Abstract

Introduction

Chemokine receptor-4 (CXCR4, fusin, CD184) is expressed on several tissues involved in immune regulation and is upregulated in many diseases including malignant gliomas. A radiolabeled small molecule that readily crosses the blood-brain barrier can aid in identifying CXCR4-expressing gliomas and monitoring CXCR4-targeted therapy. In the current work, we have synthesized and evaluated an [18F]-labeled small molecule based on a pyrimidine-pyridine amine for its ability to target CXCR4.

Experimental

The nonradioactive standards and the nitro precursor used in this study were prepared using established methods. An HPLC method was developed to separate the nitro-precursor from the nonradioactive standard and radioactive product. The nitro-precursor was radiolabeled with 18F under inert, anhydrous conditions using the [18F]-kryptofix 2.2.2 complex to form the desired N-(4-(((6-[18F]fluoropyridin-2-yl)amino)methyl)benzyl)pyrimidin-2-amine ([18F]-3). The purified radiolabeled compound was used in serum stability, partition coefficient, cellular uptake, and in vivo cancer targeting studies.

Results

[18F]-3 was synthesized in 4–10% decay-corrected yield (to start of synthesis). [18F]-3 (tR ≈ 27 min) was separated from the precursor (tR ≈ 30 min) using a pentafluorophenyl column with an isocratic solvent system. [18F]-3 displayed acceptable serum stability over 2 h. The amount of [18F]-3 bound to the plasma proteins was determined to be > 97%. The partition coefficient (LogD7.4) is 1.4 ± 0.5. Competitive in vitro inhibition indicated 3 does not inhibit uptake of 67Ga-pentixafor. Cell culture media incubation and ex vivo urine analysis indicate rapid metabolism of [18F]-3 into hydrophilic metabolites. Thus, in vitro uptake of [18F]-3 in CXCR4 over-expressing U87 cells (U87 CXCR4) and U87 WT indicated no specific binding. In vivo studies in mice bearing U87 CXCR4 and U87 WT tumors on the left and right shoulders were carried out using [18F]-3 and 68Ga-pentixafor on consecutive days. The CXCR4 positive tumor was clearly visualized in the PET study using 68Ga-pentixafor, but not with [18F]-3.

Conclusions

We have successfully synthesized both a radiolabeled analog to previously reported CXCR4-targeting molecules and a nitro precursor. Our in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that [18F]-3 is rapidly metabolized and, therefore, does not target CXCR4-expressing tumors. Optimization of the structure to improve the in vivo (and in vitro) stability, binding, and solubility could lead to an appropriate CXCR4-targeted radiodiagnositic molecule.

Keywords: 18F, radiosynthesis, CXCR4, dipyrimidine amine, pyrimidine-pyridine amine

Introduction

Chemokine receptor-4 (CXCR4, fusin, CD184) is a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) that functions as an immunomodulatory receptor. It is expressed on several tissues involved in immune regulation, including bone marrow, spleen, CD4+ T cells and is specific for its ligand CX-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12, SDF-1) [1–5]. Binding of CXCL12 to CXCR4 leads to downstream activation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways leading to survival, proliferation, and other chemotactic functions [6, 7]. CXCR4 overexpression has been observed in several diseases including different cancers, rheumatoid arthritis, and post-traumatic stress disorder [1–5].

CXCR4 expression has been shown to be upregulated in gliomas with expression correlating with tumor grade [8]. Targeting CXCR4 with positron-emitting radiopharmaceuticals that penetrate an intact blood-brain barrier (BBB) could provide clinicians with a diagnostic tool necessary for identifying CXCR4+ gliomas and monitoring anti-CXCR4 based therapies. Currently, the only FDA-approved drug that targets CXCR4 is plerixafor. Unfortunately, attempts to radiolabel plerixafor with 64Cu for PET imaging agents have resulted in compounds with reduced affinity for CXCR4 [9–12]. Another radiopharmaceutical undergoing clinical investigation is 68Ga-pentixafor, a 68Ga labeled pentapeptide that binds to CXCR4 [13–15]. Studies have shown the utility of this tracer in imaging CXCR4 positive tumors, but the peptide-based agent would be unable to penetrate an intact BBB. Thus, it would be useful to identify alternative molecules, with better BBB penetrating properties, that can be labeled with radiohalogens and that can target CXCR4.

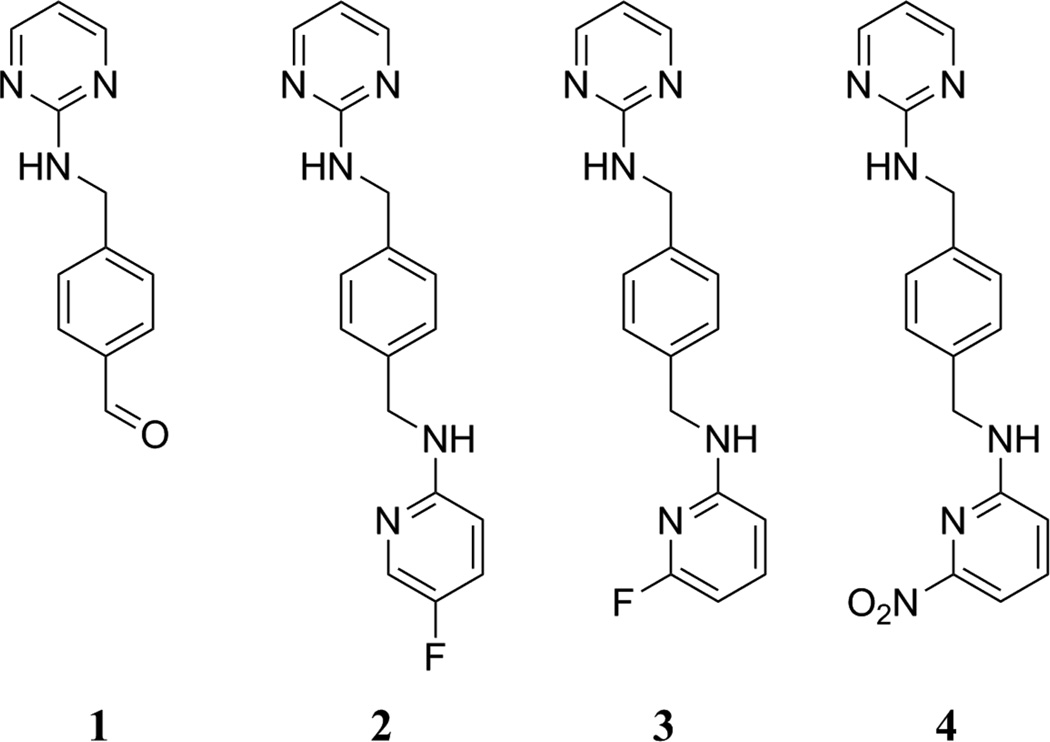

Dipyrimidine-based agents – where the two pyrimidines were linked through a paraxylyl-endiamine – and pyrimidine-pyridine amine-based agents – where the two heterocycles were linked through a para-xylyl-endiamine – have been suggested by Zhu et al. to specifically target CXCR4 [16] and in silico calculations of the partition coefficients indicated that these compounds have potential to cross the BBB. Zhu et al. reported that many of the pyrimidine-pyridine amine-based agents, including fluorine containing variants – 2 and 3 (Fig. 1), had low nM affinities for CXCR4 [16] based on a fluorescence inhibition binding affinity assay utilizing MDA-MB-231 cells, a biotinylated peptide (TN14003-biotin), and secondary staining with rhodamine. Though both 2 and 3 showed limited efficacy in matrigel invasion inhibition assays, compound 3 displayed significant paw inflammation suppression in vivo [16]. Our goal was to develop an 18F-labeled compound that can penetrate the BBB and therefore we investigated the potential of 18F-labeled 3 as a potential PET imaging agent of CXCR4-positive tumors. Work from the same group to develop an 18F-labeled CXCR4 targeting agent utilized a radiolabeled compound to determine the IC50 value for uptake in MDA-MB-231 cells, but no imaging data was reported [17].

Figure 1.

Compounds used in this study.

The current study describes the synthesis of a nonradioactive analog (3) and the corresponding nitro precursor (4), an HPLC method development for separation of the precursor from the final product, and radiofluorination to produce [18F]-3. Preliminary in vitro and in vivo evaluations of [18F]-3 with comparison to [67/68Ga]-pentixafor were performed.

Experimental

All chemicals were commercially available, unless otherwise stated. All nonradioactive synthesized materials were analyzed using a Bruker Ultrashield Plus 600 MHz NMR and Acquity-SQD mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA) or Shimadzu LC-MS (Kyoto, Japan) with Gemini-NX column (Phenomenex, C-18, 5 µm, 110 Å, 250 × 4.6 mm) 10–95% AcN in water with 0.05% formic acid over 15 min at 1 mL/min. The human glioblastoma cell line U87 (U87 WT) and mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line NIH/3T3 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FCS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1500 mg/L NaHCO3, 100 units/mL penicillin G and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. A CXCR4 over-expressing U87 cell line (U87 CXCR4) was provided by the NIH AIDS Reagent Program (cat. no. 4036) [18] and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s high glucose medium (DMEM-HG) with 10% FCS, 1 µg/mL puromycin, 300 µg/mL G418, 100 units/mL penicillin G and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. The human mammary gland/breast adenocarcinoma cell line MDA-MB-231 was purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured in DMEM-HG with 10% FCS, 100 units/mL penicillin G and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. All culture media was prepared by the MSKCC Media Preparation Core.

1 was prepared in two steps as reported [16] in 7.28 % overall yield and confirmed by NMR. 2 and 3 were previously reported by Zhu et al. [16], but were purified in the present study by semi-prep HPLC (Phenomenex, Jupiter C-18, 5 µm, 300 Å, 250 × 10 mm, 3 mL/min). 2 eluted from 15 to 17.5 min (10 to 67% AcN in water over 13 min) and 3 eluted from 26.4 to 29 min (10 to 67% AcN in water over 30 min). The fractions were lyophilized to dryness and confirmed by 1H-NMR and MS.

Synthesis of N-(4-(((6-nitropyridin-2-yl)amino)methyl)benzyl)pyrimidin-2-amine (4)

To a dry mixture of 1 (49.9 mg, 0.234 mmol) and 2-amino-6-nitropyridine, 5 mL of 1,2-dichloroethane were added. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature to dissolve the solids. After dissolution, acetic acid (14.76 µL, 0.2579 mmol), molecular sieves (191 mg, flame dried), and sodium triacetoxyborohydride (106.5 mg, 0.5025 mmol) were added sequentially. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 days. Ethyl acetate (5 mL) was added and the soluble material transferred to a new vial. To the supernatant, 1 M NaOH (3 mL) was added and the mixture extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, gravity filtered, and rotary evaporated. The solids were dissolved in 5 mL of 50:50 AcN:water and filtered through a 0.2 µm nylon filter (Pall Life Sciences, Port Washington, NY). The vial was washed with 2 mL of EtOAc, then 2 mL CH2Cl2, and then 1 mL MeOH, which were sequentially filtered through the nylon filter and collected. The combined filtrate was purified by HPLC in 1 mL injections using a semi-prep HPLC method (Phenomenex, Jupiter C-18, 5 µm, 300 Å, 250 × 10 mm, 3 mL/min, 10 to 67% AcN in water over 30 min) to elute the product from 26.5 to 27.7 min. The fraction was lyophilized to yield 13.4 mg of 4 as a yellow solid (0.0398 mmol, 17.0% yield) and HPLC analyzed using an analytical method (Kinetex F5, Phenomenex, 100 × 4.6 mm, 2.6 µm, 100 Å, 0.5 mL/min, 35% EtOH in 50 mM NH4OAc) to elute 4 at 30.0 min. 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.30 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H, CHCHN-pyrimidine), 7.64 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, NC(NO2)CHCHCH-nitropyridine), 7.49 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, NC(NO2)CHCHCH-nitropyridine), 7.34 (s, 4H, benzyl), 6.65 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, NC(NO2)CHCHCH-nitropyridine), 6.57 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, CHCHN-pyrimidine), 5.42 (s, 1H, CH2NH-nitropyridine), 5.34 (s, 1H, CH2NH-pyrimidine), 4.64 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, CH2NH-nitropyridine), 4.55 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 2H, CH2NH-pyrimidine). 13C-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 162.21 (quaternary C pyrimidine), 158.13 (CHCHN-pyrimidine), 157.50 (quaternary C nitropyridine), 156.04 (NC(NO2)CHCHCH-nitropyridine), 140.11 (NC(NO2)CHCHCH-nitropyridine), 138.67 (quaternary C benzyl), 136.71 (quaternary C benzyl), 127.82 (CH-benzyl), 112.32 (NC(NO2)CHCHCH-nitropyridine), 111.04 (CHCHN-pyrimidine), 106.27 (NC(NO2)CHCHCH-nitropyridine), 46.03 (CH2NH-pyrimidine), 45.00 (CH2NH-nitropyridine). LC-MS (C17H16N6O2, 12.73 min) [M+H]+ 337.05; [M−H]− 334.95.

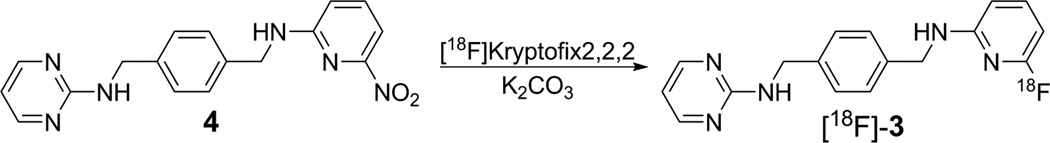

Radiosynthesis of [18F]-3 (N-(4-(((6-[18F]fluoropyridin-2-yl)amino)methyl)benzyl)pyrimidin-2-amine)

Prior to beginning the reaction, reaction vials were dried overnight in an oven to remove residual water. Fluorine-18 irradiated target water was obtained from the MSKCC cyclotron facility (GEMS PETtrace-800 cyclotron, GE Healthcare). The 18F− was trapped on a preconditioned QMA anion exchange cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA) and eluted with 2 mL of eluant (42.5 mg K2CO3 (5.9 mM) and 237.5 mg Kryptofix (21 mM) in 2.0 mL milli-Q water and 50 mL DNA-quality anhydrous AcN). The solvent was azeotropically distilled by heating the reaction vessel at 110 °C under a stream of Ar (g). An aliquot of approximately 200 µL of anhydrous DMF was added and evaporated at 155 °C under a stream of Ar (g). 4 (~2 mg, 5.9 µmol) was dissolved in 200 µL of anhydrous DMF and added to the reaction vial under an Ar (g) atmosphere and heated at 155 °C for 15 min. The reaction mixture changed color from yellow to dark brown over the course of the reaction. After the reaction mixture was cooled in a dry ice/water bath, 1 mL of water was added. The reaction mixture was passed through a preconditioned Sep-Pak Light C18 cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA) and eluted with 1 mL of EtOH in 0.1 mL portions. The fractions with highest radioactivity were combined, diluted with water to obtain about 35% EtOH in less than 2 mL of solution, and purified by HPLC using an isocratic solvent system (Kinetex F5, Phenomenex, 100 × 4.6 mm, 2.6 µm, 100 Å, 0.5 mL/min, 35% EtOH in 50 mM NH4OAc). The [18F]-3 eluted at approximately 27.1 min and the unreacted 4 eluted after 30 min. The radioactive peak was collected, trapped on a preconditioned Sep-Pak Light C18 cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA), and eluted with 1 mL of EtOH in 0.1 mL portions. The eluant was diluted with sterile PBS to obtain mouse injections of approximately 120 µCi/mouse with < 10% EtOH.

The partition coefficient of [18F]-3 (reconstituted in < 10% EtOH in PBS) was determined by octanol/PBS partitioning. The diluted [18F]-3 (2 µL) was added to 0.5 mL of octanol and 0.5 mL of PBS (pH 7.4) in triplicate. The mixtures were vortexed and then centrifuged (approximately 1 min and 6000 rpm, Standard Mini Centrifuge, Fisher Scientific). The layers were sampled (80 µL from each layer) four times and counted using an automatic gamma counter (2480 Wizard2 3”, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). The entire procedure was repeated a second time from a separate batch of [18F]-3.

Plasma protein binding study was performed in whole mouse blood that was collected from a nude male mouse by terminal blood draw in a tube containing heparin. To two aliquots of blood, [18F]-3 was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Additionally, an aliquot of saline was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. One of the blood and the saline mixtures was filtered using a 2,000 molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filter (Vivaspin 2, Sartorius, Gottingen, Germany). The filtrate (20–150 µL) and the remaining solution at the top of the filter (20 µL each) were each sampled and counted using an automatic gamma counter (2480 Wizard2 3”, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). The activity was corrected for volume sampled and the percent unbound in the plasma was normalized to the saline study.

Plasma stability of [18F]-3 was determined in human plasma (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The human plasma was divided into 450 µL aliquots, frozen, and allowed to thaw to room temperature prior to the study. To the aliquot, 50 µL (~ 88 µCi, 3.3 MBq) of [18F]-3 in PBS with < 10% EtOH was added in triplicate for two time points (1 and 2 h). The mixture was placed on a thermomixer (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) at 37 °C and 500 rpm. The mixture was removed from the shaker, 400 µL of ice cold AcN added, and vortexed. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed and filtered through a 0.2 µm syringe filter (0.22 µm GV Durapore centrifugal filter unit, Millipore, Billerica, MA) before being injected onto the HPLC (Jupiter C-18 column, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm, 300 Å, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, with an HPLC method of 25% AcN (0–2 min), 25–45% AcN (2–4 min), 45% AcN (4–16 min), 45–80% AcN (16–17 min) in water with 0.1 % TFA).

Cellular-uptake-assay media stability of 3 was performed with diluting 3 in 67% DMSO and 33 % PBS (2.97 mg/mL). The nonradioactive mixture was filtered using a syringe filter (13 mm sterile disposable filter, 0.2 µm, Whatman, GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). The initial solution was confirmed by HPLC to be pure prior to an aliquot (75 µL) of the solution being added to two separate 1 mL aliquots of U87 WT media without FCS (DMEM with 2mM L-glutamine, 1500mg/L NaHCO3, 100 units/mL penicillin G and 100 µg/mL streptomycin). The two aliquots were incubated at 37 °C for 30 or 60 min prior to filtration (0.2 µm syringe filter, 13 mm, Whatman, GE Healthcare) and HPLC injection of the entire aliquot (Kinetex F5, Phenomenex, 100 × 4.6 mm, 2.6 µm, 100 Å, 0.5 mL/min, 35% EtOH in 50 mM NH4OAc).

Cellular uptake assay

Pentixafor was labeled with 67/68Ga following the protocol from Demmer et al. [19]. U87 WT cells and U87 CXCR4 cells were seeded on a 6-well cell culture plate (Corning Life Sciences) at 5×105 cells/well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight in 1 mL of media for the cells to adhere to the plates. 67Ga-pentixafor (0.79 µCi, 29 kBq, 1 nM) and a blocking agent (AMD3100, 2, or 3 at concentrations from 3 mM to 100 nM) were added to the media in each well and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. After incubation, the media from each well was collected separately and each well was washed twice with 500 µL of PBS. All washes were collected with the incubation media in order to account for any unbound 67Ga-pentixafor. The cells were detached from the plates with the use of trypsin and collected with two 500 µL washes of PBS. The activity of each of the collected fractions (cells and media) from each well was measured with an automatic gamma counter (1480 Wizard 3”, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA).

A similar experiment incubating both U87 WT and U87 CXCR4 cells in media with and without FCS was performed in 6-well plates. The uptake of 67Ga-pentixafor and [18F]-3 was monitored over 30, 60, and 120 min following a similar incubation and wash protocol as above. Again, the activity of the collected fractions (cells and media) from each well was measured with the automatic gamma counter (1480 Wizard 3”, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA).

Additionally, an experiment incubating U87 WT, U87 CXCR4, MDA-MB-231, and 3T3 cells without FCS was performed in 12-well plates. The uptake of [18F]-3 was determined at 15 and 60 min with a similar washing protocol (supernatant removal, two 1 mL PBS washes, 1 mL of trypsin incubation and removal, and two 1 mL PBS washes). Each wash fraction in this study were collected separately and counted.

In vivo studies

All animal studies were performed under an approved MSKCC IACUC protocol. Nude male mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). U87 WT (3×106 cells on the left shoulder) and U87 CXCR4 (3×106 cells on the right shoulder) cells were xenografted subcutaneously on each shoulder. The biodistribution and PET/CT imaging studies were performed 2 months after xenotransplantation. The PET/CT images were obtained on a Inveon PET/CT (Siemens, Washington, DC.) utilizing static, whole body PET scans (minimum of 20 million coincident events with scan durations of 4 – 10 min) while the mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation in medical air (1.5% isoflurane with a flow rate of 2 L/min). The energy and coincidence timing windows were 350−750 keV and 6 ns, respectively. The image data were normalized to correct for nonuniformity of response of the PET, dead-time count losses, positron branching ratio, and physical decay to the time of injection, but no attenuation, scatter, or partial-volume averaging correction was applied. The images were analyzed using the Inveon Research software (Siemens) to obtain files that could be further analyzed by ASIPro VM (CTI Concorde Microsystems, LLC). The resultant images were saved as jpeg files and cropped and aligned in PowerPoint.

Additionally, a single nude female nontumor-bearing mouse (6–8 weeks, CRL) was injected with approximately 600 µCi of [18F]-3 in ~200 µL of PBS (with EtOH). The mouse was imaged at 1.25 and 1.5 h, urine collected at 2 h, and imaged again at 2.5 h p.i. following the same protocol as described above. The urine (~200 µL) was diluted with EtOH (200 µL) and PBS (400 µL) prior to filtration (0.2 µm syringe filter, 13 mm, Whatman, GE Healthcare) and HPLC injection.

In all studies that included multiple replicates, the individual values were averaged and standard deviation determined using the sample standard deviation method (n-1).

Results and Discussion

Two compounds were previously reported by Zhu et al. for targeting CXCR4 receptors. Because the fluorescence-based cellular binding affinity data of Zhu et al. indicated that optimal targeting could be achieved by a number of different compounds, 2 and 3 were chosen for this study. This selection was based on the ease of radiosynthesis from nitro group containing precursors (using the SNAr reaction to radiolabel the molecule in a single step), and because Zhu et al. reported low nanomolar affinity for both compounds. Initially, only one nitro precursor (4) was synthesized. 4 – a previously unreported compound – was fully characterized by NMR and MS to ensure that the desired product had been formed.

After preparing 3 and 4, HPLC separation parameters were optimized to separate the two species (Table S1) based on the findings from Wenzel et al. [20]. The HPLC method using a traditional C-18 column with all solvent systems (buffered and pH adjusted) showed limited separation of the two species and eluted 4 prior to 3. In radioactive syntheses, the radioactive peak should elute before the nonradioactive material so that any tailing of the nonradioactive peak does not overlap the radioactive peak. Using a pentafluorophenyl (PFP) column, the order of elution was reversed and 3 was separable from 4. Alternatively, F5 columns (PFP with core-shell technology and smaller diameter particles from Phenomenex) showed similar separation properties of the traditional PFP column, but required half of the solvent (10–30 mL) per HPLC run. Use of a smaller diameter F5 column increased the pump pressure demands of the larger diameter F5 column, which was reduced by a lower flow rate for the EtOH/50 mM NH4OAc solvent system. The HPLC method that was finally chosen for radiolabeling purification separated 3 from 4 (with baseline resolution), eluted 3 before 4, reduced the solvent usage by half (compared to the traditional PFP column), and reduced the overall pressure of the system (relative to the smaller diameter column).

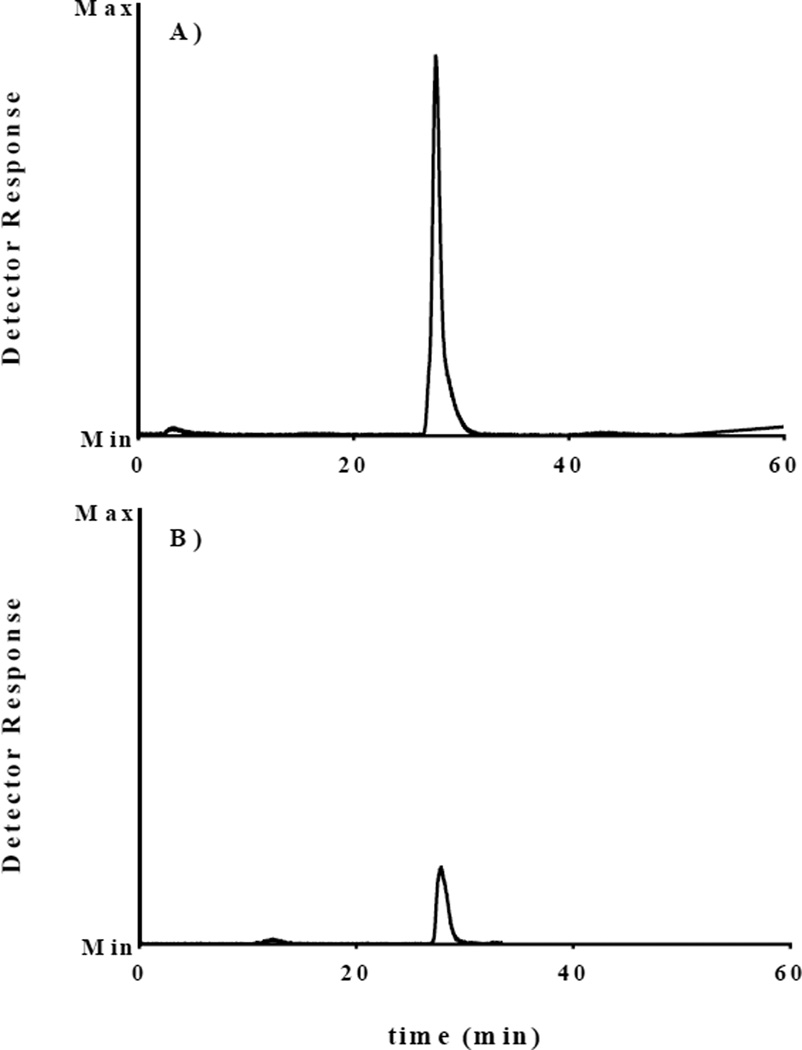

After ensuring the radiolabeled material could be separated from the precursor, [18F]-3 was synthesized from 4 using the 18F-kryptofix 2.2.2 complex in anhydrous DMF under an Ar (g) atmosphere. [18F]-3 (tR = 27.1 min) was separated from the precursor (tR ≈ 30 min) using the F5 column with an isocratic solvent system (35% EtOH in 50 mM NH4OAc) to obtain 4–10% decay-corrected (to start of synthesis) isolated yield. Figure S1 depicts that the radioactive peak ([18F]-3) coelutes with that of 3. This signal is more prominent on the UV-visible HPLC trace when a greater amount of 3 is injected (Figure S4). The nonradioactive UV-visible HPLC peak eluting after [18F]-3 was collected, lyophilized, and analyzed by 1H-NMR to prove that the UV-visible peak was, in fact, unreacted 4.

Once [18F]-3 was purified by HPLC, it needed to be dissolved in a biologically compatible solvent system for in vitro and in vivo studies; thus, the collected HPLC peak was diluted, passed through a C-18 cartridge to trap [18F]-3 and eluted in 100% EtOH. The eluant was then diluted with PBS for further studies. Figure 3 shows the radioactive HPLC trace for the purified material. Direct assessment of the specific activity could not be determined because the UV-visible peak from the isolated material was not quantifiable in most of the radiochemical synthesis runs. The approximate specific activity was estimated to be greater than 35 µCi/nmol (6.94 MBq/nmol). (This approximation is based on the amount of starting material used.) Although the radiochemical yields and specific activity might be increased under different reaction conditions, they were sufficient for the studies described herein.

Figure 3.

Radioactive detector trace of A) the reaction mixture and B) the purified material used in cell studies using the F5 column (2.6 µm, 100 Å, 100 × 4.6 mm) with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min of 35% EtOH in 50 mM NH4OAc aqueous solution (tR = 27.1 min). The graph of B was set relative to that of A; thus, the overall amount of radioactivity injected in B was much lower than in A.

A major consideration in our study was the design of a PET tracer that would cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). In order to cross the BBB, a neutral compound with LogD of 0–3 is generally favorable [21]. The partition coefficient (LogD7.4) for [18F]-3 is 1.4 ± 0.5 which is favorable. Mouse plasma protein binding studies (with whole mouse blood with heparin incubated with [18F]-3), using ultra-filtration to separate the tracer bound to the plasma proteins away from the supernatant, indicated that > 97% of [18F]-3 was bound to the plasma proteins at 1 h. Although the plasma protein binding may appear high for a compound with a LogD7.4 of 1.4, this is not unprecedented [22, 23], especially since 3 is neutral at pH 7.4.

Next, we verified the stability of [18F]-3 in human plasma over 2 h. After separating the plasma proteins from the mixture, the radiochemical purity was determined by HPLC (Figure S2) to be 69.3 ± 0.7 % and 71 ± 2 % at 1 and 2 h, respectively. The lack of change between the 1 and 2 h time points indicates that [18F]-3 is sufficiently stable in human plasma, probably related to high plasma protein binding.

Once the separation and stability of the compound were tested, initial binding assays were performed in CXCR4-expressing and CXCR4-negative cell lines to assess the cell surface receptor targeting of both 2 and 3. 67Ga-pentixafor with 2, 3, or AMD3100 was incubated with both U87 WT (CXCR4 negative) and CXCR4 over-expressing U87 cells (U87 CXCR4) in a competitive cell binding assay. In these experiments, 67Ga-pentixafor uptake was inhibited by AMD3100, but not by 2 or 3 (Table S2). Since > 97% of [18F]-3 is bound to the plasma proteins, which may affect cell binding studies when the cell media contains FCS the question of whether [18F]-3 binding to FCS in the incubation medium could affect cell binding studies was raised. A second binding assay was performed where the cellular uptake of [18F]-3 and 67Ga-pentixafor were carried out in media with and without FCS. In each of these parallel experiments using the same batch of cells, the uptake of [18F]-3 for all cell types and cell medias was extremely low (Table S3), while the uptake of 67Ga-pentixafor was > 20 times higher in U87 CXCR4 cells compared to U87 WT cells (Table S3). Each of these studies indicated that the either [18F]-3 does not or is rapidly metabolized into another species that does (do) not target CXCR4 cell surface receptors.

In order to match the previous findings of Zhu et al. [16], a final cell binding study with the same cell line used by Zhu et al. (MDA-MB-231, which is CXCR4+) was performed. This study also included U87 CXCR4 and U87 WT cells, as well as 3T3 cells (another negative control cell line). Each of the solutions (supernatant, washes, and trypsinized cell layer) were separately counted to determine the amount of radioactivity in each of these components. In each wash, the activity of the solution decreased steadily indicating that none of the cell types showed any significant uptake/binding of [18F]-3 over the 15 and 60 min monitored (Table S4). Furthermore, calculating the % radioactivity in cells/million cells demonstrated that even slight targeting was unreasonable (Table S4).

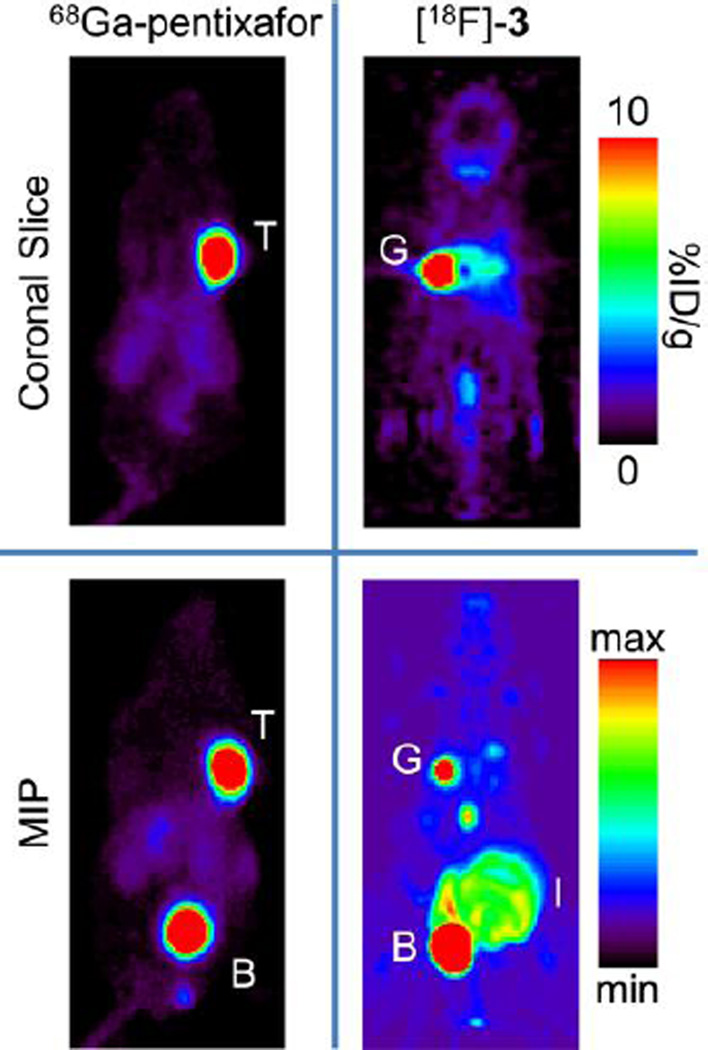

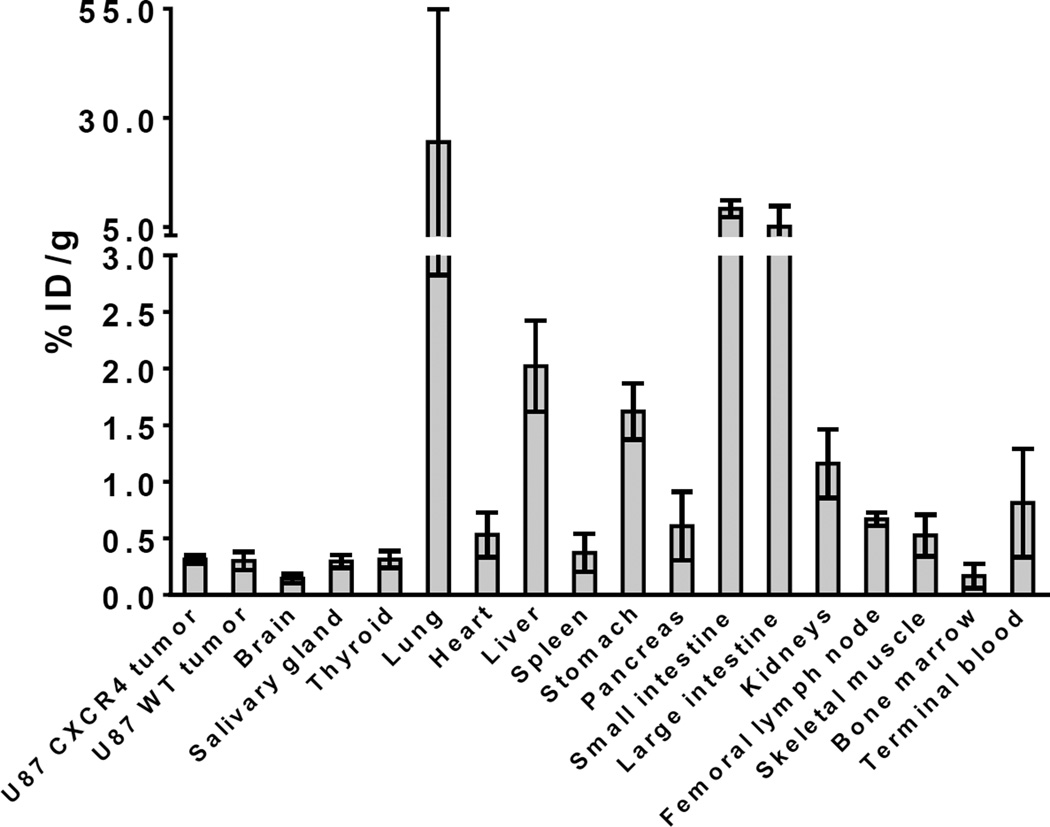

To ensure that our cell studies matched in vivo targeting of these compounds, three nude mice bearing a U87 CXCR4 tumor on the left shoulder and a U87 WT tumor on the right shoulder were injected with [18F]-3 one day after being injected with 68Ga-pentixafor. In all three mice, the CXCR4 positive tumor was clearly visualized using 68Ga-pentixafor, but not with [18F]-3. Figure 4 shows the coronal slice (through the tumors) and maximum intensity projection (MIP) images for the in vivo biodistribution of 68Ga-pentixafor and [18F]-3 at 1 h. Ex vivo biodistribution of the imaging mice showed no significant difference between the uptake of the U87 CXCR4 tumor (0.31 ± 0.04 %ID/g) and U87 WT tumor (0.30 ± 0.08 %ID/g). The complete ex vivo biodistribution results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Coronal slice and maximum intensity projection (MIP) of the same nude male mouse injected with 68Ga-pentixafor and [18F]-3 on subsequent days with imaging at 1 h post injection. The U87 WT tumor is on the left shoulder, the U87 CXCR4 tumor is on the right shoulder. The major tracer uptake on the images are labeled for clarity (T = tumor, B = bladder, G = gall bladder, I = intestines).

Figure 5.

Ex vivo biodistribution of [18F]-3 in nude male mice at 1.5 – 2 h post injection, after imaging study (n = 3 mice).

The major excretion of [18F]-3 is through the urine and the major uptake shown in the coronal slice for the mouse injected with [18F]-3 (Figure 4) is most likely gall bladder and liver, as well as the bladder and intestine in the MIP image. High uptake in the excretion pathways (as opposed to bone) indicates that [18F]-3 is not metabolized via a defluorination pathway. Rapid excretion through the urine could be a result of another metabolite that is 18F labeled or excretion of intact [18F]-3. In either case, the high binding of [18F]-3 to plasma is reversible, since there is rapid urinary excretion of [18F]-3 or a radiolabeled metabolite. To address this question, an additional nontumor-bearing mouse was injected with [18F]-3 and the urine was removed at 2 h p.i. HPLC analysis (Figure S3) of the urine showed < 3% of the activity corresponded to the retention time of [18F]-3 (27.1 min). The remaining activity eluted before this peak (prior to 12 min), which indicates that the majority of the radioactive material (> 97%) was more hydrophilic metabolites. The rapid excretion of a metabolite or decomposition product is probably the main reason there is little brain uptake. Additionally, we did not investigate the uptake of these tumors behind an intact BBB due to the low uptake of radioactivity in the shoulder xenografts.

Due to the low cellular uptake (in vitro) and rapid metabolism (in vivo), the nonradioactive standard, 3, was incubated with cell culture media without FCS to determine the stability of 3. The results showed that < 4% of the original parent compound remained after 30 min and that < 3% of the original parent compound remained after 60 min (Figure S4). Thus, despite the stability of [18F]-3 in human serum, [18F]-3 and 3 show limited stability in vivo and in cell culture media. This may be due to 1) the presence of plasma proteins that strongly bind 3, thereby protecting it from rapid decomposition or metabolism, or 2) the absence of the molecules that metabolize 3 in the plasma. Zhu et al. reported that 3 blocked the binding of TN14003 with MDA-MB-231 cells, moderately inhibited the invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells in matrigel and suppressed the paw inflammation in an in vivo carrageenan-induced mouse paw edema model [16]. These previous results would appear contradictory to the instability of 3 in cell culture media, but the in vivo results reported by Zhu et al. could have been caused by a metabolite of 3 rather than 3 itself.

Conclusions

Herein we described the synthesis (from a novel nitro-precursor, 4), separation and initial evaluation of [18F]-3. Despite having produced a pure, low specific activity radiopharmaceutical, the CXCR4 targeting of 3 (and 2) was demonstrated to be suboptimal for in vitro cell binding and in vivo tumor targeting. The lack of in vitro cell surface receptor binding and presence of rapid in vivo excretion indicates the rapid metabolism of 3. Future improvements in both the stability and CXCR4-binding of heterocyclic pyrimidine-pyridine amine-based (and possibly dipyrimidine-based) compounds will be needed in order to obtain a radiolabeled small molecule capable of targeting/imaging CXCR4 positive lesions and penetrating an intact BBB.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Radiochemical preparation of [18F]-3 from 4.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank grant support (NIH F32 CA186721, DWD), the MSKCC Center Grant (P30 CA08748) for support of the MSK Radiochemistry & Molecular Imaging Probe Core, and the MSK Small Animal Imaging Core Facility. An NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant No 1 S10 OD016207-01, which provided funding support for the purchase of the Inveon PET-CT, is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zou YR, Kottman AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in heaematopolesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998;393:595–599. doi: 10.1038/31269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lesniak WG, Sikorska E, Shallal H, Behnam Azad B, Lisok A, Pullambhatla M, et al. Structural Characterization and in Vivo Evaluation of β-Hairpin Peptidomimetics as Specific CXCR4 Imaging Agents. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2015;12:941–953. doi: 10.1021/mp500799q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramji DP, Davies TS. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: Key players in all stages of disease and promising therapeutic targets. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2015;26:673–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogłodek EA, Szota AM, Mos̈ DM, Araszkiewicz A, Szromek AR. Serum concentrations of chemokines (CCL-5 and CXCL-12), chemokine receptors (CCR-5 and CXCR-4), and IL-6 in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and avoidant personality disorder. Pharmacological Reports. 2015;67:1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozawa PMM, Ariza CB, Ishibashi CM, Fujita TC, Banin-Hirata BK, Oda JMM, et al. Role of CXCL12 and CXCR4 in normal cerebellar development and medulloblastoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2016;138:10–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doring Y, Pawig L, Weber C, Noels H. The CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine ligand/receptor axis in cardiovascular disease. Frontiers in physiology. 2014;5:212. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teicher BA, Fricker SP. CXCL12 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 pathway in cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:2927–2931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagliardi F, Narayanan A, Reni M, Franzin A, Mazza E, Boari N, et al. The role of CXCR4 in highly malignant human gliomas biology: current knowledge and future directions. Glia. 2014;62:1015–1023. doi: 10.1002/glia.22669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson O, Weiss ID, Szajek L, Farber JM, Kiesewetter DO. 64Cu-AMD3100-A novel imaging agent for targeting chemokine receptor CXCR4. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:1486–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Silva RA, Peyre K, Pullambhatla M, Fox JJ, Pomper MG, Nimmagadda S. Imaging CXCR4 expression in human cancer xenografts: Evaluation of monocyclam64Cu-AMD3465. J. Nuc. Med. 2011;52:986–993. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.085613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodard LE, De Silva RA, Behnam Azad B, Lisok A, Pullambhatla M, Lesniak WG, et al. Bridged cyclams as imaging agents for chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) Nuc. Med. Biol. 2014;41:552–561. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.04.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aghanejad A, Jalilian AR, Fazaeli Y, Beiki D, Fateh B, Khalaj A. Radiosynthesis and biodistribution studies of [62Zn/ 62Cu]-plerixafor complex as a novel in vivo PET generator for chemokine receptor imaging. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2014;299:1635–1644. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gourni E, Demmer O, Schottelius M, D'Alessandria C, Schulz S, Dijkgraaf I, et al. PET of CXCR4 Expression by a 68Ga-Labeled Highly Specific Targeted Contrast Agent. J. Nuc. Med. 2011;52:1803–1810. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.098798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herrmann K, Lapa C, Wester HJ, Schottelius M, Schiepers C, Eberlein U, et al. Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry for the chemokine receptor CXCR4-targeting probe 68Ga-pentixafor. J. Nuc. Med. 2015;56:410–416. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.151647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derlin T, Jonigk D, Bauersachs J, Bengel FM. Molecular Imaging of Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Using 68Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT: Comparison With 18F-FDG. Clinical Nuclear Medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu A, Zhan W, Liang Z, Yoon Y, Yang H, Grossniklaus HE, et al. Dipyrimidine amines: A novel class of chemokine receptor type 4 antagonists with high specificity. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:8556–8568. doi: 10.1021/jm100786g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang Z, Zhan W, Zhu A, Yoon Y, Lin S, Sasaki M, et al. Development of a Unique Small Molecule Modulator of CXCR4. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Björndal A, Deng H, Jansson M, Fiore JR, Colognesi C, Karlsson A, et al. Coreceptor usage of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates varies according to biological phenotype. Journal of Virology. 1997;71:7478–7487. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7478-7487.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demmer O, Gourni E, Schumacher U, Kessler H, Wester H-J. PET Imaging of CXCR4 Receptors in Cancer by a New Optimized Ligand. Chem Med Chem. 2011;6:1789–1791. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201100320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wenzel B, Günther R, Brust P, Steinbach J. A fluoro versus a nitro derivative-a high-performance liquid chromatography study of two basic analytes with different reversed phases and silica phases as basis for the separation of a positron emission tomography radiotracer. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;1311:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pajouhesh H, Lenz GR. Medicinal Chemical Properties of Successful Central Nervous System Drugs. NeuroRx. 2005;2:541–553. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lázníček M, Lázníčková A. The effect of lipophilicity on the protein binding and blood cell uptake of some acidic drugs. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1995;13:823–828. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01504-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urien S, Tillement J-P, Barré J. The Significance of Plasma-Protein Binding in Drug Research. Pharmacokinetic Optimization in Drug Research: Verlag Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2007:189–197. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.