliseconds).

These results suggest that there is indeed a phase of rapid binding of lacosamide to inactivated channels, producing a loss of available channels within 100 milliseconds, consistent with the shift in the inactivation curve determined with 100-millisecond prepulses (Fig. 2). Figure 6B shows collected results for the time course of inactivation at −80 mV in the first 200 milliseconds at −80 mV. Lacosamide enhanced inactivation after a 100-millisecond prepulse to −80 mV from 26% ± 3% in control to 36% ± 5% with 100 μM lacosamide (n = 6, P = 0.016). In fact, lacosamide significantly enhanced inactivation even after a 25-millisecond prepulse to −80 mV, from 13% ± 1% in control to 18 ± 3% with 100 μM lacosamide (n = 6, P = 0.012).

These results suggest that, at least at −80 mV, lacosamide binds to channels with both a relatively fast phase, occurring within 25–100 milliseconds and a slower phase continuing over many seconds. In principle, these two phases of development of lacosamide inhibition might be associated with binding to distinct gating states of the channel. To examine this, we asked whether the two phases of lacosamide inhibition are associated with the same or different kinetics of recovery of available channels (Fig. 6, C and D). After 100-millisecond pulses to −80 mV, channels in control recovered with a time constant of 4.4 ± 0.6 milliseconds at −120 mV. In the presence of 100 μM lacosamide, the kinetics of recovery were only moderately slower, fit by an average time constant of 7.2 ± 2.2 milliseconds (n = 6). With 10-second prepulses to −80 mV, channels in control recovered with single rapid phase, fit by a single exponential with average time constant of 6.2 ± 0.8 milliseconds. In the presence of lacosamide, there was a biphasic time course of recovery, with 73% ± 3% of the channels recovering with a fast time constant of 6.3 ± 0.8 milliseconds and 27% ± 3% of the channels recovering with a much slower time course, with an average time constant of 788 ± 56 milliseconds (n = 6). These results suggest that at −80 mV, there is a fast phase of lacosamide binding occurring within 25–100 milliseconds, producing a state from which channel recovery is rapid, only slightly slower than recovery from the normal inactivated state. A slower phase of continuing binding of lacosamide occurring over seconds then produces occupancy of a different state from which recovery is far slower.

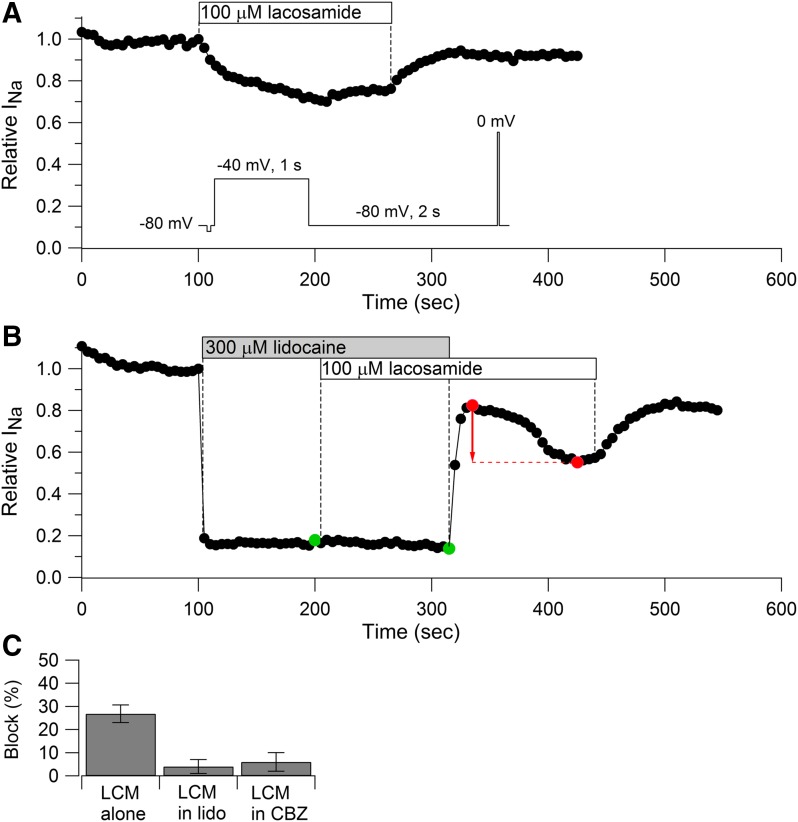

Lidocaine or Carbamazepine Prevents the Nav1.7 Current Inhibition by Lacosamide

Next, we tested whether lacosamide binds to the same binding site as lidocaine and carbamazepine, which interact with a common binding site in the pore region involving S6 segments from D1, D3, and D4 (Ragsdale et al., 1994, 1996; Yarov-Yarovoy et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2010). The experiment was designed to test whether lidocaine or carbamazepine binding prevents lacosamide binding. Figure 7 shows the experimental protocol using lidocaine and lacosamide. If lacosamide binds to a site independent of lidocaine, then the degree of block by lacosamide should be the same regardless of previous occupancy by lidocaine that produced partial block. For example, if half the channels are occupied by lidocaine, the addition of lacosamide will result in binding to both lidocaine-bound and lidocaine-free channels to exactly the same extent and will reduce the current by exactly the same percentage as if it were added to channels in the absence of lidocaine. On the other hand, if lacosamide binds to the same site as lidocaine, lacosamide will be unable to bind to channels already occupied by lidocaine, and the percentage reduction in current will be less than if lacosamide were applied alone. The experiment used a voltage protocol in which binding of both lidocaine and lacosamide was enhanced by 1-second pulses to −40 mV, delivered every 3 seconds, with a steady holding voltage of −80 mV and using a test pulse to 0 mV to assay the fraction of unblocked channels. With this protocol, 100 μM lacosamide alone (Fig. 7A) reduced current by an average of 27% ± 4% (n = 6) after a minute, inhibiting with a relatively slow time course. Application of 300 μM lidocaine alone reduced current almost immediately (within 3 seconds) and inhibited current by an average of 77% ± 3% (n = 6). When 100 μM lacosamide was applied on top of lidocaine, there was almost no additional inhibition (inhibition of 4% ± 3%, n = 5, measured relative to the current in lidocaine just before the addition of lacosamide). When lidocaine was removed in the continuing presence of lacosamide, the current recovered immediately, followed by a reduction occurring over about a minute. Our interpretation of this time course is that lidocaine prevents lacosamide binding, and when lidocaine is removed, producing initial rapid recovery, lacosamide can then bind to produce the delayed phase of inhibition (red arrow). The delayed phase of inhibition after washout of lidocaine was seen in each of four cells in which the time course of lidocaine washout was successfully obtained. This delayed phase of lacosamide inhibition seen after lidocaine is removed offers strong evidence that lidocaine prevents the binding of lacosamide when both are present.

Fig. 7.

Lidocaine and carbamazepine occlude inhibition by lacosamide. (A) Time course of sodium current inhibition by 100 μM lacosamide while applying a protocol in which lacosamide binding is facilitated by a 1-second prepulse to −40 mV and assayed by a test pulse to 0 mV delivered from a steady-holding potential of −80 mV (inset). (B) The same protocol was applied while first applying 300 μM lidocaine alone and then 100 μM lacosamide in the continued presence of lidocaine. Lacosamide had little blocking effect in the presence of lidocaine (green symbols). After lidocaine was removed, lacosamide appeared to produce block (red symbols). (C) Collected results for current inhibition by 100 μM lacosamide applied alone (27% ± 4%, n = 6) or in the presence of 300 μM lidocaine (4% ± 3%, n = 5, measured relative to current in lidocaine alone just before the addition of lacosamide) or in the presence of 300 μM carbamazepine (6% ± 4%, n = 4, measured relative to current in carbamazepine alone just before addition of lacosamide). Block by lacosamide was measured after a 1-minute application in each case.

This experiment indicates that lacosamide binding is largely prevented when channels are occupied by lidocaine. The simplest interpretation is that lacosamide binds to the same site as lidocaine. We obtained very similar results using the same protocol with carbamazepine and lacosamide. When applied in the presence of 300 μM carbamazepine, 100 μM lacosamide produced only 6% ± 4% inhibition (n = 4, relative to current in carbamazepine alone just before the addition of lacosamide) compared with 27% ± 4% with lacosamide alone (n = 6). The delayed phase of inhibition after washout of carbamazepine in the continuing presence of lacosamide was also evident in these experiments.

Discussion

Our results suggest that lacosamide binds tightly to fast-inactivated states of voltage-dependent sodium channels rather than binding exclusively or preferentially to slow-inactivated states. The evidence includes the following: 1) lacosamide shifts the voltage dependence of fast inactivation (determined by 100-millisecond prepulses) in the hyperpolarizing direction; 2) lacosamide inhibition is strongly enhanced at a holding potential of −80 mV, where a fraction of channels are in fast-inactivated states but there is no apparent slow inactivation; 3) lacosamide enhances the fraction of slowly recovering channels more at −40 mV (where fast inactivation is complete, but slow inactivation is not) than at 0 mV (where a larger fraction of channels is in slow-inactivated states); 4) with long prepulses to 0 mV, the fraction of channels in slowly recovering states was only slightly increased by lacosamide, but the rate of entry into these states (a combination of drug-free slow-inactivated states and slowly recovering drug-bound channels) was faster, results inconsistent with selective lacosamide binding to slow-inactivated states, which would be rate-limited by the formation of slow-inactivated states; 5) lacosamide binding can be prevented by lidocaine and carbamazepine, which bind to fast-inactivated states (Karoly et al., 2010).

The small shift induced by lacosamide in the rapidly inactivation curve was not evident in a previous study with Nav1.7 channels (Sheets et al., 2008), probably because unpaired population comparisons were made and the small shift we saw might well be obscured. An effect of lacosamide on the fast-inactivation curve has also been recently reported for channels in N1E-115 cells (Hebeisen et al., 2015) and cloned Nav1.2 channels coexpressed with β1 subunits (Abdelsayed et al., 2013).

The terminology binds to the fast-inactivated state for drugs like lidocaine and lacosamide is convenient but imprecise. A more precise view is that the binding site for drugs like lidocaine is formed or revealed when channels undergo activation (i.e., S4 segments of the pseudosubunits move from more internal to more external positions) (Vedantham and Cannon, 1999; Sheets and Hanck, 2007; Fozzard et al., 2011). These S4 movements promote inactivation (Kuo and Bean, 1994a; Ahern et al., 2016), so the voltage dependence and kinetics of formation of the high-affinity binding site for drugs like lidocaine roughly parallels the development of inactivation, even though inactivation per se is not required for high-affinity drug binding (Wang et al., 2004).

Lacosamide binding may actually hinder entry of channels into slow-inactivated states. There was almost no enhancement by lacosamide of the total fraction of slowly recovering channels after a 16-second depolarization to 0 mV, where slow inactivation in control is maximal but only about 50%. Even without lacosamide binding to slow-inactivated states, one might expect binding to fast-inactivated states to increase the total slowly recovering fraction by introducing a new slowly recovering fraction of channels, unless binding to fast-inactivated states reduces entry into slowly activated states. Interestingly, Sheets and colleagues (2011) discovered that the interaction of lidocaine with Nav1.7 channels does hinder the transition to slow inactivation (although not preventing it completely). Our data suggest that lacosamide binding may also hinder entry into slow-inactivated states.

The ability of pre-exposure to lidocaine to prevent binding of lacosamide (Fig. 7) is most simply interpreted as direct competition for binding to the same site. In principle, the effect could be less direct, for example, if lacosamide binding required slow-inactivated channels and these states were not formed in the presence of lidocaine; however, additional evidence for lacosamide binding to the same site as lidocaine comes from recent experiments (Wang and Wang, 2014) showing reduced lacosamide inhibition of human cardiac sodium channels with a D4S6 mutation that also reduces inhibition by lidocaine, carbamazepine, and phenytoin (Ragsdale et al., 1994; Ahern et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2010). For all these drugs, it appears that binding to the resting state of the channel is very weak and that a high-affinity binding site is formed when channels are depolarized. The key difference is the rate of binding to this site, which is far slower with lacosamide than for lidocaine, carbamazepine, or other sodium channel-inhibiting antiepileptic drugs like phenytoin or lamotrigine (Kuo and Bean, 1994b; Qiao et al., 2014).

The shift in the inactivation curve determined by 100-millisecond prepulses implies significant binding of lacosamide within 100 milliseconds, even though lacosamide induction of slowly recovering states of the channel developed much more slowly, over many seconds. Indeed, the results in Fig. 6 show a rapid phase with which lacosamide produced nonavailable channels at −80 mV. This channel state recovered availability quickly (time constant of ∼7 milliseconds at −120 mV), in contrast to a state produced by lacosamide binding over many seconds at −80 mV, which recovered slowly (time constant of ∼800 millisecond). The slowly recovering state is unlikely to represent lacsoamide binding to slow inactivated channels because in control, no evidence of slowly recovering channels was seen at −80 mV, even after long (10-second) pulses. In principle, tight binding of lacosamide to slow-inactivated states could shift the voltage dependence of slow inactivation enough to induce apparent slow inactivation where none was evident in control, but this seems unlikely because of the minimal enhancement by lacosamide of slowly recovering states with long depolarization at 0 mV, where in control, a large fraction of channels enter slow-inactivated states. Therefore, the slowly recovering channels induced by slow lacosamide binding at −80 mV most likely represent slow recovery from lacosamide-bound fast-inactivated states.

Fast inactivation of the sodium channel involves movement of the cytoplasmic loop linking pseudosubunit domains III and IV (III-IV linker) to occlude the inner-pore region (Stühmer et al., 1989; Patton et al., 1992; West et al., 1992; Ahern et al., 2016). This occlusion probably prevents compounds like lidocaine and lacosamide from entering and exiting the intracellular mouth of the pore when the channel is inactivated. An alternative pathway for entry and exit to the binding site in the pore may be provided by a “fenestration” noted in the protein structure of a bacterial sodium channel (Payandeh et al., 2011), which could allow access to the channel pore by entry of hydrophobic drugs directly from the lipid membrane, as earlier proposed for the neutral form of lidocaine (Hille, 1977) based on kinetics of inhibition and recovery. An interesting possibility is that the fast phase of lacosamide binding at −80 mV represents binding of lacosamide to pre-open partially activated but non-inactivated states, with rapid direct access through the non-occluded intracellular end of the pore, and that the slow phase of lacosamide binding represents interaction with channels in which the III-IV linker has occluded the intracellular mouth of the pore so that lacosamide has to enter and exit the channel through the side fenestration. The possibility that lacosamide can bind and unbind from pre-open partially-activated but non-inactivated states is in good agreement with the results of Wang and Wang (2014) showing such binding to pre-open states in inactivation-deficient Nav1.5 channels.

Despite the existence of a fast-binding and fast-unbinding pathway for lacosamide that accounts for the small shift in the fast-inactivation curve, the slow binding and unbinding processes are likely much more significant for lacosamide inhibition under most circumstances. Since the state produced by fast binding also recovers availability fast, it is unlikely to contribute to use-dependent block with repetitive firing, which develops very slowly (Errington et al., 2008), and when applied at a steady holding voltage of −70 mV, near a normal resting potential, lacosamide inhibition developed slowly, with a time constant of ∼20 seconds, suggesting that slow-binding pathways are most important. In contrast, with the same protocol, lidocaine inhibition develops far faster, within a few seconds, and also reverses similarly rapidly (data not shown).

An extensive series of compounds related to lacosamide has been developed and has a considerable range of kinetics of state-dependent interactions with sodium channels (Wang et al., 2011a,b; Lee et al., 2014; Park et al., 2015). Systematically comparing the kinetics of state-dependent binding and unbinding of this series with their structural differences may offer insight into molecular mechanisms, for example, exploring the hypothesis that the speed of binding and unbinding to inactivated channels could reflect structural constraints on movement of different-sized molecules through a side fenestration in the channel.

Although our data suggest that lacosamide binds to the same channel states and the same binding site as anticonvulsants like carbamazepine, the much slower binding and unbinding of lacosamide could result in very different modification of neuronal firing. This was clear from the previous experiments showing that lacosamide has much less dramatic frequency-dependent reduction of sodium current or action potentials than carbamazepine (Errington et al., 2008), presumably because lacosamide binding is so much slower. The most effective means of enhancing lacosamide inhibition is long, steady depolarizations rather than high-frequency action potential firing (Errington et al., 2008), which is equally well explained by slow binding to fast-inactivated states as by selective binding to slow-inactivated states. Because fast inactivation occurs for much smaller depolarizations than slow inactivation, a mechanism based on slow binding to fast-inactivated states rather than selective binding to slow-inactivated states would require smaller depolarizations of membrane potential to produce substantial inhibition, possibly a favorable feature for disrupting pathologic neuronal activity.

Abbreviations

- BBG

Brilliant Blue G

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney cell line 293

Authorship Contributions

Research design: Jo, Bean.

Conducted experiments: Jo.

Performed data analysis: Jo, Bean.

Wrote manuscript: Jo, Bean.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurologic Diseases and Stroke [Grants NS064274, NS072040, and NS036855].

References

- Abdelsayed M, Sokolov S, Ruben PC. (2013) A thermosensitive mutation alters the effects of lacosamide on slow inactivation in neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels, NaV1.2. Front Pharmacol 4:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern CA, Eastwood AL, Dougherty DA, Horn R. (2008) Electrostatic contributions of aromatic residues in the local anesthetic receptor of voltage-gated sodium channels. Circ Res 102:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern CA, Payandeh J, Bosmans F, Chanda B. (2016) The hitchhiker’s guide to the voltage-gated sodium channel galaxy. J Gen Physiol 147:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyreuther BK, Freitag J, Heers C, Krebsfänger N, Scharfenecker U, Stöhr T. (2007) Lacosamide: a review of preclinical properties. CNS Drug Rev 13:21–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. (1999) Molecular properties of brain sodium channels: an important target for anticonvulsant drugs. Adv Neurol 79:441–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Swanson TM. (2015) Structural basis for pharmacology of voltage-gated Sodium and Calcium Channels. Mol Pharmacol 88:141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, Day M, Cantrell AR, Held J, Scheuer T, Catterall WA, Surmeier DJ. (2003) Transmitter modulation of slow, activity-dependent alterations in sodium channel availability endows neurons with a novel form of cellular plasticity. Neuron 39:793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SA, Curran MP. (2009) Lacosamide: in partial-onset seizures. Drugs 69:449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington AC, Stöhr T, Heers C, Lees G. (2008) The investigational anticonvulsant lacosamide selectively enhances slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels. Mol Pharmacol 73:157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozzard HA, Sheets MF, Hanck DA. (2011) The sodium channel as a target for local anesthetic drugs. Front Pharmacol 2:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebeisen S, Pires N, Loureiro AI, Bonifácio MJ, Palma N, Whyment A, Spanswick D, Soares-da-Silva P. (2015) Eslicarbazepine and the enhancement of slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels: a comparison with carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine and lacosamide. Neuropharmacology 89:122–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. (1977) Local anesthetics: hydrophilic and hydrophobic pathways for the drug-receptor reaction. J Gen Physiol 69:497–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S, Bean BP. (2011) Inhibition of neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels by brilliant blue G. Mol Pharmacol 80:247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karoly R, Lenkey N, Juhasz AO, Vizi ES, Mike A. (2010) Fast- or slow-inactivated state preference of Na+ channel inhibitors: a simulation and experimental study. PLOS Comput Biol 6:e1000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CC. (1998) A common anticonvulsant binding site for phenytoin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine in neuronal Na+ channels. Mol Pharmacol 54:712–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CC, Bean BP. (1994a) Na+ channels must deactivate to recover from inactivation. Neuron 12:819–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CC, Bean BP. (1994b) Slow binding of phenytoin to inactivated sodium channels in rat hippocampal neurons. Mol Pharmacol 46:716–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Park KD, Torregrosa R, Yang XF, Dustrude ET, Wang Y, Wilson SM, Barbosa C, Xiao Y, Cummins TR, et al. (2014) Substituted N-(biphenyl-4′-yl)methyl (R)-2-acetamido-3-methoxypropionamides: potent anticonvulsants that affect frequency (use) dependence and slow inactivation of sodium channels. J Med Chem 57:6165–6182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Jo S, Bean BP. (2012) Modulation of neuronal sodium channels by the sea anemone peptide BDS-I. J Neurophysiol 107:3155–3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niespodziany I, Leclère N, Vandenplas C, Foerch P, Wolff C. (2013) Comparative study of lacosamide and classical sodium channel blocking antiepileptic drugs on sodium channel slow inactivation. J Neurosci Res 91:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly JP, Wang SY, Kallen RG, Wang GK. (1999) Comparison of slow inactivation in human heart and rat skeletal muscle Na+ channel chimaeras. J Physiol 515:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KD, Yang XF, Dustrude ET, Wang Y, Ripsch MS, White FA, Khanna R, Kohn H. (2015) Chimeric agents derived from the functionalized amino acid, lacosamide, and the α-aminoamide, safinamide: evaluation of their inhibitory actions on voltage-gated sodium channels, and antiseizure and antinociception activities and comparison with lacosamide and safinamide. ACS Chem Neurosci 6:316–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton DE, West JW, Catterall WA, Goldin AL. (1992) Amino acid residues required for fast Na(+)-channel inactivation: charge neutralizations and deletions in the III-IV linker. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:10905–10909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payandeh J, Scheuer T, Zheng N, Catterall WA. (2011) The crystal structure of a voltage-gated sodium channel. Nature 475:353–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X, Sun G, Clare JJ, Werkman TR, Wadman WJ. (2014) Properties of human brain sodium channel α-subunits expressed in HEK293 cells and their modulation by carbamazepine, phenytoin and lamotrigine. Br J Pharmacol 171:1054–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. (1994) Molecular determinants of state-dependent block of Na+ channels by local anesthetics. Science 265:1724–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale DS, McPhee JC, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. (1996) Common molecular determinants of local anesthetic, antiarrhythmic, and anticonvulsant block of voltage-gated Na+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:9270–9275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JE, Featherstone DE, Hartmann HA, Ruben PC. (1998) Slow inactivation in human cardiac sodium channels. Biophys J 74:2945–2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogawski MA, Löscher W. (2004) The neurobiology of antiepileptic drugs. Nat Rev Neurosci 5:553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogawski MA, Tofighy A, White HS, Matagne A, Wolff C. (2015) Current understanding of the mechanism of action of the antiepileptic drug lacosamide. Epilepsy Res 110:189–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets MF, Hanck DA. (2007) Outward stabilization of the S4 segments in domains III and IV enhances lidocaine block of sodium channels. J Physiol 582:317–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets PL, Heers C, Stoehr T, Cummins TR. (2008) Differential block of sensory neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels by lacosamide [(2R)-2-(acetylamino)-N-benzyl-3-methoxypropanamide], lidocaine, and carbamazepine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 326:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets PL, Jarecki BW, Cummins TR. (2011) Lidocaine reduces the transition to slow inactivation in Na(v)1.7 voltage-gated sodium channels. Br J Pharmacol 164 (2b):719–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stühmer W, Conti F, Suzuki H, Wang XD, Noda M, Yahagi N, Kubo H, Numa S. (1989) Structural parts involved in activation and inactivation of the sodium channel. Nature 339:597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedantham V, Cannon SC. (1999) The position of the fast-inactivation gate during lidocaine block of voltage-gated Na+ channels. J Gen Physiol 113:7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GK, Russell C, Wang SY. (2004) Mexiletine block of wild-type and inactivation-deficient human skeletal muscle hNav1.4 Na+ channels. J Physiol 554:621–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GK, Wang SY. (2014) Block of human cardiac sodium channels by lacosamide: evidence for slow drug binding along the activation pathway. Mol Pharmacol 85:692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Park KD, Salome C, Wilson SM, Stables JP, Liu R, Khanna R, Kohn H. (2011a) Development and characterization of novel derivatives of the antiepileptic drug lacosamide that exhibit far greater enhancement in slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels. ACS Chem Neurosci 2:90–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wilson SM, Brittain JM, Ripsch MS, Salomé C, Park KD, White FA, Khanna R, Kohn H. (2011b) Merging structural motifs of functionalized amino acids and α-aminoamides results in novel anticonvulsant compounds with significant effects on slow and fast inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels and in the treatment of neuropathic pain. ACS Chem Neurosci 2:317–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West JW, Patton DE, Scheuer T, Wang Y, Goldin AL, Catterall WA. (1992) A cluster of hydrophobic amino acid residues required for fast Na(+)-channel inactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:10910–10914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YC, Huang CS, Kuo CC. (2010) Lidocaine, carbamazepine, and imipramine have partially overlapping binding sites and additive inhibitory effect on neuronal Na+ channels. Anesthesiology 113:160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarov-Yarovoy V, Brown J, Sharp EM, Clare JJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. (2001) Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent gating and binding of pore-blocking drugs in transmembrane segment IIIS6 of the Na(+) channel alpha subunit. J Biol Chem 276:20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarov-Yarovoy V, McPhee JC, Idsvoog D, Pate C, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. (2002) Role of amino acid residues in transmembrane segments IS6 and IIS6 of the Na+ channel alpha subunit in voltage-dependent gating and drug block. J Biol Chem 277:35393–35401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]