Abstract

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is an aggressive malignancy caused by the accumulation of genomic lesions that affect the development of T-cells. Since many years, it has been established that deregulated expression of transcription factors, impairment of the CDKN2A/2B cell cycle regulators and hyperactive NOTCH1 signaling play prominent roles in the pathogenesis of this leukemia. In the past decade, systematic screening of T-ALL genomes by high resolution copy number arrays and next- generation sequencing technologies has revealed that T-cell progenitors accumulate additional mutations affecting JAK/STAT signaling, protein translation and epigenetic control, providing novel attractive targets for therapy. In this review, we provide an update on our knowledge on T-ALL pathogenesis, on the opportunities for the introduction of targeted therapy and on the challenges that are still ahead.

Introduction

The characterization of chromosomal abnormalities, such as 9p deletions resulting in inactivation of CDKN2A (p16) and CDKN2B (p15) and translocations affecting the T-cell receptor genes, have been fundamental in providing initial insights in the genetic defects present in T-ALL. The incorporation of gene expression profiling has provided an additional view on the subgroups present in T-ALL, each characterized by the presence of specific chromosomal aberrations leading to ectopic expression of one particular transcription factor such as TAL1, TLX1, TLX3 or others. Sequencing approaches focusing on candidate oncogenes or more recently genome wide sequencing (exome sequencing, whole genome sequencing or transcriptome sequencing) have identified more than 100 genes that can be mutated in T-ALL. Only two of these genes, NOTCH1 and CDKN2A/2B are mutated in more than 50% of T-ALL cases, and a large variety of genes is mutated at lower frequency (Table 1). Based on all available genomic data, we can conclude that each T-ALL case contains probably more than 10 biologically relevant genomic lesions, each contributing to the transformation of normal T-cells into an aggressive leukemia cell with impaired differentiation, improved survival and proliferation characteristics, and altered metabolism, cell cycle and homing properties. These changes help the T-ALL cells to proliferate and survive by changing their own behavior as well as to interact effectively with normal cells, which further supports their stem cell characteristics and the survival of these high numbers of abnormal T-cells.

Table 1. Mutation frequencies in adult versus pediatric T-ALL.

| Gene | Type of genetic aberration | Frequency (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric | Adult | |||||

| NOTCH1 signaling pathway | ||||||

| FBXW7 | Inactivating mutations | 14 | 14 | |||

| NOTCH1 | Chromosomal rearrangements/Activating mutations | 50 | 57 | |||

| Cell cycle | ||||||

| CDKN2A | 9p21 deletion | 61 | 55 | |||

| CDKN2B | 9p21 deletion | 58 | 46 | |||

| RB1 | Deletions | 12 | ||||

| Transcription factors | ||||||

| BCL11B | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 10 | 9 | |||

| ETV6 | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 8 | 14 | |||

| GATA3 | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 5 | 3 | |||

| HOXA (CALM-AF10, MLL-ENL and SET-NUP214) | Chromosomal rearrangements/inversions/expression | 5 | 8 | |||

| LEF1 | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 10 | 2 | |||

| LMO2 | Chromosomal rearrangements/deletions/expression | 13 | 21 | |||

| MYB | Chromosomal rearrangements/duplications | 7 | 17 | |||

| NKX2.1/NKX2.2 | Chromosomal rearrangements/expression | 8 | ||||

| RUNX1 | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 8 | 10 | |||

| TAL1 | Chromosomal rearrangements/5′ super-enhancer mutations/deletions/expression | 30 | 34 | |||

| TLX1 | Chromosomal rearrangements/deletions/expression | 8 | 20 | |||

| TLX3 | Chromosomal rearrangements/expression | 19 | 9 | |||

| WT1 | Inactivating mutation/deletion | 19 | 11 | |||

| Signaling | ||||||

| AKT | Activating mutations | 2 | 2 | |||

| DNM2 | Inactivating mutations | 13 | 13 | |||

| FLT3 | Activating mutations | 6 | 4 | |||

| JAK1 | Activating mutations | 5 | 7 | |||

| JAK3 | Activating mutations | 8 | 12 | |||

| IL7R | Activating mutations | 10 | 12 | |||

| NF1 | Deletions | 4 | 4 | |||

| KRAS | Activating mutations | 6 | 0 | |||

| NRAS | Activating mutations | 14 | 9 | |||

| NUP214-ABL1/ABL1 gain | Chromosomal rearrangement/duplication | 8 | ||||

| PI3KCA | Activating mutations | 1 | 5 | |||

| PTEN | Inactivating mutations/deletion | 19 | 11 | |||

| PTPN2 | Inactivating mutations/deletion | 3 | 7 | |||

| STAT5B | Activating mutations | 6 | 6 | |||

| Epigenetic factors | ||||||

| DNMT3A | Inactivating mutations | 1 | 14 | |||

| EED | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 5 | 5 | |||

| EZH2 | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 12 | 12 | |||

| KDM6A/UTX | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 6 | 7 | |||

| PHF6 | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 19 | 30 | |||

| SUZ12 | Inactivating mutations/deletions | 11 | 5 | |||

| Translation and RNA stability | ||||||

| CNOT3 | Missense mutations | 3 | 8 | |||

| mTOR | Activating mutations | 5 | ||||

| RPL5 | Inactivating mutations | 2 | 2 | |||

| RPL10 | Missense mutations | 8 | 1 | |||

| RPL22 | Inactivating mutations/deletion | 4 | 0 | |||

| %<5 | 5≤%<10 | 10≤ %<15 | 25>%>50 | %>50 | ||

Genes targeted by genetic alterations in more than 2% of T-ALL cases are shown in the table. Calculation of the different frequencies is based on several previously published independent studies that analyzed pediatric and/or adult T-ALL patient cohorts. For frequency calculations, chromosomal rearrangements, copy number variations and mutations were considered. For HOXA, TLX1, TLX3, TAL1, NKX2.1, NKX2.2 and LMO2, also gene expression was considered. The HOXA group includes cases that are positive for CALM-AF10, SET-NUP214 or MLL-ELN chromosomal rearrangements. Frequencies are indicated in gray when it was not possible to have separate numbers for pediatric and adult cases.

Transcription factors

Careful gene expression profiling of T-ALL cases has led to the identification of subgroups of T-ALL, each characterized by a specific transcriptional profile and the ectopic expression of one particular transcription factor, often as a consequence of a chromosomal defect. The largest subgroup is defined by ectopic TAL1 expression (in some cases together with LMO1/LMO2), while other major subgroups show mutual exclusive expression of TLX1, TLX3, HOXA9/10, LMO2 or NKX2-1 (Table 2).1–3 Furthermore, the early T-cell precursor subgroup (ETP-ALL) corresponds to immature T-ALLs expressing ETP/stem cell genes, is characterized by aberrant expression of LYL1,2 and hematopoietic transcription factors such as RUNX1 and ETV6 are frequently mutated in this genetically heterogeneous subgroup.1,4

Table 2. Chromosomal rearrangements resulting in ectopic expression of transcription factors or the generation of fusion genes with transcriptional/epigenetic activity.

| chromosomal rearrangement or mutation | partner gene 1 (oncogene) | chromosome location | partner gene 2 | chromosome location | consequence of the rearrangement/mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Major transcription factors | |||||

| del(1)(p32p32) | TAL1 | 1p32 | STIL | 1p32 | Ectopic TAL1 expression driven by STIL promoter |

| t(1;14)(p32;q11) | T-cell receptor α | 14q11 | Ectopic TAL1 expression driven by TCR enhancer | ||

| t(1;14)(p32;q11) | T-cell receptor δ | 14q11 | Ectopic TAL1 expression driven by TCR enhancer | ||

| small insertion | – | - | Ectopic TAL1 expression driven by de novo enhancer | ||

| t(10;14)(q24;q11) | TLX1 | 10q24 | T-cell receptor α | 14q11 | Ectopic TLX1 expression driven by TCR enhancer |

| t(7;10)(q34;q24) | T-cell receptor β | 7q34 | Ectopic TLX1 expression driven by TCR enhancer | ||

| t(10;14)(q24;q11) | T-cell receptor δ | 14q11 | Ectopic TLX1 expression driven by TCR enhancer | ||

| t(5;14)(q35;q11) | TLX3 | 5q35 | T-cell receptor δ | 14q11 | Ectopic TLX3 expression driven by TCR enhancer |

| t(5;14)(q35;q32) | BCL11B | 14q32 | Ectopic TLX3 expression driven by BCL11B | ||

| inv(7)(p15;q34) | HOXA9/HOXA10 | 7p15 | T-cell receptor β | 7q34 | Ectopic expression of HOXA genes, predominantly HOXA9 and HOXA10, driven by TCR enhancer |

| t(10;11)(p13;q14) | PICALM (CALM) | 11q14 | MLLT10 (AF10) | 10p13 | PICALM-MLLT10 fusion transcript, resulting in upregulation of HOXA genes |

| del(9)(q34;q34) | SET | 9q34 | NUP214 | 9q34 | SET-NUP214 fusion transcript, resulting in upregulation of HOXA genes |

| inv(14)(q11;q13) | NKX2-1 | 14q13 | T-cell receptor α | 14q11 | Ectopic NKX2-1 expression driven by TCR enhancer |

| T(14;20)(q11;p11) | NKX2-2 | 20p11 | T-cell receptor δ | 14q11 | Ectopic NKX2-2 expression driven by TCR enhancer |

| t(11;14)(p15;q11) | LMO1 | 11p15 | T-cell receptor α | 14q11 | Ectopic LMO1 expression, mostly together with LYL1 or TAL1 expression. |

| T-cell receptor δ | 14q11 | ||||

| t(11;14)(p13;q11) | LMO2 | 11p13 | T-cell receptor α | 14q11 | Ectopic LMO2 expression, mostly together with LYL1 or TAL1 expression. |

| T-cell receptor δ | 14q11 | ||||

| del(5)(q14;q14) | MEF2C | 5q14 | - | - | Small deletions close to MEF2C leading to upregulation of MEF2C expression. |

| t(7;19)(q34;p13) | LYL1 | 19p13 | T-cell receptorβ | 7q34 | Ectopic expression of LYL1 driven by TCR enhancer |

| t(11;14)(p11;q32) | SPI1 | 11p11 | BCL11B | 14q32 | Ectopic expression of SPI1 driven by BCL11B |

|

Additional transcription factor aberrations | |||||

| dup(6)(q23;q23) | MYB | 6q23 | - | - | Increased MYB expression due to extra copy of MYB |

| t(6;7)(q23;q34) | T-cell receptor β | 7q34 | Ectopic expression of MYB driven by TCR enhancer | ||

| Various translocations | KMT2A (MLL) | 11q23 | many different partners | KMT2A fusion genes | |

| Mutation/deletion | BCL11B | 14q32 | - | - | Inactivation of BCL11B |

| Mutation/deletion | ETV6 | 12p13 | - | - | Inactivation of ETV6 |

| Mutation/deletion | RUNX1 | 21q22 | - | - | Inactivation of RUNX1 |

| Mutation/deletion | LEF1 | 4q25 | - | - | Inactivation of LEF1 |

| Mutation/deletion | WT1 | 11p13 | - | - | Inactivation of WT1 |

TCR: T-cell receptor gene.

Almost all subgroups of T-ALL are characterized by the clear ectopic expression of one of these transcription factors, except for some immature T-ALL cases where MEF2C expression and other sporadic translocations where SPI1 could be important.1 The oncogenic roles of TAL1 and TLX1 have been nicely illustrated by studies in the mouse, in cell lines and in patient samples. Overexpression of TAL1 or TLX1 in developing thymocytes in the mouse results in the development of T-ALL with long latency.5–8 For TAL1, co-expression of LMO1 and ICN1 dramatically decreased disease latency, in part by increasing the number of leukemia initiating cells.9 Mouse leukemias that eventually developed in the context of TLX1 expression often harbored mutations in Bcl11b or Notch1, as also observed in human T-ALL.7,8 These data confirm that ectopic expression of transcription factors such as TAL1 or TLX1 alone can be an initiating step in T-ALL development, but that additional mutations are required to fully transform normal T-cells to leukemia cells. The ectopic expression of these transcription factors could have a strong effect on the differentiation of the cells, as suggested by the correlation with immunophenotype. Moreover, for TLX1 it was recently shown that TLX1 can bind the T-cell receptor enhancer and in this way can suppress TCRalpha expression and T-cell differentiation.10

There are now four major mechanisms known to cause aberrant expression of transcription factors in T-ALL: (1) chromosomal translocations involving one of the T-cell receptor genes, (2) chromosomal rearrangements with other regulatory sequences, (3) duplication/amplification of the transcription factor, (4) mutations or small insertions generating novel regulatory sequences acting as enhancers (Table 2). The latter mechanism was only recently identified by studies that revealed changes in chromatin structure close to the TAL1 gene, indicative for the presence of a new enhancer region. Detailed analysis of this region led to the identification of mutations that created a de novo binding site for MYB, thereby resulting in recruitment of additional transcriptional regulators and activation of TAL1 expression in cis.11,12 These data illustrate how non-coding mutations can have a strong effect on leukemia development and we can expect that more of these mutations will be identified in the future as more information comes available on the non-coding part of the genome.

Oncogenic NOTCH1 signaling

The NOTCH1 signaling pathway is essential for the commitment of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors to the T-cell lineage and for further development of thymocites.13,14 Activation of NOTCH1 signaling constitutes the most predominant oncogenic event involved in the pathogenesis of T-ALL with activating mutations in more than half of T-ALL cases (Table 1).15 Loss-of-function of negative regulators of NOTCH1 is an alternative mechanism leading to aberrant activation of the pathway. Mutations of FBXW7 are present in 10–15% of T-ALL cases and lead to increased NOTCH1 protein stability.16,17 The role of the NOTCH1 cascade in the context of T-ALL is discussed in more detail in a companion review article.18

Increased kinase signaling

Interleukin 7 (IL7) signaling is essential for normal T-cell development and is triggered by the interaction of IL7 with the heterodimeric IL7 receptor. This interaction induces reciprocal Janus kinases 1 (JAK1) and JAK3 phosphorylation and subsequent recruitment and activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 5 (STAT5). Upon phosphorylation, STAT5 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus where it regulates the transcription of many target genes, including the anti- apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family member proteins.19,20 In addition to the JAK/STAT pathway also the RAS-MAPK and PI3 kinase pathways are activated by IL2, IL7 and SCF that act on the developing T-cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Deregulation of the JAK-STAT signaling cascade in T-ALL.

Representation of the different oncogenic mechanisms that lead to aberrant activation of the IL7 signaling in T-ALL. Interaction of IL7 with the heterodimeric IL7 receptor induces reciprocal JAK1 and JAK3 phosphorylation and subsequent recruitment of STAT5. STAT5 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus where it induces transcription of the pro-survival factor BCL2. IL7 also activates the RAS-MAPK and PI3K kinase pathways. IL7 signaling can indirectly be enhanced by abnormal NOTCH1 signaling, constitutive expression of ZEB2 or by increased presentation of IL7R on the cell surface of thymocytes due to impaired clathrin-dependent endocytosis caused by DNM2 mutations. Proteins that are mutated in T-ALL are indicated with an asterisk. Promising therapeutic agents targeting the oncogenic IL7-JAK-STAT cascade are indicated in red.

Activating mutations in IL7R, JAK1, JAK3 and/or STAT5 are present in 20-30% of T-ALL cases (Table 1),4,21,22 with a higher representation within TLX3-positive, HOXA-positive and ETP-ALL patient subgroups.4,23 A small percentage of cases also show aberrations in phosphatases like PTPN2 and PTPRC, which, amongst other substrates, dephosphorylate and inactivate JAK kinases.24,25 Interestingly, the IL7R signaling cascade can also be hyperactivated in patients that do not carry any genetic aberrations in the IL7R, JAK or STAT5 genes, indicating that still other mechanisms exist to activate this pathway.26,27 Indeed, only recently it was discovered that loss-of-function mutations in DNM2 lead to increased presentation of IL7R on the cell surface of thymocytes due to impaired clathrin-dependent endocytosis.26 In addition, a rare translocation targeting the zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2 locus (ZEB2) has been recently described in T-ALL, and Zeb2 overexpression was shown to increase Il7r expression and Stat5 activation, promoting T-ALL cell survival in a mouse model.27 While most mutations seem to result in activation of JAK1 and JAK3, rare fusion transcripts involving JAK2 have also been described, and wild type TYK2 may have an important role in activating survival pathways of T-ALL cells.28 29

Aberrant activation of the PI3K-AKT pathway results in enhanced cell metabolism, proliferation and impaired apoptosis.30,31 Hyperactivation of the oncogenic PI3K-AKT pathway in T-ALL is mainly caused by inactivating mutations or deletions of the phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN), the main negative regulator of the pathway.22,32–36 In addition, some T-ALL cases show gain-of-function mutations in the regulatory and catalytic subunits of PI3K, respectively p85 and p110; or in the downstream effectors of the cascade such as AKT and mTOR (Table 1).22,35,37 PI3K-AKT signaling activation is also achieved through IL7 stimulation or RAS activation.22,31,38 A recent study on 146 pediatric T-ALL cases described that almost 50% of the patients harbored at least one mutation in the JAK-STAT, PI3K-AKT or RAS-MAPK pathways, underscoring the importance of activation of those cascades for the leukemic cells.22

In addition to the activation of the JAK kinases or the PI3K pathway, activation of the ABL1 kinase is observed in up to 8% of T-ALL cases, with 6% of patients expressing the NUP214-ABL1 fusion protein.39 NUP214-ABL1 is a constitutively active tyrosine kinase that activates STAT5 and the RAS-MAPK pathway, but much weaker as compared to BCR-ABL1.39,40 Interestingly, the kinase activity of NUP214-ABL1 is dependent on its location to the nuclear pore39,41 and its oncogenic properties rely on its interaction with MAD2L1, NUP155 and SMC4 and on the activity of the LCK, a member of the SRC family kinase.42 All data collected to date suggest that the NUP214-ABL1 fusion kinase is a weak oncogene that cooperates with additional oncogenic events to drive leukemia development. In that sense, it is of interest to note that the NUP214-ABL1 fusion is always found together with TLX1 or TLX3 expression and is often associated with loss of PTPN2, a negative regulator of NUP214-ABL1.25,39

RAS-activating mutations were recently described in 44% of diagnosis - relapse sample pairs, indicating an overrepresentation of these defects in high-risk ALL. Interestingly, KRAS mutations rendered lymphoblasts resistant towards methotrexate, while sensitizing them to vincristine.43

Epigenetic factors

T-ALL is one of the pediatric tumor types with the highest incidence of epigenetic lesions, and 56% of samples from children with T-ALL contain mutations in this gene class.44 Also in adult T-ALL, mutations in epigenetic factors are highly common (Table 1).45,46 For a complete overview of all epigenetic lesions identified in T-ALL, we refer to recent reviews on this topic.47,48

The plant homeodomain protein 6 (PHF6) protein was postulated as an epigenetic factor because it contains 2 atypical plant homeodomain (PHD)-like zinc fingers. Canonical PHD domains typically bind post-translationally modified histones. However, the C-terminal PHD-like domain in PHF6 binds double stranded DNA. Besides DNA, PHF6 binds to a growing list of transcriptional regulators such as the Nucleosome Remodeling Deacetylase (NuRD) complex, the RNA Polymerase II Associated Factor 1 (PAF1) transcriptional elongation complex and Upstream Binding Transcription Factor, RNA Polymerase I (UBTF1), a key transcriptional activator of rRNA. The latter brings us to the nucleolar role of PHF6 and its proposed role in ribosome biogenesis. Besides interacting with UBTF1, PHF6 binds the rDNA promotor and rDNA-coding sequences and modulation of PHF6 levels alters rRNA synthesis rates. Todd and colleagues propose that the N-terminal PHD-like domain may mediate binding to rRNA while the C-terminal domain may bind rDNA. As such, PHF6 may act as a scaffold bridging rDNA transcriptional elongation with early processing of produced rRNA. Finally, PHF6 seems involved in the DNA damage response and cell cycle regulation: PHF6 is a substrate of the DNA damage checkpoint kinase ATM and loss of PHF6 results in accumulation of phosphorylated γH2AX, a mark of DNA double-strand breaks, and in G2/M cell cycle arrest.49 Further studies are however required to investigate how inactivation of PHF6 in T-ALL promotes leukemia.

Enzymes involved in regulating methylation of histone 3 lysine 27 (H3K27) are also implicated in T-ALL. Loss-of-function defects in the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) components EZH2, SUZ12 and EED suggest a tumor suppressor role for this complex in T-ALL,4,46,50 which is supported by accelerated leukemia onset in mice upon EZH2 downregulation.46 PRC2 catalyzes H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and its tumor suppressor role may be explained by antagonism with NOTCH1: NOTCH1 activation causes eviction of PRC2 and recruitment of the Lysine Demethylase 6B (KDM6B, also known as JMJD3) at NOTCH1 target gene promoters, resulting in loss of the repressive H3K27me3 chromatin modification and activation of these genes.46,51 Also the Lysine Demethylase 6A (KDM6A, also called UTX) that demethylates H3K27me3 shows inactivating lesions in T-ALL,50–52 and its downregulation accelerates NOTCH1-driven leukemia in mice.51,52 Interestingly, UTX binds TAL1, and it is recruited to TAL1 target genes to remove repressive H3K27me3 marks and activate genes. In TAL1-positive leukemias, UTX behaves as a proto-oncogene and is required for leukemia maintenance, which may explain why UTX inactivation so far has not been detected in TAL1 positive cases.53 The mechanism by which UTX plays a tumor suppressor role in TAL1 negative T-ALL is currently not understood. The KDM6B and KDM6A inhibitor GSKJ4 shows promising preclinical results in T-ALL. Whereas the Brand group reported specificity of this drug for the TAL1 positive T-ALL subgroup, the Aifantis group observed sensitivity in all tested T-ALL cell lines and samples.51,53

RNA metabolism and translation

A few new oncogenes and tumor suppressors recently emerged in T-ALL. Somatic mutations in ribosomal protein genes RPL5, RPL10, and RPL22 have been described in ~20% of T-ALL cases.50,54 Whereas RPL5 and RPL22 show heterozygous inactivating mutations and deletions, RPL10 contains an intriguing mutational hotspot at residue arginine 98 (R98), with 8% of pediatric T-ALL patients harboring an R98S RPL10 missense mutation. Inactivation of Rpl22 accelerates myristoylated Akt-driven T-cell lymphoma in mice.54,55 Mechanistically, heterozygous Rpl22 deletion activates NF-κB and induces stemness factor Lin28B.54 The roles of the RPL5 and RPL10 R98S defects in T-ALL development remain to be determined. Characterization of RPL10 R98S in yeast revealed that it impairs ribosome formation and translation fidelity. Over time, compensatory mutations are acquired, restoring ribosome biogenesis but not translation fidelity, which may drive expression of an oncogenic protein profile.56,57 Translational deregulation in T-ALL may however go far beyond mutations in ribosomal proteins: PHF6 has been linked to ribosome biogenesis, major T-ALL oncogenes and tumor suppressors such as PTEN, NOTCH1 and FBXW7 regulate translation, and T-ALL cells are sensitive to translation inhibitors 4EGI-1 and silvestrol.58–60

Another intriguing novel tumor suppressor that is inactivated in 8% of adult T-ALL samples is CCR4-NOT Transcription Complex Subunit 3 (CNOT3).50 The CCR4-NOT complex catalyzes mRNA deadenylation and may also link again to control of protein translation. In addition, roles for CNOT3 as transcriptional regulator have been proposed.61 Using studies in a fruitfly eye cancer model that is driven by Notch activation, we confirmed that NOT3 (CNOT3 homolog in the fruitfly) is a tumor suppressor gene, but more studies are required to determine how mutations in CNOT3 contribute to leukemia development. It is interesting to note that somatic mutations in CNOT3 have now also been observed in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and in some solid tumors.62

Micro RNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

Inactivation of Dicer1, an essential component of the miRNA processing machinery, impairs NOTCH1 driven T-ALL development in mice and can induce regression of established NOTCH1 driven tumors, indicating a role for one or more miRNAs in (at least NOTCH1 driven) T-ALL.63 Indeed, many miRNAs are misexpressed in T-ALL, either due to a translocation, as key downstream target of T-ALL oncogenes such as NOTCH1 or TAL1, or via unknown mechanisms.64–67 Oncogenic miRNAs (onco-miRs) have been identified downregulating the expression of known T-ALL associated tumor suppressor genes. Examples are miR-19b, miR-20a, miR-26a, miR-92 and miR-223 that cooperatively downregulate IKZF1 (or IKAROS), PTEN, BIM, PHF6, NF1 and FBXW7 transcripts.68 Other miRNAs are underexpressed in T-ALL, leading to overexpression of T-ALL associated oncogenes. An example here is miR-193b, that regulates the expression of MYB and the anti-apoptotic factor MCL1.69 Many additional onco-miRs and tumor suppressive miRNAs have been described in T-ALL. For a partial overview, we refer to reference66.

A related field of interest that recently emerged in T-ALL are lncRNAs, a heterogeneous class of transcripts defined by a minimum length of 200 nucleotides and an apparent lack of protein-coding potential. Diverse molecular mechanisms have been described by which lncNRAs control a wide variety of cellular functions, developmental processes and promote disease pathogenesis, including cancer.70 Interestingly, different T-ALL subgroups are characterized by distinct lncRNA expression profiles.71 In addition, a series of NOTCH1 regulated lncRNAs were identified.72,73 The best characterized one is leukemia-induced noncoding activator RNA 1 (LUNAR1), which is a NOTCH1 regulated pro-oncogenic lncRNA that is required for efficient growth of T-ALL cells by maintaining high expression of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R).73

Cooperation of oncogenic events

Recent sequencing studies have suggested that on average 10 to 20 protein-altering mutations are present in T-ALL cells.4,50,74 This accumulation of mutations does not occur randomly, and specific combinations of mutations are often found, suggesting that those activated oncogenes and inactivated tumor suppressor genes are physiologically interconnected and cooperate during the development and progression of the leukemia.75 Initial founder genomic lesions initiate a pre-malignant process by interacting with the existing machinery of the physiological cell state76 and additional mutations are necessary to drive transformation75,77 and lead to the development of sub-clonal variegation.

This has been very nicely observed in TAL1/LMO2 positive T-ALL cases, where PTEN inactivation occurs most frequently. Interestingly, transplantation of TAL1 rearranged leukemia cells into immune deficient mice allowed development of leukemic subclones with newly acquired PTEN microdeletions.32 These data suggest that there is an enormous pressure for TAL1 expressing T-ALL cells to inactivate PTEN, and that TAL1 expression and PTEN inactivation cooperate during T-cell transformation. In contrast, components of the IL7R-JAK signaling pathway are frequently mutated in immature T-ALL cases or in TLX/HOXA-positive cases, but are underrepresented in TAL1/LMO2-positive cases. In addition, we observed that mutations of IL7R-JAK are positively associated with mutations and deletions of members of the PRC2 complex (EZH2, SUZ12 and EED).21 Similarly, WT1 mutations are most prevalent in TLX3 positive cases.78 These and other genomic data (Figure 2) suggest that initiating lesions leading to ectopic transcription factor expression sensitize the cells to alterations of very specific pathways.

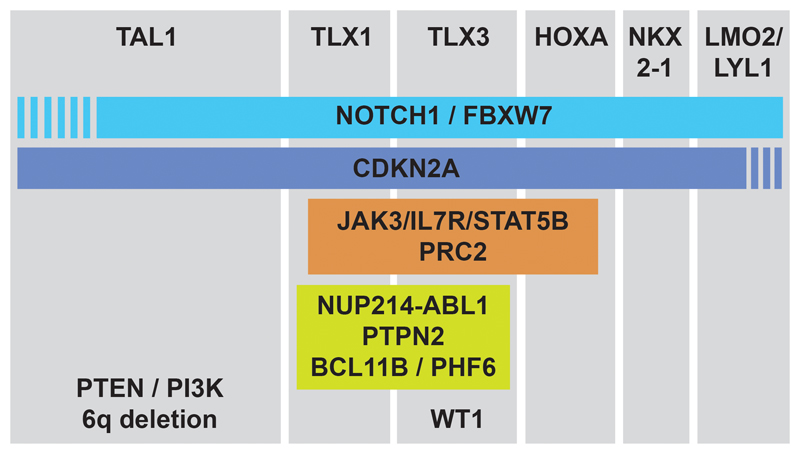

Figure 2. Representation of the cooperation of oncogenic events.

The major subclasses of T-ALL are shown based on the expression of the transcription factors TAL1, TLX1, TLX3, HOXA genes, NKX2-1 or LMO2/LYL1. For each subclass, additional genes are shown that are most frequently mutated in that subclass. The PRC2 complex contains EZH2, SUZ12 and EED.

T-ALL Treatment

Current treatment of T-ALL consists of high intensity combination chemotherapy and results in a very high overall survival for pediatric patients.79 Unfortunately, this treatment comes with significant short term and long term side effects. Especially for young children, the effects of this high dose chemotherapy on bone development, central nervous system and fertility should not be underestimated.80 A complete overview of the treatment options was recently described.81,82

In addition to the side effects, the occurrence of relapse is another important challenge as it is observed in up to 20% of pediatric and 40% of adult T-ALL.83 Relapsed T-ALL cases are often refractory to chemotherapeutics and are associated with a poor prognosis.84,85 From comparative genetic studies conducted on T-ALL samples taken at diagnosis and relapse, and studies with xenotransplantation in mice, it is clear that relapse is determined by the clonal evolution of either a minor genetic subclone present in the primary leukemia, or from the clonal expansion of an ancestral cell (pre-diagnosis).86–89 However, some rare T-ALL late-relapsed cases are considered to be secondary malignancies rather than originated by the initial disease.90

The use of whole-exome sequencing has provided a way to take a detailed view on the genomes of relapsed T-ALL cases and led to the identification of activating mutations in cytosolic 5’-nucleotidase II (NT5C2) as one of the causes of relapse.86,87 NT5C2 is an enzyme responsible for the inactivation of nucleoside-analog chemotherapy drugs.91 When NT5C2 mutant proteins were expressed in T-ALL lymphoblast, an increased nucleotidase activity was observed and the cells became resistant to 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and 6-thioguanine (6-TG), two chemotherapeutic drugs used in maintenance treatment of T-ALL, suggesting the important role of the identified NT5C2 activating mutations in therapy resistance.86

To further improve the treatment of T-ALL and to reduce the toxicity of current treatment, the introduction of newer targeted agents is awaited. Recent drug development in both oncology and immunology has generated a spectrum of new drugs that could be useful for the treatment of specific T-ALL subsets.

With NOTCH1 being the major oncogene in T-ALL and with drugs available that can interfere with the activation (cleavage) of NOTCH1 by the gamma-secretase complex, a number of clinical trials have been initiated with gamma-secretase inhibitors (GSIs). However, these trials led to disappointing clinical results due to the dose-limiting toxicity and low response rates. It remains to be determined how second generation GSIs will perform, but at least some promising anecdotal responses have already been reported and with milder toxicities.92–95 Besides GSIs, other therapeutic approaches for the inhibition of NOTCH1 have been developed. Monoclonal antibodies against the NOTCH1 receptor have anti-tumor effects in vitro and in vivo with limited gastrointestinal toxicities.96,97 Inhibition of ADAM10 may also facilitate effective inhibition of wild-type and mutant NOTCH receptors.98 An antibody against the gamma-secretase complex (A5226A) showed pre-clinical activity against T-ALL.99 Mastermind inhibiting peptides that mimic the NOTCH1 interaction with MAML (SAMH1 peptides) are also being tested.100,101

Since both JAK and ABL1 kinases are often activated in T-ALL, available JAK inhibitors (ruxolitinib and tofacitinib) and ABL1 inhibitors (imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib) could be repurposed for the treatment of T-ALL cases with documented mutations leading to JAK/STAT or ABL1 activation. Several pre-clinical studies have demonstrated activity of ruxolitinib or tofacitinib for the inhibition of T-ALL cells with IL7R or JAK1/JAK3 mutations, while case reports have shown some activity of imatinib or dasatinib for the treatment of NUP214-ABL1 positive T-ALL.4,23,102,103 The therapeutic potential of targeting the IL7Rα signaling and the use of JAK inhibitors in ALL has been recently reviewed.104,105

Similarly, recently approved hedgehog pathway inhibitors could show activity in T-ALL. The hedgehog signaling pathway plays an important role in normal T-cell development, which is steered by the secretion of the sonic hedgehog ligand (SHH) by certain thymic epithelial cells.106 In T-ALL, the hedgehog pathway was reported to be aberrantly activated by rare mutations or ectopic expression of hedgehog pathway genes, and those cases showed response to hedgehog inhibitor treatment.50,107,108 Finally, some other attractive novel therapies have recently been described in T-ALL. Selective Inhibitors of Nuclear Export (SINE) were shown to be highly toxic to T-ALL and AML cells in mouse xenograft models, while having little toxic effects on normal mouse hematopoietic cells.109 In addition, it was demonstrated that TCR-positive T-ALL cells can be targeted by mimicking thymic negative selection as obtained by TCR stimulation via antigen/MHC presentation or via an antibody against CD3.110 The advantage of these types of therapies is that they seem independent of genetic subtypes, avoiding extensive genetic characterization before therapeutic choices are to be made.

Challenges ahead

In the past decades, enormous progress was made in our understanding of the genetics and biology of T-ALL, but there are still significant gaps in our knowledge. To date, almost all attention has gone to defects affecting protein coding genes. The recent identification of mutations in non-coding regions of the genome that result in aberrant transcription factor expression and the discovery of several miRNAs and lncRNAs with a pathogenic role in T-ALL underscore that the ‘non-coding genome’ should not be neglected and that novel classes of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes may remain to be discovered.

Genomic screens have identified recurrent novel oncogenes and tumor suppressors, such as PHF6, RPL10 and CNOT3, for which the exact role in the pathogenesis of T-ALL remains poorly understood. Moreover, genome wide screening has mainly been limited to diagnostic cases and such screens of large patient cohorts are lacking for relapse T-ALL. A better understanding of the biology of relapse is an absolute requirement to improve the dismal prognosis these patients currently are facing.

Analysis of mutational patterns in large patient cohorts revealed that the mutational landscape of T-ALL is not random and that particular defects often co-occur or are mutually exclusive.21 More research is needed to understand the biology behind particular mutational patterns and to characterize the specific clinical behaviors and distinct prognosis associated with these patterns. Related to this issue, also the order in which mutations are acquired in T-ALL development is most likely not random. In addition, the cellular context and exact hematopoietic developmental stage of the cell in which a mutation arises might be very relevant for the oncogenic action of the defect. At this point, not much is known on the order in which mutations are acquired and on the cell of origin in which they need to arise. Extensive modeling in mice and single cell sequencing will be required to answer these questions.

Finally, also the interaction of the leukemia cells with their microenvironment and characterization of the T-ALL niche are essential to fully capture T-ALL pathogenesis. In this context, recently developed advanced microscopy techniques allow in vivo imaging of interactions of leukemia cells with their environment and an essential role in T-ALL maintenance has been discovered for the CXCL12 chemokine and its receptor CXCR4.111–113

The ultimate goal of the T-ALL research community is to translate the knowledge into highly efficient and low toxicity targeted therapies. Whereas the current chemotherapy-based regimens in pediatric T-ALL are associated with high survival rates, the toxicities of these therapies should not be underestimated. With many new targeted agents under development for cancer and auto-immune diseases, it should be possible to effectively repurpose the best agents for the treatment of T-ALL, and to design effective combination therapies directed against the specific sets of cooperating mutations in T-ALL.

Table 3. Promising targeted agents in T-ALL and their stage in clinical testing.

| Compound | Specificity | Clinical Phase | Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOTCH1 Signaling | |||

| MK-0752 | γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) | Phase 1 | T-ALL and Lymphoma |

| PF 03084014 | γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) | Phase 1 | Advanced-stage cancers, T ALL, Lymphoblastic Lymphoma |

| BMS 906024 (with dexamethasone) | γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) | Phase 1 | T-ALL or T cell lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| OMP 52M51 | Notch1 inhibitory antibody | Phase 1 | Dose-escalation study in lymphoid malignancy |

| LY3039478 | Notch1 Inhibitor | Phase 1 | Dose-escalation study in advanced-stage cancers |

| BMS-536924 | ATP-competitive IGF-1R/IR inhibitor | Pre-clinical | |

| JAK-STAT inhibitors | |||

| Ruxolitinib | JAK1/2 inhibitor | Phase 1 | Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) |

| Phase 2 | B-ALL | ||

| FDA Approved | Myelofibrosis | ||

| Phase 1/2 | Fallopian Tube cancer, Ovarian Cancer, Primary Peritoneal Cancer | ||

| Tofacitinib | JAK3 inhibitor | FDA Approved | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Phase 1 | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | ||

| Phase 3 | Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis | ||

| Pimozide | STAT5 inhibitor | FDA Approved | Schizophrenia, Psychotic Disorders |

| Phase 2 | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | ||

| 17-AAG | HSP90 inhibitor | Phase 3 | Multiple Myeloma (MM) |

| Phase 2 | Pancreatic Cancer | ||

| Phase 2 | Advanced Malignancies | ||

| Phase 2 | Ovarian Cancer | ||

| PU-H71 | HSP90 inhibitor | Phase 1 | Solid Tumor, Lymphoma |

| Phase 1 | Metastatic Solid Tumor, Lymphoma, Myeloproliferative Neoplasms | ||

| Inducers of apoptosis | |||

| ABT-263 (Navitoclax) | inhibitor of Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 and Bcl-w | Phase 1 | Non-Small Cell Lung |

| Phase 2 | Platinum-resistant or Refractory Ovarian Cancer | ||

| Phase 1 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | ||

| Phase 1/2 | Melanoma | ||

| ABT-199 (Venetoclax) | Bcl-2-selective inhibitor | FDA Approved | Chronic Lymphoblastic Leukemia (CLL) |

| Phase 3 | Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma | ||

| PI3K inhibitors | |||

| CAL-130 | inhibits p110γ and p110δ catalytic domains | Pre-clinical | |

| Ly294002 | inhibit PI3Kα/δ/β | Phase 1 | Neuroblastoma |

| Pictilisib (GDC-0941) | inhibitor of PI3Kα/δ | Phase 2 | Breast Cancer |

| Phase 2 | Non-Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | ||

| Apitolisib (GDC-0980, RG7422) | inhibitor for PI3Kα/β/δ/γ | Phase 2 | Endometrial Carcinoma |

| Phase 1/2 | Prostate Cancer | ||

| Phase 2 | Renal Cell Carcinoma | ||

| MEK inhibitors | |||

| CI-1040 | ATP non-competitive MEK1/2 inhibitor | Phase 2 | Breast Cancer, Colorectal Cancer, Lung Cancer, Pancreatic Cancer |

| Selumetinib (AZD6244) | MEK1 inhibitor | Phase 2 | Triple Negative Breast Cancer |

| Phase 1 | Lung Cancer, Melanoma, Head and Neck Carcinoma, Gastroesophageal Cancer, Breast Cancer, Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Colorectal Cancer | ||

| Trametinib (GSK1120212) | MEK1/2 inhibitor | Phase 2 | Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors |

| Phase 1 | Melanoma | ||

| Phase 1 | Neuroblastoma | ||

| Phase 2 | Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer | ||

| ABL inhibitors | |||

| Imatinib | v-Abl, c-Kit and PDGFR inhibitor | FDA Approved | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) |

| Phase 2 | B-ALL, B Lymphoblastic Lymphoma, T-ALL, T Lymphoblastic Lymphoma | ||

| Phase 3 | Philadelphia Chromosome Positive Adult ALL | ||

| Dasatinib | Abl, Src and c-Kit inhibitor | FDA Approved | CML |

| Phase 2 | ALL | ||

| Phase 1 | Chronic Kidney Disease | ||

| Nilotinib | Abl, Src and c-Kit inhibitor | Phase 2 | Glioma |

| Phase 3 | Philadelphia Chromosome Positive Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia | ||

| FDA Approved | CML | ||

| Hedgehog inhibitors | |||

| Vismodegib (GDC-0449) | SMO inhibitor | FDA approved | Basal cell carcinoma |

| Phase 2 | Breast Cancer | ||

| Phase 2 | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin, MM, Advanced Solid Tumors | ||

| GANT61 | GLI1 inhibitor | Pre-clinical | |

| Translation inhibitors | |||

| Rapamycin | specific mTOR inhibitor | Phase 2 | Myelodysplastic Syndrome, CLL, ALL, T Lymphoblastic Lymphoma, Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, Acute Biphenotypic Leukemia, Acute Undifferentiated Leukemia |

| Phase 1 | Fallopian Tube Carcinoma, Ovarian Carcinoma, Primary Peritoneal Carcinoma | ||

| 4EGI-1 | competitive eIF4E/eIF4G interaction inhibitor | Pre-clinical | |

Ackowledegments

We would like to thank all researchers and clinicians for their contributions to the field and apologize to those whose work we could not describe or cite. The laboratory of KDK is funded by an ERC starting grant (334946), FWO-Vlaanderen funding (G067015N and G084013N) and a Stichting Tegen Kanker grant (2012-176). The laboratory of JC is funded by an ERC consolidator grant (617340), and funding from FWO-Vlaanderen (G.0683.12), Stichting Tegen Kanker (2014-120) and Kom Op Tegen Kanker. TG is funded by the fellowship “Emmanuel van der schueren” Kom op tegen kanker.

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions

TG, CV, JC and KDK contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- 1.Homminga I, Pieters R, Langerak AW, et al. Integrated transcript and genome analyses reveal NKX2-1 and MEF2C as potential oncogenes in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(4):484–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrando AA, Neuberg DS, Staunton J, et al. Gene expression signatures define novel oncogenic pathways in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(1):75–87. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soulier J, Clappier E, Cayuela J-M, et al. HOXA genes are included in genetic and biologic networks defining human acute T-cell leukemia (T-ALL) Blood. 2005;106(1):274–286. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012;481(7380):157–163. doi: 10.1038/nature10725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condorelli GL, Facchiano F, Valtieri M, et al. T-cell-directed TAL-1 expression induces T-cell malignancies in transgenic mice. Cancer research. 1996;56(22):5113–5119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelliher MA, Seldin DC, Leder P. Tal-1 induces T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia accelerated by casein kinase IIalpha. EMBO J. 1996;15(19):5160–5166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rakowski LA, Lehotzky EA, Chiang MY. Transient responses to NOTCH and TLX1/HOX11 inhibition in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. PloS one. 2011;6(2):e16761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Keersmaecker K, Real PJ, Gatta GD, et al. The TLX1 oncogene drives aneuploidy in T cell transformation. Nature Medicine. 2010;16(11):1321–1327. doi: 10.1038/nm.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerby B, Tremblay CS, Tremblay M, et al. SCL, LMO1 and Notch1 reprogram thymocytes into self-renewing cells. PLoS genetics. 2014;10(12):e1004768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dadi S, Le Noir S, Payet-Bornet D, et al. TLX Homeodomain Oncogenes Mediate T Cell Maturation Arrest in T-ALL via Interaction with ETS1 and Suppression of TCRα Gene Expression. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(4):563–576. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navarro J-M, Touzart A, Pradel LC, et al. Site- and allele-specific polycomb dysregulation in T-cell leukaemia. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6094. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansour MR, Abraham BJ, Anders L, et al. Oncogene regulation. An oncogenic super-enhancer formed through somatic mutation of a noncoding intergenic element. Science. 2014;346(6215):1373–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1259037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radtke F, Wilson A, Stark G, et al. Deficient T cell fate specification in mice with an induced inactivation of Notch1. Immunity. 1999;10(5):547–558. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radtke F, Tacchini-Cottier F. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by Notch. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(6):427. doi: 10.1038/nri3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306(5694):269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Neil J, Grim J, Strack P, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson BJ, Buonamici S, Sulis ML, et al. The SCFFBW7 ubiquitin ligase complex as a tumor suppressor in T cell leukemia. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1825–1835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez-Martin M, Ferrando A. The Notch-Myc highway in T-cell ALL. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-692582. [in press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takada K, Jameson SC. Naive T cell homeostasis: from awareness of space to a sense of place. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(12):823–832. doi: 10.1038/nri2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzucchelli R, Durum SK. Interleukin-7 receptor expression: intelligent design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(2):144–154. doi: 10.1038/nri2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vicente C, Schwab C, Broux M, et al. Targeted sequencing identifies associations between IL7R-JAK mutations and epigenetic modulators in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2015;100(10):1301–1310. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.130179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canté-Barrett K, Spijkers-Hagelstein JAP, Buijs-Gladdines JGCAM, et al. MEK and PI3K-AKT inhibitors synergistically block activated IL7 receptor signaling in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(9):1832–1843. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zenatti PP, Ribeiro D, Li W, et al. Oncogenic IL7R gain-of-function mutations in childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):932–939. doi: 10.1038/ng.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porcu M, Kleppe M, Gianfelici V, et al. Mutation of the receptor tyrosine phosphatase PTPRC (CD45) in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(19):4476–4479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleppe M, Lahortiga I, Chaar El T, et al. Deletion of the protein tyrosine phosphatase gene PTPN2 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2010;42(6):530–535. doi: 10.1038/ng.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tremblay CS, Brown FC, Collett M, et al. Loss-of-function mutations of Dynamin 2 promote T-ALL by enhancing IL-7 signalling. Leukemia. 2016;30(10):1993–2001. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goossens S, Radaelli E, Blanchet O, et al. ZEB2 drives immature T-cell lymphoblastic leukaemia development via enhanced tumour-initiating potential and IL-7 receptor signalling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:5794. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lacronique V, Boureux A, Valle VD, et al. A TEL-JAK2 fusion protein with constitutive kinase activity in human leukemia. Science. 1997;278(5341):1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanda T, Tyner JW, Gutierrez A, et al. TYK2-STAT1-BCL2 pathway dependence in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2013;3(5):564–577. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Class I PI3K in oncogenic cellular transformation. Oncogene. 2008;27(41):5486–5496. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cully M, You H, Levine AJ, Mak TW. Beyond PTEN mutations: the PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6(3):184–192. doi: 10.1038/nrc1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendes RD, Sarmento LM, Canté-Barrett K, et al. PTEN microdeletions in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia are caused by illegitimate RAG-mediated recombination events. Blood. 2014;124(4):567–578. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-562751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palomero T, Sulis ML, Cortina M, et al. Mutational loss of PTEN induces resistance to NOTCH1 inhibition in T-cell leukemia. Nat Med. 2007;13(10):1203–1210. doi: 10.1038/nm1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuurbier L, Petricoin EF, Vuerhard MJ, et al. The significance of PTEN and AKT aberrations in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2012;97(9):1405–1413. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.059030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gutierrez A, Sanda T, Grebliunaite R, et al. High frequency of PTEN, PI3K, and AKT abnormalities in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(3):647–650. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva A, Yunes JA, Cardoso BA, et al. PTEN posttranslational inactivation and hyperactivation of the PI3K/Akt pathway sustain primary T cell leukemia viability. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(11):3762–3774. doi: 10.1172/JCI34616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann M, Vosberg S, Schlee C, et al. Mutational spectrum of adult T-ALL. Oncotarget. 2015;6(5):2754–2766. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barata JT, Silva A, Brandao JG, et al. Activation of PI3K is indispensable for interleukin 7-mediated viability, proliferation, glucose use, and growth of T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. J Exp Med. 2004;200(5):659–669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graux C, Cools J, Melotte C, et al. Fusion of NUP214 to ABL1 on amplified episomes in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2004;36(10):1084–1089. doi: 10.1038/ng1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Keersmaecker K, Versele M, Cools J, Superti-Furga G, Hantschel O. Intrinsic differences between the catalytic properties of the oncogenic NUP214-ABL1 and BCR-ABL1 fusion protein kinases. Leukemia. 2008;22(12):2208–2216. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Keersmaecker K, Rocnik JL, Bernad R, et al. Kinase activation and transformation by NUP214-ABL1 is dependent on the context of the nuclear pore. Molecular cell. 2008;31(1):134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Keersmaecker K, Porcu M, Cox L, et al. NUP214-ABL1-mediated cell proliferation in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia is dependent on the LCK kinase and various interacting proteins. Haematologica. 2013;99(1):85–93. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.088674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oshima K, Khiabanian H, da Silva-Almeida AC, et al. Mutational landscape, clonal evolution patterns, and role of RAS mutations in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(40):11306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608420113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huether R, Dong L, Chen X, et al. The landscape of somatic mutations in epigenetic regulators across 1,000 paediatric cancer genomes. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3630. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Vlierberghe P, Palomero T, Khiabanian H, et al. PHF6 mutations in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2010;42(4):338–342. doi: 10.1038/ng.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ntziachristos P, Tsirigos A, Van Vlierberghe P, et al. Genetic inactivation of the polycomb repressive complex 2 in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Med. 2012;18(2):298–301. doi: 10.1038/nm.2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van der Meulen J, Van Roy N, Van Vlierberghe P, Speleman F. The epigenetic landscape of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;53:547–557. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peirs S, Van der Meulen J, Van de Walle I, et al. Epigenetics in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Immunol Rev. 2015;263(1):50–67. doi: 10.1111/imr.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Todd MAM, Ivanochko D, Picketts DJ. PHF6 Degrees of Separation: The Multifaceted Roles of a Chromatin Adaptor Protein. Genes. 2015;6(2):325–352. doi: 10.3390/genes6020325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Keersmaecker K, Atak ZK, Li N, et al. Exome sequencing identifies mutation in CNOT3 and ribosomal genes RPL5 and RPL10 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(2):186–190. doi: 10.1038/ng.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ntziachristos P, Tsirigos A, Welstead GG, et al. Contrasting roles of histone 3 lysine 27 demethylases in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2014;514(7523):513–517. doi: 10.1038/nature13605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van der Meulen J, Sanghvi V, Mavrakis K, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase UTX is a gender-specific tumor suppressor in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;125(1):13–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-577270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benyoucef A, Palii CG, Wang C, et al. UTX inhibition as selective epigenetic therapy against TAL1-driven T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Dev. 2016;30(5):508–521. doi: 10.1101/gad.276790.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rao S, Lee S-Y, Gutierrez A, et al. Inactivation of ribosomal protein L22 promotes transformation by induction of the stemness factor, Lin28B. Blood. 2012;120(18):3764–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-415349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rao S, Cai KQ, Stadanlick JE, et al. Ribosomal Protein Rpl22 Controls the Dissemination of T-cell Lymphoma. Cancer research. 2016;76(11):3387–3396. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sulima SO, Patchett S, Advani VM, et al. Bypass of the pre-60S ribosomal quality control as a pathway to oncogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(15):5640–5645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400247111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Keersmaecker K, Sulima SO, Dinman JD. Ribosomopathies and the paradox of cellular hypo- to hyperproliferation. Blood. 2015;125(9):1377–1382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-569616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwarzer A, Holtmann H, Brugman M, et al. Hyperactivation of mTORC1 and mTORC2 by multiple oncogenic events causes addiction to eIF4E-dependent mRNA translation in T-cell leukemia. Oncogene. 2014;34(27):3593–3604. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolfe AL, Singh K, Zhong Y, et al. RNA G-quadruplexes cause eIF4A-dependent oncogene translation in cancer. Nature. 2014;513(7516):65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature13485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Girardi T, De Keersmaecker K. T-ALL: ALL a matter of Translation? Haematologica. 2015;100(3):293–295. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.118562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shirai Y-T, Suzuki T, Morita M, Takahashi A, Yamamoto T. Multifunctional roles of the mammalian CCR4-NOT complex in physiological phenomena. Front Genet. 2014;5:286. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Puente XS, Beà S, Valdés-Mas R, et al. Non-coding recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2015;526(7574):519–524. doi: 10.1038/nature14666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Junker F, Chabloz A, Koch U, Radtke F. Dicer1 imparts essential survival cues in Notch-driven T-ALL via miR-21-mediated tumor suppressor Pdcd4 repression. Blood. 2015;126(8):993–1004. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-618892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li X, Sanda T, Look AT, Novina CD, Boehmer von H. Repression of tumor suppressor miR-451 is essential for NOTCH1-induced oncogenesis in T-ALL. J Exp Med. 2011;208(4):663–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.20102384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mavrakis KJ, Wolfe AL, Oricchio E, et al. Genome-wide RNA-mediated interference screen identifies miR-19 targets in Notch-induced T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(4):372–379. doi: 10.1038/ncb2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aster JC. Dicing up T-ALL. Blood. 2015;126(8):929–930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-06-646653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mansour MR, Sanda T, Lawton LN, et al. The TAL1 complex targets the FBXW7 tumor suppressor by activating miR-223 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Exp Med. 2013;210(8):1545–1557. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mavrakis KJ, Van der Meulen J, Wolfe AL, et al. A cooperative microRNA-tumor suppressor gene network in acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) Nat Genet. 2011;43(7):673–678. doi: 10.1038/ng.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mets E, Van der Meulen J, Van Peer G, et al. MicroRNA-193b-3p acts as a tumor suppressor by targeting the MYB oncogene in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;29(4):798–806. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schmitz SU, Grote P, Herrmann BG. Mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function in development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(13):2491–2509. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2174-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wallaert A, Durinck K, Van Loocke W, et al. Long noncoding RNA signatures define oncogenic subtypes in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(9):1927–1930. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Durinck K, Wallaert A, Van de Walle I, et al. The Notch driven long non-coding RNA repertoire in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2014;99(12):1808–1816. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.115683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trimarchi T, Bilal E, Ntziachristos P, et al. Genome-wide mapping and characterization of Notch-regulated long noncoding RNAs in acute leukemia. Cell. 2014;158(3):593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holmfeldt L, Wei L, Diaz-Flores E, et al. The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(3):242–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Speck NA, Gilliland DG. Core-binding factors in haematopoiesis and leukaemia. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(7):502–513. doi: 10.1038/nrc840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Knudson AG. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68(4):820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tosello V, Mansour MR, Barnes K, et al. WT1 mutations in T-ALL. Blood. 2009;114(5):1038–1045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1663–1669. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hoed den MAH, Pluijm SMF, Winkel te ML, et al. Aggravated bone density decline following symptomatic osteonecrosis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2015;100(12):1564–1570. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.125583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Litzow MR. How we treat T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Blood. 2015;126(7):833–841. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-551895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pui C-H, Mullighan CG, Evans WE, Relling MV. Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: where are we going and how do we get there? Blood. 2012;120(6):1165–1174. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-378943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pui C-H, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371(9617):1030–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nguyen K, Devidas M, Cheng S-C, et al. Factors influencing survival after relapse from acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children's Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 2008;22(12):2142–2150. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bhojwani D, Pui C-H. Relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(6):e205–17. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70580-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tzoneva G, Perez-Garcia A, Carpenter Z, et al. Activating mutations in the NT5C2 nucleotidase gene drive chemotherapy resistance in relapsed ALL. Nat Med. 2013;19(3):368–371. doi: 10.1038/nm.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kunz JB, Rausch T, Bandapalli OR, et al. Pediatric T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia evolves into relapse by clonal selection, acquisition of mutations and promoter hypomethylation. Haematologica. 2015;100(11):1442. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.129692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mullighan CG, Phillips LA, Su X, et al. Genomic analysis of the clonal origins of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2008;322(5906):1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.1164266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Clappier E, Gerby B, Sigaux F, et al. Clonal selection in xenografted human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia recapitulates gain of malignancy at relapse. J Exp Med. 2011;208(4):653–661. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Szczepanski T, van der Velden VHJ, Waanders E, et al. Late recurrence of childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia frequently represents a second leukemia rather than a relapse: first evidence for genetic predisposition. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1643–1649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brouwer C, Vogels-Mentink TM, Keizer-Garritsen JJ, et al. Role of 5'-nucleotidase in thiopurine metabolism: enzyme kinetic profile and association with thio-GMP levels in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia during 6-mercaptopurine treatment. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;361(1-2):95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Papayannidis C, DeAngelo DJ, Stock W, et al. A Phase 1 study of the novel gamma-secretase inhibitor PF-03084014 in patients with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(9):e350. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zweidler-McKay P, DeAngelo DJ, Douer D, et al. The Safety and Activity of BMS-906024, a Gamma Secretase Inhibitor (GSI) with Anti-Notch Activity, in Patients with Relapsed T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-ALL): Initial Results of a Phase 1 Trial. Blood. 2014;124(21):968. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Messersmith WA, Shapiro GI, Cleary JM, et al. A Phase I dose-finding study in patients with advanced solid malignancies of the oral γ-secretase inhibitor PF-03084014. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;21(1):60–67. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Knoechel B, Bhatt A, Pan L, et al. Complete hematologic response of early T-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia to the γ-secretase inhibitor BMS-906024: genetic and epigenetic findings in an outlier case. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2016;1(1):a000539. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Aste-Amézaga M, Zhang N, Lineberger JE, et al. Characterization of Notch1 antibodies that inhibit signaling of both normal and mutated Notch1 receptors. PloS one. 2010;5(2):e9094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu Y, Cain-Hom C, Choy L, et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of individual Notch receptors. Nature. 2010;464(7291):1052–1057. doi: 10.1038/nature08878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sulis ML, Saftig P, Ferrando AA. Redundancy and specificity of the metalloprotease system mediating oncogenic NOTCH1 activation in T-ALL. Leukemia. 2011;25(10):1564–1569. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hayashi I, Takatori S, Urano Y, et al. Neutralization of the γ-secretase activity by monoclonal antibody against extracellular domain of nicastrin. Oncogene. 2011;31(6):787–798. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, et al. Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex. Nature. 2009;462(7270):182–188. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu R, Li X, Tulpule A, et al. KSHV-induced notch components render endothelial and mural cell characteristics and cell survival. Blood. 2009;115(4):887–895. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Degryse S, de Bock CE, Cox L, Demeyer S, Gielen O. JAK3 mutants transform hematopoietic cells through JAK1 activation, causing T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a mouse model. Blood. 2014;124(20):3092–3100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-566687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maude SL, Dolai S, Delgado-Martin C, et al. Efficacy of JAK/STAT pathway inhibition in murine xenograft models of early T-cell precursor (ETP) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(11):1759–1767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-580480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cramer SD, Aplan PD, Durum SK. Therapeutic targeting of IL-7R signaling pathways in ALL treatment. Blood. 2016;128(4):473. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-679209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Degryse S, Cools J. JAK kinase inhibitors for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:91. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0192-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Crompton T, Outram SV, Hager-Theodorides AL. Sonic hedgehog signalling in T-cell development and activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(9):726–735. doi: 10.1038/nri2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dagklis A, Pauwels D, Lahortiga I, et al. Hedgehog pathway mutations in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2014;100(3):e102–5. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.119248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dagklis A, Demeyer S, De Bie J, et al. Hedgehog pathway activation in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia predicts response to SMO and GLI1 inhibitors. Blood. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-703454. [e-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Etchin J, Sanda T, Mansour MR, et al. KPT-330 inhibitor of CRM1 (XPO1)-mediated nuclear export has selective anti-leukaemic activity in preclinical models of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(1):117–127. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Trinquand A, Santos Dos NR, Quang CT, et al. Triggering the TCR Developmental Checkpoint Activates a Therapeutically Targetable Tumor Suppressive Pathway in T-cell Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(9):972–985. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hawkins ED, Duarte D, Akinduro O, et al. T-cell acute leukaemia exhibits dynamic interactions with bone marrow microenvironments. Nature. 2016;538(7626):518. doi: 10.1038/nature19801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Passaro D, Irigoyen M, Catherinet C, et al. CXCR4 Is Required for Leukemia-Initiating Cell Activity in T Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(6):769–779. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pitt LA, Tikhonova AN, Hu H, et al. CXCL12-Producing Vascular Endothelial Niches Control Acute T Cell Leukemia Maintenance. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(6):755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]