To the Editor:

Asthma is a complex disease that is heritable (1); however, common genetic variants explain a small portion of asthma risk (2). Epigenetic changes are influenced by the environment (3) and affect the expression of transcription factors that alter the maturation of T lymphocytes (4) and could potentially explain some of the missing heritability in asthma. We have previously reported that allergic asthma–associated DNA methylation changes in nasal epithelia are more substantial in magnitude and have a stronger association with gene expression (5) than we reported for peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (6). Others have reported an IL-13–induced DNA signature in asthmatic airway epithelia (7). However, no study to date has compared asthma-associated DNA methylation marks across different tissues within an individual.

The goal of this investigation was to establish proof of concept that nasal epithelium can be used as a proxy for the airway epithelium in studies of allergic asthma. We collected PBMCs, nasal epithelia, and bronchial epithelia from 12 subjects with allergic asthma and 12 control subjects without asthma, all non-Hispanic white nonsmoker adults. There are no significant differences in age (median [low, high]: 37 yr [24, 74 yr] in patients with asthma vs. 29 yr [24, 45 yr] in control subjects; P = 0.16 by Mann-Whitney U test) and sex (33% men in patients with asthma vs. 50% men in control subjects; P = 0.59 by chi-square test) between cases and control subjects; however, serum IgE concentrations are significantly higher in patients with asthma (median [low, high]: cases = 115 [7, 1,085] vs. control subjects = 25.5 [7, 71], P = 0.003 by Mann-Whitney U test). By study design, all patients with asthma were on inhaled corticosteroids for at least 4 weeks before sample collection and not on any nasal steroids.

Following standard approaches to quality control (5, 6), we identified single CpG sites (from Illumina 450k array; Illumina, San Diego, CA) or differentially methylated positions (DMPs) associated with allergic asthma after controlling for age, sex, batch effects (array position as identified by principal components analysis), and multiple comparisons (false discovery rate) and after filtering out probe sets with known single-nucleotide polymorphisms at the CpG site in the CEU (Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe) population.

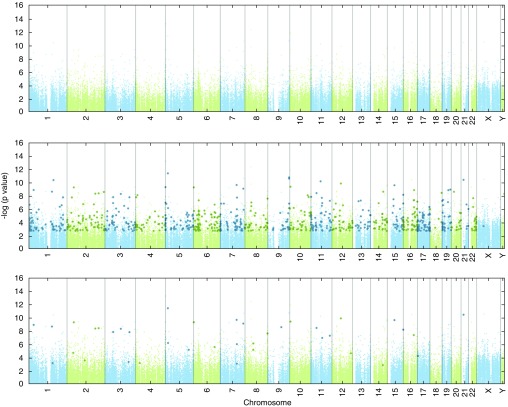

To maximize the power for DMP analysis, we first used a mixed-effects linear model for all samples adjusting for tissue and identified 9,598 significant DMPs with false discovery rate–adjusted q value of 0.005. We then ran individual tissue models to identify tissue-specific changes in DNA methylation and determined that, of the 9,598 DMPs, none were significant in PBMCs, 7,484 were significant in nasal epithelia, and 63 were significant in airway epithelia (tissue-specific model q < 0.05). Focusing on the largest effect size (>10% methylation change) resulted in 816 DMPs in nasal epithelia and 41 DMPs in bronchial epithelia (Figure 1). Forty-one DMPs in airway epithelia are associated with 34 unique genes, of which 25 have significant DMPs with greater than 10% change in nasal cells and an additional 7 have significant DMPs with less than 10% change in nasal epithelial cells.

Figure 1.

Differentially methylated single-CpG probes or differentially methylated positions in bronchial and nasal epithelia, but not peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), are associated with asthma after controlling for age, sex, technical variables, and batch effects in white adult nonsmoker subjects. Manhattan plot of the false discovery rate–adjusted P values (q values) for disease status (asthma/control) from the tissue-specific linear model. PBMC, top panel; nasal epithelia, middle panel; and bronchial epithelia, bottom panel. Probes with q < 0.05 in the tissue-specific linear model are highlighted by darker larger symbols.

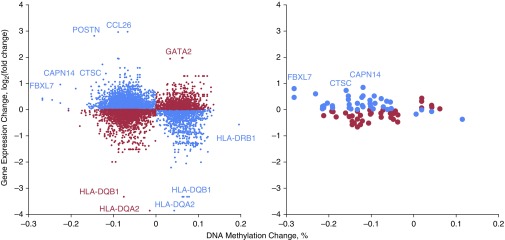

To determine the effect of allergic asthma–associated methylation changes on gene expression, we examined array-based (Agilent 8 × 60k; Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) measures of expression of genes nearest DMPs as a function of methylation change. As in our previous work (5, 6), we identified an enrichment of inverse correlations of DNA methylation and expression in nasal epithelia (P = 2.2 × 10−16 for DMPs; Figure 2). This enrichment was not observed in airway epithelia, presumably owing to the small number of data points (Figure 2). Some of the genes with the most prominent changes in DNA methylation and gene expression are consistent in nasal and airway epithelia (CAPN14, CTSC, and FBXL7, among others), whereas we identified other genes with larger changes in nasal epithelia (POSTN, CCL26, GATA2, HLA genes, to name a few). The majority of the genes with the most pronounced methylation–expression relationships were also identified in our previous nasal epithelial study (5), despite differences in age, ethnicity, and potential exposures between the two cohorts.

Figure 2.

DNA methylation changes are associated with changes in gene expression in nasal and bronchial epithelia. Expression changes of genes nearest differentially methylated positions from Figure 1. x-Axis: methylation difference is represented by the mean percentage methylation difference in subjects with asthma compared with control subjects; y-axis: expression difference is represented by the mean fold change in subjects with asthma compared with control subjects (on the log2 scale). Nasal epithelia, left panel; bronchial epithelia, right panel. The blue symbols represent hypomethylated genes that were associated with increased gene expression as well as some hypermethylated genes associated with decreased gene expression. The red symbols represent methylation changes that were not associated with expected gene expression differences.

Our study is the first to directly compare DNA methylation and gene expression changes in PBMCs, nasal epithelia, and airway epithelia, and highlights three important points. First, nasal epithelia appear to be a good proxy for airway epithelia in studies of allergic asthma, as almost all allergic asthma–associated methylation changes are captured by nasal epithelia, and many of them have relationships with gene expression in both tissues. This finding is supported by published work demonstrating high concordance of nasal and airway transcriptomes in asthma (8). Second, we identified many more asthma-associated DNA methylation changes in nasal epithelia than airway epithelia, likely because nasal epithelium is the primary interface with the environment, interacting with allergens and other environmental stimuli. Although it may appear surprising that the asthma airway epithelium biomarker gene POSTN (9) was only identified in the nasal epithelia in our analysis, its methylation change was similar in the two tissues (14.5% hypomethylated in nasal and 13.6% hypomethylated in airway epithelia) but more significant in nasal epithelia, in which it reached genome-wide significant threshold (q = 0.01), whereas this was not the case in airway epithelia (q = 0.12). POSTN is sevenfold up-regulated in nasal and fourfold in airway epithelia. Third, although studies of peripheral blood can shed light on epigenetic and transcriptional changes in immune cells in asthma (6, 10), large sample sizes are needed because of a weaker signal and mixture of cell types that are not specific to the airway. One limitation of our study is absence of an allergic group without asthma to delineate signal from asthma versus allergies. However, most individuals with asthma are also allergic, and therefore our conclusions apply to the majority of those with asthma regardless of whether methylation changes in the nasal epithelia are driven by allergy or asthma. Additional cohorts will also be able to provide independent validation for the results of our pilot study.

We conclude that genomic profiling of nasal epithelia captures most disease-relevant changes identified in airway epithelia but also provides additional targets that are most likely influenced by exposures. Thus, epigenetic marks in nasal epithelia may prove useful as a biomarker of disease severity and response to treatment or as a biosensor of the environment in asthma. Future studies will be needed to test association with specific exposures to determine the origin of the strong signal observed in nasal epithelia.

Footnotes

Supported by NHLBI grant R01-HL101251 and the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences grant P01-ES18181.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Thomsen SF, van der Sluis S, Kyvik KO, Skytthe A, Backer V. Estimates of asthma heritability in a large twin sample. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:1054–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lockett GA, Holloway JW. Genome-wide association studies in asthma; perhaps, the end of the beginning. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:463–469. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328364ea5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santangelo S, Cousins DJ, Winkelmann NE, Staynov DZ. DNA methylation changes at human Th2 cytokine genes coincide with DNase I hypersensitive site formation during CD4(+) T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2002;169:1893–1903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang IV, Pedersen BS, Liu AH, O’Connor GT, Pillai D, Kattan M, Misiak RT, Gruchalla R, Szefler SJ, Khurana Hershey GK, et al. The nasal methylome and childhood atopic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.036. [online ahead of print] 13 Oct 2016; DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang IV, Pedersen BS, Liu A, O’Connor GT, Teach SJ, Kattan M, Misiak RT, Gruchalla R, Steinbach SF, Szefler SJ, et al. DNA methylation and childhood asthma in the inner city. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicodemus-Johnson J, Naughton KA, Sudi J, Hogarth K, Naurekas ET, Nicolae DL, Sperling AI, Solway J, White SR, Ober C. Genome-wide methylation study identifies an IL-13-induced epigenetic signature in asthmatic airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:376–385. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1243OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poole A, Urbanek C, Eng C, Schageman J, Jacobson S, O’Connor BP, Galanter JM, Gignoux CR, Roth LA, Kumar R, et al. Dissecting childhood asthma with nasal transcriptomics distinguishes subphenotypes of disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:670–678.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, Koth LL, Arron JR, Fahy JV. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang L, Willis-Owen SA, Laprise C, Wong KC, Davies GA, Hudson TJ, Binia A, Hopkin JM, Yang IV, Grundberg E, et al. An epigenome-wide association study of total serum immunoglobulin E concentration. Nature. 2015;520:670–674. doi: 10.1038/nature14125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]