Abstract

The Haber-Bosch process is a major contributor to fixed nitrogen that supports the world's nutritional needs and is one of the largest-scale industrial processes known. It has also served as a testing ground for chemists’ understanding of surface chemistry. Thus, it is significant that the most thoroughly developed catalysts for N2 reduction use potassium as an electronic promoter. In this review, we discuss the literature on alkali metal cations as promoters for N2 reduction, in the context of the growing knowledge about cooperative interactions between N2, transition metals, and alkali metals in coordination compounds. Because the structures and properties are easier to characterize in these compounds, they give useful information on alkali metal interactions with N2. Here, we review a variety of interactions, with emphasis on recent work on iron complexes by the authors. Finally, we draw conclusions about the nature of these interactions and areas for future research.

Keywords: Haber-Bosch, nitrogen, ammonia, alkali metals, iron

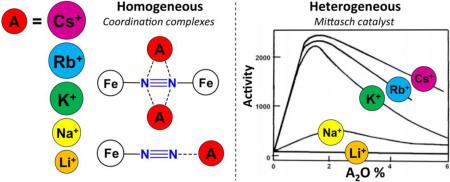

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perspectives, Goals

Many heterogeneous catalysts are promoted by addition of alkali cations, and the study of promoters is important for development of more efficient catalysts [1-4]. The Haber-Bosch (H-B) process for N2 conversion to NH3 is one example of a very well-studied heterogeneous process that benefits from alkali cation promoters [5-7]. There has been a resurgence of interest in N2 reduction because of its potential as a carbon-free fuel and because of the energy savings that would accrue from even small improvements in this very large-scale process [7-9]. Despite the fact that N2 reduction is one of the best-studied surface processes, the atomic-level detail of the interactions between the alkali-metal cation and the substrate are still not clear.

Atomic-level detail is much easier to acquire for soluble molecular compounds, which are amenable to X-ray crystallography to < 1 Å resolution as well as a variety of solution methods that elucidate dynamics that would be difficult or impossible to resolve on a surface. Moreover, the ability to isolate pure, structurally-characterized samples of homogeneous species enables mechanistic studies that are simpler to interpret. Though many interactions are not identical between solution and surface species, advances in the understanding of solution compounds can provide models and analogies that are useful for further development of the potential surface chemistry on heterogeneous catalysts.

With this idea in mind, this article presents a review focusing on the roles of alkali metal cations during the binding and cleavage of N2 in solution complexes. As will be seen below, interactions between these cations and N2 can greatly facilitate cleavage of the N-N bond, and current research is making significant strides in elucidating the interactions that are important in solution alkali-metal promoters. It is our hope that these emerging results will lead to new ideas for surface promoters as well.

1.2. Mechanism of the Fe-catalyzed Haber-Bosch process

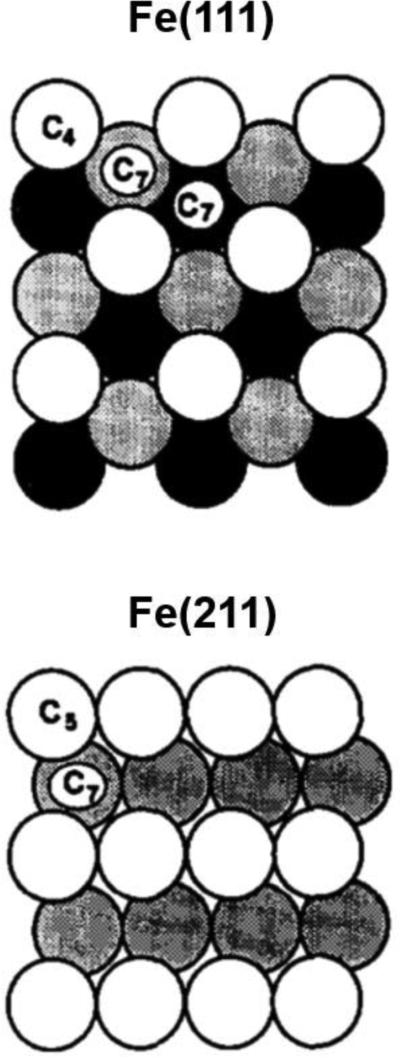

During the H-B process, a feedstock of H2 and N2 gas in a 3:1 ratio is reacted over a promoted Fe catalyst at ~700 K and ~100 bar. The technical catalyst, developed by Mittasch close to a century ago, is a fused-Fe catalyst promoted with alumina and potash (a mixture of water-soluble potassium salts such as KOH and K2CO3) [10, 11]. The average oxidation state of Fe in the Mittasch catalyst is between 0 and +1 [12]. The direct observation of the technical H-B catalyst under catalytic conditions is difficult, so many studies probing the mechanism and kinetics of the H-B process are done using single-crystal Fe surfaces [13]. Samples where the Fe(111) plane is exposed are the most active single-crystal Fe catalysts for the H-B process [14]. Somorjai attributed this to the fact that the Fe(111) plane has the highest concentration of exposed C7 sites (where an Fe atom has seven nearest neighboring Fe atoms), at which the high-coordination number facilitates charge-transfer reactions (such as N2 reduction) via local electronic fluctuations [15, 16]. However, the Fe(111) surface reconstructs and incorporates subsurface nitrides under reaction conditions [17, 18]. In addition to the Fe(111) plane, the Fe(211) and Fe(310) planes are quite active towards small molecule activation [19-21]. Figure 1 illustrates the Fe(111) and Fe(211) planes, each of which exposes C7 sites [15].

Figure 1.

Examples of Fe planes that expose highly active C7 sites for ammonia synthesis. Reprinted with permission from [15]. Copyright Elsevier, 1987.

On surfaces, extensive kinetic studies have shown that the mechanism of N2 reduction to NH3 involves dissociative H2 and N2 adsorption to the Fe surface, followed by hydrogenation of adsorbed N-atoms, and ultimately desorption of NH3 [5, 6]. On single-crystal Fe catalysts, the dissociation of adsorbed N2 to form two nitrides is the rate-limiting step of catalysis [22-26]. An analogous mechanism occurs using the Mittasch catalyst, with the dissociative adsorption of N2 generally considered to be the rate-limiting step [27, 28].

1.3. Promoters in the Fe-catalyzed Haber-Bosch process

During the development of the technical ammonia synthesis catalyst in the early 20th century, Mittasch discovered that the addition of foreign substances to the magnetite (Fe3O4) catalyst had a more pronounced effect on activity than the nature of the magnetite itself [10]. This prompted Mittasch and coworkers to systematically test the effect of thousands of additives on Fe catalysts for ammonia synthesis. Building from these studies, industrial Mittasch catalysts for the H-B process are synthesized through the fusion of Fe3O4 with various amounts of Al2O3, CaO, MgO, SiO2, and K2O. The first four are considered structural promoters that increase catalyst surface area, stabilize catalytically active Fe sites on the surface, and prevent sintering of the magnetite [29-32]. The potassium is generally considered to be an “electronic promoter;” its large ionic radius prevents incorporation into the magnetite during synthesis, and therefore it is localized at the surface [32]. Catalytic activity reaches a maximum at a certain amount of added potassium, both on polycrystalline Fe foil [33] and in the technical H-B catalyst [31]. The dropoff at higher surface coverage is explicable since the K+ resides on the surface and large amounts could block Fe active sites.

The seminal research by Mittasch, as well as many other subsequent studies, notes that other alkali metals also promote the technical catalyst [10, 28, 34-36]. Ruthenium-based H-B catalysts are also promoted with alkali metals [32]. In general, Ru catalysts exhibit higher activity with larger alkali metals, but recently Li was found to be a competent promoter [6, 37-39]. Analogous studies on alkali metal promoters for Fe catalysts do not always agree on the relative changes in activity when changing the alkali metal [28, 32, 34-36]. Understanding the precise role that these alkali metals play in improving the activity of structurally-promoted catalysts is vital for developing new ammonia synthesis catalysts with higher activity and robustness.

1.3.1. Determining the role of potassium in the Mittasch catalyst

The specific role of potassium in promoting the technical H-B catalyst is a topic of great interest, considering the enhancement of catalytic activity upon addition of potash to the iron oxide precursor [32, 34]. Hypothetical explanations include potassium involvement in N2 chemisorption to the Fe surface, hydrogenation of adsorbed N-atoms, and desorption of NH3 [40] [33] [30] [31] [41] [28] [42] [11]. Auger electron spectroscopy data indicate that the concentration of N2 adsorbed to an Fe(111) single-crystal surface increases in the presence of co-adsorbed potassium, suggesting that potassium increases the N2 adsorption energy to the Fe(111) surface [43]. Further investigating this effect, Whitman et al. reported that co-adsorption of potassium to Fe(111) specifically stabilizes N2 adsorption parallel to the surface, which is the precursor for N2 dissociation. They hypothesized that the potassium lowers the energy barrier for conversion of terminally bound N2 to the parallel-bound N2 dissociation precursor. Interestingly, no shift in the N-N stretching frequency (νNN) occurs for perpendicular or parallel adsorbed N2 in the presence of potassium, suggesting the absence of direct potassium-N2 interactions that weaken the N-N bond [41]. This contrasts with the shift of vibrational frequency of adsorbed CO between bare and cation-promoted surfaces in some cases [44, 45].

Potassium may also have electronic effects on the Fe surface that play a role. In studies done on the technical H-B catalyst, Altenburg et al. found that the amount of potassium added to the Fe/Al2O3 catalyst affects the reaction order of H2 in the reduction of NH3 [40]. Nielsen et al., expanding on Temkin's original kinetic model for the H-B process, established that the overall rate of NH3 formation depends on the order of H2 in the rate law [46, 47]. The order of H2 is in turn dependent on the ratio of N*, NH*, and NH2* (where the asterisk indicates surface-adsorbed fragments) formed after rate-determining N2 chemisorption to the Fe catalyst; N*, NH*, and NH2* react with 1.5, 1, and 0.5 equiv of H2 to form NH3*, respectively. This relationship implies that potassium promotes formation of N* species over partially hydrogenated species, leading to an increase in order of H2 and faster NH3 generation under catalytic conditions.

Altenburg et al. proposed a model in which stabilization of NH* and NH2* by hydrogen bonding with acidic OH groups inhibits the rate [40]. In this model, the presence of K+ on the surface decreases the coverage of surface Al3+-OH groups that would form stronger hydrogen bonds, and thus K+ gives a greater dependence of the rate on [H2] and faster rates at high pressure. This model predicts that the rate should be faster for cations with a smaller charge-to-radius ratio. Direct evidence supporting this theory is limited to kinetic data; however, observations by Au et al. that hydroxyl groups present on Zn(0001) hydrogenate chemisorbed N* to form NH* and NH2* support the tenets of this theory [48].

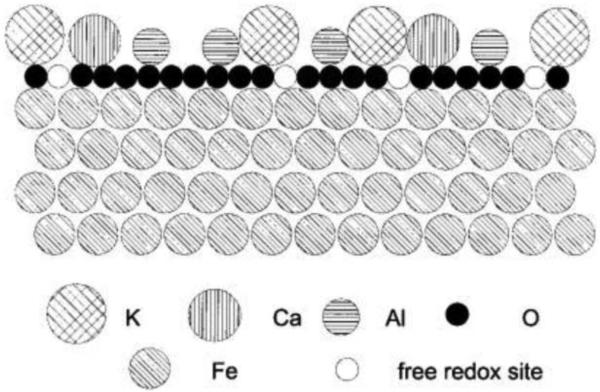

In the technical catalyst, K+ is certainly not reduced to a zerovalent state, and since it is introduced as potassium carbonate, is likely O-bound because alkali metal to transition metal interactions are weak [42, 49]. Chemical analysis and thermodynamic considerations argue that it is similar to KOH on the surface [50]. Arabczyk et al. proposed a double-layer model of the Mittasch catalyst surface under catalytic conditions (Figure 2) [51]. In this model, oxygen atoms on the surface of a bulk Fe lattice interact with cation promoters in a bridged Fe-O-M motif (where M is the cation). A double layer of oxygen and potassium covering the technical catalyst during H-B is consistent with spectroscopic evidence reported by Muhler et al. and Weinberg et al [52, 53]. Other models for the structure of the active technical catalyst also exist [18, 54]. Huo et al. recently reported that addition of a potassium promoter during the preparation of the technical ammonia synthesis catalyst results in a larger proportion of highly active Fe(211) and Fe(310) sites, further suggesting that alkali cations can be structural promoters [21].

Figure 2.

Double-layer model of promoted Fe catalyst surface. Reprinted with permission from [51]. Copyright American Chemical Society, 1999.

The presence of K+ affects the local electrostatic potential of the Fe surface [55]. Because of the greater radial extent of its orbitals, the calculated influence on electrostatic potential from K+ is much more pronounced than the influence from the O, which would result in higher electron density on Fe atoms surrounding the O-K unit [42, 56]. The localization of electron density in Fe atoms surrounding the potassium atom is expected to destabilize NH3 adsorption, allowing the more facile release of NH3. It has been shown experimentally that NH3 adsorption to a single-crystal Fe(111) surface is lower in the presence of potassium promoters [49, 57]. Therefore, potassium-promoted enhancement of catalytic activity in this system (and by analogy, the H-B process) can occur because the product NH3 is released more easily.

1.3.2. Promoting iron catalysts with other alkali cations

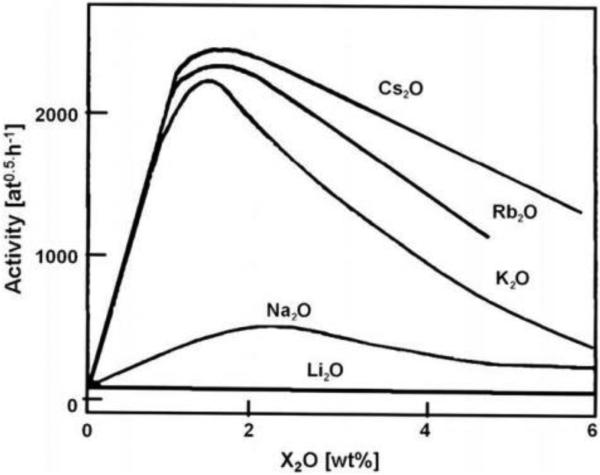

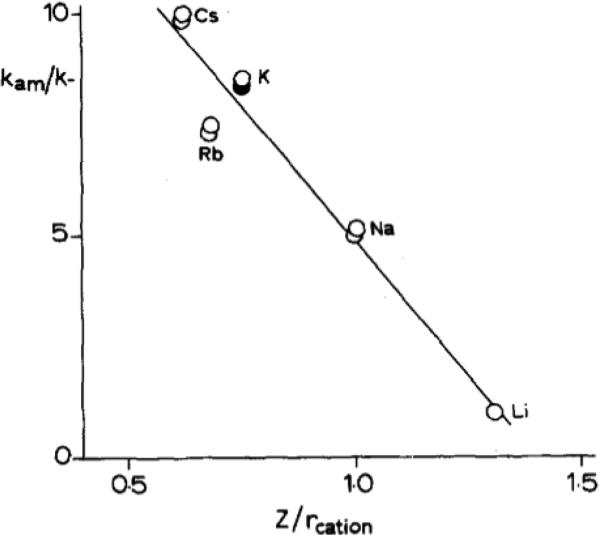

Many of the theories above can be explained through electrostatic influences of potassium on the catalyst surface. If the role of potassium as a promoter is purely electrostatic, replacing potassium in the technical catalyst with a different alkali cation should result in predictable relative enhancements to catalytic activity based on periodic trends. The depth at which the electrostatic potential of a surface is felt increases with the ionic radius of the cation, and as a result Cs+ is expected to have the largest and Li+ the smallest spatial extent of electronic effects [55]. This is often quantified through the charge-to-radius ratio (z/r) of the alkali promoter, and Mittasch catalyst activity increases with decreasing z/r (Figure 3) [34]. Bosch et al. also roughly observed this trend when testing Altenburg et al.'s theory of potassium-promoted formation of N* species in favor of NH* or NH2* species (Figure 4), demonstrating that replacement of potassium with cesium increases activity by ~20%. However, in this report the promoter effect of rubidium was found to be less than that of potassium [35].

Figure 3.

Activity of fused Fe catalyst with different alkali metal-oxides as promoters. Reprinted with permission from [34, 36]. Copyright Elsevier, 2009.

Figure 4.

Activity vs. z/r of alkali cation-promoted Fe catalyst at 10 MPa and 673 K (empty circles denote use of alkali carbonate solution, filled circles denote use of alkali hydroxide solution) Reprinted with permission from [35]. Copyright Elsevier, 1985.

In opposition to the periodic trend discussed above, some sources refer to potassium as the best alkali metal promoter for the technical H-B catalyst [28, 58]. Using the double-layer model presented above (Figure 2), the valence of the promoter cation and its ionic radius are expected to affect the density of open Fe active sites for N2 chemisorption; thus, changing the alkali cation has both electronic and structural consequences. Based on these criteria, potassium could provide the highest density of Fe(111) and Fe(100) active sites during catalysis conditions (Table 1) [51].

Table 1.

Relationship between atomic radius of electronic promoters in Fe catalysts and number of available active sites for N2 chemisorption [51].

| Promoter | atom radius (pm) | no. of promoter atoms in monolayer | no. of active sites available for N2 chemisorption | surface area (m2 g−1) | no. of active sites available for N2 chemisorption (m2 g−1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(111) | Fe(100) | Fe(111) | Fe(100) | Fe(111) | Fe(100) | Fe(111) | Fe(100) | ||

| Li | 152 | 14 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Na | 186 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 12 | 15 | 60 | 45 |

| K | 227 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 8.5 | 10 | 68 | 60 |

| Rb | 248 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 63 | 56 |

| Cs | 267 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 9.7 | 7.7 | 6 | 7 | 59 | 55 |

Lithium is predicted to be a poor promoter for the Mittasch catalyst [35, 51]. With the highest z/r ratio, lithium cations have the smallest electrostatic effect on surrounding Fe atoms, and they also lead to better hydrogen bonding of OH groups that could stabilize *N, *NH, and *NH2 [40]. In the double layer model, the lithium promoted catalyst is predicted to have no free active sites for N2 chemisorption due to geometric packing effects [51]. Previous studies experimentally support the predicted low activity of lithium-promoted catalysts (see Figures 3-4) [34, 35]. In contrast, a recent study by Arabczyk et al. reports that doping the technical catalyst with lithium hydroxide results in enhanced catalytic activity, even exceeding the activity of the industrially used catalyst per surface area unit [36]. These contradicting reports, as well as inconsistencies between Cs and Rb promoted activity, indicate that alkali metal promotion of the Mittasch catalyst is still not fully understood.

2. Using homogeneous systems to better understand alkali cation interactions

Many of the difficulties in elucidating the nature of alkali cation promotion in the technical catalyst are rooted in limitations on the ability to observe atomic-scale interactions on the surface. Additionally, surface studies on the technical catalyst are complicated by the fact that the predominant species on the surface is unlikely to be the actual active catalyst. This makes direct observation of a catalytically active Fe site interacting with the substrate and promoters exceptionally difficult.

2.1. Advantages and disadvantages of studying homogeneous systems

Studying homogeneous systems that mimic the interaction of reduced Fe (or other transition metals) with alkali metals and N2 can provide insight into these interactions with atomic-level resolution. With coordination complexes, it is much easier to isolate and characterize catalysts, products, and intermediates. X-ray crystallography can show structural details of synthetic compounds on an atomic scale, which allows the study of precise atomic interactions. Atomic-level structural resolution also provides a firm link between the structure of a synthetic compound and its spectroscopic characteristics. This correlation enables one to predict structures based on spectroscopic data, which can be vital when studying complicated interactions between multiple species in situ. Comparing the spectroscopy of homogeneous analogs to heterogeneous catalysts allows one to make predictions about interactions on the surface based on conclusions from solution studies. Additionally, it is possible to follow the changes in structures through an entire reaction pathway in solution studies. This allows homogeneous studies to target systems with the most relevant interactions and study how these interactions influence the reaction. In the context of the H-B process, effects of alkali cations on N2 activation by transition metal complexes can be quantitatively measured through various parameters: the stretching frequency of the N-N bond (νNN), which is directly correlated to the N-N bond order; bond distances between N atoms, alkali cations, and metal complexes; changes in catalyst structure due to alkali interactions; and, the reduction potentials of the metal center [59]. These parameters provide insight into structural and electronic effects of the alkali cation, even distinguishing these in favorable cases. Electronic effects of the alkali cation on the metal center, which may affect N2 activation, can be explored in homogeneous systems via cyclic voltammetry and spectroscopy.

It is important to note that, despite these advantages, homogeneous compounds can never provide a completely accurate representation of a surface. The use of solvents introduces numerous interactions (discussed in the next section) that are not present during the gas-phase conditions of ammonia synthesis. Additionally, the supporting ligands used to solubilize transition metal complexes have strong influences on the reactivity of the complexes with N2. Finally, the localized molecular orbitals in molecular complexes do not necessarily translate well to the delocalized band structure of orbitals in extended materials.

2.2. Fundamental reactivity of alkali cations in solution

When evaluating alkali cation interactions in homogeneous systems, it is important to consider the behavior of alkali cations in solution. Cations in solution engage in numerous non-covalent interactions that are not relevant in gas-solid reactions as in the H-B process. This represents a significant limitation when comparing the homogeneous systems discussed in this review to the industrial ammonia synthesis process. Cation noncovalent interactions are primarily electrostatic, so the strength of these interactions typically increases with increasing z/r of the cation [60]. In contrast, electrostatic effects from cations on a surface are more pronounced for larger cations of the same valence [55].

Solvent interactions

Alkali cations form weak bonding interactions with electronegative O- and N-donor solvents. Solvents such as THF and Et2O promote solubility of alkali cations as well as charge-transfer during multi-electron N2 reduction and are thus often employed in homogeneous N2 reduction chemistry. Solvent-cation interactions can promote rearrangement of cations in solution, leading to flexible cation-complex and cation-N2 interactions. Relevant thermodynamic measurements of alkali cations with O-donor solvents are summarized in Table 2 [61]. These thermodynamic data suggest that Li+ forms stronger interactions with O-donor solvents. This is similar to one DFT study that calculated the free energy of alkali cation adsorption to an MgO surface, predicting that Li+ binds more strongly (Eadsorption = −69.5 kJ/mol) than Na+, K+, Rb+, and Cs+ (Eadsorption = −24.1 to −27.0 kJ/mol, no trend) to the metal oxide [62]. Since Li+ is not a potent promoter of the H-B process and all other alkali cations have comparable adsorption free energies to MgO, it is unlikely that the binding energy of an alkali cation to the catalyst surface is a dominating factor towards the efficacy of that cation as a promoter.

Table 2.

Bond Dissociation Free Energies (kJ/mol) of M+-L with organic ligands for selected O-donors. Uncertainties in parentheses [61].

| M+ | L = MeOH | L = Et2O | L = THF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li+ | 152 (10) | 175 (11) | 173 (11) |

| Na+ | 92 (6) | 117 (3) | - |

| K+ | 92 (2) | 93 (6) | - |

Cation-π interactions

Cations engage in electrostatic interactions with electron density from π-orbitals of aromatic systems [63, 64]. These interactions are relatively strong, and numerous examples are known in synthetic complexes as well as isolated proteins [65]. Owing to the electrostatic nature of this interaction, the strength of cation-π interactions increases with increasing z/r (Table 3). Electron-donating substituents on the arene result in stronger cation-π interactions, although this effect is more pronounced for smaller cations [61].

Table 3.

Sequential Bond Dissociation Free Energies (kJ/mol) of M+(L)x complexes for π-ligands. Uncertainties in parentheses [61].

| M+ | L = (C6H6) | L = (MeC6H5) | L = (N,N-Me2-C6H5) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x = 1 | x = 2 | x = 1 | x = 2 | x = 1 | x = 2 | |

| Li+ | 161 (14) | 104 (7) | 183 (16) | 117 (3) | 210 (8) | 128 (4) |

| Na+ | 93 (6) | 80 (6) | 112 (4) | 87 (2) | 129 (4) | 99 (2) |

| K+ | 74 (4) | 68 (7) | 80 (5) | 75 (5) | 99 (3) | 76 (3) |

| Rb+ | 69 (4) | 63 (8) | 71 (4) | 68 (4) | 92 (2) | 72 (3) |

| Cs+ | 65 (5) | 59 (8) | 64 (4) | 62 (4) | 83 (2) | 66 (3) |

Interactions with crown ethers

Alkali cations form strong interactions with chelating macrocycles such as crown ethers and cryptands. These macrocycles are commonly employed in synthetic studies to sequester alkali cations due to the thermodynamic stability of chelated macrocycle-cation interactions over other noncovalent interactions [66-75]. The effect of alkali cation sequestration by crown ethers on alkali cation interactions to N2 will be discussed below. Relevant sequential bond dissociation energies for alkali-crown-ether complexes are listed in Table 4 [61].

Table 4.

Sequential Bond Dissociation Free Energies (kJ/mol) of M+(L)x complexes for crown ethers. Uncertainties in parentheses [61].

| M+ | L = 12-crown-4 | L = 15-crown-5 | L = 18-crown-6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x = 1 | x = 2 | x = 1 | x = 2 | x = 1 | x = 2 | |

| Li+ | 372 (51) | 135 (10) | - | - | - | - |

| Na+ | 252 (13) | 144 (10) | 294 (18) | 118 (10) | 296 (19) | - |

| K+ | 189 (12) | 135 (10) | 205 (15) | 138 (10) | 234 (13) | - |

| Rb+ | 93 (13) | 128 (10) | 114 (7) | 133 (10) | 191 (13) | - |

| Cs+ | 85 (9) | 110 (10) | 100 (6) | 125 (10) | 168 (9) | 120 (10) |

3. Effects of alkali cations on N2 activation by transition metal complexes

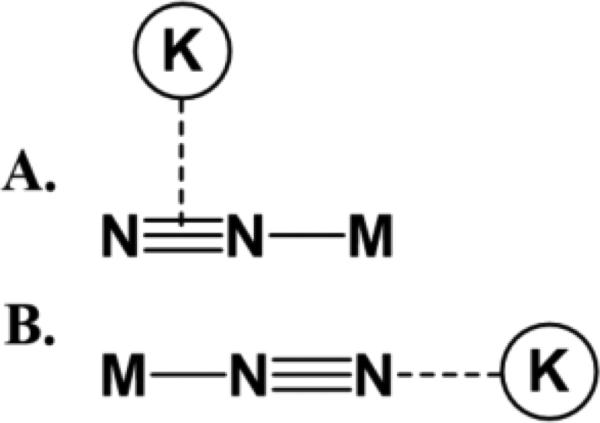

Hundreds of transition metal-N2 complexes have been described that encompass a wide variety of metals, supporting ligands, and binding motifs. Comprehensive reviews have been published detailing N2 complexes and their reactivities [59, 76-81]. In this review, we focus on N2 complexes that incorporate alkali cation interactions with the N2 ligand itself, thus demonstrating a direct influence of the alkali metal on activation of N2. Most commonly, N2 complexes that incorporate alkali cations have either an end-on interaction, where alkali cations interact with electron density from the N2 σ-orbital and promote polarization of the N2 ligand, or a side-on interaction, where alkali cations interact with electron density from N2 π-orbitals (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Side-on (A) and end-on (B) interactions of alkali cations with metal-N2 complexes.

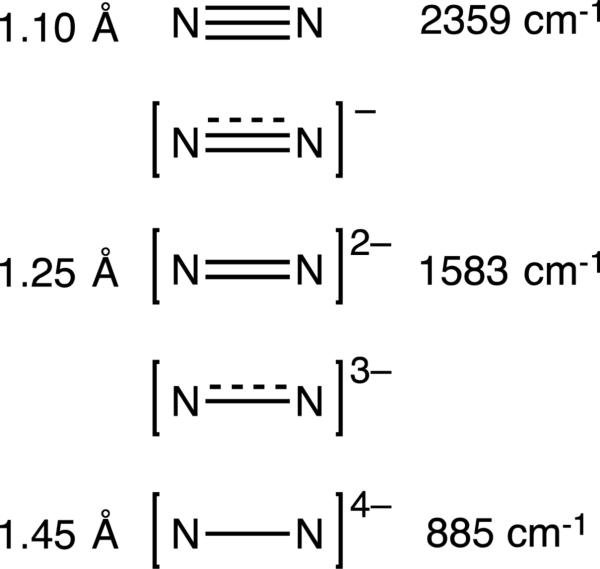

These systems are advantageous for exploring the effects of the alkali metals because they can be systematically varied and contain spectroscopic handles that quantitatively describe the degree of N2 activation. Specifically, the stretching frequency of the N-N bond (νNN, 2359 cm−1 for unbound N2) allows for the direct assessment of the strength of the N-N bond (Figure 6), with lower frequencies indicating a higher degree of reduction (due to more electron density in the π-antibonding orbitals of N2) [82]. Similarly, in a solid-state crystal structure the distance between N atoms can be measured to give another estimation of N2 reduction (1.098 Å for atmospheric N2), as longer distances imply lower bond order. When considering these quantitative measures, νNN is usually considered the more accurate indicator of N2 activation, since it can be measured in situ and is not affected by crystal-packing effects, crystal disorder, or uncertainties of the atom positions due to thermal motion.

Figure 6.

N-N bond distances and stretching frequencies of N2 in reduced forms [82].

3.1. End-on interactions between alkali cations and N2

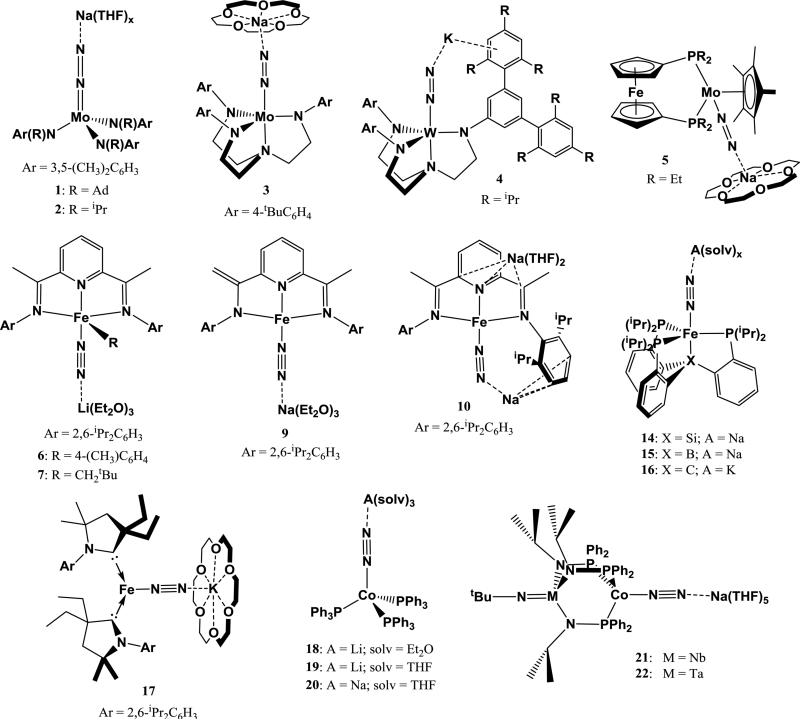

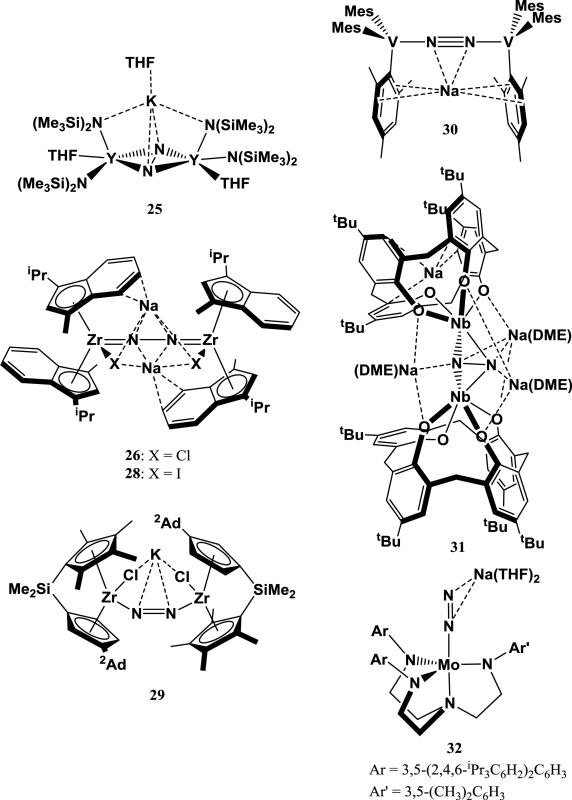

Complexes exhibiting an end-on interaction usually contain a linear M-N≡N-A motif (M = transition metal; A = alkali metal). In all cases described, the end-on interaction is resultant from reduction of a transition-metal complex under N2 with an alkali metal-based reductant. The alkali cation is stabilized by coordinating solvents (THF, Et2O), cation-π interactions with the ancillary ligand, or chelating crown ethers. Figure 7 summarizes some examples of structurally characterized transition metal-N2 complexes with an end-on interaction to an alkali cation.

Figure 7.

Transition metal N2 complexes with end-on interaction to an alkali cation.

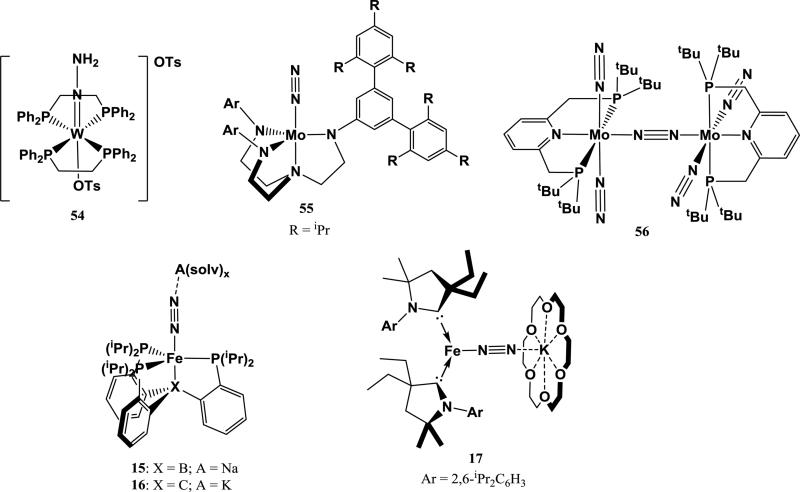

3.1.1. Molybdenum and tungsten complexes

Mo and W dinitrogen complexes have been a focus of study for N2 reduction chemistry since the discovery of Mo in nitrogenase enzymes that reduce N2 [83, 84]. Based on the early work of Chatt on stoichiometric N2 reduction to ammonia at a single Mo or W center, the chemistry of a rich variety of Mo and W dinitrogen complexes has been explored, including the electrochemical generation of NH3 from N2 by a homogeneous complex [85-87]. A few of these Mo- and W-N2 complexes exhibit end-on interactions to alkali cations. For example, Peters et al. reported that the slow cleavage of N2 by (N[R]Ar)3Mo (R = C(CD3)2CH3, Ar = 3,5-Me2C6H3) to give (N[R]Ar)3Mo≡N is facilitated by the addition of Na/Hg [88]. This reaction is proposed to proceed through an activated terminal (N[R]Ar)3Mo(N2) complex with a weak end-on interaction from Na+, which quickly reacts with another equiv of (N[R]Ar)3Mo to form [Mo(N[R]Ar)3]2(μ-N2). The μ-N2 complex cleaves N2 to form 2 equiv of (N[R]Ar)3Mo≡N over a few hours. However, reduction of the more sterically hindered (N[Ad]Ar)3Mo analog with Na/Hg prevents the formation of a bimetallic μ-N2 complex, instead halting the reaction at (N[Ad]Ar)3Mo(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 (1). 1 contains a strong end-on interaction with Na+ in the solid state. While (Ar[Ad]N)3Mo(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 does not cleave N2, the Na-bound N atom was found to form bonds with various electrophiles. A similar complex (Ar(iPr)N)3Mo(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 (2) complex also behaves as a nucleophile at the Na-coordinated N-atom, reacting with methyl tosylate to form a new N-C bond [89].

In another system, Yandulov et al. explored N2 reduction using various Mo complexes utilizing a tetradentate triamidoamine supporting ligand and discovered the first homogeneous catalyst for ammonia production from N2 [90]. Reduction of ([ArN(CH2)2]3N)MoCl (Ar = C6H5, 4-FC6H4, 4-tBuC6H4, 3,5-Me2C6H3) with 2 equiv of sodium naphthalenide results in the formation of the N2 species ([ArN(CH2)2]3N)Mo(μ-N2)Na(THF)x, which dimerize upon crystallization but are monomeric in solution [67]. These N2 complexes contain an end-on interaction with Na+, and stabilization of the cation with 15-crown-5 allowed isolation of ([4-tBuC6H4N(CH2)2]3N)Mo(μ-N2)Na(15-crown-5) (3) and ([3,5-Me2C6H4N(CH2)2]3N)Mo(μ-N2)Na(15-crown-5). Addition of Me3SiCl to the dinitrogen complexes results in silylation to form a diazenido ligand. A similar, more sterically encumbered ligand was employed for ([3,5-{2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)2C6H3N(CH2)2]3N)WCl, which forms ([3,5-{2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)2C6H3N(CH2)2]3N)W(μ-N2)K (4) upon reduction with 2.5 equiv of KC8 [96]. Interestingly, the solid-state structure of 4 shows that the K+ does not lie along the W-N=N axis, but is interacts strongly with an arene in the supporting ligand to form a bent N=N-K interaction. In this case, the cation is stabilized via cation-π interactions rather than by coordinating solvents or crown ethers. Cation exchange using nBu4NCl quantitatively removes the K+. 4 can be protonated at the nucleophilic N-atom using strong acids to form ([3,5-{2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)2C6H3N(CH2)2]3N)WN=NH and [({3,5-{2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)2C6H3N(CH2)2}3N)W=NNH2][BAr4’].

A more recent system described by Miyazaki et al. employs a Mo complex with strongly donating ferrocenyldiphosphine and pentamethylcyclopentadienyl supporting ligands [68]. Reduction of the dimer [Cp*MoCl4]2(μ-1,1’-[PEt2]2Fc) with excess Na/Hg under N2 gives [{1,1’-(PEt2)2Fc}(Cp*)Mo](μ-N2)Na(THF)x as the major product, with Na+ interacting end-on to the N2 ligand. Addition of 1 equiv of 15-crown-5 gives the isolated product [{1,1’-(PEt2)2Fc}(Cp*)Mo](μ-N2)Na(15-crown-5) (5). In contrast to triamidoamine scaffolds, 5 does not react with strong acids to form a diazenido or hydrazido complex; however, the nucleophilic N-atom reacts with Me3SiCl to form the expected silyldiazenido complex.

3.1.2. Iron complexes

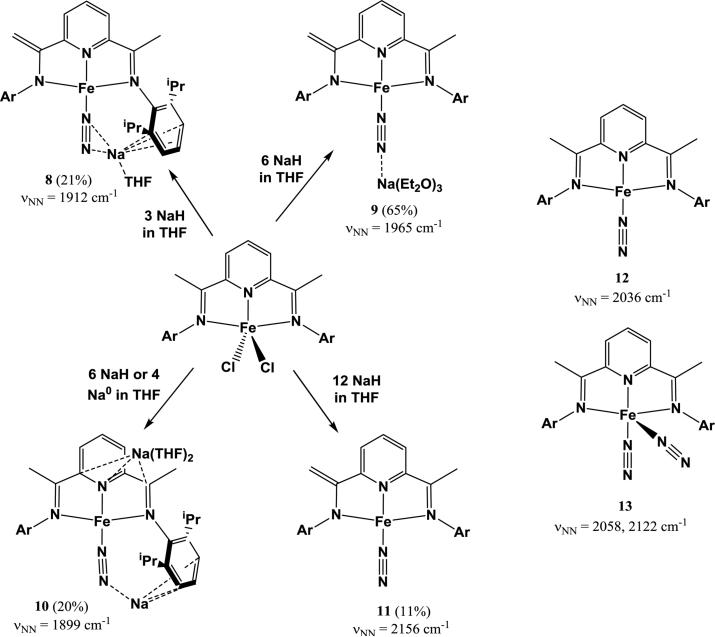

Dinitrogen reduction using homogeneous Fe complexes is of particular interest due to the discovery that N2 is reduced at a tetrairon face by the FeMo-cofactor in nitrogenase [91-93] and the use of a promoted Fe catalyst in the Haber-Bosch process. As with Mo and W dinitrogen complexes, many examples of reduction of N2 with Fe complexes via alkali metal-based reductants result in products with end-on interactions between N2 and alkali cations. For example, studies by Fernandez et al. on (PDI)Fe systems (PDI = 2,6-[2,6-iPr2PhN=C(CH3)]2(C5H3N); pyridinediimine) showed that (PDI)FeBr2 is reductively arylated with 2 equiv phenyllithium to form (PDI)Fe(Ph), which is reduced by an additional equivalent of phenyllithium to form [(PDI)Fe(Ph)](μ-N2)Li(OEt2)3 [94]. While this complex could not be crystallized, the tolyl analog [(PDI)Fe(p-tol)](μ-N2)Li(OEt2)3 (6) was prepared and crystallographically characterized to confirm the end-on Li+-N2 interaction. Despite this interaction, the N2 ligand of 6 is barely activated due to preferential reduction of the supporting ligand, exhibiting a νNN of 2068 cm−1 and N-N distance of 1.138(3) Å. A similar complex is synthesized by addition of neopentyllithium to (PDI)Fe(N2)2 to form [(PDI)Fe(CH2t2Bu)](μ-N2)Li(OEt2)3 (7). This complex has a slightly more activated N2 ligand, with νNN = 1948 cm−1 [69]. An interesting study of the reduction of (PDI)FeCl2 with NaH by Scott et al. showed a diverse array of products depending on the amount of reductant used [95]. Using 3 equiv of NaH, the reduced complex (2-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]-6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N-C=CH2]C5H3N)Fe(N2)[η2-Na(THF)] (8) was isolated, containing a side-on interaction between the N2 ligand and Na+. Using 6 equiv of NaH, two complexes containing end-on interactions between Na+ and N2 were isolated: (2-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]-6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N-C=CH2]C5H3N)Fe(μ-N2)Na(Et2O)3 (9) in which the Na+ is solvated with diethyl ether and (2,6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]2C5H3N)Fe(μ-N2)Na[Na(THF)2] (10) in which the end-on Na+ is coordinated to one of the ligand arenes (and which contains an additional Na+ coordinated to the ancillary PDI ligand). An additional reduced complex (2-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]-6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N-C=CH2]C5H3N)Fe(N2) (11), which is devoid of cation interactions, was isolated as one of the products from reduction of (PDI)FeCl2 with 12 equiv NaH. Scheme 1 summarizes the synthesis of 8-11. All three complexes containing cation-dinitrogen interactions display slight N2 activation. For the side-on coordination product 8, νNN is 1912 cm−1. 9 has a νNN of 1965 cm−1, which is significantly higher than that of 10 (νNN = 1899 cm−1). When comparing 8-10 to 11, which has a νNN of 2156 cm−1, it seems that the presence of cations significantly promotes N2 activation. However, 11 has a surprisingly high νNN, especially when compared to another neutral complex with the same supporting ligand (2,6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]2C5H3N)Fe(N2) (12), reported by Bart et al., which has a νNN of 2036 cm−1 [96]. Instead, 11 seems more closely related to the neutral bis-N2 complex (2,6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]2C5H3N)Fe(N2)2 (13), which has two N2 stretches at 2058 and 2122 cm−1 (although both stretching frequencies are still lower than that of 11). There is no clear correlation between the type of interaction of Na+ with N2 and νNN in this system.

Scheme 1.

Selected products from reduction of (PDI)FeCl2 with various equivalents of NaH (Ar = 2,6-iPr2C6H3). 12 and 13 are shown for comparison.

The Peters group has studied N2 reduction using Fe complexes supported by tris(phosphino)silane, borane, and alkyl ligands. Reduced Fe-N2 complexes using these ligands were prepared through reduction of parent halide complexes with strong alkali-based reductants. Reduction of (Si(o-C6H4P(iPr)2)3)Fe(N2) with sodium naphthalenide gives (Si(o-C6H4P(iPr)2)3)Fe(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 (14), which exhibits an end-on interaction between Na+ and N2 . 14 reacts with Me3SiCl to give the silylated diazenido product, demonstrating the nucleophilic reactivity of the distal N-atom [71]. Analogous to 14, reduction of (B(o-C6H4P(iPr)2)3)FeBr with 2.5 equiv of sodium napthalenide gives (B(o-C6H4P(iPr)2)3)Fe(μ-N2)Na(THF)x (15) [72]. Remarkably, this complex catalytically reduces N2 to NH3 with excess KC8 and HBArF4, achieving up to 64 equiv of NH3 per Fe center [97, 98]. The alkyl analog (C(o-C6H4P(iPr)2)3)Fe(μ-N2)K(Et2O)3 (16) is synthesized by the reduction of (C(o-C6H4P(iPr)2)3)FeCl with excess KC8. 16 is also catalytically active towards NH3 production from N2 with excess KC8 and HBArF4, producing 47 equiv of NH3 per Fe center [73, 98].

Ung et al. reported a low-coordinate Fe-CAAC system (CAAC = cyclic(alkyl)(amino)carbene) that, when reduced with KC8 in the presence of 18-crown-6, forms (CAAC)2Fe(μ-N2)K(18-crown-6) (17) [74]. In contrast to other examples where addition of a crown ether results in sequestration of the coordinated cation, end-on K+ still forms a contact ion pair with the anionic Fe-N2 complex even when chelated by 18-crown-6, similar to the Mo complex 3. 17 catalyzes N2 reduction to NH3, achieving 3.4 equiv of NH3 per Fe complex with excess KC8 and HBArF4.

3.1.3. Cobalt complexes

A few examples of reduced Co-N2 complexes displaying end-on cation coordination to N2 also exist. Reduction of the Co-hydride complex (P(C6H5)3)3CoH(N2) with nBuLi gives (P(C6H5)3)3Co(μ-N2)Li(Et2O)3 (18) or (P(C6H5)3)3Co(μ-N2)Li(THF)3 (19), depending on the solvent used. Alternatively, use of Na metal instead of BuLi as the reductant gives (P(C6H5)3)3Co(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 (20). In all cases, the cation interacts with the reduced N2 ligand in an end-on fashion, and addition of concentrated acid to the complexes releases substoichiometric amounts of hydrazine and ammonia (in addition to H2 and N2). This system enables two interesting comparisons: a) the effect of Li+ vs. Na+ on N2 activation and b) the effect of solvation of Li+ on N2 activation. The N-N bond in 19 (νNN = 1890 cm−1) is slightly weaker than the one in 20 (νNN = 1910 cm−1), suggesting that Li+ is a slightly better promoter for N2 activation than Na+ in this system. Et2O forms a slightly stronger bond with Li+ than THF (see Table 2), which results in greater N2 activation in 19 (νNN = 1890 cm−1) than in 18 (νNN = 1900 cm−1). Addition of 12-crown-4 to 18 magnifies this effect, increasing νNN from 1900 to 1920 cm−1. Stronger interactions between the cation and solvent molecules or chelators thus results in less N2 activation, presumably by competing with the end-on interaction between the cation and N2 [75].

In another system, Evers et al. synthesized bimetallic Co-Nb and Co-Ta complexes with weak dative interactions between the metals [99]. Reduction of the complexes under N2 with excess Na/Hg results in the formation of bimetallic N2 complexes tBuN=Nb[μ-(iPr)N-P(C6H5)2]3Co(μ-N2)Na(THF)5 (21) and tBuN=Ta[μ-(iPr)N-P(C6H5)2]3Co(μ-N2)Na(THF)5 (22), both of which exhibit end-on interactions of N2 to Na+. The identity of the ancillary metal does not affect the N-N bond order in this system (νNN = 1940 cm−1 for both complexes).

3.1.4. Summary and analysis of trends in complexes with end-on alkali binding

The aforementioned complexes with end-on alkali cation to dinitrogen interactions exhibit weakened N-N bonds in most cases, with νNN from 1757-1965 cm−1 and N-N distances from 1.220(8) to 1.035(4) Å (Table 5). The distance between the alkali metal cation and N2 shows no evident correlation with νNN. The νNN values suggest mildly reduced N2 ligands, which is also evident from the nucleophilic nature of the distal N-atom in many cases. However, since the systems described utilize widely varying metals, supporting ligands, and oxidation states, it is difficult to identify specific trends of reactivity between different alkali cations. In the case of 19 and 20, where only the alkali cation is varied, the change in νNN is marginal. Additionally, none of the complexes displaying end-on interactions to alkali cations contain Rb+ or Cs+ as the cation, further limiting the ability to identify more general periodic trends.

Table 5.

Transition metal N2 complexes with end-on interactions to an alkali cation.

| Complex | alkali cation | N-N bond length (Å) | νNN (cm−1) | cation-N distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (3,5-Me2C6H3[Ad]N)3Mo(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 (1) | Na | 1.152(8) | 1783, 1757 | 2.227(9) |

| (3,5-Me2C6H3[iPr]N)3Mo(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 (2) | Na | 1.186(8) | 1783 | 2.196(7) |

| [(4-tBuC6H4N)3N]Mo(μ-N2)Na(15-crown-5) (3) | Na | 1.161(5) | 1815 | 2.362(5) |

| ([3,5-(2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)2C6H3N(CH2)2]3N)W(μ-N2)K (4) | K | 1.220(8) | 1745 | 2.536(7) |

| [{1,1′-(PEt2)2Fc}](Cp*)Mo(μ-N2)Na(15-crown-5) (5) | Na | 1.168(7) | 1791 | 2.302(5) |

| (2,6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]2C5H3N)Fe(p-tol)(μ-N2)Li(Et2O)3 (6) | Li | 1.138(3) | 2068 | 2.092(5) |

| (2,6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]2C5H3N)Fe(CH2tBu)(μ-N2)Li(Et2O)3 (7) | Li | 1.138(3) | 1948 | 2.083(6) |

| (2-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]-6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N-C=CH2]C5H3N)Fe(μ-N2)Na(Et2O)3 (9) | Na | 1.154(6) | 1965 | 2.389(6) |

| (2,6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]2C5H3N)Fe(μ-N2)Na[Na(THF)2] (10) | Na | 1.149(6) | 1899 | 2.333(5) |

| (Si(o-C6H4P(iPr)2)3)Fe(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 (14) | Na | 1.147(4) | 1891 | 2.282(3) |

| (B(o-C6H4P(iPr)2)3)Fe(μ-N2)Na(THF)x (15) | Na | 1.149(2) | 1879 | - |

| (C(o-C6H4PCPr)2)3)Fe(μ-N2)K(Et2O)3 (16) | K | 1.153(2) | 1870 | 2.656(2) |

| (CAAC)2Fe(μ-N2)K(18-crown-6) (17) | K | 1.035(4) | 1850 | 2.726(4) |

| (P(C6H5)3)3Co(μ-N2)Li(Et2O)3 (18) | Li | 1.17(2) | 1900 | 1.96(4) |

| (P(C6H5)3)3Co(μ-N2)Li(THF)3 (19) | Li | 1.19(4) | 1890 | 2.06(9) |

| (P(C6H5)3)3Co(μ-N2)Na(THF)3 (20) | Na | - | 1910 | - |

| tBuN=Nb[μ-(iPr)N-P(C6H5)2]3Co(μ-N2)Na(THF)5 (21) | Na | 1.115(4) | 1940 | 2.489(3) |

| tBuN=Ta[μ-(iPr)N-P(C6H5)2]3Co(μ-N2)Na(THF)5 (22) | Na | 1.124(4) | 1940 | 2.484(4) |

Despite insufficient data to confidently define a periodic trend between the alkali cation identity and extent of electronic promotion on N2 activation through an end-on interaction, it is worth noting that the presence of an end-on bound alkali cation often promotes reactivity of the N2 ligand. For example, the distal N-atom in complexes 1-5 and 14 reacts with electrophiles to form new N-C, N-Si, or N-H bonds, depending on the complex. Additionally, 16 and 17 are catalysts for reduction of N2 to NH3. The potential role of the alkali cation in these catalytic systems will be discussed later in this review. It is reasonable to conclude that end-on coordination of an alkali cation promotes nucleophilicity of the N-atom due to Coulomb attraction of electron density into the terminal N atom of the N2 ligand (see below).

Despite the variation in the complexes showcasing end-on interactions, a common strategy is the sequestration of the alkali cation with a crown ether to decrease other interactions, such as cation-ligand, cation-N2, or cation-solvent interactions, in favor of coordination to the chelating macrocycle. Following this reaction spectroscopically gives insight into the direct effect that the end-on interaction has on dinitrogen activation. Most commonly, addition of a crown ether results in an increase in νNN, indicating a decrease in backbonding from loss of the direct interaction (Table 6). In one of the clearest examples, a study by Tondreau et al. showed that the 1e− reduction of (2,6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]2C5H3N)Fe(N2) (12) using sodium naphthalenide generates [(2,6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]2C5H3N)Fe(N2)][Na(THF)x] (23) and shifts the νNN from 2036 to 1917 cm−1 (the authors also report a second stretch at 1966 cm−1, attributed to different cation-coordination modes) [70]. To avoid the complicated range of products formed when reducing (PDI)Fe(N2) complexes with Na-based reductants (described above, see 8-11), Tondreau et al. added 15-crown-5 or 18-crown-6 to 23 to reduce cation interactions. They found that addition of 15-crown-5 shifts νNN higher by 39 cm−1 to 1956 cm−1 and use of 18-crown-6 shifts ν higher by 32 cm−1 to 1949 cm−1, demonstrating an increase in N-N bond order when sequestering the cation. In another case, K+ in 4 is replaced with non-coordinating nBu4N+, resulting in an increase of νNN by 56 cm−1 [100]. This suggests that the end-on coordination of an alkali cation has a direct electronic effect on the N2 ligand, facilitating backbonding from the metal into the π*-orbitals of the N2 ligand. From a molecular orbital standpoint, this can be explained through a) the polarization of orbital density and b) the shift in orbital energy induced by the proximity of a positive charge to the distal N-atom. In response to the nearby positive charge, the distal N-atom becomes more electronegative, polarizing the N2(π) HOMO towards the cation-coordinated N-atom and N2(π*) LUMO towards the metal-bound N-atom. This allows better orbital overlap between N2 π*- and metal d-orbitals, facilitating d→π* backbonding. The cation-promoted polarization also shifts the N2 π*-orbital lower in energy, making backbonding more energetically favorable. Typically, these cation-promoted electronic effects lead to greater N2 activation, resulting in a lower νNN by 26-56 cm−1 when end-on cation interactions are present. There are, however, a few exceptions to this trend. In the case of 3, there is no change of νNN when the cation is sequestered by 15-crown-5 [67]. Alternatively, the addition of 2 equiv of 12-crown-4 to 2 reportedly results in a shift of νNN from 1783 to 1728 cm−1, indicating a decrease in N-N bond order upon removal of the cation [89].

Table 6.

Effect of adding a sequestering agent to a transition metal N2 complex containing end-on interactions with an alkali cation.

| Complex | alkali cation | sequestering agent | νNN before (cm−1) | νNN after (cm−1) | Δ νNN (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Na+ | 12-crown-4 (2 equiv) | 1783 | 1728 | − 55 |

| 3 | Na+ | 15-crown-5 | 1815 | 1815 | 0 |

| 4 | K+ | nBu4N+ | 1745 | 1801 | + 56 |

| 7 | Li+ | 12-crown-4 | 1948 | 1996 | + 48 |

| 14 | Na+ | 12-crown-4 (2 equiv) | 1891 | 1920 | + 29 |

| 15 | Na+ | 12-crown-4 (2 equiv) | 1879 | 1905 | + 26 |

| 16 | K+ | 12-crown-4 (2 equiv) | 1870 | 1905 | + 35 |

| 18 | Li+ | 12-crown-4 | 1900 | 1920 | + 20 |

| 23 | Na+ | 15-crown-5 | 1917* | 1956 | + 39 |

| 23 | Na+ | 18-crown-6 | 1917* | 1949 | + 32 |

The authors also report a second stretch at 1966 cm−1 attributed to different cation-coordination modes

3.2. Side-on interactions between alkali cations and N2

In complexes with side-on interactions between alkali cations and N2, the cation interacts with the electron density in the N2 π-bonding orbitals. These complexes are once again synthesized by the reduction of precursors with alkali metal-based reductants under N2. In many cases, the N2 ligand is bridging between two metal centers, preventing any end-on interactions between N2 and an alkali cation. When this is the case, since orthogonal side-on cation interactions do not polarize the N-N bond, the N2 stretching vibration is IR-silent. Spectroscopic parameters of transition metal N2 complexes exhibiting side-on interactions with alkali cations are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Transition metal N2 complexes with side-on interactions to alkali cations.

| Complex | alkali cation | N-N bond length (Å) | νNN (cm−1) | cation-N distances (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (2-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N=CMe]-6-[2,6-iPr2C6H3N-C=CH2]C5H3N)Fe(N2)[η2-Na(THF)] (8) | Na | 1.090(5) | 1912 | 2.954(4), 2.287(5) |

| [(SiMe3N)2Y(THF)]2(μ-η2:η2-N2)(η2-K)(THF) (25) | K | 1.405(3) | 989 | 2.864(2), 2.885(2) |

| [(n5-C9H5-1-iPr-3-Me)2ZrCl]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)2 (26) | Na | 1.352(5) | - | 2.543(3), 2.619(3) |

| [(n5-C9H5-1-iPr-3-Me)2Zrl]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)2 (28) | Na | 1.316(5) | - | 2.461(3), 2.556(3) |

| [{Me2Si(η5-C5Me4)(η5-C5H3-3-2Ad)}ZrCl]2(μ-N2)(η2-K) (29) | K | 1.223(9) | - | - |

| [(2,4,6-Me3C6H3)3V]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na) (30) | Na | 1.28(2) | - | 2.55(3), 2.63(3) |

| [{p-tBu-calix[4]-(O)4}Nb]2(μ-η2:η2-N2)(μ-Na)3Na (31) | Na | 1.403(8) | - | η1: 2.33(4)*, η2: 2.5(1)* |

| [{3,5-(2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)N(CH2)2}2(3,5-Me2C6H3)N(CH2)N]Mo(N2)[η2-Na(THF)2] (32) | Na | 1.171(6) | - | 2.976(5), 2.353(6) |

| [{N(2-P(CHMe2)2-4-MeC6H3)2}Co(μ-N2-Na)]2[η2-Na(THF)2]2 (33) | Na | - | 1784 | - |

| [(meso-Me8(porph)Ru(C≡CH)]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)4 (34) | Na | 1.28(2) | - | 2.59(7)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu)2CH}Fe]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)2 (35) | Na | 1.213(4) | 1583 | 2.488(7)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu)2CH}Fe]2(μ-N2)(η2-K)2 (36) | K | 1.241(7) | 1589 | 2.70(1)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu)2CH}Co]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)2 (37) | Na | 1.211(3) | 1598 | 2.49(1)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu)2CH}Co]2(μ-N2)(η2-K)2 (38) | K | 1.220(2) | 1599 | 2.706(3)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu)2CH}Ni]2(μ-N2)(η2-K) | K | 1.143(8) | 1825 | 2.77(1)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu)2CH}Ni]2(μ-N2)(η2-K)2 (39) | K | 1.185(8) | 1696 | 2.716(9)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu)2CH}Ni]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)(η2-K) (40) | Na/K | 1.195(4) | 1689 | Na: 2.608(4)* K: 2.730(4)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu)2CH}Ni]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)2 (41) | Na | 1.192(3) | 1685 | 2.524(4)* |

| [{(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCMe)2CH}Fe]2(μ-N2)(η2-K)2 (42-K) | K | 1.215(6) | 1625 | 2.78(4)* |

Denotes average of distances

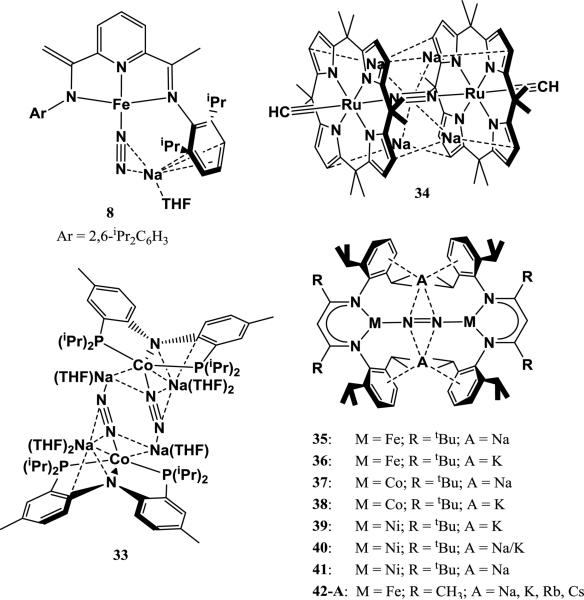

3.2.1. Group 3-6 complexes

Early transition metals activate and often completely cleave N2 since they contain high-energy dorbitals that favorably donate into the π*-orbitals of N2. In some systems, reduction of early transition metal-N2 complexes with alkali metal-based reductants leads to activated N2 complexes with side-on cation interactions (Figure 8). In one case, Evans et al. studied the reduction of N2 by Y-based trisamide complexes with KC8 [101]. They found that changing the rate and method of KC8 addition allowed the isolation of reduced μ-η2:η2-N2 dimers with varying K+ coordination. Interestingly, they were able to crystallize [(SiMe3N)2Y(THF)]2(μ-η2:η2-N2)[K(THF)6] (24), which contains a solvated K+ counter-ion, and [(SiMe3N)2Y(THF)]2(μ-η2:η2-N2)(η2-K)(THF) (25) which contains a K+ with a strong side-on interaction to N2. Raman data for 25 indicate that νNN is only 989 cm−1, which suggests an exceptionally low N-N bond order and an N23− ligand. No Raman data were collected for 24, but DFT frequency calculations predict a νNN of 1002 cm−1 for 24, which is 13 cm−1 higher than the predicted (and experimental) νNN for 25. The N-N bond distances were identical at 1.401(6) Å for 24 and 1.405(3) Å for 25. Thus the effect of direct side-on coordination of K+ to N2 in 25 compared to loosely associated K+ in 24 is small.

Figure 8.

Group 3-6 N2 complexes with side-on interactions to alkali cations.

A few Zr systems containing isolated complexes with side-on N2 interactions to alkali metal cations have been recently reported. Bis(indenyl)-Zr halide complexes can be reduced with Na/Hg under N2 to give [(η5-C9H5-1-iPr-3-Me)2ZrCl]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)2 (26), [(η5-C9H5-1-iPr-3-Me)2ZrBr]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)2 (27), and [(η5-C9H5-1-iPr-3-Me)2ZrI]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)2 (28), each of which contains two Na+ cations anchored by cation-π interactions with indenyl and cation-halide interactions. Comparing the solid state structures of 26 and 28 indicates that the N2 ligand is more reduced in 26 than in 28, with a difference in N-N bond distance of 0.036(7) Å. This was attributed to effects of the halide on the reduction potential of the metal center, but structural effects due to differences in ionic radii of the halides may also play a role. No crystal structure or spectroscopic data detailing the N-N bond of 27 was reported. Addition of H2 to 26-28 results in the formation of hydrazido complexes. Notably, attempted sequestration of the Na+ cations using 18-crown-6 or 15-crown-5 resulted in multiple products, significant structural changes, and loss of reactivity towards H2 [102]. In another system, zirconocene complex [Me2Si(η5-C5Me4)(η5-C5H3-3-2Ad)]ZrCl2 binds N2 upon reduction with KC8 but not with Na/Hg. This is more likely due to differences in reduction potential rather than alkali cation identity. The resulting complex [{Me2Si(η5-C5Me4)(η5-C5H3-3-2Ad)}ZrCl]2(μ-N2)(η2-K) (29)contains a side-on interaction with a single K+, which is coordinated to two chlorides as well [103].

An early example of a Group 5 metal-N2 complex containing side-on alkali cation interactions was reported by Ferguson et al., who reduced (2,4,6-Me3C6H3)3V(THF) with sodium metal under N2 to form [(2,4,6-Me3C6H3)3V]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na) (30). The reaction also proceeds with potassium metal, but no analogous structure was reported [104]. In another system, N2 can be cleaved into two bridging nitrides by a Nb-calix[4]arene cluster via stepwise reduction with sodium metal. Partial reduction intermediates exhibit significant side-on interactions of N2 with Na+, such as in [{p-tBu-calix[4]-(O)4}Nb]2(μ-η2:η2-N2)(μ-Na)3Na (31) [105].

In their study of Mo complexes supported with various “hybrid” tetradentate triamidoamine ligands, Weare and coworkers isolated [{3,5-(2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)N(CH2)2}2(3,5-Me2C6H3)N(CH2)N]Mo(N2)[η2-Na(THF)2] (32) from the reduction of [{3,5-(2,4,6-iPr3C6H2)N(CH2)2}2(3,5-Me2C6H3)N(CH2)N]MoCl with Na/Hg under N2. In 32, the N-N-Na angle is 110°, suggesting an intermediate side-on end-on interaction [106].

3.2.2. Group 8-10 complexes

Group 8-10 transition metal complexes with side-on alkali cation to N2 interactions are exclusively bimetallic systems with bridging N2 ligands (with the exception of 8), and only a few systems have been described (Figure 9). The first concerns a Co-pincer complex (PNP)CoCl (PNP = N(2-P(CHMe2)2-4-MeC6H3)2), which coordinates N2 upon reduction with excess sodium naphthalenide to form a dimer containing a [Co(μ-N2)Na]2 core (33). Each N2 ligand has a side-on interaction with one Na+ and pseudo-end-on interaction with another, resulting in a νNN of 1784 cm−1. Adding two extra equivalents of the parent halide (PNP)CoCl forms the bridging N2 complex [(PNP)Co]2(μ-N2) [107]. The second example comes from the reduction of a porphyrin-supported Ru-vinylidene complex with sodium metal under N2. This reduction gives [(meso-Me8(porph)Ru(C≡CH)]2(μ-N2)(η2-Na)4 (34), which has significant side-on interactions of the bridging N2 with four Na+ cations [108].

Figure 9.

Group 8-10 N2 complexes with side-on interactions to alkali cations.

The use of bidentate β-diketiminate ligands (RL, where RL = [(2,6-iPr2C6H3NCR)2CH]) to support Fe-, Co-, and Ni-N2 complexes has been extensively studied due to highly activated N2 ligands found in these complexes. Traditionally, late-group transition metals are poorly activating towards N2 ligands due to their relatively low-energy d-orbitals, which limits backbonding into the N2 π*-orbital. However, sterically bulky β-diketiminate ligands such as MeL and tBuL force the metal center to adopt a three-coordinate, pseudo-trigonal planar geometry that raises the energy of d-orbitals containing the correct symmetry for interaction with N2 π-orbitals. This facilitates N2 activation via backbonding within these complexes [109].

Stepwise N2 reduction by complexes utilizing these ligands typically proceeds by reduction of the parent complex RLMX (where R = Me, tBu; M = Fe, Co, Ni; X = Cl, Br) with 1 equiv of a strong reductant to form a bimetallic [LM]2(μ-N2) species. Subsequent reduction of this species with 1 additional equiv of a strong reductant per M gives A2[LM]2(μ-N2), where A is an alkali cation. The alkali cations show a strong side-on interaction to the N2 ligand and are stabilized by cation-π interactions with the proximal arenes. The first example was described by Smith et al., who isolated the complexes Na2[tBuLFe]2(μ-N2) (35) and K2[tBuLFe]2(μ-N2) (36) from reduction of [tBuLFe]2(μ-N2) with sodium or potassium metal, respectively. The 2e− reduction of [tBuLFe]2(μ-N2) to form 35 and 36 results in a significant decrease in the N-N bond order, evident from significant N-N bond lengthening in the solid-state structure (0.05-0.06 Å) and decrease in νNN (189-195 cm−1)[110]. The difference in alkali cation between 35 and 36 seems to have very little effect on N2 activation in this case, as N-N distances are within 0.01 Å and νNN differs only by 6 cm−1 between the complexes. Ding et al. later explored the analogous Co complexes, isolating Na2[tBuLCo]2(μ-N2) (37) and K2[tBuLCo]2(μ-N2) (38) via reduction of tBuLCoCl with excess sodium metal or 2 equiv of KC8, respectively. 37 and 38 have slightly shorter N-N bond distances and higher νNN than their Fe analogs, which is due to lower energy d-orbitals on Co compared to Fe. As with the Fe analogs, the identity of the alkali cation has little effect on the extent N2 activation [111, 112].

The first Ni analog of 36 was reported by Pfirrman et al. from the reduction of tBuLNiBr with 2 equiv of KC8 to form K2[tBuLNi]2(μ-N2) (39). Following the periodic trend of d-orbital energies, 39 exhibits a shorter N-N bond and higher νNN than its Co analog, indicating less N2 weakening. Interestingly, the authors found that reduction of tBuLNiBr with 1.5 equiv of KC8 results in the formation of K[tBuLCo]2(μ-N2), which contains a side-on interaction between the bridging N2 and a single K+ on one side [113]. Horn et al. found that reacting this partially-reduced complex with sodium metal gives the mixed-alkali product NaK[tBuLNi]2(μ-N2) (40) [114]. Furthermore, reduction of the previously reported [tBuLNi]2(μ-N2) with excess sodium metal afforded the Na2[tBuLNi]2(μ-N2) species (41), completing a series of reduced Ni-N2 species that differ only by the intercalated alkali cations. Comparison of these complexes gives insight into the effect of the alkali cation on N2 activation, since no other variables are changed. A tentative relationship between the degree of N2 activation and charge-to-radius ratio of the alkali cation is evident through Raman spectroscopy: 41 shows the lowest νNN (1685 cm−1), followed by 40 (1689 cm−1), then 39 (1696 cm−1), suggesting that Na gives more weakening than K. (However, this trend is not seen in related iron complexes; see below). This trend does not extend to N-N bond distances in the solid-state structures of 39-41, which are all identical within uncertainty limits.

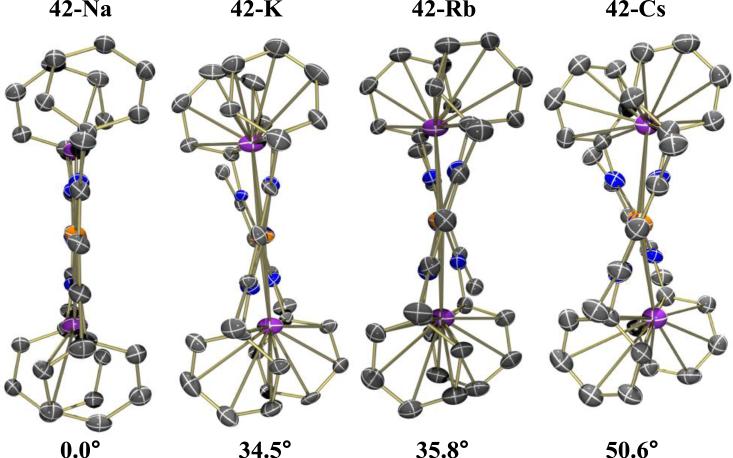

Reduced N2 complexes featuring the less bulky ligand MeL have also been reported. The reduction of [MeLFeCl]2 with 2 equiv of KC8 gives K2[MeLFe]2(μ-N2) (42-K), which contains side-on interactions between N2 and two K+ cations. This complex has a slightly shorter N-N bond distance in the solid state structure (1.215(6) Å) when compared to 36 and a slightly stronger νNN (1625 cm−1) [115]. Recently, this system was chosen by McWilliams et al. for a systematic study of effects that changing the alkali cation may have on N2 activation or bimetallic structure. Na2[MeLFe]2(μ-N2) (42-Na) was synthesized via reduction of [MeLFeBr]2 with excess sodium metal, while Rb2[MeLFe]2(μ-N2) (42-Rb) and Cs2[MeLFe]2(μ-N2) (42-Cs) were synthesized via reduction of [MeLFeBr]2 with 2 equiv RbC8 or CsC8, respectively. Spectroscopic and crystallographic parameters from this series of complexes are summarized in Table 8. Changing the alkali cation results in only minor changes in N-N bond distance, νNN, and Mössbauer isomer shift (an indicator of electron-richness of the Fe center). This implies that changing the charge-to-radius ratio of the side-on cation has very little effect on the ability for the Fe metal to reduce N2. However, the radius of the alkali cation was shown to influence the relative solid-state geometries of the backbone ligands: the diketiminate backbone rotates and aryl-substituents twist to accommodate the larger cations in 42-K, 42-Rb, and 42-Cs. The ligand distortion results in higher torsion angles between the two Fe-N-C-C-C-N planes as the radius of the cation increases (Figure 10). Cation to N-atom distances also increase with the radius of the cation. In the case of 42-Na, Na+ is not large enough to fill the entire arene cavity, which is evident by elucidation of two crystallographically independent structures with slight shifts in Na+ positions within the cavity. The inability for Na+ to fill the cavity and maximize cation-π stabilizing interactions results in the decomposition of 42-Na in THF. In contrast, 42-K, 42-Rb, and 42-Cs are all stable in THF, and cation-exchange experiments with triflate salts suggest that they have relatively similar stabilities. Attempts to synthesize Li2[MeLFe]2(μ-N2) were unsuccessful, presumably because the small radius of Li+ makes it even more inept at filling the arene cavity, resulting in decomposition [116].

Table 8.

Effect of different alkali cations on N2 activation by β-diketiminate iron complexes [116].

| Complex | N-N bond distance (Å) | νNN (cm−1) | cation-N distances (Å) | δ (mm/s) | |ΔEQ| (mm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42-Na | 1.254(6) | 1612 | 2.51(7)* | 0.44 | 2.52 |

| 42-K | 1.215(6) | 1625 | 2.78(4)* | 0.47 | 2.48 |

| 42-Rb | 1.257(6) | 1621 | 2.91(5)* | 0.46 | 2.34 |

| 42-Cs | 1.33(2) | 1613 | 3.09(2)* | 0.48 | 2.20 |

Denotes average of distances

Figure 10.

Effect of alkali cation on twisting of FeNNFe core, with torsion angle listed [116].

When studying the reduction of [LM]2(μ-N2) to A2[LM]2(μ-N2), it is unclear what effect the side-on interaction of the alkali cations has in the mechanism of this reduction, since an intermediate in which only cation intercalation or only 2e− reduction occurs has never been elucidated. Additionally, attempts to remove the alkali cations from the arene cavities (similar to the sequestration of end-on alkali cations previously discussed) resulted in decomposition of the complex. To address this dilemma, Smith et al. used computational methods in an attempt to identify the separate contributions that the 2e− reduction and cation intercalation have towards reducing N2 in 42-K. To the truncated model compound LFe-N , 1e− and two side-on cations were added sequentially. Reduction of LFe-N2 by 1e− to [LFe-N2]− resulted in lengthening of the N-N bond by 0.036 Å, and subsequent addition of 2 Na+ resulted in further lengthening of the N-N bond by 0.032 Å (0.017 Å for 2 K+). The fact that electron addition and alkali cation coordination activate N2 by similar amounts suggests that these steps act cooperatively [115]. In a separate study, Ding et al. sought to determine whether N2 activation in 38 was primarily due to reduction of the Co or coordination of the alkali cations. Once again, computations indicated that both steps significantly reduce the N-N bond order, suggesting a cooperative interaction between the reduced Co center and side-on coordinated cations to activated N2 [112]. In both cases, it is likely that the presence of the positive charge proximal to the N2 encourages backbonding that increases electron density near the cation. In this sense, the influence is similar to that postulated in the Fe-based H-B catalyst.

3.2.3. Analysis of trends in complexes with side-on alkali binding

The studies on N2 reduction by late-group β-diketiminate complexes allows some understanding of the role of alkali cations in the stepwise reduction of N2 by these complexes. Side-on coordinated cations clearly stabilize the structure of the A2[LM]2(μ-N2) motif through cation-π interactions with ligand-based arenes, because sequestration of the cations in coordinating solvents (42-Na) or with crown ethers (42-K) eliminates the formation of these bimetallic complexes. Additionally, the conformational shifts of the supporting diketiminate ligand to accommodate larger cations in 42-Rb and 42-Cs suggests that the cation itself plays a large role in determining the overall structure of the complex. However, it is unclear whether the structural contribution of the cations is to facilitate greater N2 reduction by influencing the geometry of reaction intermediates or whether the cations merely stabilize the reduced product. In the case of 26-28, removal of coordinated cations results in significant structural changes and loss of reactivity of the complex towards H2, which suggests that cation interactions may indeed play a role in organizing reactive intermediates in multi-step N2 reduction.

The electronic effects of side-on coordinated alkali cations are even more difficult to elucidate. Comparison of the various alkali cation analogs of 42 indicates that, when the cation interaction is present, changing z/r of the cation does not impact the extent of N2 activation. This observation is consistent in other systems where only the alkali cation identity is varied: comparisons between 39-41, between 37 and 38, and between 35 and 36 show no appreciable change in N2 activation. Additionally, tight ion-pairing with side-on coordination of K+ to N2 in 25 rather than solvent-separated ion-pairing of K+ in 24 does not affect activation of the N2 ligand, which implies that proximity of the K+ cation does not have an electronic effect in that system. Computations suggest that side-on interactions of alkali cations to N2 cooperate with reduction of the metal center to enhance overall N2 ligand activation. This hypothesis has not been tested experimentally due to the inability to isolate the cation-deficient anionic analogs of any of the complexes discussed in this section. The origin of this cooperative effect from a molecular orbital standpoint has so far only been described vaguely in the literature [115]. A system that allows the independent addition/removal of electrons and alkali cations would be particularly insightful towards determining the specific electronic effects of side-on alkali cation coordination to N2.

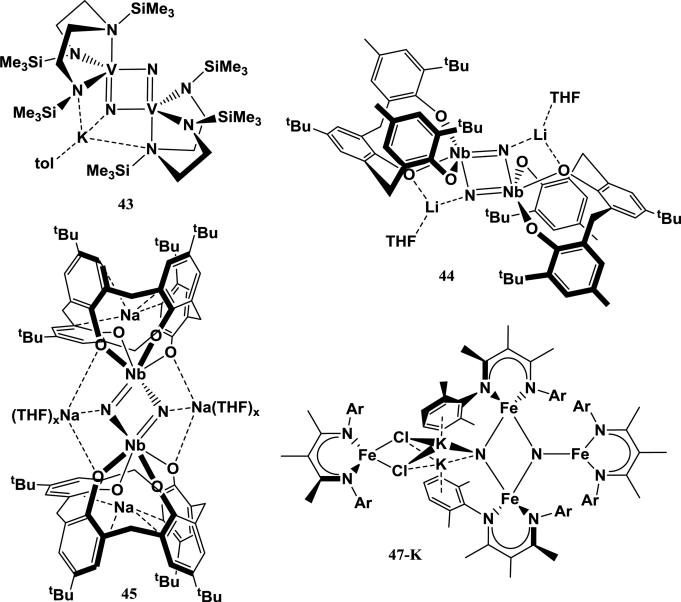

4. Effects of alkali cations on N2 cleavage by transition metal complexes

The rate-limiting step of catalytic NH3 production in the Haber-Bosch process is thought to be the initial homolytic cleavage of N2 to form absorbed nitride species. To better understand how alkali cations could facilitate the complete cleavage of N2, it is useful to study homogeneous systems in which N2 cleavage is closely associated with alkali cation interactions. Only a few such examples have been described so far, but each of them utilize multiple metal sites to split N2 into bridging nitrides, which are stabilized by nitride-cation interactions (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Cation-assisted N2 cleavage by transition metal complexes.

4.1. Vanadium and niobium complexes

Early group transition metal complexes that achieve cation-facilitated N2 cleavage include a V diamidoamine complex that binds and cleaves N2 upon reduction with 2 equiv of KC8 to form the bridging V2(N)2 complex K[{(Me3SiNCH2CH2)2(Me3Si)N}V]2(μ-N)2 (43). The K+ is coordinated to the diamidoamine ligand and one of the bridging nitrides [117]. In another system, reduction of a dimeric Nb complex supported with a tridentate tris-phenoxide ligand with 6 equiv LiBHEt3 enables N2 cleavage to form a Nb2(μ-N)2 complex (44) that is similar to 43. Once again, cations are coordinated to the bridging nitrides and supporting ligand [118]. Another Nb system supported with a tetradentate calix[4]arene ligand can achieve stepwise N2 cleavage upon reduction with sodium metal. Some products with partially reduced N2 show side-on Na+ to N2 interactions (as discussed earlier, see 31), and the product in which N2 is completely cleaved to two bridging nitrides shows coordination of a Na+ cation to each of the nitrides (45) [105].

4.2. Iron complexes

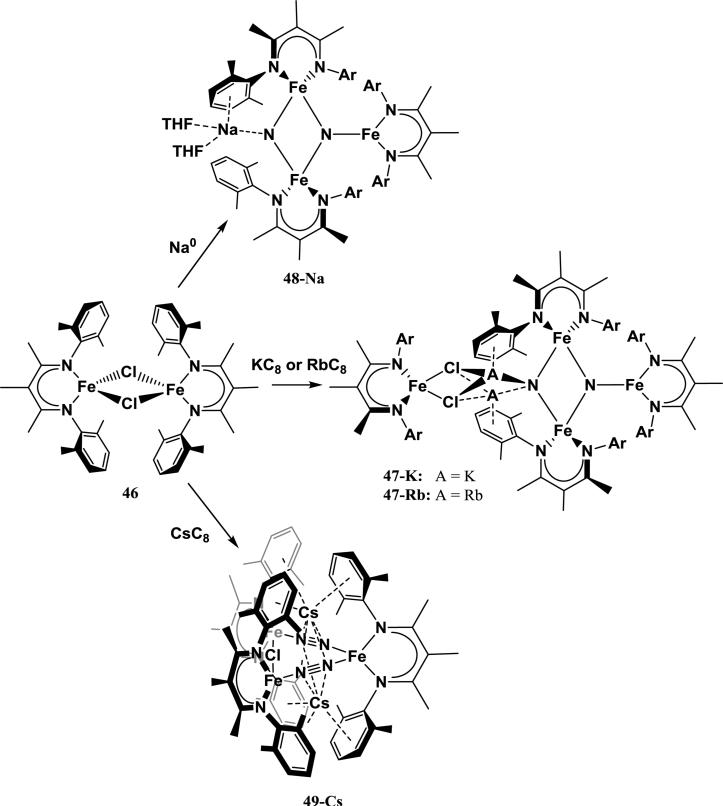

Fe-based homogeneous systems that cleave N2 serve as the best analogies to N2 reduction by the Mittasch catalyst, which utilizes a potassium-promoted Fe surface. The first Fe system that can reversibly cleave and regenerate N2 was described by Rodriguez et al., in which reduction of the β-diketiminato Fe complex [({2,6-Me2C6H3NCMe}2CMe)Fe(μ-Cl)]2 (46) with 2 equiv KC8 results in the cleavage of N2 to form a tetrairon bis-nitride complex (47-K) [119]. In the product, the two nitrides bridge a triiron cluster, with one of the nitrides stabilized by two coordinating K+ cations. These cations are anchored by cation-π interactions with arenes from the triiron core as well as coordination to a fourth Fe dichloride moiety. This tetrairon bis-nitride species quantitatively releases N2 when 12 equiv of a strongly coordinating ligand (CO, benzonitrile) are added [120]. The specific role that K+ plays in this reaction was explored in a computational study by Figg et al., who used DFT studies to examine the sequential addition of Fe1+-β-diketiminate fragments to free N2 [121]. The authors found that N2 cleavage to the bis-nitride is only achieved when three Fe1+ fragments work cooperatively. The presence of a K+ ion coordinated to the bis-nitride cluster was found to significantly stabilize the nitride product relative to the Fe3(N2) isomer. Thus the N2 cleavage becomes thermodynamically favorable when the K+ cation can interact with the nitrides. Interestingly, the stabilizing effect of K+ towards the bis-nitride product is lessened in polar solvents relative to nonpolar solvents or the gas phase, suggesting that a tight cation-nitride interaction in a nonpolar environment is ideal.

Another study by Grubel et al. on this system investigated the effects of changing the coordinating alkali cations (Scheme 2) [122]. In analogy with the synthesis of 47-K, 46 can be reduced with sodium metal, RbC8, or CsC8. Reduction of the parent halide with 2 equiv of RbC8 gives a tetriiron bis-nitride complex analogous to 47-K containing Rb+ cations in the place of K+ cations (47-Rb). 47-Rb features the same Fe3N2 core as its K+-containing analog, but the Rb+ cations are slightly closer to the “terminal” nitride and slightly distanced from the coordinated arenes. The thermal stability of 47-Rb in benzene is higher than that of 47-K, which suggests that the larger Rb+ ions more effectively fill the nitride-arene cavity than K+ (similar to the relative stability of 42-K vs. 42-Na). The relative stability of 47-Rb over 47-K is confirmed by treatment of 46 with 2 equiv of RbOTf, which results in complete cation exchange to form 47-Rb.

Scheme 2.

Products from reduction of 46 with 2 equiv of different alkali-based reductants [122].

Interestingly, reduction of the parent halide with sodium metal or CsC8 does not give an analogous tetrairon bis-nitride product. Reduction of 46 with excess sodium metal results in the formation of a triiron bis-nitride complex (48-Na) in which the “terminal” nitride is capped with a single Na+ cation. The Na+ is also coordinated to a ligand-based arene and two THF molecules. Interestingly, 48-Na is more thermodynamically stable than 47-K and 47-Rb, both of which convert to 48-Na upon treatment with excess NaOTf. Reduction of 46 with 2 equiv of CsC8, on the other hand, gives a triiron bis-N2 complex with a Fe3(μ-η1:η1-N2)2Cl core with two Cs+ cations intercalated between ligand-based arenes (49-Cs). This complex is only partially reduced, which is evident by retention of the chloride ligand. The lack of a cleaved N2 unit is surprising considering that the reducing equivalents and reducing power used to synthesize 49-Cs should be at least as great as in the Na, K, and Rb analogs [122].

4.3. Analysis of trends in N2 cleavage involving alkali-metal cations

Studies on the N2-cleaving Fe system provide insight into the role that alkali cations may play in cooperative reduction of N2 by multiple iron sites. Plausible roles that the K+ could play in this system include structurally organizing participating Fe complexes into the necessary geometry for N2 reduction, thermodynamically promoting N2 reduction by stabilizing the reduced products, or facilitating N2 reduction electronically by promoting back-bonding from Fe complexes into the N2 π*-orbital. The DFT calculations by Figg et al. suggest that stabilization of the bis-nitride product by K+ cations is vital for thermodynamically favoring the 6e− reduction of N2 by the electron-rich Fe sites [121]. These calculations also suggest that the alkali metal-N2 interaction may be more pronounced in non-polar solvents, which is a closer approximation of the gas phase Haber-Bosch conditions.

Changing the alkali cation used during reduction of 46 results in the formation of reduced multiiron clusters containing Na+, K+, Rb+, and Cs+ cations. However, while the reduction of 46 with these reductions is related, cation identity has pronounced effects on the product generated, as evident by the stark differences in structure between 48-Na, 47-K and 47-Rb, and 49-Cs. The variability in the structures of these products prevents quantitative comparison of electronic effects that the alkali cations may have, which are normally established by comparison of N-N bond distances, stretching frequencies, and reduction potentials. However, the relative stability of 47-Rb over 47-K suggests that the ability for the cation to efficiently fill the arene-nitride cavity is more important than the strength of cation-π interactions when determining overall stability of the complex. Since K+ has a higher charge-to-radius ratio than Rb+, it has a stronger electrostatic interaction with the π-orbitals of arenes (see Table 3). If this were the dominating stabilizing factor, 47-K would be more stable relative to 47-Rb. Furthermore, it is evident from this study that the use of Cs+ prohibits complete cleavage of N2 in this system. The possible origin of this observation will be discussed in the next section.

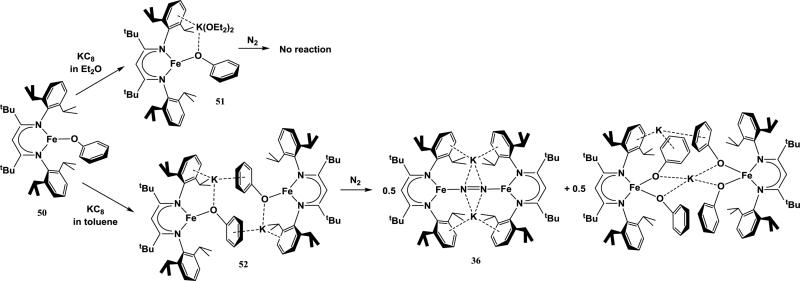

5. Structural influences from cations leading to changes in reactivity with N2

While some studies of alkali cations affecting the structure of N2 complexes were discussed in the previous sections, the extent to which alkali cations can influence reactivity of complexes towards N2 in these systems is unclear. In the examples above, reduction and cation coordination is done in tandem with N2 activation. A recent study by Chiang et al. shows that the cation influences on the structure of a reduced metal complex can influence its ability to bind N2 [123]. In this study, reduction of a β-diketiminate-supported Fe-phenolate complex ([2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu]2CH)Fe(OC6H5) (50) with 1 equiv KC8 in the absence of N2 results in an Fe1+ complex with K+ intercalation, forming an Fe-O-K subunit. However, the structure of the reduced complex is dependent on solvent interactions, resulting in a monomeric [({2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu}2CH)Fe(OC6H5)][K(OEt2)2] complex (51) in diethyl ether but a dimeric K2[({2,6-iPr2C6H3NCtBu}2CH)Fe(OC6H5)]2 complex (52) in toluene. In 51, K+ is coordinated to the phenolate O-atom, one of the diketiminate arenes, and two Et2O molecules. Alternatively, 52 contains K+ cations that are coordinated to a phenolate O-atom and locked between two arenes (one diketiminate and one phenolate) to form two strong cation-π interactions for each K+. The change in structure in coordinating solvent (Et2O) is attributed to the ability of Et2O ligands to stabilize the K+ in the complex's monomeric form. Interestingly, the dimeric structure of 52 seems to be necessary for reactivity of the reduced Fe complex with N2. Under N2 atmosphere, 52 binds N2 to form the reduced bridging N2 complex 36, but the monomeric complex 51 does not (Scheme 3). The structure-reactivity dependence was further demonstrated by addition of crown ethers (18-crown-6 and cryptand-222) to 52, which results in separation of the K+ ion from the iron-phenoxide. 52 no longer reacts with N2 when these crown ethers are present, suggesting that removing the K+ breaks up the dimeric structure that is necessary for N2 binding. This supports the hypothesis that alkali cations can facilitate the organization of key intermediate structures that are necessary for N2 binding and activation.

Scheme 3.

Structure-dependent N2 cleavage by Fe-O-K complex [123].

This study is particularly relevant to the Haber-Bosch process because it involves N2 activation by an Fe-O-K subunit, which mimics the Fe-O-K sites on the surface of the Mittasch catalyst (see Figure 2). In 52, oxygen bridges provide important interactions for holding the K+ and Fe atoms in a geometry that allows N2 binding, which suggests that it is reasonable for the oxygen bridges in the Mittasch catalyst to play a similar role during catalytic N2 reduction. Additionally, the inability of 51 (and other structures that separate K-O interactions) to bind N2 suggests that cooperation between multiple iron sites may play a key role in N2 reduction in both this system and the Haber-Bosch process.

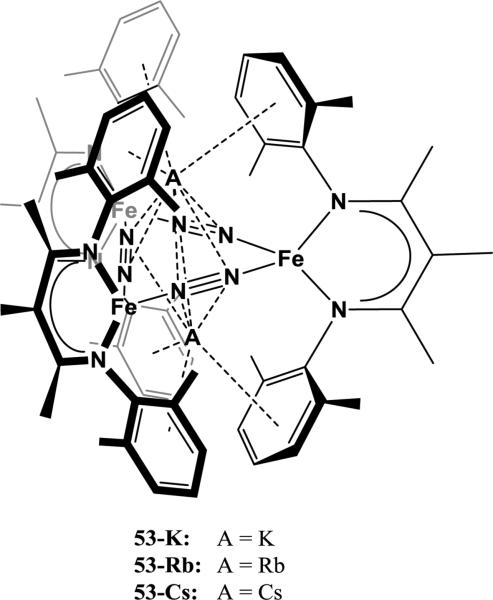

The structural influence of alkali cations on reactivity of reduced Fe complexes with N2 was further explored in the study by Grubel et al. [122]. While reduction of the parent halide complex 46 with 2 equiv of KC8 or RbC8 results in complete reduction of N2 to form bis-nitride complexes (47-K and 47-Rb), reduction of 46 with 4 equiv of KC8 or RbC8 results in incomplete reduction of N2. Instead, the reduction yields trinuclear complexes with A2[Fe(μ-N2)]3 cores (A = K, 53-K; A = Rb, 53-Rb). An analogous complex is formed by the reduction of 46 with 4 equiv of CsC8 (53-Cs), which is once again different from the reduction product when 2 equiv of CsC8 are used (49-Cs). The alkali cations in these trinuclear complexes are intercalated between three ligand-based arenes, out of the [Fe(μ-N2)]3 plane (Figure 12). In all three of these cases, the reducing power and number of equivalents of the reductant should be similar, which suggests that the limiting parameter in N2 cleavage in these systems is actually the available geometries of FexN2Ax species formed during the reduction [122]. As mentioned above, DFT studies suggest that N2 cleavage is achieved cooperatively by three Fe1+ fragments and promoted by the stabilizing effects of the alkali cation [121]. Consequently, studies of Fe-diketiminate complexes in which the ligand is too sterically bulky to allow access of a third Fe1+ fragment show that these systems are unable to completely cleave N2 [115]. Similarly, the cation-arene interactions in 53-K, 53-Rb, and 53-Cs when extra alkali cation equivalents are present organize the formation of bulky trinuclear cores in which only two Fe1+ fragments can interact with any one N2 ligand, preventing N2 cleavage. This supports the hypothesis that the way cations organize the geometry of reduced Fe fragments directly affects the ability for the Fe to reduce N2. However, in this system the geometry of Fe1+ subunits is dominated by cation-π interactions. Since the technical Mittasch catalyst does not contain arenes, this is not directly relevant to the Haber-Bosch process. A future challenge is thus to design and study homogeneous systems in which cation-π interactions are less dominant or eliminated altogether.

Figure 12.

Products from reduction of 44 with 4 equiv of different alkali-based reductants [122].

6. Comparing alkali cation promotion of homogeneous N2 reduction to alkali cation promotion of the Haber-Bosch process

The effect of alkali cation interactions with N2 ligands of transition metal complexes depends heavily on the geometry. When coordinated to N2 in an end-on fashion, alkali cations are often electronic promoters, which is evident from experiments that sequester end-on alkali cations with crown ethers. This effect can be explained from a molecular orbital standpoint, suggesting that the alkali cation promotes backbonding from metal d-orbitals into the N2 π*-orbitals. This provides strong evidence that N2 molecules bound to a metal can be further activated by a proximal electropositive alkali metal. Unfortunately, to our knowledge there has been no systematic study of the effect of alkali cation identity on N2 activation in end-on systems.